Inclusive Socio-Spatial Transformation: A Study on the Incremental Renovation Mode and Strategy of Residential Space in Beijing’s Urban Villages

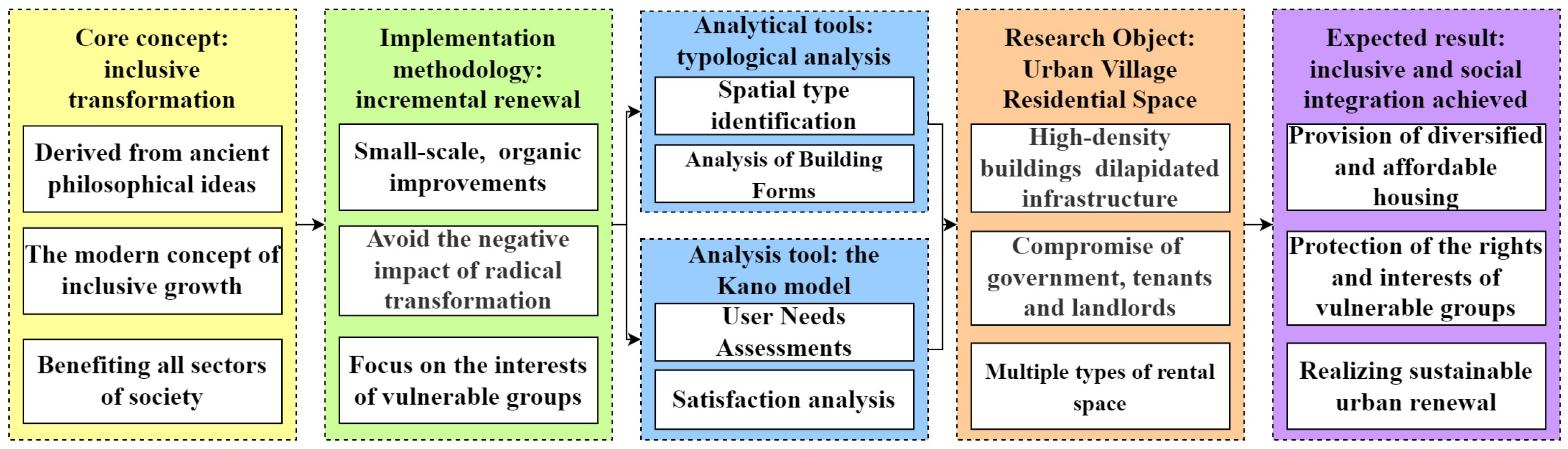

Abstract

1. Introduction

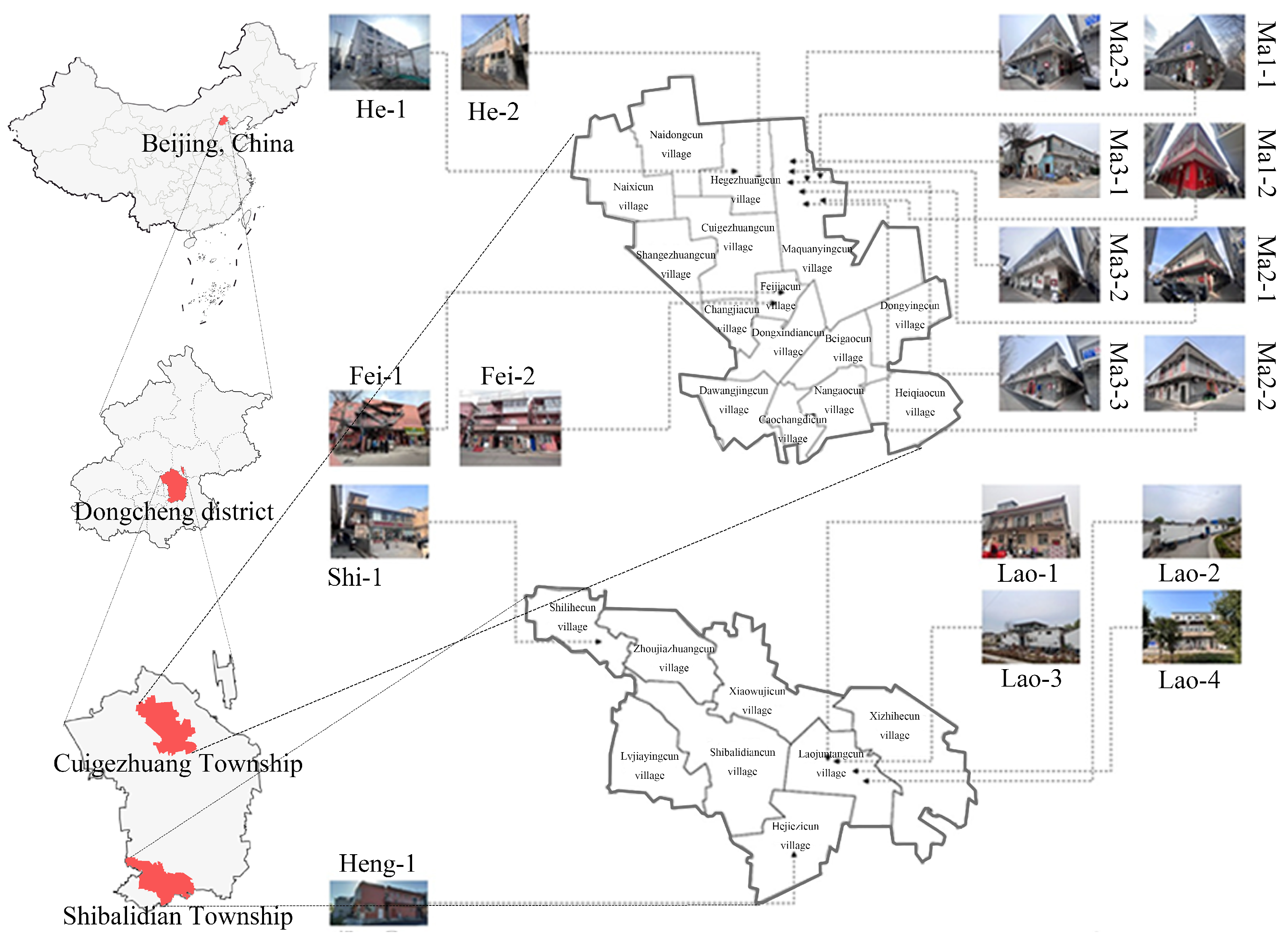

2. Study Area

3. Methods

3.1. Field Research and Building Mapping

3.2. Typological Analysis

3.3. Questionnaire and Kano Model for Tenants’ Needs Assessment Methods

4. Results

4.1. Architectural Characteristics of Urban Villages

4.1.1. High-Density Residential Buildings with Dilapidated Infrastructure

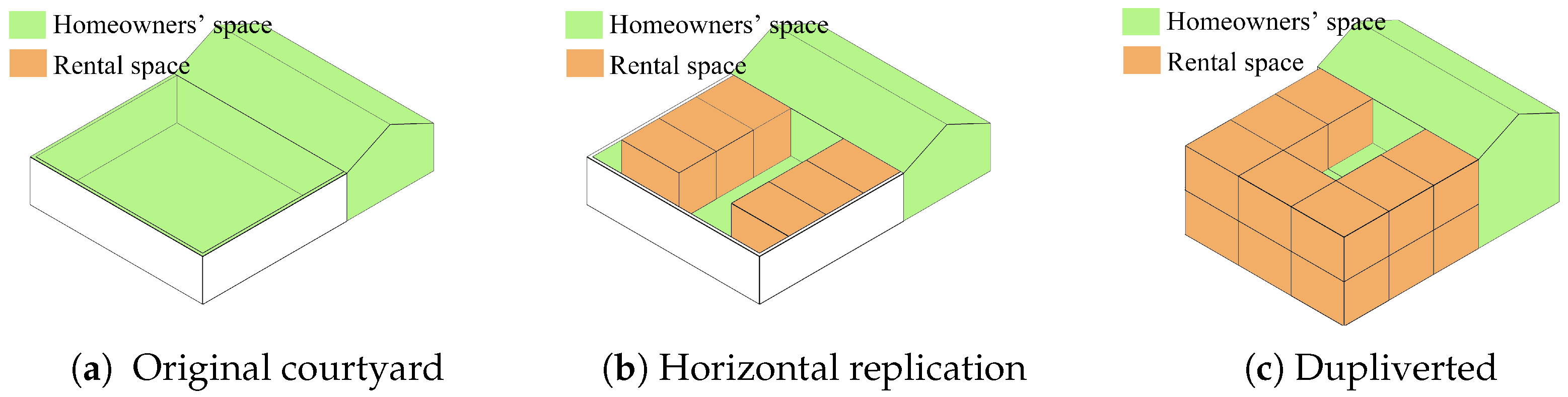

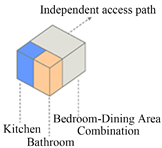

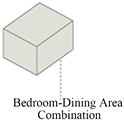

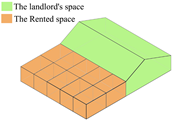

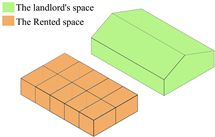

4.1.2. Spatial Composition of the Monolithic Building: Architectural Prototypes of “Homeowners’ Space” and “Rental Space”

4.2. Incremental Renovation

4.2.1. Three Stages of Incremental Renovation in Beijing’s Urban Villages

4.2.2. The Evolution of Architectural Space

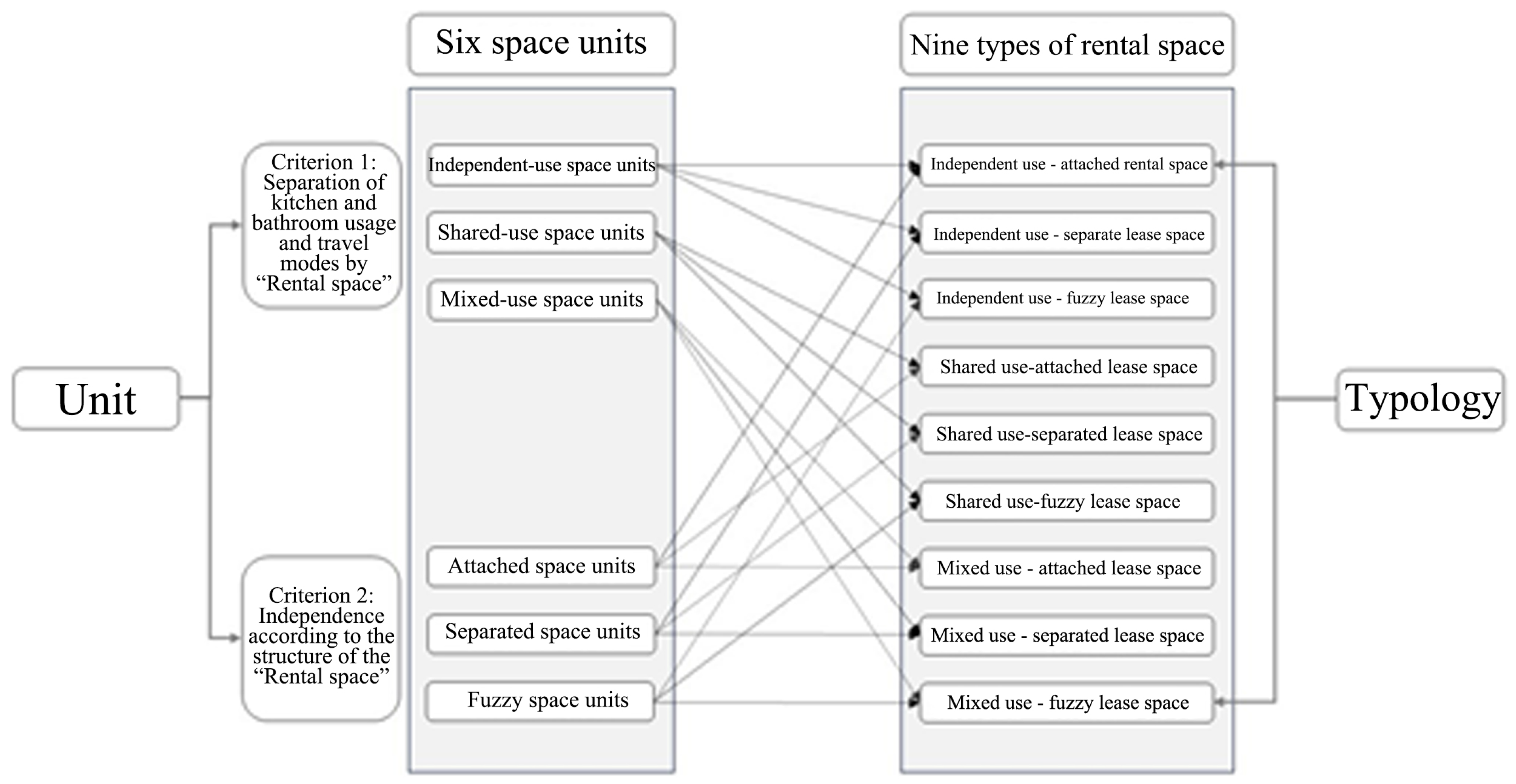

4.3. Analysis of Types of Rental Space

4.3.1. Six Basic Spatial Units

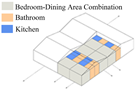

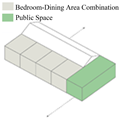

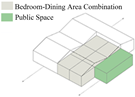

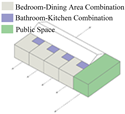

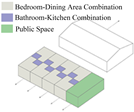

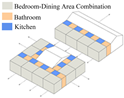

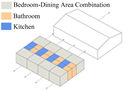

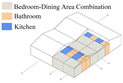

4.3.2. Nine Types of Rental Space

4.4. Tenants’ Needs Analysis

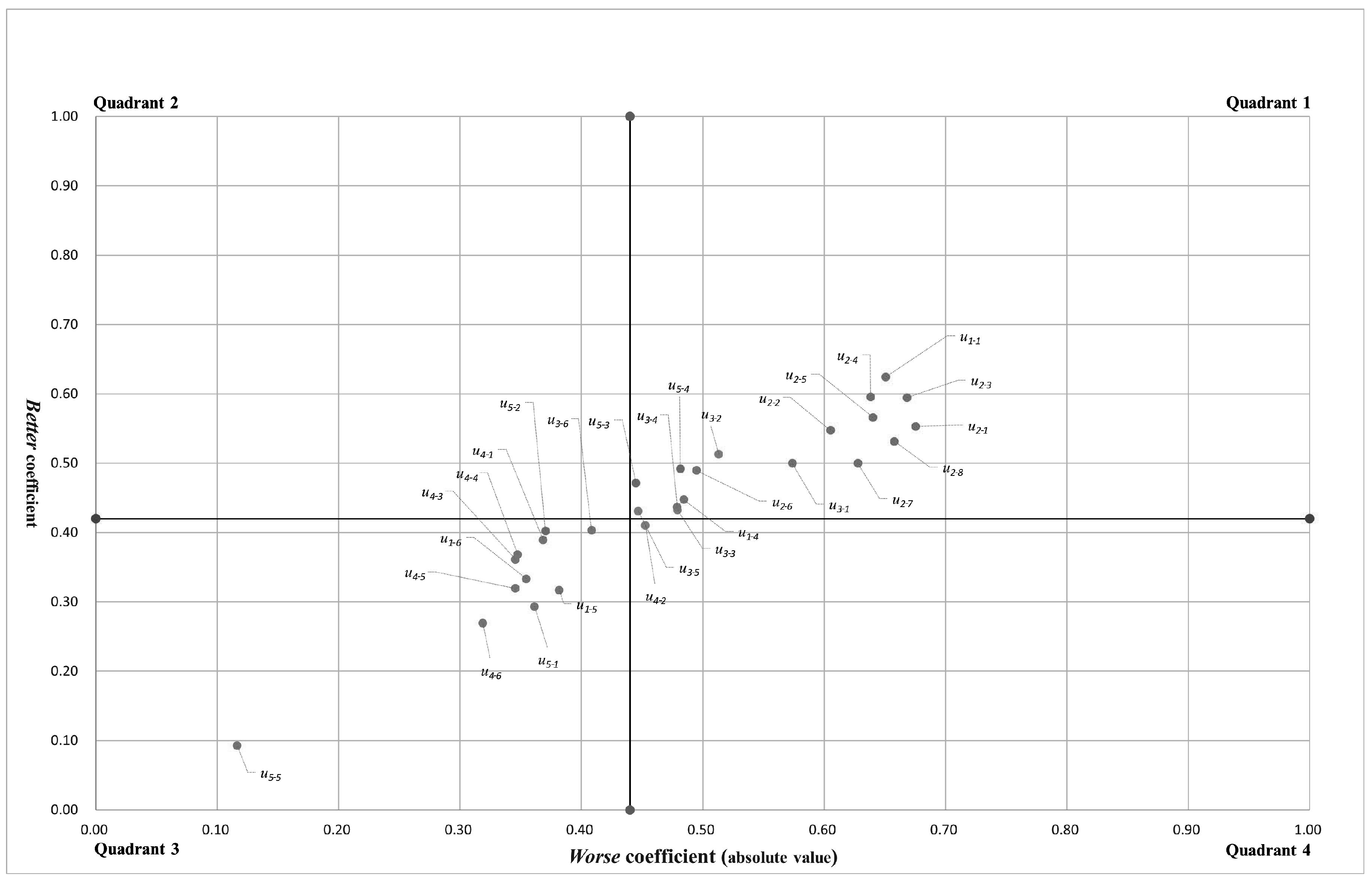

4.4.1. Kano Model Demand Types and Satisfaction Analysis for Shibalidian Township

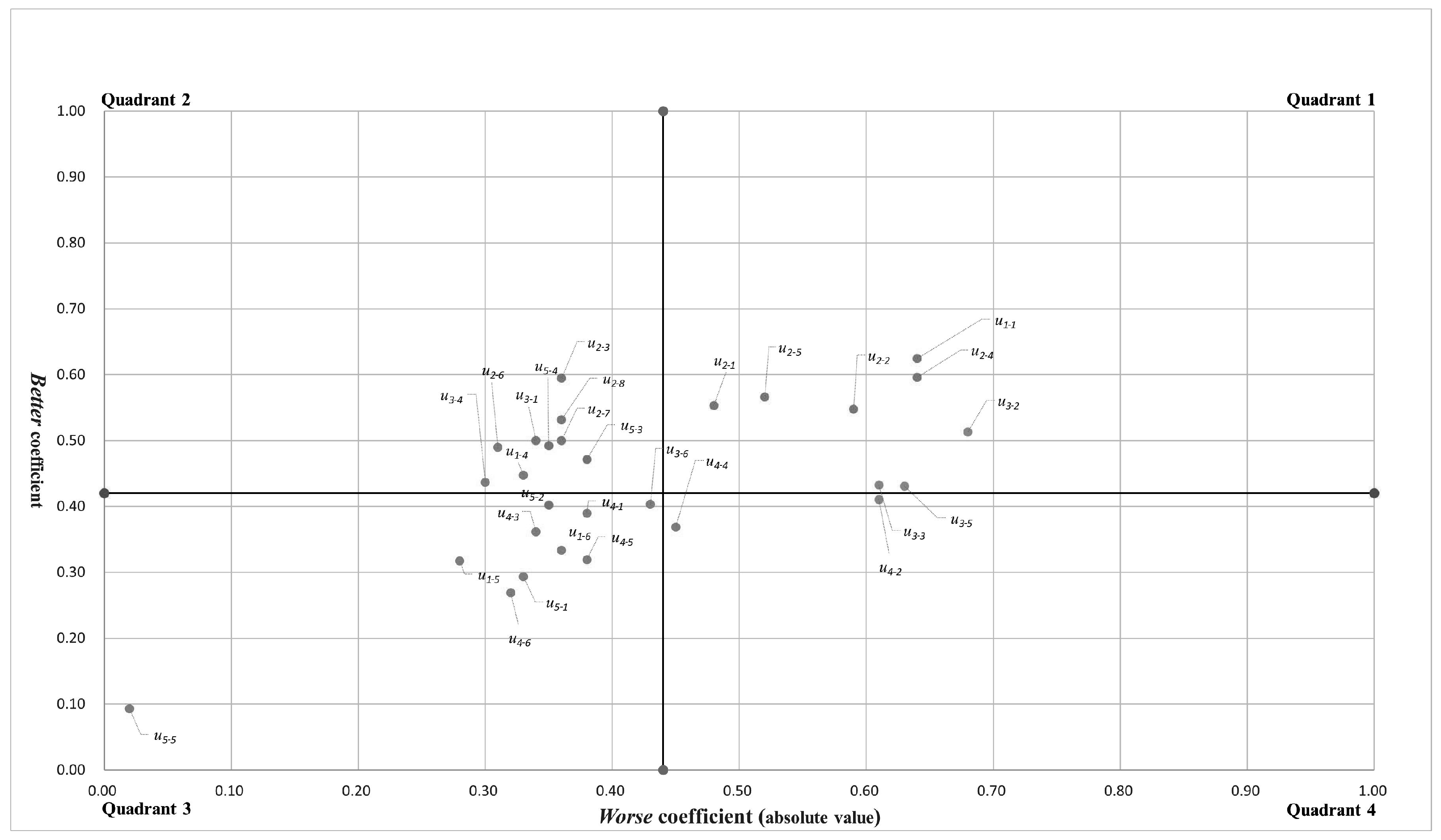

4.4.2. Kano Model Demand Types and Satisfaction Analysis in Cuigezhuang Township

4.4.3. Analysis of Tenants’ Needs and Building Type Matching for Rental Spaces in Urban Villages

4.4.4. The Relationship Between Rental Space Quality and Demand Fulfilment

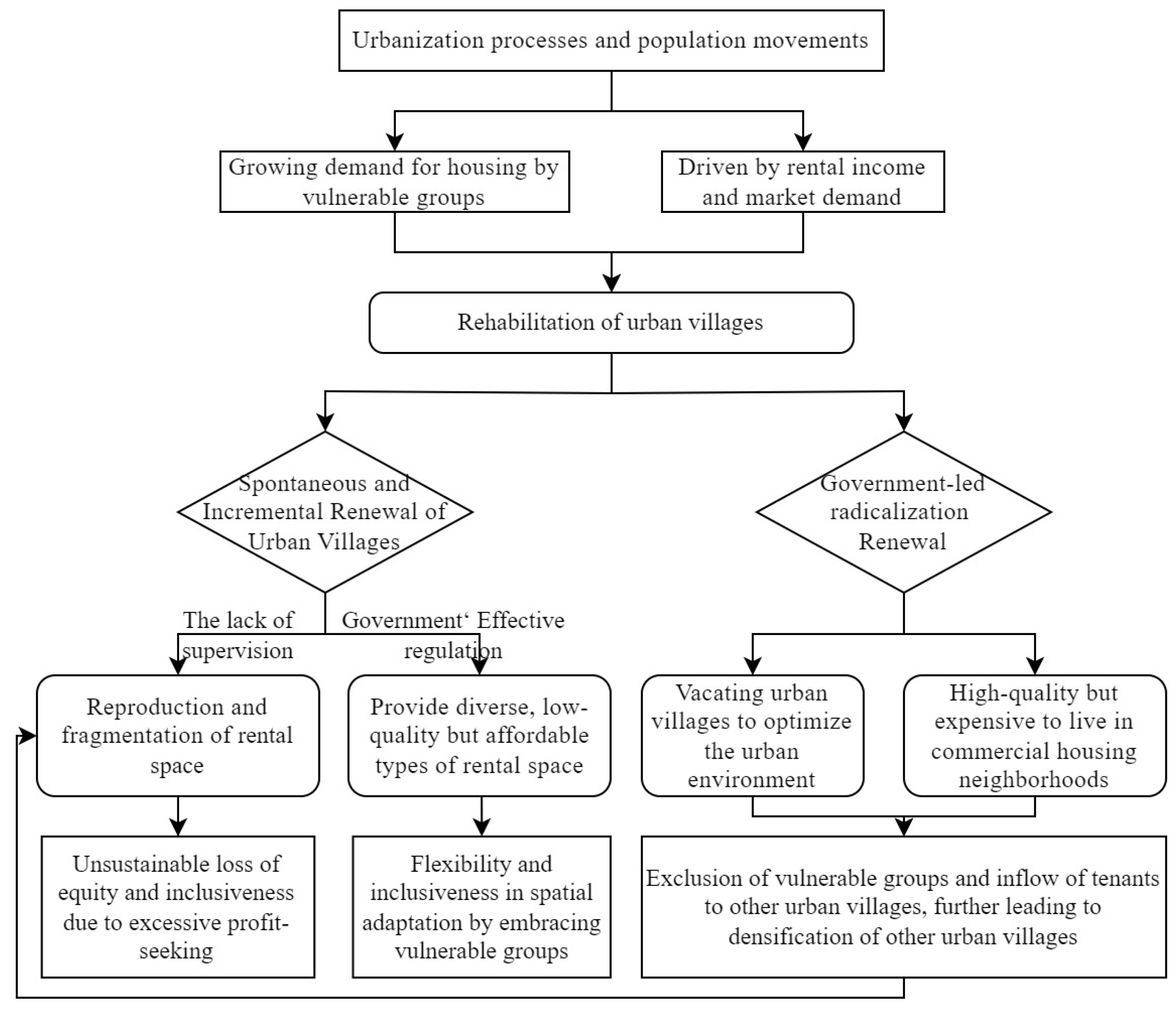

5. Discussion

5.1. Informal Settlements: Contributions and Challenges of Urban Villages

5.2. Mainstream Informal Settlement Renewal Methods

5.3. Inclusive Renovation Strategies

5.4. Economically Driven and Incremental Renovation

6. Conclusions

6.1. Exploring Inclusive Socio-Spatial Transformation and Incremental Renovation from the Perspective of Vulnerable Groups

6.2. Diversity in Rental Space Reflects Inclusiveness

6.3. Resident-Driven Incremental Micro-Renovation as a Complement to Urban Renewal

6.4. Policy Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Kano Model Evaluation Table for Leasing Space in Urban Villages in the Green Belt Area of Beijing City

| Question | Line Title/Option | Love it | Inevitable | Indifferent | Grudgingly | Dislike |

| Scores | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Q1: Area of rented premises | If the area is increased your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no increase in area your rating is: | ||||||

| Q2: Size of rental housing (number of households) | If there is an increase in size your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no increase in size your rating is: | ||||||

| Q3: Floor area ratio of the house (amount of density) | If there is an increase in floor area ratio your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no increase in floor area ratio your rating is: | ||||||

| Q4: Layout rationality of the house | If there is an increase in square footage your rating is: | |||||

| If it doesn’t enhance the layout rationality your rating is: | ||||||

| Q5: Area of common spaces in houses (foyers, corridors) | If there is an increase in square footage your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no increase in area your rating is: | ||||||

| Q6: Housing accessibility | If there is increased accessibility your rating is: | |||||

| If accessibility is not added your rating is: | ||||||

| Q7: Ventilation performance of the house | If there is an improvement in ventilation performance your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no improvement in ventilation performance your rating is: | ||||||

| Q8: Airtightness of doors and windows | If there is an improvement in door and window airtightness your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no improvement in door or window airtightness your rating is: | ||||||

| Q9: Winter protection of the house | If there is a boost in cold protection your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no improvement in cold protection your rating is: | ||||||

| Q10: Summer thermal performance | If there is an improvement in cooling performance your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no improvement in cooling performance your rating is: | ||||||

| Q11: Lighting performance | If there is an improvement in light performance your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no enhancement of light performance your rating is: | ||||||

| Q12: Number of indoor lighting fixtures | If there is an increase in the number of lighting fixtures your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no increase in the number of lighting fixtures your rating is: | ||||||

| Q13: Sound insulation performance | If there is an improvement in soundproofing performance your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no improvement in soundproofing performance your rating is: | ||||||

| Q14: Soundproofing of windows and doors | If there is an improvement in soundproofing performance your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no improvement in soundproofing performance your rating is: | ||||||

| Q15: Quality of noise protection materials | If the quality of the material is enhanced your rating is: | |||||

| If the quality of the material is not enhanced your rating is: | ||||||

| Q16: Kitchen and bathroom facilities | If there is an increase in the number of facilities your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no increase in the number of facilities your rating is: | ||||||

| Q17: Quality of facilities | If there is an improvement in facility quality your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no improvement in facility quality your rating is: | ||||||

| Q18: Number of electrical outlets | If there is an increase in the number of outlets your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no increase in the number of outlets your rating is: | ||||||

| Q19: Quality of electrical wiring | If there is an improvement in wiring quality your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no improvement in wiring quality your rating is: | ||||||

| Q20: Number of water points | If there is an increase in the number of water points your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no increase in the number of water points your rating is: | ||||||

| Q21: Quality of water supply pipes | If there is an improvement in pipe quality your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no improvement in pipe quality your rating is: | ||||||

| Q22: Internet accessibility | If there is an improvement in internet access your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no improvement in internet access your rating is: | ||||||

| Q23: Television signal accessibility | If there is an improvement in TV signal your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no improvement in TV signal your rating is: | ||||||

| Q24: Area of public green space | If there is an increase in green space area your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no increase in green space area your rating is: | ||||||

| Q25: Quality of public green space | If there is an improvement in green space quality your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no improvement in green space quality your rating is: | ||||||

| Q26: Area of public activity space | If there is an increase in activity space area your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no increase in activity space area your rating is: | ||||||

| Q27: Quality of public activity space | If there is an improvement in activity space quality your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no improvement in activity space quality your rating is: | ||||||

| Q28: Number of activity facilities | If there is an increase in the number of facilities your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no increase in the number of facilities your rating is: | ||||||

| Q29: Quality of activity facilities | If there is an improvement in facility quality your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no improvement in facility quality your rating is: | ||||||

| Q30: Non-motor vehicle parking | If there is an increase in quantity your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no increase in quantity your rating is: | ||||||

| Q31: Motor vehicle parking | If there is an increase in quantity your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no increase in quantity your rating is: |

References

- Zhang, L. The political economy of informal settlements in post-socialist China: The case of chengzhongcun(s). Geoforum 2011, 42, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, S.; Li, J. The dawn of vulnerable groups: The inclusive reconstruction mode and strategies for urban villages in China. Habitat Int. 2021, 110, 102347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandria, F. Inclusive city, strategies, experiences and guidelines. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 223, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacha, E.F.; Marin, M.V. Doubling up: Low income households sheltering the hidden homeless. J. Soc. Soc. Welfare 1993, 20, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durst, N.J.; Wegmann, J. Informal housing in the United States. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2017, 41, 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, P.; Gurran, N.; Maalsen, S. Informal housing practices. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2021, 21, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Menshawy, A.; Shafik, S.; khedr, F. Affordable housing as a method for informal settlements sustainable upgrading. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 223, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X. Governing the informal: Housing policies over informal settlements in China, India, and Brazil. Hous. Policy Debate 2018, 28, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Tao, R. Housing migrants in Chinese cities: Current status and policy design. Environ. Plan. Gov. Policy 2015, 33, 640–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Lamb, Z.; Qiu, X.C.; Cai, H.; Vale, L. Promises and perils of collective land tenure in promoting urban resilience: Learning from China’s urban villages. Habitat Int. 2018, 77, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; van Oostrum, M. The self-governing redevelopment approach of Maquanying: Incremental socio-spatial transformation in one of Beijing’s urban villages. Habitat Int. 2020, 104, 102235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, I.Y.; Luo, J.; Chan, E.H.W. Spatial justice in public open space planning: Accessibility and inclusivity. Habitat Int. 2020, 97, 102122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, S.; Borowiak, C.; Pavlovskaya, M.; Safri, M. Commoning and the politics of solidarity: Transformational responses to poverty. Geoforum 2021, 127, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Chan, E.H.W.; Choy, L. Village-led land development under state-led institutional arrangements in urbanising China: The case of Shenzhen. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 1736–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watters, S.M.; Ward, C.; Stuart, J. Does normative multiculturalism foster or threaten social cohesion? Int. J. Intercult. Relations 2020, 75, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, B.; Velkennedy, R. Spatial assessment on influence of land use and population density in the achievement score of sustainable development target 11.1. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESCAP, UN and Others. SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities. UN. ESCAP. 2023. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12870/5425 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Haase, D.; Kabisch, S.; Haase, A.; Andersson, E.; Banzhaf, E.; Baró, F.; Brenck, M.; Fischer, L.K.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Kabisch, N.; et al. Greening cities—To be socially inclusive? About the alleged paradox of society and ecology in cities. Habitat Int. 2017, 64, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, J. “They come in peasants and leave citizens”: Urban villages and the making of Shenzhen, China. Cult. Anthropol. 2010, 25, 421–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Zheng, W.; Hong, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, G. Paths and strategies for sustainable urban renewal at the neighbourhood level: A framework for decision-making. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 55, 102074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN General Assembly and others. Universal Declaration of Human Rights; UN General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 1948; Volume 302, pp. 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lerman, D.L.; Reeder, W.J. The affordability of adequate housing. Real Estate Econ. 1987, 15, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimmy, Eunice Nthambi and others. Reconsidering informality: Informal housing practices, illegal actors, and planning response strategies within middle-income neighbourhoods in Nairobi city, Kenya. Gran Sasso Science Institute. 2024. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12571/34285 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- PETRUCCIOLI, A. (n.d.). ossi: An Artist Challenges Typology. Available online: https://www.acsa-arch.org/proceedings/International%20Proceedings/ACSA.Intl.1999/ACSA.Intl.1999.68.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Li, J.; Li, C. Characterizing urban spatial structure through built form typologies: A new framework using clustering ensembles. Land Use Policy 2024, 141, 107166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropf, K. Aspects of urban form. Urban Morphol. 2009, 13, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovey, K. Informal urbanism and complex adaptive assemblage. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2012, 34, 349–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A. The Architecture of the City; The MITPress: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kropf, K.S. Conceptions of change in the built environment. Urban Morphol. 2001, 5, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniggia, G.; Maffei, G.L. Architectural Composition and Building Typology: Interpreting Basic Building; Alinea Editrice: Florence, Italy, 2001; Available online: https://books.google.co.jp/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=d0ggTlYc4rwC&oi=fnd&pg=PA9&dq=Caniggia+G,+Maffei+G+L.+Architectural+composition+and+building+typology:+interpreting+basic+building%5BM%5D.+Alinea+Editrice,+2001.&ots=A7BIm3KeSP&sig=PqpciNbIHzFOBS8R7slyQVi9c8M&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Al-Sabouni, M. Architecture with identity crisis: The lost heritage of the Middle East. J. Biourbanism 2016, 5, 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Memmott, P.; Davidson, J. Exploring a cross-cultural theory of architecture. Tradit. Dwellings Settlements Rev. 2008, 19, 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Malaque, I., III; Bartsch, K.; Scriver, P. Learning from Informal Settlements: Provision and Incremental Construction of Housing for the Urban Poor in Davao City, Philippines. In Living and Learning: Research for a Better Built Environment: 49th International Conference of the Architectural Science Association 2015; 2015; pp. 163–172. Available online: https://archscience.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/016_Malaque-III_Bartsch_Scriver_ASA2015.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Wang, Y.P.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J. Urbanization and informal development in China: Urban villages in Shenzhen. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 957–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, N.; Seraku, N.; Takahashi, F.; Tsuji, S. Attractive quality and must-be quality. J. Jpn. Soc. Qual. Control. 1984, 31, 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Li, S.; Juan, Y.-K.; Guo, H.; Lin, H. A Kano–IS Model for the Sustainable Renovation of Living Environments in Rural Settlements in China. Buildings 2022, 12, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ek, F.İ.; Çiğci, Ş. Integrating the Kano model into architectural design: Quality measurement in mass-housing units. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2015, 26, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.-H.; Tsai, S.-B.; Lee, Y.-C.; Hsiao, C.-F.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Shang, Z. Empirical research on Kano’s model and customer satisfaction. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Duan, W.; Dong, S. Research on Leased Space of Urban Villages in Large Cities Based on Fuzzy Kano Model Evaluation and Building Performance Simulation: A Case Study of Laojuntang Village, Chaoyang District, Beijing. Buildings 2024, 14, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, A.; Pourhamidi, M.; Antony, J.; Hyun Park, S. Typology of Kano models: A critical review of literature and proposition of a revised model. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2013, 30, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovey, K.; King, R. Forms of informality: Morphology and visibility of informal settlements. Built Environ. 2011, 37, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wong, T.-C. Urban village redevelopment in Beijing: The state-dominated formalization of informal housing. Cities 2018, 72, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, W.J.; Shester, K.L. Slum clearance and urban renewal in the United States. Am. Econ. Journal: Appl. Econ. 2013, 5, 239–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchadenyika, D.; Waiswa, J. Policy, politics and leadership in slum upgrading: A comparative analysis of Harare and Kampala. Cities 2018, 82, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samper, J. How Learning from Informal Settlements Contributes to the Community Resilience of Neighbourhoods. Built Environ. 2024, 50, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniz, G.C.; Andersson, I.; Hilding-Hamann, K.E.; Mateus, A.; Nunes, N. Inclusive urban regeneration with citizens and stakeholders: From living labs to the URBiNAT CoP. In Nature-Based Solutions for Sustainable Urban Planning: Greening Cities, Shaping Cities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 105–146. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, Y.; Li, X. Migration and urbanization in China: A case study of Beijing. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2013, 39, 231–254. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, T.; Liu, T. Housing and urbanization in China: A case study of Beijing. Habitat Int. 2018, 74, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.; Zhang, L. Urban redevelopment and rural urbanization in China: State-led formalization of informal housing. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 1920–1940. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Ren, J. Moving toward an inclusive housing policy?: Migrants’ access to subsidized housing in urban China. Hous. Policy Debate 2022, 32, 579–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galster, G.; Lee, K.O. Housing affordability: A framing, synthesis of research and policy, and future directions. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2021, 25, 7–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Chen, J. Market development, state intervention, and the dynamics of new housing investment in China. Journal of Urban Affairs 2019, 41, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z. Neighborhood environments and inclusive cities: An empirical study of local residents’ attitudes toward migrant social integration in Beijing, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 226, 104495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olin, C.V.; Berghan, J.; Thompson-Fawcett, M.; Ivory, V.; Witten, K.; Howden-Chapman, P.; Duncan, S.; Ka’ai, T.; Yates, A.; O’Sullivan, K.C. Inclusive and collective urban home spaces: The future of housing in Aotearoa New Zealand. Wellbeing, Space Soc. 2022, 3, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ma2-1 | Ma3-1 | Ma3-2 | Ma3-3 |

|  |  |  |

| Lao-1 | Lao-2 | He-1 | He-2 |

|  |  | |

| Fei-1 | Fei-2 | Shi-1 |

| Level 1 Indicators | Level 2 Indicators | Kano Model Category | Theoretical Construct |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic facilities for rental space (U1) | (u1-1) Area of rental space | One-dimensional (O) | Basic living needs |

| (u1-2) Size of rental housing (number of households) | Must-be (M) | Social equity and affordability | |

| (u1-3) Floor area ratio of the house (density level) | Reverse (R) | Environmental sustainability | |

| (u1-4) Layout rationality of the house | One-dimensional (O) | Spatial efficiency | |

| (u1-5) Area of common spaces in houses (foyers, corridors) | Must-be (M) | Community interaction | |

| (u1-6) Housing accessibility | Must-be (M) | Inclusivity | |

| Building performance of rental space (U2) | (u2-1) Ventilation performance of the house | One-dimensional (O) | Health and comfort |

| (u2-2) Closed doors and windows of the house | Must-be (M) | Safety and security | |

| (u2-3) Winter protection of the house | Must-be (M) | Basic living needs | |

| (u2-4) Summer thermal performance of the house | One-dimensional (O) | Health and comfort | |

| (u2-5) Lighting performance of the house | One-dimensional (O) | Health and comfort | |

| (u2-6) Number of indoor lighting fixtures | One-dimensional (O) | Health and comfort | |

| (u2-7) Sound insulation performance of walls and floors | One-dimensional (O) | Health and comfort | |

| (u2-8) Soundproofing performance of windows and doors | One-dimensional (O) | Health and comfort | |

| Quality of equipment in rental space (U3) | (u3-1) Quality of noise protection materials | One-dimensional (O) | Health and comfort |

| (u3-2) Number of light and ventilation facilities in kitchens and bathrooms | Must-be (M) | Basic living needs | |

| (u3-3) Quality of kitchen and bathroom electrical equipment | Must-be (M) | Basic living needs | |

| (u3-4) Safety and quality of housing renovation | Must-be (M) | Safety and security | |

| (u3-5) Number of housing security monitoring facilities | Must-be (M) | Safety and security | |

| (u3-6) Number of fire-fighting facilities in houses | Must-be (M) | Safety and security | |

| Facilities for outside activities in rental space (U4) | (u4-1) Area of outdoor space | Attractive (A) | Recreational needs |

| (u4-2) Number of outdoor wind and rain shelters | Attractive (A) | Recreational needs | |

| (u4-3) Number of outdoor street trees | Attractive (A) | Environmental quality | |

| (u4-4) Number of outdoor green separation belts | Attractive (A) | Environmental quality | |

| (u4-5) Number of public accessible facilities | Attractive (A) | Community interaction | |

| (u4-6) Number of public staircases | Attractive (A) | Accessibility | |

| External transport facilities for rental space (U5) | (u5-1) Width of outdoor pavement | Must-be (M) | Accessibility |

| (u5-2) Size of outdoor bicycle parking area | Attractive (A) | Transportation convenience | |

| (u5-3) Number of bus stops or metro stations | Attractive (A) | Transportation convenience | |

| (u5-4) Number of shared vehicles and parking spots | Attractive (A) | Transportation convenience | |

| (u5-5) Number of motor vehicle parking spaces | Attractive (A) | Transportation convenience |

| Demand Indicators | Evaluation Topics | Commentary Set Options (Points) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Love it (5) | Inevitable (4) | Indifferent (3) | Grudgingly (2) | Dislike (1) | ||

| Area of rental space (u1-1) | If there is an increase in square footage your rating is: | |||||

| If there is no increase in area your rating is: | ||||||

| The Building Does Not Provide a Functional Element | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demand Indicators | Love it | Inevitable | Indifferent | Grudgingly | Dislike |

| The Building Provides a Functional Element | Q | A | A | A | O |

| love it | Q | A | A | A | O |

| inevitable | R | I | I | I | M |

| indifferent | R | I | I | I | M |

| grudgingly | R | I | I | I | M |

| dislike | R | R | R | R | Q |

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prototypes of “homeowner space” | |||||

|  |  |  |  | |

| Lao-1 | Lao-2 | Ma3-2 | Ma3-3 | He-1 | |

| Single prototype of “rental space” | |||||

|  |  |  |  |  |

| Shi-1 | Ma2-1 | Ma3-1 | He-2 | Fei-1 | Fei-2 |

| Policy | Content |

|---|---|

| Circular of the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development on Preventing the Problem of Large-scale Demolition and Construction in the Implementation of Urban Renovation Actions, Jianke [2021] No. 63 | Instead of large-scale, piecemeal, and concentrated demolition of existing buildings, the demolition of building area within an urban renovation unit (district) or project should, in principle, not exceed 20 percent of the total building area of the existing building. It encourages the classification and prudent disposal of existing buildings and the implementation of small-scale, progressive organic renovation and micro-remodeling. |

| Beijing Urban Renovation Action Plan (2021–2025) 21 August 2021 | Through small-scale, progressive, and sustainable renovation and strict control of large-scale demolition and construction, we will promote the continuous improvement and optimization of urban functions and spatial forms. |

| Beijing Urban Renovation Special Plan (Beijing Urban Renovation Plan for the 14th Five-Year Plan Period) 10 May 2022 | Strictly controlling large-scale demolition and construction, realizing the renovation of residential categories such as bungalow compounds and old districts, and realizing the renovation of public services, transport, municipal, and security facilities through neighborhood coordination so as to enhance the carrying capacity of the city. |

| Type | Image | Features |

|---|---|---|

| independent-use space units |  |

|

| shared-use space units |  |

|

| mixed-use space units |  |

|

| attached space units |  |

|

| separated space units |  |

|

| fuzzy space units |  |

|

| Attached | Separated | Fuzzy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| independent-use |  |  |  |

| shared-use |  |  |  |

| mixed-use |  |  |  |

| Type | Spatial Unit | Sample | Key Features | Target Tenants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Code | Plan | |||

| 1. Independent use-Attached |  Independent use, attached structure Independent use, attached structure | Ma3-3 |  |

| Tenants who value privacy and living quality |

| Lao-1 |  | ||||

| 2. Independent Use - Separate |  Independent use, separate structure Independent use, separate structure | Ma2-1 |  |

| Tenants who value privacy but can accept some shared elements |

| Ma3-2 |  | ||||

| Fei-1 |  | ||||

| Fei-2 |  | ||||

| 3. Independent use—fuzzy |  Independent use, structurally complex Independent use, structurally complex | He-2 1F |  |

| Tenants who can accept partial sharing of facilities |

| He-2 3F |  | ||||

| 4. Shared use -Attached |  Shared use, attached structure Shared use, attached structure | He-2 2F |  |

| Low-income tenants who can accept shared facilities |

| 5. Shared use-Separate |  Shared use, separate structure Shared use, separate structure | Lao-2 |  |

| Tenants who need some independence but are rent-sensitive |

| Fei-1 2F |  | ||||

| Fei-1 3F |  | ||||

| 6. Shared use-fuzzy |  Shared use, structurally complex Shared use, structurally complex | Fei-1 |  |

| Rent-sensitive tenants who can accept poor environments |

| Fei-2 4F |  | ||||

| 7. Mixed use-attached |  Mixed use, attached structure Mixed use, attached structure | Ma3-1 |  |

| Tenants who value space utilization |

| 8. Mixed use-separate |  Mixed use, separate structure Mixed use, separate structure | Ma2-1 |  |

| Tenants who need a balance between rent and space utilization |

| Ma3-3 |  | ||||

| Fei-1 |  | ||||

| Fei-2 |  | ||||

| 9. Mixed Use - Fuzzy |  Mixed use, structurally complex Mixed use, structurally complex | Fei-2 |  |

| Rent-sensitive tenants who can accept poor environments |

| No. | Kano Requirements Attributes | Better Factor | Worse Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| u3-2 | M | 0.51 | −0.51 |

| u3-3 | M | 0.43 | −0.48 |

| u3-5 | M | 0.43 | −0.45 |

| u4-2 | M | 0.41 | −0.45 |

| u1-1 | O | 0.62 | −0.65 |

| u2-4 | O | 0.60 | −0.64 |

| u2-3 | O | 0.59 | −0.67 |

| u2-5 | O | 0.57 | −0.64 |

| u2-1 | O | 0.55 | −0.68 |

| u2-2 | O | 0.55 | −0.61 |

| u2-8 | O | 0.53 | −0.66 |

| u3-1 | O | 0.50 | −0.57 |

| u2-7 | O | 0.50 | −0.63 |

| u5-4 | A | 0.49 | −0.48 |

| u5-3 | A | 0.47 | −0.45 |

| u5-2 | A | 0.40 | −0.37 |

| u2-6 | I | 0.49 | −0.49 |

| u1-4 | I | 0.45 | −0.48 |

| u3-4 | I | 0.44 | −0.48 |

| u3-6 | I | 0.40 | −0.41 |

| u4-1 | I | 0.39 | −0.37 |

| u4-4 | I | 0.37 | −0.35 |

| u4-3 | I | 0.36 | −0.35 |

| u1-6 | I | 0.33 | −0.35 |

| u4-5 | I | 0.32 | −0.35 |

| u1-5 | I | 0.32 | −0.38 |

| u5-1 | I | 0.29 | −0.36 |

| u4-6 | I | 0.27 | −0.32 |

| u5-5 | I | 0.09 | −0.12 |

| u1-3 | R | 0.14 | −0.02 |

| u1-2 | R | 0.07 | −0.03 |

| No. | Kano Requirements Attributes | Better Factor | Worse Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| u2-5 | M | 0.49 | −0.68 |

| u2-7 | M | 0.45 | −0.61 |

| u2-4 | M | 0.44 | −0.63 |

| u2-1 | M | 0.43 | −0.61 |

| u2-3 | M | 0.43 | −0.64 |

| u2-2 | M | 0.39 | −0.64 |

| u1-4 | O | 0.69 | −0.36 |

| u2-6 | O | 0.52 | −0.48 |

| u2-8 | O | 0.49 | −0.59 |

| u1-5 | A | 0.75 | −0.36 |

| u1-1 | A | 0.73 | −0.34 |

| u3-5 | A | 0.64 | −0.36 |

| u5-3 | A | 0.60 | −0.35 |

| u3-3 | A | 0.59 | −0.38 |

| u4-2 | A | 0.58 | −0.35 |

| u4-1 | I | 0.61 | −0.31 |

| u4-3 | I | 0.58 | −0.33 |

| u5-2 | I | 0.56 | −0.30 |

| u3-4 | I | 0.56 | −0.43 |

| u1-6 | I | 0.55 | −0.38 |

| u3-2 | I | 0.54 | −0.45 |

| u5-4 | I | 0.54 | −0.34 |

| u4-4 | I | 0.53 | −0.36 |

| u3-6 | I | 0.51 | −0.38 |

| u5-1 | I | 0.47 | −0.28 |

| u4-5 | I | 0.46 | −0.33 |

| u4-6 | I | 0.45 | −0.32 |

| u5-5 | I | 0.08 | −0.02 |

| u1-3 | R | 0.11 | −0.09 |

| u1-2 | R | 0.11 | −0.06 |

| Type of Rental Space | Types of Quality Prioritized | Level 1 Demand Indicators | Tier 2 Demand Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent use–attached Independent use–separate | One-dimensional Quality (O) Must-be Quality (M) | Basic facilities for rental space (U1) | (u1-1) Area of rental space (u1-2) Size of rental housing (number of households) (u1-3) Floor area ratio of the house (density level) (u1-4) Layout rationality of the house |

| Building performance of rental space (U2) | (u2-1) Ventilation performance of the house (u2-2) Closed doors and windows of the house (u2-3) Winter protection of the house (u2-4) Summer thermal performance of house (u2-5) Lighting performance of the house | ||

| Quality of equipment in rental space (U3) | (u3-1) Quality of noise protection materials (u3-3) Quality of kitchen and bathroom electrical equipment | ||

| Independent use–fuzzy Shared use–attached Shared use–separated Shared use–fuzzy Mixed use–attached | Must-be Quality (M) | Building performance of rental space (U2) | (u2-1) Ventilation performance of the house (u2-2) Closed doors and windows of the house (u2-3) Winter protection of the house (u2-4) Summer thermal performance of house (u2-5) Lighting performance of the house |

| Mixed use–separated Mixed use–fuzzy | Must-be Quality (M) One-dimensional Quality (O) | Building performance of rental space (U2) | (u2-1) Ventilation performance of the house (u2-2) Closed doors and windows of the house (u2-3) Winter protection of the house (u2-4) Summer thermal performance of house (u2-5) Lighting performance of the house |

| Quality of equipment in rental space (U3) | (u3-1 Quality of noise protection materials (u3-3) Quality of kitchen and bathroom electrical equipment |

| Typology | Quality | Prioritizing Needs | Characterization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent use–separate | High | Must-be, One-dimensional | Separate kitchen and bathroom for good privacy and living conditions. |

| Independent use–attached | Relatively High | Must-be, One-dimensional | Connected to the ‘landlord’s space’, a little less independent, but well equipped. |

| Independent use–fuzzy | Medium | Partial Must-be, One-dimensional | The structure is complex, with some facilities separate and some shared. |

| Mixed use–separated | Medium | Partial Must-be, One-dimensional | Some of the facilities are shared and the living space is compact. |

| Shared use–separated | Medium | Partial Must-be, One-dimensional | Share some of the facilities but maintain a degree of independence. |

| Mixed use–attached | Relatively Low | Partial Must-be, One-dimensional | Shared facilities, high space utilization but low density and comfort. |

| Mixed use–fuzzy | Relatively Low | Partial Must-be, One-dimensional | Facilities and spaces are heavily shared and the quality of the environment is poor. |

| Shared use–attached | Relatively Low | Partial Must-be | Connected to a ‘landlord space’ with shared facilities. |

| Shared use–fuzzy | Low | Partial Must-be | There is a high degree of sharing of facilities and space and a lack of privacy. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duan, W.; Wei, L.; Huang, Y.; Cui, Z. Inclusive Socio-Spatial Transformation: A Study on the Incremental Renovation Mode and Strategy of Residential Space in Beijing’s Urban Villages. Buildings 2025, 15, 1755. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15101755

Duan W, Wei L, Huang Y, Cui Z. Inclusive Socio-Spatial Transformation: A Study on the Incremental Renovation Mode and Strategy of Residential Space in Beijing’s Urban Villages. Buildings. 2025; 15(10):1755. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15101755

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuan, Wei, Liuchao Wei, Yuexu Huang, and Ziqing Cui. 2025. "Inclusive Socio-Spatial Transformation: A Study on the Incremental Renovation Mode and Strategy of Residential Space in Beijing’s Urban Villages" Buildings 15, no. 10: 1755. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15101755

APA StyleDuan, W., Wei, L., Huang, Y., & Cui, Z. (2025). Inclusive Socio-Spatial Transformation: A Study on the Incremental Renovation Mode and Strategy of Residential Space in Beijing’s Urban Villages. Buildings, 15(10), 1755. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15101755