Study on the Evolution of Private Garden Architecture During the Song Dynasty

Abstract

1. Introduction

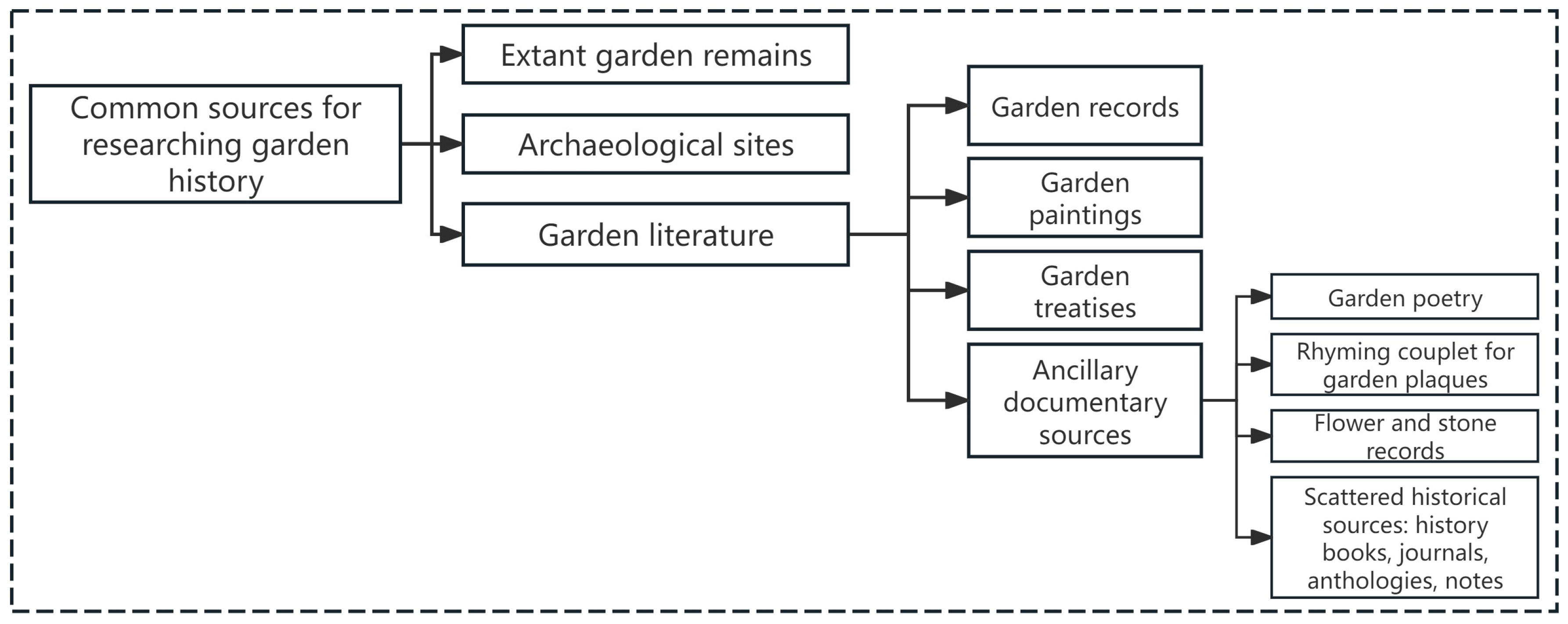

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reasons for Using Garden Records as Primary Research Materials

2.1.1. Limitations of Material Evidence

- Extinction of Physical Remains

- 2.

- Scarcity of Archaeological Data

2.1.2. Advantages of Garden Records

2.2. Critical Assessment and Utilisation of Other Song-Era Horticultural Literature

2.2.1. Landscape Painting Documentation

2.2.2. Garden Treatises

2.2.3. Ancillary Documentary Sources

- Garden Poetry

- 2.

- Literati Notebooks

2.3. Research Methodology

2.3.1. The Collection and Selection of Garden Records

2.3.2. Methodological Framework for Analysing Architectural Construction and Evolution in Garden Records

- Preliminary Processing of Architectural Data

- 2.

- Refined Screening of Architectural Data

- a.

- Garden records prioritising historical narratives over spatial descriptions;

- b.

- Garden records dominated by emotional expressions lacking architectural specifics;

- c.

- Accounts focused on singular scenic spots unless supplemented by complementary records from the same author.

- d.

- Garden records containing complete spatial metadata, documenting all landscape elements, their positional relationships, and material configurations.

- 3.

- Cliometric Analysis of Architectural Evolution in Private Gardens

2.3.3. Methodological Framework for Analysing Architectural Construction and Evolution in Other Horticultural Literature

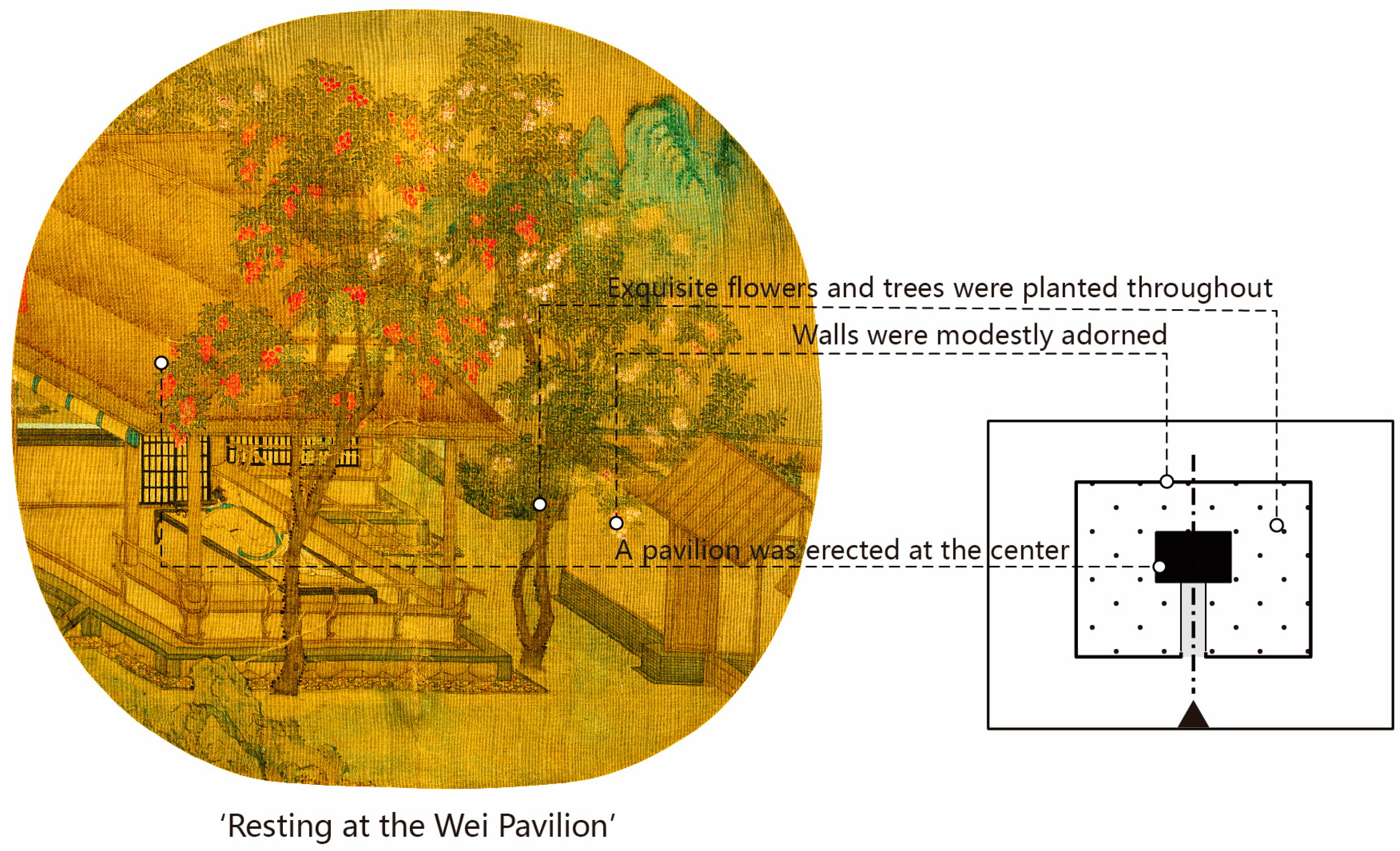

- The Collection and Selection of Landscape Painting Documentation

- 2.

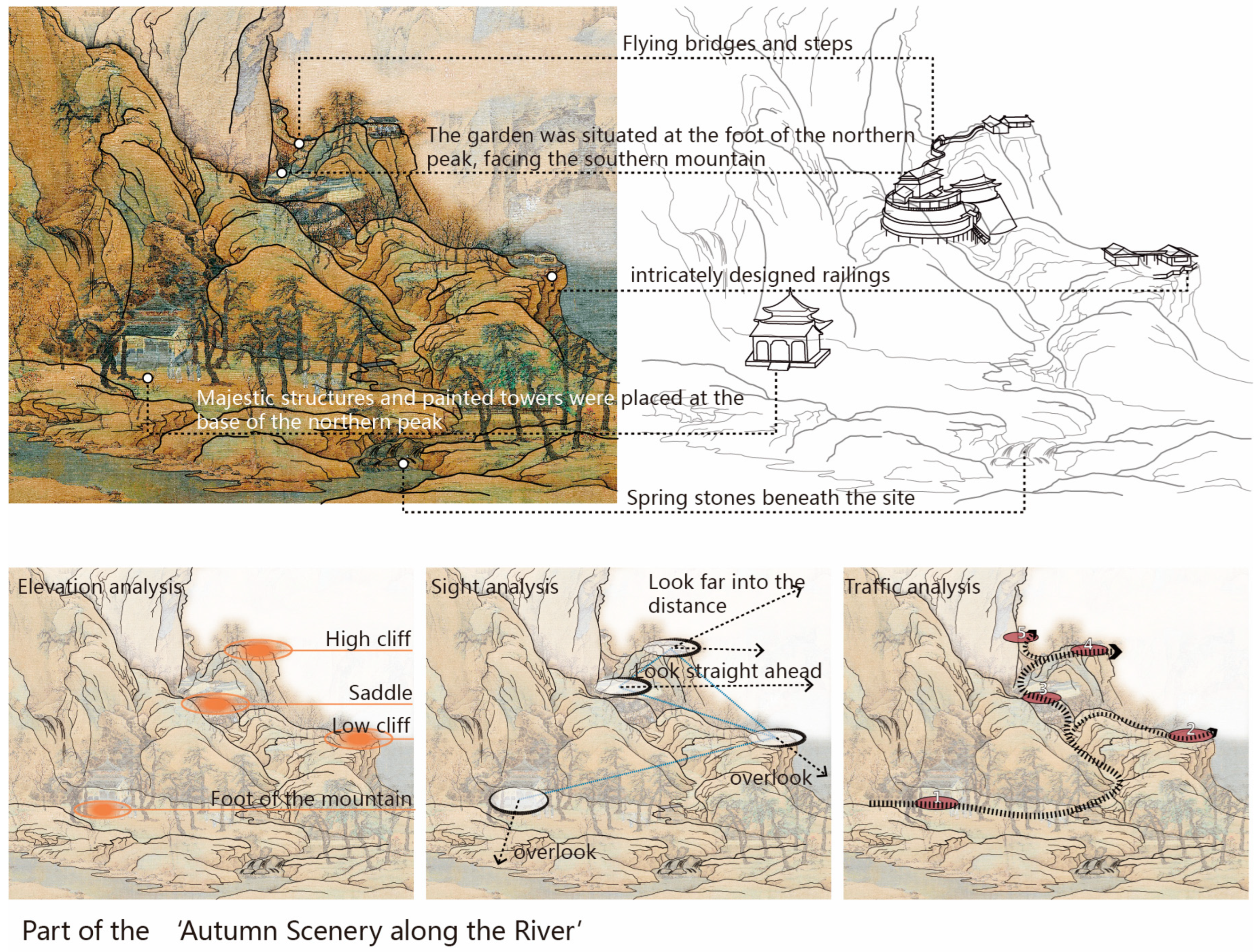

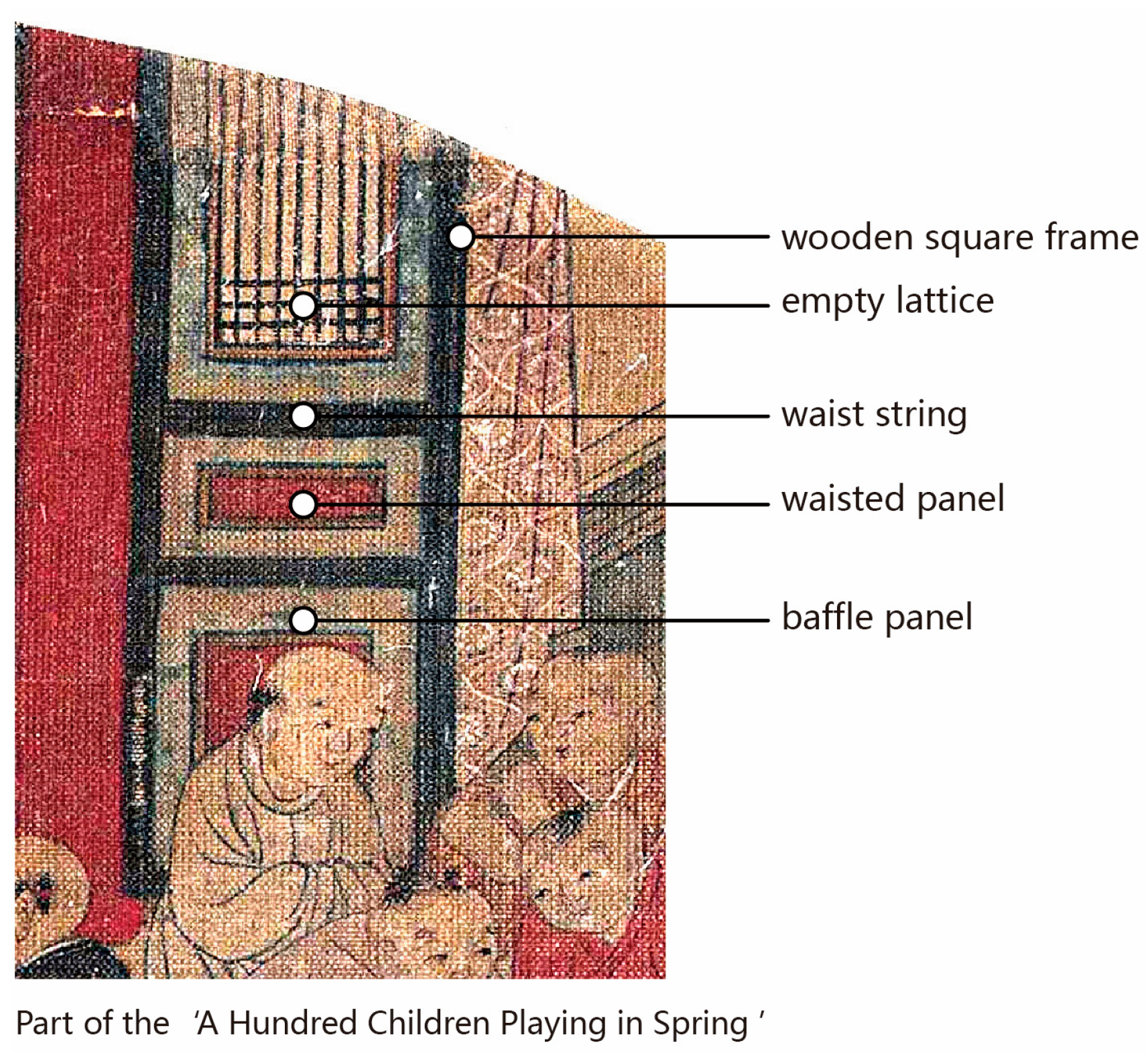

- Iconological Analysis of Private Garden Architectural Construction Evolution

3. Results

3.1. The Architectural Spatial Layout and Evolution of Private Gardens in the Song Dynasty

3.1.1. The Architectural Spatial Layout of Private Gardens in the Song Dynasty

- Flat and Dotted Layouts: Harmonious and Pleasing

- 2.

- Elevated and Terraced Layouts: Adapting to the Terrain

3.1.2. Evolution of Architectural Spatial Layout

3.2. Emergence and Significance of Unique Architectural Types in Song Dynasty Private Gardens

3.2.1. Emergence and Symbolic Significance of Boat-Shaped Buildings

3.2.2. Proliferation of Academies and High Buildings with Collections of Books in Private Gardens

3.3. Adaptations in Architectural Construction and Interior Furnishings

3.3.1. Diversification of Roof Forms and Upturned Eaves

3.3.2. Transformations in Exterior Decoration in Response to Climate

- The Expansion of Building Façades and Spaces Based on Changes in the Combination of Detachable Doors and Windows and their Components

- 2.

- Evolution of Railing Corner Construction Methods

3.3.3. Elevated Platforms

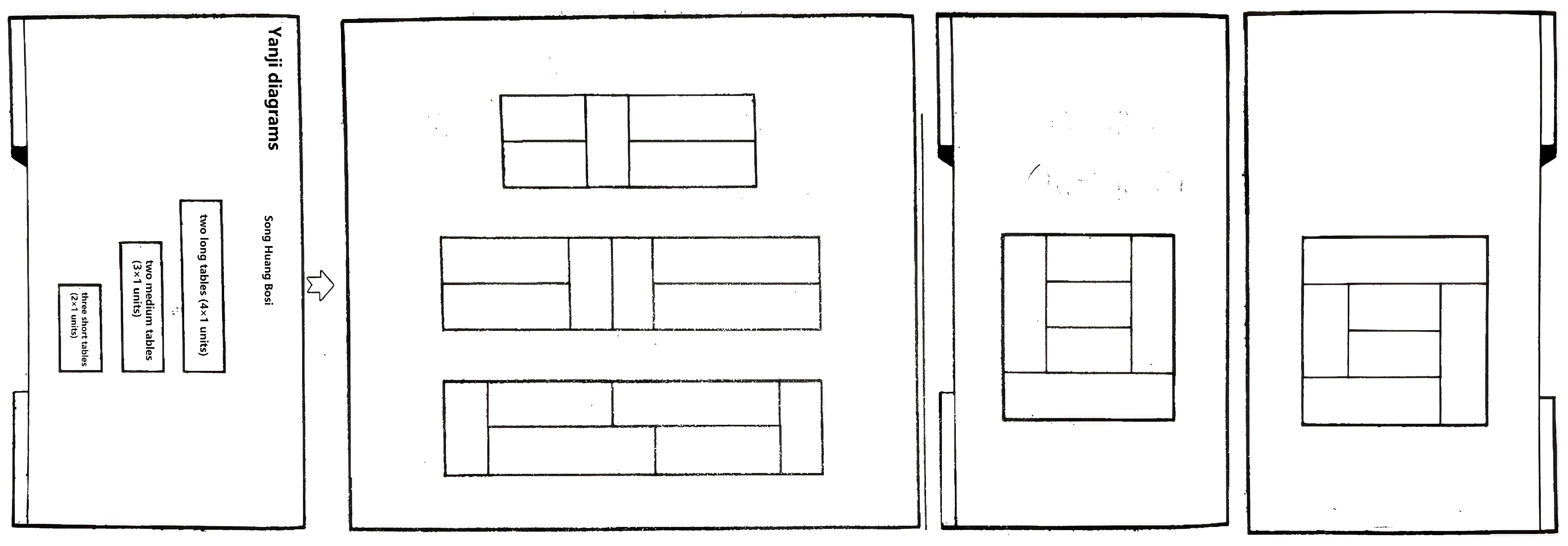

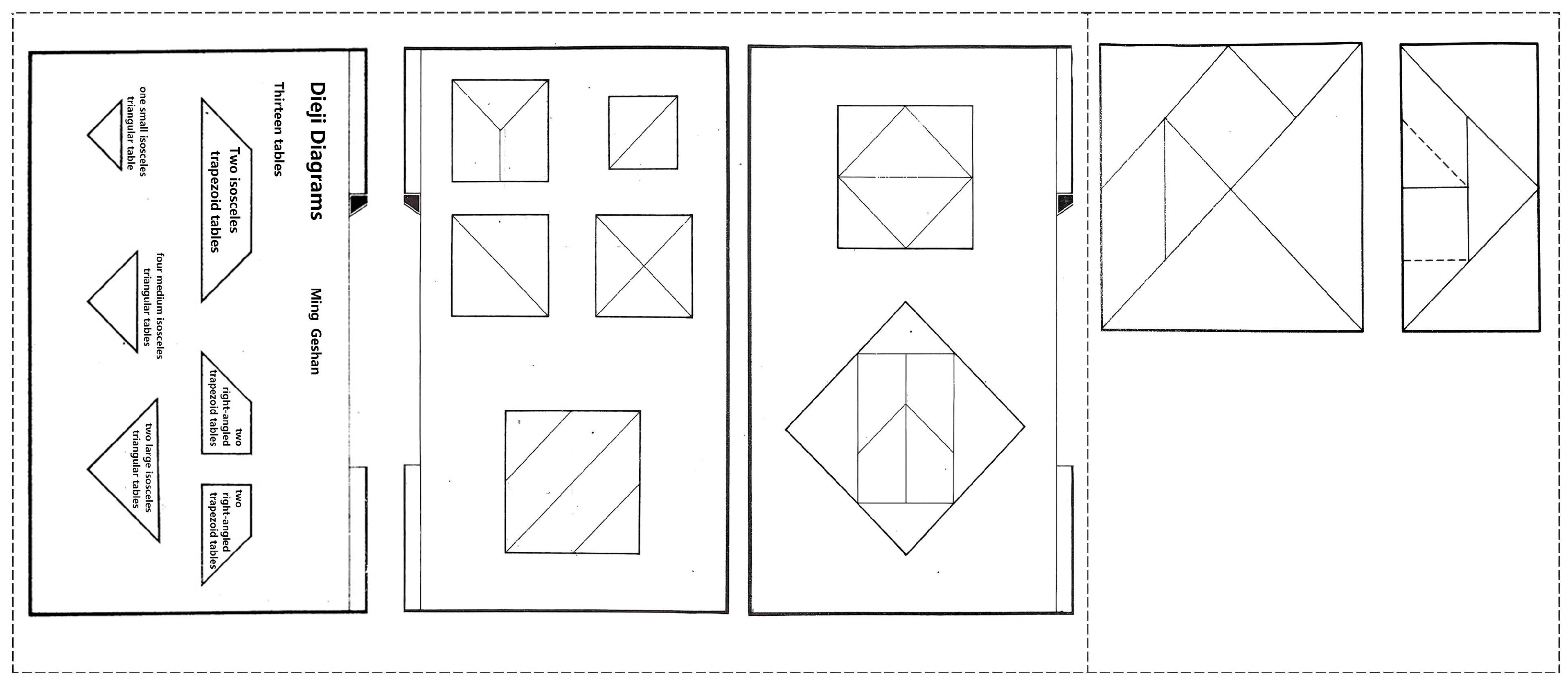

3.3.4. Modular Furniture Design

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Positioning and Historical Context of Research Findings

4.2. Cross-Cultural Comparisons and Theoretical Dialogue

4.3. Deeper Interpretation of Architectural Types and Cultural Motivations

4.4. Interaction Between Climate Change and Building Techniques

4.5. Contemporary Relevance and Heritage Conservation

4.6. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chao, B. Collection of the Rooster, Volume 30: A Record of the Qingmei Hall. In The Complete Works of Song; Sichuan University Institute of Antiquarianism, Ed.; Shanghai Dictionary Press: Shanghai, China, 2006; Volume 127, p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T. Garden Aesthetics; Yunnan People’s Publishing House: Kunming, China, 1989; p. 286. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D. History of Ancient Chinese Architecture, 2nd ed.; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, D. History of Southern Song Dynasty Architecture; Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, B. Great Song Dynasty Pavilions: Illustrated Song Architecture; Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, J. Features of architectures in ruler paintings during the Northern and Southern Song Dynasties. Art Mag. 2022, 2, 109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Q. The research of the evolution of the spatial boundaries of the literati’s residential and recreational buildings in the Song Dynasty based on the comparative study of architectures in Song Dynasty paintings. Archit. J. 2021, S2, 170–175. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. Regional characteristics of architecture in Song Dynasty house paintings. J. Nanjing Univ. Arts (Fine Arts Des.) 2021, 4, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Xu, X.; Xu, Y. On architectural form evolution and inter-area relations in Liangzhelu area in the Song Dynasty. Palace Mus. J. 2021, 10, 36–59+143–144. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. Study on the Evolution of Interior Spatial Pattern of Aristocracies’ Dwellings in Tang and Song Dynasties Based on Etiquette Literature. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hangzhou Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology. Site of the Residence of Empress Gongsheng Renlie of the Southern Song Dynasty; Cultural Relics Press: Beijing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhejiang Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology. A New Era of Archaeology in Zhejiang: Tongxiang Shimen East Garden Site; Science Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X. Northern Song architecture in Wang Ximeng’s Thousand Miles of Rivers and Mountains. Palace Mus. J. 1979, 7, 50–61+3. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, Y.; Tan, S. Complete Song Dynasty Notes; Series 2; Shanghai Normal University Institute of Ancient Books; Elephant Press: Zhengzhou, China, 2006; Volume 4, p. 206. [Google Scholar]

- Fogel, R.W.; Engelman, S.L. Slavery and the Revolution in Measurement Historiography. China Policy Rev. 2016, 10, 124–125. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Z.; Ying, T.; Ma, Q. Algorithm and Quantization in Historical Garden Research in Xinghua Village, Nanjing, in the Ming and Qing Dynasties. J. Nanjing For. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 5, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, F.; Qiu, Q.; Jiang, J.; Li, H. Research on Historical Garden from the Quantitative Perspectives. Zhuang Shi. 2021, 2, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Panofsky, E. Studies in Iconology: Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance; Qi, Y.; Fan, J., Translators; Shang Hai SDX Joint Publishing Company: Shanghai, China, 2011; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D. Collection of the Zhuyin, Volume 13: A record of the Yuchi’s garden. In The Complete Works of Song; Sichuan University Institute of Antiquarianism, Ed.; Shanghai Dictionary Press: Shanghai, China, 2006; Volume 138, pp. 244–245. [Google Scholar]

- Research Center for Ancient Chinese Painting and Calligraphy, Zhejiang University. Complete Collection of Song Paintings; Zhejiang University Press: Hangzhou, China, 2009; Volume 3-2, p. 179. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S. Collection of the Yanshan, Volume 15: A record of the Shuangyuan garden. In The Complete Works of Song; Sichuan University Institute of Antiquarianism, Ed.; Shanghai Dictionary Press: Shanghai, China, 2006; Volume 103, pp. 315–316. [Google Scholar]

- Research Center for Ancient Chinese Painting and Calligraphy, Zhejiang University. Complete Collection of Song Paintings; Zhejiang University Press: Hangzhou, China, 2010; Volume 1–4, pp. 44, 86–107. [Google Scholar]

- He, J. The unmoored boat—A discussion on garden stone boats. Tradit. Chin. Archit. Gard. 2011, 2, 55–57+32+68. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; You, J. Study on the Boat-Shaped Buildings; Tongji University Press: Shanghai, China, 2015; p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, X. Collection of Ouyang Wenzhong Gong, Volume 39: Records of the painting boat pavilion. In The Complete Works of Song; Sichuan University Institute of Antiquarianism, Ed.; Shanghai Dictionary Press: Shanghai, China, 2006; Volume 35, pp. 107–108. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Z. Inscription on Huazhou painting boat pavilion for scholar Li Gongze. In Collection of the Luancheng; 1368–1644; Volume 3.

- Su, Z. In response to Mao Jun’s newly built Qun An boat pavilion. In Collection of the Luancheng; 1368–1644; Volume 11.

- Li, G. Records of the Famous Gardens of Luoyang; 1368–1644.

- Zhou, M. Miscellaneous Notes in Guixin: Wuxing Gardens; 1781.

- Hong, S. The Second poetic form of Yizhai. In Collection of the Spiraling Island; 1644–1911; Volume 6.

- Yang, W. Sleeping tiredly in fishing snow boat. In Collection of the Honest Pavilion; 1621–1644; Volume 7.

- Xu, J. Record of the Fragrant Faraway Boat. In Ju Shan Cun Gao; 1644–1911; Volume 3.

- Chen, Z. Zhang Pavilion. In Collection of the Vagrant; 1618; Volume 8.

- Chen, W. Building a boat pavilion in the two pools, the name “Lying Pavilion”. In Collection of the Ke Zhai; 1644–1911; Volume 14.

- Chen, Z. In response to Sun Changzhou’s Feipeng Pavilion. In Collection of the Ben Hall; 1893; Volume 18.

- Zhao, X. The Zen’s Origin and Connotation of Classical Chinese Garden; Tianjin University Press: Tianjin, China, 2016; pp. 278–372. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, H. History of Chinese Academies, rev. ed.; Wuhan University Press: Wuhan, China, 2012; p. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X. History of the Development of Ancient Chinese Academies; Tianjin University Press: Tianjin, China, 1995; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X. Collection of Zhu Wengong, Volume 69: Private discussion on school and imperial examinations. In The Complete Works of Song; Sichuan University Institute of Antiquarianism, Ed.; Shanghai Dictionary Press: Shanghai, China, 2006; Volume 251, pp. 270–278. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X. Collection of Zhu Wengong, Volume 78: Records of the cloud valley. In The Complete Works of Song; Sichuan University Institute of Antiquarianism, Ed.; Shanghai Dictionary Press: Shanghai, China, 2006; Volume 252, pp. 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, B. Collection of the best writings of 200 famous scholars of the current dynasty, Volume 121: Records of Yu’s high building with a collection of books. In The Complete Works of Song; Sichuan University Institute of Antiquarianism, Ed.; Shanghai Dictionary Press: Shanghai, China, 2006; Volume 184, pp. 407–408. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F. The Transformation of Tang and Song and the Evolution of Aesthetic Culture in the Song Dynasty; Xuelin Press: Shanghai, China, 2009; p. 263. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G. General principles of learning, Zhu Zi says. In Imperially Edited Essence of the Study of Human Nature and Reason; 1715; Volume 7.

- Fu, B. A brief discussion on the architectural techniques of the Southern Song Dynasty. Zhejiang Arts Crafts 1994, 3, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J. The Restoration Research of Some Buddhist Temple Halls from the Recording Documents of Two Song Dynasties. Master’s Thesis, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, H. Research on Architecture of the Landscape Paintings Between Northern Song Dynasty & Southern Song Dynasty. Master’s Thesis, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, B. Southern Song Dynasty Architecture in Song Paintings; Xiling Seal Engraver’s Society Press: Hangzhou, China, 2011; pp. 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Research Center for Ancient Chinese Painting and Calligraphy, Zhejiang University. Complete Collection of Song Paintings; Zhejiang University Press: Hangzhou, China, 2010; Volume 1–7, pp. 47, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X. On the dating of several paintings attributed to the Li Sixun school of gold and azure landscapes. Cult. Relics 1983, 11, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, C.; Bian, J. Complete Song Dynasty Notes; Series 4; Shanghai Normal University Institute of Ancient Books; Elephant Press: Zhengzhou, China, 2008; Volume 7, p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, M. Architectural Research of Dunhuang Grottoes; Cultural Relics Press: Beijing, China, 1989; pp. 210–214. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Q. The Research of Exterior Components and Space Under the Roof of Asian Timber Architectures-Using the Paintings in Southern Song Dynasty as Basic Materials. Master’s Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2018; p. 98. [Google Scholar]

- Research Center for Ancient Chinese Painting and Calligraphy, Zhejiang University. Complete Collection of Song Paintings; Zhejiang University Press: Hangzhou, China, 2008; Volume 6-1, p. 186. [Google Scholar]

- Research Center for Ancient Chinese Painting and Calligraphy, Zhejiang University. Complete Collection of Song Paintings; Zhejiang University Press: Hangzhou, China, 2015; Volume 5-2, p. 149. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B.; Ge, S. Reprinting Yanji Diagrams, Dieji Diagrams, and Kuangji Diagrams; Shanghai Scientific & Technical Publishers: Shanghai, China, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B. Objects and Minds: Gardens in China; SDX Joint Publishing Company: Beijing, China, 2014; pp. 84–171. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. Institutionalisation. In Ce Fu Yuan Gui; 1644–1911; Volume 61.

- Oktay, D. Design with the climate in housing environments: An analysis in Northern Cyprus. Build. Environ. 2002, 10, 1003–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Architectural Spatial Layout | Northern Song Dynasty | Southern Song Dynasty | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garden Name | Number (%) | Garden Name | Number (%) | |

| Flat and dotted layouts: harmonious and pleasing | Canglang Pavilion, Garden of Pleasure in Solitude, Jiuhua Medicine Garden, Pleasant Garden, Guiren Garden, Pine Island, Lake Garden, Ring Creek Garden, Fu Zheng Garden, Miao Shuai Garden, Congchun Garden, Leisure Pavilion, Respect Pavilion, Bamboo Pavilion, Dezhi Pavilion, Yuchi Garden, Yilao Pavilion, Yingpo Pavilion, Conggui Hall | 19 (76%) | Cuiwei Hall, Yongzhou Enjoying Gull Pavilion, Fishing Perch Terrace, Planting Osmanthus Hall, Four Elder Hall, Qingping Pavilion, Plum Garden, Green Painting Pavilion, Spiralling Island, Zhijie Hall, Bamboo Island, Xianglin Garden, Zheng’s North Wild Garden, Endless Garden, Zhang Xifang’s Mountain View Pavilion, He Ke’s West Garden, Feilai Garden, Double-Peaked Hall, Quietly Viewing Pavilion, Mountain Moon Pavilion, Yang’s Book-Collecting Hall, Lanxun Hall, South Stream Zhangyin Garden, Plum Pavilion, Yu’s Garden | 25 (64%) |

| Elevated and terraced layouts: adapting to the terrain | Qiuxiang Pavilion, Mengxi Garden, Snow Hall, Huangzhou Carefree Pavilion, Shuangyuan Garden, Hu’s Garden north of the river | 6 (24%) | Ye’s Stone Forest Garden, Taoist Hermitage Garden, Biyun Pavilion, Youben Pavilion, Siluo Pavilion, Cui Jiayan’s Garden, Shuangxi Garden, Mo Nengming Pavilion, Hong’s Ke Pavilion, Bamboo Slope, Lingyuan Tianjing Garden, New Pavilion, Zhao’s Suwan Garden, Yi Pavilion | 14 (36%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kang, Q.; Huang, M. Study on the Evolution of Private Garden Architecture During the Song Dynasty. Buildings 2025, 15, 1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081323

Kang Q, Huang M. Study on the Evolution of Private Garden Architecture During the Song Dynasty. Buildings. 2025; 15(8):1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081323

Chicago/Turabian StyleKang, Qi, and Mingjin Huang. 2025. "Study on the Evolution of Private Garden Architecture During the Song Dynasty" Buildings 15, no. 8: 1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081323

APA StyleKang, Q., & Huang, M. (2025). Study on the Evolution of Private Garden Architecture During the Song Dynasty. Buildings, 15(8), 1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15081323