Abstract

Urban planning in the 1950s laid the foundation for innovative urban and architectural practices, not only by investigating the spatial and constructive aspects of housing, but also by attempting to expand and improve free green spaces. This paper aims to go deep into the theoretical principles of two Lisbon neighborhoods recognized as urban paradigms on public housing, namely, the Olivais Norte and Olivais Sul (1954–1964), trying to perceive a concept of living that interweaves the private and public dynamics through the green spaces. Digging into the municipal archives, the paper sheds light on the Gabinete de Estudos de Urbanização (GEU) (Urban Studies Office, 1954–1959) urbanistic contributions through its development of the 1959 Lisbon Master Plan and the creation of more than 100 urbanization plans for Lisbon. The Olivais were the only ones implemented, even though it underwent considerable transformations. The GEU vision for Lisbon included a population of up to 1,100,000 inhabitants and a green space ratio of 55 m² per inhabitant. The built Lisbon struggles to provide housing for approximately 534,000 inhabitants, with a green space ratio of 36 m² per inhabitant. Critically analyzing the (mis)steps of Lisbon’s planning processes through the lens of the 1950s experience can help guide current decisions and chart future paths.

1. Introduction

With a population of approximately half a million inhabitants, Lisbon faces, in the second decade of the 21st century, one of its most significant housing crises. The city has become increasingly inaccessible, particularly for its younger residents seeking dignified housing. This current difficulty in accessing housing results from an unrelenting process of real estate speculation. Addressing this reality cannot be limited to contemplating new constructions; it must also include policies that restore residential use to vacant properties and consider new ways of inhabiting and shaping the city.

The housing policies of the past century should serve as a foundation for calibrating new solutions, both in terms of governance and urban design. Within this historical timeframe, the historiography of Lisbon’s 20th century urban and architectural history recognizes the Olivais neighborhoods as an urban paradigm. These neighborhoods exemplify 1950s planning practices that advocated for innovative urban and architectural approaches—not only through spatial and constructive investigations of housing, but also in the attempt to expand and enhance free green spaces. This urban planning policy and urban form was linked to the international scenario, particularly with the planning practice in England and theoretical ideas advocated by modern architects such as Le Corbusier and promoted by the Congrès International d’Architecture Modern (CIAM).

Teresa Marat-Mendes and Maria Amélia Anastácio [1] identified the Olivais as a cornerstone in the development of a new paradigm for public housing promotion at the turn of the 1950s, “following the publication of Decree-Law No. 42,454 [August 1959], the social housing paradigm was reconfigured, resulting in the emergence of a new urban model and landscape within Lisbon’s administrative boundaries, with a focus on high-rise construction and typologies inspired by the Modern Movement. An architectural and urban planning approach that had previously been tested in a few private initiatives.”

In a recent publication on the achievements of a “Modern Lisbon” (the Lisbon of the mid-20th century), Tostões [2] highlighted the specificity of the Olivais neighborhoods through two main elements: “firstly, the urban area became a collective asset; secondly, construction was subordinated to a unified plan.”

The current literature has indeed proposed the Olivais (Norte and Sul) as reference cases of a built environment that presents a new approach to habitation—not only at the scale of domestic space, but also in the relationship between private and public domains. This perspective underscores that expanding the concept of habitation to the collective sphere is fundamental to sustainable human development. The conception of these neighborhoods is frequently attributed to the Technical Housing Office (Gabinete Técnico de Habitação—GTH/CML), disregarding the role of the Urban Studies Office (Gabinete de Estudos de Urbanização—GEU/CML). However, what these studies fail to reveal—and thus do not discuss—is that these neighborhoods were the only materializations of an urban planning model that imagined Lisbon as a territory capable of housing a population of approximately one million inhabitants.

In the context of the Estado Novo authoritarian regime (1936–1974), absences often communicate more than recurrent presences. Regarding urban planning in Lisbon, there is a troubling gap concerning the period between 1954 and 1959. This discomfort is justified not only because this interval was part of a decade marked by profound cultural, political, and economic changes on a global scale but also because this period (though brief) was characterized by intense urban planning activity carried out by the Lisbon City Council. This activity not only defined a new Master Plan, but also generated a series of partial plans capable of creating new urban compositions. Thus, this troubling gap does not signify an actual absence of planning.

2. Materials and Methods

In search of this missing piece, this research investigated the activities of the Urban Studies Office through key members of its team, including chief engineer Luís Guimarães Lobato (1915–2008) and licensed architects Pedro Falcão e Cunha (1922–1982), José Aleixo da França Sommer Ribeiro (1924–2006), Frederico Duff de Carvalhosa e Oliveira (1924–1975), and Fernando Ressano Garcia (1927–2016), who were involved in the urbanization plans referenced in this paper. The analysis of the 1959 Lisbon Master Plan (PDUL de 1959) complemented this current analysis. Understanding the principles of that planning effort, its urban proposals, and the factors that led to its obliteration can offer valuable contributions to developing strategies to address Lisbon’s current housing crisis.

The hypothesis is that the Olivais neighborhoods were not an isolated endeavor but rather the only feasible outcome of a city model proposed by the 1959 Lisbon Master Plan (PDUL from 1959) as part of urban studies conducted by the technical team of the Urban Studies Office (Gabinete de Estudos de Urbanização—GEU/CML). Through an intensive and meticulous investigation of primary sources in Lisbon’s public archives, this study reveals and analyzes some of the urban studies proposed between 1954 and 1959 using the guidelines established in the PDUL of 1959. These studies undoubtedly illustrate a Lisbon that “could have been”, envisioned under the principles of constructing a heterogeneous social fabric within a territory integrated by a connective network of free green spaces.

In order to assess the transformations of Olivais’ design over time, the primary documents were analyzed in light of the critical revision of Modern Movement architectural and urban principles addressed by the Portuguese architects by that time.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Gabinete de Estudos de Urbanização (GEU/CML, 1954–1959)

Two decades after the legislation mandating the preparation of General Urbanization Plans (1934), Lisbon was still working on getting its plan approved. The establishment of the Urban Studies Office (GEU/CML) was intended to complete the cycle of investment in urban intervention and planning actions. On 18 January 1954, through Decree-Law 5.621, the new office was created under the Directorate of Urbanization and Works Services (DSUO/CML), with a multidisciplinary technical team composed of engineers, architects, landscape architects, historians of Lisbon, and social studies specialists, facilitating collaboration among the various departments within the Directorate. During its five years of operation (1954–1959), the GEU/CML employed a total of 15 architects, with the longest-serving being Pedro Falcão e Cunha (March 1954 to November 1959) and José Sommer Ribeiro (November 1954 to July 1958). As part of the Lisbon City Council’s organizational structure, this new entity served as a link between the state and the municipality, ensuring compliance with higher directives.

The GEU/CML’s mission was to coordinate the revision of the Lisbon Master Plan, initially developed between 1938 and 1948 by Étienne de Gröer. Throughout this revision process, the office was responsible for urbanization plans for various areas of the city, addressing existing urban fabric and defining new morphologies for expansion zones. By the 1950s, urban life had outgrown a dictatorship’s restrictive representational framework. The GEU/CML’s activities represented a period of experimentation with a new concept of city. Beyond addressing structural issues such as the housing deficit and infrastructural challenges like the circulation system, urban spaces needed to reflect a new societal vision within the international political framework of democratic reconstruction following the end of World War II (WWII).

The late 1940s marked “a time when new city concepts began to emerge” [3], influenced by diverse approaches to urban planning and design. This shift was supported by the establishment of the General Directorate of Urbanization Services of the Ministry of Public Works (DGSU/MOP) in 1945 and the participation of its technicians in study trips, whose outcomes were partially documented in the DGSU Bulletins. In this context, the creation of the GEU/CML addressed “the need to revise and update the 1948 Master Plan, indispensable for its definitive approval” [4]. The explicit “need for updating” reflects a strategy to align with international architectural and urban debates, acknowledging the obsolescence of urban principles rooted in a plan designed to affirm the image of a fascist regime. Furthermore, it was stated that “although the Office’s primary purpose was to outline the major lines of the city’s urbanization”, it also influenced studies of specific zones and coordinated urban management.

Travel reports published in the DGSU Bulletins between 1946 and 1973, particularly during the GEU/CML’s operational period (1954–1959), referenced urban planning and design in England, the Netherlands, and France, among other recurring examples. The 1959 Lisbon Master Plan [5] reflects efforts to align with the international context, drawing on influences such as the English urban planning framework of the 1940s (Town and Country Planning Act), which promoted the creation of New Towns after WWII. These connections can be traced through the network of contacts between MOP and GEU/CML technicians and international representatives, exemplified by the relationship between chief engineer Luís Guimarães Lobato (GEU/CML) and architect Patrick Abercrombie (one of the authors of the London County Plan).

Along with new territorial management and urban planning principles, local urban studies introduced innovative urban designs influenced by ideas circulating in Modern Movement urbanism, such as freestanding blocks of collective housing and large green spaces. Following WWII, a new generation of architects sought to create a unique architectural and urban expression [6,7]. Held in 1948, the First National Architecture Congress was structured around the themes of housing and the city, summarizing a culturally vibrant moment whose impact would resonate in proposals and realizations throughout the following decade.

The urban morphology proposed by the GEU/CML architects is undoubtedly indebted to the urban principles advocated by the Modern Movement. Analyzing these proposals reveals a sensitivity to historical, artistic, and cultural memory, in contrast to the “tabula rasa” planning approach often criticized in the 1960s for discrediting post-war urban projects.

3.1.1. The Lisbon Master Plan (PDUL) of 1959

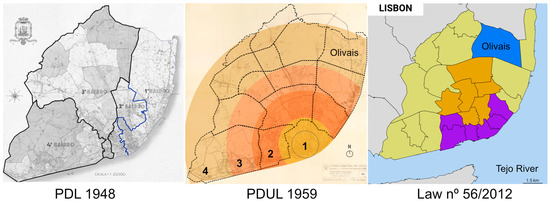

The 1948 Master Plan (PDL of 1948) divided Lisbon into four (4) administrative districts, whereas the 1959 Lisbon Master Plan (PDUL of 1959) proposed managing the territory through four zones: Center, First Residential Zone (consolidated urbanization), Second Residential Zone (urbanization in progress to be consolidated), and Third Residential Zone (to be urbanized), with the latter being the Peripheral Zone. The designation of four (4) districts as administrative areas within the City of Lisbon, totaling 53 parishes, remained in the Master Plan text until the administrative reform of 2012 (Law No. 56/2012, of November 8). This reform created five (5) territorial intervention units (UITs), which reorganized a total of 24 parishes into administrative areas (Figure 1). While the Center Zone in the 1959 Plan corresponded to the area of consolidated and historic urbanization [n. 1 in Figure 1], the new administrative organization [from 2012] moved the Center Zone to the geographic center of the urban territory [orange color in Figure 1], distinguishing it from the Historic Center Zone [purple color in Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Representation of the administrative organization of the City of Lisbon at three different times: PDL from 1948 (4 districts), PDUL from 1959 (15 grids and residential zones 1, 2, 3 and 4), and Law no. 56 of 2012 (24 Parishes). Assembled by Carolina Chaves (2024).

The Lisbon Master Plan from 1959 (PDUL from 1959) defined four zones divided into fifteen grids based on spatial and social characteristics and the stage of the urbanization process. These grids would then be divided into urban units and cells, with the latter serving as the smallest unit and being equivalent to the concept of the neighborhood unit (NU). By addressing different urban scales, these NUs were designed with collective facilities sized according to the corresponding population contingent. The location of these facilities aimed to maintain distances of 300 to 500 m between primary schools, local commerce, and residential blocks (at the cell scale)—a concept applied in the urbanization of Alvalade (1947–1954), in which engineer Luís Guimarães Lobato was involved and who was a key figure in coordinating the GEU/CML.

The 1959 Plan outlined guidelines for the city’s urbanization and population distribution based on its zones, defined by characteristics resulting from the application of four structuring elements specified by the Master Plan: gross occupancy index, population density (gross and net), built area, and free space per inhabitant. The application of these elements should take into account each zone’s dynamics and unique characteristics.

“(…) with a certain understanding of the availability of residential areas within the grids, it is almost never appropriate to assume a uniform density per grid. Even in an initial approximation, the structure, characteristics, and social category present in each zone, as well as other factors, must be considered when determining the density values to be used.”[5] (v. 4, p. 8)

Within this framework, three types of residential zones were defined, each with an acceptable level of intervention, indicating that the city’s urban development practice would not correspond to a ’tabula rasa’ approach. Thus, there would be stabilized zones or established zones, new expansion zones of the city, and zones allowing for reconstruction and remodeling.

Stabilized zones or established zones are older areas of occupation that must take into account factors such as age, structure, saturation level, and aesthetic value. An example is Alfama, classified as a stabilized zone due to its “aesthetic and artistic value, which corresponds, in its characteristics, to a heritage the city must preserve” [5] (v. 4, p.9). Also, Alvalade was to have its characteristics preserved not due to aesthetic or artistic recognition but because of the recent completion of such a significant project that any adjustment would be unjustified.

The city’s new expansion zones included new areas that could be urbanized without significant constraints. Their characteristics would be determined subsequently through urbanization plans (baseline studies and partial plans), respecting the population limit of the grid to which these zones belong, as exemplified by Benfica and Olivais. The remodeling and reconstruction zones could be restructured. However, extensive remodeling or reconstruction actions implying a fundamental reorganization of the zone’s urban structure would be exceptions.

“From an urbanistic perspective, and in areas already exhibiting an urban character, the block or area with similar features or importance should be considered the final unit of cohesion.Its characterization at the scale of the Partial Plan should, therefore, be expressed by considering the physiognomy and topography of these areas, their subdivision, their valuation, the significance of the streets that delineate them, the renewal of any existing constructions, and any other relevant informational aspects that may prove useful.”[5] (v..4, p. 5)

According to what has been presented, housing was the central and structuring theme around which the city’s development was planned in response to a changing environment that was moving toward the strengthening of democracies (at least on the international stage). The urban form is aligned with these ideals by strengthening urban spaces for collective use (green spaces and collective facilities). One of the fundamental principles of this new urban structure was population distribution, which reshaped the occupation of the central area while encouraging the occupation of other residential zones. After considering the Lisbon Master Plan (1948) proposal and the 1950 Census, the Lisbon Master Plan (1959) proposed the following population distribution (Table 1).

Table 1.

Resident population in Lisbon in absolute numbers, as recorded in the 1940 and 1950 Censuses, projected by the Master Plan (1948) and the Lisbon Master Plan (1959). Source: data from the Lisbon Master Plan (1959).

The new plan reduced population density in the Central Zone while predicting a population movement to the peripheral zone, which population would increase by an exogenous movement. Compared to the density projected in 1948, the new Master Plan predicted a higher density for the First Residential Zone as a result of the area’s urban renewal process. The density projected for the Second Residential Zone was slightly lower. In the Third Residential Zone (the periphery), densities would be “compatible with an open-scheme urbanization, sparse but to completely define the entire area” [5] (v. 1, p. 18), at around one thousand people per square kilometer.

Coordination between urban planning in Lisbon and regional planning was an established premise, conditioning a balanced distribution of the population not only within the municipal boundaries of Lisbon but also considering the regional scale, so that “it would continue to integrate into a whole that included the bordering areas subject to its general and more direct influence, constituting a region that came to be known as Greater Lisbon.” [5] (v. 1, p. 3).

“(…) The plan emphasized the need to avoid excessive urban concentration by limiting its expansion. This would be achieved through an appropriate redistribution of surplus populations to regional urban centers, ensuring that at no point would the necessary coordination be lost. The goal was for the region, integrating the city, to form a cohesive unit of social interest in its broadest moral, cultural, and political sense, as well as economic interest, contributing in an orderly manner to the nation’s development.[5] (v. 1, pp. 4–5)

(…)

To this end, detailed studies were conducted for all areas of the city to assign urbanization characteristics that determined admissible construction volumes aligned with the population distribution planned for Lisbon. The criteria prioritized improving housing conditions in older, overcrowded areas and planning new, well-organized urban units equipped with necessary facilities. These included free spaces, school complexes, secondary schools, markets, and other essential amenities.”[5] (v. 1, p. 6)

The firm stance of controlling and distributing the population across the urban territory had a direct and regulatory impact on private initiatives and real estate speculation. This is demonstrated by the principle that “the construction or reconstruction of private initiative can no longer be guided solely by maximizing the profit from the individual lot, but must be conditioned by the ‘reasons of the zone’ to which it belongs (…)” ([5], Fol. 1053). This framework aligned with the policies of land expropriation and acquisition implemented by Duarte Pacheco (1900–1943), which were essential for the eastern urbanization of Lisbon. The attempt by public authorities to control real estate speculation was, according to Lobato, one of the factors contributing to the discontinuation of the GEU/CML and the approval of the 1959 PDUL (Lobato 2004), as it clashed with the interests of private real estate groups.

3.1.2. Local Urbanization Plans

Urban design varied according to the level of urbanization in the area. In general, efforts were made to promote the creation of green spaces to bring residents closer to nature. This discourse was aligned with the garden city culture, but it was proposed under a design approach closer to a “vertical garden city” rather than a “horizontal garden city.” Undoubtedly, the peripheral zones offered the best conditions for this new design, although it is worth emphasizing that this directive was not confined to those areas. Reconnecting humanity and nature through the establishment of a new relationship between city and countryside—where the latter was integrated into and inseparable from the structure of the former—was not limited to spaces between blocks, parks, or gardens but was also present in the road infrastructure.

In 1956, engineers Luís Guimarães Lobato and João Rebelo Raposo, representing the GEU/CML, presented “The ‘Control’ of Urban Expansion” at the XXIII International Congress of Urbanism and Housing. The theme was “The City and its Suburb.” In the referenced document:

“It is, therefore, essential that cities, particularly the large ones, develop within the framework of a regional planning strategy to ensure that the population is settled in satellite nuclei within the region, especially when national measures fail to achieve the desired reduction in population influx to urban centers.It is evident that the regional distribution of the population drawn to a major urban center should encourage their settlement in self-sustaining satellite nuclei, rather than transforming them into mere dormitories of the larger city.”[8] (p. 5)

At the urban planning scale, it was also envisioned, whenever possible, that new urban units would achieve autonomy and self-sufficiency, reducing their dependence on the central core. From this perspective, regarding these new urban areas,

“(…) not all have achieved independent livelihoods and still function as dormitory communities. However, it is expected that these dormitories will evolve into self-sustaining nuclei through the implementation of appropriate economic and social measures capable of fostering local settlement among their residents.The population of Lisbon continues to grow, albeit at a slower pace. Plans are underway for the city’s expansion, including the creation of new urban units designed, as much as possible, to sustain autonomous living.The initial focus has been on deconcentrating the population from Lisbon’s central core. This is now being followed by decentralization measures aimed at alleviating the pressure on the central area, facilitating its redevelopment, and enabling the establishment of new, independent expansion nuclei. Nevertheless, this is a long-term endeavor requiring persistence, and one that the Municipality of Lisbon has been undertaking for approximately ten years.”[8] (p. 5)

Within the framework of urban planning for the city of Lisbon, driven by new criteria for urban quality of life, it was anticipated that:

“In residential areas, the types of housing and the need for open spaces primarily define the planning direction, appropriately correlated with population density. The land occupancy rate and obstruction angle generally derive from the three mentioned characteristics [population density, covered area per inhabitant, and open space per inhabitant] and function as final instruments of control over urban expansion.”[8] (p. 8)

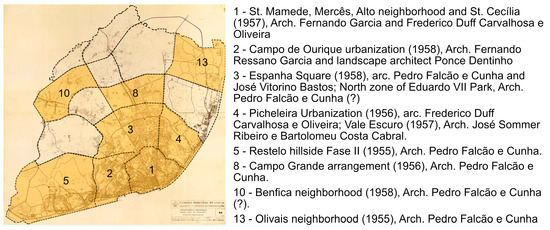

The 1959 PDUL reports the development of 169 urbanization plans, of which only a small sample was identified in the Historical Archive of the Lisbon City Council (CML) (Figure 2). This sample comprises a sufficiently diverse set to provide insight into the actions envisioned by the GEU/CML for the three types of residential zones outlined in the plan. These proposals reflect varying approaches to intervention depending on the stage of urbanization and the specific characteristics of each targeted zone, preserving consolidated urban fabrics while exploring new urban morphologies in peripheral areas.

Figure 2.

Grids location and local urbanization plans by GEU/CML (1954–1959). Adapted from PDUL 1959.

To conduct these various studies, the technical staff were organized into teams. Analysis of the documents reveals the recurring involvement of architect Falcão e Cunha in expansion areas (Encosta do Restelo II Phase, Olivais, Campo Grande, and Praça de Espanha). This observation suggests a hypothesis regarding his involvement in studies for Parque Eduardo VII and Benfica (categorized as expansion studies whose authorship was not identified in the documents reviewed). Other studies, concentrated in areas closer to the central zone, were attributed to architects Fernando Ressano Garcia (Campo de Ourique and São Mamede), Fernando Duff Carvalhosa (São Mamede and Picheleira), and José Sommer Ribeiro (Vale Escuro). The latter also collaborated with architect Falcão e Cunha in redevelopment studies for expansion areas such as Restelo II Phase and Olivais (South), where he was responsible for subsequent adjustments to the base study.

Of the studies conducted by the GEU/CML, the current literature highlights those for Olivais (Grid 13) [9,10,11,12] and Encosta do Restelo II Phase (Grid 05) [13]. Both are in urban expansion areas and involved architect Pedro Falcão e Cunha, with later contributions from architect José Sommer Ribeiro. Within this scope, certain grids were in stabilized residential zones (“Grid 1–Centro” was clearly a zone with consolidated urban units, with limited remodeling or reconstruction activities). Others, being in the process of urbanization, included cells classified as consolidated zones alongside zones marked for remodeling or reconstruction (“Grid 3–São Sebastião”, for instance, included consolidated units such as Campo de Ourique while also featuring urban units requiring remodeling, such as the area north of Parque Eduardo VII). Grids situated on the outermost ring near the city limits, still rural in nature, were categorized as expansion zones where greater freedom existed to define new urban designs while adhering to established urban planning indices (“Grid 10–Benfica, Carnide” and “Grid 13–Olivais” are examples from the studies identified in the archive).

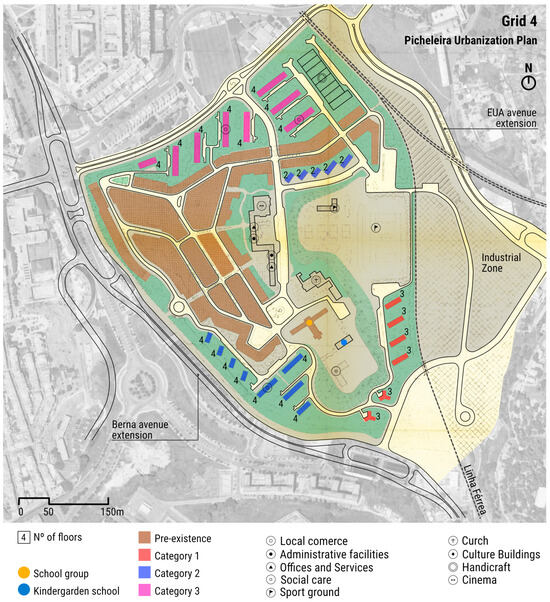

A recurring approach in the analyzed studies, even in residential expansion zones, was the retention—albeit to varying degrees depending on the zone—of pre-existing elements within the urban framework. This retention extended beyond “national monuments” and hinted at an expanded notion of heritage. For example, the recognition of the cultural value of the houses in Campo de Ourique, whose preservation was deemed essential to maintaining the identity of the urban ensemble, reflects this perspective. Similarly, the urbanization of Picheleira (Figure 3) retained the nucleus of the initial settlement, around which a new urban arrangement was proposed. This arrangement incorporated independent blocks interspersed with green spaces and new facilities designed to enhance collective life.

Figure 3.

Picheleira Urbanization Plan (1956), GEU/CML. Architect Frederico Duff Carvalhosa. Assembled by Carolina Chaves (2024).

Even in peripheral urban areas such as Benfica and Olivais, there was a recognition of an “old” nucleus that would be preserved in the urbanization plans for those areas. In the Olivais Grid, the “Olivais Velho” nucleus was identified. In Benfica, the housing along the Estrada de Benfica was retained, as well as the developments to the east and west of Parque Silva Porto. This included the Bairro de Casas Económicas de Santa Cruz, designed by architects Francisco Keil do Amaral and João Filipe Vaz Martins (1910–1988) and built in the 1950s.

3.2. Olivais Norte e Sul (1954–1959)

Since these neighborhoods were the only proposals effectively built—particularly the urbanization of Olivais Norte—the changes implemented throughout the design process of these areas reflect the forces resisting the planning proposed in the 1959 PDUL and the urban design associated with the Modern Movement.

In 1964, Leopoldo Almeida’s critical note [14] highlights, on the one hand, the links between the urban morphology of Olivais Norte and the ideas outlined in the Athens Charter and, on the other hand, the new directions proposed by the revised plan for Olivais Sul. However, it is important to note that this distinction is possible because Almeida’s analysis refers to the results of successive adjustments made until 1964 and not to the baseline study proposed by GEU/CML and approved in 1955.

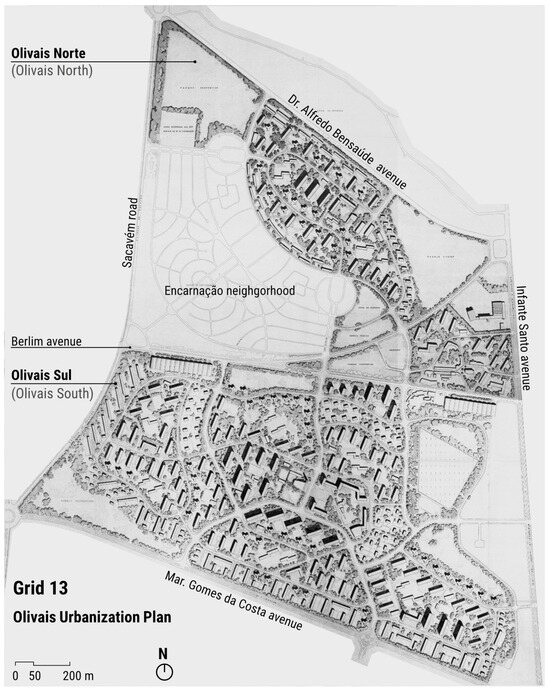

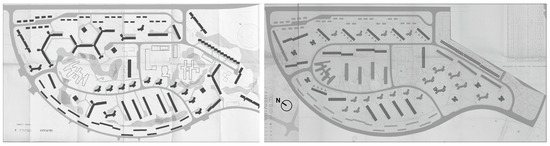

In that study, Olivais Norte and Olivais Sul were conceived as parts of the same urban design (Figure 4), governed by the principle of independence between blocks to maximize natural lighting and ventilation while allowing for the definition of green open spaces as connective tissue and the hierarchy of circulation infrastructures to protect pedestrians from motorized traffic. This model would later be questioned both at the level of urban design and in the policies for the distribution and occupation of urban land.

Figure 4.

Olivais Grid urbanization plan [Olivais Norte e Sul], 03-19-1955. Architects Pedro Falcão e Cunha e José Sommer Ribeiro. Adapted by Carolina Chaves (2024) from primary documentation at the archive AML—PURB/002/05193 e DGPC/Des. 10127.

Regarding the urban design, the proposed plan for Olivais Norte and Olivais Sul was challenged by the teams of architects invited to design the residential buildings. Among the proposals submitted between March 1958 and November 1959 (Figure 5) was one by architects Manuel Tainha and Gomes da Silva, which altered part of the road layout proposed by the GEU/CML and suggested megastructures as a housing typology, replacing the slab block.

Figure 5.

New urban proposals for Olivais Norte with distinct building disposition (blocks in black). Adapted by Carolina Chaves (2025) from primary documentation at the archive DGPC/SIPA/PT NTP DES.08131 [left] and AML—PURB/002/05193 [right].

The following proposals reveal a negotiation process between the GEU/CML, represented by architect Pedro Falcão e Cunha, and the invited teams, culminating in a synthesis design finalized in November 1959 and jointly signed (Figure 5). This final proposal is, in fact, the constructed plan and the subject of analysis in the studies published to date.

The tension between GEU/CML teams of architects and technicians’ vision of the city and, more broadly, the concept of dwelling, was expressed in the decision to withdraw by the external teams, who claimed that they no longer recognized the freedom they had initially considered possible by accepting the invitation to develop the housing projects. Thus,

“It is with regret that we withdraw from this part of the work that we had been entrusted with, especially since we believe it is essential for the authors of the building designs to be called upon for an active role in the development of the master plans; for this very reason, we had rejoiced in the attitude of the Municipal Services when the invitation was made to the teams.”[15] (p. 2)

The housing projects designed for Olivais Norte would be implemented in the urbanization of Olivais Sul. However, the recorded adjustment was made in 1959 by architect José Sommer Ribeiro (one of the base study’s architects), which can be attributed by the difficult cooperative relationship experienced in Olivais Norte. The actual adjustment of the Olivais Sul plan, guided by the new Decree-Law 42.454 (08/18/1959), would only occur at the dawn of the 1960s within the framework of the GTH/CML’s activities. In this new technical and administrative structure, the contribution of the teams of architects invited to intervene in the plan was crucial in defining the urban morphology of Olivais Sul—a result of a generation guided by a renewed theoretical foundation, which was somewhat indifferent (or uninterested) in recognizing the contributions of urban planning and design from the 1950s.

In addition to the context of opposition to the architectural and urban planning principles that characterized the plan for Olivais Norte and Sul in the 1950s, divergent interests concerning the distribution and occupation of urban land were also at play. The correspondence exchange between the President of the Council and the Ministry of Corporations and Social Welfare—documents consulted in the Oliveira Salazar archive (reference PT/TT/AOS/Cx. 69/No. 04) regarding the “Housing Problem in Portugal” (1959)—reveals the difficulty of dialogue between the Ministry and the vice-presidency of the CML, represented by engineer Luís Guimarães Lobato, regarding the distribution of land in Restelo and Olivais for housing construction amid discussions on the vote for low-rent housing legislation. In this same correspondence (from July 1959), the Ministry representative stated that they had learned about the preparation of new legislation [DL 42.454] aimed at promoting affordable housing, regarding which they expressed reservations and amendments to the draft text. The revision of the percentages for the distribution of housing categories can thus be summarized as follows (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of the distribution of housing categories in PDUL 1959, GEU/CML proposal on 07/11/1959, and Decree-law 42.454 on 08/18/1959. Elaborated by Carolina Chaves (2023).

The aforementioned episode depicts, albeit in a specific case, the dispute over urban land. The new legislation legitimized and established the obligation to provide housing with affordable rents to accommodate all social classes (four income levels) in order to ensure a heterogeneous social fabric, as outlined in the 1959 PDUL text and implemented in the GEU/CML’s local urbanization plans. At the government level, a Housing Commission would be created under the Presidency of the Council, in which the vice president of the CML (among other representatives) would participate. At the municipal level, the text authorized the creation, “on an occasional basis”, of a technical service linked to the Presidency—under the same terms as the establishment of the GEU/CML.

3.3. Decree-Law 42.454, 08/18/1959

Decree-Law No. 42,454, enacted in August 1959, was a pivotal element in the housing policy implemented in the city of Lisbon. It is understood that, initially, the new law was not intended to abolish the GEU/CML. On the contrary, its text validated key aspects of the 1959 Plan’s promotion of housing and urban land occupation. This can be observed through the proposal for the creation of the Gabinete de Estudos de Urbanização e Habitação (GEUH/CML), which preserved the structure and work already done while aiming for its expansion. Furthermore, the reports prepared by GEU/CML to meet the requirements of the new law demonstrate a commitment to continuity in the urban studies conducted.

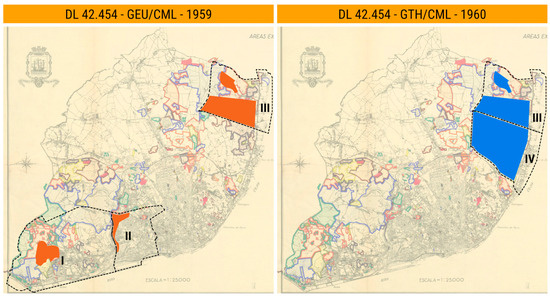

In this context, the GEU/CML technicians assessed that it would be possible to meet the goals set in 1959 through the urbanization of Encosta do Restelo II Phase, Casal Ventoso, and Olivais (Figure 6). This analysis was further strengthened by the fact that the CML owned a large portion of the land for urbanization. From this perspective, in October and November 1959, the adjustment plans for Encosta do Restelo II Phase and Olivais Sul were developed, both assigned to architect José Sommer Ribeiro. However, it is worth noting that the value of land in the Restelo area was increasing, making it less suitable for the construction of social housing.

Figure 6.

Areas of intervention for housing development under Decree-Law 42.454 of 08/18/1959 superimposed on the Plan of Areas Expropriated or Acquired by CML between 1938 and 1945. The different colors of line represent the land owned by the municipality by 1945 and the colored areas represent the intervention areas proposed by GEU (1959) and GTH (1960). Restelo (I), Casal Ventoso (II), Olivais (III), and Chelas (IV). Adapted by Carolina Chaves from primary documentation at the archive AML—PURB/002/03926.

The PDUL was presented to CML and received municipal approval in December 1959, while Colonel Álvaro Salvação Barreto (1890–1975) was still president and engineer Guimarães Lobato was the second vice president. However, the process did not achieve the same outcome at the government level. The dawn of the 1960s was marked by administrative changes in the CML, with the appointment of the new president, Colonel França Borges (1901–1986), the dissolution of the GEU/CML, and the creation of the GTH/CML. The new office was placed under the technical coordination of engineer Jorge Carvalho de Mesquita, who had worked in the GEU/CML between January 1954 and April 1956. The creation text for the GTH/CML outlined the task of constructing 23,000 new dwellings, specifying their locations in Olivais Norte (1900 dwellings), Olivais Sul (8200 dwellings), Chelas (12,000 dwellings), and Montes Claros (900 dwellings), with the aim of concentrating the construction of new housing in the eastern part of the city (Figure 6). It is important to note that a significant portion of the land in Chelas did not belong to the CML, meaning that expropriation or acquisition of the land would be necessary.

4. Conclusions

Contradicting the current criticism of the Modern Movement, this research proved that the theoretical principles of the Modern Movement informed an urban planning policy and urban form engaged with social and economic balance, a healthy green city, and the city’s cultural heritage. Even considering that this research focused on a specific experience, it paves the way for new revisions pointing out the key role of the architecture and urban archives.

The goal of shedding light on the urban planning process developed between 1954 and 1959, as well as its dereliction, is to recall the conflicting interests involved in the city-making process, particularly in the political, economic, and cultural realms. Moreover, reviewing the proposals presented by the GEU/CML reveals a vision of Lisbon that could have been realized, highlighting the importance of collective green spaces and the provision of housing for a population of one million inhabitants. This vision was rooted in public governance actions designed to prevent socio-spatial segregation while enhancing systems of mobility—collective, automotive, and pedestrian.

The current housing crisis in Lisbon demands a nuanced understanding of its urban history, plans, and housing policies to inform the development of new perspectives. The Lisbon urban planning policy from the 1950s shows that it would be possible to provide housing and a green city for a population twice the current one if the government managed to rebalance the public and private interests and land property. It will require boldness to devise a coordinated approach that is socially, culturally, and environmentally committed to sustainable urban and human development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C.; Methodology, C.C.; Investigation, C.C.; Data curation, C.C.; Writing—original draft, C.C.; Supervision, A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Foundation for Science and Technology (Portuguese: Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia—FCT), the European Social Fund (ESF), and the European Union (EU) through a PhD Grant (2020.05276.B.D.). This research also falls within the project 10.54499/UIDB/05703/2020 from the CiTUA research unit (Center for Innovation in Territory, Architecture and Urbanism).

Data Availability Statement

This article was primarily submitted to and presented in the 5ª International Congress on Housing in the Lusophone Space (5º CIHEL) as part of the doctoral thesis “Olivais Norte e Sul: outcome and testimony of a Lisbon under transformation 1954–1964” conducted by Carolina Chaves under the supervision of the PhD Professor Ana Tostões (IST-ULisbon, Portugal) and PhD Professor Carlos Martins (IAUUSP-São Carlos, Brazil) in the Instituto Superior Técnico of Lisbon University (IST-ULisboa). The thesis is available at https://scholar.tecnico.ulisboa.pt/records/7u_K9Uqn8JSbcRKrVc9ZSEgHQFYr8kCQb5bg (accessed on 27 January 2025).

Acknowledgments

This research also received the support of the Federal University of Sergipe (Brazil) where the first author, Carolina Chaves, works as an associate professor and is head of the Department of Architecture and Urbanism. In addition, it is relevant to stress the collaboration of all public archives in Lisbon throughout the doctoral research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CML | Câmara Municipal de Lisboa (Lisbon City Council) |

| DGSU/MOP | Direção Geral de Serviços de Urbanização (General Directorate of Urbanization Services of the Ministry of Public Works) |

| GEU | Gabinete de Estudo de Urbanização (Urban Studies Office) |

| GTH | Gabinete Técnico de Habitação (Techinical Housing Office) |

| NU | Neighborhood Unit |

| PDUL | Plano Director de Urbanização de Lisboa (1959 Lisbon Master Plan) |

| WWII | World War II |

References

- Anastácio, M.; Marat-Mendes, T. Habitat|Habitação: A reconstituição de um paradigma (Lisboa, 1950–1970). In PNUM 2018: A Produção do Território: Formas, Processos, Desígnios; Repository Aberto da Universidade do Porto: Porto, Portugal, 2018; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tostões, A. Lisboa Moderna; Ideias, Docomomo Internacional Lisboa e Circo de Ideias: Porto, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lôbo, M.S. Planos de Urbanização: A Época de Duarte Pacheco; FAUP: Porto, Portugal, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lisboa, C.M.L. Anais do Município de Lisboa 1954; Hemeroteca Digital de Lisboa: Lisboa, Portugal, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- GEU-CML, Plano Director de Urbanização de Lisboa [PDUL 1959]; CML: Lisboa, Portugal, 1959.

- Portas, N. A Evolução da Arquitectura Moderna em Portugal. In História da Arquitectura Moderna; Zevi, B., Ed.; Editora Arcádia: Lisboa, Portugal, 1973; Volume II, pp. 688–744. [Google Scholar]

- Tostões, A. A Idade Maior, Cultura e Tecnologia na Arquitectura Moderna Portuguesa; FAUP Publicações: Porto, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lobato, L.G.; Raposo, J.R. O ‘Contrôle’ da Expansão das Cidades; CML: Lisboa, Portugal, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, T. As Vicissitudes do Espaço Urbano Moderno ou o Menino e a Água do Banho. Os Bairros dos Olivais. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculdade de Arquitetura da Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, I. Arte e Habitação em Lisboa 1945–1965. Cruzamento Entre Desenho Urbano, Arquitetura e arte Pública. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat de Barcelona, Barcelona, Portugal, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lourenço, A.C. Olivais e Telheiras: Marcos do Movimento Moderno na Expansão Planeada de Lisboa. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Superior de Ciência do Trabalho e do Emprego (ICSTE), Lisboa, Portugal, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, T. Bairros Planeados e Novos Modos de Vida. Olivais e Telheiras: Que Contribuições para o Desenho do Habitar Sustentável? Caleidoscópio: Lisboa, Portugal, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- D’Almeida, P.B. Bairros do Restelo: Panorama Urbanístico e Arquitectónico; Caleidoscópio: Lisboa, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida, L. Nota Crítica. Rev. Arquit. 1964, 81, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Reajustamento do Estudo-Base dos Olivais—Célula A; Gabinete de Estudos de Urbanização (GEU/CML): Lisboa, Portugal, 8 August 1958.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).