Landscape Design and Sustainable Tourism at the Wuyistar Chinese Tea Garden, a World Heritage Site in Fujian, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Research Method and Process

2.3. Superior Planning and Land Use Adaptability Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Existing Natural Resource Survey Results

3.1.1. Topography and Slope Survey Results

3.1.2. Current Natural Resources Survey Results

3.2. Planning Concepts and Characteristics

3.2.1. Restoring Mountains and Rivers

3.2.2. Rereading Cultural Context

3.2.3. Sorting out Style and Appearance

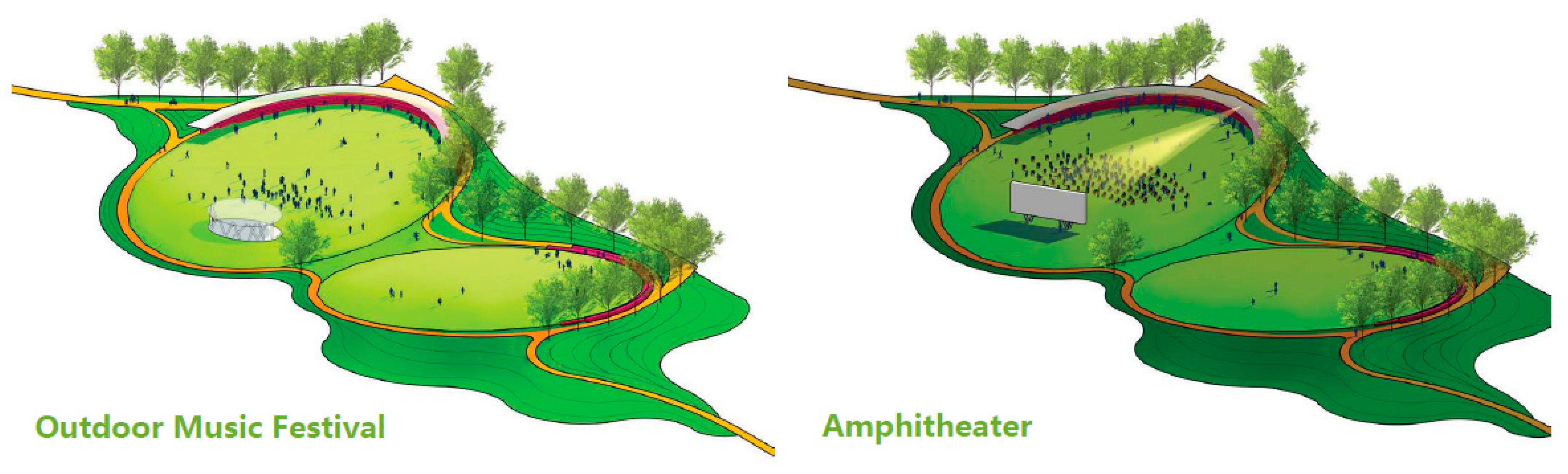

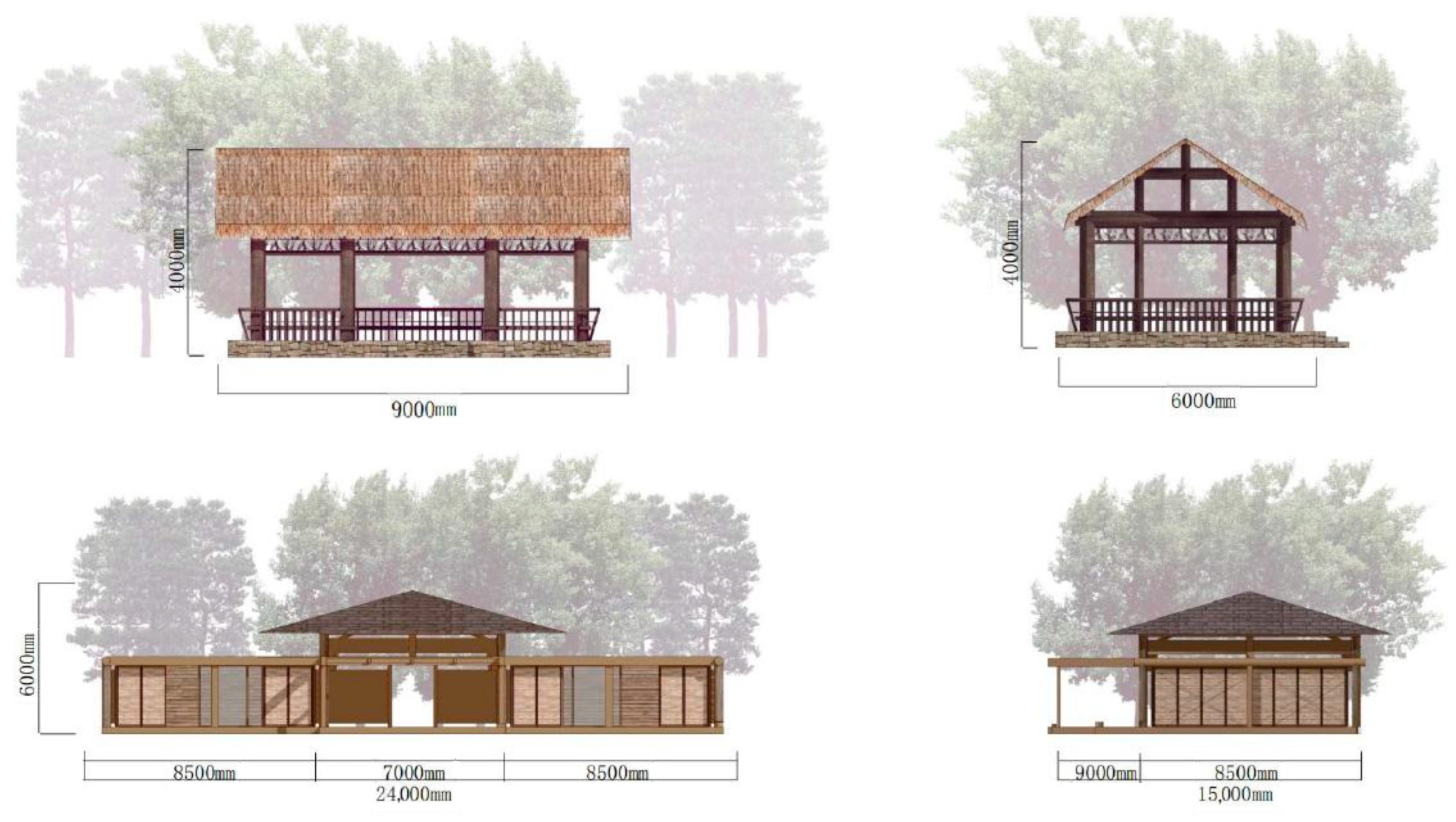

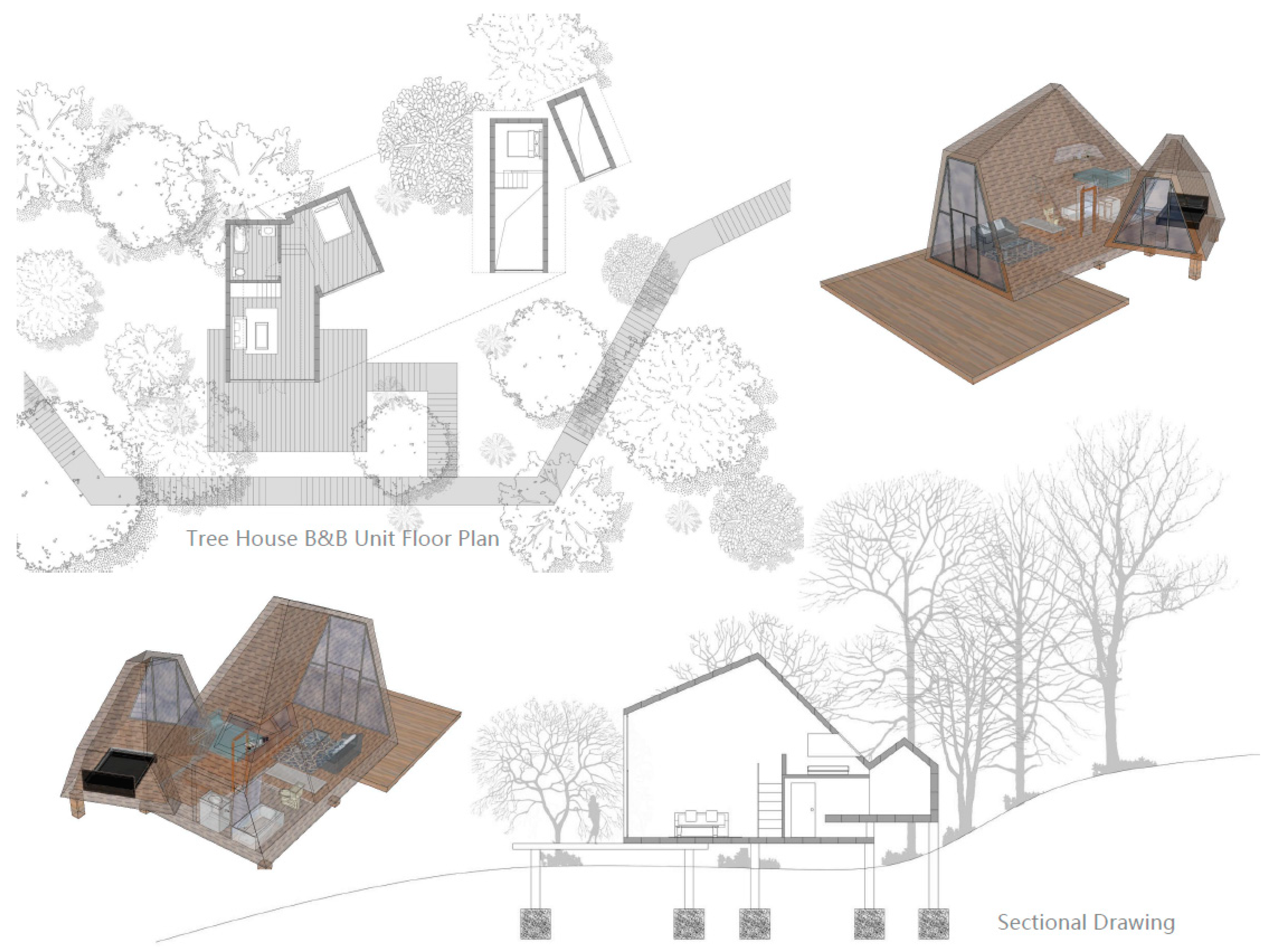

3.2.4. Improving Functions

4. Discussion

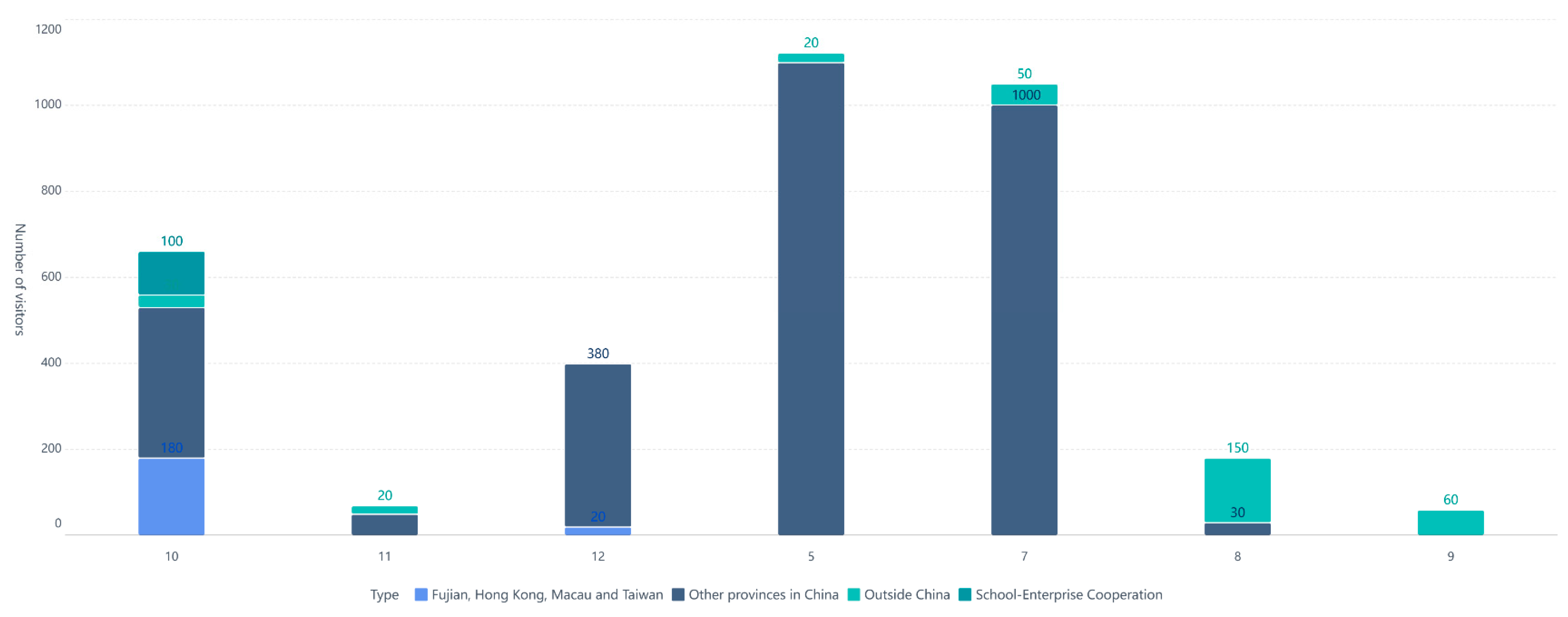

4.1. Phased Construction and Sustainable Development

4.2. Planning Principles Followed in Development

4.3. Benefits After Construction and Challenges

4.4. Comparison with Other Tea Gardens

4.5. Management of Tea Garden: Balancing Conservation Policy and Development

4.6. Relationship with Global Frameworks

5. Conclusions

5.1. Research Findings

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- You, W.; He, D.; Hong, W.; Liu, C.; Wu, L.Y.; Ji, Z.R.; Xiao, S.H. Local people’s perceptions of participating in conservation in a heritage site: A case study of the Wuyishan Scenery District cultural and natural heritage site in Southeastern China. Nat. Resour. Forum 2014, 38, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount Wuyi. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/911/ (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Zhao, P.; Zhang, L.; Tian, R.G. Tourism attraction and tourist satisfaction with world heritage: A case study of Mount Wuyi. J. Mark. Dev. Compet. 2018, 12. Available online: https://articlearchives.co/index.php/JMDC/article/view/4485 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Zhou, Y. Discussion on the Development, Appreciation and Dissemination of Oolong Tea. Agric. For. Econ. Manag. 2023, 6, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ecological Tea Garden. Available online: http://www.wuyistar-tea.com/brand/resource (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Xu, J. Tea Tourism Development in China Entering Experience Economy Era Under the Strategic Background of Rural Revitalization: A Case Study of West Lake Longjing Tea Area and Damushan Tea Garden Area in Zhejiang Province. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat de les Illes Balears, Palma, Spain, 2022. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11201/159249 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Cheng, S.; Hu, J.; Fox, D.; Zhang, Y. Tea tourism development in Xinyang, China: Stakeholders’ view. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 2, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Yang, L.; Liu, M.; Pei, P. Soil Characteristics and Nutrients in Different Tea Garden Types in Fujian Province, China. J. Resour. Ecol. 2014, 5, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Driem, G. Tending the Tea Garden. The Tale of Tea. Brill 2020, 835–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, W. Analysis on the development of sightseeing ecological tea gardens in Pingxiang City. Mod. Hortic. 2021, 44, 139–140. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Chen, J. Research on architectural design of leisure and sightseeing tea gardens. Fujian Tea 2024, 46, 76–78. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cai, C.; Fen, S. Research on the relationship between tea garden sightseeing image, tourism experience and behavioral intention. Tea Newsl. 2024, 1–8. (In Chinese). Available online: http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/43.1106.S.20240326.1645.044.html (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Li, L. Plant pattern Innovative practice in sightseeing tea garden: A trio of space, technology and nature. Mol. Plant Breed. 2024, 22, 967–972. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z. Analysis of non-tea plant configuration and layout in ecological sightseeing tea garden. Mol. Plant Breed. 2024, 22, 1679–1685. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Z. Integration of art form and landscape in tea garden landscape design. Fujian Tea 2022, 44, 77–79. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Tian, X. Thoughts on the landscape design of sightseeing tea gardens with tea culture as the theme. Fujian Tea 2023, 45, 75–77. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, T.; Wang, S. On the application and expression of tea culture in the landscape design of sightseeing tea gardens. Fujian Tea 2021, 43, 88–89. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. Exploring the application and expression of tea culture in the landscape design of sightseeing tea gardens. Fujian Tea 2020, 42, 90–91. (In Chinese). Available online: https://chn.oversea.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2020&filename=FJCA202009060&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=31yzcAcT61Mnq4DfdLCm8BAqak-kmKVvmJPoL-gyDggT43DNThbzcEOcm08E2u0- (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Huang, M. An analysis of the application and expression of tea culture in the landscape design of sightseeing tea gardens. Fujian Tea 2020, 42, 91–92. (In Chinese). Available online: https://chn.oversea.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2020&filename=FJCA202007061&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=31yzcAcT61PzHCBx_VbKvSKsMd5GHzdlsISstE79UCRkzEqkc74hbdVjLbHObGmX (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Luo, L. Research on the application of digital art project of 4D holographic projection in creating cultural landscape of Jiqingli Tea Garden. AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 2685, 030034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, F.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ding, Z. Construction of landscape ecological tea garden based on homeostasis theory: A case study of Wuyishan National Forest Park. In Frontiers in Civil and Hydraulic Engineering; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; Volume 1, pp. 492–496. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder, S.A.; Saha, K.; Haque, M. An Interpretive Analysis on the Heritage Values and Morphology of Tea Cultural Landscape: A Case Study on Khakiachara Tea Estate, Sreemangal, Bangladesh. A+ Arch. Des. Int. J. Archit. Des. 2021, 7, 125–137. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Zheng, S. Design of a Tea Garden Antifreezing Control System. In Proceedings of the 2016 6th International Conference on Machinery, Materials, Environment, Biotechnology and Computer, Tianjin, China, 11–12 June 2016; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 736–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Qi, X.; Lin, S.; Liu, C.; Jin, Z.; Wang, Y. Design and experiment of electric remote control tea garden management machine. J. Chin. Agric. Mech. 2024, 45, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naushad, N.M.; Hossain, S.; Rahman, M.F.; Sajoy SM, U.H.; Khan, M.R. Design and Analysis of Agrivoltaics on Tea Garden: A Case Study in Bangladesh. In Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference on Development in Renewable Energy Technology (ICDRET), Dhaka, Bangladesh, 7–9 March 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Focusing on the Whole-Region Ecological Tourism and Planning the Innovative Development of the Tourism Industry During the 13th Five-Year Plan Period—Interpretation of the “13th Five-Year Plan for the Development of Tourism Industry in Fujian Province”. Available online: http://wlt.fujian.gov.cn/zwgk/zcjdzl/szfzcwjjd/201912/t20191220_5165398.htm (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Nanping Tourism Industry Development Plan (2017–2025). Available online: https://np.gov.cn/cms/html/npszf/2018-08-21/477978659.html (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Lan, C.; Sun, J.; Zhao, B. Origin, History and Species of Tea. In Tea Polyphenols, Oxidative Stress and Health Effects; World Scientific Publishing Company: Singapore, 2023; Volume 2, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y. Terroir Exploration: A Case Study of Jingmai Mountain Tea Culture Tourism. 2023. Available online: http://dspace.unive.it/handle/10579/25646 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Xiao, K. The taste of tea: Material, embodied knowledge and environmental history in northern Fujian, China. J. Mater. Cult. 2017, 22, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBernardi, J. The modern invention of big red robe tea: History, science, story, and performance. In Understanding Authenticity in Chinese Cultural Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 186–201. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, E.; Jalonen, R.; Loo, J.; Boshier, D.; Gallo, L.; Cavers, S.; Bordács, S.; Smith, P.; Bozzano, M. Genetic considerations in ecosystem restoration using native tree species. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 333, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Z. Culture of “Crossing the Sea to the East”: The Cultural Bond Between China and South Korea that Has Lasted for 800 Years. Available online: http://www.news.cn/ci/20241018/6f78e3e960d94202a27434d2b7ad9856/c.html (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Experts Offer Guidance on Using the World Heritage Convention in Support of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/2748 (accessed on 13 March 2025).

| Type | Name | Time | Number of Visitors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fujian, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan | The establishment of the “Friends of Wuyi” in Macau and the 2023 Macau-Nanping Youth Exchange Activities | 28 October 2023 | 40+ |

| Fujian and Taiwan Artists Exchange Activities | 3 December 2023 | 20+ | |

| “Love Fujian, Tea Fragrance on Both Sides” Series of Activities | 24 October 2023 | 100+ | |

| Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau University Students Exchange Tea Culture | 28 October 2023 | 40+ | |

| Outside China | Mid-Autumn Festival Tea Party for International Students in China | 12 September 2024 | 40+ |

| Visit and exchange for the 23rd “Chinese Bridge” World University Chinese Competition | 18 August 2024 | 150+ | |

| Capacity building workshop for the Ministry of Women, Youth, Children and Family Affairs of the Solomon Islands | 31 May 2024 | 20+ | |

| “Discover the Beauty of China” experience tea culture for diplomats stationed in China | 1 November 2023 | 20+ | |

| Study tour of Busan branch of Korean Tea Association | 11 October 2023 | 30+ | |

| The Chief Minister of Penang, Malaysia, and his delegation visited | 1 September 2023 | 20+ | |

| The first “Youth Journey, Fujian Appointment”—2023 Overseas Youth Study Camp | 15 July 2023 | 50+ | |

| Other provinces in China | Tea culture study activities for students of Changle No. 2 Middle School and Changle No. 6 Middle School in Fujian Province | 8 July 2024 | 1000+ |

| Study activities of Yifu Primary School in Guilin | 31 May 2024 | 100+ | |

| Study practice activities of Changle No. 1 Middle School on “Knowing Wuyi and exploring the secrets of World Heritage” | 7 May 2024 | 1000+ | |

| “Double reduction” classroom of Wuyishan Experimental Primary School | 13 October 2023 | 350+ | |

| Study and research for primary school students in the post-epidemic era | 9 December 2022 | 380+ | |

| Tea processing course practice for 2020 undergraduates of the Department of Tea Science of Zhejiang University | 1 August 2023 | 30+ | |

| National radio and television integrated media reporters conducted research and study in Fujian | 24 November 2023 | 50+ | |

| School-Enterprise Cooperation | Co-construction of a school-enterprise cooperation practice base with Fuzhou University of Foreign Studies | 10 October 2023 | 100+ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, L.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Fang, J.; Zheng, R.; Liu, H. Landscape Design and Sustainable Tourism at the Wuyistar Chinese Tea Garden, a World Heritage Site in Fujian, China. Buildings 2025, 15, 1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071112

Huang L, Zheng L, Zhang L, Chen J, Chen Y, Fang J, Zheng R, Liu H. Landscape Design and Sustainable Tourism at the Wuyistar Chinese Tea Garden, a World Heritage Site in Fujian, China. Buildings. 2025; 15(7):1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071112

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Lei, Liang Zheng, Lei Zhang, Junming Chen, Yile Chen, Jiaying Fang, Ruyi Zheng, and Haoran Liu. 2025. "Landscape Design and Sustainable Tourism at the Wuyistar Chinese Tea Garden, a World Heritage Site in Fujian, China" Buildings 15, no. 7: 1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071112

APA StyleHuang, L., Zheng, L., Zhang, L., Chen, J., Chen, Y., Fang, J., Zheng, R., & Liu, H. (2025). Landscape Design and Sustainable Tourism at the Wuyistar Chinese Tea Garden, a World Heritage Site in Fujian, China. Buildings, 15(7), 1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071112