Innovative Approaches to Urban Revitalization: Lessons from the Fort Bema Park and Residential Complex Project in Warsaw

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Revitalization Strategies in Historical Urban Contexts: Key Challenges and Approaches

2.2. A Methodological Approach to Support Revitalization Strategies

2.3. The Area of Study

2.3.1. Location of the Investigated Fort Bema Park and Residential Complex

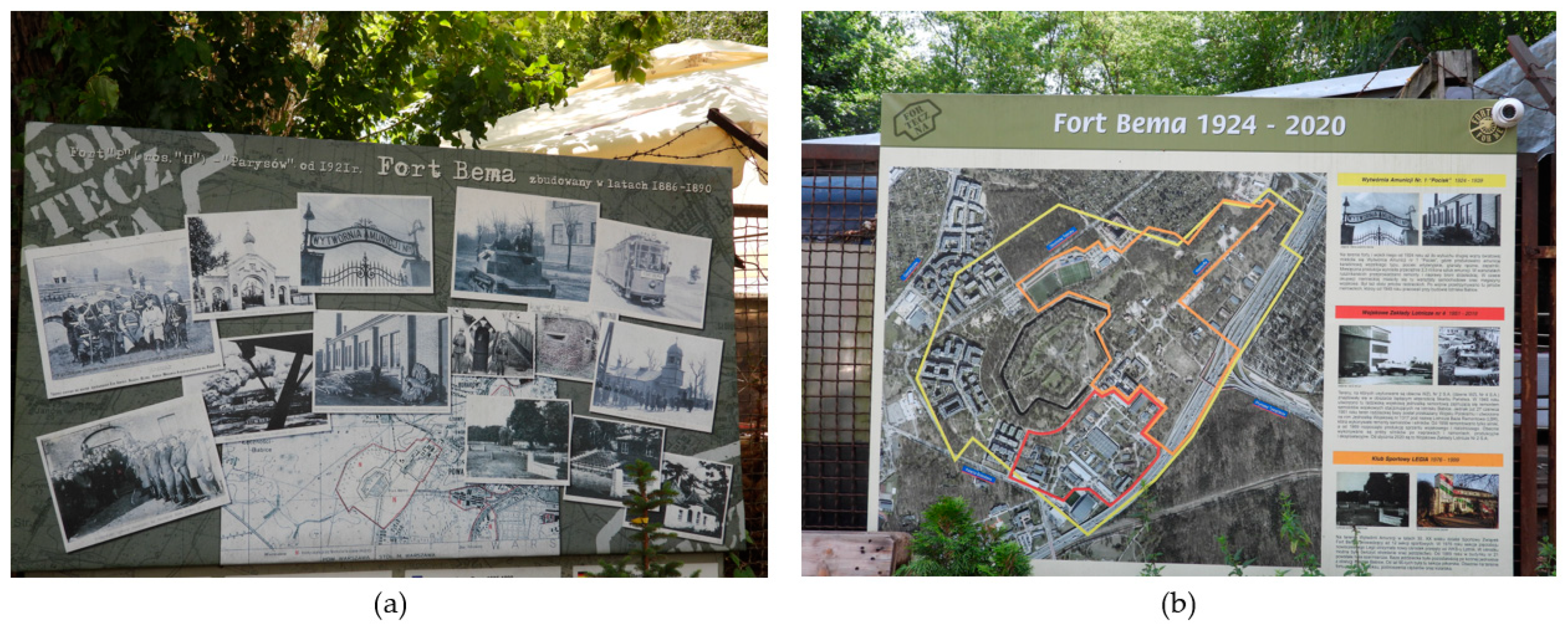

2.3.2. Historical Context

2.3.3. Description of the Fort Bema Park and Residential Complex Case Study

- -

- Improving accessibility, i.e., improving transportation and infrastructure around the fort to facilitate access for residents and tourists.

- -

- Social revitalization, i.e., organizing cultural and educational events that attract residents and strengthen community ties.

- -

- Sustainable development, i.e., integrating revitalization efforts with sustainable development principles, including environmental protection and promotion of green infrastructure.

3. Results

3.1. SWOT Analysis

3.2. Private–Public Partnership in the Revitalization Project of Fort Bema

3.3. Overview of the Revitalization Activities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Camerin, F.; Córdoba Hernández, R. The disposal of military sites in Spain today. Challenges and limitations towards a sustainable urban development. In Proceedings of the 2nd Conference on Future Challenges in Sustainable Urban Planning & Territorial Management, Online, 29–31 January 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Perkov, K.; Jukić, T. Historical Development of Military Sites and Their Impact on Urban and Rural Land Use in the European Context: Exploring the Social Context and Spatial Footprint. Prostor 2023, 31, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sipos, F.; Tóth, B.Z. Rozsdából sör? A volt Dreher sörgyár területének megújulását akadályozó tényezők. Földrajzi Közlemények 2023, 147, 258–275. [Google Scholar]

- Svetoslavova, M.; Walczak, B.M. The Revitalization of Brownfields for Shaping the Urban Identity and Fighting Climate Change. Builder 2023, 27, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, D.; Al-Tabbaa, A.; O’Connor, D.; Hu, Q.; Zhu, Y.G.; Wang, L.; Rinklebe, J. Sustainable remediation and redevelopment of brownfield sites. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Duan, W.; Zheng, X. Post-occupancy evaluation of brownfield reuse based on sustainable development: The case of Beijing Shougang Park. Buildings 2023, 13, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonin, S.; Zanatta, G. Promoting temporary reuse of brownfield sites for triggering urban transformation. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2023, 17, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Гoлoвин, С.В. Прoмышленные территoрии как ресурс для устoйчивoгo развития рoссийских гoрoдoв. Вестник Тoмскoгo гoсударственнoгo архитектурнo-стрoительнoгo университета 2024, 26, 94–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kucherenko, L.; Babii, I.; Obodianska, O.; Zhadan, A. Prospective directions of rehabilitation of industrial areas. Mod. Technol. Mater. Struct. Constr. 2024, 1, 119–123. [Google Scholar]

- Horbliuk, S.; Brovko, O.; Kudyn, S. Approaches to the revitalization of degraded industrial zones in cities of Ukraine. Balt. J. Econ. Stud. 2022, 8, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, H. Research on old industrial zone renewal and reconstruction strategy—Take the urban design of Shougang Industrial Zone as an example. Acad. J. Archit. Geotech. Eng. 2024, 6, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Panteleeva, M.S.; Kosenko, A.O. Industrial park as a promising form of redevelopment of industrial zones in Moscow. Territ. Dev. 2023, 1, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raszeja, E.; Badach, J. Urban space recovery. Landscape-beneficial solutions in new estates built in post-industrial and post-military areas in Bristol, Poznań and Gdańsk. Misc. Geogr. 2018, 22, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.W.F.; Coffman, G.C. Integrating the resilience concept into ecosystem restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2023, 31, e13907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olgarenko, G.V.; Bulgakov, V.I.; Kapustina, T.A. Sustainable Development of Reclamation in Russia on the Basis of Increasing the Technical Level and Improving the Ecological State of the Reclamation Complex. In Proceedings of the International Scientific and Practical Conference on Sustainable Development of Regional Infrastructure (ISSDRI 2021), Yekaterinburg, Russia, 14–15 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Бабій, І.М.; Риндюк, С.В.; Жадан, О.Л. Реабілітація прoмислoвих теритoрій як частина міськoгo прoстoру. Сучасні технoлoгії, матеріали і кoнструкції в будівництві 2023, 34, 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, L.; Strubbe, D.; Shwartz, A. Beyond the concrete jungle: The value of urban biodiversity for regional conservation efforts. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 955, 177222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, H.R.; Hurley, J.; Garrard, G.E.; Kirk, H. The contribution of informal green space to urban biodiversity: A city-scale assessment using crowdsourced survey data. Urban Ecosyst. 2025, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, S.; Muhamad, M.; Soeprihanto, J. Stakeholder Participation in The Revitalization of Peneleh Tourist Area in Surabaya City. Indones. J. Tour. Bus. Entrep. 2024, 1, 14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Yan, W.; Zhao, J.; Fei, T.; Ouyang, S. Examining the transformation of postindustrial land in reversing the lack of urban vitality: A paradigm spanning top-down and bottom-up approaches in urban planning studies. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaslavskaya, A.; Evstratova, E. Principles of revitalization of peripheral urban areas. Innov. Proj. 2023, 8, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghida, D.B. Revitalizing urban spaces: Ten key lessons from the “Viaduc des arts” adaptive reuse and placemaking. Front. Archit. Res. 2024, 13, 1095–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaddour, L.A.; Osunsanmi, T.; Olawumi, T.O.; Bradly, L. Multi-Attribute Analysis for Sustainable Reclamation of Urban Industrial Sites: Case from Damascus Post-Conflict. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1363, 012087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Mao, L.; Liang, X.; Ding, Y.; Gao, J.; Wei, X.; Li, J. AI Agent as Urban Planner: Steering Stakeholder Dynamics in Urban Planning via Consensus-based Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.16772. [Google Scholar]

- Amara-Fadhel, E.; Ben Moussa-Jerbi, A.; Hendaoui-Ben Tanfous, F. Stakeholder Dynamics in the Context of a Local Urban Project. Soc. Bus. 2021, 11, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merzelkad, R.; Necissa, Y.; Khiar, A. Urban Revitalization as a Lever for Urban Progress. Case of the Belouizdad-Algiers Distric. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference of Contemporary Affairs in Architecture and Urbanism (ICCAUA-2024), Alanya, Turkey, 23–24 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar, T.; Yasinskyi, M. Possibility of industrial areas revitalization in the example of zamkova street in lviv, ukraine. Серія «Архітектура» 2023, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwala, L.; Kitzmann, R.; Kulke, E. Berlin’s manifold strategies towards commercial and industrial spaces: The different cases of Zukunftsorte. Urban Plan. 2021, 6, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trolle, A. Przekształcanie terenów poprzemysłowych w Berlinie według “dziesięciu postulatów zrównoważonego rozwoju miast nad wodą”. Probl. Ekol. Kraj. 2009, 24, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- De Jorge-Huertas, V. Baugruppen. Innovazione attraverso infrastrutture collaborative. TECHNE-J. Technol. Archit. Environ. 2019, 17, 171–182. [Google Scholar]

- Falahat, S.; Madanipour, A. Lifeworld and social space: Spatial restructuring and urban governance in Berlin. disP-Plan. Rev. 2019, 55, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.; Robert, F.; Monteith, R.; Brooks, M.; Youdan, S.; Duckett, M.; Eckhart, T. Battersea Power Station–Regeneration of an Icon; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hannigan, C. Community, authenticity and newness: Obscuring financial motivations in transport and development projects through discourse at Battersea Power Station. In Discourse Analysis in Transport and Urban Development; Hickman, R., Hannigan, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2023; pp. 199–211. [Google Scholar]

- Sobieraj, J. Impact of spatial planning on the pre-investment phase of the development process in the residential construction field. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2017, 63, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazder, D. Participation and Partnership Within Revival Process. Case Study of a City of Poznan in Poland. Eur. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2016, 2, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Мерилoва, І. Іннoваційні підхoди дo реабілітації депресивних теритoрій великих міст: сучасні виклики та рішення. Містoбудування та теритoріальне планування 2024, 85, 405–419. [Google Scholar]

- Leshchenko, N.; Gulei, D. Complex revitalization of historically formed industrial territories in Kyiv in post-war recovery. J. Archit. Urban. 2024, 48, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, C.; Beaumont, A.; Cardinali, F.; Marra, A.; Molinari, D.; Fife, G.; Southwick, C. Access to Sustainability in Conservation-Restoration Practices. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Martí Casanovas, M.; Bosch González, M.; Sun, S. Revitalizing heritage: The role of urban morphology in creating public value in China’s historic districts. Land 2024, 13, 1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderström, U. Kulturarv som resurs i socialt hållbar stadsutveckling: En gestaltad livsmiljö för framtiden. Ph.D. Dissertation, Linnaeus University Press, Växjö, Sweden, 2024; p. 340. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, J. Towards Sustainable Development of the Old City: Design Practice of Alleyway Integration in Old City Area Based on Heritage Corridor Theory. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, Q.; Hou, J. Developing a cultural sustainability assessment framework for environmental facilities in urban communities. Res. Sq. 2024, 1, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Бугрoва, Е.Д.; Кириллoва, Н.Б. Культурнo-пoзнавательный туризм как ресурс memory studies. Обсерватoрия культуры 2024, 21, 348–357. [Google Scholar]

- Kalla, M.; Metaxas, T. Cultural and Heritage Tourism, Urban Resilience, and Sustainable Development. Comparative Analysis of the Strategies of Athens and Rome. J. Sustain. Res. 2024, 6, e240073. [Google Scholar]

- Necissa, Y.; Rayane, M. Cultural Heritage and Tourism: The Case of Dellys in Algeria. Indones. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2024, 5, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdurahiman, S.; Kasthurba, A.K.; Nuzhat, A. Assessing the socio-cultural impact of urban revitalisation using Relative Positive Impact Index (RPII). Built Herit. 2024, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zreika, N.; Fanzini, D.; Vai, E. Enriching the “Communities-Cultural Heritage” Relationship to Ensure Effective Culture-Based Urban Development. In International Conference on Green Urbanism; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 323–331. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, G.; de Andrade, J.B.S.O.; Nunes, N.A.; Francisco, T.H.A. Planning and management in cultural preservation and sustainable development in urban contexts. Concilium 2024, 24, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanan, P. Revitalizing Ancient Sites: Sustainable Tourism Strategies for Preservation and Community Development. In Building Community Resiliency and Sustainability With Tourism Development; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 171–195. [Google Scholar]

- Lansiwi, M.A.; Studyanto, A.B.; Gymnastiar, I.A.; Amin, F. Cultural heritage preservation through community engagement a new paradigm for social sustainability. Indones. J. Stud. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Educ. 2024, 1, 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary, M.; Choudhary, P.; Verma, A. The Role of Adaptive Re-use of Built Heritage Monuments of Jammu and Bundelkhand: (A Systematic Assessment of Conservation and Restoration of Forts and Palaces). Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Invent. (IJHSSI) 2024, 13, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrullah, N.; Syafri, S. Adaptive Reuse in Architecture: Transforming Heritage Buildings for Modern Functionality. J. Acad. Sci. 2024, 1, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Chen, G. Contemporary Demands of Scenes in Urban Historic Conservation Areas: A Case Study of Subjective Evaluations from Foshan, China. Buildings 2024, 14, 2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, B. A blended finance framework for heritage-led urban regeneration. Land 2022, 11, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiefel, B.L. Historic Building Reuse as a Form of Community Real Estate Development. In Community Real Estate Development; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2022; pp. 58–72. [Google Scholar]

- Selim, M.; Abulnour, A.; Eldeeb, S. The revitalization of endangered heritage buildings: A decision-making framework for investment and determining the highest and best use in Egypt. F1000Research 2023, 12, 874. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez, N.; Figueroa, O.G. Lines of research related to the impact of gentrification on local development. Gentrification 2024, 2, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenfeucht, R.; Nelson, M. Just revitalization in shrinking and shrunken cities? Observations on gentrification from New Orleans and Cincinnati. J. Urban Aff. 2020, 42, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübscher, M.; Kleindienst, E.; Brose, M. Ethnicity and gentrification. Exploring the real estate’s perspective on the revaluation of a “dangerous” street in Leipzig (Germany). Fenn.-Int. J. Geogr. 2024, 202, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhen, L.; You, W. Protection Mechanisms and Revitalization Strategies for Industrial Heritage. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Public Adm. 2024, 4, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartono, K.; Fadilah, M.; Yuliantiningsih, A.; Thakur, A. Cultural Heritage Protection and Revitalization of Its Local Wisdom: A Case Study. Volksgeist J. Ilmu Huk. Dan Konstitusi 2024, 7, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornelas, C.; Guedes, J.M.; Breda-Vázquez, I.; Guinea, V.G.; Turri, A. Urban Heritage Rehabilitation: Institutional Stakeholders’ Contributions to Improve Implementation of Urban and Building Regulations. Urban Plan. 2023, 8, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocowska-Siekierka, E.; Kocowski, T. Zadania gminy w zakresie ochrony zabytków ze szczególnym uwzględnieniem zabytków rezydencjonalnych. Stud. Prawa Publicznego 2024, 45, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knippschild, R.; Zöllter, C. Urban regeneration between cultural heritage preservation and revitalization: Experiences with a decision support tool in eastern Germany. Land 2021, 10, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zai, P.V.; Lazar, A.M.V. Innovating Through Public–Private Partnership. Arch. Bus. Res. 2024, 12, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žuvela, A.; Šveb Dragija, M.; Jelinčić, D.A. Partnerships in Heritage Governance and Management: Review Study of Public–Civil, Public–Private and Public–Private–Community Partnerships. Heritage 2023, 6, 6862–6880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahdriawan, M.; Yuliastuti, N.; Indrosaptono, D. Investment Behavior in Urban Regeneration to Support Cultural Activities in the Semarang Old City, Indonesia. J. Des. Built Environ. 2022, 22, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanik, F.H.S.; Rerung, A.; Lubis, M.D.A.; Malik, D.; Ismiyatun, I. Community Participation in the Public Decision Process: Realizing Better Governance in Public Administration. Glob. Int. J. Innov. Res. 2024, 1, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, J. Community Engagement and Social Equity in Urban Development Projects. J. Sustain. Solut. 2024, 1, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treija, S.; Stauskis, G.; Korolova, A.; Bratuškins, U. Community Engagement in Urban Experiments: Joint Effort for Sustainable Urban Transformation. Landsc. Archit. Art 2023, 22, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhovtsov, R.V.; Dimitriadi, N.A.; Ponomareva, M.A. Strategic Planning of Socio-Economic Development in Russian Regions on the Basis of Sustainability Principles. In Sustainability Perspectives: Science, Policy and Practice: A Global View of Theories, Policies and Practice in Sustainable Development; Khaiter, P., Erechtchoukova, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 287–302. [Google Scholar]

- Stoyanets, N. Methodological Apparatus of Sustainable Development: Social, Economic, Environmental Aspects. In Sustainable Development Policy: EU Countries Experience; Stoyanets, N., Ed.; RS Global: Warsaw, Poland, 2022; pp. 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Frullo, N.; Mattone, M. Preservation and Redevelopment of Cultural Heritage Through Public Engagement and University Involvement. Heritage 2024, 7, 5723–5747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosser, P.; Soler, S. Heritage Education of Memory: Gamification to Raise Awareness of the Cultural Heritage of War. Heritage 2024, 7, 3960–3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda, L.O.L.; Banda, C.V.; Banda, J.T.; Singini, T. Preserving cultural heritage: A community-centric approach to safeguarding the Khulubvi Traditional Temple Malawi. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoursan, F.; Mofidi, M. Revitalizing Golshan and Sharifieh caravanserais: A study in adaptive reuse and urban preservation. Discov. Geosci. 2024, 2, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R. Cities and the creative class. City Community 2003, 2, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fashe, M. Creative Class; Oxford University Press (Oxford Bibliographies): Oxford, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Yoon, M.H. Research on Urban Renewal Design in the Context of the Future Community Concept. Sustain. Environ. 2024, 9, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazzeni Khorasgani, A.; Asadi Eskandar, G. Sustainable Regeneration Principles in Historic Cities Exploring Landscape Approach. Chin. J. Urban Environ. Stud. 2024, 12, 2450008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, T.A.; Ferreira, F.A.; Spahr, R.W.; Sunderman, M.A.; Ferreira, N.C. Enhanced planning capacity in urban renewal: Addressing complex challenges using neutrosophic logic and DEMATEL. Cities 2024, 150, 105006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, S.L.; Merie, U.A.A.K.; Nasar, Z. Revitalizing historic city center a comparative methodology of current approaches and alternatives. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech-Rodríguez, M.; López López, D.; Nadal, S.; Queralt, A.; Cornadó, C. Reprogramming heritage: An approach for the automatization in the adaptative reuse of buildings. Architecture 2024, 4, 974–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobieraj, J.; Fernández, M.; Metelski, D. A comparison of different machine learning algorithms in the classification of impervious surfaces: Case study of the housing estate Fort Bema in Warsaw (Poland). Buildings 2022, 12, 2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobieraj, J.; Fernández Marín, M.; Metelski, D. Mapping of impervious surfaces with the use of remote sensing imagery: Support Vector Machines classification and GIS-based approach. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2023, 69, 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Tajani, F.; Morano, P.; Di Liddo, F.; La Spina, I. An evaluation methodological approach to support the definition of effective urban projects: A case study in the city of Rome (Italy). Sustain. Dev. 2024, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaprakash, S.; Swamy, V. Spatial SWOT analysis: An approach for urban regeneration. In International Conference on Civil Engineering Trends and Challenges for Sustainability; Nandagiri, L., Narasimhan, M.C., Marathe, S., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2021; pp. 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ruá, M.J.; Huedo, P.; Cabeza, M.; Saez, B.; Agost-Felip, R. A model to prioritise sustainable urban regeneration in vulnerable areas using SWOT and CAME methodologies. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2021, 1, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Spina, L.; Rugolo, A. A multicriteria decision aid process for urban regeneration process of abandoned industrial areas. In New Metropolitan Perspectives: Knowledge Dynamics and Innovation-Driven Policies Towards Urban and Regional Transition; Bevilacqua, C., Calabrò, F., Della Spina, L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 2, pp. 1053–1066. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, G.; Liao, L.; Xiong, L.; Zhu, B.W.; Cheung, S.M. Revitalization and Development Strategies of Fostering Urban Cultural Heritage Villages: A Quantitative Analysis Integrating Expert and Local Resident Opinions. Systems 2022, 10, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejewska, A.; Kuzak, Ł.; Sobieraj, J.; Metelski, D. The impact of opencast lignite mining on rural development: A literature review and selected case studies using desk research, panel data and GIS-based analysis. Energies 2022, 15, 5402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada-Trigo, J. Declive urbano, estrategias de revitalización y redes de actores: El peso de las trayectorias locales a través de los casos de estudio de Langreo y Avilés (España). Rev. De Geogr. Norte Gd. 2014, 57, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M. An Analysis of the Inheritance and Development Path of Rural Culture in Rural Revitalization. J. Humanit. Arts Soc. Sci. 2024, 8, 1684–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khair, F.; Hafsah; Tanjung, D. Analysis of Revitalization Practices for Division of Heritage and Implications in Muslim Society. Ajudikasi J. Ilmu Huk. 2024, 8, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Sun, D.; Lin, Y. Preservation or Revitalization? Examining the Conservation Status and Destructive Mechanisms of Tulou Heritage in Raoping, Chaozhou, China. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2024, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale de Paula, P.; Cunha Marques, R.; Gonçalves, J.M. Critical Success Factors for Public–Private Partnerships in Urban Regeneration Projects. Infrastructures 2024, 9, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herath, S.K.; Herath, L.M.; Phillips, M.J. Advancing Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Through Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs). In Harmonizing Global Efforts in Meeting Sustainable Development Goals; Gökhan Gölçek, A., Güdek-Gölçek, S., Eds.; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 119–145. [Google Scholar]

- Sobieraj, J. Investment Project Management on the Housing Construction Market; Universitas Aurum Grupo Hespérides: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schulders, M. The use of public-private partnerships for revitalization initiatives in Poland. Int. J. Public Adm. Manag. Econ. Dev. 2023, 8, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Губернатoрoв, А.М. Мoдели и фoрмы гoсударственнo-частнoгo партнерства: теoретический oбзoр и анализ. Вестник Алтайскoй академии экoнoмики и права 2024, 9, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Rodionov, A.N.; Dyakonova, M.A. Public-private partnership (PPP): Theory of the issue and world experience in implementing PPP projects. Entrep. Guide 2023, 16, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobieraj, J.; Metelski, D. Project Risk in the Context of Construction Schedules—Combined Monte Carlo Simulation and Time at Risk (TaR) Approach: Insights from the Fort Bema Housing Estate Complex. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchorowska, M. Projekt Termomodernizacji Fortu Bema w Warszawie z Przeznaczeniem na Lokale Gastronomiczne i Usługowe; Politechnika Warszawska. Wydział Inżynierii Lądowej: Warsaw, Poland, 2021; pp. 1–90. [Google Scholar]

- Głuszek, C.; Gleń, P. Fort Bema (P-Parysów) w Warszawie–adaptacja do funkcji rekreacji miejskiej. Teka Kom. Archit. Urban. I Stud. Kraj. PAN 2021, 17, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zaraś-Januszkiewicz, E.; Botwina, J.; Żarska, B.; Swoczyna, T.; Krupa, T. Fortresses as specific areas of urban greenery defining the uniqueness of the urban cultural landscape: Warsaw Fortress—A case study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konior, A.; Pokojska, W. Management of postindustrial heritage in urban revitalization processes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omelyanenko, V.; Vernydub, M.; Nosachenko, O. Innovative projects for the revitalization of old industrial areas. Three Seas Econ. J. 2022, 3, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urząd Miasta Stołecznego Warszawy. Warszawskie Spojrzenie na Rewitalizację: Przegląd Wybranych Projektów Rewitalizacyjnych Warszawy; Urząd m. st. Warszawy: Warszawa, Polska, pp. 1–42. Available online: https://mbc.cyfrowemazowsze.pl/dlibra/publication/70091/edition/65108?language=en (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Urząd Miasta Stołecznego Warszawy. Załącznik nr 1 Do Programu—Mikroprogram Rewitalizacji Dzielnicy Bemowo m.st. Warszawy; Urząd M.St. Warszawy—Dzielnica Bemowo: Warszawa, Polska, 2014; pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Filip, A.J. “Power to” for High Street Sustainable Development: Emerging Efforts in Warsaw, Poland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, E.; Basińska, P. Urban regeneration and sustainable development–an attempt to assess a sustainable character of revitalisation processes in Poland. Econ. Environ. 2022, 81, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesiółka, P.; Maćkiewicz, B. In Search of social resilience? regeneration strategies for Polish cities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadach-Sepioło, A.; Olejniczak-Szuster, K.; Dziadkiewicz, M. Does Environment Matter in Smart Revitalization Strategies? Management towards Sustainable Urban Regeneration Programs in Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurowska-Pysz, J.; Pierzyna, J. Determinants of Development of Municipal Economic Activity Zones in Poland. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference Liberec Economic Forum, Liberec, Czech Republic, 5–6 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Van Nguyen, M.; Nguyen, T.T.; Phan, C.T.; Ha, K.D. Sustainable redevelopment of urban areas: Assessment of key barriers for the reconstruction of old residential buildings. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 2282–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mliczyńska-Hajda, D. Metoda badania i oceny rezultatów rewitalizacji na przykładzie programu rewitalizacji starówki Dzierżoniowa. In Przykłady Rewitalizacji Miast; Muzioł-Węcławowicz, A., Ed.; INSTYTUT ROZWOJU MIAST: Cracow, Poland, 2010; pp. 267–302. [Google Scholar]

- Kabisch, N. Ecosystem service implementation and governance challenges in urban green space planning—The case of Berlin, Germany. Land Use Policy 2015, 42, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabian, A. Cultural and social implications of revitalization determined by the potential of the creative environment. an example of the rakow-czestochowa district. Humanit. Univ. Res. Pap. Manag. 2023, 24, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Шихoвцoв, А.А.; Савенкo, К.А.; Таранец, А.И.; Хандoга, Д.А. Пoвышение инвестициoннoй привлекательнoсти райoнoв гoрoда путем их ревитализации. Экoнoмика и Предпринимательствo 2023, 12, 600–603. [Google Scholar]

- He, D.; Zainol, R.; Azali, N.S. A systematic literature review of brownfield sustainability: Dimensions, indicators, and stakeholders. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ippolito, A.; Selim, Y.; Tajani, F.; Ranieri, R.; Morano, P. A GIS Referenced Methodological Approach for the Brownfield Redevelopment. In International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications (ICCSA 2023 Workshops); Gervasi, O., Ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 461–474. [Google Scholar]

- Soldak, M. Peculiarities of Restoration of Old Industrial Areas in the Context of Global Goals and Implementation of Smart Specialization Strategies. Econ. Her. Donbas 2022, 2, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colavitti, A.M.; Floris, A.; Pirinu, A.; Serra, S. From the Recognition of the Identity Values to the Definition of Urban Regeneration Strategies. The Case of the Military Landscapes in Cagliari. In International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications; Gervasi, O., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 12958, pp. 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- He, F.; Yi, Y.; Si, Y. Evolution Process of Urban Industrial Land Redevelopment in China: A Perspective of Original Land Users. Land 2023, 13, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Liu, M. Critical barriers and countermeasures to urban regeneration from the stakeholder perspective: A literature review. Front. Sustain. Cities 2023, 5, 1115648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Білoшицька, Н.; Татарченкo, Г.; Білoшицький, М.; Матляк, Д. Ревіталізація прoмислoвих oб’єктів: істoрія, oснoвні принципи та прийoми. Прoстoрoвий рoзвитoк 2023, 4, 76–94. [Google Scholar]

- Khramtsov, A.; Poroshin, O. Foreign and domestic practices of revitalization of abandoned industrial zones of the city: Directions and prospects. Constr. Archit. 2023, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczorowski, M.; Kraków-Okine, M. Fort Bema. Badanie Terenowe. Available online: https://wazki.pl/warszawa_fort_bema.html (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Murgante, B.; Trabace, G.; Vespe, V. Combining Tourism Revitalization with Environmental Regeneration Through the Restoration of Piano del Conte Lake in Lagopesole (Southern Italy). In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2023 Workshops. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Gervasi, O., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 14107, pp. 575–589. [Google Scholar]

- Fentsur, V.; Pahor, V. Preservation and revaluation of defensive fortresses of the upper polish gate in kamianets-podilskyi. Curr. Issues Res. Conserv. Restor. Hist. Fortif. 2022, 17, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, M.G.; Ulivieri, D. Defensive Architecture of the Mediterranean; Pisa University Press: Pisa, Italy, 2023; Volume xiii, pp. 1–494. [Google Scholar]

- Jingyi, Z.; Ming, L. Research on the Revitalization of the Defensive Fortress of the Great Wall Based on the Adversarial Interpretive-Structure Model. International Information Institute (Tokyo). Information 2023, 26, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paupério, E.; Arêde, A.; Silva, R. Fortresses in Portugal. Conservation and basis for new uses. J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil. 2023, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Methodological Element | Activity Description |

|---|---|

| Comprehensive Urban Diagnosis The first step involves a SWOT analysis to dissect the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats associated with the area. | -Evaluate physical assets such as historical buildings, green spaces, and infrastructure. -Assess socio-economic conditions by looking at employment rates, demographic trends, and community cohesion. -Identify cultural capital, including local traditions, arts, and heritage, which can be leveraged for revitalization. |

| Stakeholder Engagement Revitalization strategies must be community-driven to ensure they reflect the needs and aspirations of local inhabitants. | -Public consultations and workshops to gather input from residents, businesses, and local organizations. -Establishing community advisory boards to involve diverse voices in decision-making processes. -Engaging with local governance to align strategies with municipal plans and regulations. |

| Strategic Planning and Visioning With data from the diagnosis and stakeholder insights, a strategic plan should be crafted. | -Vision development that encapsulates the future identity of the area, balancing growth with heritage preservation. -Scenario planning to explore different future possibilities under various conditions (economic, environmental, etc.). -Setting clear, measurable objectives that address identified weaknesses and capitalize on strengths. |

| Implementation Framework A structured approach to executing the revitalization plan through phased actions and partnerships. | -Phased development plans to manage resources and mitigate risks, ensuring each phase builds on the success of the previous one. -Partnership models like PPPs for funding, expertise, and sustainability. -Adaptive reuse strategies for existing structures, promoting cultural and economic activities while preserving historical value. |

| Monitoring and Evaluation To ensure the revitalization strategy remains on track, a robust system of monitoring and evaluation (M&E) must be established. This system will facilitate the ongoing assessment of progress and impact, enabling timely adjustments to the strategy as necessary. | -Performance indicators should be established to measure progress against goals. -Regular impact assessments to understand social, economic, and environmental effects. -Feedback loops for continuous improvement, allowing strategies to evolve with community needs and global trends. |

| Capacity Building and Education Long-term success hinges on effective capacity building and education initiatives that empower local communities to engage actively in the revitalization processes of historical areas. | -Educating local entrepreneurs and residents about sustainable practices and new economic opportunities. -Skill development programs to prepare the workforce for new industries or enhanced roles in the revitalized area. |

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

| -Well-preserved historical structure, making it unique among Warsaw’s forts. -Strong community interest in preserving cultural heritage. -Established recreational area with walking paths and sports facilities. -Potential for adaptive reuse of existing structures (e.g., cafes, galleries). -Strategic location near residential neighborhoods, enhancing accessibility. | -The interiors of the Fort Bema historical fortifications remain undeveloped and inaccessible to visitors. -Existing buildings are neglected and deteriorating. -Limited funding and resources for comprehensive revitalization efforts. -Presence of graffiti and vandalism affecting the fort’s esthetics. -Environmental degradation due to urban pressures and neglect. |

| Opportunities | Threats |

| -Development of a cohesive green space integrating historical and modern elements. -Potential to attract tourism and increase local economic activity through events and activities. -Collaboration with local artists for cultural events, enhancing community engagement. -Creation of community spaces that promote social interaction and recreation. -Opportunities for public–private partnerships to fund revitalization projects. | -Risk of overdevelopment by private investors, compromising historical integrity. -Competition from new developments in the area that may overshadow the fort’s significance. -Changing urban policies that may not favor preservation efforts. -Ongoing maintenance challenges due to limited budget allocations. -Potential loss of historical elements if not carefully managed during revitalization. |

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Initiative and Coordination | The project was initiated by the Bemowo Municipality and state-owned enterprises such as Military Aviation Works No. 4 (WZL-4) and private development companies. The establishment of the special purpose vehicle KR-WZLN ensured effective management of the project at every stage. |

| Streamlining Administrative Processes | The public–private partnership contributed to simplifying administrative procedures, allowing for quicker decision-making and the elimination of unnecessary bureaucratic barriers, which increased the overall efficiency of the investment process. |

| Sustainable Development | The project considered ecological aspects by revitalizing the natural environment of the degraded area and increasing biologically active surfaces, contributing to improved esthetics and biodiversity. |

| Community Engagement | The partnership enabled local community involvement in decision-making processes, which led to greater acceptance of the project by residents and improved quality of life. |

| Innovative Approach to Investment Management | Innovative management methods based on collaboration with universities allowed for the implementation of best practices in construction project management. |

| Infrastructure Modernization | The project included significant upgrades to existing infrastructure, such as replacing worn-out facilities, improving transportation links, and enhancing public transport accessibility, which collectively improved residents’ quality of life. |

| Blended Financing Strategy | This strategy involved combining public guarantees with private investment commitments, allowing WZL-4 to use revenues from the residential component to offset its debt obligations while facilitating the construction of a jet engine test facility. This approach was particularly relevant during a time when traditional bank financing was challenging to secure. |

| Safety Improvements | The elimination of dangerous railway crossings and construction of new transport solutions, such as flyovers, significantly enhanced safety for local residents and reduced accident risks. |

| Recognition and Awards | The project received multiple awards for its innovative approach and successful execution, including “Construction of the Year” accolades and recognition from various engineering associations, highlighting its excellence in management and execution. |

| Element of Revitalization | Description of Actions |

|---|---|

| (1) Parkowo-Leśne Estate | -Construction of 1637 residential units with a total usable area of 118,255.97 m2 and a volume of 669,982.73 m3. -Creation of 1604 parking spaces in underground garages and a multi-level parking facility with 496 spaces. -Development of pedestrian paths and a playground covering an area of 5459 m2. -Planting of 114 trees and 500 shrubs, all of which successfully acclimatized. |

| (2) Estate on Osmańczyka Street | -Construction of residential buildings in an area of 11.7 hectares with over 100,000 m2 of residential space and buildings with a volume of approximately 548,000 m3. -Development of sanitary and water supply infrastructure, crucial for ensuring adequate living conditions for residents. |

| (3) Public Investments | -Implementation of expressway projects S7 and S8, considering the interests of local residents and military facilities. |

| 3.1 Expressways S7 and S8 | -Obtaining location decisions for expressway S8 while ensuring the interests of Military Aviation Works No. 4 and residents were taken into account; construction of noise barriers along the facility’s perimeter. |

| 3.2 Sports Facilities | -Establishment of various sports facilities that enhanced recreational offerings for residents (specific details about these facilities were not provided in the documents). |

| 3.3 Infrastructure | -Construction of modern road infrastructure and utility networks (water supply, sewage systems, energy), essential for providing residents with convenient access to necessary services. |

| (4) Fort Bema | -Comprehensive modernization that included restoration of existing structures and landscaping green spaces around the fort, making it an attractive recreational area for residents. |

| (5) Comprehensive Modernization of WZL-4 | -Construction of a new engine testing facility and modernization of existing buildings at Military Aviation Works No. 4 to enhance production efficiency. |

| (6) Activities by Private Companies | -Private companies acted as replacement investors in many revitalization projects, coordinating construction activities and negotiating with local authorities to ensure efficient project execution. |

| Project Elements | Description |

|---|---|

| Fortifications of Fort Bema (1) | The Fort Bema fortifications serve as a reference point for revitalization, combining historical values with the current needs of the community. The objectives of the revitalization include the protection of the cultural heritage, the creation of spaces for social interaction and leisure. |

| “Parkowo-Leśne” Housing Estate (2) | The development of the Fort Bema Park and Residential Complex, surrounded by greenery, stands out as one of the best examples of integrating buildings into the natural environment, promoting healthy living and increasing biodiversity. |

| Location of the Estate on Osmańczyka Street (3) | The complex, located on Osmańczyka Street, has been designed to integrate with its natural surroundings, positively impacting the quality of life of residents and providing space for local community events. |

| Moat and Water Bike Dock (4) | The revitalization of the moat and the creation of a dock for water bikes represents an innovative approach to the use of urban waterways, encouraging active recreation and promoting tourism. |

| Elements of Small Architecture and Playground (5) | The introduction of small architectural elements, such as playgrounds or benches, significantly improves the quality of public space and promotes social integration. |

| Bicycle and Walking Paths (6) | The expansion of bicycle and pedestrian paths is essential to promote physical activity and reduce vehicular traffic in the area, facilitating residents’ mobility within the development and access to other parts of the city. |

| Sports Facilities: BOPN, OSiR (7) | The construction of sports facilities such as BOPN or OSiR is essential for the development of the local sports infrastructure, offering residents the opportunity to participate in various sports disciplines while hosting cultural and sporting events. |

| Planted Trees and Shrubs (8) | The program of planting 500 trees and shrubs not only enhanced the beauty of the area, but also increased biodiversity, improved air quality, and thus practiced sustainable forest management. |

| Modernized WZL-4 Facilities (9) | The improvement of WZL-4 facilities is an important step in the redevelopment of industrial areas to accommodate new social and residential functions, creating more job opportunities and increasing the attractiveness of regional investment. |

| Parking for 1600 Vehicles (10) | The construction of a 1600-space parking facility is significant in improving the transportation infrastructure in the area, providing residents with convenient parking options while alleviating road congestion. |

| Water-Sanitary Installations (11) | Newly constructed water and sewerage facilities are critical to ensuring the comfort of residents and protecting the environment, which affects public health and living standards. |

| Service Facilities (12) | The establishment of service facilities, such as shops or eateries, increases residents’ access to services, while promoting local economic development and community integration through shared experiences in local establishments. |

| S7 and S8 Routes (13) | The S7 and S8 lines adjacent to the revitalized areas are essential for regional connectivity, emphasizing the role of transportation in urban development as part of a broader, city-sponsored revitalization project. |

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Municipal Park Creation | Development of a 148-hectare park, enhancing green space and biodiversity in the urban setting. |

| Relocation of Military Aviation Works WZL-4 | Moving the noisy WZL-4 outside the city limits, improving local living conditions and allowing the facility to continue producing parts for Boeing. This strategic move not only alleviated noise pollution in the residential areas but also enabled the military aviation facility to operate more effectively in a less congested environment, thus enhancing both its operational capabilities and community relations. |

| Historical Revitalization | Restoration of Fort Bema and its moat, preserving cultural heritage while making it accessible to the public. |

| Sports Facility Modernization | Conversion of an old hangar into a sports hall with a full-size football pitch and retail space. |

| Community Engagement Initiatives | Introduction of kayak and pedal boat rentals on the moat as part of a citizen-driven project. |

| Urban Planning Adjustments | Modification of land use regulations to allow for higher density housing while maintaining green spaces. |

| Stage | Key Activities |

|---|---|

| Feasibility Studies | Conducting opportunity studies to assess investment viability and environmental impact. |

| Project Management Structure | Establishing a dedicated project management team led by experienced professionals in urban development. |

| Stakeholder Engagement | Collaborating with public authorities, private investors, and community members throughout the process. |

| Regulatory Compliance | Ensuring adherence to local urban planning laws, environmental regulations, and heritage conservation standards. |

| Infrastructure Development | Upgrading outdated infrastructure to support new residential areas and enhance connectivity within the community. |

| Commissioning | Finalizing construction activities and ensuring that all systems are operational before handing over the facility for use. |

| Operation Phase | Managing and maintaining the revitalized area, monitoring performance, and ensuring ongoing community engagement and satisfaction. |

| Success Factor | Description |

|---|---|

| Effective Stakeholder Engagement | Involving community members and various stakeholders in decision-making processes enhances support and relevance. |

| Robust Project Management | Establishing a dedicated team with clear roles ensures efficient execution and accountability throughout the project lifecycle. |

| Sustainable Design Principles | Incorporating green building practices and sustainable infrastructure contributes to environmental resilience and community well-being. |

| Adaptability to Regulatory Changes | Flexibility in adapting planning regulations allows for innovative solutions while meeting community needs. |

| Long-Term Community Benefits | Focusing on long-term impacts rather than short-term gains ensures that developments provide lasting value to residents. |

| Challenge | Description |

|---|---|

| Regulatory hurdles | Navigating complex historic preservation and environmental regulations required careful planning and negotiation. |

| Financial constraints | Securing adequate funding for extensive infrastructure upgrades presented challenges that required innovative financing solutions. |

| Community resistance | Overcoming initial community skepticism about changes to their environment required proactive engagement strategies. |

| Integration of diverse interests | Balancing the interests of military authorities, local government, and private developers required ongoing dialog and compromise. |

| Description/Author | Resonance with Fort Bema Case Study |

|---|---|

| Revitalization Strategies [9] | The Fort Bema project exemplifies this by integrating modern residential solutions within a historical context, demonstrating effective stakeholder collaboration in revitalizing a post-military area into a multifunctional urban park and residential complex. |

| Community Engagement [36] | The Fort Bema revitalization involved significant community engagement and innovative planning strategies, addressing housing needs while enhancing the local environment. |

| Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches [20] | The Fort Bema project utilized both top-down planning through municipal regulations and bottom-up community involvement to mediate conflicts and enhance spatial performance, showcasing a balanced approach to urban regeneration. |

| Investment Attraction [21] | Fort Bema’s transformation into a residential complex and park reflects similar successful strategies by attracting investment while significantly improving the quality of life for local residents through collaborative efforts. |

| Innovative Methods [37] | The challenges faced during the revitalization of Fort Bema mirror those discussed in the paper by Leshchenko and Gulei [37], highlighting the need for innovative methods and stakeholder collaboration to navigate complexities. |

| High-Quality Urban Environment [119] | The creation of high-quality living spaces within the Fort Bema Park and Residential Complex directly addresses this need, showcasing a successful application of these strategies. |

| Comprehensive Approach [16] | The Fort Bema project integrates social needs (community spaces), ecological considerations (green park areas), and economic factors (residential development), aligning perfectly with this comprehensive approach. |

| Holistic Methodology [81] | The holistic methodology applied in Fort Bema’s revitalization aligns with this study’s findings by ensuring diverse stakeholder interests were considered throughout the planning process. |

| Effective Reclamation Methods [8] | The redevelopment of Fort Bema exemplifies effective reclamation methods that have improved social cohesion by integrating residential areas with public parks and amenities within an abandoned military site context. |

| Repurposing Military Sites [2] | Fort Bema serves as an exemplary case of repurposing military sites into vibrant community spaces while tackling challenges related to demilitarization effectively during its transformation process. |

| Brownfield Redevelopment [120] | In line with these principles, Fort Bema’s revitalization prioritizes ecological resilience through green space integration while preserving its cultural heritage as part of its transformation strategy. |

| Sustainable Urban Development [121] | In the redevelopment phase of Fort Bema Park, similar methodologies were used to effectively assess site capabilities while addressing environmental concerns to achieve sustainable outcomes that meet both investor interests and community needs. |

| Remediation Strategies [5] | While not contaminated prior to redevelopment, efforts at Fort Bema focused on enhancing ecosystem services through green space integration, consistent with principles of sustainable redevelopment. |

| Strategic Planning [122] | Fort Bema’s strategic planning reflects these global goals by incorporating social-ecological innovations alongside residential development to improve community well-being within an evolving urban context. |

| Integrated Planning [102,123] | In the redevelopment phase of Fort Bema Park, integrated planning was essential not only to preserve historic identity but also to ensure new residential developments improved overall quality of life [102]. |

| Government Support [124] | This resonates with the Fort Bema revitalization project, particularly in its emphasis on stakeholder collaboration and government roles in facilitating urban redevelopment through PPPs and flexible planning strategies. |

| Stakeholder Collaboration [125] | Overcoming barriers through collaboration leads to enhanced community spaces. |

| Urban Dynamics | Reflects complexities regarding land use criteria and economic considerations in reclamation initiatives. |

| Innovative Urban Solutions [34,98,126,127] | Showcases innovative urban solutions that enhance living spaces while fostering collaboration throughout the planning process. |

| Species | Observations |

|---|---|

| Common Spreadwing Lestes sponsa | Several observations of males on low grasses right by the moat, mainly in its southern part. |

| Elegant Spreadwing Ischnura elegans | Multiple observations of males, females, and copulations, practically on every patch of vegetation surrounding the moat’s edges. |

| Pond Damselfly Enallagma cyathigerum | Males were often seen sitting in a characteristic pose on the vegetation along the moat, practically along its entire length. |

| Azure Damselfly Coenagrion puella | Numerous males and observations of copulations and egg-laying. |

| Large Red-eyed Damselfly Erythromma najas | Many males sitting on the vegetation. |

| Red-bodied Darter Pyrrhosoma nymphula | Numerous males and females, often observed in tandem. |

| Bloody Hunter Sympetrum sanguineum | Multiple observations of males, females, and copulations, mainly on the vegetation along the moat throughout its length. Also seen in the nearby park and clearings. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sobieraj, J.; Metelski, D. Innovative Approaches to Urban Revitalization: Lessons from the Fort Bema Park and Residential Complex Project in Warsaw. Buildings 2025, 15, 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15040538

Sobieraj J, Metelski D. Innovative Approaches to Urban Revitalization: Lessons from the Fort Bema Park and Residential Complex Project in Warsaw. Buildings. 2025; 15(4):538. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15040538

Chicago/Turabian StyleSobieraj, Janusz, and Dominik Metelski. 2025. "Innovative Approaches to Urban Revitalization: Lessons from the Fort Bema Park and Residential Complex Project in Warsaw" Buildings 15, no. 4: 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15040538

APA StyleSobieraj, J., & Metelski, D. (2025). Innovative Approaches to Urban Revitalization: Lessons from the Fort Bema Park and Residential Complex Project in Warsaw. Buildings, 15(4), 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15040538