Abstract

Geotextiles are a commonly used green material which can improve the water holding capacity of soil. However, the effects of density on evaporation and cracking of geotextile–soil composites are still unclear. The results indicate that the addition of geotextiles divides the soil water evaporation into five stages: constant loss stage, rapid deceleration stage, secondary deceleration stage, tertiary deceleration stage, and residual loss stage. When the geotextile density was 0, 200, 400 and 600 g/m2, the deceleration stage accounted for 55.7%, 64.3%, 70.4% and 74.8%, respectively, of the total evaporation time of water in the soil. Compared with soil without geotextiles when the geotextile density was 200, 400 and 600 g/m2, the soil average residual water content rose by 34.8%, 127.1% and 247.0%, respectively. When the geotextile density was 600 g/m2, the crack rate and fractal dimension were reduced by 44.44% and 18.39%, respectively. Geotextiles can provide fiber interleaving points and pore spaces, and high-density geotextiles can effectively prevent the movement of fine particles and form a thicker layer of fine particles to enhance the water retention and crack resistance of the soil, so that the geological environment contributes to sustainable development. The application of geotextile–soil composites can achieve long-term sustainable protection against soil evaporation and cracking.

1. Introduction

Geotextiles are made from natural or synthetic fibers. The greatest advantage of synthetic fibers is that they are often produced from petrochemical products, can achieve uniform strength, length and color, and can be easily customized for specific applications. Geotextiles have good tensile strength, good corrosion resistance and anti-aging properties, and can be adapted to soils with different pH. Because there is a gap between the fibers, geotextiles have good water permeability and filtration isolation function. The geotextile is placed between the surface soil layer and the adjacent soil layer as a filter material, which can effectively prevent the passage of soil particles, while the water and gas can be discharged freely, reducing the damage to the soil environment. Geotextile coverings for moisture conservation can reduce soil water evaporation, prevent the loss of soil nutrients, and maintain soil nutrients [,]. Geotextiles can effectively prevent the water in the soil from evaporating and improve the efficiency of water use in soil, especially in arid areas or areas with scarce water resources [,,]. Geotextiles can also reduce the erosion of soil by wind and rain, maintain the structural integrity of the soil, and prevent soil erosion and slope landslides [,]. Geotextiles buried in soil can increase the friction within the soil and improve the stability of buildings. Geotextiles can also be used as a reinforced material with high tensile strength and low elongation, and have the characteristics of low creep performance, good durability and high interfacial friction coefficient. In addition, geotextiles can provide good soil retention, increase the fastness of plant roots, and further strengthen the soil’s ability to resist erosion. In addition to the above applications in soil and water moisture retention, geotextiles have also been used in various engineering fields. In civil engineering, geotextiles can protect the stability and durability of engineering structures. In railways and dams and other projects, geotextiles can be used to prevent soil seepage and erosion and to prevent water intrusion into the soil that results in soil loosening, settlement or damage []. In pavement engineering, the moisture maintenance of geotextiles can maintain the soil moisture and stability, and extend the service life of the project.

The most direct harm caused by water loss in soil is the cracking phenomenon in some farmland, resulting in a decline in soil quality, reducing crop quality, yield and agricultural harvests [,,]. Extreme soil drought will threaten human survival. Water loss from the soil further worsens the ecological environment. Water loss from soil leads to the degradation of grassland vegetation, and the climate drought aggravates the process of land desertification [,,]. There has been a trend of soil water loss and damage for many years in China, and droughts occur in all seasons, which is very unfavorable to the ecological environment [,]. Long-term water loss can further degrade the soil and even have the adverse effect of permanently reducing water retention in the soil of these lands [].

Climate change has a huge impact on soil structure, especially when soil water is lost in large amounts during drought []. After the soil dries and loses water, the shrinkage and separation of soil particles produce cracks, and the formation of cracks further increases the soil water evaporation. Soil cracking can damage the integrity, strength and stability of soils and cause geotechnical and geological environmental problems such as damage to embankments and shallow foundation buildings []. If the soil cracks near the surface of landfill and the impervious layer of waste isolation, the soil cracks greatly increase the water conductivity and permeability, which leads to the risk of pollutants leaking and environmental pollution [,]. Soil cracks will change the soil texture and pore structure, and then change the soil’s internal flow channels and hydraulic properties [,,]. The cracking characteristics during evaporation are affected by the soil mineral composition and the surrounding environment. Factors such as the clay content in soil, mineral composition, content, modifiers, texture and organic carbon all affect soil cracking [,]. The alternations of dry and wet in the surrounding environment, vegetation growth, wind speed, humidity and temperature are also environmental parameters that affect the drying and cracking of soil [,].

Geotextiles are widely used in the filtration layer of modern municipal solid waste landfill, highway maintenance and soil and water conservation in farmland [,]. Geotextiles have excellent corrosion resistance, and acid and alkali resistance, which can resist the erosion by a variety of chemical substances. Geotextiles have strong tensile ductility and anti-ultraviolet, anti-aging ability. The capillary boundary and preferential flow formed by geotextiles in the soil are used to protect and reduce the infiltration of rainwater into the soil structure, so as to maintain the stability of the soil structure [,]. The application of geotextiles to soil mainly has the function of leakage and drainage, isolation, filtration and reinforcement. Geotextiles allow water to drain rapidly and flat along drainage channels inside the geotextiles. Geotextiles have high tensile resistance, tear resistance, good toughness and erosion resistance, and can separate two materials with greater permeability than the geotextile itself so that they can play their respective roles. When the water flows through the geotextile, the soil particles that can effectively stop the water flow maintain the stability of soil and water engineering. When the geotextile is in the tension state, it produces an effect similar to the lateral constraint pressure on the soil, which causes the soil to have a higher shear strength and deformation modulus and increases the integrity and stability of the soil as a whole. Even when shear failure occurs in the soil, geotextiles can be attached to the soil surface to resist the emergence of soil shear surfaces, thus decreasing the risk of geological hazards in the area.

For example, in water-stressed countries such as Israel, geotextiles are used to mulch agricultural irrigation systems by covering the soil surface to reduce evaporation loss of water, improve water retention, and extend irrigation cycles. In some vineyards in California, geotextiles are used as soil surface coverings to slow water evaporation and keep the soil moist, especially during the hot, dry summer months. This method helps farmers save irrigation water and increases the stability of crop growth. In arid areas of Australia, geotextiles are used to prevent soil erosion, especially in soil and water conservation works in arid areas. Geotextiles can effectively stabilize the soil, reduce the erosion of the topsoil by water flow, and prevent soil erosion. These application cases show that geotextiles can effectively control water evaporation, reduce soil wind erosion and soil erosion. Through the use of geotextiles, it is possible to achieve effective use of resources and improve land productivity and ecological stability, especially in arid and semi-arid areas. However, geotextiles with different densities affect the evaporation rate of water from soil due to their varying water absorption. Geotextiles with different densities of the same cover layer will affect the drying and cracking characteristics of soil by changing the water evaporation from soil.

Therefore, the aim of this paper was to clarify the influence geotextiles of different densities on soil water evaporation and cracking in order to assess their effectiveness for soil and water conservation. On the basis of laboratory experiments, the influence of different density geotextiles on soil water evaporation and cracking properties in arid areas, as well as their mechanisms, were studied in detail.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The effects of different density geotextiles (Shengbin Geotechnical Materials Co., Ltd., Shijiazhuang, Hebei, China) on soil evaporation and cracking were investigated. In this experiment, three nonwoven filament geotextiles of different densities were studied. The geotextile fiber type was polyester fiber. This geotextile has good stabilization function, and is often used for water retention in landscaping. The density of a geotextile its mass per cubic meter, which can be calculated by a straightedge and an electronic balance. The densities of the three geotextile samples were 200, 400, 600 g/m2, respectively. The geotextile was placed on the reference plate, and a circular press-foot parallel to the reference plate was used to apply a pressure of 400 cN to the sample; the press-foot area was 2000 mm2, the compression time was 30 s, and the distance between the two plates was used as the thickness measurement value of the geotextile sample. The pore sizes of different geotextiles were measured using a movable fabric density mirror (a 5× magnifying glass with a marker line). The thicknesses of the geotextile samples with three different densities of 200, 400 and 600 g/m2 were 1.7, 3.0 and 4.1 mm, respectively. The pore sizes of the 200, 400 and 600 g/m2 geotextile samples were 12.1, 10.2 and 8.7 mm, respectively. The breaking strength, CBR bursting strength and tearing strength of the sample were measured by the CMT-50 electronic strength testing machine. In the breaking strength test, the geotextile was cut into a sample of 200 mm × 140 mm, and the upper and lower ends of the sample were protected by 200 mm × 20 mm kraft paper to avoid stress concentration causing damage to the sample at the clamp. During the CBR bursting strength test, a geotextile sample with a diameter of 150 mm was cut and fixed in the ring fixture with an inner diameter of 200 mm. Then the cylindrical top press rod with a diameter of 50 mm was vertically pushed towards the geotextile sample at a speed of 50 mm/min. The test was stopped when the force dropped to 0 N. During the tearing strength test, each geotextile sample of size 200 mm × 75 mm was cut with a 15 mm long incision in the middle, and the tensile speed was set to 50 mm/min. Table 1 shows the corresponding parameters of the geotextiles. Two geotextile samples with uniform texture were selected for each of the three different weights to cut into a circle. Geotextiles of different densities were placed in the middle of different groups of soil samples (silt 2 cm above the geotextile and silt 2 cm below). The soil layer was levelled and treated before the geotextile was placed. The soil was not compacted, and the H2025G electric mixer was used for stirring until the mud slurry was stirred evenly and there were no bubbles. At this time, the soil layer was maintained in a flat state.

Table 1.

Corresponding parameters of geotextiles.

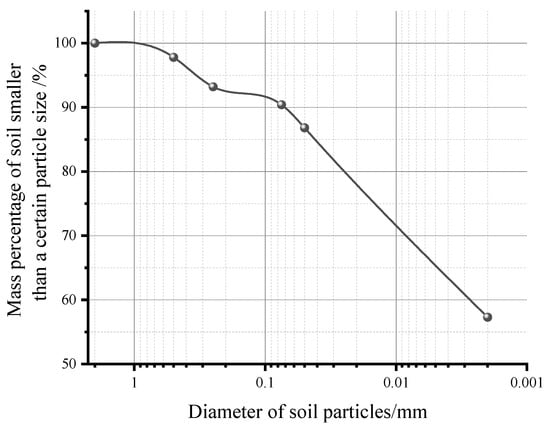

The soil samples were taken from Hanzhong, Shaanxi Province, which is located in the southwest of Shaanxi Province with a total area of 27,246 km2. Hanzhong is about 1200 km away from the southeast sea, in the north of subtropical China, and has a warm temperate continental monsoon climate. The climate in this region has obvious characteristics of a monsoon climate, and the four seasons are more obvious than those in tropical areas. In general, the spring and autumn are slightly shorter, while the winter and summer are slightly longer. The winter is cold and dry, and the late spring to autumn is hot and rainy. Extreme weather such as droughts, autumn rain and heavy rain often occur. The Hanzhong Basin, hills and low mountainous areas have four distinct seasons. The average temperature distribution in Hanzhong City is lower in the northern and southern mountains than in the hills, and higher in the southern slopes of the Qinling Mountains than in the northern slopes of the Bashan Mountains. The temperature of the hills is between 14.4 °C and 14.7 °C, and in the southern slopes of Qinling, it is lower than 12.0 °C, while the northern slopes of Bashan have temperatures lower than 14.0 °C. The soil samples were taken 10 cm below the surface. The corresponding properties of the soil are shown in Table 2. The grain size distribution of soil is shown in Figure 1. According to the USCS soil classification, this test soil is a high-plasticity clay (CH).

Table 2.

Corresponding parameters of soil.

Figure 1.

Grain size distribution curve of soil.

2.2. Experiments

2.2.1. Test Process

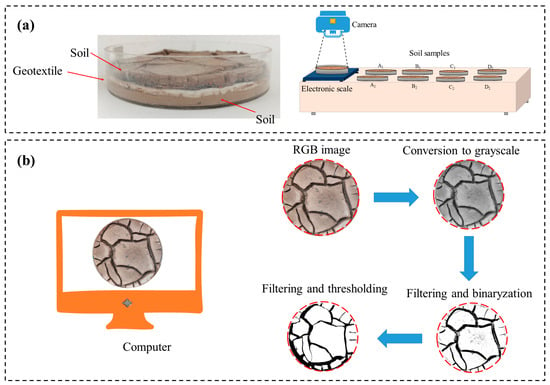

In this study, soil was prepared into a muck state by adding suitable distilled water, and then air-dried to a muck slurry with a saturation of 70%. The slurry was poured into a round container, and the height of the silt was 4 cm. As shown in Figure 2a, geotextile A, B and C (200, 400, 600 g/m2) of different densities were placed in the middle of different groups of soil samples (silt 2 cm above the geotextile and silt 2 cm below). All the samples were stored in a multifunctional climate simulation laboratory with a temperature of 20 °C. Each experimental group included a set of parallel samples, that is, each sample was tested twice. The p value and standard deviations in statistical analysis were calculated on SPSS 22.0 version. The multifunctional climate laboratory can simulate the actual soil evaporation environment, allowing study of the cracks in the process of soil sample shrinkage in real time. At the same time, the weight change of the sample was monitored in real time. Table 3 shows the experimental variables and experimental conditions.

Figure 2.

Flow of crack test and crack image processing (a) test process (b) image binaryzation.

Table 3.

Experimental variables and experimental conditions.

2.2.2. Parameter Calculation

The weight of each sample was measured at 4 h intervals by an electronic balance test. The evaporation rate (Ev) and water content (w) were calculated based on the change in sample weight. The evaporation rate and water content of the sample is as follows:

where t is evaporation time, ∆m is the difference in the sample weight, m0 is the initial water weight, and md is the dry soil weight.

A digital camera was used at a distance of 20 cm from the sample to take images at specific time intervals to observe crack development. The image processing process is shown in Figure 2b. The cracks were recognized based on the color contrast between cracked and non-cracked areas of the soil sample surface. The crack analysis and calculation were all performed by the box-counting method. The crack rate and fractal dimension (FD) were used to describe the crack evolution. The crack rate is the percentage of the crack area divided by the sample total surface area. The crack rate (CD) can be calculated according to the dark pixels in the crack region as:

where ND is the area of dark pixels and NT is the total area of pixels.

In nature and human activities, irregular shapes of complex materials are common, such as winding rivers and rolling mountains, and these have fractal characteristics. Fractal features refer to the fact that things have self-similarity, that is, they are globally and locally similar objects. At present, fractals describe the irregular phenomenon that things have certain rules. These phenomena with fractal characteristics exist in many areas, and it is difficult to describe them with traditional geometric knowledge. Traditional Euclidean geometry and topological geometry have difficulty describing them. In order to better describe this kind of matter, fractal theory came into being. Therefore, fractal theory has been developed in various fields, such as mathematics, materials science and geology. With the development of science, fractal theory has been introduced into various disciplines to reveal the deep laws of complex phenomena in nature. Among them, quantitative parameters such as FD can be used to quantitatively study the complex structure of things. In geology, fractal theory is mainly applied to the complexity of geological structures. In recent years, the study of fractal theory in China and globally is still in the initial stages. In this study, FD is used to study the characteristics of soil cracking. To further quantify cracks, FD are used. The box counting dimension (D) is used to quantify the FD. The box count size is defined as:

where N(r) is the number of boxes containing the crack, and r is the box side length.

According to the calculation, the number of grid cells of cracks for geotextile soils of different densities is shown in Table 4. The corresponding FD can be calculated according to the logarithmic relationship between grid cell size and number of grid cells.

Table 4.

The number of grid cells in the samples of cracking for geotextile soils of different densities.

3. Results

3.1. Influence of Geotextiles on Soil Water Evaporation

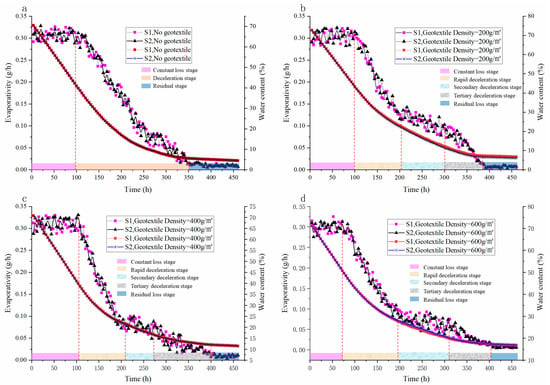

The change in water loss processes of geotextile soils with different densities over time is shown in Figure 3. The water loss rate of samples with different densities of geotextiles showed disparate stage trends. With or without the addition of geotextiles, the water loss rate of samples showed a step-like decreasing trend over time. As shown in Figure 3a, under ideal conditions, water evaporation in normal soil shows three stages. 0~96 h is the constant rate stage, 96~352 h is the deceleration stage, and 352~460 h is the residual stage. The average evaporation rate of normal soil (Figure 3a) in the constant rate stage is 0.306 g/h, and in the deceleration stage it is 0.142 g/h, while the average evaporation rate in the residual stage is 0.010 g/h. After the addition of geotextiles (Figure 3b–d), the slope of the deceleration stage of normal soil evaporation obviously decreased three times, and the evaporation rate of the soil water decreased significantly. The evaporation rate of a geotextile soil during the whole process can be described in five stages: “constant loss stage, rapid deceleration stage, secondary deceleration stage, tertiary deceleration stage and residual loss stage. The different evaporation stages are defined by the slope change of the soil evaporation rate. The slope of the initial evaporation rate of the soil is 0, and the uniform evaporation in this stage is a constant loss stage. Then, the evaporation rate decreases during the rapid deceleration, second deceleration and tertiary deceleration stages, and the last stage of evaporation is the residual loss stage. The average evaporation rate for each stage is the average of the evaporation rates for all data points in that stage. The combined stages of rapid deceleration, secondary deceleration and tertiary deceleration of water evaporation in the geotextile soil can also be called the deceleration stage. The water content of soil gradually decreases to the residual state, and the sample water content tends to be basically unchanged.

Figure 3.

Water loss process of geotextile soils with different densities, (a) water loss process of soils without geotextile, (b) water loss process of soils with the density of the geotextile was 200 g/m2, (c) water loss process of soils with the density of the geotextile was 400 g/m2, (d) water loss process of soils with the density of the geotextile was 600 g/m2.

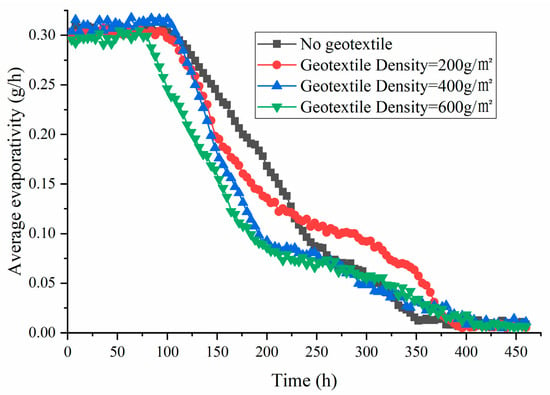

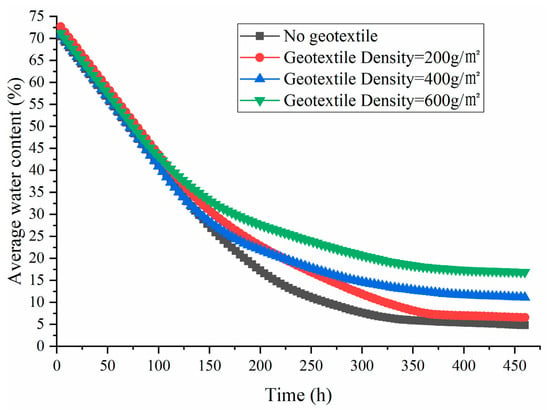

Figure 4 shows that for higher densities of geotextiles, the rate of water loss in each stage of the soil sample gradually decreased. When the density of the geotextile was 200, 400 and 600 g/m2, the average evaporation rate of soil in the deceleration stage (rapid deceleration stage, secondary deceleration stage and tertiary deceleration stage) was 0.127, 0.095 and 0.094 g/h, respectively. When the geotextile density was 0, 200, 400 and 600 g/m2, the deceleration stage accounted for 55.7%, 64.3%, 70.4% and 74.8% of the total evaporation time of water in the soil, respectively. After the soil deceleration stage, the water content in the soil was 5.88%, 7.03%, 11.45% and 17.16%, respectively. When the soil deceleration stage was over, the water continued to decline, entering the residual loss stage. When the geotextile density was 200, 400 and 600 g/m2 (Figure 5), the average residual water content descended by 34.8%, 127.1% and 247.0%, respectively, compared with soils without geotextiles. With increasing geotextile density, the water retention of soil becomes better, and a high-density geotextile is beneficial for the water retention of soil.

Figure 4.

Average evaporation rate of geotextile soils with different densities.

Figure 5.

Average water content of geotextile soils with different densities.

3.2. Influence of Geotextiles on Soil Cracking

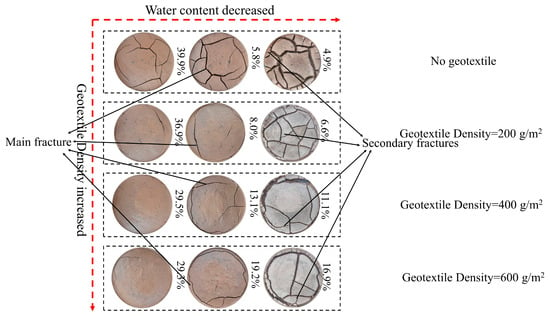

As shown in Figure 6, the crack propagation patterns of geotextiles with different densities were similar. With the loss of water from the soil, the soil gradually began to produce a main fracture. In the sample without geotextiles, the main fracture began to expand from a position near the center of the sample. After the addition of geotextiles, the main fracture was mainly produced in the periphery. Then, with the further loss of water, secondary fractures began to gradually expand around the main fracture. When the density of the geotextile was 200 g/m2, in samples without geotextiles, secondary cracks penetrated through the central surface of the sample. However, when the density of the geotextile was 400 and 600 g/m2, the cracks on the surface of the soil sample were largely reduced, and the cracks mainly developed around the sample, but did not penetrate the central surface. With an increase in the density of geotextiles, the water content of initial cracks in the soil samples decreased gradually, and the shape of soil cracks became simpler. When the geotextile density was 0, 200, 400 and 600 g/m2, the initial crack moisture content was 39.9%, 36.9%, 29.5% and 29.3%, respectively.

Figure 6.

Cracking process of different geotextile soils.

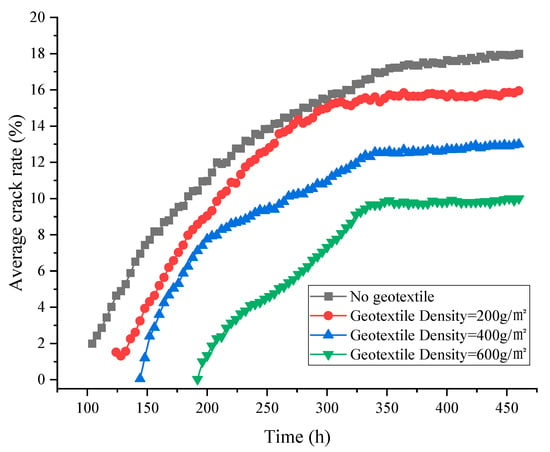

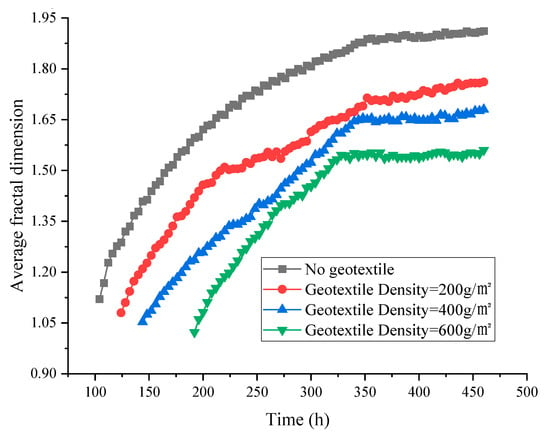

As shown in Figure 7, with the extension of water loss time, the crack development trend in soil samples with different density geotextiles was similar, and the crack rate of the soil gradually increases with the drying time. With water evaporation from the soil, the water content decreased gradually, and the propagation speed of soil cracks gradually slowed down. With increases in the density of the geotextile, the crack rate of the soil decreased. When the geotextile density was 200, 400 and 600 g/m2, the crack rate was reduced by 11.11%, 27.78% and 44.44%, respectively. Figure 8 shows that the FD of soil gradually increases with time. Increasing the density of the geotextile can decrease the soil cracks FD. When the geotextile density was 200, 400 and 600 g/m2, the crack FD was reduced by 7.88%, 12.12% and 18.39%, respectively. This shows that the randomness and complexity of cracks can be decreased with increases in geotextile density. At the same time, it indicates that water evaporation can cause soil cracking, and the better the water retention of the soil, the lower the initial crack water content, crack growth rate, final crack rate, disorder and complexity. The standard deviation of all the data is less than 0.5, which meets the data error requirement. The p value of water content and crack rate, water content and crack FD of geotextile soils with different densities is 0, which indicates that the relationship between water content and crack rate and the relationship between water content and crack FD are statistically significant.

Figure 7.

Changes in soil crack average crack rate with different geotextile densities over time.

Figure 8.

Changes in soil crack average FD with different geotextile densities over time.

4. Discussion

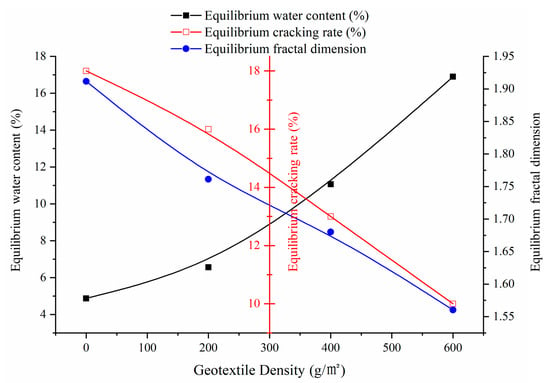

As shown in Figure 9, increasing the density of geotextiles can significantly increase the water retention of samples and reduce the crack rate and FD. With the increase in geotextile density, the fiber interleaving points and pore space of the geotextile itself also increase, improving the water storage capacity of soil geotextile and thus improving the water retention of the soil. At the same time, geotextiles can form a more compact covering layer and decrease the soil evaporation rate. The greater the density of the geotextile, the better the evaporation inhibition effect of the geotextile cover. The better the water retention of the soil, the better its cracking resistance. With increases in the density of the geotextiles, the crack rate and FD both decrease. With the increase in geotextile density from 200, 400 to 600 g/m2, the crack rate of the soil decreased by 11.1%, 27.8% and 44.4%, respectively. The FD of soil decreased by 7.9%, 12.1% and 18.4%, respectively. The R of the geotextile density and crack rate is −0.996, and the significance p value is 0.04. The R of geotextile density and FD is −0.994, and the significance p value is 0.06. In the geotextile–soil combination, the geotextiles closely interact with the soil, forming interface friction. The greater the density of geotextile, the greater the breaking strength, CBR bursting strength and tearing strength of the geotextile (Table 1), and the greater the friction and tensile strength formed by the soil–geotextile interface, which ultimately produces the reduction in soil crack rate and FD. The interaction structure of the soil–geotextile combination can raise the water retention of soil, and reduce the crack size, disorder and complexity of soil shrinkage cracking.

Figure 9.

Changes in residual water content and crack characteristics with geotextile density.

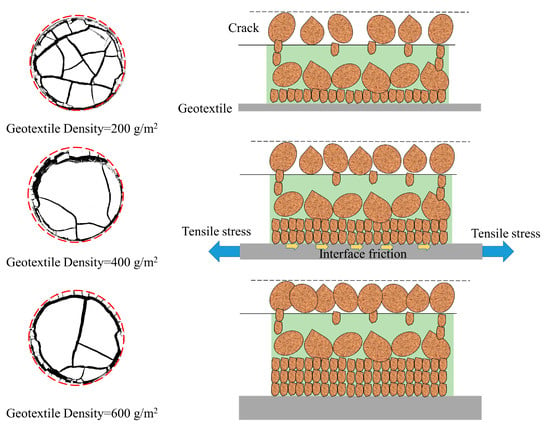

As can be seen in Figure 6, when the geotextile density is 200 g/m2, secondary fractures of the sample run through the central surface of the sample. When the density of the geotextile is 400 and 600 g/m2, the cracks on the surface of soil sample are reduced in a large area, and the cracks mainly develop around the surface, but do not penetrate the central surface. This is because under the action of water (Figure 10), a certain thickness of overhead layer composed of coarse soil particles forms above the soil layer. The fine particles of soil move through the overhead layer to the geotextile, and eventually form a fine-particle soil layer, and restrict the movement of adjacent soil particles. The higher the density of the geotextile, the more effective it is at preventing the movement of the fine-particle layer, and correspondingly, the thicker the fine particles formed above the geotextile. The higher the density of the geotextile, the thicker the fine particles deposited above it, the better the water retention of the soil, the lower the crack rate, and the simpler the crack shape.

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram of water loss process mechanisms of soil–geotextile composite model.

To further investigate the results of this study on the effects of different density geotextiles on the evaporative cracking characteristics of soil, we applied them in the field for a large area test. The results of the field tests are consistent with those of the laboratory tests, both showing that the higher the density of the geotextile, the better the water retention and the less the cracking degree of the soil. High-density geotextiles can reduce soil water evaporation and prevent soil cracking, and maintain soil structure and water balance by limiting the formation of surface cracks. However, their performance is affected by climate, soil type and other factors, and the performance is different []. In arid areas, the soil water evaporation rate is high and water loss is serious. Geotextiles can reduce the evaporation loss of water, can keep the soil moist to a certain extent, reduce soil cracking, and improve the water use efficiency of crops []. At extreme temperatures, however, geotextiles may lose some of their effectiveness through thermal expansion or aging []. In temperate climates, the evaporation rate of soil water is relatively low and the precipitation is moderate []. In this environment, the effect of geotextiles may not be as obvious as in dry climates, but they can still effectively protect the soil from excessive water loss, especially during winter soil freezing or summer drought []. However, in temperate zones, where precipitation is relatively high, geotextiles may reduce water penetration and cause groundwater levels to rise, thereby affecting soil permeability and root growth []. Soil type also has a significant influence on reducing evaporation and cracking of geotextiles, mainly reflected in soil permeability, particle distribution and stability []. Geotextiles in this sand can effectively prevent water evaporation, and by reducing water loss, keep the soil moist and reduce soil cracking. However, due to the strong drainage of sand, geotextiles may not be in good contact with the soil, which may lead to water accumulation, thus affecting groundwater flow. Clay soil has a strong water retention ability, but it easily forms surface crusts and cracks []. In this type of soil, the role of geotextiles is mainly to reduce water loss and prevent excessive water penetration to avoid water loss due to surface cracks. However, clay tends to adhere to geotextiles, which can lead to breakage or reduced permeability of the fabric.

In practical applications, although the use of geotextiles has significant advantages, it also faces some practical challenges, which need to be fully considered in the application process. The high cost of geotextiles, especially in large area applications, may become a factor restricting their widespread use. For areas with limited economic conditions or small-scale farms, the high cost of geotextiles may not make them economically viable. At the same time, long-term exposure to sunlight, weathering, rain and other environmental factors may result in geotextiles aging, degrading or suffering damage []. Especially in areas with strong ultraviolet light, the strength and durability of geotextiles will decrease with the passing of time, which may affect their long-term effectiveness []. During the installation of geotextiles, some practical difficulties may be encountered. For example, the laying and fixing of geotextiles becomes more difficult in complex terrain and in areas with uneven soil or harsh climate conditions. If the installation process is not handled properly, the geotextile may produce wrinkles or damage effects. The interaction of geotextiles with soil can also be a challenge, especially in areas where the soil structure is unstable or variable. Soil particles may penetrate into the geotextile, affecting the permeability of the fabric, resulting in a decline in long-term use. In general, geotextiles have significant advantages in reducing soil evaporation and preventing cracking, especially in arid areas and sandy soils. However, differences in actual effects under different climate and soil conditions need to be noted during use, while issues such as cost, degradation, installation and soil interactions need to be addressed in practical applications. By fully considering these factors, the use of geotextiles can be maximized and their actual value in agricultural irrigation, soil protection and ecological restoration can be enhanced.

Geotextiles are usually made of synthetic fibers, which degrade with difficulty in the natural environment and may persist in the soil for a long time []. Although geotextiles can be degraded under certain conditions (such as high temperature, ultraviolet irradiation, etc.), the degradation rate is slow, and harmful substances such as additives and plastic particles may be released during the degradation process, which may have a negative impact on the environment []. At present, the recycling and reuse of geotextiles remains a challenge. Due to the diversity of materials and the complexity of the environment in which they are used, the recycling rate of geotextiles is relatively low, and many traditional disposal methods may have adverse effects on the environment. Many used geotextiles end up in landfills, but they take up a lot of landfill space, and the decomposition process in landfills is slow. Some geotextiles can also be reused through mechanical recycling or chemical treatment, but the recycling process involves high energy consumption and high costs. The concept of green design can be promoted in the later stages of development, and their lasting impact on the environment can be effectively reduced by using bio-based, degradable materials to make geotextiles more environmentally friendly.

5. Conclusions

(1) As the density of geotextiles increases, the length of the moisture deceleration stage increases. When the geotextile density was 0, 200, 400 and 600 g/m2, the deceleration stage accounted for 55.7%, 64.3%, 70.4% and 74.8%, respectively, of the total evaporation time of water in the soil. With increasing geotextiles, the evaporation rate is characterized by five stages (constant loss stage, rapid deceleration stage, secondary deceleration stage, tertiary deceleration stage and residual loss stage), which differs from the pattern seen in normal soil.

(2) When the geotextile density was 200, 400 and 600 g/m2, the average residual water content of samples increased by 34.8%, 127.1% and 247.0%, respectively, compared with the soil without geotextiles. When the geotextile density was 200, 400 and 600 g/m2, the crack rate was reduced by 11.11%, 27.78% and 44.44%, respectively. The FD of cracks decreased with the increase in geotextile density. When the geotextile density was 200, 400 and 600 g/m2, the crack FD was reduced by 7.88%, 12.12% and 18.39%, respectively.

(3) Geotextiles themselves can provide fiber interleaving points and pore space, improve the water storage capacity of soil–geotextile combination, and thus improve the water retention capacity of soil. At the same time, geotextiles also form a relatively tight covering layer, reducing the evaporation rate of water on the soil surface. High-density geotextiles will form an overhead layer composed of coarse soil particles of a certain thickness above the soil layer, and the fine particles of soil will move to the geotextile layer through the overhead layer and eventually form a fine soil layer. This restricts the movement of adjacent soil particles, enhancing the water retention and crack resistance of the soil. The tensile strength of the geotextile itself also enhances the cracking resistance of the soil.

Author Contributions

B.Y.: Conceptualization, writing, revision. Y.Y.: Methodology, checking. C.Y.: Experiments. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge financial support from the Outstanding Young Talents Training Plan by Xuchang University under Grant No. 7, the Natural Science Foundation of Henan under Grant No. 222300420281 and the Key Scientific Research Project of Colleges and Universities in Henan Province (CN) under Grant No. 25B410001.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yang, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, C.; Li, Z. Effect of geotextiles with different masses per unit area on water loss and cracking under bottom water loss soil conditions. Geotext. Geomembr. 2024, 52, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Han, J.; Al-Naddaf, M.; Parsons, R.L.; Kakrasul, J.I. Field monitoring of wicking geotextile to reduce soil moisture under a concrete pavement subjected to precipitations and temperature variations. Geotext. Geomembr. 2022, 50, 1004–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, Q.; Pan, L. Review of organic mulching effects on soil and water loss. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2021, 67, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Han, Z.; Li, A.; Du, H. Research on the application of palm mat geotextiles for sand fixation in the hobq desert. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Han, J.; Zhang, X.; Guo, J. Laboratory tests to evaluate effectiveness of wicking geotextile in soil moisture reduction. Geotext. Geomembr. 2017, 45, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobiela-Mendrek, K.; Salachna, A.; Chmura, D.; Klama, H.; Broda, J. The influence of geotextiles stabilizing the soil on vegetation of post-excavation slopes and drainage ditches. J. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 20, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnudas, S.; Savenije, H.H.G.; Van der Zaag, P.; Anil, K.R. Coir geotextile for slope stabilization and cultivation—A case study in a highland region of Kerala, South India. Phys. Chem. Earth 2012, 47–48, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Liang, J.; Lin, H.; Wang, W.; Xiao, Y. Experimental Study on Influencing Factors Associated with a New Tunnel Waterproofing for Improved Impermeability. J. Test. Eval. 2024, 52, 344–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, A.F.; Fernandes-Filho, E.I.; Daher, M.; de Carvalho Gomes, L.; Cardoso, I.M.; Fernandes, R.B.A.; Schaefer, C.E. Microclimate and soil and water loss in shaded and unshaded agroforestry coffee systems. Agrofor. Syst. 2021, 95, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, H.; Kumar, R.; Dar, M.A.; Juyal, G.P.; Patra, S.; Dobhal, S.; Rathore, A.C.; Kaushal, R.; Mishra, P.K. Effect of geojute technique on density, diversity and carbon stock of plant species in landslide site of North West Himalaya. J. Mt. Sci. 2018, 15, 1961–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, R.; Miao, J.; Wang, J.; Jia, D. Effect of diatomite on soil evaporation characteristics. Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 80, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, J.; Kumar, R.; Kaushal, R.; Kar, S.; Mehta, H.; Chaturvedi, O. Soil conservation measures improve vegetation development and ecological processes in the Himalayan slopes. Trop. Ecol. 2023, 64, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.C.; Bezerra, J.F.R. Study of matric potential and geotextiles applied to degraded soil recovery, Uberlândia (MG), Brazil. Environ. Earth Sci. 2010, 60, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Li, D.; Yuan, S.; Jin, L. Role of biochar from corn straw in influencing crack propagation and evaporation in sodic soils. CATENA 2021, 204, 105457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, J.; Chabi-Olaye, A.; Kamonjo, C.; Jaramillo, A.; Vega, F.E.; Poehling, H.-M.; Borgemeister, C. Thermal tolerance of the coffee berry borer Hypothenemus hampei: Predictions of climate change impact on a tropical insect pest. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, C.; Strzepek, K.M.; Major, D.C.; Iglesias, A.; Yates, D.N.; McCluskey, A.; Hillel, D. Water resources for agriculture in a changing climate: International case studies. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2004, 14, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Q.; You, C. Biochar Effect on water evaporation and hydraulic conductivity in sandy soil. Pedosphere 2016, 26, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassanayake, S.; Mousa, A.; Fowmes, G.J.; Susilawati, S.; Zamara, K. Forecasting the moisture dynamics of a landfill capping system comprising different geosynthetics: A NARX neural network approach. Geotext. Geomembr. 2023, 51, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Tang, C.S.; Cheng, Q.; Zhu, C.; Yin, L.Y.; Shi, B. Drought-induced soil desiccation cracking behavior with consideration of basal friction and layer thickness. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR026948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tang, L.S.; Ye, Y.H.; Cheng, Z.H.; Zhou, Z.X. Effects of different chloride salts on granite residual soil: Properties and water–soil chemical interaction mechanisms. J. Soils Sediments 2023, 23, 1844–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Zhao, X.; Hu, M.; Yang, C.; Xie, G. Effect of salt content on the evaporation and cracking of soil from heritage structures. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 2021, 3213703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Tang, C.; Cheng, Q.; Xu, Q.; Inyang, H.; Lin, Z.; Shi, B. Investigation on desiccation cracking behavior of clayey soils with a perspective of fracture mechanics: A review. J. Soils Sediments 2021, 22, 859–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Zhu, C.; Leng, T.; Shi, B.; Cheng, Q.; Zeng, H. Three-dimensional characterization of desiccation cracking behavior of compacted clayey soil using X-ray computed tomography. Eng. Geol. 2019, 255, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombi, T.; Kirchgessner, N.; Iseskog, D.; Alexandersson, S.; Larsbo, M.; Keller, T. A time-lapse imaging platform for quantification of soil crack development due to simulated root water uptake. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 205, 104769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Liang, J.; Huang, X.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Yang, G.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, J.; Wang, H.; Yuan, P. Eco-efficient recycling of engineering muck for manufacturing low-carbon geopolymers assessed through LCA: Exploring the impact of synthesis conditions on performance. Acta Geotech. 2024, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Chen, W.; Li, Z.; Zhao, J.; Luo, Q.; Chen, W.; Chen, T. Sustainability of the polymer SH reinforced recycled granite residual soil: Properties, physicochemical mechanism, and applications. J. Soils Sediments 2023, 23, 246–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Xing, X.; Fu, W.; Ma, X. Performances of evaporation and desiccation cracking characteristics for attapulgite soils. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 2503–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Fan, S. Geometric and fractal analysis of dynamic cracking patterns subjected to wetting-drying cycles. Soil Tillage Res. 2017, 170, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappan, S.; Kamon, M.; Ali, F.H.; Katsumi, T.; Akai, T.; Inui, T.; Nishimura, M. Performances of landfill liners under dry and wet conditions. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2011, 29, 881–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, Z.C.; Bouazza, A.; Gates, W.P. Influence of polymer enhancement on water uptake, retention and barrier performance of geosynthetic clay liners. Geotext. Geomembr. 2022, 50, 590–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Martínez, J.C.; García, E.F.; Vega-Posada, C.A. Effects of hydro-mechanical material parameters on the capillary barrier of reinforced embankments. Soils Found. 2022, 62, 101090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahardjo, H.; Kim, Y.; Gofar, N.; Leong, E.C.; Wang, C.L.; Wong, J.L.H. Field instrumentations and monitoring of GeoBarrier System for steep slope protection. Transp. Geotech. 2018, 16, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, Y.; Zhou, X.; Tang, S.; Lu, Y.; Li, W.; et al. Research on the aging mechanism of polypropylene nonwoven geotextiles under simulated heavy metal aging scenarios. Geotext. Geomembr. 2024, 52, 1240–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Ding, G.; Wang, H. Dynamic development law of expansive soil cracks under environmental influence. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 22, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawal, A.; Anand, S.; Shah, T. Optimization of parameters for the production of needlepunched nonwoven geotextiles. J. Ind. Text. 2008, 37, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Shi, B.; Liu, C.; Zhao, L.; Wang, B. Influencing factors of geometrical structure of surface shrinkage cracks in clayey soils. Eng. Geol. 2008, 101, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).