Balancing Heritage and Modernity: A Hierarchical Adaptive Approach in Rome’s Cultural Sports Urban Renewal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Identification of “Adaptive” Issues

3.1.1. Specific Issue Analysis of Cultural–Sports Public Service Facilities

- 1.

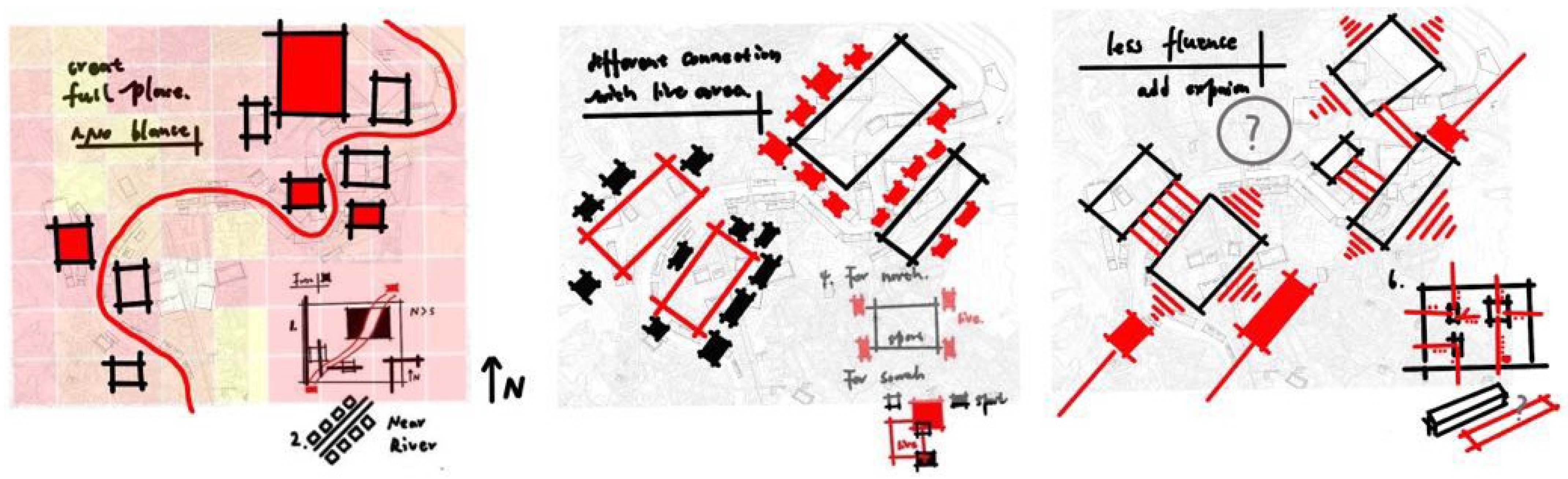

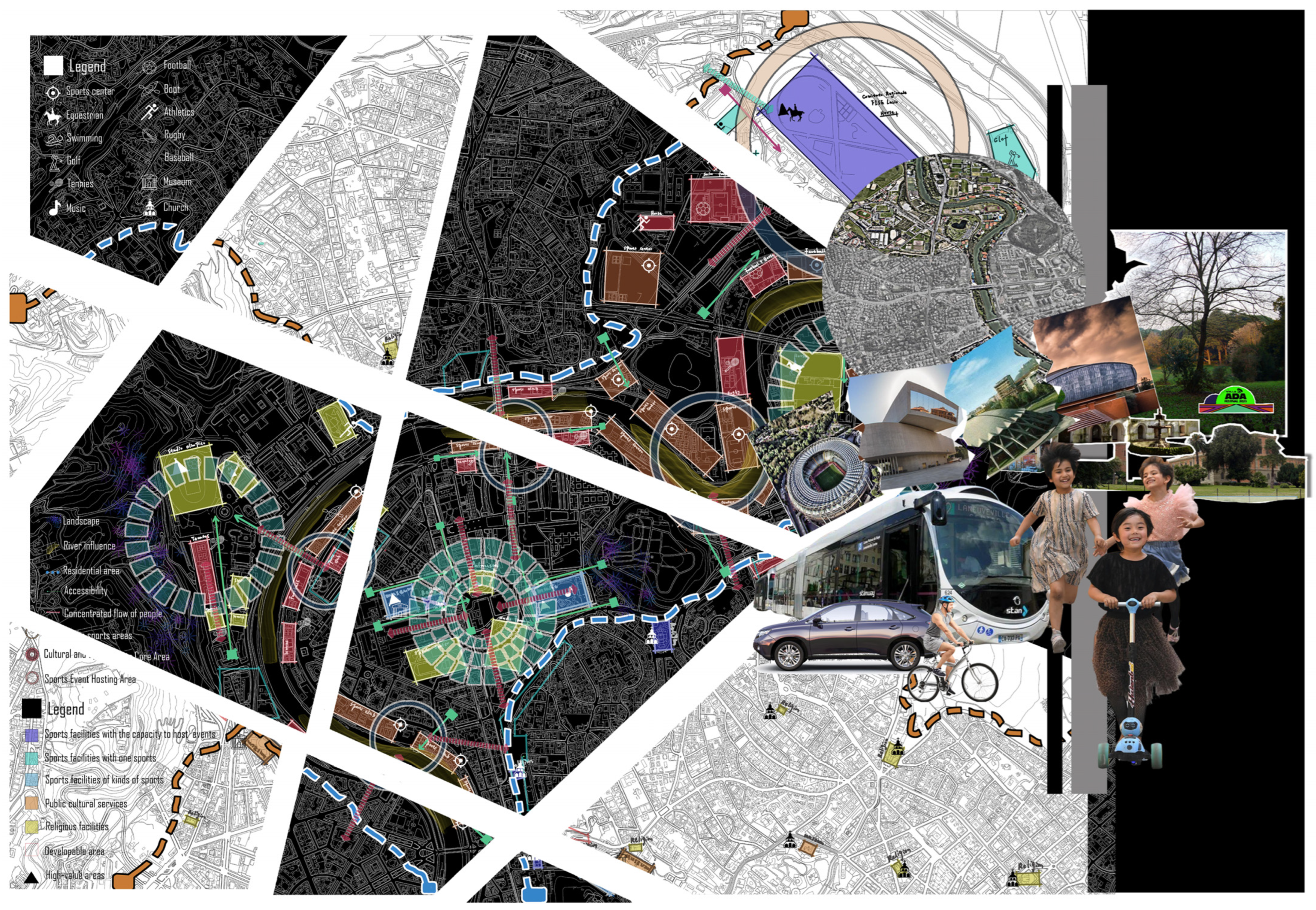

- Northern sectors exhibit significantly higher facility density compared to southern areas, with resident–facility relationships transitioning from facilities enveloped by residential clusters in the north to residential clusters surrounded by facilities in the south (as shown in Figure 3).

- 2.

- Cultural–sports facilities lack adjacent supporting public service amenities. Specifically, these activity hubs fail to incorporate secondary functional zones for visitor flow utilization, thereby diminishing activity richness in surrounding areas (as shown in Figure 3).

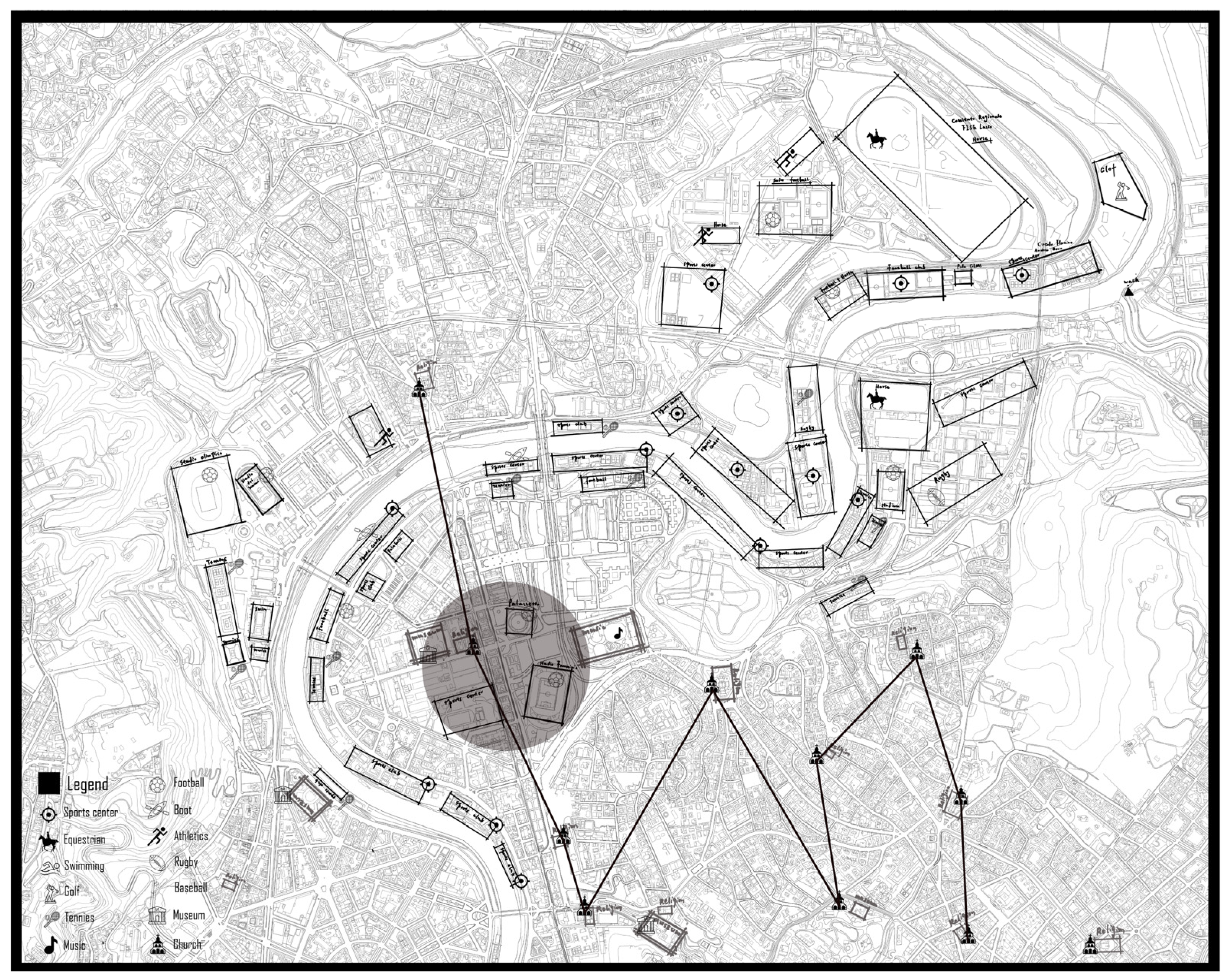

- Functional redundancy among homogeneous facilities, with clusters of same-category sports facilities (e.g., tennis courts and soccer fields) concentrated in specific zones, resulting in uninspiring activity offerings and diminished land utilization efficiency (as shown in Figure 4).

- While most cultural–sports facilities demonstrate good transportation accessibility, adjacent traffic flows exhibit chaotic mixed vehicular, non-motorized, and pedestrian circulation, posing safety risks (as shown in Figure 4).

- High-quality landscape parklands adjacent to cultural–sports facilities remain poorly interconnected (as shown in Figure 4).

- Five undeveloped plots within the site demonstrate strong connectivity with both cultural–sports facilities and residential clusters, presenting potential as linking zones (as shown in Figure 6).

- Regarding sports facility typology, centralized sports complexes (accommodating multiple activities) and single-function sports facilities exhibit clustering phenomenon, creating functional overlap in potentially compatible areas (as shown in Figure 6).

- Cultural buildings (e.g., concert halls and museums) concentrate disproportionately in southern sectors, resulting in extended travel distances for northern residents, while dense sports facilities lack complementary cultural diversity (as shown in Figure 6).

- Regarding cultural–sports facility legibility, major public facilities exhibit limited visual permeability and lack distinguishable urban signage differentiating general areas from cultural–sports activity hotspots, resulting in deficient spatial atmosphere (as shown in Figure 7).

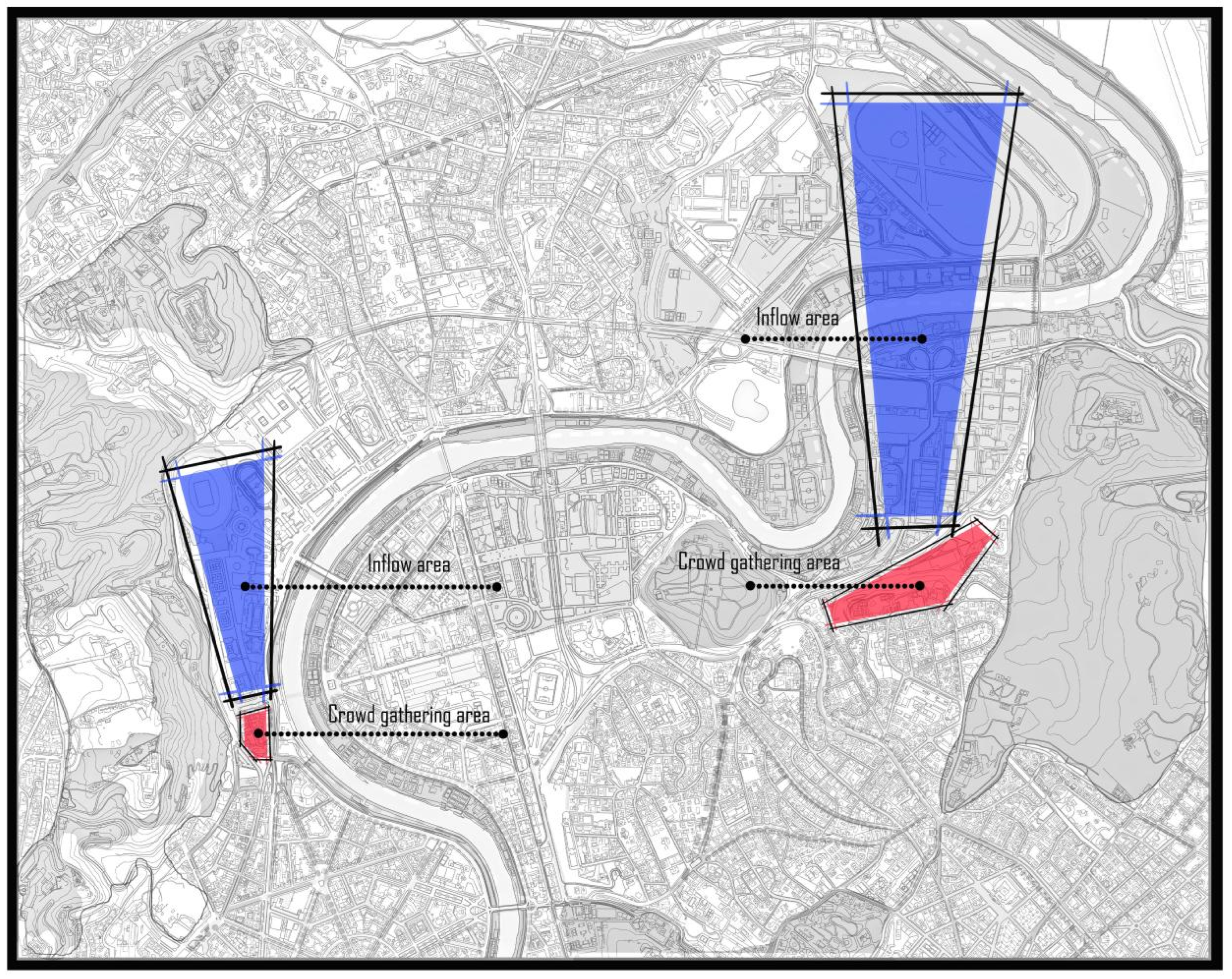

- Large-scale event venues (excluding the Olympic Stadium) lack adjacent expansive areas for crowd management and vehicle accommodation (as shown in Figure 7).

- Proximate cultural landmarks such as the Rome Auditorium and Palazzo dello Sport fail to generate regional synergy effects, remaining paradoxically concealed within the urban fabric despite their public nature (as shown in Figure 7).

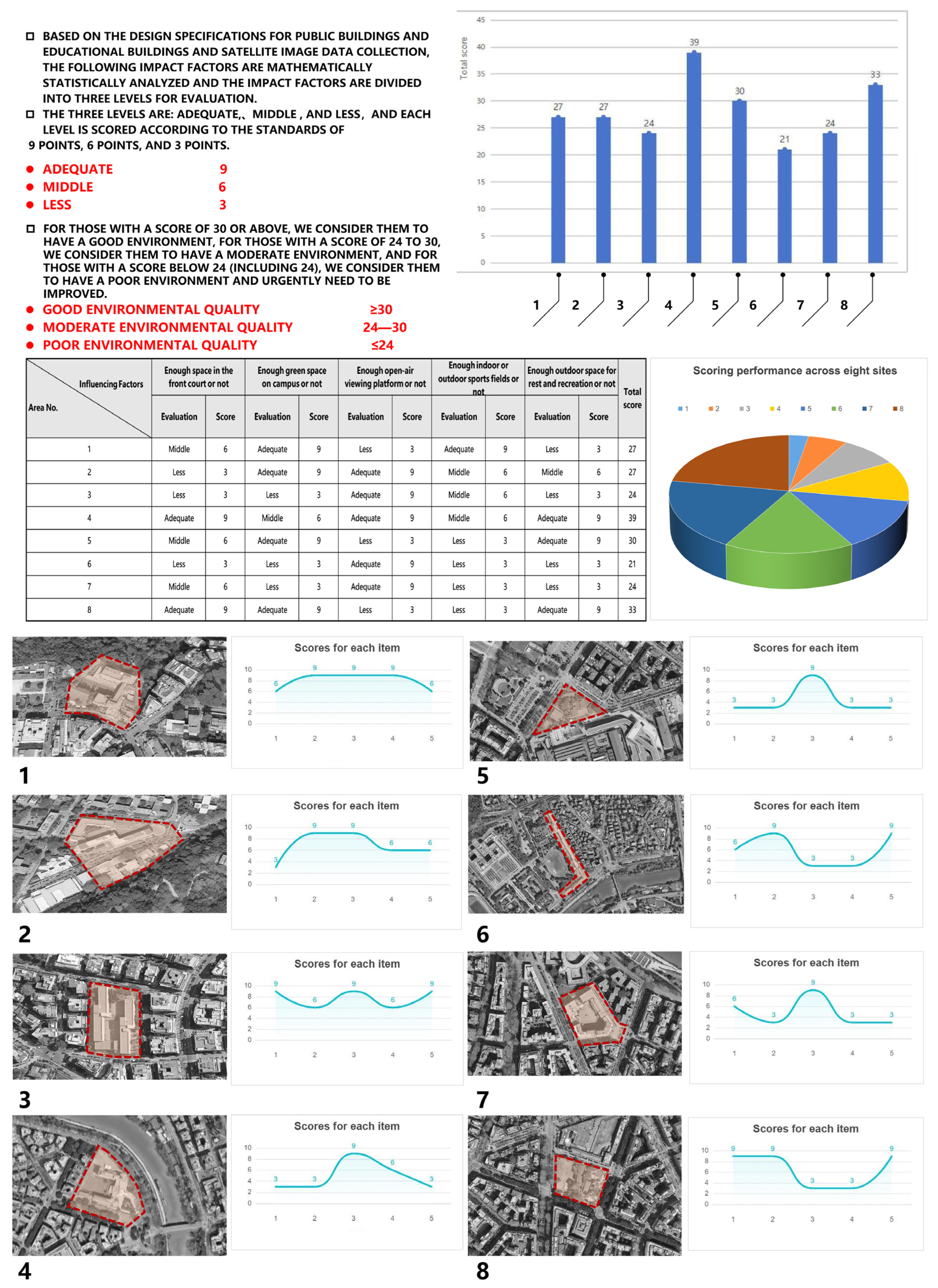

3.1.2. Visualized Data Analysis of Cultural–Sports Public Service Facilities

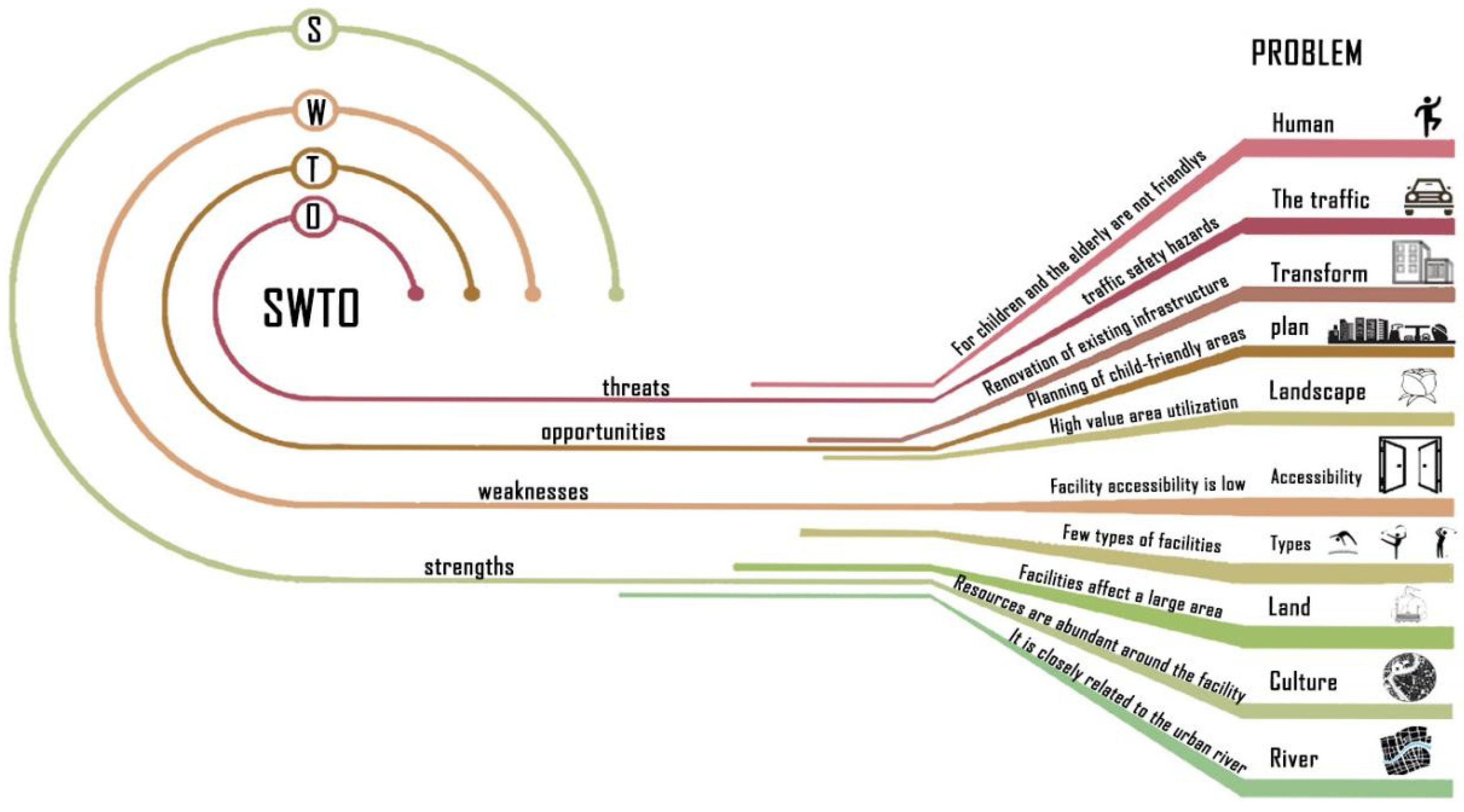

3.1.3. Chart-Based SWOT Analysis Summary

- User Group Coverage: Cultural–sports infrastructure inadequately serves diverse demographics, particularly lacking child-friendly adaptations at urban scales.

- Transportation Safety: While facility accessibility remains satisfactory, mixed pedestrian–vehicular circulation patterns create safety hazards.

- Spatial Connectivity: Weak integration with surrounding areas, especially residential clusters, presents substantial improvement opportunities.

3.2. Establishment of the “Hierarchical Design” System

3.2.1. Definition of the “Hierarchical” Design Strategy

3.2.2. Fundamental Formal Principles of the “Hierarchical” Design Strategy

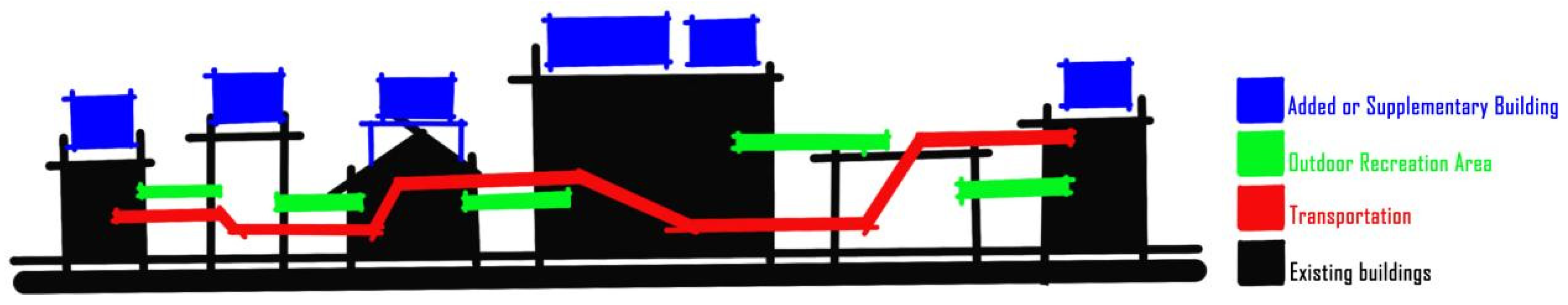

3.2.3. Architectural–Urban Intervention Principles of the “Hierarchical” Design Strategy

- Historically/Culturally Significant Structures: Adhere to the “non-intervention unless necessary” principle, preserving formal functionality and visual integrity.

- High-Use Important Buildings: Implement “semi-intervention” principles requiring integration between existing sites, rooftops, and circulation systems with new additions to ensure operational coherence.

- Generic Mass-Produced Buildings: Apply “full-intervention” principles where all functions and facilities serve the new system, enhancing systemic completeness.

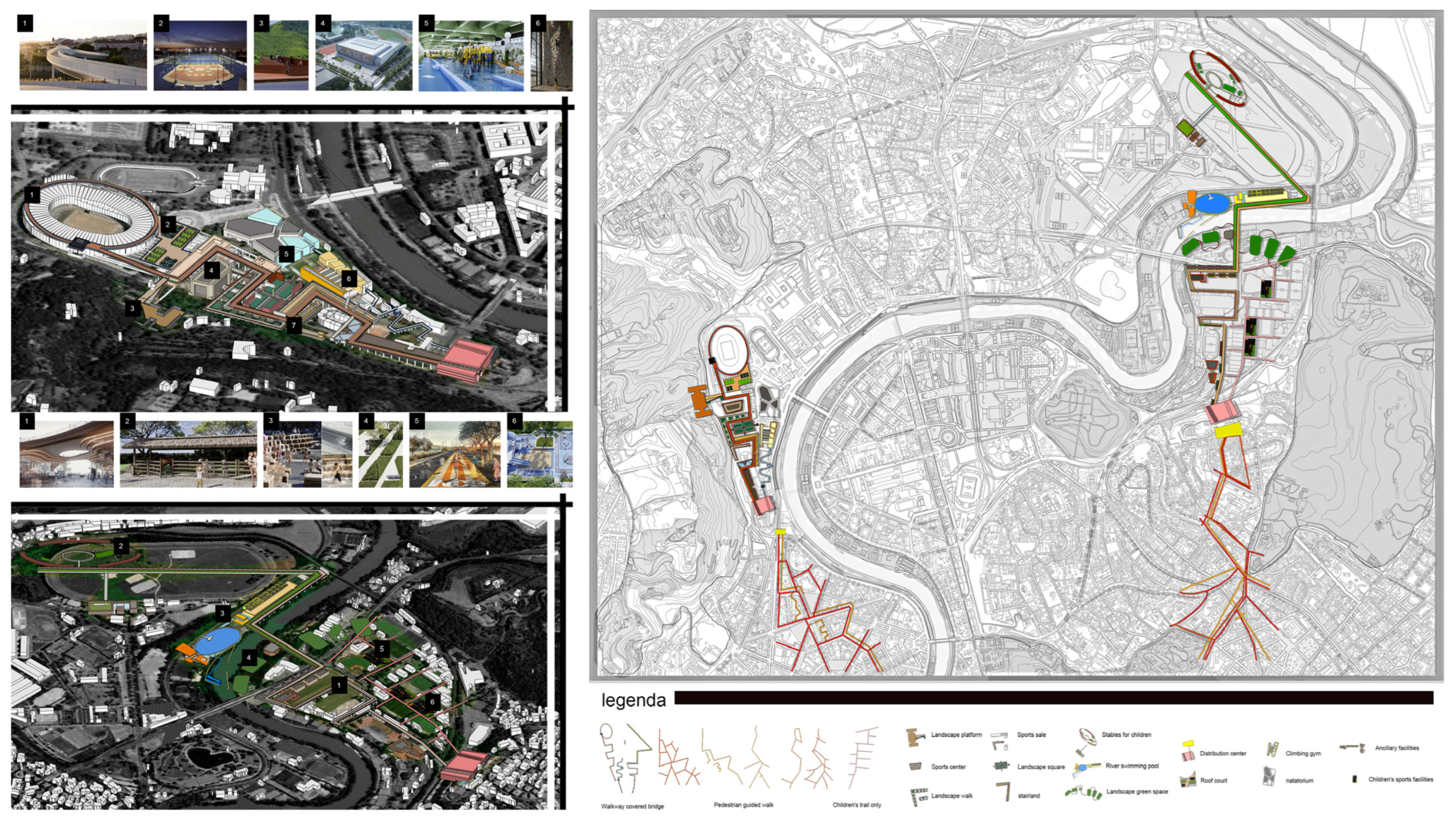

3.3. “Hierarchical” Adaptive Experimentation

3.3.1. Issue Synthesis

- Demographic Coverage: Facilities demonstrate child-unfriendliness, lacking dedicated sports and cultural amenities for children.

- Supporting Infrastructure: Chaotic mixed pedestrian–vehicular circulation patterns create safety hazards.

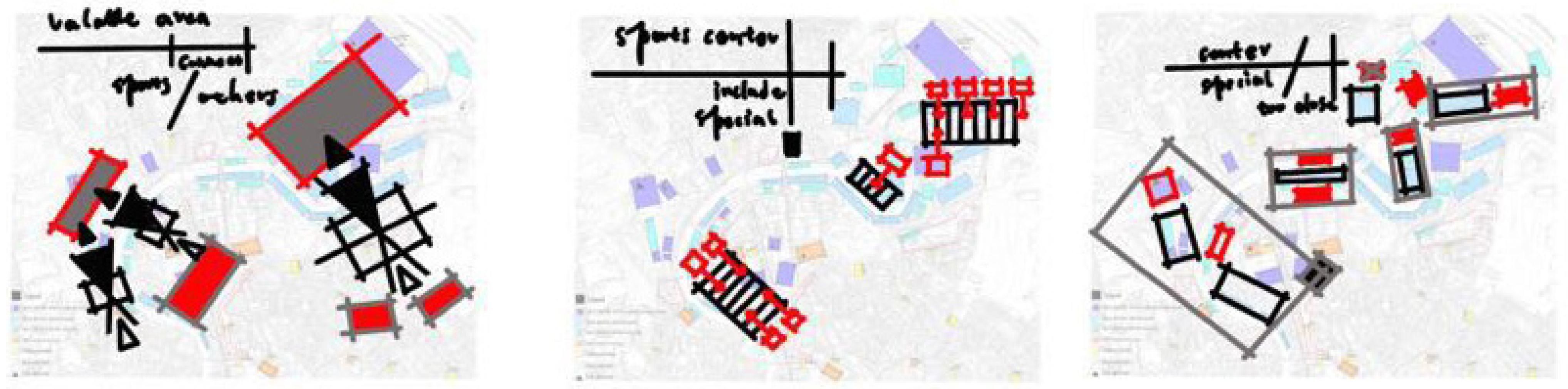

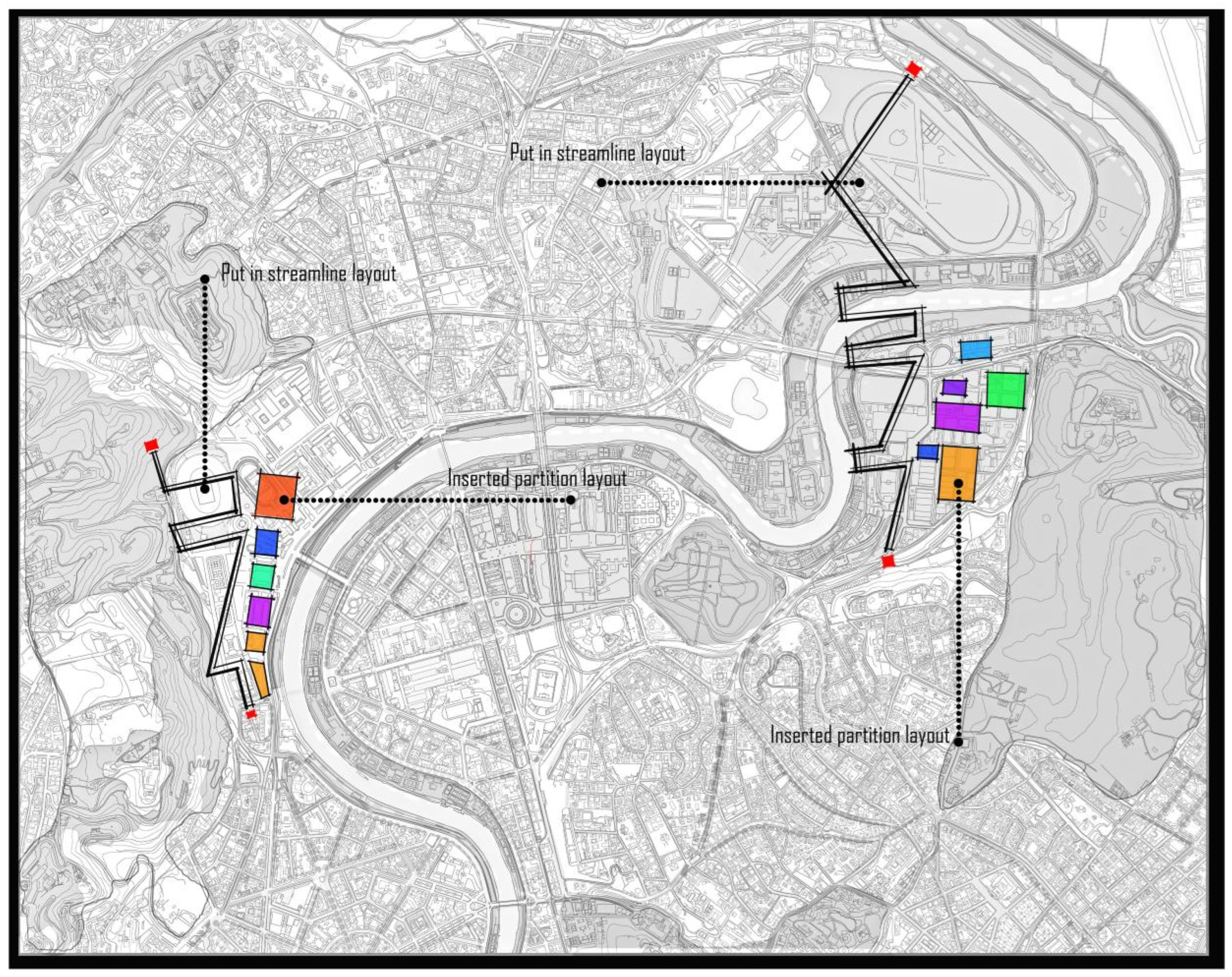

- Urban Connectivity: Weak linkages between cultural–sports facilities and adjacent zones, particularly limited integration with extensive residential areas (as shown in Figure 14).

3.3.2. Design Strategy Formulation

- ①

- Selection of Supplementation/Reconfiguration Zones

- ②

- Key Building Selection and Intervention Feasibility Study

- ③

- Integration of Supplementary and New Functions

- ①

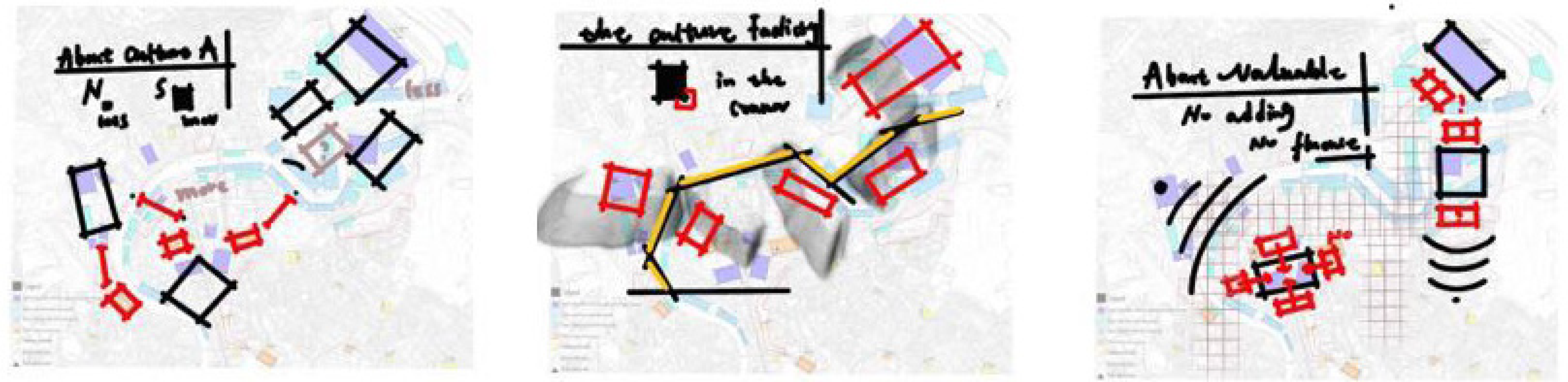

- Pedestrian Pathway Planning and Outdoor Space Configuration for Semi-Intervention Zones

- ②

- Pedestrian Pathway Planning and Outdoor Space Configuration for Full-Intervention Zones

- ①

- Residential Zone Selection

- ②

- Intervention Facility Selection

4. Discussion

4.1. Significance of Research Findings

4.1.1. Functional Optimization

4.1.2. Enhanced Spatial Vitality

4.1.3. Regional Integration

4.2. Interpretation of Results from Previous Research and Working Assumptions

- Jacobs’ Theory of Urban Vitality (Jacobs, 1961 [19]) emphasizes the importance of diversity and functionality in urban spaces. This study’s functional overlay and spatial integration strategies align closely with Jacobs’ principles.

- Social Logic of Space (Hillier & Hanson, 1984 [20]) highlights the critical role of connectivity and accessibility in urban vitality. In the study, the design of independent pedestrian systems and three-dimensional transportation networks validates the practical application of this theory.

4.3. Broader Context and Implications of the Findings

4.3.1. Balancing Heritage and Modernization

4.3.2. Application of Systematic Thinking

4.3.3. Child-Friendly Urban Design

4.4. Future Research Directions and Outlook

4.4.1. Development of Quantitative Evaluation Systems

4.4.2. Optimization of Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration Mechanisms

4.4.3. Integration of New Technologies

4.4.4. Cross-Cultural Applicability Studies

4.4.5. Future Outlook—Toward Resilient and Intelligent Urban Renewal

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marcus, L.; Colding, J. Placing urban renewal in the context of the resilience adaptive cycle. Land 2023, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Feng, G. Multi-Dimensional Organic Conservation of Historical Neighborhood Buildings; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; He, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, M. Morphological resilience evaluation research on the conservation and renewal of historic districts. In Frontiers of Architectural Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Karaman, O. Dispossession Through Urban Renewal in Istanbul. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, B. Planning’s End? Urban Renewal in New Haven and Yale School. J. Urban Hist. 2021, 37, 400–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulles, K.; Conti, I.A.; de Kleijn, M.B.; Kusters, B.; Rous, T.; Havinga, L.C.; Kaya, D.I. Emerging strategies for regeneration of historic urban sites: A systematic literature review. City Cult. Soc. 2023, 35, 100539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Zhao, Y. Perception and Evaluation of Cultural Heritage Value in Historic Urban Public Parks. Buildings 2025, 15, 3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Qiu, B.; Wu, Y. Exploration of urban community renewal governance for adaptive improvement. Habitat Int. 2024, 144, 102999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou, T.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, B. Vernacular ecological construction: Spatial-landscape in Huizhou courtyard dwellings. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2025, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artés, J.; Wadel, G.; Martí, N. Vertical Extension and Improving of Existing Buildings. Open Constr. Build. Technol. J. 2017, 11, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Gong, K. Urban-to-Rural MiTanggration and Vernacular Village Revitalization. Buildings 2025, 15, 3113. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, S. Function Orientation and Governance Mechanisms in Community Renewal. Soc. Secur. Adm. Manag. 2023, 4, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ciolli, M. Adaptation and Radicalization of Hayek’s Thought in Argentina. Lat. Am. 2024, 68, 190–218. [Google Scholar]

- Zhaoteng, J.; Kai, G. Spatial–Lifestyle Interventions on Architecture. Ph.D. Dissertation, ProQuest, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Maculan, L.S.; Dal Moro, L. Strategies for inclusive urban renewal. In Sustainable Cities and Communities; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Davoudi, S.; Shaw, K.; Haider, L.J.; Quinlan, A.E. Resilience as a Useful Concept for Climate Change Adaptation? Plan. Theory Pract. 2021, 13, 324–328. [Google Scholar]

- Duffield, M. Post-humanitarianism: Governing Precarity Through Adaptive Design. J. Humanit. Aff. 2019, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabst, A. Postliberal Politics: The Coming Era of Renewal; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961; 458p. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984; 281p. [Google Scholar]

- Beatley, T. Green Urbanism: Learning from European Cities; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; 492p. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, M.R.; Stren, R.; Cohen, B.; Reed, H.E. (Eds.) Cities Transformed: Demographic Change and Its Implications in the Developing World; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; 554p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tang, K.; Figliola, A. Balancing Heritage and Modernity: A Hierarchical Adaptive Approach in Rome’s Cultural Sports Urban Renewal. Buildings 2025, 15, 4570. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244570

Tang K, Figliola A. Balancing Heritage and Modernity: A Hierarchical Adaptive Approach in Rome’s Cultural Sports Urban Renewal. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4570. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244570

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Kai, and Angelo Figliola. 2025. "Balancing Heritage and Modernity: A Hierarchical Adaptive Approach in Rome’s Cultural Sports Urban Renewal" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4570. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244570

APA StyleTang, K., & Figliola, A. (2025). Balancing Heritage and Modernity: A Hierarchical Adaptive Approach in Rome’s Cultural Sports Urban Renewal. Buildings, 15(24), 4570. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244570