Balancing Thermal Comfort and Energy Efficiency of a Public Building Through Adaptive Setpoint Temperature

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview

1.2. Research Gap

1.3. Objectives

2. Methods

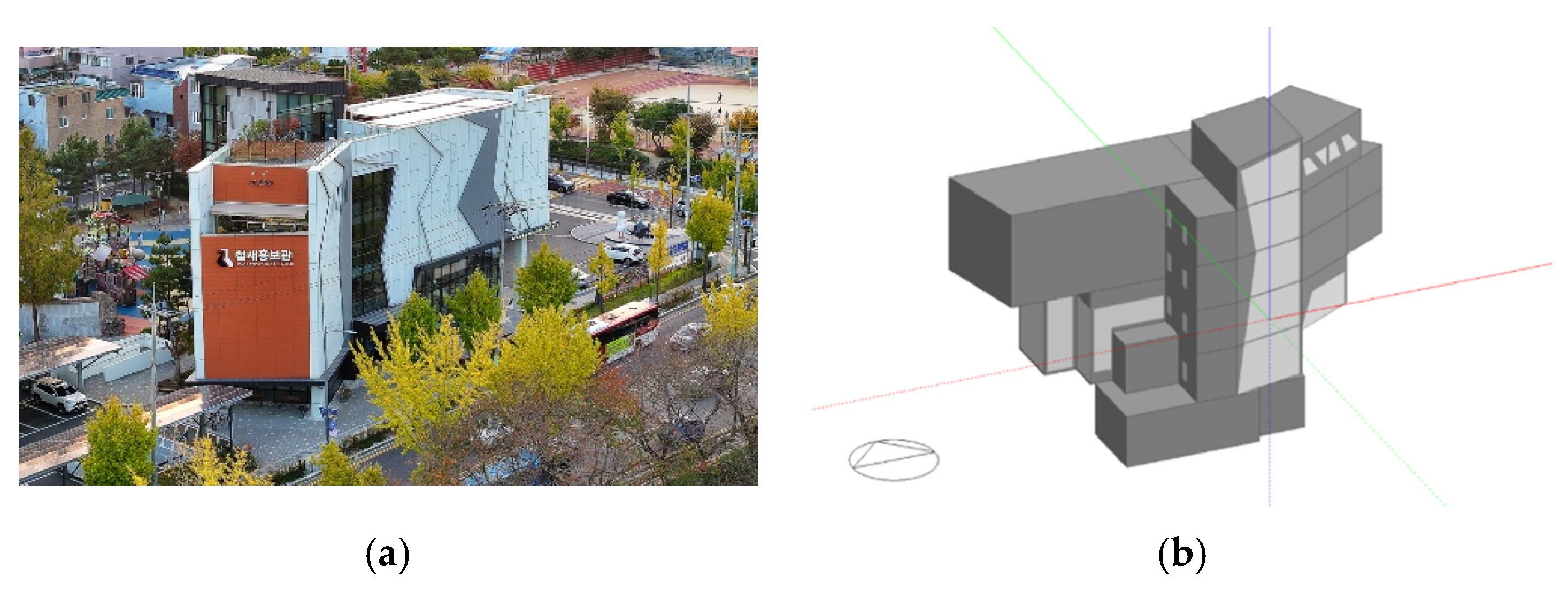

2.1. Case Study Building

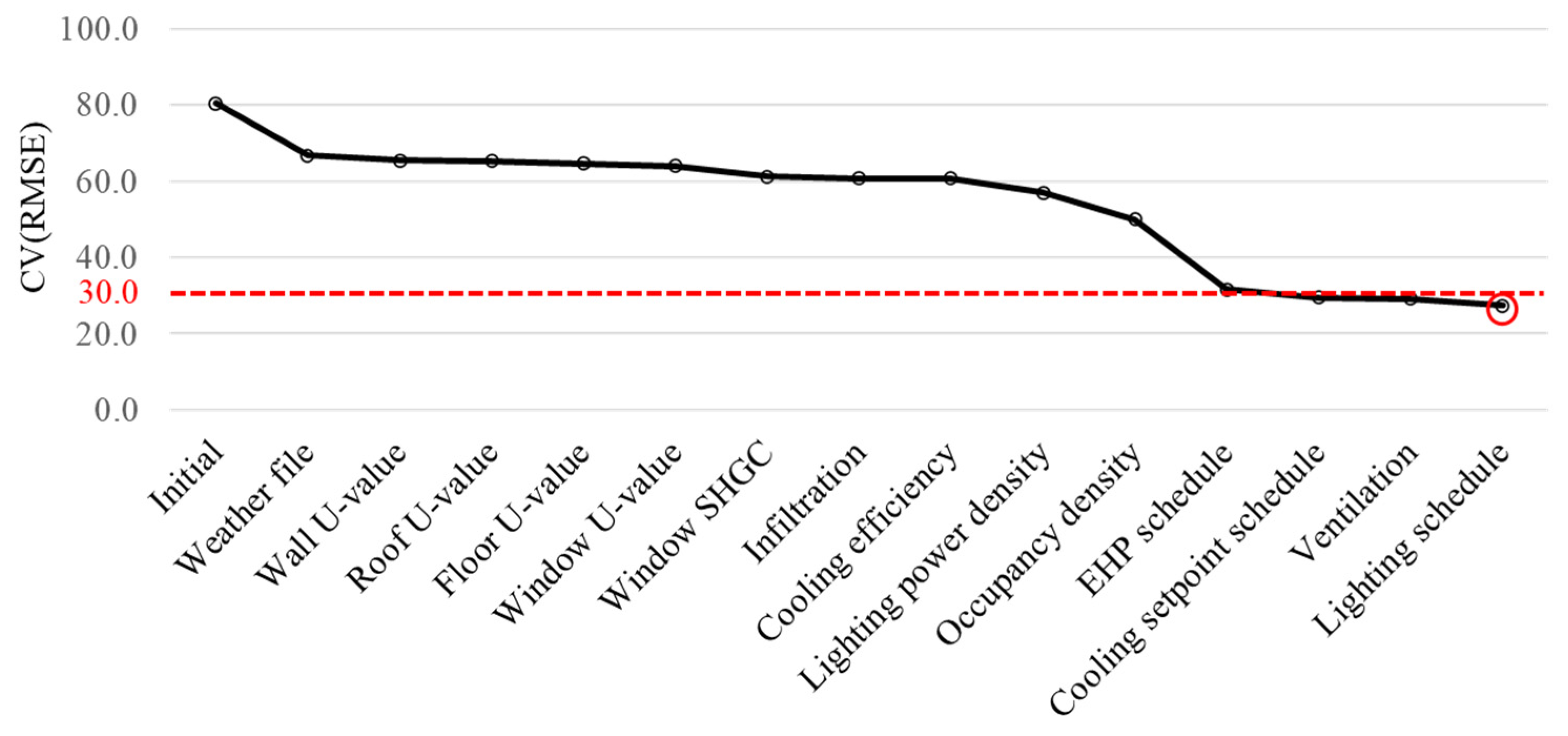

2.2. Energy Simulation Modeling and Calibration

- (1)

- Weather file: Instead of using Typical Meteorological Year (TMY) data, actual hourly weather data for 2022 (Actual Meteorological Year, AMY) was utilized in the simulation. The local weather data was obtained from the Korea Meteorological Administration.

- (2)

- Building envelope and HVAC systems: Thermal performance parameters with high uncertainty were adjusted within reasonable bounds. This included U-values for the external wall, roof, floor, and windows, as well as SHGC, infiltration rate, and COP of the HVAC system. To account for potential thermal bridging and insulation deterioration over time, U-values were increased by approximately 3 to 30% relative to design specifications in the construction documents. Infiltration rates were modified to match observed nighttime load patterns, and cooling COP values were adjusted to reflect part-load degradation.

- (3)

- Internal loads and operation schedule: Lighting and plug loads were calibrated using sub-metered electrical data. Occupancy-related internal gains were redefined based on visitor statistics and operation schedules, as the building is publicly accessible only during specific hours and days. Actual occupancy was found to be lower than initially assumed, particularly in exhibition zones, and internal gains were reduced accordingly. HVAC operation schedules were synchronized with BEMS logs, which indicated typical system operation from 9:00 AM to 6:00 PM, with nighttime setbacks and closure on Mondays.

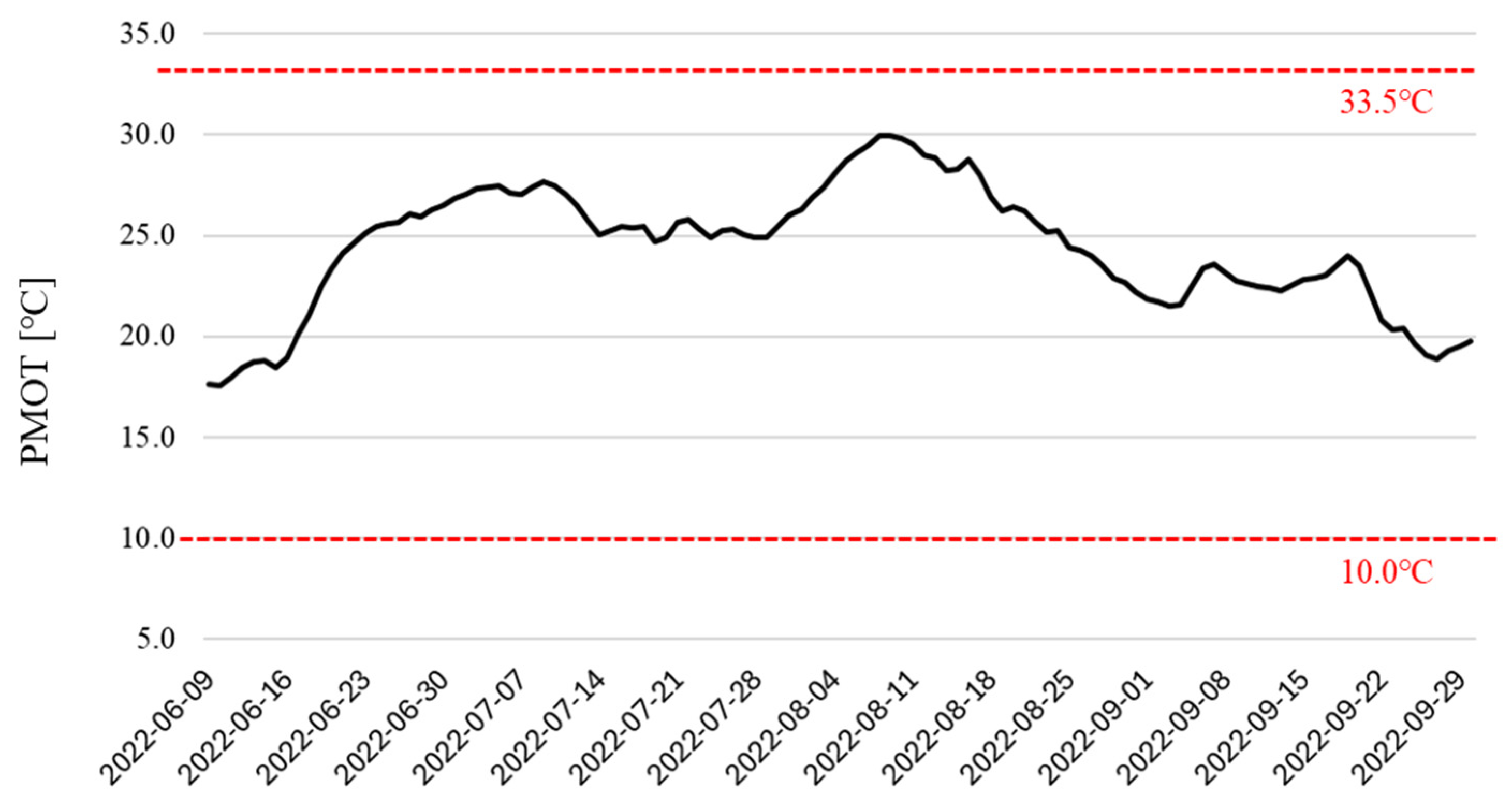

2.3. Adaptive Setpoint Control Strategy

3. Results and Discussion

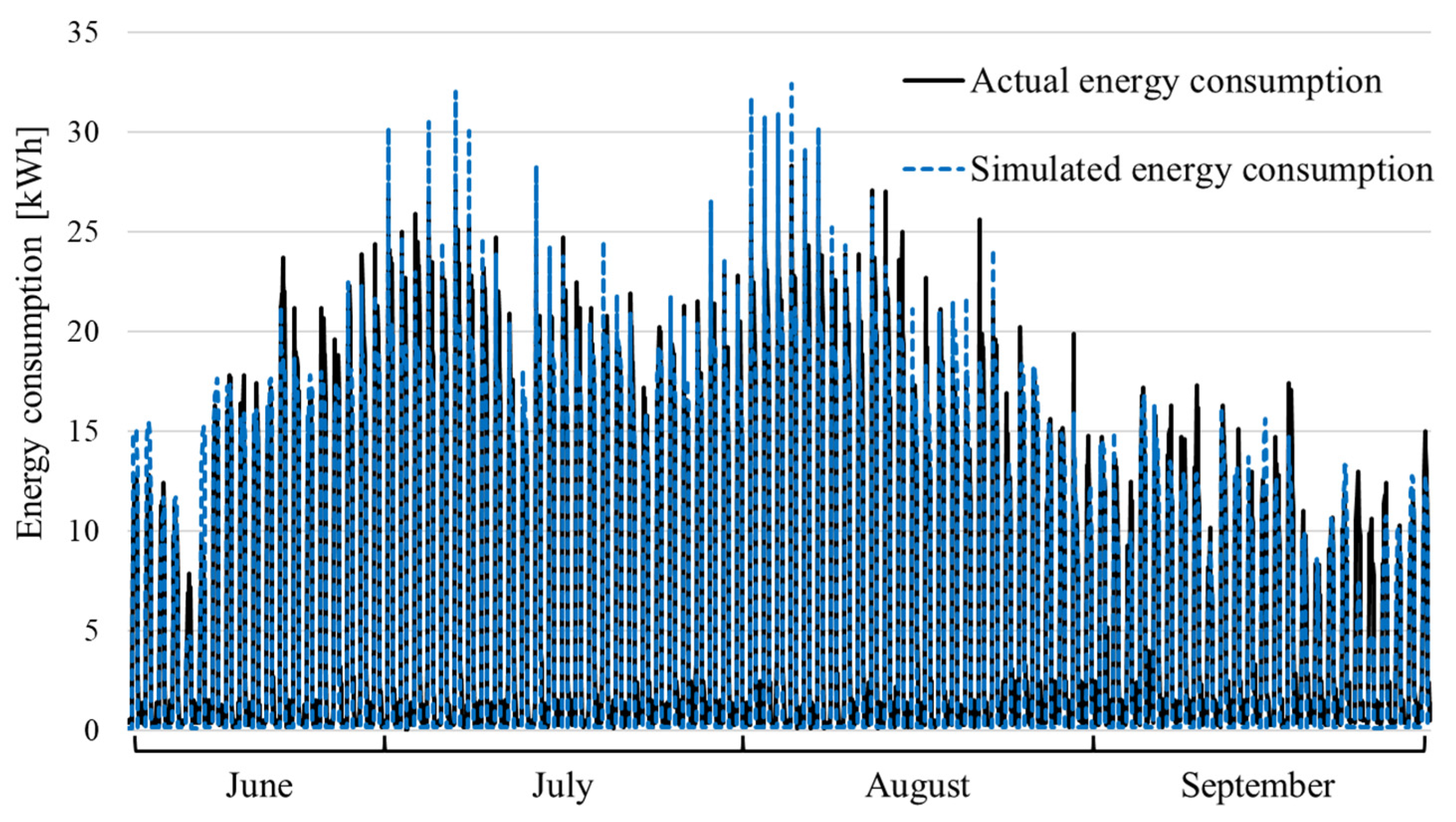

3.1. Calibrated Simulation Model

3.2. Prediction of Energy-Saving Potential Through Adaptive Setpoint Temperature Control

4. In Situ Performance Evaluation

4.1. Cooling Energy Reduction

4.2. Occupant Thermal Comfort

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Using the building envelope and system operation data, the simulation model was developed, yielding a CV(RMSE) of 80.5% and an MBE of −14.8%. The model was then calibrated to improve accuracy, resulting in a CV(RMSE) of 27.3% and an MBE of 8.2%, meeting the reliability criteria specified in ASHRAE Guideline 14.

- (2)

- To determine the adaptive setpoint temperature, daily mean outdoor temperatures from June to September 2022 were collected and used to calculate the PMOT, which met the applicability range of the adaptive thermal comfort model specified in ASHRAE Standard 55. The corresponding comfort temperature was then used as the adaptive setpoint temperature.

- (3)

- The adaptive setpoint temperature was applied to the simulation model on a daily basis, and the cooling energy consumption from June to September 2022 was compared with that of a base model with a fixed setpoint temperature. Results showed that the total cooling energy consumption during the period was 13,895 kWh for the fixed setpoint and 12,650 kWh for the adaptive setpoint, corresponding to an overall energy saving of 9.0%. Monthly analysis revealed savings of 12.0%, 11.8%, and 12.4% in July, August, and September, respectively, with no significant savings in June.

- (4)

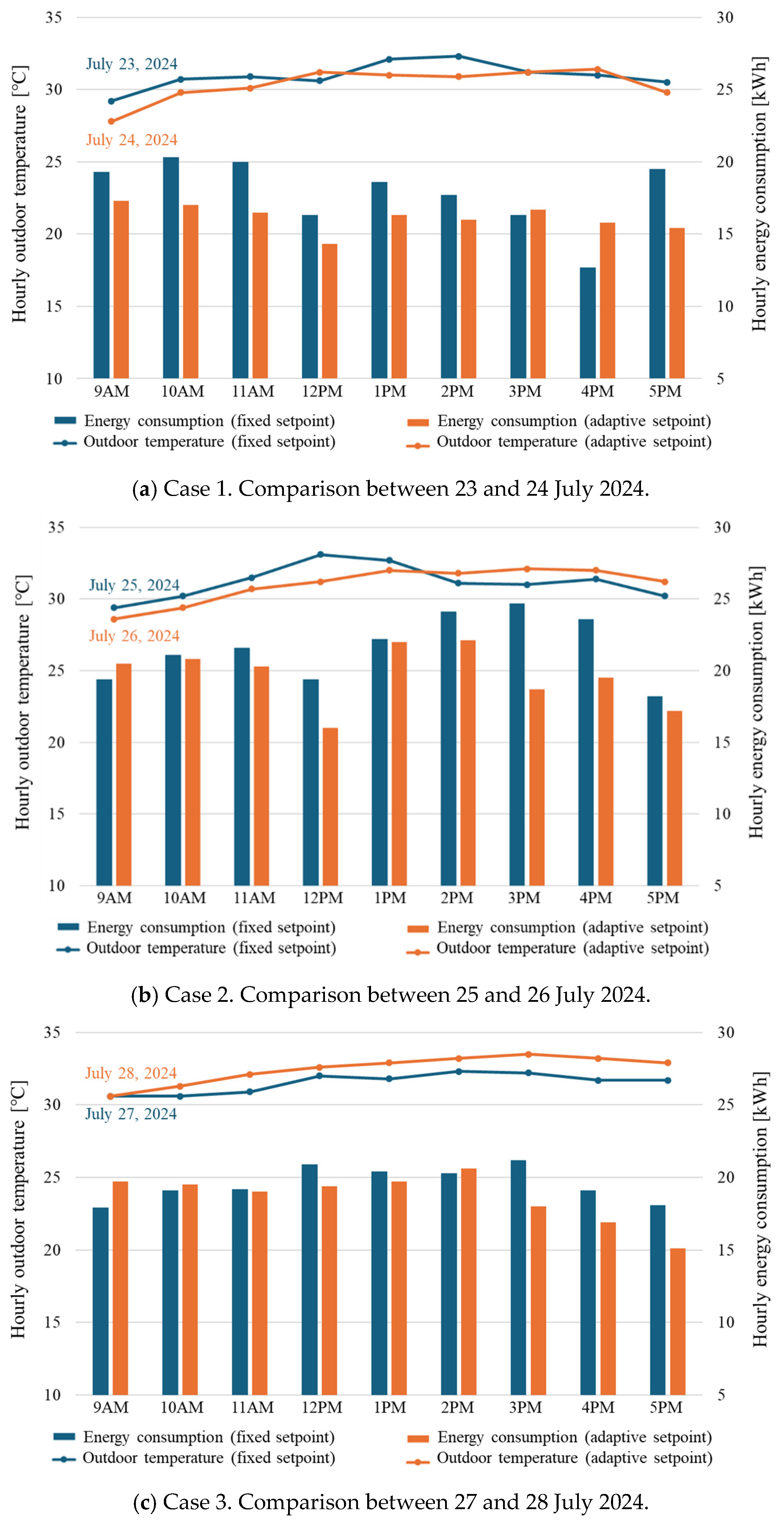

- From 23 to 28 July 2024, a six-day in situ field experiment was conducted in which the adaptive and fixed setpoints were alternated on a daily basis. The fixed setpoint was applied on 23, 25, and 27 July, and the adaptive setpoint on 24, 26, and 28 July. When comparing days with similar outdoor temperature conditions, the adaptive setpoint reduced daily energy consumption by 4.7–9.6% compared to the fixed setpoint. Over the entire experiment, total energy consumption was 531.2 kWh for fixed setpoint days and 490.3 kWh for adaptive setpoint days, yielding an overall savings of 7.7%.

- (5)

- The simulated and measured energy savings rates were 9.0% and 7.7%, respectively. The simulation covered a four-month cooling period in 2022, whereas the field experiment was carried out for a six-day period in July 2024. Differences in study duration and conditions, including outdoor temperature, indoor environment, and building operation patterns between the two years, likely contributed to the variation in results. Nonetheless, the energy savings from both approaches were found to be of similar magnitude.

- (6)

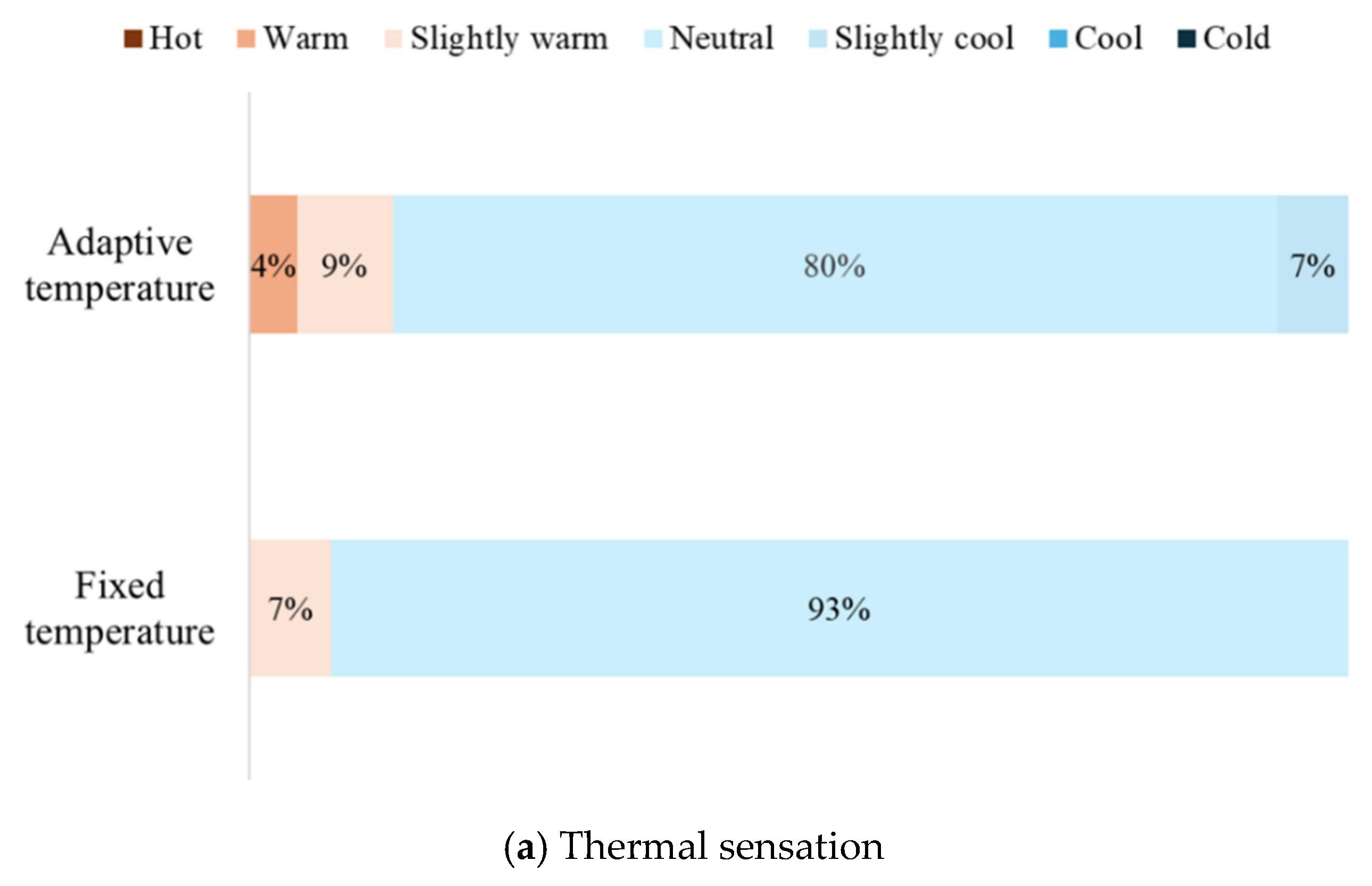

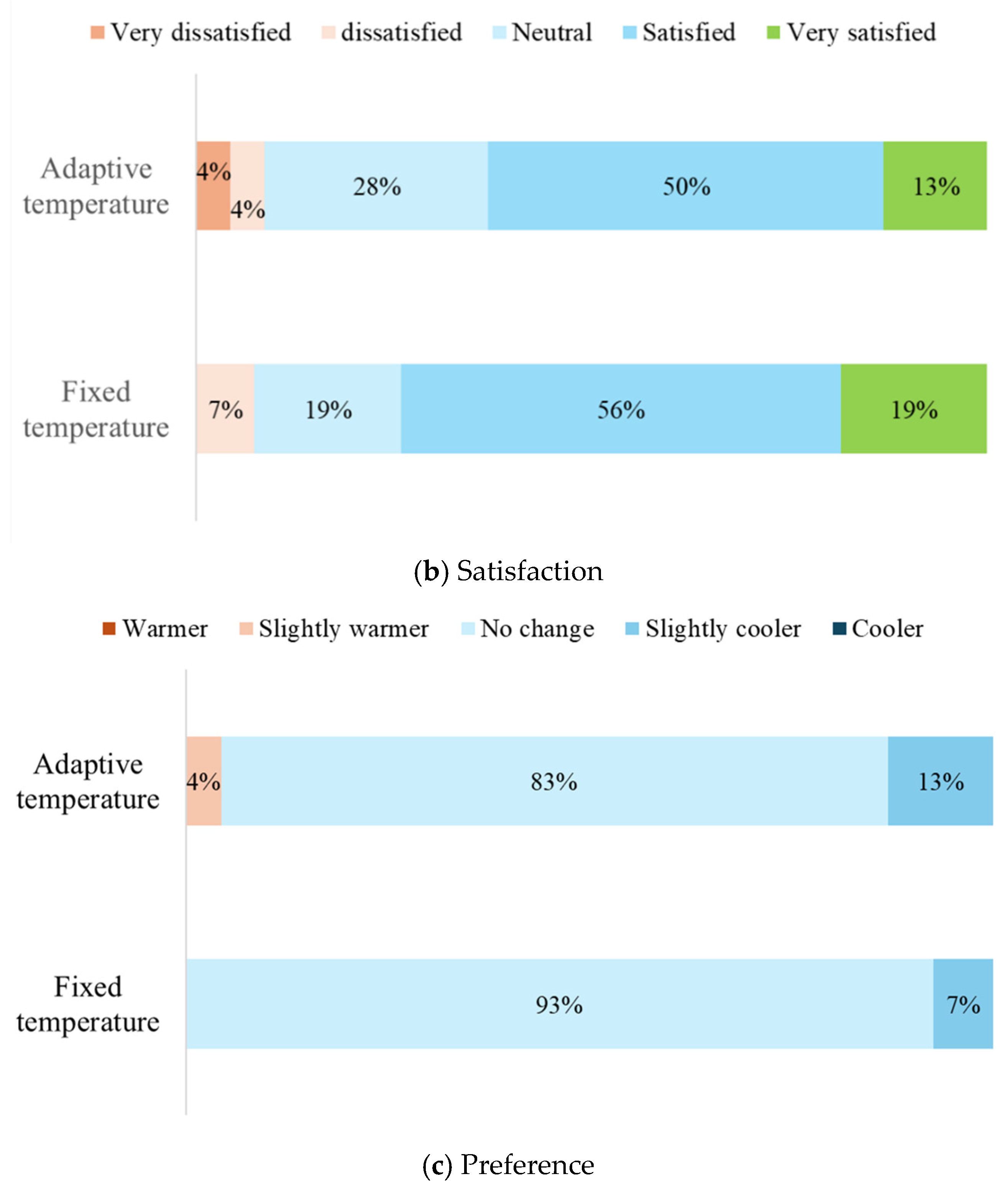

- The occupant thermal comfort survey conducted during the field experiment showed that on fixed setpoint days, 93% of responses to all three questions (thermal sensation, thermal satisfaction, and thermal preference) were positive. On adaptive setpoint days, positive responses were 80% for thermal sensation, 92% for thermal satisfaction, and 83% for thermal preference. These results indicate that the adaptive setpoint did not significantly reduce thermal comfort compared to the fixed setpoint.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Transition to Sustainable Buildings. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/transition-to-sustainable-buildings (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Pérez-Lombard, L.; Ortiz, J.; Pout, C. A review on buildings energy consumption information. Energy Build. 2008, 40, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, R.; Gubernat, A. The rebound effect and Schatzki’s social theory: Reassessing the socio-materiality of energy consumption via a German case study. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 22, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyt, T.; Arens, E.; Zhang, H. Extending air temperature setpoints: Simulated energy savings and design considerations for new and retrofit buildings. Build. Environ. 2015, 88, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyropoulos, G.N.; Balaras, C.A. Energy consumption and the potential of energy savings in Hellenic office buildings used as bank branches—A case study. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palut, M.P.J.; Canziani, O.F. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2007; The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Saidur, R. Energy consumption, energy savings, and emission analysis in Malaysian office buildings. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 4104–4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, N.; Katipamula, S.; Wang, W.; Huang, Y.; Liu, G. Energy savings modelling of re-tuning energy conservation measures in large office buildings. J. Build. Perform. Simul. 2015, 8, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.W.; Han, S.-H. Thermostat strategies impact on energy consumption in residential buildings. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamtraipat, N.; Khedari, J.; Hirunlabh, J.; Kunchornrat, J. Assessment of Thailand indoor set-point impact on energy consumption and environment. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Ramgopal, M. Field studies on human thermal comfort—An overview. Build. Environ. 2013, 64, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, J.F.; Humphreys, M.A. Adaptive thermal comfort and sustainable thermal standards for buildings. Energy Build. 2002, 34, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, C.S.-G.; Mavrogianni, A.; González, F.J.N. On the minimal thermal habitability conditions in low income dwellings in Spain for a new definition of fuel poverty. Build. Environ. 2017, 114, 344–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pattawi, K.; Lee, H. Energy saving impact of occupancy-driven thermostat for residential buildings. Energy Build. 2020, 211, 109791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, D.; Bienvenido-Huertas, D.; Tristancho-Carvajal, M.; Rubio-Bellido, C. Adaptive comfort control implemented model (ACCIM) for energy consumption predictions in dwellings under current and future climate conditions: A case study located in Spain. Energies 2019, 12, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Linden, A.; Boerstra, A.; Raue, A.; Kurvers, S.; de Dear, R. Adaptive temperature limits: A new guideline in The Netherlands: A new approach for the assessment of building performance with respect to thermal indoor climate. Energy Build. 2006, 38, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, D.; Rubio-Bellido, C.; del Río, J.J.M.; Pérez-Fargallo, A. Towards the quantification of energy demand and consumption through the adaptive comfort approach in mixed mode office buildings considering climate change. Energy Build. 2019, 187, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, R.; Maas, M.; Martens, M.; van Schijndel, A.; Schellen, H. Energy conservation in museums using different setpoint strategies: A case study for a state-of-the-art museum using building simulations. Appl. Energy 2015, 158, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, S.; Proverbs, D.; Squires, G. Motivations for energy efficiency refurbishment in owner-occupied housing. Struct. Surv. 2013, 31, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Kwon, S.J. What motivations drive sustainable energy-saving behavior?: An examination in South Korea. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 79, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, T. Commercial property retrofitting: What does “retrofit” mean, and how can we scale up action in the UK sector? J. Prop. Investig. Financ. 2014, 32, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliedt, T.; Hoicka, C.E. Energy upgrades as financial or strategic investment? Energy Star property owners and managers improving building energy performance. Appl. Energy 2015, 147, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manika, D.; Gregory-Smith, D.; Wells, V.K.; Graham, S. Home vs. workplace energy saving attitudes and behaviors: The moderating role of satisfaction with current environmental behaviors, gender, age, and job duration. In Proceedings of the 2015 Winter Marketing Educators’ Conference—Marketing in a Global, Digital and Connected World, San Antonio, TX, USA, 13–15 February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Agha-Hossein, M.M.; Tetlow, R.; Hadi, M.; El-Jouzi, S.; Elmualim, A.; Ellis, J.; Williams, M. Providing persuasive feedback through interactive posters to motivate energy-saving behaviours. Intell. Build. Int. 2015, 7, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Dear, R.; Brager, G.S. Developing an adaptive model of thermal comfort and preference. ASHRAE Trans. 1998, 104, 145–167. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson, T.; de Dear, R.; Brager, G. Nudging the adaptive thermal comfort model. Energy Build. 2020, 206, 109559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.J.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, H. Analysis of Building Retrofit, Ventilation, and Filtration Measures for Indoor Air Quality in a Real School Context: A Case Study in Korea. Buildings 2023, 13, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberl, J.S.; Claridge, D.E.; Culp, C. ASHRAE’s Guideline 14-2002 for Measurement of Energy and Demand Savings: How to Determine what was really saved by the retrofit. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference for Enhanced Building Operations, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 11–13 October 2005. [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers. Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy; American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers: Peachtree Corners, GA, USA, 2004; Volume 55. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, M.; Remøy, H.; Bogaard, M.V.D. Influential design factors on occupant satisfaction with indoor environment in workplaces. Build. Environ. 2019, 157, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, S. Revisiting thermal comfort in the cold climate of Darjeeling, India–Effect of assumptions in comfort scales. Build. Environ. 2021, 203, 108095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| EHP Unit | Floor | Mode | Capacity (kW) | COP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EHP1 | 1F | Cooling | 23.3 | 4.85 |

| Heating | 25.9 | 4.80 | ||

| EHP2, EHP4 | 2F & 4F | Cooling | 57.0 | 3.17 |

| Heating | 63.0 | 3.75 | ||

| EHP3 | 3F | Cooling | 29.2 | 4.42 |

| Heating | 32.8 | 4.56 |

| Month | Energy Consumption Using Fixed Setpoint [kWh] | Energy Consumption Using Adaptive Setpoint [kWh] | Reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| June | 2652 | 2755 | −3.9 |

| July | 4604 | 4054 | 12.0 |

| August | 4200 | 3706 | 11.8 |

| September | 2439 | 2136 | 12.4 |

| Total | 13,895 | 12,650 | 9.0 |

| Survey Question | Response Option | |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal sensation | How do you perceive the current indoor temperature? | Hot |

| Warm | ||

| Slightly warm | ||

| Neutral | ||

| Slightly cool | ||

| Cool | ||

| Cold | ||

| Satisfaction | How satisfied are you with the current indoor temperature? | Very satisfied |

| Satisfied | ||

| Neutral | ||

| Dissatisfied | ||

| Very dissatisfied | ||

| Preference | How would you like to adjust the current indoor temperature? | Much cooler |

| Slightly cooler | ||

| No change | ||

| Slightly warmer | ||

| Much warmer | ||

| Room Usage Type | Fixed Temperature [°C] | Adaptive Temperature [°C] |

|---|---|---|

| 23, 25, and 27 July 2024 | 24, 26, and 28 July 2024 | |

| Office | 24, 26 | 26 |

| Lecture hall | 23 | |

| Exhibition hall | 22 | |

| Hall (2nd floor) | 22 | |

| VR experience room | 22 | |

| Hall (3rd floor) | 22 | |

| 5D theatre | 22 | |

| Café | 25, 26 | |

| Hall (4th floor) | 22 |

| Fixed Setpoint | Adaptive Setpoint | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Mean Outdoor Temperature [°C] | Date | Mean Outdoor Temperature [°C] | |

| Case 1 | 23 July 2024 | 30.9 | 24 July 2024 | 30.4 |

| Case 2 | 25 July 2024 | 31.2 | 26 July 2024 | 31.0 |

| Case 3 | 27 July 2024 | 31.5 | 28 July 2024 | 32.5 |

| Energy Consumption (Fixed Setpoint) [kWh] | Energy Consumption (Adaptive Setpoint) [kWh] | Reduction [%] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 160.7 | 145.3 | 9.6 |

| Case 2 | 194.3 | 177.1 | 8.9 |

| Case 3 | 176.2 | 167.9 | 4.7 |

| Total | 531.2 | 490.3 | 7.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, S.H.; Irakoze, A.; Lee, Y.-A.; Kim, K.H. Balancing Thermal Comfort and Energy Efficiency of a Public Building Through Adaptive Setpoint Temperature. Buildings 2025, 15, 4568. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244568

Jeong SH, Irakoze A, Lee Y-A, Kim KH. Balancing Thermal Comfort and Energy Efficiency of a Public Building Through Adaptive Setpoint Temperature. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4568. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244568

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, So Hyeon, Amina Irakoze, Young-A Lee, and Kee Han Kim. 2025. "Balancing Thermal Comfort and Energy Efficiency of a Public Building Through Adaptive Setpoint Temperature" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4568. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244568

APA StyleJeong, S. H., Irakoze, A., Lee, Y.-A., & Kim, K. H. (2025). Balancing Thermal Comfort and Energy Efficiency of a Public Building Through Adaptive Setpoint Temperature. Buildings, 15(24), 4568. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244568