Enhancing the Activation of Saudi Natural Pozzolan Using Thermal, Mechanical, Chemical, and Hybrid Treatment Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

2.2. Test Methods and Pozzolan Mix Scenarios

2.2.1. Test Methods

2.2.2. Mixture Scenarios

2.3. Natural Pozzolan Treatment Process

2.3.1. Heat Treatment (HT)

2.3.2. Mechanical Treatment (MT)

2.3.3. Hybrid Treatment

2.3.4. Chemical Treatment (CT)

3. Results and Discussion

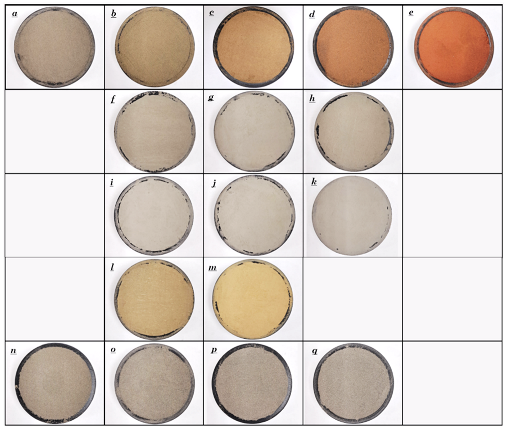

3.1. Colors of Treated Materials

3.2. Performance of Treatments

3.2.1. Heat Treatment (HT)

3.2.2. Mechanical Treatment (MT)

3.2.3. Hybrid Treatment

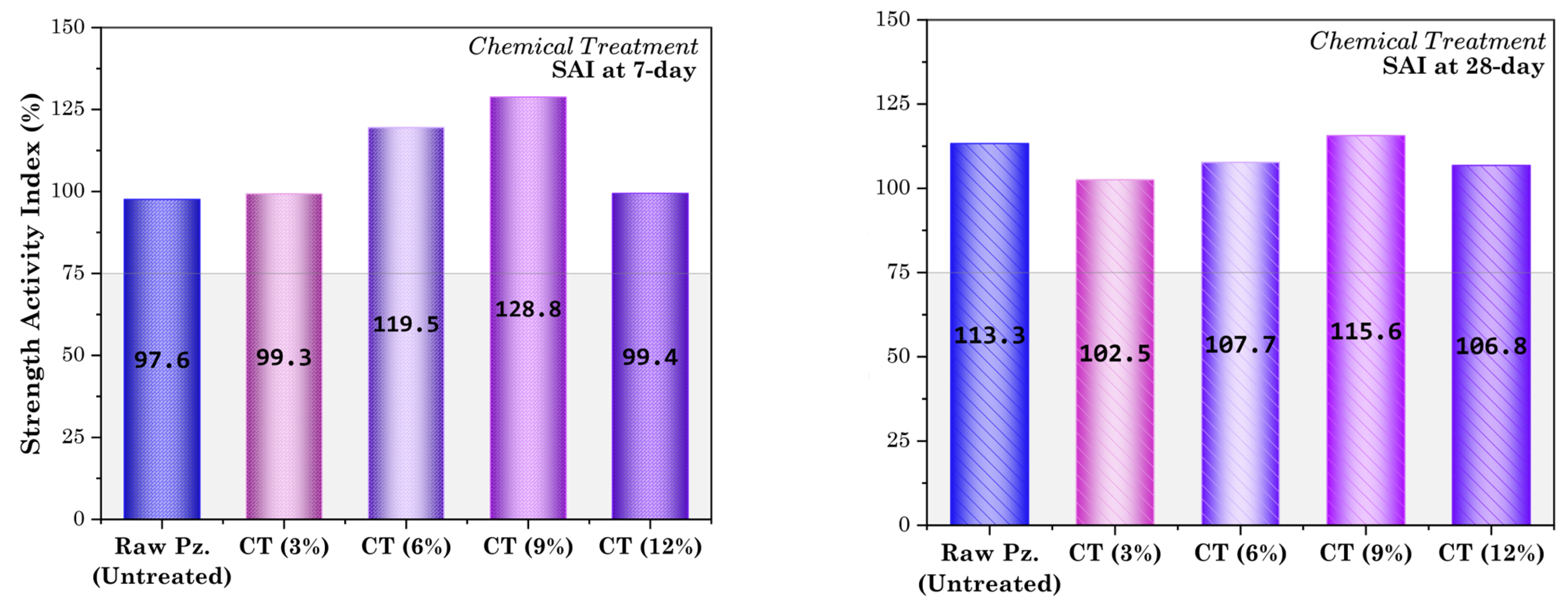

3.2.4. Chemical Treatment (CT)

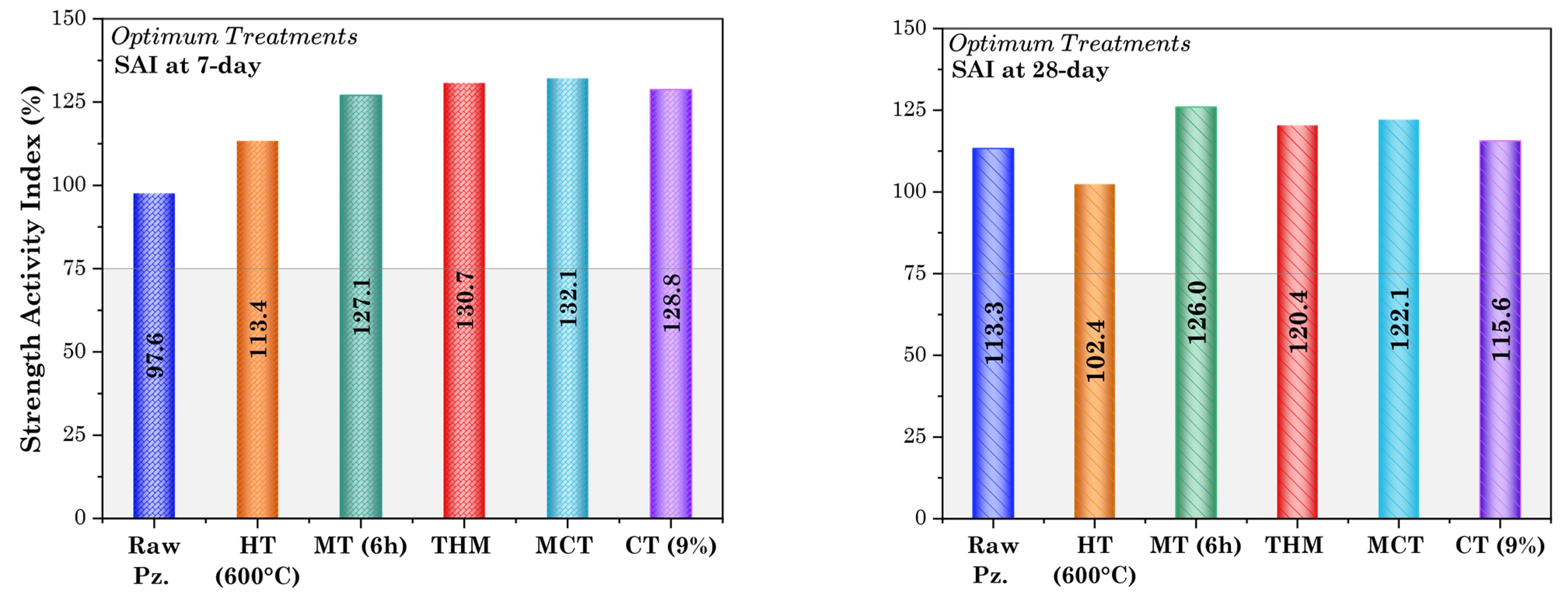

3.3. Optimum Result and Confirmation from Other Analyses

4. Conclusions

- All applied treatment methods effectively activated the SNP, with its SAI exceeding the 75% threshold for pozzolanic activity.

- For the heat treatment (HT) scenarios, the highest UCS value was obtained at 600 °C.

- For the mechanical treatment (MT) scenarios, the highest UCS value was obtained by grinding (MT) for 6 h.

- For the chemical treatment (CT) scenarios, the highest UCS value was obtained with the addition of 9% hydrated lime (HL).

- For hybrid treatment scenarios, mechano-thermal (MCT) demonstrated superior performance compared to thermo-mechanical (TMC).

- The mechanical treatment at 6 h of grinding (MT6h) is identified as the most promising treatment. It produces the highest and most consistent pozzolanic activity across 7 and 28 curing days from the SAI perspective, which is in line with the Frattini pozzolanic activity test.

- Microstructural analyses confirmed the mechanism behind the enhanced performance. XRD analysis supported these findings by detecting key strength-contributing phases, such as quartz, aluminate, and anorthite. The decreasing intensity of HL peaks indicates the successful secondary C-S-H formation, which was directly observed and confirmed by SEM.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Antunes, M.; Santos, R.L.; Pereira, J.; Rocha, P.; Horta, R.B.; Colaço, R. Alternative Clinker Technologies for Reducing Carbon Emissions in Cement Industry: A Critical Review. Materials 2022, 15, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.M.; Hefni, M.A.; Ahmed, H.A.M.; Saleem, H.A. Cement Kiln Dust (CKD) as a Partial Substitute for Cement in Pozzolanic Concrete Blocks. Buildings 2023, 13, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bakri, A.Y.; Ahmed, H.M.; Hefni, M.A. Eco-Sustainable Recycling of Cement Kiln Dust (CKD) and Copper Tailings (CT) in the Cemented Paste Backfill. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juenger, M.C.G.; Snellings, R.; Bernal, S.A. Supplementary cementitious materials: New sources, characterization, and performance insights. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 122, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yang, C.; Liu, F.; Wan, C.; Pu, X. Preparation of Ultra-High Performance Concrete with common technology and materials. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2012, 34, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeloudis, C.; Zervaki, M.; Sideris, K.; Juenger, M.; Alderete, N.; Kamali-Bernard, S.; Villagrán, Y.; Snellings, R. Natural Pozzolans. In Properties of Fresh and Hardened Concrete Containing Supplementary Cementitious Materials: State-of-the-Art Report of the RILEM Technical Committee 238-SCM, Working Group 4; De Belie, N., Soutsos, M., Gruyaert, E., Eds.; RILEM State-of-the-Art Reports; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 181–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, V.M.; Mehta, P.K. Pozzolanic and Cementitious Materials; CRC Press: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suraneni, P.; Weiss, J. Examining the pozzolanicity of supplementary cementitious materials using isothermal calorimetry and thermogravimetric analysis. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2017, 83, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senhadji, Y.; Escadeillas, G.; Mouli, M.; Khelafi, H. Influence of natural pozzolan, silica fume and limestone fine on strength, acid resistance and microstructure of mortar. Powder Technol. 2014, 254, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Wang, H. Recent progress of utilization of activated kaolinitic clay in cementitious construction materials. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 211, 108636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, D.T.; Robinson, J.E.; Stelten, M.E.; Champion, D.E.; Dietterich, H.R.; Sisson, T.W.; Zahran, H.; Hassan, K.; Shawali, J. Geologic Map of the Northern Harrat Rahat Volcanic Field, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; US Department of the Interior, US Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2019.

- Donatello, S.; Tyrer, M.; Cheeseman, C.R. Comparison of test methods to assess pozzolanic activity. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2010, 32, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, A.; Sertabipoğlu, Z. Effect of heat treatment on pozzolanic activity of volcanic pumice used as cementitious material. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2015, 57, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tironi, A.; Trezza, M.A.; Irassar, E.F.; Scian, A.N. Thermal Treatment of Kaolin: Effect on the Pozzolanic Activity. Procedia Mater. Sci. 2012, 1, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- al-Swaidani, A.M.; Aliyan, S.D.; Adarnaly, N. Mechanical strength development of mortars containing volcanic scoria-based binders with different fineness. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2016, 19, 970–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A. The effect of various chemical activators on pozzolanic reactivity: A review. Sci. Res. Essays 2012, 7, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amoudi, O.S.B.; Ahmad, S.; Maslehuddin, M.; Khan, S.M.S. Lime-activation of natural pozzolan for use as supplementary cementitious material in concrete. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Martínez, A.E.; González-López, J.R.; Guerra-Cossío, M.A.; Hernández-Carrillo, G. Sulphate-based activation of a binary and ternary hybrid cement with portland cement and different pozzolans. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 421, 135683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Jiang, W.; Roy, D.M. Early activation and properties of slag cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 1990, 20, 961–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, M.; Kacimi, L.; Cyr, M.; Clastres, P. Evaluation and improvement of pozzolanic activity of andesite for its use in eco-efficient cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 47, 1268–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Amin, M.N.; Usman, M.; Imran, M.; Al-Faiad, M.A.; Shalabi, F.I. Effect of Fineness and Heat Treatment on the Pozzolanic Activity of Natural Volcanic Ash for Its Utilization as Supplementary Cementitious Materials. Crystals 2022, 12, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashish, D.K.; Singh, B.; Verma, S.K. The effect of attack of chloride and sulphate on ground granulated blast furnace slag concrete. Adv. Concr. Constr. 2016, 4, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenka, S.; Panda, K.C. Effect of metakaolin on the properties of conventional and self compacting concrete. Adv. Concr. Constr. 2017, 5, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahiaoui, W.; Kenai, S.; Menadi, B.; Kadri, E.-H. Durability of self compacted concrete containing slag in hot climate. Adv. Concr. Constr. 2017, 5, 271. [Google Scholar]

- Djamila, B.; Othmane, B.; Said, K.; El-Hadj, K. Combined effect of mineral admixture and curing temperature on mechanical behavior and porosity of SCC. Adv. Concr. Constr. 2018, 6, 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ghahari, S.A.; Ramezanianpour, A.M.; Ramezanianpour, A.A.; Esmaeili, M. An Accelerated Test Method of Simultaneous Carbonation and Chloride Ion Ingress: Durability of Silica Fume Concrete in Severe Environments. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2016, e1650979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, T.; Panda, K.C. Mechanical and durability properties of marine concrete using fly ash and silpozz. Adv. Concr. Constr. 2018, 6, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, K.; Amin, M.N.; Saleem, M.U.; Qureshi, H.J.; Al-Faiad, M.A.; Qadir, M.G. Effect of Fineness of Basaltic Volcanic Ash on Pozzolanic Reactivity, ASR Expansion and Drying Shrinkage of Blended Cement Mortars. Materials 2019, 12, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alraddadi, S. The impact of thermal treatment on the mechanical properties and thermal insulation of building materials enhanced with two types of volcanic scoria additives. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebig, E.; Althaus, E. Pozzolanic Activity of Volcanic Tuff and Suevite: Effects of Calcination. Cem. Concr. Res. 1998, 28, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-swaidani, A.M. Natural pozzolana of micro and nano-size as cementitious additive: Resistance of concrete/mortar to chloride and acid attack. Cogent Eng. 2021, 8, 1996306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM-C125; Standard Terminology Relating to Concrete and Concrete Aggregates. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Oh, J.E.; Jun, Y.; Park, J.; Ha, J.; Sohn, S.G. Influence of four additional activators on hydrated-lime [Ca(OH)2] activated ground granulated blast-furnace slag. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 65, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Day, R.L. Chemical activation of blended cements made with lime and natural pozzolans. Cem. Concr. Res. 1993, 23, 1389–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.M.S. Production of Sustainable Concrete Using Indigenous Saudi Natural Pozzolan. Ph.D. Thesis, King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, A.; El Amrani El Hassani, I.-E.; El Khadiri, A.; Sadik, C.; El Bouari, A.; Ballil, A.; El Haddar, A. Effect of slaked lime on the geopolymers synthesis of natural pozzolan from Moroccan Middle Atlas. J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 56, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C311/C311M-22; Standard Test Methods for Sampling and Testing Fly Ash or Natural Pozzolans for Use in Portland-Cement Concrete. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022. [CrossRef]

- PCE-Instrument Brightness Tester PCE-WSB 1|PCE Instruments. Available online: https://www.pce-instruments.com/english/measuring-instruments/test-meters/brightness-tester-pce-instruments-brightness-tester-pce-wsb-1-det_2209963.htm (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Li, Q.; Wu, A.; Zhang, M.; Li, J.; Cao, J.; Li, H.; Jiang, Y. Study on the Influence of Calcination Temperature of Iron Vitriol on the Coloration of Ancient Chinese Traditional Iron Red Overglaze Color. Materials 2024, 17, 2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, T.L.; Brauer, C.S.; Su, Y.-F.; Blake, T.A.; Tonkyn, R.G.; Ertel, A.B.; Johnson, T.J.; Richardson, R.L. Quantitative reflectance spectra of solid powders as a function of particle size. Appl. Opt. 2015, 54, 4863–4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Li, Z.; Xin, G.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y. Utilization of High-Volume Red Mud Application in Cement Based Grouting Material: Effects on Mechanical Properties at Different Activation Modes. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2023, 35, 04023011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, Z.; Yang, S.; Zhang, K.; Chang, J. Synthesis process-based mechanical property optimization of alkali-activated materials from red mud: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 344, 118616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Kinnunen, P.; Sreenivasan, H.; Adesanya, E.; Illikainen, M. Structural collapse in phlogopite mica-rich mine tailings induced by mechanochemical treatment and implications to alkali activation potential. Miner. Eng. 2020, 151, 106331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Peng, Z.; Wang, X.; He, Y.; Huang, S.; Wan, J.; Wang, B.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, H.; Zheng, H. The effect of high energy ball milling on the structure and properties of two greenish mineral pigments. Dyes Pigments 2021, 193, 109494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, R.; Xu, Z.; Li, S.; Lian, J.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, G. Enhancing the brightness and saturation of noniridescent structural colors by optimizing the grain size. Nanoscale Adv. 2020, 2, 4581–4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowska-Wichrowska, K.; Pawluczuk, E.; Bołtryk, M. Waste-free technology for recycling concrete rubble. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 234, 117407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, I.H.A.; Abdullah, M.M.A.B.; Razak, R.A.; Yahya, Z.; Salleh, M.A.A.M.; Chaiprapa, J.; Rojviriya, C.; Vizureanu, P.; Sandu, A.V.; Tahir, M.F.; et al. Mechanical Performance, Microstructure, and Porosity Evolution of Fly Ash Geopolymer after Ten Years of Curing Age. Materials 2023, 16, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regalla, S.S.; Senthil Kumar, N. Investigation of hydration kinetics, microstructure and mechanical properties of multiwalled carbon nano tubes (MWCNT) based future emerging ecological economic ultra high-performance concrete (E3 UHPC). Results Eng. 2024, 23, 102432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.-Y. A Hydration Model to Evaluate the Properties of Cement–Quartz Powder Hybrid Concrete. Materials 2024, 17, 2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franus, W.; Panek, R.; Wdowin, M. SEM Investigation of Microstructures in Hydration Products of Portland Cement. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Multidisciplinary Microscopy and Microanalysis Congress, Oludeniz, Turkey, 16–19 October 2014; Polychroniadis, E.K., Oral, A.Y., Ozer, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Šádková, K.; Pommer, V.; Keppert, M.; Vejmelková, E.; Koňáková, D. Difficulties in Determining the Pozzolanic Activity of Thermally Activated Lower-Grade Clays. Materials 2024, 17, 5093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, A.M. A comprehensive overview about the effect of nano-SiO2 on some properties of traditional cementitious materials and alkali-activated fly ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 52, 437–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tognonvi, M.T.; Tagnit-Hamou, A.; Konan, L.K.; Zidol, A.; N’Cho, W.C. Reactivity of recycled glass powder in a cementitious medium. New J. Glass Ceram. 2020, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyasigorji, F.; Farajiani, F.; Hajipour Manjili, M.; Lin, Q.; Elyasigorji, S.; Farhangi, V.; Tabatabai, H. Comprehensive Review of Direct and Indirect Pozzolanic Reactivity Testing Methods. Buildings 2023, 13, 2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.-S.; Huang, C.-L.; Hsu, K.-C. The pozzolanic activity of a calcined waste FCC catalyst and its effect on the compressive strength of cementitious materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 196-5:2011; Methods of Testing Cement Pozzolanicity Test for Pozzolanic Cement. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

| Material | CaO | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | SO3 | MgO | K2O | K2O | Na2O | TiO2 | LOI * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPC | 34.68 | 14.91 | 1.89 | N/A | 2.92 | 1.24 | N/A | N/A | 1.51 | N/A | N/A |

| Scoria | 5.88 | 54.38 | 14.21 | 18.43 | 0.1 | 2.57 | 3.91 | 3.91 | 4.88 | 3.52 | 7.8 |

| Material | Density (g/cm3) | Specific Surface Area/Fineness (m2/g) | Retained on a 45-μm Sieve (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scoria | 2.52 | 0.365 | 14.21 |

| No. | Elements, Symbol | Detection Limit | Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μg/L | μg/L | |||

| 1 | Silver | Ag | 0.1 | <0.1 |

| 2 | Aluminium | Al | 0.1 | 45.65 |

| 3 | Arsenic | As | 0.1 | <0.1 |

| 4 | Boron | B | 0.1 | 1033.16 |

| 5 | Barium | Ba | 0.1 | 4.68 |

| 6 | Beryllium | Be | 0.5 | <0.5 |

| 7 | Bismuth | Bi | 0.1 | <0.1 |

| 8 | Bromine | Br | 0.1 | 304.54 |

| 9 | Cadmium | Cd | 0.1 | <0.1 |

| 10 | Chromium | Cr | 0.1 | 0.31 |

| 11 | Cesium | Cs | 0.1 | <0.1 |

| 12 | Cupper | Cu | 0.1 | 6.63 |

| 13 | Mercury | Hg | 0.1 | <0.1 |

| 14 | Iodine | I | 0.1 | 0.26 |

| 15 | Lithium | Li | 0.1 | 4.86 |

| 16 | Manganese | Mn | 0.1 | 1.2 |

| 17 | Nickel | Ni | 0.1 | 4.84 |

| 18 | Lead | Pb | 0.1 | 1.03 |

| 19 | Rubidium | Rb | 0.1 | 0.39 |

| 20 | Antimony | Sb | 0.5 | <0.5 |

| 21 | Selenium | Se | 0.1 | 2.51 |

| 22 | Tin | Sn | 0.1 | 0.29 |

| 23 | Strontium | Sr | 0.1 | 12.17 |

| 24 | Tantalum | Ta | 0.1 | <0.1 |

| 25 | Thallium | Tl | 0.1 | <0.1 |

| 26 | Uranium | U | 0.1 | <0.1 |

| 27 | Zinc | Zn | 0.1 | 89.1 |

| Parameter | Unit | Detection Limit | Value | |

| Ca | mg/L | 0.01 | 20.67 | |

| Mg | mg/L | 0.01 | 1.16 | |

| Na | mg/L | 0.01 | 54.09 | |

| K | mg/L | 0.01 | 2.67 | |

| Fe | mg/L | 0.01 | 0.02 | |

| Cl | mg/L | 1 | 81 | |

| HCO3 | mg/L | 1 | 68 | |

| NO3 | mg/L | 0.4 | <0.40 | |

| SO4 | mg/L | 0.01 | 2 | |

| F | mg/L | 0.01 | 0.5 | |

| NO2 | mg/L | 0.04 | <0.04 | |

| T.D.S | mg/L | 195 | 195 | |

| Conductivity | µs/cm | 302 | 302 | |

| pH | 1 | 7.1 | ||

| Turbidity | NTU | 0.02 | 0.27 | |

| Material | Treatment | OPC (g) | Pozzolan (g) | Standard Graded Sand (g) | Water (g) | Samples (7 and 28 d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Mixture | Control | 500 | - | 1375 | 242.0 | 6 |

| Raw Pozzolan | Untreated | 400 | 100 | 1375 | 244.1 | 6 |

| PZ-HT500 °C | Thermal (HT) | 400 | 100 | 1375 | 244.1 | 6 |

| PZ-HT600 °C | 400 | 100 | 1375 | 244.1 | 6 | |

| PZ-HT800 °C | 400 | 100 | 1375 | 244.1 | 6 | |

| PZ-HT1000 °C | 400 | 100 | 1375 | 244.1 | 6 | |

| PZ-MT-2 h | Mechanical (MT) | 400 | 100 | 1375 | 244.1 | 6 |

| PZ-MT-4 h | 400 | 100 | 1375 | 244.1 | 6 | |

| PZ-MT-6 h | 400 | 100 | 1375 | 244.1 | 6 | |

| PZ-MT-12 h | 400 | 100 | 1375 | 244.1 | 6 | |

| PZ-MT-18 h | 400 | 100 | 1375 | 244.1 | 6 | |

| PZ-MT-24 h | 400 | 100 | 1375 | 244.1 | 6 | |

| PZ-thermo-mechanical | Hybrid | 400 | 100 | 1375 | 244.1 | 6 |

| PZ-mechano-thermal | 400 | 100 | 1375 | 244.1 | 6 | |

| PZ-CT-3% HL | Chemical (CT) | 400 | 100 | 1375 | 244.1 | 6 |

| PZ-CT-6% HL | 400 | 100 | 1375 | 244.1 | 6 | |

| PZ-CT-9% HL | 400 | 100 | 1375 | 244.1 | 6 | |

| PZ-CT-12% HL | 400 | 100 | 1375 | 244.1 | 6 | |

| Total | 7300 | 1700 | 24,750 | 4391.7 | 108 | |

| Grinding Time (hours) | Grinding Speed (rpm) | Recorded Power (%) by the Crusher | Amount of Big and Medium Balls | Number of Small Balls | Specific Surface Area (m2/g) | Particle Size d50 (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Raw Material (Original Sample) | 0.37 | NA | |||

| 2 | 150 | 67 | 7 | 88 | 1.68 | 11.12 |

| 4 | 150 | 67 | 7 | 88 | 2.07 | 7.69 |

| 6 | 150 | 67 | 7 | 88 | 2.52 | 5.80 |

| 12 | 150 | 67 | 7 | 88 | 3.66 | 3.71 |

| 18 | 150 | 67 | 7 | 88 | 3.81 | 2.96 |

| 24 | 150 | 70 | 7 | 88 | 4.04 | 3.13 |

| Code | Material | Wb * | Color of Pozzolans |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | PZ-Original | 11.14 |  |

| b | HT-500 | 10.24 | |

| c | HT-600 | 9.02 | |

| d | HT-800 | 6.4 | |

| e | HT-1000 | 5.24 | |

| f | MT-2H | 16.2 | |

| g | MT-4H | 20.5 | |

| h | MT-6H | 18.66 | |

| i | MT-12H | 22.66 | |

| j | MT-18H | 21.9 | |

| k | MT-24H | 23.92 | |

| l | THMC | 15.36 | |

| m | MCTH | 17.36 | |

| n | CT-3% HL | 12.16 | |

| o | CT-6% HL | 13.36 | |

| p | CT-9% HL | 14.36 | |

| q | CT-12 HL | 15.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tanjung, A.A.; Ahmed, H.M.; Ahmed, H.A.M. Enhancing the Activation of Saudi Natural Pozzolan Using Thermal, Mechanical, Chemical, and Hybrid Treatment Approaches. Buildings 2025, 15, 4535. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244535

Tanjung AA, Ahmed HM, Ahmed HAM. Enhancing the Activation of Saudi Natural Pozzolan Using Thermal, Mechanical, Chemical, and Hybrid Treatment Approaches. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4535. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244535

Chicago/Turabian StyleTanjung, Ardhymanto Am, Haitham M. Ahmed, and Hussin A. M. Ahmed. 2025. "Enhancing the Activation of Saudi Natural Pozzolan Using Thermal, Mechanical, Chemical, and Hybrid Treatment Approaches" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4535. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244535

APA StyleTanjung, A. A., Ahmed, H. M., & Ahmed, H. A. M. (2025). Enhancing the Activation of Saudi Natural Pozzolan Using Thermal, Mechanical, Chemical, and Hybrid Treatment Approaches. Buildings, 15(24), 4535. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244535