3.1. Hebei Ancient Village Color Digitizing

To answer RQ1. What are the dominant chromatic attributes (hue, lightness, chroma) of Hebei’s ancient villages.

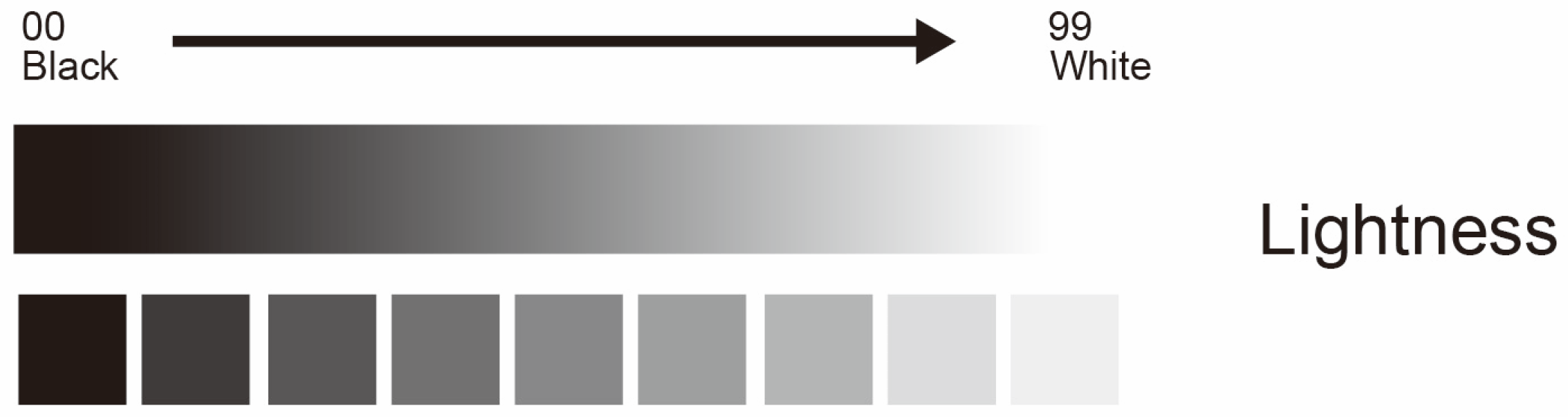

The researcher employed the COLORO analysis software (CCI) to obtain digitally processed colour data (as shown in

Figure 6). Representative images from four ancient villages—Yingtang Village (Xingtai County), Yujia Village (Jingxing County), Boyan Ancient Town (Handan City), and Nuanquan Town (Yu County)—were selected for colour extraction. The analysis encompassed four dimensions: colour numbers, colour samples, colour sources, and primary construction materials. Colour values were extracted according to the three attributes of hue, lightness, and saturation, and colour patches were identified from the images of the ancient villages. As illustrated in the figure, the values 029-28-08 correspond, respectively, to hue, lightness, and saturation, where a hue value of 029, lightness value of 28, and saturation value of 08 were recorded.

The representative images of four ancient villages—Yingtang Village (Xingtai County), Yujia Village (Jingxing County), Boyan Ancient Town (Handan City), and Nuanquan Town (Yu County)—were selected for colour extraction. The analysis yielded systematic data covering four dimensions: colour numbers, colour samples, colour sources, and primary construction materials.

Despite minor discrepancies between photographs and actual artefacts caused by environmental conditions and lighting, the extracted values remain sufficiently accurate to represent the overall chromatic characteristics of the villages. The results highlight distinct tonal palettes shaped by building materials such as slate, stone, brick, and timber.

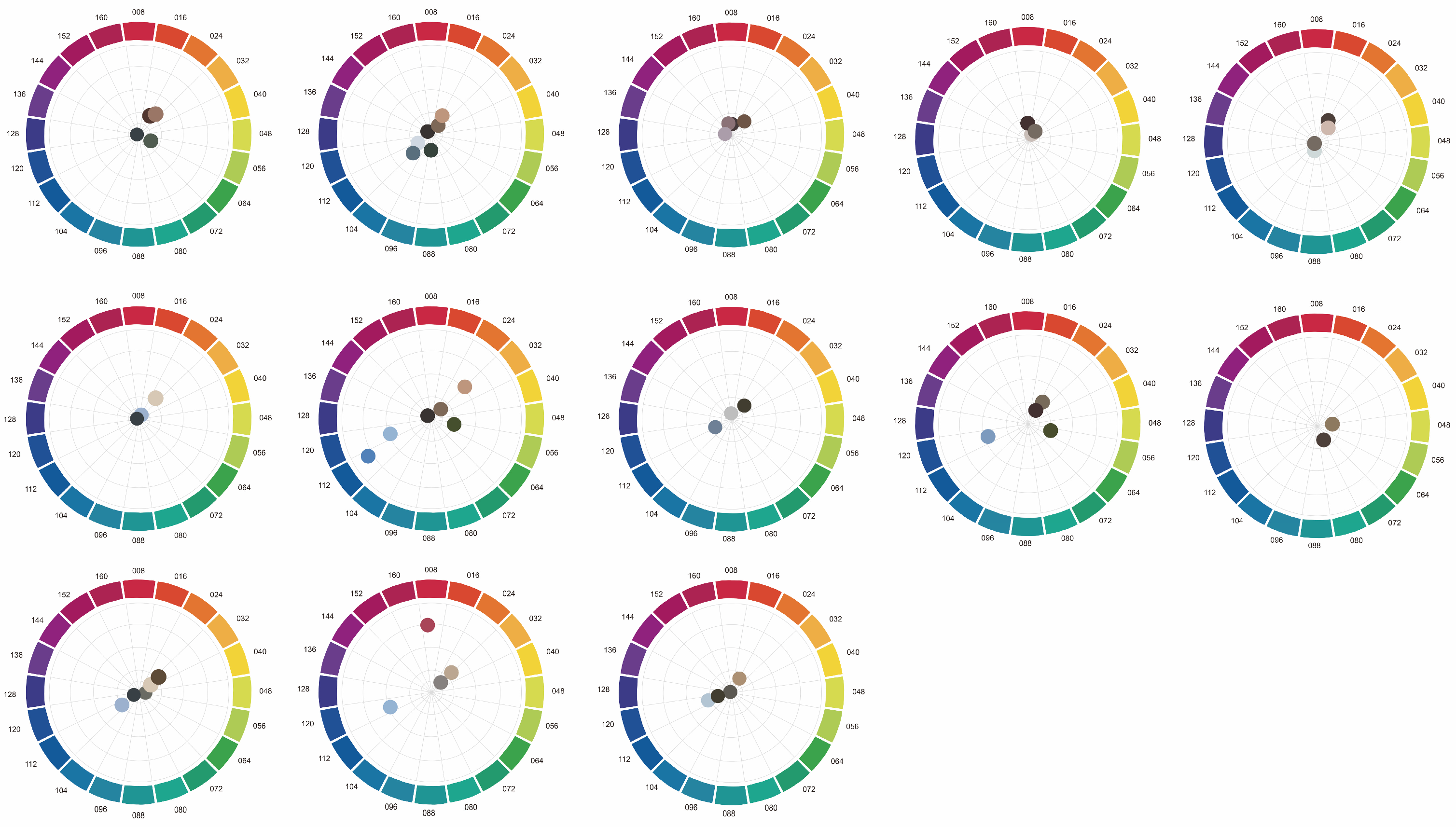

Figure 7 illustrates these colour data in terms of hue, lightness, and saturation, providing an empirical basis for identifying the chromatic identity of Hebei’s ancient villages.

Firstly, the color values of the principal buildings were extracted (

Figure 8). The results indicate a high concentration of hues within the range of 020–049, corresponding to the red–orange–yellow spectrum. Lightness values are predominantly distributed between 21–61, representing low to medium brightness, while chroma is largely concentrated within 02–12, reflecting low to medium saturation. The primary building materials are locally sourced, such as the distinctive red slate from Yingtan Village, along with other types of indigenous stone. Consequently, the architectural colors are characterized by warm and earthy tones, predominantly heavy brown, ochre, and related variations.

The color values of the walls were extracted (

Figure 9). The results show a high concentration of hues in the range of 028–053, corresponding to the red–orange–yellow spectrum, alongside occasional hues such as 078 and 139, which represent green and blue-violet tones. Brightness values are mainly distributed between 20–60, indicating low to medium levels, while certain areas affected by light exhibit higher values between 60–80, falling into the medium-high brightness range. Chroma is largely concentrated in the 02–12 interval, reflecting a predominance of low to medium saturation.

The construction materials of the walls are also predominantly locally sourced, though they vary in composition and treatment. In Nuanquan Ancient Town, for example, stone walls are externally coated with a layer of yellow clay, which produces a consistent warm yellow surface tone. By contrast, the primary wall material in Burian Ancient Town consists of green stone bricks, which generate cooler blue-green hues. These variations result in a composite palette that includes warm yellow, heavy brown, ochre, as well as cooler blue-green and blue-violet tones. Overall, the darker and denser visual effect of the walls can be attributed to the relatively low brightness and chroma values.

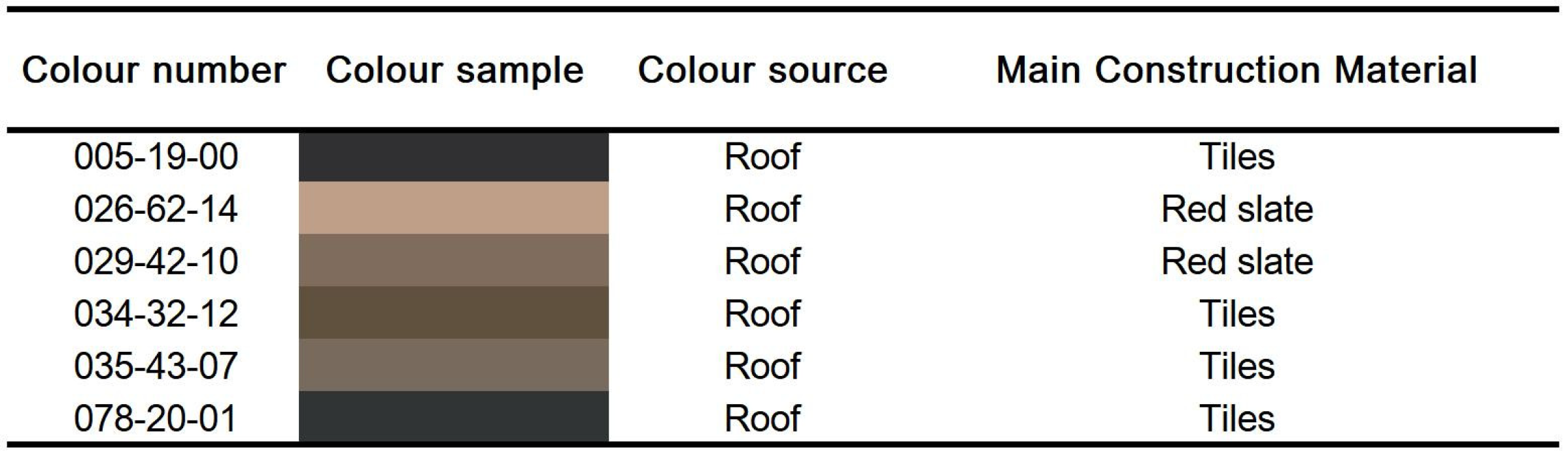

The roof color values were extracted (

Figure 10). Hues are mainly concentrated in the range of 005–035 (red–orange–yellow), with some values such as 078 showing blue-green. Brightness is mostly between 01–14, indicating very low levels, while chroma falls within 01–12, showing low to medium saturation.

The roof materials differ slightly from those of the walls. In Yingtan Village, large pieces of red slate, also used for the walls, are applied to the roofs, giving a consistent warm tone. In Boyan Ancient Town, by contrast, green stone bricks are used for the walls, while the roofs are covered with dark grey tiles. As a result, the roof colors present both warm and cool tones, including red, cyan, and dark grey. Overall, the roofs appear heavy and intense, with deep red and dark grey dominating due to the generally low brightness and chroma.

The barrier colors of the historic hamlet were extracted (

Figure 11). Hues are concentrated in 009–027 (red–orange), with brightness values in 22–49 (medium-low) and chroma in 06–11 (medium-low). The materials match those of nearby buildings; in Yingtan Village, for instance, fences are made of large red slate stones. As a result, the barriers show dominant red and yellow tones, with strong, heavy reds and warm oranges.

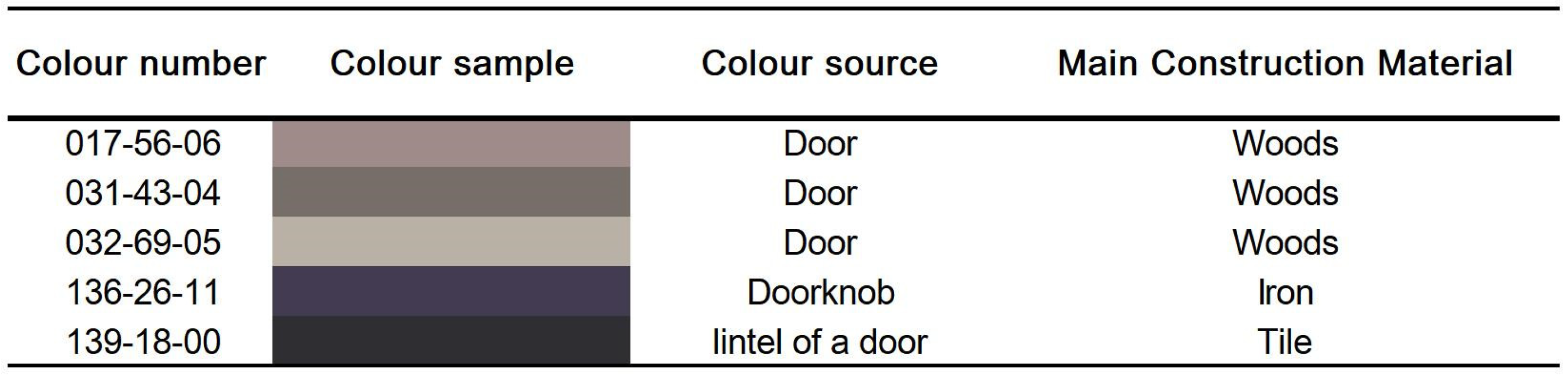

The door colors were extracted (

Figure 12). Hues are concentrated in 017–032 (red–orange–yellow), with brightness in 43–69 (medium-high) and chroma in 04–06 (low). Made mainly of light wood, the doors show light beige and light red tones, giving a rustic and elegant effect. The iron handles (hue 136–139, blue-violet) have low brightness (18–26) and low chroma (00–11), appearing as dark iron grey.

Colour values were extracted from the decorative elements of ancient buildings. In the photographs of the ancient villages, the main decorations—red couplets and red lanterns—display distinctive Chinese cultural features. The hue values are concentrated around region 05–016, between red and red-orange; brightness values fall within 39–45, representing a medium brightness level; and chroma values are concentrated in 28–31, corresponding to high colour saturation. These colour characteristics originate from the materials used, primarily red rice paper and red cloth, which naturally produce red and orange-red tones. Because these materials possess strong chromatic purity, the resulting colour appears as a vivid and saturated “Chinese red.” Overall, the decorative palette is full, bright, and rich in festive atmosphere.

The chromatic distribution chart shows that the houses, bridges, and streets of Yingtan Village are built from local red slate, with red and yellow as the dominant tones. As a result, the village exhibits a medium-low chromatic red, producing a dense and rich atmosphere that defines its distinctive color identity. Similarly, Nuquan Ancient Village and West Ancient Fortress in Yu County rely on indigenous resources. In the West Ancient Fortress, brick and wood construction dominate, with green-brick walls and grey-tiled roofs producing yellow and cyan as the primary tones. The nine-color gamut distribution chart positions these colors at the center, with low brightness and weak saturation, creating a calm and straightforward overall tone.

Yu Jia Village in Jingxing, Hebei, is almost entirely stone-built—featuring stone houses, walls, streets, pavilions, bridges, fences, tanks, and mills. Across Hebei’s historic villages, red, yellow, and cyan emerge as the predominant colors, covering most building surfaces. Yet, their brightness and saturation are generally subdued, falling within the moderate brightness/low chroma and low brightness/low chroma zones of the nine-color gamut distribution. This chromatic pattern reflects the reliance on local building resources, especially stone, which imparts a warm grey tone marked by simplicity and solidity. By contrast, decorative elements such as lanterns and couplets are intensely saturated and vividly colored, standing in sharp contrast to the rustic and restrained architectural palette.

3.2. Hebei Ancient Village Color Data Analysis

In the data analysis stage, the extracted color values were processed using the COLORO color analysis software (CCI) to establish a color database for traditional villages in Hebei (

Figure 13). The hue distribution map and the nine-color gamut distribution map were then applied to present the overall chromatic characteristics of village architecture. The hue distribution map illustrates the frequency of different hues within the images, highlighting the dominance of red, yellow, and cyan in the architectural palette. Meanwhile, the nine-color gamut distribution map reveals the clustering of these hues in specific ranges of brightness and chroma, thereby providing a clear visual representation of the overall color composition and characteristics of the villages.

As shown in the chromatic distribution map (

Figure 14), the chromaticity of the buildings and streets in the ancient village is mainly concentrated in the red–orange–yellow range, with occasional blue tones. After excluding the environmental blue of the sky, the color palette is represented by plain beige, rustic pale yellow, ochre, brown, crimson, dark grey, and dark blue.

The nine-color gamut distribution map (

Figure 15) shows that the colors are mainly concentrated in low-chroma/low-lightness, medium-lightness, and medium-chroma/high-lightness regions. The dominant tone is generally dark, with only a small number of elements displaying moderate brightness and higher chroma. In contrast, the decorative elements present vivid and refined hues. Our analysis indicates that the traditional villages of Hebei possess a distinctive palette that differs from the “white walls and black tiles” of Jiangnan towns, thereby highlighting the individuality of Hebei’s ancient villages. Warm yellow tones, deep ochre and brown shades, together with subtle greys and vibrant scarlets, form a simple, weighty, yet opulent northern color palette.

The chromatic analysis of Hebei’s ancient villages reveals a distinctive regional palette shaped by local materials and cultural practices. The hue distribution maps (

Figure 14) indicate that architectural colors are primarily concentrated in the red–orange–yellow spectrum, complemented by muted tones such as beige, pale yellow, ochre, brown, crimson, dark grey, and dark blue. The nine-color gamut distribution map (

Figure 8) further shows that most colors fall within low chroma/low lightness and medium-lightness zones, creating an overall dark and subdued atmosphere. In contrast, decorative elements such as lanterns and couplets introduce vivid, highly saturated reds, enhancing visual dynamism. Together, these chromatic characteristics distinguish Hebei’s ancient villages from the “white walls and black tiles” of Jiangnan architecture, forming a northern color palette that is simple, weighty, and culturally expressive.

3.3. Cultural Identity and Symbolic Meaning of Color in Hebei’s Ancient Villages

To answer RQ2. How do local stakeholders interpret these colours in relation to cultural symbolism and place identity.

This study aims to explore the role of color in shaping the identity of ancient villages in Hebei and to identify its potential influencing factors. When asked about the chromatic characteristics of these villages, local cultural experts typically referred to their knowledge of building materials and regional culture. The participants defined the main aesthetic and artistic features of Hebei’s ancient villages, highlighting the cultural significance of architectural color. They also stressed the importance of restoration and preservation, particularly in the context of tourism development. Overall, the respondents affirmed the cultural meaning and representational role of color in ancient villages.

Figure 16 illustrates the critical themes linking the colors of Hebei’s ancient villages with cultural identity.

Beyond the general chromatic contrast between muted architectural tones and vivid decorations, colour in Hebei’s ancient villages performs distinct social and functional roles depending on spatial context. In religious and theatrical structures—such as temples and performance stages—bright reds, golds, and greens dominate, symbolising prosperity, divine blessing, and collective celebration. By contrast, residential buildings are characterised by restrained palettes of ochre, brown, and grey, reflecting values of humility, endurance, and harmony with the natural environment. This differentiation underscores a cultural semiotic logic in which chromatic intensity corresponds to the social hierarchy and ritual significance of space.

The evolution of colour usage also reflects historical continuity and adaptation. Architectural remains from the Ming and Qing dynasties display a stable reliance on locally available red slate and grey brick, whereas twentieth-century repairs introduced lighter yellows and artificial pigments, expanding chromatic diversity. Interview participants noted that while the overall tone of Hebei villages remains earthy and subdued, decorative elements increasingly incorporate brighter hues during festivals, signifying cultural resilience and adaptation to modern aesthetic sensibilities. This diachronic perspective highlights colour as a living cultural medium shaped by both tradition and change.

3.3.1. Theme 1: Regional Color Identity of Hebei Villages

Color contributes significantly to the visual identity of a village, distinguishing it from others. Its use varies across regions, shaped by differences in local materials, climate, and cultural practices. For instance, the ochre tones of Mediterranean villages and the whitewashed walls of Greek settlements are iconic demonstrations of how color defines regional identity [

27]. Similarly, the grey stone buildings of ancient villages in Hebei reflect both the availability of local stone resources and the functional need for durability, thereby linking materiality with chromatic expression.

Beyond its material basis, color functions as a cultural and symbolic element [

28]. In Chinese villages, for example, red signifies auspiciousness, prosperity, and festivity, while white is associated with mourning [

29]. Such symbolic codes are deeply embedded in rituals, festivals, and everyday practices.

The color schemes of built heritage thus embody regional differences. Since construction materials were usually locally sourced, they determined the chromatic tone of each village. Aesthetic harmony is also evident: the palettes of ancient villages often resonate with their natural surroundings, creating a sense of coherence. This can be observed in the subdued tones of desert settlements or the vivid hues of coastal villages [

30]. In contrast, the colors of Hebei’s ancient villages are characterized by rustic warm yellows, earthy browns, and muted greenish greys, producing a palette that is both simple and regionally distinctive.

PT9 (September 2024) considers that:

“One of the characteristics of the ancient villages in Yu County, Hebei Province, is simple and heavy, and the colors of many ancient buildings are mainly grey and brown, reflecting the vicissitudes of history. However, bright colors embellish some detailed decorations, such as the colorful paintings on the doors and windows, which are colorful and symbolic. This contrast and matching of colors echo, to a certain extent, the color characteristics of shadow art, which also highlights the key points and expresses the theme through bright colors on an ancient base.”

PT8 dicussed the color characteristics (September 2024):

“The ancient villages in Yu County are all village fortresses and castles with military defense functions, and there are theatres, Taoist pavilions, and Buddhist temples in every village. In terms of color, there are still preserved murals from the Ming Dynasty period, roughly the same as the color characteristics of the paper cuttings in Yu County County.”

In contrast, the ancient villages of Hebei present a markedly different chromatic identity. Constructed largely from indigenous stone materials such as red slate, green bricks, and grey tiles, their architectural palette is dominated by warm yellows, deep ochres, earthy browns, muted greys, and occasional vivid scarlets. Unlike the “white walls and black tiles” that characterize Jiangnan [

31] and Anhui [

32], the chromatic spectrum of Hebei villages conveys a sense of solidity, austerity, and resilience, reflecting both the natural environment and the pragmatic lifestyles of northern communities.

These chromatic characteristics also embody symbolic and cultural meanings. The subdued and weighty tones resonate with the harsh northern climate and the cultural values of simplicity and endurance, while the striking decorative elements—such as bright red couplets and lanterns—introduce vivid accents of celebration and auspiciousness. Together, they form a distinctive “northern palette” that not only differentiates Hebei’s ancient villages from their southern counterparts but also serves as a visual expression of local identity and collective memory [

33].

3.3.2. Theme 2: Symbolic Colors in Shaping Cultural Identity

Building on Proshansky’s place identity theory [

34] and Hall’s cultural identity framework [

35], this study interprets color as a medium of symbolic communication [

36], which conveys cultural meanings and strengthens regional identity in Hebei’s ancient villages.

The color of ancient villages in Hebei is not merely a visual phenomenon, but a comprehensive reflection of culture, history, and the natural environment. It embodies rich cultural symbolism and expresses the harmonious coexistence between humans and nature. As Cosgrove have noted, color is a crucial medium in shaping cultural landscapes, contributing to place identity, community cohesion, and the preservation of historical narratives [

37].

The interviews further highlighted the symbolic and cultural significance of color in Hebei’s ancient villages. As PT1 interviewee stated: “The warm colors and staggered street layout create a unique regional atmosphere.”

Similarly, PT2 emphasized the intergenerational transmission of color symbolism, He stated: “red couplets and lanterns are not just decorations; they are passed down from our ancestors to remind us of good fortune and unity.”

PT7 underscored the relationship between color and place identity: “when people see the warm yellow walls and dark grey roofs, they immediately know it is our village.”

Taken together, these narratives suggest that color functions as a cultural medium that links materiality, symbolism, and identity. It strengthens community cohesion while also serving as a marker of regional distinctiveness.

This research explores the primary color elements and their symbolic meanings in the ancient villages of Hebei, with a particular focus on the unique tones of these areas and their cultural relevance. The findings indicate that warm reds and yellows constitute the dominant chromatic elements, while ochre and brown tones prevail in the architectural environment. These tones derive from the use of local building materials, especially natural stones such as red slate and green brick, and are reinforced by a rough and bold construction style that together create a chromatic aesthetic harmonizing with the surrounding landscape. The interaction between local materials, cultural narratives, and color expression ultimately shapes a distinctive regional aesthetic language.

To investigate the primary color elements and their symbolic meanings in ancient villages of Hebei Province, with a focus on the unique color tones of these areas and their cultural relevance. The study found that the primary color elements in ancient villages of Hebei Province include warm red and yellow, while ochre and brown tones dominate the architectural environment. These tones represent the local building materials, primarily natural stone, such as red slate and green brick, creating a rural aesthetic that harmoniously blends with the surrounding landscape.

Additionally, the chromatic tones of these ancient communities carry profound symbolic meanings. Certain hues signify auspiciousness, prosperity, and festivity, while others are embedded in historical and cultural traditions, including folk art and traditional festivals. Decorative elements—such as lanterns, couplets, paper cuts, and New Year paintings—employ vivid colors that stand in sharp contrast to the subdued tones of the architecture, thereby amplifying the symbolic and cultural significance of color. This intentional use of chromatic contrast not only defines the visual identity of these settlements but also embodies deeper cultural narratives, environmental adaptation, and historical continuity.

In summary, the colors of ancient villages not only shape a distinctive aesthetic atmosphere and collective sense of belonging at the spatial level but also, through the symbolic meanings embedded in folk art, reinforce regional cultural connotations and color identity, thereby serving as a crucial medium in constructing local cultural identity.

3.3.3. RQ3: Formulation of the Colour Model for Preservation and Sustainable Development

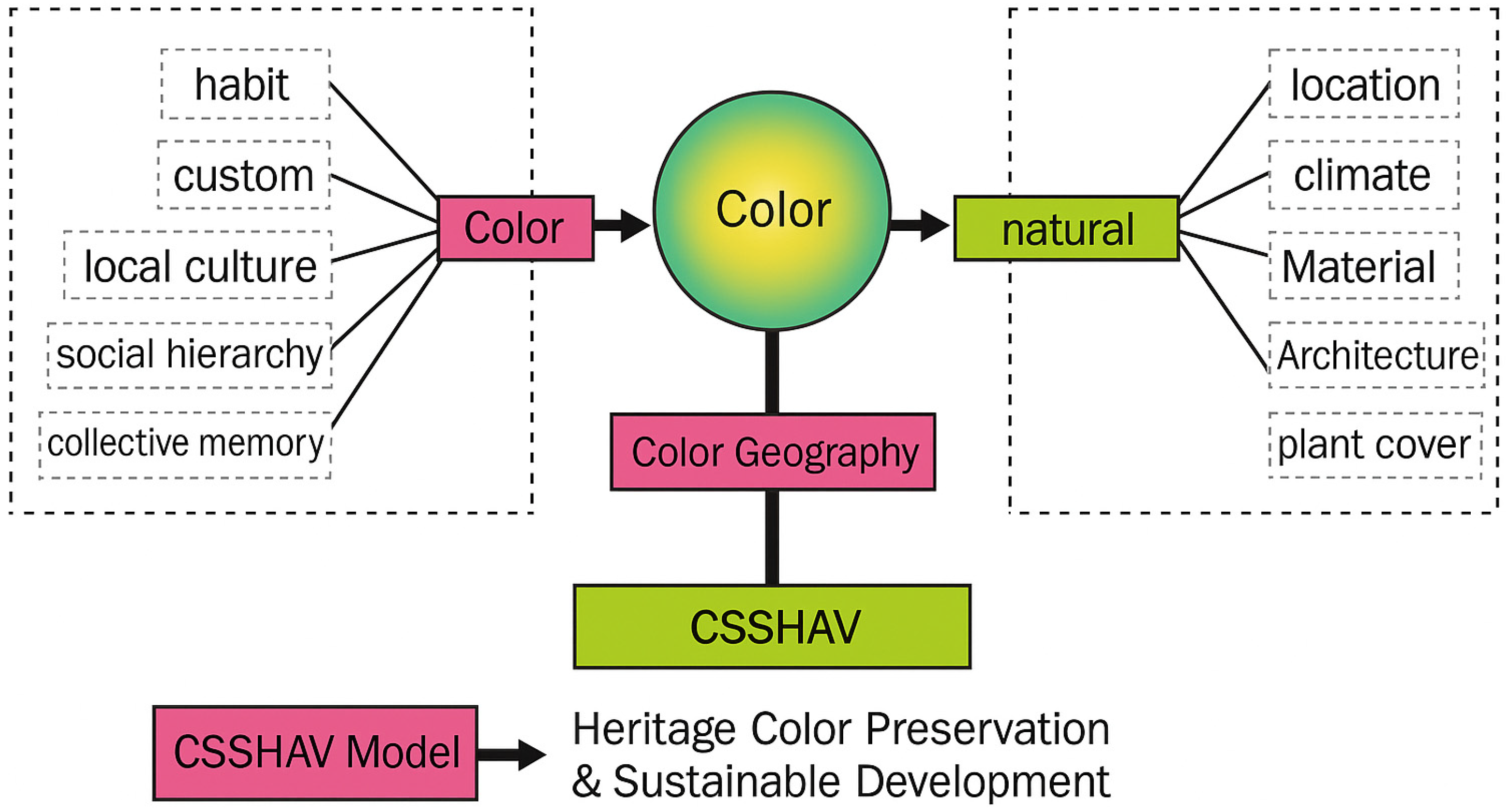

This study formulates the Colour Symbol System for Hebei Ancient Villages (CSSHAV) as an integrated framework that unites quantitative colour analysis and qualitative cultural interpretation. The model originates from the systematic investigation of the dominant chromatic attributes and their symbolic meanings observed in Hebei’s ancient villages.

The findings reveal that warm reds and yellows form the core chromatic spectrum, while ochre and brown tones prevail across the architectural environment (see

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12). These hues are derived from locally sourced materials such as red slate, green brick, and timber, whose natural texture and weathered surface generate a rustic and harmonious aesthetic consistent with the regional landscape. The interaction between local materials, folk-art traditions, and colour symbolism collectively shapes a distinctive regional aesthetic language that visually expresses Hebei’s northern cultural identity.

Beyond their material origins, these colours also embody profound cultural and ritual significance. Bright reds and golds are traditionally associated with auspiciousness, vitality, and communal celebration, whereas the subdued ochres and browns convey stability, humility, and endurance. Decorative elements—such as lanterns, couplets, paper-cuts, and New Year paintings—use high-chroma tones to contrast sharply with the muted architectural base, amplifying both visual distinctiveness and symbolic resonance (see

Figure 17). This contrast demonstrates how colour mediates between tangible architecture and intangible cultural meaning, anchoring heritage identity through chromatic differentiation.

Building upon these empirical and interpretive findings, the CSSHAV translates chromatic characteristics into a systematic conservation and management model that informs both heritage protection and sustainable rural development. The system is composed of four interrelated components:

Regional Colour Taxonomy—Establishes defined ranges of hue, lightness, and chroma for key architectural components (walls, roofs, doors, barriers, decorations) to ensure visual harmony and prevent colour homogenisation.

Material–Colour Coupling Guidelines—Links specific COLORO codes to corresponding local materials (stone, wood, brick), guaranteeing authenticity, durability, and ecological compatibility.

Cultural and Spatial Differentiation Rules—Preserves the symbolic contrast between ritual/religious and residential/domestic spaces through calibrated chromatic intensities and hierarchical coding.

Digital Colour Database and Application Tools—Provides a standardised platform for restoration, design control, and sustainable tourism branding, ensuring colour consistency across conservation and revitalisation practices.

By integrating digital precision with interpretive depth, the CSSHAV bridges the gap between scientific measurement and cultural meaning, offering a replicable framework that guides both theoretical understanding and practical implementation. The model reinforces the regional chromatic identity of Hebei’s villages, ensuring that colour continues to serve as a dynamic cultural resource that supports heritage continuity, community cohesion, and sustainable revitalisation.

In summary, the combination of quantitative colour analysis and qualitative interview findings reveals the interdependence between cultural cognition and material colour expression in Hebei’s ancient villages. The impressions frequently mentioned by interviewees—such as warmth, tradition, and festivity—closely correspond to the dominant hues and tones of façades and decorative elements, indicating that the village colour system is culturally driven rather than random. Ultimately, the colour palette of Hebei’s ancient villages not only defines a distinctive aesthetic atmosphere and collective identity, but also provides a strategic foundation for balancing heritage preservation with innovation and sustainable development in northern China’s rural environments.