1. Introduction

Prefabricated construction is a significant trend in the construction industry, necessitating a shift toward industrialized practices. Due to conventional contracting models, most prefabricated building projects in China still follow a fragmented management approach, separating design from construction. This results in insufficient coordination across key stages such as design, procurement, and construction, leading to slow project progress, communication difficulties, low resource integration efficiency, and challenges in ensuring construction quality. The Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) model integrates design, procurement, and construction into a unified framework, enabling efficient resource integration across the industrial chain, clarifying responsibilities, and optimizing project management. In prefabricated construction, the EPC model facilitates design optimization, rationalized equipment procurement, and scientific scheduling of construction activities, thereby enhancing project efficiency and improving construction quality. However, the EPC model also presents challenges, including extended project durations, technical complexity, and exposure to numerous force majeure factors. Information asymmetry between project owners and general contractors, coupled with varying management capabilities, increases the difficulty of cost adjustments and claims, placing a greater burden of risk on general contractors. As a result, the potential risks associated with EPC-based prefabricated construction continue to expand, making the precise and effective assessment of these risks a critical issue.

Researchers highlighted that the inherent risks in the prefabricated construction supply chain impact project completion rates [

1]. Using grounded theory, they identified risks, developed a comprehensive risk framework covering all project phases, and employed an interpretive structural model (ISM) to analyze the relationships between risk factors. Pervez et al. assessed key risk factors in modular construction, selecting 20 risks from the literature and applying the fuzzy Delphi method to identify the most critical ones [

2]. They then used the Full Consistency Method (FUCOM) to prioritize these risks. Shen et al. explored the application of Revit software in monitoring prefabricated construction processes [

3]. Through case studies, they validated its effectiveness in enabling visualized management and decision support for construction safety risks. Wuni et al. argued that Modular Integrated Construction (MiC) represents a significant advancement over traditional construction methods [

4]. They evaluated 15 on-site assembly (OA) risk factors in MiC projects, assessing their severity based on the interplay between factory production and on-site assembly. Li and Jing conducted a bibliometric analysis using CiteSpace on 385 papers from the CNKI database (2010–2020), uncovering research trends and key topics in EPC project management [

5]. The study indicated growing academic attention in this field. Wu performed an in-depth analysis of contract risk management in EPC projects, finding that research primarily focuses on risk management in the early stages, implementation phase, and post-project completion [

6]. Wang et al. categorized EPC project risks into five types: contract, design, procurement, construction, and external environment [

7]. Using structural equation modeling (SEM), they conducted both qualitative and quantitative analyses on the Zhijiang Expressway project, identifying contract-related risks as the most critical. Fan et al. developed a hierarchical framework for prefabricated construction schedule risks from the perspective of general contractors [

8]. They identified 22 schedule risk factors, structured them using the ISM, and classified risks based on driving and dependency forces using the impact matrix technique. Cao and Lei evaluated risks in prefabricated construction under the EPC model and proposed mitigation strategies. By conducting factor analysis with SPSS 22.0, they identified four primary indicators and 14 secondary indicators to quantify the impact of various factors on construction risks [

9]. Xia et al. employed a gray-fuzzy theory model from a general contractor’s perspective, validating it through a case study in Nanjing. Their research identified the construction and design phases as the critical factors influencing project risk levels [

10]. Li, in a study on large-scale engineering projects, concluded that project failures are often attributable to failures in organizational coordination and process management, rather than purely technical challenges [

11]. Yang and Wang emphasized the decisive impact of design-phase decisions on the cost and schedule of prefabricated construction projects [

12].

The aforementioned studies have established risk indicator systems from various evaluation perspectives and employed dynamic fuzzy theories and mathematical models to quantitatively analyze project risks. However, existing research has several limitations. Firstly, while the chosen mathematical model has been applied in risk assessment across various project domains, its specific application in prefabricated construction EPC projects remains limited. Secondly, within existing studies that employ this model, most tend to focus on isolated phases of the construction process, such as design, procurement, or construction, with comprehensive risk assessments spanning the entire project lifecycle being scarce. Thirdly, these studies predominantly evaluate risks related to a single project element, such as quality, safety, or cost, while integrated assessments that consider all critical elements are notably underdeveloped. To address these gaps, this study employs literature review and case analysis to effectively identify risks in prefabricated construction EPC projects. It integrates the Analytic Network Process (ANP) with Gray Clustering Analysis to develop a comprehensive risk assessment model that combines Gray Clustering Analysis with Fuzzy Evaluation. This approach not only captures the interdependencies among risk factors but also accounts for uncertainty and ambiguity in the assessment process. The proposed model is applied to a real-world case study of an EPC-based Prefabricated Buildings project (named as Project A) in Southwest China, validating its rationality while simultaneously determining the risk level of prefabricated construction EPC projects and providing insights for construction practices.

3. Construction of the ANP–Gray Clustering Analysis Risk Evaluation Model

The Analytic Network Process (ANP) is a decision-making method proposed by Saaty. It is an extension of the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). Unlike AHP, which emphasizes a unidirectional hierarchical structure, ANP incorporates interdependencies between risk factors and feedback loops among decision elements. This allows for a more accurate representation of internal relationships and the resolution of complex nonlinear problems [

14]. Gray Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation, proposed by Professor Deng, is a method used to assess fuzzy factors or uncertain phenomena under conditions of limited information. Based on fuzzy mathematics, this approach quantifies qualitative factors and evaluates their membership levels within a given classification. The whitening weight function, a core component of Gray System Theory, is used to characterize the degree of preference for different values within a gray number’s range. This enables a quantitative description of how data points belong to specific gray classes [

15].

This study adopts the ANP–Gray Clustering Analysis model to evaluate the risks associated with EPC-based prefabricated construction projects for the following reasons: (1) Interdependencies Among Risk Factors: Risks in EPC-based prefabricated construction are not only hierarchical but also interrelated across and within different levels of indicators. (2) Superiority Over AHP: Compared to AHP, ANP leverages a “supermatrix” to more effectively determine the mixed weightings of risk factors in EPC-based prefabricated construction. (3) Handling Gray and Fuzzy Characteristics: Due to the long construction cycles of EPC-based prefabricated projects, most risk indicators are qualitative rather than quantitative. The assessment of these risks relies heavily on expert judgment, and the relationships among risks and their contributing factors are often unclear. This results in high degrees of uncertainty and fuzziness in the risk evaluation framework [

16].

Therefore, the ANP–Gray Clustering Analysis model is well-suited for evaluating risks in EPC-based prefabricated construction. This model not only accounts for the interconnections among risk indicators and their combined effects but also effectively addresses fuzziness and uncertainty in the risk evaluation process.

3.1. Determining Indicator Weights Based on ANP

3.1.1. Establishing the ANP Network Structure

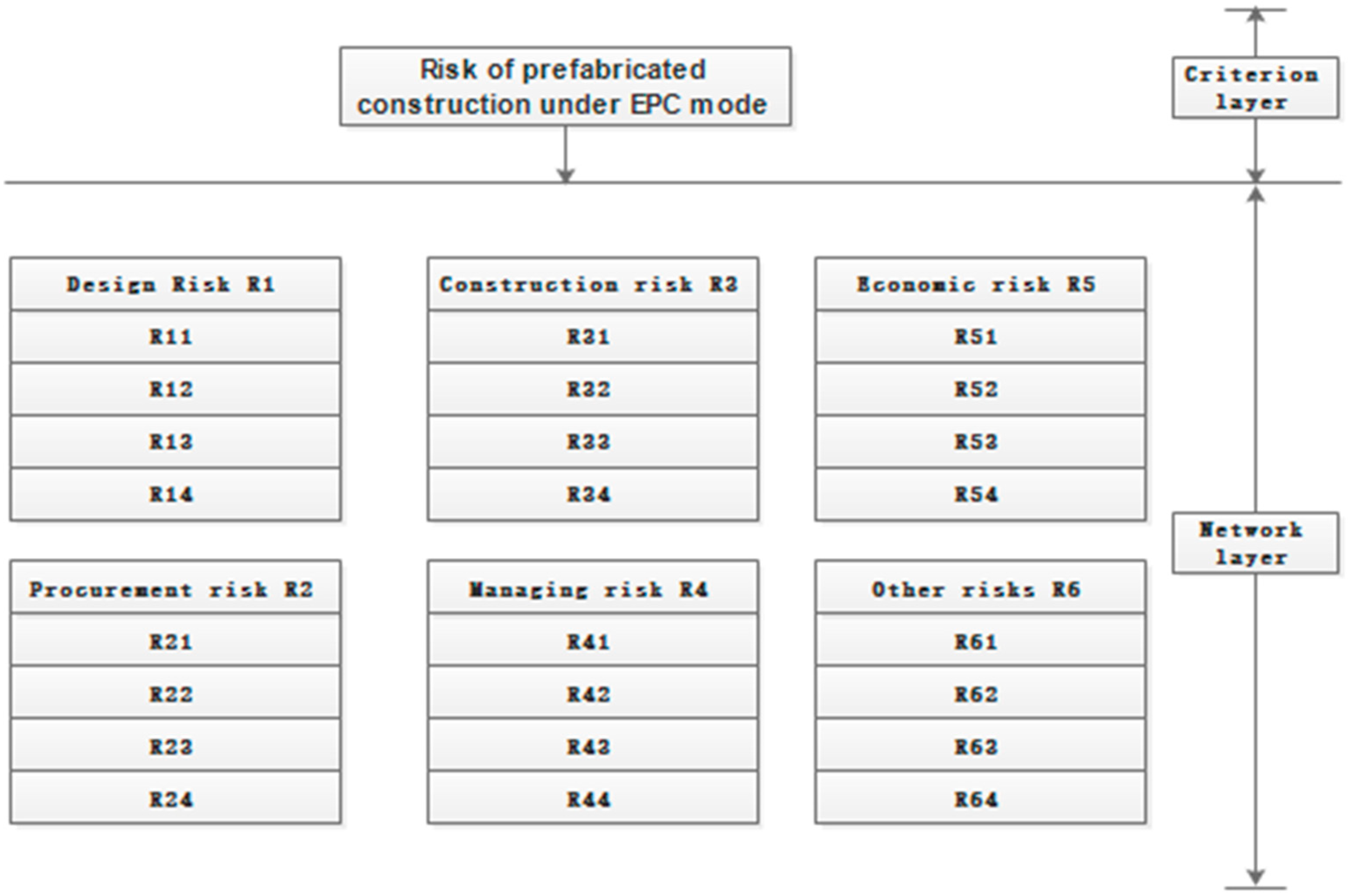

Following the principles and implementation steps of ANP, a pairwise comparison of the dependent elements is required. This study applies an indirect dominance approach to compare risk factors within the network. Given a set of evaluation criteria, two risk factors are compared based on their impact on a third risk factor. ANP divides system elements into two main components [

17]:

- 1.

Control Layer: Defines the evaluation objective, which in this study is the risk assessment of EPC-based prefabricated construction projects. The key decision criteria include Probability of risk occurrence, Severity of risk consequences, and Controllability of risk factors.

- 2.

Network Layer: Defines the risk factor set, corresponding to the primary indicators in the EPC risk assessment framework, which includes Design Risk (R1), Procurement Risk (R2), Construction Risk (R3), Management Risk (R4), Economic Risk (R5), and Other Risks (R6).

Each risk category consists of multiple secondary risk indicators. Based on this structure, an ANP-based risk assessment model for EPC-based prefabricated construction is developed, as shown in

Figure 1.

To ensure the professionalism and reliability of the research data, a panel of 20 seasoned industry experts was invited. The selection criteria for these experts were as follows: (1) employment by a general contracting enterprise; (2) over 15 years of relevant industry experience; and (3) direct responsibility for managing at least one complete prefabricated building EPC project. The panel had an average of 18 years of professional experience, with expertise spanning key areas including project management, structural design, construction technology, cost control, and procurement logistics, as detailed in

Table 6.

To establish the relationships among risk factors, all 20 experts of the expert group were consulted through structured interviews. They were asked to identify feedback loops within risk groups and interdependencies between different risk categories. If more than 10 experts agreed on a causal relationship, it was retained in the model; otherwise, it was excluded. This process resulted in the EPC prefabricated construction risk factor relationship matrix, presented in

Table 7. In

Table 7, a value of “1” indicates the presence of an influence between two elements, whereas elements are assumed to have no self-impact. The direction of influence is represented by the row affecting the column.

3.1.2. Constructing the Unweighted Supermatrix W

Based on the questionnaire method, experts were invited and indirect dominance comparison method was adopted. Under the P

i criterion, the risk element R

ini in R

i was compared by indirect dominance according to its influence on the risk element R

jnj in R

j [

18], that is, the pair-to-two comparison was made according to the scale defined in

Table 8.

Then the judgment matrix is constructed under the P

i criterion, as shown in

Table 9.

According to the formula, the consistency test is carried out on the judgment matrix. If CR ≤ 1.0, the judgment matrix passes the consistency test [

19].

The eigenvector (

,

, …,

) after the normalization of the judgment matrix constitutes an unweighted hypermatrix W under the P

i criterion, whose column vector is the risk element in R

i (R

i1, R

i2, …, R

ini) for risk elements in R

j (R

j1, R

j2, …, R

jnj) impact ranking vector.

Note: A key component of ANP is the Supermatrix, which is a partitioned matrix that captures all the pairwise influence relationships within the network of risk factors.

3.1.3. Construct the Weighted Supermatrix

On the basis of unweighted supermatrix and Pi criterion, the risk factor set R

i (i = 1, 2, …, N) for the set of risk factors R

j (j = 1, 2, …, N) importance judgment matrix, that is, the weighted matrix is obtained by comparing the indirect dominance degree of the risk factor set Ri according to its influence on the risk factor set R

j, as shown in

Table 10. Since there are m criteria, there are m such supermatrices, and they are all non-negative matrices [

20].

The ordering vector corresponding to the group of elements independent of R

j has a component of 0, thus obtaining the weight matrix C.

Weighting the elements of the hypermatrix W gives

= CW, and

is the weighted hypermatrix whose column vectors sum to 1.

3.1.4. Construct Limit Supermatrix

The weighted super matrix is normalized, and then the limit super matrix W

∞ is obtained, whose column vector is the weight vector W′ of risk factor R

ini.

3.1.5. Determine the Total Weight of Risk Indicators

Using criteria (P1, P2, …, Pm) repeats the above process and then synthesizes the weight of elements under each criterion to obtain the total weight of risk factors.

3.2. Determination of Evaluation Criteria and Whitening Weight Functions

To comprehensively assess the overall risk level of the project, we employed Gray Clustering Analysis. “clustering” refers to the process of classifying the project’s risk profile into predefined categories (e.g., Low, Medium, High) based on its gray relational degree to each category. The core of this method is the construction of whitening weight functions, which mathematically define the membership of a quantitative value to a specific qualitative risk category. Essentially, these functions describe how “belonging” a certain score is to a “High Risk” or “Low Risk” group, handling the ambiguity inherent in such classifications. Therefore, the gray clustering evaluation belongs to a kind of fuzzy evaluation.

In this study, the project risk level is divided into 5 levels, which are “very low”, “lower”, “medium”, “higher” and “very high” according to the probability of risk occurrence, loss severity and controllability from low to high. The value range of the risk measure is expressed by the interval number [0, 10] [

21], and its review set and evaluation criteria are shown in

Table 11.

The rationality of gray class classification directly affects the accuracy of risk assessment for EPC-based prefabricated construction projects. Based on the unique characteristics of these projects, the gray classes are categorized into five levels: Very Low, Low, Medium, High, and Very High, with corresponding values of 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9, respectively. Building upon previous studies and considering the specific risk characteristics of EPC-based prefabricated construction, this study develops whitening weight functions for each gray class, as shown in

Table 12. These functions enable quantitative risk assessment by defining the degree of membership of a given risk factor within each gray category.

3.3. Calculation of Grey Evaluation Coefficients and Weight Matrix

3.3.1. Establishing the Sample Matrix

A panel of 15 seasoned industry experts was invited to conduct the pairwise comparisons. This sample size aligns with the established practice in multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) research, where the validity stems from the high caliber of the experts rather than the cohort’s size. All selected experts were from general contracting enterprises, with an average of over 15 years of professional experience and specific expertise in prefabricated EPC projects. The scoring criteria are defined as follows: The scoring range is 0–9, where 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 represent risk levels Very Low, Low, Medium, High, and Very High, respectively, while 2, 4, 6, and 8 indicate intermediate levels between the predefined categories. Based on expert evaluations, a sample matrix is constructed to facilitate further analysis.

3.3.2. Calculation of Gray Evaluation Coefficients

y

ije is used to represent the gray evaluation coefficient of class e evaluation gray, then:

where t is the number of experts.

By synthesizing the five gray values, the total gray evaluation coefficient y

ij was obtained.

3.3.3. Calculation of the Gray Evaluation Weight Matrix

C

ije is used to represent the gray evaluation power of category e evaluation grey [

22], then:

In this paper, the gray class is determined into 5 grades, and the evaluation weights of each gray class are synthesized to obtain the gray evaluation weight vector C

ij = (C

ij1, C

ij2, C

ij3, C

ij4, C

ij5), and then the gray evaluation weight matrix C is obtained [

23].

3.4. Multi-Level Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation

Firstly, the gray evaluation weight matrix C

i is evaluated comprehensively. Multiply the weight vector Hi of the 2-level index layer with its corresponding gray evaluation matrix C

i, and the evaluation result is represented by B

i [

24], then:

The gray evaluation weight matrix B of the 2-level index layer is obtained.

Secondly, the gray evaluation weight matrix B is evaluated comprehensively. Product the weight vector S of the first-level index layer with its corresponding grey evaluation matrix B, S = (s

1, s

2, …, s

i), the evaluation result is represented by A [

25]; then:

Finally, the 5 grades divided by gray are assigned according to “gray level”, and the value vector of gray grade is represented by U, that is, U = (9, 7, 5, 3, 1), and the gray comprehensive evaluation value is obtained [

26]:

The calculated result corresponds to the evaluation level to determine the risk level of the project.

4. Empirical Analysis

To validate the rationality and effectiveness of the constructed gray fuzzy comprehensive evaluation model, Project A was selected as a case study. This project involves the construction of a new middle school in Chengdu, Southwest China. Project A has a total investment of 200 million CNY, with a site area of 30,521.04 m2 and a total floor area exceeding 40,000 m2. It utilizes prefabricated construction with a prefabrication ratio exceeding 33%. The structural system adopts a prefabricated frame structure combined with partially cast-in situ beams and slabs, with main prefabricated components including composite beams and composite slabs. The project employs the EPC turnkey model under a lump-sum contract, with a planned total duration of 24 months.

The selection of this case was guided by its representativeness in Southwest China. Project A is a public building utilizing precast concrete structure under the EPC model, with its floor area, investment scale, and technical requirements ranking medium to high among similar projects in the region, ensuring strong typicality. This makes the research findings highly relevant for future analogous projects. Furthermore, the research team maintained close collaboration with the general contractor, enabling access to comprehensive data across the entire project lifecycle—from decision-making and design to production and construction—and facilitating interviews and surveys with core management personnel. This cooperation robustly guaranteed the authenticity, comprehensiveness, and depth of the case data. Given the large-scale construction and the complex risk landscape, the ANP–Gray Clustering Analysis model was applied to determine the risk level of this project.

4.1. Construction of the Risk Indicator System

Based on the literature analysis method and case study method, a list of risk factors was initially identified. To further refine this list, a questionnaire survey was conducted, inviting professionals from relevant organizations to evaluate and filter the risk indicators. The collected data was analyzed using SPSS 22.0 statistical software, which helped eliminate relatively insignificant risk factors, thereby refining the final risk factor list. The constructed risk indicator system is presented in

Table 5.

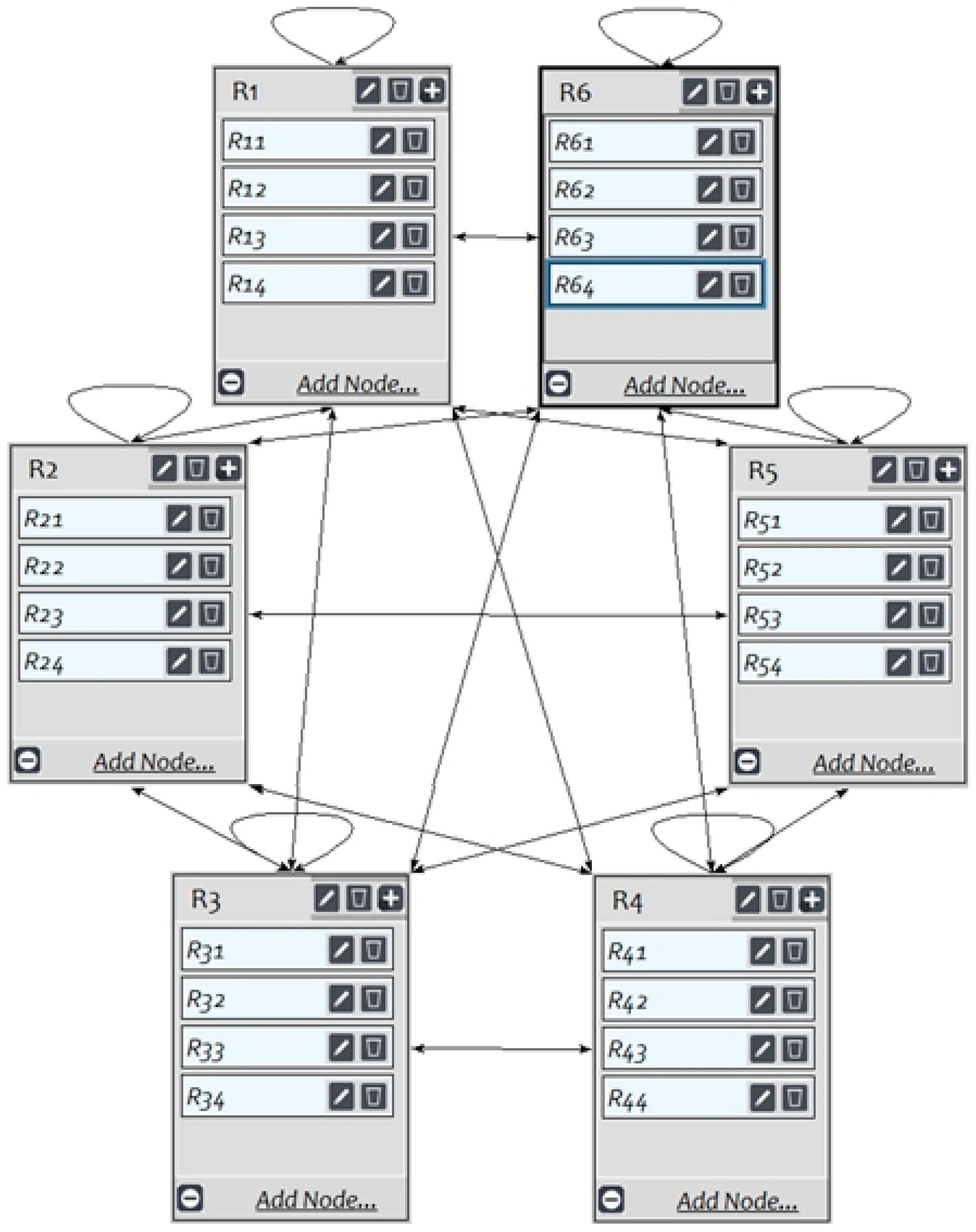

4.2. Determination of Risk Indicator Weights

Using

Table 7, which illustrates the independence, dependence, and feedback relationships among risk factors, the SuperDecisions 3.2 software was employed to construct a risk network diagram for EPC-based prefabricated construction projects using ANP, as shown in

Figure 2.

After establishing the ANP network structure, the SuperDecisions 3.2 software automatically generated the pairwise comparison judgment matrices for risk factors. A questionnaire survey was conducted with industry experts, who provided evaluations using the indirect dominance comparison method based on the 1–9 scale method (as shown in

Table 8). The pairwise comparison judgment matrices for both primary and secondary risk indicators are depicted in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. In total, this study constructed six pairwise comparison matrices for primary indicators and 24 matrices for secondary indicators.

Since expert evaluations involve subjectivity, it was necessary to conduct a consistency test on the risk factor comparison matrices. Upon inputting the importance relationship matrices, the SuperDecisions 3.2 software automatically calculated the consistency ratio (CR). Based on Equations (1) and (2), the matrices were tested for consistency, and if CR ≤ 0.1, the judgment matrix was deemed to have passed the consistency test. Any matrix with a CR value exceeding the threshold of 0.1 was deemed inconsistent and was returned to the respective expert for revision until the CR criterion was met. This process guaranteed the logical reliability of all expert judgments utilized in the model.

In the ANP network of this study, the three control criteria—Probability (P), Severity (S), and Controllability (C)—together with the risk clusters and risk indicators in the network layer, form an interactive feedback system. In SuperDecisions 3.2, the relative importance of the control criteria is not derived from an independent comparison matrix. Instead, pairwise comparisons involving the control criteria and all other elements in the network are incorporated together. Through the synthesis of the weighted supermatrix and the calculation of its limit, the global weights of all elements—including the control criteria—relative to the overall goal are ultimately determined. Additionally, the software performs consistency checks on all input pairwise comparison matrices, including those involving the control criteria.

Using SuperDecisions 3.2, the unweighted supermatrix, weighted supermatrix, and limit matrix for the ANP risk indicator system were generated, and the weights of risk indicators were determined. The impact of each risk factor on EPC-based prefabricated construction risk was analyzed based on these weights, as shown in

Table 12.

From

Table 13, the weight vector S for the overall risk R in EPC-based prefabricated construction projects and the weight vectors H

1, H

2, H

3, H

4, H

5, and H

6 for each primary risk category are as follows:

4.3. Determination of Evaluation Gray Categories and Whitening Weight Functions

4.3.1. Establishing the Risk Evaluation Sample Matrix

A subgroup of 15 experts from the original panel was invited to participate in a questionnaire survey. Selected for their geographical proximity to and deep familiarity with the case project, these experts assessed the risk level of Project A based on pre-established risk assessment grading criteria. The risk levels were classified into five categories, ranging from “Very Low” to “Very High”, based on three key criteria: risk occurrence probability, severity of loss, and controllability. The risk measurement scale is represented by an interval range of [0, 10], as detailed in

Table 11.

Upon collection of the expert ratings, a statistical consistency check was performed using the Coefficient of Variation (CV). The CV, calculated as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean (CV = Standard Deviation/Mean), quantifies the relative dispersion of the scores for a given risk indicator. A high CV value signifies significant divergence in expert opinions. Any risk indicator with a CV value exceeding the pre-defined threshold of 0.5 across the 15 experts was flagged for review. In such instances, the divergent scores were referred back to the respective experts for re-evaluation, allowing them to confirm or revise their initial judgments based on group feedback. This iterative process continued until all CV values fell below the 0.5 threshold, thereby ensuring a satisfactory level of consensus and data stability for subsequent analysis. Based on the finalized data, a sample matrix for risk assessment of prefabricated construction projects under the EPC model was constructed. For further details, please refer to

Table 14.

4.3.2. Calculation of Gray Evaluation Coefficient

Taking the second-level indicator R

11 as an example, the expert evaluation scores were substituted into the corresponding gray whitening weight functions, and the calculated results are presented in

Table 15. The whitening weight functions for each gray category are detailed in

Table 11.

According to Formula (3), calculated risk indexes R11 corresponding to five gray evaluation coefficients are 5.0000, 6.4286, 8.6000, 10.3333, and 2.0000, respectively.

According to Formula (4), the total gray evaluation coefficient yij = 32.3619 was calculated.

4.3.3. Calculation of Gray Evaluation Weight Matrix

According to Formula (5), the evaluation weights of each gray category are integrated to obtain the gray evaluation weight vector C11 = (0.1545, 0.1986, 0.2657, 0.3193, 0.0618) corresponding to the risk index R11.

Similarly, the gray evaluation weight vector of other risk indicators can be calculated. Finally, the gray evaluation weight matrix C

1 corresponding to the first level index R

1 is obtained.

Similarly, the gray evaluation weight matrices C

2, C

3, C

4, C

5 and C

6 corresponding to the first-level indicators R

2, R

3, R

4, R

5 and R

6 can be calculated using the above calculation method.

4.4. Multi-Level Fuzzy Comprehensive Evaluation

4.4.1. Comprehensive Evaluation of First-Level Indicators

Given the weight vectors H

1, H

2, H

3, H

4, H

5, H

6 of the six first-level indicators and the corresponding gray evaluation weight matrix C

1, C

2, C

3, C

4, C

5, C

6, the gray evaluation weight vectors B

1, B

2, B

3, B

4, B

5, B

6 corresponding to the six first-level indicators can be calculated according to Formulas (6).

Then the gray evaluation weight vector B corresponding to EPC prefabricated construction project risk R is:

4.4.2. Comprehensive Evaluation of Project Risk

Given that the weight vector of risk R of EPC prefabricated construction projects is H and the corresponding gray evaluation weight vector B, the final comprehensive evaluation weight vector A can be calculated according to Formula (7).

4.4.3. Calculation of Gray Comprehensive Evaluation Value

The five gray grades are assigned based on the “gray level”, and the gray grade value vector is represented as U, where U = (9, 7, 5, 3, 1). Using Formula (8), the comprehensive risk evaluation value for EPC prefabricated construction projects is computed as follows:

Following the same approach, the risk evaluation values corresponding to the six primary indicators were calculated as follows:

4.5. Analysis of Evaluation Results and Discussions

According to

Table 11, the comprehensive risk evaluation value G of Project A was mapped against the risk evaluation set and standard criteria for EPC-based prefabricated construction projects. The evaluation value was found to be 5.072, placing Project A in the “Moderate” risk level. The comprehensive evaluation value G = 5.072 is a precise and continuous scalar output derived from the synthesis of ANP weights and gray clustering calculations. This value unambiguously falls within the pre-defined “medium risk” interval. The assigned risk level is an objective outcome resulting from the sensitive model’s precise computation and clear discrimination of the project’s risk characteristic data. It reflects the project’s authentic state, where the overall risk profile is neither at the safe extreme nor at the critical danger extreme.

To determine the risk severity of primary indicators, the corresponding risk evaluation values (G

1, G

2, G

3, G

4, G

5, and G

6) were ranked from highest to lowest. The ranking results indicate that the risk levels of the primary indicators are as follows, in descending order: Design Risk, Management Risk, Construction Risk, Other Risks, Economic Risk, and Procurement Risk. The results revealed that management and design risks received the highest weights in the overall risk assessment. The results reveal that management and design risks carry the highest weights in the overall risk assessment, a finding that aligns strongly with the outcomes of several recent studies [

10,

11,

12]. Together, these sources consistently highlight that in the complex context of prefabricated EPC projects—regardless of regional or project-specific variations—robust management capability and front-end design quality remain critical for effective risk control.