1. Introduction

Humidity control is a critical factor in Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) systems for maintaining indoor air quality and energy efficiency. High or low humidity levels can adversely affect thermal comfort and health, as well as create optimal environments for dust mite and microbial proliferation, which can subsequently compromise the structural integrity of a home. This study focuses on defining the safe thresholds of relative humidity in residential environments during the cooling season, with particular emphasis on justifying the maximum allowable relative humidity level that avoids health impacts, microbial and pest proliferation, and long-term structural damage.

Humidity is defined as the concentration of water vapor in the air. It can be quantified in various forms, including absolute humidity, relative humidity, specific humidity, humidity ratio, and dew-point. Relative humidity (RH) is the most utilized metric in HVAC systems, representing the percentage of water vapor present in the air relative to the maximum capacity of the air to retain moisture at a given temperature. RH is particularly significant in HVAC systems as it directly correlates with human comfort and indoor air quality. Typically, individuals feel most comfortable within a relative humidity range of 40% to 60%, commonly referred to as the “comfort zone”. This term denotes a condition where in the average individual can remain comfortable without perceiving any alterations in air quality or encountering health issues. However, comfort is subjective and may vary based on multiple factors as indicated by ASHRAE 55-2023—Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy [

1].

Understanding the threshold of RH is essential for promoting thermal comfort and health in indoor environments while understanding the implications on energy usage. Low humidity levels, particularly those at or below 20%, can lead to dry skin and eye irritation, potentially compromising immune system function. While low RH presents a range of health risks, elevated humidity levels can also alleviate certain respiratory issues such as asthma. During the winter months, low temperatures combined with inadequate indoor heating can lead to significantly reduced humidity levels. Conversely, in summer months, excessively high humidity levels can create discomfort, as the body’s ability to cool itself through evaporation diminishes.

High RH can result in excessive moisture, leading to condensation and creating an ideal environment for microbial growth, such as fungi, and viruses, as well as dust mite development and unpleasant odors, which poses health risks. Conversely, low humidity can also lead to health complications by reducing skin moisture and adversely affecting the mucosal linings of the respiratory tract, making it more challenging for the immune system to combat allergens from fungi, viruses, and dust allergens from dust mites [

2].

Accordingly, this study examines the relationship between indoor relative humidity, thermal comfort, health outcomes, and energy usage in residential buildings during the cooling season. Because the relationships examined depend solely on indoor environmental conditions, the results of this study are considered independent of residential building typology and climate zone. The primary focus is on identifying the maximum RH threshold that ensures thermal comfort while minimizing the risks associated with microbial growth, pest proliferation, and structural damage. By defining this upper limit, the study also considers the implications for energy consumption. The objective is therefore to balance human thermal comfort, health protection, and energy efficiency, providing guidance for residential humidity management.

2. Indoor Design Conditions for Residential Buildings

Defining indoor design conditions is fundamental for accurate residential load calculations and HVAC system sizing. This section focuses exclusively on the thermal load parameters used in engineering practice, without extending into health-related recommendations. References such as the ACCA Manual J [

3] and ASHRAE standards [

1,

4] and ASHRAE Handbook [

5] establish standardized indoor design values that balance comfort expectations with practical system performance. These design conditions serve as reference points for consistent HVAC sizing, energy evaluation, and comparative analysis.

In North America, the ACCA Manual J [

3] procedure is the most commonly adopted reference for residential load calculations. Manual J specifies default indoor design temperatures of 75 °F (23.9 °C) dry-bulb for summer cooling and 70 °F (21.1 °C) dry-bulb for winter heating, with a relative humidity assumption of approximately 50% during the cooling season. These values have become industry standards, ensuring comparability across climates and housing types. However, Manual J’s defaults are flexible, humidity targets can be adapted depending on regional climate and construction characteristics. In humid climates, 55% RH may be used to account for additional latent moisture loads, while in arid climates, targets closer to 45% RH are more appropriate [

3].

Complementary perspectives are provided by ASHRAE standards. ASHRAE 55-2023 [

1] defines thermal comfort zones based on combinations of temperature, humidity, air movement, and personal factors rather than prescribing a single pair of conditions. Meanwhile, ASHRAE 62.2-2022 [

4] emphasizes humidity control for moisture management and indoor air quality. ASHRAE standards and literature collectively establish boundaries that guide HVAC design and performance evaluation rather than enforcing fixed setpoints.

In practice, most residential air-conditioning systems achieve dehumidification as a byproduct of cooling, since moisture is removed when warm, humid air contacts the cold evaporator coil. Dedicated humidity control is uncommon in typical homes. Therefore, temperature setpoints—often around 74–78 °F according to energy-saving guidelines—indirectly determine achievable indoor relative humidity levels during operation [

6,

7].

In summary, the Manual J default indoor design condition of 75 °F and 50% RH serves as the benchmark for residential cooling load calculations. ASHRAE standards and literature provide flexibility by defining acceptable comfort and humidity control ranges. Adopting these standardized design conditions ensures comparability across studies and alignment with common industry practice. However, maintaining relative humidity toward an upper end is not prohibited by current standards and, when properly managed, can reduce cooling energy use without compromising occupant comfort, health, or material durability in residential buildings.

3. Relative Humidity and Thermal Comfort

Thermal comfort represents the condition of mind that expresses satisfaction with the thermal environment. One of the most widely accepted quantitative metrics to assess thermal comfort is the Predicted Mean Vote (PMV). The PMV index predicts the mean value of the thermal sensation votes of a large group of people exposed to a specific set of environmental and personal conditions. The scale ranges from −3 (cold) to +3 (hot), with 0 representing a neutral thermal sensation. This metric provides a comprehensive indicator that integrates the effects of air temperature, mean radiant temperature, air speed, humidity, metabolic rate, and clothing insulation.

To examine the specific effect of relative humidity on thermal comfort under typical residential cooling conditions, PMV values were obtained using the CBE Thermal Comfort Tool developed by the Center for the Built Environment (CBE) at the University of California, Berkeley [

8]. In this analysis, all variables other than relative humidity were intentionally held constant, following the operating requirements of the PMV model and the tool interface. Fixing these variables isolates the influence of humidity on PMV at a given dry-bulb temperature, ensuring that the observed trends are attributable solely to changes in RH rather than interactions among comfort parameters.

The following input parameters were used in the analysis:

• Air Temperatures: 74 °F, 75 °F, 76 °F, and 77 °F

• Mean Radiant Temperature: 77 °F (constant)

• Air Speed: 19.7 fpm (constant)

• Metabolic Rate: 1.0 met (fixed)

• Clothing Insulation: 0.61 clo (fixed)

With these parameters fixed, the relative humidity varied across the range of interest, and PMV values were computed for each RH level. This methodological approach, varying one parameter at a time while all others remain constant, is consistent with ASHRAE 55-2023 and allows for a clear and direct interpretation of the PMV response to humidity.

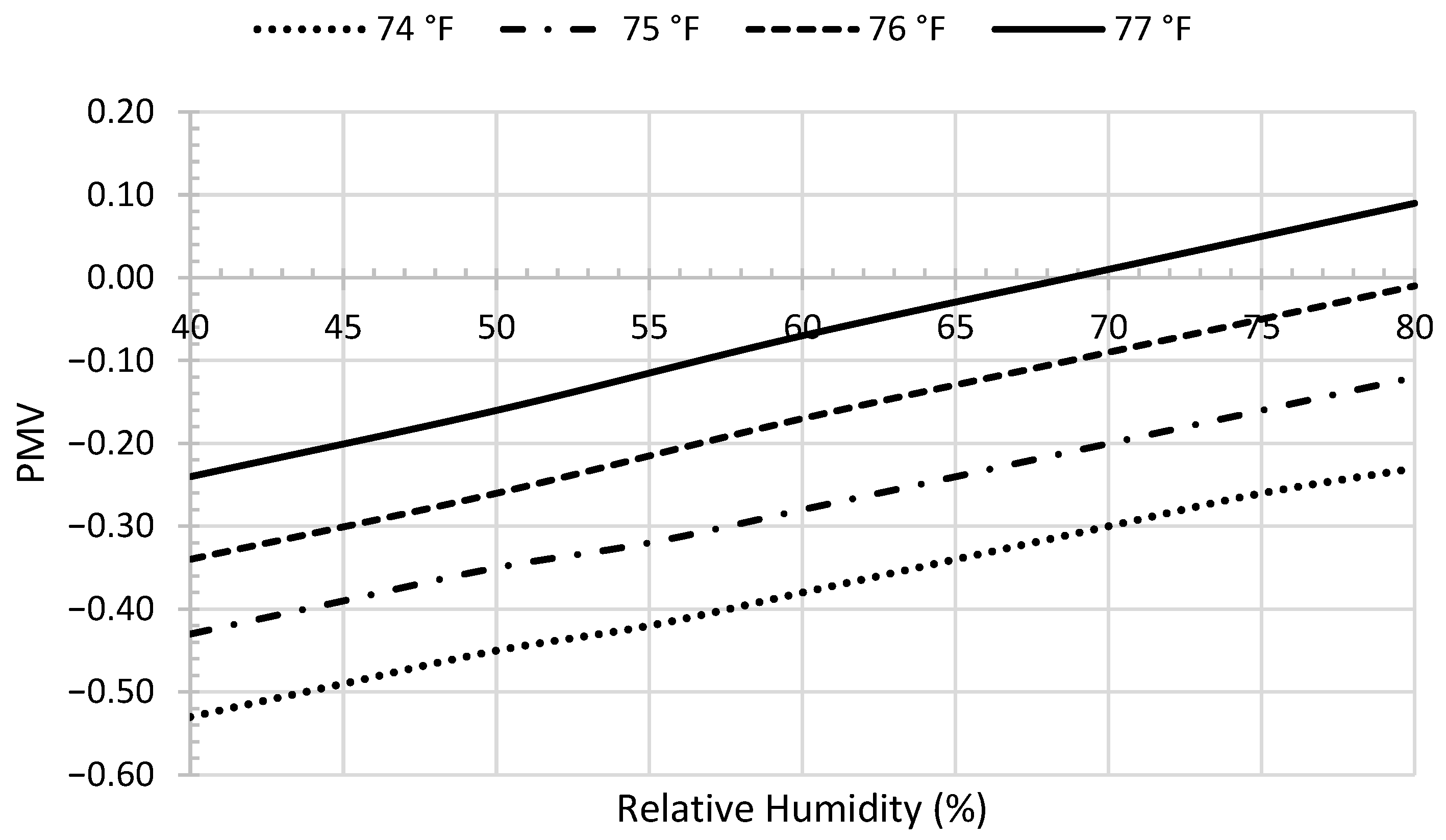

The resulting PMV values, shown in

Figure 1, illustrate how relative humidity influences the predicted thermal sensation under otherwise constant environmental and personal conditions. Across the selected temperature range, the PMV values are negative, indicating a potential cool sensation. As relative humidity increases, the PMV approaches neutral, suggesting an improvement in perceived comfort. Only when the air temperature reaches approximately 77 °F and the relative humidity exceeds 70% does the PMV become positive, indicating a potential shift toward a slightly warm sensation.

Based on the design conditions analyzed, it can be observed that increasing the relative humidity tends to improve thermal comfort within the examined range. Although high humidity is often associated with discomfort in warmer environments, under the moderate temperatures considered here, higher humidity levels help reduce the cool sensation indicated by negative PMV values. This suggests that, within typical indoor design conditions, a moderate increase in relative humidity can enhance comfort or, at minimum, will not compromise it. Consequently, maintaining relative humidity within a balanced range can contribute positively to occupant comfort, particularly when air temperatures are slightly below the commonly adopted indoor design temperatures.

4. Relative Humidity and Energy

The relationship between relative humidity and energy performance in air-conditioning systems can be understood through the influence of indoor wet-bulb temperature on system capacity. Manufacturer performance data commonly show that, for a given set of outdoor and indoor dry-bulb temperatures, the total cooling capacity of an air-conditioning system increases with the indoor wet-bulb temperature. For example,

Table 1 presents performance data for a commercially available system with a rated capacity of 36 kBtu/h, SEER 14, and nominal airflow of 1140 CFM.

Since the wet-bulb temperature rises as the relative humidity of the indoor air increases, higher indoor humidity levels can lead to an increase in system capacity under identical dry-bulb conditions. Although the power input to the system also increases slightly with wet-bulb temperature, the proportional rise in capacity is typically greater. As a result, the system can remove the same total heat load in less operating time, potentially leading to lower overall energy consumption. This counterintuitive behavior suggests that, under certain conditions, moderate increases in indoor relative humidity can enhance system performance efficiency when analyzed over complete operating cycles.

To quantify this effect, a computational model was developed to simulate a hypothetical residential cooling system. The model applies mass and energy balances to a room receiving conditioned supply air from the cooling system and returning room air to the equipment. Equations (1)–(6) define the transient behavior of the room air temperature and humidity ratio. In all equations, subscripts 1 and 2 denote the initial and final state within a time step Δt; subscripts r, s, w, and e refer to room air, supply air, water, and cooling equipment, respectively. T is the dry-bulb temperature, ω the humidity ratio, m the mass of air in the room, the mass flow rate, h and u the enthalpy and internal energy, and the rate of heat transfer, with subscripts T, S, and L denoting total, sensible, and latent components. A property expressed as a function (e.g., ) indicates evaluation at the specified state.

When the cooling system is OFF, the room temperature and humidity ratio at each time step are obtained by solving the room energy balance (Equation (1)) and the moisture mass balance (Equation (2)) simultaneously:

In Equation (2), is the latent heat of evaporation of water.

When the cooling system is ON, the supply air state is first determined by applying the cooling-coil energy and mass balances:

In Equation (3), is the enthalpy of the liquid water, and in Equation (4), is the specific heat a constant pressure of the air.

Once the supply air state

is determined, the updated room air state is computed from:

Equipment performance was modeled using manufacturer-based polynomial curve fits for total capacity (Equation (7)), sensible capacity (Equation (8)), and power input (Equation (9)), all expressed as functions of the room dry-bulb temperature and/or wet-bulb temperature

. The total capacity and sensible heat are in kBTU/h and the power in kW.

These equations were incorporated into a MATLAB R2023a simulation executed over 300 s with 1-s time steps and a thermostat setpoint of 75 °F with a ±0.5 °F deadband, under a constant total space load of 24 kBtu/h.

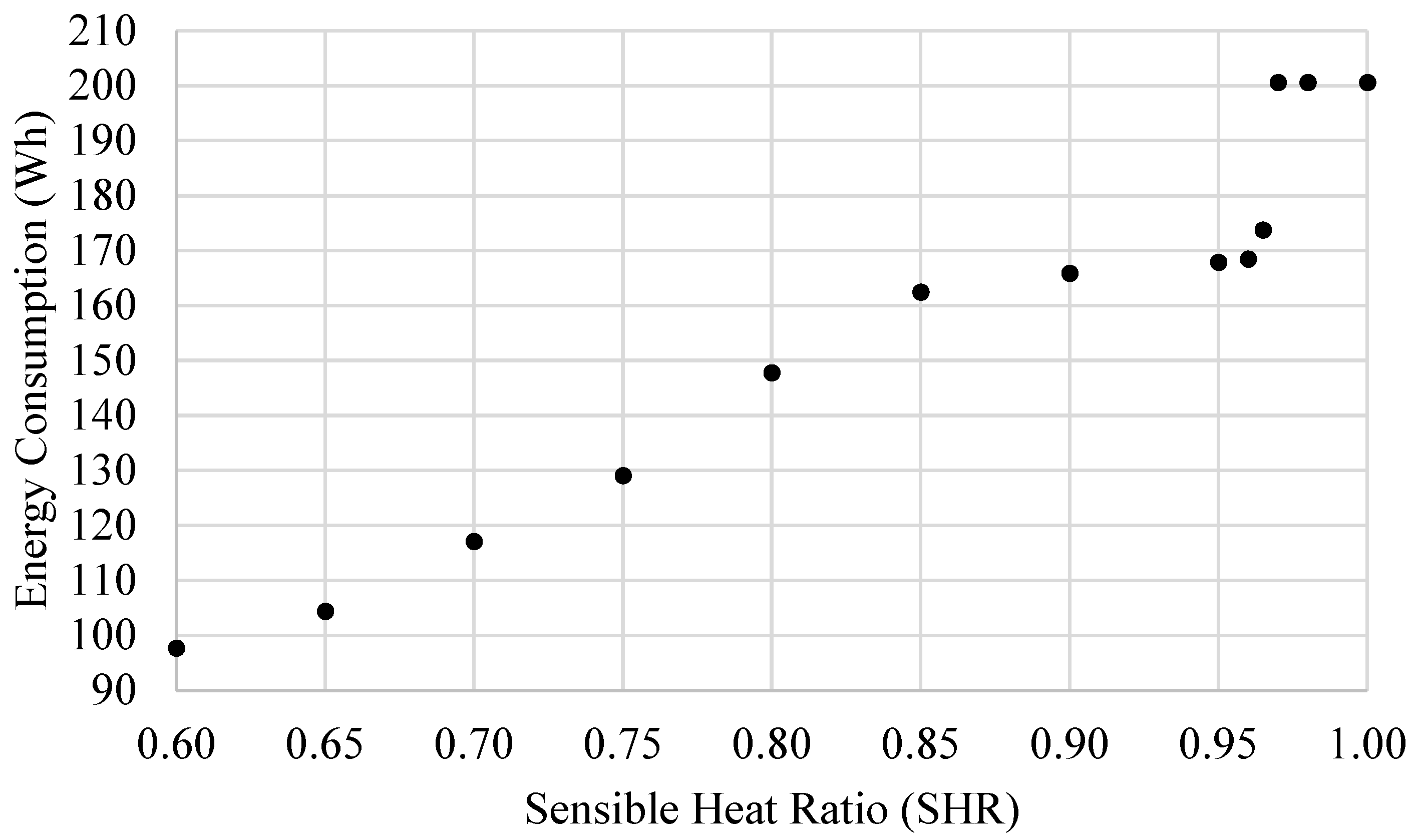

Indoor humidity varied by adjusting the sensible heat ratio (SHR) of the load. For a fixed total load, reducing SHR reallocates a portion of sensible load into latent load, representing indoor conditions with greater moisture generation. Because manufacturer data show that total capacity increases with indoor wet-bulb temperature more rapidly than power input, higher indoor humidity leads to reduced runtime for the same cooling load. The resulting decrease in runtime outweighs the increase in instantaneous power, producing a net reduction in total energy use, as shown in

Figure 2. This behavior explains the counterintuitive result that systems operating under slightly more humid indoor conditions may consume less total cooling energy.

The resulting trends, illustrated in

Figure 2, show that as the SHR decreases, the total energy consumption of the system also decreases. This indicates that systems operating under slightly more humid indoor conditions may, paradoxically, require less total energy to maintain thermal balance. It should be noted that the curvature and the more rapid change in performance near SHR values between 0.95 and 0.98 reflect the characteristics of the manufacturer performance data and the corresponding curve fits, rather than indicating a physical discontinuity in the system behavior.

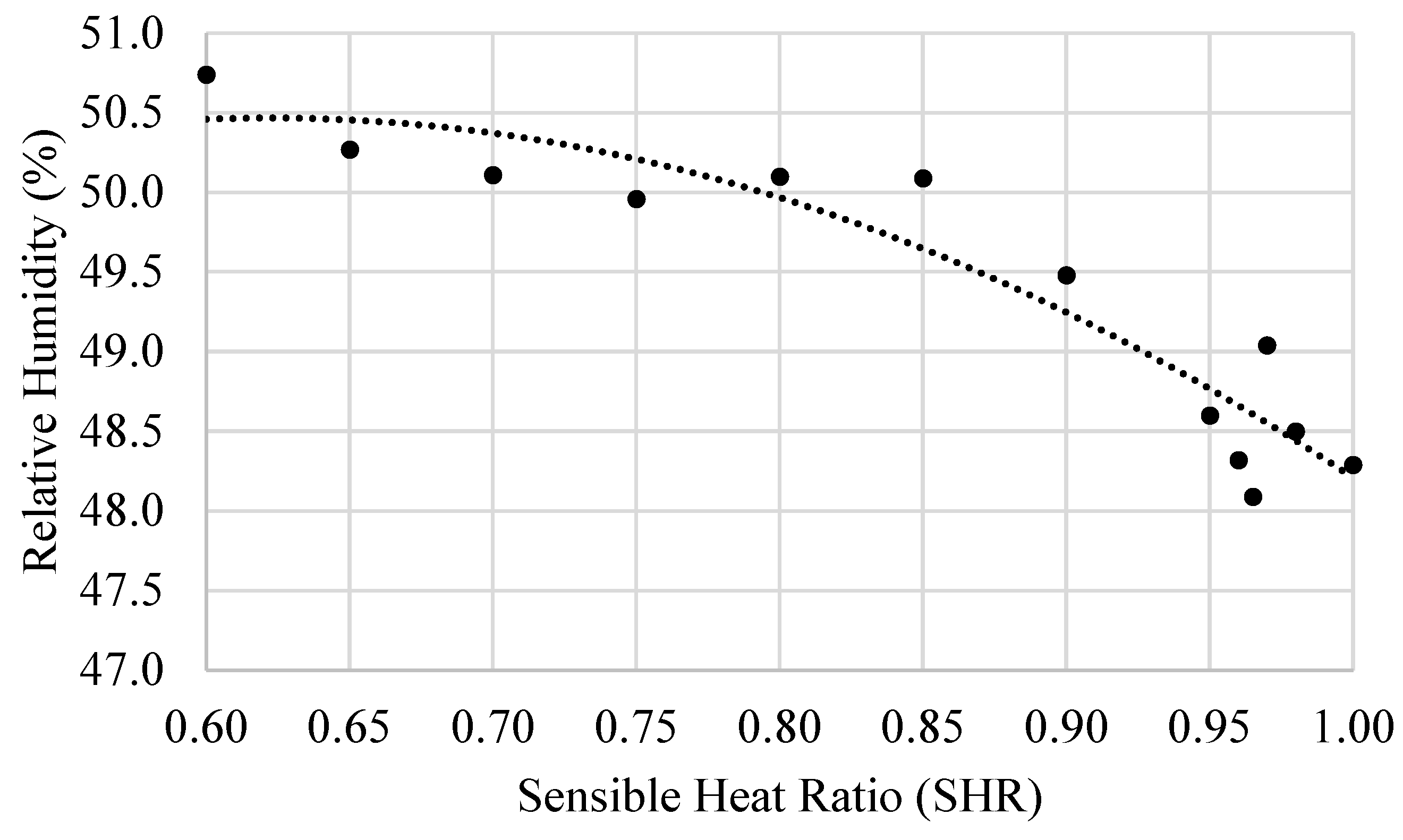

Additionally,

Figure 3 illustrates how indoor relative humidity increases as the SHR decreases, further demonstrating the relationship between system performance and humidity level. Together, these results show the potential for energy savings when the system is operated at slightly higher indoor humidity levels without compromising comfort.

5. Impacts of High Relative Humidity

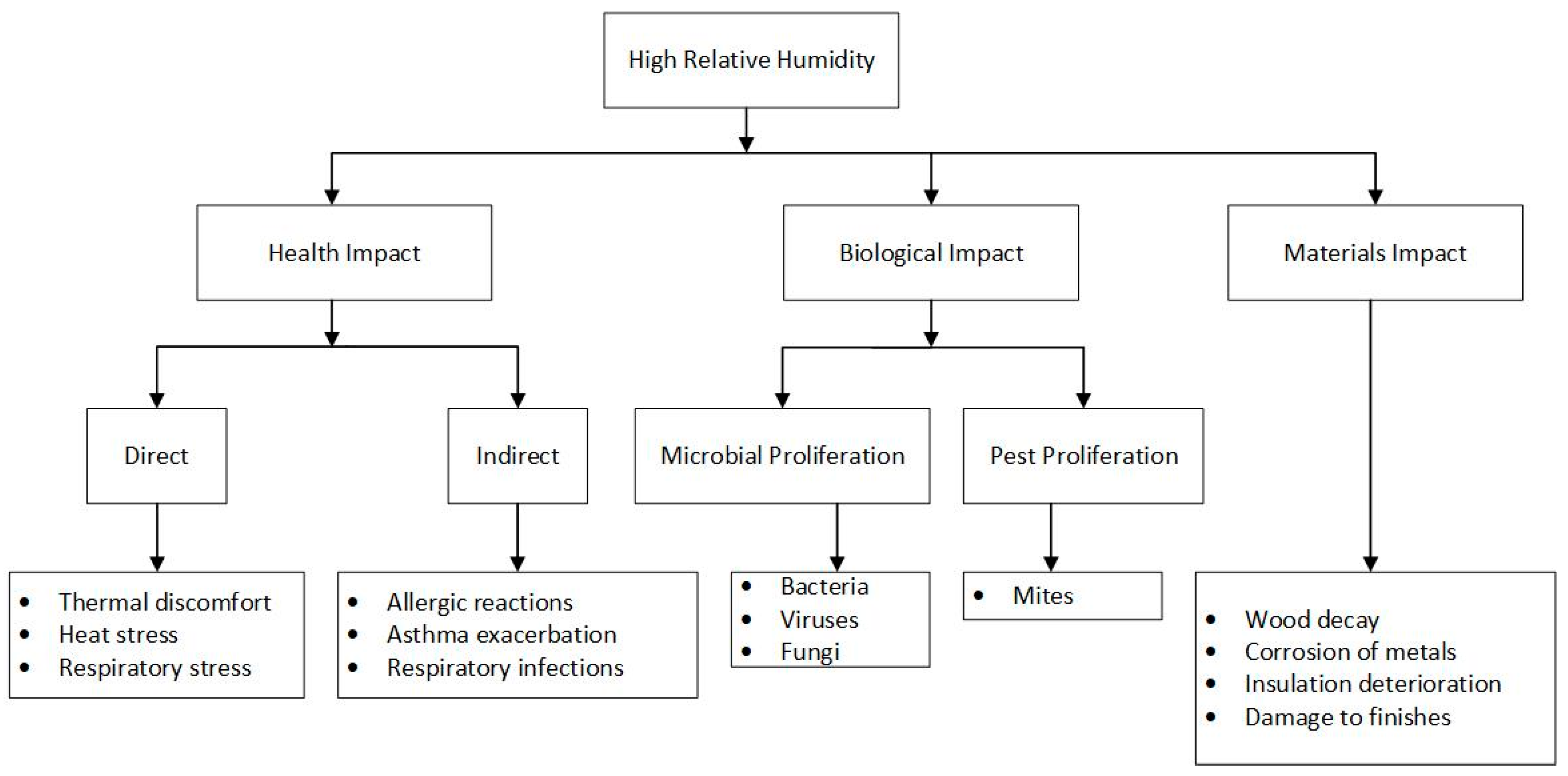

High indoor relative humidity can influence multiple aspects of the residential environment, affecting occupant health, biological activity, and material durability. The impacts can be classified into three primary domains: (1) Health Impact, (2) Biological Impact, and (3) Materials Impact, as illustrated in

Figure 4. The health impact includes both direct and indirect effects resulting from excess moisture in indoor air, with indirect effects directly related to biological sources. While health impacts relate to human physiological and allergic responses, biological impacts refer to the proliferation of microorganisms and pests supported by humid conditions. In contrast, material impacts concern the degradation of construction components and finishes due to sustained moisture exposure. Understanding these interrelated domains provides a foundation for defining safe humidity ranges that minimize adverse outcomes while maintaining energy efficiency and comfort.

5.1. Health Impact

As mentioned, high relative humidity can directly and indirectly affect human health. Direct impacts of relative humidity include thermal discomfort, heat stress, and respiratory stress, as elevated humidity hinders the body’s evaporative cooling process and increases perceived temperature. These effects become noticeable when relative humidity exceeds approximately 60%, and are more pronounced above 70–75%, where evaporative cooling efficiency declines significantly and the risk of heat-related illness increases. However, the hazard associated with RH levels above 80% under warm conditions applies primarily to unconditioned or poorly ventilated environments; in thermally conditioned indoor spaces, air temperature control and circulation typically prevent such extreme physiological stress. It is also important to distinguish between thermal comfort and heat stress. While high RH can contribute to discomfort at elevated air temperatures, within the common indoor temperature range (74–77 °F or 23–25 °C), increases in relative humidity up to moderate levels may not negatively affect, and can sometimes improve, perceived comfort as measured by the PMV index. The relationship between humidity and thermal comfort is therefore nonlinear, depending on both air temperature and metabolic activity, whereas heat stress represents a physiological limit that emerges when humidity and temperature combine to inhibit adequate body heat dissipation.

Factors such as filter type, filtration efficiency, and maintenance frequency also influence indoor air quality; however, because these operate independently of humidity-related health mechanisms, they are considered outside the scope of the present analysis.

Indirect impacts occur through biological and environmental pathways. These include allergic reactions (from dust mites and mold spores), asthma exacerbation, and greater survival of airborne pathogens potentially impacting respiratory infections.

A broad synthesis of humidity-related health research was previously conducted by Baughman and Arens [

9] in a review published in ASHRAE Transactions, which examined the mechanisms by which humidity influences indoor air pollutants and occupant health. Their analysis consolidates several decades of work showing that the primary health impacts associated with elevated indoor humidity occur indirectly, through the behavior of humidity-dependent pollutants rather than from humidity alone. These include biological agents such as dust mites, fungi, and bacteria, as well as chemical emissions whose release or transformation is sensitive to moisture levels, including formaldehyde and other volatile organic compounds. The review concludes that adverse health outcomes associated with humidity are largely mediated by microenvironments within buildings—especially surfaces, materials, and conditioned cavities—where elevated moisture or condensation supports biological or chemical activity.

Importantly, Baughman and Arens note that for most humidity-influenced health factors, evidence does not support a distinct change in health risk between 60% and 70% indoor RH. Instead, biological agents generally require sustained surface moisture or local RH levels well above room-air humidity to grow or remain active. Fungal growth, for example, typically requires surface RH above approximately 70–80%, and dust mites depend on microhabitat moisture that is not solely determined by ambient RH. These findings reinforce that humidity-related health risks depend primarily on avoiding surface moisture accumulation or condensation, rather than on maintaining a strict upper limit for indoor air RH.

With this broader context established, and due to the extensive body of literature available on humidity and health, this section focuses on two comprehensive reviews, one classic Arundel et al. [

10] and one recent Guarnieri et al. [

11], to capture both foundational and updated perspectives on how RH indirectly may affect human health. Together, these studies outline a consistent picture in which deviations from the mid-range RH are associated with adverse physiological and environmental effects.

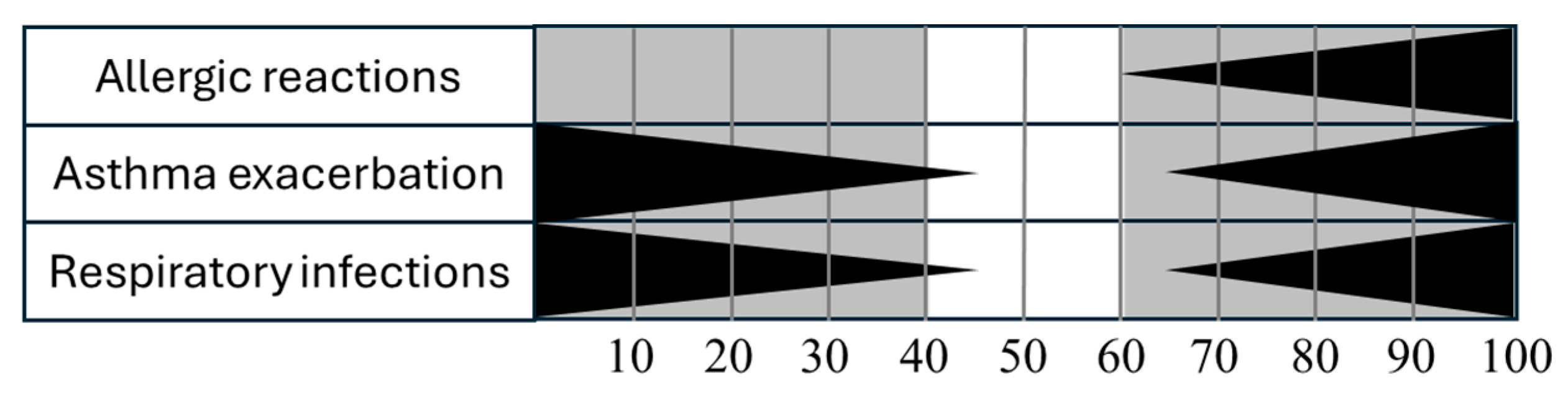

The combined epidemiological and experimental evidence suggests that indirect effects increase when RH falls below 40% or exceeds 60%. Because individual studies vary in design and climate context, an uncertainty range of approximately ±5% should be recognized around these thresholds. Consequently, an upper limit of maintaining indoor RH at 65% is recommended to minimize adverse health effects while accommodating measurement and environmental variability. Since indirect effects are mainly associated with the factor discussed in the next

Section 5.2, maintaining indoor humidity in the upper portion of the recommended range (60–65%) can improve respiratory comfort and mucosal hydration without increasing the likelihood of microbial growth or other indirect health effects.

Figure 5 summarizes the potential effects of relative humidity on human health. The figure is adapted from the schematic representations in Arundel et al. [

10] and Guarnieri et al. [

11], combining historical and contemporary evidence on humidity-related health outcomes. The blank region between 40% and 60% RH represents the recommended safe range in which adverse effects are minimized, while the black triangles illustrate the increasing magnitude of potential health impacts, their widening base denoting greater effect severity, as humidity deviates from this optimal interval.

5.2. Biological Impact

The influence of relative humidity on biological activity in indoor environments has been documented in both studies considered [

10,

11]. It has been documented how bacteria, viruses, fungi (commonly referred to as

mold in buildings), and mites all respond to humidity in ways that can affect indoor air quality, allergy prevalence, and respiratory health.

5.2.1. Bacteria

Both reviews indicate that airborne bacterial survival follows a U-shaped response to humidity. Arundel et al. [

10] observed that the viability of airborne bacteria such as Serratia marcescens, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Brucella suis, and Staphylococcus albus is lowest at mid-range humidity (approximately 40–60% RH) and increases under both dry (<30–40%) and moist (>70%) conditions. Guarnieri et al. [

11] reported similar behavior in building systems, noting that bacteria commonly colonize humidifiers and cooling equipment when RH exceeds 60%, or persist in extremely dry air (<30% RH). These findings suggest that bacterial persistence is most effectively limited when humidity remains within the 40–60% range.

5.2.2. Viruses

Viral infectivity is also influenced by relative humidity. Arundel et al. [

10] reported that lipid-enveloped viruses such as

influenza,

measles, and

varicella survive longer in dry air (<40–50% RH), whereas non-enveloped viruses such as

adenovirus and

coxsackievirus are more stable in high-humidity conditions (>70% RH). Guarnieri et al. [

11] confirmed that viral growth, stability, and infectivity increased below 50% and above 70% RH, reinforcing that mid-range humidity is optimal for reducing airborne transmission. Maintaining indoor air within this band minimizes both bacterial and viral viability simultaneously.

5.2.3. Fungi

Mold represents the predominant form of indoor fungi and is among the most humidity-sensitive biological contaminants. According to Arundel et al. [

10], most allergenic molds, such as Aspergillus, Cladosporium, Alternaria, and Mucor, require RH above 60% for active growth, with sporulation and visible colonization becoming significant beyond 75–80% RH. Guarnieri et al. [

11] corroborated that indoor

mold prevalence increases markedly once RH exceeds 60%, elevating allergen exposure and respiratory irritation. Below this threshold, mold metabolism and spore release remain negligible, preventing contamination of surfaces and air.

Because the most common humidity-related issue in residential environments is

mold growth, recent work examining how indoor RH and temperature govern mold development provides relevant context for understanding upper humidity limits. A large-scale study of 219 homes by Menneer et al. [

12] developed and tested mold-growth predictions using time-series indoor air measurements of RH and temperature, adapting the widely used VTT model to real domestic conditions. Their analysis confirmed that mold-favorable conditions generally require sustained RH above approximately 70–80%, particularly at material surfaces, and that surface microclimates, rather than room-air humidity alone, govern the likelihood of contamination. The study also showed that mold indices derived from ambient RH data aligned with occupant reports of visible

mold or moldy odor only when the model parameters assumed higher vulnerability at surfaces, reinforcing the conclusion that condensation or persistently damp materials are the dominant drivers of growth rather than moderate indoor RH levels.

5.2.4. Mites

Dust mites are another key biological indicator of excess humidity. Arundel et al. [

10] documented that mite populations are virtually eliminated below 45–50% RH and reach maximum density at approximately 80% RH. Their abundance closely parallels seasonal or indoor humidity variations, as mites depend on ambient moisture to maintain water balance. The resulting allergenic particles, shed body fragments and fecal pellets, are major contributors to allergic rhinitis and asthma. Hence, controlling RH below 55% is one of the most effective strategies for reducing mite proliferation in residential environments.

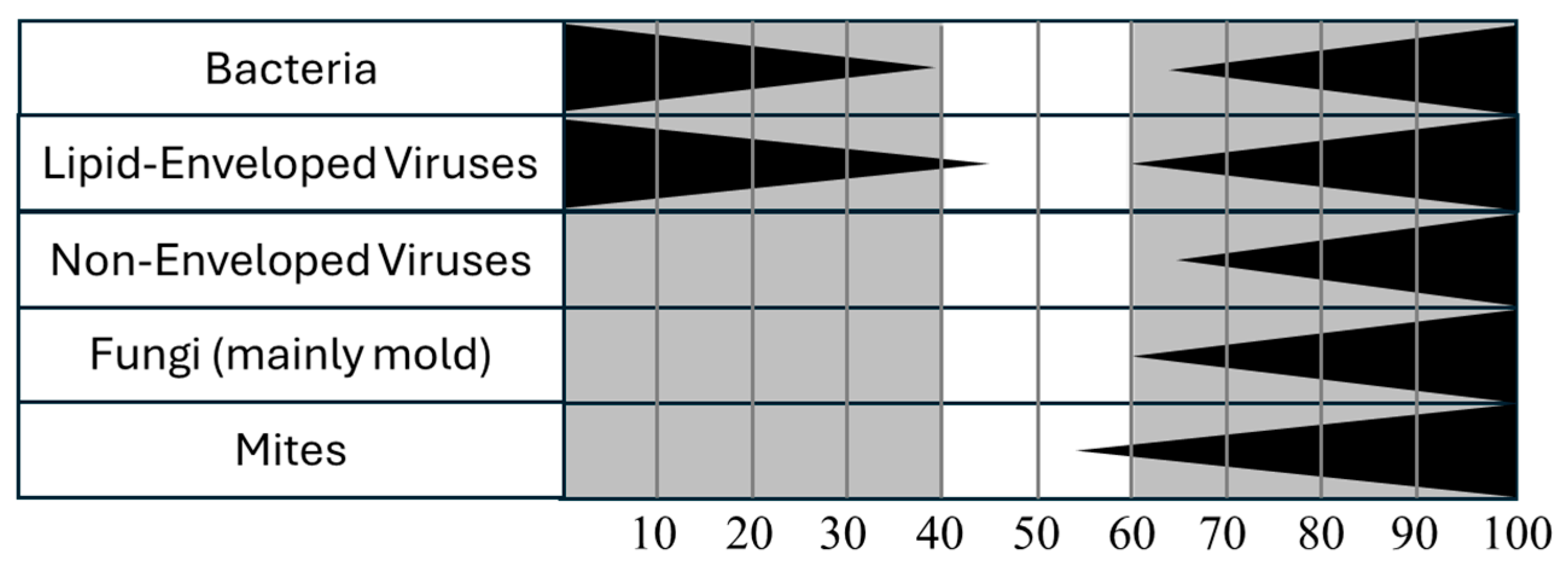

Figure 6 illustrates the relative influence of humidity on different biological agents, based on the data synthesized from Arundel et al. [

10] and Guarnieri et al. [

11]. This figure uses the same graphical convention introduced in

Figure 5, where the central blank region represents the recommended 40–60% RH where microbial and pest activity is minimized. The black triangles indicate increasing biological activity as humidity moves away from this range.

5.3. Materials Impact

The majority of the literature agrees that issues related to high indoor relative humidity arise primarily from the interaction between humid air and cooled surfaces. Documents developed for practical control of humidity, such as the Moisture Control Guidance for Building Design, Construction, and Maintenance (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency) [

13] focus mainly on liquid water sources of moisture intrusion, while their discussion of humid air is typically limited to air leakage through assemblies. In conditioned spaces the outdoor humid air can encounter cooled surfaces in its path to the inside of the house, thereby increasing the potential for surface condensation.

The Research Report on Relative Humidity by Lstiburek [

2] emphasizes that “elevated relative humidity at a surface—70% or higher—can lead to problems with

mold, corrosion, decay, and other moisture-related deterioration”. In the section Determining the Humidity Limits—the Debate, the consensus presented is that interior relative humidity should be maintained so that surface relative humidity never exceeds 70%, and that indoor RH should not rise above 60% to prevent such conditions. Since, for a given dew-point temperature, relative humidity increases as air temperature decreases, it follows that the risk of condensation arises primarily where surfaces are significantly cooler than the surrounding air.

Under normal summer conditions, wall and ceiling temperatures should remain between indoor and outdoor air temperatures, resulting in surface relative humidities equal to or below those of the indoor air. Thus, the potential for condensation within the occupied space is confined mainly to cold surfaces directly influenced by air-conditioning equipment, such as supply registers, poorly insulated ducts, or surfaces exposed to cold air jets. In the author’s assessment, when an air-conditioning system is properly designed and well installed, with well-insulated supply ducts and appropriately positioned diffusers, the literature supports maintaining an indoor relative humidity in the upper limit at 60% without risk of reaching the critical 70% RH at material surfaces associated with moisture-related damage in residential buildings.

This controlled humidity condition influences materials differently, with impacts ranging from harmless equilibrium adjustments to potential long-term degradation depending on material type and surface exposure. The following discussion expands on the categories summarized in

Figure 4, describing how specific materials respond when exposed to elevated but stable humidity levels.

5.3.1. Wood Decay

Wood is sensitive to humidity through its equilibrium moisture content (EMC), which increases as RH rises. When the wood moisture content exceeds about 15%, typically corresponding to an air relative humidity of approximately 80%, biological activity such as fungal growth may occur. At an indoor RH of 60%, the corresponding EMC is roughly 11%, a safe and stable value. Therefore, under constant temperature and humidity, interior wood materials, flooring, furniture, and trim, will equilibrate slightly above their ideal moisture content range (6–9%) but remain well below decay thresholds. Only sustained RH above 75–80%, where wood moisture content approaches or exceeds 15%, would promote deterioration or fungal growth.

Because wood is a primary structural material in many U.S. residential buildings, insights from mold research focused on wood-based substrates are particularly relevant to evaluating moisture-related risks. A systematic review of mold growth in wood materials by Gradeci et al. [

14] provides a detailed analysis of the environmental conditions governing biological activity and highlights the dominant role of surface relative humidity, substrate characteristics, and exposure duration in determining susceptibility. Across more than 100 experimental and field studies, the review found consistent evidence that mold growth on wood generally requires sustained surface RH above approximately 75–80%, even though ambient indoor air RH may be significantly lower. The authors emphasize that fluctuations in humidity and temperature, as well as material-specific properties such as sapwood content, surface quality, and coating systems, strongly influence mold initiation and growth. These findings reinforce that for wood-based residential assemblies, mold risk is controlled primarily by surface moisture and microclimate conditions, rather than by moderate levels of indoor air humidity alone.

5.3.2. Corrosion of Metals

Corrosion risk depends on the availability of an electrolyte film that forms when RH exceeds 70–75% at metal surfaces. Below this limit, most metals, including steel and copper, remain passive and unaffected. With indoor RH maintained near 60%, the air lacks sufficient vapor to sustain the continuous moisture film necessary for electrochemical corrosion. Thus, elevated but controlled indoor humidity does not pose a corrosion risk for residential metals, provided surfaces are not exposed to condensation or salt contaminants.

5.3.3. Insulation Deterioration

Thermal insulation performance depends on maintaining dry, air-filled pores. When relative humidity near insulation surfaces approaches saturation, water vapor may condense within porous materials, increasing thermal conductivity and reducing R-value. However, when indoor RH is limited to about 60%, the vapor pressure differential across wall and ceiling assemblies remains moderate, preventing interstitial condensation. Proper vapor diffusion control and air sealing further ensure that insulation remains dry and effective, even in cooling-dominated climates.

5.3.4. Damage to Finishes

Finishes, including paints, coatings, and laminated materials, are sensitive to moisture cycling. High RH or localized condensation can lead to cracking, warping, blistering, or delamination. These failures occur when substrate moisture changes rapidly or when water accumulates beneath impervious coatings. With RH stabilized near 60% and temperature held constant, wood and gypsum substrates maintain dimensional equilibrium, significantly reducing stress on surface finishes. In this range, finishes remain aesthetically and mechanically stable, avoiding the deformation and adhesion loss associated with prolonged high humidity.

6. Relative Humidity and Condensation

The relationship between indoor relative humidity and condensation is central to understanding moisture-related risks in residential environments. While relative humidity influences comfort, health, and energy use, its impact on building durability and indoor air quality is primarily governed by whether condensation occurs on interior surfaces. Condensation represents the threshold where humidity transitions from an environmental condition to a physical mechanism that enables material degradation and microbial growth.

In typical homes, condensation occurs when the surface temperature of walls, windows, or other interior elements falls below the air’s dew-point temperature. This condition is influenced not only by indoor relative humidity and air temperature but also by the quality of insulation, thermal bridging, and air circulation. Well-insulated homes with minimal thermal bridges and consistent surface temperatures can safely tolerate moderately higher indoor humidity levels—up to about 65–70%—without condensation risk. Conversely, older or poorly insulated buildings, particularly those with single-pane windows or cold exterior walls, may experience condensation even at relative humidity levels near 55%. During the cooling season, however, this condition is generally absent, since the interior surfaces of the building envelope remain warmer than the conditioned indoor air, preventing the surface relative humidity from exceeding that of the room.

The VTT Mold Growth Model [

15], developed by the Technical Research Centre of Finland (VTT), provides a practical framework for evaluating the onset of mold under varying combinations of temperature, relative humidity, and exposure duration. The model uses a Mold Index ranging from 0 to 6, where higher values indicate greater visible mold growth. Under typical indoor temperature conditions (74–77 °F or 23–25 °C), the model predicts that mold initiation requires sustained surface relative humidity above approximately 85%. These finding highlights that the true risk in humid environments lies not in elevated air humidity alone, but in localized surface conditions were temperature gradients and high RH lead to persistent surface wetness. This condition was illustrated recently by Tsongas in an article published in ASHRAE Journal [

16], highlighting typical cases of mold growth originating from sources of liquid water of humid air exposed to cold surface.

From a health perspective, high indoor humidity by itself has limited direct effects, aside from potentially aggravating asthma or other respiratory sensitivities. Most health issues associated with humid environments, such as allergic reactions, microbial exposure, and poor air quality, are secondary effects of condensation. When surface moisture supports the growth of fungi, bacteria, or dust mites, biological agents proliferate and become the actual drivers of health impacts. Thus, effective humidity control should focus not merely on air moisture content but on preventing condensation that enables biological amplification.

In practical terms, this means that indoor relative humidity can be maintained at slightly higher levels, within the 60–70% range, if surface temperatures remain above the dew point and air circulation prevents moisture accumulation in cold or stagnant zones. Under these conditions, moderate humidity levels can contribute to improved comfort and reduced energy consumption without promoting microbial growth or material degradation.

Maintaining an appropriate balance between humidity and condensation control requires a holistic design and operational approach. Strategies include improving insulation continuity, minimizing thermal bridges, ensuring adequate air mixing, and maintaining moderate indoor humidity levels. By integrating these principles, homeowners and HVAC professionals can achieve safe and efficient humidity management, supporting both occupant well-being and building longevity.

From the author perspective, humidity itself is not the problem, condensation is. The key to safe high-humidity operation lies in ensuring that no surface remains cool enough to reach the dew point for prolonged periods. When this condition is met, higher indoor humidity can provide tangible benefits in energy efficiency and comfort while maintaining the integrity of materials and the health of the occupants.

7. Conclusions

This study evaluated the effects of indoor relative humidity on thermal comfort, energy performance, health, biological activity, and material durability in residential buildings during the cooling season. The analysis demonstrates that moderately elevated indoor humidity levels, compared with traditional targets near 50% RH, can be acceptable—and in some cases beneficial—when condensation is avoided.

Thermal comfort assessment using the PMV model showed that increasing relative humidity within the typical indoor cooling temperature range (74–77 °F) shifts thermal sensation toward neutrality, reducing the cool bias often observed at lower humidity levels. HVAC performance modeling further indicated that higher indoor wet-bulb temperatures increase total cooling capacity. Although power consumption also rises, the associated reduction in runtime leads to a net decrease in total energy consumption over a complete cooling cycle, as reflected in the model results.

A review of health-related literature established that most direct and indirect physiological effects associated with humidity remain minimal, below approximately 65% RH. Similarly, biological activity from mold, dust mites, bacteria, and viruses remains limited below the critical surface humidity conditions required for growth and survival. Material durability analyses confirm that wood decay, corrosion, insulation deterioration, and finish degradation are primarily driven by surface moisture rather than indoor air humidity alone.

Across all domains, the findings emphasize that humidity itself is not the primary risk factor—condensation is. Moisture-related problems arise when interior surface temperatures fall below the dew point, creating localized regions where surface relative humidity can reach levels favorable for microbial activity or material degradation. When interior surfaces remain sufficiently warm, these risks are largely absent even at moderately elevated indoor humidity levels.

Therefore, the upper indoor relative humidity limit for residential environments during cooling operation can safely be extended to approximately 65%, provided that interior surface temperatures remain above the dew point, since this prevents surface relative humidity from approaching the 70% range associated with moisture-related risks. Under these conditions, indoor humidity can support acceptable comfort, stable material performance, and reduced cooling energy use.

Overall, the results suggest that residential humidity management should prioritize condensation prevention rather than strict minimization of indoor air humidity. With adequate insulation, proper air distribution, and responsible HVAC operation, maintaining indoor RH up to 65% during the cooling season offers a practical balance between comfort, health protection, energy efficiency, and building durability.