1. Introduction

Digitalization is among the most significant transformational tools in the construction industry, and redefines the processes of design, construction, and operation. The attempts to become more efficient, the growing complexity of projects, and the necessity to organize and manage data have led the industry to transition to information-based decision-making processes [

1,

2]. While traditional two-dimensional design and coordination methods cause problems such as information loss, design conflicts, and increased costs, digitalization offers holistic solutions to address these faults [

3]. The need for data integration and coordination, particularly in multidisciplinary projects, has made the adoption of digital methods essential [

4,

5].

One of the most significant reflections of this transformation in the construction industry is Building Information Modeling (BIM) technology. BIM is an integrated digital representation, a comprehensive description of the physical and functional features of buildings, and it generates a universal information base at the stage of design, construction, and operation [

3,

6]. According to this technology, all stakeholders of the project can work on the same model, and in this way, there is less loss of information, fewer mistakes in the design, and more efficiency in the project [

7]. In addition, its 4D (time management), 5D (cost analysis), and 7D (operation and maintenance management) dimensions provide full solutions to building lifecycle management [

4,

8].

The digitalization processes based on BIM have come to a new stage in recent years, and the concept of the Digital Twin has appeared. According to recent studies, digital twin technologies have developed speedily due to the introduction of BIM, IoT, and artificial intelligence to facilitate real-time monitoring and predictive management in the built environment. Tuhaise et al. [

9] found the key enabling technologies for digital twins in the construction industry and highlighted the need to establish interoperability between BIM and data-driven systems. The systematic review conducted by Liu et al. [

10] showcased the increased application of digital twin technologies to buildings and cities, even though it also emphasizes the fact that the practical, scalable implementation of digital twins should be promoted to industries. Pan et al. [

11] also showed that semantic point cloud data can be converted into information-rich BIM models by deep learning-based approaches to significantly increase the accuracy and automation of the processes of digital twin creation.

Grieves [

12] and Tao et al. [

13] suggest that a digital twin is a dynamically operating data-driven and interactive representation of a physical asset or system in a digital space. This approach combines BIM, IoT (Internet of Things), big data, and artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to enable real-time monitoring, analysis, and predictive maintenance throughout the lifecycle of buildings [

14,

15]. Fuller et al. [

14] stated that digital twins enhance operational efficiency, safety, and sustainable management in construction projects, while Wang et al. [

5] stated that IoT-enabled digital twins deliver effective results in terms of energy performance and facility management.

Digital twin technologies are used in a wide range of applications, including building management [

4], industrial facility optimization [

16], infrastructure monitoring [

1], cultural heritage documentation [

17], and urban planning [

18]. Recent studies indicate that digital twins offer significant contributions not only to the design process but also to processes such as construction phase monitoring and maintenance planning [

14,

15].

The recent studies have paid attention to the applications and technical specifications of the digital twin. As an example, Abreu et al. [

19] found that point cloud-based modeling boosts the accuracy of models in the cases of scan-to-BIM and scan-vs-BIM; Tang et al. [

20] and Dore and Murphy [

17] found that laser scanning (LiDAR) technologies improve data integrity in the model of the interior space. These technologies produce high-precision datasets for the digitalization of existing buildings and provide a solid geometric foundation for the digital twin creation process.

Despite the increasing number of studies in the literature on the application areas of digital twin technologies, the creation of digital twins of existing buildings through the integration of point cloud data into the Building Information Modeling (BIM) environment has been addressed in limited application-based research [

19,

20,

21]. This demonstrates that point cloud-based digital twin creation remains an area of methodological and practical development. Although scan-to-BIM and digital twin approaches are rapidly becoming widespread worldwide, practical examples of these methods, especially in industrial facilities, are quite limited in Turkey.

In parallel, recent research has increasingly explored AI-assisted point cloud segmentation and automated object recognition as a means of reducing manual modeling effort in scan-to-BIM workflows, particularly for complex indoor environments and industrial assets [

22]. However, these developments have only rarely been evaluated in real industrial facilities, and there is still a lack of case studies that report not only qualitative benefits but also quantitative indicators of accuracy, modeling effort, and performance.

Although the global literature on digital twins and scan-to-BIM workflows has expanded significantly, practical implementations in industrial facilities—particularly within emerging economies such as Turkey—remain extremely limited. Existing studies rarely provide a detailed, replicable framework that evaluates both geometric precision and operational applicability. This study addresses these gaps by presenting one of the first industrial-scale implementations of a LiDAR-based digital twin workflow in Turkey, documenting the complete process from data acquisition to modeling, reporting accuracy and performance metrics, and extending conventional scan-to-BIM practices to include production-line machinery through parametric Revit Families.

2. Methodology

The methodology employed in this study involves the integration of point cloud data obtained using LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) technology, based on a scan-to-BIM approach, into the Building Information Modeling (BIM)-based Digital Twin production process using Autodesk ReCap 2022 and Autodesk Revit 2022 software.

The implemented method consists of four main stages that follow a scan-to-BIM logic: (i) data collection using terrestrial LiDAR, (ii) point cloud preprocessing and registration in Autodesk ReCap, (iii) data integration and parametric modeling in Autodesk Revit, and (iv) enrichment of the BIM model into a digital twin including production-line machinery. Each stage is described in detail in

Section 2.1,

Section 2.2,

Section 2.3 and

Section 2.4, with special emphasis on software versions, hardware configuration, and workflow decisions to support reproducibility.

This framework is based on the scan-to-BIM methodology described in the literature [

19,

20] and aims to ensure accuracy, integrity, and information continuity in the digital transfer of existing buildings.

2.1. Data Collection: LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging)

LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) technology is a remote sensing method that allows the acquisition of three-dimensional (3D) coordinate data by measuring the return time of laser pulses sent to surfaces [

23].

This method enables the generation of point cloud data that represents the physical geometry of structures or objects with high accuracy.

As part of the study, the interior and exterior of the factory were documented using a terrestrial laser scanning (TLS) campaign. The scan data was acquired with a FARO terrestrial laser scanner, although the exact device model was not available to the authors. A total of 36 scan locations were distributed across the production hall and exterior facade to ensure sufficient coverage and overlap for accurate cloud-to-cloud registration. The scanned area corresponds to a single high-bay industrial hall with an approximate floor area of 240 m2, containing dense mechanical equipment such as vertical tanks, platforms, and processing lines, which created a challenging three-dimensional environment for data acquisition. Despite these constraints, the TLS configuration provided adequate geometric completeness for transferring the existing structure into a digital environment.

Scanning parameters were optimized according to the technical capabilities of the device and the environmental conditions.

Such a strategy allowed obtaining very precise information when transferring the digital version of the already existing three-dimensional geometry of the structure.

In addition, key LiDAR scanning parameters—including point density, station spacing, field-of-view coverage, and overlap ratio between consecutive stations—were optimized to ensure uniform data quality across the industrial environment. These parameters were adjusted according to surface reflectivity, interior clutter, and operational constraints of the active production facility, ensuring a consistent point distribution suitable for accurate BIM reconstruction.

2.2. Data Processing: Autodesk ReCap

Autodesk ReCap software is a pre-processing tool used to align, filter, and optimize laser scan data [

24]. ReCap software aligns data from different scan points by using a cloud-to-cloud registration algorithm to create a holistic 3D point cloud [

19,

21].

In this study, LiDAR scans were imported into the ReCap environment, combined using an automatic alignment algorithm, and noise data was removed.

During the data optimization process, errors originating from glossy surfaces and reflections from moving objects were eliminated.

ReCap was chosen because it reduces the need for manual intervention in high-volume point cloud data and produces a data format (.RCP) compatible with Revit.

This process minimized data loss and increased the accuracy of the subsequent modeling phase.

The point cloud was delivered to the authors as a pre-registered dataset, already aligned by the surveying team using the FARO TLS processing workflow prior to import into Autodesk ReCap. Because the scans arrived in a fully registered state, ReCap did not display station-level registration diagnostics or RMSE values; therefore, numerical registration errors could not be extracted directly from the software. Registration quality was instead assessed visually by inspecting the consistency of overlaps between the 36 scan locations, reviewing cross-sections, and checking for signs of drift, duplicated geometry, or local misalignment across the dataset.

A detailed quality-control routine was implemented during preprocessing, including the verification of overlap sufficiency among scan stations and the assessment of residual noise around metallic and highly reflective surfaces. The final exported .RCP dataset was validated against on-site reference dimensions to confirm suitability for LOD-300-level BIM.

2.3. Transfer to BIM Environment: Revit Integration

Autodesk Revit is a parametric design platform based on Building Information Modeling (BIM), allowing the creation of component-based intelligent models [

25] that maintain geometric and informational relationships among building elements [

3]. In this study, the modeling phase was carried out in Autodesk Revit 2022, while some of the views and visualizations included in the paper were updated in Revit 2023 without modifying the underlying geometry or parametric structure of the model.

The registered point cloud dataset exported from Autodesk ReCap was brought into Revit using the linked point cloud workflow, where the .RCP file served as a fixed spatial reference throughout the modeling process. This approach enabled the digital reconstruction of the physical elements of the building—including walls, columns, floors, roofs, platforms, and equipment supports—directly on top of the point cloud.

To establish a consistent modeling framework, levels, grids, and reference planes were created and aligned with the coordinate system defined by the imported TLS data. Structural and architectural elements were then traced, parameterized, and dimensioned according to the geometric indicators provided by the point cloud.

The modeling scope corresponded to a Level of Detail (LOD) of 300, as described in the relevant literature [

6,

19]. In this project, LOD-300 compliance was ensured by modeling all primary structural elements with their true dimensions, relative positions, and relational constraints, and by verifying that deviations between the Revit elements and the point cloud remained within an acceptable tolerance of approximately 10 mm, based on point-to-model distance measurements carried out at multiple locations.

Revit was selected for this workflow because its parametric modeling infrastructure supports point-cloud-based reconstruction and maintains information continuity during the creation of digital twins, enabling each modeled element to carry both geometric fidelity and relevant metadata required for future analysis, renovation planning, or integration with additional digital systems.

2.4. Digital Twin Modeling

A digital twin is defined as a dynamic, data-driven representation of a physical asset in a digital environment [

14,

15].

This model includes not only geometric accuracy but also the relationships between structural components, material information, and usage data.

The model, completed in the Revit environment, was structured in accordance with these principles. The model was compared with point cloud data and evaluated for visual and dimensional accuracy. Potential clashes between structural elements were analyzed with a clash detection tool.

Machines on the factory production line were modeled as parametric components in the Revit Family environment, thus expanding the digital representation of the structure to include the manufacturing system. For each machine family, non-geometric parameters were added to capture functional attributes relevant to facility management, including equipment type, manufacturer and model, rated capacity, power demand, installation date, and maintenance interval. Where available, process-related attributes such as throughput and operating schedule were stored as instance parameters, enabling the model to be queried not only for geometric fit but also for production and maintenance planning.

The goal in this phase is not only to digitize the current state but also to create a digital decision support system that can be used for future equipment changes or capacity planning, for example, by computing available floor areas for new machines, checking safety clearances around hazardous zones, or testing alternative machinery layouts before construction.

2.5. Method Summary

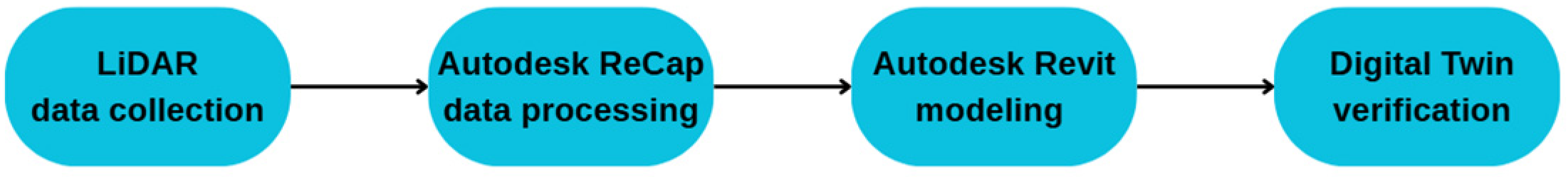

The applied method is an integrated process, which consists of LiDAR-based data collection, data processing with Autodesk ReCap, modeling with Autodesk Revit, and digital twin production. This process is shown illustrated in

Figure 1. The diagram presents the data flow and software interaction between the four main stages of the study in an integrated manner.

Each phase was planned based on the principles of accuracy, information continuity, and model integrity.

LiDAR technology enabled documentation of the physical environment, ReCap optimized the data, and the Revit environment enabled parametric modeling.

This approach, which combines the scan-to-BIM model in the literature with the concept of a digital twin, provides a viable methodological framework for the digitization of existing buildings.

To support the reproducibility of this study, all scanning configurations, preprocessing steps, registration processes, and modeling criteria were documented systematically. The entire workflow—ranging from LiDAR data acquisition to ReCap preprocessing and Revit-based modeling—was carried out using commercially available hardware and software. Therefore, the methodology presented here can be replicated in similar industrial environments using standard terrestrial laser scanners and Autodesk tools.

2.6. Hardware Configuration and Software Versions

All preprocessing and modeling tasks were performed on mid-range workstations comparable to a Dell G3 15 laptop equipped with an Intel Core i7-9750H CPU, 16 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1660 Ti (Max-Q) GPU. The project team used machines of similar specifications during the three-month modeling and revision period. Autodesk ReCap Pro 2022 was used for point cloud preprocessing and Autodesk Revit 2022 for modeling, while some visualization updates were prepared in Revit 2023. Reporting these specifications provides context for the performance observations discussed in

Section 4.1 and supports the reproducibility and transparency of the digital workflow.

3. Case Study

This section explains how the method used in the study was applied to a real building. The field study was conducted to test the validity of the method and demonstrate the advantages offered by the scan-to-BIM process in digital twin production. For this purpose, an industrial building in Izmir was selected, and the data collection, processing, and modeling stages were implemented sequentially. This section of the study first provides a general overview of the project, then covers the LiDAR-based scanning process, the processes performed in Autodesk ReCap and Revit, and the characteristics of the resulting digital model.

3.1. Project Introduction and Scope

The field study was conducted at an oil production facility in Izmir. The facility was selected because of the need to document the structure’s measurements prior to the renovation of the existing production line.

The main production space considered in this study corresponds to a single factory hall with an approximate floor area of 240 m2. The hall accommodates several vertical tanks, platforms, and a conveyor line, together with a surrounding envelope of walls, windows, and roof elements. This combination of high-bay industrial space and densely arranged mechanical equipment makes the facility a representative test bed for scan-to-BIM applications in production environments.

The factory’s active production process, complex interior structure, and diverse equipment provided a suitable environment for testing the scan-to-BIM method.

The primary objective of the project is to document the current state of the physical structure by creating a three-dimensional digital twin and to plan new machinery layouts.

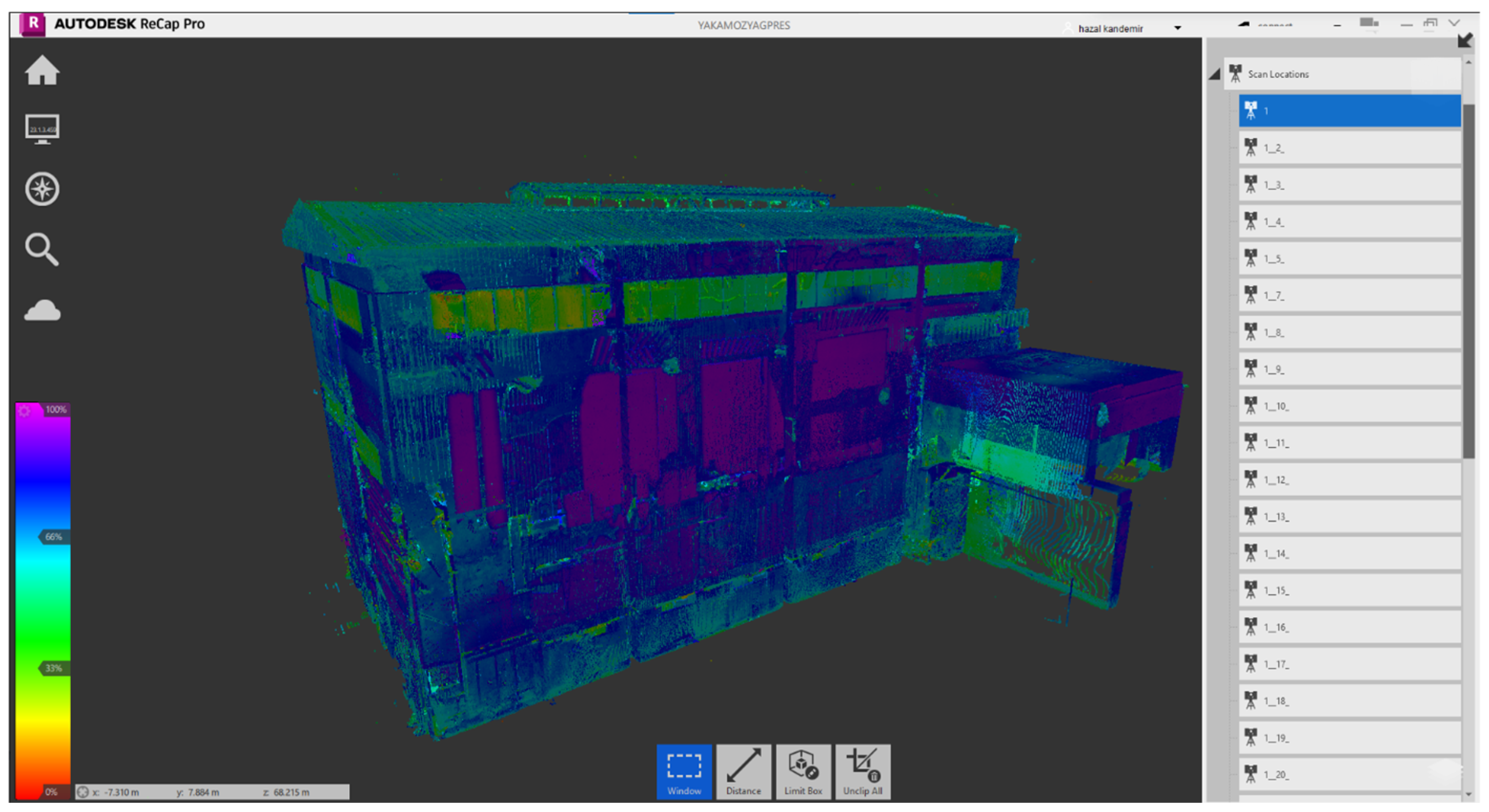

Figure 2 shows multi-point laser scans of the factory exterior aligned in the Autodesk ReCap Pro interface. This figure visually demonstrates the exterior coverage of the scan data and how the point clouds are combined.

3.2. Scanning Process

Scanning operations were conducted in a facility environment where production activities were ongoing. Scanning stations were positioned to cover the entire geometry of the structure, and data was acquired at different elevations and angles. In total, 36 scan locations were used, distributed along the length of the hall and around the exterior facade to capture both the building envelope and the mechanical equipment from multiple viewpoints. The survey was carried out while the factory was in operation, requiring coordination with staff to avoid line-of-sight obstructions and to minimize the presence of moving objects in critical areas.

Environmental conditions, particularly reflections on metal surfaces and moving objects, were factors affecting data quality. These factors were minimized during the data processing phase using noise filtering methods.

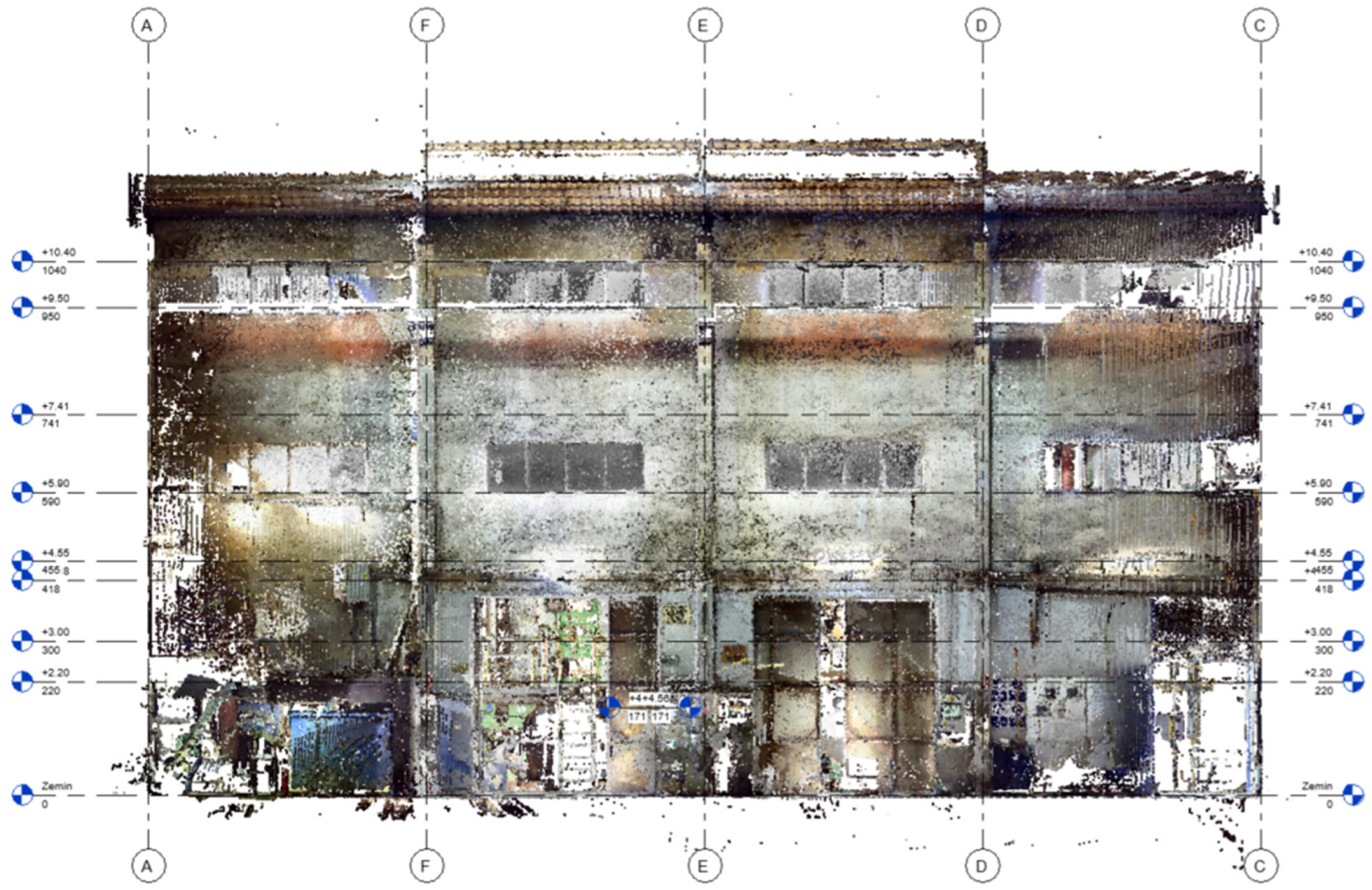

Figure 3 shows an aligned view of multi-point scans performed indoors. This image is important because it demonstrates the density of the scan data and how it is organized in ReCap software.

Additionally,

Figure 4 illustrates an exterior point cloud visualization generated in Autodesk ReCap Pro using density-based coloring. This view highlights the overall spatial distribution of the TLS dataset, showing the point density variations across the facade and roof surfaces. The inclusion of scan locations further demonstrates the geometric richness and the extent of the 4.82 GB dataset collected across 36 scanning stations.

Figure 5 provides a detailed interior point cloud visualization from Autodesk ReCap Pro, illustrating the high-density sampling around tanks, elevated walkways, machinery, and piping systems. This view highlights the geometric complexity of the industrial environment and demonstrates why the resulting TLS dataset reached 4.82 GB. The dense clustering of points in constrained areas also explains the performance limitations discussed in

Section 4.1.

3.3. Data Processing with Autodesk ReCap

Scan data was processed in the Autodesk ReCap Pro environment. The automatic alignment algorithm combined the different scan locations into a single coordinate system.

Unnecessary reflections and erroneous points were removed through manual cleaning processes.

Data accuracy and coverage were analyzed in the ReCap environment using RGB, Intensity, and Scan Location visualization modes.

Registration and cleaning were performed iteratively over several processing sessions, with alignment quality checked visually and via ReCap’s error statistics. The modest size of the ReCap project file (approximately 42.9 kB referencing the scan data) meant that most performance constraints arose later in the BIM environment, rather than during preprocessing.

Figure 6 shows the normal-density RGB view of the factory interior point cloud, corresponding to the scan alignment shown previously in

Figure 3. This figure provides an idea of the data quality before modeling by representing the color-based separation of surfaces and data density.

3.4. Modeling with Autodesk Revit

The point cloud processed in ReCap was added to the Revit as a “linked point cloud.”

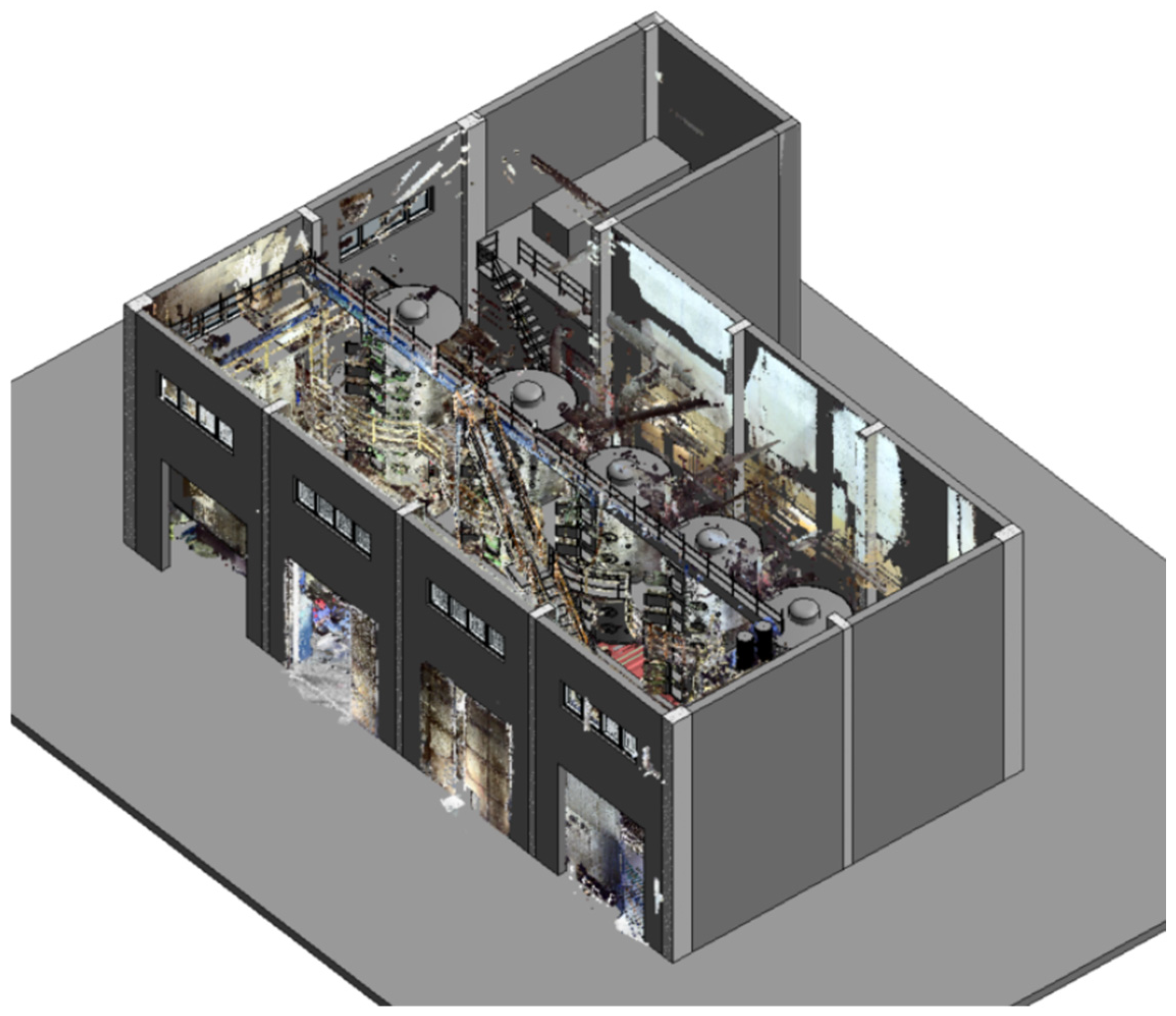

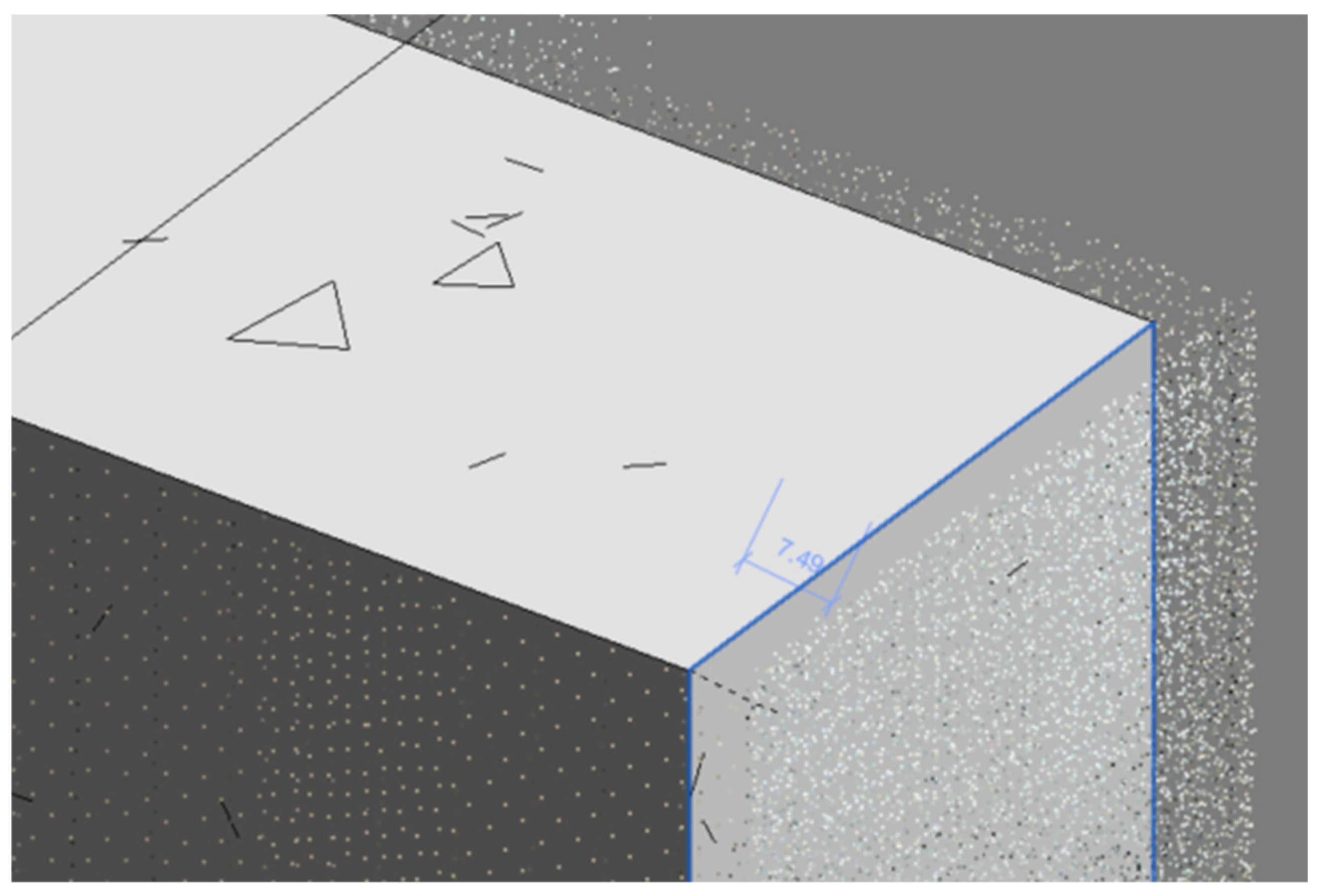

Figure 7 shows the BIM–point cloud overlay in a three-dimensional view, illustrating how the imported TLS dataset was used as a geometric reference during the modeling process.

Figure 8 shows the elevation view in Revit, where point cloud data is aligned with floor elevations. This figure explains how the building elements are aligned with the point cloud during the modeling process.

The modeling infrastructure was created by defining floor elevations and axis systems; structural components (walls, columns, floors, roofs, etc.) were modeled according to the point cloud reference.

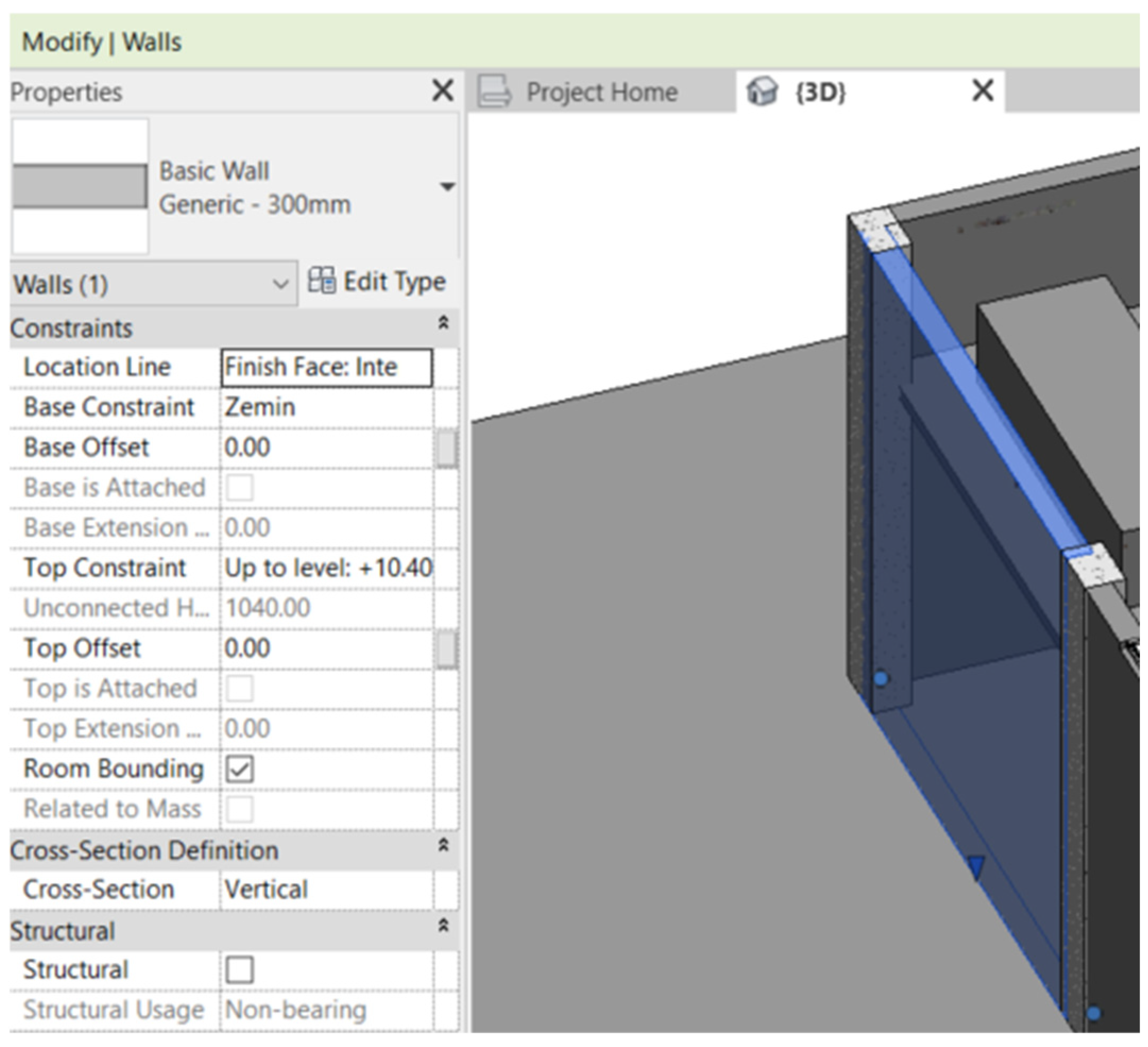

Figure 9 shows the phase where wall parameters are defined in the Revit environment. This phase demonstrates the role of parametric definition of the digital model in improving accuracy.

The modeling level was carried out at a level of detail that ensured the accurate representation of the building geometry.

The machines on the production line were modeled parametrically in the Revit Family module; the digital twin was developed to include both structural and functional components. The modeling work was undertaken by a team of five people over approximately three months of working days, with additional support from interns when required. This effort covered the entire pipeline from point-cloud import to the finalized LOD-300 model and included multiple revision cycles in response to stakeholder feedback.

The resulting Revit project file is relatively compact (12.2 MB). However, the actual performance limitations observed during modeling were caused not by the size of the Revit model but by the high-volume point cloud dataset. The raw terrestrial laser scan data amounted to approximately 4.82 GB, consisting of 609 scan-derived files. This high-volume dataset, rather than the Revit model, was responsible for reduced navigation responsiveness when all 36 scan locations and detailed machine families were visible in the modeling environment.

Finally,

Figure 10 shows a three-dimensional digital twin of the factory, created in Revit, with the point-to-model conversion complete. This figure demonstrates the completed scan-to-BIM process and the digital representation of the physical structure.

5. Conclusions

From an industry perspective, the workflow demonstrated in this study provides practical benefits for facility operators. The digital twin offers a reliable basis for maintenance planning, machinery relocation, safety assessments, and capacity expansion studies. By incorporating production-line machinery into the model, stakeholders gain a more holistic understanding of spatial constraints and workflow interactions—something rarely addressed in conventional architectural or structural digital twin studies.

This study has demonstrated the feasibility and methodological effectiveness of the scan-to-BIM approach in creating a digital twin of an existing industrial building. The integrated use of LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), Autodesk ReCap, and Autodesk Revit software provided a systematic process for transforming raw point cloud data into an accurate and information-rich digital twin model. The findings demonstrate that this workflow ensures geometric accuracy, data integrity, and coordination efficiency during the modeling process.

The ReCap–Revit integration was found to minimize information loss between the scanning and modeling stages and to accelerate the modeling process by transferring LiDAR data directly to the BIM environment. Modeling the production line machines as parametric components in the Revit Family environment enabled the digital twin model to include not only structural but also functional components. Thus, the developed digital twin became an integrated structure representing not only the geometric structure of the factory but also its operational processes. This demonstrates that digital twin technology can support data-driven decision-making in processes such as maintenance, equipment planning, and capacity management.

This study also aims to fill this gap in the literature, given that scan-to-BIM and digital twin applications are still limited in the Turkish context. The field application can be considered one of the first examples of a BIM-based digital twin workflow implemented at an industrial facility scale in Turkey.

However, some limitations of the process were also observed. High-resolution point cloud data increases processing time and requires high hardware capacity. Furthermore, access difficulties in complex industrial environments lead to reduced data density in some regions. Future studies could increase the efficiency, scalability, and real-time capabilities of digital twin production by utilizing AI-supported automation, cloud-based processing, and IoT sensor data integration.

Overall, this study confirms that scan-to-BIM is an effective, repeatable, and data-driven method for digitizing existing buildings. The study provides a robust methodological framework that can contribute to the digital transformation in the construction industry by bridging the gap between physical and digital environments. The presented workflow can serve as a reference model for future digital twin implementations in industrial contexts, supporting Turkey’s ongoing digital transformation in construction.

Future work could focus on integrating real-time IoT sensor data into the digital twin to enable continuous monitoring of equipment performance and environmental conditions. Although no real-time IoT data were integrated in the current implementation, the Revit Families used for key production-line machines already include parameter fields that can serve as placeholders for future sensor IDs and measurement types, enabling a metadata structure that will support direct linkage to live monitoring systems. In addition, AI-based segmentation and automated object recognition could significantly reduce manual modeling time for large industrial facilities. Further research on cloud-based point-cloud processing and lightweight BIM representations could also improve scalability for large and complex industrial environments.