Dynamic Response of an Over-Track Building to Metro Train Loads: A Scale Model Test

Abstract

1. Introduction

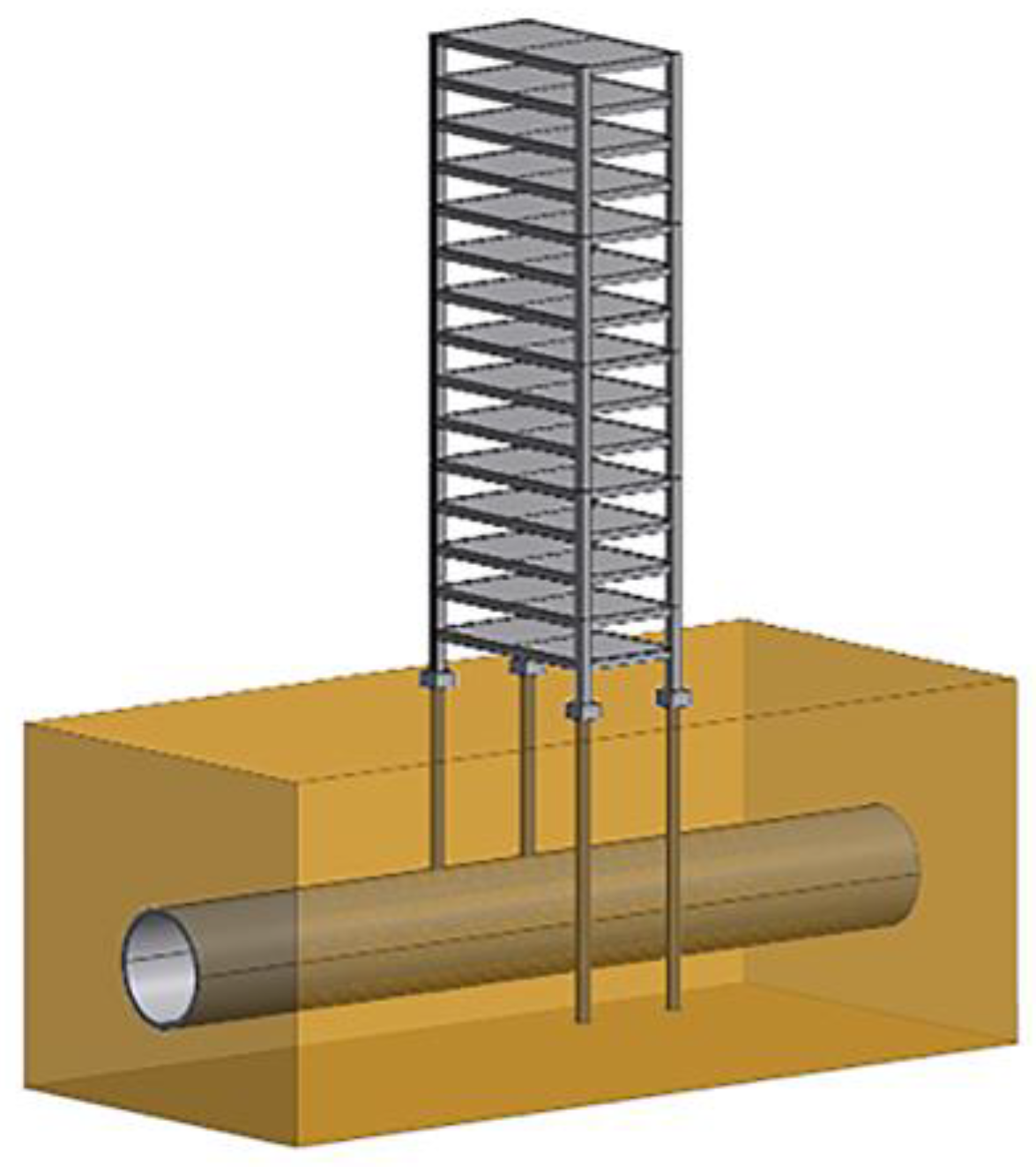

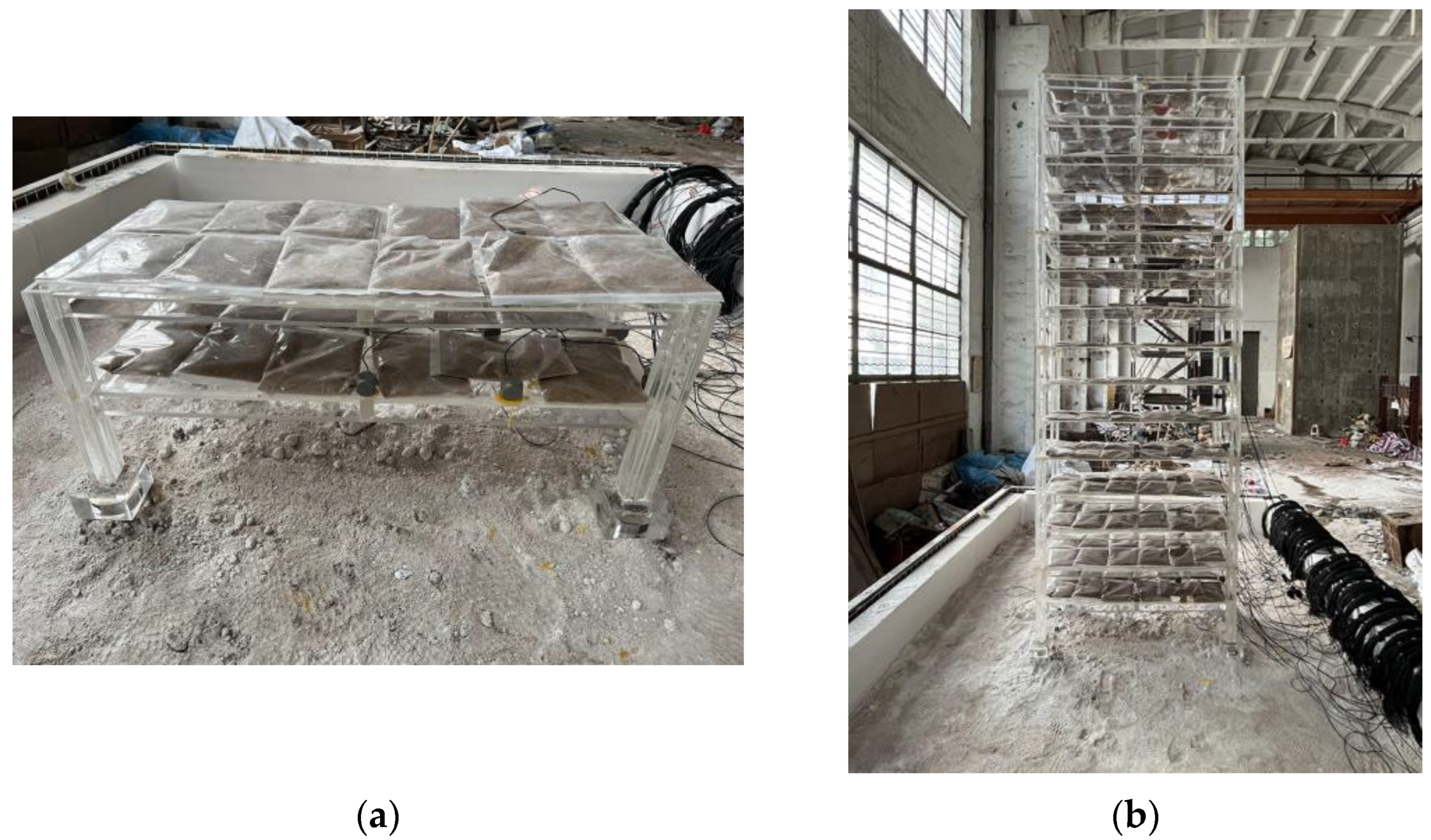

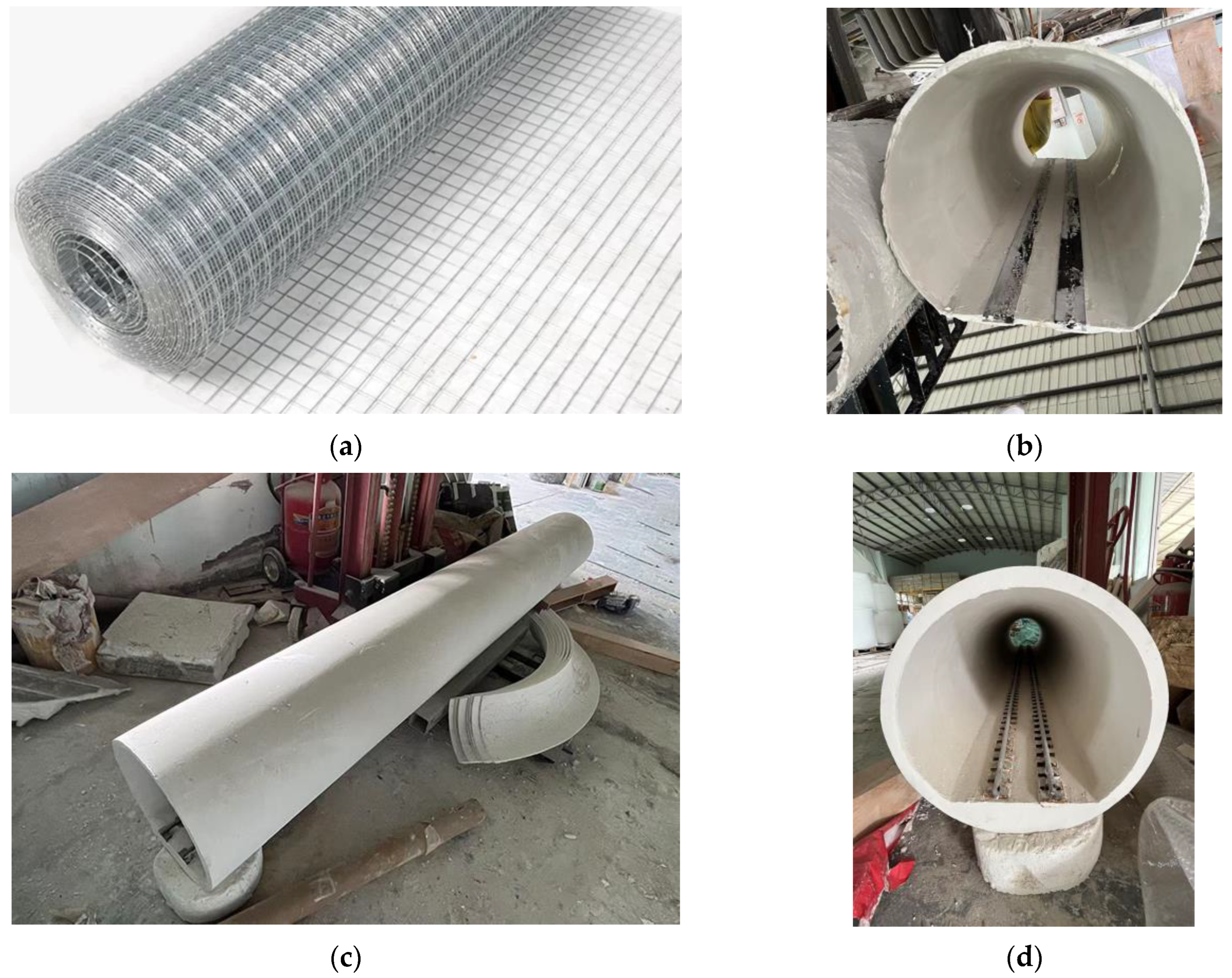

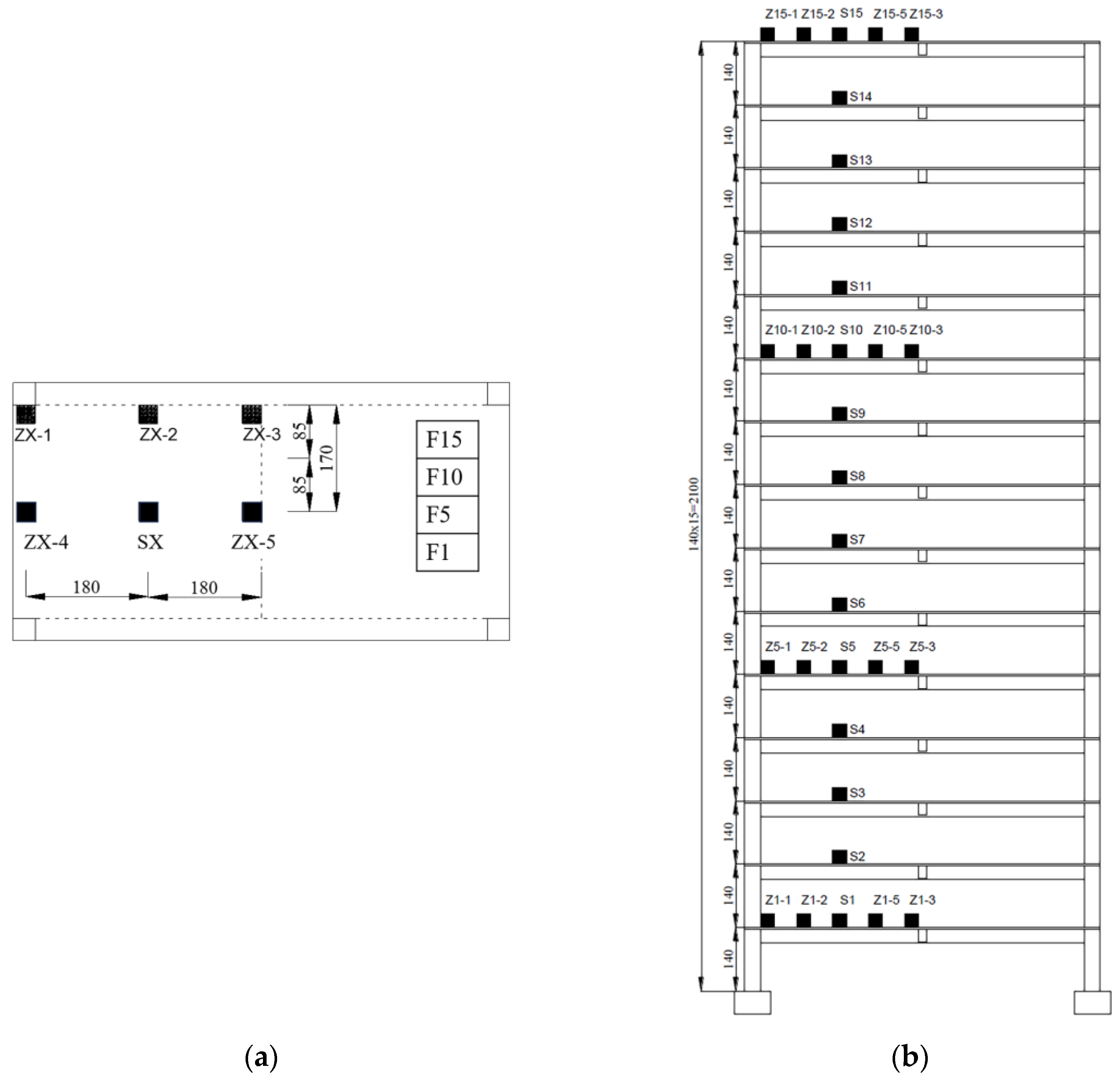

2. Scaled Model Test

2.1. Model Design and Similitude Relationships

- (1)

- Prototype Project

- (2)

- Similitude Design

- (3)

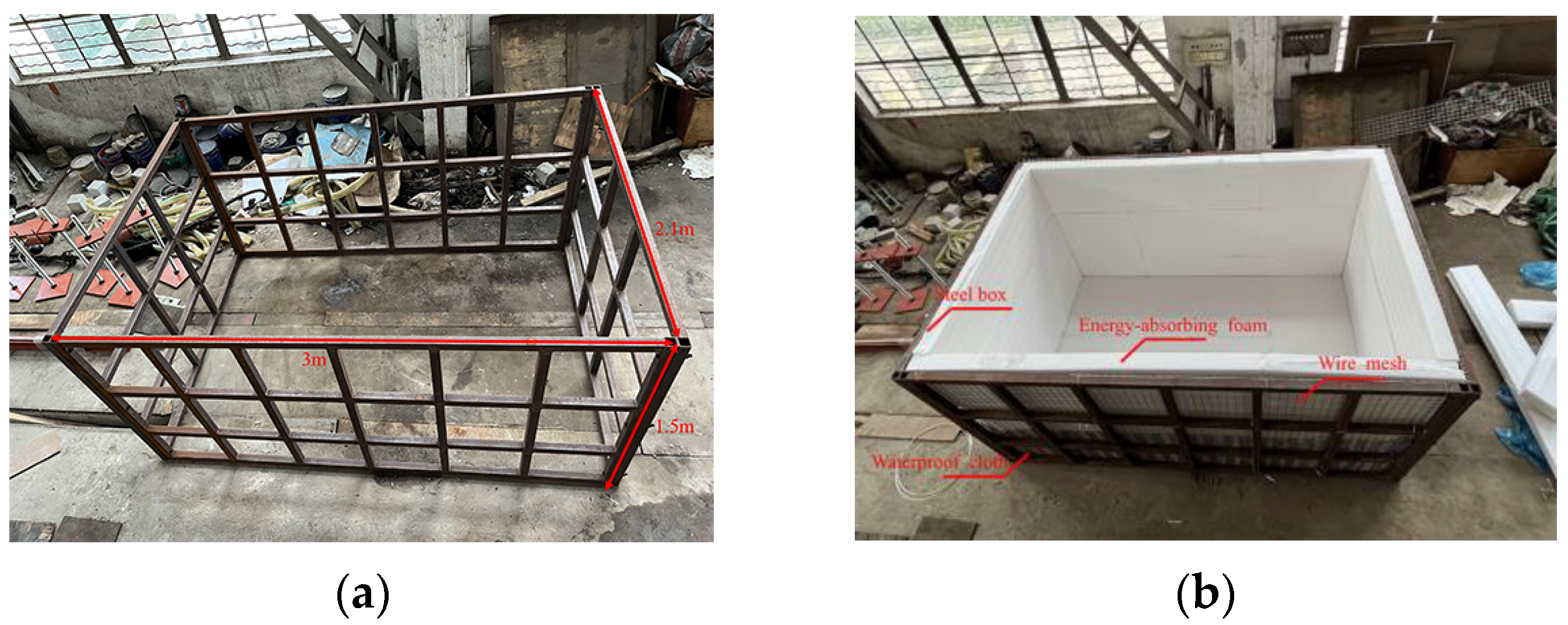

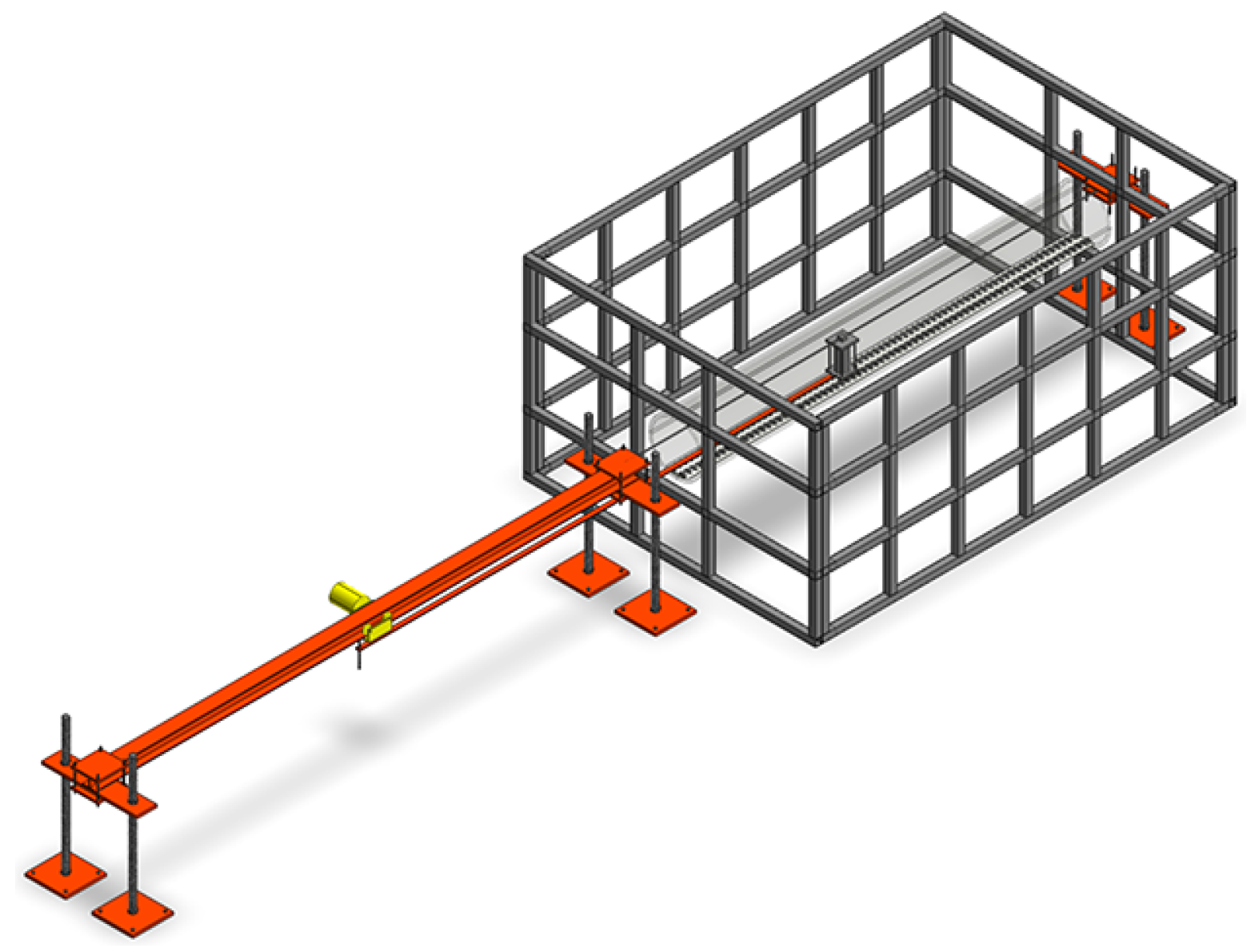

- Model Fabrication

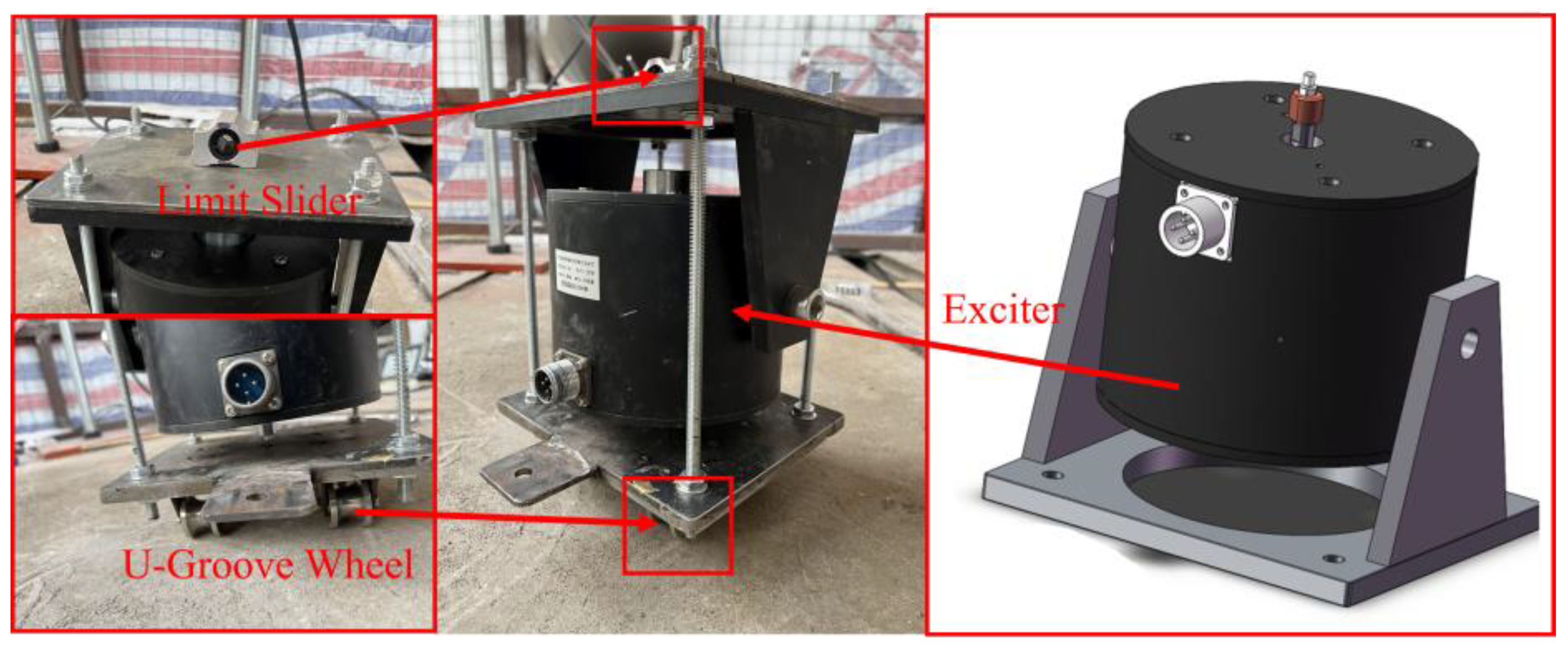

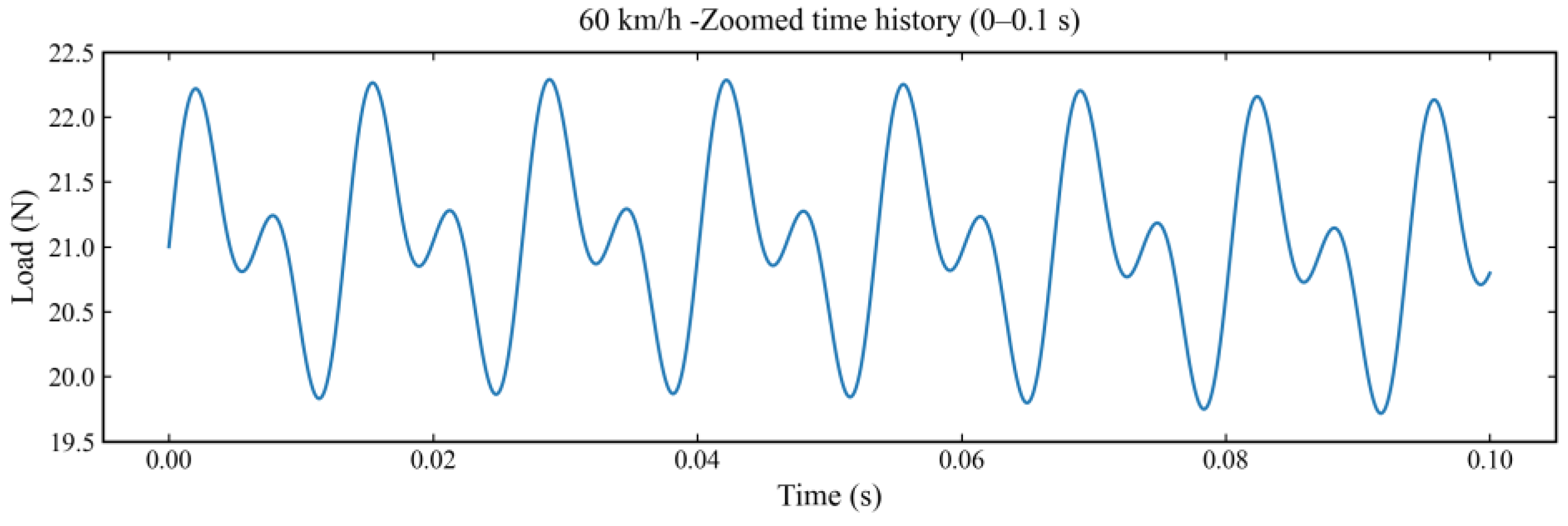

2.2. Dynamic Loading and Data Acquisition

- 1.

- Long-wave (L1 = 10 m, a1 = 3.5 mm): Represents low-frequency irregularities affecting driving stability.

- 2.

- Medium-wave (L2 = 1 m, a2 = 0.3 mm): Represents medium-frequency dynamic additional loads from static geometry irregularity.

- 3.

- Short-wave (L3 = 0.5 m, a1 = 0.07 mm): Represents high-frequency rail surface corrugation and dynamic wheel–rail interaction. To evaluate the validity of the experimental simulation, the load’s temporal and spatial characteristics were rigorously considered. Temporally, the system effectively reproduces the frequency content of the vibration source. By incorporating the specific irregularity parameters (L1, L2, L3) derived from the Guangzhou Metro, the excitation covers the critical frequency bands for ride comfort and wheel–rail interaction. Spatially, while the single moving cart represents a simplification of a multi-axle train, it captures the fundamental moving nature of the load. This setup successfully simulates the essential “scanning effect” and transient wave propagation phenomena, which are the primary spatial factors influencing vibration transmission in this study, distinguishing it from traditional fixed-point excitation methods.

2.3. Test Cases

3. Results and Discussion

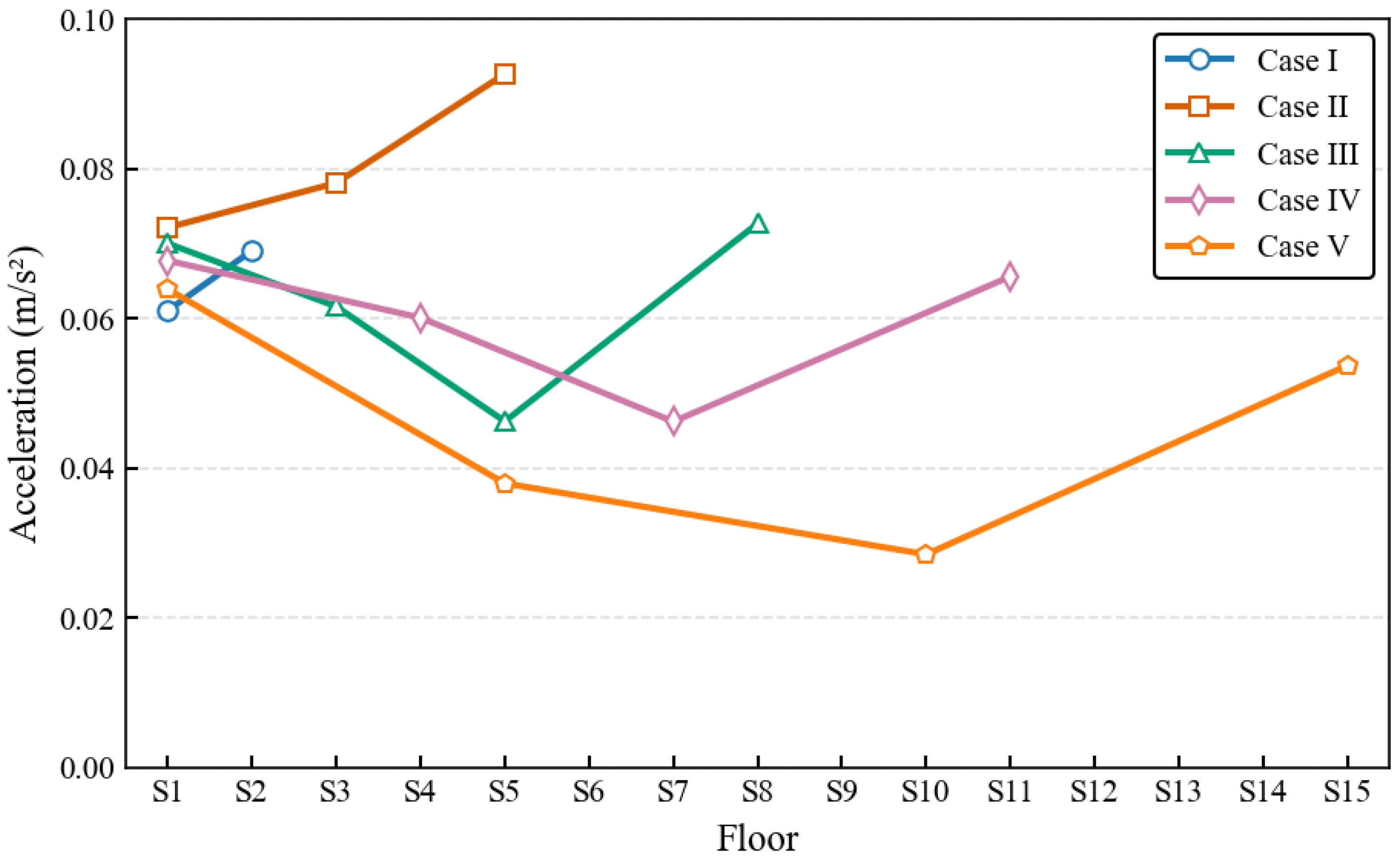

3.1. Effect of Building Height on Vibration Response Distribution

- (a)

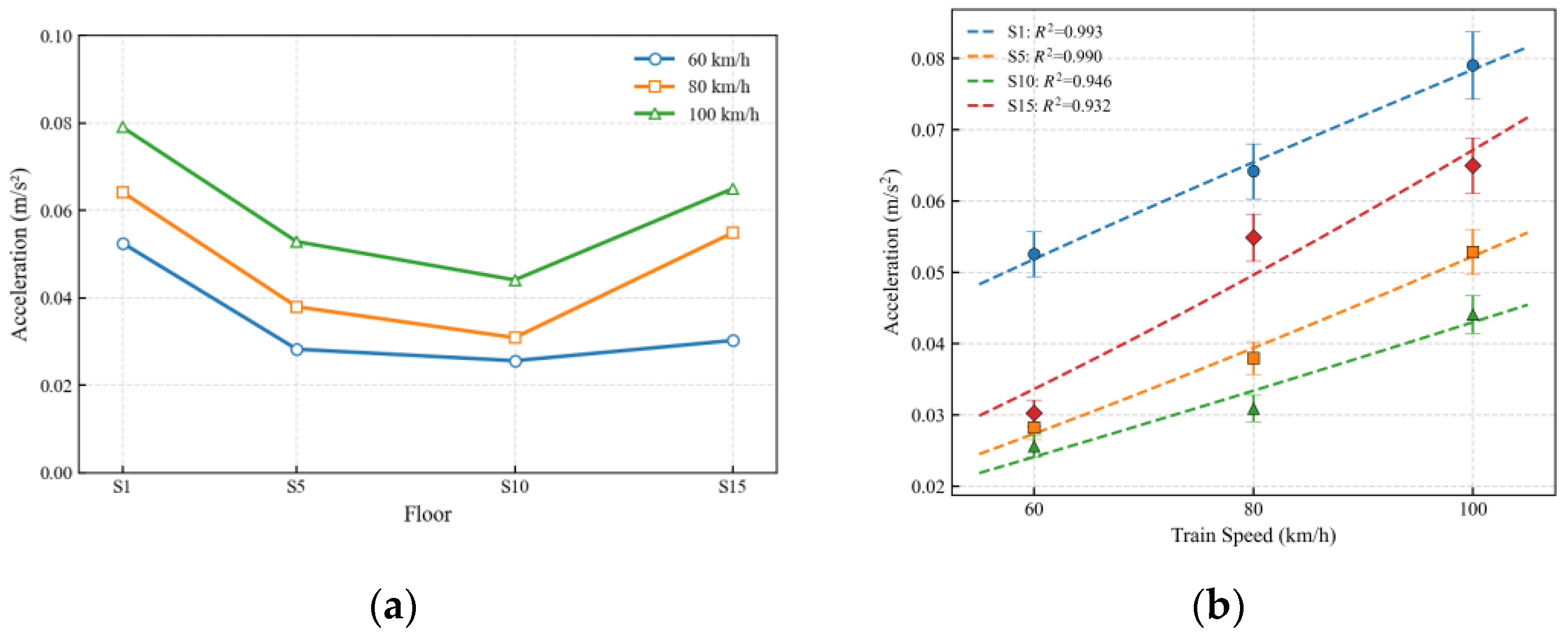

- Deeper and Wider Attenuation Zone: As the number of stories increases, the attenuation zone in the middle portion of the structure becomes more pronounced. In the 15-story structure (Case V), the PGA at the S10 measurement point was approximately 0.029 m/s2, which is less than half of the PGA at the base (S1), recorded at about 0.063 m/s2.

- (b)

- Upward Shift in the Attenuation Minimum: The location of the minimum response point shifts upward with increasing building height. It migrates from the S5 floor in Case III, to the S7 floor in Case IV, and ultimately reaches the S10 floor in Case V. This phenomenon is closely correlated with the shape of the structure’s dominant mode, as the point of maximum attenuation generally corresponds to a modal node or a region of minimal modal contribution.

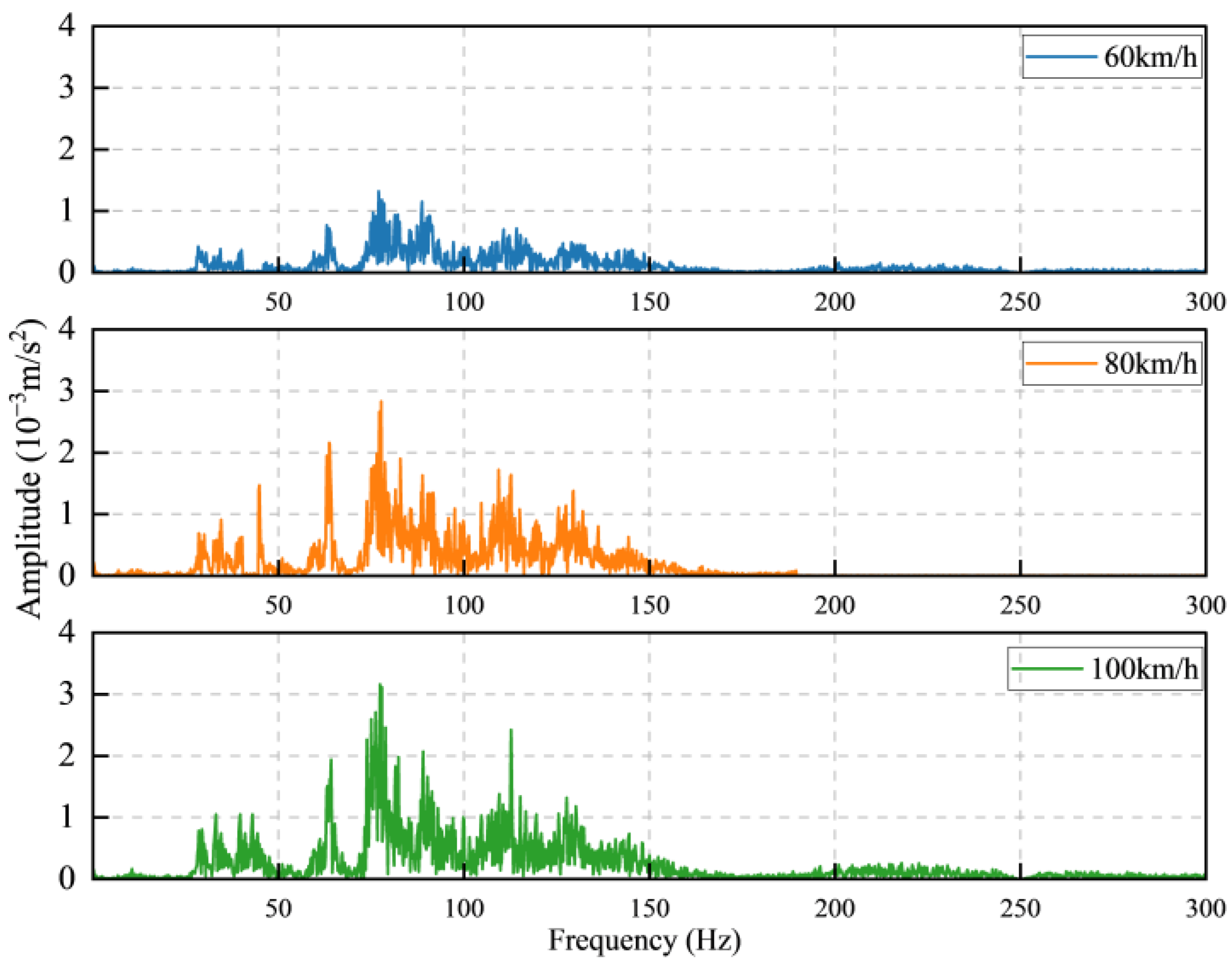

3.2. Effect of Train Speed on Vibration Response

4. Conclusions

- (1)

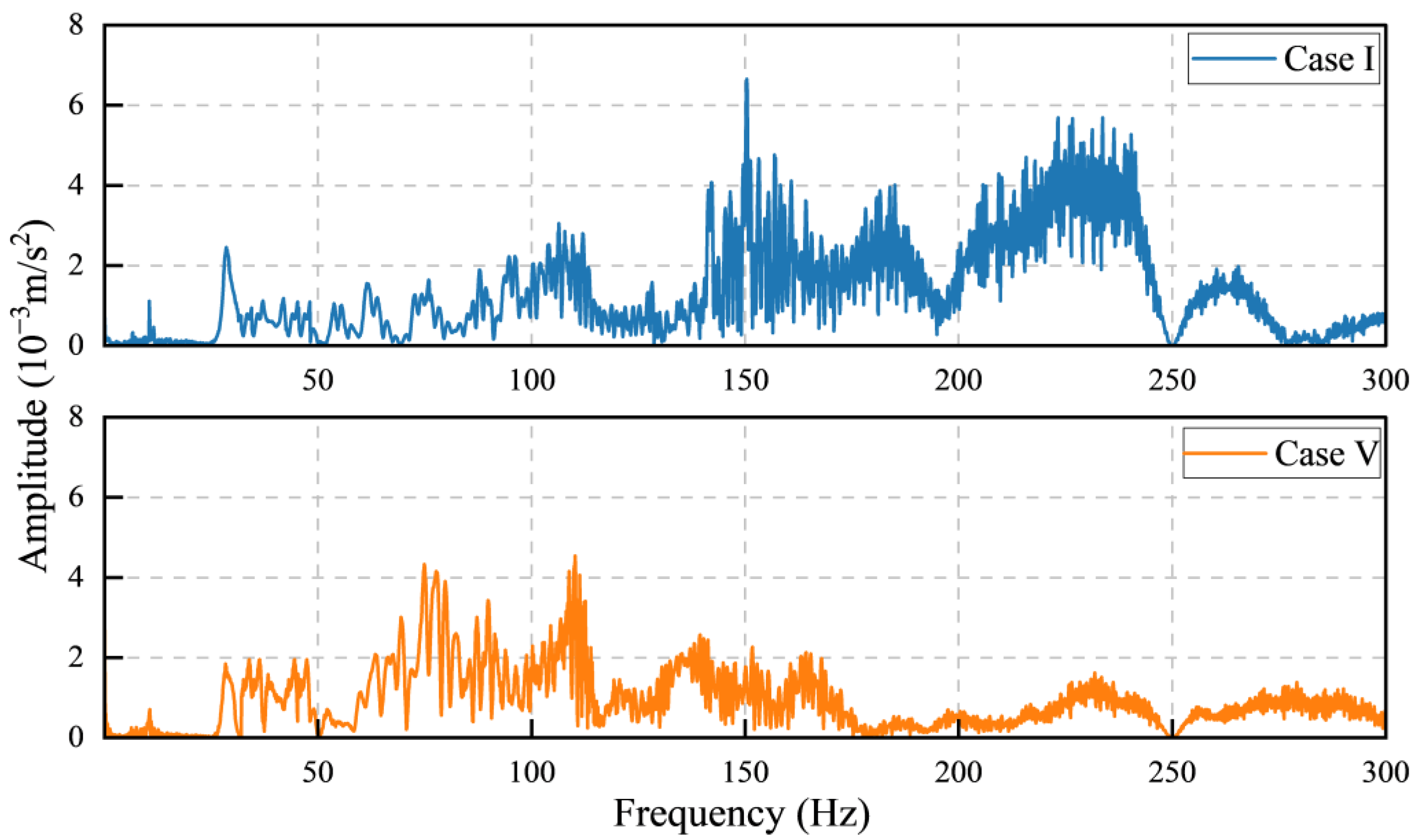

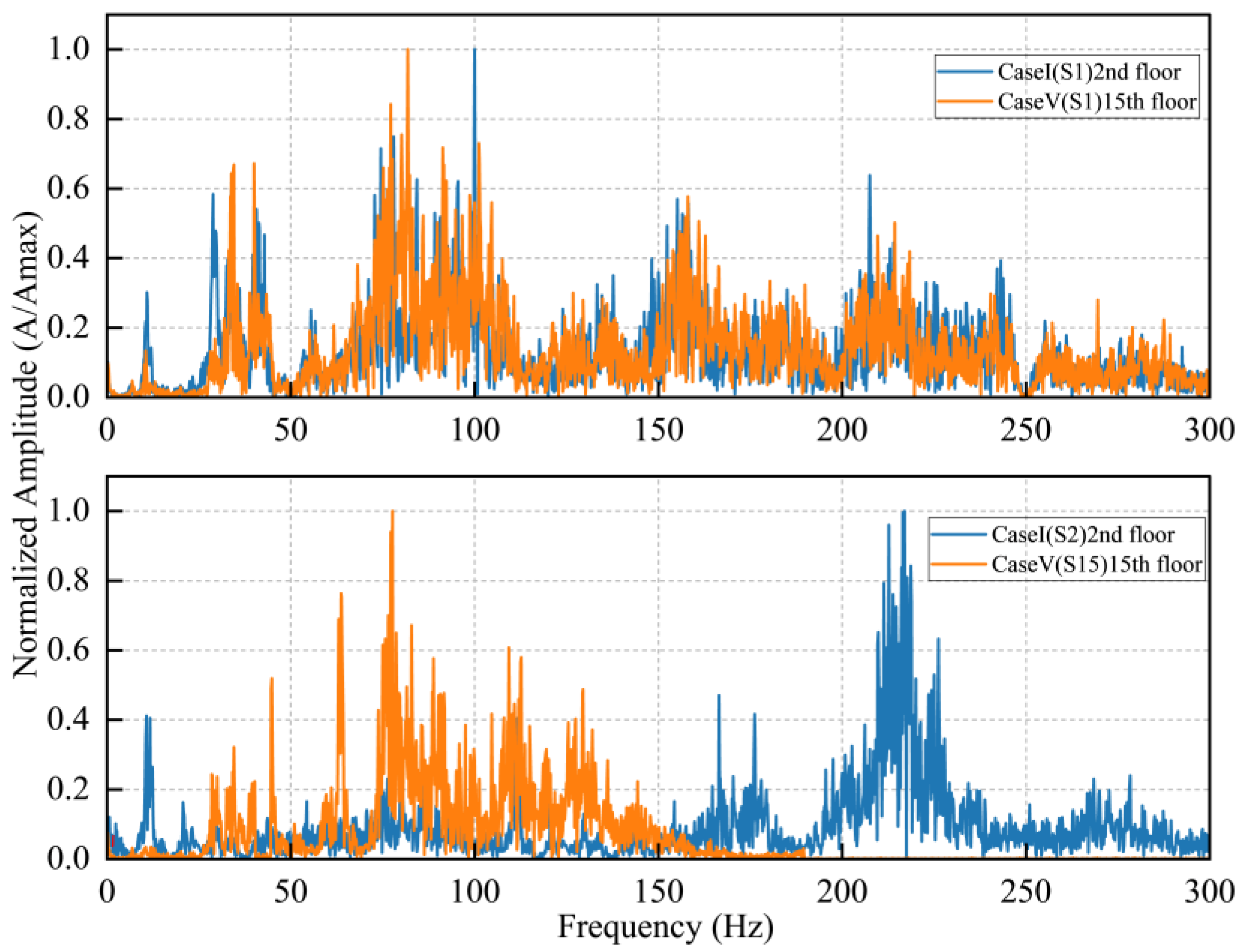

- Evolution of Structural Dynamics: Building height acts as a primary parameter influencing the dynamic behavior of over-track structures. As the height increases, the structure transitions from a “high-frequency, rigid” system to a “low-frequency, flexible” system. This shift is characterized by a notable decrease in the fundamental frequency (from approximately 230 Hz to 100 Hz in this study), which fundamentally alters the vibration transmission mechanism.

- (2)

- Height-Dependent Propagation Patterns: The variation in dynamic properties leads to two distinct vibration propagation patterns. Low-rise structures (≤5 stories) exhibit a “monotonic amplification” trend. In contrast, high-rise flexible structures (≥8 stories) display an “attenuation-followed-by-amplification” profile. This phenomenon indicates that the filtering effect of the structure becomes more dominant as the number of stories increases.

- (3)

- Distinct Roles of Speed and Structure: The effects of train speed and structural modes on the vibration response operate through distinct mechanisms. Train speed primarily scales the overall response amplitude, showing a strong linear correlation (R2 > 0.93). Meanwhile, the spatial distribution of vibration along the building’s height is governed primarily by the structure’s intrinsic modal properties, remaining consistent across different speeds.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kedia, N.K.; Kumar, A. A Review on Vibration Generation Due to Subway Train and Mitigation Techniques. In Geotechnics for Transportation Infrastructure; Sundaram, R., Shahu, J.T., Havanagi, V., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Seyedi, M. Impact of Train-Induced Vibrations on Residents’ Comfort and Structural Damages in Buildings. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2024, 12, 1961–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, J.; Rabiee, S.; Khajehdezfuly, A. Development of Train Ride Comfort Prediction Model for Railway Slab Track System. Lat. Am. J. Solids Struct. 2020, 17, e304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.G.; Ögren, M.; Ageborg Morsing, J.; Persson Waye, K. Effects of Ground-Borne Noise from Railway Tunnels on Sleep: A Polysomnographic Study. Build. Environ. 2019, 149, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, W.; Liang, J.; Chen, G. 2D Dynamic Tunnel-Soil-Aboveground Building Interaction I: Analytical Solution for Incident Plane SH-Waves Based on Rigid Tunnel and Foundation Model. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 128, 104625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, G.; Massimino, M.R. Numerical Modelling of the Seismic Response of a Tunnel–Soil–Aboveground Building System in Catania (Italy). Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2017, 15, 469–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Mao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, H. Numerical Investigations on the Dynamic Responses of Metro Tunnel-Soil-Ground Building under Oblique Incidence of Seismic Wave. Structures 2023, 58, 105450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Cao, Q.; Lu, S.; Xu, H.; Yuan, D.; Bai, X. Experimental and Numerical Study on the Seismic Response of a Surface Frame Structure–Soil–Double-Tunnel System. Int. J. Geomech. 2024, 24, 04024073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, D.; Luo, W.; Li, J.; He, Z. Shaking Table Test of Vertical Isolation Performances of Super High-Rise Structure under Metro Train-Induced Vibration. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 82, 108323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanayei, M.; Maurya, P.; Moore, J.A. Measurement of Building Foundation and Ground-Borne Vibrations Due to Surface Trains and Subways. Eng. Struct. 2013, 53, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanayei, M.; Kayiparambil, P.A.; Moore, J.A.; Brett, C.R. Measurement and Prediction of Train-Induced Vibrations in a Full-Scale Building. Eng. Struct. 2014, 77, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Chen, J.; Wei, P.; Xia, C.; De Roeck, G.; Degrande, G. Experimental Investigation of Railway Train-Induced Vibrations of Surrounding Ground and a Nearby Multi-Story Building. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2009, 8, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Wang, Y.; Moore, J.A.; Sanayei, M. Train-Induced Field Vibration Measurements of Ground and over-Track Buildings. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 575, 1339–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Zou, C.; Liu, Q.; Li, X.; Tao, Z. Floor Vibration Predictions Based on Train-Track-Building Coupling Model. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 89, 109340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, M.; Lu, F.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Gao, S.; Zhang, R. Research on the Vibration Response and Control Technologies for Buildings above the Metro Depot. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 109, 112908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Tao, Z. Building Vibration Measurement and Prediction during Train Operations. Buildings 2024, 14, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Liu, W.; Qian, C.; Deng, G.; Li, Y. Study of the Train-Induced Vibration Impact on a Historic Bell Tower above Two Spatially Overlapping Metro Lines. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2016, 81, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Xu, L.; Du, L.; Wu, Z.; Tan, X. Prediction of Building Vibration Induced by Metro Trains Running in a Curved Tunnel. J. Vib. Control 2021, 27, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Moore, J.A.; Sanayei, M.; Wang, Y. Impedance Model for Estimating Train-Induced Building Vibrations. Eng. Struct. 2018, 172, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, J.; Vasheghani, M. Safety of Buildings against Train Induced Structure Borne Noise. Build. Environ. 2021, 197, 107784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Li, L.; Shang, Y.; Yan, Q.; Fang, Y.; He, C.; Xu, Z. An Experimental Study of the Dynamic Response of Shield Tunnels under Long-Term Train Loads. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 79, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Cheng-ping, Z.; Liu, D.; Tu, J.; Yan, Q.; Fang, Y.; He, C. The Effect of Cross-Sectional Shape on the Dynamic Response of Tunnels under Train Induced Vibration Loads. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 90, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, W.; Yao, C.; Xu, Z. Centrifuge Modelling of the Dynamic Response of Twin Tunnels under Train-Induced Vibration Load. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2024, 185, 108908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Yang, W.; Qian, Z.; Yang, L.; He, C.; Qu, S. The Effect of Internal Structure on Dynamic Response of Road-Metro Tunnels under Train Vibration Loads: An Experimental Study. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 138, 105182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.; Jones, C.J.C.; Thompson, D.J. A Comparison of a Theoretical Model for Quasi-Statically and Dynamically Induced Environmental Vibration from Trains with Measurements. J. Sound Vib. 2003, 267, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sanayei, M.; Moore, J.A.; Zou, C. Experimental Study of Train-Induced Vibration in over-Track Buildings in a Metro Depot. Eng. Struct. 2019, 198, 109473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yuan, M.; Miao, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y. Experimental Study on Seismic Response of Underground Tunnel-Soil-Surface Structure Interaction System. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 76, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Huang, X.; Sun, M.; Xu, L.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, Q. Experimental Study on the Influence of Cracks on Tunnel Vibration under Subway Train Load. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 142, 105444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H.H.; Stephenson, J.E.; Clayton, G.A.; Morland, G.W.; Lyon, D. The effect of track and vehicle parameters on wheel/rail vertical dynamic forces. Railw. Eng. J. 1974, 3, 2–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, C.S.; Pande, G.N. Preliminary deterministic finite element study on a tunnel driven in loess subjected to train loading. J. Civil Eng. 1984, 17, 18–28, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- He, P.-P.; Cui, Z.-D. Dynamic Response of a Thawing Soil around the Tunnel under the Vibration Load of Subway. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 73, 2473–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Yin, R.; Lei, M.; Deng, E.; Zhang, P. Vibratory Influential Zoning for Grade-Separated Tunnels Under the Load of Trains. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2018, 36, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Physical Quantity | Relationship | Similarity Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometry | Length | 20 | |

| Displacement | 20 | ||

| Area | 400 | ||

| Material Property | Stress | 20 | |

| Strain | 1 | ||

| Elastic Modulus | 20 | ||

| Density | 1 | ||

| Load Property | Concentrated Load | 8000 | |

| Surface Load | 20 | ||

| Dynamic Property | Time | 4.472 | |

| Frequency | 0.224 | ||

| Velocity | 4.472 | ||

| Acceleration | 1 |

| Structure | Type | ρ (kg/m3) | E (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tunnel lining | Prototype | 2400 | 34.5 |

| Theoretical model | 2400 | 1.725 | |

| Actual model | 2320 | 1.7 | |

| Track bed | Prototype | 2400 | 30 |

| Theoretical model | 2400 | 1.5 | |

| Actual model | 2320 | 1.7 |

| Category | ρ (kg/m3) | E (MPa) | VS (m/s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prototype soil | 1730 | 40 | 170.3 | 0.3 |

| Theoretical model soil | 1730 | 2.0 | 38.1 | 0.3 |

| Actual model soil | 1705 | 2.1 | 40.4 | 0.32 |

| Floor Level | Train Speed (km/h) | Frequency Range (Hz) |

|---|---|---|

| 2nd floor (Case I) | 60/80/100 | 0–1000 |

| 5th floor (Case II) | 60/80/100 | 0–1000 |

| 8th floor (Case III) | 60/80/100 | 0–1000 |

| 11th floor (Case IV) | 60/80/100 | 0–1000 |

| 15th floor (Case V) | 60/80/100 | 0–1000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, B.; Qin, F.; Liu, S.; Huang, Z.; Li, Y. Dynamic Response of an Over-Track Building to Metro Train Loads: A Scale Model Test. Buildings 2025, 15, 4468. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244468

Zhang B, Qin F, Liu S, Huang Z, Li Y. Dynamic Response of an Over-Track Building to Metro Train Loads: A Scale Model Test. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4468. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244468

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Bin, Fengming Qin, Sinan Liu, Zipeng Huang, and Yadong Li. 2025. "Dynamic Response of an Over-Track Building to Metro Train Loads: A Scale Model Test" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4468. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244468

APA StyleZhang, B., Qin, F., Liu, S., Huang, Z., & Li, Y. (2025). Dynamic Response of an Over-Track Building to Metro Train Loads: A Scale Model Test. Buildings, 15(24), 4468. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244468