A Multi-Segment Beam Approach for Capturing Member Buckling in Seismic Stability Analysis of Space Truss Structures

Abstract

1. Introduction

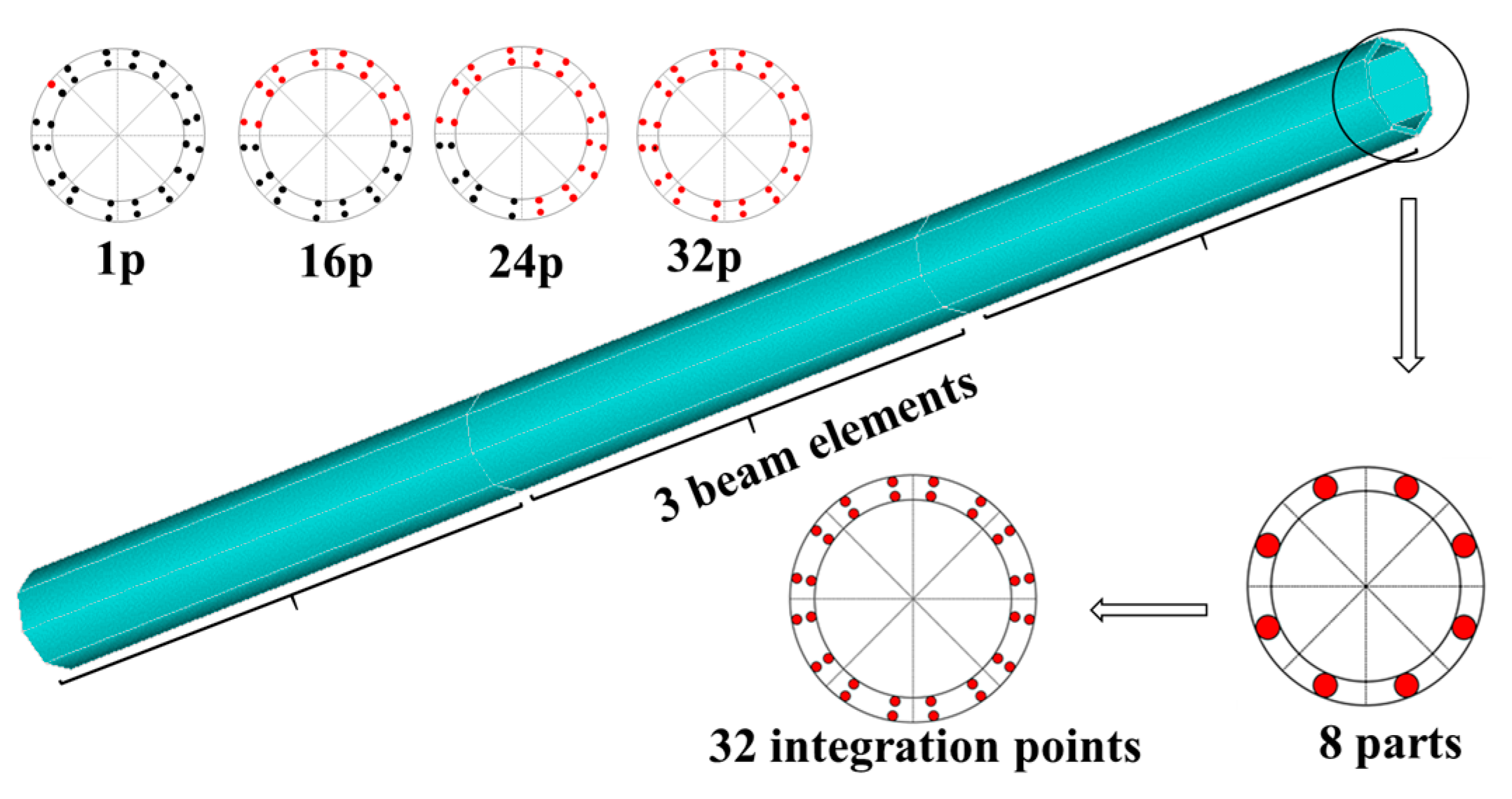

2. The Multi-Segment Beam Method

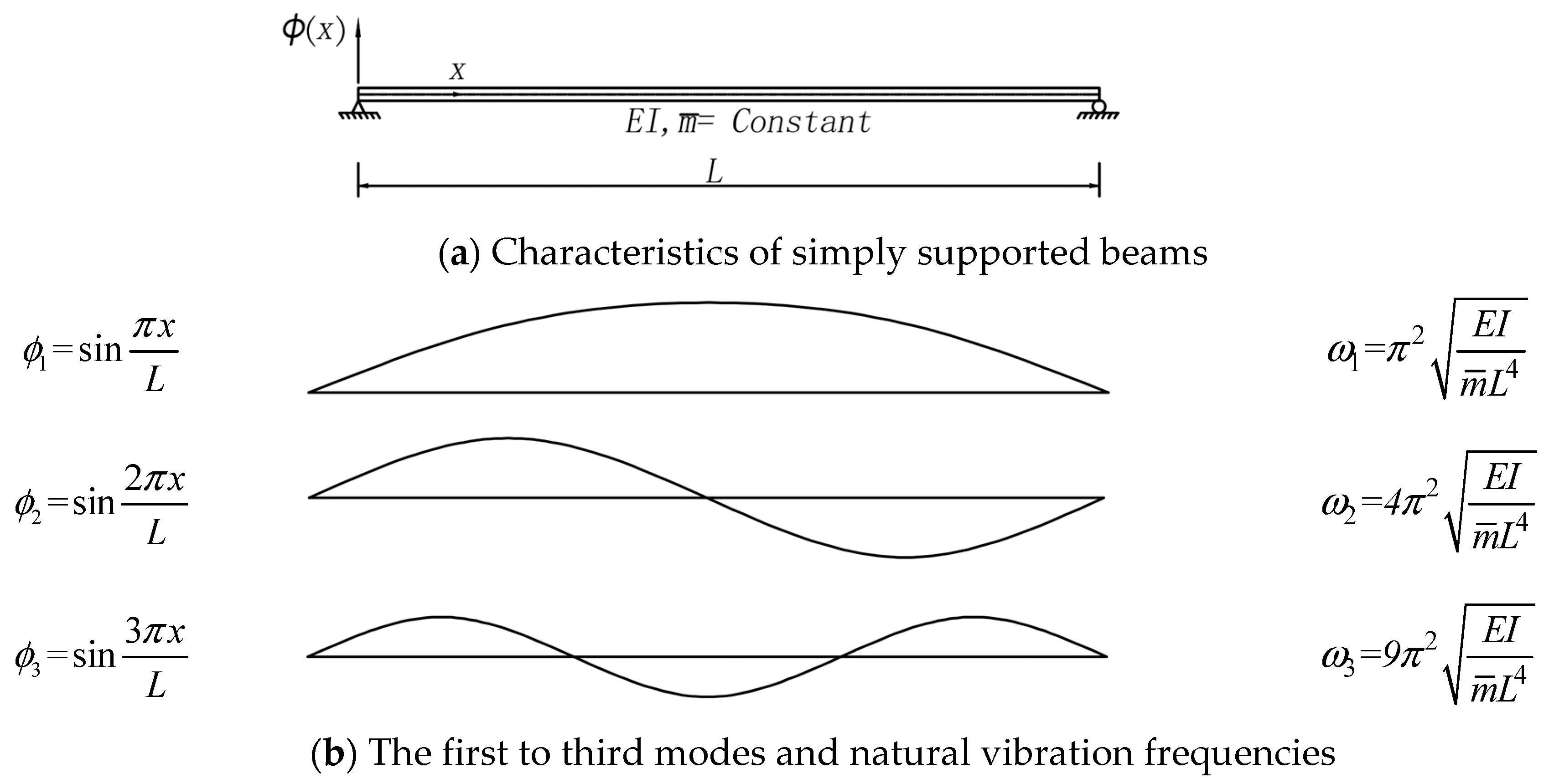

2.1. Modal Analysis of Simply Supported Beams

2.1.1. Approximate Solution in Modal Analysis of Simply Supported Beams

- (1)

- Rayleigh method for modal analysis of simply supported beams

- ①

- Supposing that the shape function is a parabola, , then the following is obtained:

- ②

- Assuming a sinusoidal form for the shape function, , we obtain the following:

- (2)

- Finite element method for modal analysis of simply supported beams

2.1.2. Numerical Simulation of Modal Analysis of Simply Supported Beams

2.2. Modal Analysis of a Space Truss

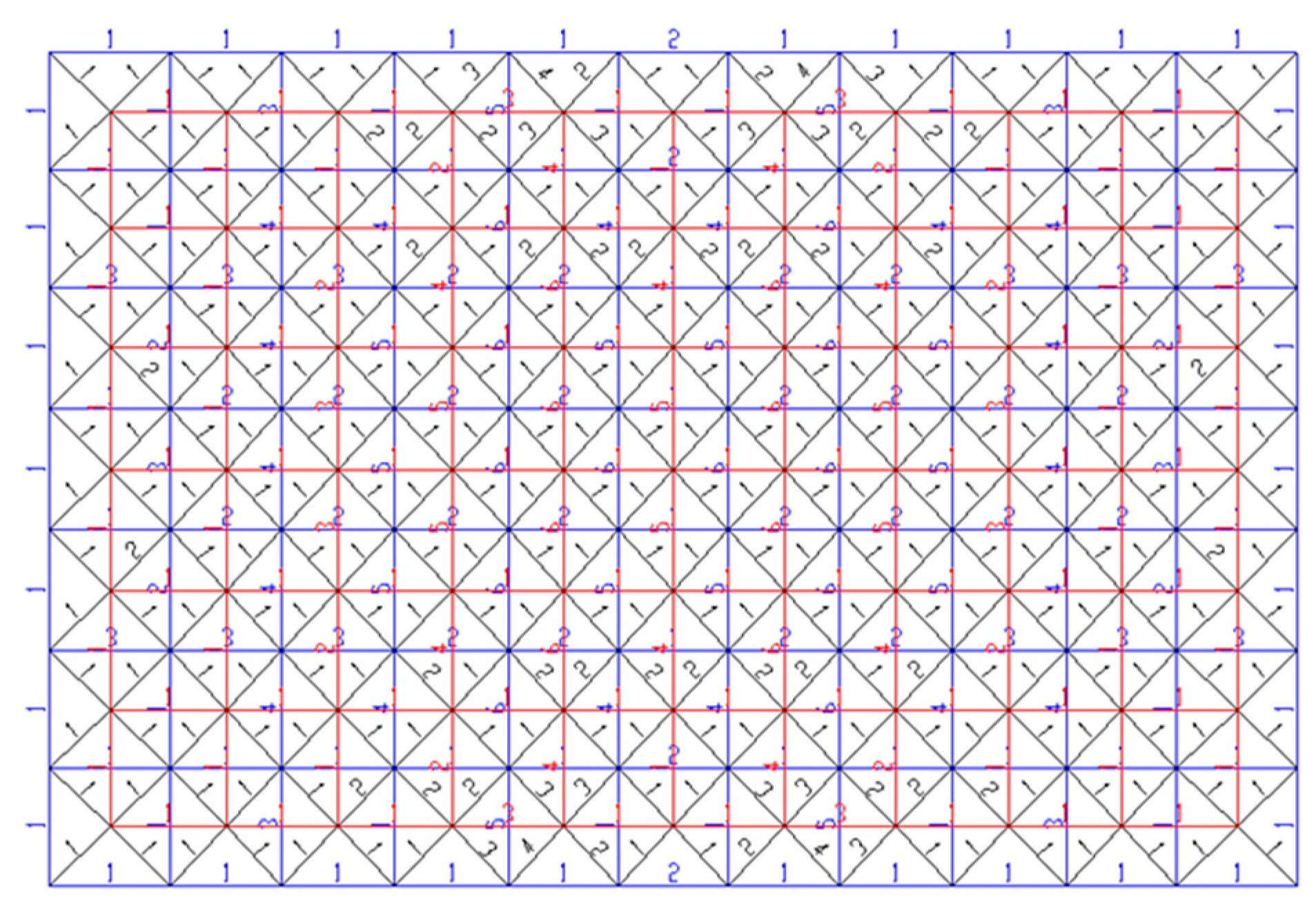

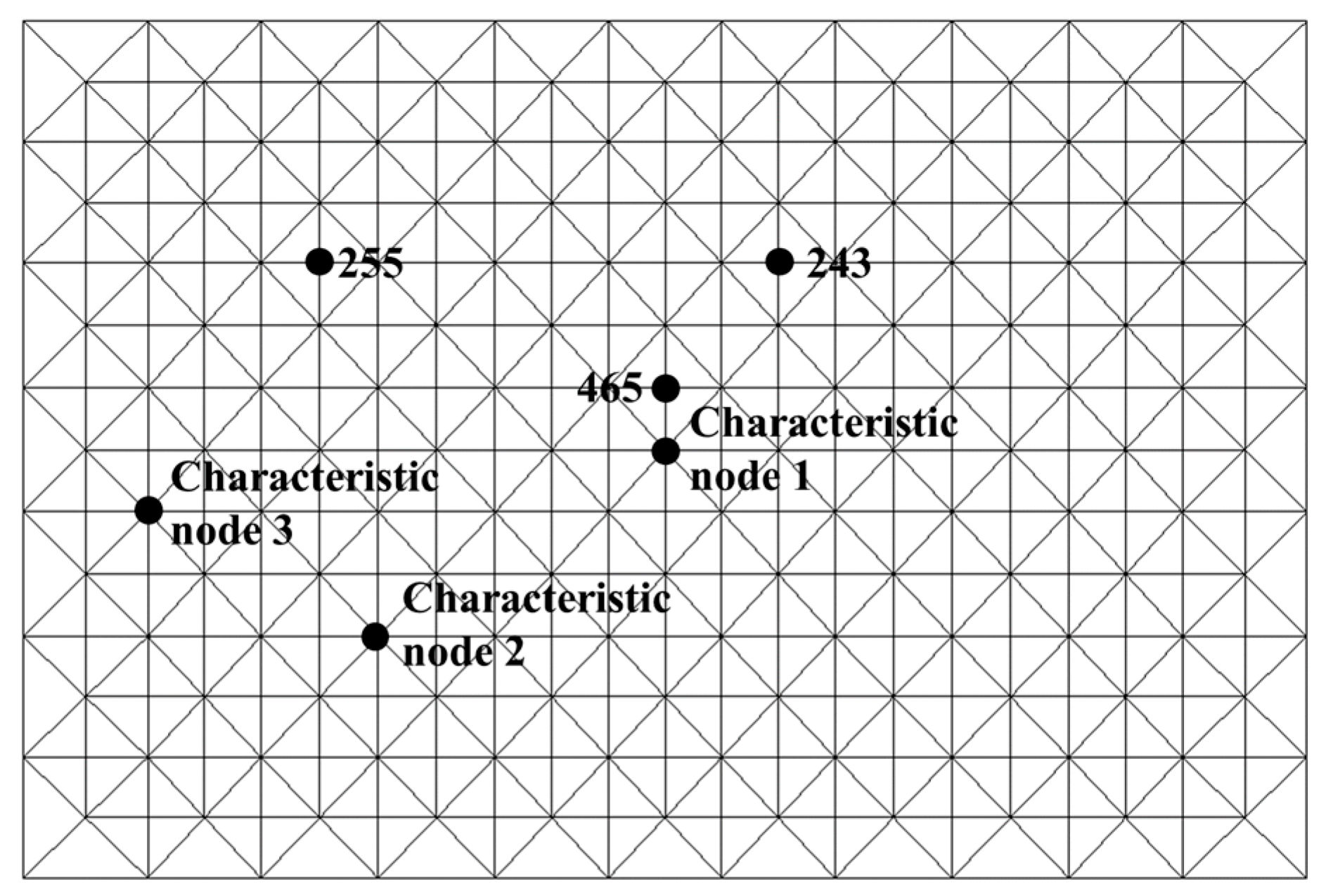

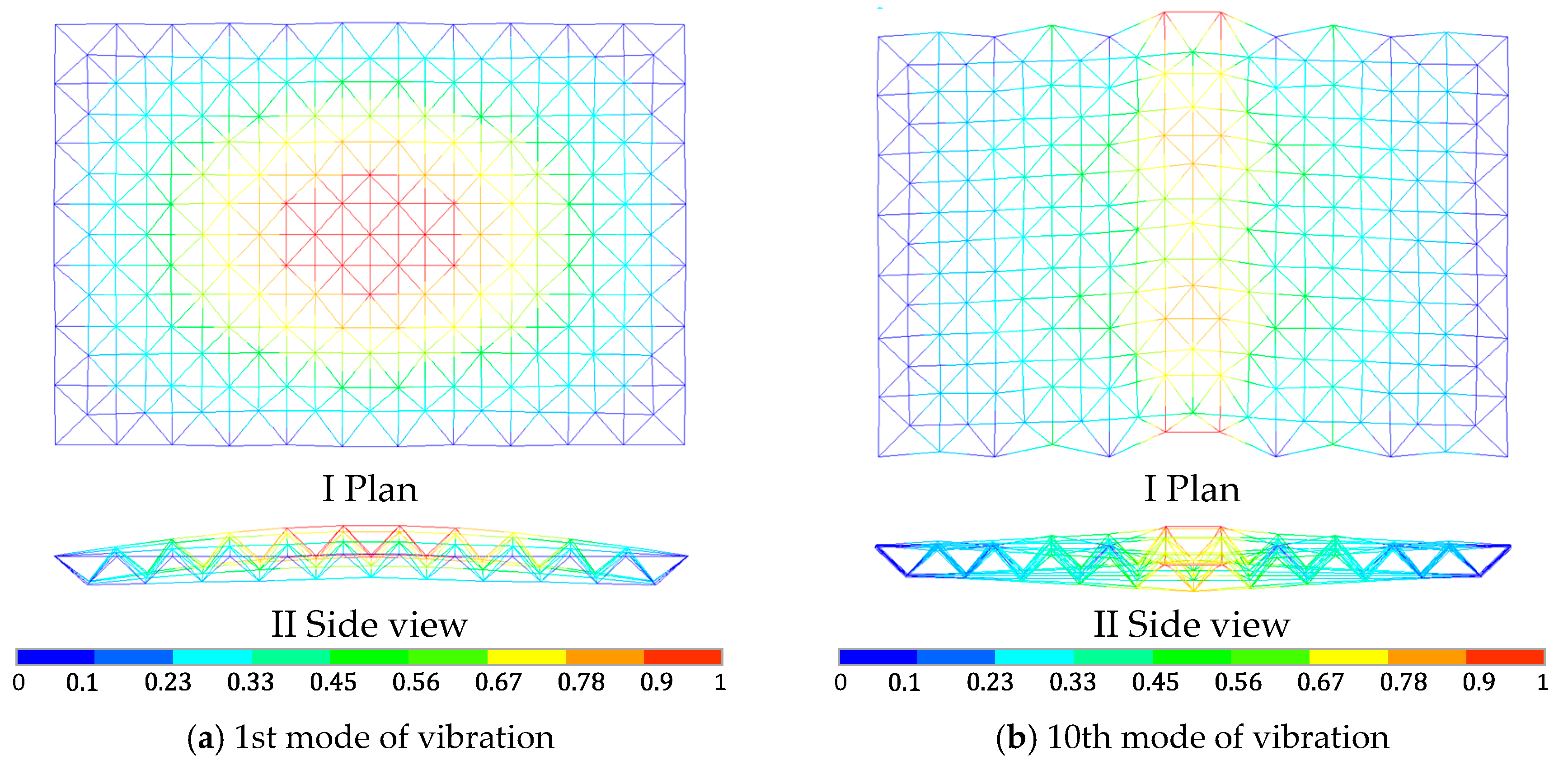

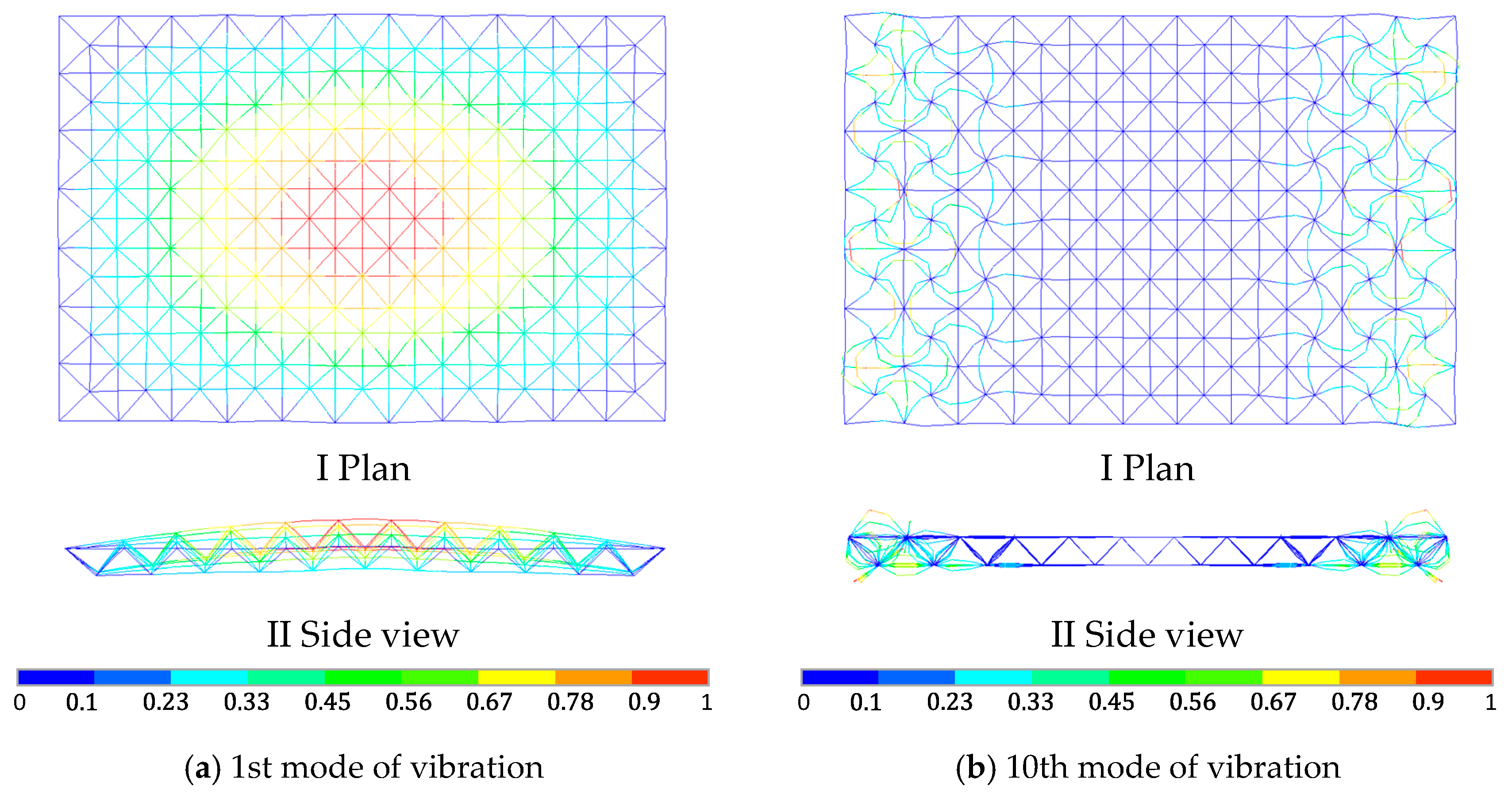

2.2.1. Modal Analysis of the Space Truss Alone

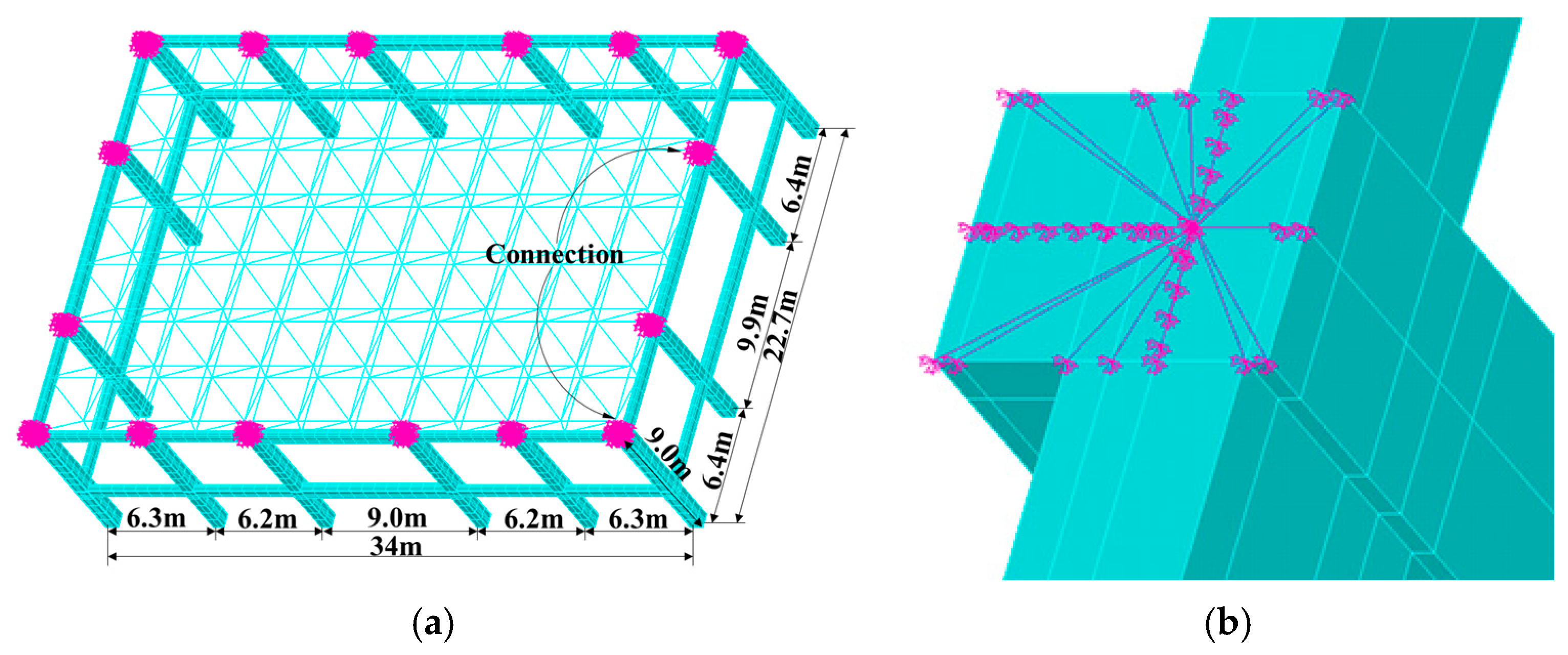

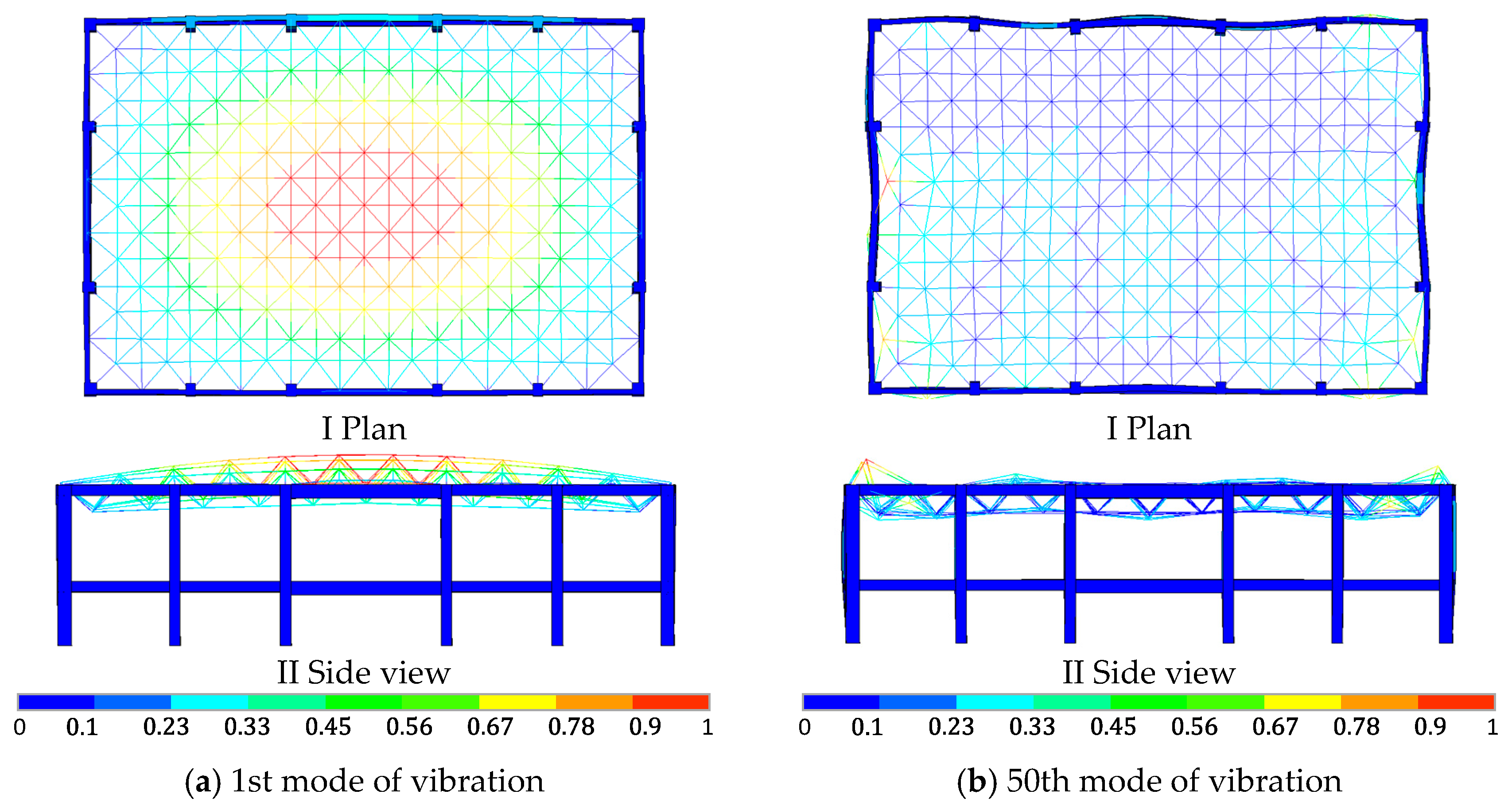

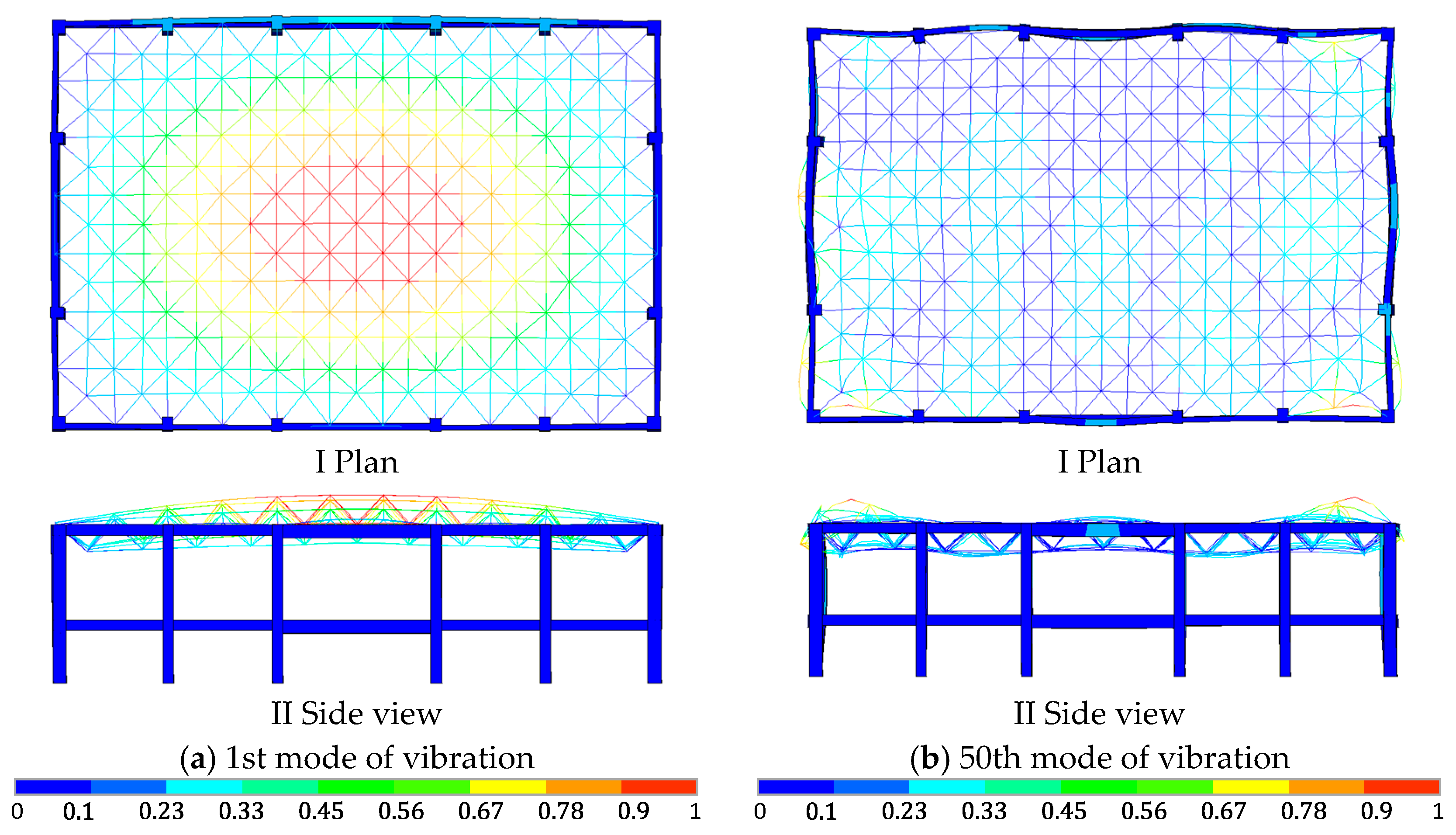

2.2.2. Modal Analysis of the Space Truss Considering the Lower Frame

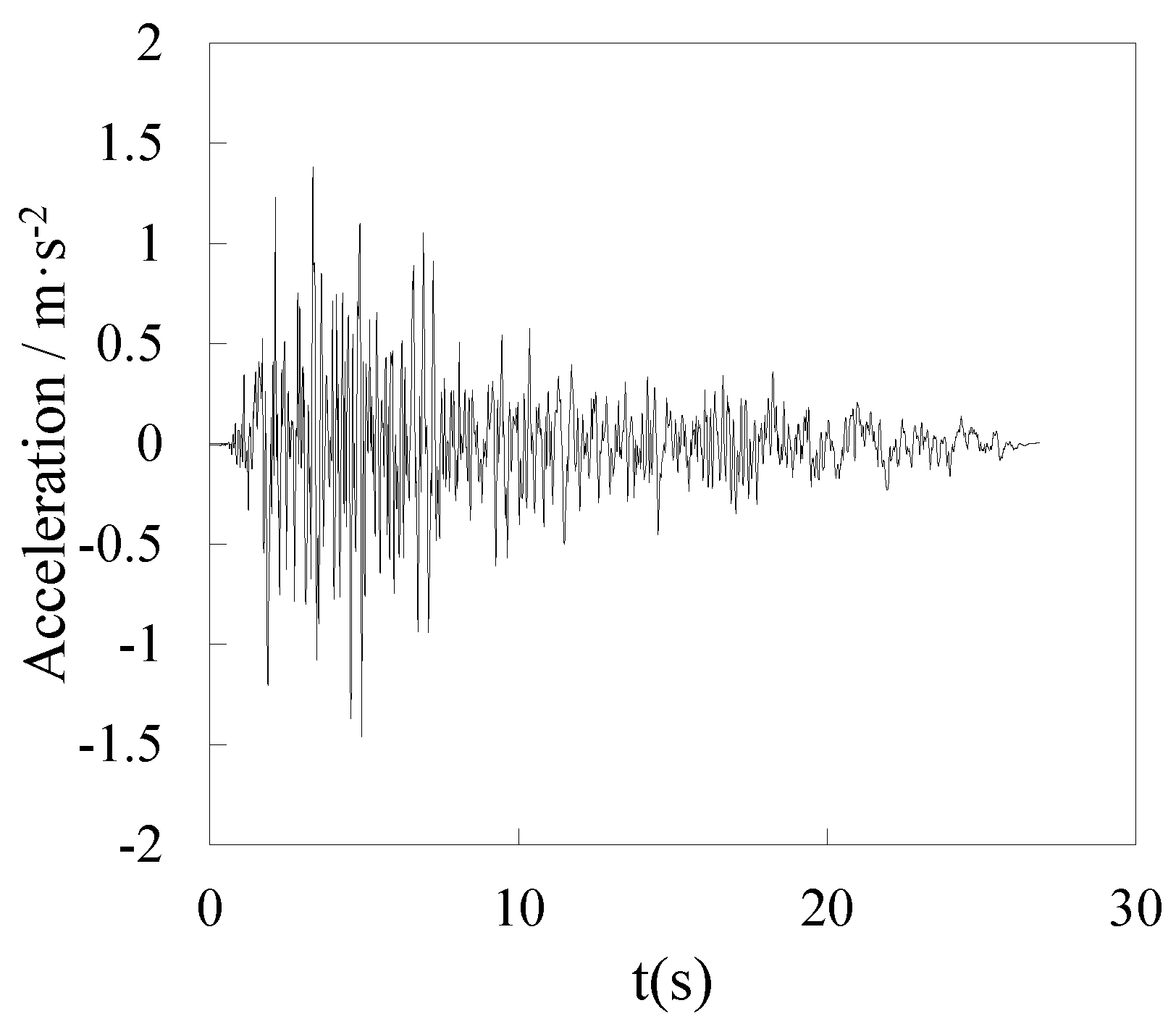

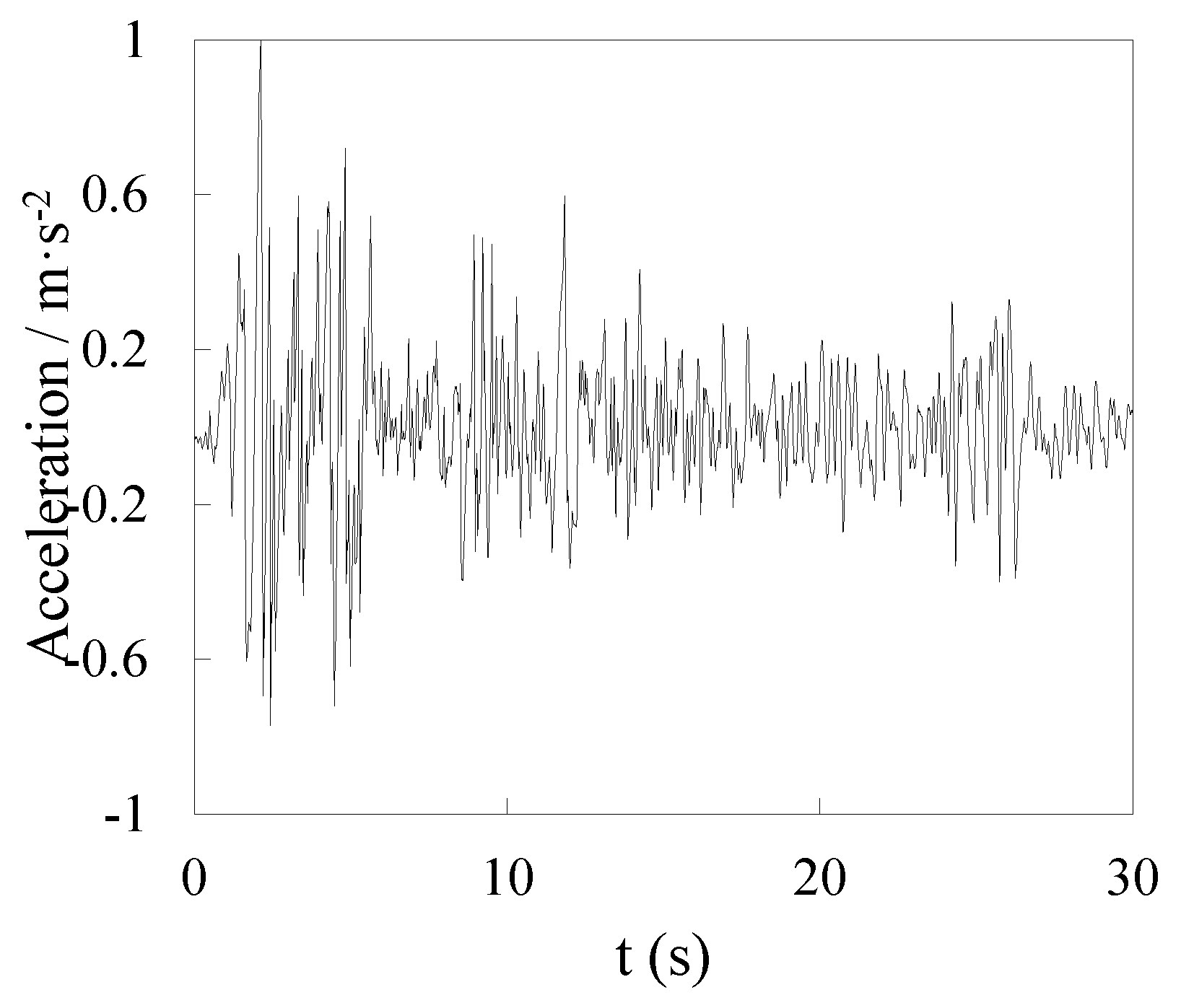

3. Dynamic Analysis of Space Trusses

3.1. Selection Indicators for Space Trusses Under Seismic Action

3.1.1. Indicators of Dynamic Instability

3.1.2. Indicators of Dynamic Strength

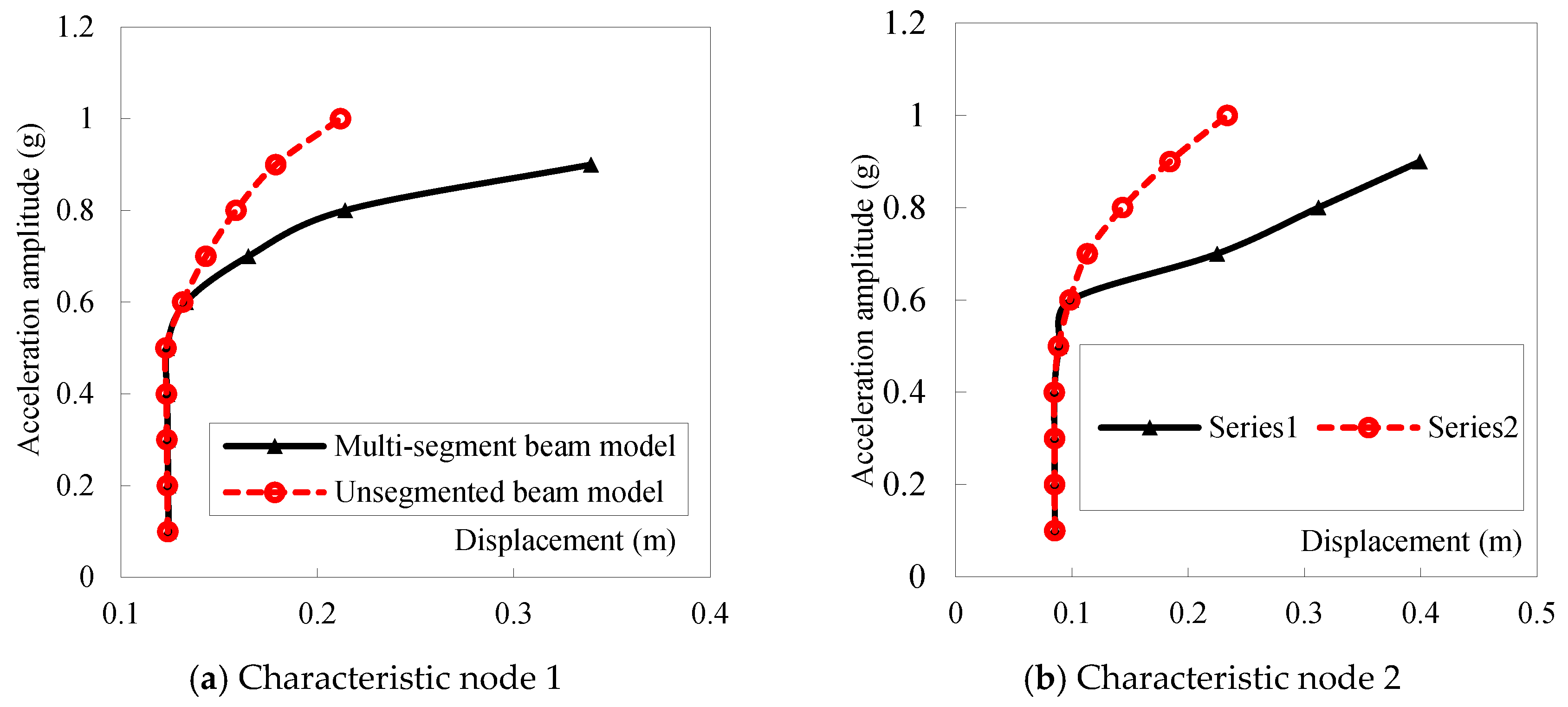

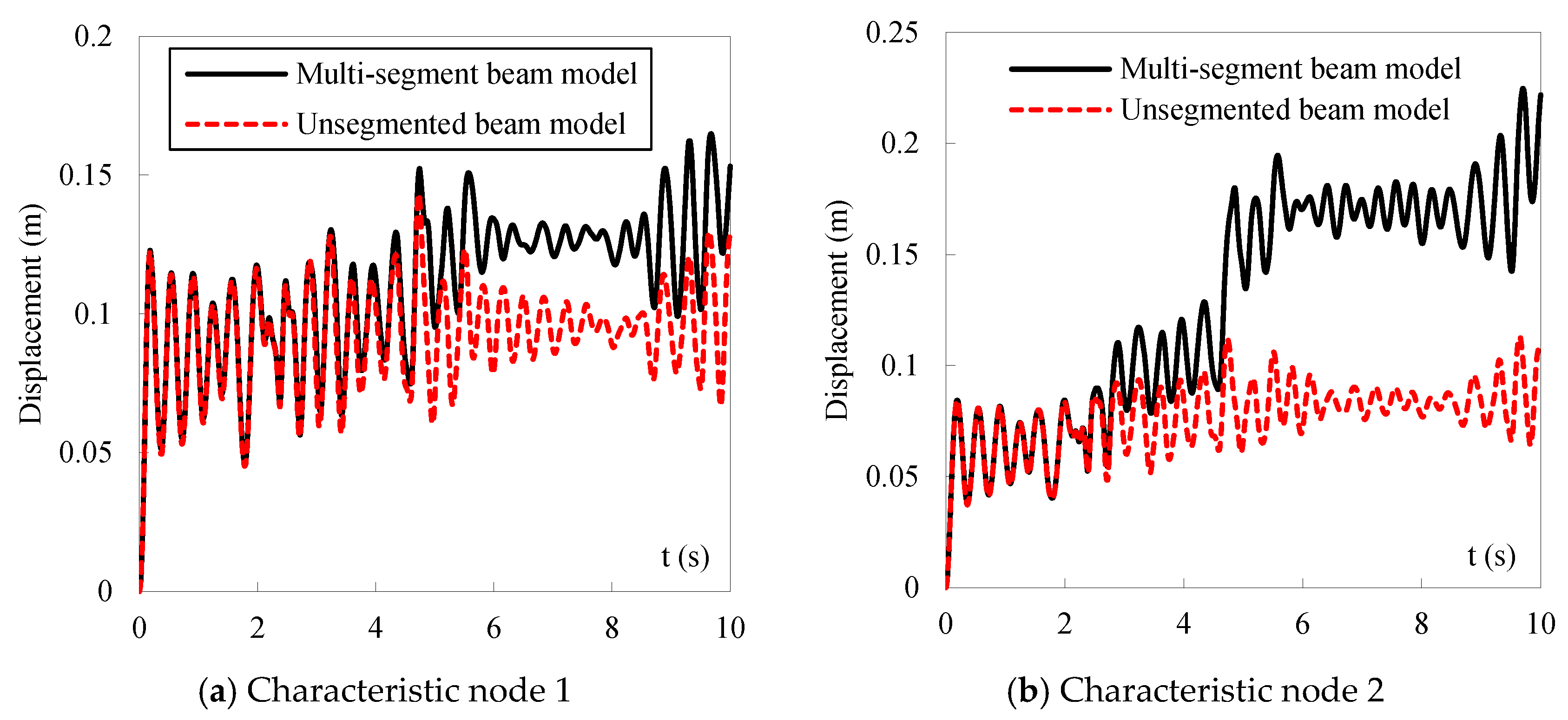

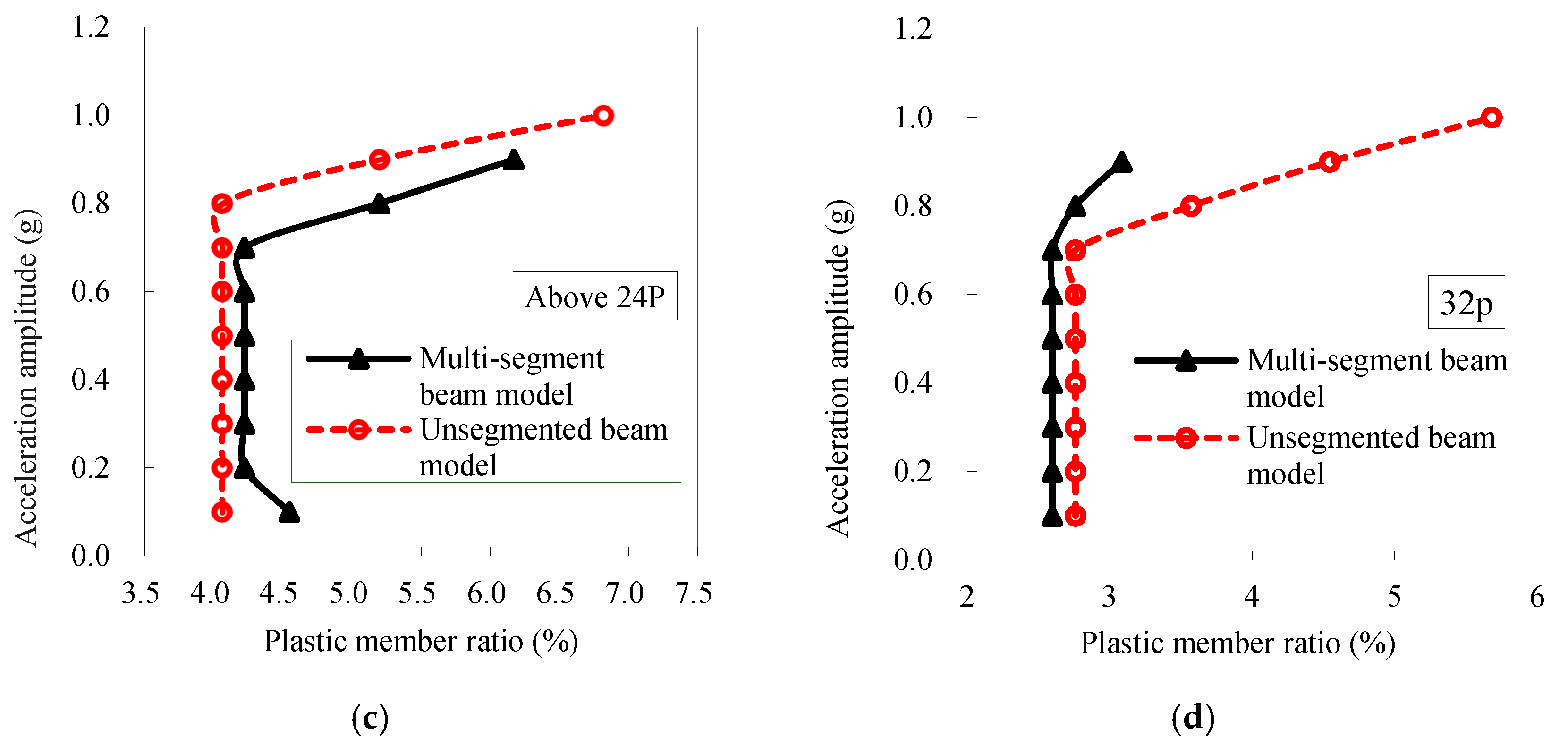

3.2. Dynamic Stability Analysis of Space Trusses

3.3. Dynamic Strength of Space Trusses

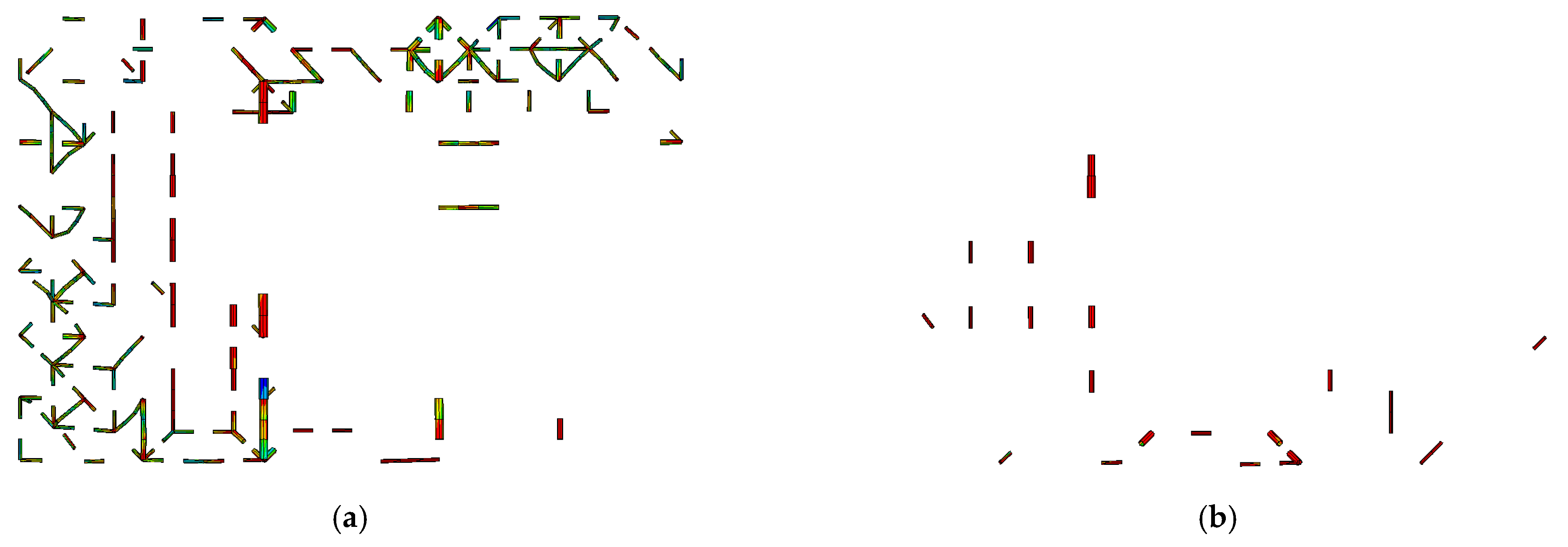

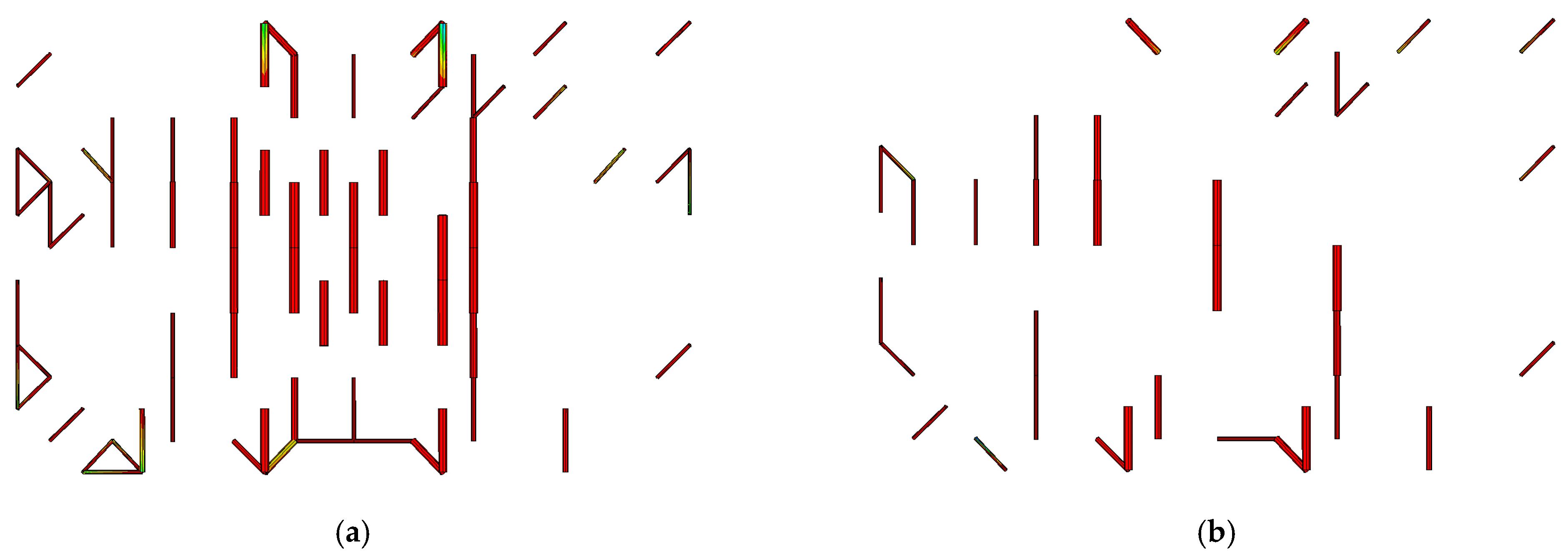

4. Failure Modes of Space Trusses Under Seismic Action

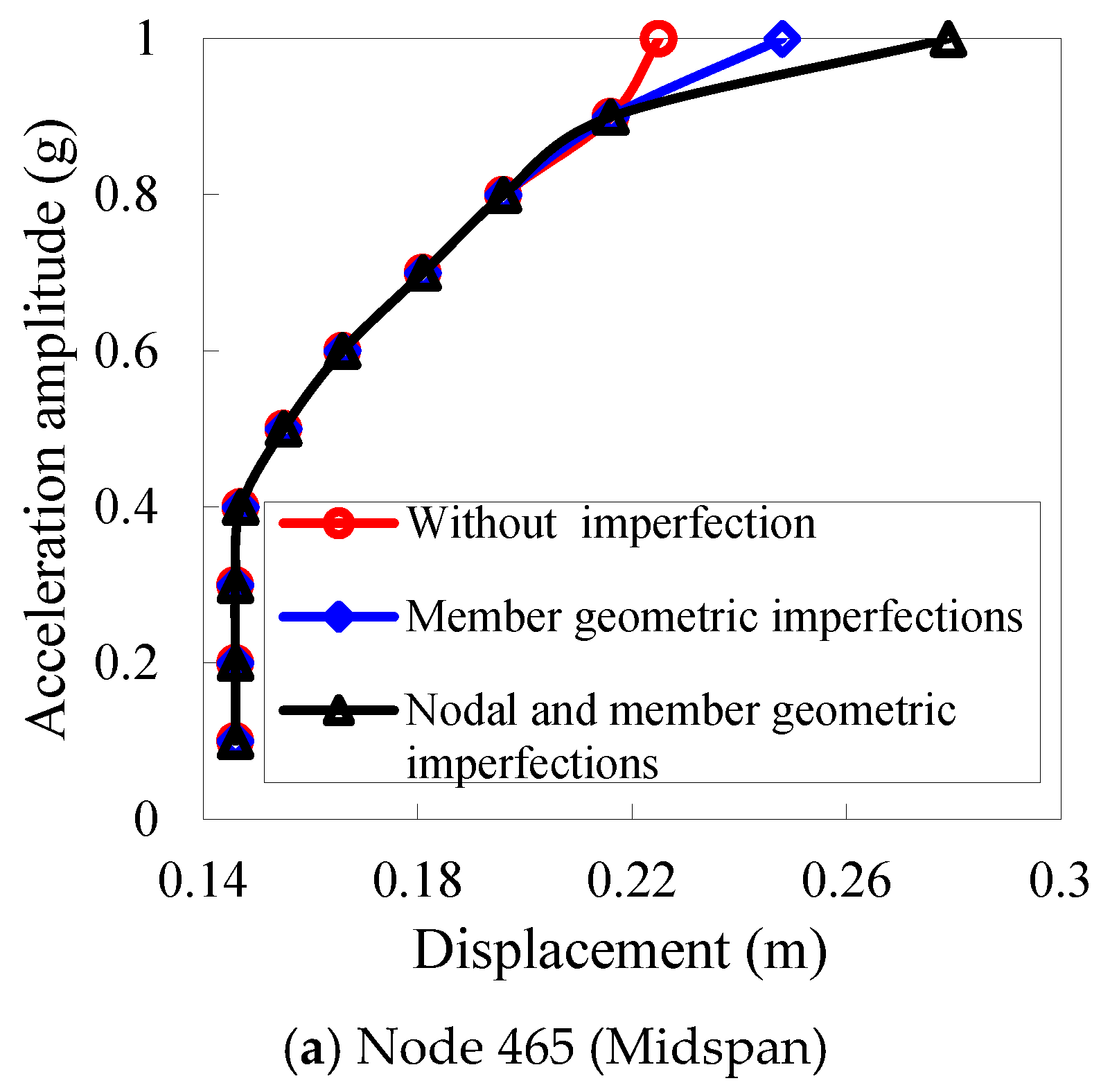

4.1. The Method for Applying Geometric Imperfections to the Space Truss

4.1.1. The Method for Applying Geometric Imperfections to the Members

4.1.2. Application Method Considering Both Nodal and Member Geometric Imperfections

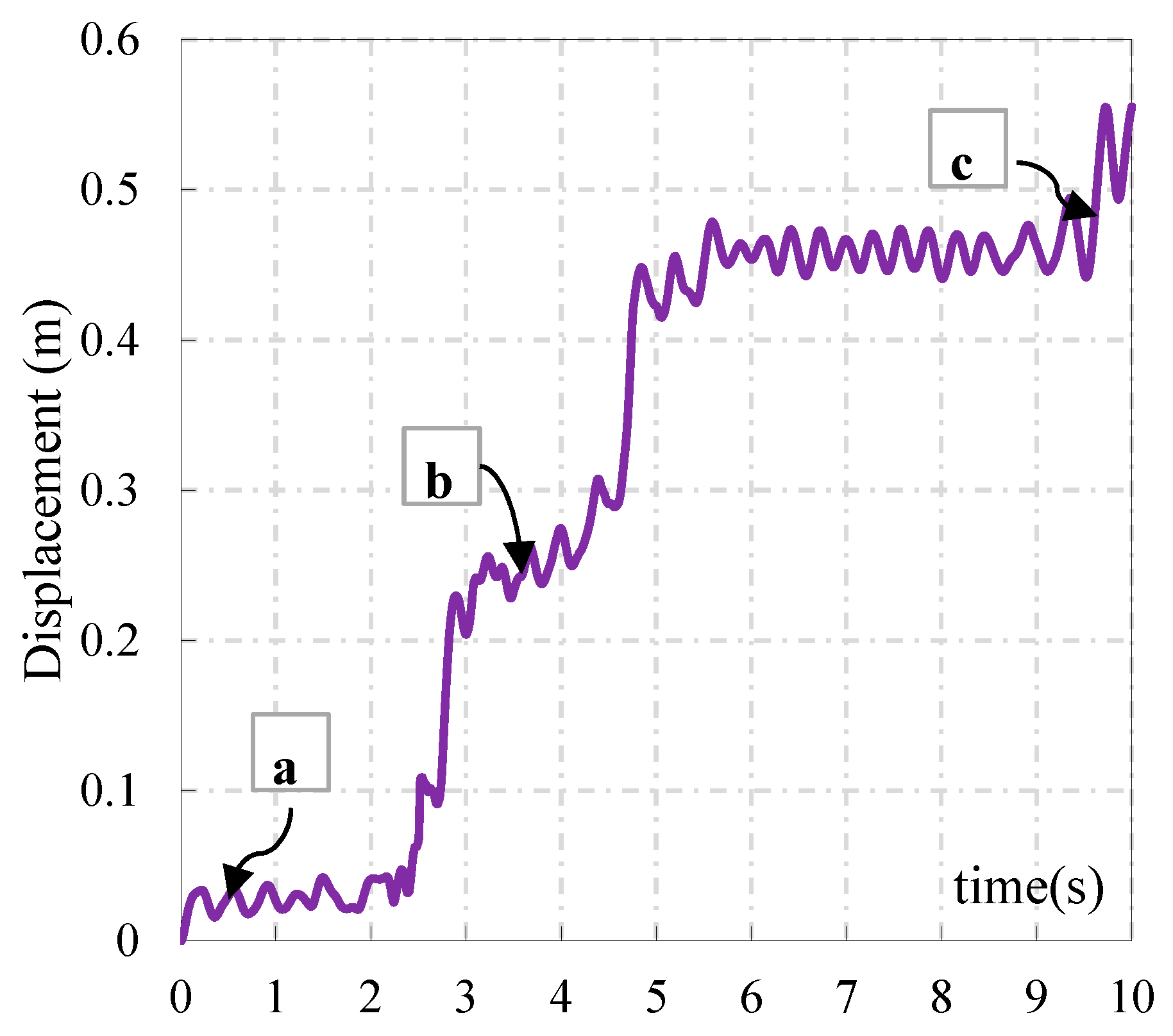

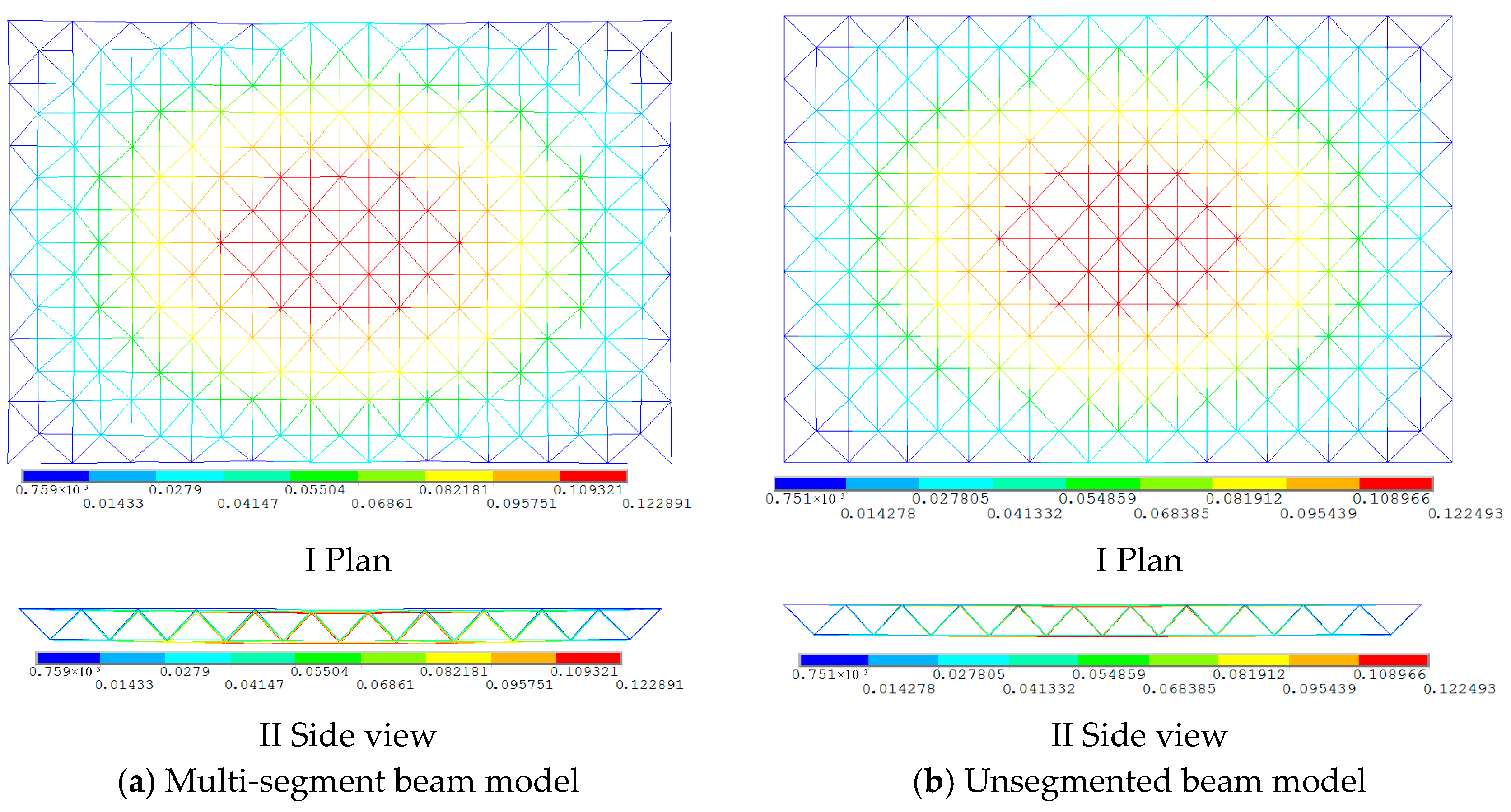

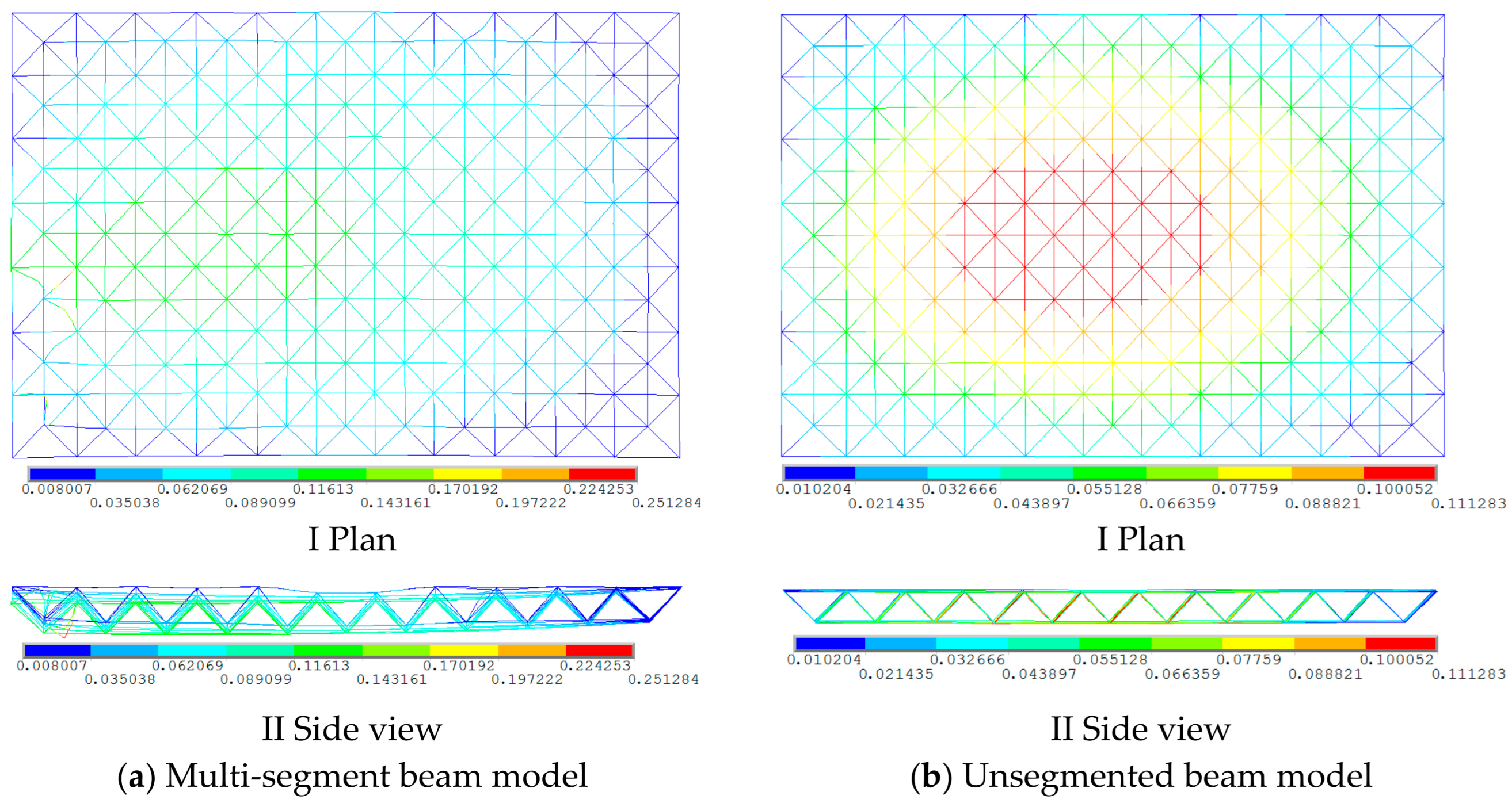

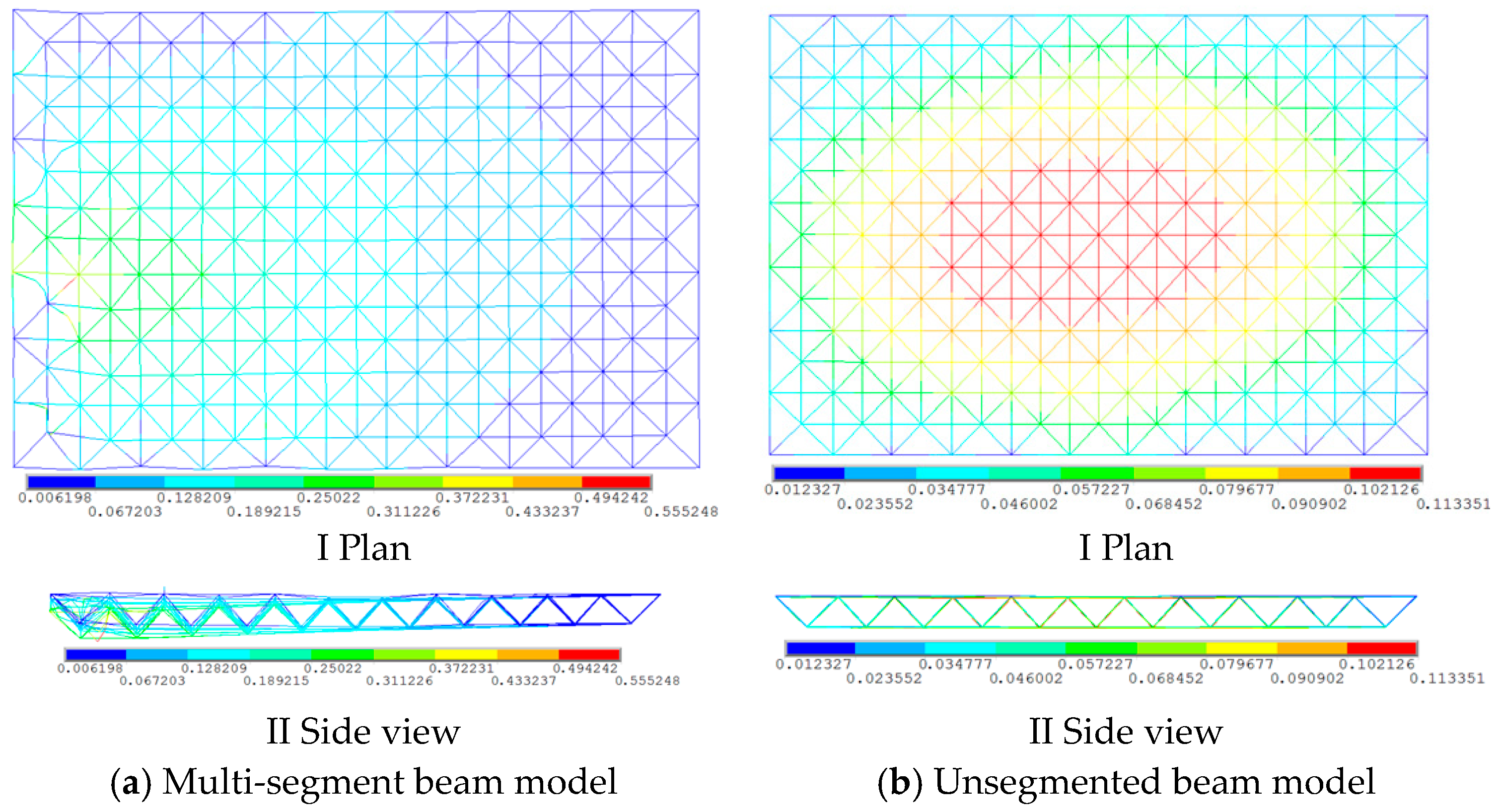

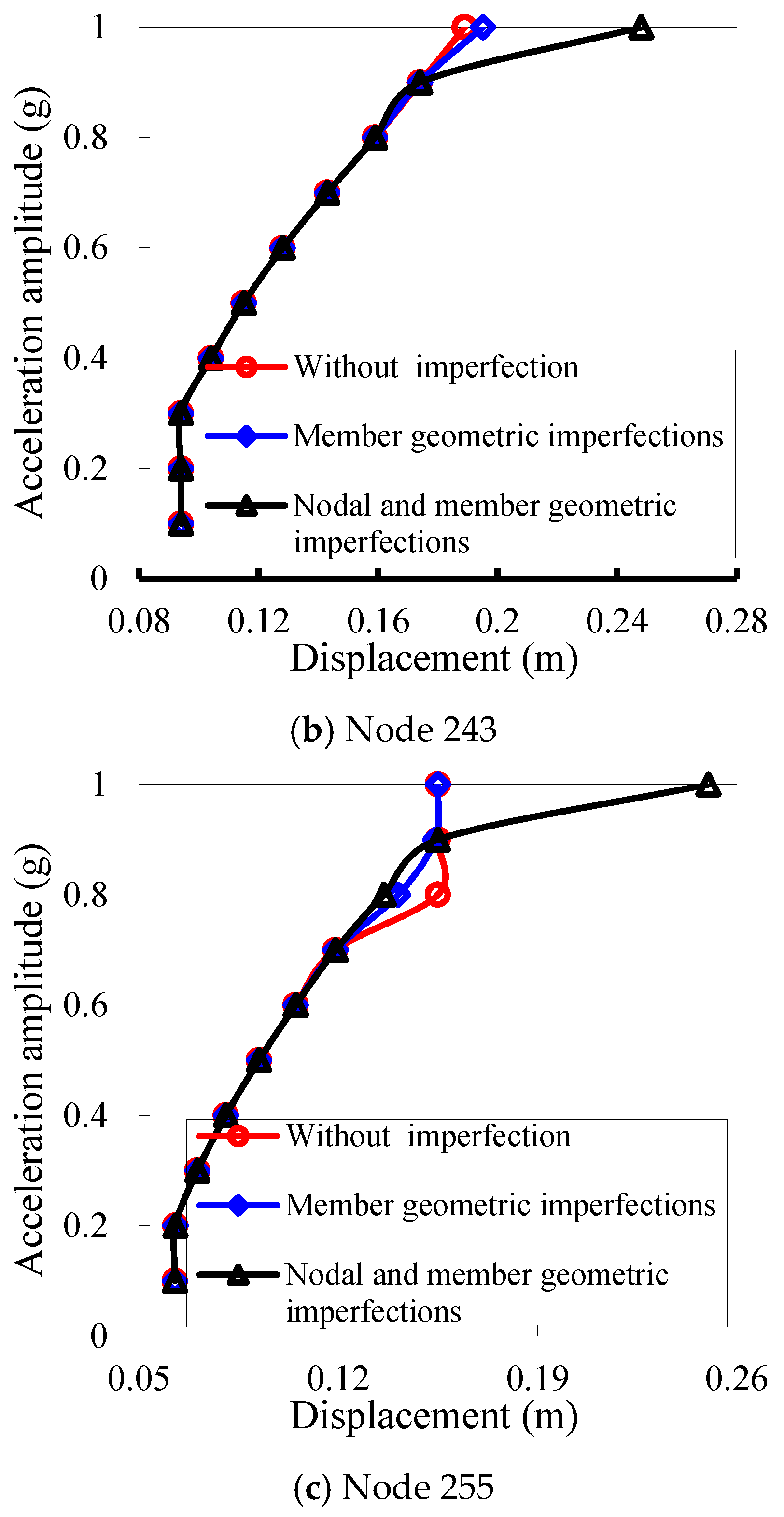

4.2. Identification of Failure Modes for Space Trusses Under Seismic Action

5. Conclusions

- In the modal analysis of the simply supported beam, the first natural frequency can be accurately captured using higher order (quadratic or cubic) shape functions even without segmentation; however, both lower and higher order vibration modes fail to adequately represent member buckling. Upon incorporating segmentation, higher order modes are simulated with greater fidelity, allowing the effects of member buckling to be properly reflected. Consequently, employing multi-segment beam models is strongly recommended for the modal analysis of simply supported beams.

- In the modal analysis of space trusses modeled with beam elements, neglecting beam segmentation precludes the consideration of member buckling. Conversely, employing multi-segment beams enables the manifestation of member buckling under higher order vibration modes. Therefore, it is advisable to adopt multi-segment beam models for the modal analysis of space trusses, as this approach yields more accurate and reliable natural frequencies and mode shapes.

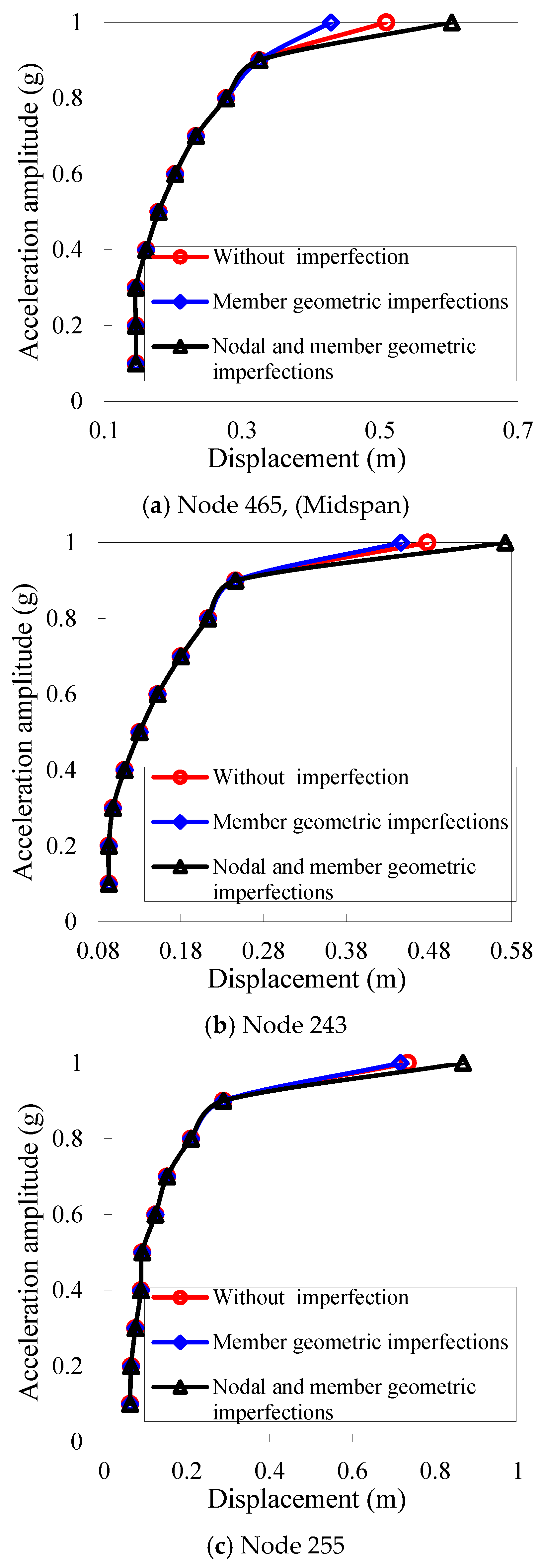

- Member buckling under intense seismic excitation cannot be captured when modeling space truss members as unsegmented beams, and consequently, no global instability is observed. This simplification leads to the erroneous conclusion that the space truss primarily fails due to loss of load carrying capacity rather than instability, thereby overestimating its true stability. In contrast, employing multi-segment beam models allows the analysis to incorporate the effects of member buckling on overall structural stability. The presence of an inflection point and bifurcation in the relationship between ground motion amplitude and nodal displacement clearly signifies that the space truss undergoes instability under strong earthquake loading, rather than mere capacity failure.

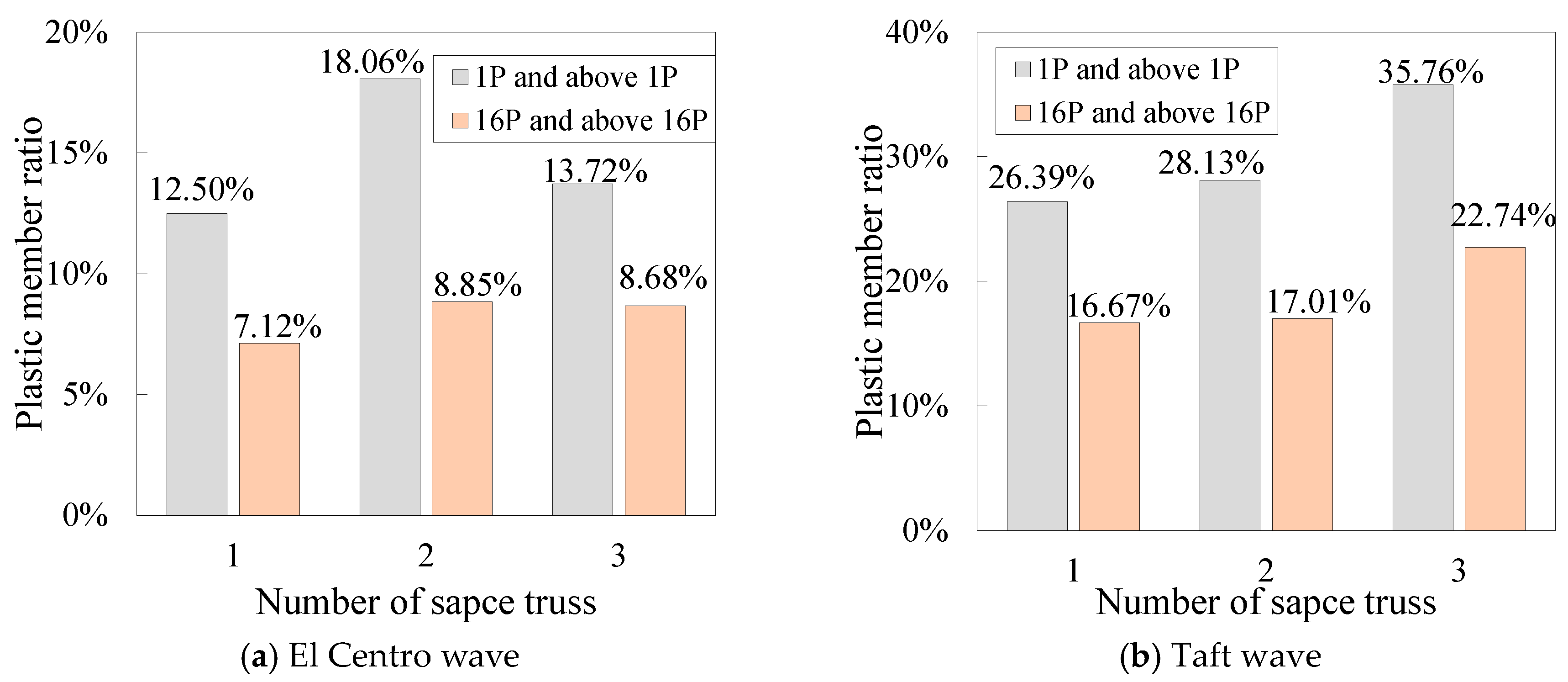

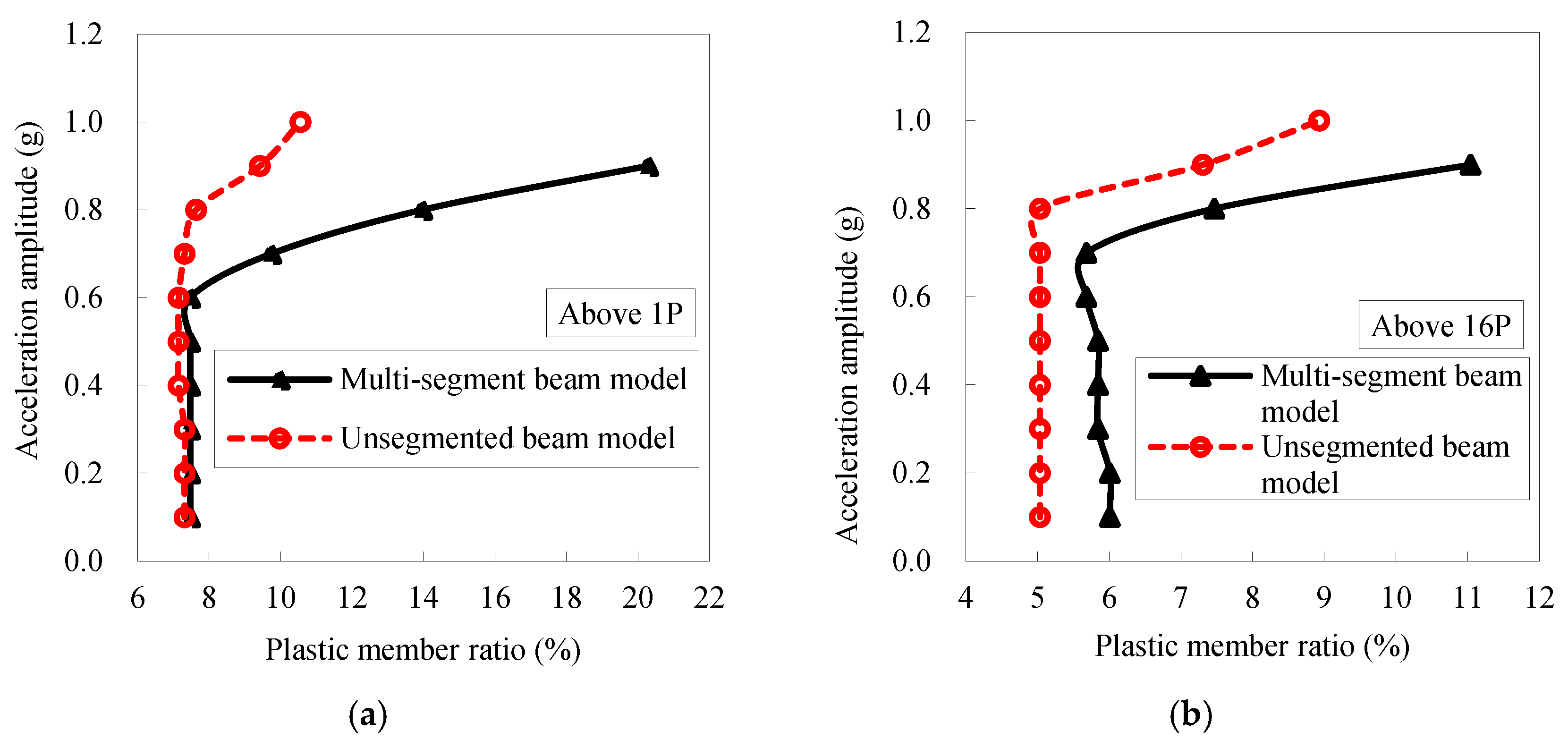

- Considering nodal and member geometric imperfections hastens the failure of a space truss. However, these imperfections do not change its fundamental failure mode under consistent seismic excitation. If an incremental dynamic analysis reveals a distinct inflection point on the acceleration–displacement curve of the truss nodes, followed by divergence in the nodal displacement time history post-jump, and if less than 20% and 10% of members have yielded at plasticity levels of 1P and above, and 16P and above respectively, the structure’s failure is deemed as dynamic stability failure. Conversely, without a distinct inflection point, with gradual divergence in mid-span displacement and significantly higher percentages of members yielding beyond the mentioned plasticity levels, the failure is classified as strength-type.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, Q. Dynamic Damage Mechanisms of Single Layer Latticed Shells under Strong Earthquakes. Ph.D. Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Zong, L.; Ding, Y.; Shi, Y. Improved physical theory model for strut members in long-span spatial structures. J. Constr. Steel. Res. 2019, 153, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Guo, X.; Li, Y. A new damage detection method of single-layer latticed shells based on combined modal strain energy index. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 172, 109011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Guo, X.; Li, Y. An updated parametric hysteretic model for steel tubular members considering compressive buckling. J. Constr. Steel. Res. 2021, 187, 106953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tian, L.; Ma, R.; Meng, X. Phenomenological hysteretic model for fixed-end steel equal-leg angle: Development and application. Thin-Walled Struct. 2023, 183, 110335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liang, Z.; Yan, J. A theoretical strut model for severe seismic analysis of single-layer reticulated domes. J. Constr. Steel. Res. 2017, 128, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, P.W.; Gates, W.E.; Anagnostopoulos, S.W. Inelastic dynamic analysis of tubular offshore structures. In Proceedings of the ninth annual offshore technology conference, Houston, TX, USA, 2–5 May 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Richard Liew, J.Y.; Punniyakotty, N.M.; Shanmugam, N.E. Advanced analysis and design of spatial structures. J. Constr. Steel. Res. 1997, 42, 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.Y.R.L. Advanced plastic hinge analysis for the design of tubular space frames. Eng. Struct. 2000, 22, 769–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Yan, J.; Cao, Z. Stability of reticulated shells considering member buckling. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2012, 77, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C. Research on the Limited Capacity of Rigid Large-Span Steel Space Structures. Ph.D. Thesis, Tongji University, Shanghai, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- So, A.K.W.; Chan, S.L. Buckling and geometrically nonlinear analysis of frames using one element/member. J. Constr. Steel Res. 1991, 20, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iu, C.K.; Bradford, M.A. Higher-order non-linear analysis of steel structures, part I: Elastic second-order formulation. Adv. Steel Constr. 2012, 8, 168–182. [Google Scholar]

- Iu, C.K.; Bradford, M.A. Higher-order non-linear analysis of steel structures, part II: Refined plastic hinge formulation. Adv. Steel Constr. 2012, 8, 183–198. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S.L.; Zhou, Z.H. Elastoplastic and large deflection analysis of steel frames by one element per member. II: Three hinges along member. J. Struct. Eng.-ASCE 2004, 130, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Yan, J.; Cao, Z. Elasto-plastic stability of single-layer reticulated domes with initial curvature of members. Thin-Walled Struct. 2012, 60, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Huang, M.; Zhang, T.; Bao, H.; Jian, B.; Xiong, G.; Zheng, Y. Global stability analysis of a cable-stiffened glulam-latticed shell. Structures 2024, 67, 106944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, G.; Wang, H.; Zhu, B. Stability analysis and design method of single-layer latticed shells with semi-rigid joints. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2025, 228, 109466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, Q.; Ma, Z.; Wang, J.; Ni, Y.; Ren, W.; Wang, H. Data interpretation and forecasting of SHM heteroscedastic measurements under typhoon conditions enabled by an enhanced Hierarchical sparse Bayesian Learning model with high robustness. Measurement 2024, 230, 114509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Ma, Z.; Ni, Y. Modelling and forecasting of SHM strain measurement for a large-scale suspension bridge during typhoon events using variational heteroscedastic Gaussian process. Eng. Struct. 2022, 251, 113554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, A.K. Dynamics of Structures: Theory and Applications to Earthquake Engineering, 3rd ed.; Prentice Hall: Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Moaveni, B.S. Finite Element Analysis Theory and Application with ANSYS, 3rd ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- GB 50010-2010; Code for Design of Concrete Structures. China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2015.

- GB 50011-2010; Code of Seismic Design of Buildings. China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Yu, Z.; Zhi, X.; Fan, F.; Lu, C. Failure mechanism of single-layer saddle-curve reticulated shells with material damage accumulation considered under severe earthquake. Int. J. Steel Struct. 2012, 12, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Zhi, X.; Fan, F.; Lu, C. Effect of substructures upon failure behavior of steel reticulated domes subjected to the severe earthquake. Thin-Walled Struct. 2011, 49, 1160–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, G.; Zhi, X.; Fan, F.; Dai, J. Seismic performance evaluation of single-layer reticulated dome and its fragility analysis. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2014, 100, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhi, X.; Fan, F. Influence of the roofing system on the seismic performance of single-layer spherical reticulated shell structures. Buildings 2022, 12, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Ning, Q.; Lu, X.; Yang, F.; Wang, Y. Shaking table tests and numerical analysis conducted on an aluminum alloy single-layer spherical reticulated shell with fully welded connections. Buildings 2024, 14, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, F.; Chen, S.; Yang, F.; Fang, X.; Zhao, W. Determination method of failure mode of grid structures under earthquake actions. Earthq. Resist. Eng. Retrofit. 2024, 46, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.; Zhi, X. Failure mechanism of reticular shells subjected to dynamic actions. China Civil. Eng. J. 2005, 38, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, B. Research on the Collapse Mechanism of Spatial Trusses. Master’s Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Wu, H.; Gao, B. Failure modes and their numerical descriptions of grid structures subjected to earthquake. J. Vib. Shock. 2011, 30, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- JGJ-2010; Technical Specification for Spatial Grid Structure. China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2010.

- Bagheri, M.; Malidarreh, N.R.; Ghaseminejad, V.; Asgari, A. Seismic resilience assessment of RC superstructures on long–short combined piled raft foundations: 3D SSI modeling with pounding effects. Structures 2025, 81, 110176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeim, B.; Javadzade Khiavi, A.; Khajavi, E.; Taghavi Khanghah, A.R.; Asgari, A.; Taghipour, R.; Bagheri, M. Machine learning approaches for fatigue life prediction of steel and feature importance analyses. Infrastructures 2025, 11, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Elastic modulus | Pa |

| Length | |

| Sectional area | |

| Inertial moment of beam | |

| First order circular frequency | |

| First order natural vibration frequency |

| Number of Beam Element Segments | Linear Shape Function | Quadratic Shape Function | Cubic Shape Function | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | |

| 1 | 475.26 | 950.53 | 1664.70 | 20.01 | 379.32 | 432.63 | 18.27 | 91.12 | 431.05 |

| 2 | 24.04 | 75.94 | 442.16 | 18.24 | 79.65 | 156.07 | 18.04 | 72.78 | 173.85 |

| 3 | 20.43 | 120.17 | 223.74 | 18.07 | 74.26 | 177.82 | 18.03 | 71.91 | 162.65 |

| 5 | 18.85 | 86.04 | 242.25 | 18.04 | 72.18 | 164.17 | 18.03 | 71.84 | 160.65 |

| 10 | 18.23 | 75.07 | 177.34 | 18.03 | 71.86 | 160.81 | 18.03 | 71.83 | 160.56 |

| 20 | 18.08 | 72.63 | 164.55 | 18.03 | 71.84 | 160.58 | 18.03 | 71.83 | 160.56 |

| 50 | 18.04 | 71.96 | 161.19 | 18.03 | 71.83 | 160.56 | 18.03 | 71.83 | 160.56 |

| Theoretical solution | 18.06 | 72.24 | 162.54 | 18.06 | 72.24 | 162.54 | 18.06 | 72.24 | 162.54 |

| Number of Beam Element Segments | Linear Shape Function | Quadratic Shape Function | Cubic Shape Function | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | |

| 1 | 2531.6 | 1215.8 | 924.2 | 10.8 | 425.1 | 166.2 | 1.2 | 26.1 | 165.2 |

| 2 | 33.1 | 5.1 | 172.1 | 1.0 | 10.3 | −4.0 | −0.1 | 0.7 | 7.0 |

| 3 | 13.1 | 66.3 | 37.7 | 0.1 | 2.8 | 9.4 | −0.2 | −0.5 | 0.1 |

| 5 | 4.4 | 19.1 | 49.1 | −0.1 | −0.1 | 1.0 | −0.2 | −0.6 | −1.2 |

| 10 | 0.9 | 3.9 | 9.1 | −0.2 | −0.5 | −1.1 | −0.2 | −0.6 | −1.2 |

| 20 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1.3 | −0.2 | −0.6 | −1.2 | −0.2 | −0.6 | −1.2 |

| 50 | −0.1 | −0.4 | −0.8 | −0.2 | −0.6 | −1.2 | −0.2 | −0.6 | −1.2 |

| Type | Number | Section Specifications (mm × mm) | Type | Section Dimension (mm × mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circular steel tube | 1 | Column | a × b = 750 × 750 (corner column) a × b = 600 × 750 (intermediate column) | |

| 2 | ||||

| 3 | ||||

| 4 | Beam | b × h = 300 × 600 b × h = 400 × 750 | ||

| 5 | ||||

| 6 |

| Number of Beam Element Segments | Linear Shape Function | Quadratic Shape Function | Cubic Shape Function | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 10th | 1st | 10th | 1st | 10th | |

| 1 | 9.64 | 39.82 | 9.50 | 27.09 | 9.41 | 22.59 |

| 3 | 9.46 | 25.55 | 9.42 | 22.13 | 9.41 | 22.04 |

| 5 | 9.43 | 23.34 | 9.41 | 22.05 | 9.41 | 22.03 |

| 10 | 9.42 | 22.35 | 9.41 | 22.04 | 9.41 | 22.03 |

| 20 | 9.41 | 22.11 | 9.41 | 22.03 | 9.41 | 22.03 |

| 50 | 9.41 | 22.05 | 9.41 | 22.03 | 9.41 | 22.03 |

| Number of Beam Element Segments | Linear Shape Function | Quadratic Shape Function | Cubic Shape Function | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 50th | 1st | 50th | 1st | 50th | |

| 1 | 2.82 | 16.51 | 2.81 | 16.41 | 2.81 | 16.36 |

| 3 | 2.81 | 16.40 | 2.81 | 16.36 | 2.81 | 16.36 |

| 5 | 2.81 | 16.37 | 2.81 | 16.36 | 2.81 | 16.36 |

| 10 | 2.82 | 16.41 | 2.82 | 16.41 | 2.82 | 16.41 |

| 20 | 2.83 | 16.44 | 2.83 | 16.44 | 2.83 | 16.44 |

| 50 | 2.83 | 16.44 | 2.83 | 16.44 | 2.83 | 16.44 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fang, X.; Bao, X.; Wang, S. A Multi-Segment Beam Approach for Capturing Member Buckling in Seismic Stability Analysis of Space Truss Structures. Buildings 2025, 15, 4447. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244447

Fang X, Bao X, Wang S. A Multi-Segment Beam Approach for Capturing Member Buckling in Seismic Stability Analysis of Space Truss Structures. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4447. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244447

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Xibing, Xin Bao, and Shiwei Wang. 2025. "A Multi-Segment Beam Approach for Capturing Member Buckling in Seismic Stability Analysis of Space Truss Structures" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4447. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244447

APA StyleFang, X., Bao, X., & Wang, S. (2025). A Multi-Segment Beam Approach for Capturing Member Buckling in Seismic Stability Analysis of Space Truss Structures. Buildings, 15(24), 4447. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244447