Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Post-Weld Heat Treatment on Residual Stress Relaxation in Orthotropic Steel Decks Welding

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory of TEP-FEM and Creep

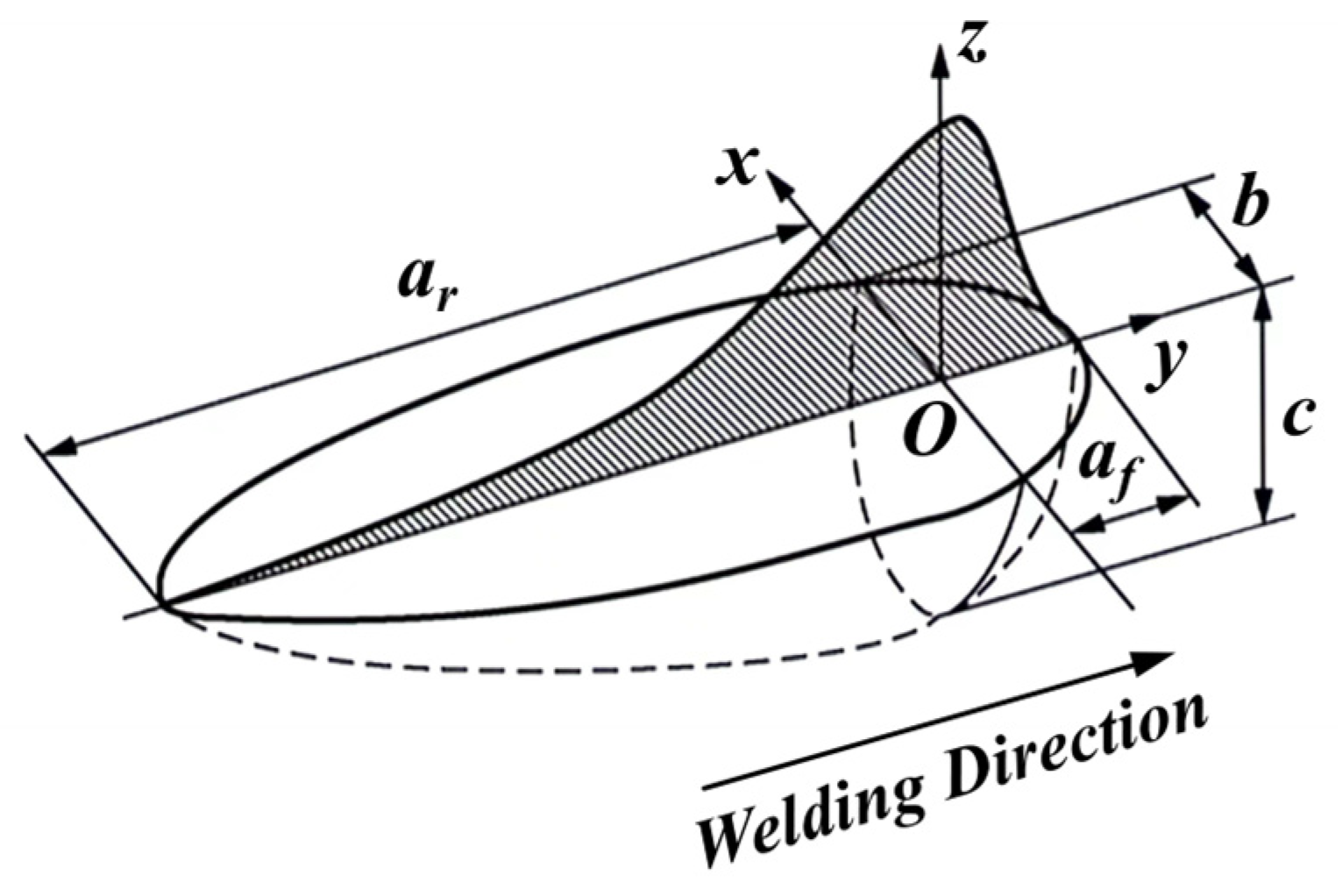

2.1. Welding Heat Transfer and Heat Resource Theory

2.2. Elastic-Plastic Mechanics Theory

2.3. Creep Theory

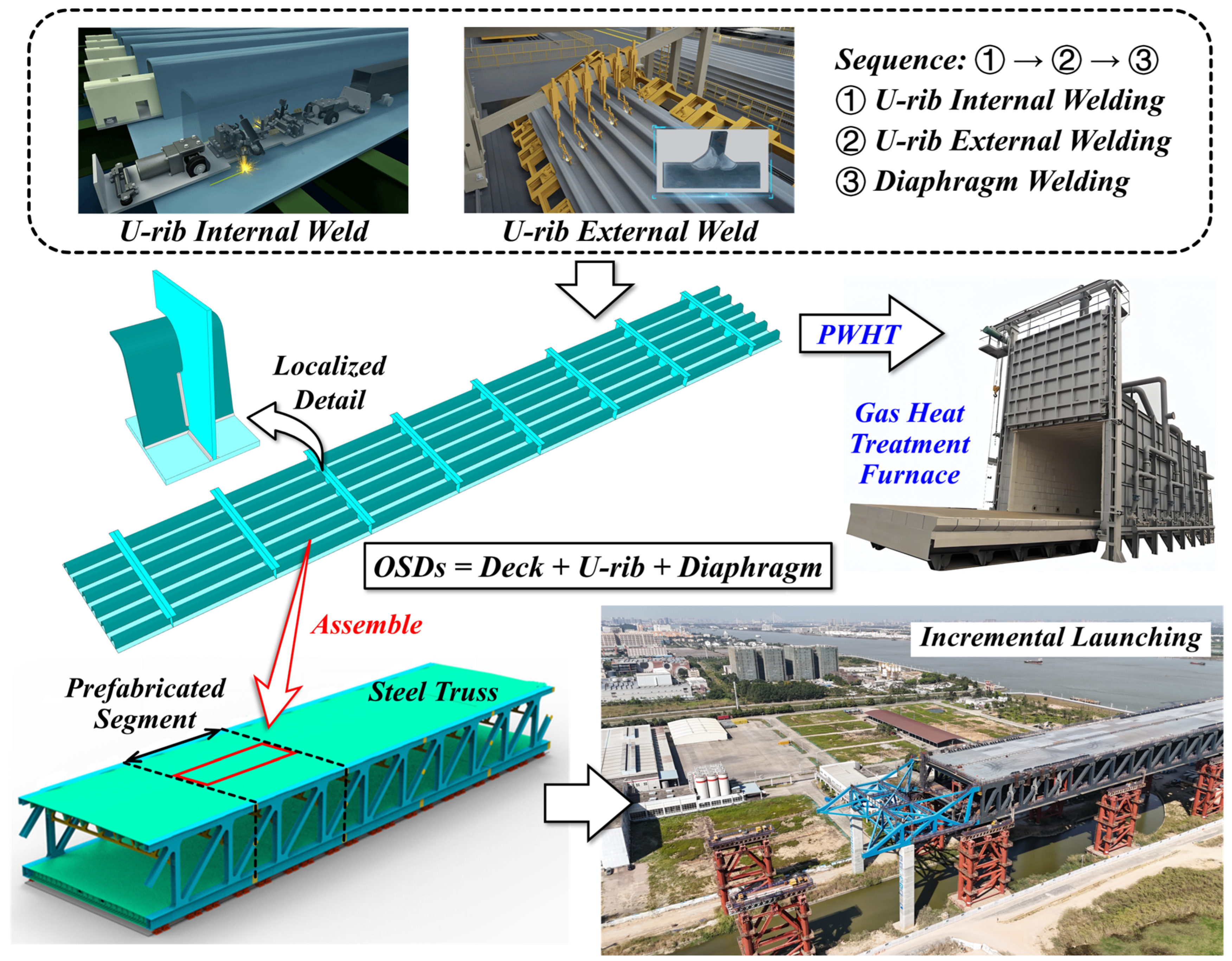

3. Numerical Simulation Detail and Experimental Procedure

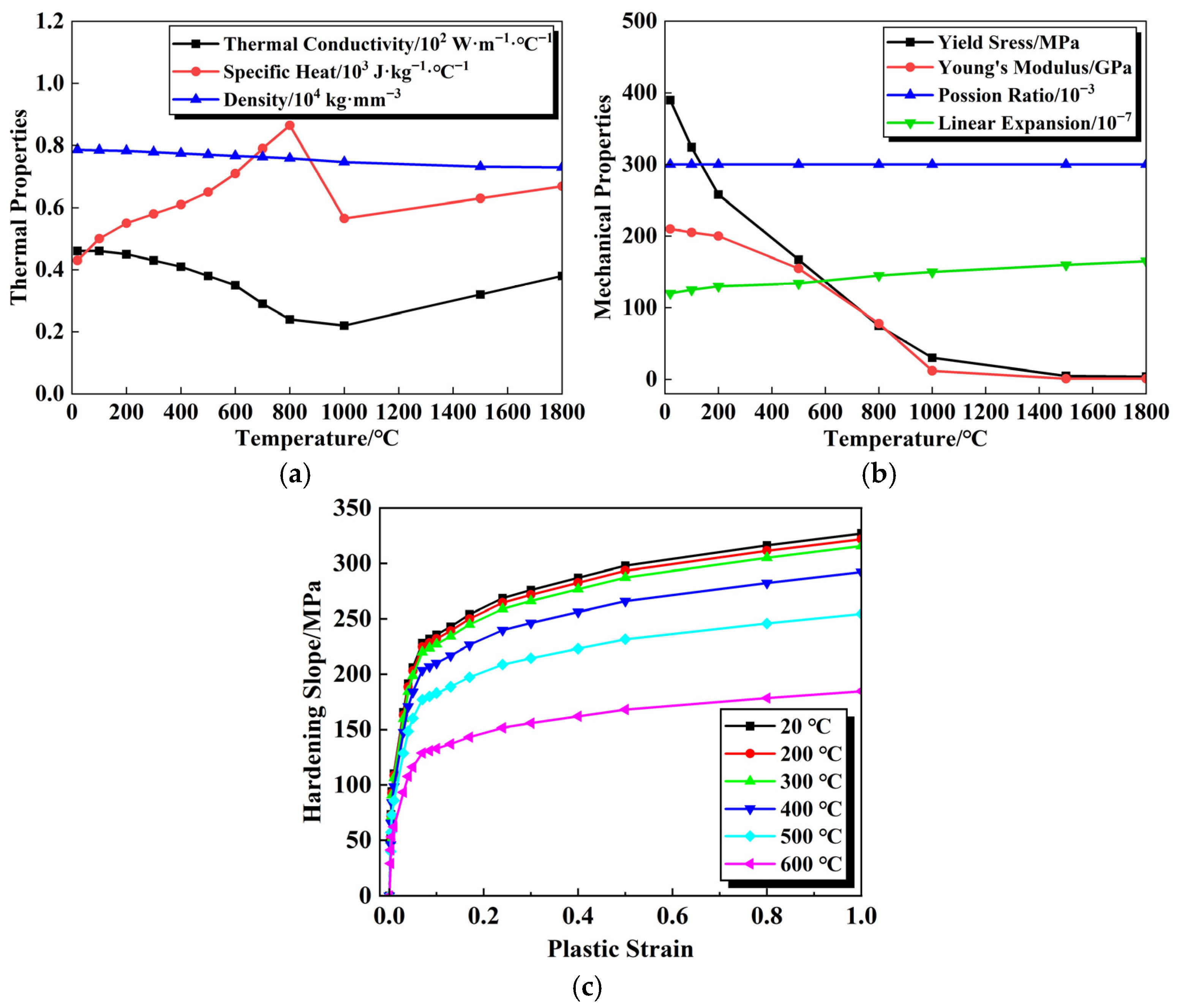

3.1. Properties of Materials

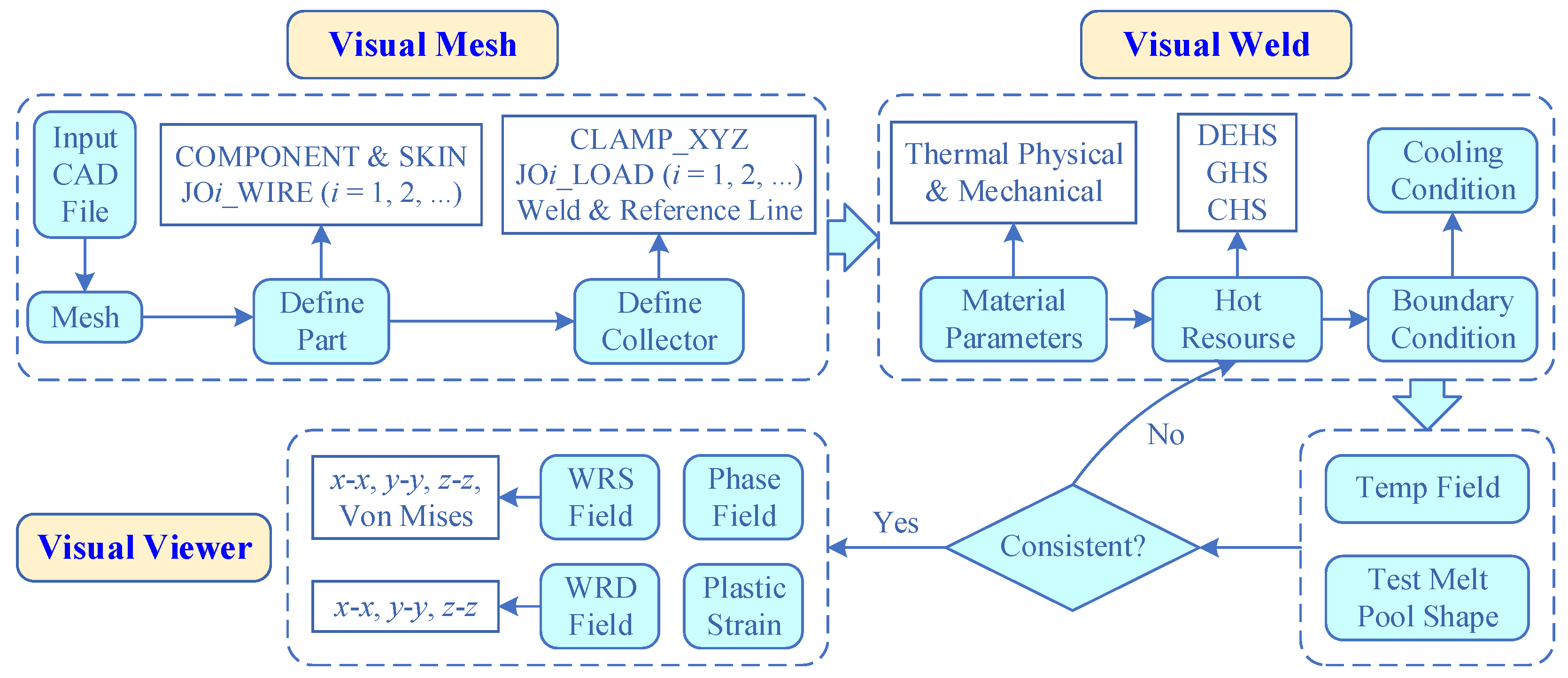

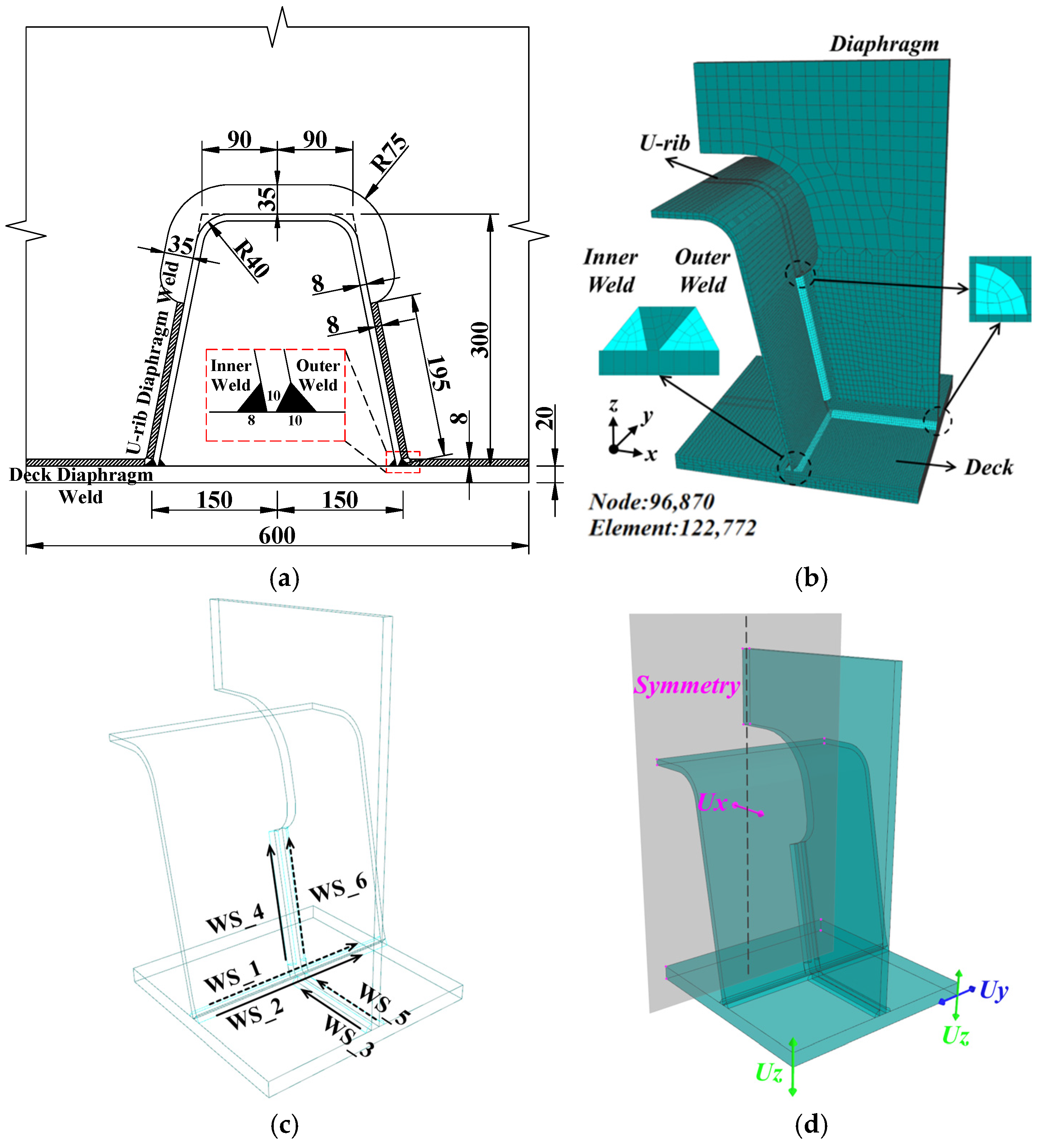

3.2. Finite Element Modeling

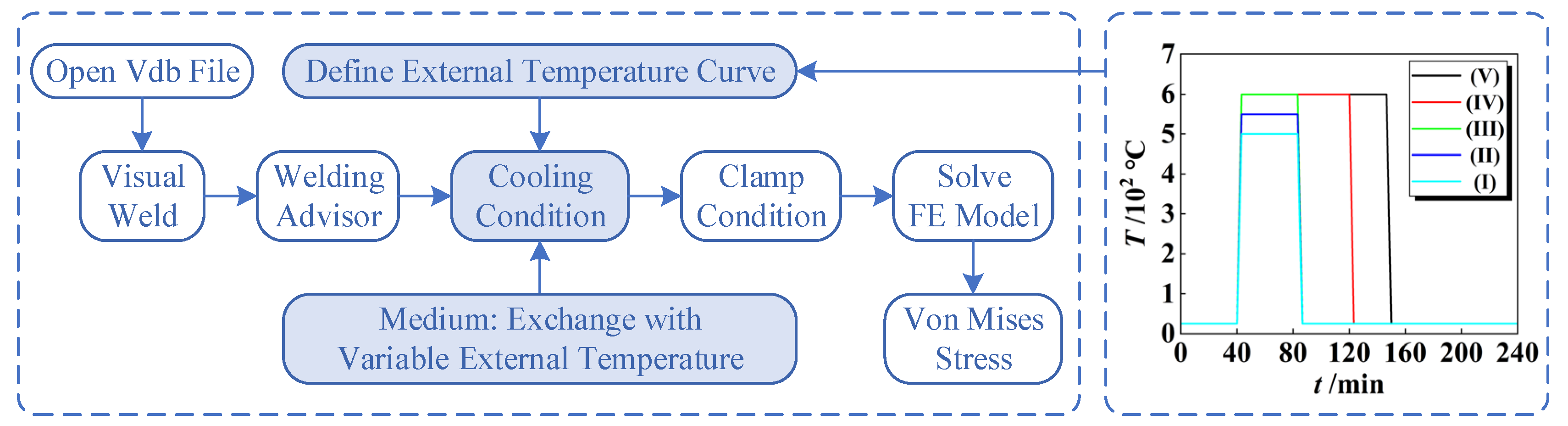

3.3. PWHT Program

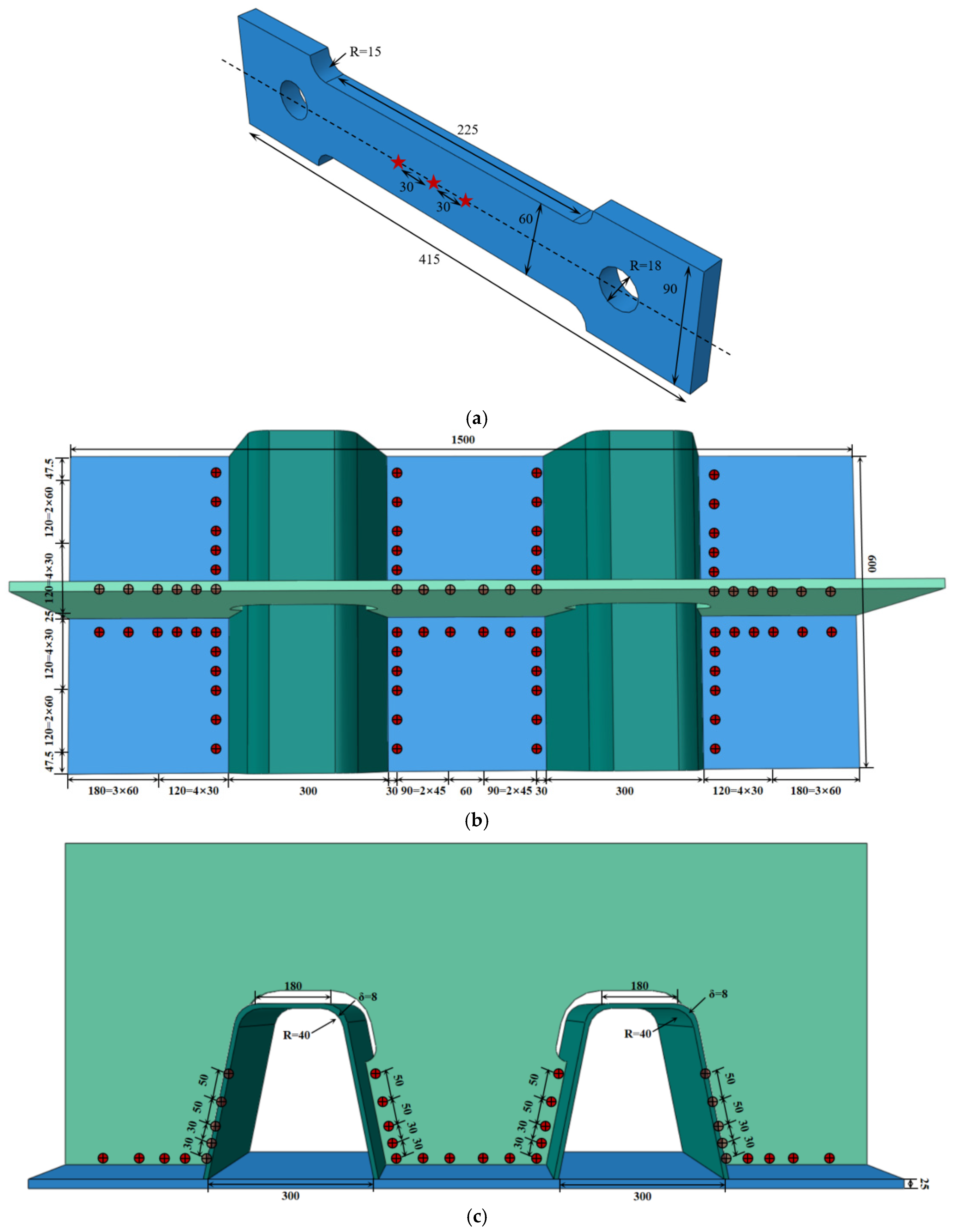

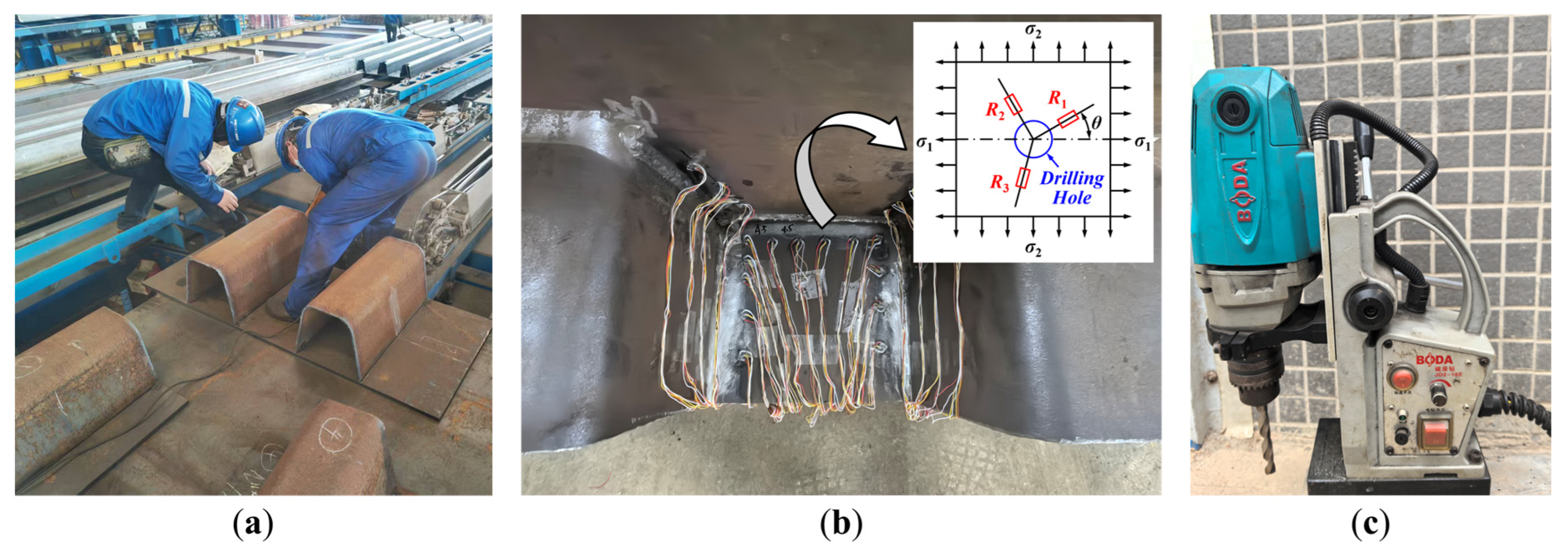

3.4. Experiment

4. Temperature, WRS, and PWHT Analysis

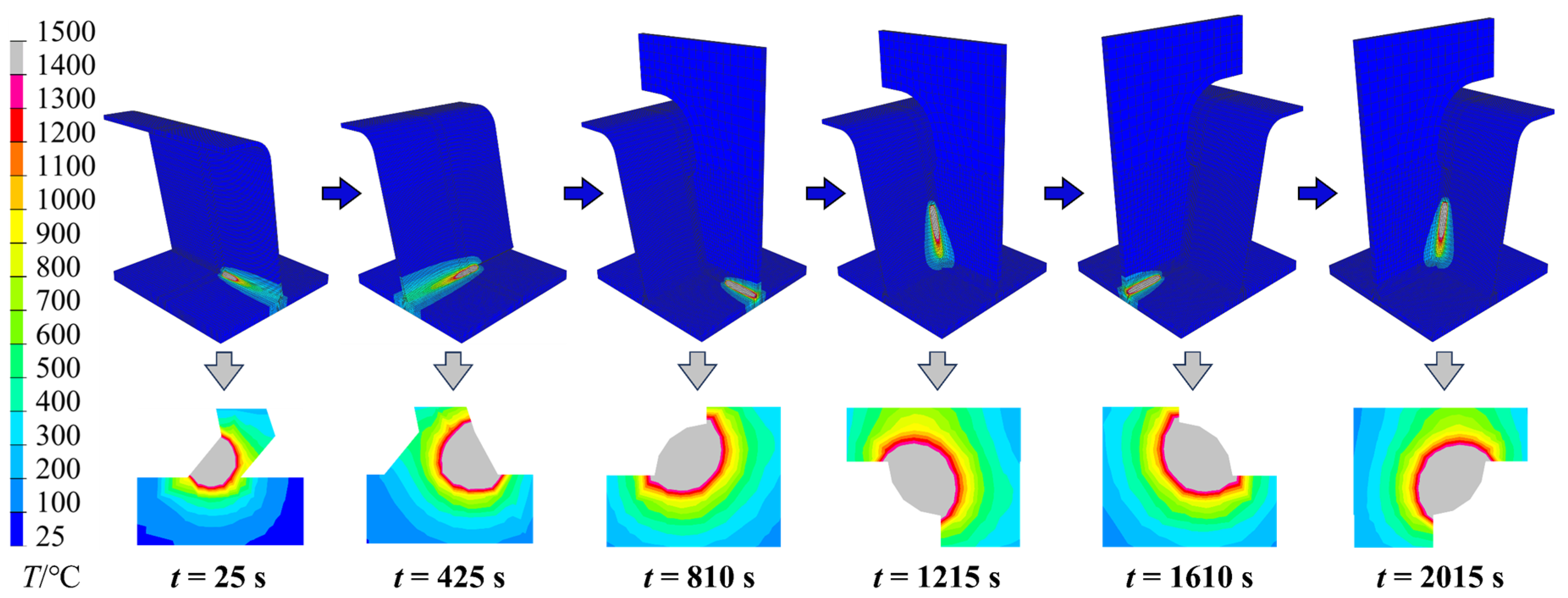

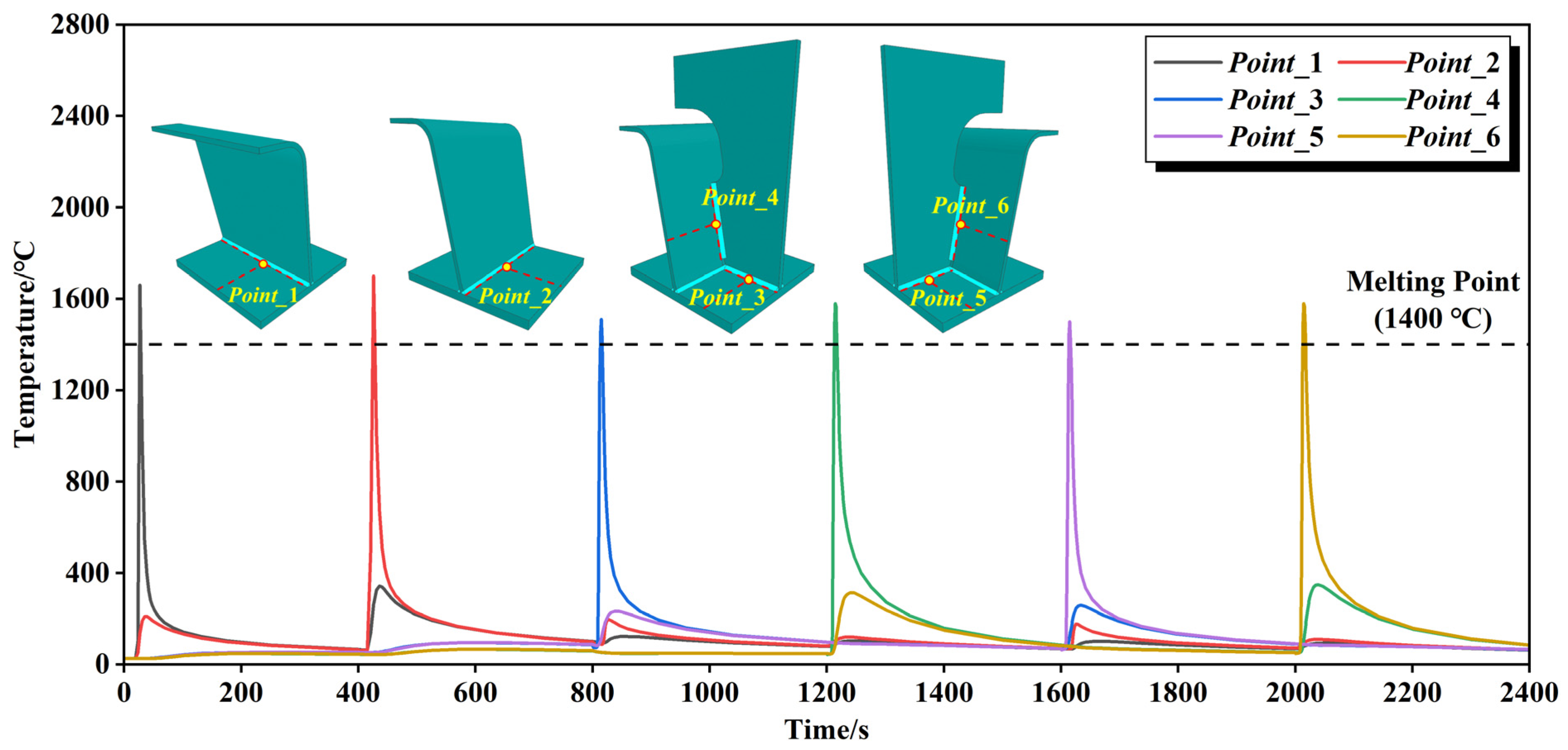

4.1. Temperature Field

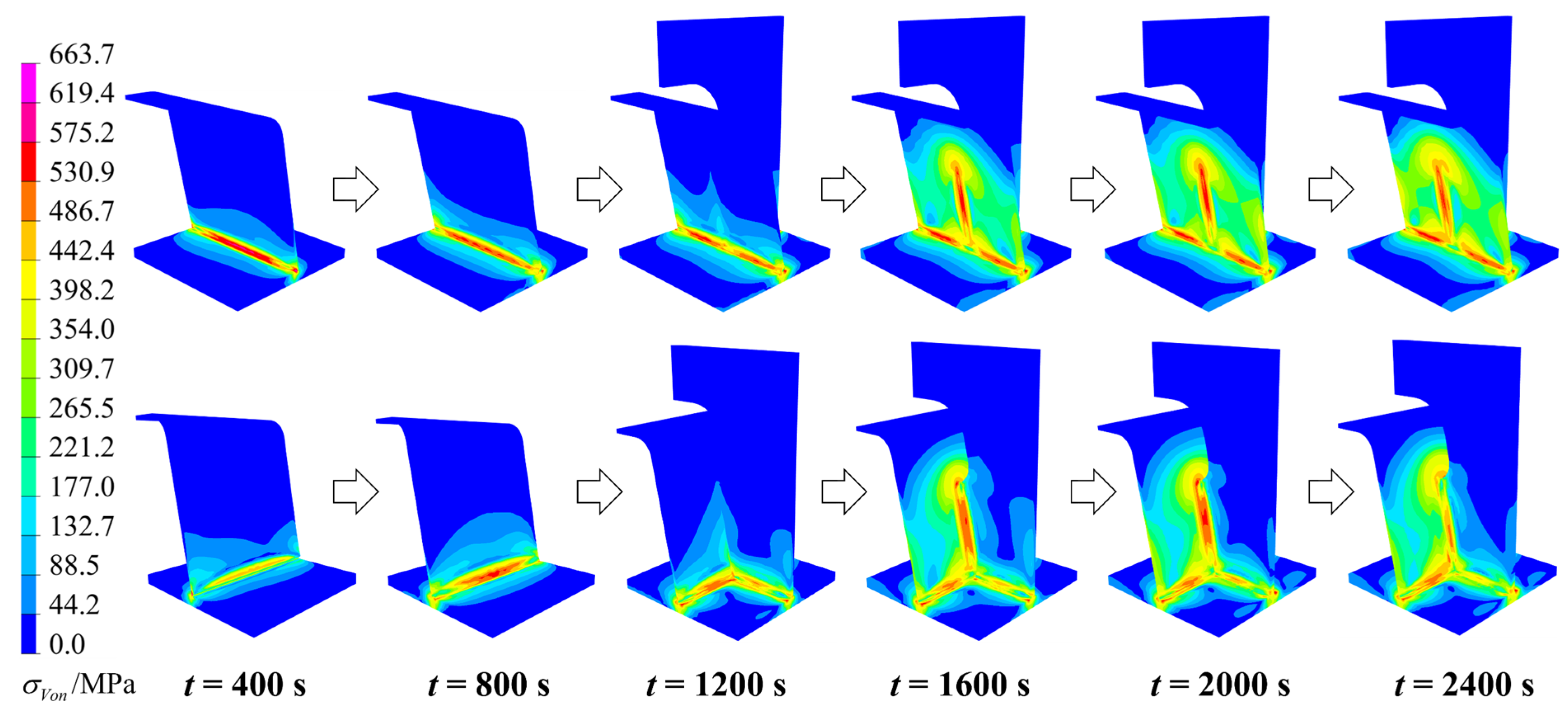

4.2. WRS Field

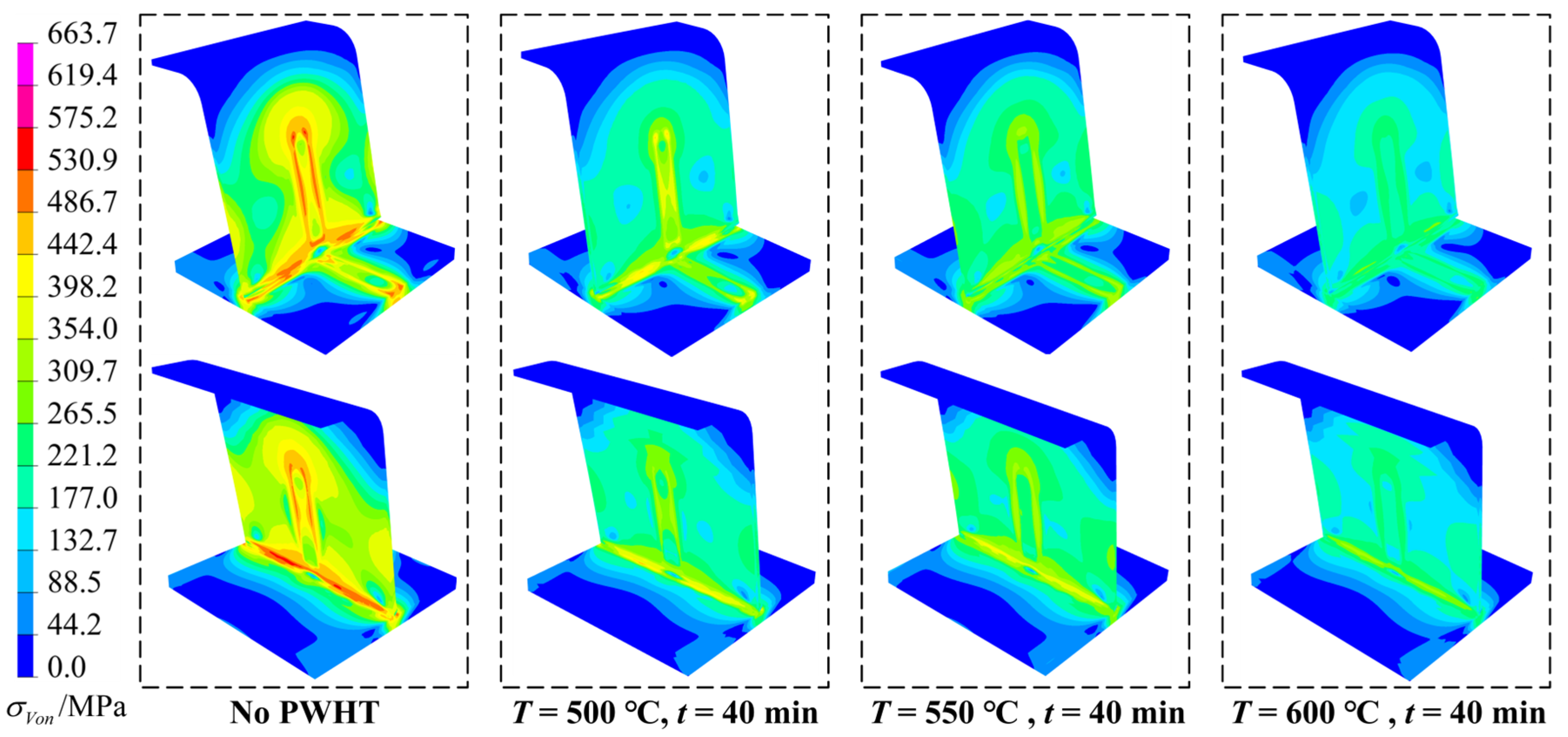

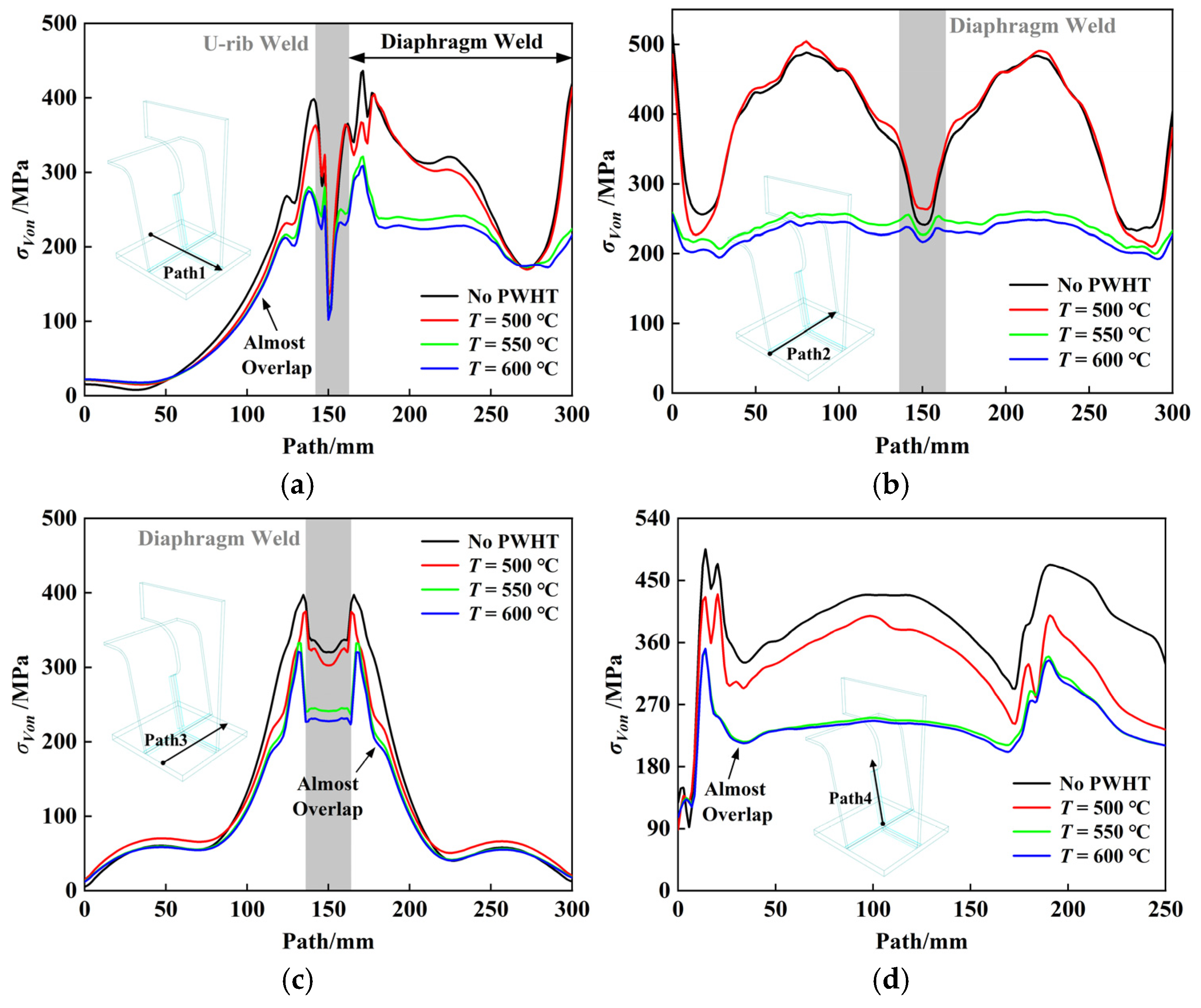

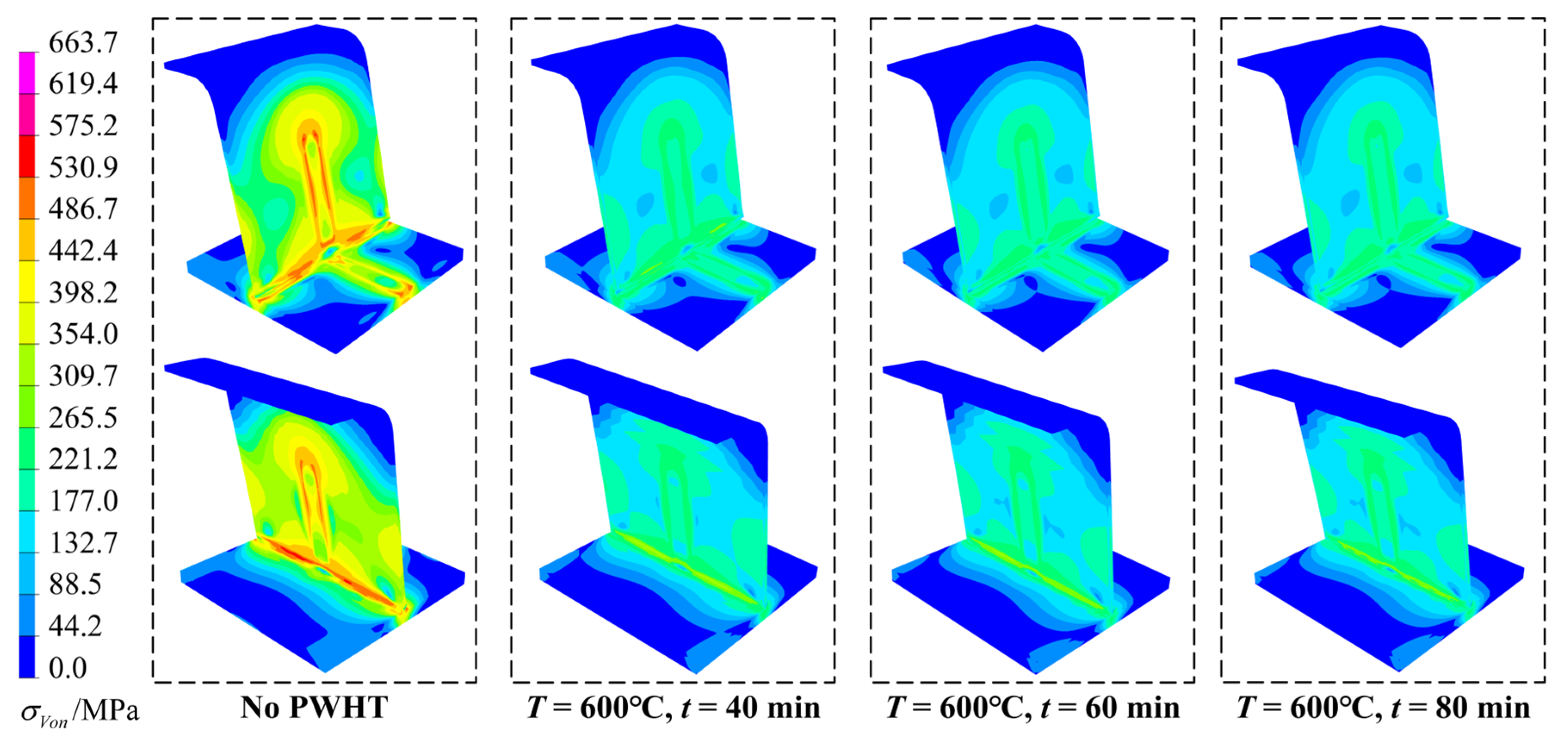

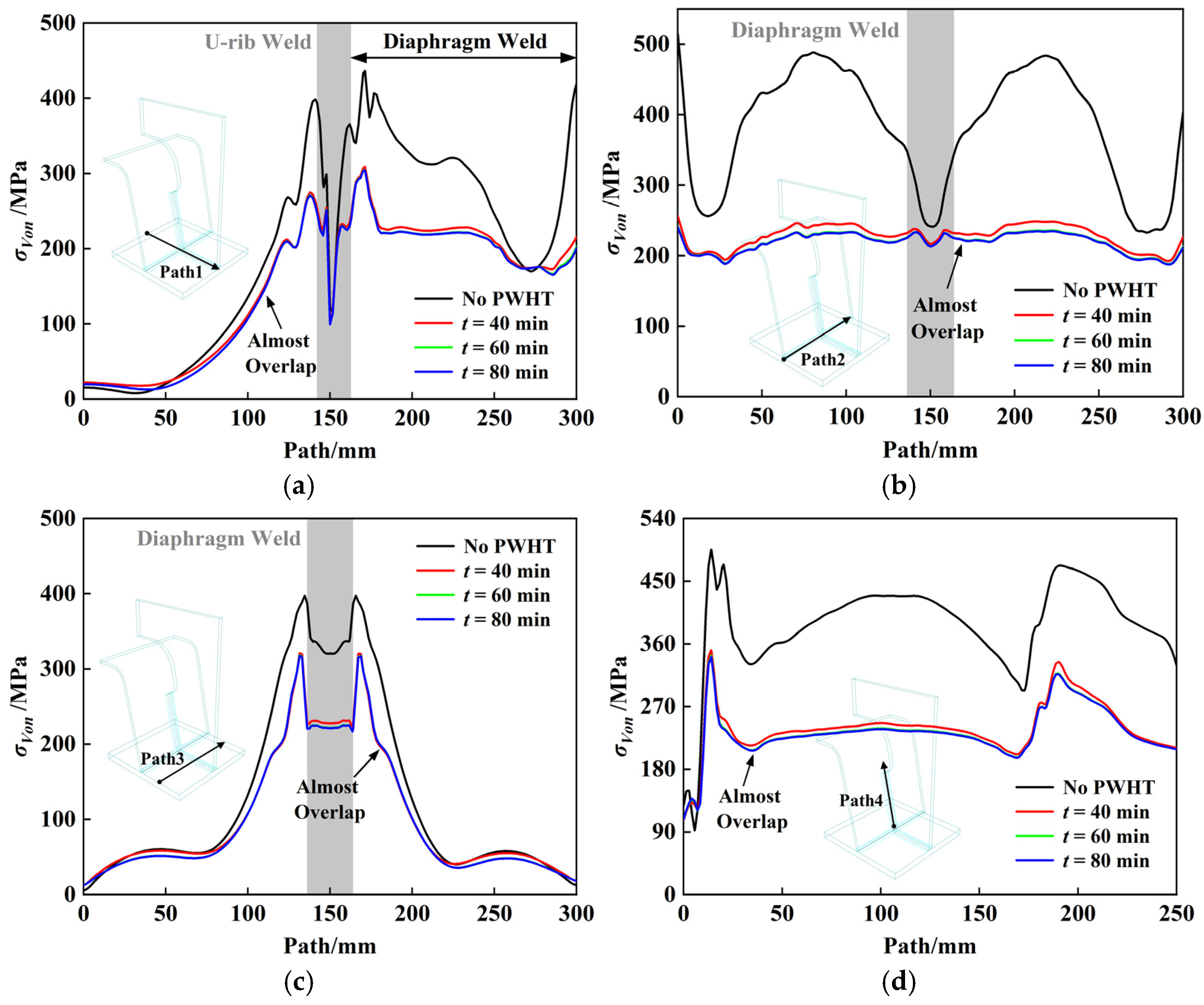

4.3. PWHT Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wolchuk, R. Orthotropic Redecking of Bridges on the North American Continent. Struct. Eng. Int. 1992, 2, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, A.S.; El-Madawy, M.E.-T.; Atef Gobran, Y. Using Artificial Neural Networks in the Design of Orthotropic Bridge Decks. Alex. Eng. J. 2016, 55, 3195–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Q.; Bao, Y.; Zhu, J.; Chen, L.; Bu, Y. An Equivalent Structural Stress-Based Fatigue Evaluation Framework for Rib-to-Deck Welded Joints in Orthotropic Steel Deck. Eng. Struct. 2019, 196, 109304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, H.-B.; Uang, C.-M. Stress Analyses and Parametric Study on Full-Scale Fatigue Tests of Rib-to-Deck Welded Joints in Steel Orthotropic Decks. J. Bridge Eng. 2012, 17, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Ding, Y.; Wei, X.; Li, A.; Geng, F. Fatigue Failure and Optimization of Double-Sided Weld in Orthotropic Steel Bridge Decks. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2020, 116, 104750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Nitschke-Pagel, T.; Dilger, K. Generation and Distribution Mechanism of Welding-Induced Residual Stresses. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 3936–3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensel, J.; Nitschke-Pagel, T.; Tchoffo Ngoula, D.; Beier, H.-T.; Tchuindjang, D.; Zerbst, U. Welding Residual Stresses as Needed for the Prediction of Fatigue Crack Propagation and Fatigue Strength. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2018, 198, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Bao, Y.; Bu, Y. Fatigue Behavior of Orthotropic Composite Deck Integrating Steel and Engineered Cementitious Composite. Eng. Struct. 2020, 220, 111017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, P.; Karakas, Ö.; Qian, H. State-of-the-Art of Fatigue Performance and Estimation Approach of Orthotropic Steel Bridge Decks. Structures 2024, 70, 107729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainuma, S.; Jeong, Y.-S.; Ahn, J.-H.; Yamagami, T.; Tsukamoto, S. Behavior and Stress of Orthotropic Deck with Bulb Rib by Surface Corrosion. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2015, 113, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Zhou, J.; Shu, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, J. Study on Crack Propagation Life of Corrosion Fatigue in Orthotropic Steel Deck in Steel Bridges. Structures 2023, 53, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Tian, L.; Lyu, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, Q.; Mei, H. Stability of Full-Scale Orthotropic Steel Plates under Axial and Biased Loading: Experimental and Numerical Studies. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2021, 181, 106613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Wu, C.; Wang, R.; Wei, L.; Jiang, C. Buckling Behavior of Orthotropic Steel Deck Stiffened by Slender Bulb Flats for Large Span Bridges. Thin-Walled Struct. 2023, 188, 110797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Lyu, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, Q.; Mei, H.-L. Experimental and Numerical Study on Welding Residual Stress of U-Rib Stiffened Plates. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2020, 175, 106362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Pei, J.; Ren, F.; Qin, S.; Li, Z.; Xu, G.; Wang, X. Numerical Study of Full Penetration Single- and Double-Sided U-Rib Welding in Orthotropic Bridge Decks. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Huang, W.; Wei, Y. Numerical Study on Welding Residual Stress by Double-Sided Submerged Arc Welding for Orthotropic Steel Deck. Eng. Struct. 2024, 302, 117445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohandas, T.; Madhusudan Reddy, G.; Satish Kumar, B. Heat-Affected Zone Softening in High-Strength Low-Alloy Steels. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 1999, 88, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodur, V.K.R.; Dwaikat, M.M.S. Effect of High Temperature Creep on the Fire Response of Restrained Steel Beams. Mater. Struct. 2010, 43, 1327–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Li, L.; Wu, R.; Lu, Z. Determination of High-Temperature Creep and Post-Creep Response of Structural Steels. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2022, 193, 107287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, L.; Niu, H.; Cui, Y.; Chen, X. Local Shape Adjustment and Residual Stresses of Integrally Stiffened Panel Induced by Mechanical Hammer Peening. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 91, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Jin, S.; Shen, B. Precisely Tuning the Residual Stress Anisotropy in Machine Hammer Peening. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 127, 4577–4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.; Stranghöner, N. Fatigue Behaviour of High Frequency Hammer Peened Ultra High Strength Steels. Int. J. Fatigue 2016, 82, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Gao, H.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, Y. Effects of Segmented Thermal-Vibration Stress Relief Process on Residual Stresses, Mechanical Properties and Microstructures of Large 2219 Al Alloy Rings. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 886, 161269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meo, M.; Vignjevic, R. Finite Element Analysis of Residual Stress Induced by Shot Peening Process. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2003, 34, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xiu, L.; Wu, J.; Lv, G.; Ma, J. Numerical Simulation on Residual Stress Eliminated by Shot Peening Using SPH Method. Fusion Eng. Des. 2019, 147, 111231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai-Xin, L.; Jin-Xiang, Z.; Kai, Z.; Xiao-Jie, L.; Kai, Z. Mechanism of Explosive Technique on Relieving Welding Residual Stresses. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2005, 22, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, K.; Zhao, K.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, K. A Study on the Relief of Residual Stresses in Weldments with Explosive Treatment. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2005, 42, 3794–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, P.; Song, S.; Zhang, J. Analysis of Residual Stress Relief Mechanisms in Post-Weld Heat Treatment. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2014, 122, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zheng, K.; Heng, J.; Zhu, J.; He, X. Fatigue Performance of Rib-to-Deck Joints in Orthotropic Steel Deck with PWHT. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2022, 196, 107420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, B.; Xie, Y.; Xie, Q.; Shi, J.; Liu, X.; Yao, C.; Li, Y. Influence of Post-Weld Heat Treatment on Welding Residual Stress in U-Rib-to-Deck Joint. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 196, 111550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fu, Z.; Cui, J.; Ji, B. Effect of Post-Weld Heat Treatment on Residual Stress in Deck-Rib Double-Side Welded Joints and Process Optimization. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 164, 108731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Qiang, B.; Xie, Y.; Xie, Q.; Zou, Y.; Yao, C.; Li, Y. PWHT Influence on Welding Residual Stress in 45 Mm Bridge Steel Butt-Welded Joint. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2024, 217, 108674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Qiang, B.; Liao, X.; Kang, L.; Yao, C.; Li, Y. Experimental Investigation and Numerical Simulation of Welding Residual Stress in Orthotropic Steel Deck with Diaphragm Considering Solid-State Phase Transformation. Eng. Struct. 2022, 250, 113415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldak, J.; Chakravarti, A.; Bibby, M. A New Finite Element Model for Welding Heat Sources. Met. Trans. B 1984, 15, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, P.; Berto, F.; Meneghello, R. Setup of a Numerical Model for Post Welding Heat Treatment Simulation of Steel Joints. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2021, 33, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetri Selvan, R.; Sathiya, P.; Ravichandran, G. Characterisation of Transient Out-of-Plane Distortion of Nipple Welding with Header Component. J. Manuf. Process. 2015, 19, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathar, J. Determination of Initial Stresses by Measuring the Deformations Around Drilled Holes. J. Fluids Eng. 1934, 56, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Heogh, W.; Ju, H.; Kang, S.; Jang, T.-S.; Jung, H.-D.; Jahazi, M.; Han, S.C.; Park, S.J.; Kim, H.S.; et al. Functionally Graded Structure of a Nitride-Strengthened Mg2Si-Based Hybrid Composite. J. Magnes. Alloys 2024, 12, 1239–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Composition | C | Mn | Si | P | S | Ni | Cr | Mo | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 0.05 | 1.47 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 0.004 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.004 | residual amount |

| Weld Number | I/A | U/V | v/(mm·s−1) | a1/mm | a2/mm | b/mm | c/mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WS_1 | 340 | 32 | 5.83 | 4.5 | 18.0 | 4.5 | 5.0 |

| WS_2 | 620 | 32 | 6.67 | 7.0 | 28.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 |

| WS_3~WS_6 | 630 | 30 | 6.67 | 7.0 | 28.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 |

| Scheme | (I) | (II) | (III) | (IV) | (V) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holding temperature (°C) | 500 | 550 | 600 | 600 | 600 |

| Holding time (min) | 40 | 40 | 40 | 60 | 80 |

| Path | Measuring Point | (t = 40 min, EXP) | (t = 40 min) | Error | (t = 60 min) | Error | (t = 80 min) | Error | Average Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 204 | 228 | −24 | 223 | −19 | 222 | −18 | −20.33 |

| 2 | 237 | 227 | 10 | 221 | 16 | 221 | 16 | 14.00 | |

| 3 | 182 | 205 | −23 | 201 | −19 | 201 | −19 | −20.33 | |

| 4 | 189 | 174 | 15 | 167 | 22 | 169 | 20 | 19.00 | |

| 2 | 5 | 222 | 205 | 17 | 202 | 20 | 202 | 20 | 19.00 |

| 6 | 221 | 220 | 1 | 209 | 12 | 209 | 12 | 8.33 | |

| 7 | 208 | 240 | −32 | 226 | −18 | 226 | −18 | −22.67 | |

| 8 | 258 | 244 | 14 | 232 | 26 | 232 | 26 | 22.00 | |

| 9 | 212 | 243 | −31 | 231 | −19 | 231 | −19 | −23.00 | |

| 10 | 215 | 247 | −32 | 233 | −18 | 233 | −18 | −22.67 | |

| 11 | 241 | 225 | 16 | 216 | 25 | 216 | 25 | 22.00 | |

| 12 | 214 | 201 | 13 | 194 | 20 | 194 | 20 | 17.67 | |

| 3 | 13 | 114 | 132 | −18 | 132 | −18 | 132 | −18 | −18.00 |

| 14 | 103 | 129 | −26 | 134 | −31 | 134 | −31 | −29.33 | |

| 4 | 15 | 233 | 218 | 15 | 211 | 22 | 211 | 22 | 19.67 |

| 16 | 200 | 235 | −35 | 227 | −27 | 228 | −28 | −30.00 | |

| 17 | 215 | 244 | −29 | 235 | −20 | 237 | −22 | −23.67 | |

| 18 | 231 | 215 | 16 | 210 | 21 | 209 | 22 | 19.67 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Q.; Chen, H.; Hu, Z.; Wang, R.; Dong, C. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Post-Weld Heat Treatment on Residual Stress Relaxation in Orthotropic Steel Decks Welding. Buildings 2025, 15, 4319. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234319

Li Q, Chen H, Hu Z, Wang R, Dong C. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Post-Weld Heat Treatment on Residual Stress Relaxation in Orthotropic Steel Decks Welding. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4319. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234319

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Qinhe, Hao Chen, Zhe Hu, Ronghui Wang, and Chunguang Dong. 2025. "Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Post-Weld Heat Treatment on Residual Stress Relaxation in Orthotropic Steel Decks Welding" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4319. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234319

APA StyleLi, Q., Chen, H., Hu, Z., Wang, R., & Dong, C. (2025). Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Post-Weld Heat Treatment on Residual Stress Relaxation in Orthotropic Steel Decks Welding. Buildings, 15(23), 4319. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234319