Optimal Static Performance Analysis of Large-Span Space Aluminum String-Beam Structures

Abstract

1. Introduction

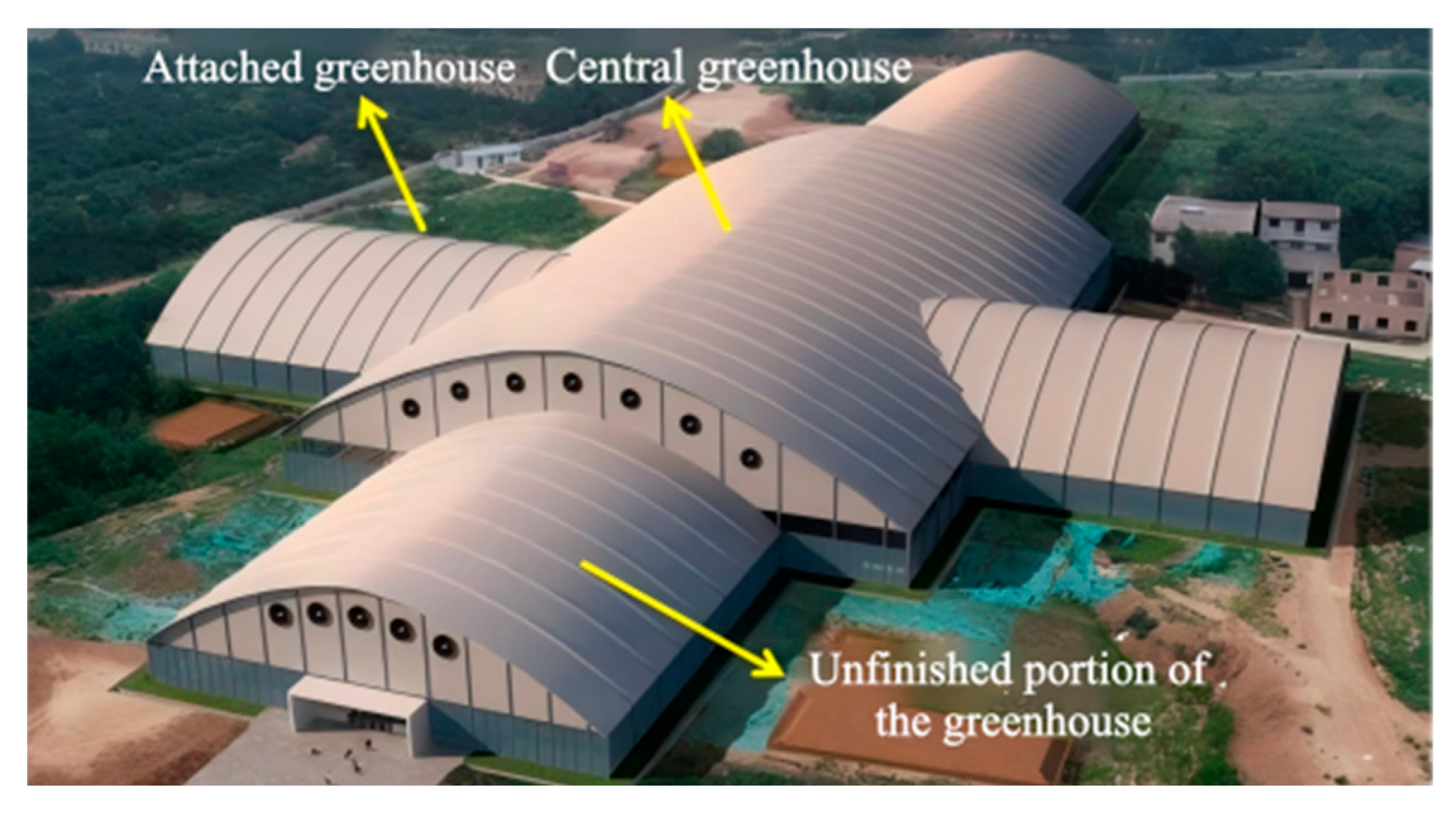

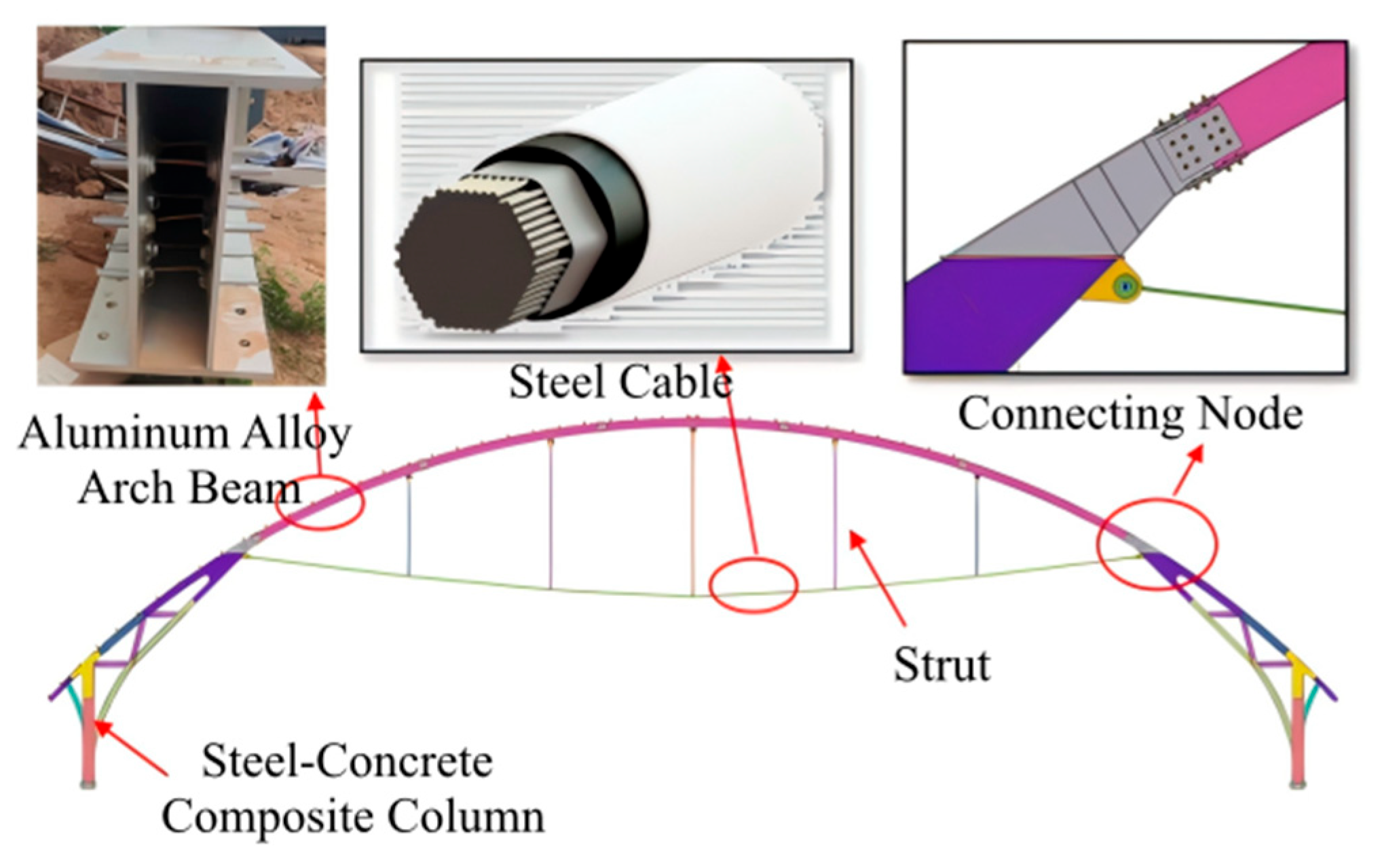

2. Project Overview

3. Static Performance Analysis

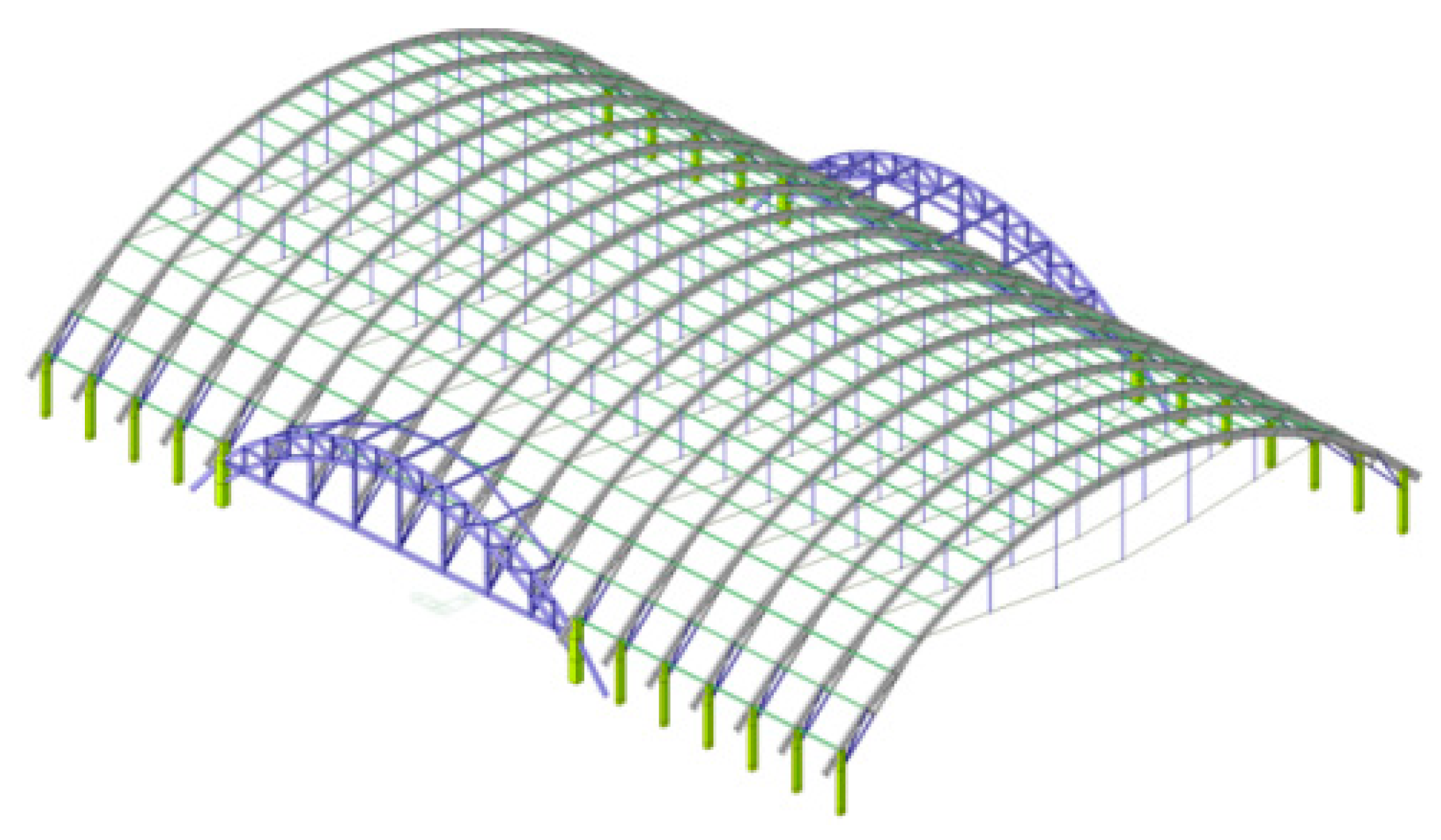

3.1. Establish a Finite Element Model

3.2. Design Parameters and Load Combinations

3.2.1. Design Parameters

3.2.2. Load Combinations

3.3. Static Calculation Results

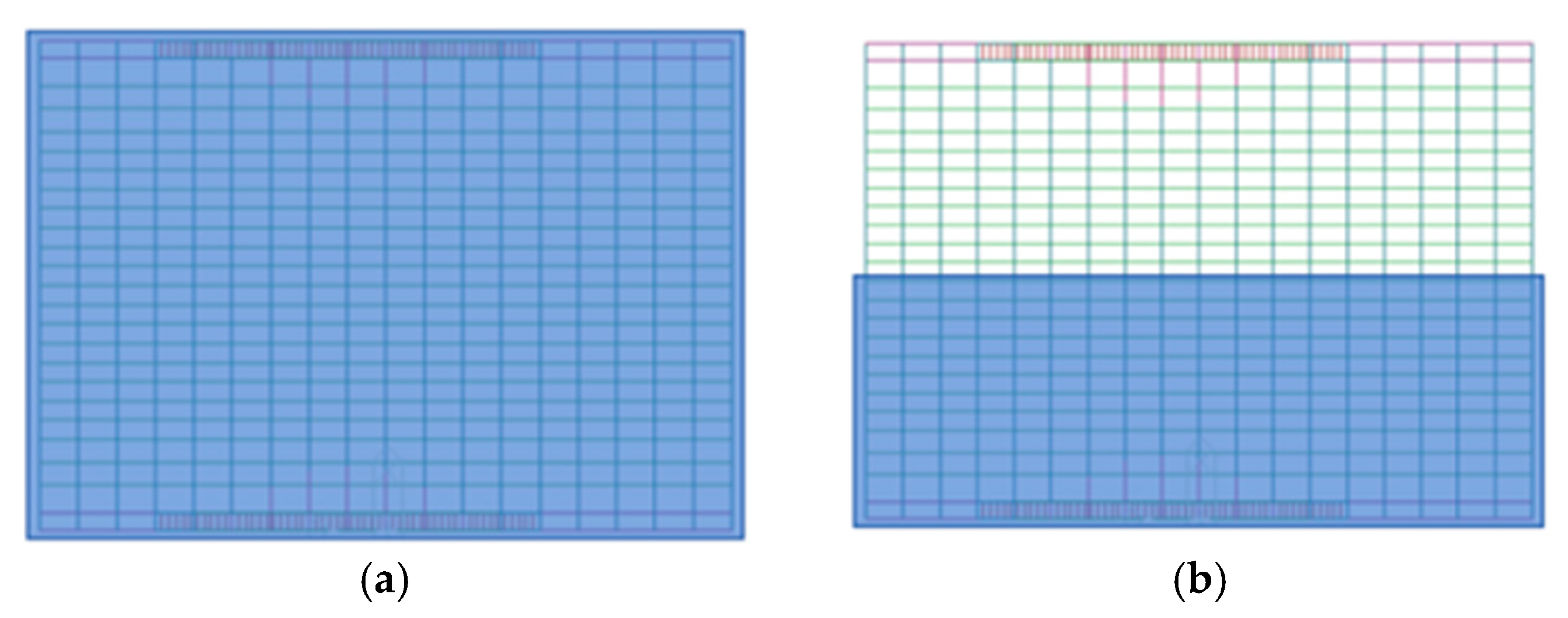

3.3.1. Influence of Snow Load Distribution on Structural Static Performance

- (1)

- Under the SC6-II load condition, the maximum vertical displacement of the structure is 108.72 mm. Compared with the SC6-I condition, the maximum displacement decreases by 3.54 mm under SC6-III and by 1.54 mm under SC6-IV. The relatively small variation in maximum vertical displacement across loading scenarios indicates that the snow load distribution pattern has only a limited influence on overall structural deformation.

- (2)

- The maximum structural stress occurs under the SC6-I condition, corresponding to full-span snow load, with a peak value of 152.85 MPa. Under SC6-IV, the maximum stress is 152.64 MPa-differing by only 0.21 MPa from the full-span case. Moreover, the stress distribution trends in the rear half-span are nearly identical under both load combinations, and the locations of maximum compressive stress closely align. In contrast, the maximum stress under SC6-III decreases by 15.66% compared to SC6-IV. This reduction is mainly due to structural asymmetry near the transition truss section, where variations in load distribution exert a more pronounced effect on stress response. Therefore, targeted reinforcement of structurally vulnerable regions should be considered during design to improve overall reliability.

3.3.2. Effect of Temperature Loads on Structural Static Performance

- (1)

- Under constant load, the maximum vertical displacement of the structure is 32.21 mm, primarily occurring in regions not connected to the transfer truss. Under the LC4 load condition, the aluminum alloy arch beam deforms upward, with a maximum displacement of 43.68 mm, reversing its initial downward deflection. This behavior results from the significantly higher coefficient of thermal expansion of aluminum alloy compared to steel, causing substantial thermal expansion under elevated temperatures. The deformation at the base of the arch beam is constrained by the steel–concrete composite columns, inducing upward arching. Consequently, both the struts and prestressed cables deflect upward due to their mechanical interaction with the expanding arch beam. Under LC5 loading, the entire structure deforms downward, with a maximum displacement of 137.31 mm—within the allowable limits specified by the design code.

- (2)

- The structural system exhibits notable sensitivity to low-temperature effects. It is therefore essential to carefully evaluate displacement behavior under extreme temperature conditions during the design phase and to implement local reinforcement in vulnerable regions. Furthermore, the application of this structural system in extremely cold climates should be appropriately restricted.

3.3.3. Effect of Wind Loads on Structural Static Performance

- (1)

- Under SC2 loading, the maximum vertical displacement of the structure is 23.57 mm, representing a 51.29% reduction compared to the SC1 condition. The maximum stress is 40.27 MPa, corresponding to a 49.90% decrease relative to SC1. Both values remain well below the design strength of the aluminum alloy, indicating sufficient safety margins.

- (2)

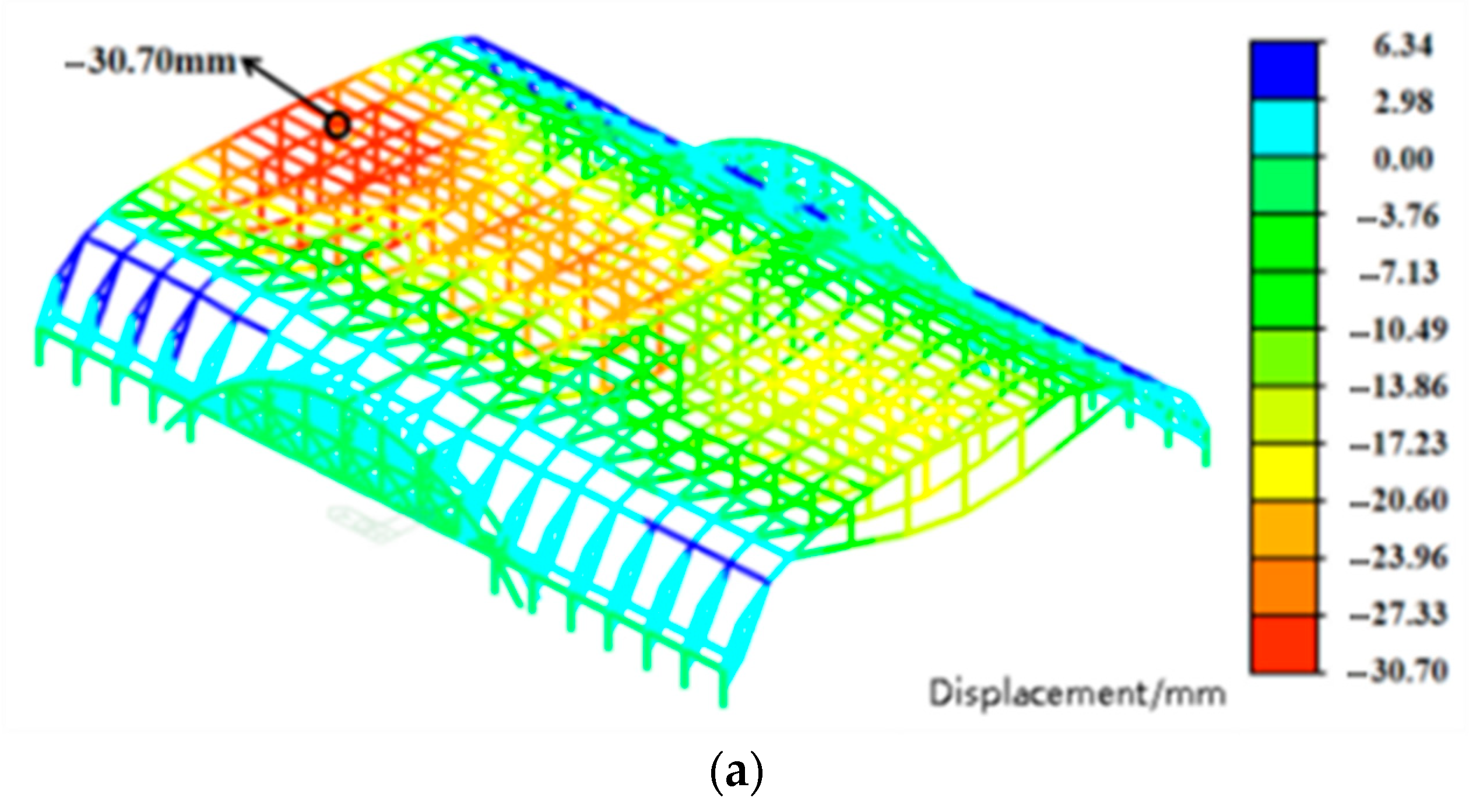

- Under SC3 loading, the maximum vertical displacement is 30.70 mm, a 43.80% reduction compared to SC1. The displacement distribution pattern is consistent with that under SC2, with the maximum displacement occurring at approximately the same nodal location. Under both wind load cases, structural vertical displacement and stress are reduced to varying degrees, indicating that wind-induced upward suction partially counteracts the downward deformation caused by gravity loads.

- (3)

- Throughout the wind loading process, the cables remain in tension without slackening or failure, confirming the overall structural safety. In the design of similar structures, the uplifting effects of wind loads should be carefully considered to prevent potential instability resulting from cable relaxation or prestress loss.

4. Design Parameter Optimization Analysis

4.1. Number of Struts

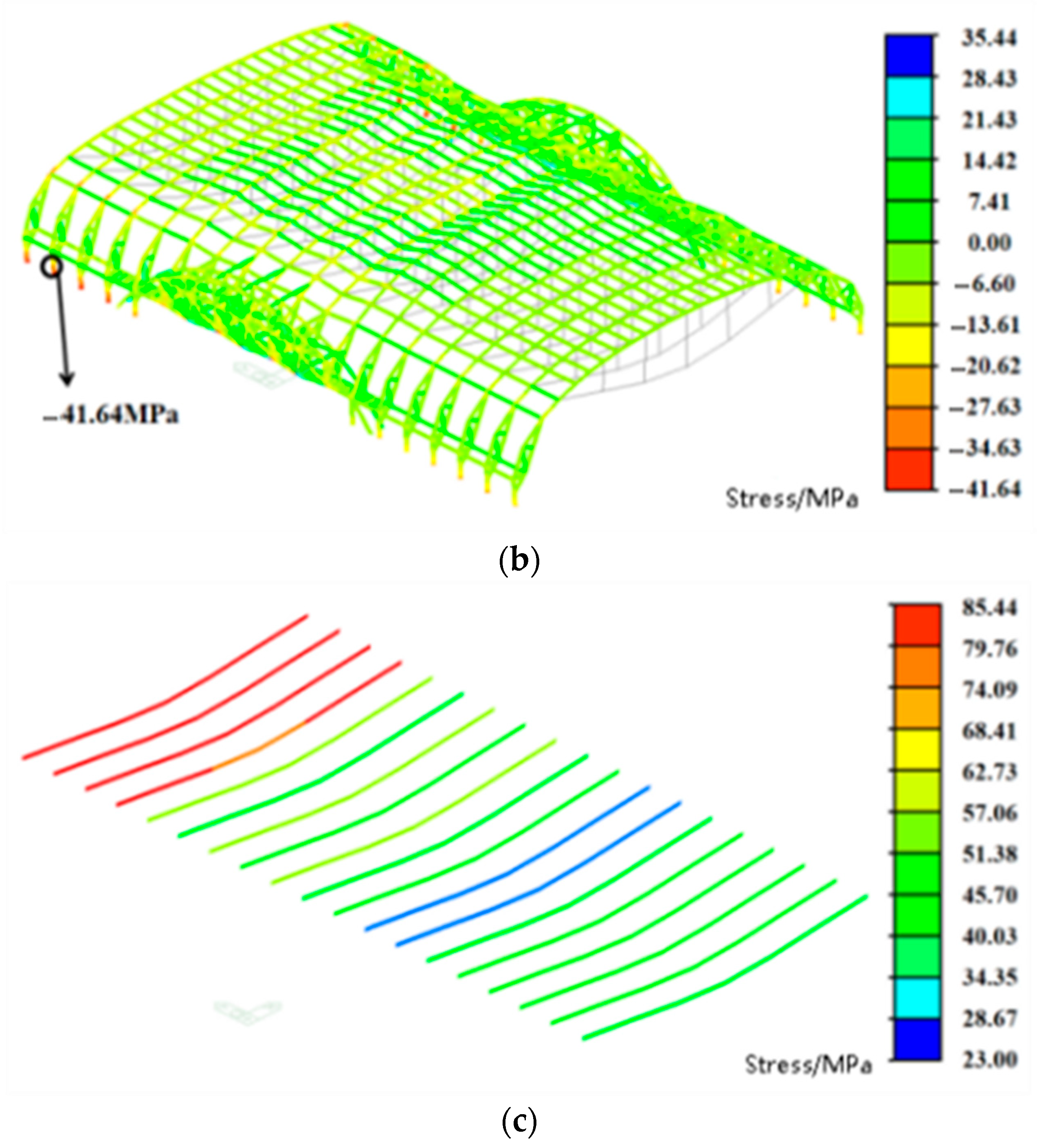

- (1)

- The vertical displacement at mid-span decreases as the number of struts increases. Beyond five struts, however, the rate of displacement reduction diminishes significantly. When the number of struts increases from one to five, the displacement decreases by less than 6%. With fifteen struts, the mid-span vertical displacement under load case LC1 is 61.21 mm—only 1.2 mm less than that of the reference model.

- (2)

- The cable internal force decreases with an increasing number of struts. When the number of struts rises from one to five, the reduction in cable force is less than 4%. Further increasing the number of struts beyond five has a negligible effect on the cable internal force. The maximum axial force in the struts initially decreases and then increases, reaching a minimum at five struts. When fifteen struts are used, the maximum axial force under LC1 reaches 7.38 kN, a 15.31% increase compared to the reference model.

- (3)

- The maximum stress in the aluminum alloy beam increases slightly with the number of struts, though the trend is not pronounced. As the number of struts increases from one to fifteen, the maximum beam stress under LC1 rises by only 3.92%.

- (4)

- Overall, the number of struts has a limited influence on mid-span displacement, cable internal force, and maximum beam stress, but a more noticeable effect on the maximum axial force in the struts. Excessively increasing the number of struts complicates construction and raises material costs, while too few struts may compromise structural safety. Therefore, a configuration of five to seven struts is recommended to balance structural performance and constructability.

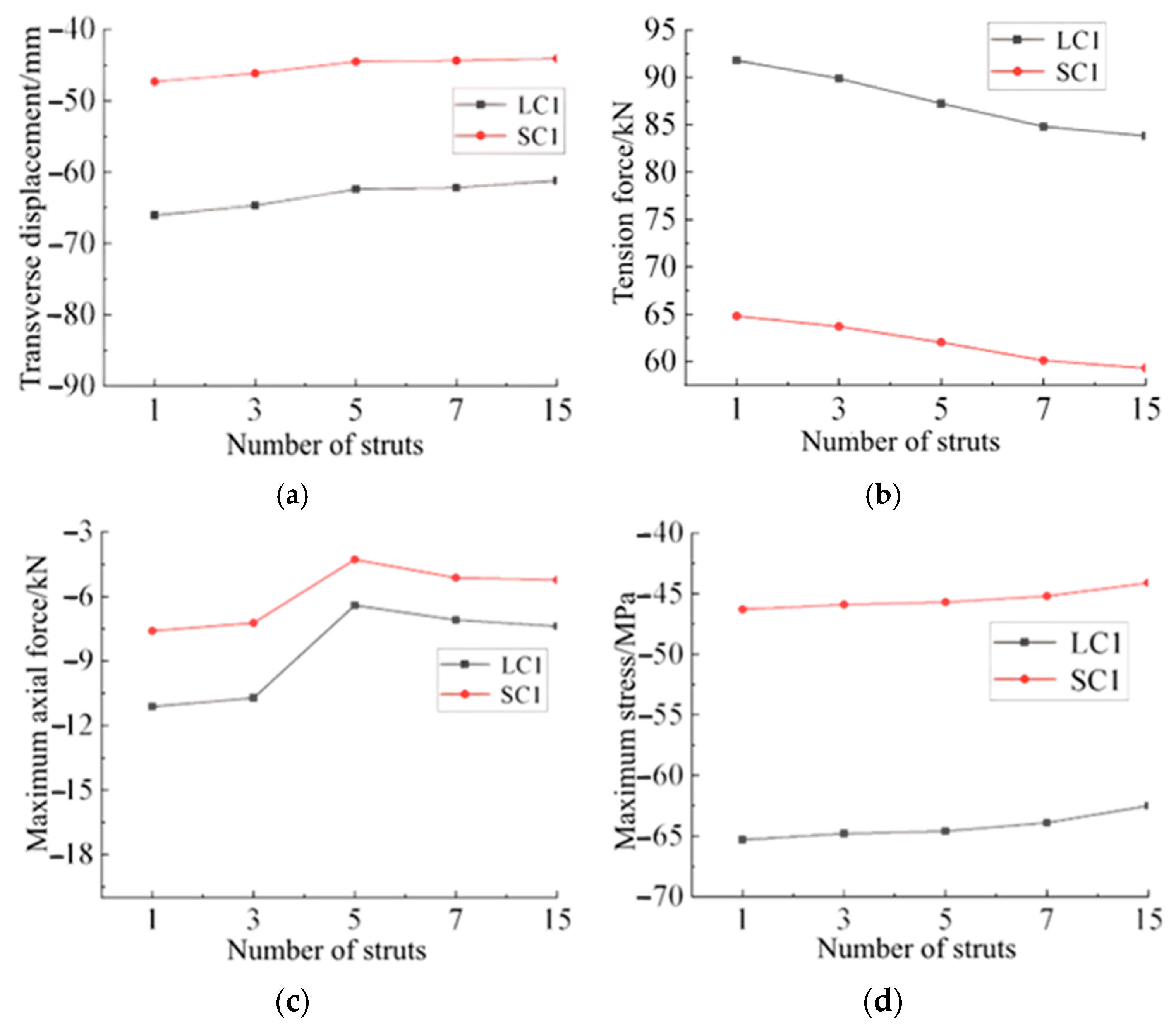

4.2. Cross-Sectional Area of the Cable

4.3. Cable Prestressing

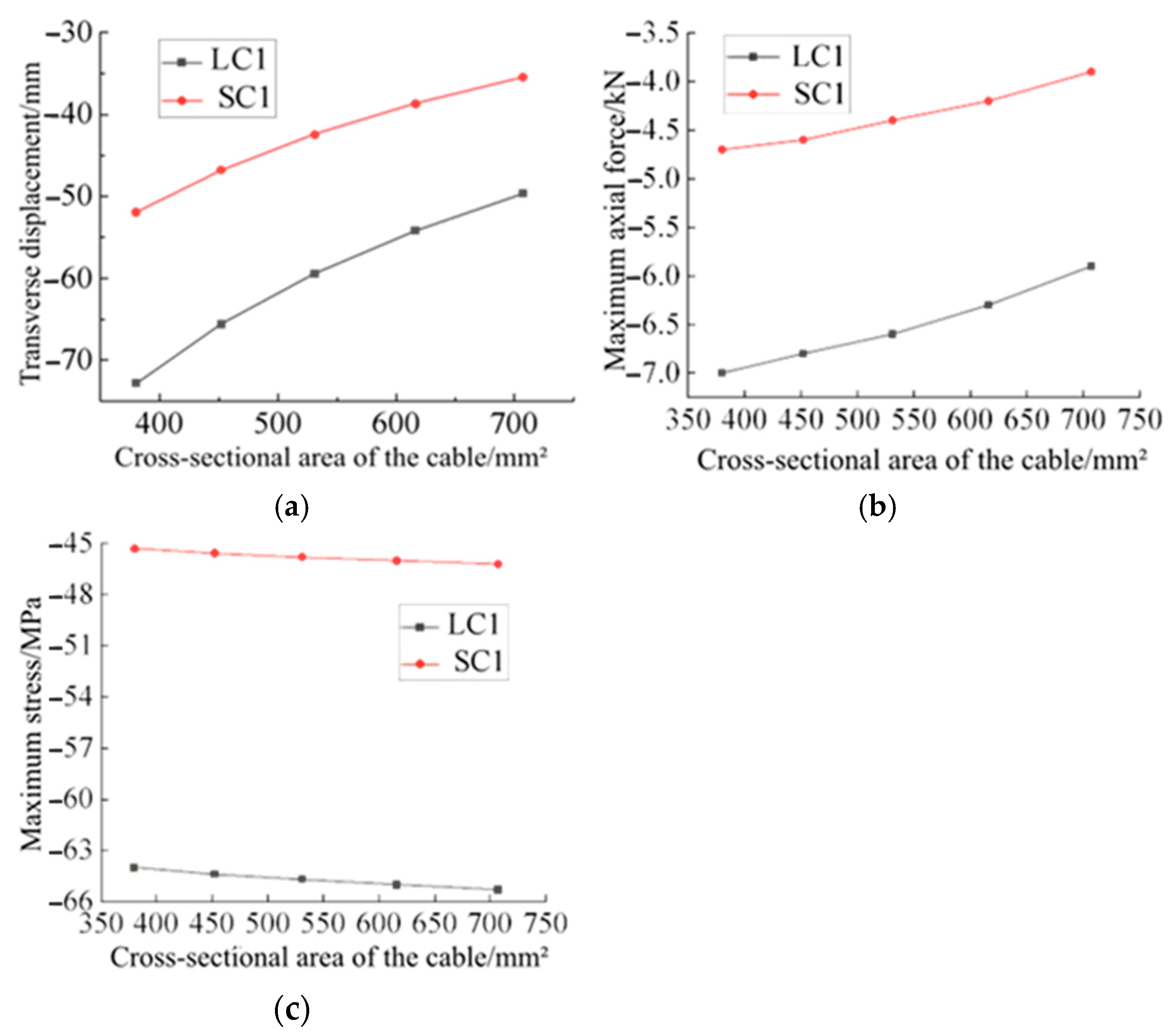

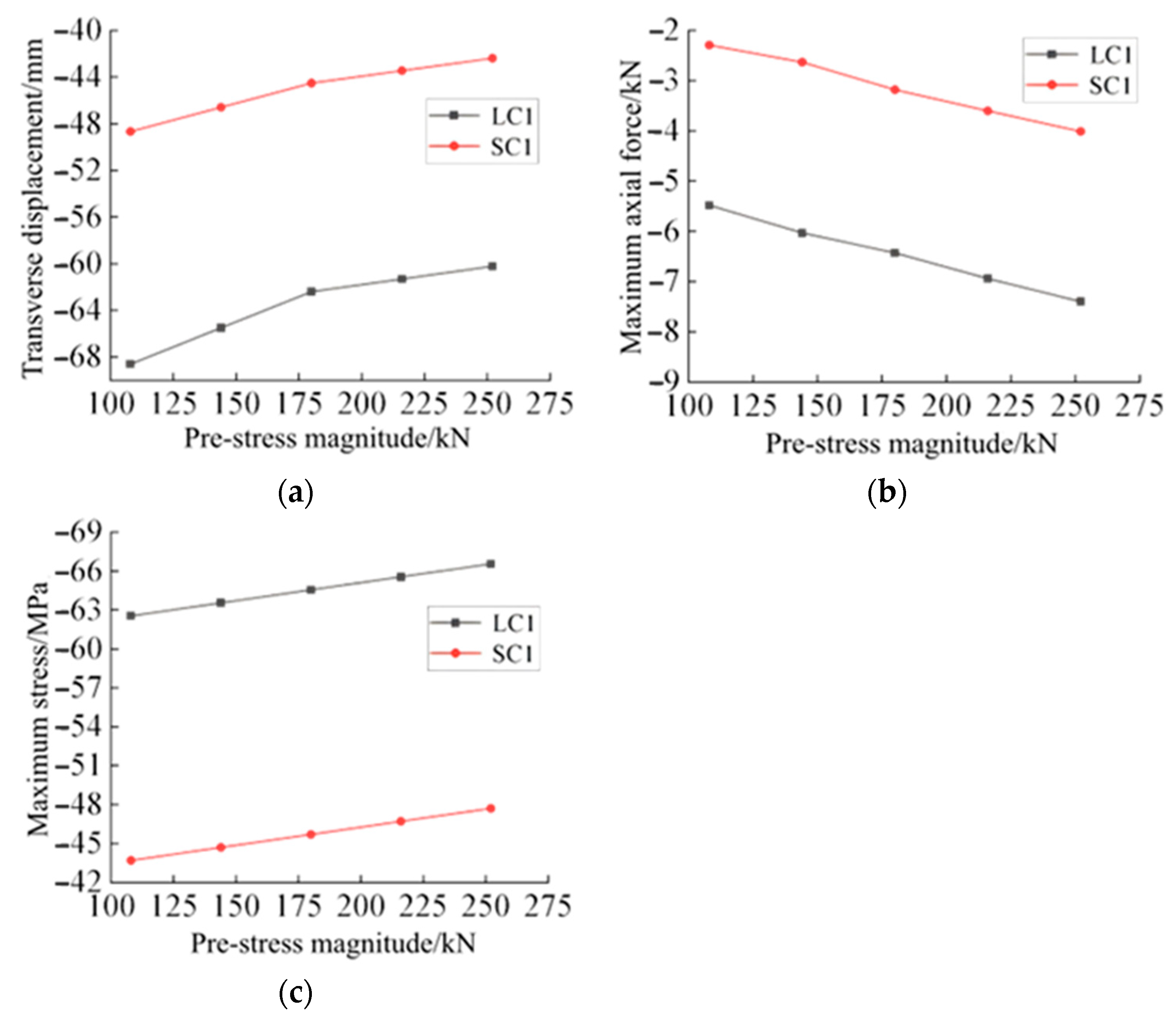

- (1)

- With increasing cable prestress, the mid-span displacement of the structure decreases progressively. Under the SC1 loading condition, as the prestress increases from 108 kN to 180 kN, the mid-span displacement decreases by 9.08%. A further increase in prestress from 180 kN to 252 kN results in a mid-span displacement reduction of only 3.89% under the SC1 loading condition, indicating a diminishing effect of prestress augmentation on controlling structural deformation.

- (2)

- The maximum axial force in the struts increases significantly with higher cable prestress. When the prestress reaches 1.4 times the reference value, the maximum axial force under LC1 loading increases by 15.37% compared to the baseline model.

- (3)

- The maximum stress in the aluminum alloy beam increases approximately linearly with the prestressing force. As the prestress rises from 0.6 to 1.4 times the baseline value, the maximum beam stress under LC1 loading increases by only 4.09 MPa, suggesting that the influence of prestress on beam stress remains limited.

4.4. Cable Sag-to-Span Ratio

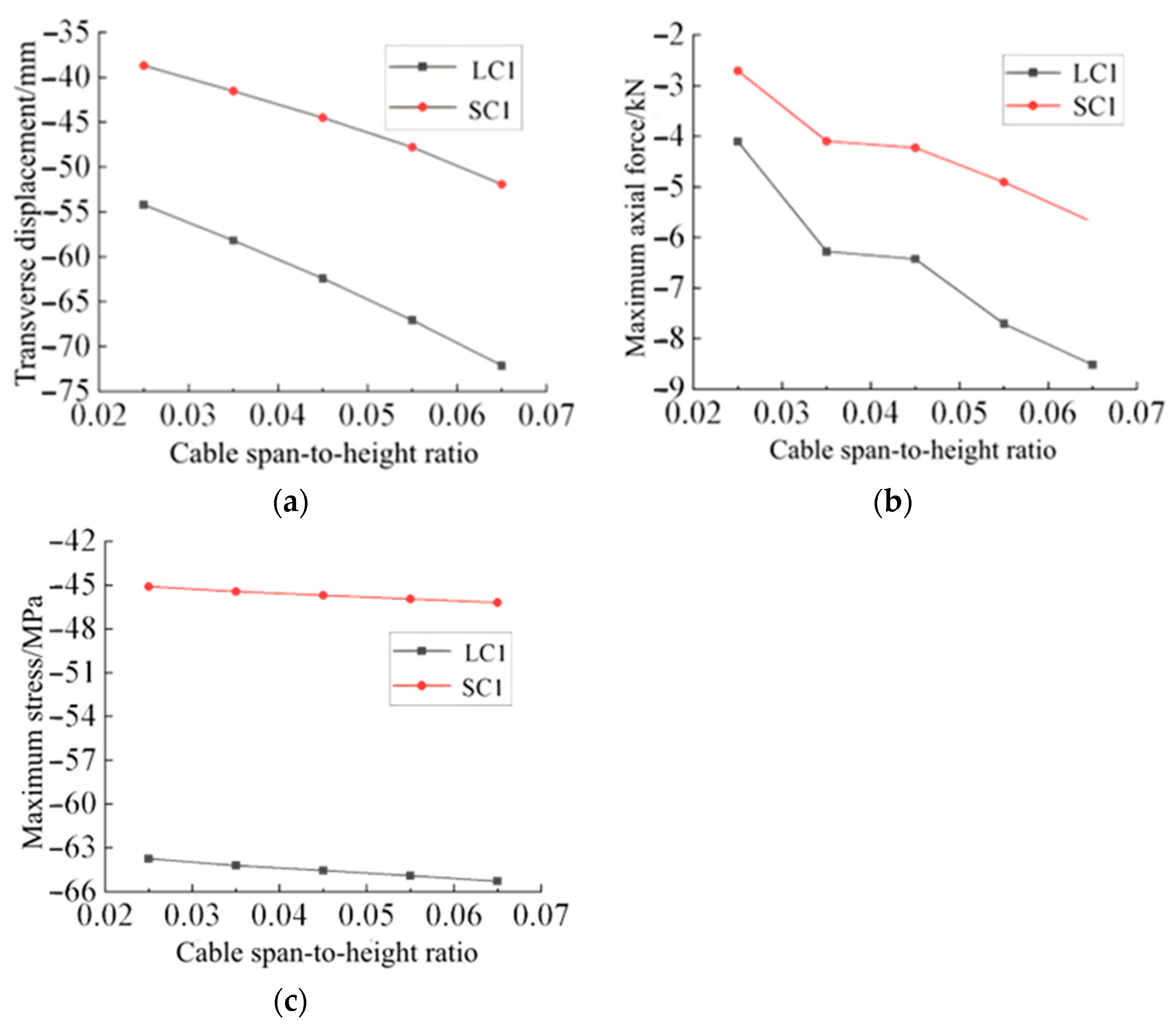

- (1)

- Under both LC1 and SC1 loading conditions, the mid-span displacement increases approximately linearly with the cable sag-to-span ratio. When the ratio rises from 0.025 to 0.065, the mid-span displacement increases by 33.51%.

- (2)

- As the cable sag-to-span ratio increases from 0.025 to 0.035, the maximum axial force in the struts under LC1 loading rises markedly by 47.84%, underscoring the significant influence of this parameter on structural behavior. Beyond a ratio of 0.035, the effect on strut axial force becomes less pronounced. Although the maximum stress in the aluminum alloy beam also increases with the sag-to-span ratio, the overall variation remains relatively small.

- (3)

- Variations in the cable sag-to-span ratio have a limited influence on the maximum stress in the aluminum alloy beam, with increases kept below 3% across the range studied. In structural design, however, the sag-to-span ratio substantially affects global displacement and strut axial force. It is therefore essential to comprehensively evaluate its impact on all key components to achieve an optimal balance among stiffness, stability, and material efficiency.

4.5. Design Recommendations

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The TABS exhibits favorable static performance under all load combinations. The maximum stress and vertical displacement are 189.45 MPa and 137.31 mm, respectively, both complying with design code requirements.

- (2)

- The structure is particularly sensitive to deformation under low-temperature conditions. Design of similar systems should carefully account for temperature-induced effects and incorporate local reinforcement in critical regions prone to stress concentration.

- (3)

- Based on a combined assessment of stiffness, force distribution, and constructability, the following parameter ranges are recommended for optimal design: 5–7 struts, cable sag-to-span ratio of 0.035–0.045, cable cross-sectional area of 500–600 mm2, and prestress level of 1.0–1.2 times the reference value.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zeng, J.; Lv, H.; Zhu, Z.; Dong, S.; Liu, Y.; Feng, X.; Li, W.; Shao, L. Seismic performance of pentagonal type aluminum alloy suspen-dome structure with large opening. Structures 2024, 69, 107312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, X.; Xing, Z.; Jiang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Qiu, H.; Nie, R.; Yang, J.; Hui, D.; Chen, W.; et al. A review of research on aluminum alloy materials in structural engineering. Dev. Built Environ. 2024, 17, 100319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. The use of aluminum alloys in structures: Review and outlook. Structures 2023, 57, 105290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgantzia, E.; Gkantou, M.; Kamaris, G.S. Aluminium alloys as structural material: A review of research. Eng. Struct. 2021, 227, 111372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yun, X.; Wang, Y.; Ma, C.; Yan, J.-B. Numerical study and design of swage-locking pinned aluminium alloy shear connections. Thin-Walled Struct. 2023, 190, 110949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ma, C.; Yun, X.; Han, Q.; Li, B.; Wang, Z. Experimental study on structural performance of 7A04-T6 high-strength aluminium alloy shear connections in and after fire. Eng. Struct. 2024, 309, 118028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhan, L.; Yun, X. Experimental study of local buckling behaviour of 7A04-T6 high strength aluminium alloy H-section stub columns in fire. Eng. Struct. 2024, 317, 118631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, M.; Han, Q.; Yun, X.; Zhou, K.; Gardner, L.; Mazzolani, F.M. Structural fire behaviour of aluminium alloy structures: Review and outlook. Eng. Struct. 2022, 268, 114746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, Y. Generative design and topology optimization research for single-layer aluminum alloy grid shell connections. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Li, F.; Shao, F.; Zhang, D. Static and dynamic behaviour of a hybrid PFRP-aluminium space truss girder: Experimental and numerical study. Compos. Struct. 2020, 243, 112226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.H.; Pham, C.H.; Rasmussen, K.J. Global buckling capacity of cold-rolled aluminium alloy channel section beams. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2021, 179, 106521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.H.; Pham, C.H.; Rasmussen, K.J. Member capacity of cold-rolled aluminium alloy channel columns—Part I: Experimental investigation. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 200, 111959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhi, X.; Li, B.; Chen, B.; Ouyang, Y. Local buckling behaviour of 7075-T6 high strength aluminium alloy H-section beams under concentrated loads: Testing, modelling and design. Eng. Struct. 2025, 334, 120201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Fan, F. Static properties and stability of super-long span aluminum alloy mega-latticed structures. Structures 2021, 33, 3173–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Xiao, S.; Wu, J.; Yu, S.; Wei, M.; Qin, J.; Zang, M. Study on the static stability of aluminum alloy single-layer spherical reticulated shell. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Xiao, S.; Wu, J.; Zheng, J.; Qin, J. Shaking table test and simulation on seismic performance of aluminum alloy reticulated shell structures under elastic and elastic-plastic stage. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, B.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Wu, C. Experimental and numerical studies of impact loading on single-layer reticulated shells with aluminium alloy gusset joints. Eng. Struct. 2024, 302, 117403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Huang, H.; Du, B. Dynamic buckling behaviour of aluminum alloy thin cylindrical shell under axial impact load: Experimental study. Thin-Walled Struct. 2025, 209, 112889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, Z.; Liu, X.; Ouyang, Y. Study on the compressive stability of H-shaped members with roof-connection construction in aluminum alloy latticed shell. Eng. Struct. 2024, 311, 118176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Zhu, S.; Zou, X.; Guo, S.; Qiu, Y.; Li, L. Elasto-plastic buckling behaviour of aluminium alloy single-layer cylindrical reticulated shells with gusset joints. Eng. Struct. 2021, 242, 112562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascolo, I.; Sarfarazi, S.; Modano, M. Feasible and robust optimisation of cable forces in suspended bridges: A two-stage metaheuristic approach. Mech. Res. Commun. 2025, 150, 104554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Aluminum Alloy Arch Beam | Strut | Cable | Tie Rod |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material | 6061-T6 | Q355B | PE-sheathed steel strand | Q235B |

| Cross-sectional area/mm2 | DH500 × 350 × 12 × 16 | 200 × 16 | 5 × 37 | ☐150 × 75 × 3 × 3 |

| Modulus of elasticity (MPa) | 7.0 × 104 | 2.06 × 105 | 1.95 × 105 | 2.0 × 105 |

| Yield Strength (MPa) | 240 | 355 | 1570 | 235 |

| Ultimate Strength (MPa) | 260 | 540 | 2100 | 460 |

| Poisson’s Ratio | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.28 | 0.3 |

| Density (kg/m3) | 2.7 × 103 | 7.85 × 103 | 7.85 × 103 | 7.85 × 103 |

| Thermal Expansion Coefficient (1/°C) | 23.6 × 10−6 | 12 × 10−6 | 11.7 × 10−6 | 12 × 10−6 |

| Type | Number | Load Combination |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Load Combination | LC1 | 1.3D + 1.5L |

| LC2 | 1.3D + 1.5Wx+ | |

| LC3 | 1.3D + 1.5Wy+ | |

| LC4 | 1.3D + 1.5T+ | |

| LC5 | 1.3D + 1.5T− | |

| LC6 | 1.3D + 1.5L + 0.9Wx+ | |

| LC7 | 1.3D + 1.05L + 1.5Wx+ + 0.9T+ | |

| LC8 | 1.3D + 1.05L + 1.5Wx+ + 0.9T− | |

| LC9 | 1.3D + 1.05L + 1.5Wy+ + 0.9T+ | |

| LC10 | 1.3D + 1.05L + 1.5Wy+ + 0.9T− | |

| Standard Load Combination | SC1 | 1.0D + 1.0L |

| SC2 | 1.0D + 1.0L + 0.6Wx+ | |

| SC3 | 1.0D + 1.0L + 0.6Wy+ | |

| SC4 | 1.0D + 0.7L + 1.0T+ | |

| SC5 | 1.0D + 0.7L + 1.0T− | |

| SC6 | 1.0D + 1.0SL | |

| SC7 | 1.0D + 1.0L + 0.6Wx+ + 0.6T+ | |

| SC8 | 1.0D + 1.0L + 0.6Wx+ + 0.6T− | |

| SC9 | 1.0D + 1.0L + 0.6Wy+ + 0.6T+ | |

| SC10 | 1.0D + 1.0L + 0.6Wy+ + 0.6T− |

| Load Combination | Displacement/mm | Stress/MPa |

|---|---|---|

| LC1 | −67.65 | −112.13 |

| LC2 | 39.90 | −54.61 |

| LC3 | 42.54 | −65.25 |

| LC4 | 43.68 | −189.45 |

| LC5 | −137.31 | −105.79 |

| LC6 | −30.62 | −51.97 |

| LC7 | 57.57 | −122.41 |

| LC8 | −60.12 | −103.21 |

| LC9 | 60.03 | −122.34 |

| LC10 | −77.87 | −106.03 |

| SC1 | −48.39 | −80.38 |

| SC2 | −23.57 | −40.27 |

| SC3 | −30.70 | −41.64 |

| SC4 | 28.93 | −133.16 |

| SC5 | −111.35 | −114.61 |

| SC6 | −108.72 | −115.55 |

| SC7 | 15.85 | −81.78 |

| SC8 | −65.42 | −69.07 |

| SC9 | 17.72 | −83.85 |

| SC10 | −72.56 | −69.61 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, N.; Xiao, K.; Li, J.; Mi, W.; Hui, C. Optimal Static Performance Analysis of Large-Span Space Aluminum String-Beam Structures. Buildings 2025, 15, 4443. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244443

Wang N, Xiao K, Li J, Mi W, Hui C. Optimal Static Performance Analysis of Large-Span Space Aluminum String-Beam Structures. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4443. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244443

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Nan, Kai Xiao, Jiale Li, Wenhao Mi, and Cun Hui. 2025. "Optimal Static Performance Analysis of Large-Span Space Aluminum String-Beam Structures" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4443. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244443

APA StyleWang, N., Xiao, K., Li, J., Mi, W., & Hui, C. (2025). Optimal Static Performance Analysis of Large-Span Space Aluminum String-Beam Structures. Buildings, 15(24), 4443. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244443