1. Introduction

The international engineering community has increasingly focused on reinforcement steel with yield strengths exceeding 400 MPa [

1,

2,

3,

4]. However, steel reinforcement materials with strength levels reaching 600 MPa or higher remain relatively uncommon in practical applications. While hot-rolled high-strength reinforcement has been implemented in actual construction projects, comprehensive investigations into both the material characteristics of these high-strength steels and the structural performance of corresponding members remain limited [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

Several research teams have made significant contributions to this field. Guan et al. [

5] and Sun et al. [

6] pioneered studies on the fundamental properties of 600 MPa high-strength reinforcement materials. Concurrently, Li et al. [

7] and Sun et al. [

8] evaluated the seismic resistance of concrete columns reinforced with 600 MPa and 630 MPa steel bars as principal longitudinal reinforcement. Additionally, Rong et al. [

9] and Sun et al. [

10] conducted specialized examinations of the bending performance in structural elements employing 600 MPa high-strength steel.

The seismic ductility of reinforced concrete (RC) columns is determined by a complex interaction of mechanical parameters, where the axial compression ratio, concrete compressive strength, and longitudinal reinforcement yield strength emerge as the primary governing factors. The stirrup strength and volumetric reinforcement ratio significantly influence the overall deformation capacity under cyclic loading. Furthermore, the confinement effect and ductility enhancement of RC columns can be effectively achieved through fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) wrapping, particularly in the seismic retrofitting of existing structures [

11,

12].

Extensive experimental studies have been conducted to assess the seismic performance of concrete columns with different stirrup configurations [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. The research findings consistently indicate that columns reinforced with high-strength stirrups maintain satisfactory ductility and deformation capacity even under high axial compression ratios. However, it should be noted that most existing studies have focused on conventional reinforcement types, including hot-rolled plain bars, prestressed concrete (PC) steel bars, and cold-rolled ribbed bars with yield strengths up to 600 MPa.

High-strength stirrups offer substantial advantages in bridge engineering, building structures, and specialized environmental projects due to their superior mechanical properties and exceptional durability [

25,

26,

27]. These components are particularly well-suited for applications requiring high-intensity seismic resistance, large-span lightweight construction, and enhanced durability, as they significantly improve structural seismic performance, reduce self-weight, and prolong service life. However, their implementation faces challenges, including higher costs (approximately 2–3 times those of conventional stirrups), complex construction processes requiring specialized equipment and stringent curing conditions, and the need for further refinement in design standards. With technological advancements and optimization of standard systems, the applicability and cost-effectiveness of these materials in engineering practice are expected to improve significantly in the future. This limitation highlights the urgent need for further research into the seismic response mechanisms of concrete columns reinforced with ultra-high-strength stirrups with yield strengths exceeding 600 MPa.

The widespread adoption of high-strength steel reinforcement in China has created a growing demand for 600 MPa grade and higher-strength stirrups in engineering practice [

25,

26,

27]. To address this, this study presents a novel experimental investigation into the seismic behavior of six concrete columns, distinctly designed to compare the seismic performance of concrete reinforced column HRB400 stirrups with 630 MPa high-strength stirrups. Three columns were reinforced with HRB400 stirrups, while the remaining three incorporated 630 MPa high-strength stirrups. All specimens were fabricated with precisely controlled variations in key parameters, including concrete compressive strength, stirrup yield strength, and volumetric stirrup ratio. Low-cycle reversed loading tests were conducted to assess the seismic response of the specimens, focusing on four critical performance indicators: (1) failure modes, (2) hysteretic loop characteristics, (3) displacement ductility coefficients, and (4) energy dissipation capacity.

2. Experimental Processes

2.1. Specimen Design

Six test specimens (designated Z1 through Z6) were fabricated for experimental evaluation. As illustrated in

Figure 1, which details the specimen dimensions and fabrication procedure, HRB400 reinforcement is denoted by ‘C’ while 630 MPa high-strength steel is marked as ‘D’. All specimens maintained consistent geometric and loading parameters, including a shear span-to-depth ratio of 4.93 and an axial compression ratio of 0.25. The longitudinal reinforcement consisted of four D14 bars, resulting in a uniform reinforcement ratio of 0.985% across all specimens.

Material specifications are summarized in

Table 1, which details the two concrete grades employed—C45 and C60—along with their respective stirrup configurations. Under standard curing conditions, the measured cube compressive strengths reached 52.9 MPa for C45 and 66.9 MPa for C60. The experimental program incorporated two grades of reinforcement: conventional HRB400 and 630 MPa high-strength steel. The base of each specimen was constructed as a rectangular prism with dimensions of 1350 mm × 550 mm × 700 mm and a concrete cover thickness of 50 mm, with all reinforcing bars consisting of HRB400 grade (designated as Class C) steel. The upper concrete columns featured a square cross-section of 250 mm × 250 mm, reinforced symmetrically with a cover thickness of 20 mm. It should be noted that the cover thickness typically refers to the shortest perpendicular distance from the outer surface of longitudinal reinforcement to the concrete face. The mechanical properties of the HRB400 steel bars were as follows: average elongation 25.8%, lower yield strength (

fy) 453.44 MPa, elastic modulus (

Es) 190.34 GPa, and ultimate strength (

fu) 614.76 MPa. Correspondingly, the 630 MPa high-strength steel bars exhibited an average elongation of 21.7%,

fy of 738.34 MPa,

Es of 219.08 GPa, and

fu of 928.50 MPa.

Equal strength replacement is a design method that maintains the shear resistance per unit length of stirrups (

Asv fyv/sv) unchanged, where

Asv is the cross-sectional area of the stirrups,

fyv is the yield strength, and

sv is the spacing. The replacement principle is based on the equilibrium of stirrup resistance, which states that:

Calculation Example (Based on Parameters in

Table 1):

For the transition from Z1 → Z2 (C45 concrete):

Z1: HRB400 stirrups: fyv1 = 400 MPa, sv1 = 100 mm, Asv = 50.3 mm2.

Z2: HRB630 stirrups: To achieve equal resistance with

fyv2 = 630 MPa and the same

Asv, the required spacing

sv2 is calculated as

The actual spacing for Z2 was set to 150 mm (rounded for practicality). Similarly, the

sv values for other specimens (Z3–Z6) were derived and are listed in

Table 1.

2.2. Experimental Setup and Loading Protocol

The quasi-static testing system comprised an MTS 1000 kN hydraulic actuator for applying lateral loads and a 1000 kN capacity hydraulic jack for maintaining constant axial compression on the column specimens. Structural response measurements were recorded using a DH3816 static strain acquisition system. The complete test setup configuration is presented in

Figure 2. To ensure data accuracy, the specimen installation followed a standardized protocol established in prior research [

8], with modifications tailored for this study on concrete columns:

Positioning and Initial Alignment: The specimen was hoisted near the MTS actuator and roughly aligned using the vertical jack as a reference.

Pressure Beam Fixation: The pressure beams on both sides were lowered, and the compression beam was securely fastened to the specimen base with specialized nuts.

MTS Actuator Attachment: The MTS actuator position was adjusted, and a steel plate was fixed to the column top using four screws to ensure force transmission through the centerline.

Final Alignment and Preparation: The column top position was fine-tuned via a sliding trolley to align with the centerline, followed by gradual lowering of the vertical jack to complete pre-load calibration.

Lateral Force and Displacement Monitoring: The MTS actuator automatically recorded lateral force and displacement data during loading.

Axial Force Measurement: A pressure sensor placed on the column top monitored axial load.

Base Displacement Tracking: A dial indicator installed at the specimen base measured base displacement for plastic hinge analysis.

Loading Control and Error Mitigation: Calibration ensured the lateral force acted on the specimen plane, minimizing out-of-plane deformation. During loading, minor angle changes in the MTS actuator (typically <0.5°) due to plastic hinge formation at the column base had a negligible impact on force measurement accuracy [

8].

Prior to testing, the skeleton curve of each specimen under monotonic loading was simulated using the finite element program OpenSees based on the measured material mechanical properties. The yield load (

Pyc) and yield displacement (Δ

yc) were then determined using the energy equivalent method [

8]. A displacement-controlled loading protocol was adopted for the lateral force application, with loading displacement amplitudes set at 0.4Δ

yc, 0.8Δ

yc, Δ

yc, 1.5Δ

yc, 2.0Δ

yc, 2.5Δ

yc, and so forth. The first three loading stages were cycled once, while subsequent stages were cycled three times, with each stage’s displacement amplitude increment being Δ

yc. The test was terminated when a 15% degradation in peak load capacity was observed during any loading cycle, indicating significant specimen strength deterioration. The loading protocol applied in experimental tests is illustrated in

Figure 3.

2.3. Crack Propagation and Failure Mechanisms

Figure 4 depicts the ultimate failure patterns observed in all six column specimens, which consistently exhibited characteristic flexural failure mechanisms. The failure progression across all specimens generally followed these sequential stages: (1) initial formation and oblique propagation of horizontal cracks intersecting at the column base on the tension side; (2) progressive spalling and peeling of the concrete cover adjacent to the principal cracks at the left and right column base regions; (3) development of vertical cracks along the edges of the column bottom; and (4) severe crushing of the plastic hinge zone, accompanied by a drop in lateral load to 85% of the peak value.

In conventional reinforced concrete columns, after attaining the maximum lateral load capacity, a limited number of vertical cracks appeared near the edges and corners. The extent of concrete cover spalling increased progressively with cyclic loading on both sides. As damage accumulated, the vertical cracks at the column base propagated upward, with localized crushing occurring at certain edges and corners.

The high-strength concrete column specimens demonstrated several distinctive failure characteristics: (1) significantly greater penetration depth of primary cracks; (2) more severe damage concentration within the plastic hinge region; (3) increased failure height of the concrete cover; (4) development of pronounced vertical splitting cracks prior to final failure, causing noticeable bulging and subsequent crushing of the concrete cover; and (5) pronounced bending deformation of longitudinal reinforcement bars at the column base, which collectively underscores the inherent brittleness of high-strength concrete under seismic loading conditions.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Hysteresis Behavior and Normalized Skeleton Curves Analysis

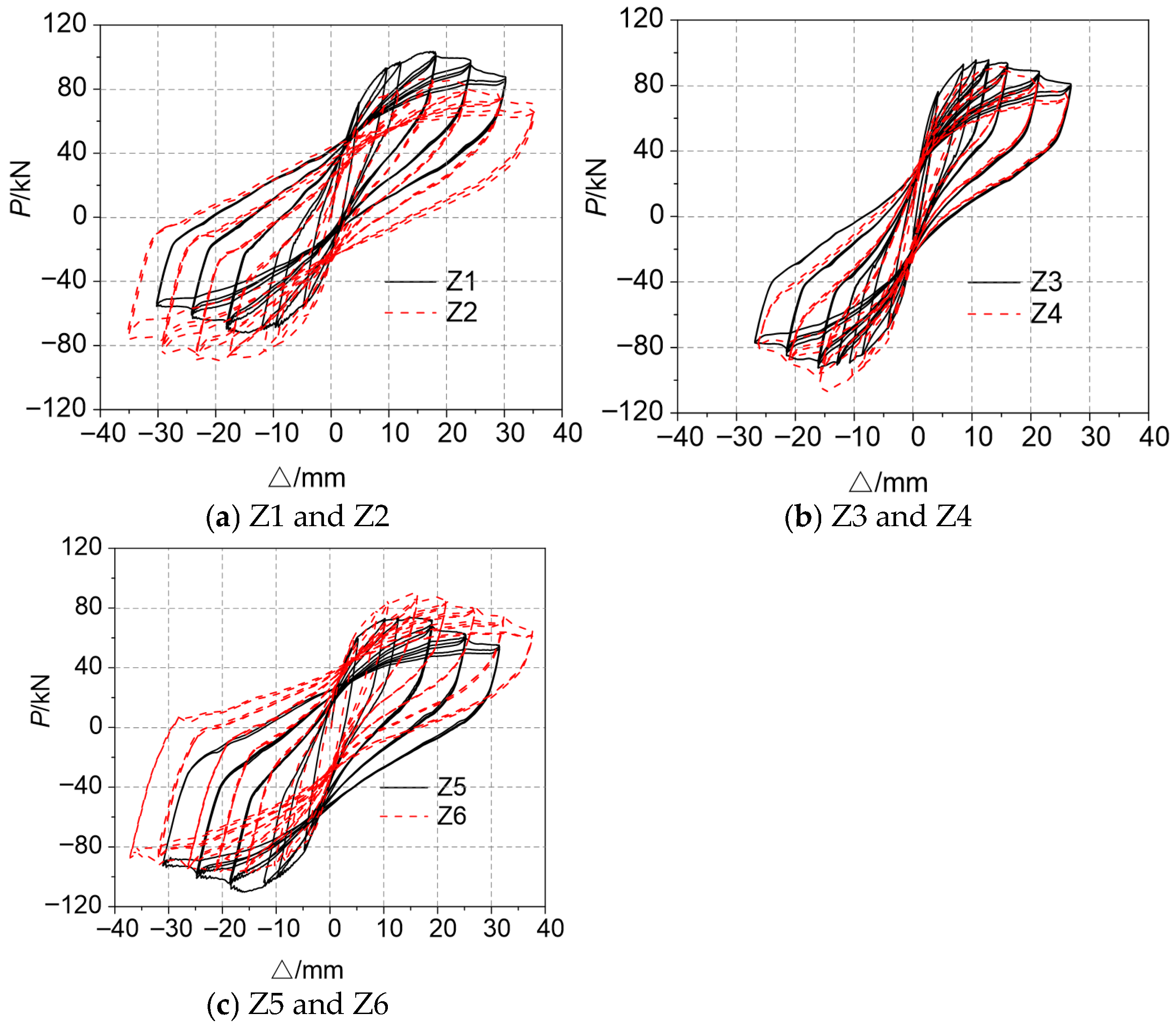

Figure 5 presents a comparative analysis of the hysteretic responses for all test specimens. The hysteretic curves of the six specimens generally exhibit an arched configuration. Specifically, specimens Z1 and Z2, fabricated with C45 concrete, display relatively full and stable hysteretic loops. In contrast, specimens Z3 and Z4, constructed with C60 concrete, demonstrate a more pronounced “pinching effect” in their hysteretic behavior. Notably, even when utilizing high-strength concrete (Z5 and Z6), the corresponding hysteretic curves maintain desirable fullness. Most notably, before and after implementing the equal-strength substitution of stirrups (i.e., replacing HRB400 steel bars with 630 MPa high-strength steel bars), the fundamental hysteretic characteristics of specimens within each comparative group remain largely consistent, without significant alterations in loop morphology or energy dissipation characteristics.

The skeleton curves in

Figure 6 were derived using the peak-envelope method. The load and displacement at each point of the skeleton curve were normalized by dividing them by the specimen’s yield load (

Py) and yield displacement (Δ

y), respectively, to obtain the dimensionless normalized skeleton curve (i.e., the

P/

Py-Δ/Δ

y curve).

Before and after the equivalent strength replacement of stirrups, the normalized skeleton curves of the ordinary concrete specimens (Z1 and Z2) exhibited relatively similar trends. For the high-strength concrete specimens (Z3 and Z4), the trends of their normalized skeleton curves were similar before reaching the peak point; however, the bearing capacity of the descending section for the high-strength stirrup specimen (Z4) decreased significantly. In contrast, the trends of the normalized skeleton curves for specimens Z5 and Z6 remained essentially the same before and after the peak, with the curves almost coinciding. Additionally, specimen Z6 demonstrated a distinct secondary strengthening point at approximately 1.0Δy, and its descending section exhibited a slower rate of degradation.

3.2. Bearing Capacity and Displacement Ductility Coefficient

Based on the skeleton curves obtained under reversed cyclic loading conditions, key bearing capacity parameters—including the yield load

Fy), peak load (

FP), ultimate load (

Fμ)—were determined, along with the displacement ductility coefficient

μu, as defined by Equation (3):

where Δ

u represents the ultimate displacement and Δ

y denotes the yield displacement. The corresponding values are provided in

Table 2.

All specimens exhibited ductility coefficients exceeding 3.0, with an average value of 4.29, confirming their excellent ductility and collapse resistance. After implementing the equal strength substitution, the following trends were observed under varying stirrup ratios.

Under low stirrup ratio conditions, specimens Z2 and Z4 showed increases in yield displacement by 17–18%, with maximum displacements increasing by 24.73% and 14.66%, respectively. However, the variations in ultimate displacement differed significantly between specimen types; while the ultimate displacement of normal concrete specimen Z2 increased by 21.76%, the ultimate displacement of high-strength concrete specimen Z4 decreased by 15.43% compared to specimen Z3, leading to a reduction in displacement ductility coefficient from 4.44 to 3.15 (29.05% decrease). This performance degradation under low stirrup ratios primarily stems from insufficient confinement efficiency, resulting in premature concrete crushing and accelerated strength degradation.

In contrast, under high stirrup ratio conditions, specimen Z6 demonstrated an 11.58% increase in yield displacement, a 9.30% increase in maximum displacement, and a 29.78% increase in ultimate displacement. Consequently, the displacement ductility coefficient increased from 4.62 to 5.48 (18.61% improvement). The superior performance at higher stirrup ratios can be attributed to enhanced confinement mechanisms, where denser stirrup arrangements provide more effective lateral restraint to the core concrete, thereby delaying the spalling process and maintaining load-carrying capacity at larger displacements.

Comparative analysis across concrete grades further elucidates this trend: for C45 concrete specimens Z1 and Z2, displacement ductility exhibited only a marginal increase of 3.02% after stirrup substitution. However, for high-strength C60 concrete specimens Z3 and Z4 with low stirrup ratios, a significant 29.05% reduction in ductility was observed following equal strength substitution. Regarding Z5 and Z6 specimens with higher stirrup ratios, although the spacing of high-strength stirrups increased following substitution, the confinement efficiency remained largely uncompromised, with ductility parameters showing consistent improvement with increasing stirrup ratio, particularly in high-strength concrete systems where the inherent brittleness necessitates adequate confinement for optimal performance.

The numerical model was developed following the computational framework established in our previous research [

8], ensuring methodological consistency throughout the analysis. As documented in

Table 2, the computed yield displacements (Δ

yc) demonstrate consistent alignment with experimental values (Δ

y), with relative errors systematically maintained below the 10% threshold. These observed discrepancies principally originate from two methodological considerations: (1) model idealization—the constitutive models implemented in OpenSees incorporate necessary simplifications for numerical stability, whereas actual concrete exhibits complex micro-defects and material inhomogeneity; (2) boundary condition idealization—the numerical representation simplifies certain connection details that are inherently present in experimental specimens.

3.3. Energy Consumption Performance

The standard cumulative hysteretic energy dissipation coefficient

EN (see Equation (4)) and the equivalent viscous damping coefficient

ξeq (see Equation (5)) serve as the primary indices for evaluating the energy dissipation capacity of structural systems [

8].

where

EN.m represents the cumulative hysteretic energy dissipation coefficient of the member at the end of the

m-th loading cycle;

Py and Δ

y denote the yield-bearing capacity and yield displacement, respectively;

Si corresponds to the area enclosed by the

i-th hysteresis loop, as illustrated in

Figure 7.

ξeq.i refers to the equivalent viscous damping coefficient for the

i-th loading amplitude. When multiple cycles occur at a given loading amplitude, the average value of the equivalent viscous damping coefficient across all cycles is adopted.

SΔOAB and

SΔOCD represent the areas of triangles OAB and OCD in the figure, respectively.

Figure 8 illustrates the relationship between the cumulative hysteretic energy dissipation coefficient (

EN) and displacement ductility. During the initial displacement loading stage, parameters including concrete strength, stirrup ratio, and stirrup type exhibited minimal influence on the specimens’ cumulative energy dissipation. Although specimens with HRB400 stirrups demonstrate a slightly higher cumulative hysteretic energy dissipation coefficient than those with 630 MPa high-strength stirrups, the difference remains negligible.

As displacement loading progressed to middle and advanced stages, discernible differences emerged in the cumulative energy dissipation of specimens incorporating different stirrup types. Under conditions of low stirrup ratios, substituting ordinary HRB400 stirrups with 630 MPa high-strength stirrups enhances the cumulative energy dissipation capacity of specimens at identical displacement ductility levels. This improvement, however, exhibits a correlation with concrete grade; normal concrete specimens achieved greater enhancement than their high-strength concrete counterparts.

Conversely, with high stirrup ratios—even when concrete strength was elevated—specimens utilizing high-strength stirrups exhibited significantly superior cumulative energy dissipation performance compared to those with ordinary stirrups, with the enhancement growing progressively more pronounced. Following equal strength substitution of stirrups, specimens reinforced with high-strength stirrups demonstrate improved ductility, manifested by an increased number of hysteresis cycles before failure and a 46.09% increase in total cumulative energy dissipation.

Figure 9 illustrates the variation in the equivalent viscous damping coefficient (

ξeq) with increasing displacement ductility. When the stirrup ratio is small, equal strength substitution of stirrups significantly influences the inflection point of the hysteretic energy dissipation performance; when 630 MPa high-strength steel bars replace HRB400 steel bars, the displacement corresponding to the rapid increase in the equivalent viscous damping coefficient advances from approximately 2.5Δ

y to about 1.5Δ

y. The energy dissipation capacity per hysteresis loop varies with displacement ductility. When the displacement is less than 2.5Δ

y, the specimens with high-strength stirrups demonstrate a lower energy dissipation capacity per loop compared to those with ordinary stirrups at identical displacement ductility. Conversely, when the displacement exceeds 2.5Δ

y, the single-loop energy dissipation capacity of specimens with high-strength stirrups exceeds that of specimens with ordinary stirrups under the same ductility conditions. This behavioral pattern is consistently observed in both normal concrete and high-strength concrete specimens.

Under high stirrup ratio conditions, equal strength substitution of stirrups exhibits negligible influence on the trend of equivalent viscous damping coefficient curves. When displacement remains below 2.0Δy, the single-loop energy dissipation capacity exhibits minor fluctuations within a limited range. However, when displacement exceeds 2.0Δy, a rapid enhancement in energy dissipation capacity per hysteresis loop occurs. Although the trends remain similar, the absolute energy dissipation capacity per hysteresis loop for specimens with high-strength stirrups differs from those with ordinary stirrups at equivalent displacement ductility levels.

3.4. Stiffness and Strength Degradation

As the loading displacement amplitude increases, significant damage occurs in both concrete and steel reinforcement, resulting in material degradation and consequent reductions in member strength and stiffness. The strength degradation coefficient

λ (see Equation (6)) quantifies the degradation per cycle at a given amplitude, while the loop stiffness

K (see Equation (7)) represents the overall stiffness across all cycles at the same amplitude [

8].

where

λij denotes the strength degradation coefficient for the

i-th cycle under the

j-level displacement amplitude. The final

λij value represents the average of the coefficients calculated in the positive and negative loading directions. In this expression,

Pij and △

ij refer to the peak load and the corresponding displacement amplitude for that specific cycle, respectively, and

n indicates the total number of loading cycles at the

j-level displacement amplitude. Additionally,

Kj represents the loop stiffness under the

j-level displacement amplitude, which is computed separately for both the forward and reverse loading directions.

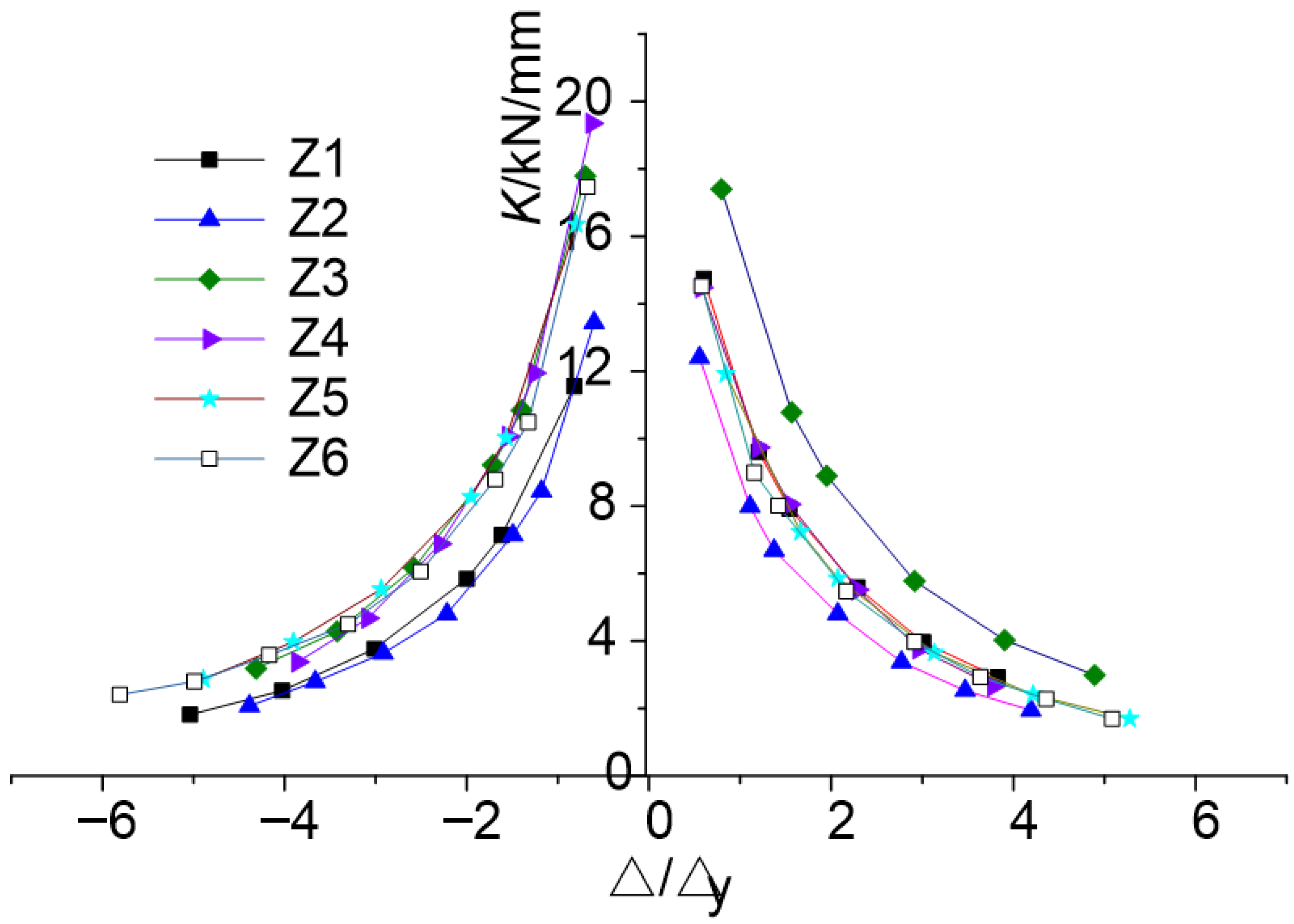

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 present the degradation curves of loop stiffness (

K) and average loop stiffness for the three specimen groups as functions of displacement ductility. The results indicate that both the stirrup ratio and concrete strength have minimal influence on the stiffness degradation trends. With the exception of specimen Z4, the stiffness degradation curves of all other specimens exhibit relatively symmetrical behavior in both loading directions with respect to the origin. Notably, specimens that underwent equal strength substitution of stirrups demonstrate a certain degree of stiffness reduction. While the degradation trends of the average loop stiffness curves are consistent across all three specimen groups, the absolute stiffness values differ. Specifically, under identical displacement ductility conditions, specimens with high-strength stirrups exhibit slightly lower average loop stiffness compared with those with ordinary stirrups.

Table 3 presents the strength degradation coefficients for both specimen groups across varying loading displacement amplitudes. The strength degradation coefficient for each specimen exceeds 0.95. At a given displacement amplitude, the specimen’s strength exhibits only minor degradation with increasing cycle count, and the equivalent strength substitution of stirrups has a negligible effect on the strength degradation coefficient. Regarding bearing capacity attenuation, regardless of variations in stirrup ratio or concrete strength, replacing HRB400 steel bars with 630 MPa high-strength steel bars as stirrups does not significantly alter the fundamental bearing capacity.

3.5. Cumulative Damage

Structural cumulative damage serves as a comprehensive indicator of performance, encompassing strength, stiffness, energy dissipation, deformation, and ductility. The damage degree can be quantified using a damage index

D (see Equation (7)), for which multiple calculation models have been proposed, including deformation-based [

28,

29], energy-based [

30], low-cycle fatigue-based [

31,

32], and hybrid approaches [

33].

Among these, the Park–Ang model [

33], which integrates both deformation and energy, has been widely adopted. However, this model exhibits limitations in damage index calculation [

34], such as yielding

D > 0 during the elastic stage and

D > 1 near failure—results that contradict physical reality. To mitigate these issues, Kunnath [

35] introduced member yield deformation into the deformation term of the Park–Ang model, proposing the modified Kunnath model:

where

δm—maximum deformation under current loading path;

δy—yield deformation;

δu—ultimate deformation under monotonic loading.

Experimental results [

36] demonstrate that the ultimate deformation under repeated loading is 0.62 times that under monotonic loading. Consequently, the monotonic ultimate deformation (

δu) is derived by dividing the pseudo-static test result by 0.62 for damage index computation. Key parameters include the following: (1)

Eh, the cumulative hysteretic energy; (2)

Fy, the yield shear force; and (3)

β, the energy dissipation factor (set to 0.05 [

33] in the Park–Ang model).

Figure 12 illustrates the cumulative damage index curve.

Before member yield, the damage index of the specimen develops gradually, but after yield, its rate of growth accelerates significantly. This indicates that damage accumulation in the early loading stage is minimal, while it intensifies in the plastic stage—particularly in the later phases of loading, where the damage index exhibits a marked increase under identical displacement conditions.

When 630 MPa high-strength steel bars are used to replace HRB400 steel bars as stirrups, the damage index behavior varies with stirrup ratio and concrete strength. For low stirrup ratios and high concrete strength, the low restraint efficiency results in specimen Z4 having a smaller damage index than Z3 in the early loading stage. However, in the later stage, Z4’s damage index surpasses that of Z3. Conversely, for low concrete strength, Z2’s damage index remains smaller than Z1. When the stirrup ratio is high, regardless of concrete strength, specimen Z6 demonstrates a significantly smaller damage index than Z5. These observations confirm that 630 MPa high-strength stirrups can effectively ensure the confining effect of core concrete.

Results further demonstrate that replacing HRB400 steel bars with 630 MPa high-strength stirrups, while maintaining a high stirrup ratio, enhances the restraint of core concrete and slows down damage development in members. However, for low stirrup ratios, the confining effect of 630 MPa high-strength stirrups on high-strength concrete members is insufficient, leading to rapid damage progression.

4. Analysis of the Confinement Effect of 630 MPa High-Strength Stirrup on Core Concrete

The stirrup exerts a confining effect on the core concrete, thereby increasing its peak strength (fcc) and the peak strain (εcc) at the peak strength. This enhancement directly improves the strength and ductility of reinforced concrete members.

In this study, strain gauges were embedded to measure longitudinal reinforcement and stirrup strains; however, most test data were unavailable due to sensor failures or data acquisition limitations. Consequently, theoretical calculations were employed to analyze the restraint effect of 630 MPa super-high-strength stirrups on core concrete, elucidating the seismic mechanism of such members.

The strength and strain of core concrete serve as critical indicators of stirrup restraint. The peak strength (

fcc) and peak strain (

εcc) of confined concrete can be derived by multiplying the peak strength (

fc0) and peak strain (

εc0) of unconfined concrete by an improvement factor, which is a function of the effective lateral restraint stress (

fle) of stirrups when core concrete reaches its peak strength. The calculation formula for

fle is provided in Equation (9) [

37].

where

fhcc is the stirrup stress when the peak stress of confined concrete is reached;

s is the spacing of stirrup centerlines;

Ashx and

Ashy are the total area of stirrups in

x and

y directions, respectively;

cx and

cy are the centerline spacing of the outermost stirrups in

x and

y directions, respectively; and

Ke is the effective restraint coefficient. The

Ke of rectangular columns can be calculated according to Equation (10).

where

wi is the net spacing of adjacent longitudinal bars;

s′ is the net spacing of stirrups;

ρc is the ratio of longitudinal reinforcement area to concrete area in the core area.

fhcc can be calculated iteratively according to the stirrup constitutive relation and the axial and transverse strain relationship of confined concrete.

This study employs a widely applicable method to sequentially compute

fhcc, and then obtain

fle,

fcc, and

εcc [

8]:

(1) Initialization: Assume fhcc = fyv.

(2) Calculate fle using Equation (9).

(3) Determine εcc.

Substitute

fle into the empirical fitting equation (Equation (11) [

38]) to obtain

εcc.(4) Calculate ε3,p.

From the triaxial stress–strain relationship (Equation (12) [

39]), derive the transverse strain

ε3,p corresponding to

εcc.(5) Update fhcc.

Assume stirrup strain εsh = ε3,p, then obtain fhcc from the stirrup constitutive model.

(6) Convergence Check:

If fhcc < fyv, and fhcc, update fhcc and repeat Steps 2–5;

Iterate until fle converges (typically within 3–5 cycles).

(7) Final Output: Obtain

εcc and

fcc using Equations (11) and (13).

Table 4 presents the mechanical parameters of core concrete for each specimen. Notably, neither the HRB400 nor the 630 MPa high-strength steel stirrups reached their yield strength under any tested conditions, preventing the full utilization of their strength potential. When HRB400 steel bars were employed as stirrups, the peak stresses recorded were 200.92 MPa, 205.83 MPa, and 369.43 MPa, respectively. In contrast, the 630 MPa high-strength steel stirrups exhibited peak stresses of 129.19 MPa, 137.04 MPa, and 171.68 MPa, respectively. This suggests that the HRB400 steel bars provided superior strength contributions under the tested loading mode, indicating that the advantage of high-strength stirrups was not fully utilized. Even in the non-yielding case, high-strength stirrups still provide more effective confinement at high stirrup ratios (Z6 vs. Z5), demonstrating that the difference in strength grade plays a limited role in the confinement mechanism. Whether steel bars are superior as stirrups cannot be determined by considering the yield strength alone as a single parameter.

For the three specimen groups (Z1/Z2, Z3/Z4, Z5/Z6), after equal-strength substitution of stirrups (replacing HRB400 with 630 MPa high-strength steel), the peak stress of core concrete in Z2, Z4, and Z6 was 5.26%, 5.31%, and 10.24% lower than that in Z1, Z3, and Z5, respectively. Similarly, the peak strain of Z2, Z4, and Z6 was 17.29%, 14.96%, and 41.56% lower than that of their counterparts. These results highlight that the stirrup ratio (ρsv) had a more pronounced influence on enhancing strength and ductility than the stirrup strength (fyv) after equal-strength substitution.

When the stirrup ratio was small, Z2 (with lower concrete strength) exhibited a higher increase in peak stress and peak strain compared to Z4 (with higher concrete strength). The effective index of Z2 was 1.2 times that of Z4, indicating that 630 MPa high-strength steel stirrups could achieve better binding effects on lower-strength concrete at small stirrup ratios.

In contrast, when the stirrup ratio was large, Z6 demonstrated a 1.14-fold increase in strength and a 1.35-fold increase in strain compared to its reference group. The effective restraint index of Z6 was 0.91%, which was 3.8 times and 4.6 times higher than that of Z2 and Z4, respectively. This confirms that at large stirrup ratios, the 630 MPa high-strength steel stirrups provided superior restraint, effectively slowing down the damage development of core concrete.

5. Conclusions

To meet the engineering demand for high-performance stirrups compatible with high-strength steel reinforcement in practical applications, this study investigates the seismic behavior and damage mechanism of concrete columns reinforced with 630 MPa high-strength steel stirrups, using columns with HRB400 steel stirrups as references. Guided by key variables—including concrete strength, stirrup strength, and stirrup spacing ratio—low-cycle reversed loading tests were carried out. Additionally, the confinement effect of 630 MPa high-strength steel stirrups on core concrete was systematically analyzed. These findings can provide technical support for the application of high-strength stirrups in seismic-resistant components (e.g., bridge piers, high-rise building joints) while balancing performance enhancement and construction efficiency. The main research conclusions are summarized as follows.

(1) The use of 630 MPa high-strength steel bars as stirrups (i.e., equal-strength substitution of reinforcement) in high-strength concrete columns introduces notable changes in seismic performance, primarily due to variations in stirrup restraint efficiency. When the stirrup ratio is low, equal-strength substitution is achieved by increasing stirrup spacing, which inevitably reduces the restraint effect to some extent. However, when the stirrup ratio is high, the restraint effect remains unaffected by the substitution. Moreover, specimens with high-strength stirrups exhibit increased yield displacement, maximum displacement, ultimate displacement, and displacement ductility, demonstrating generally superior seismic performance.

(2) During the initial loading stage, the equivalent-strength substitution of stirrups has minimal impact on the cumulative energy consumption of specimens, regardless of the stirrup ratio. In the middle and later stages of displacement loading, when the stirrup ratio is low, the cumulative energy consumption capacity of specimens improves under the same displacement ductility. When the stirrup ratio is high, however, the cumulative energy dissipation performance of specimens with high-strength stirrups significantly surpasses that of specimens with ordinary stirrups under identical displacement ductility, with the performance gap gradually widening as loading progresses.

(3) When 630 MPa high-strength steel bars are used as stirrups, their restraint effectiveness is inferior to that of low-strength concrete columns at low stirrup ratios. At high stirrup ratios, regardless of concrete strength, high-strength stirrups provide better confinement and effectively slow down member damage development.

(4) Current research on the seismic performance of 630 MPa high-strength steel stirrups in high-strength concrete columns remains limited, particularly regarding their long-term durability under cyclic loading. Future studies should focus on optimizing stirrup configurations to maximize their benefits while ensuring cost-effectiveness and constructability.