Regulatory Gap Versus Performance Reality: Thermal Assessment of a Social Housing Module in the Peruvian Andes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Case Study

2.2. Building Envelope Performance Assessment (EM.110-2014 vs. 2022)

2.2.1. Thermal Transmittance (U-Value) Evaluation

- Heterogeneous layers: the 2022 draft requires differentiated calculation accounting for both horizontal and vertical heat flows; the 2014 version uses a simplified approach.

- Thermal bridges: the 2022 draft eliminates the exclusion of surface resistances (e.g., beams, columns) and mandates specific calculation for openings instead of tabulated values.

- Floor assembly: the 2014 standard calculates U based on material layers; the 2022 draft assigns a predetermined U-value depending on the type of perimeter insulation.

2.2.2. Surface Condensation Risk Verification

2.3. Adaptive Thermal Comfort Assessment Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Thermal Transmittance (U-Value)

3.2. Surface Condensation Risk

3.2.1. Calculation of Dew Point Temperature (Tr)

3.2.2. Calculation of Internal Surface Temperature (Tsi)

- EM. 110-2014: The internal surface resistance (Rsi) was set at 0.11 m2K/W for the wall and 0.09 m2K/W for the roof and floor.

- EM. 110-2022: The Rsi values were obtained from the draft standard, establishing 0.13 m2K/W for the wall, 0.10 m2K/W for the roof, and 0.17 m2K/W for the floor.

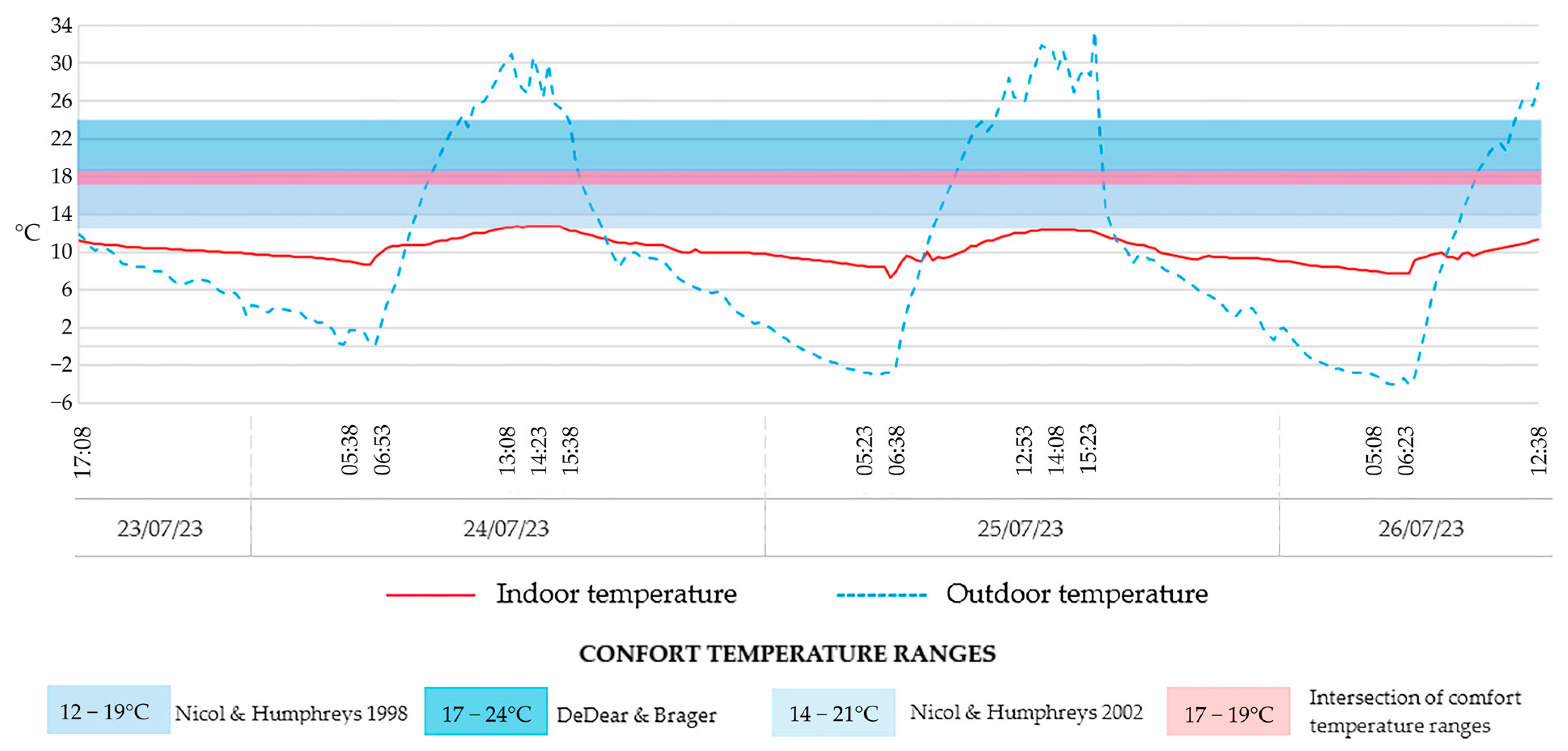

3.3. Adaptive Thermal Comfort Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Systemic Non-Compliance: The building envelope exceeds U-value limits of EM.110 (2014 and 2022 draft), with the roof exhibiting the highest thermal transmittance.

- Normative Contradiction: The 2022 draft’s stringent floor U-value risks decoupling slabs from beneficial ground thermal mass, countering regional bioclimatic principles.

- Misaligned Comfort Targets: Indoor conditions fall below official standards but match those in adapted Andean homes, underscoring the need for localized adaptive comfort models.

- 4.

- Prioritize roof retrofitting using high-performance, low-cost local materials (e.g., totora reed mats, straw-clay composites).

- 5.

- Optimize floor design with insulated perimeters while retaining partial ground contact to leverage thermal inertia.

- 6.

- Formalize high-Andean adaptive comfort ranges in national policy, grounded in field data on acclimatized populations.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UNSAAC | Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco |

| MVCS | Ministerio de Vivienda, Construcción y Saneamiento |

| SENAMHI | Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología |

Appendix A

| Envelope | Constructive Element | Thickness (m) |

|---|---|---|

| Exterior walls | Foundation sill | - |

| Cement-Sand Mortar | 0.02 | |

| Plain Concrete Mix | 0.4 | |

| Gypsum Plaster | 0.01 | |

| Baseboard | - | |

| Cement-Sand Mortar 1:3 | 0.02 | |

| Adobe | 0.4 | |

| Gypsum Plaster | 0.01 | |

| Wall | - | |

| Gypsum Plaster | 0.01 | |

| Adobe | 0.4 | |

| Gypsum Plaster | 0.01 | |

| Beams | - | |

| Gypsum Plaster | 0.01 | |

| Collar Beam | 0.1016 | |

| Gypsum Plaster | 0.01 | |

| Exterior Door | Phenolic Plywood | 0.0065 |

| Unventilated Air Cavity | 0.03 | |

| Phenolic Plywood (3 Layers) | 0.0065 | |

| Windows | Aluminum Tube (frame) | 0.0254 |

| Clear Single Glass | 0.06 | |

| Windows shutter | Lightweight Wood (frame) | 0.054 |

| Plywood (exterior layer) | 0.004 | |

| Unventilated Air Cavity | 0.03 | |

| Plywood | 0.004 | |

| Roof | 11-Channel Galvanized Corrugated Sheet | 0.0003 |

| Expanded Polystyrene | 0.05 | |

| Skylight (Roof) | Transparent Corrugated Polycarbonate | 0.001 |

| Ceiling (opaque part) | Vinyl Tile | 0.01 |

| Skylight-Ceiling | Aluminum Tube (frame) | 0.0254 |

| Cellular Polycarbonate | 0.006 | |

| Floor | Polished Cement Floor with Steel Reinforcement | 0.08 |

| Stone Bed | 0.1016 |

References

- Fuller, R.J.; Zahnd, A.; Thakuri, S. Improving comfort levels in a traditional high altitude Nepali house. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Luo, Q.; Yan, F.; Lei, Y.; Lu, Y.; Chen, H.; Yang, Y.; Feng, H.; Zhou, M.; Ding, H.; et al. Evaluating the Microclimatic Performance of Elevated Open Spaces for Outdoor Thermal Comfort in Cold Climate Zones. Buildings 2025, 15, 2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Cong, Y.; Yao, S.; Dai, C.; Li, Y. Research on the thermal comfort of the elderly in rural areas of cold climate, China. Adv. Build. Energy Res. 2022, 16, 612–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, I.; Niza, B.E.E. Development of thermal comfort models over the past years: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Ambient Energy 2022, 43, 8830–8846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE 55; ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55: Thermal Environmental Conditions For Human Occupancy. ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020.

- Huang, L.; Hamza, N.; Lan, B.; Zahi, D. Climate-responsive design of traditional dwellings in the cold-arid regions of Tibet and a field investigation of indoor environments in winter. Energy Build. 2016, 128, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, S.; Karki, B.A.; Gurung, P.G.K. Adaptive thermal comfort in the residential buildings of north east India—An effect of difference in elevation. Build. Simul. 2018, 11, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Xu, J.; Lu, Z.; Yan, J.; Li, F. A systematic review of indoor thermal environment of the vernacular dwelling climate responsiveness. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 53, 104514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijal, H.B. Thermal adaptation of buildings and people for energy saving in extreme cold climate of Nepal. Energy Build. 2021, 230, 110551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, S. Thermal comfort in high altitude Himalayan residential houses in Darjeeling, India—An adaptive approach. Indoor Built Environ. 2020, 29, 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, T.M.; Buch, S.H.; Banka, A.A. SVR-based comparison of thermal performance of traditional and contemporary masonry structures in Himalayan region. Energy Build. 2025, 347, 116192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziani, M. NORMAS IRAM SOBRE AISLAMIENTO TÉRMICO DE EDIFICIOS. Available online: https://m2db.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/normas-iram-2015.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo. REGLAMENTACION TERMICA MINVU ORDENANZA GENERAL DE URBANISMO Y CONSTRUCCIONES. 2006. Available online: https://www.minvu.gob.cl/nueva-reglamentacion-termica/ (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Reglamento Nacional de Edificaciones. Norma Em-110 Confort Térmico y Lumínico con Eficiencia Energética. Peru, 2014. Available online: https://www.construccion.org/normas/rne2012/rne2006.htm (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Franconi, E.; Troup, L.; Weimar, M.; Ye, Y.; Nambiar, C.; Lerond, J.; Hotchkiss, E.; Cox, J.; Ericson, S.; Wilson, E.; et al. Enhancing Resilience in Buildings Through Energy Efficiency; Pacific Northwest National Laboratory: Richland, WA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología del Peru. Aviso Meteorológico: Heladas y Friaje en la Sierra sur del Peru. Portal Web SENAMHI. Available online: https://www.senamhi.gob.pe/main.php?dp=cusco&p=estaciones (accessed on 26 October 2023).

- Iruri, C.; Domínguez, P.; Celis, F. Envelope improvements for thermal behavior of rural houses in the Colca Valley, Peru. Estoa 2023, 12, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia-Solis, E.; Arias, J.; Palm, B. Simple solutions for improving thermal comfort in huts in the highlands of Peru. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieser, M.; Rodriguez, S.; Onnis, S. Estrategias bioclimáticas para clima frío tropical de altura. Validación de prototipo en Orduña, Puno, Peru. Estoa 2021, 10, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, J.R.; Lefebvre, G.; Gómez, M.M. Study of the thermal comfort and the energy required to achieve it for housing modules in the environment of a high Andean rural area in Peru. Energy Build. 2023, 281, 112757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Programa Nacional de Vivienda Rural. Información Institucional. Plataforma Digital Única del Estado Peruano. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/pnvr/institucional (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Centro de Operaciones de Emergencia Nacional; Instituto Nacional de Defensa Civil. INFORME DE EMERGENCIA N° 988—2/7/2022/COEN—INDECI/23:40 HORAS (Informe N° 1). Peru, 2022. Available online: https://portal.indeci.gob.pe/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/INFORME-DE-EMERGENCIA-N%C2%BA-988-2JUL2022-BAJAS-TEMPERATURAS-EN-EL-DEPARTAMENTO-DE-CUSCO-1-2.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Programa Nacional de Vivienda Rural. Sumaq Wasi. Ministerio de Vivienda, Construcción y Saneamiento. Available online: https://sites.google.com/vivienda.gob.pe/sumaqwasi/proyectos-de-mejoramiento-de-vivienda-rural?authuser=0 (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Huamani, F.; Taipe, Y.; Ugarte, J. Análisis del Confort Térmico en las Viviendas ‘Sumaq Wasi’, Misquipata, Distrito de San Juan de Jarpa, Provincia Chupaca, Región Junín. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Continental, Huancayo, Peru, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Herencia, P.; Palomino, P. EVALUACIÓN COMPARATIVA DE LOS VALORES DE TRANSMITANCIAS TÉRMICAS DE LOS MÓDULOS SUMAQ WASI EN CCATCCA-QUISPICANCHI, SEGÚN LA NORMA EM.110. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Andina del Cusco, Cusco, Peru, 2023. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12557/5544 (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Pacha, F. Evaluación del Confort Térmico en las Viviendas Rurales Sumaq Wasi en los Centros Poblados de Pucri y Challamayo pata, Tiquillaca, Puno—2023. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional del Altiplano, Puno, Peru, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rabanal, J. Análisis del Desempeño Térmico y de la Percepción del Confort en los Módulos Habitacionales Sumaq Wasi del Centro poblado Chuna, Distrito de Chavín de Huántar. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Pontificia Católica del Peru, Lima, Peru, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Salas, V.M. ¿Etnodesarrollo asistido? Viviendas de comunidades campesinas frente al costo social neoliberal en los Andes peruanos. CONTEXTO. Rev. Fac. Arquit. Univ. Autónoma Nuevo León 2025, 19, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Programa Nacional de Vivienda Rural. Especificaciones Técnicas Adobe 25.09; Ministerio de Vivienda, Construcción y Saneamiento: Lima, Peru, 2020.

- ISO 7726; ISO 7726: Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment—Instruments for Measuring Physical Quantities. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 1998.

- Ministerio de Vivienda, Construcción y Saneamiento. Proyecto Norma Técnica EM.110, Envolvente Térmica del Reglamento Nacional de Edificaciones; Diario Oficial El Peruano: Lima, Peru, 2022; Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/vivienda/normas-legales/3302388-197-2022-vivienda/ (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- ISO 6946; ISO 6946: Building Components and Building Elements—Thermal Resistance and Thermal Transmittance—Calculation Method. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Dirección General de Salud Ambiental; Dirección Ejecutiva de Salud Ocupacional. Manual de Salud Ocupacional; PERUGRAF IMPRESORES: Lima, Peru, 2005. [Google Scholar]

| Peruvian Technical Standard EM.110 (2014) | Peruvian Technical Standard Project EM.110 (2022) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioclimatic zone | TTM a (w/m2k) | Bioclimatic zone | TTM a (w/m2k) | ||||||

| Wall | Roof | Floor | Wall | Roof | Floor (level or ventilated) | ||||

| 5 | High-Andean | 1.00 | 0.83 | 3.26 | 6 | Continental very cold | 1.9 | 0.8 | 1.2 |

| Date | Indoor Temperature (°C) | Hri 1 (%) | Outdoor Temperature (°C) | HRe 2 (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | Min | Max | Min | Max | Min | Max | Min | |

| 24 July 2023 | 12.7 | 8.7 | 39.0 | 25.6 | 19.4 | 0.2 | 49.2 | 8.9 |

| 25 July 2023 | 12.4 | 7.3 | 37.9 | 21.8 | 20.7 | −3.0 | 42.4 | 5.5 |

| 26 July 2023 | 11.3 | 7.7 | 34.2 | 20.4 | 20.6 | −4.0 | 43.0 | 7.2 |

| Average | 12.13 | 7.9 | 37.03 | 22.6 | 20.23 | −2.27 | 44.87 | 7.2 |

| Envelope Component | Tr (°C) a | EM.110-2014 | EM.110-2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tsi (°C) b | Tsi (°C) b | ||

| Wall | −6.70 | 6.71 | 5.14 |

| Roof | 6.43 | 5.94 | |

| Floor | 7.06 | 4.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Palomino-Olivera, E.; Ancco-Peralta, M.; Salas Velásquez, V.; Mejia-Solis, E.; Gudiel Rodriguez, E. Regulatory Gap Versus Performance Reality: Thermal Assessment of a Social Housing Module in the Peruvian Andes. Buildings 2025, 15, 4401. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244401

Palomino-Olivera E, Ancco-Peralta M, Salas Velásquez V, Mejia-Solis E, Gudiel Rodriguez E. Regulatory Gap Versus Performance Reality: Thermal Assessment of a Social Housing Module in the Peruvian Andes. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4401. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244401

Chicago/Turabian StylePalomino-Olivera, Emilio, Miriam Ancco-Peralta, Víctor Salas Velásquez, Enrique Mejia-Solis, and Edwin Gudiel Rodriguez. 2025. "Regulatory Gap Versus Performance Reality: Thermal Assessment of a Social Housing Module in the Peruvian Andes" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4401. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244401

APA StylePalomino-Olivera, E., Ancco-Peralta, M., Salas Velásquez, V., Mejia-Solis, E., & Gudiel Rodriguez, E. (2025). Regulatory Gap Versus Performance Reality: Thermal Assessment of a Social Housing Module in the Peruvian Andes. Buildings, 15(24), 4401. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244401