Study on Wind Load Distribution and Aerodynamic Characteristics of a Yawed Cylinder

Abstract

1. Introduction

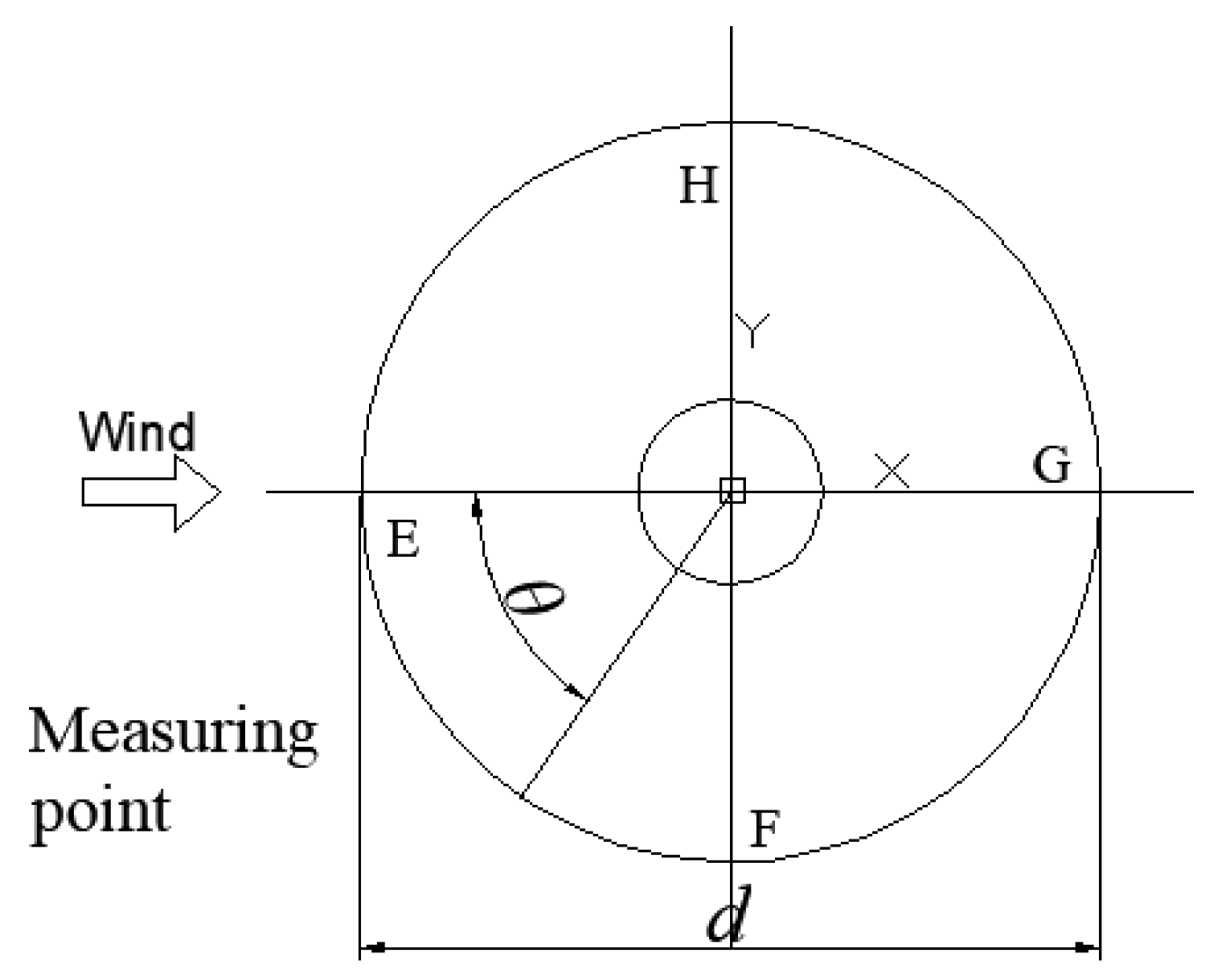

2. Test Overview

2.1. Test Model and Working Condition

2.2. Test Parameters

2.3. Symmetry of the Oncoming Flow

3. Analysis of Experimental Results

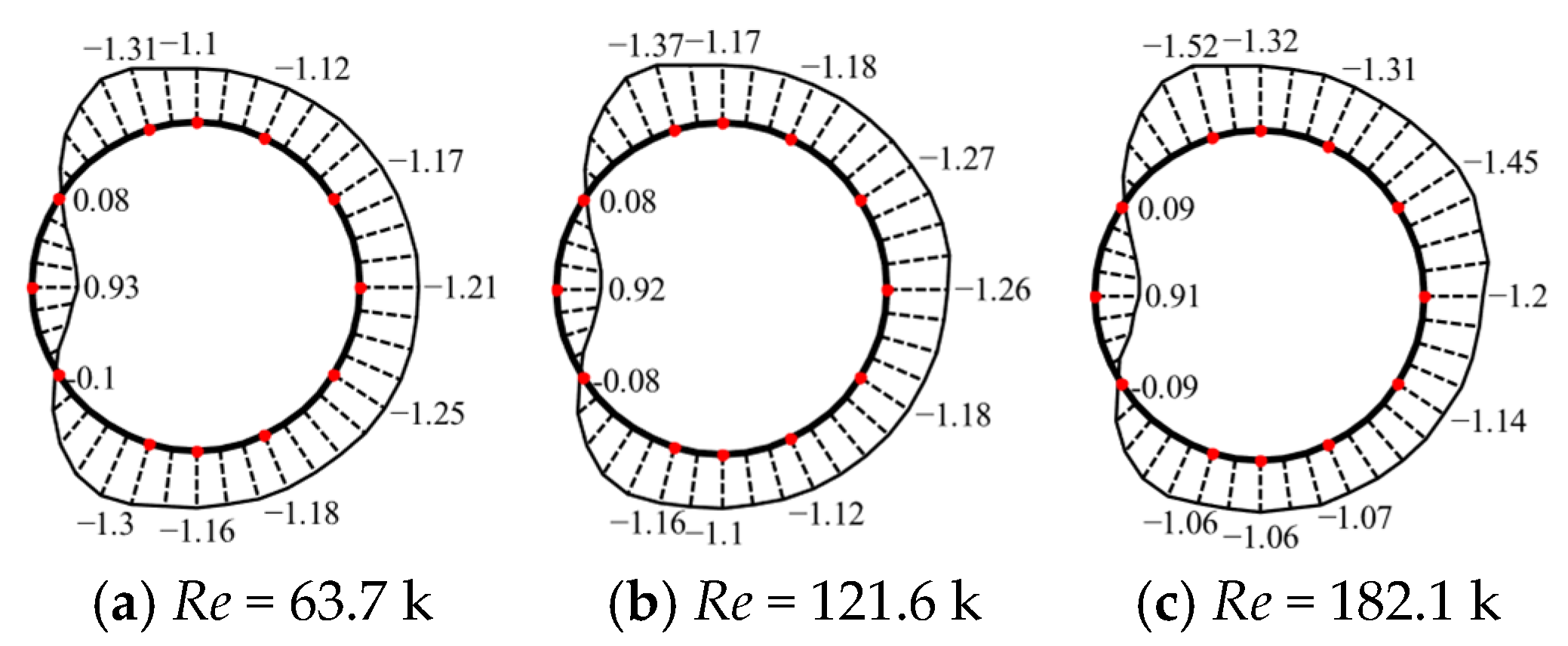

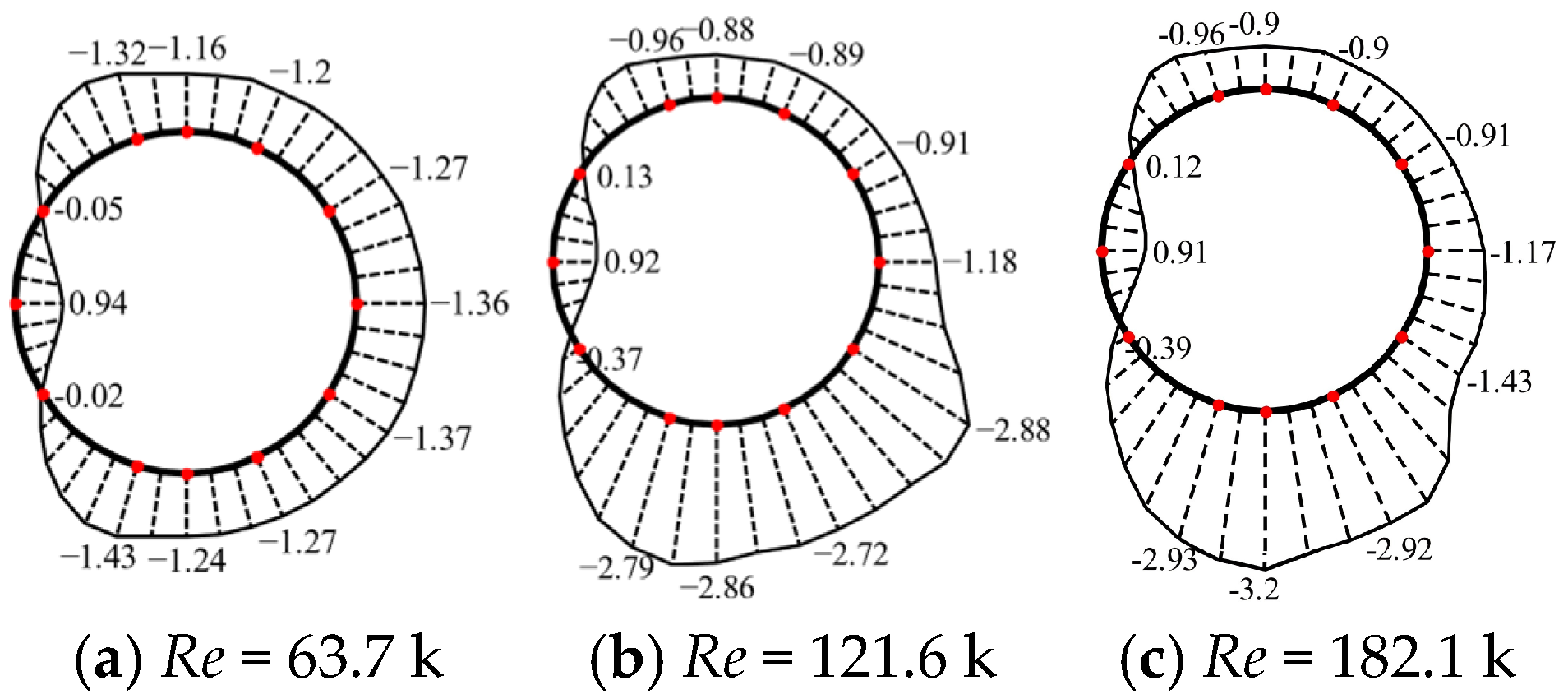

3.1. Mean Pressure Distribution

3.2. Occurrence of Vortex-Induced Vibrations

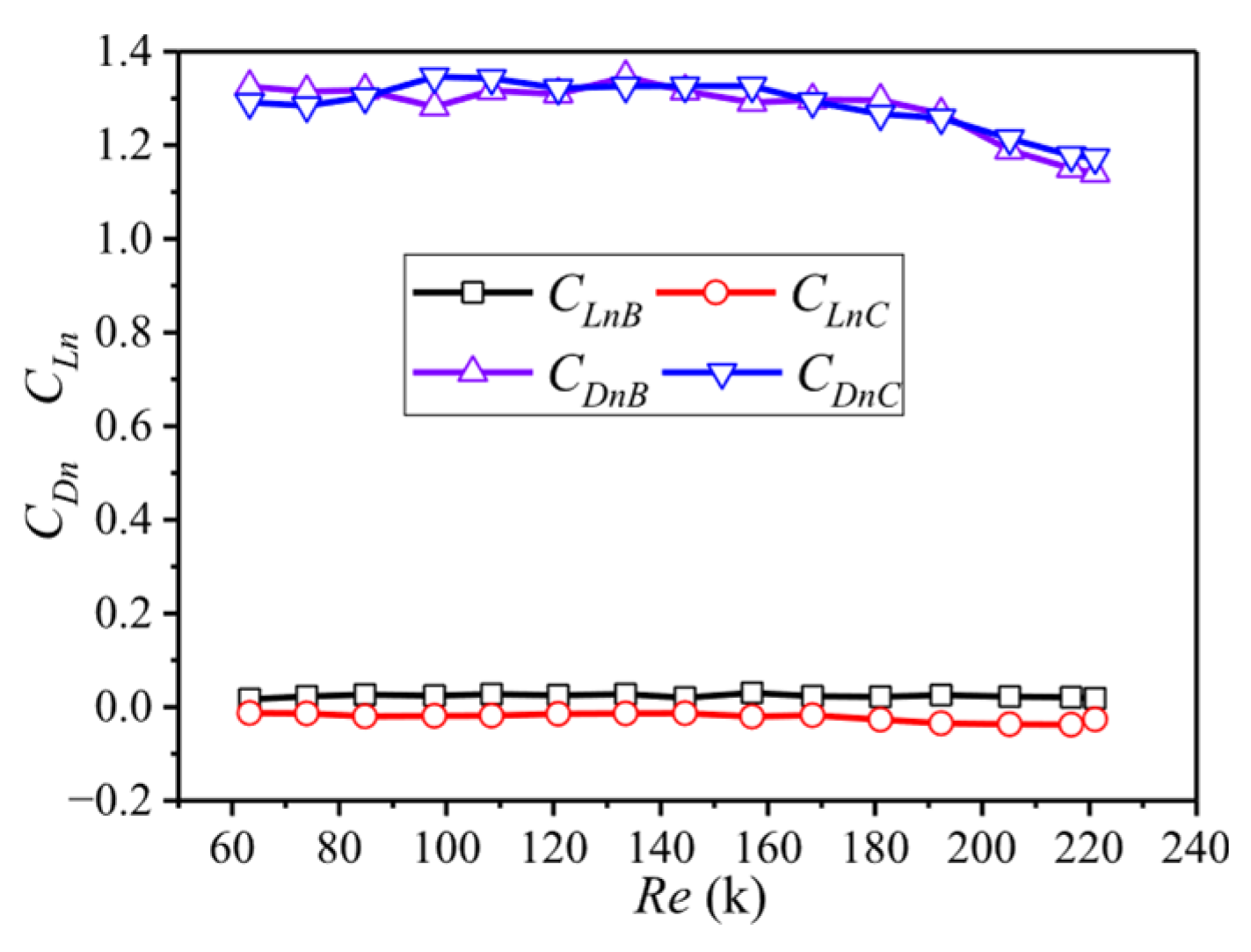

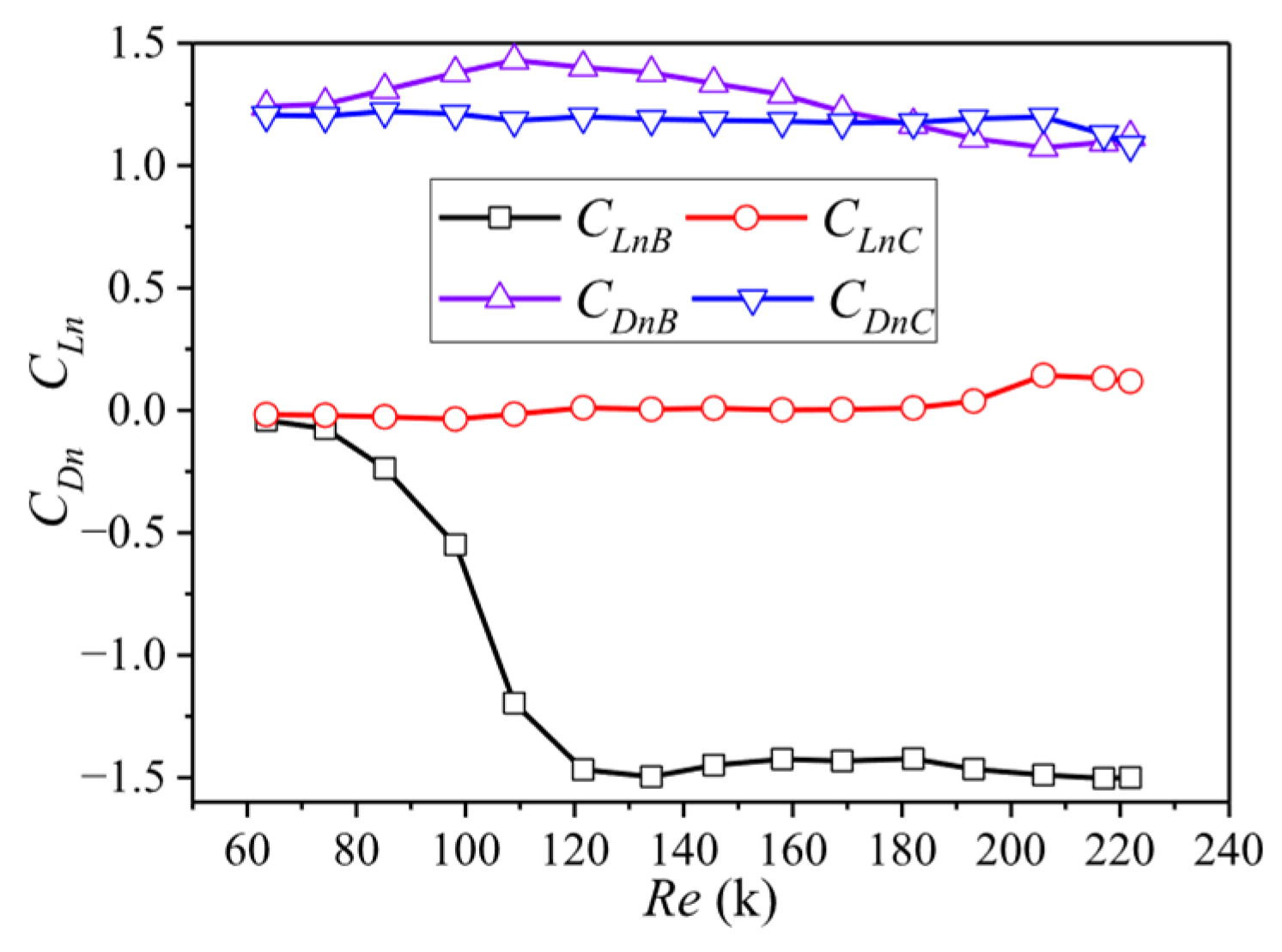

3.3. Mean Aerodynamic Forces

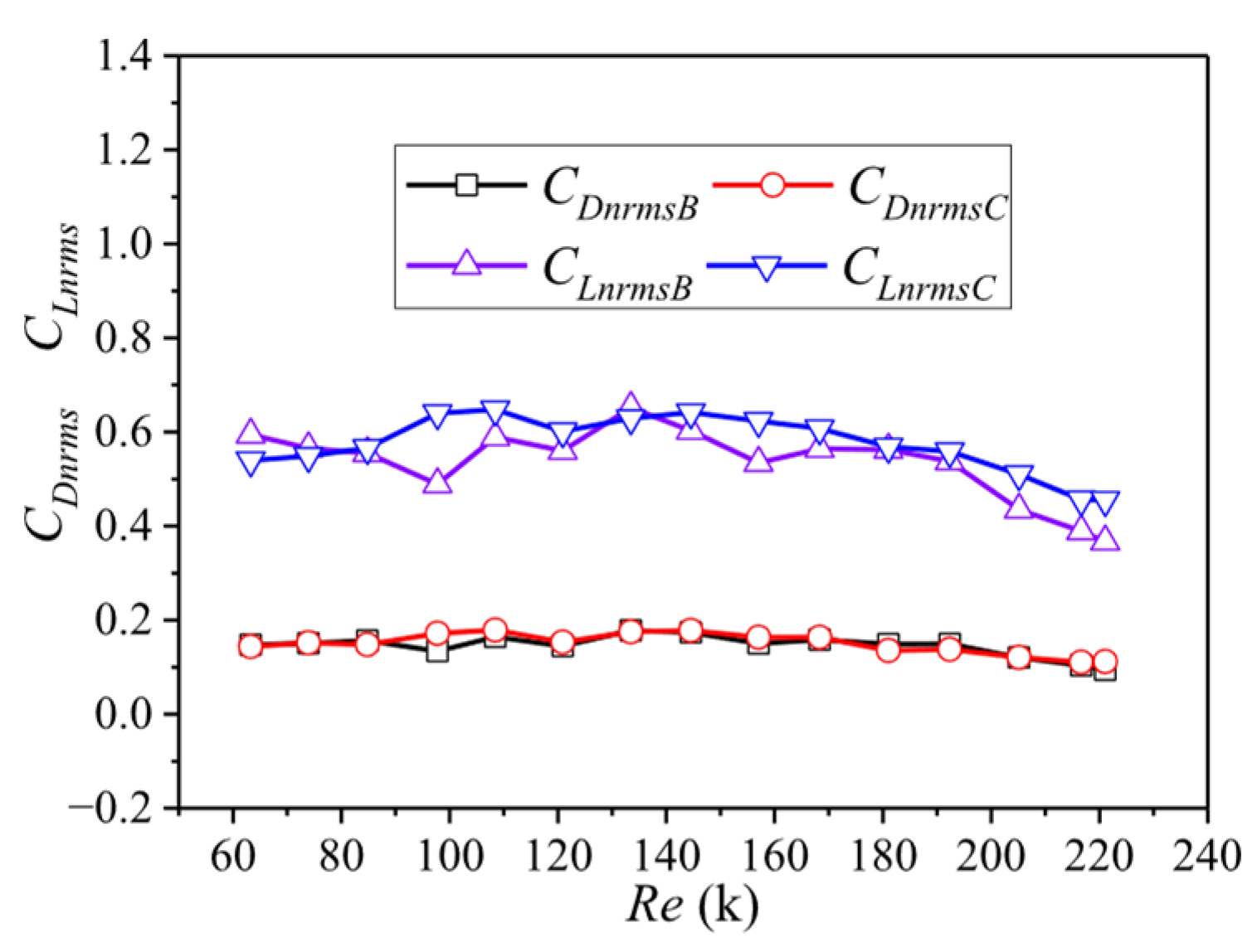

3.4. Fluctuating Aerodynamic Forces

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The flow regime around the yawed cylinder undergoes a fundamental transition as the yaw angle increases. While it remains similar to that of a straight cylinder at small angles (β ≤ 17.4°), a critical change occurs at higher angles. The enhanced axial flow component (U sin β) destabilizes the boundary layer, leading to a premature onset of the critical regime. This is evidenced by a systematic reduction in the critical Reynolds number with increasing yaw angle—from approximately 160,000 at β = 0° to about 120 k at β = 30°.

- (2)

- This early transition directly dictates the evolution of aerodynamic forces. It triggers the formation of asymmetric separation bubbles on the windward surface, which generates significant mean lift forces (e.g., CL ≈ −1.5) and causes a distinct, premature reduction in the mean drag coefficient beyond the identified critical Reynolds number.

- (3)

- Aerodynamic effects are not uniform along the cylinder span. The mid-span “intermediate region” (i.e., Ring C) exhibits behavior distinct from sections more influenced by end-effects (i.e., Ring B), with the latter often entering the critical regime earlier. This highlights the necessity of considering three-dimensional flow effects in design.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Griffin, O.M. Vortex shedding from biuff bodies in shear flow: A review. J. Fluid Mech. 1985, 107, 298–305. [Google Scholar]

- Akosile, O.; Sumner, D. Staggered circular cylinders immersed in a uniform planar shear flow. J. Fluids Struct. 2003, 18, 613–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guven, O.; Farell, C. Surface-roughness effects on the mean flow past circular cylinders. J. Fluid Mech. 1980, 98, 673–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.L.D. Effects of surface roughness on the two-dimensional flow past circular cylinders, part 2: Fluctuating forces and pressures. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 1991, 37, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, J.S. On acircular cylinder in asteady wind at transition Reynolds numbers. J. Fluid Mech. 1960, 9, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshko, A. Experiments on the flow past a circular cylinder at very high Reynolds number. J. Fluid Mech. 1961, 10, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, E. Distribution of local pressure and skin friction around a circular cylinder in cross-flow up to Re = 5×106. J. Fluid Mech. 1968, 34, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearman, P.W. On vortex shedding from a circular cylinder in the critical Reynolds number regime. J. Fluid Mech. 1969, 37, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farell, C.; Blessman, A.J. On critical flow around smooth circular cylinders. J. Fluid Mech. 1983, 136, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Shao, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Li, C.H.; Ma, W.Y.; Liu, X.B. Experimental Study on the Effect of Reynolds Number on Cylindrical Aerodynamics and Flow Field. J. Exp. Fluid Mech. 2016, 30, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg, C. An experimental investigation of the flow around a circular a circular cylinder: Influence of aspect ratio. J. Fluid Mech. 1994, 258, 287–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szepessy, S.; Bearman, P.W. Aspect ratio and end effects on vortex shedding from a circular cylinder. J. Fluid Mech. 1992, 234, 191–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdravkovich, M.M. Flow Around Circular Cylinder; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sears, W.R. The boundary layer of yawed circular cylinders. J. Aeronaut. Sci. 1948, 15, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerner, S.F. Fluid-Dynamic Drag: Practical Information on Aerodynamic Drag and Hydrodynamic Resistance; Hoerner Fluid Dynamics: New York, NY, USA, 1965; pp. 238–396. [Google Scholar]

- King, R. Vortex excited oscillations of yawed circular cylinders. J. Fluids Eng. 1977, 99, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, J.; Hall, B. The spanwise dependence of vortex-shedding from yawed circular cylinders. J. Press. Vessel Technol. 2009, 132, 031301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirakashi, M.; Hasegawa, A.; Wakiya, S. Effect of the secondary flow on Karman vortex shedding from a yawed cylinder. Bull. JSME 1986, 29, 1124–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakil, A.; Green, S. Drag and lift coefficients of inclined finite circular cylinders at moderate Reynolds number. Comput. Fluilds 2009, 38, 1771–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Du, X. Experimental study on cable-staying model of cable-stayed bridges with different wind direction angles. J. Vib. Shock 2005, 24, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, B.; Wang, L. Large Eddy Simulation of the Flow around a Yawed Circular Cylinder at High Reynolds Number. Phys. Fluids 2022, 34, 045111. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Cao, S. Combined effects of yaw angle and surface roughness on the flow around a circular cylinder at subcritical Reynolds number. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2022, 220, 104860. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, T.; Gu, M. Pressure distribution and aerodynamic force decomposition of a yawed circular cylinder: A wind tunnel study. Eng. Struct. 2021, 228, 111548. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Liu, S.; Wang, H. Flow characteristics and aerodynamic forces of a yawed circular cylinder at subcritical Reynolds number. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2020, 202, 104194. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, D.; Xu, Y.; Li, S. Experimental investigation on the aerodynamic forces of a circular cylinder under dynamic yawing motion. J. Fluids Struct. 2023, 116, 103798. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Li, A.; He, X. A deep learning approach for the fast prediction of the aerodynamic forces on a yawed cylinder. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2023, 232, 105283. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Yu, C.; Yu, W.; Liu, X.B. A wind tunnel test study on aerodynamic characteristics of square cylinders with rounded corners. J. Vib. Shock 2023, 42, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Qiu, F.; Tian, X.; Tian, Y.; Chen, G.; Ma, W. Experimental study on Reynolds number effects on mean aerodynamic characteristics of rectangular cylinders with rounded corners. J. Shijiazhuang Tiedao Univ. 2023, 36, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Xu, F.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y. Numerical simulation of the vortex-induced vibrations of a 4:1 rectangular cylinder subjected to yaw uniform currents. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2024, 244, 105818. [Google Scholar]

- Micheletto, D.; Fransson, J.H.M.; Segalini, A. Experimental Study of the Transient Behavior of a Wind Turbine Wake Following Yaw Actuation. Energies 2023, 16, 5147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Hu, Z.; Zhao, H.; Wu, C.G.; Fan, Q.Q. Study on the influence of leading-edge cylinder on aerodynamic performance and erosion wear of wind turbine airfoils. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2024, 45, 166–173. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Huang, H.; Iglesias, G.; Wang, J.; Bashir, M. Fully coupled aero-hydrodynamic analysis of floating vertical axis wind turbines in staggered configurations. Energy 2025, 337, 138679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Liu, Q.; Du, X.; Liu, X. Aerodynamic forces and galloping instability for a skewed elliptical cylinder in a flow at the critical Reynolds number. Fluid Dyn. Res. 2017, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J.D. Wind Loading of Structures, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.Q. Bridge Wind Engineering; Beijing People’s Communications Press: Beijing, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg, C.; Sunden, B. Turbulence and reynolds number effects on the flow and fluid forces on a single cylinder in cross flow. J. Fluids Struct. 1987, 1, 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Gu, M. Study on the characteristics of pulsating wind on the surface of inclined zipper. J. Vib. Shock 2012, 31, 139–144. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, X.; Li, Z.; Yang, H.; Wang, F.; Ma, W.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, Y. Study on Wind Load Distribution and Aerodynamic Characteristics of a Yawed Cylinder. Buildings 2025, 15, 4390. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234390

Yuan X, Li Z, Yang H, Wang F, Ma W, Zhao Q, Yang Y. Study on Wind Load Distribution and Aerodynamic Characteristics of a Yawed Cylinder. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4390. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234390

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Xinxin, Zetao Li, He Yang, Fei Wang, Wenyong Ma, Qiaochu Zhao, and Yong Yang. 2025. "Study on Wind Load Distribution and Aerodynamic Characteristics of a Yawed Cylinder" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4390. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234390

APA StyleYuan, X., Li, Z., Yang, H., Wang, F., Ma, W., Zhao, Q., & Yang, Y. (2025). Study on Wind Load Distribution and Aerodynamic Characteristics of a Yawed Cylinder. Buildings, 15(23), 4390. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234390