Abstract

In the context of China’s vigorous promotion of “better housing” construction, transforming affordable housing into “better housing” has become an important practical task. Since the 1960s, when the public housing system was standardized, South Korea has established a diversified and high-quality public housing supply system. Therefore, this study takes public rental housing in Seoul as examples, summarizes the development experience of public housing in South Korea, with the aim of providing new inspirations for the development direction, concepts, and spatial optimization of affordable housing in China. The research examines the Korean public housing policies, housing history, and cultural background from a theoretical perspective, analyzes the formation background and supply types of public housing, as well as the evolution mechanism of the unit plan, and takes typical public rental housing completed in the 2010s as examples to analyze and explore the spatial composition and structural characteristics of the affordable housing unit plans. Finally, based on China’s national conditions, this study highlights the policy implications of South Korea’s public housing experience for the development of affordable housing in China and proposes a “policy-space-culture” tripartite guidance framework to support the realization of the goal of constructing “better housing” within the affordable housing sector. Specifically, (1) at the policy level, it is recommended to establish a multi-tiered supply mechanism and implement an early warning system for emerging affordable housing demands; (2) at the spatial design level, standardization and modularization of housing design are advocated; and (3) at the cultural level, it is suggested to enhance cultural adaptability by aligning housing design with local residential culture and residents’ living habits.

1. Introduction

Public housing serves as the basic material living guarantee for the impoverished and low-to-middle-income groups, and its construction and supply primarily rely on the support from the government and non-profit organizations [1]. Given the differences in national conditions and economic development among various countries, public housing exhibits diversity in naming, supply models, and target audiences [2,3,4,5,6]. For instance, Japan and South Korea provide different forms of housing security for their citizens based on the definition of “public housing”, such as “publicly-operated housing and UR rental housing (formerly public operated housing, and now provided by Urban Revitalization Agency), etc.” in Japan and “permanent rental housing, national rental housing, long-term deposit base housing, etc.” in South Korea. In China, public housing is defined as “affordable housing” and effectively alleviates the housing problems of the impoverished, low-income groups, and low-to-middle-income groups through various housing types such as low-rent housing, public rental housing, and economically affordable housing [2,3].

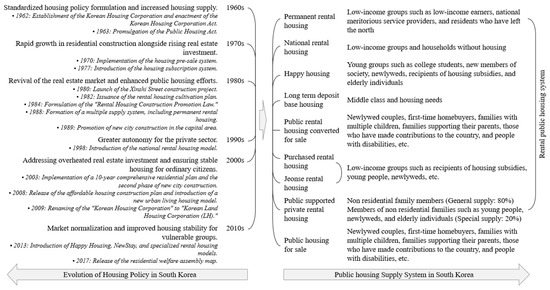

Since the early 1960s, South Korea has embarked on the exploration and practice of public housing policies and has continuously promoted the construction, improvement, and optimization of the system in the following decades. Especially in the 1980s, the South Korean government implemented more systematic and standardized management measures for the rental housing market, which effectively promoted the diversified development of supply entities and gave rise to various operation models, thus forming the current extensive and diverse public housing supply system in South Korea [3,7,8,9,10]. In contrast, the substantive start of China’s affordable housing sector was relatively late. Although the models of economically affordable housing and low-rent housing, which reflect the social security function, were proposed successively in 1994 and 1998, the overall development process was rather slow. It was not until 2010, when the new type of affordable housing model, public rental housing, which aims to solve the housing difficulties of the “middle-income group” in cities, emerged, that China’s affordable housing supply system gradually entered a more complete new stage. However, under the macro background of the continuous large-scale growth of urban population and the deepening of the urbanization process, the supply of affordable housing still faces severe and complex challenges in terms of construction speed, supply scale, spatial layout and distribution management, etc. [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Therefore, the report of the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China clearly stated that it is necessary to “accelerate the construction of a housing system with multiple supply subjects, multiple channels of guarantee, and the coexistence of renting and purchasing”, which has clarified the direction for the future development of China’s housing security system. Subsequently, the “14th Five-Year Plan” further emphasized the need to continuously increase the effective supply of affordable housing and improve the basic institutional framework and related support policies for the construction and operation of affordable housing, specifically proposing the requirement to expand the supply of affordable rental housing. Against this backdrop, given the certain similarities between China and South Korea in terms of cultural background and the role of the government in the housing market, the rich experience, effective strategies and practical lessons accumulated by South Korea in its long-term public housing development process have significant theoretical reference value and practical significance for the continuous healthy development of China’s affordable housing system in the current and future periods.

Furthermore, against the backdrop of the current urbanization process in China, where the contradiction among “population-space-environment” is intensifying, the core of urban construction is shifting from expansion in volume to improvement in the quality of existing resources. Correspondingly, residents’ demands are also evolving from the basic housing supply to meet their living needs to a comprehensive demand for beautiful environments, convenient facilities, and sustainable communities [20]. Following the emphasis placed by the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development on the importance of building “better housing” at the end of 2023, in early 2024, it reiterated the need to build in accordance with green, low-carbon, intelligent, and safe standards, focusing on housing layout design, supporting infrastructure development, and public service provision, to ensure that public housing meets the standard of “better housing,” enabling residents to live comfortably, safely, and conveniently. Subsequently, by the end of 2024, the official release of the “Technical Guidelines for Better Housing” and the “Architectural Design Guide for Better Housing in the New Era” marked a new phase in China’s housing development. These guidelines comprehensively integrate key issues such as socio-economic development, new urbanization strategies, urban renewal, aging populations, housing security, green and low-carbon construction, and residential industry transformation. At the same time, to promote a sustainable architectural environment, the design guide has established a direction for industrialized construction characterized by large-space and modular design concepts. It emphasizes the concept of long-lasting buildings through strategies such as structural safety, durability, and flexible spatial planning. It also proposes policies to enhance age-friendly, barrier-free design and intelligent security systems to improve overall building quality. Furthermore, it incorporates considerations such as economic affordability and facilities suitable for all age groups into the green and low-carbon design framework. However, analysis of the spatial composition of unit plans in China’s public housing reveals numerous challenges and opportunities. For instance, the floor area of affordable housing is typically limited to less than 60 square meters, with unit designs primarily restricted to two-bedroom layouts. This often results in insufficient living space for households comprising three or more members. Therefore, it is imperative to systematically optimize housing spatial configurations and scales based on residents’ actual living needs, daily behavioral patterns, and potential changes in family structure—such as children reaching adulthood or elderly relatives moving in. Research indicates that in terms of unit layout, public housing in South Korea effectively accommodates the demand for three-bedroom units among multi-person families, achieving efficient space utilization within constrained areas and demonstrating strong adaptability. Notably, under the combined influence of housing policy regulation and market mechanisms, the design of public housing in South Korea has successfully achieved high standards of living quality. The development of this spatial configuration stems not only from policy frameworks but is also deeply shaped by local lifestyles, cultural customs, and historical traditions. Building upon this, adhering to the principle of “people-oriented and comfortable living,” integrating the core concept of the “better housing,” and conducting an in-depth analysis of the unit plan characteristics of South Korean public housing can provide valuable practical insights for improving living environments and optimizing the spatial design of affordable housing in China [3,21,22].

Although many scholars have explored the development of China’s affordable housing from various disciplinary perspectives and have put forward rich experiences and insights, most of the existing studies are characterized by singularity in terms of disciplinary fields, research methods, methodology, and the presentation of results, and thus have certain limitations. For instance, scholars such as Deng and Tan [5,18] in the field of urban and real estate economics, based on the review of the evolution of policies related to affordable housing in China, analyzed the current construction status and institutional issues of China’s affordable housing; Doctor Hu [16] and scholar Jin [17] in the field of law and social sciences, through comparative studies of typical policies on affordable housing at home and abroad, explored the improvement measures and innovative mechanisms of China’s affordable housing policies. At the same time, some scholars, such as Wang [23] and Liu [24], obtained inspiration through research on public housing in South Korea, but these studies were all focused on the policy mechanism level and had certain limitations. Additionally, some scholars, such as Kim et al. [10,25,26,27,28,29,30,31], studied South Korean public housing policies from perspectives such as social integration degree, the necessity of group differentiation, the evolution of supply mechanisms, management models, and sustainable development. However, compared with studies at the policy level, research on the layout and spatial structure of public housing from an architectural perspective is extremely scarce. In the context of pursuing high-quality living environments, in addition to the construction and supply mechanisms of public housing, its spatial design is also of great importance. In view of this, this study integrates multiple disciplinary fields and conducts research on South Korean public housing from three dimensions—policy, culture, and space—in order to explore its implications for the development of China’s affordable housing.

2. Institutional Foundation and Cultural Roots of Public Housing in South Korea

2.1. Institutional Foundation

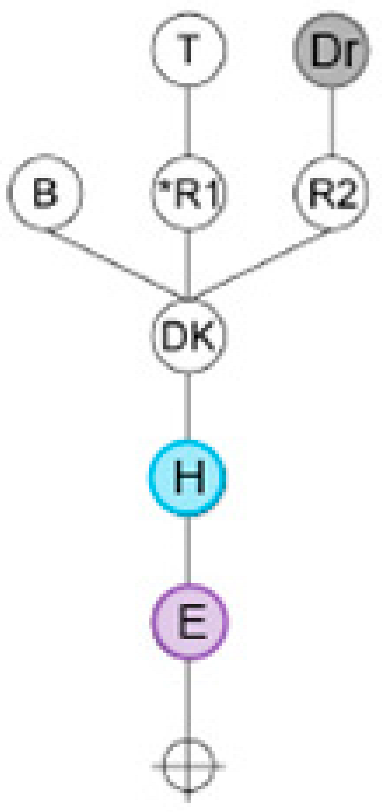

Throughout its long history, South Korea’s housing policy development has been profoundly shaped by the period of Japanese colonial rule, which marked a pivotal turning point that catalyzed fundamental transformations in its housing policy framework (see Figure 1). As early as the 1940s, in response to growing pressures for housing construction and urban development, the Korean Peninsula established a specialized agency known as the “Choson Housing Corps” in 1941. Following Korea’s liberation from colonial rule in 1945, this institution was reorganized and renamed the “Daehan Housing Corps,” continuing to play a critical role in housing construction during the challenging post-war reconstruction phase. However, due to persistent political instability and frequent domestic upheavals at the time, its operational effectiveness was significantly constrained, rendering it unable to fully address society’s urgent housing demands. It was not until 1962 that the Korean government formally launched its first “Economic Development Five-Year Plan,” under which housing construction and supply policies were explicitly elevated to a strategic priority essential to national economic development and integrated into the broader economic planning framework. Against this historical backdrop and policy direction, the “Daehan Housing Corporation” emerged as a more professional and empowered institution dedicated to housing development and management. To ensure the effective operation of this entity and the systematic implementation of housing policies, the government further strengthened the legal and regulatory framework by enacting key legislation, including the “Daehan Housing Corporation Act” and the “Public Housing Act.” These laws provided robust legal foundations for the establishment, functions, and authority of the Daehan Housing Corporation, while also fostering the emergence and growth of diverse housing providers, such as local autonomous bodies and public–private partnerships. Concurrently, more comprehensive and detailed planning was undertaken regarding the operational framework of the public housing system, encompassing construction standards, funding mechanisms, allocation procedures, and management and maintenance protocols. This series of institutional and legislative measures collectively laid a solid foundation for the sustained advancement of housing policies and the healthy development of South Korea’s housing sector [7,8,9,10].

Figure 1.

Institutional foundation of public housing in South Korea.

During the evolution of housing policies in South Korea, the public housing supply system has gradually achieved both improvement and diversification. Initially, public housing was regarded as one of the strategies to revitalize the South Korean economy, and it was mainly provided in the form of commercial housing. It was not until 1982, when the “Housing Establishment Plan” was enacted, and 1984, when the “Promotion Law for Housing Construction” was enacted, that the rental housing market began to become standardized. In 1988, with the “2,000,000 Housing Construction Plan” being implemented by the South Korean government, in addition to commercial housing, a rental housing system including permanent rental housing, employee rental housing, and long-term rental housing was also established. These measures effectively alleviated the problem of insufficient housing supply and successfully constructed a diversified housing supply system centered on permanent rental housing. In 1998, a new type of rental housing model, national rental housing, emerged and developed in parallel with permanent rental housing as the main public rental housing model. In the 2000s, with the implementation of the “Bogeumjari Housing (a new concept of residential type that includes small and medium-sized commercial housing and rental housing constructed by the public) Construction Plan”, Urban-Type Living Residences emerged as a new rental housing model. Subsequently, in the 2010s, public housing with names such as Happy Housing, New Stay, and Specialized Rental Housing emerged, eventually forming a diverse public housing supply system. With the adequate supply of public housing and the transformation of housing policies from quantity supply to quality improvement, South Korean public housing supply has gradually shifted towards the construction of high-quality public rental housing. Especially in 2017, the release of the “Housing Welfare Roadmap” further accelerated the development of public housing. To date, this diversified supply system, as the core policy goal of ensuring the stable housing of low- and middle-income groups and vulnerable social classes, continues to play an indispensable role [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

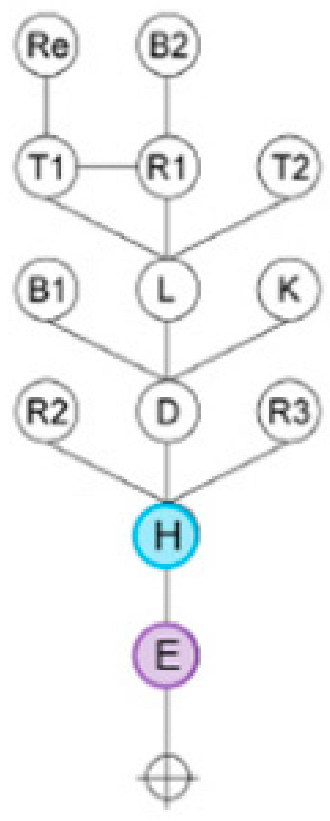

2.2. Cultural Roots

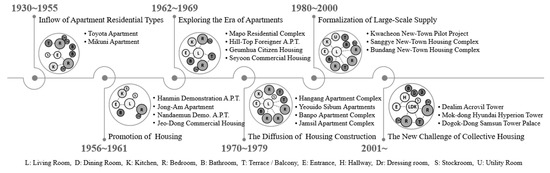

Since the 1930s, the advancement of industrialization on the Korean Peninsula has prompted rural and fishing village residents to migrate to urban centers. This population migration trend has given rise to numerous challenges for modern housing, and the collective housing living model emerged and has undergone six stages of development and evolution (as shown in Figure 2), becoming a hallmark form of modern housing in South Korea. Under the influence of political environment and living habits, the unit plan of Korean collective housing has also undergone a transformation, from traditional layouts such as Japanese tatami, separate bathrooms, and enclosed kitchens to modern layout patterns such as L.D.K. areas centered around the living room (integrated living room, dining room, and kitchen), multi-functional spaces, and extended balconies [8,10,13,22,32,33,34,35]. Despite the changes in lifestyle, Korean residential design still retains distinct cultural elements. Among them, the sunken entrance hall corresponds to the sitting area and the custom of removing shoes upon entering; the spatial layout centered around the living room stems from the traditional “centered hall system”; the floor heating system is the modern inheritance of the Korean warm-bamboo floor culture. Driven by the dual forces of cultural genes and modern living needs, the layout structure of Korean collective residences has undergone profound changes. From the early cramped spaces, simple functions, and inappropriate scales, it has evolved to the present emphasis on functional integration, refined spatial layout, personalized demand consideration, and the integration of intelligent technology to create a high-quality living environment [36,37].

Figure 2.

Development and spatial composition evolution of housing in South Korea.

3. Overview of Analysis Cases

3.1. Selection of Analysis Cases

Since the 1980s, when the rental housing market in South Korea became standardized, various forms of public rental housing, including permanent rental housing, began to flood the market in large numbers. Subsequently, in 1998, the introduction of the national rental housing led to the parallel development of both permanent rental housing and national rental housing, becoming the main form of public rental housing in South Korea at present and accounting for a considerable proportion of the supply. At the beginning of the 21st century, the “Bogeumjari Housing Construction Plan” implemented in South Korea further promoted the diversification of public housing types and the comprehensive coverage of the target audience. This study aims to provide new insights for the development of affordable housing in China and the spatial composition of unit plans.

Therefore, considering the actual situation in China where the public rental housing system serves as the core supply form, this study selects the corresponding housing types—permanent rental housing mainly targeting low-income and middle–low-income groups and national rental housing—as the main research objects [7,8,9]. Moreover, given that the development of China’s public housing started relatively late, especially the public rental housing model only began to be gradually promoted and on a large scale since 2010, this study focuses on the large-scale housing projects developed by the two major supply entities of public housing in South Korea—the Land and Housing Corporation (LH) [38] and the Seoul Housing Corporation (SH) [39]—after 2010 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Analysis of cases of public rental housing in Seoul.

3.2. Analysis of Architectural Characteristics

Although the development of public housing in South Korea started relatively early, the housing problems faced by low-income and middle–low-income groups still persisted until the 2010s. The South Korean government has continuously emphasized the need to enhance the stability of housing for vulnerable groups and has actively promoted the construction and supply of public housing. Among the 9 research case projects, except for P-4 with 790 households and P-6 with 2200 households, the construction scale of the other 7 projects was between 1000 and 1300 households. Moreover, except for P-2 with 1065 households, which are all applicable to permanent rental housing and national rental housing, the other projects provide various types of public housing. Therefore, among the 11,440 public housing units in the nine research case projects, permanent and national rental housing account for 6046 units, and they are all separated from other supply types and exist in independent building blocks.

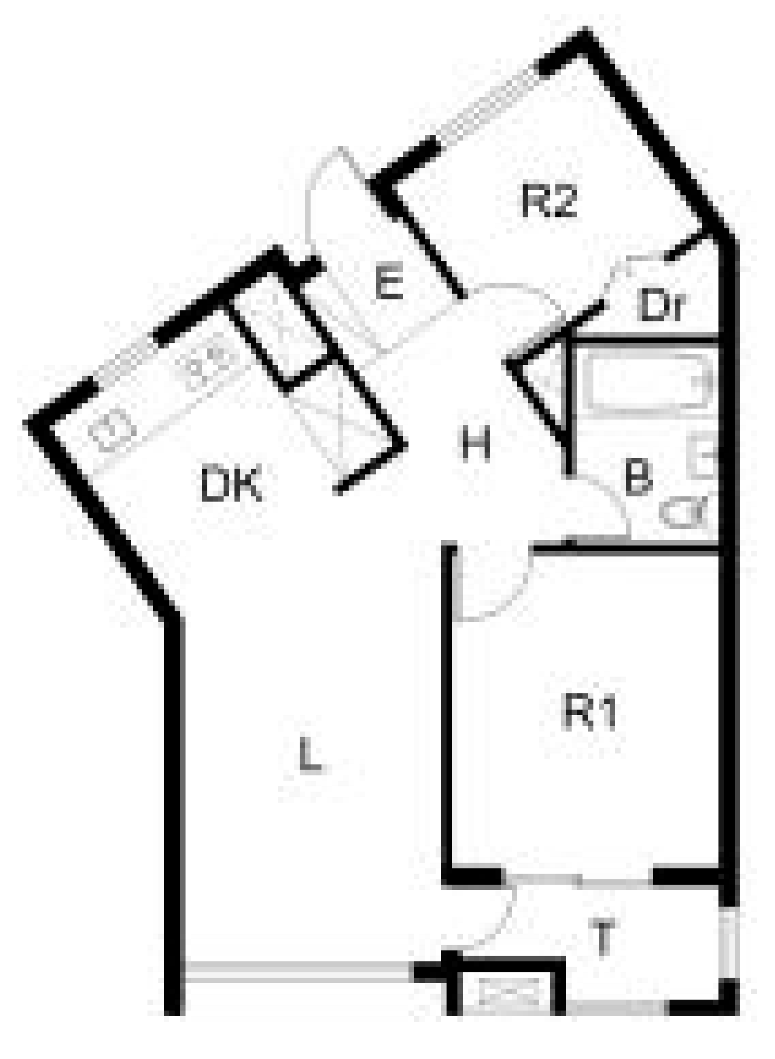

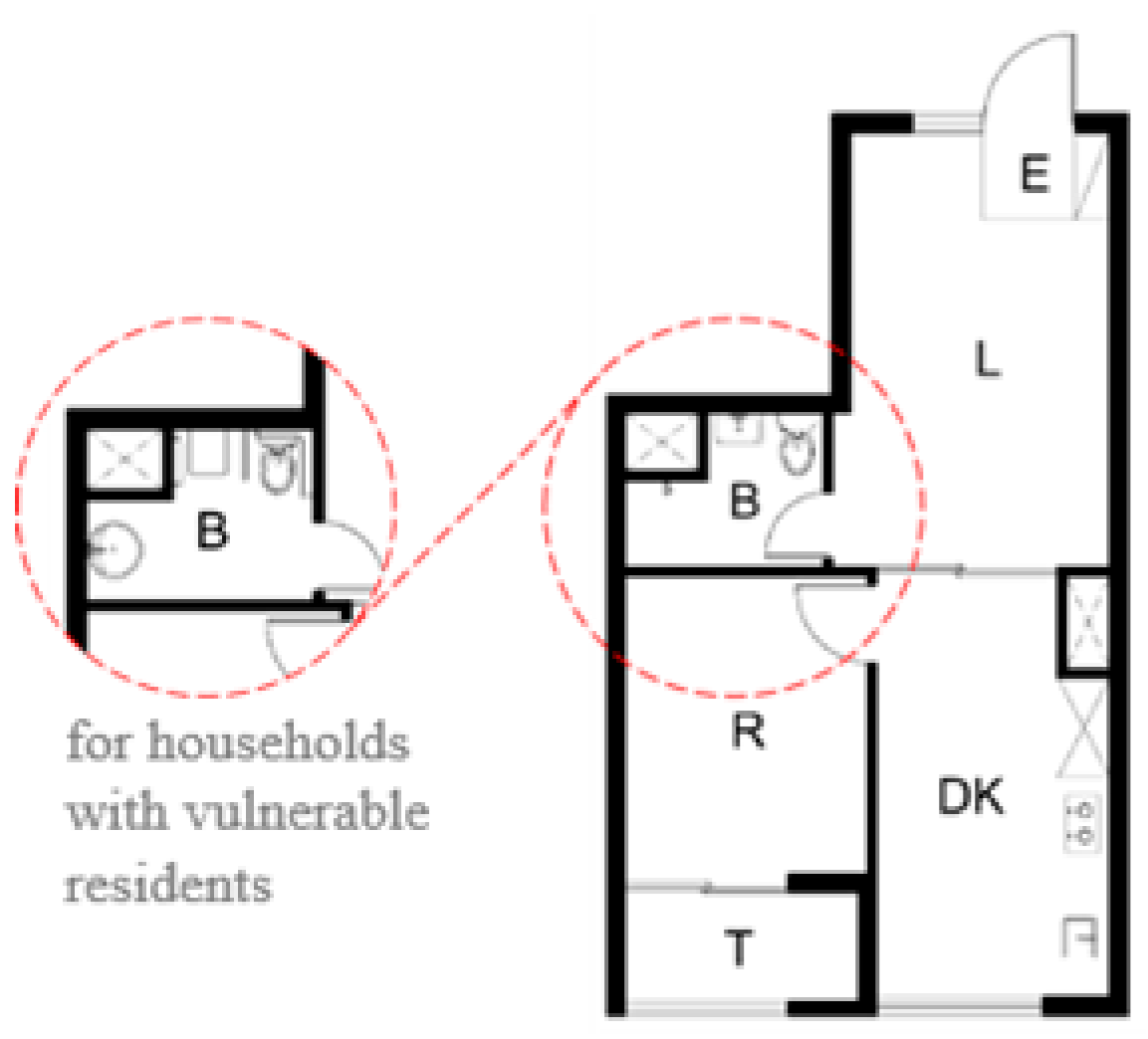

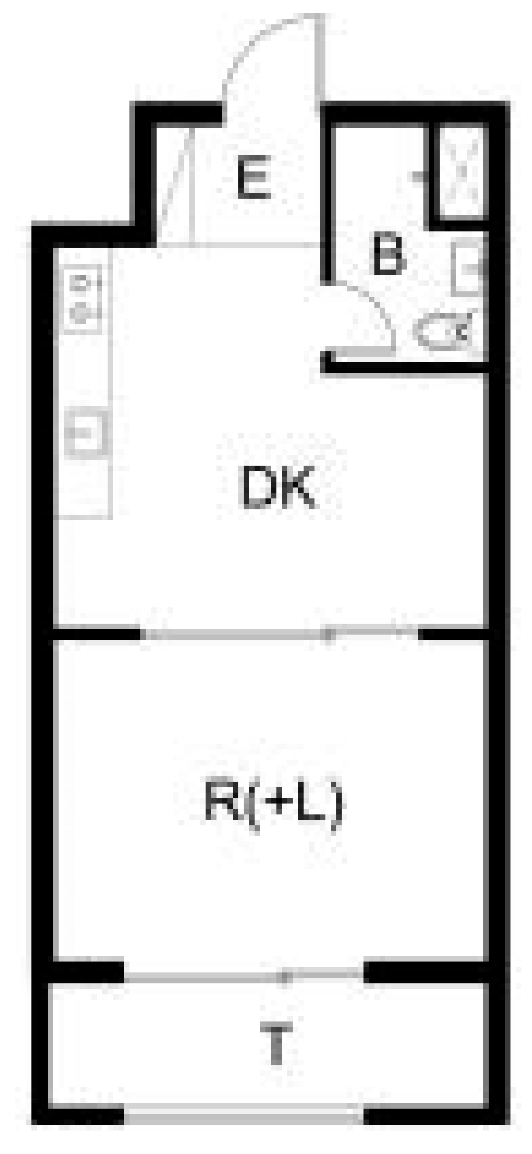

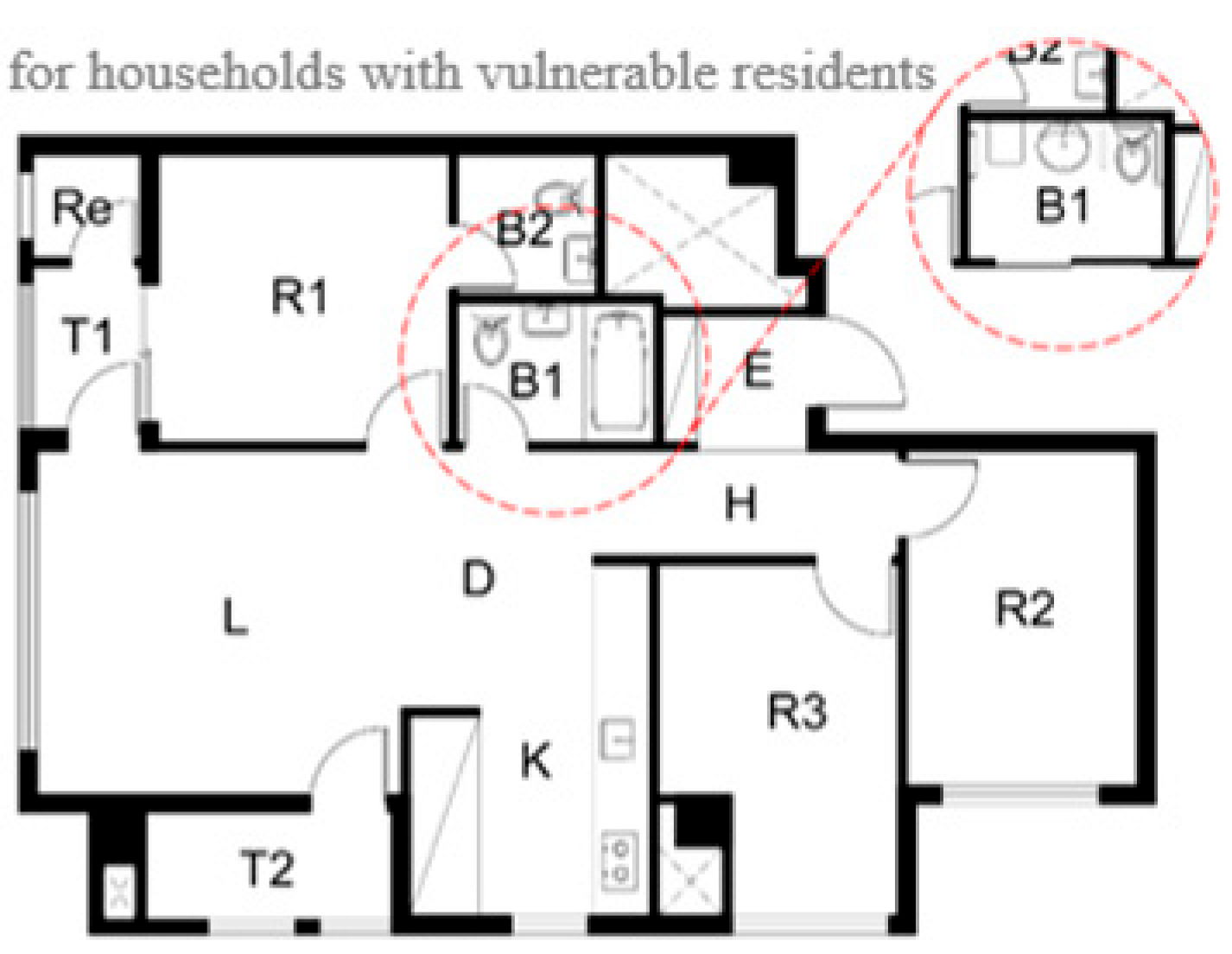

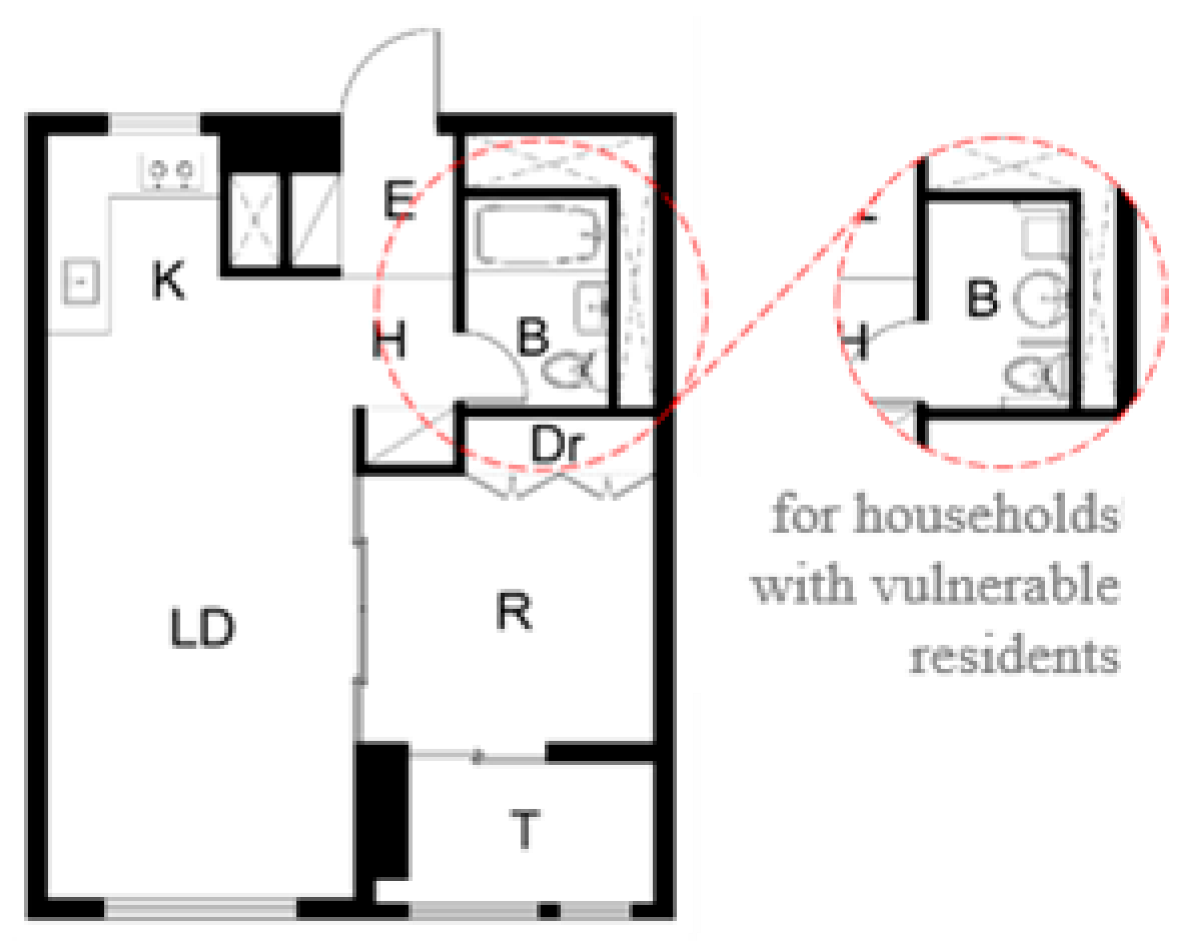

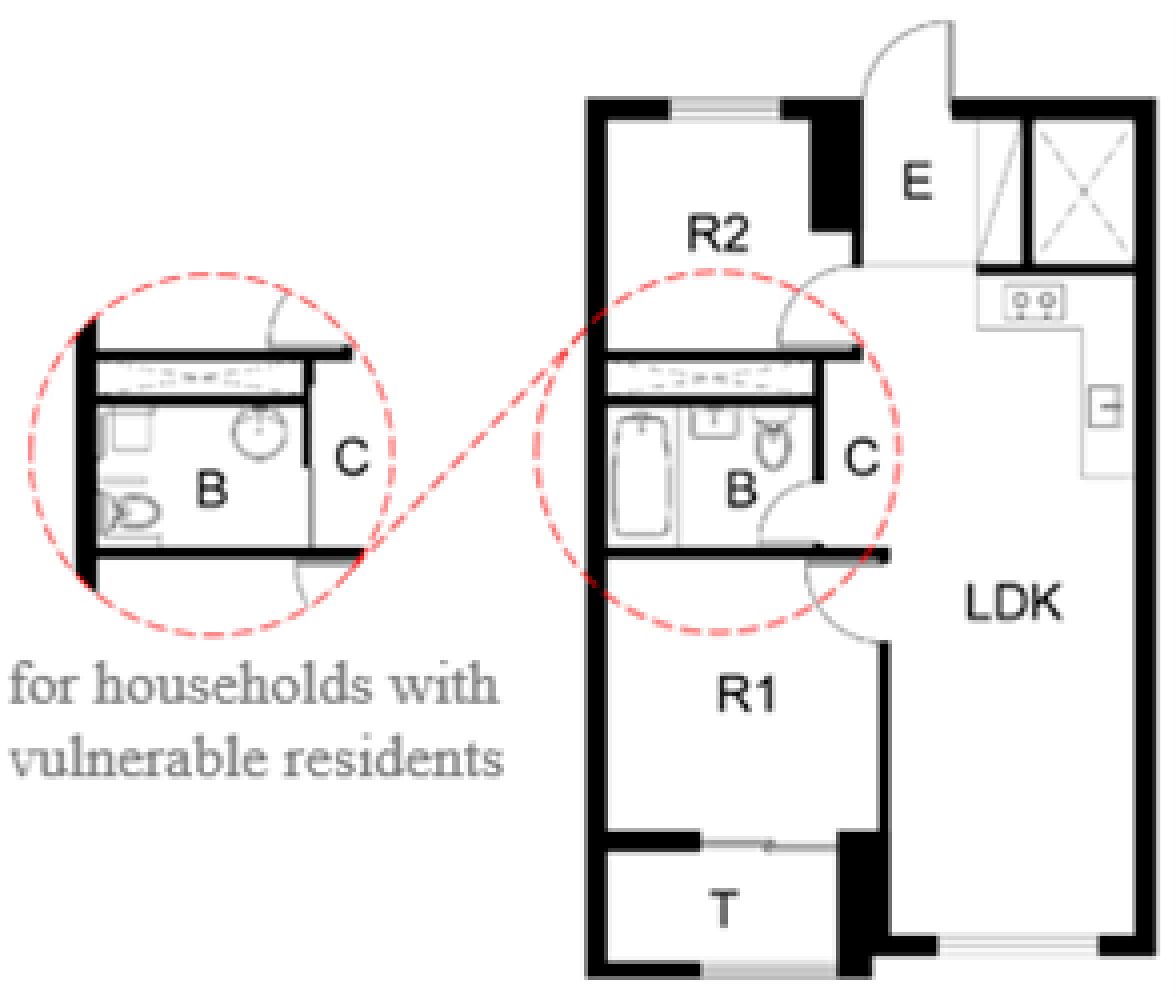

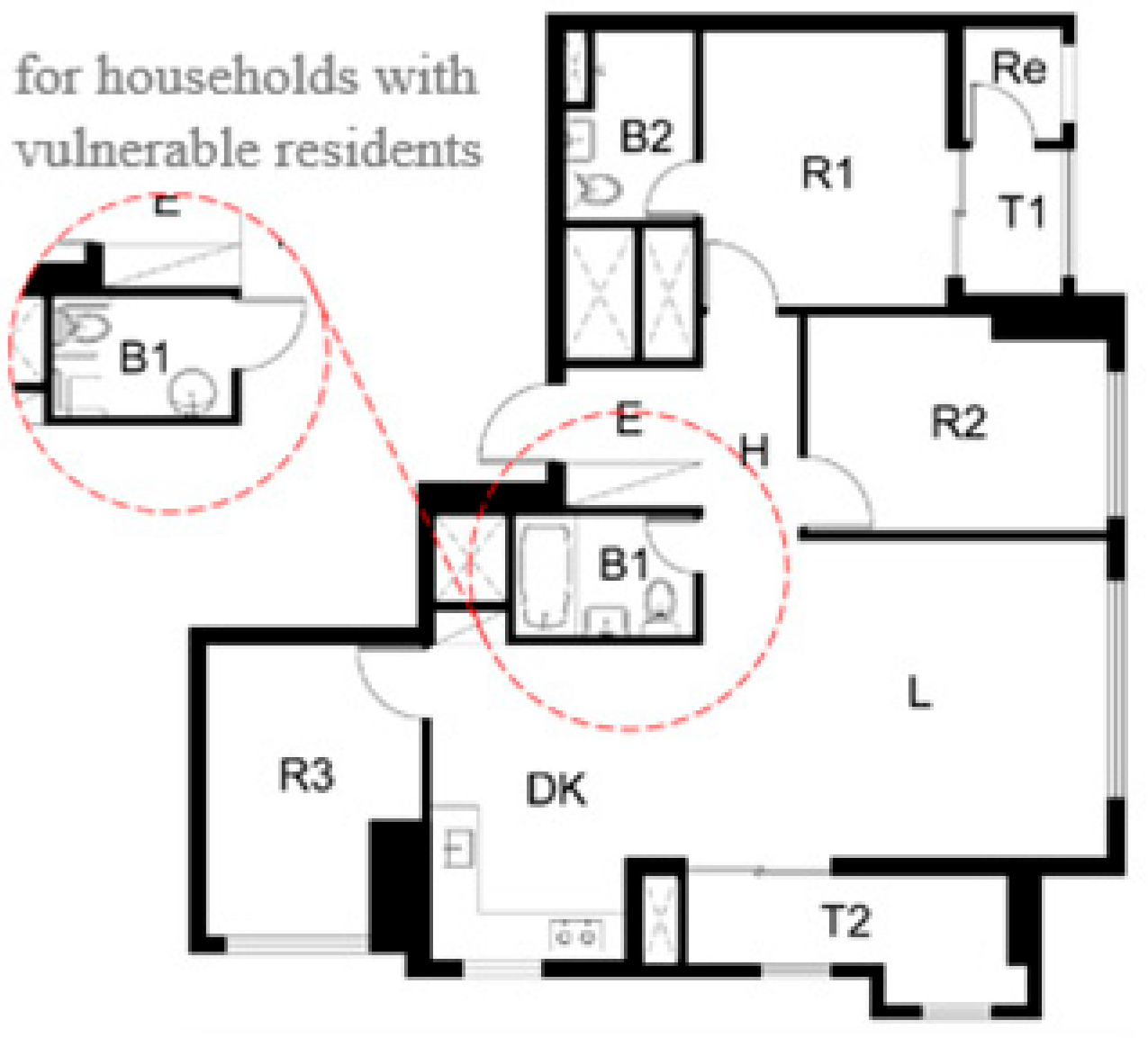

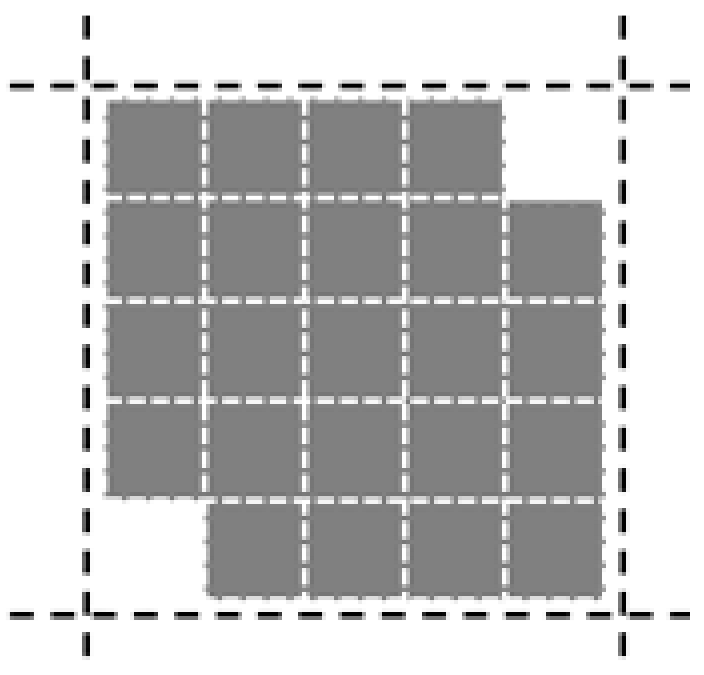

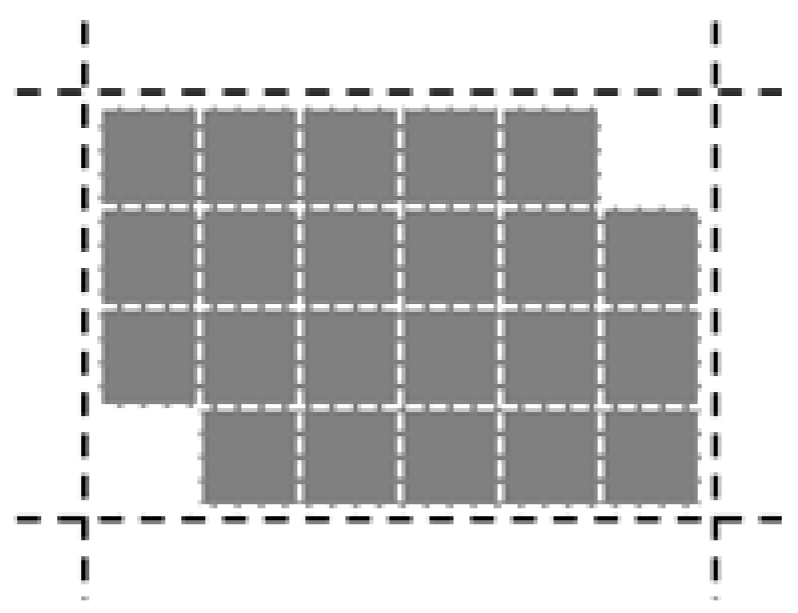

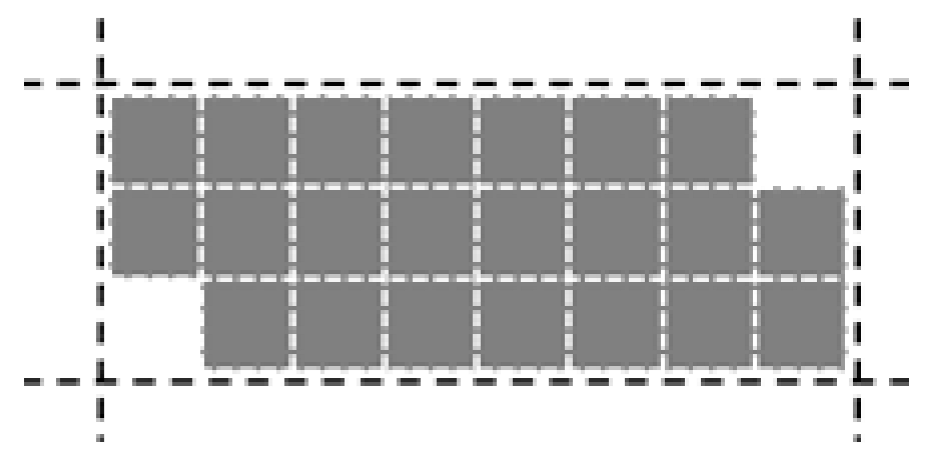

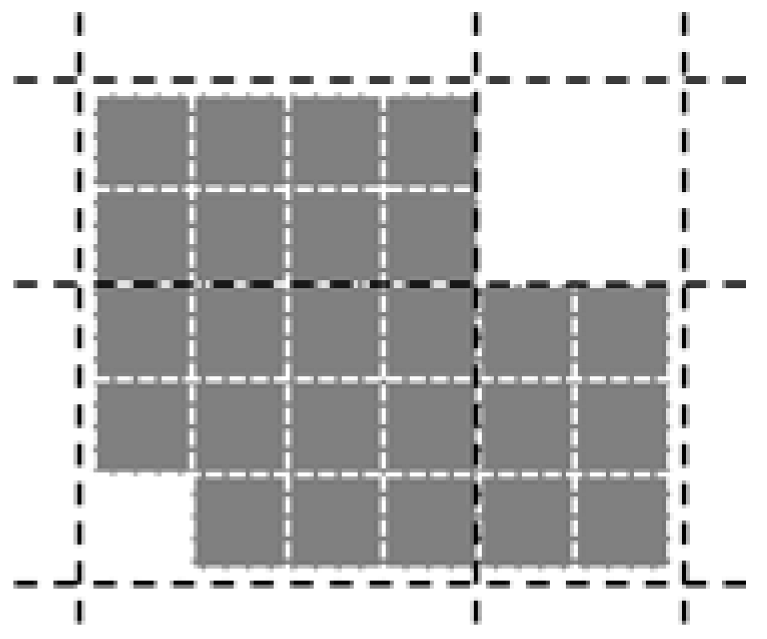

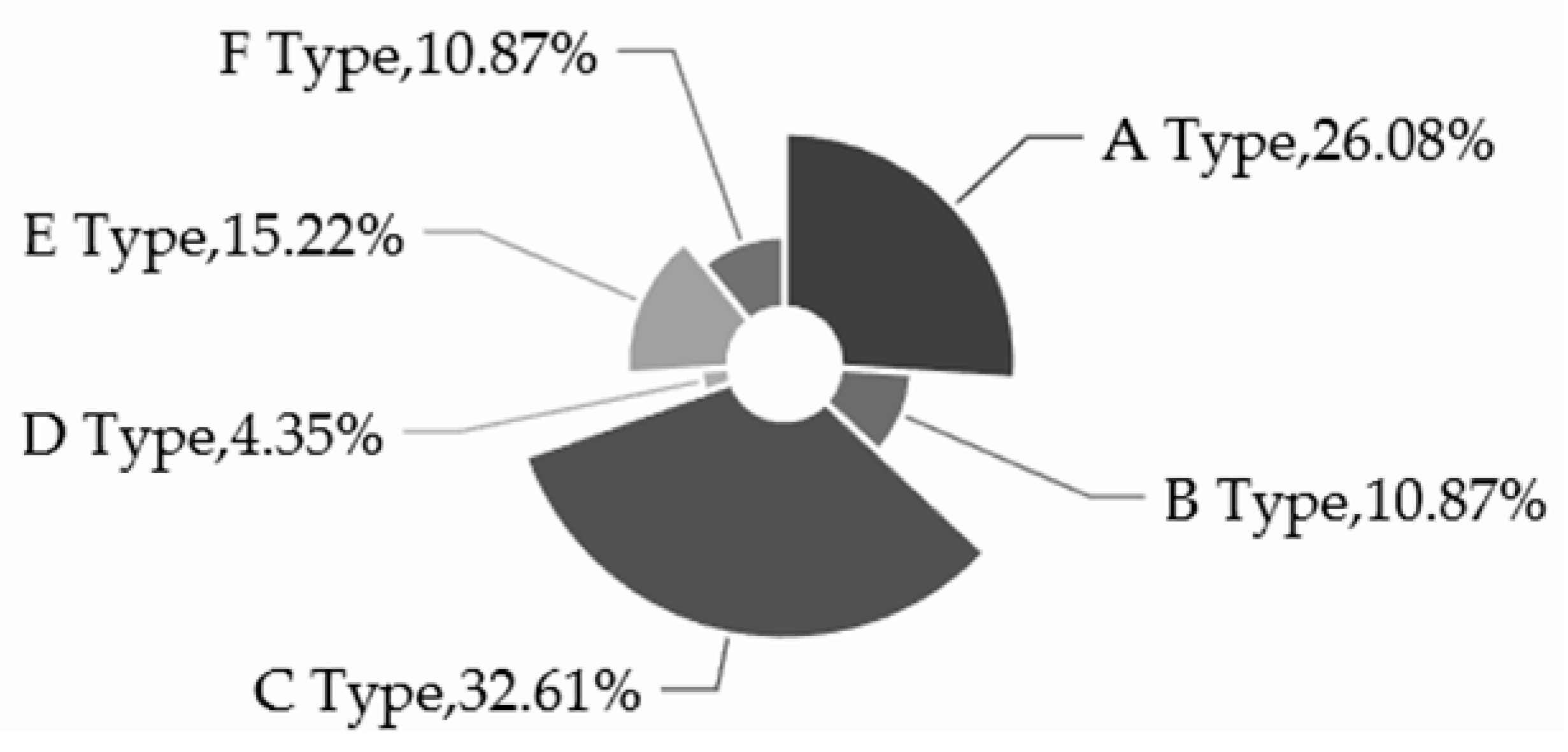

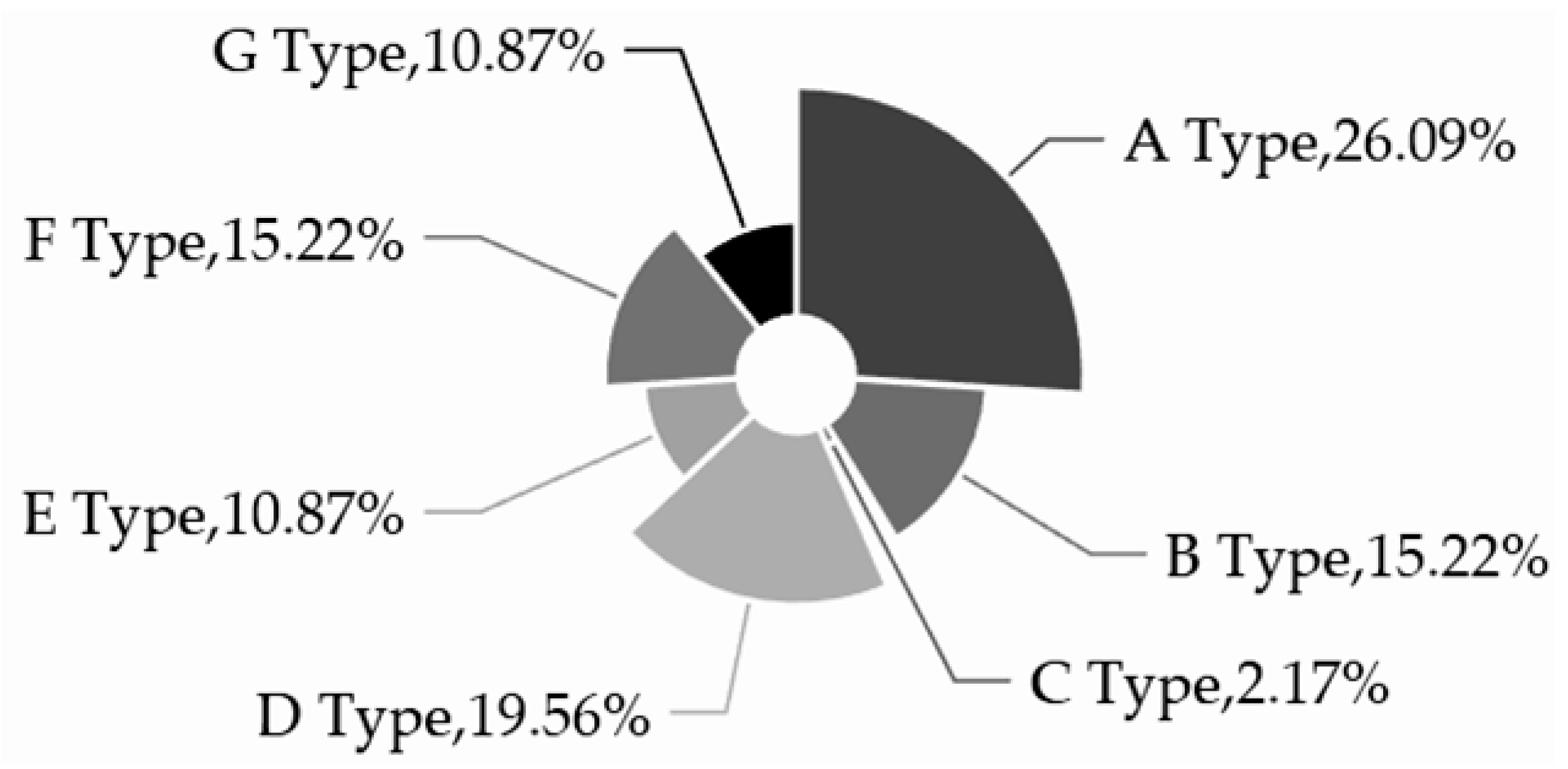

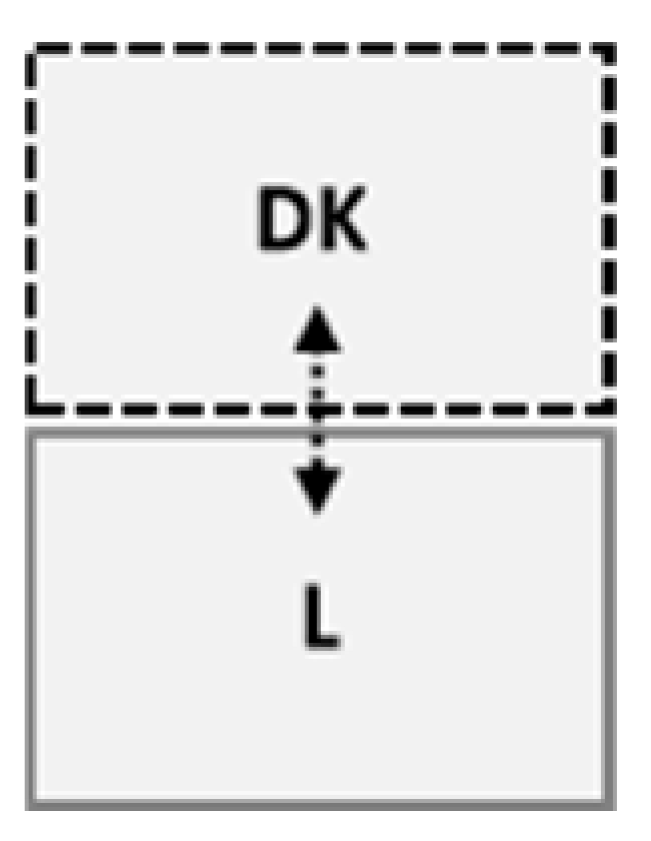

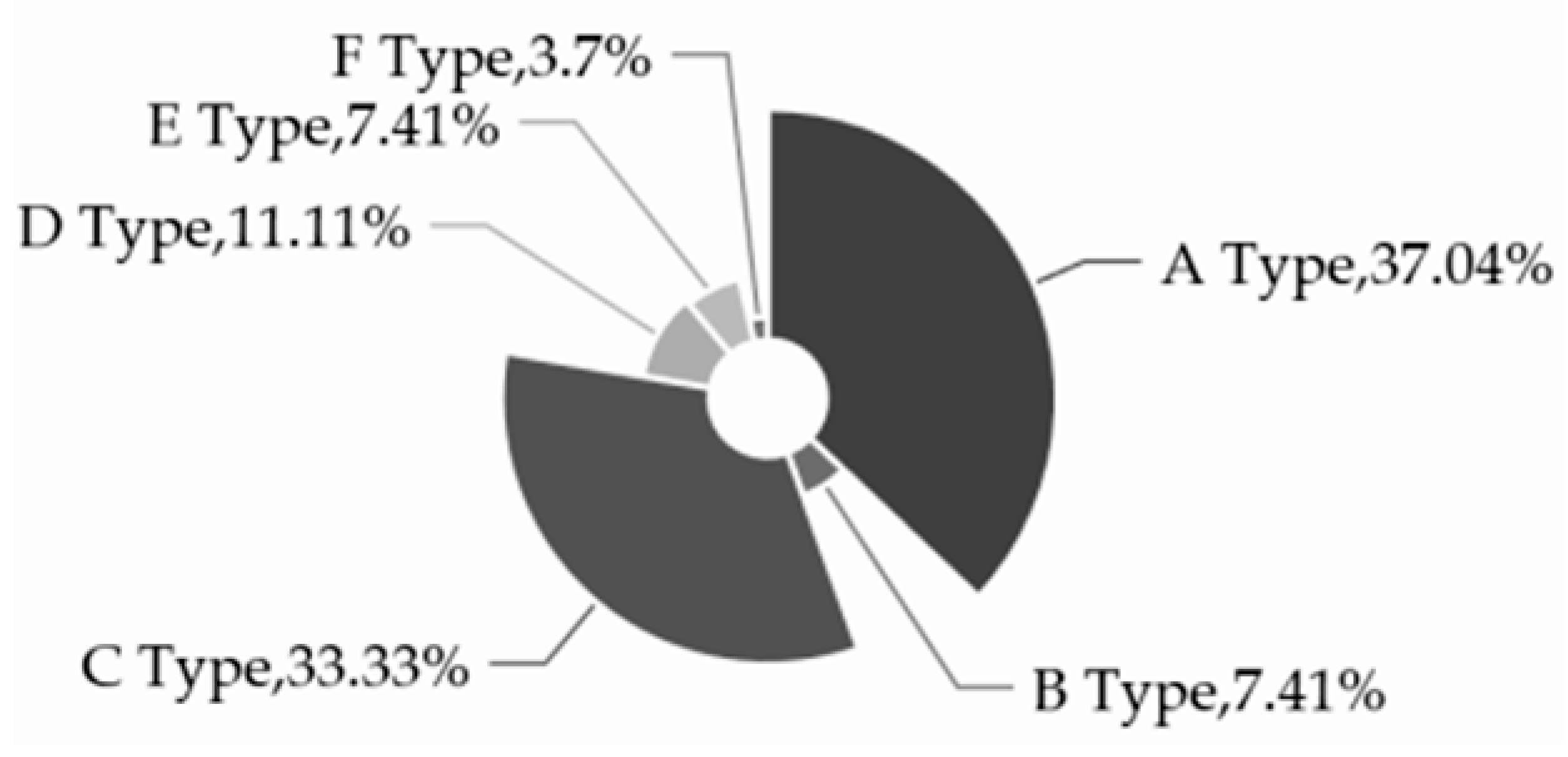

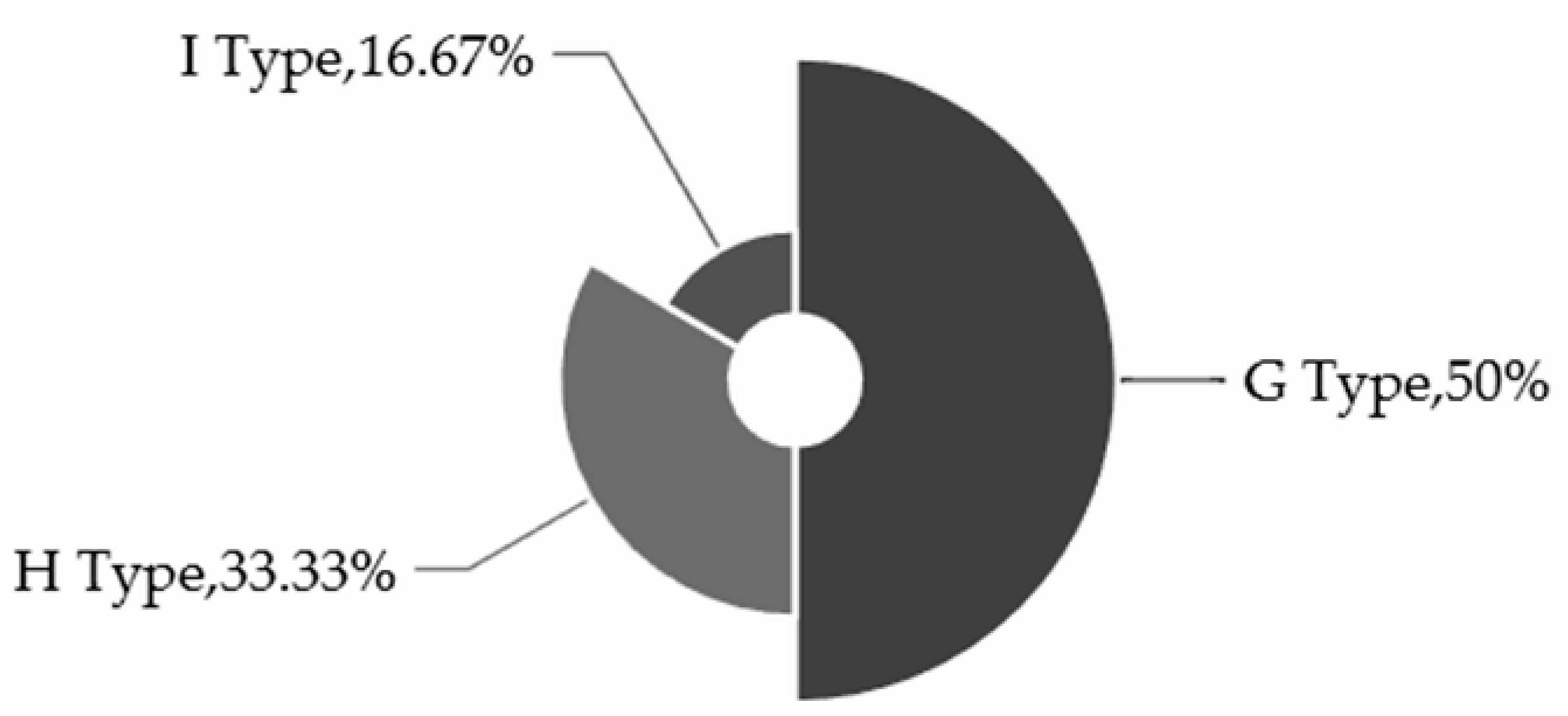

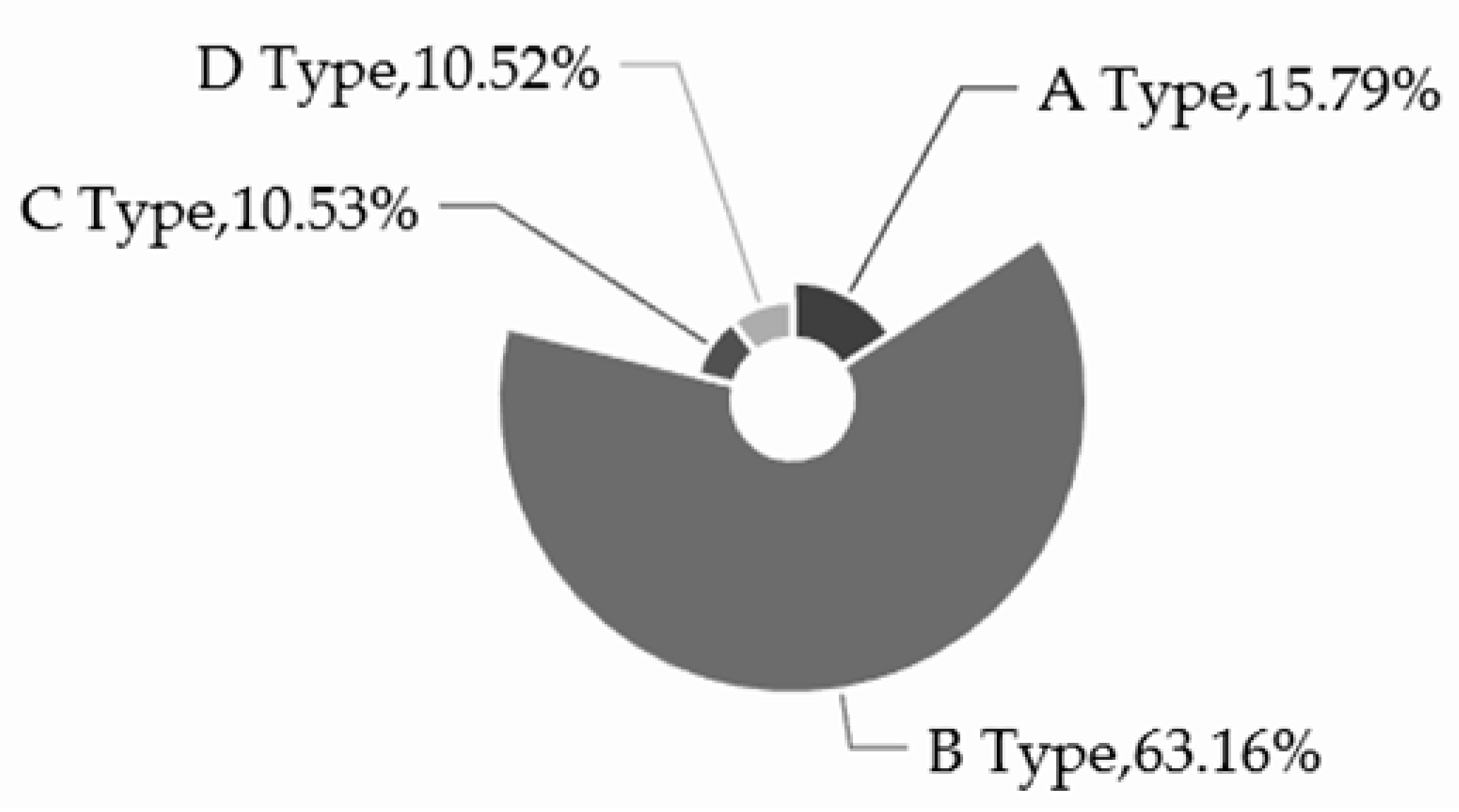

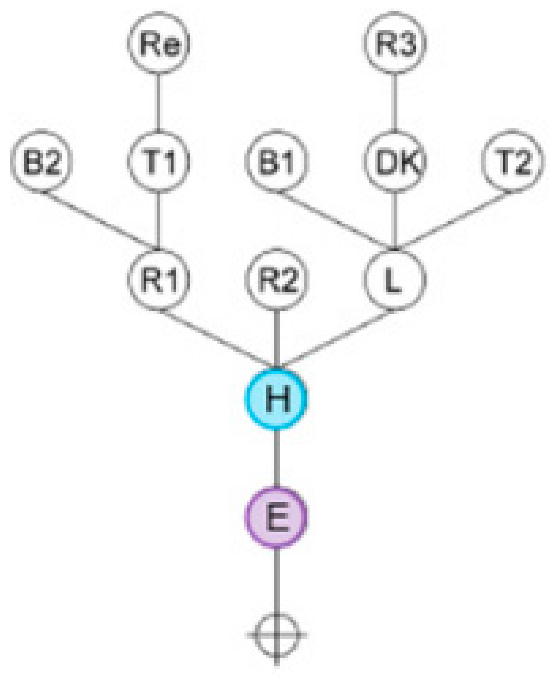

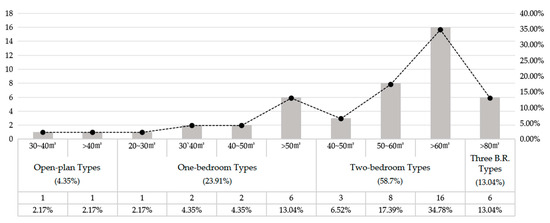

Taking the unit plans of permanent and national rental housing as an example, except for the P3 and P5, which have derived different types of unit plans totaling eight and seven, respectively, the types of unit plans for the remaining projects are all between four and five. In total, there are 46 types of unit plans in the nine research projects. The average usage frequency of the unit plans in each project varies slightly, ranging from 68 to 300 households, but most projects remain between 120 and 130 households, which is relatively close to the average value of 131 households in the overall research cases. The unit plans include four types: open-plan type, one-bedroom type, two-bedroom type, and three-bedroom type. The distribution of each type and the actual usage area are shown in Figure 3. Open-plan unit plans are extremely rare in South Korean public rental housing, mainly due to the consideration of different groups in the construction of public housing in South Korea. For example, through supply models such as Happy Housing or Youth Housing, more suitable open-plan or small-sized unit plans are provided for new members of society, single individuals, newly married couples, etc. Moreover, in the unit plan design of South Korean public rental housing, one can observe the design of unit plans for specific vulnerable groups to meet the living needs of the elderly population and those with accessibility requirements. This further highlights the positive attempts and efforts of South Korean public rental housing in elderly-friendly design and meeting individual needs. In addition, compared with Chinese public rental housing, the floor areas in South Korean public rental housing are more spacious, which further explains that while South Korea is committed to ensuring the supply of housing, it also strives for a high-quality living environment.

Figure 3.

Distribution of unit plan types in analysis cases.

4. Spatial Composition Characteristics of Unit Plan Cases

Based on the above analysis of architectural features, this study focused on systematically and comprehensively exploring and analyzing the spatial composition characteristics of the unit plans of public rental housing in South Korea from multiple dimensions, such as form features, functional spaces, flow organization, and structural zoning. The aim was to reveal the design concepts and spatial organization logic behind them [40,41,42,43].

4.1. Morphological Features of Unit Plans

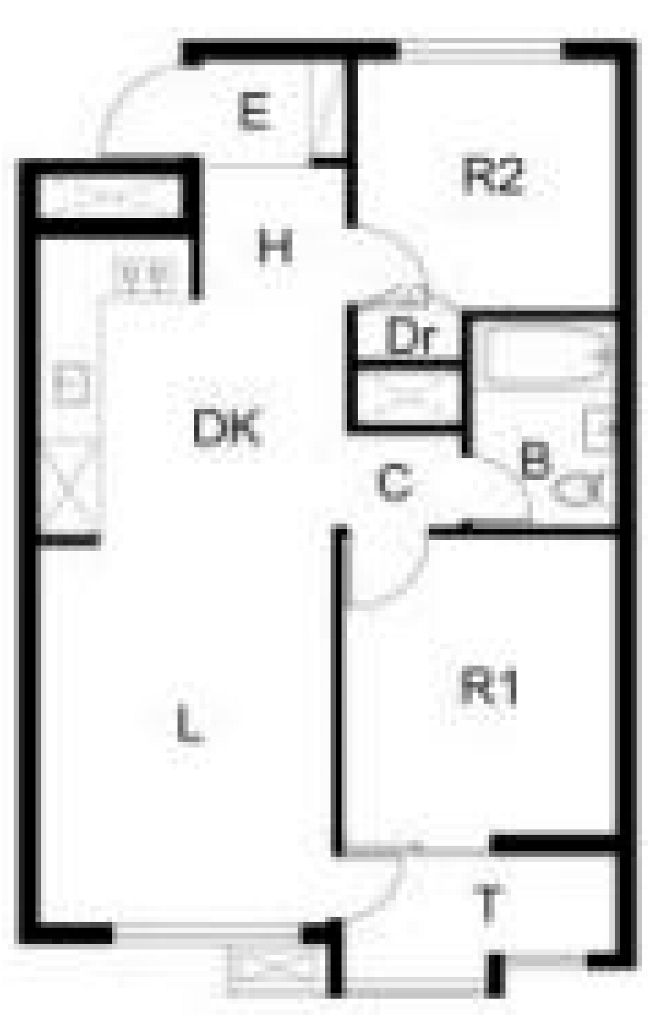

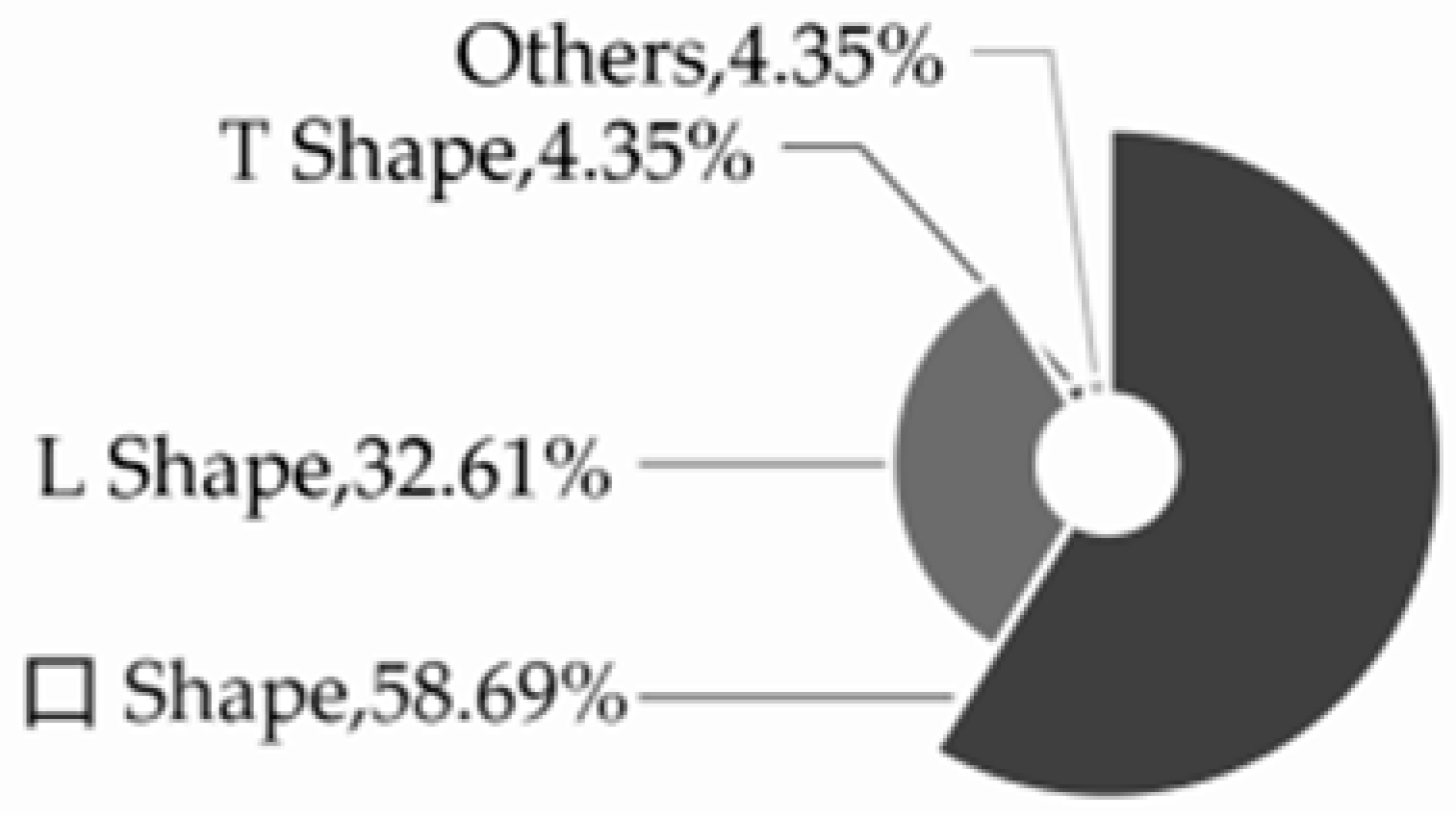

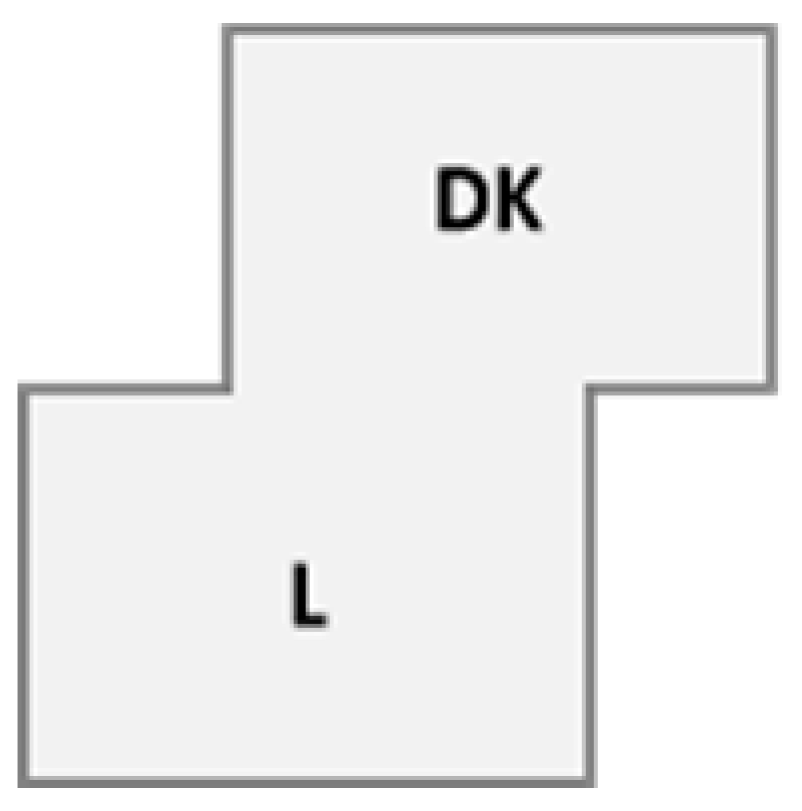

As shown in Table 2, the unit plan layout of permanent and national rental housing in South Korea mainly presents as a “☐” shape, “L” shape, “T” shape, or other irregular shapes. Through analyzing the unit plans of 46 research cases, it was found that among the “☐” shape unit plans, 19 were close to a rectangle, accounting for 41% of the total research cases; there were 15 “L” shape unit plans, which also occupied a considerable proportion. Following closely were the “☐” shape unit plans that were close to a square and elongated, each accounting for 9%. The number of other irregular-shaped unit plans was mostly between two and three, with similar proportions. The composition of these unit plan shapes reflects that South Korean residential culture is deeply influenced by the Chinese philosophy of “Heaven is round and Earth is square”, and the design of the living space pursues rectilinearity. Therefore, the unit plans are mostly composed of square-shaped living rooms, dining rooms, kitchens, bedrooms, and bathrooms. According to the combination of spaces and the layout of connecting corridors and other flow spaces, the unit plans present various forms. Among them, the “☐” shape and “L” shape unit plan forms are relatively common, while the “T” shape and other irregular unit plans occasionally appear due to building layout or lighting optimization and other design considerations.

Table 2.

Morphological features of unit plans.

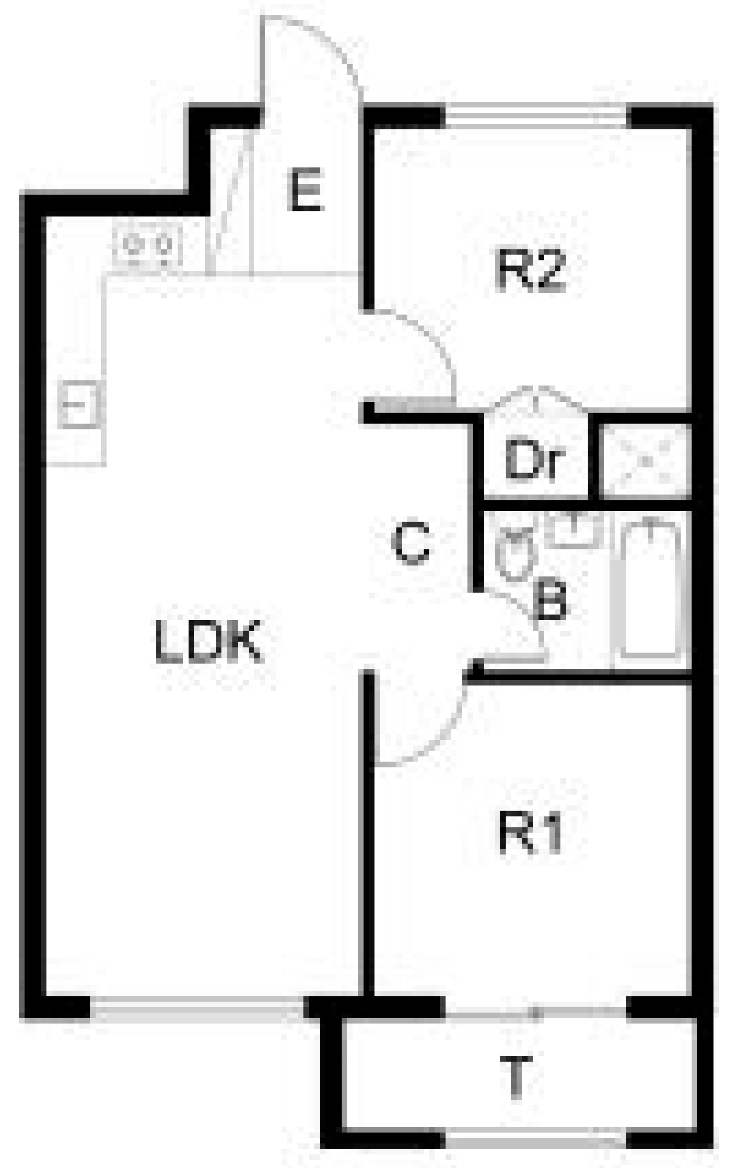

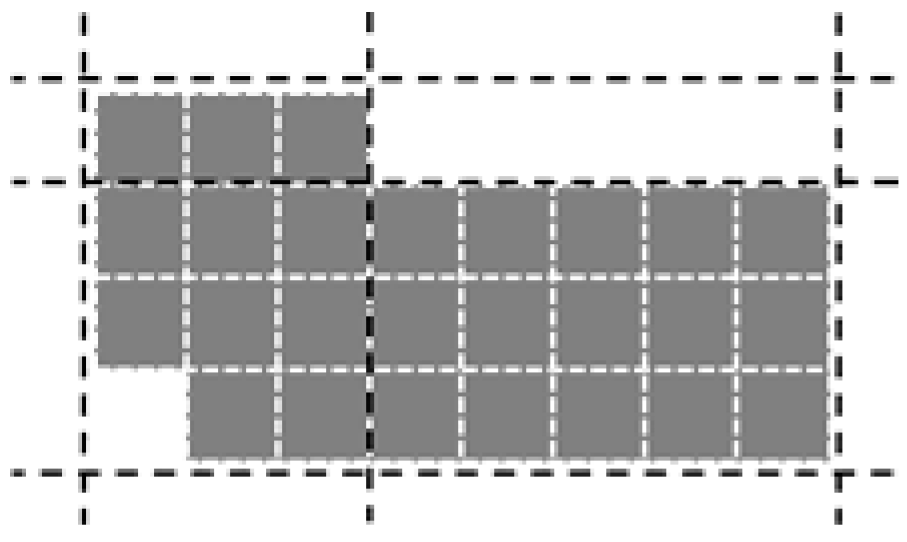

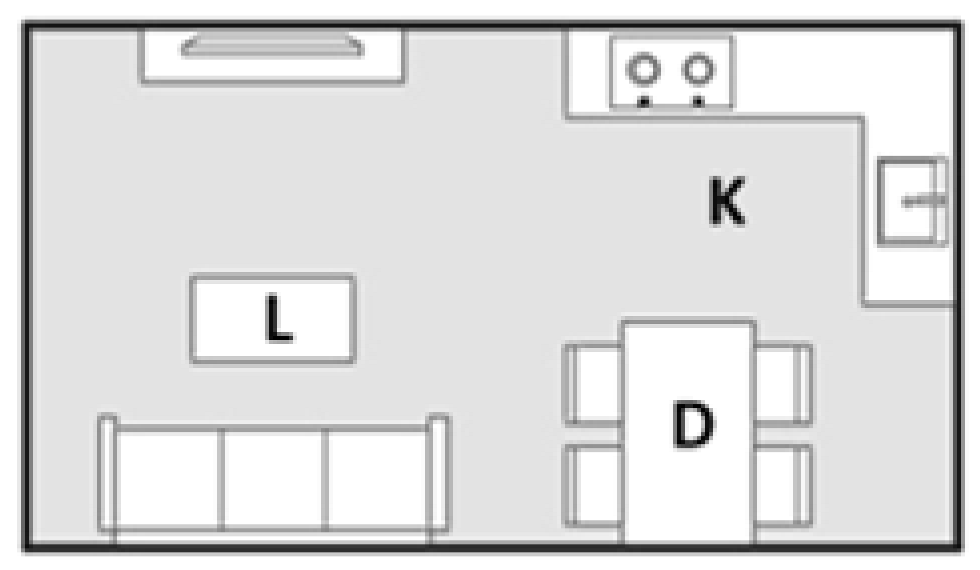

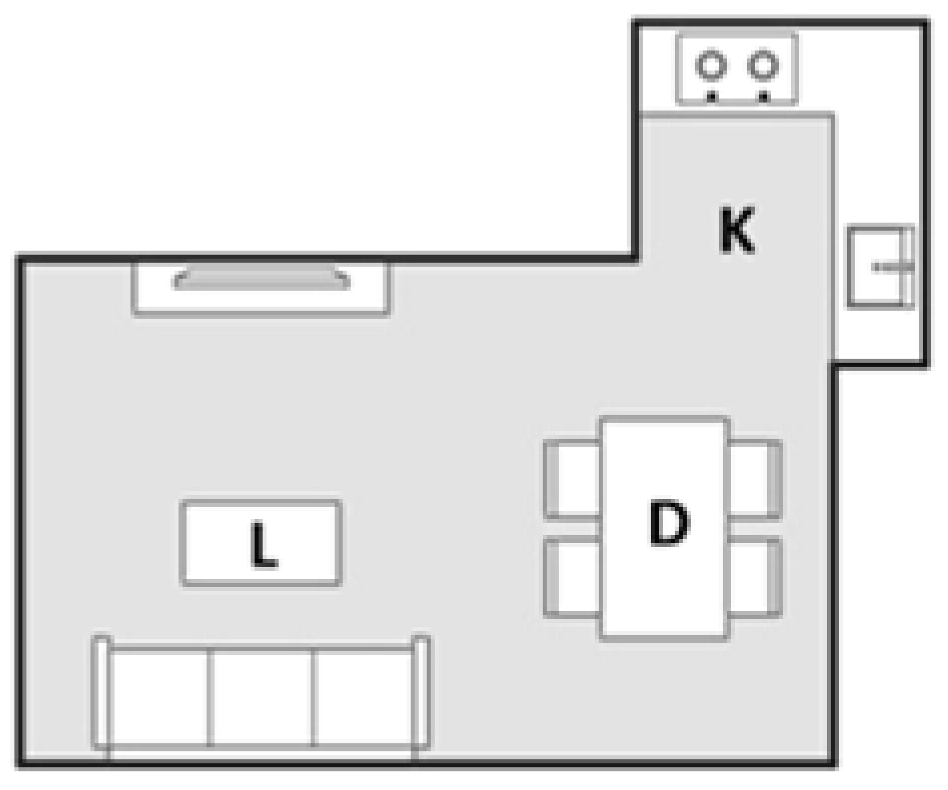

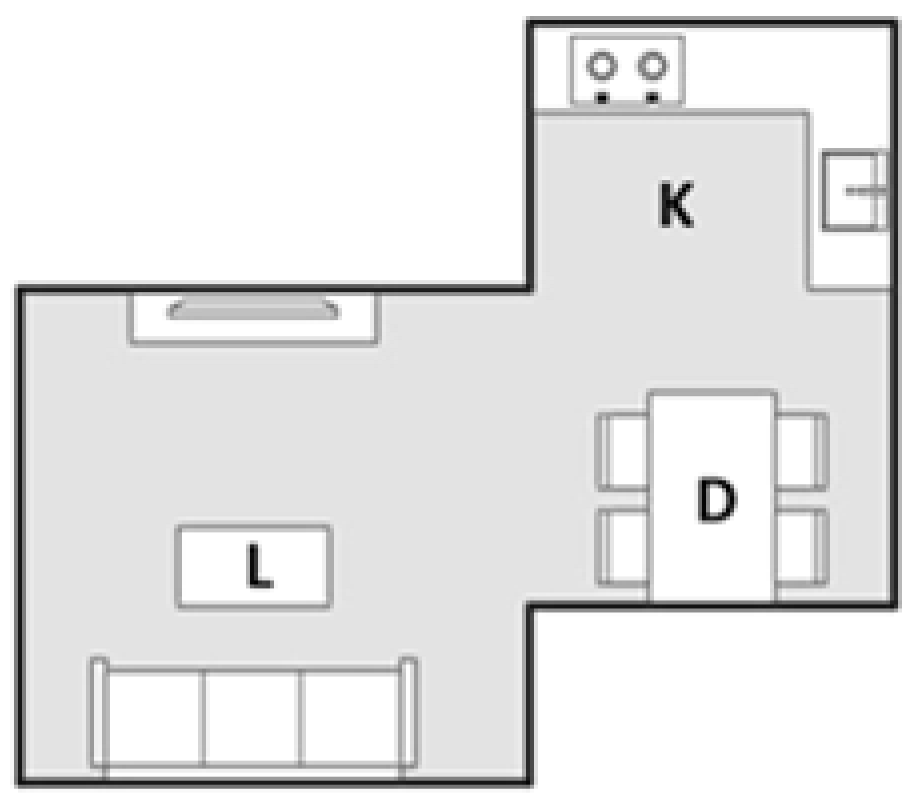

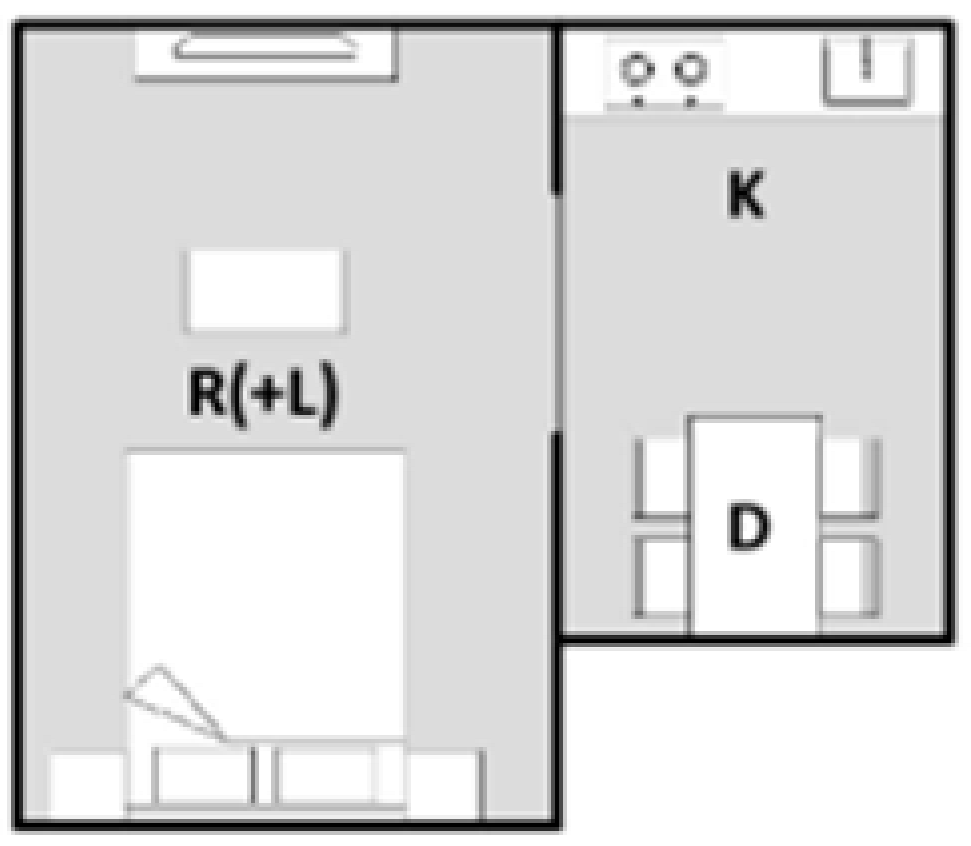

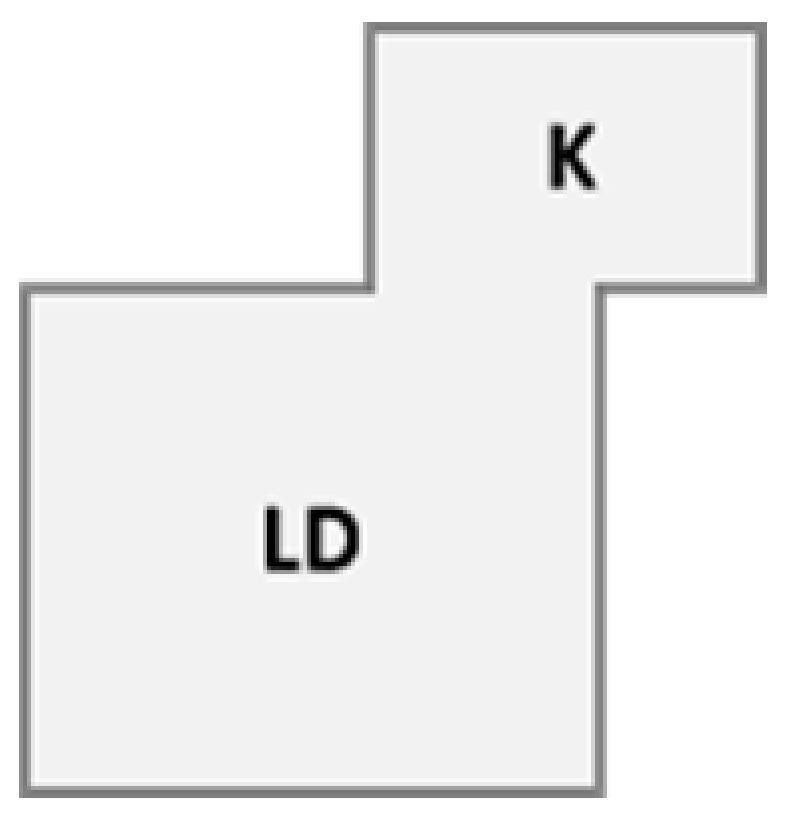

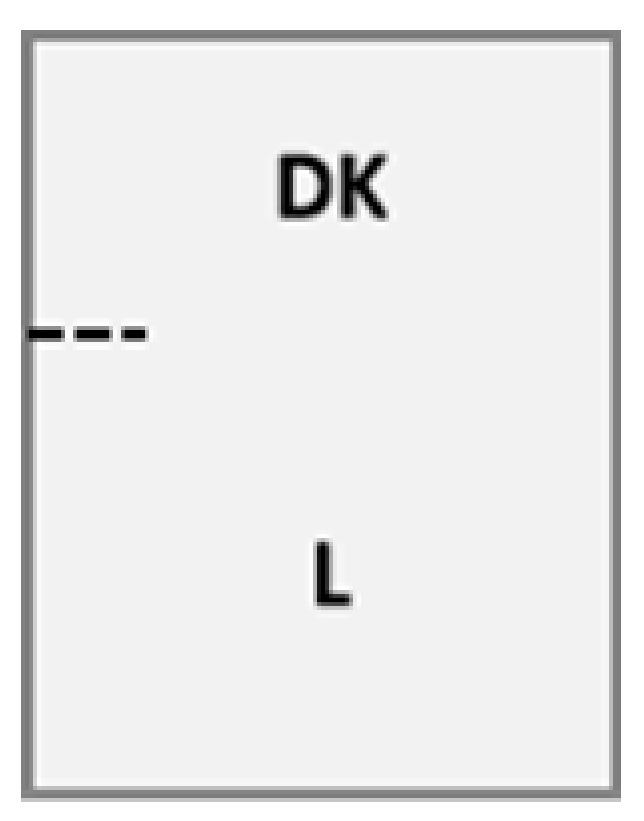

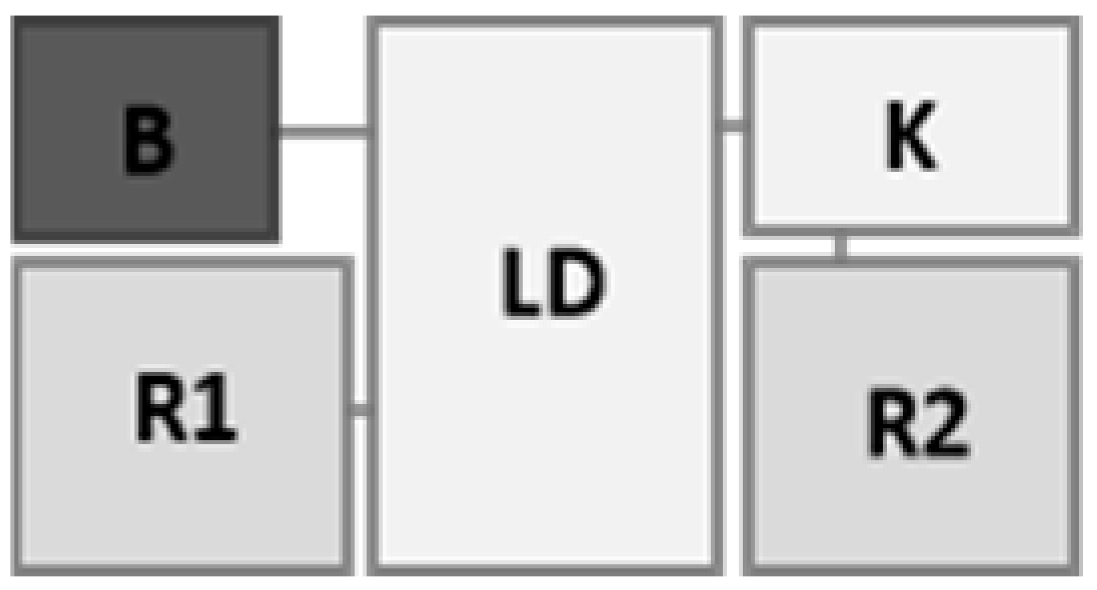

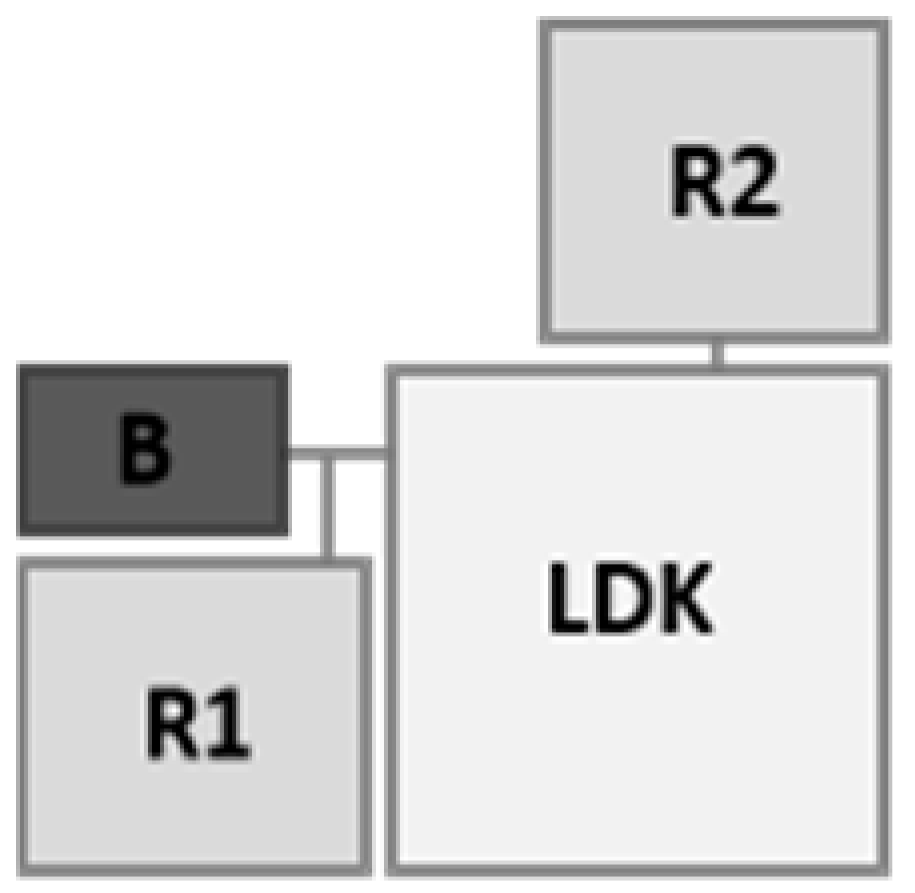

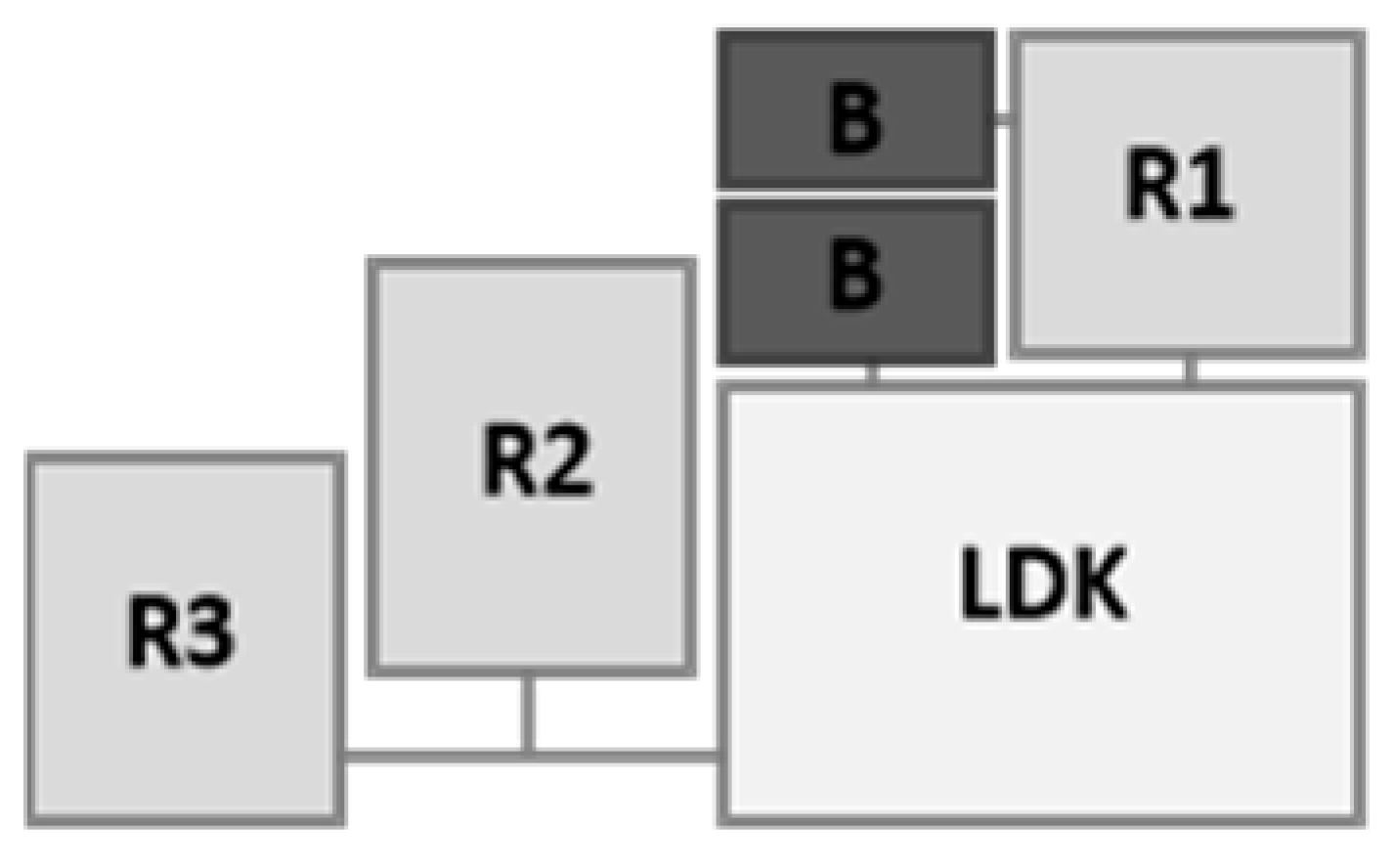

4.2. Combination Methods of L.D.K.

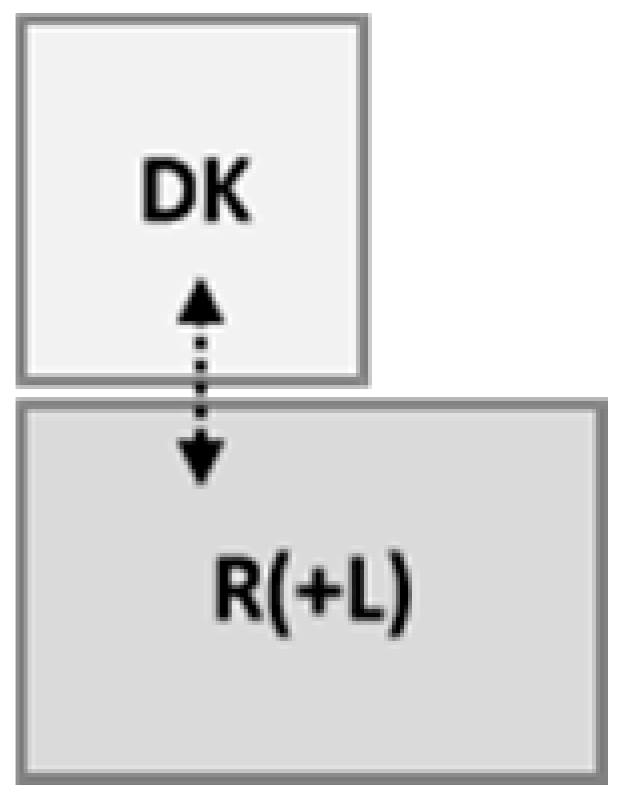

As shown in Table 3, the combination methods of L.D.K. can be divided into two major categories according to the type of kitchen: open kitchen and closed kitchen. Based on the layout and streamlined composition of the living room, dining room, and kitchen, an open kitchen can be further divided into five types: LDK, LD-K, L-DK, L-D-K, DK (L), while a closed kitchen is presented in the L/DK type. Among the 46 case house plans, the closed L/DK type accounts for approximately 11%, while the remaining 89% are open types. In open kitchens, the L-DK type and LDK type each occupy 15 and 12, respectively, totaling 58% of all unit plans, which are commonly applicable types. The DK(L) type and LD-K type each have seven and five, respectively, accounting for about 15% and 11%, respectively, which are relatively rare types. Finally, only two house plans adopt the L-D-K combination pattern, which is a relatively rare layout.

Table 3.

Combination methods of L.D.K.

When exploring the unit plan design of public rental housing in South Korea, the layout and streamlined relationships between the kitchen and living room become the key elements for analyzing different types of L.D.K. (living–dining–kitchen) configurations. By analyzing these two key factors, the combination methods of L.D.K. can be systematically classified (see Table 4). That is, the classification of open kitchens covers six types from A to F, plus one type of closed kitchen, totaling seven types. Among them, types A and D place all three functional areas within a rectangular space, presenting the most common layout pattern. Compared with the separation of the kitchen and the living room, as well as dining room spaces caused by the partition of the walls in D-type, the layout in A-type, where there are no partition walls between the three functional areas, is more common. B-type presents an L-shaped layout, where the living room and dining room space form a rectangle, while the kitchen, as an independent space, protrudes outside the rectangle to form an L shape. Among the 46 case unit plans, B-type occupies 7, which is a relatively common combination method. In C-type, the kitchen is separated from the dining room and overlaps with a corner of the dining room, forming a Z-shaped layout. In 46 cases, only 1 adopted this layout, which is a relatively rare combination. E-type and C-type have similar spatial forms, but in terms of spatial layout, the kitchen and dining room share the same space and are separated from the living room space. F-type does not have a separate living room space, but instead uses a larger bedroom as a living room. In G-type, the dining room and kitchen share a closed space and are completely separated from the living room. The three types of G, E, and F mentioned above have similar proportions to B-type and are all common combinations.

Table 4.

Layouts of kitchens.

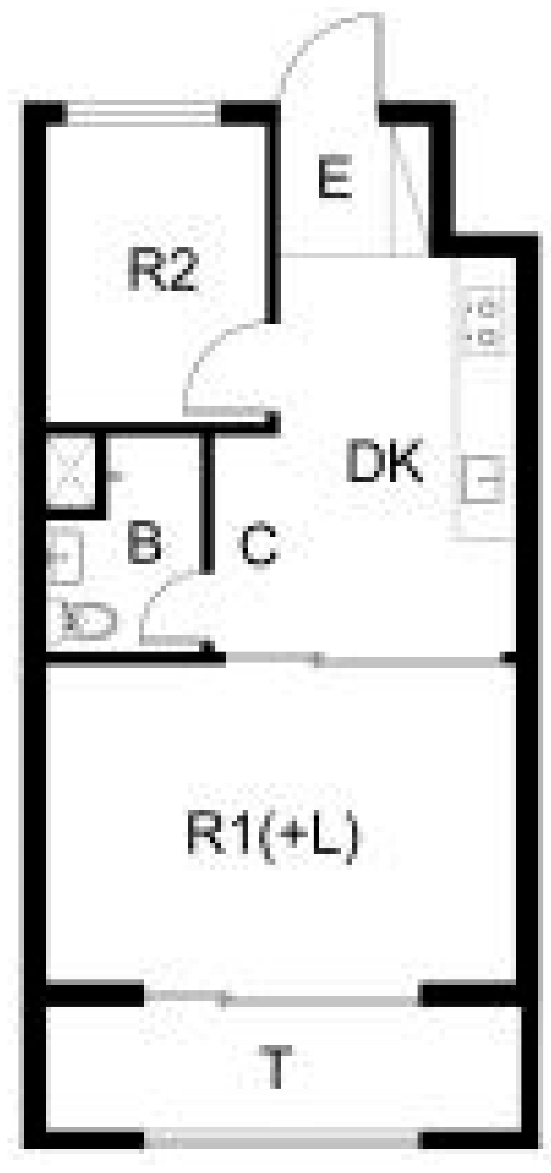

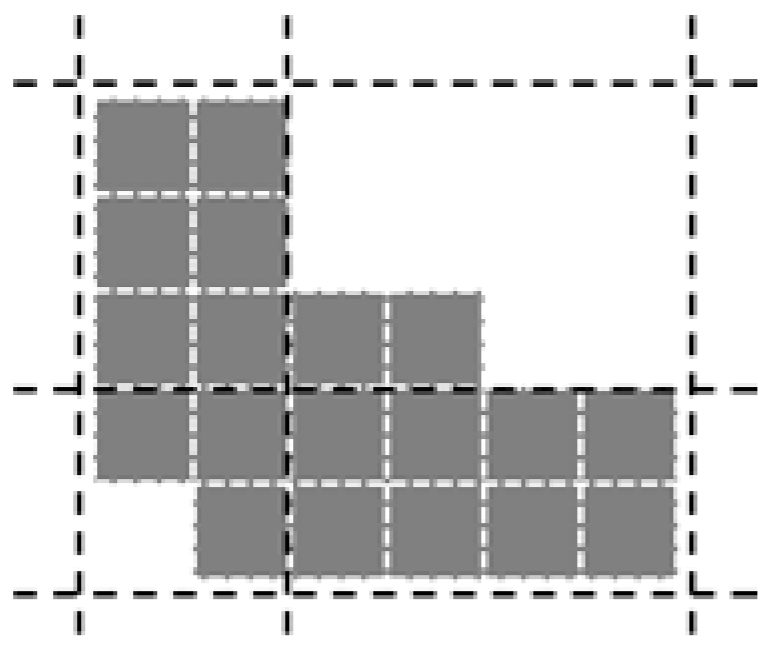

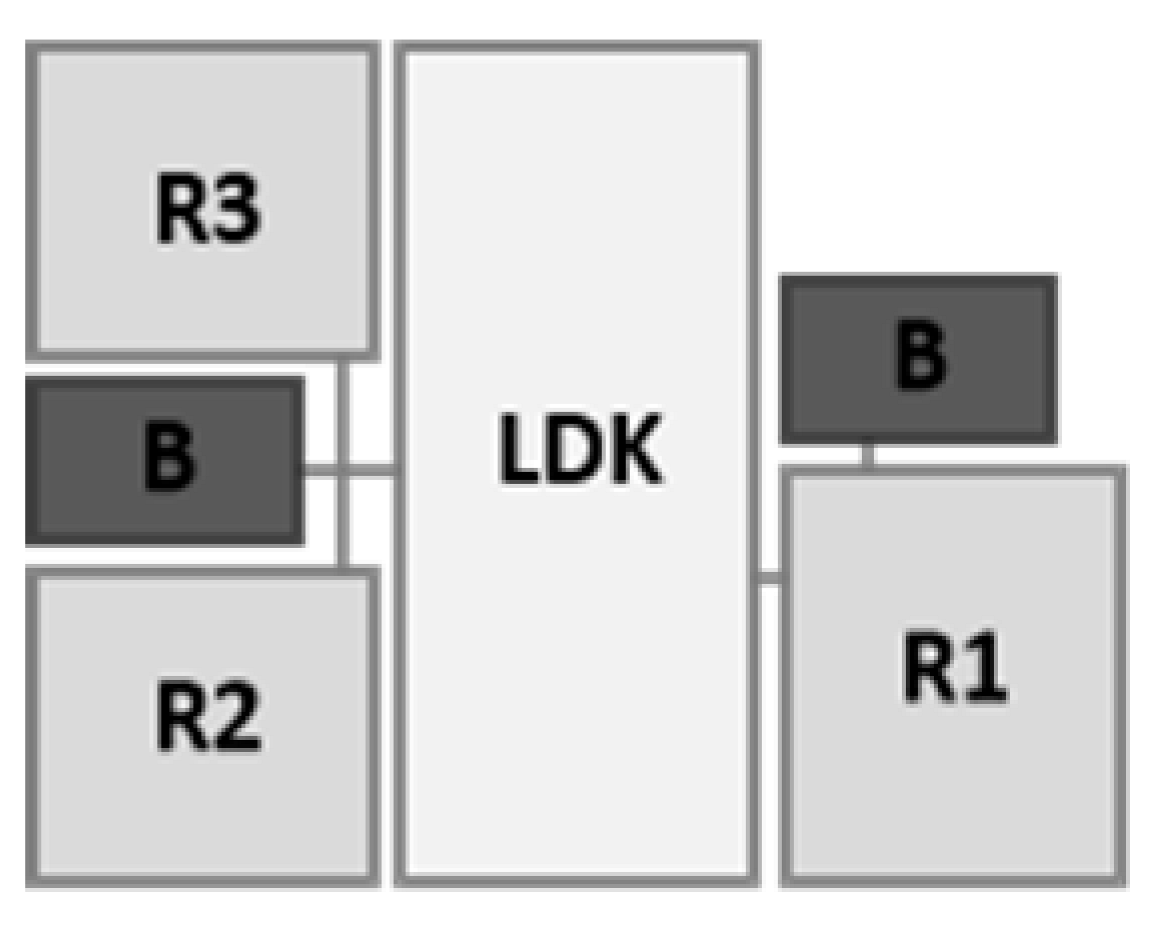

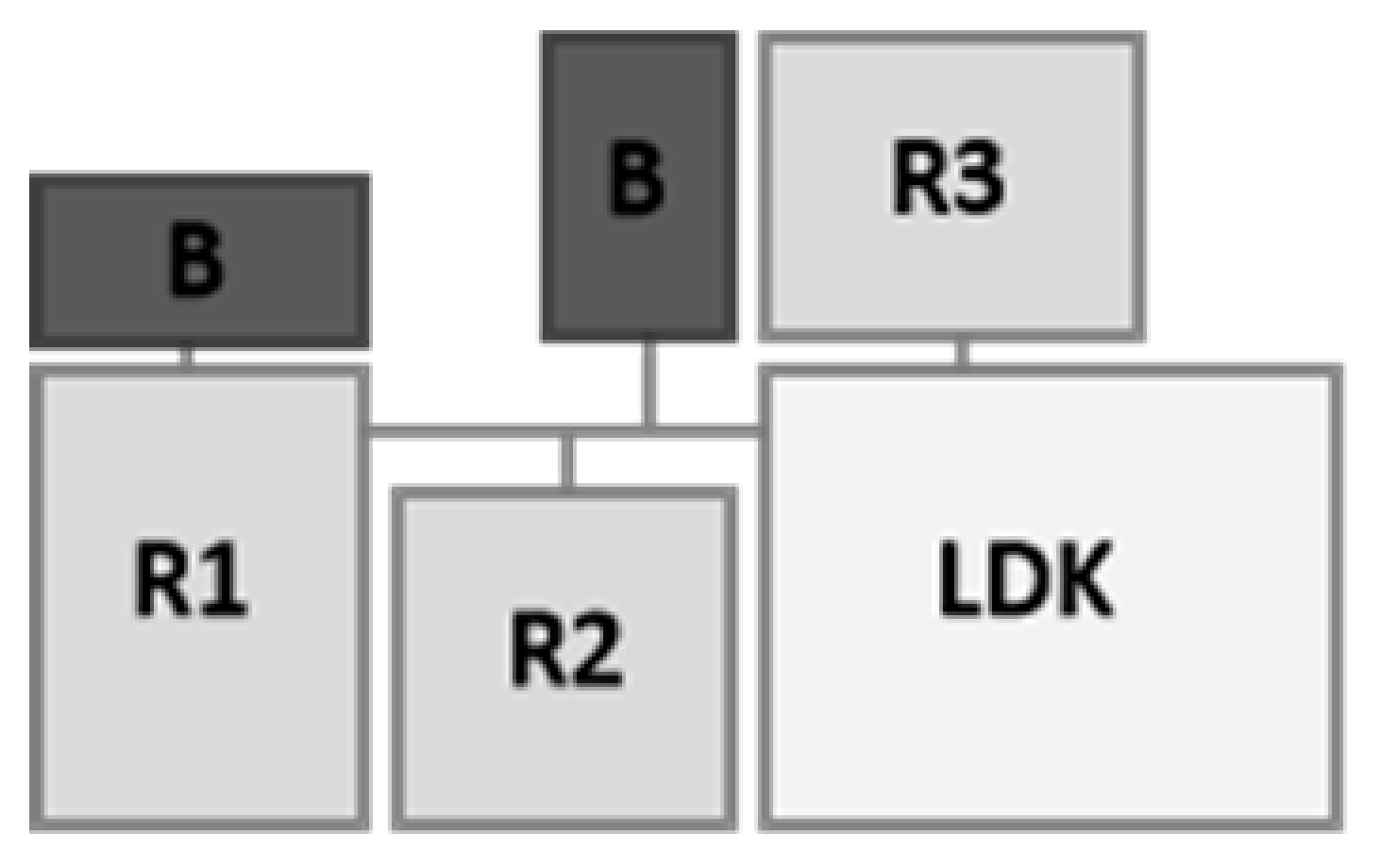

4.3. Configuration Strategy of Bedrooms

Among the 46 case unit plans, two-bedroom and three-bedroom layouts together accounted for approximately 72% of the total. Specifically, there are 27 two-bedroom layouts and 6 three-bedroom layouts. The two-bedroom layouts are all of the dispersed type and could be further categorized into six distinct combination forms (see Table 5). The three-bedroom layouts encompassed two main categories: dispersed type and mixed type. Among these, one was classified as a dispersed type, and two as mixed types, resulting in a total of three different combination methods (see Table 6).

Table 5.

Combination methods of 2 bedrooms.

Table 6.

Combination methods of 3 bedrooms.

Among the two-bedroom layouts, 19 are presented in types A and C. The two bedrooms are arranged around the bathroom and are separated from the living area. There are 10 of A-type, where all spaces, including the bedrooms and bathrooms, can be accessed directly from the living area. The other nine are presented in C-type, creating a transitional space between bedroom R1 and bathroom that serves as a corridor to reduce the streamlined distance and ensure the usable area of the living room. Types B and D are similar to types A and C, with two bedrooms arranged around the bathroom as the center. However, in types B and D, the bathroom and two bedrooms are arranged in an L-shaped layout together, so the relationship with the living room space is closer to the spatial structure surrounding the living room compared to separation. And these two types are applicable to two and three, respectively, and are relatively rare. B-type is similar to A-type in that all spaces can be directly accessed from the living room, while D-type is similar to C-type in that it relies on transitional spaces to achieve spatial streamline. In addition, E-type, with two bedrooms located on either side of the living room as the center, and F-type, located diagonally opposite the living room, are occasionally seen in permanent and national rental housing in South Korea.

The 50% proportion of three-bedroom layouts (including three unit plans) is typically represented by the G-type layout, where the three bedrooms are arranged in a triangular formation around the bathroom and the living room, and are completely isolated from each other. The other three three-bedroom unit plans adopt a mixed layout pattern, as shown in H-type and I-type, where two bedrooms are adjacent to each other, and the third bedroom is separated from them. The common features of mixed-type layouts are mainly manifested in the staggered layout of adjacent bedrooms, relying on a transitional space to achieve integration, while being separated from the third bedroom and centered around the living room, distributed on two adjacent facades.

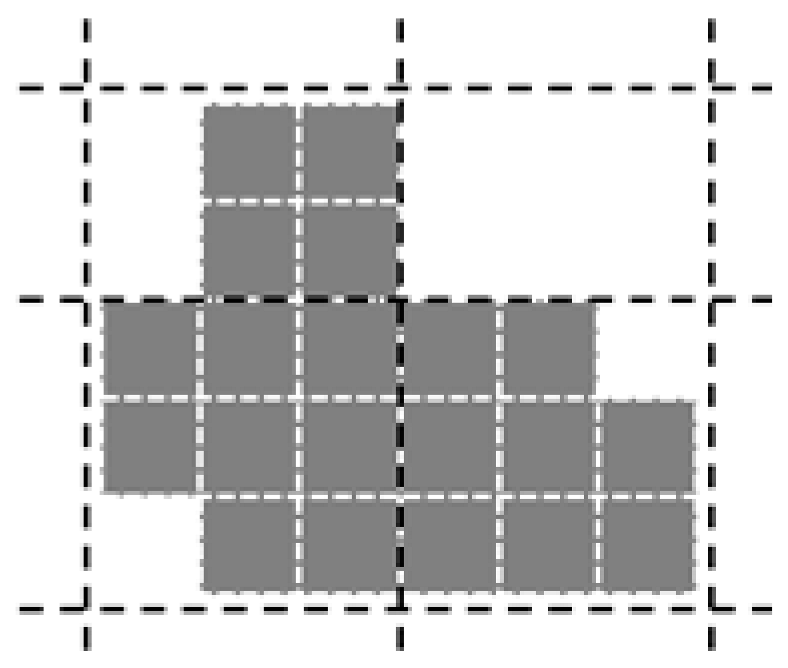

4.4. Role of Transitional Spaces in Spatial Integration

In the unit plan design of public rental housing in South Korea, the internal corridors and other transitional spaces are one of the prominent features. In 46 research cases, approximately 41% of the 19 unit plans had internal corridors, and the integration relationships of the various indoor spaces formed by these corridors as nodes are shown in Table 7. Among them, the B-type transitional space located between the bedroom and the bathroom was the most common, serving to integrate and connect the two spaces. Meanwhile, A-type, which is located between two bedrooms, C-type, which integrates and connects three spaces such as bedrooms, bathrooms, and kitchens, and D-type, which serves as a buffer space and as an independent space, are occasionally seen in permanent and national rental housing in South Korea. The comprehensive analysis indicates that, apart from serving as buffer zones for functional spaces such as bedrooms, kitchens, or bathrooms, most transitional spaces are mainly located between bedrooms, as well as between bedrooms and other spaces like bathrooms or kitchens, and they play a role in integrating the spaces. The setting of transitional spaces, as a strategy to shorten the internal flow distance of the living room, has certain advantages in ensuring the actual usage range and area of the living room.

Table 7.

Integration relationships by transitional spaces.

4.5. Other Spatial Configuration Characteristics

In the analysis of the balcony design of public rental housing in South Korea, this study revealed its unique spatial layout characteristics. By examining the unit plans of 46 research cases, it was found that balcony spaces were present in all cases. Specifically, 34 unit plans (accounting for 74% of the total) had balconies connected to the bedrooms, serving as drying areas. Additionally, nine balconies (accounting for 20%) were not only connected to the bedrooms but also to other spaces such as the living room, forming a composite layout. Only in two cases were the balconies connected to the living room, mainly due to the open-plan design of these cases, where the functions of the living room and bedroom were combined. From the analysis of the unit plan morphology, 87% of the balconies adopted an embedded design, interlocking with other spaces and forming a unified whole, while the remaining 13% of the balconies were of the protruding type, protruding beyond the building’s edge. This design differs from the common protruding balcony layout in China, reflecting the differences in living habits and cultural preferences between different countries. Moreover, in terms of bathroom design, although both South Korea and China tend to concentrate bathing, toilet use, and grooming functions in one space, the preference of South Koreans for the bath culture led to their bathrooms typically being equipped with bathtubs.

5. Spatial Structure Analysis

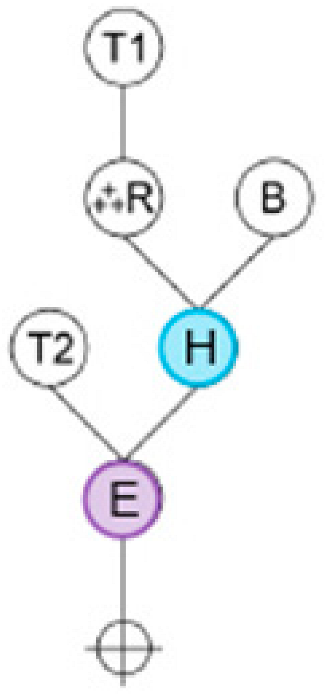

To further deepen and refine the systematic exploration of the spatial composition elements’ characteristics in the unit plans of public housing in South Korea, this study innovatively employs the J-Graph, a core analytical method from the Space Syntax Theory proposed by Professor Hillier (B.) and scholars such as Hanson (J.) from the Bartlett School of Architecture, University of London, in the late 1970s. By constructing a topological network model of spatial relationships, it conducts a quantitative analysis of the organizational structure and connection patterns of the spatial layout in South Korean housing unit plans [44,45,46,47]. Based on a scientific classification of the unit plans of public housing in South Korea, this study uses this spatial analysis method to systematically analyze the spatial structure features, circulation organization patterns, and functional zoning characteristics of different housing floor plans in South Korea from multiple dimensions, thereby revealing the inherent laws and unique attributes of the spatial composition of public housing floor plans in South Korea.

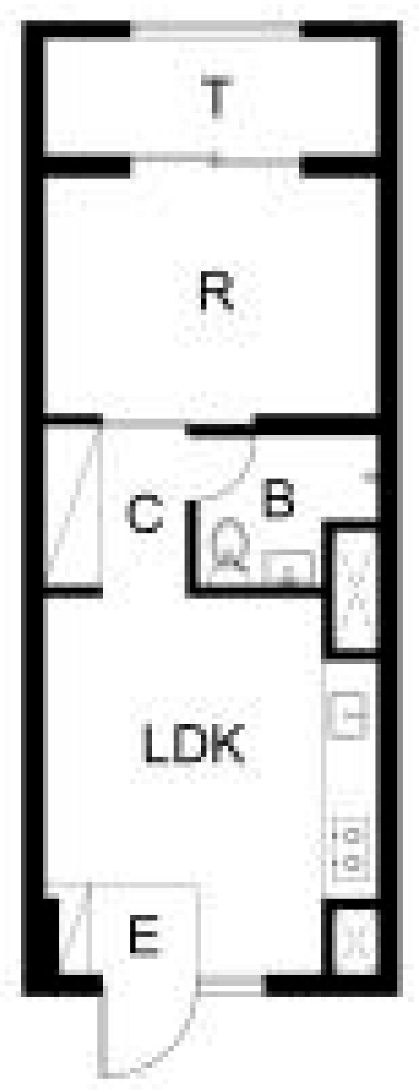

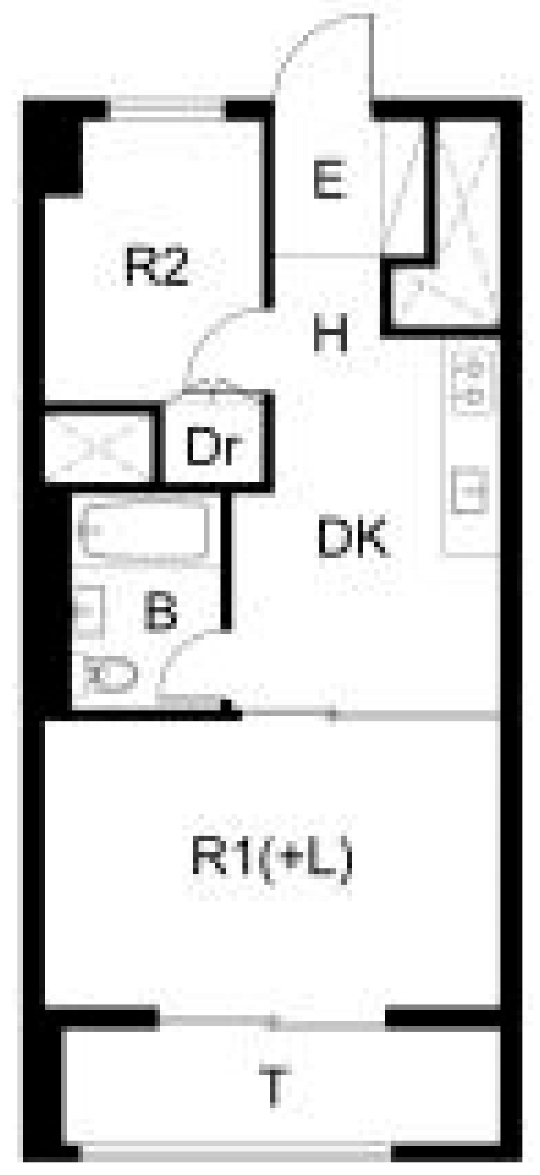

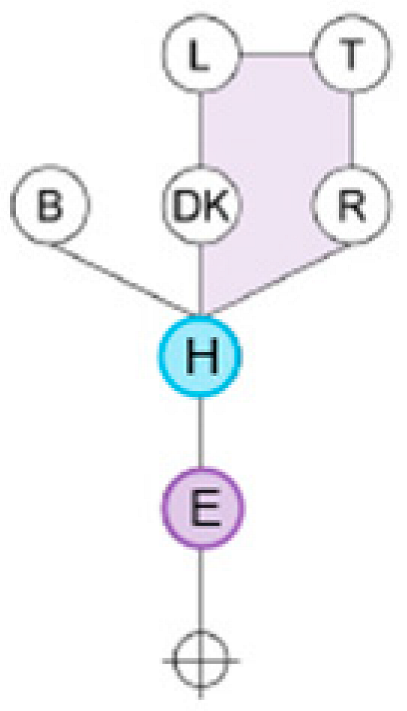

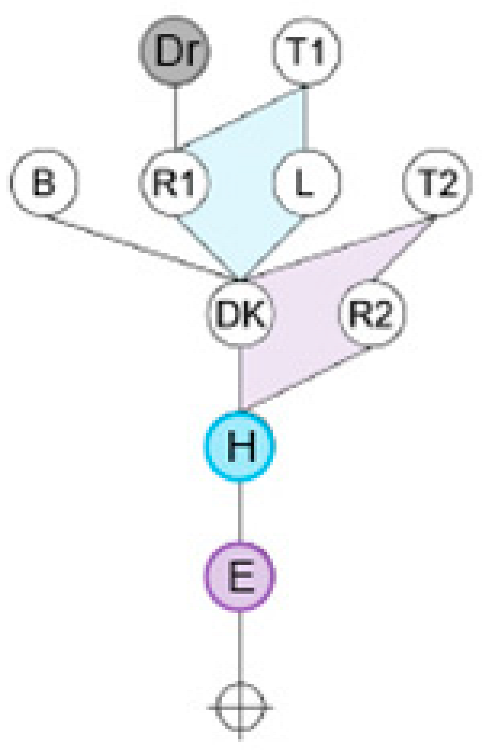

5.1. Open Plan Types

In South Korean public housing complexes, the open-plan type is a relatively rare type. Among the 46 unit plans, there are only 2 of this type, and both are applied in a single public housing complex. Analyzing from the depth level of the spatial structure, the values are 4 and 5, respectively. The reason for this numerical difference lies in the fact that the kitchen of one of the unit plans is separated from the living room, presenting an LD-K spatial structure. Therefore, the depth of this unit plan is relatively greater. The number of nodes in both unit plans is seven. One of the unit plans adopts the LDK layout, which differs from the independent kitchen layout of the other type. That is, this unit plan has two balconies, so the number of nodes in the two unit plans is the same. However, due to the difference in depth, the total depths are 16 and 19, respectively, and the mean depths are 2.67 and 3.17, respectively. The values have certain deviations. The relativized asymmetry (RA) of the space structures in the two unit plans is 0.67 and 0.87, respectively. Overall, the values are relatively high, indicating that both types have a strong tendency towards independence in terms of structural composition (see Table 8).

Table 8.

Spatial structural characteristics of the open plan types.

The minimum value of the connectivity is all 1, and most of them occur in the balcony and bathroom areas. The maximum value is all 3. One of the unit plan types has the maximum value at the entrance corridor, while the other has the maximum value at the kitchen. This structural difference is due to the fact that the former has an independent kitchen built between the entrance corridor and the living room, which forms a transitional space between these two spaces and also ensures the convenience of accessing the bathroom.

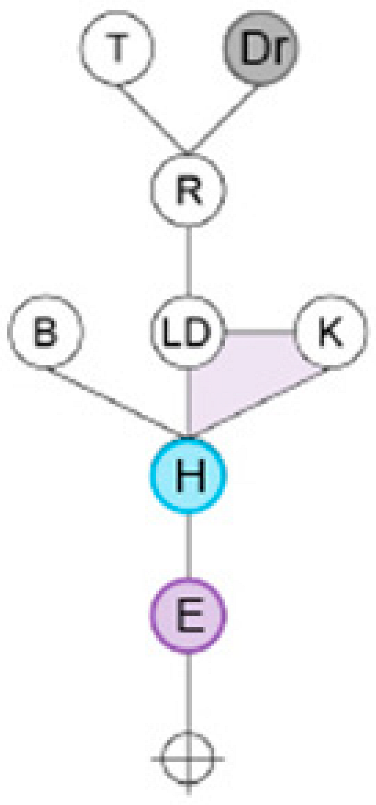

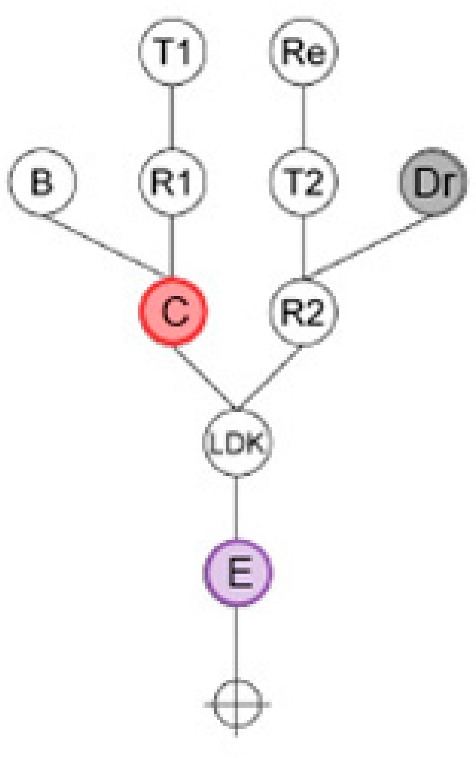

5.2. One Bedroom Types

There are a total of 11 units in the one-bedroom types. Among them, three units have a depth of 4, while the remaining eight units have a depth of 5 (as shown in Table 9). In the unit plans with a depth of 5, spaces such as the entrance, transitional space H or C, living room or dining room, bedroom, and balcony exhibit different depth characteristics in different unit plans. For instance, some units lack a transitional space, but due to the separate layout of the living room, kitchen, and dining room, the overall space depth is relatively large; conversely, some unit plans do have a transitional space H, but because the balcony is connected to both the living room and the bedroom, the overall space depth is relatively smaller. The number of nodes varies with values such as six, seven, eight, and nine. Among the 11 unit plans, 5 have a total node count of nine, 3 have seven, 2 have have, and 1 has eight. The characteristics of the unit plans with the least total node count mainly manifest as not having a living room space divided into independent areas, but instead using the form of bedrooms serving as living rooms; in the three unit plans with a total node count of seven, the entrance, bedroom, bathroom, balcony, and LDK spaces form transitional spaces, or present as separate L-DK structures; the unit plan with a total node count of eight uses transitional spaces to construct an independent L-DK spatial structure; while the remaining five unit plans with a total node count of nine also have multi-functional rooms or refuge spaces, in addition to the aforementioned spaces. The total depth of the one-bedroom types ranges from 13 to 27, presenting diverse numerical characteristics. If measured by the mean depth, the value of the two two-unit plans is 2.60, and one is 2.86, which is relatively low; the mean depth values of the remaining eight unit plans are all within the range of 3.00–3.38, showing relatively similar numerical characteristics. This is because the eight unit plans with a depth of 5 have similar numbers of nodes and spatial structures. The analysis results of the relativized asymmetry indicate that the values are all within the range of 0.62 to 0.87, with an average value of 0.73. This suggests that in the actual spatial structure, there is a preference for the separation of spaces.

Table 9.

Spatial structural characteristics of the one-bedroom types.

The minimum value of connectivity is all 1, and it mainly exists in bathrooms, balconies, as well as other service rooms such as multi-functional rooms, changing rooms, or refuge spaces. Among the 11 unit plans, the connectivity value of 4 units is 4, and for 7 units the value is 3, mainly appearing in transitional spaces H or C and the living room. This indicates that the spatial composition of the unit plans is centered around the living room and transitional spaces. Moreover, the research shows that in the unit plans of the same case project, there is a tendency to form the same or similar spatial structures. And in a one-bedroom unit plan in South Korea, a three-space circular route, such as “entrance corridor-kitchen-living room-entrance corridor”, and a five-space circular route, such as “entrance corridor–kitchen-dining room-living room-balcony-entrance corridor”, can be observed, indicating that there is a preference for space integration in the spatial layout.

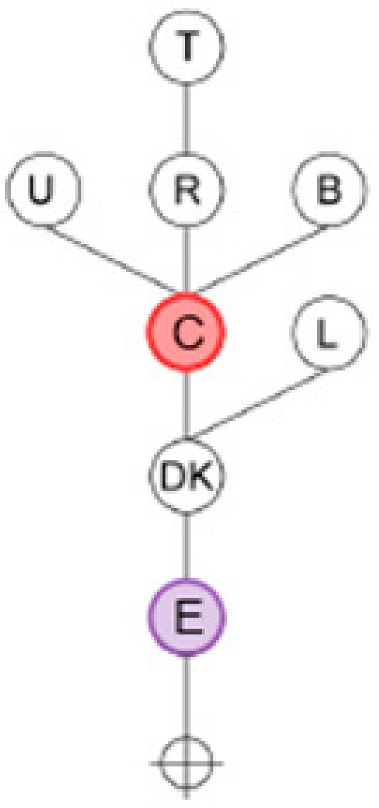

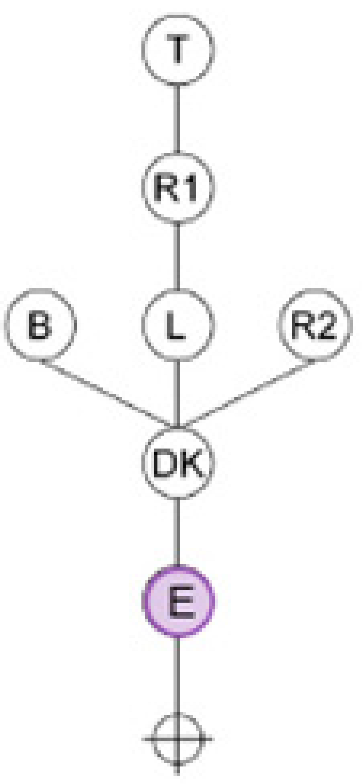

5.3. Two Bedroom Types

As shown in Table 10, among the 23 two-bedroom units, 10 have a depth of 4, while the remaining 17 have a depth of 5. The unit plans with a depth of 5 mostly fall into the category where both transitional space H and C coexist; some of the units have only one transitional space H or C, but they have a balcony at the deepest part of the unit plan, or the L.D.K. space is in a separate state. The unit plans with a depth of 4 can be roughly divided into two types based on the presence or absence of transitional space.

Table 10.

Spatial structural characteristics of the two bedroom types.

For those with transitional space, the number of transitional spaces is always one, and the L.D.K. is an integrated large space, thus the spatial structure depth is relatively shallow; for those without transitional space, they are mostly formed due to the integration of L.D.K., and in some unit plans without a living room, the DK space plays the same integrating function as L.D.K. The number of nodes varies between 7 and 11. Among them, the number of nodes for three unit plans is 7, for eight plans is 8 nodes, for seven is 9, for five is 10, and for four is 11. The reason why the number of nodes is diverse lies in the fact that, in addition to the basic spaces such as LDK, bathrooms, bedrooms, etc., it also involves factors such as the presence or absence of transitional spaces, the number of balconies, the combination form of LDK, and the presence or absence of other service spaces such as multi-functional rooms or refuge spaces. Moreover, the fact that most unit plans have an independent entrance is also a factor contributing to the relatively larger number of nodes. The total depth of the two-bedroom types ranges from 16 to 35, showing significant differences. However, the mean depth is within the range of 2.67 to 3.60, although there are some variations, they are generally similar. In some unit plans with a space structure depth of 7, the mean depth is within the range of 2.67 to 2.86, while the rest are above 3.00, close to the overall mean depth of 3.10. This indicates that the spatial composition density of all unit plans is similar. The relativized asymmetry is between 0.47 and 0.71, with an average of 0.60, which is relatively close to the benchmark value of 0.50. However, from an overall perspective, the spatial structure shows a feature of a separate layout.

The minimum value of connectivity remains 1 and is found in spaces such as bathrooms, balconies, bedroom 2, multi-functional rooms, refuge areas, and cloakrooms. Its maximum value appears as different numbers such as 3, 4, 5, and 6, mainly in areas like living rooms and D.K. rooms. In rare cases, it may also occur in evacuation spaces or secondary bedrooms. Based on this, it can be confirmed that the majority of the unit plans are centered around the living room or D.K. room. Among the 27 two-bedroom unit plans, 19 have the maximum connectivity value of 4; in the remaining 8, 4 have the maximum value of 3, and the other 4 have maximum values of 5 and 6, respectively. In the two-bedroom types, most of the units connect the balcony with the living room and one of the bedrooms. In some of the unit plans, there is a four-space circulation route consisting of “balcony-bedroom-living room-transitional space or DK room”. In certain unit spatial structures, a circulation route of “entrance-DK room-bathroom-secondary bedroom-” can also be found. Additionally, there are unit spatial structures that simultaneously feature a circulation route composed of “balcony-living room-bedroom-transitional space (C)” and a circulation route consisting of “living room-transitional space (H)-kitchen and dining room” with three spaces. Some unit plans also present a circulation route consisting of “balcony-living room-kitchen-dining room-transitional space (C)” with five spaces.

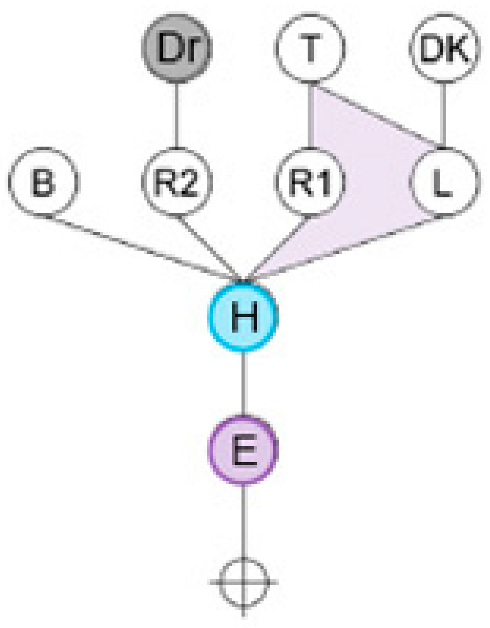

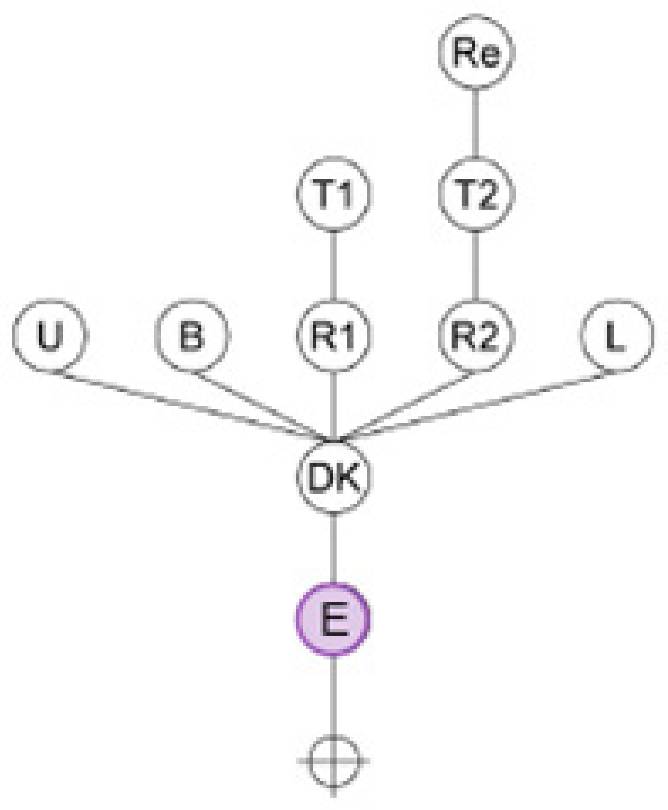

5.4. Three Bedroom Types

Among the six three-bedroom unit plans, the depth of three units is 7, two are 6, and one is 5. Among them, the unit plans with a depth of 7 all belong to the type that simultaneously have transitional spaces H and C; the unit plans with a depth of 6 only have transitional space H, while the unit plans with a space depth of 5 have a balcony and refuge space, but one of the bedrooms and the living room are arranged separately on both sides around the entrance corridor, resulting in the shallowest space depth. The number of nodes is roughly within the range of 13 to 15. Among them, the number of nodes for the four unit plans is 14, while the number of nodes for the other two unit plans is 13 and 15, respectively. The formation of this spatial structure is mainly due to the presence of an entrance corridor at the entrance, and this unit consists of a living room, three bedrooms, two bathrooms, two balconies, a refuge space, and an independent L-D-K space layout. Therefore, the number of nodes is relatively large. In the unit with a total of 15 nodes, there are transitional spaces H and C, and three balconies, while in the unit with a total of 13 nodes, there is only one transitional space and two balconies, so the number of spaces is relatively smaller. The total depth of the space structure for each unit plan varies within the range of 42 to 60. In terms of mean depth, except for one unit plan whose mean depth is 3.50, the mean depth of the other 5 unit plans ranges from 3.92 to 4.29, showing similar values. This can be inferred that the space structures of most unit plans have a high degree of similarity. The unit plan with a mean depth of 3.50 is mainly due to the layout of the master bedroom and the living room centered around the entrance corridor, resulting in a two-way dispersed structural form for the space layout. The relativized asymmetry is mainly distributed between 0.45 and 0.53, and a value close to 0.50 indicates that, compared to other unit plans with fewer bedrooms, the design of the three-bedroom unit plan pays more attention to the integration of space rather than isolation (see Table 11).

Table 11.

Spatial structural characteristics of the three bedroom types.

The minimum value of connectivity is all 1, and it is mainly distributed in areas such as bathrooms, balconies, bedroom 2, bedroom 3, refuge spaces, and kitchens; the maximum value is 4 for all, and it appears in transitional spaces H as well as public areas such as living rooms and dining rooms. Among them, two unit plans are derived due to different entrance positions, so they present the same spatial structure. The maximum connectivity value simultaneously appears in the entrance corridor, dining room, and living room; in one unit plan, two bedrooms are simultaneously connected to the entrance corridor, and the living room is also simultaneously connected to the bathroom, kitchen, and balcony. Therefore, the maximum connectivity value simultaneously appears in the entrance corridor and the living room; in the maximum connectivity values of the other three unit plans, two appear in the entrance corridor, and one appears in the living room.

6. Insights for China’s Affordable Housing

Under the national policy guidance that emphasizes “accelerating the establishment of a housing system integrating renting and purchasing, and strengthening the construction and supply of affordable housing,” as well as the clear statement in the “14th Five-Year Plan” that positions the promotion of affordable rental housing construction as the core of development, and calls for further optimization of the housing security system and expansion of affordable housing supply, regions across the country have significantly intensified their efforts in affordable housing construction and actively issued a series of policies and regulations concerning its development and supply. However, during the actual implementation process, there are still problems such as tight land resources, insufficient capital investment, as well as issues in the housing supply sector, including a single supply model, limited coverage, incomplete distribution mechanism, poor operation management, and insufficient collaboration between the state and society [48,49]. Particularly in the current strategic context, where the country advocates positioning affordable housing as “better housing” that is safe, comfortable, green, and intelligent, optimizing the affordable housing supply system and constructing units that meet these “better housing” standards have become pressing issues. Therefore, studying the public housing supply system and its unit plan spatial characteristics in South Korea holds significant reference value [3].

6.1. Construction of Policy System

Since the early 1960s, when South Korea officially implemented the public housing policy, a variety of supply institutions and models have given rise to multiple forms of public housing, establishing a current extensive and diversified public housing supply system that provides suitable housing models for different groups with diverse needs, and has formed a “housing welfare roadmap” to ensure the stability of housing for disadvantaged groups. Based on this, strategic guiding suggestions such as “refining supply types, expanding supply scope, and optimizing supply models” can be proposed for the development of China’s affordable housing [7,9,12]. For example, the diversified rental housing model implemented in South Korea for different groups can be referenced. Based on factors such as the age, salary level, social status, and family structure of the residents, the current single public housing supply model in China can be refined into various rental housing types, and a hierarchical supply mechanism can be constructed. At the same time, models such as Youth Housing and Happy Housing in South Korea can be drawn upon to guide the active participation of private enterprises and social institutions, and a public rental housing system jointly managed and operated by the state, society, and private enterprises can be established to meet the housing needs of single young people, new social members, newly married couples, etc., at the middle and above income levels, so as to increase the proportion of rental housing in the housing market, expand the supply scope, and achieve the matching of demand and supply. In addition, to ensure the timely identification of public housing needs and the optimization of the rental housing supply system, the Korean housing welfare assembly map can be referenced to establish a demand warning system for affordable housing that suits China’s national conditions, and improve the dynamic adjustment mechanism.

6.2. Spatial Composition of Unit Plans

The public housing system in South Korea fully takes into account the social and economic background of individuals and families, providing suitable housing areas and unit plan designs for different social classes. Particularly, the three-bedroom layout designed for multi-child families or families that need to support parents has not been widely promoted in China. However, with the adjustment of the family planning policy and the implementation of the three-child policy, China urgently needs to consider the housing security issue for multi-person families. Especially in the context of the “people-oriented, housing for all” era and the concept of building “better housing”, housing security should also provide corresponding unit types, areas, and functions according to different demand groups. Therefore, in the field of the unit plan design for affordable housing, attention should be paid to “increasing functional space, expanding usable area, and optimizing spatial layout”, and specific standards and formats should be formulated to meet the housing needs of different people, thereby constructing housing security with the standards of “better housing”, and achieving the standardization and normalization of the design of affordable housing living space. For example, for the specific needs of families with triplets, this study suggests limiting the expansion of the traditional 60-square-meter two-bedroom layouts to 80-square-meter three-bedroom layouts, or even considering designing large unit plans similar to that of commercial housing, aiming to provide short-term rental housing for the transitional population in cities, ensuring the comfort and stability of their living environment. In addition, drawing on the proportion experience of the mainstream unit plans of public housing in South Korea, formulate a guidance principle for the unit plans of affordable housing that is in line with China’s living habits; refer to the L.D.K. open kitchen layout mode, emphasize the continuity and integration of space in the unit plan design of affordable housing, construct a north–south transparent indoor space to promote air circulation and ventilation effects, and thereby achieve the goal of low-carbon and environmentally friendly construction [8,30,31,50]. At the same time, draw on the design concept of transitional spaces and effectively shorten the indoor activity path, as well as optimize the separation of public and private spaces, to meet the diverse living needs of residents. In addition, the universally accessible bathroom design in South Korean public housing provides a useful reference for addressing the elderly or disabled population’s adaptive living needs under the trend of population aging in China. In the design of affordable housing, give special consideration to the needs of the elderly or disabled population, design unit plans that comply with accessibility standards, and comprehensively consider the indoor space layout to ensure the reasonable construction of an indoor accessible streamline. In terms of spatial structure layout, South Korea’s public rental housing has seen an increase in the depth and mean depth of its spatial structure due to its diverse functional spaces and strong emphasis on living comfort. Meanwhile, in the unit plan of South Korean housing units, many circular circulation lines can be found, which further highlights the importance placed on the convenience of circulation lines in South Korean residential space design. Based on this, in the design process of China’s affordable housing, more consideration should be given to the correlation between functionally similar and life circulation-related functional spaces to enhance the integration of the overall spatial layout, thereby better meeting the needs of living comfort and convenience.

6.3. Cultural Adaptability

In the design of public housing in South Korea, the translation of traditional cultural elements has been well demonstrated. Specifically, the design of the sunken foyer (usually with a height difference of 150 mm) not only continues the traditional sitting culture but also introduces innovative elements such as anti-slip tiles, making the foyer space a transitional area that combines functionality and cultural identity. Moreover, the open kitchen design that adapts to South Korean dietary culture showcases the modern people’s pursuit of a minimalist composition in the living space; meanwhile, the decentralized bedroom layout and the embedded balcony design reflect the unique lifestyle of South Korea. These design elements and methods effectively demonstrate the cultural adaptability of the unit plan in South Korean public housing and, to a certain extent, achieve the standardization and normalization of the design of living spaces [8,30,50]. In contrast, the internal space dimensions and unit plan layouts in China’s affordable housing have many unreasonable aspects, which, to some extent, reveal that the design of the unit plan in China’s affordable housing has not yet met the requirements of the “better housing” construction standard. Based on this, the design of China’s affordable housing should start from the aspect of cultural adaptability, establish standards and norms for space design, and achieve the goal of “better housing” construction. For example, standardized designs such as the closed kitchen design inspired by the multi-oil and multi-smoke dietary culture, the independent shower space formed by the shower culture, and the tea room space reflecting the tea-drinking culture can be used to realize the cultural translation of the new Chinese-style living space and construct a “better housing” space that conforms to the living habits of Chinese people.

7. Conclusions

Against the backdrop of China’s ongoing emphasis on the construction and supply of affordable housing, as well as its active promotion of developing “better housing” within this framework, the mature public housing policy system and diversified supply models in South Korea, along with its extensive practical experience, offer significant reference value and implications for China’s affordable housing development. Most previous studies have shown a degree of uniformity in terms of disciplinary fields, research methods, methodology, and the presentation of results, and they have certain limitations. In contrast, this study takes an architectural perspective, combines the evolution of public housing policies and the cultural background of residence, and conducts research on the significant development of public housing in South Korea. Based on an in-depth analysis of the public housing policy mechanism in South Korea and the spatial composition characteristics of its housing layouts, guiding suggestions for the development of China’s affordable housing have been proposed, which are characterized by “policy-space-culture” integration. At the policy level, it is recommended to establish a multi-tiered supply mechanism and implement an early-warning system for emerging affordable housing demands. At the spatial design level, standardization and modularization of housing design are advocated. At the cultural level, it is suggested to enhance cultural adaptability by aligning housing design with local residential culture and residents’ living habits. Through these integrated strategies, the goal of constructing affordable “better housing” that is safe, comfortable, green, and intelligent can be more effectively realized. To further validate the outcomes of this research and actively promote the practical application of these results in the pilot projects, the subsequent work of this study is currently being carried out comprehensively and deeply from multiple sustainable dimensions. Specifically, these dimensions include the analysis of social and cultural impacts, the optimization discussion of urban renewal strategies, and the exploration of the application of digital design and artificial intelligence technologies in practice. Through this multi-dimensional integrated research, the aim is to ensure the practicality and forward-looking nature of the research outcomes and provide strong support for the sustainable development of related fields.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.-R.W.; Methodology, X.-R.W.; Validation, X.-R.W.; Formal analysis, X.-R.W.; Investigation, X.-R.W.; Resources, X.-R.W. and B.-K.J.; Data curation, X.-R.W.; Writing—original draft, X.-R.W.; Writing—review & editing, X.-R.W., L.-P.Y., H.-X.Y. and B.-K.J.; Visualization, X.-R.W.; Supervision, B.-K.J.; Project administration, X.-R.W. and B.-K.J.; Funding acquisition, X.-R.W. and L.-P.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province, China (No. 2025JC-YBMS-588), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52468029).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chen, J.F.; Zeng, Q.H. International Comparison of Housing Security Policies from the Perspective of Welfare System Theory and Its Implications. Int. Econ. Rev. 2025, 11–27. Available online: http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.3799.F.20250611.2224.002.html (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Wang, X.R. A Comparative Analysis on the Unit Plans of Public Rental Housing in South Korea, China and Japan. Ph.D. Thesis, Daejin University, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Huang, T.; Jun, B.-K. A Comparative Study on Unit Plans of Public Rental Housing in China, Japan, and South Korea: Policy, Culture, and Spatial Insights for China’s Indemnificatory Housing Development. Buildings 2025, 15, 3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.M.; Wang, S.Y.; He, G. The Development Characteristics of Social Housing and the Trend of Thoughts in Foreign Countries. Archit. J. 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.Q. Research on Urban Public Housing Policies in China; China Social Sciences Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, L.; Zhang, C. The Evolution of Public Housing Policy in France and Its Implications. Urban Stud. 2018, 39, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, S.K. Housing Policy and Practice in Korea; Parkyoungsa: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, K.S. 30 Years of History of Korea National Housing Corporation; Korea National Housing Corporation: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Leem, S.H. Housing Policy for Half a Century; Kimoondang: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Jeon, S. Latent Class Analysis of Discrimination and Social Capital in Korean Public Rental Housing Communities. Buildings 2025, 15, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, J.Y.; Son, K.; Kim, Y. Public housing lifecycle cost analysis for optimal insulation standards in South Korea. Energy Build. 2018, 161, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S. Building Community Facilities and Forming Social Capital in Public Rental Housing Complexes in Seoul, Korea. Hous. Policy Debate 2025, 35, 286–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.W.; Choi, Y.O.; Yeo, J.K. An analysis of the public rental housing unit plan for Korean Social Housing: Focusing on the unit type, orientation and heating method. Reg. Assoc. Archit. Inst. Korean 2016, 18, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, L.; Xia, J. Comparison of International Rental Housing Provision and Development Models and Policy Implications for China. Architecture 2022, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.R.; Jun, B.K.; Kin, K.Y. A Study on the Unit Plan Characteristics of Security Housing in China. Korean Hous. Assoc. 2021, 32, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.J. Policy Evolution and Proposal of Public Housing in China. Ph.D. Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H.M. Reflection and Reconstruction of China’s Affordable Housing System. J. Yanbian Univ. Soc. Sci. 2017, 50, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, R. The Evolution, Characteristics and Orientation of China’s Affordable Housing System. J. Shenzhen Univ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2017, 34, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P. Research on Construction Strategy and Morphological Traits of Public Housing System in City. Ph.D. Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, D.M.; Wu, J.H. Objective Evaluation of Urban Living Environment Based on GIS Technology: A Case Study of Guangzhou Liwan District. Xi’an Univ. Arch. Tech. 2021, 53, 229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, M.; Kim, T.W.; Kim, J.Y.; Zheng, H. Housing satisfaction and improvement demand considering housing lifestyles of young residents in public rental housing. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 22, 3271–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Oh, M.W. Sustainable Design Alternatives and Energy Efficiency for Public Rental Housing in Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.Y.; Zuo, J. The Urban Housing Issues during the Rapid Urbanization Period in South Korea and Their Implications. Macroeconomics 2020, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.X. The Development and Implications of Public Rental Housing System in South Korea under the Context of Urbanization. China Price 2015, 10, 79–81. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Ryu, B.; Kang, N.E. Publicly subsidized senior housing: The national profile of independent living models in South Korea. Hous. Soc. 2025, 52, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; Woo, A. Uneven geography of health opportunities among subsidized households: Illustrating healthcare accessibility and walkability for public rental housing in Seoul, Korea. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0306743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wook, D.S.; Jin, Y.A. Does spatial configuration matter in residents’ conflicts in public housing complexes? Evidence from mixed tenure housings in South Korea. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2022, 21, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Park, J.H. The Evolving Roles of the Public and Private Sectors in Korea’s Public Rental Housing Supply. Archit. Res. 2020, 22, 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, S.J.; Lee, J.H.; Yi, J.S.; Kim, M.Y. Korean public rental housing for residential stability of the younger population: Analysis of policy impacts using system dynamics. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2019, 18, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Roh, B. Characteristics of Changes in Residential Building Layouts in Public Rental Housing Complexes in New Towns of Korea. Land 2025, 14, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Kim, S. Analysis of Coupled and Coordinated Development of South Korea’s Life-Cycle and Public Housing Systems from 2017 to 2021. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.J. The Evolution of Public Housing Policies Abroad and Its Enlightenment: Taking the UK, USA, and Singapore as Examples. City House 2021, 28, 200–202. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, W.G.; Kang, S.H.; Cho, J.M. A Comparative Analysis on Housing Unit Plans of Korea, China and Japan. Archit. Inst. Korea 2000, 16, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, C.H.; Jin, S.Z.; Li, Z.X. A Relative Analysis on the Multifamily Housing Unit Plans of China and Korea: A Case of Shenyang of China and Capital Region of Korea. Huazhong Archit. 2011, 29, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H. Research on the Development of Apartment Unit Plans in South Korea. Master’s Thesis, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.R.; Jun, B.K. An Analysis on Changes in Spatial Composition of Apartment Unit Plans in South Korea. C. 2021 Inst. Inter. Des. J. 2021, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.S. A study of the Role of the Public Rental Housing Policy in Rental Housing Markets: Focusing on a comparative analysis of the cases in Korea and Japan. J. Resid. Environ. Inst. Korea 2012, 10, 75–94. [Google Scholar]

- Land and Housing Corporation in South Korea. Available online: https://www.lh.or.kr/index.do (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Seoul Housing Corporation in South Korea. Available online: https://www.i-sh.co.kr/main/index.do (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Ding, C.; Sun, Y. Effect of Russia’s Housing Security Policy from the Perspective of National Planning and Its Inspiration. Urban Plan. Int. 2022, 37, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.A.; Zhou, Z.X. German Cooperative Housing: Systems, Practices and Implications. Urban Plan. Int. 2025, 40, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.R.; Oh, J.S.; Shim, Y.M. Public Rental Housing Policy in China and Korea. J. Hous. Urban 2014, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Z. Case study and discussion on the design of HDB Projects in Singapore with the sharing architecture and sharing city concept. Urban Des. 2020, 2, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakouti, M.; Maleki, N.S. Spatial reconfiguration of Iranian traditional houses to explore effective strategies of flexibility using space syntax analysis. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2024, 40, 65–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zheng, Q.; Jiang, X.; He, C. Multi-Scale Spatial Structure Impacts on Carbon Emission in Cold Region: Case Study in Changchun, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Qi, Y.; Wang, C. An Analysis of the Spatial Characteristics of Jin Ancestral Temple Based on Space Syntax. Buildings 2025, 15, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.A.; Yamu, L.D.V.C. Space Syntax has Come of Age: A Bibliometric Review from 1976 to 2023. J. Plan. Lit. 2024, 39, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.H.; Ma, X. The Evolution of Italian Public Housing Residential Area Planning and Its Enlightenment to China. Urban Archit. 2018, 34, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.N.; Zhang, Z.Y. Three Agendas of Bai-ziwan Public Rental Housing and Social Housing. Archit. J. 2022, 6, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.S.; Kim, H.J. The Spatial Analysis and Enhancement of Social Housing in Seoul. Buildings 2023, 13, 2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).