A Review of Indoor Thermal Comfort Studies on Older Adults in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background on Thermal Comfort Among Older Adults in China

1.2. Limitations of Existing Thermal Comfort Research

1.3. Objectives and Contributions of This Review

- (1)

- Identify and clarify how environmental and individual factors influence the thermal comfort of older adults.

- (2)

- Evaluate and compare the applicability of existing thermal comfort models to identify their strengths, limitations, and contexts of optimal use.

- (3)

- Propose specific directions for model optimization and future intelligent applications.

2. Method

2.1. Literature Identification

2.2. Keywords Frequency Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Environmental Factors Influencing Thermal Comfort in Older Adults

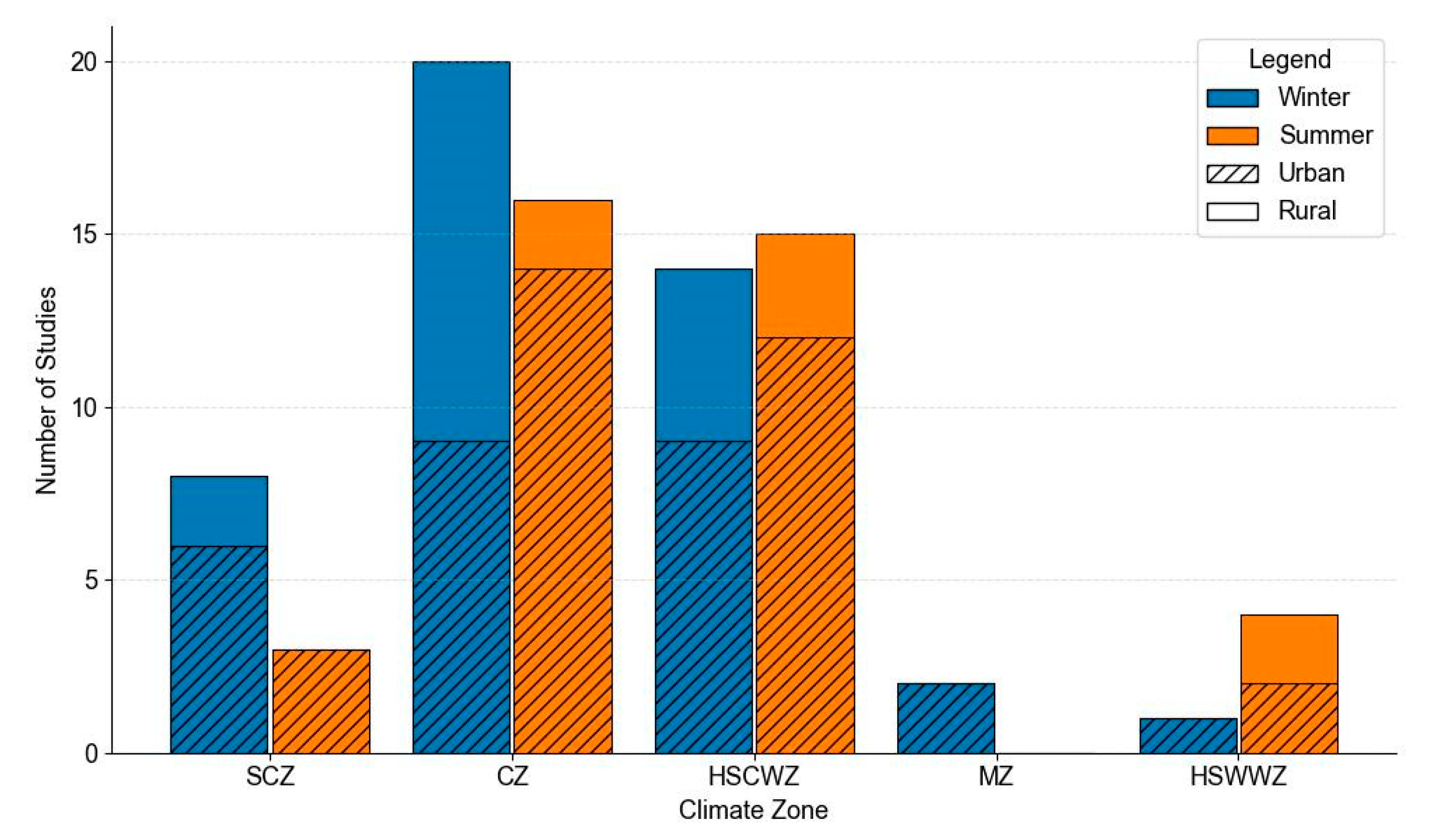

3.1.1. Climate Zones

3.1.2. Urban–Rural Differences

3.2. Individual Factors Influencing Thermal Comfort in Older Adults

3.2.1. Gender

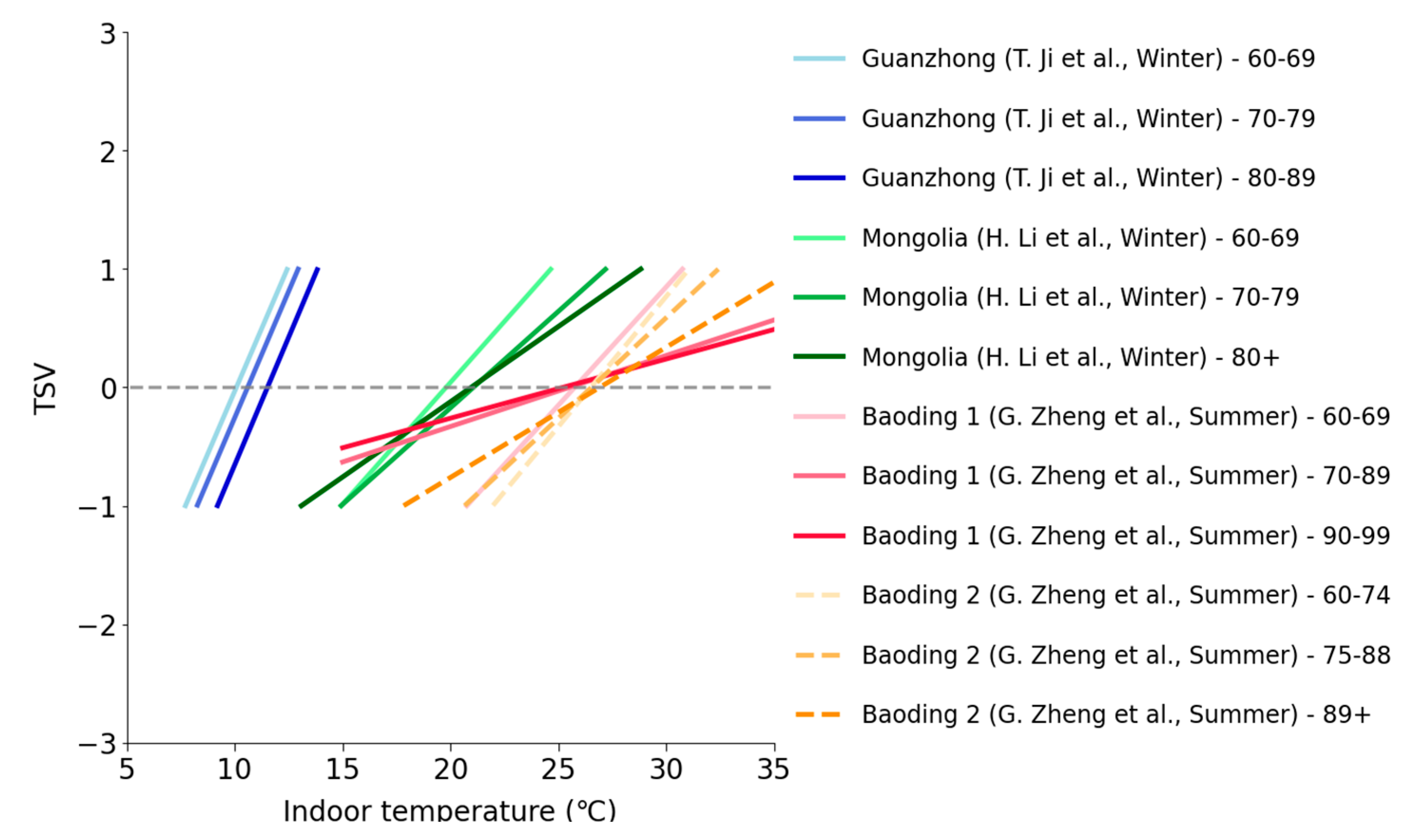

3.2.2. Age Groups

3.2.3. Frailty Levels

| Non-Frail Older Adults | Pre-Frail Older Adults | Frail Older Adults | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutral temperature | 25.8 °C in summer | 26.9 °C in summer | 27.9 °C in summer |

| Sensitivity of TSV to temperature (Slope) | 0.1139 in summer | 0.2001 in summer | 0.3399 in summer |

| Temperature difference triggering significant TSV differences | >5 °C | >3 °C | NA |

| Comfortable temperature range | 24.0–30.0 °C in summer; 18–22 °C in winter | 24.3–29.3 °C in summer; 19–23 °C in winter | 25.9–29.3 °C in summer; 20–24 °C in winter |

3.3. Evaluation Methods

3.3.1. Modified PMV Models

| Model/Method | City or Region (Climate Zone) | Sample Size (Subjects) | Key Parameters | Neutral Temperature or Comfortable Range (°C) | Paper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aPMV, Griffiths Method | Shanghai (HSCWZ) | 672 | α = 0.33 | Winter: 14 °C; Summer: 28 °C | [37] |

| aPMV | Xiangxi (HSCWZ) | 92 | Winter λ = −0.26 | Comfort temperature range 16.7–27.1 °C | [74] |

| aPMV | Suining, Sichuan (HSCWZ) | 177 | Summer λ = 0.065 | Acceptable temperature range 21.41–27.61 °C | [51] |

| aPMV, Griffiths Method | Weihai (CZ) | 203 | Cold λ = −0.38; Warm λ= 0.272; α = 0.33 | Griffiths 21.63 °C | [16] |

| aPMV | Hefei (HSCWZ) | 720 (60) | Summer λ = 0.21; Winter λ = −0.49 | NA | [45] |

| mPMV | Baoding (CZ) | 1535 (44) | Age coefficient BT (0.0012–0.0676) | 27.8–28.3 °C | [79] |

| PMVt | Shanghai (HSCWZ) | 447 (15) | Time-weighted coefficient | 25.5 °C | [78] |

3.3.2. ML Models

| Paper | Study Setting | Subjects (Sample Size) | Algorithm | Input Parameters | Output Parameter(s) | Generalization Test Method | Performance Metric(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [8] | Climate chamber | 38 (NA) | GBDT, AdaBoost, XGBoost | Environmental, physiological, and heat exchange parameters | 7-point TSV | 80% of the dataset for training and 20% for testing | R2, MAE, and MSE |

| [84] | Field study (summer) | 44 (3440) | AB, DT, GNB, KNN, RF, SVM, and XGBoost | Environmental, physiological, and human-related parameters | 3-point TSV | 80% of the dataset for training and 20% for testing | Precision, recall, accuracy (76%), ROC curve, AUC, and F1 score |

| [85] | Field study (summer) | 14 (1389) | LR, DT, KNN, and SVM | Environmental and physiological parameters | 3-point TSV | 80% of the dataset for training and 20% for testing | Precision, accuracy (70%), ROC curve, AUC, and F1 score |

| [86] | Field study (summer) | 20 (1865) | AB, RF, LR, ANN, and NB | Environmental parameters | 3, 5, 7, and 9-point TSV | 80% of the dataset for training and 20% for testing | Recall, accuracy (92.4%), ROC curve, AUC, and F1 score |

| [87] | Climate chamber | 13 (964) | BP and RBF | Environmental and physiological parameters | 3-point TSV | 80% of the dataset for training and 20% for testing | Accuracy (87.82%) |

| [88] | Climate chamber | 5 (NA) | SVM, RF, KNN, MLP-ANN | Physiological parameters | 3-point TSV | 10-fold cross-validation | Accuracy (81.2%), F1 score, ROC curve, and AUC |

| [81] | Field study (year-round) | 1040 (724) | RF | Environmental and human-related parameters | 3-point TSV | 80% of the dataset for training and 20% for testing | Accuracy (56.6%) Accuracy (81.2%) |

| Climate chamber | 18 (372) | RF | Physiological parameters | ||||

| [83] | Field study (winter) | 35 (135) | ANN, LoR, SVM, KNN, DT, and NB | Environmental and physiological parameters | 7-point TSV | 80% of the dataset for training and 20% for | Accuracy (67.6%) |

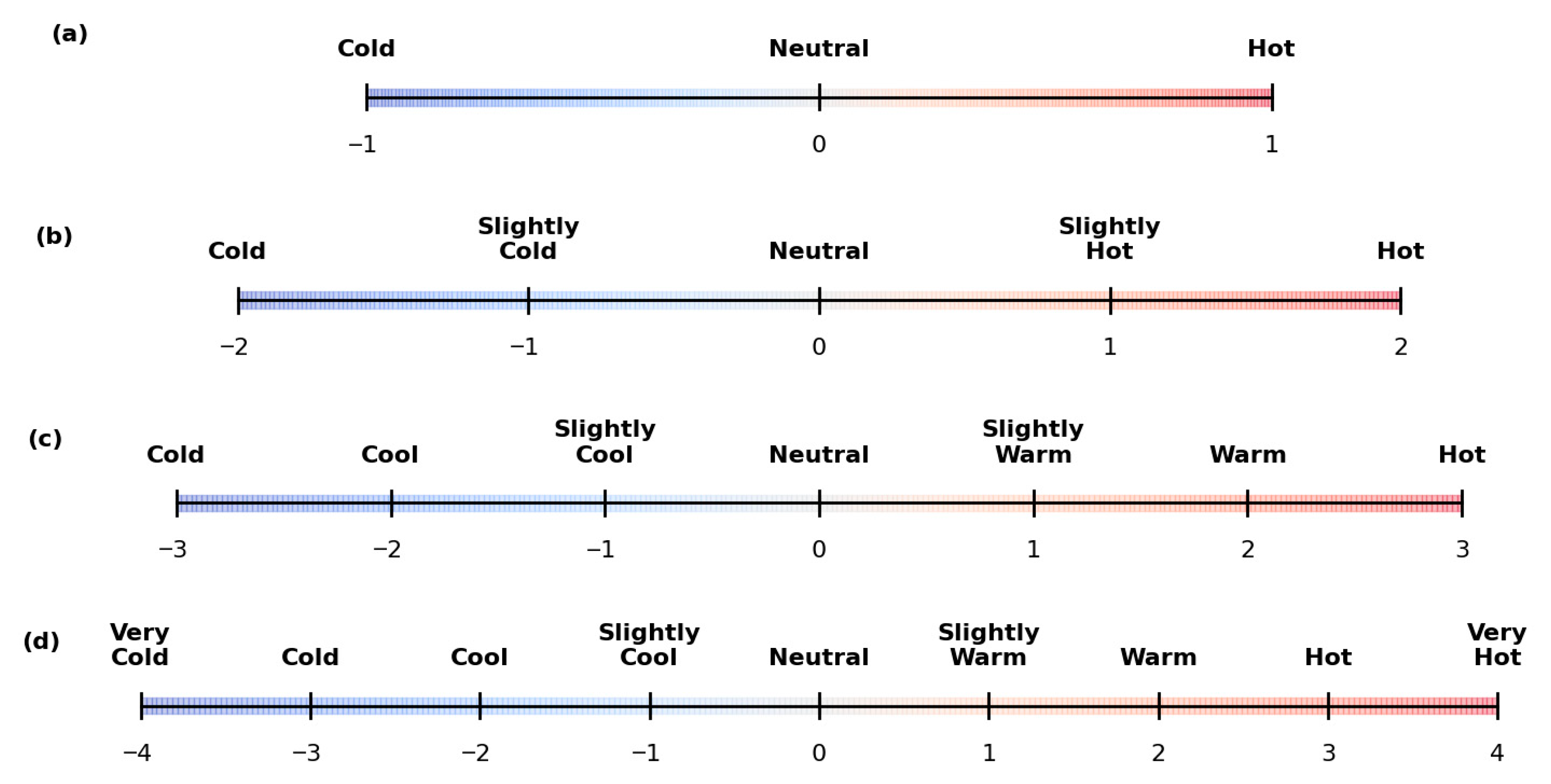

3.3.3. Thermal Comfort Questionnaires

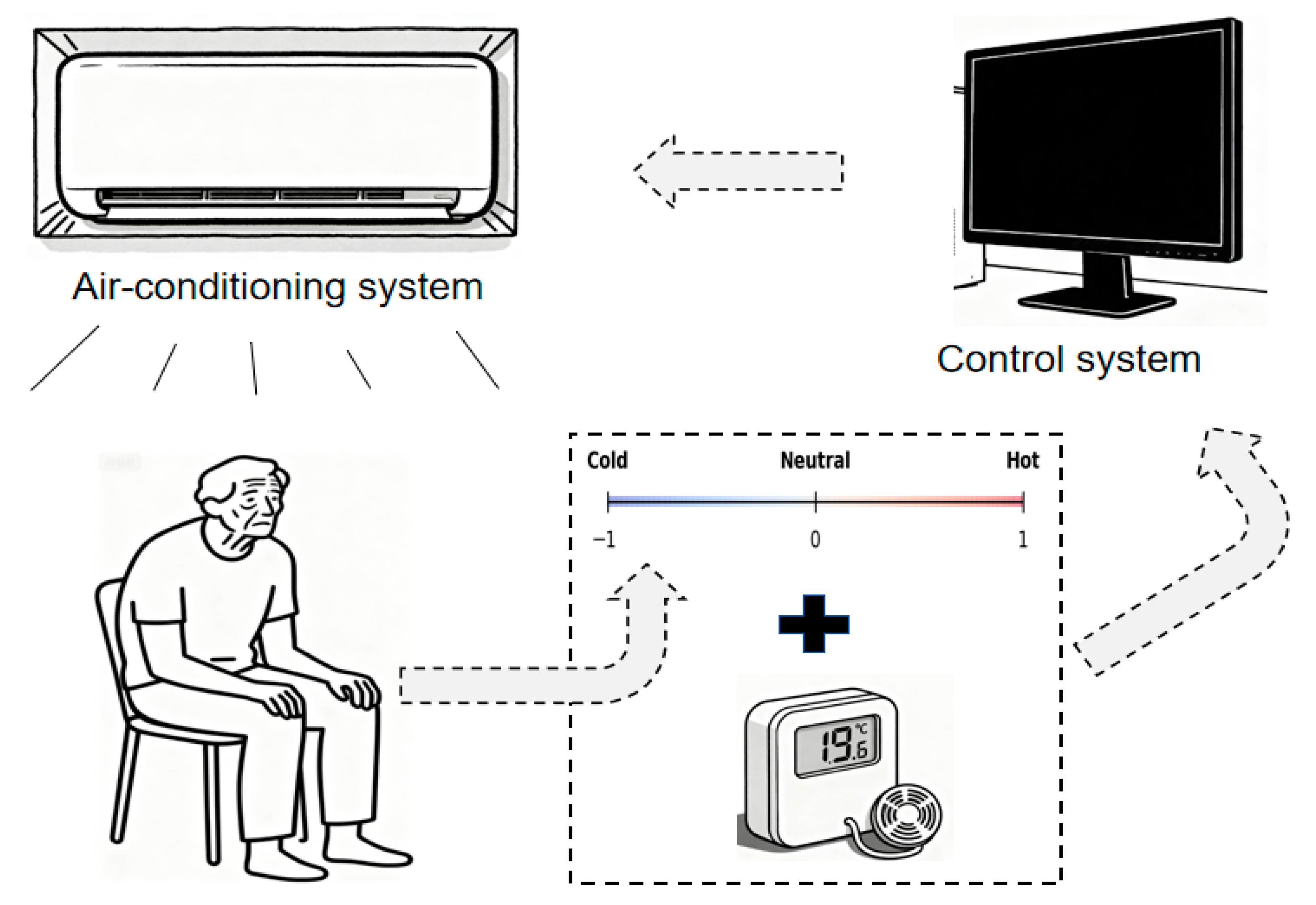

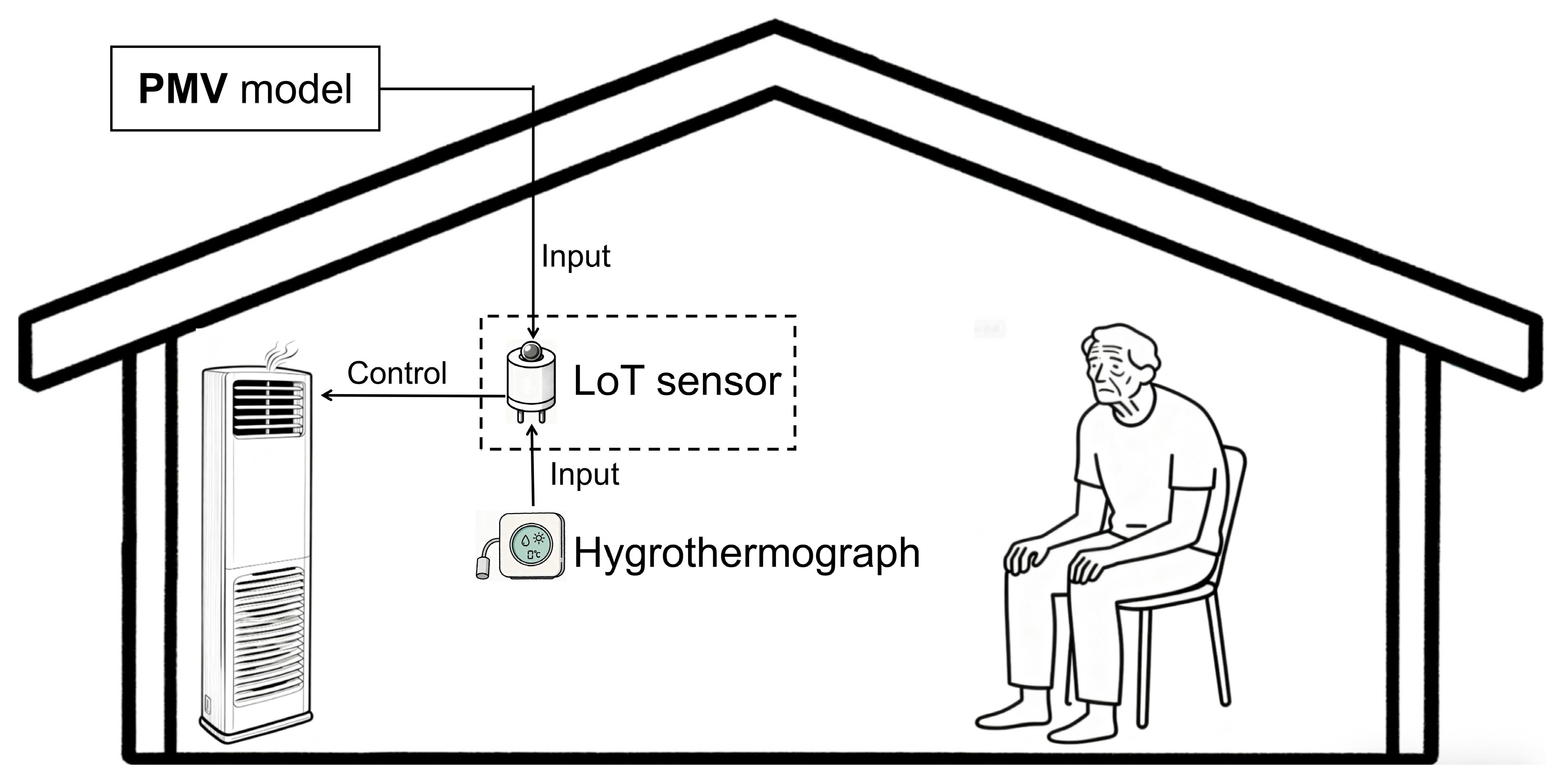

3.4. Application of Intelligent Technologies in Thermal Environment Regulation

4. Discussion

4.1. Influencing Factors and Model Comparison for Older Adults

| Factors | Influence on Neutral Temperature (Range) | Trend |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental factors | ||

| Climate zones and seasons | 2–8.8 °C | The winter–summer difference is largest in HSCWZ and smallest in HSWWZ. |

| Urban–rural differences | 0.13–7.98 °C | Larger differences occur in regions with greater disparities in indoor environmental conditions. |

| Individual factors | ||

| Gender | No significant difference | Older women tend to be less tolerant of heat. |

| Age groups | 0.41–1.45 °C | Neutral temperature generally increases with age. |

| Frailty | 2.1 °C | Higher frailty levels are associated with higher neutral temperatures. |

| Comparison Dimension | aPMV Model | ML Model |

|---|---|---|

| Input parameters | Fixed parameters include air temperature, mean radiant temperature, air velocity, clothing insulation, and relative humidity. | Flexible integration of environmental, individual, and physiological parameters. |

| Sample size | Hard to capture individual differences and relies on large samples. | Effective in capturing individual differences. Accuracy is mostly above 70%. |

| Output form | Outputs the 7-point TSV scale (−3 to +3), suitable for analyzing thermal sensation and comfort ranges. | Outputs are flexible, with the 3-point TSV scale (−1 to +1) being more suitable. |

| Application | Suitable for design standards and indoor thermal-comfort evaluation; Suitable for group-based models. | Suitable for intelligent control systems; Suitable for personalized models. |

4.2. Optimizing ML Models and Intelligent Temperature-Control Systems

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Environmental and individual factors jointly shape the thermal comfort of older adults, but their impacts on neutral temperature vary considerably. Environmental factors usually exert stronger and more variable effects (as shown in Table 4). Current research remains unevenly distributed across urban and rural areas, climate zones, and seasons. Future research should focus more on summer in the SCZ and winter in the HSWZ, and expand investigations in rural regions.

- (2)

- Comparative findings indicate that the aPMV model has limited flexibility in capturing individual differences and relies on small-scale datasets, making it more appropriate as a group-level model. In contrast, ML models exhibit clear advantages in identifying individual variability and perform well with longitudinal datasets, making them more appropriate for personalized modeling. Moreover, integrating physiological parameters can further improve their accuracy, and the adoption of the 3-point TSV scale questionnaire facilitates better integration with intelligent temperature-control systems. A more detailed comparison of the two models is presented in Table 5.

- (3)

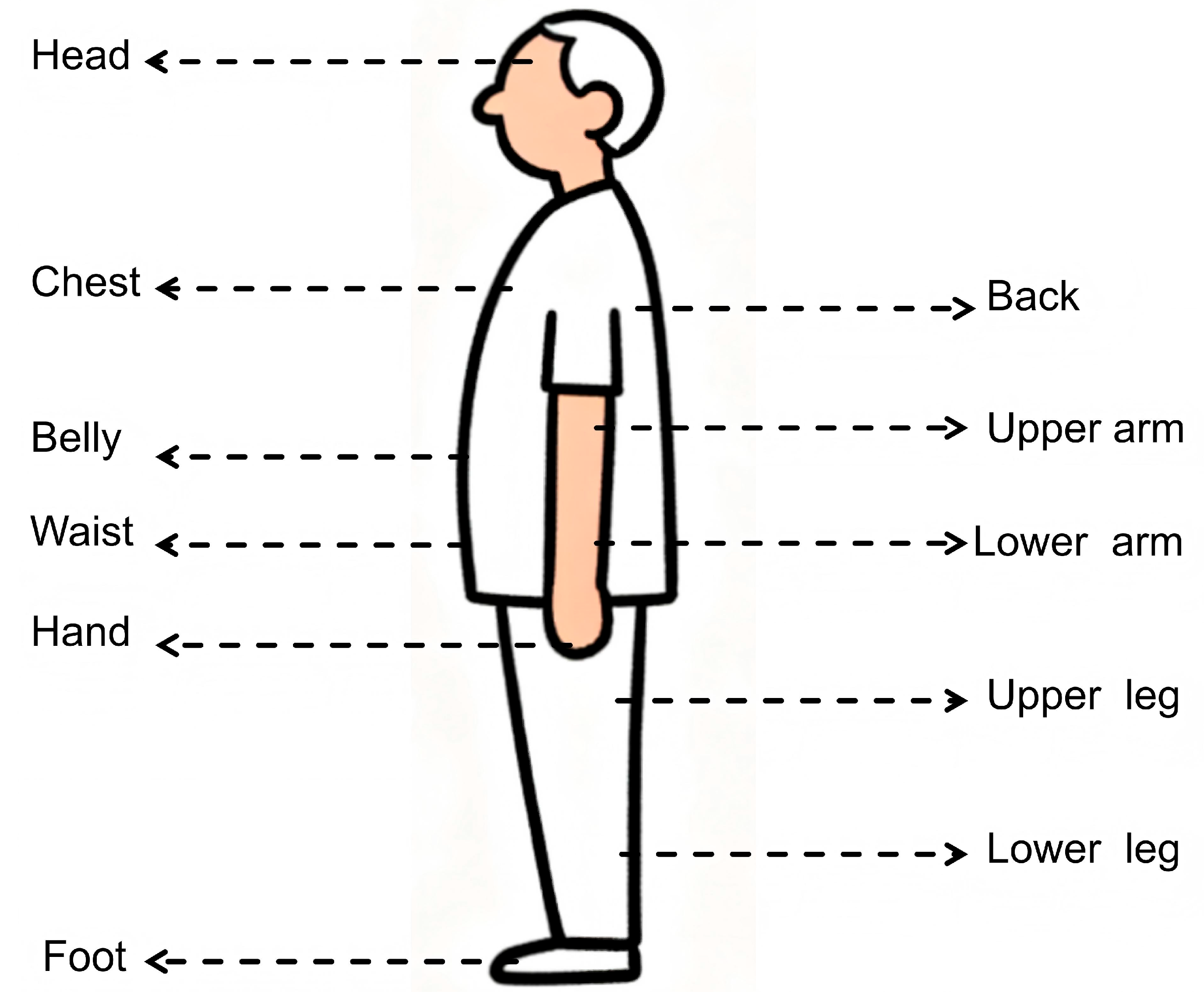

- Forehead and back skin temperatures can serve as indicative physiological parameters for predicting thermal sensation and providing health-related early warnings in warm environments, whereas lower-limb skin temperature is more indicative of cold discomfort. However, the real-world application of these physiological indicators remains limited. Future research should further incorporate these parameters into ML models to improve predictive performance and enhance intelligent temperature-control systems.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| aPMV | adaptive Predicted Mean Vote |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| PMV | Predicted Mean Vote |

| PPD | Predicted Percentage of Dissatisfied |

| TSV | Thermal Sensation Vote |

| SCZ | Severe Cold Zone |

| CZ | Cold Zone |

| HSCWZ | Hot Summer and Cold Winter Zone |

| HSWWZ | Hot Summer and Warm Winter Zone |

| MZ | Mild Zone |

| MST | Mean Skin Temperature |

| GBDT | Gradient Boosting Decision Tree |

| AdaBoost | Adaptive Boosting |

| XGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

| AB | Adaptive Boosting |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| GNB | Gaussian Naive Bayes |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbors |

| RF | Random Forest |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| NB | Naive Bayes |

| BP | Back Propagation Neural Network |

| RBF | Radial Basis Function Neural Network |

| MLP-ANN | Multi-Layer Perceptron Artificial Neural Network |

| LoR | Logistic Regression |

| CNKI | China National Knowledge Infrastructure |

| CSSCI | Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index |

References

- United Nations. World Population Prospects 2022; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China. Law on the Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly of China (2018 Amendment). Available online: https://www.gov.cn/guoqing/2021-10/29/content_5647622.htm (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Office of the Leading Group for the Seventh National Population Census of the State Council. Communiqué of the Seventh National Population Census (No. 5): Age Composition; National Bureau of Statistics of China: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, D. Negative population growth and population ageing in China. China Popul. Dev. Stud. 2023, 7, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, R.L.; Chen, C.P. Field study on behaviors and adaptation of elderly people and their thermal comfort requirements in residential environments. Indoor Air 2010, 20, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Bai, T.; Feng, L.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, W. Indoor Environmental Quality in Aged Housing and Its Impact on Residential Satisfaction Among Older Adults: A Case Study of Five Clusters in Sichuan, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, J.; Deng, W.; Beccarelli, P.; Lun, I.Y.F. Thermal comfort investigation of rural houses in China: A review. Build. Environ. 2023, 235, 110208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Liu, H.; Zhou, S.; Yao, Y.; Kosonen, R.; Wu, Y.; Li, B. Machine learning-based assessment of thermal comfort for the elderly in warm environments: Combining the XGBoost algorithm and human body exergy analysis. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2025, 209, 109519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Lian, Z.; Zhang, H. Investigation of the elderly’s response to winter temperature steps in severe cold area of China. Procedia Eng. 2017, 205, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Zhu, R.; Xie, J.C.; Yoshino, H. Indoor environment and the blood pressure of elderly in the cold region of China. Indoor Built Environ. 2022, 31, 2482–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.Y.; Tan, J.A.; Lee, M.C.J.; Cheng, T.J. A Study on the Relationship Between Indoor Thermal Comfort and the Physical and Psychological Perception of the Elderly. In Proceedings of the Kansei Engineering and Emotion Research, KEER 2024, Taichung, Taiwan, 20–23 November 2024; pp. 277–293. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Li, B.; Du, C.; Liu, H.; Wu, Y.; Hodder, S.; Chen, M.; Kosonen, R.; Ming, R.; Ouyang, L.; et al. Opportunities and challenges of using thermal comfort models for building design and operation for the elderly: A literature review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 183, 113504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Lan, L.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Y.; Fan, X.; Wyon, D.P.; Wargocki, P. Association of bedroom environment with the sleep quality of elderly subjects in summer: A field measurement in Shanghai, China. Build. Environ. 2022, 208, 108572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Chen, W.; Chen, S.; Liu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Cui, X.; Cao, B. Associations between indoor thermal environment assessment, mental health, and insomnia in winter. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 114, 105751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Wang, F.; Payne, S.R.; Weller, R.B. A comparison of the effect of indoor thermal and humidity condition on young and older adults’ comfort and skin condition in winter. Indoor Built Environ. 2022, 31, 759–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, J.; Deng, W.; Beccarelli, P.; Lun, I.Y.F. Investigation of thermal comfort and preferred temperatures among rural elderly in Weihai, China: Considering metabolic rate effects. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jingyi, M.; Shanshan, Z.; Wu, Y. The Influence of Physical Environmental Factors on Older Adults in Residential Care Facilities in Northeast China. Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2022, 15, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, C.; Guan, Y.; Cheng, T. Surrogate-based approach of predicting and optimising building performance by integrating daylighting, thermal comfort, and costs—A case study of community care homes. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 99, 111534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Yin, L.Y.; Dong, Q.W. Characteristics of indoor thermal environment requirements for elderly people in Tianjin during summer. Build. Sci. 2025, 41, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50736-2012; Code for Design of Heating Ventilation and Air Conditioning in Civil Buildings. China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Wang, R.; Zhao, C.; Li, W.; Qi, Y. Research on thermal comfort equation of comfort temperature range based on Chinese thermal sensation characteristics. In Advances in Manufacturing, Production Management and Process Control, Proceedings of AHFE 2019 International Conference on Human Aspects of Advanced Manufacturing, and the AHFE International Conference on Advanced Production Management and Process Control, Washington, DC, USA, 24–28 July 2019; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 254–265. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, X.Z.; Pang, W.; Liu, H.; Liang, M.M. Thermal environment and elderly thermal comfort in naturally ventilated residential buildings in Guilin during summer. J. Wuhan Univ. (Eng. Ed.) 2022, 55, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Gong, A.; Wang, C.; Han, Y.; Gao, W. Exploring thermal comfort for the older adults: A comparative study in Dalian City’s diverse living environments. Front. Archit. Res. 2025, 14, 812–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.Z.; Feng, X.; Li, C.; Gao, Y.F. Study on indoor thermal and humidity comfort for humans during hot weather. J. Shihezi Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 40, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Yu, H.; Tang, Y.; Weng, Q.; Zhang, K. Age differences in thermal comfort and sensitivity under contact local body cooling. Build. Environ. 2025, 268, 112355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Ding, X.; Bi, J.; Cui, Y. Field Study on Winter Thermal Comfort of Occupants of Nursing Homes in Shandong Province, China. Buildings 2024, 14, 2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Ma, T.; Lian, Z.; de Dear, R. Perceptual and physiological responses of elderly subjects to moderate temperatures. Build. Environ. 2019, 156, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Xiong, J.; Lian, Z. A human thermoregulation model for the Chinese elderly. J. Therm. Biol. 2017, 70, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, P.; Zhang, J.; He, R.; Zhang, G.H.; Chu, A. Development of smart heating clothing for the elderly. J. Text. Inst. 2022, 113, 2358–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, R.; Chen, L. Identifying sensitive population associated with summer extreme heat in Beijing. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 83, 103925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, L. Analysis of Chinese Elders’ Attitude and Preference Regarding Air Conditioning Usage in Bedrooms of Care Facilities in Summer—The Case of Shanghai. AIJ J. Technol. Des. 2022, 28, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Zhang, H. Comparison of thermal adaptation models between elderly and non-elderly people in naturally ventilated residential buildings. J. Dalian Univ. Technol. 2016, 56, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Deng, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Ren, Z.; Shan, X. Study on indoor thermal comfort of different age groups in winter in a rural area of China’s hot-summer and cold-winter region. Sc. Tech. Built Environ. 2022, 28, 1407–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Liu, C.; Duanmu, L.; Zhai, Y.; Lian, Z.; Cao, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; et al. Effects of individual factors on thermal sensation in the cold climate of China in winter. Energy Build. 2023, 301, 113720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Liu, Y.; Dong, J. Age-Related Thermal Comfort in a Science Museum with Hot–Humid Climate in Summer. In Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium on Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning (ISHVAC 2019), Harbin, China, 12–15 July 2019; pp. 421–431. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Wu, X.; Huang, X.; Shi, G. Adaptive Behaviors of Thermal Environment Based on Thermal Comfort for the Elderly People. In Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium on Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning (ISHVAC 2019), Harbin, China, 12–15 July 2019; pp. 221–227. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, Y.; Yu, H.; Wang, T.; An, Y.; Yu, Y. Thermal comfort and adaptation of the elderly in free-running environments in Shanghai, China. Build. Environ. 2017, 118, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Xie, J.; Yoshino, H.; Yanagi, U.; Hasegawa, K.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J. Investigation of indoor thermal environment in the homes with elderly people during heating season in Beijing, China. Build. Environ. 2017, 126, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.; Esseghir, M.; Merghem-Boulahia, L. Applying IoT and data analytics to thermal comfort: A review. In Machine Intelligence and Data Analytics for Sustainable Future Smart Cities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 171–198. [Google Scholar]

- Tufail, S.; Riggs, H.; Tariq, M.; Sarwat, A.I. Advancements and Challenges in Machine Learning: A Comprehensive Review of Models, Libraries, Applications, and Algorithms. Electronics 2023, 12, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auffhammer, M. Cooling China: The Weather Dependence of Air Conditioner Adoption. Front. Econ. China 2014, 9, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fei, Y.; Zhang, X.-B.; Qin, P. Household appliance ownership and income inequality: Evidence from micro data in China. China Econ. Rev. 2019, 56, 101309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Taubenboeck, H.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, F.; Wurm, M. Urbanization in China from the end of 1980s until 2010-spatial dynamics and patterns of growth using EO-data. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2019, 12, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50176-2016; Code for Thermal Design of Civil Buildings. China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Yu, J.; Hassan, M.D.T.; Bai, Y.; An, N.; Tam, V.W.Y. A pilot study monitoring the thermal comfort of the elderly living in nursing homes in Hefei, China, using wireless sensor networks, site measurements and a survey. Indoor Built Environ. 2020, 29, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Che, D.; Zhou, F.; Liu, Y.; Seigen, C. Filed Study on Human Thermal Comfort for the Elderly in Xi’an, China. In Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium on Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning (ISHVAC 2019), Harbin, China, 12–15 July 2019; Environmental Science and Engineering. pp. 925–933. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.Y.; Jiang, S.; Dai, J.; Xu, X. Investigation of summer thermal comfort in rooms of a nursing home in Shihezi, Xinjiang. J. Shihezi Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 37, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Shao, T.; Lin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Dong, C.; Liu, J. A field study on seasonal adaptive thermal comfort of the elderly in nursing homes in Xi’an, China. Build. Environ. 2022, 208, 108623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xia, L.; Lu, J. Development of Adaptive Prediction Mean Vote (APMV) Model for the Elderly in Guiyang, China. Energy Procedia 2017, 142, 1848–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Lai, S.; Meng, Q.; Santamouris, M.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, L. Comparison of indoor thermal comfort of the elderly in urban, suburban rural and mountainous rural areas in South China karst. Build. Environ. 2025, 282, 113260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, T.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Zhou, L.; Cao, Y.; Shen, Q. Environment improvement and energy saving in Chinese rural housing based on the field study of thermal adaptability. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2022, 71, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Jiao, Z.; Duan, Y.; Guan, Y.; Hu, Q.; Gao, W. Winter thermal study in coastal rural dwellings: Focus on elderly comfort in Chinese cold coastal regions. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 24, 3971–3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Y.; Liu, J.; Pei, Z.; Chen, J. Occupants’ tolerance of thermal discomfort before turning on air conditioning in summer and the effects of age and gender. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 50, 104099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Li, N.; Wei, Z.; Shen, X.; Cui, H. Residential Thermal Environment and Thermal Sensation Model of the Elderly in Hunan Province in Winter. In Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium on Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning (ISHVAC 2019), Harbin, China, 12–15 July 2019; pp. 373–383. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, G.; Xie, J.; Yoshino, H.; Yanagi, U.; Hasegawa, K.; Kagi, N.; Goto, T.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, C.; Liu, J. Indoor environmental conditions in urban and rural homes with older people during heating season: A case in cold region, China. Energy Build. 2018, 167, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Feng, R.; Wang, Y.; Shao, T.; Chow, D.; Zhang, L. Fundamental Research on Sustainable Building Design for the Rural Elderly: A Field Study of Various Subjective Responses to Thermal Environments and Comfort Demands during Summer in Xi’an, China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gu, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Gao, W.; Xiao, F. Study on the challenge and influence of the built thermal environment on elderly health in rural areas: Evidence from Shandong, China. Build. Simul. 2023, 16, 1345–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Zheng, W.; Wang, Y.; Shao, T.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Fang, Y.; Dong, C. Thermal responses of the elderly in naturally ventilated dwelling houses during winter in rural Xi’an, China. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 546, 01008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong XZ, C.C. Field study on indoor thermal environment and thermal comfort in rural houses during summer in Hezhou. J. Wuhan Univ. (Eng. Ed.) 2022, 55, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Kang, J. Indoor Environmental Quality of Residential Elderly Care Facilities in Northeast China. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 860976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Cong, Y.; Yao, S.; Dai, C.; Li, Y. Research on the thermal comfort of the elderly in rural areas of cold climate, China. Adv. Build. Energy Res. 2022, 16, 612–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- XL, Y. Investigation and analysis of indoor thermal environment for elderly people in nursing homes in Shanghai. Heat. Vent. Air Cond. 2011, 41, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, Y.; Yu, H.; Wang, Z.; Wei, Q.; Yu, Y. Influence of individual factors on thermal satisfaction of the elderly in free running environments. Build. Environ. 2017, 116, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhang, T.; Fukuda, H.; He, J.; Bao, X. Comprehensive Study of Residential Environment Preferences and Characteristics among Older Adults: Empirical Evidence from China. Buildings 2024, 14, 2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, T.; Zhang, T.; Fukuda, H. Thermal Comfort Research on the Rural Elderly in the Guanzhong Region: A Comparative Analysis Based on Age Stratification of Residential Environments. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, G.; Chen, J.; Duan, J. Investigating the Adaptive Thermal Comfort of the Elderly in Rural Mutual Aid Homes in Central Inner Mongolia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Wei, C.; Yue, X.; Li, K. Application of hierarchical cluster analysis in age segmentation for thermal comfort differentiation of elderly people in summer. Build. Environ. 2023, 230, 109981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Wei, C.; Li, K. Determining the summer indoor design parameters for pensioners’ buildings based on the thermal requirements of elderly people at different ages. Energy 2022, 258, 124854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M146–M156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Yu, W.; Zhao, K.; Shan, H.; Zhou, S.; Wei, S.; Ouyang, L. Thermal demand characteristics of elderly people with varying levels of frailty in residential buildings during the summer. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Kort, H.S.; Loomans, M.G.L.C.; Tran, T.H.; Wei, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shi, W.; Zhou, S.; Yu, W. Lab study on the physiological thermoregulatory abilities of older people with different frailty levels. Build. Environ. 2024, 266, 112130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yu, W.; Kort, H.S.M.; Loomans, M.G.L.C.; Wei, S.; Zhou, S.; Guo, M.; Zheng, H.; Chen, M.; Tran, T.H.; et al. Air speed needs and local sensitivity of non-frail and pre-frail older adults: A lab study in China. Build. Environ. 2025, 280, 113118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yu, W.; Wei, S.; Zhao, K.; Shan, H.; Zheng, S.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Y. Variability in thermal comfort and behavior of elderly individuals with different levels of frailty in residential buildings during winter. Build. Environ. 2025, 267, 112290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.P.; Fang, X.; Wei, Z.X.; Shen, X.H.; Wu, Z.B. Study on winter indoor thermal environment and elderly thermal comfort in residential buildings in Xiangxi. J. Hunan Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 46, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Du, X.Y. Evaluation of adaptive thermal comfort for elderly people in naturally ventilated residential buildings during summer. Heat. Vent. Air Cond. 2015, 45, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Cai, R.; Qu, K.Y.; Hui, J.H. Study on summer indoor thermal comfort in institutional elderly care facilities in Baoding. Build. Sci. 2022, 38, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50785-2012; Evaluation Standard for Indoor Thermal Environment in Civil Buildings. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Miao, Y.; Chau, K.W.; Lau, S.S.Y.; Ye, T. A novel thermal comfort model modified by time scale and habitual trajectory. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 207, 114903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Yi, W.; Jia, R.; Yue, X. Application of logistic function in a new PMV modification model for elderly people: Combining age and TSV. Build. Environ. 2025, 267, 112182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fard, Z.Q.; Zomorodian, Z.S.; Korsavi, S.S. Application of machine learning in thermal comfort studies: A review of methods, performance and challenges. Energy Build. 2022, 256, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yu, H.; Luo, M.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Jiao, Y. Predicting older people’s thermal sensation in building environment through a machine learning approach: Modelling, interpretation, and application. Build. Environ. 2019, 161, 106231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Xu, L.; Zhang, J.S.; Niu, B.; Luo, M.H.; Zhou, G.Y.; Zhang, X. Data-driven thermal comfort model via support vector machine algorithms: Insights from ASHRAE RP-884 database. Energy Build. 2020, 211, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Yin, D.; Li, K.; Zhan, J.; Wang, S. Thermal sensation prediction model for the elderly in rural areas of cold regions under winter conditions. Energy Build. 2025, 337, 115657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Zhang, Y.; Yue, X.; Li, K. Interpretable prediction of thermal sensation for elderly people based on data sampling, machine learning and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP). Build. Environ. 2023, 242, 110602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Yue, X.; Yi, W.; Jia, R. Establishment, interpretation and application of logistic regression models for predicting thermal sensation of elderly people. Energy Build. 2024, 315, 114318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Yi, W.; Li, X.; Ni, R. Machine learning-based prediction and transformation of thermal sensation votes (TSV) under different scales for elderly people in summer. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 99, 111519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Liu, M. Neural network-based thermal comfort prediction for the elderly. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 237, 02022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, J.; He, W. Evaluation and prediction of elderly thermal comfort at varying ambient temperatures based on electroencephalogram signals and machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 15th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, BioMedical Engineering and Informatics (CISP-BMEI 2022), Beijing, China, 5–7 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, G.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Yue, X.; Li, X. Determination of the optimal thermal sensation voting scale for elderly people in summer: Considering environment-physiology-TSV correlation characteristics. Build. Environ. 2025, 274, 112777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.H.; Xie, J.Q.; Yan, Y.C.; Ke, Z.H.; Yu, P.R.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.S. Comparing machine learning algorithms in predicting thermal sensation using ASHRAE Comfort Database II. Energy Build. 2020, 210, 109776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.Y.; An, N.; Hassan, T.; Kong, Q. A Pilot Study on a Smart Home for Elders Based on Continuous In-Home Unobtrusive Monitoring Technology. Herd-Health Env. Res. Des. J. 2019, 12, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.T.; Yu, J.; Zhu, W.; Liu, F.; Liu, J.; An, N. Monitoring thermal comfort with IoT technologies: A pilot study in Chinese eldercare centers. In Proceedings of the Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population. Applications in Health, Assistance, and Entertainment, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 15–20 July 2018; pp. 303–314. [Google Scholar]

- Loftus, T.J.; Ruppert, M.M.; Shickel, B.; Ozrazgat-Baslanti, T.; Balch, J.A.; Efron, P.A.; Upchurch Jr, G.R.; Rashidi, P.; Tignanelli, C.; Bian, J. Federated learning for preserving data privacy in collaborative healthcare research. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 20552076221134455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, T.; Yang, J.; Gu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y. Research on privacy protection in the context of healthcare data based on knowledge map. Medicine 2024, 103, e39370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, L.; Feng, T.; Tang, J.; Huang, J.H.; Cai, Z.L. Multi-Index Analysis of Spatiotemporal Variations of Dry Heat Waves and Humid Heat Waves in China. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Xia, D.; Zhang, L.; Zou, Y.; Guo, G.; Chen, Z.; Xie, W. Assessing the winter indoor environment with different comfort metrics in self-built houses of hot-humid areas: Does undercooling matter for the elderly? Build. Environ. 2024, 263, 111871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhong, X.; Zhang, K.; Mao, H.; Geng, J.; Wang, M. Understanding local thermal comfort and physiological responses in older people under uniform thermal environments. Physiol. Behav. 2025, 292, 114832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Q.; Wang, R.; Li, Y.; Miao, Y.; Zhao, J. Human thermal sensation and comfort in a non-uniform environment with personalized heating. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 578, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Li, B.; Chen, B.; Kosonen, R.; Jokisalo, J. Age differences in thermal comfort and physiological responses in thermal environments with temperature ramp. Build. Environ. 2023, 228, 109887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yu, H.; Wang, Z.; Luo, M.; Li, C. Validation of the stolwijk and tanabe human thermoregulation models for predicting local skin temperatures of older people under thermal transient conditions. Energies 2020, 13, 6524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yu, H.; Jiao, Y.; Chu, X.; Luo, M. Chinese older people’s subjective and physiological responses to moderate cold and warm temperature steps. Build. Environ. 2019, 149, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, B.; Kosonen, R. Experimental study on the thermal comfort and physiological responses of the elderly in unstable environments. E3S Web Conf. 2022, 356, 03011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Kang, M.; Lan, L.; Wang, Z.; Lin, Y. Experimental study of the negative effects of raised bedroom temperature and reduced ventilation on the sleep quality of elderly subjects. Indoor Air 2022, 32, e13159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Li, Y.; Jia, Z.W.; Gao, W.J. Effects of indoor thermal environment in rural houses on cardiovascular physiological parameters of elderly people. Build. Sci. 2023, 39, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Mohamed, M.F.; Mohammad Yusoff, W.F. A Review of Indoor Thermal Comfort Studies on Older Adults in China. Buildings 2025, 15, 4331. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234331

Li J, Mohamed MF, Mohammad Yusoff WF. A Review of Indoor Thermal Comfort Studies on Older Adults in China. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4331. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234331

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jia, Mohd Farid Mohamed, and Wardah Fatimah Mohammad Yusoff. 2025. "A Review of Indoor Thermal Comfort Studies on Older Adults in China" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4331. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234331

APA StyleLi, J., Mohamed, M. F., & Mohammad Yusoff, W. F. (2025). A Review of Indoor Thermal Comfort Studies on Older Adults in China. Buildings, 15(23), 4331. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234331