Seismic Performance of T-Shaped Aluminum Alloy Beam–Column Bolted Connections: Parametric Analysis and Design Implications Based on a Mixed Hardening Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

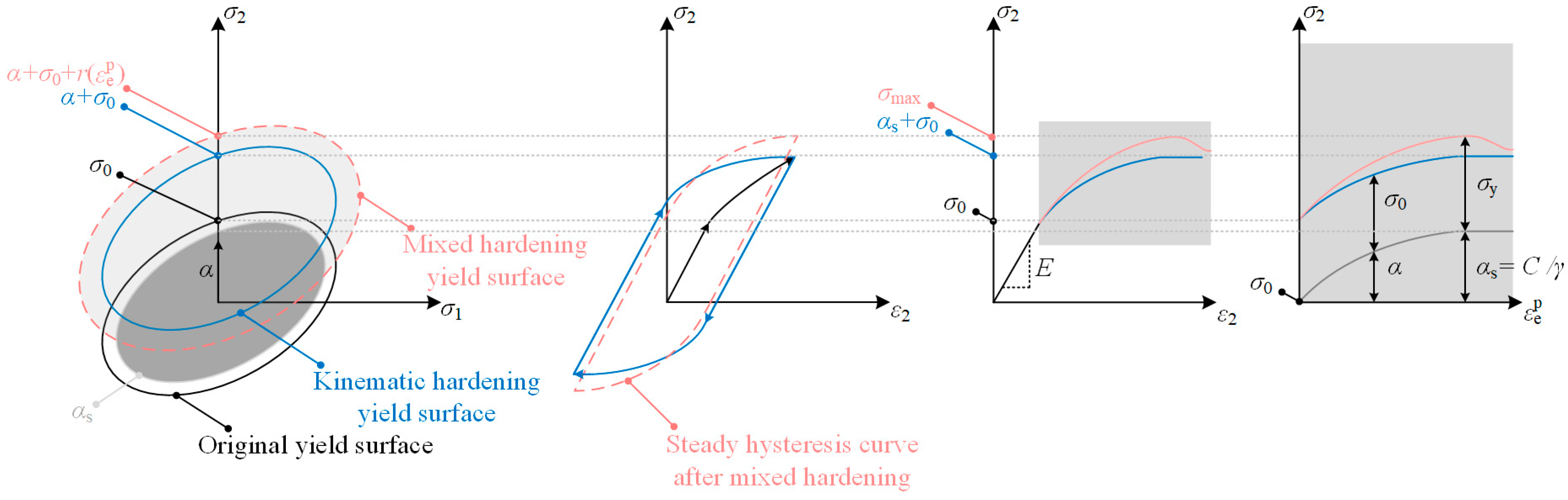

2.1. Selection of the Mixed Hardening Model

2.2. Framework of the Mixed Hardening Model

2.3. Hardening Rule of the Mixed Hardening Model

2.3.1. Isotropic Hardening Rule

2.3.2. Kinematic Hardening Rule

3. Numerical Model Setups

3.1. Experimental and Simulation Overview

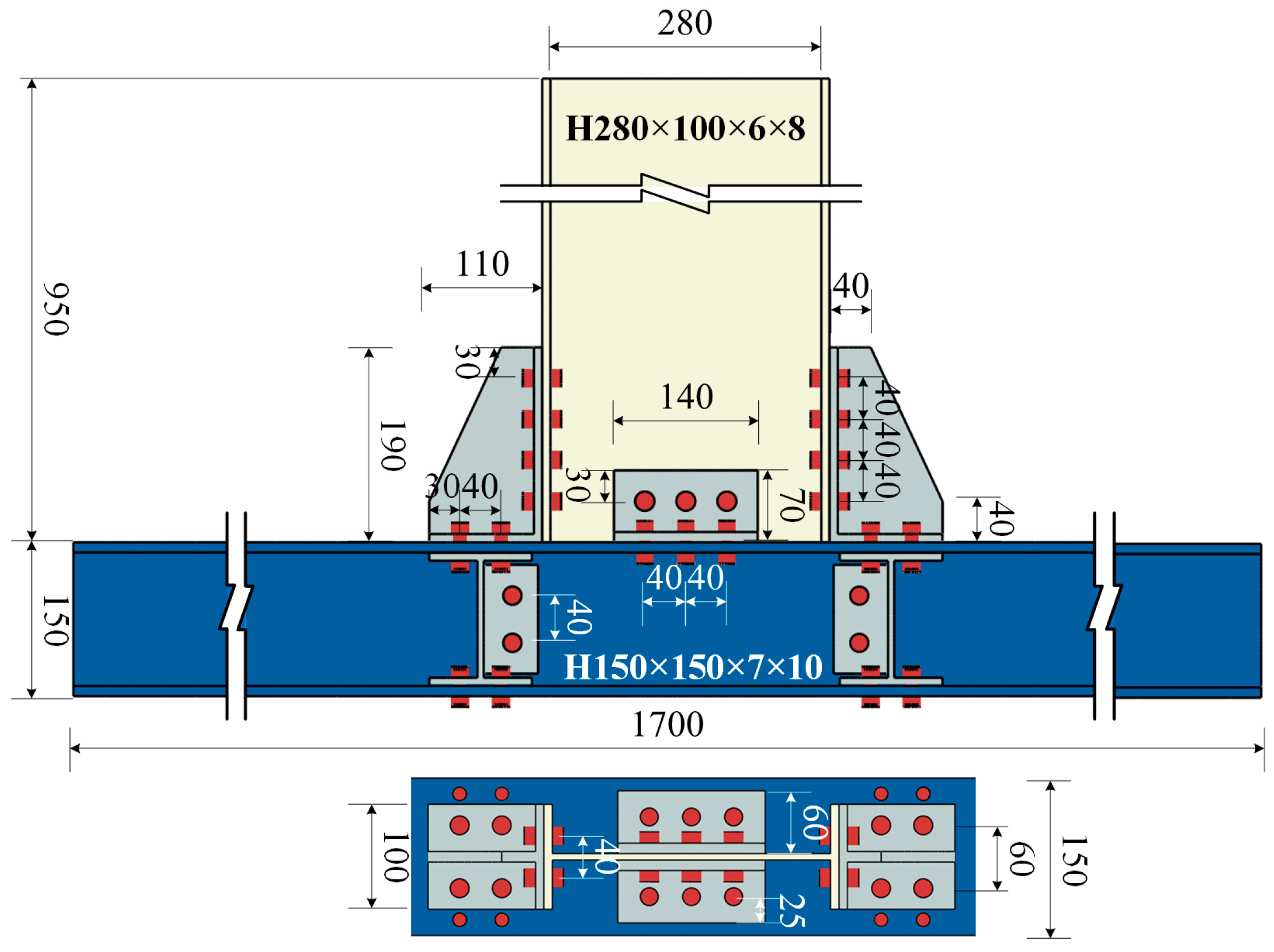

3.1.1. Test Specimen

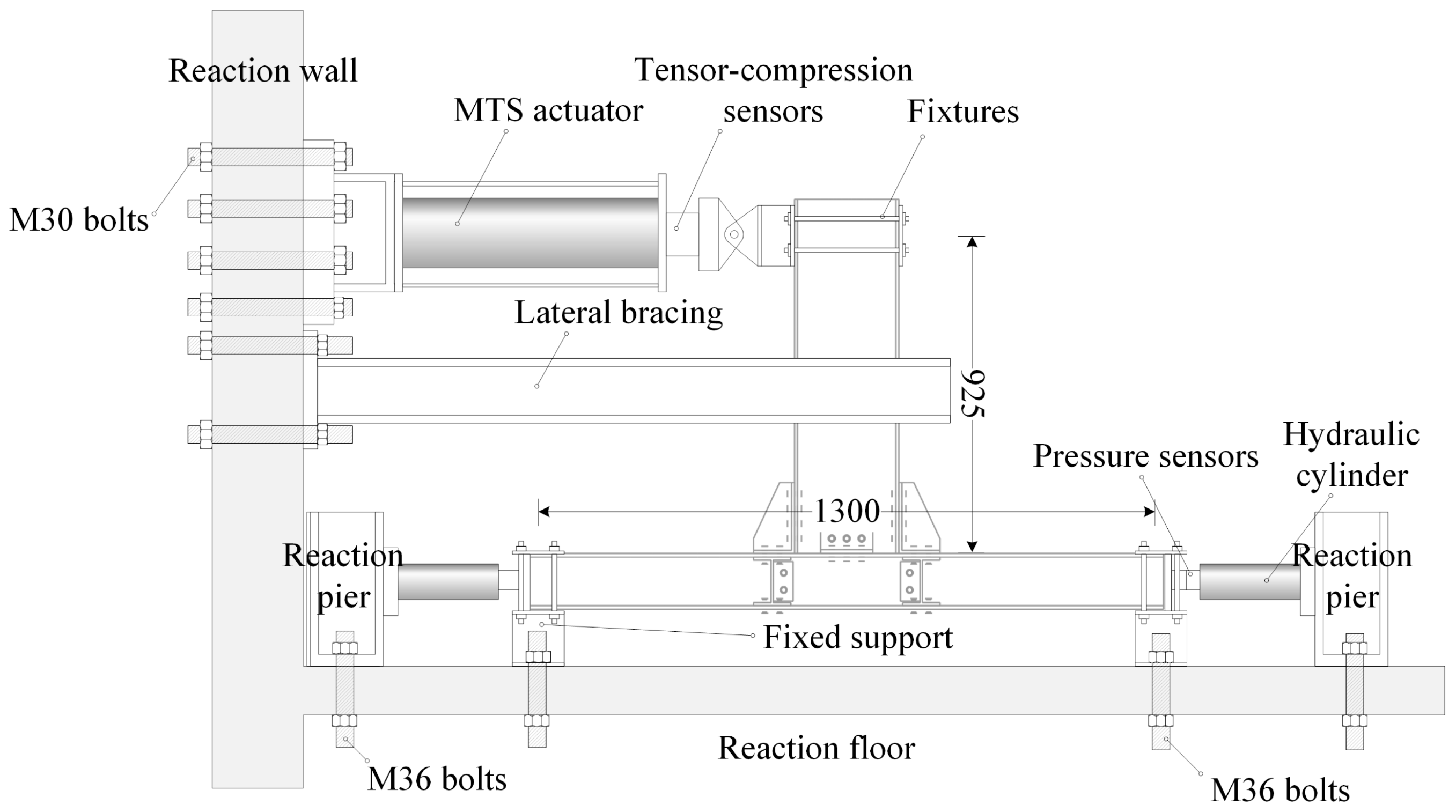

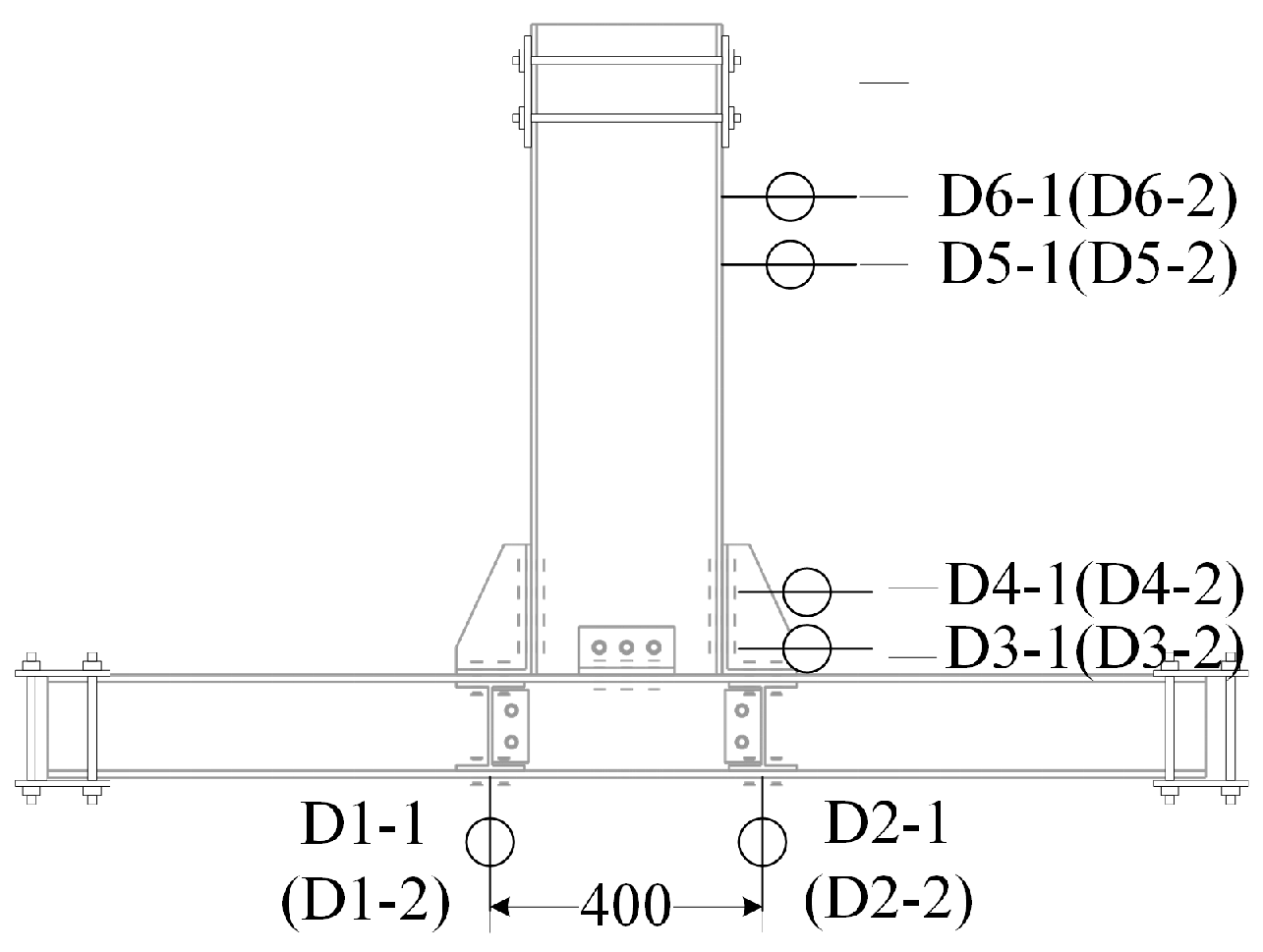

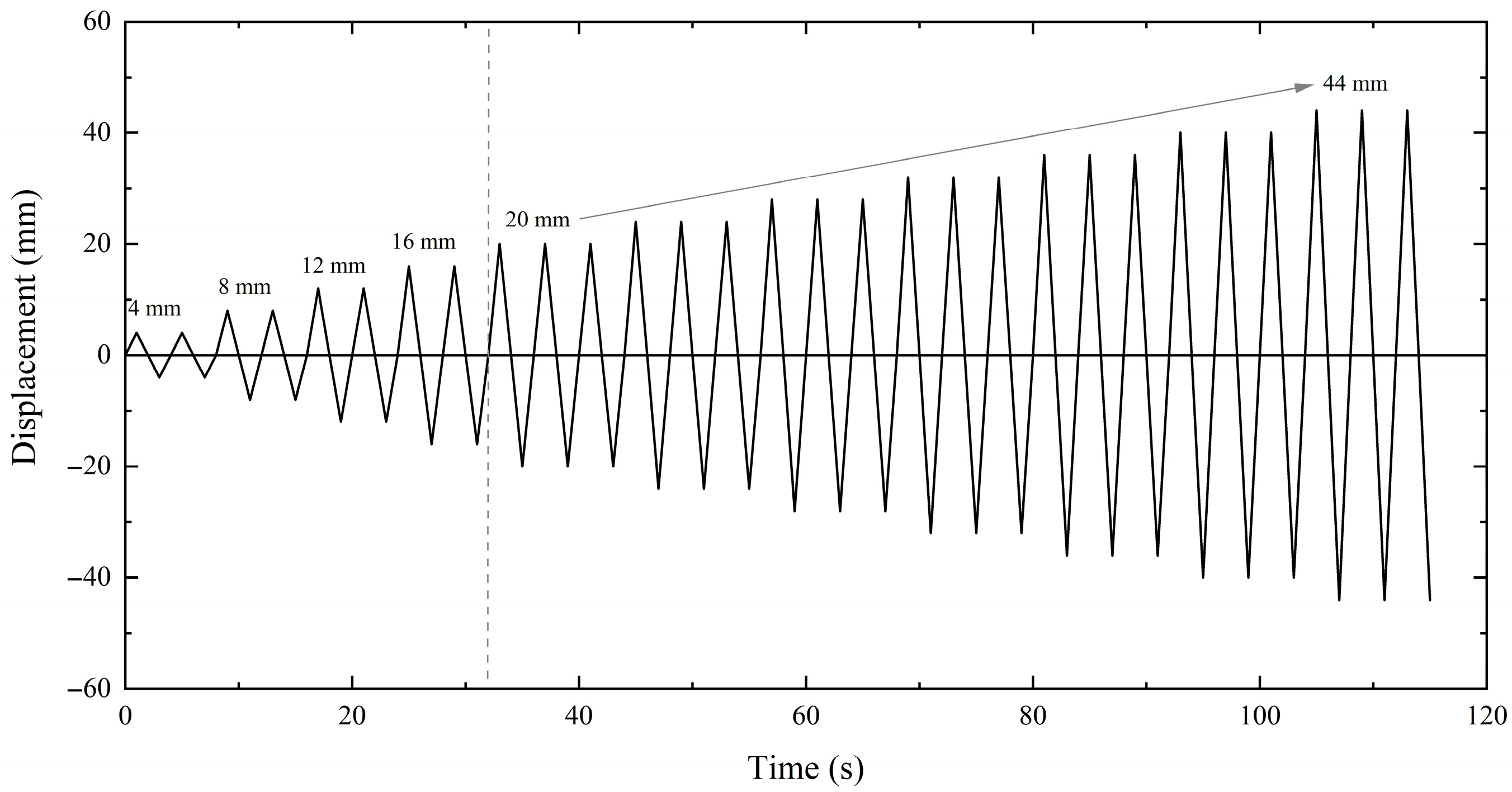

3.1.2. Experimental Design

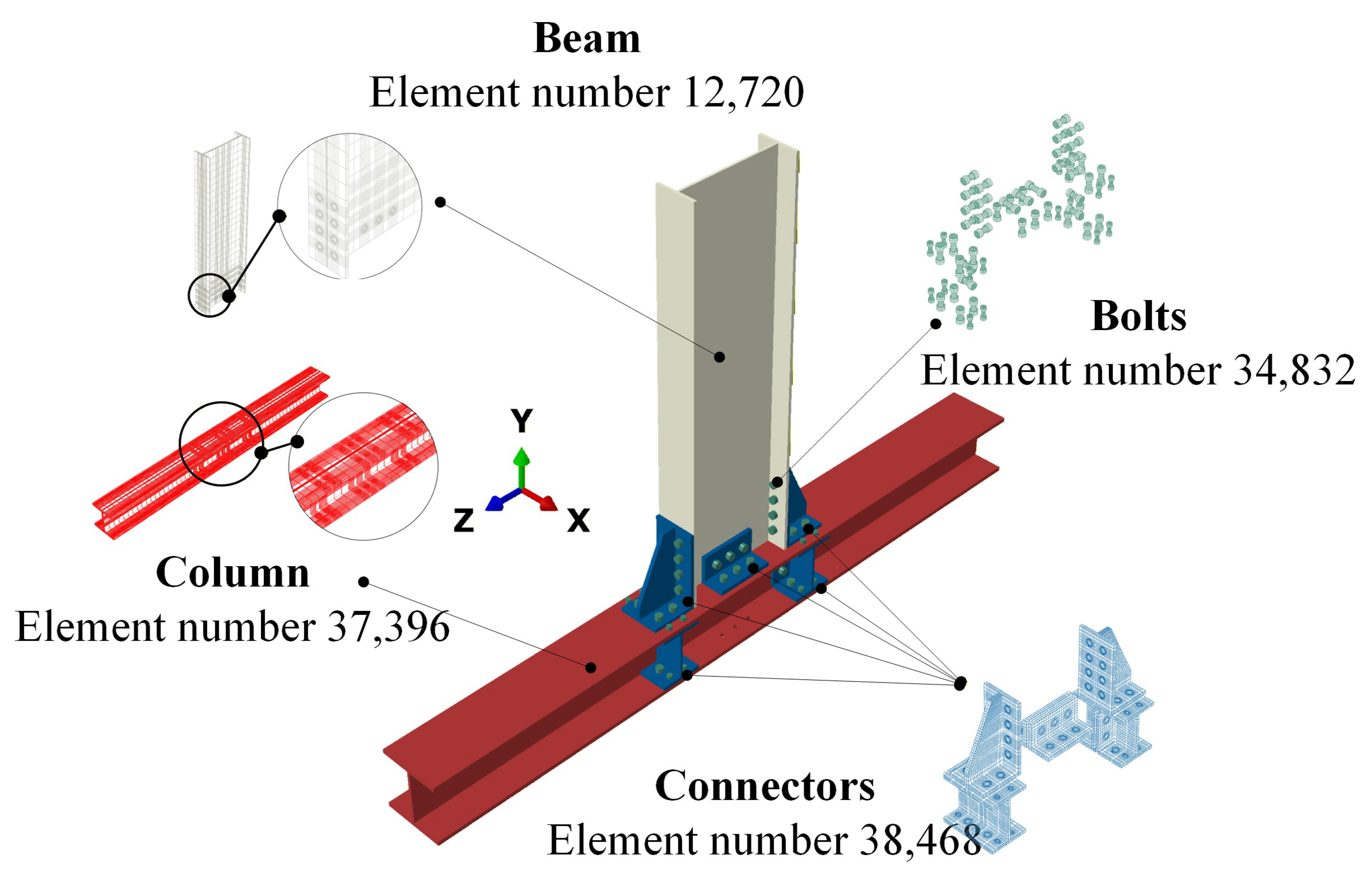

3.1.3. Finite Element Model

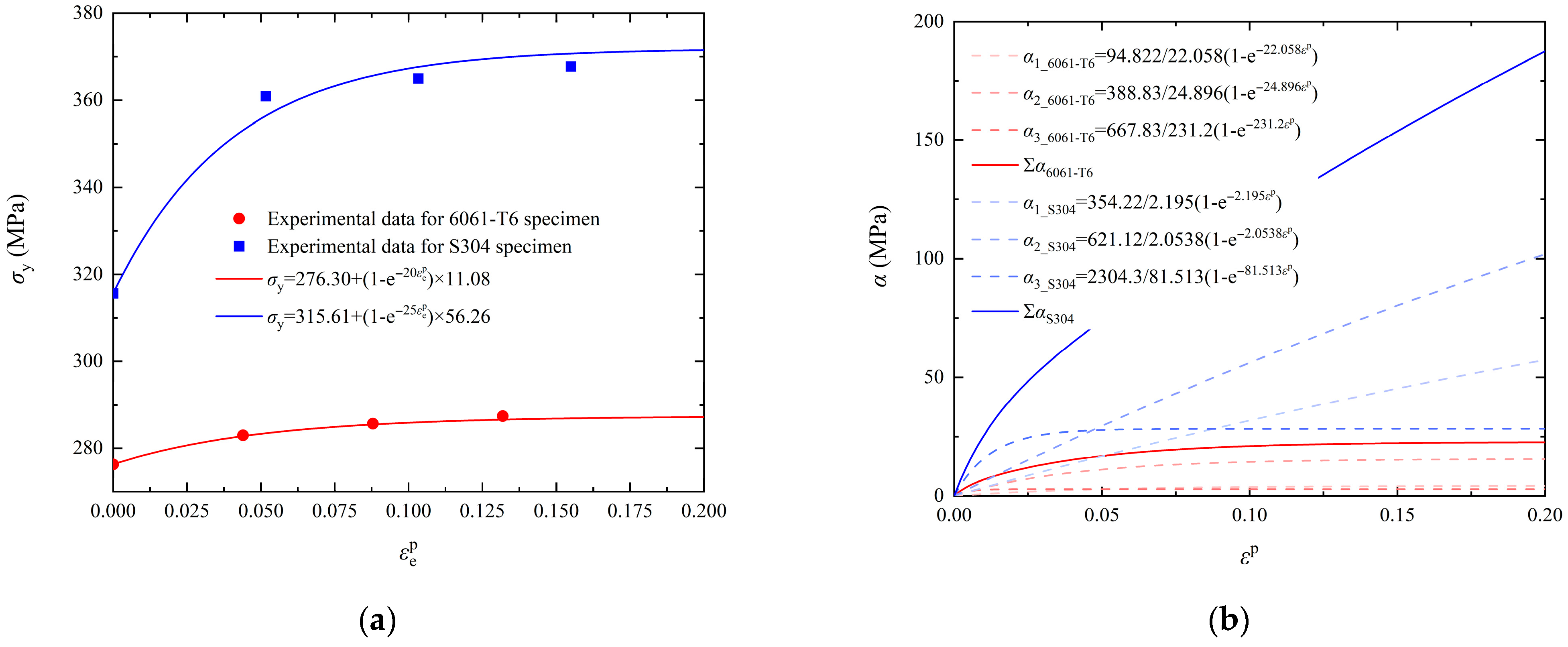

3.1.4. Mixed Hardening Model Parameters

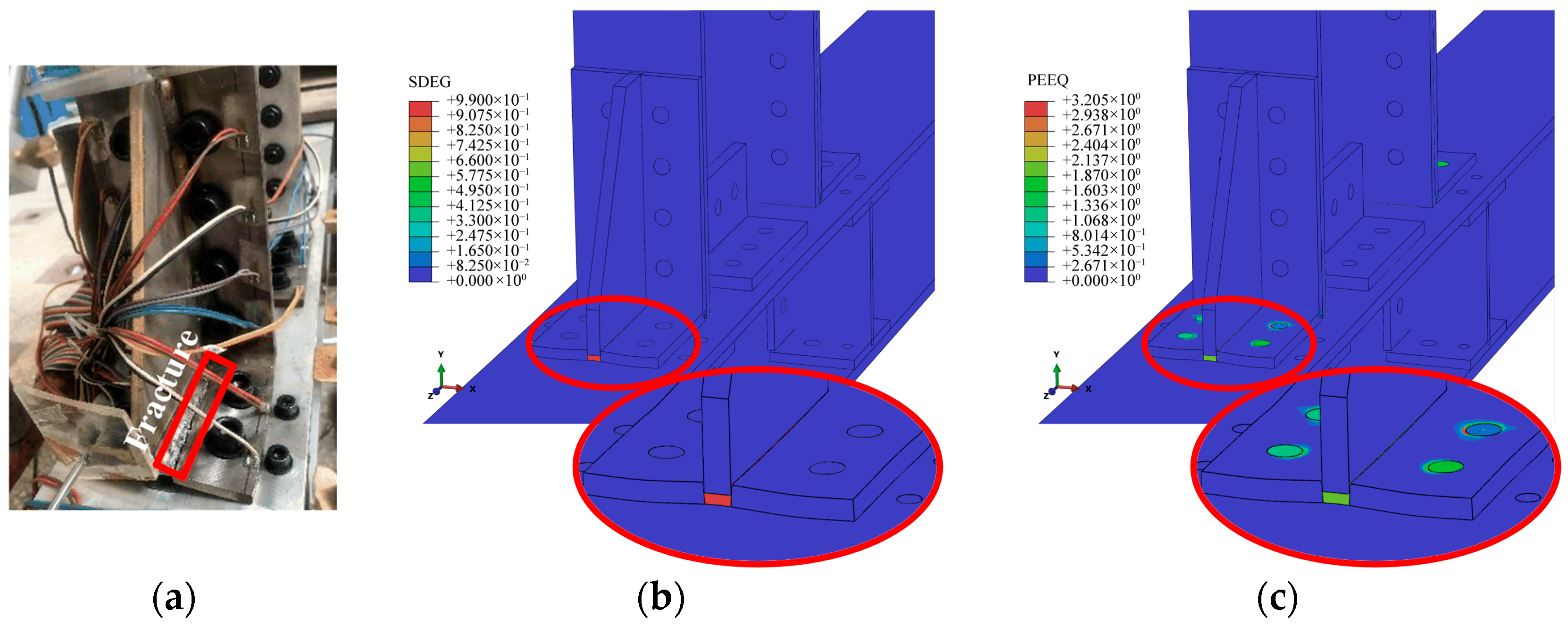

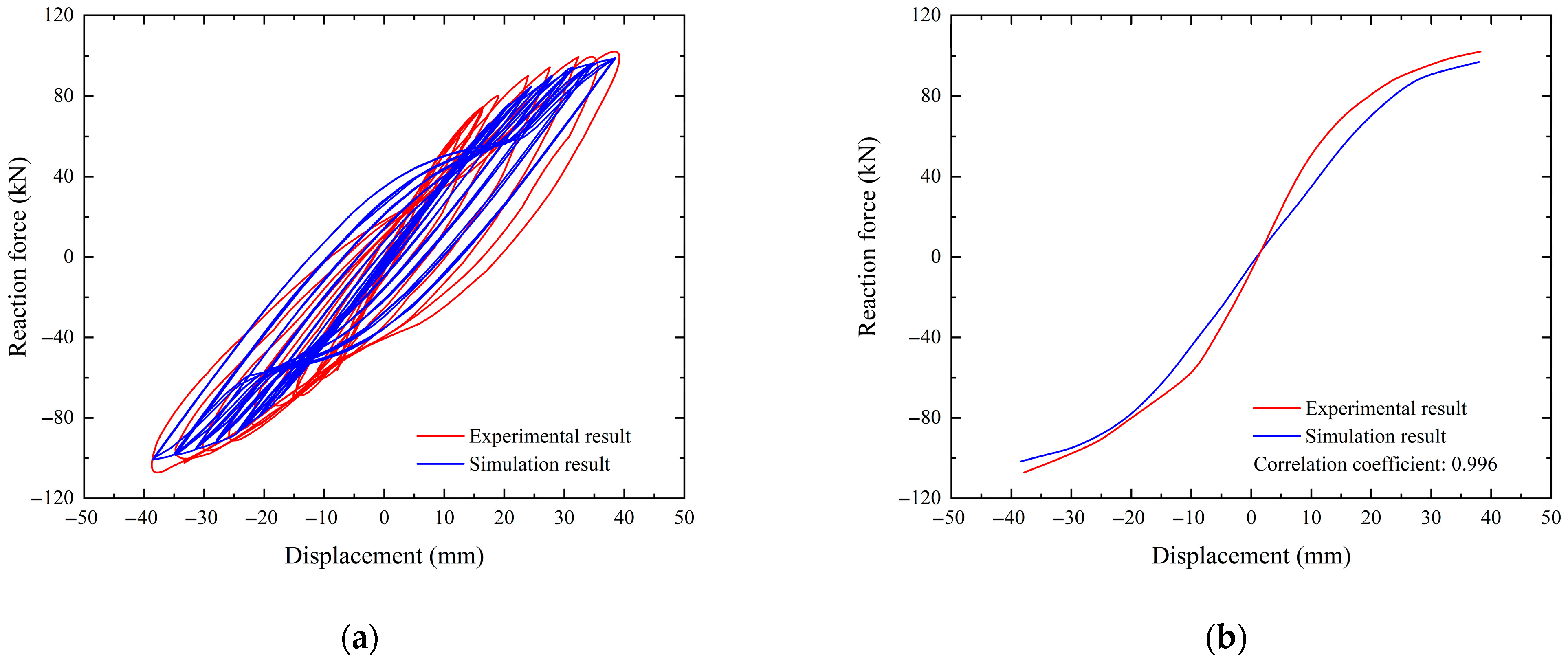

3.1.5. Validation of Numerical Model

3.2. Joint Parameter Working Conditions and Analysis Items

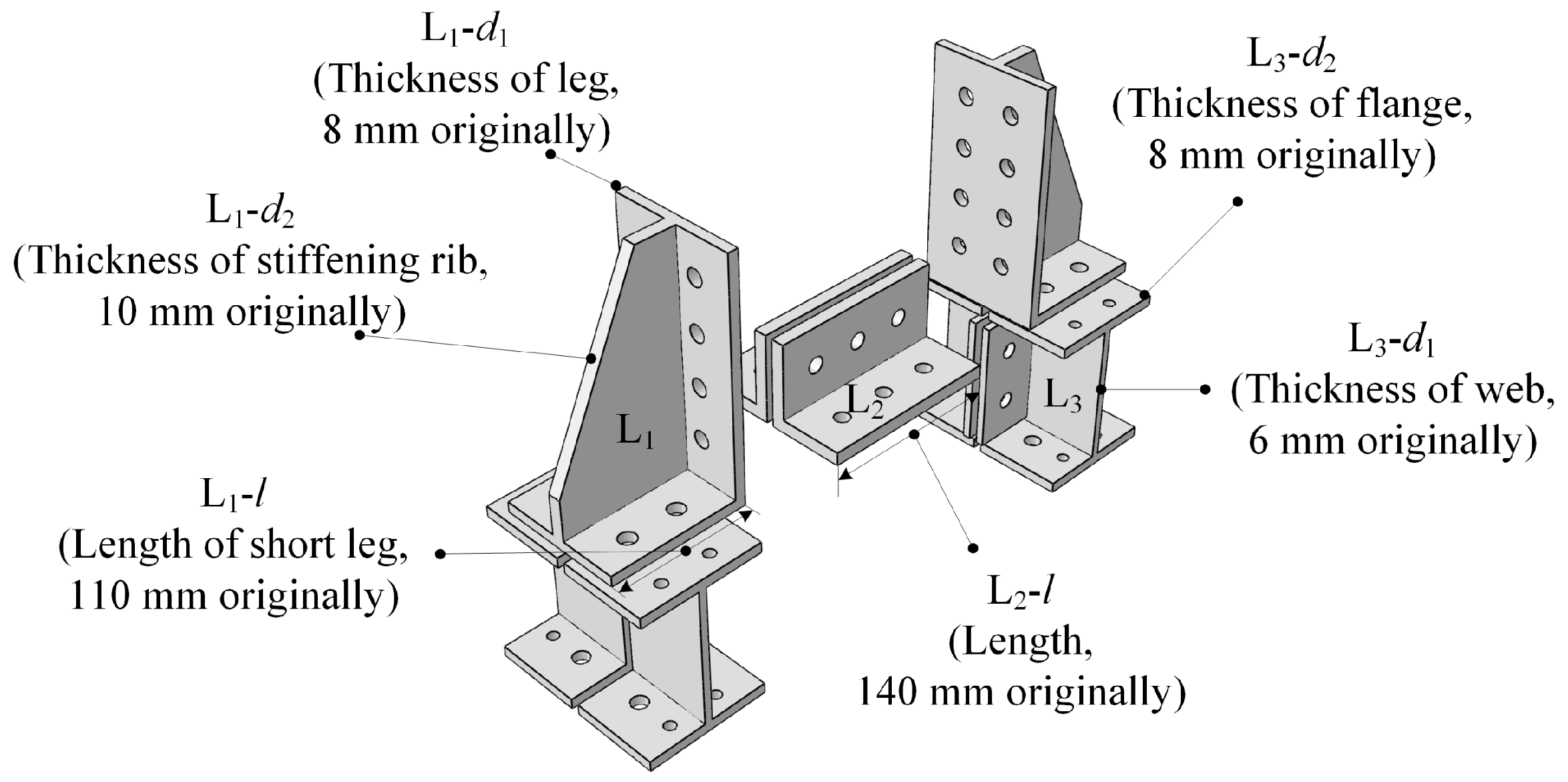

3.2.1. Joint Parameter Working Condition Settings

3.2.2. Simulation Result Analysis Method

4. Results and Discussion

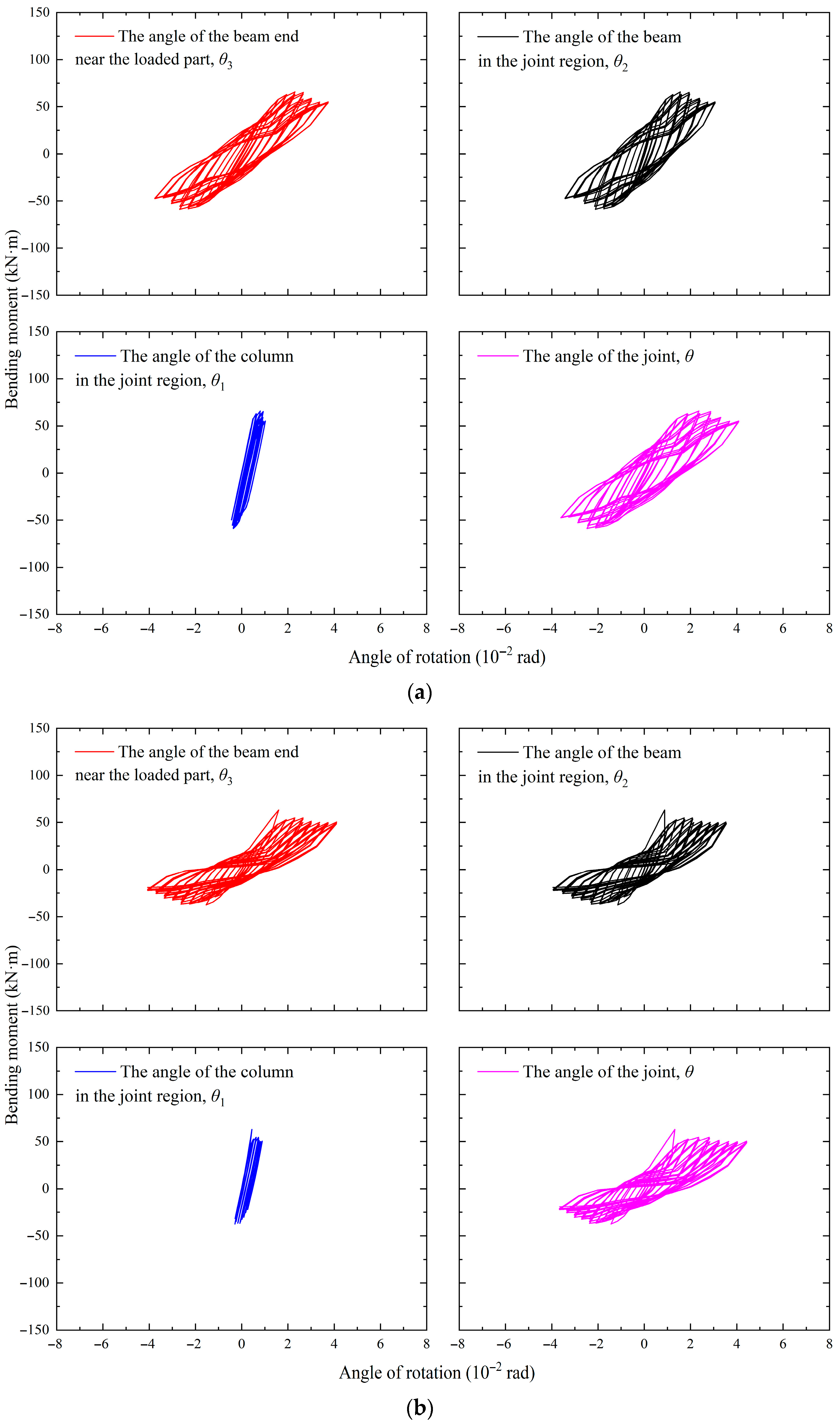

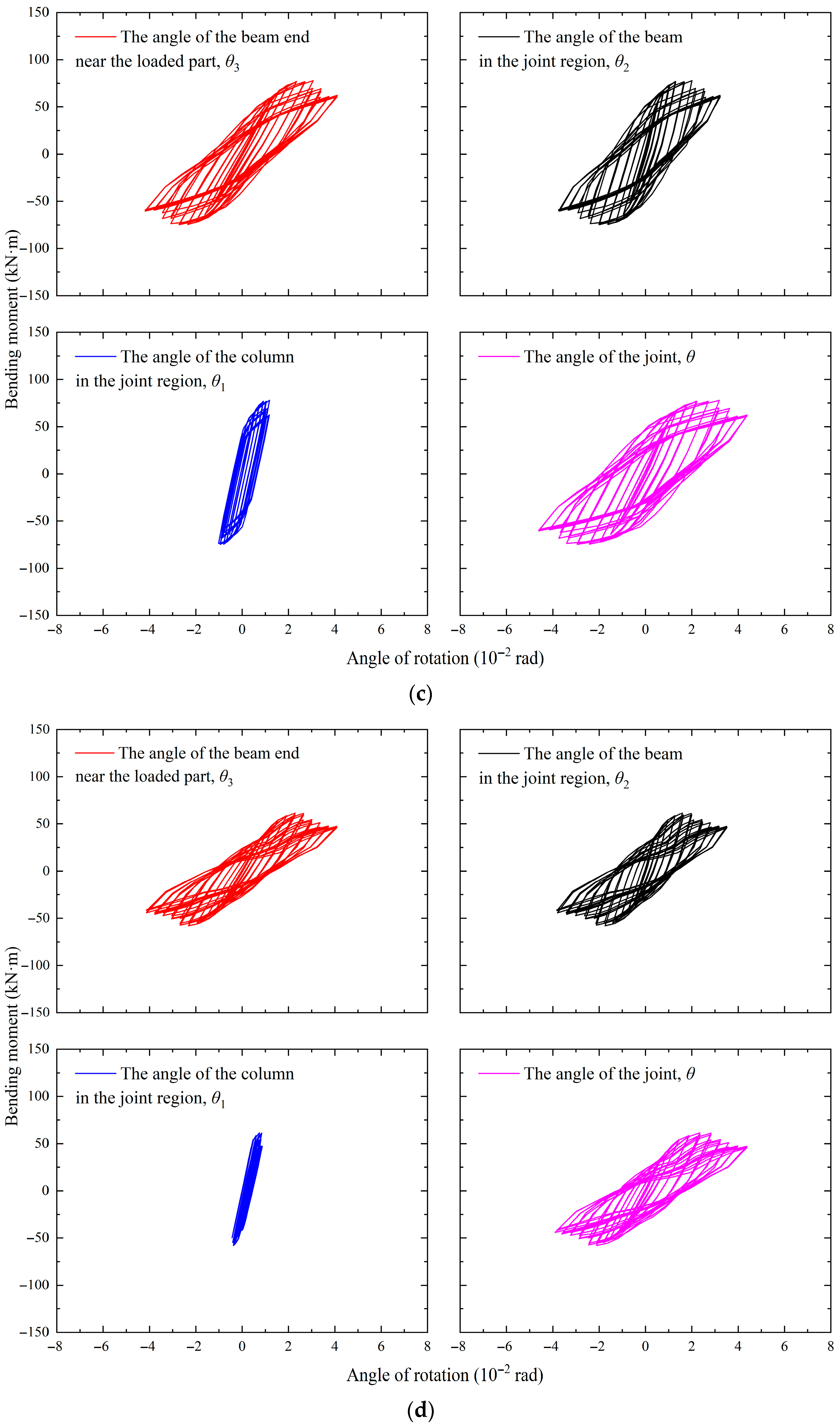

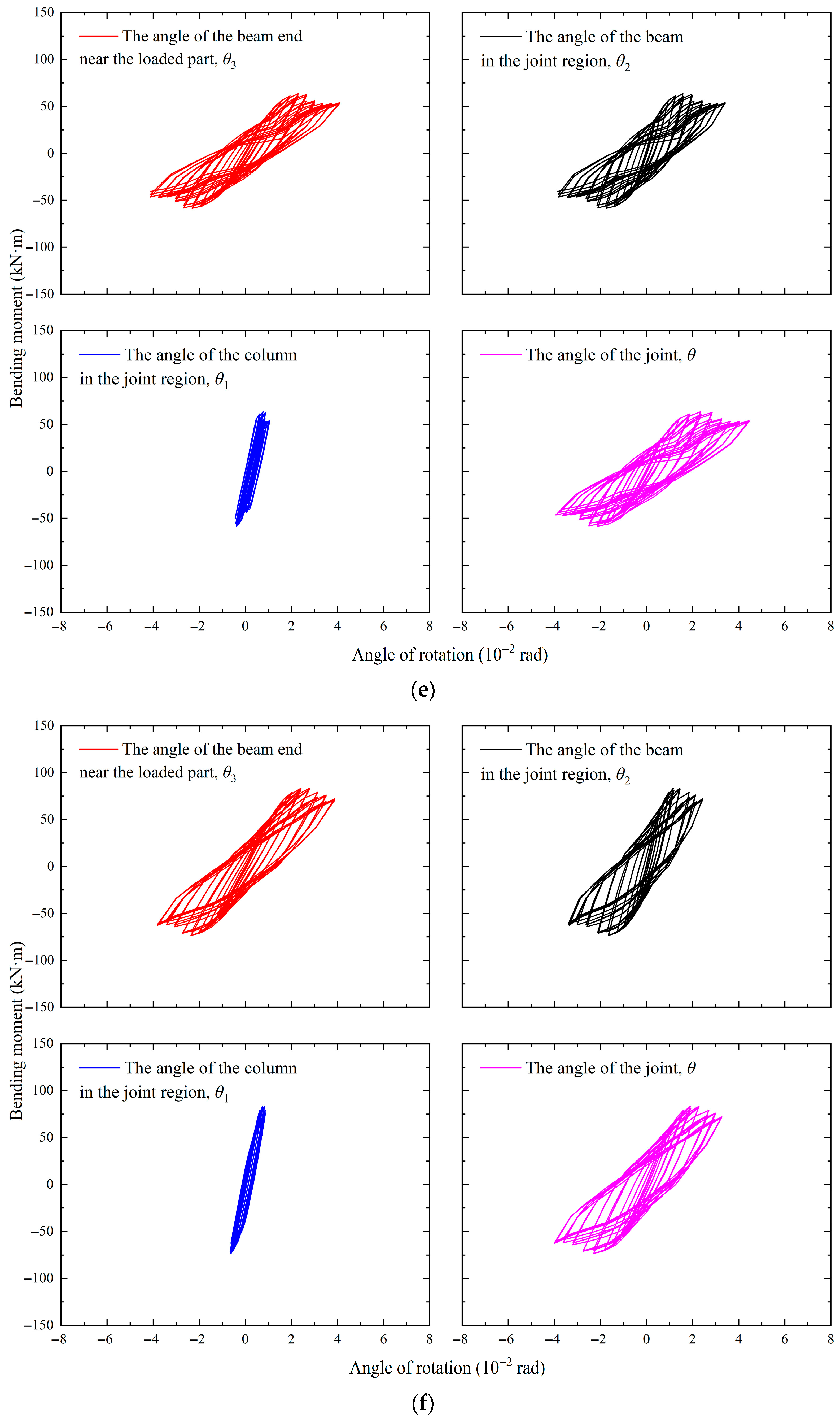

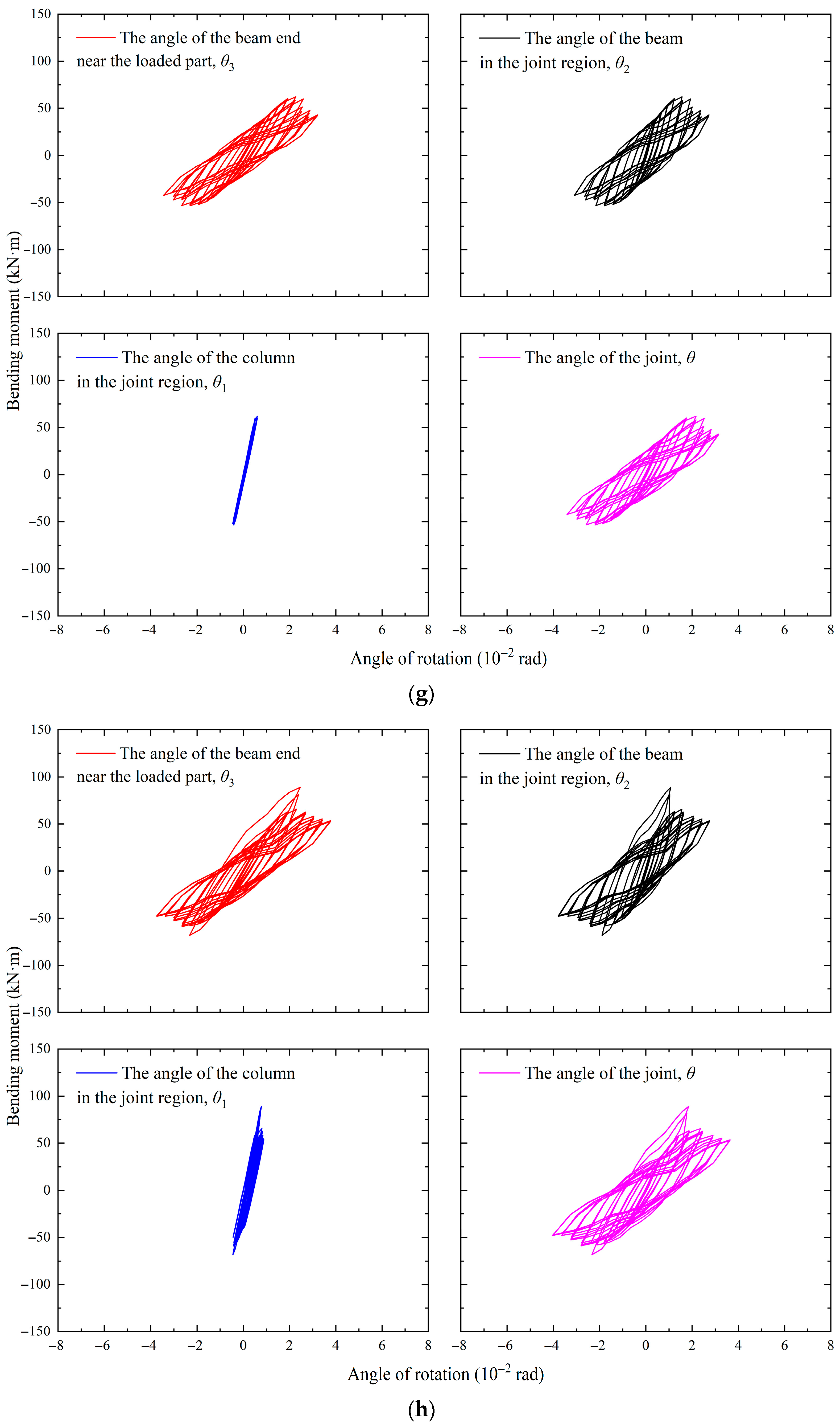

4.1. Analysis of Bending Moment–Rotation Hysteresis Curves

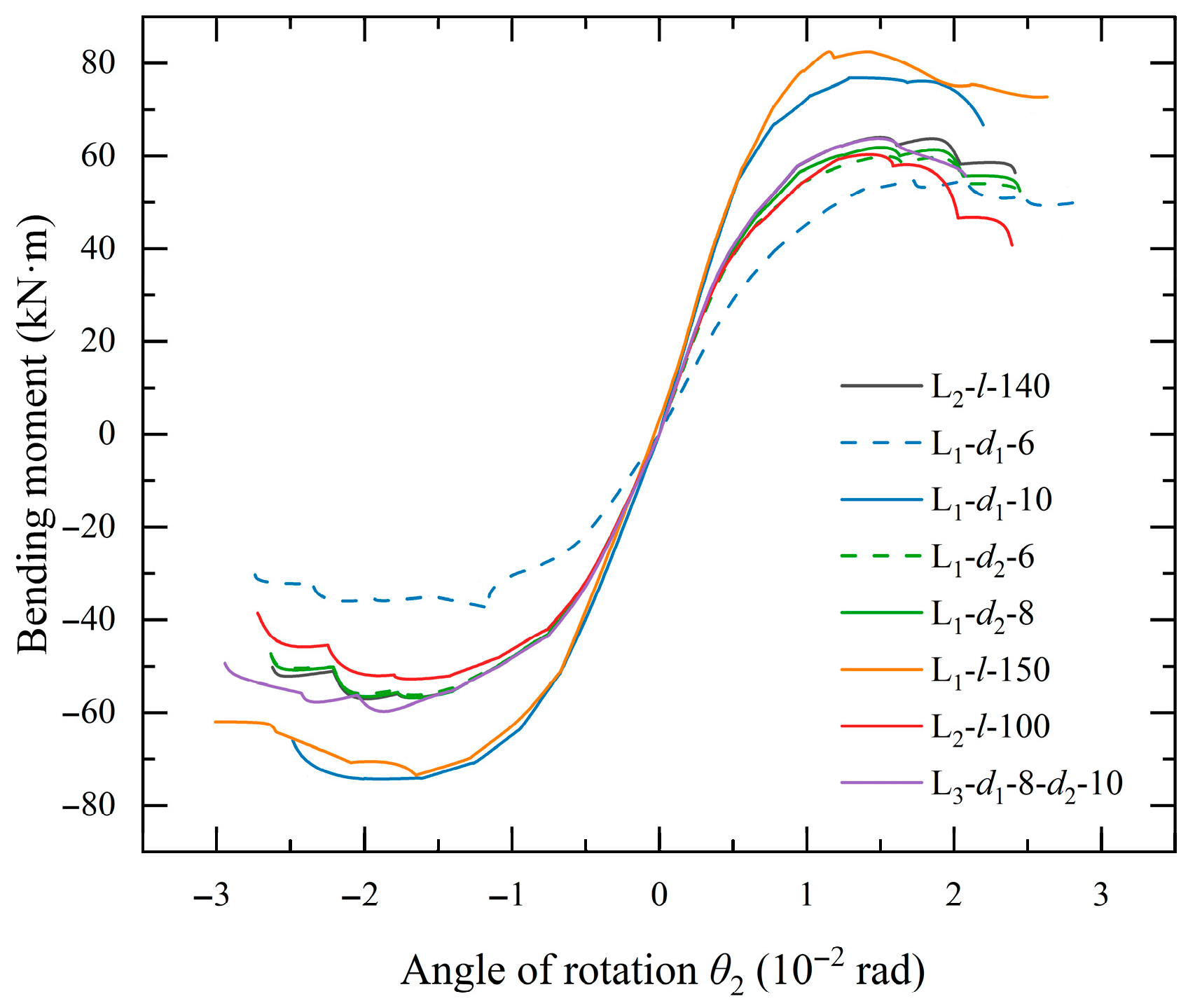

4.2. Analysis of Skeleton Curves

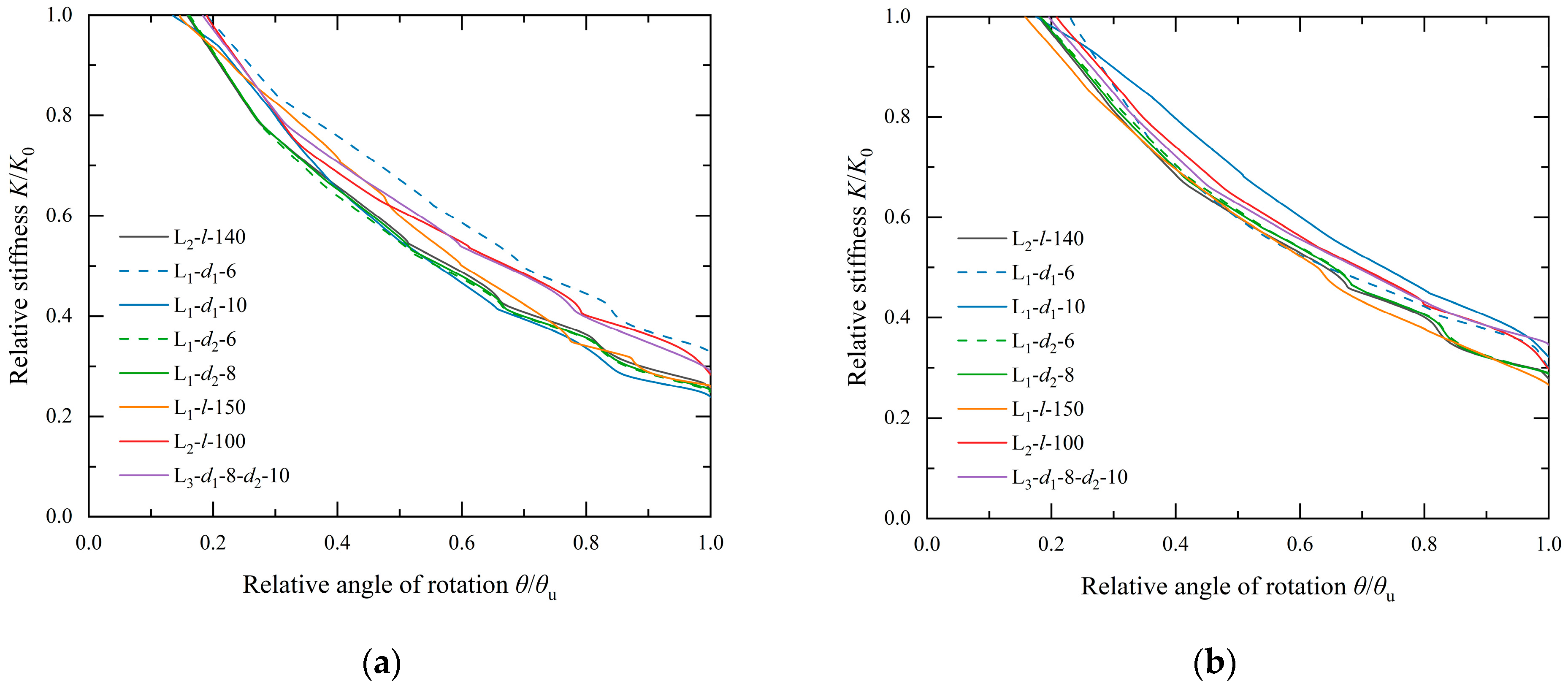

4.3. Analysis of Joint Stiffness Degradations

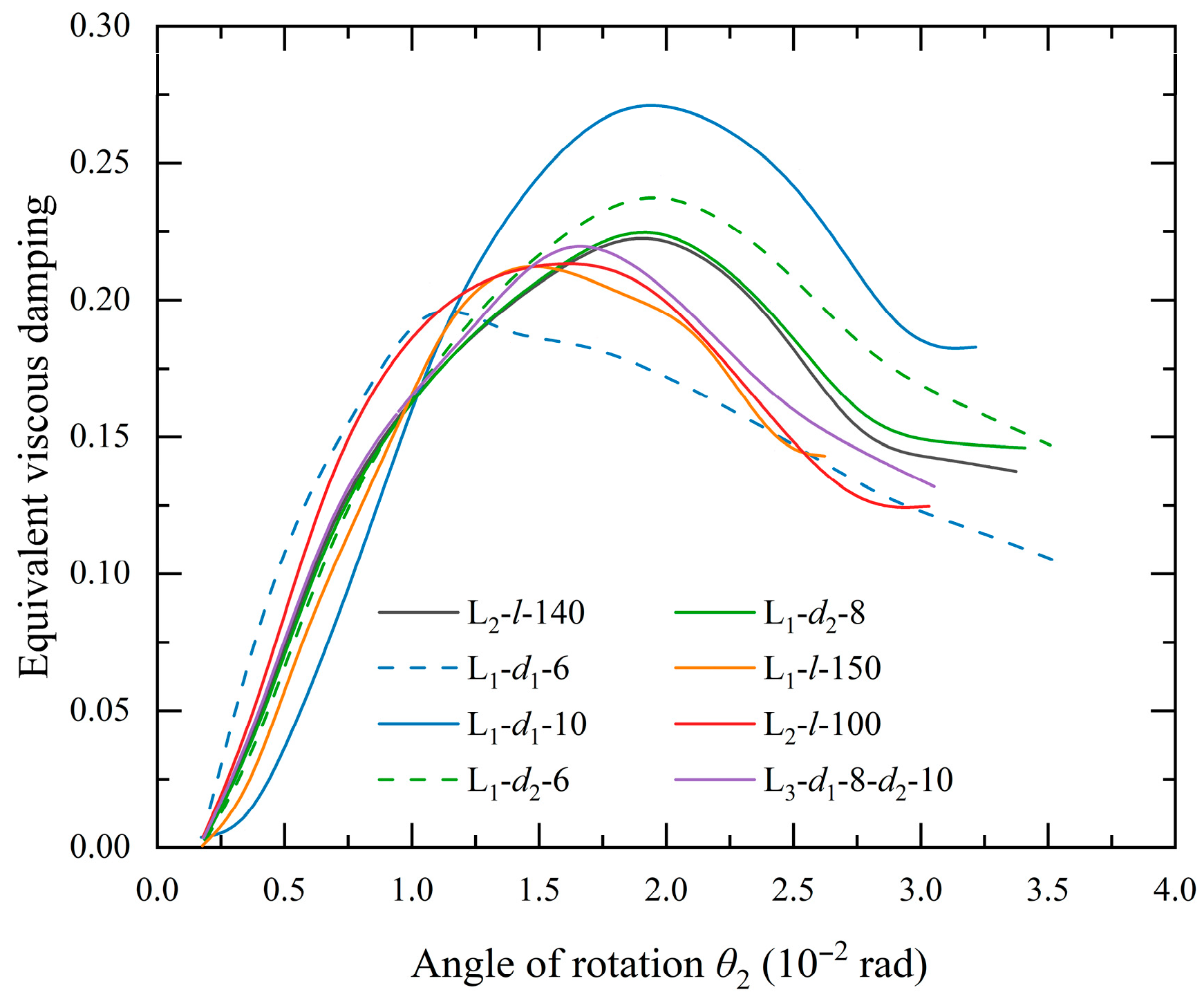

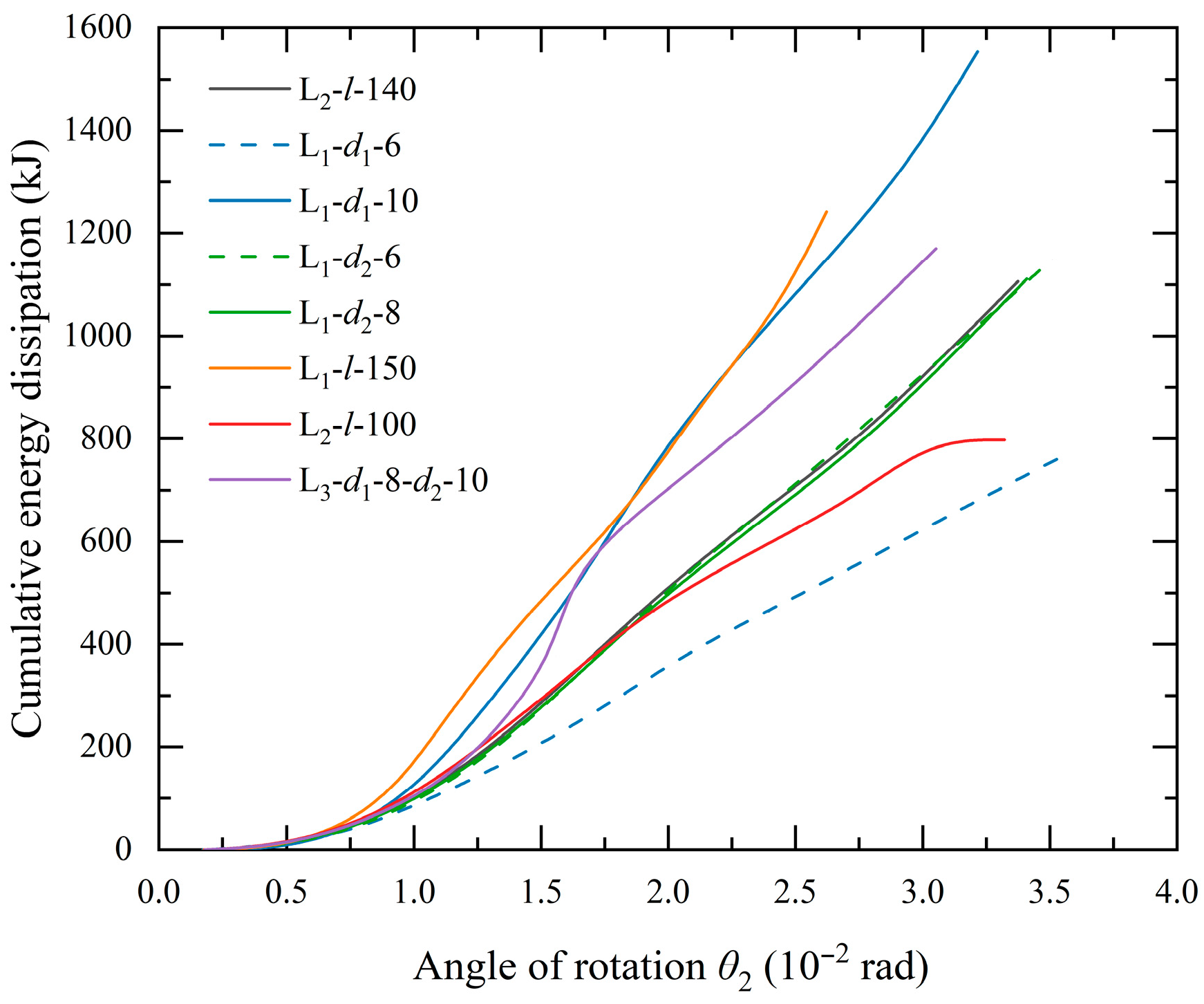

4.4. Analysis of Equivalent Viscous Damping Coefficient

4.5. Analysis of Ductility

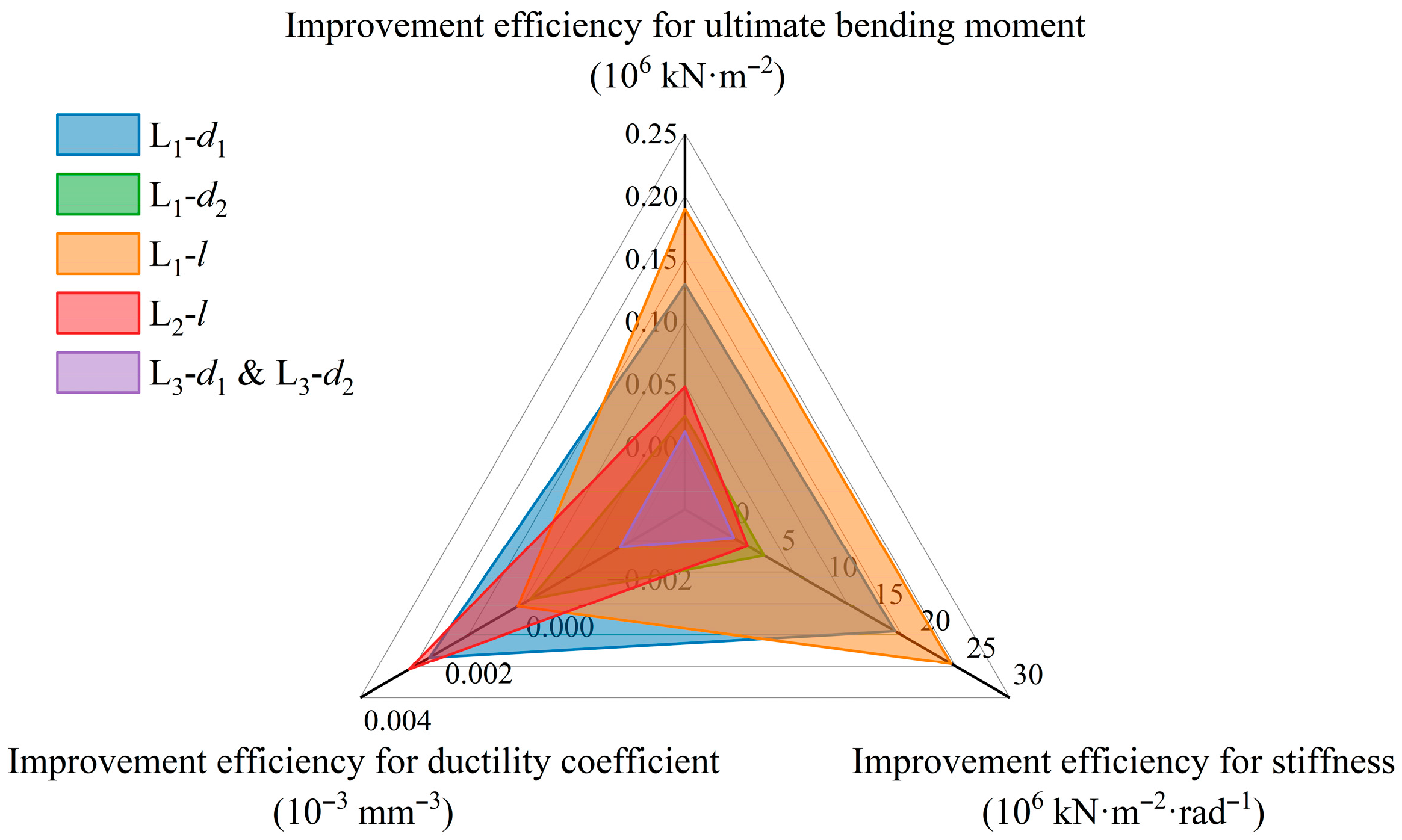

4.6. Analysis of Improvement Efficiency

5. Conclusions

- From the hysteresis curves of the beam end angle, the angle of the column in the joint region, the angle of the beam in the joint region, and the load bending moment, it can be seen that the contribution of the angle of the column in the joint region to the joint angle is very small and can be ignored. The hysteresis curves obtained from all working conditions initially exhibit a bow shape, but in the descending section after the peak bearing capacity, the shapes gradually transition to a reversed S-shape, except for the working conditions with a thickness of 10 mm for the long and short legs and a length of 150 mm for the short leg of the L-shaped connector between the beam flange and column flange.

- The thickness of the long and short legs of the L-shaped connector between the beam flange and column flange significantly affects the ultimate bearing capacity of the skeleton curve. The average influence is that an increase of 2 mm in this thickness increases the ultimate bearing capacity by 22.35–36.70%. Increasing the length of the short leg of the L-shaped connector between the beam flange and column flange is also effective in increasing the ultimate bearing capacity, with an increase of 40 mm resulting in a 25.92% increase in the ultimate bearing capacity. Furthermore, there are non-negligible differences in the positive and negative ultimate bending moment of the joints, suggesting that the direction with the lower bearing capacity should be taken as the reference, incorporating appropriate safety factors.

- The stiffness degradation curves of the aluminum alloy frame bolted connection joint exhibit a natural exponential decay trend. Under the condition where the joint bearing capacity decreases to 85%, the joint stiffness degrades to 23.85–32.57%. The initial stiffness of the two working conditions is the largest, with a thickness of 10 mm for the long and short legs and a length of 150 mm for the short leg of the L-shaped connector between the beam flange and column flange, exceeding 9500 kN·m/rad. Under major earthquake conditions with a structural elastic-plastic inter-story drift angle limit of 0.02 rad, the bearing capacity of all joint working conditions reaches near the peak value, accounting for 82.78–97.84% of the ultimate bearing capacity.

- Considering the relevant conclusions of the equivalent viscous damping, cumulative energy dissipation, and ductility coefficient of the joints, increasing the thickness of the long and short legs of the L-shaped connector between the beam flange and column flange is the most effective way to improve the seismic performance of the joints. For every 2 mm increase in the thickness of the long and short legs, the equivalent viscous damping and ductility coefficient increase by 20.25% and 11.46%, respectively.

- From an economic perspective, the improvement efficiency analysis establishes that increasing the length of the short leg of the L-shaped connector between the beam flange and column flange is the most efficient single measure for enhancing strength and stiffness, while increasing the thickness of the long and short legs of the L-shaped connector between the beam flange and column flange offers the best comprehensive improvement.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, R. Study on the Hysteretic Performance of High-Strength Bolted Beam-Column Joints with Aluminum Alloy Frames. Master’s Thesis, Fujian University of Technology, Fuzhou, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y. Study on Fatigue Performance of Aluminum Alloy Frame Structure Beam-Column Joints. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an Technological University, Xi’an, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Buntrock, D. Toyo Ito and Masato Araya’s experiments in the structural use of aluminium. J. Archit. 2016, 21, 24–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyrakos, C.C.; Ermopoulos, J. Development of aluminum load-carrying space frame for building structures. Eng. Struct. 2005, 27, 1942–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, Z.; Ouyang, Y. Engineering applications and research progress of low-rise aluminum alloy frames. Eng. Mech. 2023, 40, 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- AluHouse. Available online: https://www.aluhouse.com/en/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Rao, B.; Huang, L.; Su, D.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Geng, L.; Li, L.; Gao, W.; Li, F. Seismic performance of bolted connection in aluminum alloy frame. Henan Sci. 2025, 43, 469–481. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, C. Study on the hysteretic behavior of side plate reinforced beam-to-column connections in steel frame. J. Disaster Prev. Mitig. Eng. 2018, 38, 336–344. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Bu, Y.; Fan, S.; Zheng, B. Experimental investigation and numerical analysis of pin-ended extruded aluminium alloy unequal angle columns. Eng. Struct. 2020, 215, 110694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ji, J.; Yang, L.; Wu, M. Some important concepts and research bases of code for design of aluminum structures. J. Build. Struct. 2009, 30, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Ma, J.; Han, R.; Chen, K. Shearing low-cycle fatigue test and life prediction of the aluminum alloy bolted connection. J. Tianjin Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 2019, 52, 142–147. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Ye, Z.; Guo, X. Experimental research on high strength bolted zigzag-plate connections of aluminum alloy members. J. Tianjin Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 2016, 44, 1333–1339+1355. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Peng, L.; He, X.; Yang, J. Experimental and numerical analyses on mechanical properties of aluminum alloy L-shaped joints under cyclic load. Eng. Struct. 2021, 245, 112854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. Experimental and Numerical Study on the Mechanical Properties of L-Shaped Aluminum Alloy Beam-Column Joints. Master’s Thesis, Guangxi University, Nanning, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Guo, X.; Luo, Y. Load-bearing capacity of aluminum alloy T-stub joints. J. Tongji Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2012, 40, 1445–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalberg, A. Design of aluminium beam ends with flange copes. Thin-Walled Struct. 2015, 94, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ma, H.; Liew, J.Y.R.; Fan, F. Testing of aluminum alloyed bolted joints for connecting aluminum rectangular hollow sections in reticulated shells. Eng. Struct. 2020, 218, 110848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çam, G.; İpekoğlu, G. Recent developments in joining of aluminum alloys. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 91, 1851–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhi, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X. Numerical and parametric study on fracture behaviour and effect of friction on resistance of aluminium alloy shear connections. Thin-Walled Struct. 2023, 188, 110851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Ouyang, Y. Structural behaviour of the aluminium alloy Temcor joints and Box-I section hybrid gusset joints under combined bending and shear. Eng. Struct. 2021, 249, 113380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Feng, R.; Shao, K.; Zhang, Q. Study on the seismic performance of T-type members connection of aluminum alloy frame beams and columns. Build. Sci. 2023, 39, 90–100. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Shi, Y. Tests and parametric analysis of aluminum alloy bolted joints of different material types. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 185, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Qiu, L.; Luo, Y.; Zheng, B. Experimental study on flexural capacity of aluminum alloy plate joints. J. Hunan Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2014, 41, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, B.; Huang, L.; Su, D.; Li, L.; Gao, W.; Li, F. Analysis of the influence of constitutive parameters on the simulation accuracy of mechanically connected joints in aluminum alloy frame structures. Jiangxi Sci. 2025, 43, 532–540+546. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Yam, M.C.; Ke, K.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, H.; Gu, Z. Behaviour insights on damage-control composite beam-to-beam connections with replaceable elements. Steel Compos. Struct. 2023, 46, 773–791. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Chen, Y.; Ke, K.; Shao, T.; Yam, M.C. Development of a connection equipped with fuse angles for steel moment resisting frames. Eng. Struct. 2022, 265, 114503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; He, P.; Wang, J.; Pan, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Baniotopoulos, C.C. Mechanical characteristic and stress-strain modelling of friction stir welded 6061-T6 aluminium alloy butt joints. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 198, 111645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Kong, G.; Zhang, L. Low-temperature tensile behaviours of 6061-T6 aluminium alloy: Tests, analysis, and numerical simulation. Structures 2023, 56, 105054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiansky, B. Discussion: “New method of analyzing stresses and strains in work-hardening plastic solids” (Prager, William, 1956, ASME 23, pp. 493–496). J. Appl. Mech. 1957, 24, 481–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, H. A modification of Prager’s hardening rule. Q. Appl. Math. 1959, 17, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaboche, J.L. Time-independent constitutive theories for cyclic plasticity. Int. J. Plast. 1986, 2, 149–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.K.; Sivaprasad, S.; Dhar, S.; Tarafder, M.; Tarafder, S. Simulation of cyclic plastic deformation response in SA333 C–Mn steel by a kinematic hardening model. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2010, 48, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Jin, K.; Kou, Y. An improved kinematic hardening rule describing the effect of loading history on plastic modulus and ratcheting strain. Acta Mech. 2023, 234, 1757–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Niu, Y.; Quan, G.; Gao, H.; Ye, J. Development of new types of bolted joints for cold-formed steel moment frame buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 50, 104171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AISC 341-22; Seismic Provisions for Structural Steel Buildings. American Institute of Steel Construction: Chicago, IL, USA, 2022.

- Weiss, J.; Knezevic, M. Effects of element type on accuracy of microstructural mesh crystal plasticity finite element simulations and comparisons with elasto-viscoplastic fast Fourier transform predictions. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2024, 240, 113002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Burgess, I.W.; Davison, J.B.; Plank, R.J. Numerical simulation of bolted steel connections in fire using explicit dynamic analysis. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2008, 64, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B. Structural Seismic Test; Seismological Press: Beijing, China, 1989; pp. 36–48. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.; Zhou, X. Experimental study on the seismic behavior of concentrically braced steel frames with extended end-plate bolted connections. Sci. Prog. 2020, 103, 0036850420952289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Material | Young’s Modulus (GPa) | Yield Strength (MPa) | Ultimate Strength (MPa) | Elongation at Break |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6061-T6 aluminum alloy | 70.363 | 291 | 304.5 | 12 |

| S304 stainless steel | 197.26 | 316 | 721 | 60 |

| Working Condition | Variable | L1-d1 | L1-d2 | L1-l | L2-l | L3-d1 | L3-d2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L2-l-140 | / | 8 | 10 | 110 | 140 | 6 | 8 |

| L1-d1-6 | L1-d1 | 6 | 10 | 110 | 140 | 6 | 8 |

| L1-d1-10 | 10 | 10 | 110 | 140 | 6 | 8 | |

| L1-d2-6 | L1-d2 | 8 | 6 | 110 | 140 | 6 | 8 |

| L1-d2-8 | 8 | 8 | 110 | 140 | 6 | 8 | |

| L1-l-150 | L1-l | 8 | 10 | 150 | 140 | 6 | 8 |

| L2-l-100 | L2-l | 8 | 10 | 110 | 100 | 6 | 8 |

| L3-d1-8-d2-10 | L3-d1 & L3-d2 | 8 | 10 | 110 | 140 | 8 | 10 |

| Working Condition | Variable | Corresponding Value (mm) | Positive Ultimate Bending Moment (kN·m) | Positive Corresponding Angle (10−2 rad) | Negative Ultimate Bending Moment (kN·m) | Negative Corresponding Angle (10−2 rad) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L2-l-140 | L1-d1 | 8 | 65.81 | 1.56 | −58.90 | −2.11 |

| L1-d1-6 | 6 | 54.70 | 2.08 | −36.53 | −1.92 | |

| L1-d1-10 | 10 | 77.91 | 2.01 | −74.67 | −2.00 | |

| L2-l-140 | L1-d2 | 10 | 65.81 | 1.56 | −58.90 | −2.11 |

| L1-d2-6 | 6 | 61.44 | 1.59 | −58.05 | −1.74 | |

| L1-d2-8 | 8 | 63.50 | 1.58 | −58.48 | −1.74 | |

| L2-l-140 | L1-l | 110 | 65.81 | 1.56 | −58.90 | −2.11 |

| L1-l-150 | 150 | 83.48 | 1.16 | −73.56 | −1.65 | |

| L2-l-140 | L2-l | 140 | 65.81 | 1.56 | −58.90 | −2.11 |

| L2-l-100 | 100 | 61.97 | 1.56 | −53.56 | −1.79 | |

| L2-l-140 | L3-d1 & L3-d2 | 6 & 8 | 65.81 | 1.56 | −58.90 | −2.11 |

| L3-d1-8-d2-10 | 8 & 10 | 65.71 | 1.56 | −63.24 | −1.89 |

| Working Condition | Positive Initial Stiffness (kN·m·rad−1) | Negative Initial Stiffness (kN·m·rad−1) | Average Stiffness (kN·m·rad−1) | Positive θu (10−2 rad) | Negative θu (10−2 rad) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L2-l-140 | 9192 | 6885 | 8083 | 2.42 | −2.62 |

| L1-d1-6 | 6103 | 4503 | 5334 | 2.50 | −2.35 |

| L1-d1-10 | 10,897 | 8240 | 9569 | 2.56 | −2.83 |

| L1-d2-6 | 8680 | 6733 | 7707 | 2.45 | −2.59 |

| L1-d2-8 | 8995 | 6830 | 7913 | 2.42 | −2.59 |

| L1-l-150 | 11,313 | 8908 | 10,111 | 2.42 | −2.39 |

| L2-l-100 | 9034 | 6795 | 7915 | 2.00 | −2.25 |

| L3-d1-8-d2-10 | 9280 | 6970 | 8125 | 2.08 | −2.63 |

| Working Condition | Positive θy (10−2 rad) | Positive Ductility Coefficient | Negative θy (10−2 rad) | Negative Ductility Coefficient | Average Ductility Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L2-l-140 | 0.94 | 2.57 | −1.12 | 2.34 | 2.46 |

| L1-d1-6 | 1.14 | 2.19 | −1.04 | 2.26 | 2.23 |

| L1-d1-10 | 0.87 | 2.94 | −1.09 | 2.60 | 2.77 |

| L1-d2-6 | 0.93 | 2.63 | −1.11 | 2.33 | 2.48 |

| L1-d2-8 | 0.93 | 2.60 | −1.11 | 2.33 | 2.47 |

| L1-l-150 | 0.90 | 2.69 | −1.06 | 2.25 | 2.47 |

| L2-l-100 | 0.94 | 2.13 | −1.00 | 2.25 | 2.19 |

| L3-d1-8-d2-10 | 0.94 | 2.21 | −1.40 | 1.88 | 2.05 |

| Working Condition | Change in Total Volume 1 | Change in Average Ultimate Bending Moment 2 | Change in Average Stiffness 3 | Change in Average Ductility Coefficient 4 | Joint Parameter | Improvement Efficiency for Ultimate Bending Moment | Improvement Efficiency for Stiffness | Improvement Efficiency for Ductility Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L2-l-140 | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | / |

| L1-d1-6 | −119.2 | −16.74 | −2749 | −0.23 | L1-d1 | 0.13 | 17.65 | 0.0023 |

| L1-d1-10 | +120.8 | +13.935 | +1486 | +0.31 | ||||

| L1-d2-6 | −106.512 | −2.61 | −376 | +0.02 | L1-d2 | 0.025 | 3.53 | −0.00019 |

| L1-d2-8 | −53.256 | −1.365 | −170 | +0.01 | ||||

| L1-l-150 | +85.6 | +16.165 | +2028 | +0.01 | L1-l | 0.19 | 23.69 | 0.00012 |

| L2-l-100 | −96 | −4.59 | −168 | −0.27 | L2-l | 0.048 | 1.75 | 0.0028 |

| L3-d1-8-d2-10 | +170.456 | +2.12 | +42 | −0.41 | L3-d1 & L3-d2 | 0.012 | 0.25 | −0.0024 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rao, B.; Wang, Z.; Rao, W.; Que, Z.; Li, F.; Wang, J.; Gao, W. Seismic Performance of T-Shaped Aluminum Alloy Beam–Column Bolted Connections: Parametric Analysis and Design Implications Based on a Mixed Hardening Model. Buildings 2025, 15, 4324. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234324

Rao B, Wang Z, Rao W, Que Z, Li F, Wang J, Gao W. Seismic Performance of T-Shaped Aluminum Alloy Beam–Column Bolted Connections: Parametric Analysis and Design Implications Based on a Mixed Hardening Model. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4324. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234324

Chicago/Turabian StyleRao, Bangzheng, Zhongmin Wang, Weiguo Rao, Zhongping Que, Fengzeng Li, Jin Wang, and Wenyuan Gao. 2025. "Seismic Performance of T-Shaped Aluminum Alloy Beam–Column Bolted Connections: Parametric Analysis and Design Implications Based on a Mixed Hardening Model" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4324. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234324

APA StyleRao, B., Wang, Z., Rao, W., Que, Z., Li, F., Wang, J., & Gao, W. (2025). Seismic Performance of T-Shaped Aluminum Alloy Beam–Column Bolted Connections: Parametric Analysis and Design Implications Based on a Mixed Hardening Model. Buildings, 15(23), 4324. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234324