1. Introduction

Since the Industrial Revolution, the Linear Economy (LE) has determined the model of production and consumption [

1]. The LE model, known for its “take-make-use-dispose” process, is still applied today in the built environment, despite ongoing advancements in energy efficiency within the sector [

2]. Furthermore, this production model in the built environment causes the construction industry to be one of the largest consumers of resources and raw materials on the planet [

2]. The construction industry is estimated to consume more than 50% of the planet’s natural resources [

3] and is responsible for one-third of greenhouse gas emissions [

4], and its demand is expected to increase alongside population growth [

5].

The Circular Economy (CE) emerges as a production and consumption model that decouples economic growth from the extraction of natural resources [

5,

6], while maintaining materials and products at their highest value for as long as possible [

6]. The creation of circular solutions involves the development of Material Passports (MP), a tool for embedding CE principles [

7]. In the construction industry, MPs are not yet a conventional practice [

1], and there are still few studies on the introduction of circular practices in the sector [

8].

In the built environment, the MP is a digital documentation [

9,

10]. Building Information Modeling (BIM) can be seen as an enabler for the incorporation of circular principles in building design [

11], as it can be defined as a concept that encompasses technologies and processes for an integrated design practice. The modeling refers to the creation of a physical and operational representation of a building and has the capacity to store information and share essential data throughout the lifecycle of the built project [

12]. In this way, BIM has the potential to support the development and management of an MP [

13].

It is possible to generate BIM-based MPs either during the initial design phase [

14] or in the final end-of-life phases of a building [

15]. When integrated with BIM and used in the early design stages, the MP plays a crucial role in optimizing these phases [

16]. In the final stages, the existence of an MP presents an advantage in terms of recycling and reuse of materials; it supports circularity and sustainability in the construction sector [

17] and functions as an inventory [

16].

Several authors have developed BIM-based MP models. Honic, Kovacic and Rechberger (2019) [

16] define the MP through indicators such as the building’s recyclability percentage and simplified Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) indicators. Atta, Bak-houm and Marzouk (2021) [

18] use three sustainability indicators (deconstructability score, recovery score, and environmental score), which are calculated mathematically and automatically using the Dynamo tool. Sanchez et al. (2024) [

17] use Revit and its parametric modeling to insert 27 relevant parameters for building disassembly. Xia and Xu (2023) [

19] use the building’s BIM model to extract the list of materials, and all the feeding and automation of the MP is carried out within the Google workspace environment.

CE in the built environment can benefit significantly from BIM, a powerful and essential tool for creating and managing digital information such as MPs [

11]. BIM promotes collaboration, data accuracy, and sustainability [

20], enabling a more transparent, traceable, and efficient production chain [

21]. Moreover, it is a technology capable of integrating the dimensions of sustainability, such as environmental, economic, and social aspects [

22].

This article aims to develop a MP for a wood frame panel used by the company Tecverde in Curitiba, Brazil. The building “1.0 House”, from the company’s project catalog, was modeled in the 2024 version of the Revit software following the instructions provided in a technical evaluation document called DATec Nº 020-E [

23]. The DATec (acronym in Portuguese for “Documento de Avaliação Técnica”) is a Brazilian technical document designed to provide construction professionals with an impartial, evidence-based assessment of a product. It includes key data on performance, installation requirements, usage, and maintenance to support technically grounded decision-making [

24].

Innovative products and systems considered innovative must have this document, as they are not yet covered by the current Brazilian technical standards (ABNT). The product titled “Structured system in light solid sawn timber components—Tecverde (light wood frame type)” is intended for the construction of detached and semi-detached single-family housing units, as well as multifamily buildings up to four stories high.

Several studies have proposed BIM-based MPs to support circular practices in the construction sector, most focused on conventional building typologies and are concentrated in high-income countries with standardized construction systems. There is a lack of empirical research applying MPs in emerging economies, particularly in Latin America, where industrialized timber construction remains underrepresented in the literature. Moreover, limited attention has been given to the integration of MPs into national certification frameworks such as Brazil’s DATec and their implementation in early design stages using widely accessible tools like Revit and Dynamo. Addressing this gap, the present study develops a BIM-based MP for a wood frame panel used in Tecverde’s “1.0 House” prototype in Brazil. The MP includes 49 parameters grouped into nine categories and is generated through a Dynamo script applied to a BIM model developed in Revit 2024, in accordance with the specifications of DATec Nº 020-E. By aligning digital modeling, open data, and CE principles, this study contributes to advancing practical, scalable approaches to circular construction in the Global South.

The paper is structured in six sections. After the introduction (

Section 1), a literature review background (

Section 2) is presented.

Section 3 introduces the methodological approach, followed by

Section 4, which presents the development of the MP.

Section 5 presents the implementation of the MP in Tecverde’s 1.0 House and the results that were obtained with the artifact.

Section 6 and

Section 7 present the discussion and conclusion with the most important contributions to the research.

3. Research Methodology

This investigation is classified as exploratory in nature, as its objective is to provide greater familiarity with the topic and, consequently, make it more explicit [

37]. It is situated within the scientific method known as Design Science Research (DSR), as its unit of analysis is an artifact.

The DSR process consists of a set of structured activities that result in the creation of an innovative product, whose primary purpose is utility. This product can take various forms, including artifacts, methods, constructs, models, and instantiations [

38]. Considering the research problem, which involves generating an MP and doing the application in a wood frame panel, the artifact to be developed can be classified as a method—that is, a set of steps, in this case an algorithm, used to perform tasks based on a set of constructs [

39]. Furthermore, the method is employed as an approach to bridge the gap between theory and practice [

40].

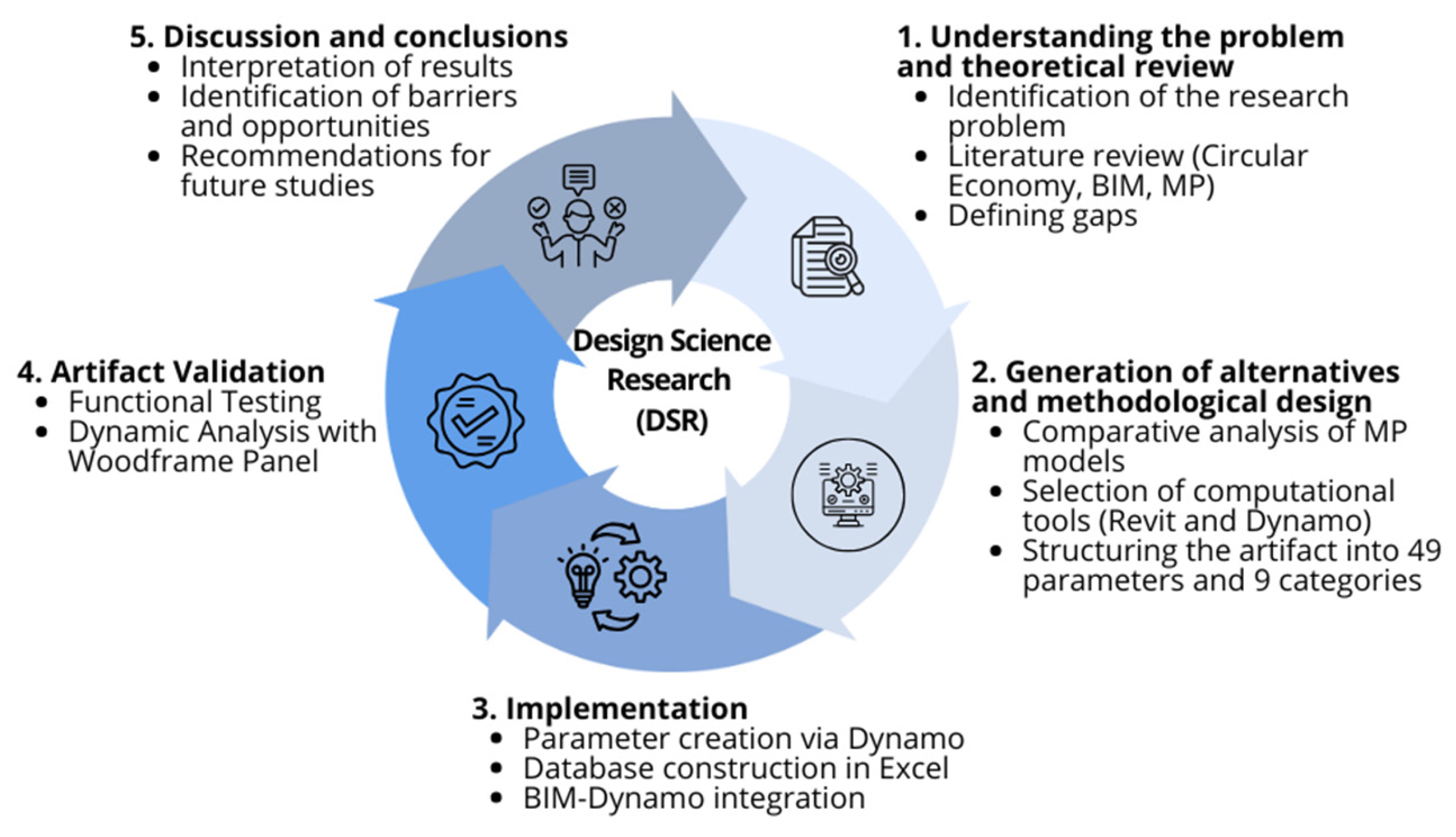

The DSR process is described in five steps. The first step is about understanding the problem and is shown in

Section 3.1 below. The second step refers to the problem’s alternatives and is shown in

Section 3.2 below. The development of the artifact and functional validation are shown in

Section 4. The dynamic analysis and results are shown in

Section 5.

Figure 1 presents the research protocol based on Santos (2018) [

41], Walls, Wyidmeyer and Sawy (1992) [

42], Gregor and Jones (2007) [

43], and Alturki, Gable and Bandara (2011) [

44].

3.1. Comprehension of the Problem

While MPs are important tools to embed CE principles in construction, BIM is a technology to enhance this goal. Although several conceptual studies propose BIM-based MPs to support circular practices, there is a scarcity of empirical research in Latin America countries like Brazil, where industrialized timber construction is notably underrepresented. This gap hinders the development of standardized workflows and decision-making tools that could drive CE adoption in Brazil.

3.2. Generation of Alternatives

The literature on MP highlights the lack of consensus regarding the definition of the concept and the scope of information that should be stored in the tool, representing a significant opportunity for academic research [

45]. Several MP models have been proposed, each presenting specific characteristics in terms of data, indicators, and technological structure. For instance, Munaro and Tavares (2021) [

1] structure the MP into nine data categories aimed at the recovery and reuse of materials and components, although no specific computational tools are defined. Honic et al. (2019a) [

16] organize the data according to building components and establish three indicators (recyclability, LCA data, and amount of recyclable material), with a pre-defined technological structure. Atta, Bakhoum and Marzouk (2021) [

18] employ three mathematical indicators (deconstruct ability score, recovery score, and environmental score), while the Smart Waste Portugal Association (2021) [

46] segments the MP by building lifecycle stages (design, use, and end-of-life), with a high volume of data.

The analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of these models highlights relevant criteria for selecting the model to be studied. Munaro and Tavares (2021) [

1] provide easy access to the MP structure and the possibility of using free software, although they require additional technological development. Honic et al. (2019a) [

16] and Atta et al. (2021) [

18] present few parameters to be analyzed and a defined technological infrastructure, but they limit the MP to the calculation of mathematical indicators, and some software is not financially accessible. The model from Smart Waste Portugal Association (2021) [

46] offers pre-defined technology but demands analysis of a high volume of data, and the study would be limited to validating the existing artifact. Considering these aspects, the choice of the model by Munaro and Tavares (2021) [

1] is justified by access to structured information, the possibility of using free software, and the opportunity to technologically develop the MP, turning a limitation into a research opportunity.

Regarding the computational tools available for MP development, the literature indicates different possibilities, varying in terms of financial accessibility and pre-defined MP structure. Tools such as Madaster and BuildingOne provide a pre-established data structure but present limitations regarding licensing costs, being financially inaccessible for some studies. BIM platforms, including Revit and Dynamo, are widely accessible, especially for students, and allow technological structuring of the MP, even if they do not predefine its composition. Analysis of use in the Brazilian context shows that BIM, Revit, and Dynamo tools are more present in national design practice, facilitating the dissemination and application of the MP concept among local designers, compared to foreign tools such as Madaster and BuildingOne, whose use depends on English proficiency.

Based on the combined analysis of MP models and computational tools, it is concluded that developing the MP proposed by Munaro and Tavares (2021) [

1] through BIM, using Revit and Dynamo software, constitutes the most suitable alternative for the present study. This choice combines financial accessibility, technological feasibility, and research opportunity, enabling the structure of the MP and potentially contributing to consolidating the concept in construction practice.

4. Development of the Artifact

This section presents the development of the artifact.

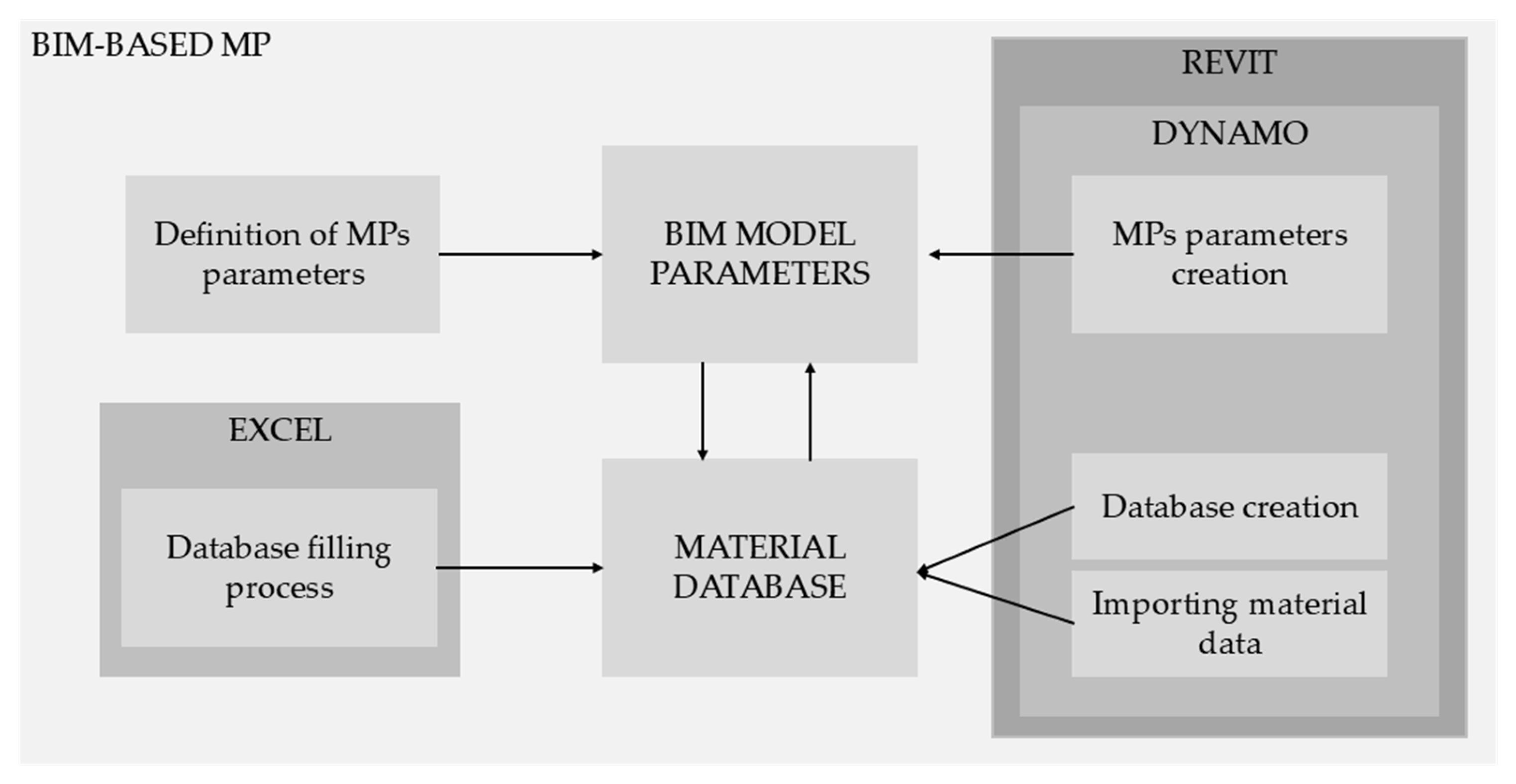

Figure 2 presents the detailed scheme of this development and shows the technological resources used during development.

First, the BIM model parameters are defined and created in the BIM model using Dynamo routines (version 2021). After that, a material database is created using Dynamo routines based on the existing materials in Revit. The database is supported by Excel software (version 2021) and is filled with material data manually. The filled material database is imported to the BIM model. The data are stored within the material parameters in the BIM model and can be used, shared and transmitted by the stakeholders.

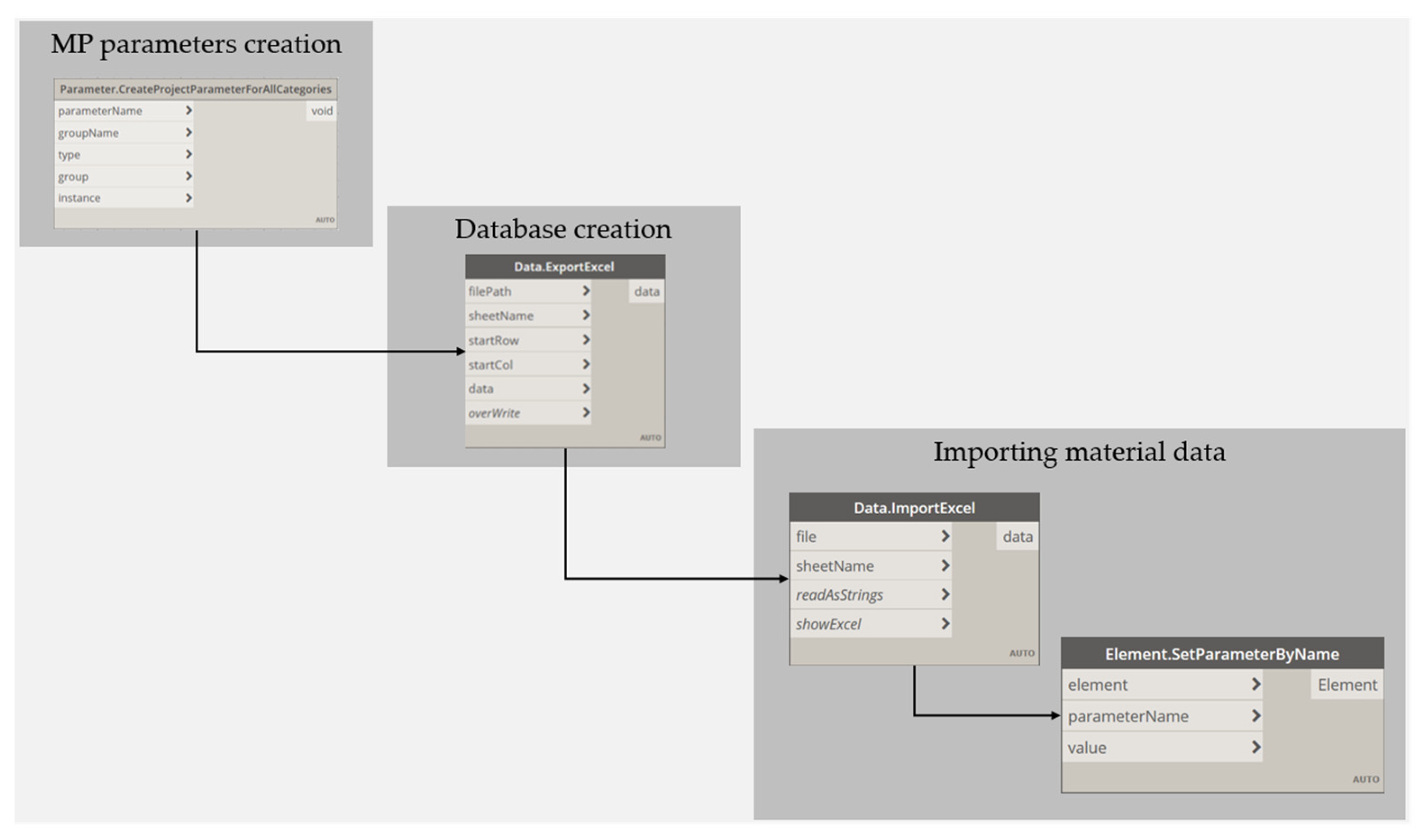

Figure 3 illustrates the Dynamo workflow and the nodes used in visual programming routines. Each node requires specific input data. The final step, “Importing material data,” is a routine composed of two nodes: the first imports the Excel database into the model, and the second selects the data corresponding to a specific material parameter. The next sections will detail the steps of artifact development.

4.1. Definition of Material Passports Parameters

The Information and Sustainability in the Built Environment research group at Federal University of Paraná in Brazil has been studying circularity applied to the built environment since 2018 and is currently part of the international research network ECoEICO (Circular Economy as a Strategy for a More Sustainable Construction Industry), under the CYTED program (Ibero-American Program of Science and Technology for Development) of the European Union.

Research on MPs began with Munaro et al. (2019) [

25], who proposed an MP and its conceptual application to the wood frame panel used by the company Tecverde. The group’s second publication, by Munaro and Tavares (2021) [

1], presents a systematic literature review on MPs and introduces the conceptual MP. Alves (2023) [

47] developed an artifact through the modeling and visual programming of the conceptual MP proposed by Munaro and Tavares (2021) [

1], using Revit and the Dynamo tool.

The conceptual MP proposed by Munaro and Tavares (2021) [

1] assigns nine information categories to an MP, which can track the material’s value throughout its life cycle. In the modeling and visual programming of this MP, as proposed by Alves (2023) [

47], the Revit software and Dynamo tool (version 2021) were used, with support from Excel.

The data and information that make up the MP were inserted into the model through Revit Parameters. Revit Parameters store and communicate data and information about the elements of a model. The software has two types of parameters: (1) Project Parameters and (2) Shared Parameters. The first type refers to parameters that cannot be shared across other projects and cannot be used in software identifiers. On the other hand, Shared Parameters can be used across multiple families and projects, as they are stored in an external file independent of any other file. These parameters can be used in identifiers and can generate schedules that display multiple family categories or multi-category tables [

48].

Revit also classifies its parameters according to Type and Instance. Type parameters are assigned to the Type element of the project, while Instance parameters are assigned to the component, subcomponent, or material [

48].

For the development of the MP model in this study, Project Parameters and Instance Parameters were chosen. Parameters were chosen because Dynamo automates their creation. This automation delegates the operational work to the developed routine, ensuring that parameter generation for each project is not labor-intensive.

Regarding Instance Parameters, this research aims to enable material data groupings that can compose an MP for a type element, a category, a family, or an entire building.

The MP consists of 49 parameters divided across nine information categories. Each category was designed to address specific aspects relevant to different stakeholders throughout the material life cycle. The parameters were derived from existing references in the literature, such as EPDs and the BAMB online platform, and grouped according to CE concept. The model integrates information on general material data, safety, environmental performance, production and logistics, use and maintenance, disassembly, circular strategies (reuse, recycling, remanufacturing), material history, and supporting documentation [

1].

Among the proposed parameters are LCA environmental impact data and EPD. This implies that performance related to impacts is understood as a result of the adopted actions, rather than as an independent measurement objective. MPs can also integrate existing documents [

7]. This structure ensures alignment between the MP and CE goals by promoting transparency, traceability, and material recovery potential across all life-cycle stages [

1].

Table 1 presents the parameters that make up the MP, categorized accordingly.

4.2. Material Passports Parameters Creation

The parameters were created using Dynamo. The tool automated an otherwise extensive and manual task of parameter creation. A visual programming script was developed: a routine for creating both Project Parameters and Instance Parameters.

The scripts created, also referred to as routines, are sequences of tasks defined as nodes. To develop the routine for Project and Instance Parameters, the node “Parameter.CreateProjectParameterForAllCategories” was used.

There are five input data fields: the parameter name; the group name; the data type; the parameter group; and whether the parameter is an Instance or not. The first refers to the name of the parameter to be created; the second refers to the classification assigned to the parameter by the designer (e.g., general data, sustainability, health and safety, among others); the third refers to the data format of the parameter (text, number, image, etc.); the fourth refers to the classification within the material properties in Revit; and the fifth indicates whether the parameter applies to a type element or to an instance material.

4.3. Database Creation

At this stage of the research, the Dynamo tool exports a database of the materials existing in the Revit model using the node “Data.ExportExcel”. The input parameters are file path, sheet name, starting row, starting column, data to be exported, and whether the routine should overwrite the data each time it is executed.

This node requires that a spreadsheet in .xlsx format be created and saved in a directory, and that the worksheet tab be defined. Therefore, the first step in this stage is to create the .xlsx file. The input parameter “data to be exported” was defined as the material name and material description. These two pieces of information will serve as references to identify the material in the proposed MP.

Based on the exported material list, and with the aid of Excel as supporting software, the database is manually entered with data according to their formats as explained in

Table 1 (e.g., EPD is data in URL format).

4.4. Importing Material Data into the Model

The import of material data into the Revit model is carried out through automation using Dynamo. The routine was developed based on two nodes: the first node retrieves data from the database created (and described in the previous subsection); the second imports this data into the selected parameters. The nodes are called, respectively, “Data.ImportExcel” and “Element.SetParameterByName”. After executing this routine, the parameters are populated within the Revit model.

4.5. Material Passports Parameters Tables

Up to this point, the presentation of the artifact has described the stages of creation and processing of the MP parameters. This subsection presents the format in which the parameters are displayed within Revit software and, consequently, defines a proposed layout for the MP presentation.

This study aims to work with technological resources through BIM tools. For this reason, the manipulation of parameters will be carried out using the resources available in Revit software. The tool provides features for generating schedules based on the existing model parameters.

The material takeoff table available in Revit was used for this purpose. This feature generates a list of materials associated with a specific Revit category. Within this table, it is possible to select which parameters to display, analyze, or highlight in the project. Additionally, this type of table supports calculated parameters, allowing the generation of total numerical values based on the total mass or volume of the selected materials.

4.6. Artifact Validation

The validation was carried out in two stages. The first was defined as a black box functional test, which verifies the desired parameters from the user’s perspective without requiring them to understand the system’s internal structure. The goal is to test the functionality and usefulness of the artifact [

49]. For this test, the author interviewed four professionals with different profiles on the market.

The second validation was defined as a dynamic analytical evaluation, which studies the artifact during its use to assess qualities such as performance [

40]. For this validation, data from wood frame materials were used and is shown in

Section 5.

The interview results show that the interviewees consider technology and BIM to be essential for implementing the MP and for supporting the transition from a linear to a circular model. These elements are seen as enablers that can accelerate the transformation process within the construction sector.

However, at present, the practical adoption of this tool remains unfeasible, particularly in large-scale projects. The designers interviewed recognize the conceptual relevance of the MP but do not yet see its full applicability, identifying several stages that must be overcome before direct implementation can occur.

The main obstacle lies in data collection. First, the artifact proposes a manual process for gathering information; moreover, such data are not yet widely available in the market. Preliminary questions must be addressed before the technological tool can be effectively applied, such as: “At what stage of the design process should the MP be used?”; “How can the MP be integrated with other sustainability tools, such as those for energy efficiency?”; and “Will MP technology simplify or increase bureaucratic processes in professional practice?”

The issues surrounding the use of the MP in professional practice go beyond the tool itself. According to the interviewees, the challenge lies in the broader concept and the systemic nature of the construction industry. More sustainable practices, including those related to circularity, are already on the professional agenda. Yet, the real challenge is how to implement them effectively within the current Brazilian context, where systemic issues demand the collaboration of multiple stakeholders to be properly addressed.

5. MP Implementation in Tecverde’s 1.0 House

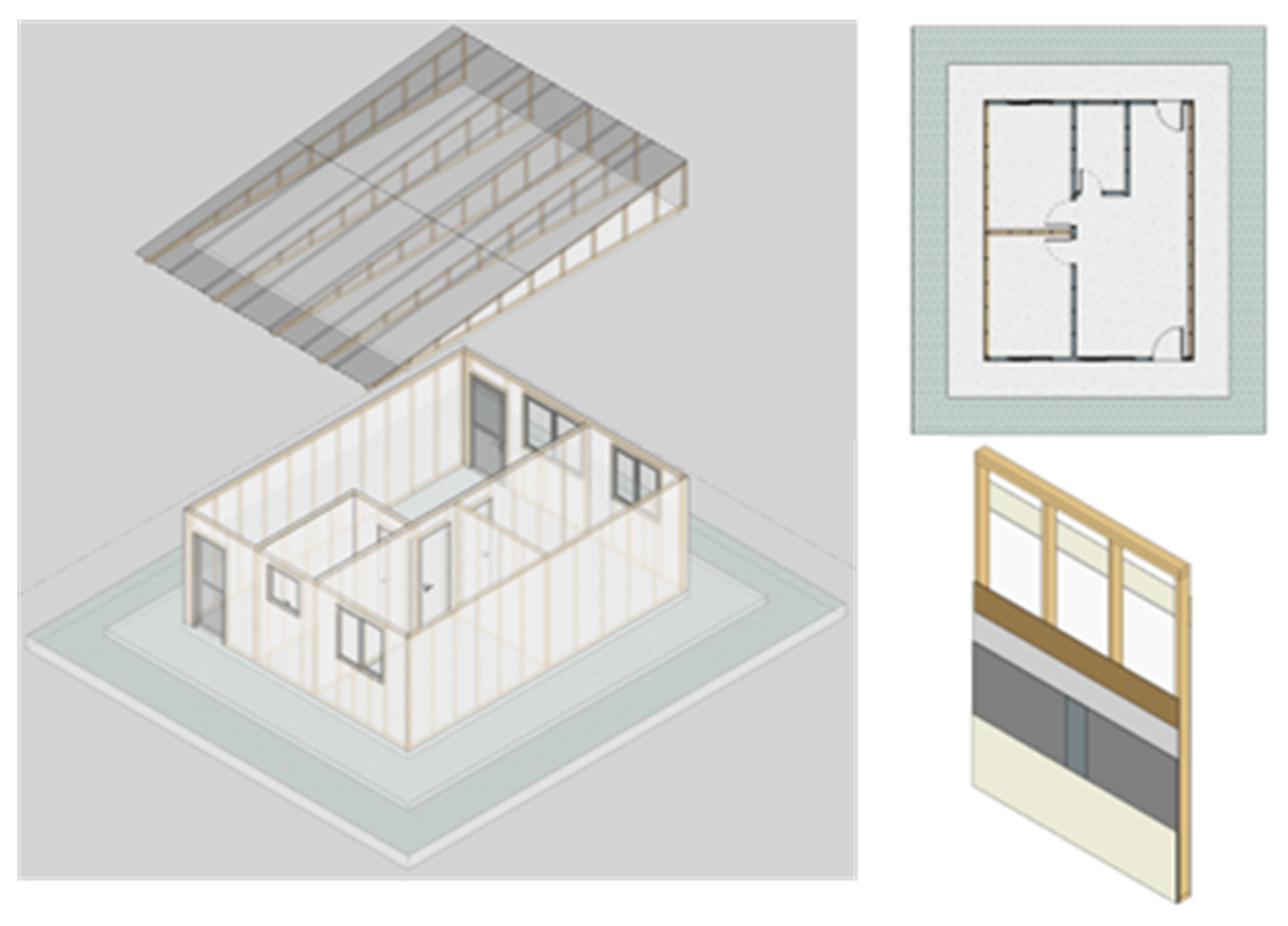

The 1.0 House building, part of the project catalog of the Brazil-based company Tecverde, and the external wall panel for single-story and two-story houses were modeled using the 2024 version of the Revit software.

Figure 4 shows the 3D model.

Since the MP generation routine [

47] was created in the 2021 version of Revit and Dynamo, and because Autodesk does not support newer model files in older software versions, it was necessary to export the building model to an .IFC file. Thus, the .IFC model was imported into the 2021 version of Revit for the development of the MP using visual programming with Dynamo. The Dynamo visual programming routines perform the parametric modeling of the materials in the model.

Next, the second Dynamo routine is executed, and a database supported by Excel is created with the materials from the model. This database is manually populated with information about the materials used in the wood frame system adopted by Tecverde. The data and information were obtained from open access sources made available by the company itself, such as DATec Nº 020-E.

The third and final stage of the MP modeling and visual programming process involves inserting the database into the model, populating the parameters created in the first routine. The Dynamo routine that executes this step encounters errors with the .IFC file, as it assigns data to the parameters of Revit elements. However, when exporting the model to an .IFC file, the materials are not exported as Revit elements but rather as properties of those elements. As a result, the data were inserted into the model with errors and had to be manually adjusted.

The available information entered the MP falls under the categories General Data, Design and Production, and Other. The Other category was filled with the link to DATec Nº 020-E, since the MP parameter structure does not explicitly account for this document. The remaining six categories had no parameters filled in for any of the materials.

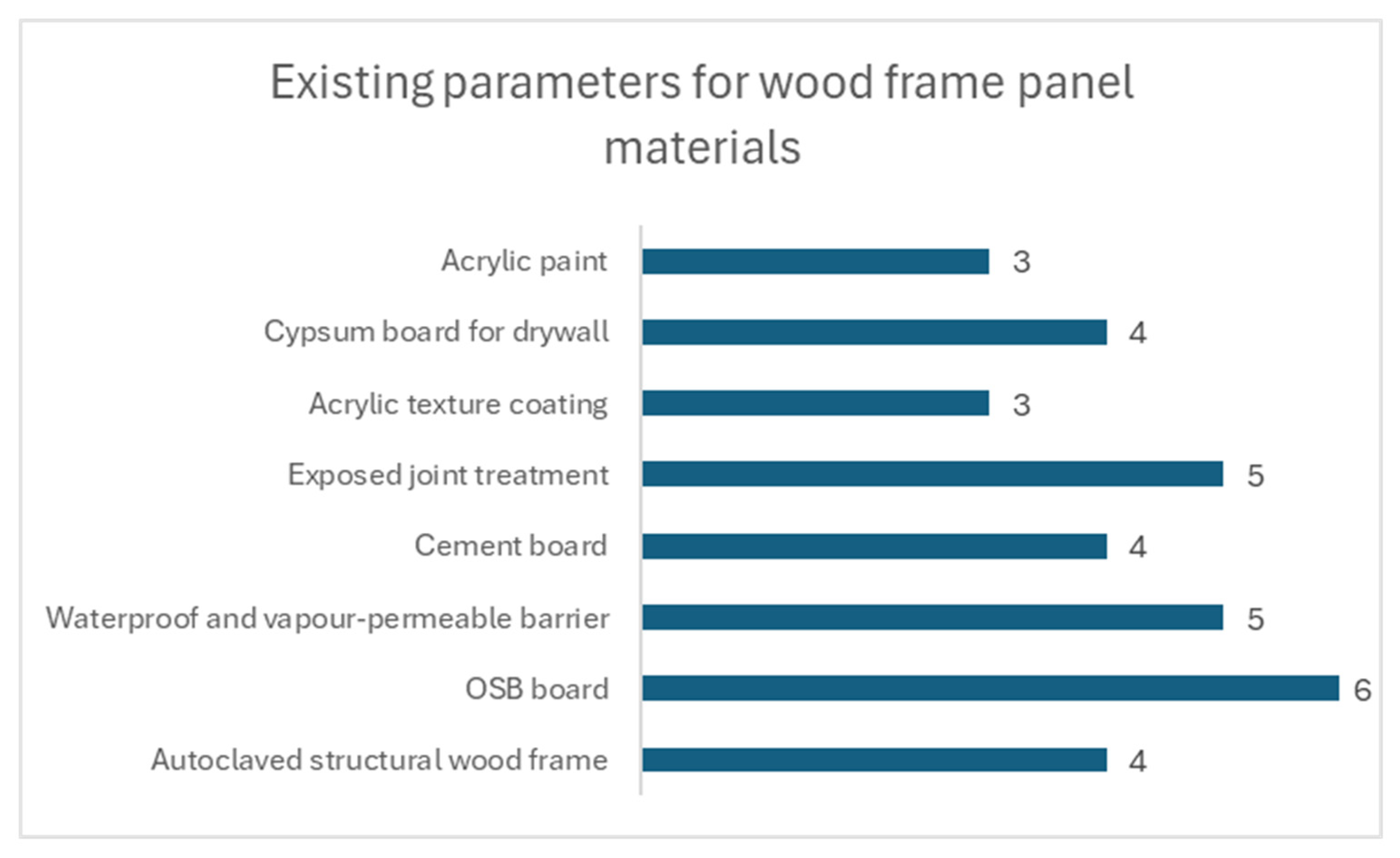

Figure 5 shows the materials that make up the panel and the number of parameters available in the company’s data sources. The OSB board contains 6 out of the 49 parameters, making it the material with the most information, while the acrylic paint and acrylic texture coating each have 3 parameters, making them the materials with the least information.

The parameters that could be filled refer mostly to the MP General Data category and partly to the Design and Production, Use and Operate Phase, and Other categories, which means that five of the nine categories contained no data in the DATec documentation. The lack of information directly affects the purpose of an MP, since it is not possible to track materials for recovery and reuse with such limited data.

Although there is limited information about the materials that make up the wood frame panel, the document provided by the company contains additional information about the complete panel, which makes MP more feasible.

Table 2 summarizes which categories have information available in DATec.

6. Discussion

MPs are digital documents focused on recovering materials and supporting circularity. This means that the MP is not supposed to measure impact-related performance itself [

7]. However, the information on impact-related performance must be on it. The proposed BIM-based MP can document and store data and information about materials in a BIM model. That information can be used and shared sent by the stakeholders to make decisions on recovering materials and maximizing circularity.

Operationally, the artifact proved satisfactory. Dynamo enabled the input of all MP parameters and their application via Revit’s table tools. However, discrepancies between Revit versions and issues with .IFC export compromised the preservation of custom material parameters, requiring manual corrections. These interoperability issues, though unexpected, were resolved and did not prevent successful application. The limitations and improvements in this phase in detailed in Section Limitations and Future Research.

Although the artifact worked, it still is a proof of concept that demonstrated the feasibility of the system. The import of material data into the Revit model was carried out manually at certain stages of development. This occurred because the material data are not stored in a single location and do not have consistent formats among themselves or with the Revit software. The automation of the EPD documents within Dynamo routines is an example of interoperability challenges. The EPD would serve as an official material database available in .html format. However, programming the reading of .html files and subsequently populating the parameters with this data became a limitation. In addition, the EPD would cover only seven of the 49 parameters of the MP.

The wood frame data available were not sufficient to use all the MP potential. There was no information on Sustainability, Disassembly Guide, Reuse and Recyclability Potential, or History. In previous studies on Tecverde’s wood frame panel, Munaro et al. (2019) [

25] pointed out that, in Brazil, suppliers are not required to develop EPDs and, consequently, LCA studies and environmental impact analyses. In the present study, this situation remains, and the consequence is the lack of data for the Sustainability category of the proposed MP.

The circular data on Reuse and Recyclability Potential isn’t available. The Disassembly Guide data also suggest circular principles; however, the presented panel was not designed for disassembly and, consequently, no data or information on this aspect exists. Finally, it would not be possible to have History data for the panel, since this is not a document of an installed panel. History data could be fed into the MP over the course of the use of the materials and/or the panel in a building.

The data and information available in DATec for the panels do not describe the material characteristics necessary for their recovery and reuse, which is the purpose of an MP. Countries with large geographic and economic dimensions, such as Brazil, India, and Russia, still play a limited role in this field [

1]. Neither the DATec documents nor the Brazilian technical standards include sustainability-related data for materials. The ABNT NBR 16936:2023 [

50] is a standard for light wood frame in Brazil and it is even more generic DATec in sustainable or circular data than the DATec Nº 020-E. Information on circular strategies, such as reuse or recyclability, remains far from reality. In the literature [

51], the only material passport case study from Latin America found was by Munaro et al. (2019) [

25]. This highlights the importance of developing strategies and public policies that foster the transition toward a more circular construction sector [

1].

The most important finding in this research is the gap in Brazilian wood frame panels documents regarding their ability to promote more sustainable and circular buildings, and, consequently, the challenge in promote relevant information on materials to recover and reuse them. The DATec Nº 020-E document provides most information required in the MP defined by Munaro and Tavares, but sustainable and circular data. Wood frame construction method has greater potential than traditional construction methods to generate and promote these types of data, as it is based on a modular and industrialized construction system.

Limitations and Future Research

The MP is established as a strategic tool for the transition from the LE to the CE, by documenting material characteristics aimed at their recovery and reuse. However, its adoption in the construction industry faces operational and informational barriers.

The application of the MP to Tecverde’s wood frame panel revealed significant limitations. The first concerns software interoperability: discrepancies in Revit versions and issues with .IFC export compromised the preservation of custom material parameters. The MP data and information organized into the proposed artifact should be able to be exchanged through .IFC format. This impacted directly on the execution of routines in Dynamo, requiring manual corrections.

.IFC was created by BuildingSMART as an open standard for transferring building data among different BIM tools. It also assures compatibility and vendor neutrality, allowing project teams to use their preferred software while ensuring data usability. Moreover, Madaster platform allows uploading the BIM model in IFC format, in order to produce MPs [

52]. It shows the relevance in understanding .IFC format and how to use this structure to transfer MP data.

Another limitation relates to the manual completion of the database during modeling. The process is time-consuming and sensitive to the nominal consistency of materials in Revit, demanding strict standardization. Moreover, any model modification requires the complete repetition of the process due to the absence of automatic synchronization between the modeling and visual programming environments.

These challenges highlight that the potential of the MP is still underutilized. Despite its strategic relevance, the lack of reliable data and interoperability limitations hinder its systemic incorporation in the construction sector. Nevertheless, opportunities also exist for new business models based on circular principles.

To improve the artifact, more DSR cycles are required with an interdisciplinary team with architects, civil engineers, and IT professionals. Such a team would be capable of automatically integrating EPD data in .html format into the BIM model using traditional programming languages rather than relying solely on visual programming tools. They could also make the material data database more structured and automated, thereby reducing the amount of manual work required. These improvements would enhance the scalability of the MP, making the process faster and more seamlessly integrated into the design workflow within the construction industry.

Future research could focus on automating MP data entry, developing interoperable routines, and linking with national databases. In addition, in-depth studies on .IFC export could help minimize information loss and enable neutral and standardized workflows. Data-driven design is another possibility for future research, once design decisions are informed and guided by the systematic analysis and interpretation of data. It enables designers to make proactive, evidence-based decisions that enhance sustainability, promote circularity, and improve the overall lifecycle performance of buildings by systematically leveraging the comprehensive data provided by MP.

Aligned with the integration of optimization and data-driven design strategies within BIM environments, the study by Liao et al. (2026) [

53] demonstrates a BIM-supported multi-objective optimization workflow. This approach provides a valuable methodological reference for enhancing Revit–Dynamo workflows aimed at optimizing sustainability, material reuse, and constructability within materials passport frameworks. Complementarily, the work of Zhang, Li, and Wang (2025) [

54] illustrates how integrating physics-aware learning with data-driven modelling can improve both interpretability and predictive performance. Together, these studies highlight the potential of combining optimization-based and data-driven methodologies to advance intelligent, BIM-integrated material lifecycle management systems, thereby framing the materials passport workflow within a broader, performance-oriented optimisation perspective.

7. Conclusions

The MP is defined as a digital tool aimed at recovering and reusing materials and components throughout their life cycle [

7,

9]. By organizing relevant information on materials, products, and systems, the MP makes this data accessible to various stakeholders involved in the construction supply chain.

In this study, the MP was modeled and visually programmed using Revit and Dynamo, focusing on the external wood frame wall panel used by the Brazilian company Tecverde in single-story houses. The panel consists of eight materials, as specified in DATec Nº 020-E, and the MP included 49 parameters distributed across nine information categories for each material. Despite the interoperability problems during the process, the modeling met the proposed requirements, demonstrating the technical feasibility of the application.

Although Tecverde’s open access databases, such as DATec Nº 020-E, provide information at the panel level, they offer limited documentation on the individual characteristics of the materials. This data gap represents a significant obstacle to fully leveraging the MP, particularly in terms of traceability, sustainability, and reintegration of materials into the production chain.

The application of the MP in wood frame panels highlights the challenges faced by the construction industry in transitioning from a LE to a CE. Data on material sustainability and end-of-life are essential for this shift. While barriers to MP implementation persist, the scenario also reveals opportunities for new business models that embrace circular principles and rethink production chains and workflows. The MP stands out as a tool capable of adding value to materials and documenting information throughout their entire life cycle.