Adopting Large Language Models in the Construction Industry: Drivers, Barriers, and Strategic Implications from China

Abstract

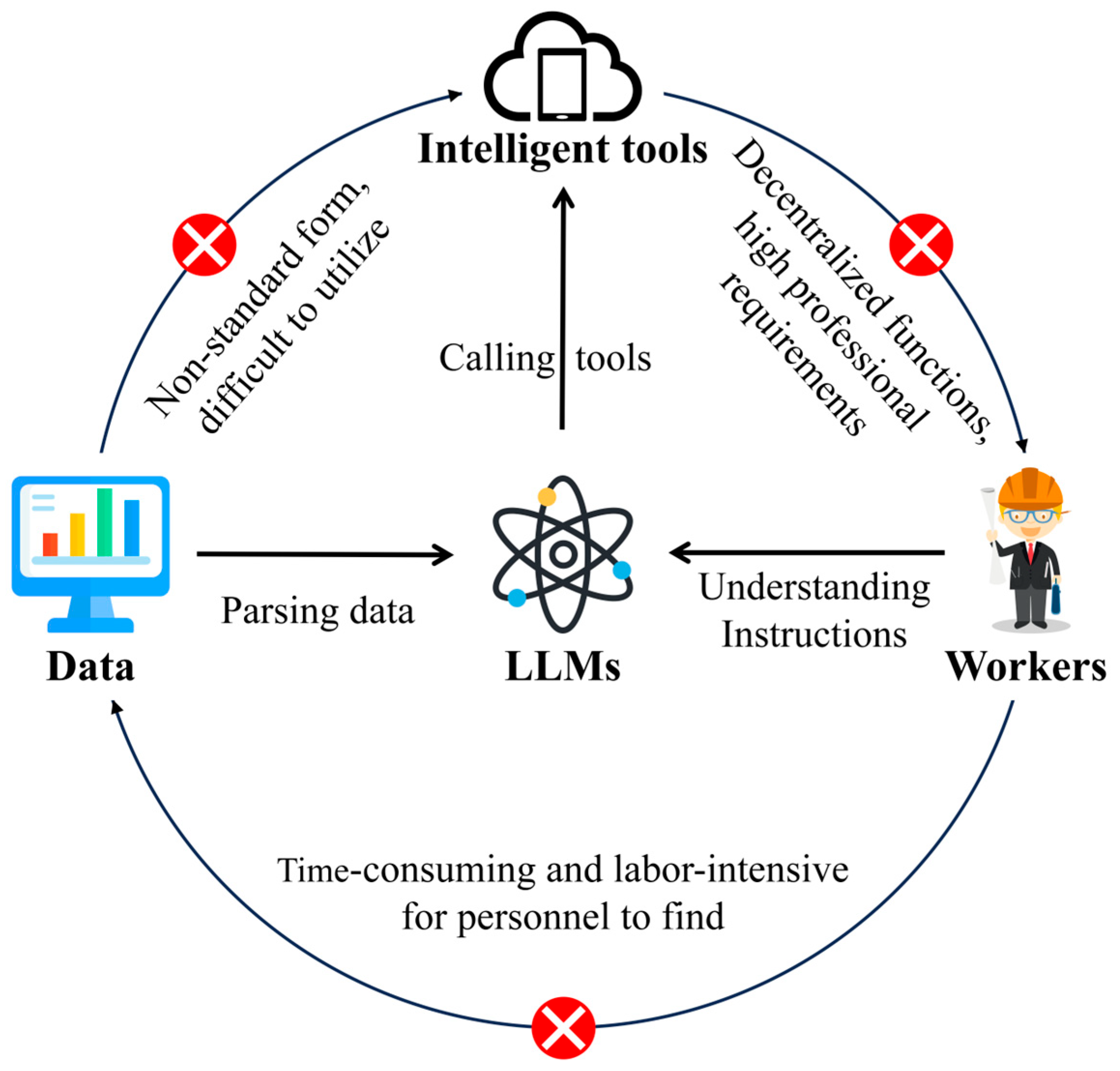

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. LLMs

2.2. LLMs in the Construction Industry

2.3. Drivers and Barriers to the Application of LLMs in the Construction Industry

3. Methodology

3.1. Identification of Influencing Factors

3.2. Questionnaire Design

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

3.4.1. Descriptive Statistics Analysis

3.4.2. Validation Strategy for Questionnaire Data

- (1)

- Reliability and validity analysis

- (2)

- CFA method for evaluating the reasonability of questionnaire design

3.4.3. Weight Analysis for Determining the Importance of Influencing Factors

4. Results

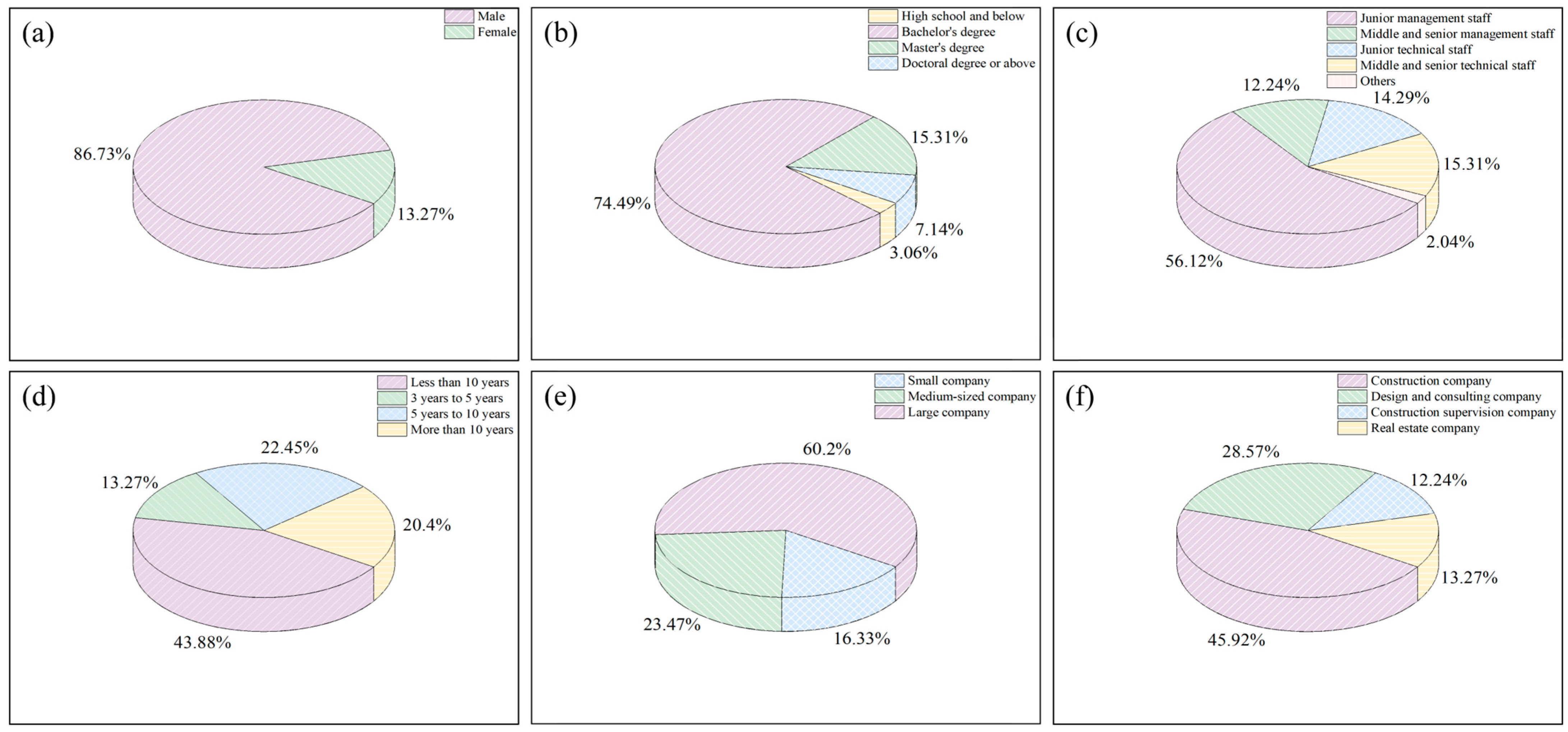

4.1. Descriptive Statistics Analysis

4.1.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

4.1.2. Respondents’ Willingness to Adopt LLMs

4.2. Validation Strategy for Questionnaire Data

4.2.1. Reliability and Validity Analysis

4.2.2. CFA Results for Evaluating the Reasonability of Questionnaire Design

4.3. Weight Analysis for Determining the Importance of Influencing Factors

5. Discussion

5.1. Drivers to the Application

5.2. Barriers to the Application

5.3. Implications for Corporate Transformation and Policy-Making

5.4. Broader Implications for LLM Adoption Across Industries

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ofori, G. Nature of the construction industry, its needs and its development: A review of four decades of research. J. Constr. Dev. Ctries. 2015, 20, 115. [Google Scholar]

- Chuai, X.; Lu, Q.; Huang, X.; Gao, R.; Zhao, R. China’s construction industry-linked economy-resources-environment flow in international trade. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Z.; Solopova, N.A. Sustainable Development of Construction Industry in China. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Urban Engineering and Management Science (ICUEMS2024), Tianjin, China, 2–4 August 2024; p. 03018. [Google Scholar]

- Leviäkangas, P.; Paik, S.M.; Moon, S. Keeping up with the pace of digitization: The case of the Australian construction industry. Technol. Soc. 2017, 50, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- João Ribeirinho, M.; Mischke, J.; Strube, G.; Sjödin, E.; Luis, J. The Next Normal in Construction; McKinsey & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Saka, A.; Taiwo, R.; Saka, N.; Salami, B.A.; Ajayi, S.; Akande, K.; Kazemi, H. GPT models in construction industry: Opportunities, limitations, and a use case validation. Dev. Built Environ. 2024, 17, 100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Hwang, B.-G.; Ngo, J.; Tan, J.P.S. Applications of smart technologies in construction project management. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148, 04022010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, L.; Teng, B. Research on synergistic development paths of intelligent construction and construction industrialization—A case study of Shenyang, China. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 102, 112077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karan, E.P.; Irizarry, J.; Haymaker, J. BIM and GIS integration and interoperability based on semantic web technology. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2016, 30, 04015043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, A.E.; Aliu, J.; Fadamiro, P.O.; Akanni, P.O.; Stephen, S.S. Attaining digital transformation in construction: An appraisal of the awareness and usage of automation techniques. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 67, 105968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, J.; Lu, W.; Xue, F. A review of BIM data exchange method in BIM collaboration. In Proceedings of the 25th International Symposium on Advancement of Construction Management and Real Estate, Wuhan, China, 28–30 November 2020; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 1329–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Issa, R.R.; Anumba, C.J. Query answering system for building information modeling using BERT NN Algorithm and NLG. In Proceedings of the ASCE International Conference on Computing in Civil Engineering 2021, Orlando, FL, USA, 12–14 September 2021; pp. 425–432. [Google Scholar]

- Alreshidi, E.; Mourshed, M.; Rezgui, Y. Factors for effective BIM governance. J. Build. Eng. 2017, 10, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Heacock, L.; Elias, J.; Hentel, K.D.; Reig, B.; Shih, G.; Moy, L. ChatGPT and other large language models are double-edged swords. Radiology 2023, 307, e230163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinosho, T.D.; Oyedele, L.O.; Bilal, M.; Ajayi, A.O.; Delgado, M.D.; Akinade, O.O.; Ahmed, A.A. Deep learning in the construction industry: A review of present status and future innovations. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forth, K.; Borrmann, A. Semantic enrichment for BIM-based building energy performance simulations using semantic textual similarity and fine-tuning multilingual LLM. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 95, 110312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiaan, M.A.K.; Mukta, M.S.H.; Fatema, K.; Fahad, N.M.; Sakib, S.; Mim, M.M.J.; Ahmad, J.; Ali, M.E.; Azam, S. A review on large Language Models: Architectures, applications, taxonomies, open issues and challenges. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 26839–26874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Bhattacharya, M.; Lee, S.-S.; Chakraborty, C. A domain-specific next-generation large language model (LLM) or ChatGPT is required for biomedical engineering and research. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 52, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, T.H.; Cheatham, M.; Medenilla, A.; Sillos, C.; De Leon, L.; Elepaño, C.; Madriaga, M.; Aggabao, R.; Diaz-Candido, G.; Maningo, J. Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: Potential for AI-assisted medical education using large language models. PLoS Digit. Health 2023, 2, e0000198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. ChatGPT utility in healthcare education, research, and practice: Systematic review on the promising perspectives and valid concerns. Healthcare 2023, 11, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korngiebel, D.M.; Mooney, S.D. Considering the possibilities and pitfalls of Generative Pre-trained Transformer 3 (GPT-3) in healthcare delivery. NPJ Digit. Med. 2021, 4, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Lee, R.K.-W.; Bin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shao, J.; Lim, E.-P. Graph-to-tree learning for solving math word problems. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Virtual, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 3928–3937. [Google Scholar]

- Kasneci, E.; Seßler, K.; Küchemann, S.; Bannert, M.; Dementieva, D.; Fischer, F.; Gasser, U.; Groh, G.; Günnemann, S.; Hüllermeier, E. ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2023, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korinek, A. Generative AI for economic research: Use cases and implications for economists. J. Econ. Lit. 2023, 61, 1281–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, A.; Amarneh, M.; Alawneh, H.; Ashqar, H.I.; AlSobeh, A.; Magableh, A.A.A.R. Predictive analytics in mental health leveraging LLM embeddings and machine learning models for social media analysis. Int. J. Web Serv. Res. 2024, 21, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramski, K.; Citraro, S.; Lombardi, L.; Rossetti, G.; Stella, M. Cognitive network science reveals bias in gpt-3, gpt-3.5 turbo, and gpt-4 mirroring math anxiety in high-school students. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2023, 7, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobieszek, A.; Price, T. Playing games with AIs: The limits of GPT-3 and similar large language models. Minds Mach. 2022, 32, 341–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Luo, H.; Fang, W. An integrated approach for automatic safety inspection in construction: Domain knowledge with multimodal large language model. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 65, 103246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Zhao, R.; Xue, F. The Opportunities and Challenges of Multimodal GenAI in the Construction Industry: A Brief Review. Intelligence 2025, 24, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Hadi, M.U.; Al Tashi, Q.; Shah, A.; Qureshi, R.; Muneer, A.; Irfan, M.; Zafar, A.; Shaikh, M.B.; Akhtar, N.; Wu, J. Large language models: A comprehensive survey of its applications, challenges, limitations, and future prospects. Authorea Prepr. 2024, 1, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, K.; Sasaki, M.; Nakamura, A.; Watanabe, N. Measuring the Interpretability and Explainability of Model Decisions of Five Large Language Models; Open Science Framework: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Jin, H.; Tang, R.; Han, X.; Feng, Q.; Jiang, H.; Zhong, S.; Yin, B.; Hu, X. Harnessing the power of llms in practice: A survey on chatgpt and beyond. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 2024, 18, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, P.; Kim, K.; Acharya, M. Opportunities and Challenges of Generative AI in Construction Industry: Focusing on Adoption of Text-Based Models. Buildings 2024, 14, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.; Na, S. Ready for departure: Factors to adopt large language model (LLM)-based artificial intelligence (AI) technology in the architecture, engineering and construction (AEC) industry. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, M.U.; Qureshi, R.; Shah, A.; Irfan, M.; Zafar, A.; Shaikh, M.B.; Akhtar, N.; Wu, J.; Mirjalili, S. A survey on large language models: Applications, challenges, limitations, and practical usage. Authorea Prepr. 2023, 1, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.F.; Della Pietra, V.J.; Desouza, P.V.; Lai, J.C.; Mercer, R.L. Class-based n-gram models of natural language. Comput. Linguist. 1992, 18, 467–480. [Google Scholar]

- Haidar, M.A.; O’Shaughnessy, D. Topic n-gram count language model adaptation for speech recognition. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT), Miami, FL, USA, 2–5 December 2012; pp. 165–169. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J.; Zhou, Z. Research progress of RNN language model. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Applications (ICAICA), Dalian, China, 27–29 June 2020; pp. 1285–1288. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, W.; Chen, Y.; Xue, Q. Survey on research of RNN-based spatio-temporal sequence prediction algorithms. J. Big Data 2021, 3, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I. Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training; OpenAI: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI Blog 2019, 1, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Moushi, O.M. Gpt-4o: The cutting-edge advancement in multimodal llm. Authorea Prepr. 2024, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurokawa, R.; Ohizumi, Y.; Kanzawa, J.; Kurokawa, M.; Sonoda, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Kiguchi, T.; Gonoi, W.; Abe, O. Diagnostic performances of Claude 3 Opus and Claude 3.5 Sonnet from patient history and key images in Radiology’s “Diagnosis Please” cases. JPN J. Radiol. 2024, 42, 1399–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Team, G.; Georgiev, P.; Lei, V.I.; Burnell, R.; Bai, L.; Gulati, A.; Tanzer, G.; Vincent, D.; Pan, Z.; Wang, S. Gemini 1.5: Unlocking multimodal understanding across millions of tokens of context. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.05530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaseelan, N. LLaMA 2: The New Open Source Language Model. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2023, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Makridis, G.; Oikonomou, A.; Koukos, V. Fairylandai: Personalized fairy tales utilizing chatgpt and dalle-3. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.09467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Koo, M.; Blum, L.; Black, A.; Kao, L.; Scalzo, F.; Kurtz, I. A comparative study of open-source large language models, gpt-4 and claude 2: Multiple-choice test taking in nephrology. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.04709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anil, R.; Dai, A.M.; Firat, O.; Johnson, M.; Lepikhin, D.; Passos, A.; Shakeri, S.; Taropa, E.; Bailey, P.; Chen, Z. Palm 2 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.10403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daras, G.; Dimakis, A.G. Discovering the hidden vocabulary of dalle-2. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.00169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas, R.; Babaeizadeh, M.; Kindermans, P.-J.; Moraldo, H.; Zhang, H.; Saffar, M.T.; Castro, S.; Kunze, J.; Erhan, D. Phenaki: Variable length video generation from open domain textual descriptions. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Virtual, 25–29 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.; Kardas, M.; Cucurull, G.; Scialom, T.; Hartshorn, A.; Saravia, E.; Poulton, A.; Kerkez, V.; Stojnic, R. Galactica: A large language model for science. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.09085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsos, Z.; Marinier, R.; Vincent, D.; Kharitonov, E.; Pietquin, O.; Sharifi, M.; Roblek, D.; Teboul, O.; Grangier, D.; Tagliasacchi, M. Audiolm: A language modeling approach to audio generation. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2023, 31, 2523–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Tworek, J.; Jun, H.; Yuan, Q.; Pinto, H.P.D.O.; Kaplan, J.; Edwards, H.; Burda, Y.; Joseph, N.; Brockman, G. Evaluating large language models trained on code. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.03374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.D.M.; Basha, M.S.M.; Hari, M.M.C.; Penchalaiah, M.N. Dall-e: Creating images from text. UGC Care Group I J. 2021, 8, 71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Fawzi, A.; Balog, M.; Huang, A.; Hubert, T.; Romera-Paredes, B.; Barekatain, M.; Novikov, A.; Ruiz, F.J.; Schrittwieser, J.; Swirszcz, G. Discovering faster matrix multiplication algorithms with reinforcement learning. Nature 2022, 610, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onatayo, D.; Onososen, A.; Oyediran, A.O.; Oyediran, H.; Arowoiya, V.; Onatayo, E. Generative AI Applications in Architecture, Engineering, and Construction: Trends, Implications for Practice, Education & Imperatives for Upskilling—A Review. Architecture 2024, 4, 877–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abioye, S.O.; Oyedele, L.O.; Akanbi, L.; Ajayi, A.; Delgado, J.M.D.; Bilal, M.; Akinade, O.O.; Ahmed, A. Artificial intelligence in the construction industry: A review of present status, opportunities and future challenges. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 103299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momade, M.H.; Durdyev, S.; Estrella, D.; Ismail, S. Systematic review of application of artificial intelligence tools in architectural, engineering and construction. Front. Eng. Built Environ. 2021, 1, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Lu, X.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Lin, Y. Automated structural design of shear wall residential buildings using generative adversarial networks. Autom. Constr. 2021, 132, 103931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, H.; Ye, Y.; Zhou, T.; Zhu, Q.; Du, J. Robot-enabled construction assembly with automated sequence planning based on ChatGPT: RoboGPT. Buildings 2023, 13, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, S.A.; Mengiste, E.T.; García de Soto, B. Investigating the use of ChatGPT for the scheduling of construction projects. Buildings 2023, 13, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundidza, F.; Kikuchi, M.; Ozono, T. Enhanced Classification of Delay Risk Sources in Road Construction Using Domain-Knowledge-Driven Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Pacific Rim International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Kyoto, Japan, 18–24 November 2024; pp. 308–319. [Google Scholar]

- Uddin, S.J.; Albert, A.; Ovid, A.; Alsharef, A. Leveraging ChatGPT to aid construction hazard recognition and support safety education and training. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smetana, M.; Salles de Salles, L.; Sukharev, I.; Khazanovich, L. Highway Construction Safety Analysis Using Large Language Models. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Lee, N.; Frieske, R.; Yu, T.; Su, D.; Xu, Y.; Ishii, E.; Bang, Y.J.; Madotto, A.; Fung, P. Survey of hallucination in natural language generation. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzad, H.M.F.; Ibrahim, R.B.; Yusof, A.F.; Khaidzir, K.A.M.; Iqbal, M.; Razzaq, S. The role of interoperability dimensions in building information modelling. Comput. Ind. 2021, 129, 103444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.; Feng, L. Integration of industry 4.0 related technologies in construction industry: A framework of cyber-physical system. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 122908–122922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korinek, A. LLMs Level Up—Better, Faster, Cheaper: June 2024 Update to Section 3 of “Generative AI for Economic Research: Use Cases and Implications for Economists. J. Econ. Lit. 2024, 61, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Co, C.Y. Chinese contractors in developing countries. Rev. World Econ. 2014, 150, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel Rahimi, A.; Pienaar, O.; Ghadimi, M.; Canfell, O.J.; Pole, J.D.; Shrapnel, S.; van der Vegt, A.H.; Sullivan, C. Implementing AI in Hospitals to Achieve a Learning Health System: Systematic Review of Current Enablers and Barriers. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e49655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, A.A.; Murray, J.; Greiner, R.; Cohen, J.P.; Shojania, K.G.; Ghassemi, M.; Straus, S.E.; Pou-Prom, C.; Mamdani, M. Implementing machine learning in medicine. Cmaj 2021, 193, E1351–E1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.; Saeed, H.; Pringle, C.; Eleftheriou, I.; Bromiley, P.A.; Brass, A. Artificial intelligence projects in healthcare: 10 practical tips for success in a clinical environment. BMJ Health Care Inform. 2021, 28, e100323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, M.A.; Zhou, X.; Nabi, F.; Genrich, R.; Gururajan, R. Would Business Applications such as the FinTech benefit by ChatGPT? If so, where and how? In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Web Intelligence and Intelligent Agent Technology (WI-IAT), Venice, Italy, 26–29 October 2023; pp. 541–546. [Google Scholar]

- Steen, L.E.A.; Vevle, S.R. Generative Artificial Intelligence Use in Financial Institutions Drivers, Barriers & Future Development; University of Agder: Kristiansand, Norway, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kar, S.; Kar, A.K.; Gupta, M.P. Modeling drivers and barriers of artificial intelligence adoption: Insights from a strategic management perspective. Intell. Syst. Account. Financ. Manag. 2021, 28, 217–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakkaraju, K.; Jones, S.E.; Vuruma, S.K.R.; Pallagani, V.; Muppasani, B.C.; Srivastava, B. LLMs for Financial Advisement: A Fairness and Efficacy Study in Personal Decision Making. In Proceedings of the Fourth ACM International Conference on AI in Finance, Brooklyn, NY, USA, 27–29 November 2023; pp. 100–107. [Google Scholar]

- Eche, T.; Schwartz, L.H.; Mokrane, F.-Z.; Dercle, L. Toward generalizability in the deployment of artificial intelligence in radiology: Role of computation stress testing to overcome underspecification. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2021, 3, e210097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwo, R.; Bello, I.T.; Abdulai, S.F.; Yussif, A.-M.; Salami, B.A.; Saka, A.; Zayed, T. Generative AI in the Construction Industry: A State-of-the-art Analysis. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.09939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, Q. Xuanyuan 2.0: A large chinese financial chat model with hundreds of billions parameters. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM international Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Birmingham, UK, 21–25 October 2023; pp. 4435–4439. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Ding, H.; Chen, H. Large language models in finance: A survey. In Proceedings of the Fourth ACM International Conference on AI in Finance, Brooklyn, NY, USA, 27–29 November 2023; pp. 374–382. [Google Scholar]

- Leiner, T.; Bennink, E.; Mol, C.P.; Kuijf, H.J.; Veldhuis, W.B. Bringing AI to the clinic: Blueprint for a vendor-neutral AI deployment infrastructure. Insights Into Imaging 2021, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Shen, Q.; Deng, Y.; Cheng, J. Natural-language-based intelligent retrieval engine for BIM object database. Comput. Ind. 2019, 108, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botao, Z.; Wanlei, H.; Ziwei, H.; ED, L.P.; Junqing, T.; Hanbin, L. A building regulation question answering system: A deep learning methodology. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2020, 46, 101195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saka, A.B.; Oyedele, L.O.; Akanbi, L.A.; Ganiyu, S.A.; Chan, D.W.; Bello, S.A. Conversational artificial intelligence in the AEC industry: A review of present status, challenges and opportunities. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2023, 55, 101869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsi, S.; Zhao, D.; McDonald, J.; Li, B.; Michaleas, A.; Jones, M.; Bergeron, W.; Kepner, J.; Tiwari, D.; Gadepally, V. From words to watts: Benchmarking the energy costs of large language model inference. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE High Performance Extreme Computing Conference (HPEC), Boston, MA, USA, 25–29 September 2023; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J.; Huang, Q.; Chen, X.; Tian, C. Large Language Model Performance Benchmarking on Mobile Platforms: A Thorough Evaluation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.03613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, A.; Gokkaya, B.; Harman, M.; Lyubarskiy, M.; Sengupta, S.; Yoo, S.; Zhang, J.M. Large language models for software engineering: Survey and open problems. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Software Engineering: Future of Software Engineering (ICSE-FoSE), Melbourne, Australia, 14–20 May 2023; pp. 31–53. [Google Scholar]

- Akintoye, A. Analysis of factors influencing project cost estimating practice. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2000, 18, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. Validity and reliability of the research instrument; how to test the validation of a questionnaire/survey in a research. Int. J. Acad. Res. Manag. 2016, 5, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N. Factor analysis as a tool for survey analysis. Am. J. Appl. Math. Stat. 2021, 9, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapanga, A.; Miruka, C.O.; Mavetera, N. Barriers to effective value chain management in developing countries: New insights from the cotton industrial value chain. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2018, 16, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A.; Moore, M.T. Confirmatory Factor Analysis. In Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; Volume 361, p. 379. [Google Scholar]

- Pliego-Martínez, O.; Martínez-Rebollar, A.; Estrada-Esquivel, H.; de la Cruz-Nicolás, E. An Integrated Attribute-Weighting Method Based on PCA and Entropy: Case of Study Marginalized Areas in a City. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Duan, K.; Zuo, J.; Zhao, X.; Tang, D. Integrated sustainability assessment of public rental housing community based on a hybrid method of AHP-entropy weight and cloud model. Sustainability 2017, 9, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.M.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, W.; Fan, J.; Gou, J.; Liu, B.; Gide, E.; Soar, J.; Shen, B.; Fazal-e-Hasan, S. A comparative analysis of the principal component analysis and entropy weight methods to establish the indexing measurement. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutte, J.P. Information Technology Decision Making for the Intelligence Community: A Delphi Study. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Houle, D.; Mezey, J.; Galpern, P. Interpretation of the results of common principal components analyses. Evolution 2002, 56, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munier, N.; Hontoria, E. Uses and Limitations of the AHP Method; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Tian, D.; Yan, F. Effectiveness of entropy weight method in decision-making. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 3564835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güzelci, O.Z.; Şener, S.M. An Entropy-Based Design Evaluation Model for Architectural Competitions through Multiple Factors. Entropy 2019, 21, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozorhon, B.; Oral, K. Drivers of innovation in construction projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2017, 143, 04016118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Brown, A. Innovation in construction firms of different sizes: Drivers and strategies. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2018, 25, 1210–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Wang, G.; Li, H.; Skitmore, M.; Huang, T.; Zhang, W. Practices and effectiveness of building information modelling in construction projects in China. Autom. Constr. 2015, 49, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasnejad, B.; Nepal, M.P.; Ahankoob, A.; Nasirian, A.; Drogemuller, R. Building Information Modelling (BIM) adoption and implementation enablers in AEC firms: A systematic literature review. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2021, 17, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Ma, Z.; Skibniewski, M.J.; Guo, J. Construction automation and robotics: From one-offs to follow-ups based on practices of Chinese construction companies. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 05020013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Chen, L.; Zhan, W. Positioning construction workers’ vocational training of Guangdong in the global political-economic spectrum of skill formation. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 28, 2489–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Chen, Z.; Ye, J.; Zhang, N. Exploring critical success factors for digital transformation in construction industry–based on TOE framework. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024, 32, 4227–4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. Artificial intelligence: A survey on evolution, models, applications and future trends. J. Manag. Anal. 2019, 6, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiss, B.A.; Elsaigh, W.A. Application of novel hybrid deep learning architectures combining Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN): Construction duration estimates prediction considering preconstruction uncertainties. Eng. Res. Express 2024, 6, 032102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, P.G.R.; dos Santos, C.D.; Farias, J.S. Artificial intelligence regulation: A framework for governance. Ethics Inf. Technol. 2021, 23, 505–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Darko, A.; Chan, A.P.; Wang, R.; Zhang, B. An empirical analysis of barriers to building information modelling (BIM) implementation in construction projects: Evidence from the Chinese context. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 22, 3119–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Su, X.; Zhou, Y. Organizational socialization, organizational identification and organizational citizenship behavior: An empirical research of Chinese high-tech manufacturing enterprises. Nankai Bus. Rev. Int. 2010, 1, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinberg, S. Health and Performance in Small Enterprises: Studies of Organizational Determinants and Change Strategy. Ph.D. Thesis, Luleå Tekniska Universitet, Luleå, Sweden, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, T.; Tamaki, M.; Komoda, N. Business process integration as a solution to the implementation of supply chain management systems. Inf. Manag. 2003, 40, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issaoui, Y.; Khiat, A.; Bahnasse, A.; Ouajji, H. Toward smart logistics: Engineering insights and emerging trends. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2021, 28, 3183–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Kim, M. Utilization and challenges of artificial intelligence in the energy sector. Energy Environ. 2024, 0958305X241258795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, K.; Akbar, R. An analytical study of information extraction from unstructured and multidimensional big data. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Developer | Release Year | Access | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-4o | OpenAI | 2024 | API | [44] |

| Claude 3.5 | Anthropic | 2024 | API | [45] |

| Gemini 1.5 Pro | Google DeepMind | 2024 | API | [46] |

| GPT-4 | OpenAI | 2023 | API | [47] |

| LLaMA 2 | Meta | 2023 | Open source | [48] |

| DALLE-3 | OpenAI | 2023 | API | [49] |

| Claude | Anthropic | 2023 | Open source | [50] |

| PaLM 2 | 2023 | Open source | [51] | |

| DALLE-2 | OpenAI | 2022 | API | [52] |

| Phenaki | 2022 | API | [53] | |

| Galactica | Meta | 2022 | API | [54] |

| AudioLM | 2022 | API | [55] | |

| Codex | OpenAI | 2021 | API | [56] |

| DALL-E | OpenAI | 2021 | API | [57] |

| AlphaTensor | DeepMind | 2021 | Open source | [58] |

| Name | Developer | Release Year | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| ConstructionGPT | Shanghai Construction No. 4 (Group) Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) | 2024 | Intelligent Q & A and intelligent search for engineering drawings |

| CivilGPT | Tongji University | 2024 | Professional calculations, standardized queries, design optimization, teaching and research, etc. |

| AecGPT | Glodon | 2024 | Data analysis and prediction, intelligent assisted design, construction simulation and optimization, etc. |

| Zhuo Ling | Vanyitech | 2023 | Intelligent Interaction between LLMs and Engineering Drawings |

| SiKong | SiKong Society | 2023 | Architectural auxiliary design, drawing review guidance, comprehensive scoring, environmental simulation, etc. |

| Primary Factor | Code | Sub-Factor | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drivers | ||||

| Company (Factor D1) | DA1 | Having research and development teams | Some construction companies already have AI research and development teams | [6,73,74] |

| DA2 | Staff training | Employees receive training on LLMs, AI, and other knowledge | [6,73,75,76] | |

| DA3 | Collaborate with advanced technology companies | Collaborate with advanced technology companies such as Baidu and Tencent | [77] | |

| DA4 | Robust performance monitoring and evaluation | The company’s performance monitoring and evaluation system is well-established | [73] | |

| Value creation (Factor D2) | DB1 | Improve work efficiency | Improve efficiency, simplify operations, increase productivity, and automate tasks | [12,77,78,79] |

| DB2 | Provide technical assistance | Assist employees, virtual assistants, train and guide technology to make decisions faster | [77,78,80] | |

| DB3 | Improve product quality | Accurate model results, improved quality, and enhanced competitive advantage | [77,80,81,82] | |

| DB4 | Cost reduction | Based on prediction and reducing human errors, the cost of repetitive work can be reduced | [78] | |

| DB5 | Sustained demand | Sustainable processes that meet business needs | [59,78] | |

| Technology (Factor D3) | DC1 | Algorithm and model optimization | The algorithms and models of LLMs are continuously optimized to make their application in the construction industry more precise and efficient | [12,76,82] |

| DC2 | Software and hardware support | Research and development of software and hardware related to LLMs in the construction industry | [6] | |

| DC3 | Ecological structure | The application of LLMs in the construction industry requires the construction of a complete ecosystem | [17] | |

| Safety and regulations (Factor D4) | DD1 | Network security measures | Network security measures such as fraud detection, anomaly detection, and threat prediction are implemented to ensure the safety of work | [12,77,83] |

| DD2 | Introduce policies | Introduce policies to clarify the compliance of management | [77] | |

| DD3 | Supervision by regulatory authorities | Regulatory authorities oversee the network environment | [76,77] | |

| Service (Factor D5) | DE1 | 24/7 Response | Supports 24/7 access with fast response times | [76,78,81] |

| DE2 | Personalization | Provide personalized services to customers | [12,77,81,84] | |

| Barriers | ||||

| Domain- specific (construction industry) (Factor D1) | BA1 | Requirement for construction-specific knowledge | The knowledge of architecture is complex, and a large amount of professional knowledge cannot be encoded by machines | [81,85] |

| BA2 | Handling unstructured and heterogeneous data | Building data exists in various, unstructured formats, making it difficult to process | [81,86] | |

| BA3 | Lack of large-curated datasets | Most construction companies have not processed their project data into a format that can be used to train LLMs | [12,65,81,87] | |

| BA4 | Bias in existing datasets | Building datasets typically exhibit significant regional biases | [81] | |

| BA5 | Integration with workflows | Not yet integrated with construction management workflows, such as construction cost management, schedule management, quality management, etc. | [6,81] | |

| Technology (Factor D2) | BB1 | Model instability and training difficulties | Model instability and training difficulties | [81] |

| BB2 | Computational resource requirements | The demand for computility, model size, and model quality has increased | [81,88] | |

| BB3 | Assessing output quality | Evaluating quality often relies on subjective manual review by domain experts, and developing and integrating better quality assurance techniques is crucial for building LLMs | [81] | |

| BB4 | Potential for hallucination and factual inconsistencies | The model generates information that is not factual or unfounded | [79,83,88] | |

| BB5 | Lack of explainability | Professionals are unable to understand the intention or principle behind the model results | [76,81,83,87] | |

| BB6 | Adaptation to specific systems | Compatible with specific systems (such as the domestic Kirin system) | [89] | |

| Adoption (Factor D3) | BC1 | Resistance to new technologies | Construction companies rely heavily on established processes and work methods, and managers are unwilling to modify or replace traditional models | [81,87] |

| BC2 | Lack of skills and expertise | Construction companies lack relevant technical talents | [81,87] | |

| BC3 | High upfront investment costs | The initial investment cost for applying LLMs is high | [81,87] | |

| BC4 | Unclear governance frameworks | The introduction of risk management frameworks and technical standards lags behind the rapid development of LLMs | [81] | |

| BC5 | Code controllability requirements | Code controllability requirements, such as requiring source code, may face resistance from developers | [90] | |

| Ethical (Factor D4) | BD1 | Data privacy and security | Privacy information leakage | [87,88] |

| BD2 | Social concerns | Society’s concerns about automated work, such as construction workers being replaced by machines | [81] | |

| BD3 | Potential for misuse | Model abuse, generating content that violates laws, regulations, and ethical principles | [81,83,88] | |

| Study Variables | Cronbach’s Alpha | N of Items |

|---|---|---|

| Drivers | 0.964 | 17 |

| Barriers | 0.957 | 19 |

| Drivers | Barriers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy. | 0.921 | Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy. | 0.898 | ||

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 1687.635 | Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 1722.260 |

| df | 136 | df | 171 | ||

| Sig. | 0.000 | Sig. | 0.000 | ||

| Drivers | AVE | CR | Barriers | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drivers | Barriers | ||||

| Company | 0.687 | 0.897 | Domain-specific | 0.712 | 0.925 |

| Value creation | 0.708 | 0.923 | Technology | 0.572 | 0.889 |

| Technology | 0.805 | 0.924 | Adoption | 0.641 | 0.899 |

| Safety and regulations | 0.771 | 0.91 | Ethical | 0.652 | 0.849 |

| Service | 0.867 | 0.928 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, L.; Zhao, X.; Jiang, R.; Wu, C.; Liao, L.; Yang, Z.; Tan, J. Adopting Large Language Models in the Construction Industry: Drivers, Barriers, and Strategic Implications from China. Buildings 2025, 15, 4296. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234296

Ma L, Zhao X, Jiang R, Wu C, Liao L, Yang Z, Tan J. Adopting Large Language Models in the Construction Industry: Drivers, Barriers, and Strategic Implications from China. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4296. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234296

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Liang, Xinyu Zhao, Rui Jiang, Chengke Wu, Longhui Liao, Zhile Yang, and Jiajuan Tan. 2025. "Adopting Large Language Models in the Construction Industry: Drivers, Barriers, and Strategic Implications from China" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4296. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234296

APA StyleMa, L., Zhao, X., Jiang, R., Wu, C., Liao, L., Yang, Z., & Tan, J. (2025). Adopting Large Language Models in the Construction Industry: Drivers, Barriers, and Strategic Implications from China. Buildings, 15(23), 4296. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234296