2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Yixian County, located in Huangshan City, Anhui Province, encompasses 46 traditional villages (

Figure 3). The region is renowned for its abundance of tangible cultural heritage, including the UNESCO World Heritage Sites of Hongcun and Xidi. Blessed with a scenic natural environment and rich cultural traditions, Yixian is often referred to as the “Great Landscape of Xin’an”. Since ancient times, Yixian County has been nurtured by the celebrated landscape of the Xin’an River, shaped by a distinctive cultural ethos. Influenced by Neo-Confucian philosophy, local traditions emphasized both clan ethics and harmonious neighborhood relations. They valued education, honesty, mutual support, and humility. Classical couplets such as “I love my neighbors and they love me; fish thrive by water and water sustains fish” and “A virtuous neighborhood with benevolence and righteousness, a community shaped by propriety and justice” vividly illustrate the ancestors’ pursuit of a harmonious and humane social environment.

Yixian County currently has 46 nationally designated traditional villages. However, four of the villages are located within urban built-up areas, where the development environment fundamentally differs from that of traditional rural settlements. Given that the spatial characteristics of urban areas may excessively interfere with the relevant indicators, these villages were excluded from the scope of this study. Additionally, the two newly added traditional villages from the sixth batch are still in the preliminary construction and designation phase. Their various indicators remain unstable and lack comparability, leading to their exclusion as well. Based on these considerations, this study ultimately selected 40 relatively mature and representative traditional villages from the first five batches as the sample for analysis. Among these 40 samples, 33 cases meeting the characteristics of “Atypical villages” were further identified based on indicators such as residential vitality, cultural heritage, architectural preservation, and tourism development. These cases will be used for subsequent classification and optimization pathway research.

2.2. Data Sources

This study integrated multiple data sources to ensure the comprehensiveness and reliability of the analysis. The primary datasets include traditional village archival records, geospatial vector data, socioeconomic statistics, online Points of Interest (POI) data, and results from field investigations.

Archival data on traditional villages were acquired through structured interviews and document replication conducted at local township offices. Geospatial data, comprising village centroid coordinates, digital elevation models (DEM), administrative boundaries, and road network data, were sourced from the official portal of the National Natural Resources Bureau of China.

Socioeconomic statistics were obtained from official publications of local government agencies, providing baseline information on the population, economic structure, and village-level development indicators. Additionally, infrastructure and service-related data, including the spatial distribution of commercial facilities, food, lodging, transport, and lifestyle amenities, were extracted from the open API of the Gaode (AutoNavi) mapping platform. This multisource dataset enables comprehensive spatial and functional profiling of the selected villages.

2.3. Research Methods

2.3.1. Construction of Indicator System for Identification of Atypical Traditional Villages

The evaluation indicator system developed for this study was based on national standards such as the Evaluation System for Traditional Villages and the Assessment Indicators for China’s Historic and Cultural Towns and Villages, as well as relevant academic research (

Table 2) [

8,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. Based on these foundations, adjustments and optimizations were made to better align with the specific characteristics of atypical villages in southern Anhui.

First, by systematically reviewing relevant literature and existing indicator systems, the fundamental characteristics of traditional villages in terms of spatial layout, cultural value, and heritage preservation were identified, which guided the selection of evaluation indicators. To ensure the scientific rigor and contextual adaptability of the evaluation system, this study constructed the indicator system from the dual perspectives of human and land. “Human” refers to the active populations in southern Anhui’s traditional villages, including residents and tourists, while “land” refers to the village itself, encompassing the village environment and historic buildings. Based on these two core perspectives, the identification indicator system for atypical traditional villages was developed (as shown in

Figure 4).

Building on the initial framework, expert consultations and multiple rounds of refinement were conducted to continuously improve the indicator system, making it more scientifically robust and targeted. Ultimately, a comprehensive identification indicator system for atypical traditional villages was finalized (see

Table 3).

2.3.2. Database Construction

To conduct spatial analysis and identify village types, this study imported relevant data into a Geographic Information System (GIS) platform, specifically using ArcGIS Pro version 3.4.0. for data processing and analysis. We established a comprehensive geographic database that integrates multiple datasets, including village locations, infrastructure, and environmental data. The natural breakpoint method (Jenks) was used for data classification within the GIS software. This method, proposed by George F. Jenks [

53], is a classic technique widely applied in fields such as territorial spatial planning [

54], economic geography [

55], environmental science, and remote sensing [

56]. Due to its advantages in optimizing classification interpretability and application value, the natural breakpoint method is particularly suitable for traditional village research involving multi-attribute spatial data. By minimizing within-class variance and maximizing between-class variance, the method effectively identifies natural clustering patterns within the data, thereby enhancing the scientific rigor and interpretability of the classification results.

Building upon this foundation, a standardized five-level scoring system (1–5 points) is introduced to ensure consistency and comparability across indicator evaluations while supporting multidimensional structured assessments (see

Table 4). The integration of the natural breakpoint method with the ordinal scoring system enhances data standardization quality, laying the groundwork for cluster analysis and village type classification.

2.3.3. Cluster Analysis

After assigning scores to the various indicators, the data were imported into IBM SPSS Statistics version 27 software for cluster analysis. This study employed the Ward’s minimum variance method to perform hierarchical clustering, using squared Euclidean distance as the measure of dissimilarity to ensure consistency in distance calculations between villages. Ward’s Method is a commonly used clustering technique in hierarchical clustering, which minimizes the sum of squared errors within clusters to select the optimal clusters. To eliminate bias caused by differences in variable scales, all indicator values were standardized using Min–Max normalization (0–1 range). The 0–1 normalization, also known as Min–Max normalization, is a commonly used method for scaling data into a range between 0 and 1. This normalization method maps the minimum value of each variable to 0 and the maximum value to 1, thereby scaling all data points to the specified range. The formula is as follows

is the normalized data value,

is the minimum value of the variable, and

is the maximum value of the variable.

4. Discussion

This study adopts the perspective of human–environment coupling theory to identify and diagnose risks in atypical traditional villages in southern Anhui, breaking away from previous research that predominantly focused on typical traditional villages and emphasized architectural style and cultural value. Unlike existing literature that tends to focus on one aspect of traditional villages, this study places the interactive characteristics of the human–environment relationship at the core of the analysis. It reveals the differences in functionality and structure of atypical traditional villages under the context of rapid urbanization, and constructs a multi-dimensional comprehensive evaluation system that includes indicators such as transportation accessibility, living environment, protection of ancient buildings, and tourism development. This evaluation system not only provides a systematic depiction of village spatial characteristics and risk status, but also offers a more actionable classification framework and intervention path for atypical traditional villages.

Compared to existing research, this study places greater emphasis on the dynamic interaction between human–environment relationships and their impact on village development risks, filling the gap in traditional village research where such interactive effects were previously overlooked. It provides a new perspective for theoretical research. Furthermore, the differentiated development and risk management strategies proposed in this study directly address the practical needs of grassroots governance and policy-making, offering actionable pathways for the sustainable transformation of traditional villages. By analyzing the human–environment interaction, this study introduces a classification method for traditional villages, providing a new classification perspective for their protection and development, and offering theoretical support and guidance for related practices.

4.1. Development Strategy for Type B-1 Atypical Traditional Villages

For B-1 type atypical traditional villages (such as Zhuxi Village and Lanhu Village), their primary characteristics include severe population outflow, insufficient residential vitality, and lagging infrastructure. However, they also possess a high proportion of traditional buildings and well-preserved historical relics, demonstrating potential for cultural reuse and revitalization. Therefore, development strategies should focus on four key areas: the village’s foundational conditions, residents’ livelihoods, historical resources, and tourism development, proposing systematic and actionable countermeasures (see

Figure 10a).

Regarding the village’s foundational landscape, efforts should be grounded in improving the living environment and ecological restoration. First, implement comprehensive village-wide aesthetic improvements by clearing cluttered structures and disorderly spaces to restore the integrity of traditional layouts. Second, address infrastructure deficiencies such as paved roads, water supply and drainage systems, and electrical networks to enhance daily convenience. Third, optimize the use of homestead sites and vacant land to guide the redevelopment of idle resources. Fourth, strengthen ecological restoration of surrounding mountains and water systems to ensure the sustainability of the overall village environment.

Regarding residents’ livelihoods, the focus lies on improving living conditions and enhancing development momentum. First, gradually upgrade outdated housing and basic living facilities to ensure residential safety and comfort. Second, improve public healthcare, education, and elderly care services to elevate residents’ fundamental well-being. Third, use policy incentives to attract young people to return and start businesses, alleviating the hollowing out of the village population. Fourth, leverage the village’s strengths to develop distinctive agriculture, create local employment opportunities, and strengthen residents’ attachment to the village’s development.

Regarding historical resources, strategies should focus on parallel preservation and revitalization. First, establish archives for the village’s ancient buildings and historical relics to create a sustainable preservation database. Second, classify and restore ancient structures based on their value to avoid one-size-fits-all renovations. Third, implement an “adoption system” to attract social participation in cultural heritage protection, reducing the burden of sole government investment. Fourth, explore appropriate revitalization while respecting authenticity, transforming historic buildings into public cultural spaces or homestays to enhance cultural resource utilization.

Regarding tourism development, adhere to the principle of “low-impact development and gradual cultivation”. First, integrate village culture and natural landscapes to explore light tourism projects like rural homestays and farming experiences. Second, design “cultural trails” linking spatial nodes such as ancient buildings, ancestral halls, and water systems to create cohesive visitor experiences. Third, train villagers as tour guides to enable direct community benefits from tourism services. Fourth, cultivate locally distinctive cultural and creative products to achieve deep integration between culture and industry.

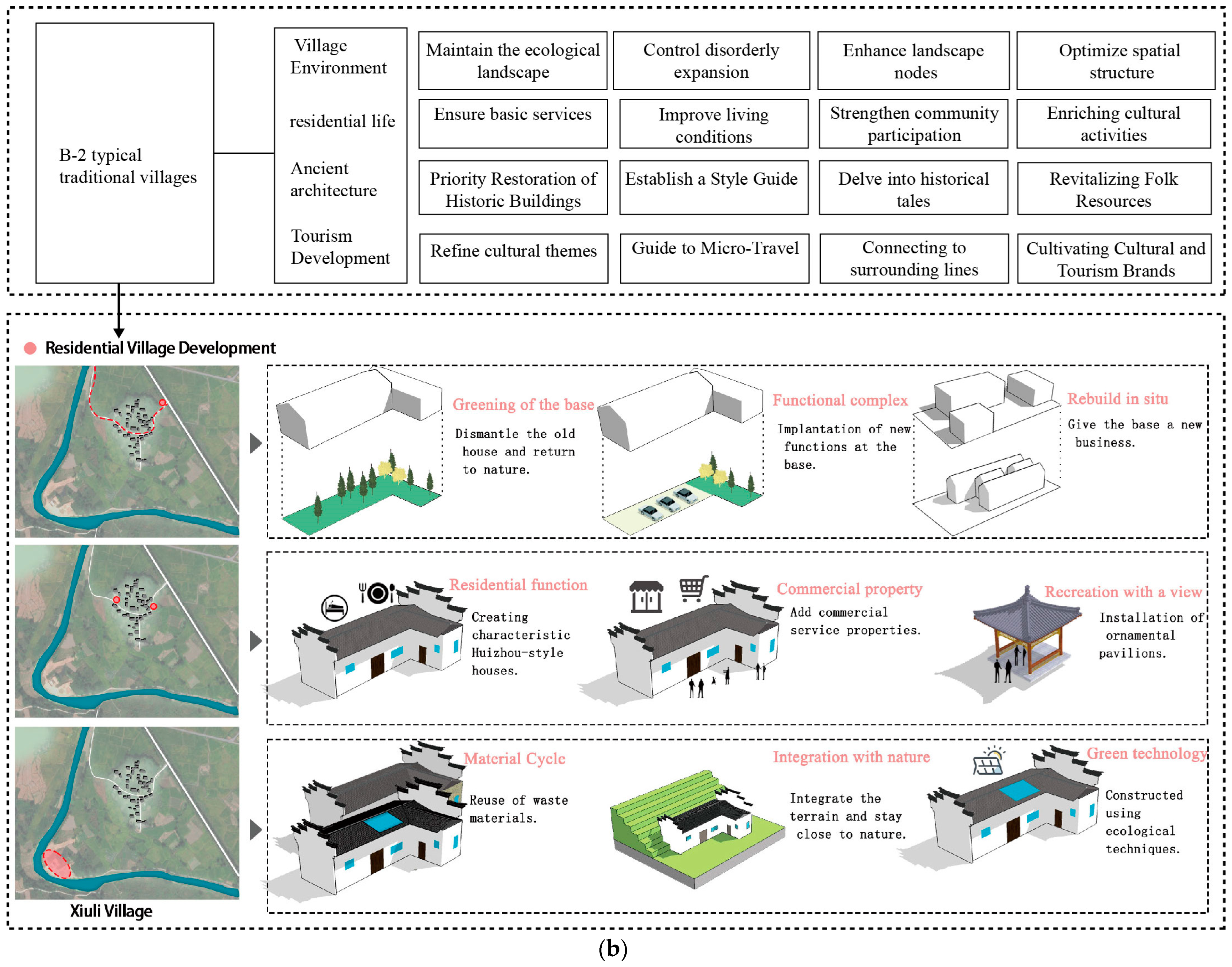

4.2. Development Strategy for Type B-2 Atypical Traditional Villages

The primary characteristics of B-2 type Atypical villages lie in their stable resident populations, well-maintained ecological environments, and relatively well-developed public service facilities, endowing them with strong daily residential functionality. However, these villages exhibit limited tourism development, lacking systematic tourism services and supporting facilities, resulting in insufficient overall appeal. Additionally, some traditional buildings suffer from deterioration and diminished architectural character, urgently requiring restoration and cultural revitalization measures to enhance the display and preservation of historical and cultural resources. Therefore, development strategies for such villages should be implemented across four dimensions: the village’s foundational conditions, residents’ livelihoods, historical resources, and tourism development (see

Figure 10b).

Regarding the village’s foundational landscape, spatial quality should be progressively enhanced based on ecological advantages and livable environments. First, implement micro-upgrades to the overall village layout, preserving the continuity of pastoral textures and traditional spatial structures. Second, improve infrastructure such as roads, drainage, and sewage treatment to further enhance living convenience. Third, optimize the village’s human environment through greening initiatives and public space design. Fourth, guide intensive land use to prevent disorderly construction from damaging the overall landscape.

Regarding residents’ livelihoods, the focus is on maintaining stability while promoting measured development. First, encourage the industrialization of locally distinctive agricultural products to boost farmers’ incomes. Second, enhance public services like education, healthcare, and elderly care to safeguard residents’ well-being. Third, foster resident participation in village governance and cultural activities to strengthen community cohesion. Fourth, moderately incorporate tourism needs into living facility construction, reserving space for future development.

Concerning historical resources, strengthen protective measures while emphasizing cultural revitalization. First, conduct surveys of traditional architecture to establish a graded and categorized protection registry. Second, implement precise restoration of damaged ancient structures to ensure the continuity of architectural character. Third, guide the enrichment of cultural functions through exhibitions, folk custom experiences, and other means to enhance identification among residents and tourists. Fourth, integrate village historical resources with education and research programs to expand cultural dissemination channels.

Regarding tourism development, adopt a small-scale, differentiated approach to gradually cultivate distinctive features. First, develop low-intensity tourism formats like rural leisure and experiential tours based on ecological environments and folk culture. Second, create “one village, one specialty” cultural tourism themes to enhance distinctiveness. Third, build small-scale tourism facilities such as visitor stations and guidance systems to meet basic needs. Fourth, explore “community participation” tourism models to directly benefit villagers and strengthen sustainability.

4.3. Limitations and Further Research

This study proposes a macrolevel identification framework for atypical traditional villages and provides differentiated development strategies based on a typological diagnosis. However, several limitations remain.

First, at the data level, Point of Interest (POI) data may contain potential biases. For instance, open platforms like AutoNavi Maps may have incomplete coverage of rural tourism facilities in remote areas, potentially affecting the accuracy of village functional identification. Second, field surveys face temporal and spatial limitations. Factors like seasonal variations make it difficult for resident activity data to comprehensively reflect year-round behavioral patterns, thereby restricting deeper insights into village spatial usage. Furthermore, this study analyzes Yixian County as a case example; its conclusions should be applied cautiously to other regions, and their applicability requires further validation.

Beyond these data and methodological constraints, the study has not systematically incorporated dynamic factors like population mobility and policy interventions, which often play crucial roles in the formation and evolution of village types. Future research should integrate dynamic monitoring data to deepen the analysis of various driving mechanisms.

To address these shortcomings, future research should conduct micro-scale spatial analyses to further explore architectural types, usage behaviors, and pattern evolution in different types of villages. Additionally, the research should be integrated with design practices to develop actionable renovation toolkits. We recommend introducing behavioral research methods to measure how spatial transformations affect the perceptual and emotional responses of residents and tourists. Through this shift in methodology, the focus of the research will expand from “type identification” to “spatial experience design”, providing deeper insights and practical guidance for the sustainable conservation and adaptive reuse of atypical traditional villages.

5. Conclusions

Against the backdrop of ongoing urbanization and the comprehensive rural revitalization strategy, traditional villages face numerous challenges. Compared to typical traditional villages, atypical traditional villages have long been underestimated and marginalized due to insufficient research attention, ambiguous identification criteria, and unclear development pathways. This has resulted in their cultural value and spatial potential not receiving the attention they deserve. This study focuses on the southern Anhui region, selecting 40 traditional villages as samples. An identification index system encompassing dimensions such as geographical location, cultural resources, tourism infrastructure, and facility conditions was constructed. The natural breakpoint method and cluster analysis were employed to classify village types. The results suggest that the sample includes a diverse distribution of village types, with typical traditional villages, B-1 type atypical villages, and B-2 type atypical villages each representing distinct proportions of the sample, reflecting the varying stages of development and characteristics across these village categories.

Based on this, the study proposes differentiated development pathways: For B-1 villages, while ensuring the preservation of existing ancient buildings, explore low-cost methods to enhance transportation accessibility, such as extending rural bus routes and establishing shared mobility networks. Simultaneously, introduce cultural tourism formats to promote “preservation through utilization”. B2-type villages should prioritize the restoration of traditional buildings and cultural empowerment, gradually improving tourism facilities to transform from a purely residential type to a balanced residential-tourism type, while typical traditional villages can promote regional collaborative development through their demonstration effect.

This study not only proposes an operational and replicable method for identifying and classifying atypical villages but also reveals, through specific metrics, the differences in building stock, transportation conditions, and development potential among various village types. Theoretically, it expands the typological framework for traditional village research. Practically, it provides reliable quantitative evidence and decision-making references for local governments to formulate differentiated conservation strategies, optimize public resource allocation, and promote regional coordinated development.