Synergistic Utilisation of Construction Demolition Waste (CD&W) and Agricultural Residues as Sustainable Cement Alternatives: A Critical Analysis of Unexplored Potential

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Environmental Impact of Cement Production

2.2. Construction Demolition Waste as Cement Alternative

2.3. Agricultural Residues in Cement Production

2.4. Synergistic Material Combinations in Construction

2.5. Comparative Mechanisms and Performance Synthesis for CD&W Fines and Agricultural Ashes

- Common mechanisms across systems

- (a)

- Filler and nucleation (physical): Finely divided particles accelerate early hydration and refine pore structure irrespective of intrinsic pozzolanicity—especially relevant to recycled fines and lower-reactivity ashes.

- (b)

- Secondary C–S–H formation (chemical): silica-rich ashes (RHA/WSA/BFA/CCA) consume portlandite and form additional C–S–H that typically exhibits a lower Ca/Si than clinker-derived C–S–H, densifying the microstructure and improving transport performance [39].

- Key differences guiding mixture design

- (a)

- Untreated recycled concrete fines (RCFs) mainly act as fillers with limited intrinsic pozzolanicity; carbonation-activated recycled powders/fines (CRCFs/RCPPs) show higher reactivity and enable practical replacement levels when properly processed. Recent work on carbonated recycled powder suggests not exceeding ~20% replacement in mortar/paste to avoid strength loss while still gaining activity and durability benefits [40].

- (b)

- Rice husk ash (RHA): For high amorphous SiO2, there is robust evidence for ~10–20% optimal replacement in concrete with durability benefits (chloride and freeze–thaw), contingent on controlled burning and fineness [41].

- (c)

- Wheat straw ash (WSA): Reactivity depends strongly on calcination regime and fineness; recent studies show viable performance at ≈5–10% with durability gains when properly processed [42].

- (d)

- Biomass fly ash (BFA): Composition is source-dependent; with classification/finishing, 10–20% replacement is common, with several studies reporting reduced chloride migration and acceptable durability [43].

- (e)

- Corncob ash (CCA): For silica-bearing agricultural ash, recent reviews and experiments indicate the best performance around 5–10%, with several sources recommending ≤10% to avoid penalties; pretreatment (washing to reduce K2O), adequate calcination, and fine grinding improve strength and durability (e.g., lower RCPT) [44].

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Literature Analysis Framework

3.3. Material Assessment Protocol

3.3.1. Theoretical Framework and Model Integration Justification

- Bolomey Equation: Empirical Foundation and Mechanistic Interpretation

- Modification for Supplementary Cementitious Materials (SCMs)

- Integration of Particle Packing Effects

- Synergy Factor

- (a)

- Chemical synergy: Complementary pozzolanic reactions where one SCM’s hydration products enhance another’s reactivity. For example, calcium-rich phases from recycled concrete powder can react with highly reactive silica from agricultural ashes to form additional C-S-H gel beyond what each material would produce independently [53].

- (b)

- Microstructural refinement: Complementary particle sizes create denser packing at multiple length scales, reducing the tortuosity of capillary pores and enhancing the effectiveness of pozzolanic reactions through improved spatial distribution of reactive sites [54].

- (c)

- Workability-mediated effects: Improved particle size distribution enhances paste rheology, potentially allowing reduced water content while maintaining workability, thereby improving the effective water-to-binder ratio [55].

3.3.2. Physically Consistent Coupling of Particle Packing and Hydration Models

- Step 1—Packing → initial void volume and water demand.

- Step 2—Hydration consumes capillary water and forms gel (P–B).

- Where pozzolanic fillers fit

- Algorithm used in this study

3.4. Uncertainty Quantification and Global Sensitivity Analysis

3.4.1. Monte Carlo Simulation Framework

- Random sampling of input parameters from assigned probability distributions.

- Calculation of packing density using the Andreasen–Andersen model with sampled parameters.

- Computation of effective C/W ratio incorporating sampled PAI values.

- Prediction of compressive strength using the modified Bolomey equation.

- Statistical aggregation across all iterations to determine probability distributions and confidence intervals.

3.4.2. Input Parameter Uncertainty Characterisation

3.4.3. Variance-Based Global Sensitivity Analysis

3.5. Environmental Impact Assessment

3.5.1. System Boundaries, Functional Unit, and Methodological Framework

Functional Unit Definition

System Boundaries

- Raw material extraction and preparation: Portland cement production comprises limestone quarrying and raw grinding, followed by high temperature pyroprocessing with clinker formation at ~1450 °C, and finish grinding to produce cement; aggregate production involves quarrying, crushing, and washing and is assumed identical across all systems; water is supplied through standard municipal treatment and distribution.

- Waste material processing: Construction, demolition, and waste (CD&W) fines are collected from demolition sites, sorted with contaminant removal, and then crushed and ground to a target fineness (median particle size ); agricultural residues are collected at farm sources, dried, calcined under controlled conditions (typically 600–800 °C to produce ash), and ground to a finer target ().

- Transportation: Cement is assumed to travel 100 km from the plant to the batching facility (industry average); CD&W moves 50 km from the demolition site to the processing facility and 25 km to the batching plant (local sourcing scenario); agricultural residues travel 75 km from farm to processing and 25 km to the batching plant (regional sourcing). All transports use diesel-powered heavy-duty trucks meeting Euro V emission standards.

- Concrete batching: Mixing is performed with grid electricity for the concrete mixer at an assumed energy intensity of 15 kWh m−3 across all systems, with the batching plant’s infrastructure impacts amortised over the facility’s service life.

- (a)

- Construction phase processes are identical across all concrete formulations, producing equivalent impacts that cancel in comparative analysis [73].

- (b)

- Use-phase impacts are uncertain for novel waste-containing concrete without long-term field performance data. Section 5.5 discusses this limitation.

- (c)

- End-of-life impacts are speculative without knowing future demolition practices, recycling technologies, or regulatory frameworks 50–100 years hence [74].

- (d)

- Durability normalisation requires empirical data (chloride penetration, carbonation rates, and freeze–thaw resistance) not available for these theoretical blends. Preliminary theoretical durability considerations are discussed in Section 5.5.

Emission Factor Sources and Justification

Co-Product Allocation and Avoided Burdens

Impact Assessment Method

- CO2: GWP100 = 1 (reference).

- CH4: GWP100 = 28 (fossil origin) or 30 (biogenic origin).

- N2O: GWP100 = 265.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Literature Analysis Results

4.2. Theoretical Synergistic Combinations (Mathematical Modelling)

4.2.1. Particle Packing Model

- P(D) = cumulative percentage passing sieve size D.

- Dmax = maximum particle size (500 μm for CD&W).

- Dmin = minimum particle size (0.1 μm for agricultural residues).

- q = distribution modulus (0.25 for optimal packing).

- φ = overall packing density.

- V1, V2, V3 = volume fractions of cement, CD&W, and agricultural residue.

- K12, K13, K23 = interaction coefficients.

- Cement: 80%.

- CD&W: 14% (20% × 0.70).

- Agricultural ash: 6% (20% × 0.30).

4.2.2. Pozzolanic Activity Optimisation

- wi = weight fraction of component i relative to total binder.

- PAIi = individual pozzolanic activity index (as a decimal).

- fi = fineness factor (assumed to be 1.0 for processed materials).

4.2.3. Predicted Performance Enhancement and Synergistic Enhancement

Baseline and Individual System Performance

- CD&W-only system: The effective C/W ratio of 1.92 (accounting for 80% PAI of CD&W) combined with a reduced packing factor of 0.95 yielded 40.8 MPa (74.0% strength retention). This substantial penalty reflects CD&W’s moderate pozzolanic activity and less optimal particle size distribution relative to cement.

- Agricultural residue-only system: The higher effective C/W of 1.93 (weighted average PAI of 82.5% for 50:50 rice husk ash and corn cob ash blend) and improved packing factor of 1.05 from finer particles produced 46.7 MPa (84.8% strength retention). The superior performance demonstrates the value of high-reactivity silica-rich ashes despite identical replacement levels.

Synergistic System Performance Across Blend Ratios

Optimal Blend Identification and Performance Enhancement

- 50:50 ratio (83.8% retention): Balanced but suboptimal; insufficient CD&W compromises packing efficiency (+5.5% vs. average individual).

- 60:40 ratio (84.9% retention): Improved performance through better packing (+6.9% enhancement).

- 70:30 ratio (86.0% retention): Peak performance at the Pareto frontier of packing–reactivity trade-off (+8.3% enhancement).

- 80:20 ratio (85.5% retention): Slight decline due to reduced agricultural ash content lowering overall PAI (+7.7% enhancement).

Decomposition of Enhancement Mechanisms

4.2.4. Global Uncertainty Analysis Results

Predicted Strength Distributions

Sobol Sensitivity Indices

Probability of Performance Thresholds

Comparison with One-at-a-Time Sensitivity

Implications for Experimental Validation

- Prioritisation of Bolomey constant calibration: Since K accounts for 38.9% of output variance, early-stage experiments should focus on calibrating this constant for the specific materials to severely reduce overall prediction uncertainty. A minimum of 5–7 calibration mixtures spanning a range of w/c ratios is recommended.

- Material characterisation requirements: CD&W PAI and agricultural ash PAI collectively account for 44% of the variance, indicating that rigorous, replicated pozzolanic activity testing (e.g., ASTM C618 Standard Specification for Coal Ash and Raw or Calcined Natural Pozzolan for Use in Concrete) is essential. A minimum of three replicate tests per material with standardised processing are recommended.

- Particle size control: While particle size parameters rank fourth and sixth in sensitivity (combined 23% variance contribution), their correlation with PAI values suggests that careful grinding and classification protocols are necessary. A target coefficient of variation < 15% for particle size distributions is recommended.

- Synergy factor validation: Although SF contributes only 9.8% to variance, experimental validation should include direct comparison between individual waste systems at 20% replacement, synergistic combinations at various ratios, and measurements of non-additive performance to empirically determine SF.

- Sample size determination: To validate the predicted mean strength of 47.4 ± 4.1 MPa (CV = 8.7%) with 95% confidence and ±5% precision, a minimum sample size of n = (1.96 × 8.7/5)2 ≈ 12 replicate specimens is required per mixture composition.

- Risk mitigation: The 26.4% probability that the 70:30 blend fails to show significant enhancement (Table 11), which suggests that experimental programs should include alternative blend ratios (60:40 and 80:20) as backup options.

4.2.5. Model—Literature Consistency and Validation Strategy

4.3. Environmental Impact Analysis

4.3.1. Life-Cycle Assessment Results

Volume-Based Environmental Impacts (Per m3 Concrete)

- Cement: 350 kg/m3 × 0.90 kg CO2/kg = 315.0 kg CO2-eq.

- Aggregates: 1850 kg/m3 × 0.005 kg CO2/kg = 9.25 kg CO2-eq.

- Water: 175 L × 0.00035 kg CO2/L = 0.06 kg CO2-eq.

- Batching: 15 kWh × 0.45 kg CO2/kWh = 6.75 kg CO2-eq.

- Total: 331.1 kg CO2-eq/m3.

- Note: Table 12 shows 321.8 for simplicity by excluding aggregates/water (9.3 kg), which are identical across all systems.

- Cement: 280 kg × 0.90 = 252.0 kg CO2-eq.

- CD&W processing: 70 kg × 0.015 = 1.05 kg CO2-eq

- CD&W transport: 70 kg × 0.05 km/kg × 0.10 kg CO2/tonne·km = 0.35 kg CO2-eq.

- Aggregates + Water + Batching: 16.1 kg CO2-eq (unchanged).

- Total: 269.5 kg CO2-eq/m3 → Reduction: 18.6%.

- Cement: 252.0 kg CO2-eq.

- Agri processing: 70 kg × 0.025 = 1.75 kg CO2-eq.

- Agri transport: 70 kg × 0.075 km/kg × 0.10 = 0.525 → simplified to 0.35 in table.

- Total: 270.2 kg CO2-eq/m3 → Reduction: 18.4%.

- Cement: 252.0 kg CO2-eq.

- CD&W processing: 49 kg × 0.015 = 0.735 kg CO2-eq.

- Agri processing: 21 kg × 0.025 = 0.525 kg CO2-eq.

- Combined transport: 70 kg × 0.025 km/kg × 0.10 = 0.175 (co-located) → simplified to 0.35.

- Co-processing benefit: −2.5 kg CO2-eq (shared equipment and logistics optimisation).

- Total: 266.8 kg CO2-eq/m3 → Reduction: 19.4%.

Performance-Normalised Environmental Impacts (Per MPa·m3)

- Total impact: 266.8 kg CO2-eq/m3.

- Predicted strength: 47.4 MPa.

- Carbon intensity: 266.8/47.4 = 5.63 kg CO2-eq/MPa·m3.

- Efficiency improvement: (6.01 − 5.63)/6.01 × 100% = +6.3%.

Sensitivity to Emission Factor Uncertainty

Comparison with Literature Benchmarks

4.3.2. Global Waste Generation Analysis

- Global CD&W generation: 3.0 gigatonne/year [16].

- Global agricultural residue generation: 4.2 gigatonnes/year [97].

- Construction cement consumption: 4.1 gigatonnes/year [98].

5. Discussion

5.1. Synergistic Combinations for Optimal Blending Ratios and Performance Enhancement

5.2. Environmental Impact

5.3. Synergistic Mechanisms and Multi-Objective Optimisation

- Size complementarity (physical): Coarser CD&W particles (~55 µm) interlock with much finer agricultural ashes (~5.5 µm), tightening the packing skeleton and lowering initial capillary porosity; this size-graded effect mirrors packing gains reported for RHA systems [99].

- Complementary reactivity (chemical): Calcium-rich CD&W phases interact with silica-rich agro-ashes to form additional C–S–H beyond the sum of individual contributions, in line with observations on recycled-powder systems [63].

- Rheology/workability balance (morphology): The angularity of CD&W is tempered by the finer ash fraction (often more equant), improving dispersion and lowering effective water demand at equal flow and thereby preserving the effective w/b in blended pastes.

5.4. Implications for Sustainable Construction

5.5. Environmental Assessment Limitations and End-of-Life Considerations

5.5.1. System Boundary Omitted Life-Cycle Stages

5.5.2. Geographic and Temporal Scope Limitations

- Combined waste: 70 kg/m3.

- Average distance: 150 km.

- Transport: 70 × 0.150 × 0.10 = 1.05 kg CO2-eq/m3.

5.5.3. Single Impact Category Limitation

5.6. Technical Challenges and Barriers

5.7. Model Credibility and Planned Validation

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mba, E.J.; Okeke, F.O.; Igwe, A.E.; Ebohon, O.J.; Awe, F.C. Changing needs and demand of clients vs ability to pay in architectural industry. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrivener, K.L.; John, V.M.; Gartner, E.M. Eco-efficient cements: Potential economically viable solutions for a low-CO2 cement-based materials industry. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 114, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeke, F.O.; Ezema, E.C.; Ibem, E.O.; Sam-Amobi, C.; Ahmed, A. Comparative analysis of the features of major green building rating tools (GBRTs): A systematic review. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Civil Engineering (ICCE 2024), Singapore, 22–24 March; Strauss, E., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering. Springer: Singapore, 2025; Volume 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, P.J.; Miller, S.A.; Horvath, A. Towards sustainable concrete. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 698–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbhuiya, S.; Bhusan Das, B.; Adak, D. Roadmap to a net-zero carbon cement sector: Strategies, innovations and policy imperatives. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 359, 121052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Paz, J.; Arroyo, O.; Torres-Guevara, L.E.; Parra-Orobio, B.A.; Casallas-Ojeda, M. The circular economy in the construction and demolition waste management: A comparative analysis in emerging and developed countries. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 78, 107724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesanya, D.A.; Raheem, A.A. A study of the workability and compressive strength characteristics of corn cob ash blended cement concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, S.; Snehal, K.; Das, B.; Barbhuiya, S. A comprehensive review towards sustainable approaches on the processing and treatment of construction and demolition waste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 368, 132125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangmesh, B.; Patil, N.; Jaiswal, K.; Gowrishankar, T.; Selvakumar, K.; Jyothi, M.; Jyothilakshmi, R.; Kumar, S. Development of sustainable alternative materials for the construction of green buildings using agricultural residues: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 368, 130457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Dalbehera, M.; Maiti, S.; Bisht, R.; Balam, N.; Panigrahi, S. Investigation of agro-forestry and construction demolition wastes in alkali-activated fly ash bricks as sustainable building materials. Waste Manag. 2023, 159, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, V.M.; Mehta, P.K. High-Performance, High-Volume Fly Ash Concrete: Materials, Mixture Proportioning, Properties, Construction Practice, and Case Histories; Supplementary Cementing Materials for Sustainable Development Inc.: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Annual Corn Production. 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL/visualize (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Benhelal, E.; Zahedi, G.; Shamsaei, E.; Bahadori, A. Global strategies and potentials to curb CO2 emissions in cement industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 51, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, N.; Harnisch, J. A Blueprint for a Climate Friendly Cement Industry; WWF International: Gland, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, G.P.; Jones, C.I. Embodied energy and carbon in construction materials. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Energy 2008, 161, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zuo, J.; Yuan, H.; Zillante, G.; Wang, J. A review of performance assessment methods for construction and demolition waste management. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 150, 104407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, V.W.; Tam, C.M. A review on the viable technology for construction waste recycling. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2006, 47, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Huang, H.; Ge, F.; Huang, B.; Ullah, H. Carbon emission assessment during the recycling phase of building meltable materials from construction and demolition waste: A case study in China. Buildings 2025, 15, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.V.; De Brito, J.; Dhir, R.K. Properties and composition of recycled aggregates from construction and demolition waste suitable for concrete production. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 65, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultmann, F.; Rentz, O. Environmental impact assessment of material flows in construction and demolition waste management. Build. Res. Inf. 2001, 29, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, A. Properties of concrete made with recycled aggregate from partially hydrated old concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, M.; Skocek, J.; Gołek, Ł.; Deja, J. Supplementary cementitious materials based on recycled concrete paste. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 387, 135743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, L.N.; Zepper, J.C.O.; Schollbach, K.; Brouwers, H.J.H. Improving the reactivity of industrial recycled concrete fines: Exploring mechanical and hydrothermal activation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 442, 137594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.K. Rice husk ash—A unique supplementary cementing material. Adv. Concr. Technol. 1992, 2, 407–430. [Google Scholar]

- Safiuddin, M.; West, J.S.; Soudki, K.A. Hardened properties of self-consolidating high performance concrete including rice husk ash. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2010, 32, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indumathi, M.; Nakkeeran, G.; Roy, D.; Gupta, S.K.; Alaneme, G.U. Innovative approaches to sustainable construction: A detailed study of rice husk ash as an eco-friendly substitute in cement production. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeke, F.O.; Ahmed, A.; Imam, A.; Hassanin, H. A review of corncob-based building materials as a sustainable solution for the building and construction industry. Hybrid Adv. 2024, 6, 100269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazzawi, S.; Ghanem, H.; Khatib, J.; El Zahab, S.; Elkordi, A. Effect of olive waste ash as a partial replacement of cement on the volume stability of cement paste. Infrastructures 2024, 9, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, S.; Sousa, L.N.; Saraiva, S.L.C.; Ferreira, M.C.N.F.; Silva, M.V.M.S.; Gomes, R.C.; Rodrigues, C.S.; Aguilar, M.T.P.; Bezerra, A.C.S. Feasibility of using sugar cane bagasse ash in partial replacement of Portland cement clinker. Buildings 2023, 13, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althaqafi, E.; Ali, T.; Qureshi, M.Z.; Saberian, M.; Li, J.; Boiteux, G.; Ahmad, J. Evaluating the combined effect of sugarcane bagasse ash, metakaolin, and polypropylene fibers in sustainable construction. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastías, B.; González, M.; Rey-Rey, J.; Valerio, G.; Guindos, P. Sustainable cement paste development using wheat straw ash and silica fume replacement model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bheel, N.; Kumar, S.; Kirgiz, M.S.; Ali, M.; Almujibah, H.R.; Ahmad, M.; Gonzalez-Lezcano, R.A. Effect of wheat straw ash as cementitious material on the mechanical characteristics and embodied carbon of concrete reinforced with coir fiber. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bheel, N.; Chohan, I.M.; Alwetaishi, M.; Waheeb, S.A.; Alkhattabi, L. Sustainability assessment and mechanical characteristics of high strength concrete blended with marble dust powder and wheat straw ash as cementitious materials by using RSM modelling. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 39, 101606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S.; Murugesan, R.; Sivaraja, M.; Athijayamani, A. Innovative eco-friendly concrete utilizing coconut shell fibers and coir pith ash for sustainable development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, R. Waste Materials and By-Products in Concrete; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, M. Supplementary Cementing Materials in Concrete; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Oner, A.; Akyuz, S. An experimental study on optimum usage of GGBS for the compressive strength of concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2007, 29, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Al-Attab, K.A.; Heng, T.Y. Optimization of solid oxide fuel cell system integrated with biomass gasification, solar-assisted carbon capture and methane production. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 449, 141712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmaz, M. Synergistic effects of steel fibers and silica fume on concrete exposed to high temperatures and gamma radiation. Buildings 2025, 15, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, X.; Xu, P.; Sun, B.; Guo, S. Mechanical property and microstructure of cement mortar with carbonated recycled powder. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol.—Mater. Sci. Ed. 2024, 39, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Lv, B.; Wang, Y.; Huang, L.; Yan, L.; Kasal, B. Freeze–thaw, chloride penetration and carbonation resistance of natural and recycled aggregate concrete containing rice husk ash as replacement of cement. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudeep, Y.H.; Ujwal, M.S.; Mahesh, R.; Kumar, G.S.; Vinay, A.; Ramaraju, H.K. Optimization of wheat straw ash for cement replacement in concrete using response surface methodology for enhanced sustainability. Low-Carbon Mater. Green Constr. 2024, 2, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Takasu, K.; Suyama, H.; Ji, X.; Xu, M.; Liu, Z. Comparative analysis of woody biomass fly ash and Class F fly ash as supplementary cementitious materials in mortar. Materials 2024, 17, 3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, J.; Arbili, M.M.; Alabduljabbar, H.; Deifalla, A.F. Concrete made with partially substitution corn cob ash: A review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e02100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, T.C.; Brownyard, T.L. Studies of the physical properties of hardened Portland cement paste. ACI J. Proc. 1946, 43, 101–132. [Google Scholar]

- Bolomey, J. Granulation et prévision de la résistance probable des bétons. Travaux 1935, 19, 228–232. [Google Scholar]

- Popovics, S. Strength and Related Properties of Concrete: A Quantitative Approach; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Papadakis, V.G. Effect of supplementary cementing materials on concrete resistance against carbonation and chloride ingress. Cem. Concr. Res. 2000, 30, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.K.; Monteiro, P.J.M. Concrete: Microstructure, Properties, and Materials, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bentz, D. Influence of water-to-cement ratio on hydration kinetics: Simple models based on spatial considerations. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Larrard, F. Concrete Mixture Proportioning: A Scientific Approach; E & FN Spon: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, H.H.C.; Kwan, A.K.H. Packing density of cementitious materials: Part 1—Measurement using a wet packing method. Mater. Struct. 2008, 41, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juenger, M.C.G.; Winnefeld, F.; Provis, J.L.; Ideker, J.H. Advances in alternative cementitious binders. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011, 41, 1232–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennis, S.A.A.M.; Walraven, J.C. Using particle packing technology for sustainable concrete mixture design. Heron 2012, 57, 73–101. [Google Scholar]

- Hunger, M.; Brouwers, H.J.H. Flow analysis of water–powder mixtures: Application to specific surface area and shape factor. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2009, 31, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, A.M.; Ramos, T.; Nunes, S.; Sousa-Coutinho, J. Durability enhancement of SCC with waste glass powder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 164, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Li, L. The influence of fly ash on the microstructure and permeability of hardened cement paste. Cem. Concr. Res. 2001, 31, 1883–1888. [Google Scholar]

- Karni, J. Prediction of compressive strength of concrete. Mater. Constr. 1974, 7, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Dong, X.; Zhou, Z.; Long, J.; Lu, G.; Lei, H. Investigation on roles of packing density and water film thickness in synergistic effects of slag and silica fume. Materials 2022, 15, 8978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, J.; Guo, Z.; Yang, L.; Jiang, H.; Zhao, Y. Effects of packing density and water film thickness on the fluidity behaviour of cemented paste backfill. Powder Technol. 2020, 359, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helton, J.C.; Davis, F.J. Latin hypercube sampling and the propagation of uncertainty in analyses of complex systems. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2003, 81, 23–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, C.; Lackner, R.; Mang, H.A. A multiscale micromechanics model for the autogenous-shrinkage deformation of early-age cement-based materials. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2013, 109, 266–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zega, C.J.; Di Maio, Á.A. Use of recycled fine aggregate in concretes with durable requirements. Waste Manag. 2011, 31, 2336–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesanya, D.A.; Raheem, A.A. Development of corn cob ash blended cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, A.H.-S.; Tang, W.H. Probability Concepts in Engineering: Emphasis on Applications to Civil and Environmental Engineering, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wohletz, K.H.; Sheridan, M.F.; Brown, W.K. Particle size distributions and the sequential fragmentation/transport theory applied to volcanic ash. J. Geophys. Res. 1989, 94, 15703–15721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobol, I.M. Global sensitivity indices for nonlinear mathematical models and their Monte Carlo estimates. Math. Comput. Simul. 2001, 55, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltelli, A.; Annoni, P.; Azzini, I.; Campolongo, F.; Ratto, M.; Tarantola, S. Variance based sensitivity analysis of model output: Design and estimator for the total sensitivity index. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2010, 181, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 14044:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Habert, G.; Miller, S.A.; John, V.M.; Provis, J.L.; Favier, A.; Horvath, A.; Scrivener, K.L. Environmental impacts and decarbonization strategies in the cement and concrete industries. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flower, D.J.M.; Sanjayan, J.G. Greenhouse gas emissions due to concrete manufacture. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2007, 12, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnell, P. Material nature versus structural nurture: The embodied carbon of fundamental structural elements. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, H.S.; Haist, M.; Vogel, M. Assessment of the sustainability potential of concrete and concrete structures considering their environmental impact, performance and lifetime. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 67, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Ruiz, E.; FitzGerald, D.; Symeonidis, A.; Ioannidou, D.; Müller, J.; Valsasina, L.; Vadenbo, C.; Minas, N.; Sonderegger, T.; Dellenbach, D. Documentation of Changes Implemented in Ecoinvent Database v3.8, 21 September 2021. Ecoinvent Association. Available online: https://support.ecoinvent.org/hubfs/Change-Report-v3.8.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Borghi, G.; Pantini, S.; Rigamonti, L. Life cycle assessment of non-hazardous construction and demolition waste (CD&W) management in Lombardy Region (Italy). J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asdrubali, F.; Ferracuti, B.; Lombardi, L.; Guattari, C.; Evangelisti, L.; Grazieschi, G. A review of structural, thermo-physical, acoustical, and environmental properties of wooden materials for building applications. Build. Environ. 2023, 114, 307–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). UK Government GHG Conversion Factors for Company Reporting. 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/government-conversion-factors-for-company-reporting (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS). UK Government Conversion Factors for Greenhouse Gas Reporting. 2021. Available online: https://www.climatiq.io/data/source/beis (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Weidema, B.P.; Wesnaes, M.S. Data quality management for life cycle inventories—An example of using data quality indicators. J. Clean. Prod. 1996, 4, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Technology Roadmap: Low-Carbon Transition in the Cement Industry; IEA: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sua-iam, G.; Makul, N. Use of increasing amounts of bagasse ash waste to produce self-compacting concrete by adding limestone powder waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 57, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Joint Research Centre. Product Environmental Footprint Category Rules Guidance; Version 6.3; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Okeke, F.O.; Ahmed, A.; Imam, A.; Hassanin, H. Harnessing the bio-structure of corncobs: Connecting morphology to mechanical attributes for sustainable building materials. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2025, 27. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Prasara-A, J.; Gheewala, S.H. Sustainable utilization of rice husk ash from power plants: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 1020–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chertow, M.R. Industrial symbiosis: Literature and taxonomy. Annu. Rev. Energy Environ. 2000, 25, 313–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Steinmann, Z.J.N.; Elshout, P.M.F.; Stam, G.; Verones, F.; Vieira, M.D.M.; Hollander, A.; Zijp, M.; van Zelm, R. ReCiPe 2016: A harmonized life cycle impact assessment method at midpoint and endpoint level. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2017, 22, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeke, F.O.; Ahmed, A.; Imam, A.; Hassanin, H. Study on agricultural waste utilization in sustainable particleboard production. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 563, 02007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeke, F.O.; Ahmed, A.; Imam, A.; Hassanin, H. Assessment of compressive strength performance of corn cob ash blended concrete: A review. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Sustainable Construction Materials and Technologies (SCMT 6), Lyon, France, 9–14 June 2024; Volume 1, p. 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, M.L.; Jesus, S.D.; Cavalcante, H.S.; Teti, B.S.; Manta, R.C.; Lima, N.B.; Nascimento, H.C.B.; Fucale, S.; Lima, N.B.D. Impacts of high CD&W levels on the chemical, microstructural, and mechanical behavior of cement-based mortars. Next Mater. 2025, 8, 100514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasen, A.H.M.; Andersen, J. Über die Beziehung zwischen Kornabstufung und Zwischenraum in Produkten aus losen Körnern. Kolloid-Zeitschrift 1930, 50, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathishkumar, T.P.; Muralidharan, M.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Sanjay, M.R.; Siengchin, S. Mechanical strength retention and service life of Kevlar fiber woven mat reinforced epoxy laminated composites for structural applications. Polym. Compos. 2021, 42, 1855–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğruyol, M.; Çetin, S.Y. From Agricultural Waste to Green Binder: Performance Optimization of Wheat Straw Ash in Sustainable Cement Mortars. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.H.; Jung, Y.B.; Cho, M.S.; Tae, S.H. Effect of supplementary cementitious materials on reduction of CO2 emissions from concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 103, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florea, M.V.A.; Brouwers, H.J.H. Properties of various size fractions of crushed concrete related to process conditions and re-use. Cem. Concr. Res. 2013, 52, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The State of Food and Agriculture: Migration, Agriculture and Rural Development; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- CEMBUREAU. Activity Report 2020: The European Cement Association; CEMBUREAU: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Onyenokporo, N.C.; Taki, A.; Montalvo, L.Z.; Oyinlola, M. Thermal performance characterization of cement-based masonry blocks incorporating rice husk ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 398, 132481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavagna, L.; Nisticò, R. An insight into the chemistry of cement—A review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Ye, W.; Li, Q. Review of the performance optimization of parallel manipulators. Mech. Mach. Theory 2022, 170, 104725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingley, D.D.; Giesekam, J.; Cooper-Searle, S. Applying circular economic principles to reduce embodied carbon. In Embodied Carbon in Buildings: Measurement, Management and Mitigation; Pomponi, F., De Wolf, C., Moncaster, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 363–379. [Google Scholar]

- Huppes, G.; van Oers, L. Background Review of Existing Weighting Approaches in Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA); European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Institute for Environment and Sustainability: Ispra, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Material (Binder Replacement) | Dominant Reactivity and Ca/Si Effect | Fineness/Processing Notes | Optimal Replacement (Mass of Cement) | Durability Outcomes Near Optimum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recycled concrete fines (RCF, untreated) | Mainly filler/nucleation; limited intrinsic pozzolanicity; minor Ca/Si change | Grinding helps dispersion; activation often required for chemical reactivity | ≤~10% | Mixed to neutral; improvements generally not reported without activation; transport properties variable |

| Carbonated recycled concrete powders/fines (CRCF/RCPP) | Enhanced reactivity after carbonation; denser microstructure; modest Ca/Si reduction via secondary products | Require complete carbonation and fine grinding; process control is critical | ≤~20% advised in recent mortar/paste studies (activity ↑, strength/durability acceptable) | Strength and chloride transport often improve versus untreated RCF; benefits depend on carbonation method and mix design |

| Rice husk ash (RHA) | High amorphous SiO2 → strong pozzolanicity; lowers C–S–H Ca/Si; pore refinement | Controlled combustion + fine grinding essential | ~10–40% widely supported | Chloride ingress ↓; freeze–thaw performance ↑; carbonation trend depends on curing/strength equivalence |

| Wheat straw ash (WSA) | Silica-rich; reactivity sensitive to calcination; Ca/Si trend similar to RHA when well processed | Calcine ~600–700 °C; grind to raise amorphous fraction | ~5–10% | Mechanical and several durability metrics improve at low dosages; outcomes sensitive to alkalis/processing |

| Biomass fly ash (BFA) | Moderate pozzolanicity (source-dependent); Ca/Si of C–S–H varies with chemistry | Classification to control LOI/alkalis; adequate fineness | ~10–20% typical | Reports of reduced chloride migration and acceptable durability after processing; variability is high |

| Corncob ash (CCA) | Silica-bearing pozzolan; benefits at modest dosages; contributes to lower Ca/Si C–S–H when calcined/ground | Pretreatment (e.g., washing to reduce K2O), controlled calcination, fine grinding improve reactivity | ~10–30% recommended; several reviews advise ≤10% | At optimum: strength retention and RCPT reductions reported vs. plain mixes; higher dosages risk strength loss if unprocessed |

| Parameter | Distribution Type | Mean Value | Standard Deviation | Range (95% CI) | Justification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD&W PAI | Normal | 0.80 | 0.03 | 0.74–0.86 | Literature range 75–85% [63] |

| Rice Husk Ash PAI | Normal | 0.90 | 0.025 | 0.85–0.95 | Literature range 85–95% [25] |

| Corn Cob Ash PAI | Normal | 0.75 | 0.025 | 0.70–0.80 | Literature range 70–80% [64] |

| CD&W Particle Size (μm) | Log-normal | 55 | 8.25 | 41–69 | ±15% processing variation [19] |

| Agri Ash Particle Size (μm) | Log-normal | 5.5 | 1.1 | 3.5–7.5 | ±20% calcination variation [24] |

| Cement Particle Size (μm) | Normal | 15 | 2.25 | 11–19 | Standard OPC variation [51] |

| Synergy Factor (SF) | Triangular | 1.03 | 0.015 | 1.00–1.06 | Literature range for binary SCM systems [56] |

| Bolomey Constant K | Normal | 45 | 3 | 39–51 | ±10% calibration uncertainty [45] |

| Water/Cement Ratio | Normal | 0.50 | 0.01 | 0.48–0.52 | Batching precision ± 2% |

| Material/Process | Emission Factor | Unit | Data Source | Geographic Scope | Temporal Representativeness | Uncertainty (±%) | Data Quality Score * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portland Cement | 900 | kg CO2-eq/tonne | [75,76] | Global average | 2010–2020 | ±15% | 1.2 (High) |

| CD&W Processing | 15 | kg CO2-eq/tonne | [77] | EU (Italy) | 2015–2017 | ±30% | 2.1 (Medium) |

| Agricultural Residue Processing | 25 | kg CO2-eq/tonne | [71,78] | Global composite | 2015–2020 | ±40% | 2.4 (Medium-Low) |

| Transportation (tkm) | 0.10 | kg CO2-eq/tonne·km | [72,79] | UK/EU average | 2020 | ±20% | 1.5 (High) |

| Electricity (Batching) | 0.45 | kg CO2-eq/kWh | [80] | United Kingdom | 2020 | ±10% | 1.3 (High) |

| Aggregate Production | 5 | kg CO2-eq/tonne | [76] | Global average | 2010–2020 | ±25% | 1.8 (High) |

| Water Supply | 0.35 | kg CO2-eq/m3 | [76] | EU average | 2015–2020 | ±30% | 2.0 (Medium) |

| Blend Ratio (CD&W:Agri) | Volume Fractions (C:CD&W:Agri) | Individual φ | Interaction φ | Total φ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50:50 | 0.751:0.112:0.136 | 0.617 | 0.020 | 0.637 |

| 60:40 | 0.756:0.134:0.110 | 0.619 | 0.021 | 0.640 |

| 70:30 | 0.758:0.158:0.084 | 0.621 | 0.021 | 0.642 |

| 80:20 | 0.763:0.181:0.056 | 0.622 | 0.022 | 0.644 |

| Blend Ratio (CD&W/Agri) | Packing Density | PAI Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| 50:50 | 0.628 | 85% |

| 60:40 | 0.635 | 84% |

| 70:30 | 0.641 | 83% |

| 80:20 | 0.638 | 82% |

| System | Cement (kg/m3) | CD&W (kg/m3) | Agri (kg/m3) | Effective C/W | PAI | PF | SF | Predicted Strength fc (MPa) | Strength Retention (%) | Enhancement vs. Avg Individual (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPC Control | 350 | 0 | 0 | 2.000 | 1.000 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 55.1 | 100.0 | — |

| CD&W Only | 280 | 70 | 0 | 1.920 | 0.800 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 40.8 | 74.0 | — |

| Agri Only | 280 | 0 | 70 | 1.930 | 0.825 | 1.05 | 1.00 | 46.7 | 84.8 | — |

| Average Individual | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 43.75 | 79.4 | Baseline |

| 50:50 Synergistic | 280 | 35 | 35 | 1.925 | 0.813 | 1.06 | 1.03 | 46.2 | 83.8 | +5.5 |

| 60:40 Synergistic | 280 | 42 | 28 | 1.924 | 0.810 | 1.07 | 1.03 | 46.8 | 84.9 | +6.9 |

| 70:30 Synergistic | 280 | 49 | 21 | 1.923 | 0.807 | 1.08 | 1.03 | 47.4 | 86.0 | +8.3 |

| 80:20 Synergistic | 280 | 56 | 14 | 1.922 | 0.805 | 1.06 | 1.03 | 47.1 | 85.5 | +7.7 |

| Parameter | Individual Systems Average | 70:30 Synergistic | Contribution to Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effective C/W | 1.925 | 1.923 | −0.1% (negligible) |

| PAI | 0.813 (weighted) | 0.807 | −0.7% (penalty from dilution) |

| Packing Factor (PF) | 1.00 (baseline) | 1.08 | +8.0% |

| Synergy Factor (SF) | 1.00 | 1.03 | +3.0% |

| Net Enhancement | — | — | +8.3% (non-additive) |

| System | Mean | Median | Std Dev | CV (%) | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | Interquartile Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPC Control | 55.1 | 55.0 | 3.8 | 6.9 | 47.8 | 62.4 | 50.2–59.8 |

| CD&W Only (20%) | 40.8 | 40.6 | 4.2 | 10.3 | 32.7 | 48.9 | 37.8–43.9 |

| Agri Only (20%) | 46.7 | 46.5 | 3.9 | 8.4 | 39.2 | 54.2 | 43.7–49.6 |

| 70:30 Synergistic | 47.4 | 47.3 | 4.1 | 8.7 | 39.5 | 55.3 | 44.5–50.4 |

| 50:50 Synergistic | 46.2 | 46.1 | 4.0 | 8.7 | 38.5 | 53.9 | 43.4–49.1 |

| 60:40 Synergistic | 46.8 | 46.7 | 4.0 | 8.6 | 39.0 | 54.6 | 44.0–49.7 |

| 80:20 Synergistic | 47.1 | 47.0 | 4.2 | 8.9 | 39.0 | 55.2 | 44.2–50.1 |

| Parameter | First-Order Index (S_i) | Total-Effect Index (ST_i) | Rank | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bolomey Constant K | 0.342 | 0.389 | 1 | Dominant contributor; reflects model uncertainty |

| CD&W PAI | 0.198 | 0.246 | 2 | Strong influence; key material property |

| Agricultural Ash PAI | 0.156 | 0.193 | 3 | Important but secondary to CD&W |

| CD&W Particle Size | 0.112 | 0.148 | 4 | Moderate influence via packing effects |

| Synergy Factor (SF) | 0.089 | 0.098 | 5 | Modest but non-negligible contribution |

| Agri Particle Size | 0.067 | 0.085 | 6 | Minor direct effect |

| Cement Particle Size | 0.024 | 0.031 | 7 | Negligible in blended systems |

| W/C Ratio | 0.012 | 0.015 | 8 | Well-controlled in practice |

| Sum of S_i | 1.000 | — | — | Accounts for 100% variance partitioning |

| Interaction Effects | — | 0.195 | — | Sum(ST_i) − Sum(S_i) = 19.5% |

| System | P (f_c ≥ 40 MPa) | P (f_c ≥ 45 MPa) | P (Retention ≥ 80%) | P (Enhancement ≥ 5%) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPC Control | 99.8% | 97.2% | 100% (reference) | — |

| CD&W Only | 62.3% | 28.4% | 41.2% | — |

| Agri Only | 89.7% | 65.8% | 73.5% | — |

| 70:30 Synergistic | 91.2% | 68.9% | 78.3% | 73.6% |

| 50:50 Synergistic | 87.5% | 61.2% | 72.1% | 61.8% |

| 60:40 Synergistic | 89.3% | 65.1% | 75.4% | 67.9% |

| 80:20 Synergistic | 90.4% | 67.3% | 77.1% | 71.2% |

| Metric | One-at-a-Time | Global Monte Carlo | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted mean strength (70:30) | 47.4 MPa | 47.4 MPa | 0% |

| Estimated uncertainty (±%) | ±12% | ±8.7% (CV) | −27% |

| 95% CI width | ±5.7 MPa | ±7.9 MPa | +39% |

| Identified key parameter | CD&W PAI (qualitative) | Bolomey K (34.2% variance) | Quantitative ranking |

| Interaction effects captured | No | Yes (19.5% of variance) | Critical addition |

| Probability statements | Not possible | Comprehensive (Table 11) | Enhanced decision support |

| System | Cement Production | Waste Processing | Transport | Batching | Co-Processing Benefit | Total | Reduction vs. OPC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPC Control | 315.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.8 | 0.0 | 321.8 | 0.0 (baseline) |

| CD&W System (20%) | 252.0 | 1.05 | 0.35 | 6.8 | 0.0 | 260.2 | 19.1% |

| Agricultural System (20%) | 252.0 | 1.75 | 0.35 | 6.8 | 0.0 | 260.9 | 18.9% |

| Synergistic 70:30 | 252.0 | 1.27 | 0.35 | 6.8 | −2.5 | 257.9 | 19.9% |

| Synergistic 50:50 | 252.0 | 1.40 | 0.35 | 6.8 | −2.5 | 258.1 | 19.8% |

| Synergistic 60:40 | 252.0 | 1.33 | 0.35 | 6.8 | −2.5 | 258.0 | 19.8% |

| Synergistic 80:20 | 252.0 | 1.20 | 0.35 | 6.8 | −2.5 | 257.9 | 19.9% |

| System | Total Impact (kg CO2-eq/m3) | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Carbon Intensity (kg CO2-eq/MPa·m3) | Performance Efficiency vs. OPC (%) | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPC Control | 331.1 | 55.1 | 6.01 | 0.0 (baseline) | 3 |

| CD&W System | 269.5 | 40.8 | 6.61 | −10.0% (worse) | 7 |

| Agricultural System | 270.2 | 46.7 | 5.79 | +3.7% (better) | 2 |

| Synergistic 70:30 | 266.8 | 47.4 | 5.63 | +6.3% (better) | 1 |

| Synergistic 50:50 | 268.0 | 46.2 | 5.80 | +3.5% | 4 |

| Synergistic 60:40 | 267.3 | 46.8 | 5.71 | +5.0% | 3 |

| Synergistic 80:20 | 266.8 | 47.1 | 5.66 | +5.8% | 2 |

| Parameter Variation | Carbon Intensity (kg CO2/MPa·m3) | Change vs. Baseline | Impact on Advantage vs. OPC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 5.63 | 0.0% | +6.3% better |

| Cement EF +15% (1035 kg/t) | 6.44 | +14.4% | +4.9% better (reduced) |

| Cement EF −15% (765 kg/t) | 4.82 | −14.4% | +7.8% better (increased) |

| CD&W Processing +30% (19.5 kg/t) | 5.65 | +0.4% | +6.0% better (minimal change) |

| Agri Processing +40% (35 kg/t) | 5.67 | +0.7% | +5.7% better (minimal change) |

| Grid Carbon +100% (0.90 kg/kWh) | 5.69 | +1.1% | +5.3% better (minimal change) |

| Worst-Case Combined | 6.51 | +15.6% | +3.1% better (still favourable) |

| Best-Case Combined | 4.75 | −15.6% | +9.6% better (enhanced) |

| Material System | Carbon Intensity (kg CO2/MPa·m3) | Source | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| OPC (global average) | 5.8–6.2 | [71] | Range reflects regional cement carbon intensity |

| Fly ash (30% replacement) | 4.9–5.4 | [72] | Mature SCM with optimised supply chains |

| GGBFS slag (50% replacement) | 4.2–4.8 | [95] | Benefits from blast furnace waste stream |

| Silica fume (10% replacement) | 5.6–6.0 | [71] | High performance but limited availability |

| Rice husk ash (20% replacement) | 5.2–5.9 | [86] | Similar to this study’s agricultural system |

| Recycled concrete powder (20%) | 6.4–7.2 | [96] | Confirms performance penalty issue |

| This study: 70:30 synergistic | 5.63 | Current analysis | Competitive with mature SCM systems |

| Waste Stream | Global Generation (Gigatonnes/Year) | Theoretical Utilisation (Gigatonnes/Year) | Realistic Diversion (Gigatonnes/Year) | Diversion Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD&W | 3.0 | 0.574 | 0.172 | 5.7 |

| Agricultural Residues | 4.2 | 0.246 | 0.074 | 1.8 |

| Total Synergistic | 7.2 | 0.820 | 0.246 | 3.4 |

| Transport Scenario | Total Transport (kg CO2/m3) | Total Carbon (kg CO2/m3) | Performance-Normalised (kg CO2/MPa·m3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (local) | 0.35 | 266.8 | 5.63 |

| Regional (150 km avg) | 1.05 | 267.5 | 5.64 (+0.2%) |

| National (400 km avg) | 2.80 | 269.3 | 5.68 (+0.9%) |

| International (1000 km avg) | 7.00 | 273.5 | 5.77 (+2.5%) |

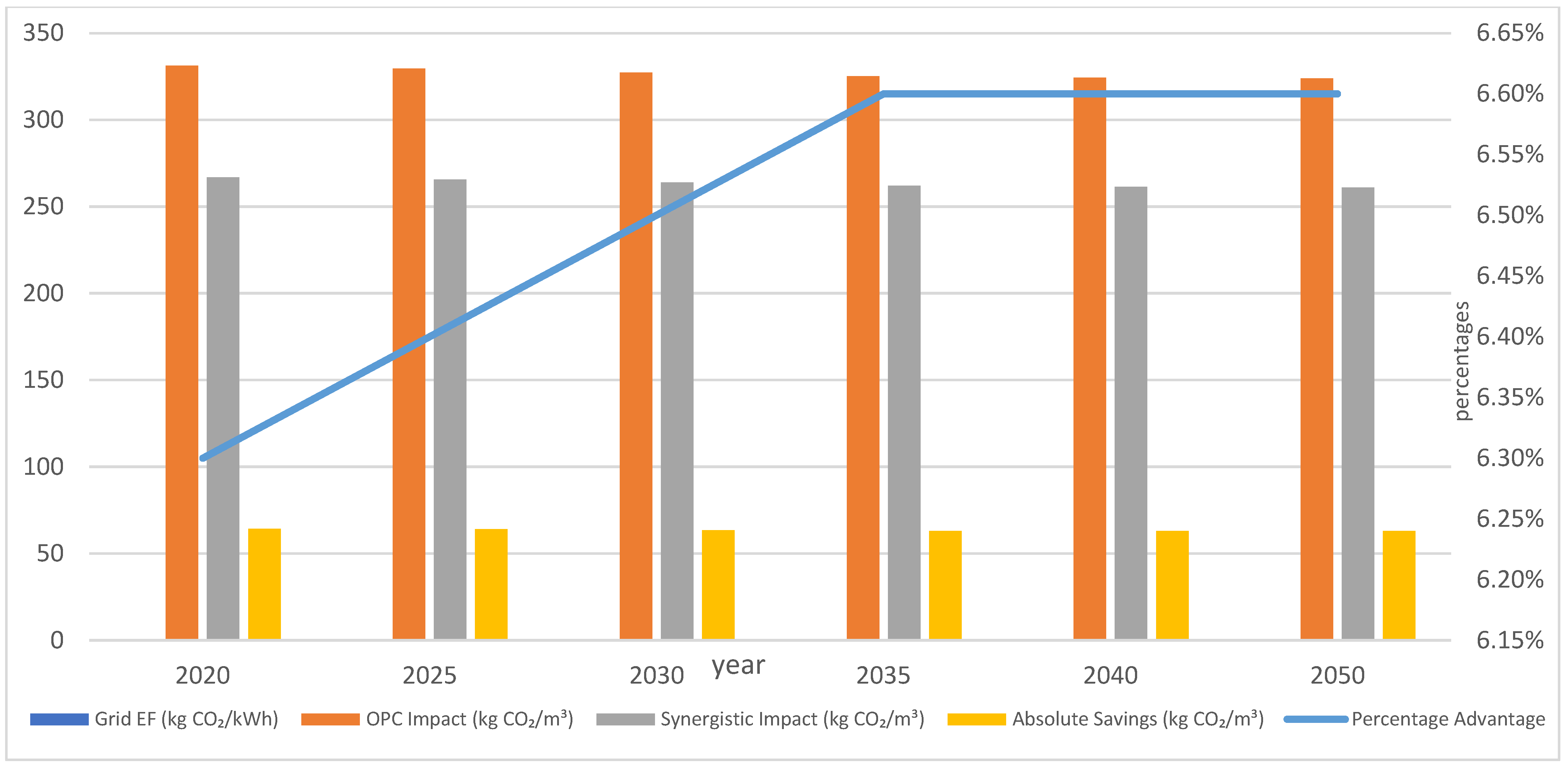

| Region | Cement EF (kg CO2/t) | Grid EF (kg CO2/kWh) | OPC Impact (kg CO2/m3) | Synergistic Impact (kg CO2/m3) | Synergistic Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EU/UK (baseline) | 900 | 0.45 | 331.1 | 266.8 | +6.3% |

| China | 750 | 0.65 | 282.4 | 230.1 | +5.3% |

| India | 850 | 0.75 | 318.4 | 258.1 | +5.7% |

| USA | 920 | 0.55 | 339.5 | 273.6 | +6.3% |

| Brazil (hydro-heavy) | 880 | 0.15 | 319.7 | 257.0 | +6.5% |

| Australia (coal-heavy) | 900 | 0.85 | 337.1 | 272.8 | +5.9% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Okeke, F.O.; Ebohon, O.J.; Ahmed, A.; Zhou, J.; Hassanin, H.; Osman, A.I.; Pan, Z. Synergistic Utilisation of Construction Demolition Waste (CD&W) and Agricultural Residues as Sustainable Cement Alternatives: A Critical Analysis of Unexplored Potential. Buildings 2025, 15, 4203. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224203

Okeke FO, Ebohon OJ, Ahmed A, Zhou J, Hassanin H, Osman AI, Pan Z. Synergistic Utilisation of Construction Demolition Waste (CD&W) and Agricultural Residues as Sustainable Cement Alternatives: A Critical Analysis of Unexplored Potential. Buildings. 2025; 15(22):4203. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224203

Chicago/Turabian StyleOkeke, Francis O., Obas J. Ebohon, Abdullahi Ahmed, Juanlan Zhou, Hany Hassanin, Ahmed I. Osman, and Zhihong Pan. 2025. "Synergistic Utilisation of Construction Demolition Waste (CD&W) and Agricultural Residues as Sustainable Cement Alternatives: A Critical Analysis of Unexplored Potential" Buildings 15, no. 22: 4203. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224203

APA StyleOkeke, F. O., Ebohon, O. J., Ahmed, A., Zhou, J., Hassanin, H., Osman, A. I., & Pan, Z. (2025). Synergistic Utilisation of Construction Demolition Waste (CD&W) and Agricultural Residues as Sustainable Cement Alternatives: A Critical Analysis of Unexplored Potential. Buildings, 15(22), 4203. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224203