Benchmarking Conventional Machine Learning Models for Dynamic Soil Property Prediction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Objectives

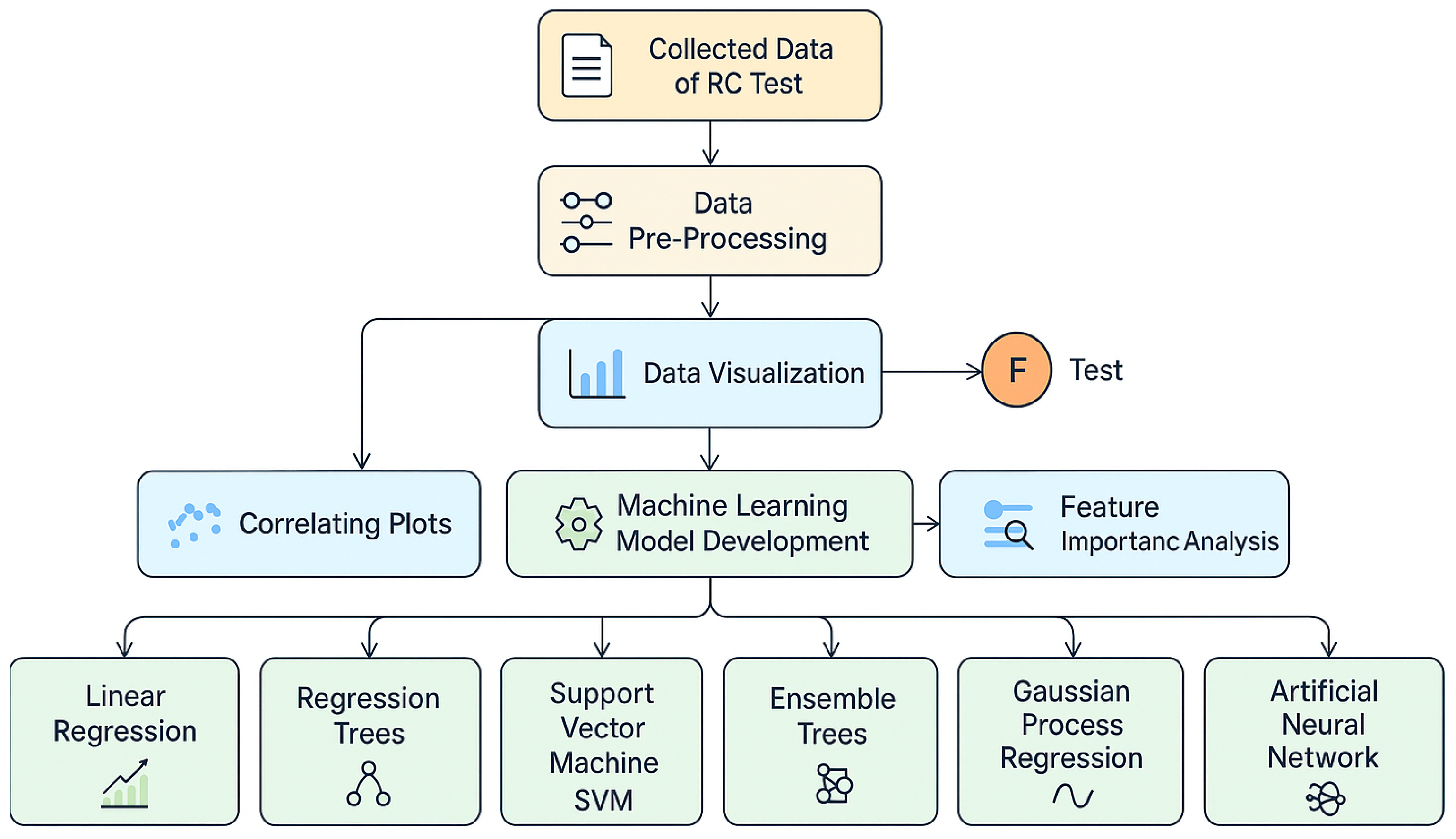

- Curate the 2738-record multi-site RC/CTS archive, summarize variable ranges, and report descriptive statistics to contextualize observed variability in and .

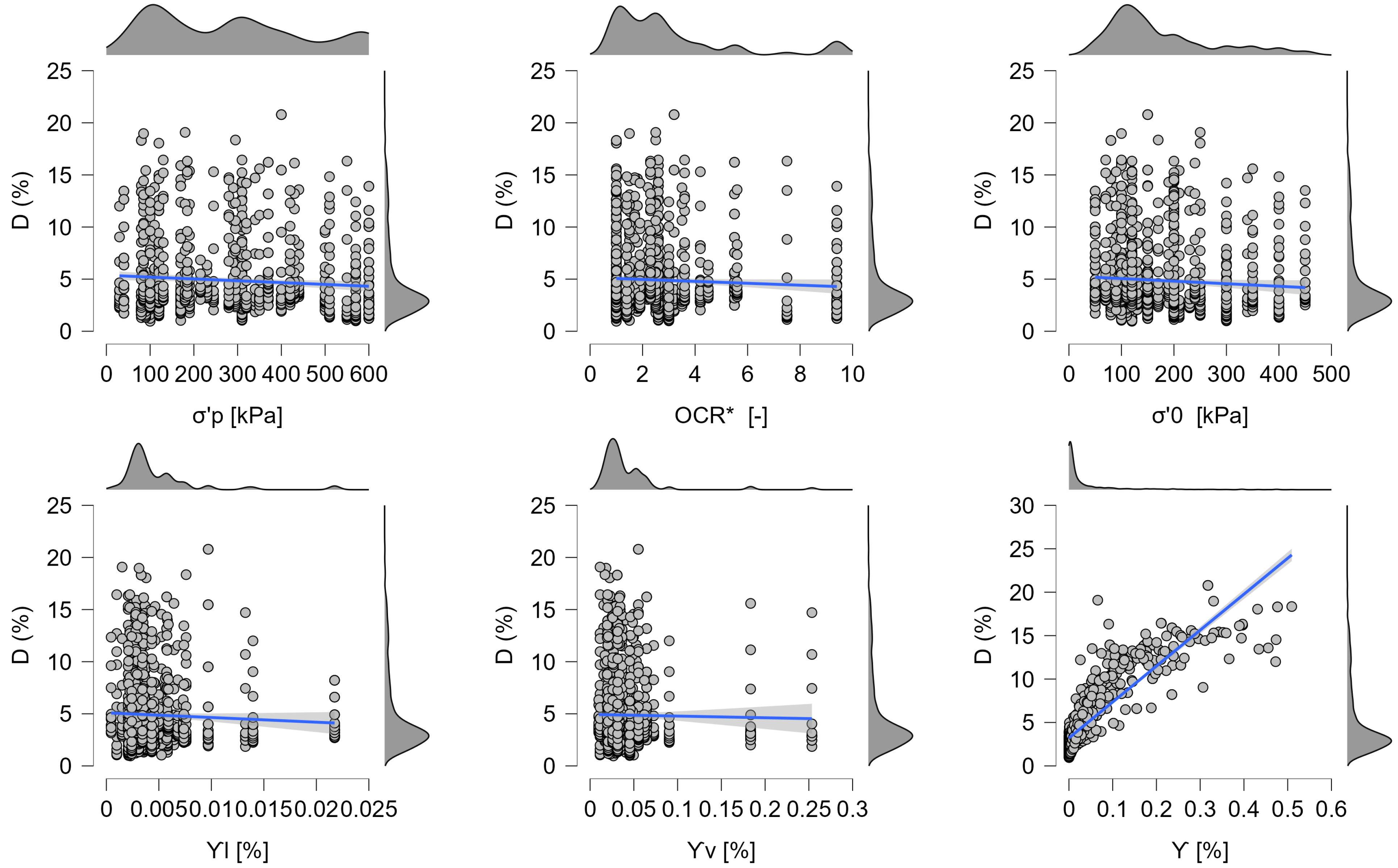

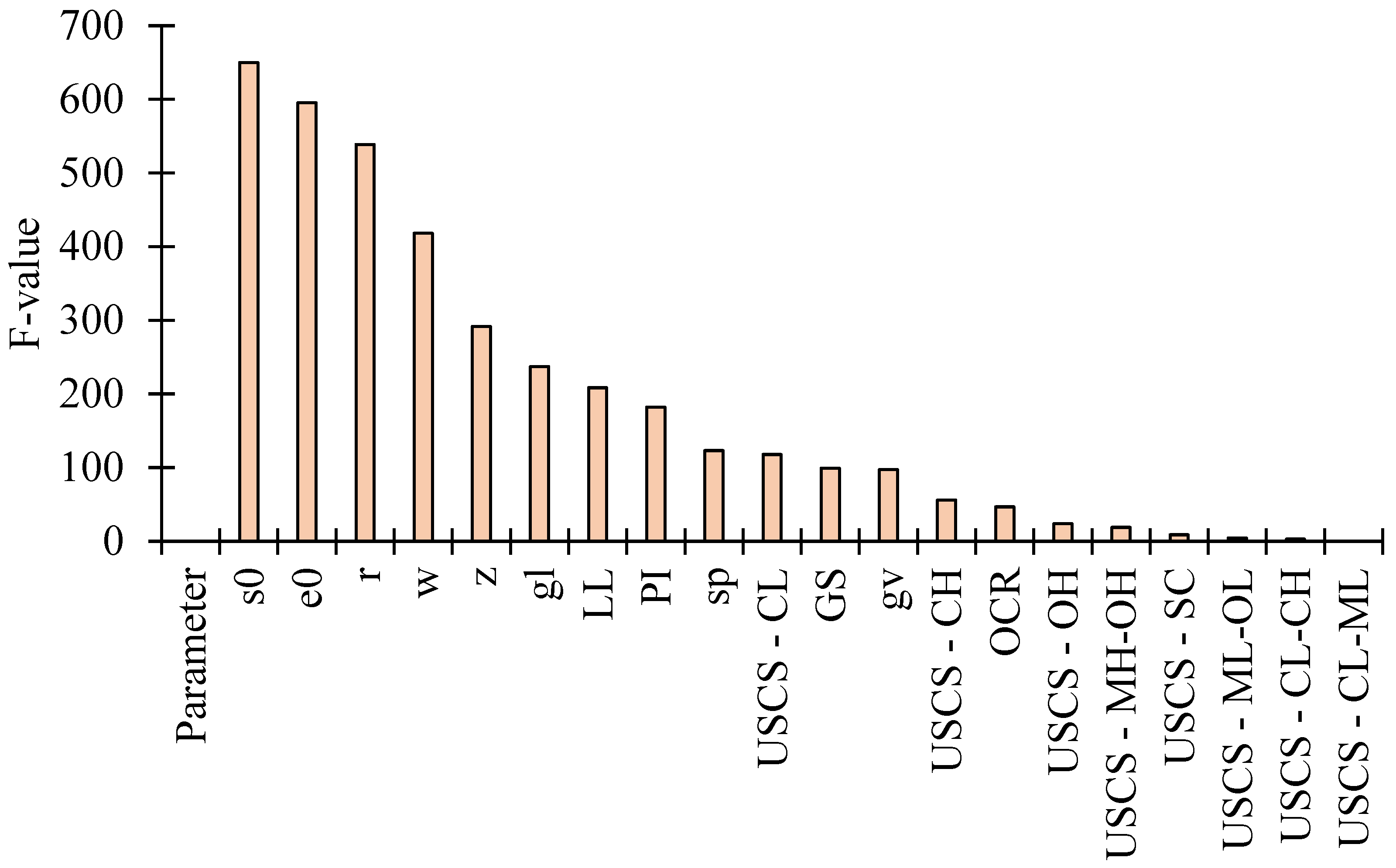

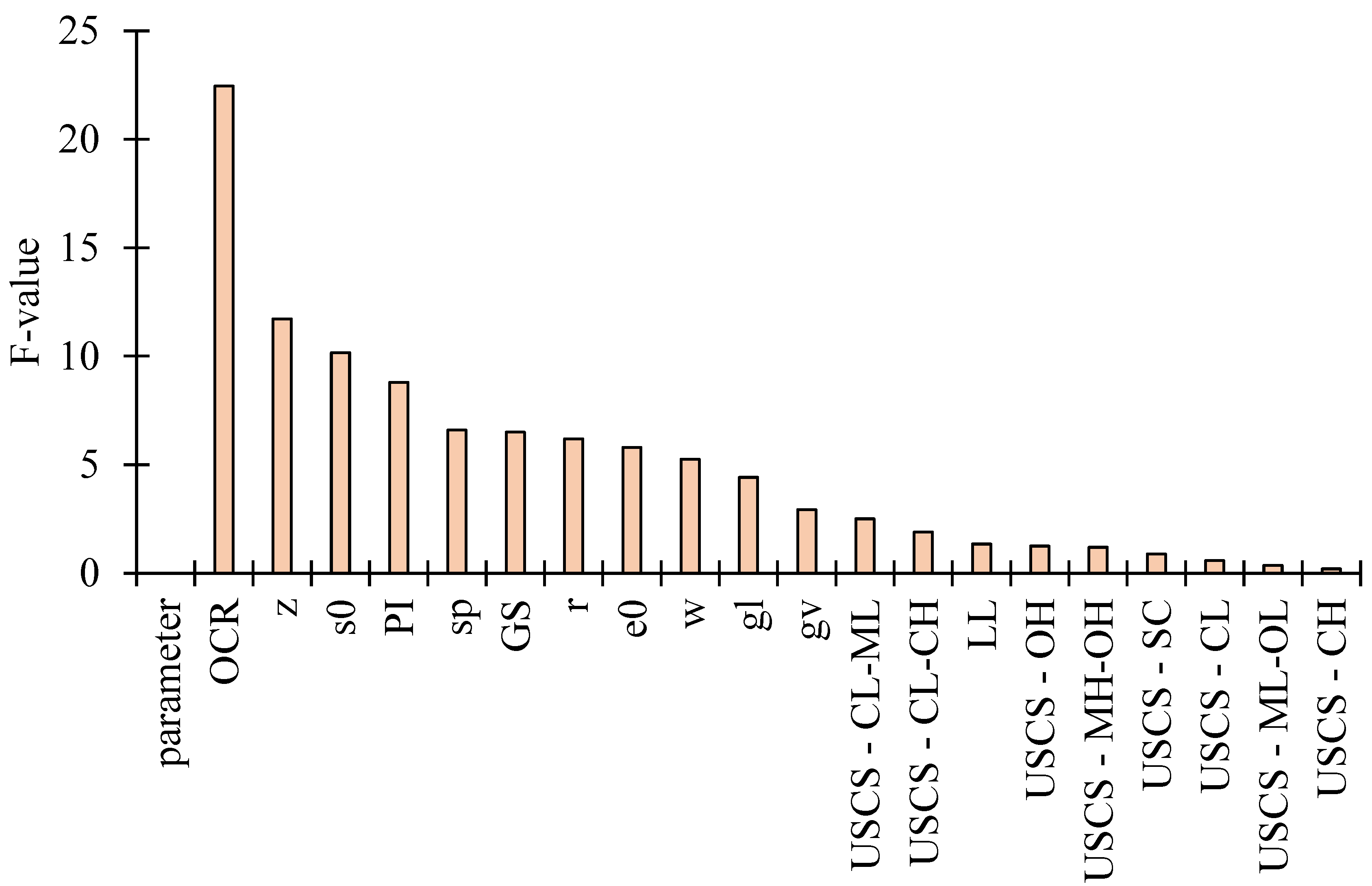

- Apply an F-test-based feature screening and basic sanity/coverage checks to identify influential inputs and specify the domain of applicability (e.g., ranges of , , , , , , , and ).

- Fit linear baselines, single trees, tree ensembles (bagging/boosting), SVMs, Gaussian process regression, kernel regression, and feed-forward ANNs using uniform 10-fold cross-validation with consistent preprocessing and hyperparameter tuning.

- Compare models using RMSE, MAE, and MSE, while recording training time to quantify the accuracy–computational cost trade-off; evaluate all-feature.

- Rank feature influence and generate partial-dependence trends to verify mechanics-consistent effects (e.g., with , with ; with ) and highlight key interactions (e.g., , , ).

- Determine a default operational model for routine use and a companion model for uncertainty (prediction intervals), and state input checks and usage conditions.

- Demonstrate how model outputs produce code-compatible and curves and simple modifiers for existing design workflows (equivalent-linear site response, foundation impedances), enabling risk-aware design decisions.

3. Methodology

4. Machine Learning Models (MLMs)

4.1. Regression Decision Trees

4.2. Support Vector Machine

4.3. Ensembles

4.4. Gaussian Process Regression

- Squared Exponential Kernel:

- Matern Kernel:

- Exponential Kernel:

- Rational Quadratic Kernel:where α depends on the input distance.

4.5. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs)

4.6. Kernel Methods (Regularized Kernel Regression)

5. Results and Discussion

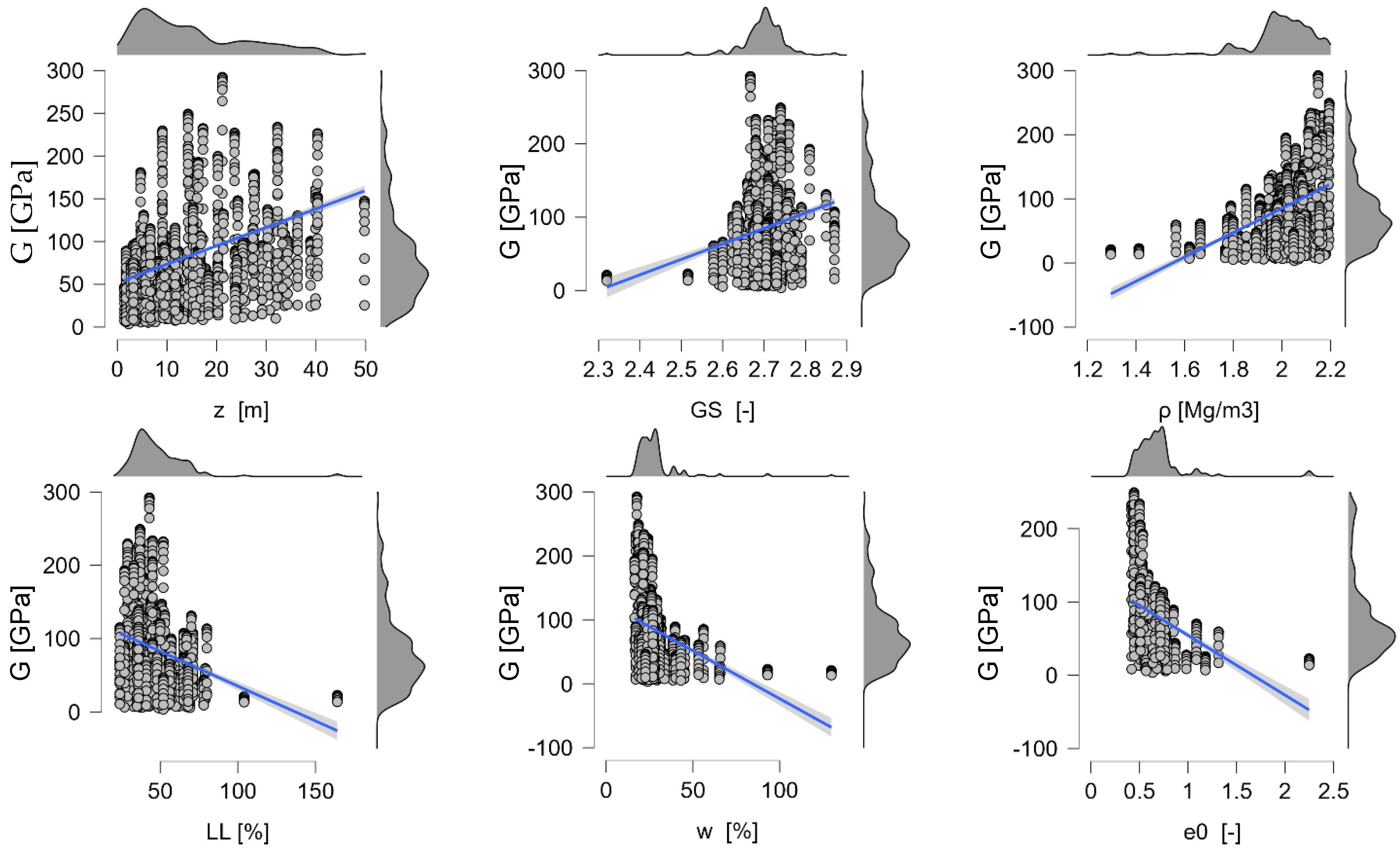

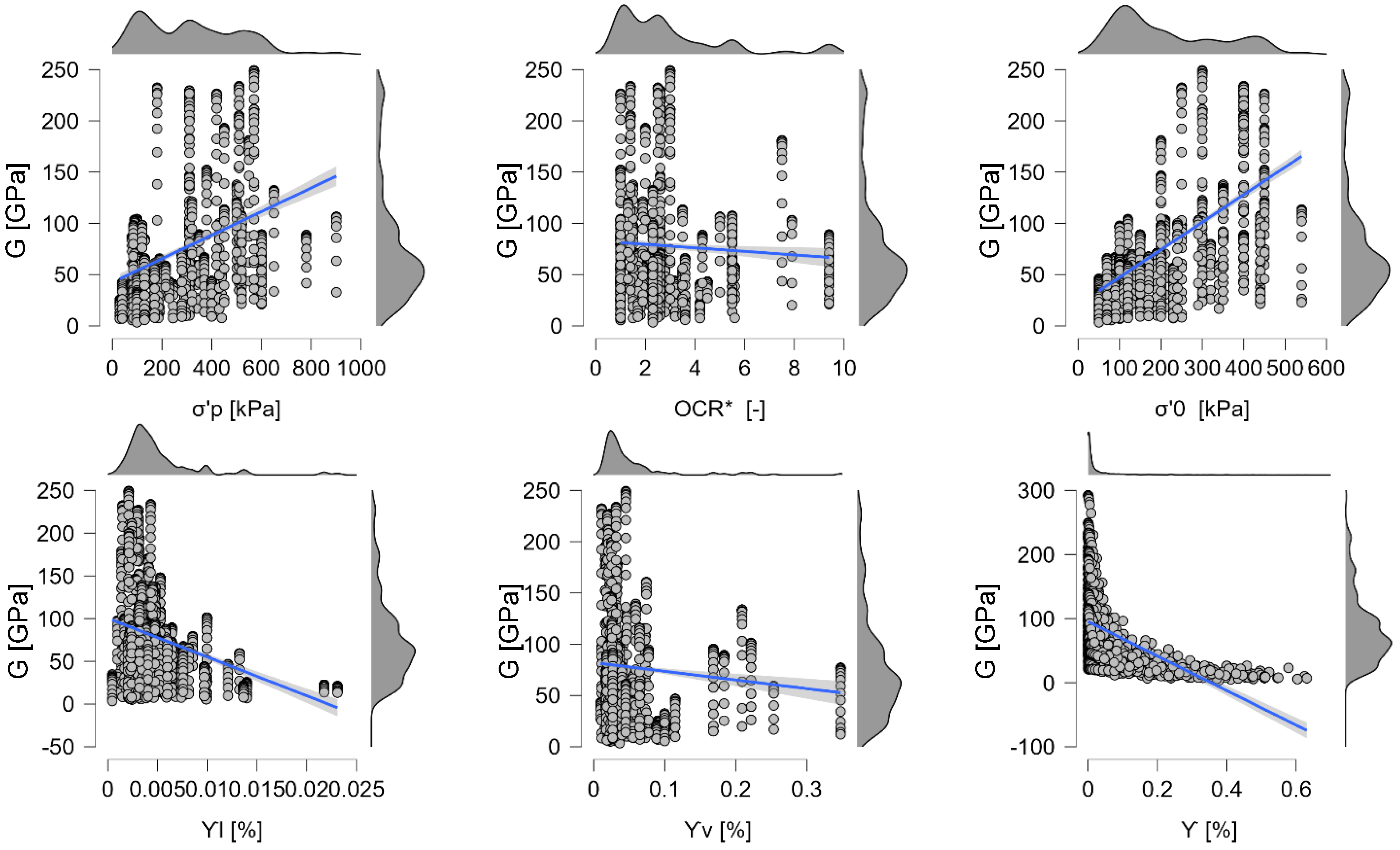

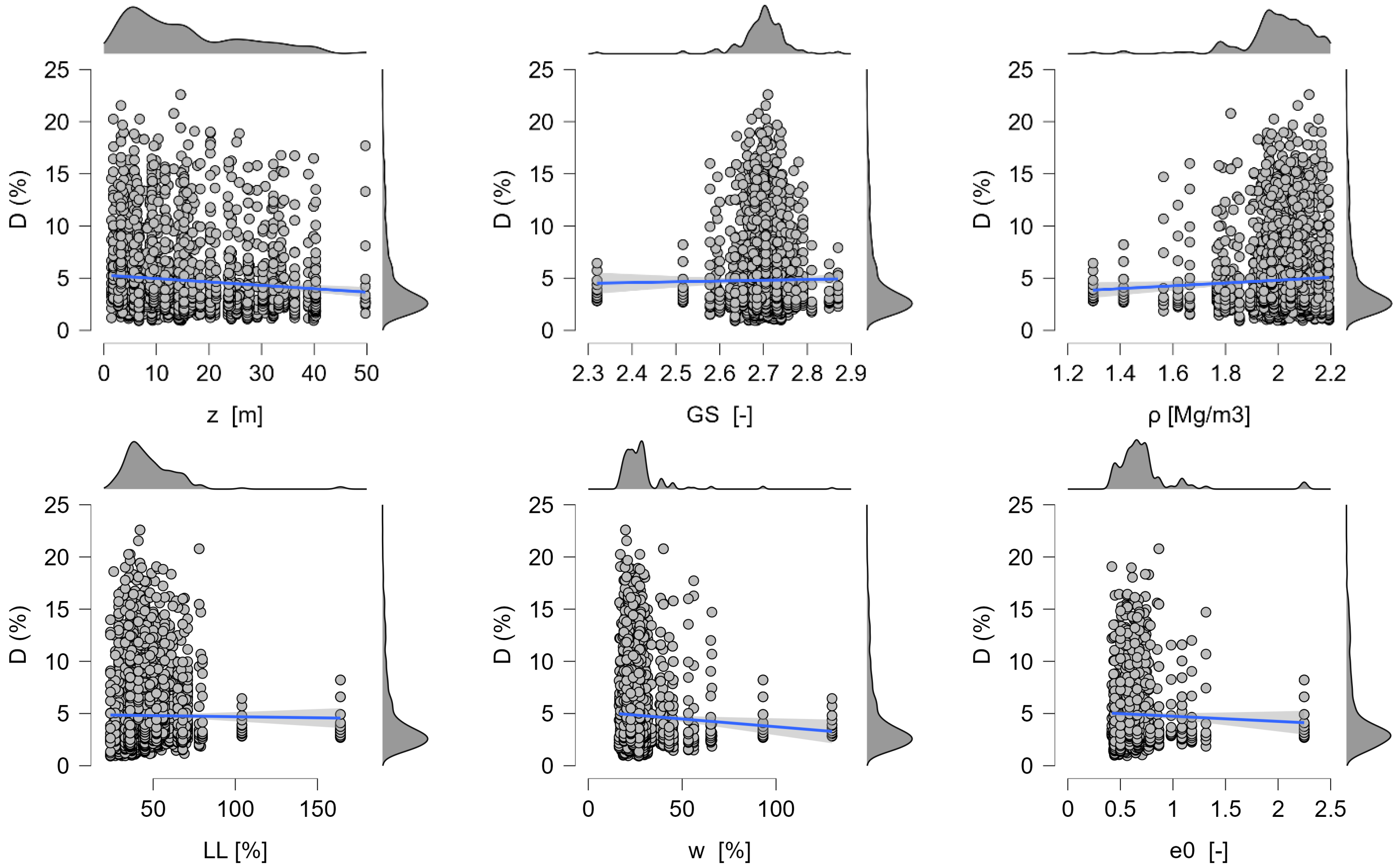

5.1. Feature Importance

5.2. Shear Modulus Prediction Models

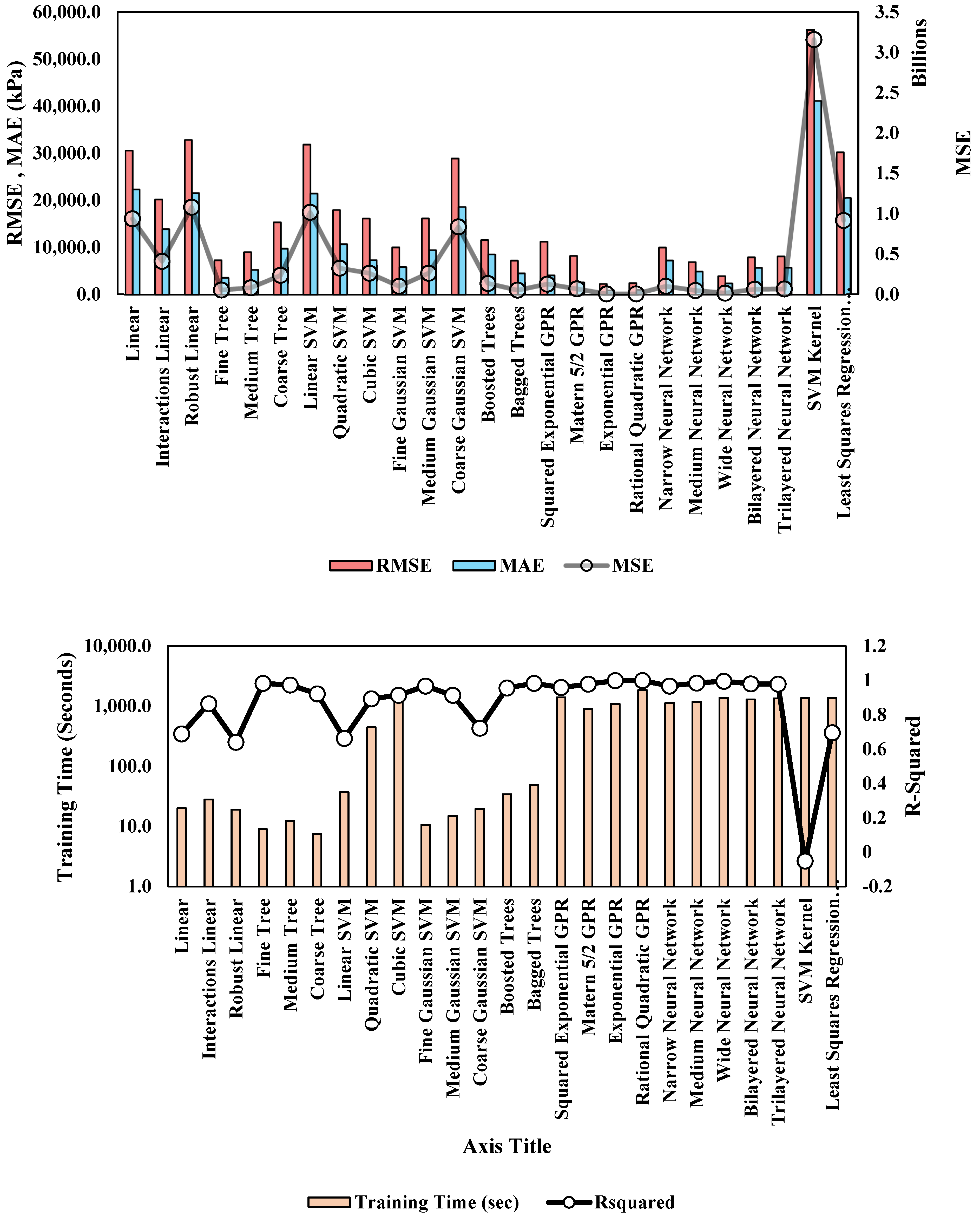

5.2.1. Models’ Performance for Predicting Shear Modulus

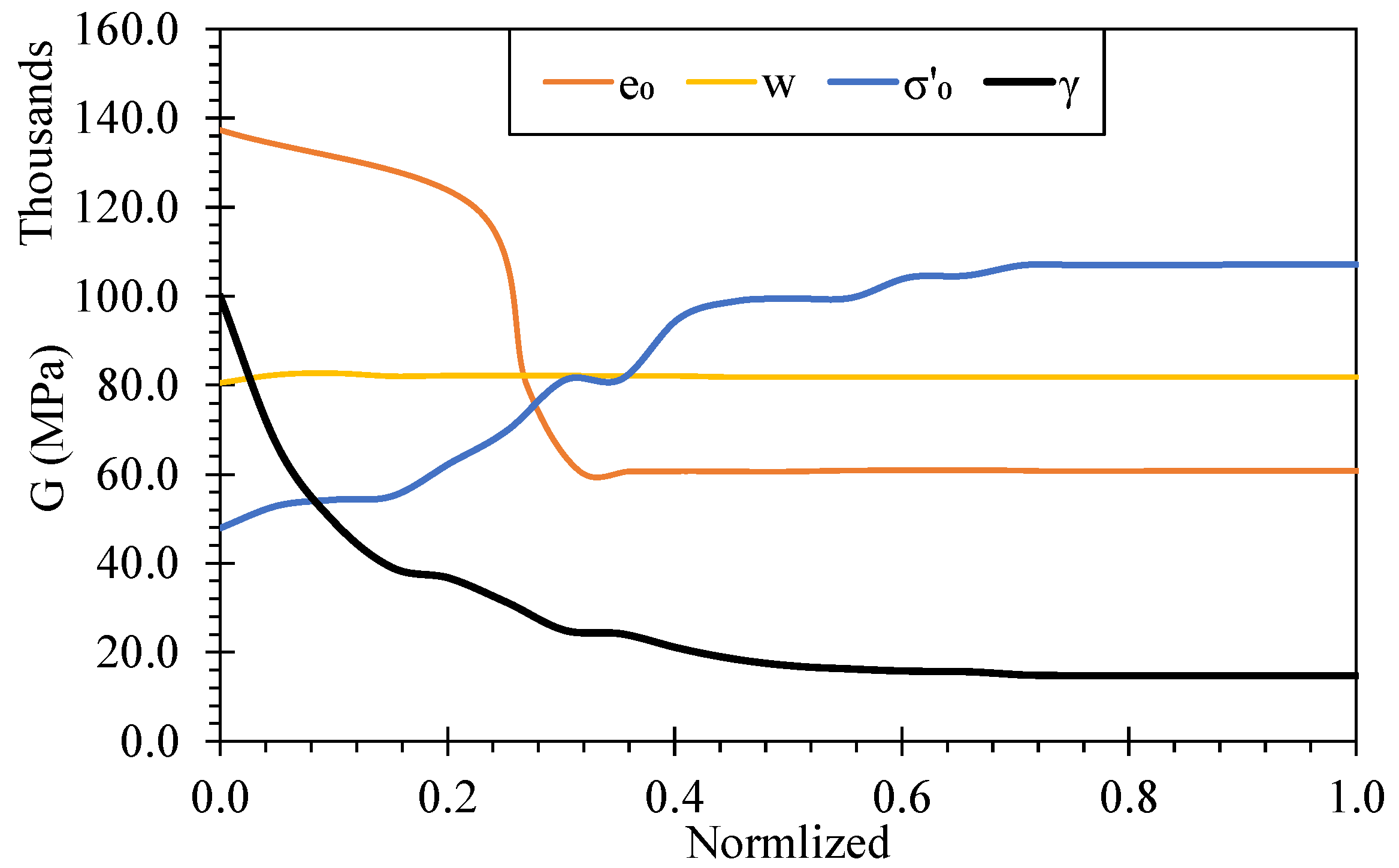

5.2.2. Partial Dependencies for Shear Modulus Models

- increases monotonically with and tends to plateau at higher normalized values, indicating diminishing stiffness gains once confinement is sufficiently high. This reflects stress-stiffening of the soil skeleton.

- decreases with . A sharper drop occurs across intermediate normalized values, consistent with the transition from denser to looser fabrics and loss of interparticle contact density.

- decays steeply at small strains, then approaches an asymptote, capturing the familiar stiffness-reduction behavior with increasing cyclic strain.

- Within the sampled range, the marginal effect of is weak to slightly negative after accounting for and plasticity indices, suggesting that the moisture state chiefly acts through correlated descriptors or interactions.

5.2.3. Computational Efficiency for Predicting Shear Modulus Models

5.3. Damping Prediction Models

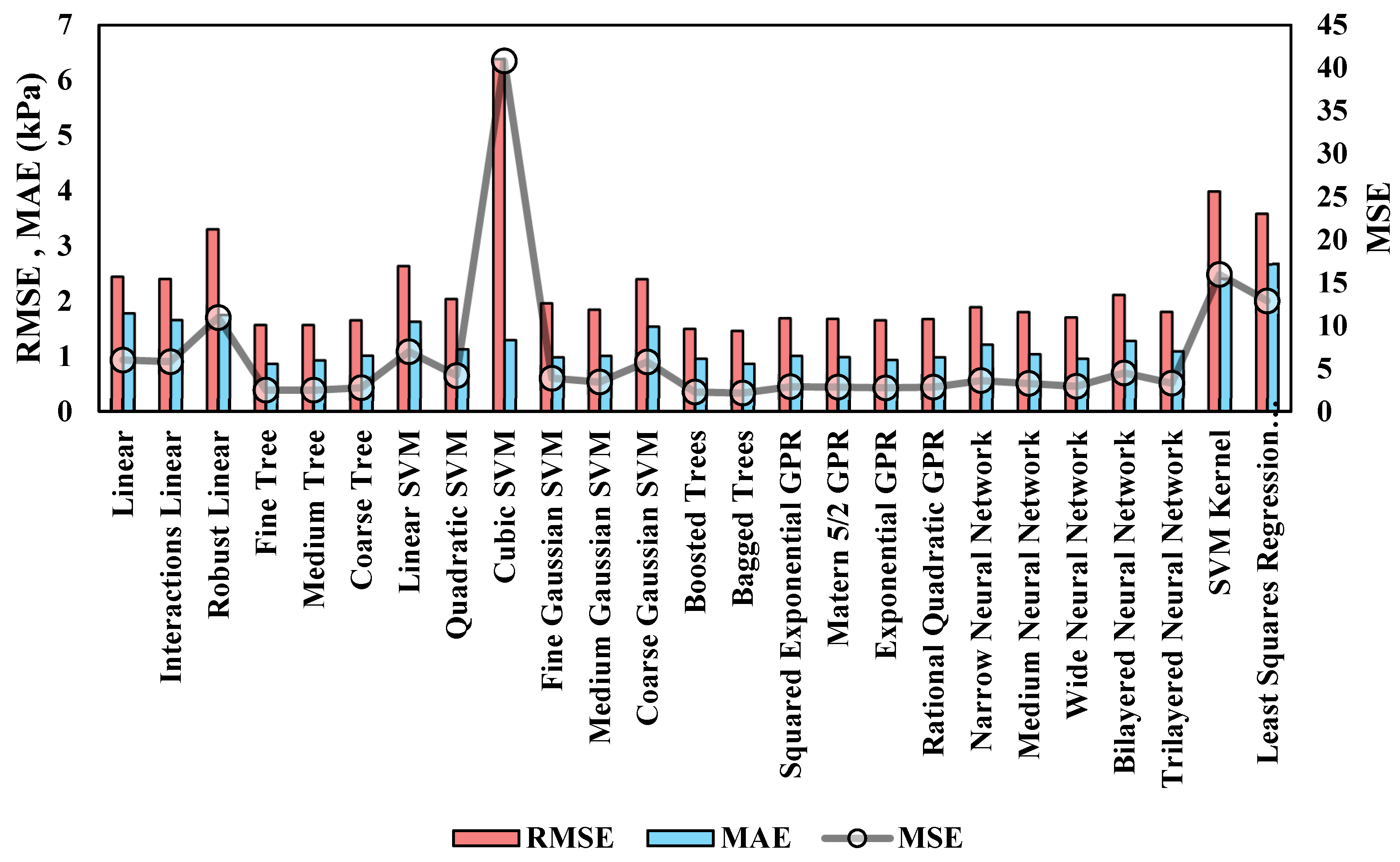

5.3.1. Models’ Performance for Predicting Damping

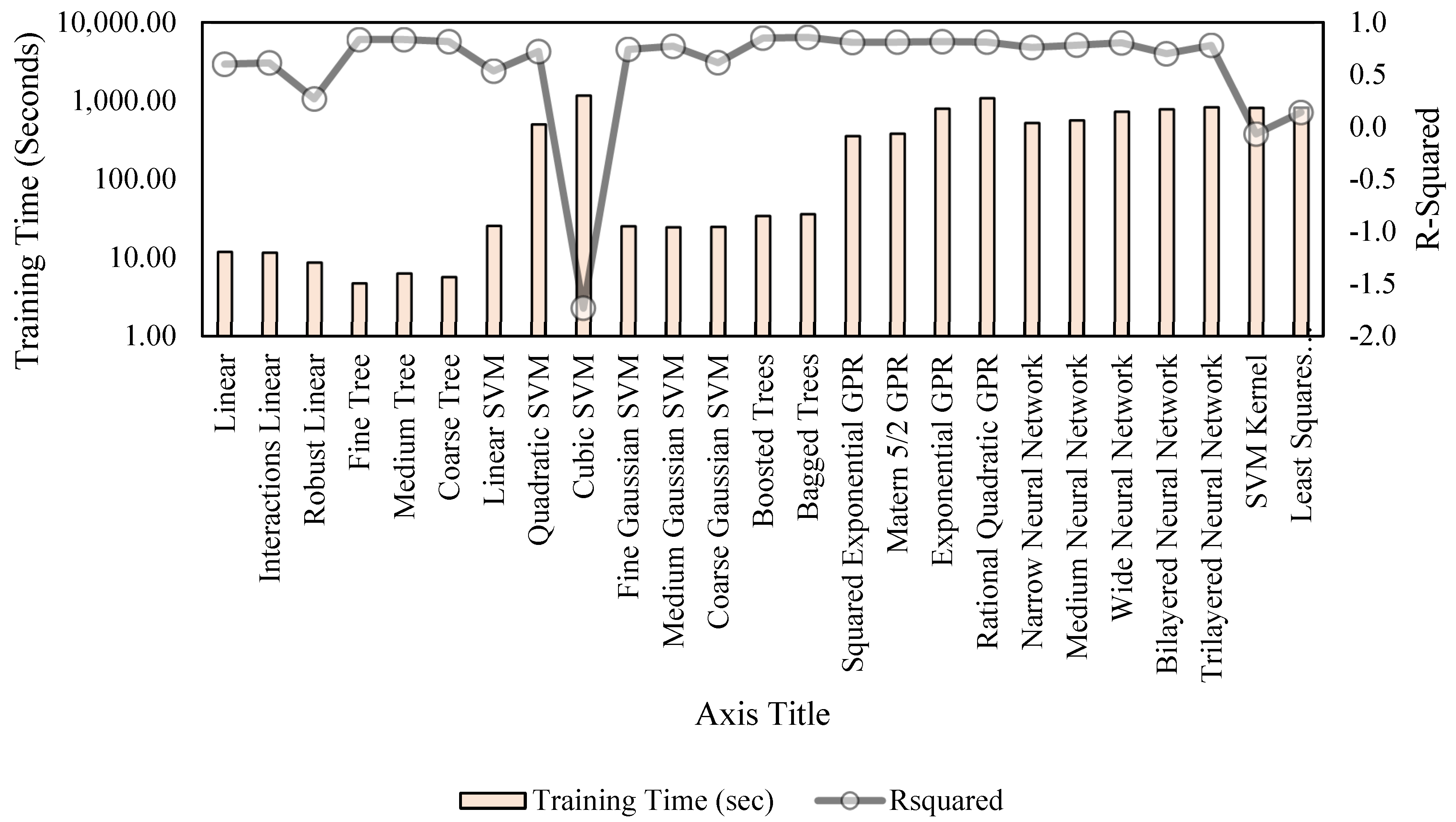

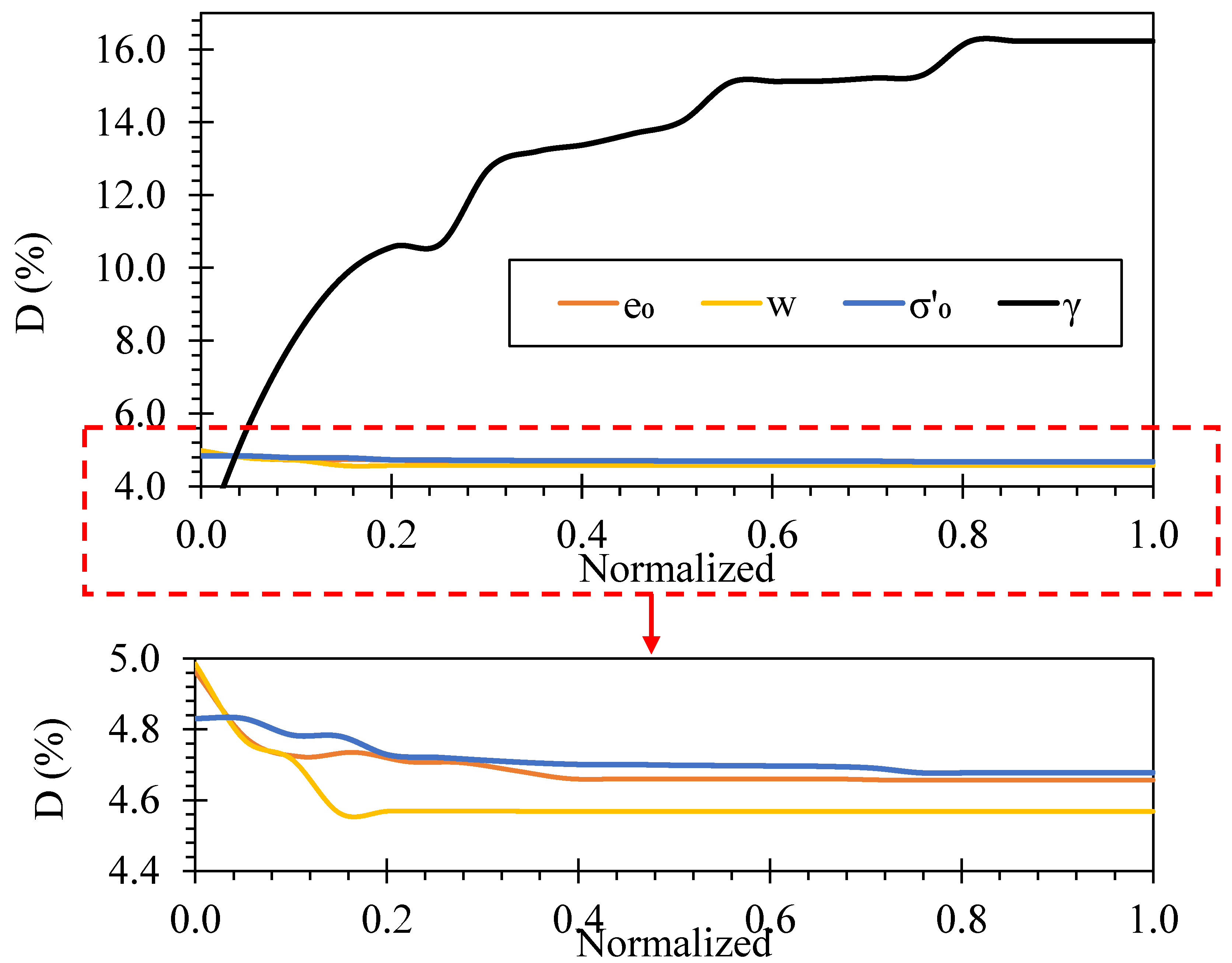

5.3.2. Partial Dependencies for Damping Models

- increases strongly and monotonically with , approaching a gentle saturation at higher normalized strains. This reflects widening hysteresis loops and greater energy dissipation under larger cyclic strains.

- A mild negative slope in suggests slightly lower under higher confinement; consistent with tighter contacts and reduced micro-slip.

- and both exhibit small, smooth variations (sub-percent changes) over the observed range, indicating secondary roles once and are controlled. These effects may be partially mediated by plasticity and liquidity index, which interact with the moisture state.

5.3.3. Computational Efficiency for Damping Models

5.4. Practical Implications and Recommendations

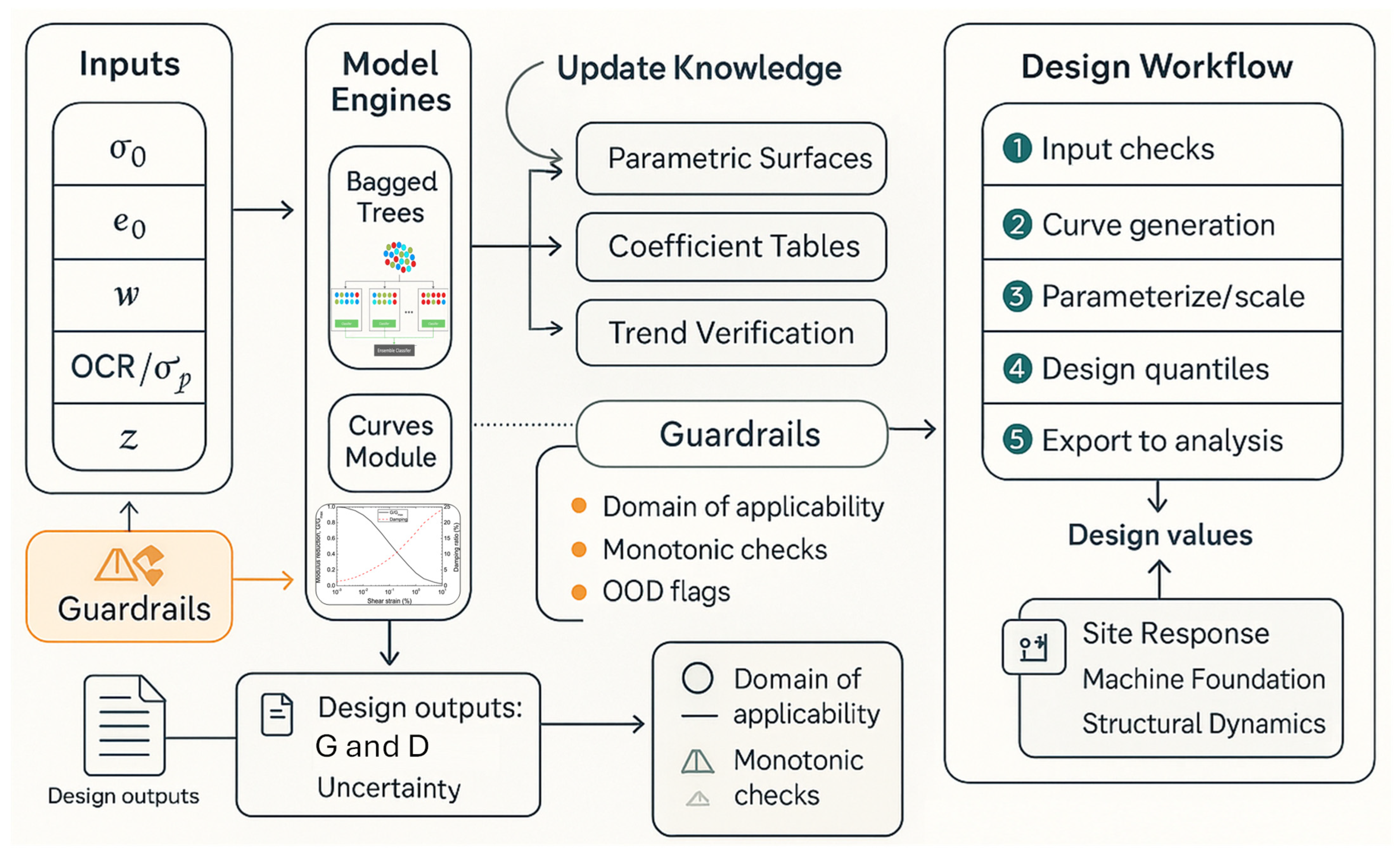

Using the Models to Advance Engineering Knowledge and Design Standards

- (A)

- Updating modulus-reduction and damping knowledge

- Mechanics-consistent trends, quantified through partial-dependence diagnostics, confirm expected monotonic relations: with , with and ; with , mild with . These trends can be published as parametric surfaces and , improving current charts that primarily index to plasticity or generic “soil type.”

- From ML curves to compact parameters by code adoption and transparency, fit the ML-generated and grids to standard closed-form families (e.g., hyperbolic/sigmoidal for ; smooth saturating forms for ). Publish coefficient tables as functions of , (or –), and . This preserves code familiarity while embedding multivariate dependence learned from data.

- (B)

- Code-ready modifiers for existing standards

- (C)

- Uncertainty-aware design values

- Stiffness: with chosen to align with code reliability targets;

- Damping: .Report , coverage diagnostics, and any conservatism factors so the selection is auditable.

- (D)

- A practical, code-compatible workflow

- Verify all predictors lie within the trained domain (Table 2 ranges) and compute the liquidity index where available.

- On a strain grid relevant to the analysis, compute and from the bagged-tree and GPR models; optionally segment by strain band (, and ).

- Fit to the code’s chosen curve forms or compute modifiers against baseline charts.

- Choose according to project criticality (e.g., standard vs. essential facilities) and extract quantile-based design values.

- Provide tabulated and pairs for site-response or machinery-vibration software, with a short model card (data ranges, CV metrics, and OOD flags).

- If a few local RC or BE/Vs data exist, perform a light calibration step (bias correction or monotone-constrained refit) and re-export the curves.

- (E)

- Knowledge gaps made measurable

5.5. Limitations and Future Studies

- Direct measures of soil fabric and microstructure, cementation/carbonate content, contact density/anisotropy, mineralogical fractions from X-ray diffraction (XRD), specific surface area and cation-exchange capacity (CEC), pore-size distribution and microcracks from scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP), and pore-fluid chemistry (salinity, pH) are absent and only indirectly proxied by LL/PI, water content, and USCS class. This omission likely explains part of the variance, especially in , and can inflate the apparent role of covarying site variables (e.g., depth, . Therefore, future studies should enrich datasets with these descriptors and quantify incremental value via ablation analysis and interpretable diagnostics (permutation importance, partial-dependence plots (PDPs), individual conditional expectation (ICE), and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP)), verifying trends consistent with mechanics.

- Degree of saturation, matric suction, loading frequency/strain-rate, and temperature are sparsely represented, restricting validity mainly to saturated, lab-controlled RC conditions within the tested bandwidths. Thus, future studies should incorporate partially saturated tests (reporting degree of saturation and suction), frequency/strain-rate sweeps, and temperature variation, and compare global models with strain-band models (, , ).

- Alternative histories and anisotropic consolidations (e.g., varying ) are unevenly sampled; global fits can blur strain-dependent behavior. Therefore, future studies should expand stress-path coverage and encode it explicitly, or adopt multi-task/curve models to learn and with monotonicity checks ( with ; with ; with ).

- Despite 2738 tests, some USCS classes are under-represented, and multiple specimens per site introduce correlation, making ordinary k-fold cross-validation optimistic for across-site transportability. Accordingly, future studies should apply grouped/site-wise, fully nested cross-validation with within-fold preprocessing, add site/campaign hold-outs, report dispersion across sites, and, where feasible, validate against independent field or small-strain lab measures (e.g., shear-wave velocity (Vs)-based , spectral analysis of surface waves (SASW), and bender-element (BE) tests).

- Univariate F-tests are linear and do not capture interactions such as or ; one-hot USCS encoding is coarse. Therefore, future studies should evaluate physics-motivated transforms and composites (e.g., ; normalization by mean effective stress ; liquidity index , include interaction features, and address heteroscedasticity with variance-stabilizing targets.

- Only Gaussian process regression yields native intervals; interval calibration and shift detection were not assessed systematically. Thus, future studies should implement quantile regression forests/boosting and conformal prediction to obtain calibrated coverage reporting prediction-interval coverage probability (PICP), mean prediction-interval width (MPIW), and continuous ranked probability score (CRPS) alongside simple range guards and out-of-distribution (OOD) detectors based on distance-to-training-manifold.

- Tree-boosting variants common for tabular data (XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost) and probabilistic forests were not included; monotonic constraints aligned with mechanics were not enforced. Therefore, future studies should benchmark these families.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Terzaghi, K.; Peck, R.B.; Mesri, G. Soil Mechanics in Engineering Practice; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Seed, H.B.; Idriss, I.M. Soil moduli and damping factors for dynamic response analyses. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1970, 1, 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D4015-15; Standard Test Method for Modulus and Damping of Soils by the Resonant-Column Method. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- Phoon, K.K.; Kulhawy, F.H. Characterization of geotechnical variability. Can. Geotech. J. 1999, 36, 612–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, S.L. Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gazetas, G. Formulas and charts for impedances of surface and embedded foundations. J. Geotech. Eng. 1991, 117, 1363–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.P. Foundation Vibration Analysis Using Simple Physical Models; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, A.; Demir, S.; Sahin, E.K. Machine Learning Based Prediction of Peak Floor Acceleration in Low- to Mid-Rise RC Buildings Using Ground Motion Intensity Measures. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 2025, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Kishida, T. Shear modulus reduction and damping ratio curves for earth core materials of dams. Can. Geotech. J. 2019, 56, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vucetic, M.; Dobry, R. Effect of soil plasticity on cyclic response. J. Geotech. Eng. 1991, 117, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darendeli, M.B. Development of a New Family of Normalized Modulus Reduction and Material Damping Curves for Cohesive Soils. Ph.D. Dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi, F.; Jankowski, R. Machine learning-based prediction of seismic limit-state capacity of steel moment-resisting frames considering soil-structure interaction. Comput. Struct. 2022, 274, 106886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, R.; Kim, D. Shear wave velocity and soil liquefaction. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2009, 135, 956–967. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.S.; Krishna, A.M.; Dey, A. Parameters influencing dynamic soil properties: A review treatise. In Proceedings of the National Conference on Recent Advances in Civil Engineering, Kalavakkam, India, 15–16 November 2013; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kallioglou, P.; Tika, T.; Pitilakis, K. Shear modulus and damping ratio of cohesive soils. J. Earthq. Eng. 2008, 12, 879–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Zhang, F.; Feng, D.; Tang, K.; Feng, X. Dynamic shear modulus and damping ratio of thawed saturated clay under long-term cyclic loading. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2018, 145, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Andrus, R.D.; Juang, C.H. Normalized shear modulus and material damping ratio relationships. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2005, 131, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallioglou, P.; Tika, T.; Koninis, G.; Papadopoulos, S.; Pitilakis, K. Shear modulus and damping ratio of organic soils. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2009, 27, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudiosi, I.; Romagnoli, G.; Albarello, D.; Fortunato, C.; Imprescia, P.; Stigliano, F.; Moscatelli, M. Shear modulus reduction and damping ratios curves joined with engineering geological units in Italy. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, S.R.; Sharma, M.L. Applications of artificial intelligence in geotechnical engineering. In Handbook of Applications of Machine Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 381–398. [Google Scholar]

- Pirnia, P.; Duhaime, F.; Manashti, J. Machine learning algorithms for applications in geotechnical engineering. In Proceedings of the GeoEdmonton, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 23–26 September 2018; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Ding, X. Application of deep learning algorithms in geotechnical engineering: A short critical review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2021, 54, 5633–5673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, N.; Prasad, H.D.; Jain, A. Prediction of geotechnical parameters using machine learning techniques. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 125, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Yin, Z.-Y.; Jin, Y.-F. Machine learning-based modelling of soil properties for geotechnical design: Review, tool development and comparison. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29, 1229–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghbani, A.; Choudhury, T.; Costa, S.; Reiner, J. Application of artificial intelligence in geotechnical engineering: A state-of-the-art review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2022, 228, 103991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoon, K.K.; Zhang, W. Future of machine learning in geotechnics. Georisk Assess. Manag. Risk Eng. Syst. Geohazards 2023, 17, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Gu, X.; Tang, L.; Yin, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhang, Y. Application of machine learning, deep learning and optimization algorithms in geoengineering and geoscience: Comprehensive review and future challenge. Gondwana Res. 2022, 109, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.G.; Zeng, X.; Rose, J.G. Shear modulus and damping ratio of rubber-modified asphalt mixes and unsaturated subgrade soils. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2002, 14, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Chao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, H. The application of support vector machine in geotechnical engineering. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018; Volume 189, p. 022055. [Google Scholar]

- Loh, W.Y. Classification and regression trees. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2011, 1, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. An intuitive tutorial to Gaussian processes regression. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2023, 25, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Xiong, J.; Zhong, J.; Leatham, K. Gaussian process regression method for classification for high-dimensional data with limited samples. In Proceedings of the 2018 Eighth International Conference on Information Science and Technology (ICIST), Seville, Spain, 30 June–6 July 2018; pp. 358–363. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Ren, J. Bagging for Gaussian process regression. Neurocomputing 2009, 72, 1605–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Tuong, D.; Seeger, M.; Peters, J. Model learning with local gaussian process regression. Adv. Robot. 2009, 23, 2015–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facciorusso, J. An archive of data from resonant column and cyclic torsional shear tests performed on Italian clays. Earthq. Spectra 2021, 37, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.-S.; Thedja, J.P.P. Metaheuristic optimization within machine learning-based classification system for early warnings related to geotechnical problems. Autom. Constr. 2016, 68, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbueri, J.C. Use of joint supervised machine learning algorithms in assessing the geotechnical peculiarities of erodible tropical soils from southeastern Nigeria. Geomech. Geoengin. 2023, 18, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, T.; Qiu, T. Machine learning with monotonic constraint for geotechnical engineering applications: An example of slope stability prediction. Acta Geotech. 2023, 19, 3863–3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H. A reduced order model based on machine learning for numerical analysis: An application to geomechanics. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2021, 100, 104194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoozi, A.A.; Firoozi, A.A. Application of Machine Learning in Geotechnical Engineering for Risk Assessment. In Machine Learning and Data Mining Annual Volume 2023; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.-M.; Zhang, J.-Z.; Huang, H.-W.; Qi, C.-C.; Chang, C.-Y. Machine learning-based prediction of soil compression modulus with application of 1D settlement. J. Zhejiang Univ. A (Appl. Phys. Eng.) 2020, 21, 430–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Huang, J.; Zeng, C.; Huang, S.; Burton, G.J. A generic framework for geotechnical subsurface modeling with machine learning. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2022, 14, 1366–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Watanachaturaporn, P.; Varshney, P.; Arora, M. Decision tree regression for soft classification of remote sensing data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 97, 322–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsimas, D.; Dunn, J.; Paschalidis, A. Regression and classification using optimal decision trees. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE MIT Undergraduate Research Technology Conference (URTC), Cambridge, MA, USA, 3–5 November 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri, P.; Lo, W.D.; Loh, W.Y.; Yang, C.C. Generalized regression trees. Stat. Sin. 1995, 5, 641–666. [Google Scholar]

- Jakkula, V. Tutorial on Support Vector Machine (svm); School of EECS, Washington State University: Pullman, WA, USA, 2006; Volume 37, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Mavroforakis, M.; Theodoridis, S. A geometric approach to support vector machine (SVM) classification. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2006, 17, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basheer, I.A.; Najjar, Y.M. Modeling cyclic constitutive behavior by neural networks: Theoretical and real data. In Proceedings of the 12th Engineering Mechanics Conference, La Jolla, CA, USA, 17–20 May 1998; pp. 952–955. [Google Scholar]

| Data Type | Data Attribute | Description | Brief Definition | Number/ Categorical |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inputs | Depth of sample (m) | Depth below ground level | Number | |

| Specific gravity | Relative density of solids to water | Number | ||

| Soil density (Mg/m3) | Bulk (wet) density of soil | Number | ||

| Liquid limit (%) | Moisture content at plastic–liquid transition | Number | ||

| Plasticity index (%) | Moisture range for plastic behavior () | Number | ||

| Water content (%) | Mass of water over dry soil mass | Number | ||

| USCS-CH | USCS classification code | USCS classifications for clay, silt, or sand types | Categorical | |

| USCS-CL | USCS classification code | Categorical | ||

| USCS-MH-OH | USCS classification code | Categorical | ||

| USCS-SC | USCS classification code | Categorical | ||

| USCS-OH | USCS classification code | Categorical | ||

| USCS-ML-OL | USCS classification code | Categorical | ||

| USCS-CL-CH | USCS classification code | Categorical | ||

| USCS-CL-ML | USCS classification code | Categorical | ||

| e0 | Initial void ratio | Voids-to-solids ratio at start | Number | |

| σ′p | Preconsolidation pressure (kPa) | Maximum past effective vertical stress | Number | |

| OCR* | Overconsolidation ratio | Number | ||

| σ′0 | Test confining pressure (kPa) | Applied an effective confining pressure in the test | Number | |

| ϒl | Elastic threshold (%) | Strain at the onset of elastic behavior | Number | |

| ϒv | Volumetric threshold (%) | Strain at the onset of significant volumetric change | Number | |

| ϒ | Shear strain amplitude induced during RC or CTS test (%) | Imposed shear strain during RC/CTS | Number | |

| Output | G | Shear modulus measured during RC or CTS test (kPa) | Stiffness measured in RC/CTS (small–medium strain) | Number |

| D | Damping ratio measured during RC or CTS test (%) | Hysteretic energy dissipation measured in RC/CTS | Number |

| Median | Mean | Std. Deviation | Range | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| z [m] | 11.87 | 15.01 | 11.03 | 48.30 | 1.45 | 49.75 |

| GS [-] | 2.70 | 2.70 | 0.06 | 0.55 | 2.32 | 2.87 |

| ρ [Mg/m3] | 2.02 | 2.00 | 0.14 | 0.90 | 1.30 | 2.19 |

| LL [%] | 45.00 | 48.42 | 18.31 | 140.00 | 24.00 | 164.00 |

| PI [%] | 24.00 | 25.33 | 11.39 | 80.00 | 4.00 | 84.00 |

| w [%] | 26.06 | 28.32 | 13.42 | 113.40 | 16.40 | 129.80 |

| e0 [-] | 0.63 | 0.68 | 0.29 | 2.06 | 0.40 | 2.46 |

| σ′p [kPa] | 310.00 | 310.99 | 187.57 | 870.00 | 30.00 | 900.00 |

| OCR* [-] | 2.50 | 2.99 | 2.26 | 8.40 | 1.00 | 9.40 |

| σ′0 [kPa] | 200.00 | 227.56 | 125.72 | 490.00 | 50.00 | 540.00 |

| ϒl [%] | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 4.5 × 10−4 | 0.02 |

| ϒv [%] | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.34 | 0.01 | 0.35 |

| ϒ [%] | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.63 | 1.9 × 10−5 | 0.63 |

| G [MPa] | 70.42 | 84.22 | 54.79 | 288.49 | 3.54 | 292.02 |

| D (%) | 3.28 | 4.80 | 3.81 | 21.67 | 0.92 | 22.59 |

| Model Type | Specifications | RMSE | MSE | R-Squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Regression | Linear | 30,612.70 | 937,137,444.50 | 0.69 |

| Interactions Linear | 20,238.44 | 409,594,453.80 | 0.86 | |

| Robust Linear | 32,885.61 | 1,081,463,145.00 | 0.64 | |

| Regression Tree | Fine Tree | 7292.71 | 53,183,572.95 | 0.98 |

| Medium Tree | 9031.67 | 81,571,082.40 | 0.97 | |

| Coarse Tree | 15,359.48 | 235,913,499.00 | 0.92 | |

| SVM | Linear SVM | 31,892.97 | 1,017,161,800.00 | 0.66 |

| Quadratic SVM | 18,001.66 | 324,059,642.90 | 0.89 | |

| Cubic SVM | 16,174.61 | 261,617,886.70 | 0.91 | |

| Fine Gaussian SVM | 10,027.04 | 100,541,590.30 | 0.97 | |

| Medium Gaussian SVM | 16,193.21 | 262,220,042.70 | 0.91 | |

| Coarse Gaussian SVM | 28,942.11 | 837,645,622.20 | 0.72 | |

| Ensemble Tree | Boosted Trees | 11,600.99 | 134,582,891.80 | 0.96 |

| Bagged Trees | 7208.51 | 51,962,677.32 | 0.98 | |

| Gaussian Process Regression | Squared Exponential GPR | 11,252.71 | 126,623,457.00 | 0.96 |

| Matern 5/2 GPR | 8226.03 | 67,667,600.97 | 0.98 | |

| Exponential GPR | 2263.03 | 5,121,318.41 | 0.99 | |

| Rational Quadratic GPR | 2424.73 | 5,879,291.41 | 0.99 | |

| Neural Network | Narrow Neural Network | 9994.03 | 99,880,577.32 | 0.97 |

| Medium Neural Network | 6918.27 | 47,862,394.71 | 0.98 | |

| Wide Neural Network | 3935.11 | 15,485,057.04 | 0.99 | |

| Bilayered Neural Network | 7940.93 | 63,058,396.10 | 0.98 | |

| Trilayered Neural Network | 8127.17 | 66,050,865.96 | 0.98 | |

| Kernel | SVM Kernel | 56,215.57 | 3,160,190,262.00 | −0.05 |

| Least Squares Regression Kernel | 30,263.23 | 915,863,154.30 | 0.70 |

| Model Type | Specifications | RMSE | MSE | R-Squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Regression | Linear | 2.45 | 5.99 | 0.60 |

| Interactions Linear | 2.41 | 5.79 | 0.61 | |

| Robust Linear | 3.31 | 10.94 | 0.27 | |

| Regression Tree | Fine Tree | 1.57 | 2.47 | 0.83 |

| Medium Tree | 1.57 | 2.47 | 0.83 | |

| Coarse Tree | 1.66 | 2.75 | 0.82 | |

| SVM | Linear SVM | 2.64 | 6.96 | 0.53 |

| Quadratic SVM | 2.04 | 4.17 | 0.72 | |

| Cubic SVM | 6.39 | 40.83 | −1.73 | |

| Fine Gaussian SVM | 1.97 | 3.86 | 0.74 | |

| Medium Gaussian SVM | 1.85 | 3.42 | 0.77 | |

| Coarse Gaussian SVM | 2.40 | 5.77 | 0.61 | |

| Ensemble Tree | Boosted Trees | 1.50 | 2.26 | 0.85 |

| Bagged Trees | 1.46 | 2.14 | 0.86 | |

| Gaussian Process Regression | Squared Exponential GPR | 1.70 | 2.88 | 0.81 |

| Matern 5/2 GPR | 1.68 | 2.83 | 0.81 | |

| Exponential GPR | 1.66 | 2.75 | 0.82 | |

| Rational Quadratic GPR | 1.68 | 2.83 | 0.81 | |

| Neural Network | Narrow Neural Network | 1.90 | 3.60 | 0.76 |

| Medium Neural Network | 1.81 | 3.26 | 0.78 | |

| Wide Neural Network | 1.71 | 2.93 | 0.80 | |

| Bilayered Neural Network | 2.12 | 4.49 | 0.70 | |

| Trilayered Neural Network | 1.81 | 3.28 | 0.78 | |

| Kernel | SVM Kernel | 3.99 | 15.95 | −0.07 |

| Least Squares Regression Kernel | 3.59 | 12.87 | 0.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almarzooqi, A.; Arab, M.G.; Omar, M.; Alotaibi, E. Benchmarking Conventional Machine Learning Models for Dynamic Soil Property Prediction. Buildings 2025, 15, 4188. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224188

Almarzooqi A, Arab MG, Omar M, Alotaibi E. Benchmarking Conventional Machine Learning Models for Dynamic Soil Property Prediction. Buildings. 2025; 15(22):4188. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224188

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmarzooqi, Abdalla, Mohamed G. Arab, Maher Omar, and Emran Alotaibi. 2025. "Benchmarking Conventional Machine Learning Models for Dynamic Soil Property Prediction" Buildings 15, no. 22: 4188. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224188

APA StyleAlmarzooqi, A., Arab, M. G., Omar, M., & Alotaibi, E. (2025). Benchmarking Conventional Machine Learning Models for Dynamic Soil Property Prediction. Buildings, 15(22), 4188. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224188