1. Introduction

In recent years, sustainable principles and human-centered design have continuously reshaped the trajectory of large-scale public architecture [

1,

2]. Today, the selection of building materials transcends mere structural and cost considerations, evolving into a medium capable of evoking user emotions, organizing spatial behavior, and ultimately shaping distinctive experiences [

3,

4]. Wood, valued for its renewable and low-carbon attributes alongside its perceptible warmth and texture, is increasingly becoming a preferred choice for public cultural facilities [

5]. Compared to high-energy-consumption, technology-oriented solutions, wood exerts a more direct influence on users’ emotions and behaviors through its combined visual and tactile effects, thereby impacting place evaluation [

6,

7,

8].

Among various types of public buildings, cultural spaces are particularly sensitive to materials [

9,

10]. Compared to transportation or commercial facilities, cultural venues typically involve longer dwell times, more focused attention, and stronger emotional engagement [

11,

12]. The concert hall stands as a representative setting: performance viewing demands sustained attention and emotional engagement, where spatial, visual, and tactile cues are readily captured by audiences and integrated into an overall experience of perceptual resilience, musical resonance, and satisfaction [

13,

14]. Thus, concert halls provide an ideal setting for examining the holistic experiential value of wood design, allowing us to focus on how material sensations influence user satisfaction through psychological processes [

15,

16].

Although existing research has explored the value of wood from perspectives such as aesthetic expression and structural performance, the micro-mechanisms linking design cues to user psychology and satisfaction remain underdeveloped [

17]. First, many studies remain confined to descriptions of materials and forms, lacking user-centered depictions of experiential pathways and failing to clearly explain how perceptions of wooden design translate into satisfaction. Second, while perceived resilience and musical resonance serve as crucial psychological variables linking design and experience, they are rarely examined within a unified framework. Their respective roles and potential sequential relationships remain unclear. Third, although theories of affective design can explain architectural experiences, their organic integration within the specific context of wooden concert halls and large-sample structural equation modeling validation remains absent [

4].

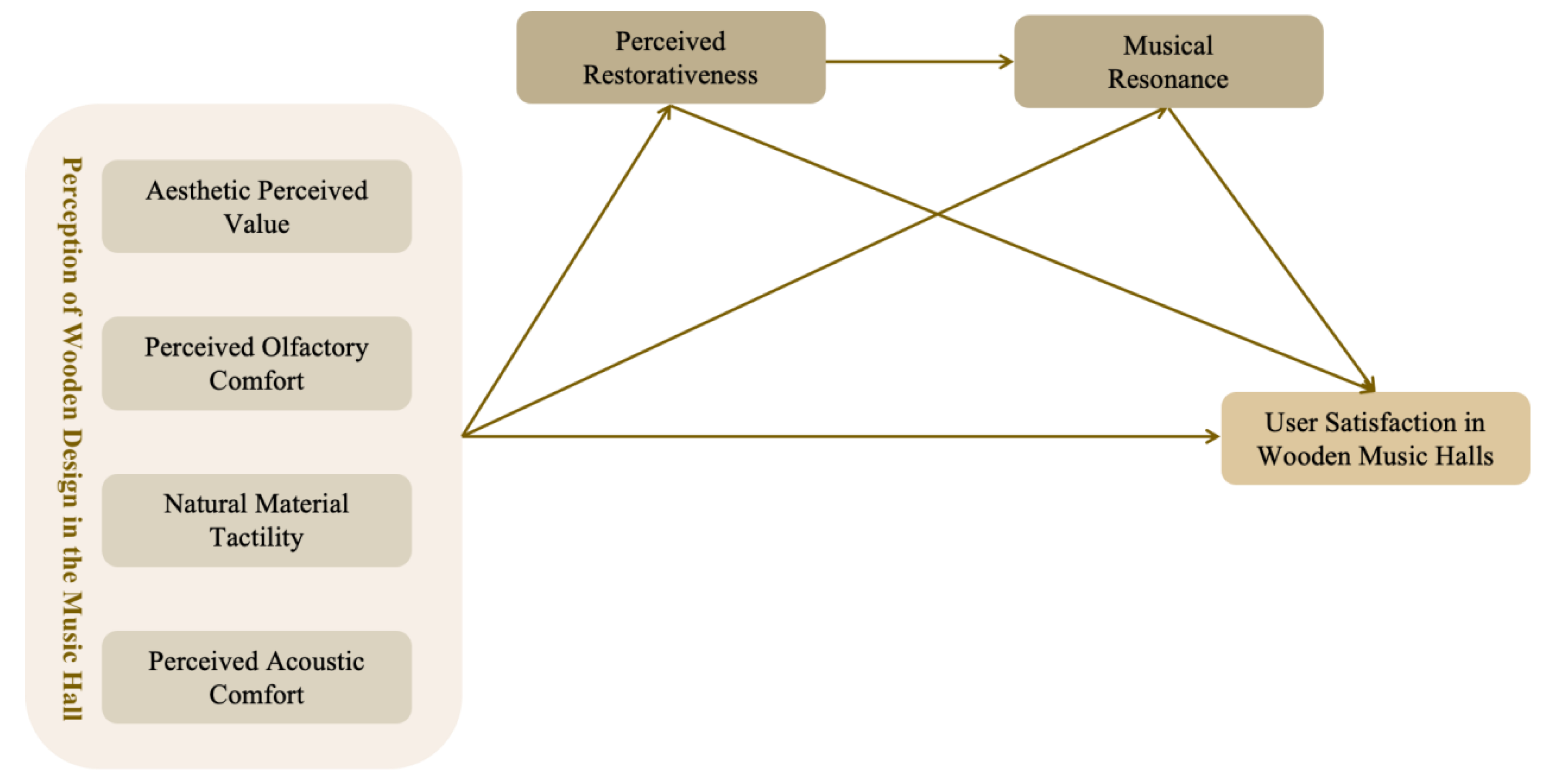

Based on this, this study constructs and tests a conceptual model centered on perceptions of wooden design, perceived restorativeness, musical resonance, and user satisfaction, using 965 actual offline users of wooden concert halls as the research subjects. Theoretically, the study explores how visual and tactile cues of wood induce a sense of restoration and enhance musical resonance, ultimately influencing overall satisfaction. Methodologically, the study employs covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) to model and test multi-path relationships, leveraging a large-sample questionnaire to enhance inferential robustness. Within this framework, three research questions are proposed for validation:

- (1)

Does a stable positive association exist between the perception of wooden design and user satisfaction?

- (2)

Do perceived restorativeness and musical resonance, respectively, mediate this relationship?

- (3)

Do these two factors form a chained relationship, thereby refining the mechanism pathways through which visual and tactile cues lead to perceived restoration and emotional resonance?

This study contributes in three dimensions. First, its theoretical contribution lies in supplementing evidence on the psychological mechanisms through which the perception of wooden design influences user satisfaction from a user perspective, proposing and testing an explanatory framework centered on perceived restorativeness and musical resonance within the concert hall context. Second, the methodological contribution lies in employing CB-SEM to depict multiple pathways and relative effects, providing a discernible modeling strategy for the causal chain linking material perception to satisfaction. Third, the practical contribution proposes actionable guidelines for spatial organization, material selection, and multisensory design in wooden concert halls, enabling designs that both respond to sustainability goals and enhance user experience quality. These findings also offer reference points for green evaluation criteria and user experience optimization in cultural venues.

3. Research Design

3.1. Participants

The study subjects comprised actual visitors and audience members of the wooden concert hall. On-site intercept convenience sampling was employed in combination with stratified quota control to ensure the sample was representative in terms of gender, age, and attendance frequency. Inclusion criteria: aged 18 or older, physically present at the target venue on the day of data collection, spending at least 30 min in the main wooden space, having visited the concert hall at least once in the past 12 months, not being an employee or volunteer, and capable of independently completing the questionnaire. Exclusion criteria: respondents under the influence of alcohol or drugs, individuals visibly rushed and unable to answer accurately, and duplicate submissions from the same device or contact method. The specific information of the surveyed venues is shown in

Table 1. For more detailed demographic information, please refer to

Table 2.

Time slots were set for weekday evening performances and weekend daytime/evening performances to encompass diverse performance types and audience structures. On-site intercept points were proportionally distributed across seating sections, with flexible quotas applied to gender, age, and first-time/repeat visitor ratios to prevent sample skew toward any single demographic. All participants received brief informed consent and written agreement prior to participation, explicitly confirming anonymity, academic-use-only purpose, and the right to withdraw at any time. The study adhered to data minimization and purpose limitation principles; personal contact information was used solely for duplicate prevention and separate storage of questionnaire responses. To ensure measurement validity, the questionnaire underwent a small-scale pretest (

n ≈ 30) using convenience samples from similar venues prior to formal distribution. Based on feedback, wording ambiguities and scale item order were refined, and reliability checks were completed. Pre-test data were excluded from the final results. The formal survey invited approximately 1120 participants, with 1032 questionnaires collected on-site. Among these, 67 were excluded due to failed attention detection, abnormal response duration, homogeneous responses, or duplicate device IDs. This yielded 965 valid samples for subsequent CB-SEM analysis. Detailed demographic information is presented in

Table 1. The data from the seven halls were aggregated for the primary analysis because the study’s objective was to test the general psychological mechanisms (the mediation model) linking wooden design perception to satisfaction, which we hypothesized to be universal across different hall designs. A multi-group analysis was not performed as the sample size per individual hall was insufficient for robust comparative structural equation modeling.

3.2. Variable Measurement

This study measured four latent variables: Wooden Design Perception (WDP), Perceived Restorativeness (PR), Musical Resonance (MR), and User Satisfaction (US). All items were adapted from established scales through localization and optimized with context-specific phrasing tailored to the concert hall setting. Cross-linguistic equivalence was achieved through a “translation-back-translation” procedure. The research team conducted item-by-item semantic comparisons and obtained reviews from three architecture experts regarding semantic clarity, cultural adaptation, and contextual relevance. Subsequently, wording and item order were refined through cognitive interviews and pre-testing.

The Wood Design Perception (WDP) scale measures participants’ comprehensive perception of wooden elements in concert halls across visual and tactile dimensions. It primarily employs Xiao et al.’s Wood Design Perception scale [

18], comprising four dimensions: Aesthetic Perceived Value, Perceived Natural Connection, Perceived Olfactory Comfort, and Natural Material Tactility. Due to differing research contexts, we replaced the Perceived Natural Connection dimension with Perceived Acoustic Comfort, as suggested by the original authors in their “Limitations and Future Research” section. For all other sections, adaptations were limited to context-specific replacements. At the item level, this study maintained the original scale structure and semantics, substituting only the applicable subjects and settings to the concert hall context. For example:—The original statement “The appearance of wood makes the space more aesthetically pleasing” in the Aesthetic Perceived Value dimension was contextualized as “The appearance of wood in a concert hall makes the space more aesthetically pleasing”; The Perceived Olfactory Comfort dimension, such as “The scent of wood makes me feel pleasant and relaxed,” remained unchanged in this study, with only “place” replaced by “concert hall”; the Natural Material Tactility dimension, such as “The tactile sensation of wooden surfaces makes me feel warm and comfortable,” was correspondingly rewritten as “The tactile sensation of wooden surfaces in a concert hall makes me feel warm and comfortable.” For the revised Perceived Acoustic Comfort dimension, we operationalized it based on the original author’s suggestions regarding acoustic environment perceptions. Example items include: “Wooden elements enhance my auditory comfort here,” “I feel wooden materials improve the clarity of performance sounds,” and “I am less distracted by ambient sounds in this space.”

Regarding mediator variable measurement, this study continues to utilize established scales from prior research. For Perceived Restorativeness, the Chinese version of the Environmental Restorativeness Perception Scale (ERPS), revised by Li et al., was employed, comprising four dimensions: Being-Away, Extent, Fascination, and Compatibility. This scale has been validated with Chinese samples for direct application in user restorativeness assessment [

43]. Items include: “Such places allow me to escape from troubles,” “Here I notice many interesting things.” For the music resonance scale, this study referenced Guo et al.’s Emotional Resonance Scale and adapted it based on the core meaning of the “Musical Emotional Resonance” subscale from the Goldsmiths Musical Sophistication Index (Gold-MSI). Examples include: “I can clearly feel the emotions this music intends to express,” and “The music evokes strong, personal associations for me.”

For measuring the dependent variable of user satisfaction, we focused on overall audience satisfaction using scales from Attkisson and Greenfield and Zhang et al. [

44,

45]. Specific items included: “I felt great pleasure and enjoyment during this concert hall experience,” and “I believe the wooden concert hall provides us with a unique and distinctive listening experience.”

For clarity and to provide a systematic overview of the measurement instruments,

Table 3 summarizes the sources, adaptations, and sample items for all latent variables and their dimensions.

3.3. Questionnaire Distribution Process

The survey was conducted in two time slots: 30 min before the performance began and 20 min after it ended, to minimize emotional bias induced by a single context. Each intercept point was staffed by uniformly trained interviewers who first conducted eligibility screening and obtained informed consent. Participants were then guided to scan a QR code or complete a paper questionnaire based on their preference. The questionnaire employed a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly Agree). To mitigate common method variance and order effects, the questionnaire was segmented by context and psychological pathways with item randomization: Part One collected behavioral and contextual control variables (e.g., attendance frequency in the past 12 months, duration of stay on the day, seating location); Part Two presented items assessing perceptions of wooden design (including 1–2 reverse-scored items and attention checks, e.g., “Please select ‘Agree’ for this question”); Part Three cross-presented items on Perceived Restorativeness and Musical Resonance; Part Four measured user satisfaction and overall evaluation; finally, basic demographic information was collected, with demographic data and responses stored separately under random codes. The system sets thresholds for minimum reasonable response time, short-term repeat interception for the same devices, and rules for identifying homogeneous responses. Investigators provided only operational assistance without guiding item meanings. The questionnaire’s opening page explicitly instructs participants to evaluate “their actual experience within the wooden space during this performance,” with surveyors verifying their presence in the primary wooden area. At the end of each day, raw data is exported and undergoes preliminary checks on-site (missing values, response duration, attention question pass rate). Weekly secondary cleaning and deduplication are performed, preliminary reliability metrics for key scales are calculated, and a sample structure comparison table is generated. This data is calibrated against the venue’s daily visitor flow and seating area distribution to ensure balanced coverage across different time periods and seating zones. The final output is a clean dataset suitable for structural equation modeling.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

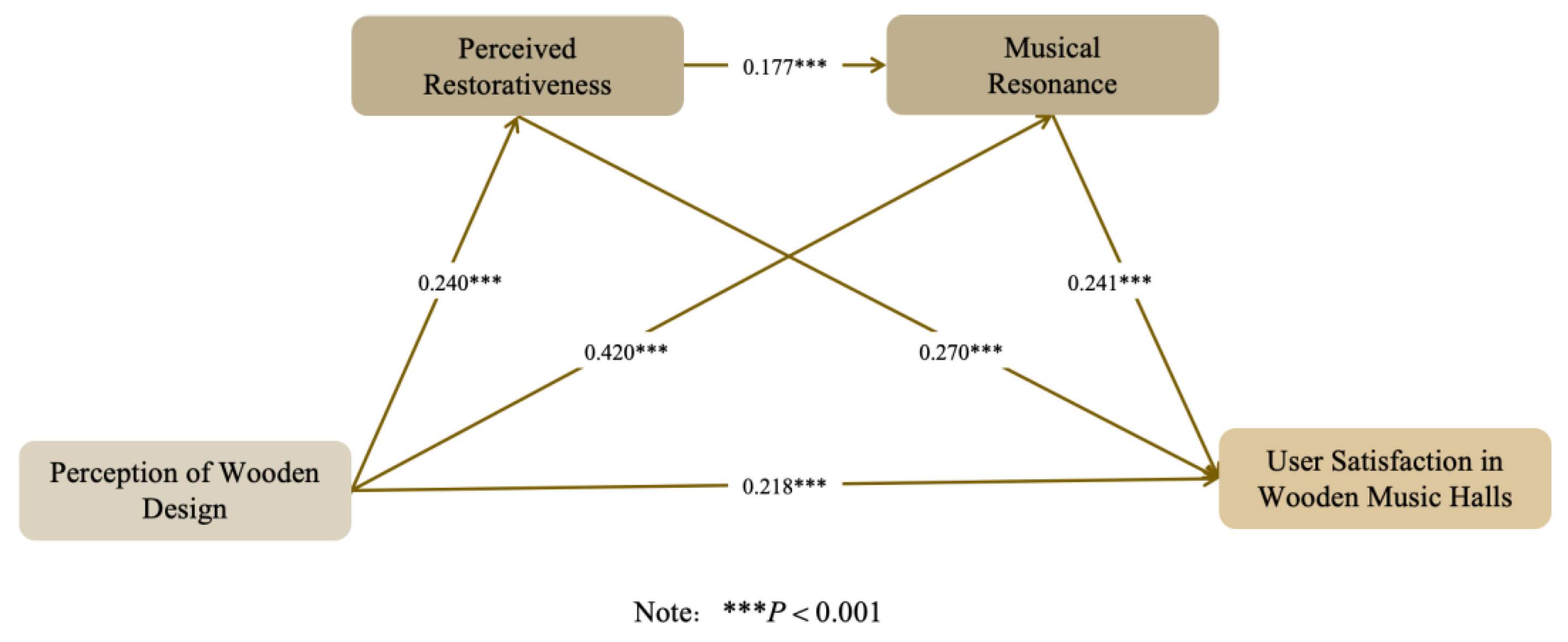

The results provide strong support for our hypothesized model. Statistical analysis confirms a significant direct effect of Wooden Design Perception (PWD) on User Satisfaction (US) (β = 0.268, p < 0.001), thereby validating Hypothesis 1. More importantly, bootstrap mediation tests establish the independent mediating roles of Perceived Restorativeness (PR) (Effect = 0.067, 95% CI [0.046, 0.089]) and Musical Resonance (MR) (Effect = 0.120, 95% CI [0.085, 0.156]), supporting Hypotheses 2 and 3, respectively. Crucially, the analysis confirms the existence of a sequential chained mediation pathway, PWD → PR → MR → US (Effect = 0.011, 95% CI [0.006, 0.018]), which substantiates Hypothesis 4. This empirical pattern demonstrates that the influence of wooden design on satisfaction is not merely direct but operates through a more complex psychological mechanism wherein the environment first induces a restorative state, which in turn facilitates a deeper connection with the music, ultimately enhancing the overall evaluation.

This study begins with the perception of multisensory wooden design, verifying its positive impact on concert hall user satisfaction. It demonstrates that perceived restorativeness and musical resonance each play a mediating role, following a sequential logic of” first restoration, then resonance”. Compared to attributing satisfaction solely to comfort, this pathway emphasizes a two-stage processing of resources and emotions. First, it reduces mental noise, restores attentional resources, and stabilizes the emotional baseline. Subsequently, it facilitates emotional and meaningful engagement with musical content, ultimately elevating overall evaluation. Furthermore, we propose only one contextually plausible dominant pathway without denying the possibility of parallel routes. Simultaneously, positioning the perception of wooden design as a multisensory composite construct within performance-oriented spatial contexts highlights the systemic role of non-visual cues like acoustics, olfactory, and tactile elements. Conceptually, perceived restorativeness and resonance are distinguishable yet related processes, potentially sharing common variance in attention capture and emotional homeostasis, with strong separation not necessarily required. Contextually, this sequential mechanism is more applicable to performance experiences demanding sustained focus and fine processing; In more social, relaxed settings, restorative needs may diminish while program attributes and group dynamics amplify resonance drivers.

Practical recommendations prioritize acoustic necessity + multisensory enhancement, organizing touchpoints and details in a “restorative first, resonant later” sequence that prioritizes: Maintain environmental coherence through material order and consistent lighting/color to reduce cognitive load; control wood fragrance and tactile sensations within comfortable ranges to avoid adverse reactions triggered by threshold effects (overpowering scents, glare, or excessive sound absorption). Operationally, minimize tension and distraction through noise management, wayfinding, and controlled entry rhythms. During performances, reduce interruptions and enhance presence to facilitate a smooth transition from “recovery” to “resonance”. Different musical genres and hall dimensions warrant tailored acoustic solutions. For instance, chamber music prioritizes clarity and intimacy, while symphonic performances emphasize balance between spatial immersion and early reflections.

5.2. Comparative Research

The findings of this study engage directly with the literature in both architectural environmental psychology and concert hall acoustics. By integrating perspectives from these two fields, it reveals previously unexplored core mechanisms.

Within environmental psychology, as exemplified by the research of Mamić and Domljan [

47], a consensus has emerged that wood’s visual and tactile properties effectively reduce users’ physiological stress levels and enhance positive emotions, primarily by facilitating attentional restoration and stress reduction [

48]. In the field of concert hall acoustics, scholars have discovered that the visual environment is a key factor influencing listeners’ subjective evaluation of sound quality. Even when objective acoustic parameters remain unchanged, aesthetically pleasing visual design can positively modulate listeners’ auditory perception [

49,

50,

51]. In other words, we know that wood can make people feel better, but we do not understand how this so-called better feeling translates into deep resonance within a concert hall.

However, existing research has failed to elucidate the complete psychological mechanism underlying user experience formation within the complex context of wooden concert halls. Environmental psychology studies emphasize the universal health benefits of materials but neglect to extend their analysis to higher-order outcomes like artistic emotional experiences. Meanwhile, psychoacoustic research focuses on audiovisual sensory interactions while relatively overlooking the critical role played by environment-induced psychological states, such as restorative effects. This study bridges this fragmented perspective by integrating affective design and immersion theory. Findings reveal that the wooden design first shapes users’ perceived restorativeness. This restorative psychological state is not an endpoint but rather the essential psychological preparation enabling users to fully immerse themselves and ultimately achieve deep emotional resonance with the music. Thus, the core contribution of this study lies in revealing the chain-like mediating pathway formed by “perceived restorativeness” and “musical resonance.” This integrates the physical properties of architectural materials, the user’s psychological restorative process, and the higher-order artistic emotional experience into a coherent theoretical model, deepening our understanding of the mechanisms shaping user experience in cultural spaces.

5.3. Design Implications

The chain mediation pathway of “PWD → PR → MR → US” validated in this study offers an actionable, sequential workflow for the design of wooden music halls. At its core, this process frames the shaping of user experience as a timed and ordered psychological preparation that prioritizes restoration before resonance. Based on the findings, a two-phase design workflow is proposed.

The objective of the first phase is to establish an environmental foundation that effectively fosters perceived restorativeness. This phase begins as the audience enters the hall, with the central design goals of reducing user stress and preparing them for a state of attentive listening. Step one involves establishing visual clarity through macro-spatial order: by employing unified wood tones and natural grain patterns, a harmonious and predictable visual environment is created, significantly reducing cognitive load during wayfinding and acclimation. Step two entails the synchronized engagement of tactile and olfactory cues in a subtle manner. Architects or venue designers should ensure that the warm texture of wooden surfaces and the faint, diffuse scent of wood provide consistent, calming signals to the audience in a non-intrusive way. Step three, which also constitutes the acoustic task of this phase, is laying the foundation for acoustic clarity. Since wood’s acoustic properties are relatively less stable compared to some other materials, architects or acousticians must select appropriate wood types for designing sound paths and achieve precise control over sound through wooden materials, eliminating distracting background noise and unfavorable reflections to create an initial sound field that enables effortless listening, thereby clearing obstacles for deep appreciation.

Once the first phase has successfully established a calm and focused psychological baseline for the audience, the emphasis of the second phase shifts toward guiding them into a state of profound musical resonance. Here, the environment should transition from offering background support to actively facilitating empathy. Step four involves refined acoustic adjustment. Depending on the genre and type of performance, such as the intimacy of chamber music or the grandeur of a symphony orchestra, parameters like reverberation and lateral reflections should be dynamically fine-tuned while maintaining clarity, in order to enhance the music’s envelopment and expressive power. Step five focuses on transforming the previously established visual and tactile comfort into sustained emotional support. The sense of order, warmth, and intimacy evoked by the wood should now serve to strengthen the audience’s sense of presence, allowing the cognitive resources freed up earlier to be fully invested in receiving and resonating with the emotional content of the music.

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions

This study retains several limitations that warrant addressing and expanding upon in subsequent research. First, evidence derived from cross-sectional structural equation modeling struggles to confirm causal directionality. Sample sources and scenario types may introduce selection bias, while self-report measures remain susceptible to social desirability and recall errors. Since the primary objective of this study was to verify the generalizability of the chained mediation pathway, we opted to aggregate data from all seven venues to ensure sufficient statistical power. The limitation of this approach lies in its inability to examine venue-specific effects or analyze the influence of specific factors such as architectural features or music genres. Furthermore, precise correlations between wood proportion, texture scale, and acoustic parameters such as reverberation time and clarity with individual experiences remain unestablished. Objective monitoring of olfactory and tactile intensity is lacking, and the temporal sequence of recovery preceding resonance has not been dynamically captured.

Second, musical resonance and recovery may be moderated by seating position, music genre, listeners’ musical literacy, and sensory sensitivity. Material preferences and cultural contexts could also affect mechanism stability across different populations and music types (e.g., classical vs. popular music), yet these heterogeneities remain under-examined, and the generalizability of findings across different cultural contexts and music genres (e.g., classical vs. popular music) requires further verification. Looking ahead, we recommend employing longitudinal designs with on-site interventions or randomized controls. Manipulating light color, surface materials, diffuse reflection, and background noise, combined with seat randomization, can enhance causal identification. This should be supplemented by multimodal synchronous recording of heart rate variability, electrodermal activity, eye movements, and instantaneous subjective reports to characterize the chained dynamics from recovery to resonance. At the modeling level, introduce multi-layer and nonlinear threshold tests to establish dose–response curves for material proportions and scent intensities, cross-validated with acoustic simulations and auditory assessments. For contextual extrapolation, conduct cross-cultural and multi-venue verification to compare equivalent formulations and marginal benefits between wood and alternative materials, while evaluating operational strategies such as guide optimization, flow pacing, and noise management for amplifying mechanism pathways. Translate key variables into actionable design and operational metrics for practical implementation; promote open data and pre-registration to enhance conclusion robustness; further track satisfaction improvements to behavioral conversions, including repeat visits, dwell time, and word-of-mouth dissemination.

6. Conclusions

This study constructed and tested a chain mediation model to elucidate the psychological mechanism through which the perception of wooden design influences user satisfaction in wooden concert halls. The empirical findings, derived from a robust sample of 965 users and analyzed via CB-SEM, offer clear conclusions regarding the proposed hypotheses: Regarding H1, which posited a direct positive effect of wooden design perception (PWD) on user satisfaction (US), the results provided strong support. The significant direct path coefficient (β = 0.268, p < 0.001) confirms that the multisensory experience of wooden elements itself is a substantial contributor to overall satisfaction. Regarding H2, which proposed that perceived restorativeness (PR) mediates the relationship between PWD and US, the findings were confirmed. The bootstrap analysis revealed a significant specific indirect effect (Effect = 0.067, 95% CI [0.046, 0.089]), demonstrating that wooden design fosters satisfaction partly by creating a restorative environment that alleviates mental fatigue. Regarding H3, which hypothesized that musical resonance (MR) serves as a mediator, the results were also supported. The data indicated a significant and substantial indirect pathway through MR (Effect = 0.120, 95% CI [0.085, 0.156]), underscoring that wooden design enhances satisfaction by facilitating a deeper emotional and cognitive connection with the music itself. Most critically, regarding H4, which postulated a sequential mediation path (PWD → PR → MR → US), the analysis yielded definitive support. The significant chained mediation effect (Effect = 0.011, 95% CI [0.006, 0.018]) validates the core theoretical model of this study: the wooden environment first induces a state of psychological restoration, which in turn optimizes the listener’s capacity for musical resonance, ultimately leading to heightened satisfaction.

In summary, all four hypotheses were fully supported by the data. The primary contribution of this research lies in unveiling this sequential “restoration-to-resonance” mechanism, providing an evidence-based explanation for the impact of wooden design. These findings integrate restorative environment theory with musical aesthetics, establishing a coherent framework for future research and offering actionable insights for the design of cultural spaces that aim to enhance emotional experiences.