1. Introduction

Concrete is widely used in various industries as one of the main materials for structures. Therefore, it is expected that concrete should possess certain minimum durability, particularly in terms of strength, impact resistance, permeability, freeze–thaw resistance, and abrasion resistance [

1]. During the service life of hydraulic tunnel concrete, it undergoes severe abrasion damage due to hydraulic conditions, such as the impact of high-velocity sand-laden water and its own performance factors. Studying concrete abrasion damage is a complex issue, and the lack of a convenient and accurate abrasion depth prediction model has brought many difficulties to the durability design of hydraulic tunnels.

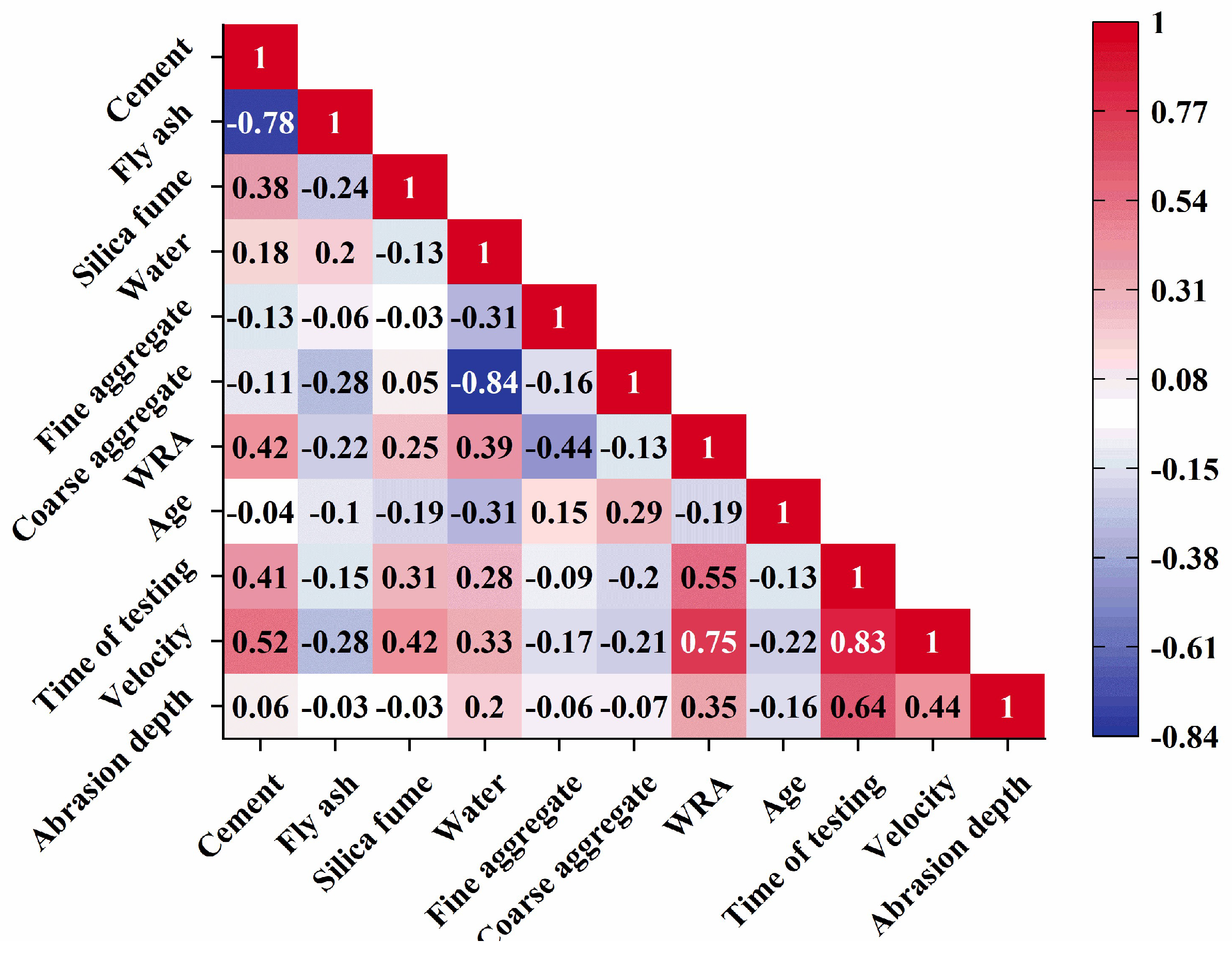

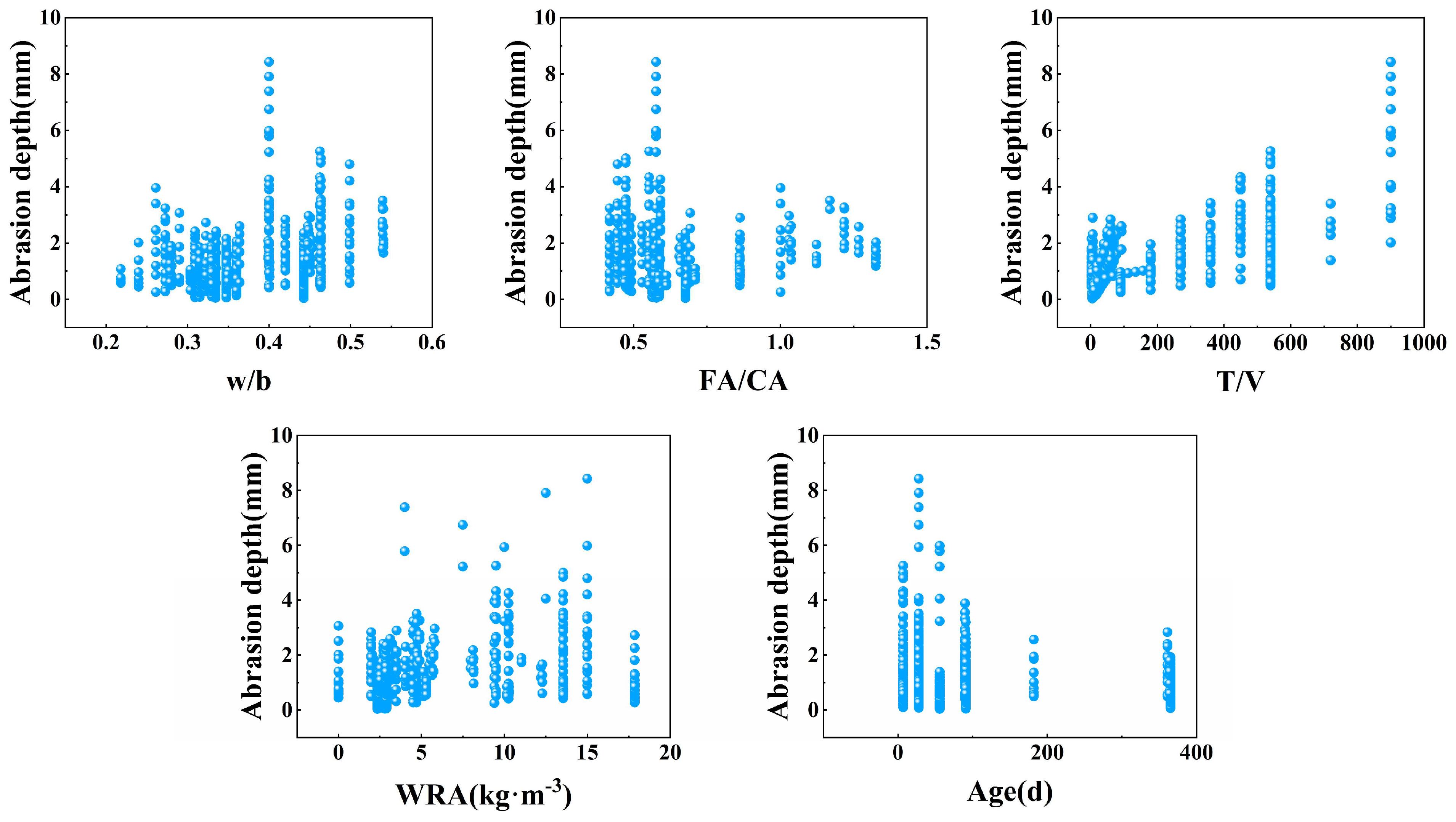

The abrasion resistance of concrete is influenced by multiple factors, including concrete mix proportion, curing age, and hydraulic conditions. To investigate these influencing factors, scholars have conducted targeted experiments: Ghafoori et al. [

2] performed tests in accordance with ASTM C 779 [

3] Procedure C and found that the water–cement ratio (0.21–0.34) and aggregate–cement ratio (9:1–3:1) exerted significant effects. When the 28-day standard-cured concrete achieved a compressive strength of 40–79 MPa, its abrasion resistance improved with optimized mix proportions. Siddique et al. [

4] replaced fine aggregates with 35–55% Class F fly ash and confirmed that this admixture could significantly enhance the full-age abrasion resistance of concrete. Ghafoori and Diawara [

5] discovered that replacing 5–20% of fine aggregates with silica fume improved abrasion resistance, and the improvement effect continued to strengthen until the silica fume content reached 10%. Zhu et al. [

6] combined the underwater methods specified in ASTM C1138 [

7] and SL 352-2006 [

8], and clarified that the coupling of freeze–thaw cycles and hydraulic abrasion exacerbates concrete abrasion depth. From the aforementioned literature, it is evident that concrete abrasion resistance is not determined by a single factor, but rather a core property jointly regulated by material mix proportion, curing conditions, environmental factors, and hydraulic actions.

In the field of concrete abrasion depth prediction, early scholars conducted extensive research on empirical and semi-empirical models, laying a foundation for subsequent studies. However, limited by their modeling approaches, these models still have significant shortcomings and cannot meet the demands of practical engineering [

9].

For classical empirical models, researchers constructed prediction models by focusing on the correlation between a single factor and abrasion depth, resulting in typical forms such as linear, polynomial, and power function models. Among them, Naik et al. [

10] conducted abrasion tests using the rotating cutter method in accordance with ASTM C-944 [

11] and pointed out that within a certain compressive strength range, the abrasion depth of concrete is inversely proportional to its compressive strength, thereby establishing a quantitative correlation between mechanical properties and abrasion damage. Horszczaruk [

12] studied high-strength concrete for hydraulic structures based on the ASTM C 1138 [

7] method and proposed a polynomial model between abrasion depth and compressive strength, filling the gap in abrasion prediction for high-strength concrete.

Siddique et al. [

4] used a power function in the form of y = ax

−b to fit the relationships between abrasion depth and multiple mechanical indicators (e.g., compressive strength, splitting tensile strength), increasing the model’s goodness of fit R

2 to over 0.93. Zhu et al. [

6] also employed a power function to develop an abrasion depth prediction model under different freeze–thaw cycles, incorporating environmental factors into the empirical prediction framework. Nevertheless, the limitations of such models are equally prominent: the models by Naik and Horszczaruk can only characterize the single relationship between abrasion depth and compressive strength, failing to reflect the coupling effects of other key factors, such as mix proportion and hydraulic conditions. Even though the models by Siddique and Zhu expanded the coverage of influencing factors, they still suffer from narrow applicability—the former is only suitable for specific mechanical property test conditions, while the latter is limited to freeze–thaw coupling environments. Therefore, these models are difficult to apply to complex abrasion scenarios in practical engineering, and their overall prediction accuracy is constrained by the single-factor modeling approach, which cannot meet the requirements of high-precision design.

In the field of semi-empirical models, Bitter et al. [

13,

14,

15] developed semi-empirical models by combining experimental measurements and mathematical theory, thereby improving prediction accuracy. However, the application of these semi-empirical models is limited to specific operating ranges or specially designed experiments [

16]; once outside this scope, the prediction deviation of the models increases significantly, making it difficult to achieve engineering-level generalization.

With the development of artificial intelligence technology, machine learning (ML) methods, relying on their strong capabilities in multi-feature information processing and complex relationship learning, have gradually replaced traditional empirical models and become a research hotspot in concrete abrasion depth prediction. Compared with empirical models that can only fit a single factor, algorithms such as artificial neural networks (ANNs), random forests (RFs), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) can integrate multi-dimensional parameters (e.g., concrete properties, hydraulic conditions), significantly enhancing prediction flexibility. For example, Gencel et al. [

1] correlated factors such as metal aggregate content, cement content, and applied load using an ANN model, confirming that its prediction accuracy was significantly superior to that of the traditional general linear model (GLM), and verifying the advantages of ML methods in multi-variable abrasion prediction for the first time. Liu [

16] further integrated three core factors (hydraulic conditions, curing age, and concrete mix proportion), and constructed a model by combining Bayesian optimization with the RF-ANN algorithm, overcoming the limitation of “incomplete feature coverage” in early ML models. Based on Liu’s dataset, Moghaddas [

17] optimized the hyperparameters of five different ML algorithms using the Parsen Tree Estimator (PTE) [

18] for prediction, while Amin [

19] used multi-expression programming (MEP) and gene expression programming (GEP) for prediction, further promoting the accuracy improvement of ML models.

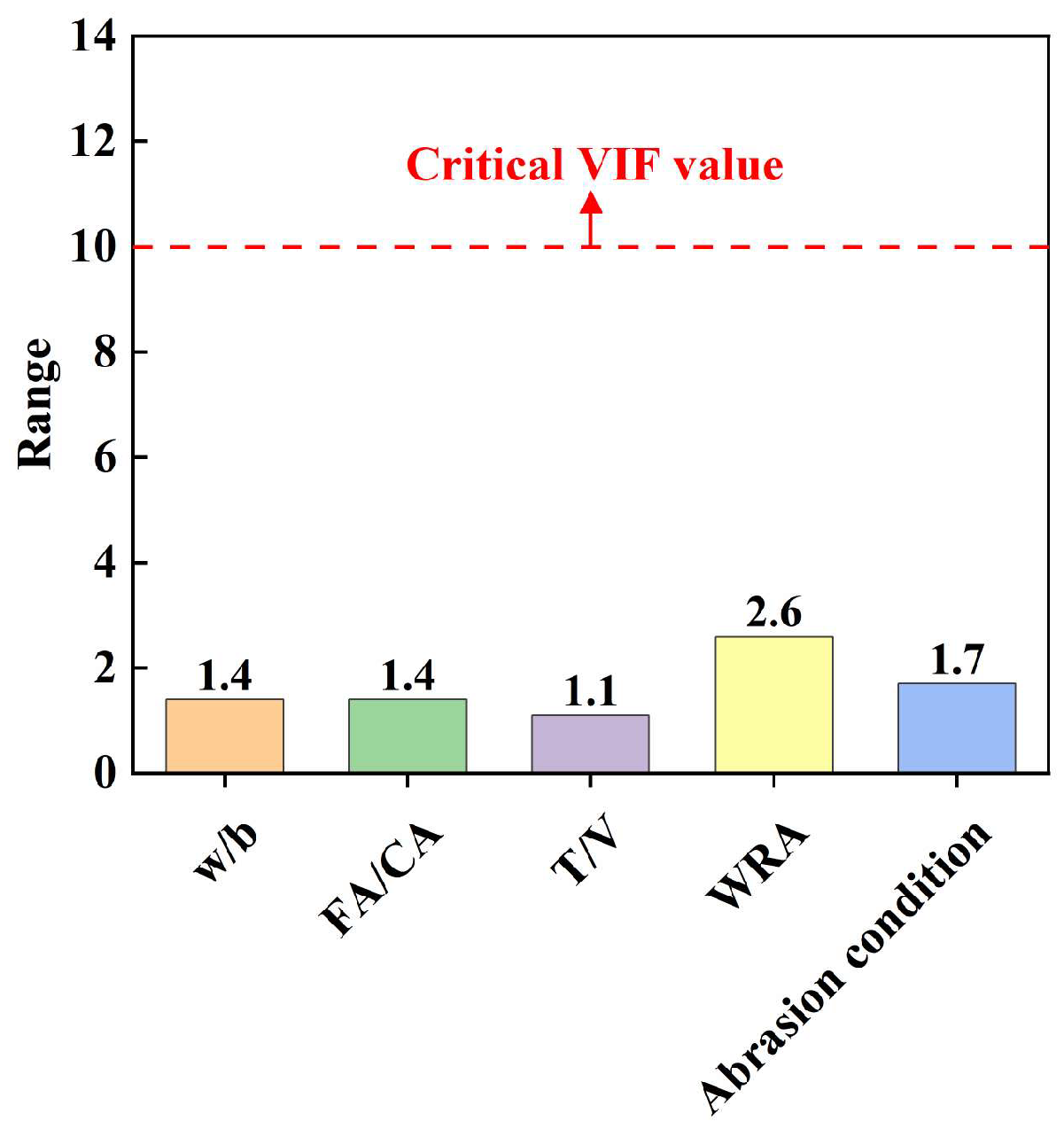

However, existing ML studies still have gaps that prevent them from being directly applied to the complex engineering needs of hydraulic structures. First, incomplete data coverage and abrasion mechanism characterization. Malazdrewicz [

20] and Sadowski [

21] and others built models based on small-sample data from the single ASTM C944 standard [

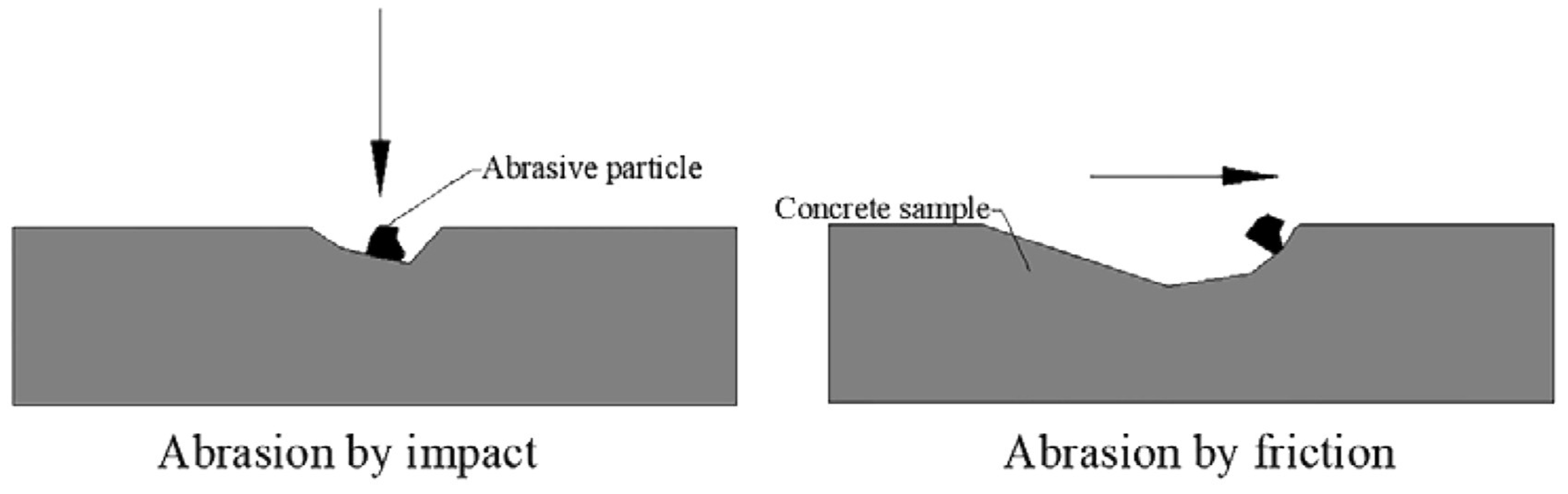

11], which only simulates dry friction scenarios and cannot cover the actual “friction–impact coexistence” abrasion mechanism of hydraulic tunnels (as shown in

Figure 1, the normal force caused by impact and the shear force caused by friction jointly exacerbate abrasion, and these two effects are difficult to manifest simultaneously in a single standard test). Second, limitations in hyperparameter optimization methods and model architecture. Existing studies mostly use Bayesian optimization (Liu [

16]), PTE (Moghaddas [

17]) or evolutionary algorithms (Amin [

19]) to optimize single ML models and have not yet combined meta-heuristic algorithms with EL (ensemble learning). Ensemble learning significantly improves the accuracy of models in prediction tasks and their robustness against data disturbances; compared with single ML models, EL more effectively handles data noise and bias, reduces the risk of overfitting, and exhibits stronger robustness and generalization ability in complex problems [

22]. Recent studies have further shown that ensemble models combined with meta-heuristic algorithms outperform traditional ensemble models [

23].

As an advancement of heuristic algorithms (which generate a fixed output for a given input), meta-heuristic algorithms are non-deterministic methods due to the inclusion of random factors [

24]. A meta-heuristic algorithm is a problem-independent technique that does not leverage any specific characteristics of the target problem. It is a combination of random algorithms and local search algorithms. This type of non-deterministic method uses randomly generated variables to explore near-optimal solutions within the problem space [

25]. Meta-heuristic algorithms are often employed to optimize model hyperparameters, thereby enhancing model robustness. The Genghis Khan Shark Optimizer (GKSO), proposed in 2023, exhibits advantages such as strong optimization capability, advanced search strategies, and low parameter sensitivity.

Therefore, this study developed three hybrid ensemble models based on GKSO and ensemble learning to predict the abrasion depth of concrete used in hydraulic tunnels. By integrating multi-standard test data and introducing SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) feature analysis, the models can not only adapt to the dual mechanisms of friction and impact but also provide quantitative basis for engineering design—rather than merely focusing on improving theoretical accuracy.

Based on this, the innovation of this study is specifically reflected in the following three aspects:

- (1)

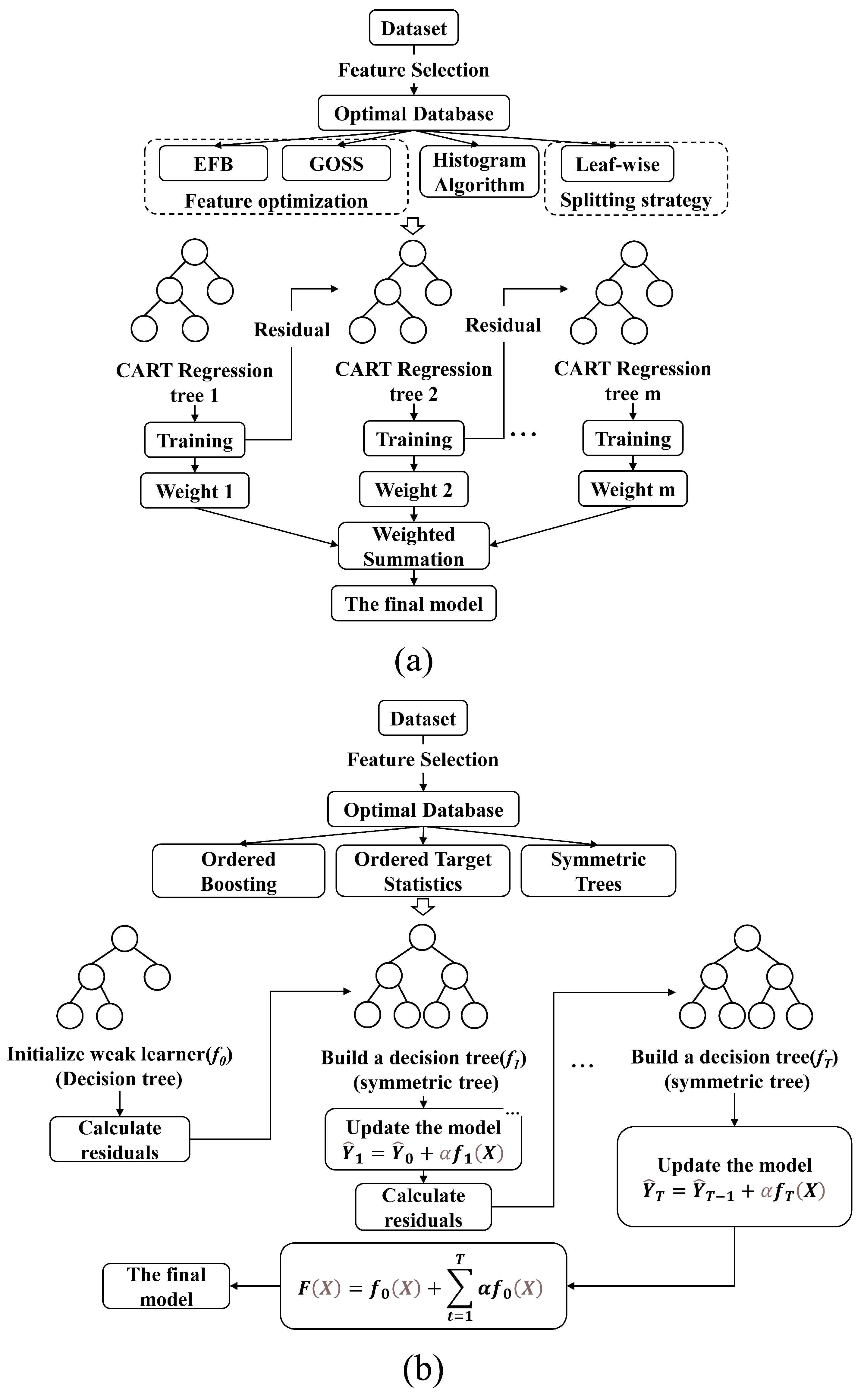

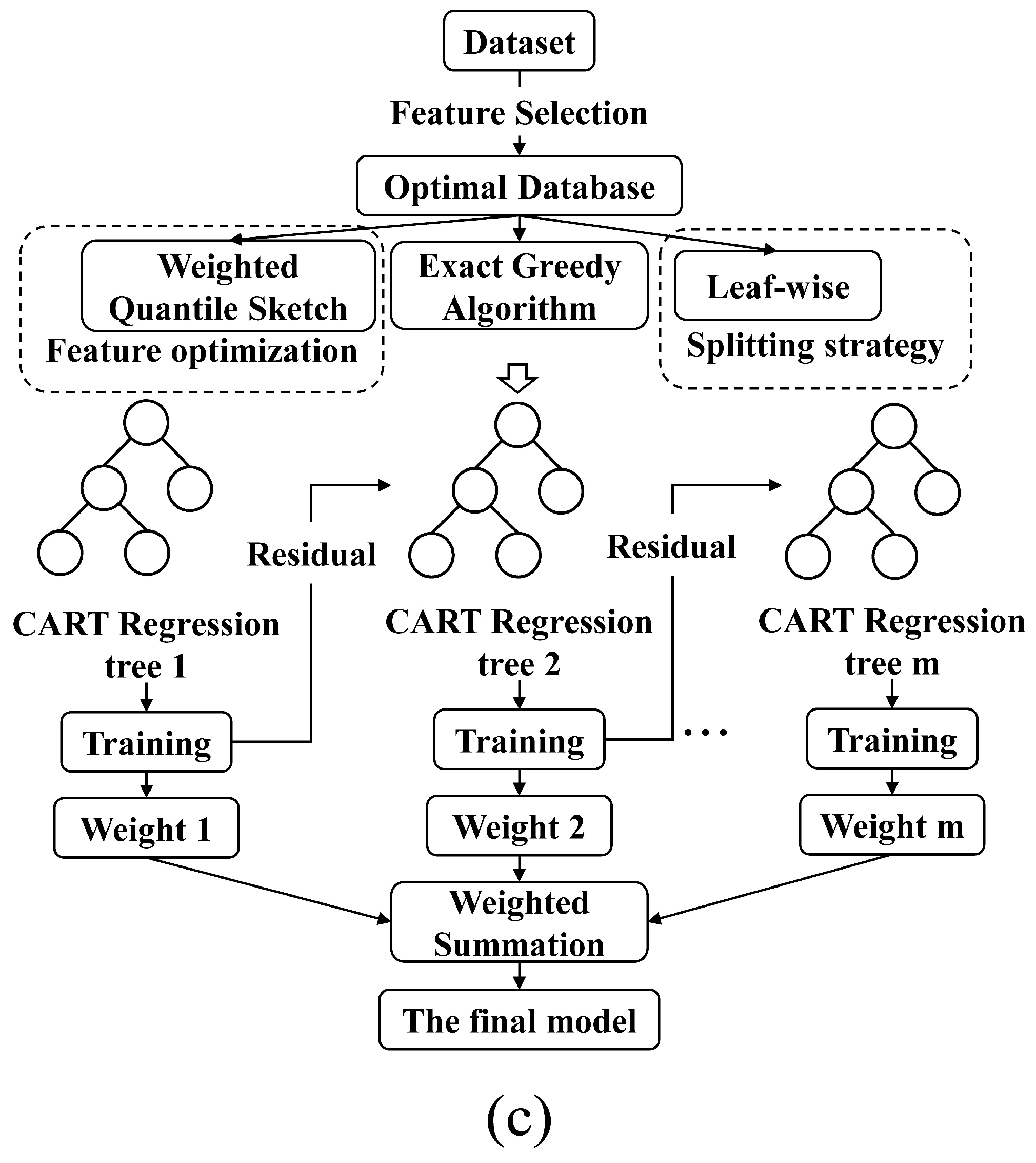

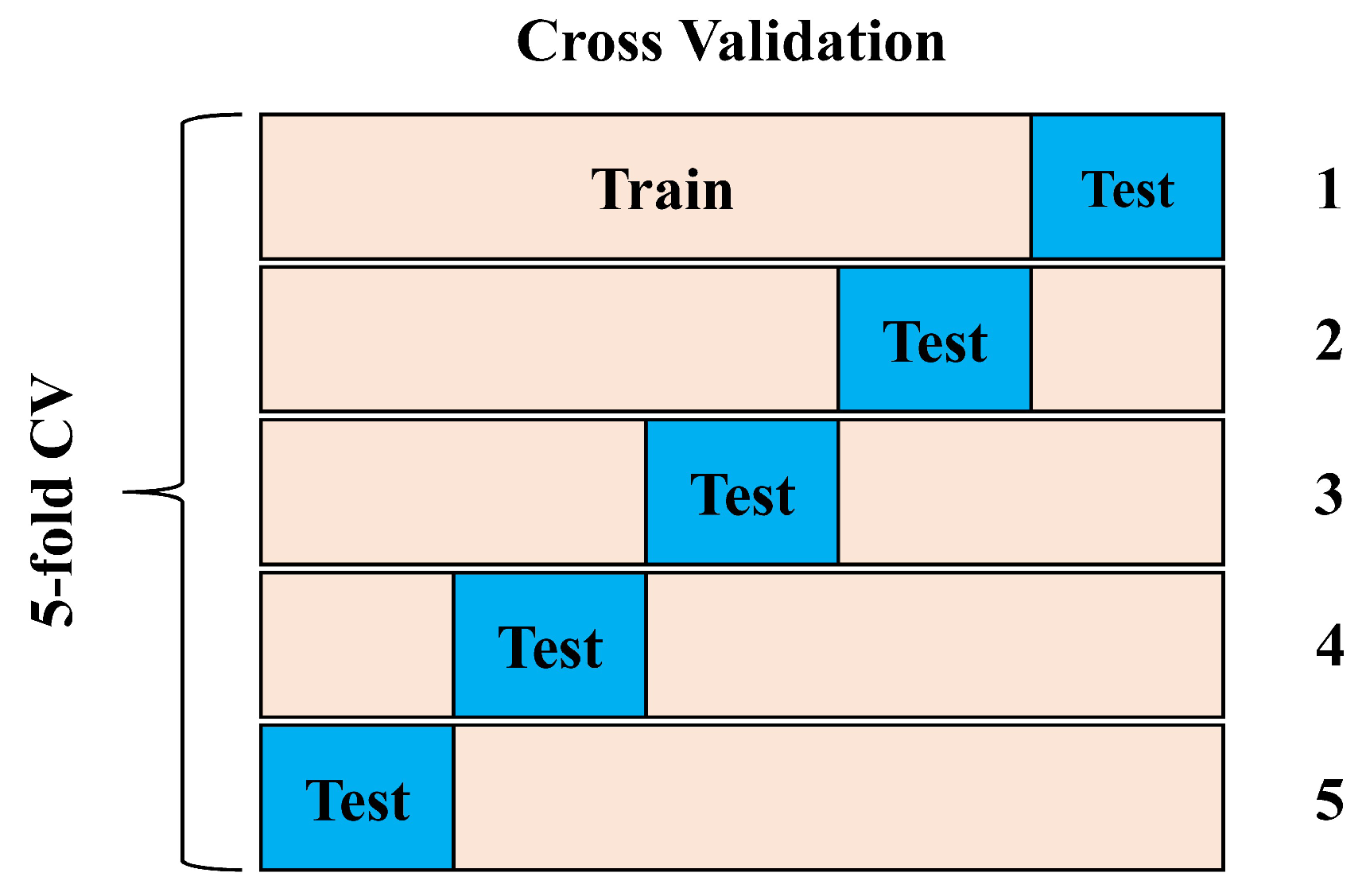

Combining the meta-heuristic algorithm (GKSO) with three mainstream ensemble algorithms (LightGBM, XGBoost, and CatBoost). GKSO is used for efficient hyperparameter optimization, and 5-fold cross-validation is adopted to enhance generalization ability.

- (2)

Achieving high-precision prediction for datasets under two abrasion mechanisms (friction and impact). Through additional feasibility validation tests to verify the reliability of the model.

- (3)

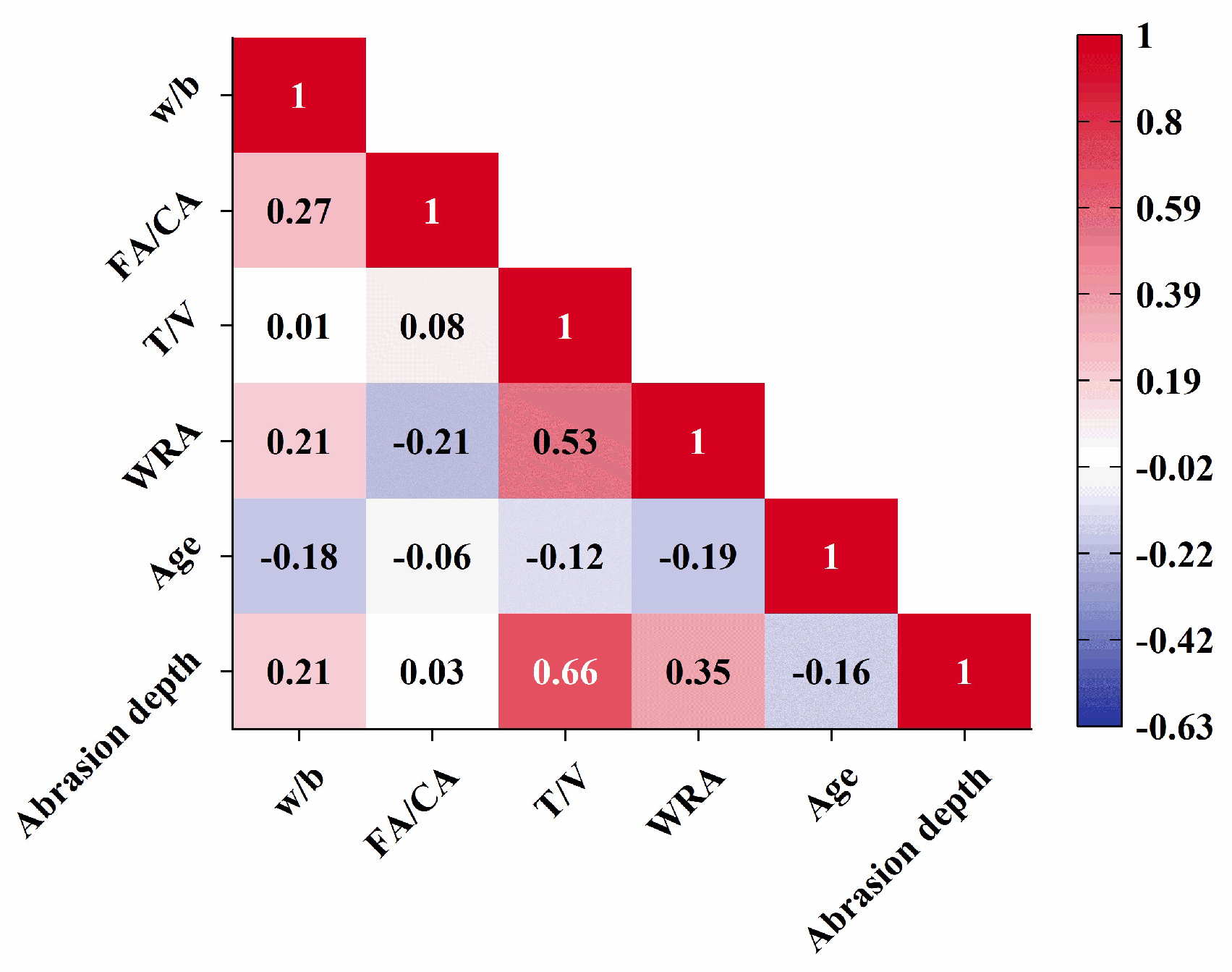

Introducing SHAP analysis to quantify the influence weight of each feature, identifying the T/V ratio (ratio of abrasion test time to loading speed) and water–cement ratio as key influencing factors. This transforms the “black-box” model into an interpretable decision-making tool, providing clear parameter adjustment directions for the optimization of concrete mix proportion.

3. Results and Discussion

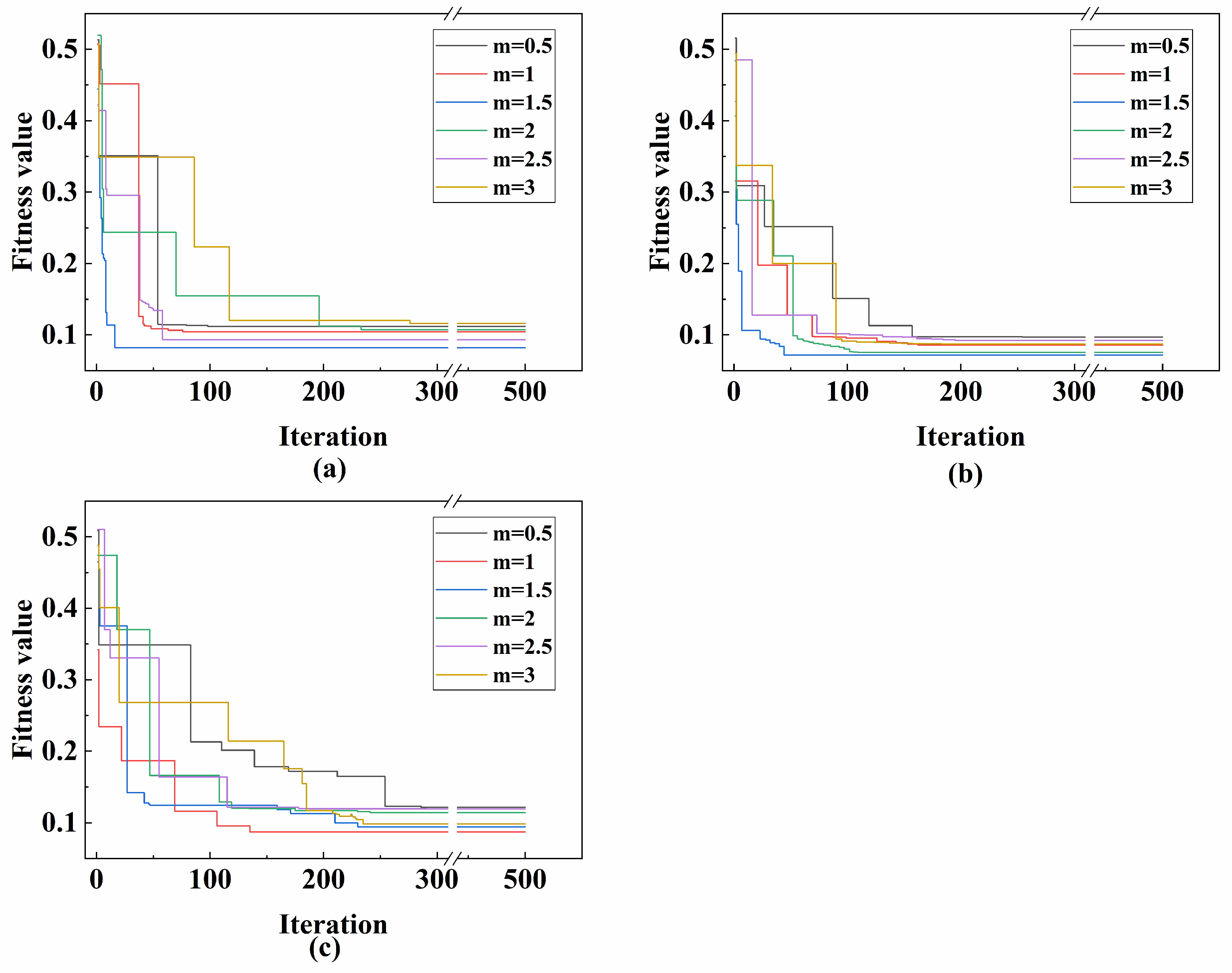

Figure 8 shows the iteration curves of the three groups of models after hyperparameter optimization.

Figure 10a is the iteration curve of six GKSO-LightGBM models;

Figure 10b is that of six GKSO-CatBoost models;

Figure 10c is that of six GKSO-XGBoost models. It can be seen from the figures that all models reached the minimum fitness value before 300 iterations. GKSO-CatBoost had the best optimization effect overall, and GKSO-LightGBM and GKSO-CatBoost had faster convergence rates than GKSO-XGBoost. Among the six GKSO-LightGBM models, the m = 1.5 group performed best; among the six GKSO-CatBoost models, the m = 1.5 group performed best; among the six GKSO-XGBoost models, the m = 1 group performed best. In actual prediction applications, the corresponding m values can be prioritized.

Table 4 shows the final fitness values of GKSO-LightGBM, GKSO-CatBoost, and GKSO-XGBoost after hyperparameter optimization under different m values.

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7 show the model prediction results of the three groups under different m values.

Table 5 shows the prediction results of GKSO-LightGBM under different m values,

Table 6 shows those of GKSO-CatBoost, and

Table 7 shows those of GKSO-XGBoost. The data in the tables indicate that consistent with the convergence results of the average MSE during iteration, among the six GKSO-LightGBM models, the m = 1.5 group had the best prediction results; among the six GKSO-CatBoost models, the m = 1.5 group performed best; among the six GKSO-XGBoost models, the m = 1 group performed best. After obtaining the above results, the corresponding hyperparameter combinations were extracted, as shown in

Table 8. Comparing the optimized prediction results of the same model under different m values, it is not difficult to find that the m = 1.5 group performed excellently. Although for the XGBoost group, the optimization result of the m = 1 group was better than that of m = 1.5, the difference in R

2 between the training set and test set was less than 0.01. Therefore, m = 1.5 can be set as the optimal value, which is consistent with the relevant results in Reference [

46], proving the feasibility of GKSO algorithm optimization.

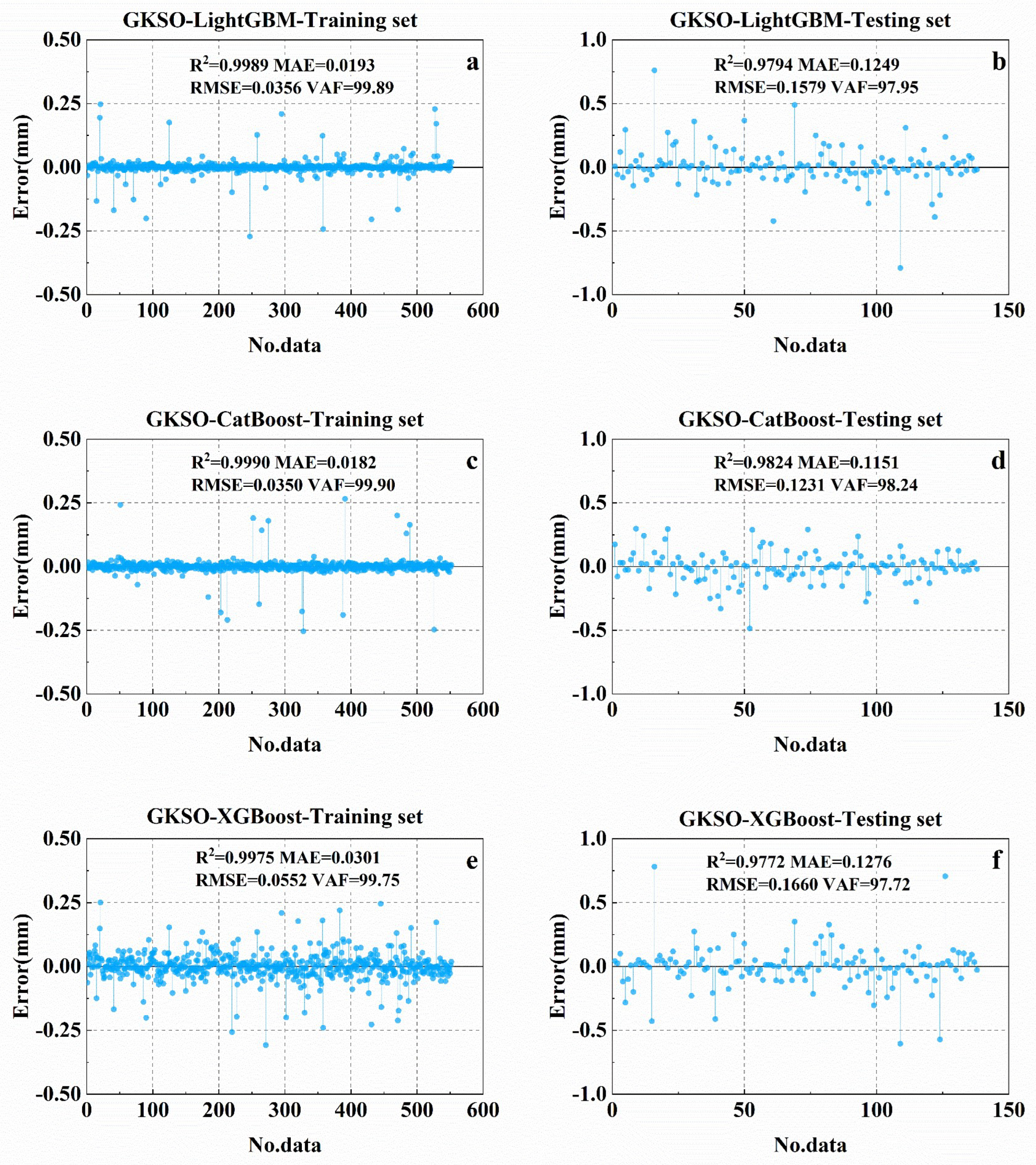

Figure 11 is the error plot of the three hybrid models, where the error is the difference between the true value and the predicted value. For the error performance of the three hybrid models on the training set, the errors are all less than 0.4 mm, indicating that each hybrid model has excellent performance in predicting abrasion depth on the training set. On the training set, the error points of the XGBoost group are significantly less concentrated near the x-axis than those of the LightGBM and CatBoost groups, but overall, they still show low errors. For the LightGBM and CatBoost groups on the training set, the error points are concentrated near the x-axis, with only a few points having errors exceeding 0.25. This indicates the high accuracy of these two hybrid models. On the test set, all errors of the three hybrid models are less than 1 mm. For the LightGBM group, less than 2% of the prediction results have errors higher than 0.5 mm, 8.7% have errors higher than 0.25 mm, and approximately 71% have errors lower than or equal to 0.1 mm. For the XGBoost group, approximately 3% of the prediction results have errors higher than 0.5 mm, 8% have errors higher than 0.25 mm, and 65% have errors lower than or equal to 0.1 mm. For the CatBoost group, 0.72% of the prediction results have errors higher than 0.5 mm, 6.5% have errors higher than 0.5 mm, and 74% have errors lower than or equal to 0.1 mm. Therefore, by comparison, the GKSO-CatBoost model is significantly superior to other models in correcting high-error predictions and has the best error performance; in terms of prediction errors between 0.25 and 0.5, GKSO-LightGBM has 1.7% more than GKSO-XGBoost, but in other ranges, GKSO-LightGBM has better performance.

3.1. Model Comparison and Selection

Table 9 shows the prediction results and comprehensive scores of nine models, including models optimized by GKSO, models optimized by Bayes, and models with default parameters. The results indicate that on both the training and test sets, GKSO-CatBoost obtained the highest score of 36; GKSO-LightGBM was slightly inferior to GKSO-CatBoost, ranking second, with 32 points on both sets; LightGBM with default parameters obtained the lowest score, with 6 points on the training set and 4 points on the test set. Observing the same model under different hyperparameter optimization schemes, for each model, the prediction results under default parameters are poor; after hyperparameter optimization by the Bayes algorithm, the R

2 and VAF of the LightGBM model on the training and test sets increased, and MAE and RMSE decreased, with the most significant optimization range of RMSE on the test set, approximately 43.8%; however, the R

2 and VAF of CatBoost and XGBoost on the training set did not increase but decreased, and MAE and RMSE on the training set increased, with no abnormal performance on the test set, reflecting that the model under default parameters has overfitting, and excessive learning leads to poor performance on the test set. After hyperparameter optimization by the GKSO algorithm, all performance indicators of each model improved positively, with better performance improvement on both the training and test sets than the Bayes algorithm, narrowing the gap in performance indicators between the training and test sets and effectively preventing the model from overfitting, thus avoiding insufficient prediction accuracy.

3.2. Model Feasibility Verification

To validate the feasibility of the abrasion depth prediction model, experimental data from additional literature sources were screened [

46]. Data from experimental groups matching the model’s input characteristics FA/CA, T/V, w/b, WRA, and age) to ensure complete alignment between input variables and model design, thereby establishing a robust data foundation for subsequent prediction validation.

In all experimental groups, aggregate quantities were fixed (coarse aggregate ‘stone’ at 1263 kg/m

3, fine aggregate ‘sand’ at 569 kg/m

3). Water-reducing agent (WRA) was not added separately (considered 0%). The curing period was uniformly set at 28 days (standard curing age). Abrasion testing was conducted according to ASTM C1138M-19 [

47] (underwater steel ball method), with loading rates converted via the device’s rotational parameters. Specific input characteristic data is as follows:

- (1)

FA/CA: The aggregate (fine aggregate) consumption for all mix designs is 569 kg/m3, and the stone (coarse aggregate) consumption is 1263 kg/m3. Calculated by mass ratio, FA/CA = 569/1263 ≈ 0.45 (fixed value, no variation between mix designs).

- (2)

T/V: Based on the ASTM C1138M-19 apparatus parameters, the rotational angular velocity = 0.36 rad/s, and the steel ball’s radius of motion , calculated using Formula (4) and taking the average radius of 10 cm, the velocity is converted to V = 0.036 m/s.

Ultimately, T/V = 120,000 s2/m.

- (3)

w/b: Experimental settings: Three gradients of 0.35, 0.40, and 0.45 were employed as core variables for model input. The specific values for each group are detailed in

Table 10.

- (4)

WRA: No additional water-reducing agent was added to the experiment; all groups had WRA = 0%.

- (5)

Age: All specimens were standard-cured for 28 days; age = 28 days.

The wear depth was measured using a three-dimensional topography scanning system (5 mm point spacing, 400 points per specimen). The final selection yielded data corresponding to the input characteristics and abrasion depth for three core experimental groups, as shown in

Table 10. All data points exhibiting parallel specimen deviations exceeding 10% were excluded to ensure reliability. Using GKSO-Catboost to input and predict the aforementioned three datasets yielded the results shown in

Table 11. The table also calculates the RE (relative error) between the predicted and actual values. The results indicate that the error in all predictions is less than or equal to 13.6%, falling within the acceptable range for engineering purposes and confirming the practicality of the GKSO-CatBoost approach.

Table 10.

Model input features and documented abrasion depth measurement data.

Table 10.

Model input features and documented abrasion depth measurement data.

| Group | w/b | FA/CA | T/V | WRA | Age | Ad |

|---|

| 1 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 120,000 | 0 | 28 | 6.71 |

| 2 | 0.40 | 0.45 | 120,000 | 0 | 28 | 6.65 |

| 3 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 120,000 | 0 | 28 | 8.46 |

Table 11.

GKSO-Catboost Prediction Results.

Table 11.

GKSO-Catboost Prediction Results.

| Group | w/b | FA/CA | T/V | WRA | Age | Ad (Pre) | RE |

|---|

| 1 | 0.35 | 0.45 | 120,000 | 0 | 28 | 7.62 | 13.6% |

| 2 | 0.40 | 0.45 | 120,000 | 0 | 28 | 5.85 | 12.0% |

| 3 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 120,000 | 0 | 28 | 7.66 | 9.5% |

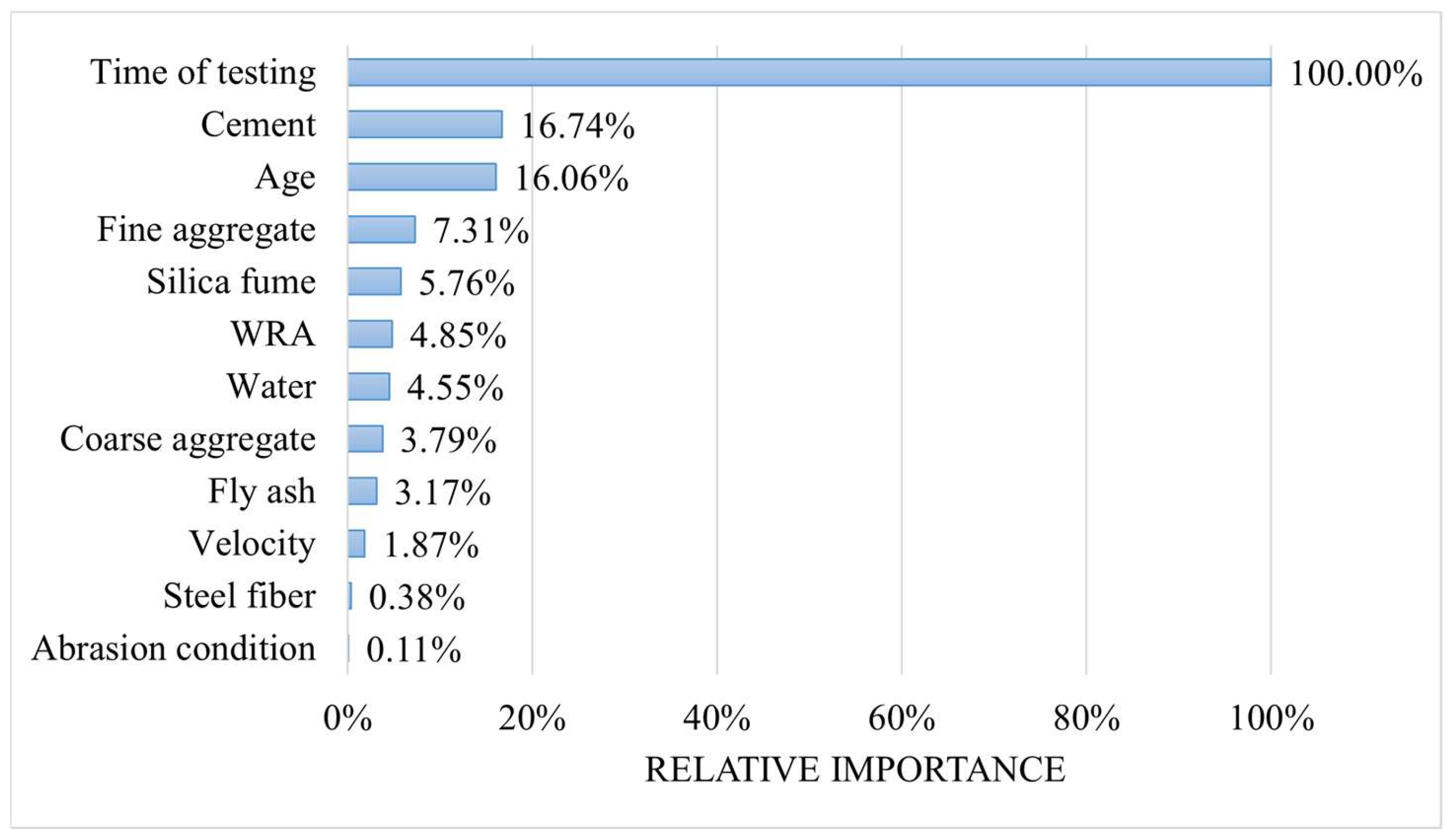

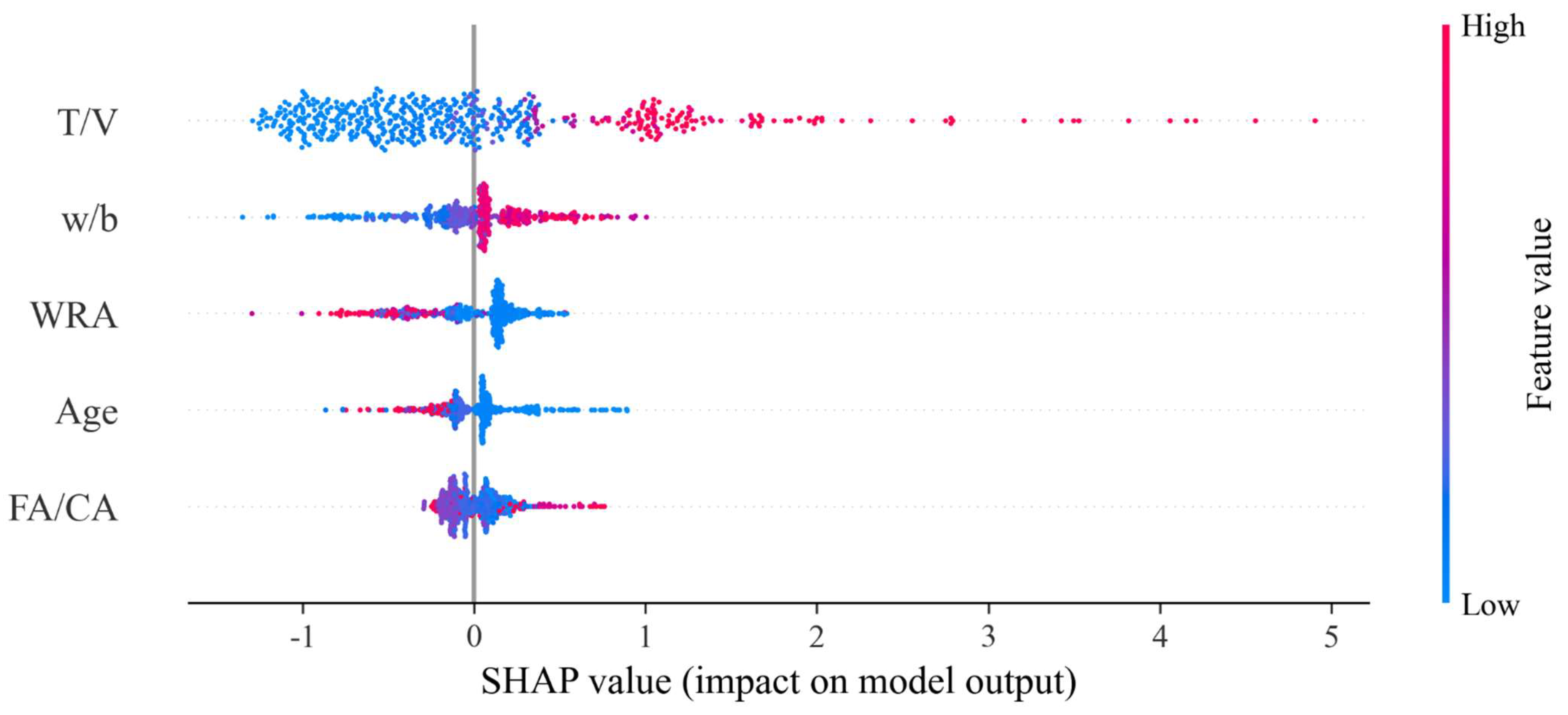

3.3. SHAP Result Analysis

SHAP is crucial for understanding the contribution and interaction of each feature in the model, providing insights to enhance interpretability and improve feature selection [

48]. This study extracted the SHAP global importance plot of the optimal model GKSO-CatBoost, as shown in

Figure 12. In the figure, blue points represent low feature values, red points represent high feature values, and purple points represent feature values between the two, with color depth corresponding to the value within the interval. The figure indicates that T/V has the greatest impact on the model output, followed by w/b, WRA, age, and FA/CA. T/V is positively correlated with abrasion depth overall, with the largest SHAP value range, and high T/V values often have a positive impact on the model’s predicted abrasion depth. An increase in the T/V ratio means that the material withstands higher abrasion energy per unit time. Longer test time or higher loading speed will lead to an increase in cumulative abrasion. This is consistent with physical laws, as abrasion depth is positively correlated with load action time and kinetic energy input. w/b shows a more obvious positive correlation with model prediction, with high w/b values distributed in the positive SHAP value region and low w/b values in the negative region, and the distribution range of points is significantly smaller than that of T/V. An increase in w/b reduces concrete compactness and increases capillary porosity, which will lead to a more fragile ITZ (interface transition zone), reduced bond strength between aggregate and paste, and easier paste spalling and aggregate pull-out during abrasion. Therefore, the abrasion resistance of high w/b concrete decreases significantly. For WRA, high WRA values are concentrated in the negative SHAP value region, and low WRA values are distributed in both positive and negative SHAP value regions, with a complex relationship with SHAP values. Similarly, the distribution characteristics of age have a complex relationship with SHAP values, but it is worth noting that high ages are concentrated in the negative SHAP value region, corresponding to a reduction in predicted abrasion depth in the model. Under normal curing, a longer age will lead to higher compressive strength in concrete. According to the empirical formula: abrasion depth

, it can be inferred that the model correctly identifies the relationship between features and true output. For FA/CA, there is no obvious monotonic relationship between high/low feature values and SHAP values, but high and low value points are scattered in positive and negative regions. It can be seen that an appropriate FA/CA can optimize the gradation, enhance skeleton compactness, and improve abrasion resistance.

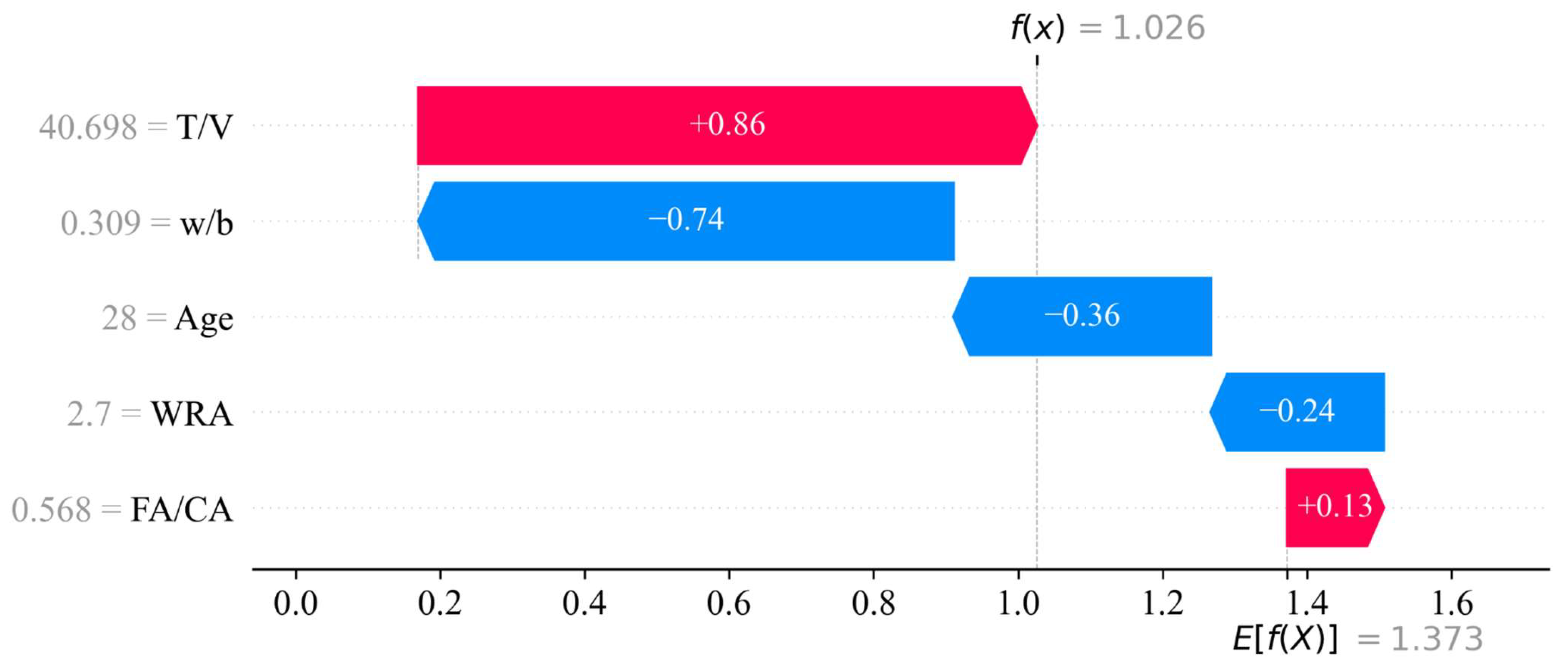

Figure 13 shows the feature contribution decomposition for the model’s prediction of concrete abrasion depth. In the figure, the predicted value (f(x)) is 1.026 mm, and the baseline value (E[f(X)]) is 1.373 mm. The measured abrasion depth of this case is 1.650 mm. The contribution of each feature to this case is ranked as T/V, w/b, age, WRA, and FA/CA, with SHAP values of 0.86, −0.74, −0.36, −0.24, and 0.13, respectively.

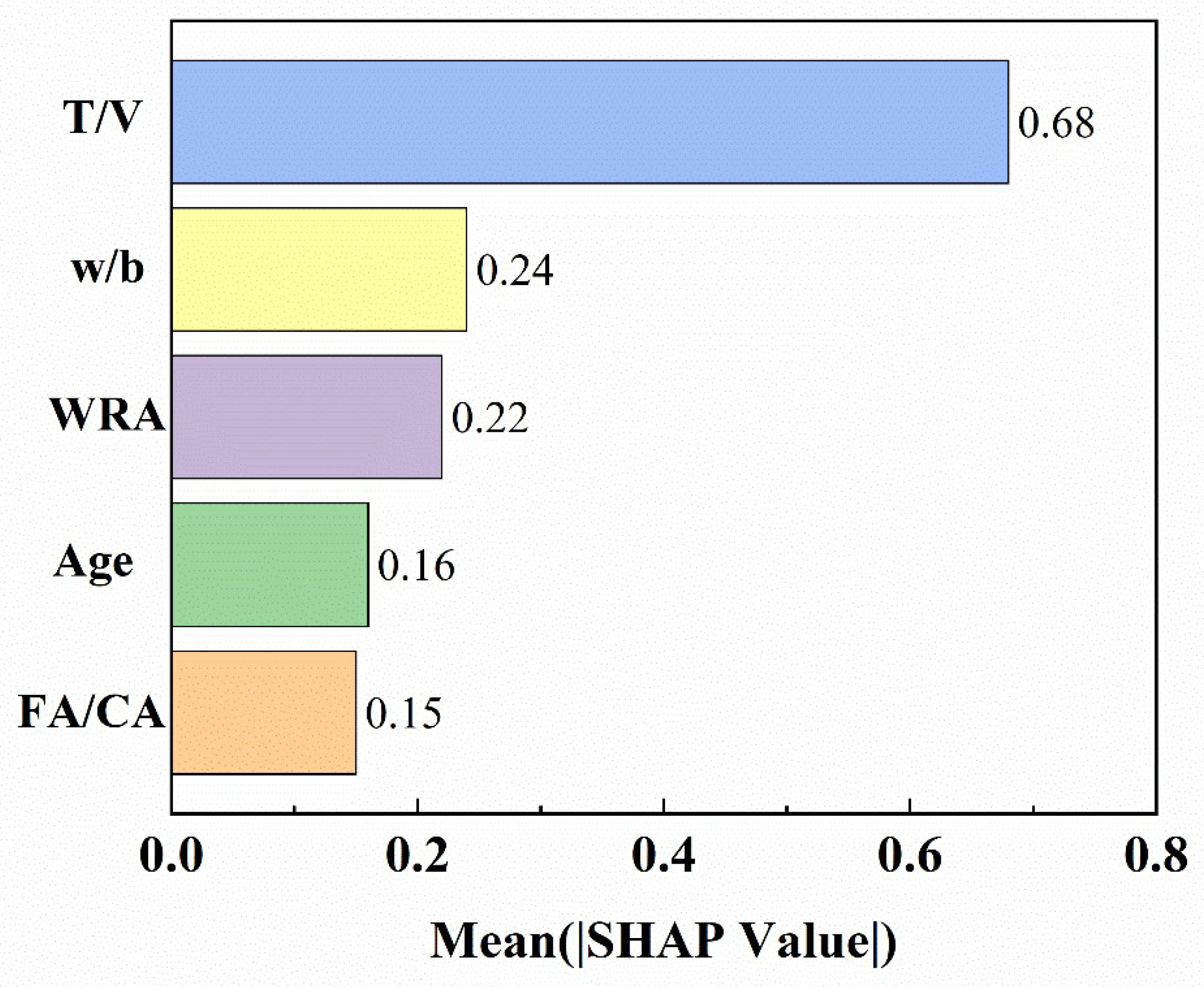

Figure 14 shows the feature importance ranking explained by SHAP, where T/V has the highest importance of 0.68, followed by w/b, age, WRA, and FA/CA. T/V is significantly higher than the other four features, dominating the model’s prediction output.

4. Research Significance and Limitations

This study constructed a high-precision prediction model for concrete abrasion depth in hydraulic tunnels based on the combination of meta-heuristic algorithms and ensemble learning. By introducing GKSO to optimize the hyperparameters of three mainstream gradient boosting frameworks (LightGBM, XGBoost, and CatBoost) and adopting K-fold cross-validation, the risk of overfitting was effectively reduced, achieving high-precision prediction of abrasion depth under different standard methods (with the highest R2 of 0.9824 and the lowest RMSE of 0.1231 mm on the test set). This model can provide a scientific basis for concrete durability design, helping engineers accurately evaluate structural life in the early stage. With the help of SHAP interpretability analysis, it provides intuitive guidance for concrete mix optimization. Modeling for two abrasion mechanisms (friction and impact) and analyzing multi-standard test data realize the close combination of model results and engineering practice; meanwhile, the effectiveness of GKSO in hyperparameter optimization is verified, providing a reference for other engineering problems.

In practical applications, engineers and designers can first match the corresponding test standards (such as ASTM C1138, ASTM C944) according to the engineering scenario (such as high sand impact, dry friction), convert T/V through on-site hydraulic parameters (flow rate, test duration), and combine the proposed concrete mix parameters (w/b, FA/CA, etc.) to quickly obtain the predicted value of abrasion depth. If the prediction results do not meet the design requirements, the mix ratio can be adjusted according to the core influence law of w/b in SHAP analysis until the optimal scheme with both anti-wear performance and economy is obtained.

However, this study also has several limitations: although 690 multi-source experimental data were collected, they are still mainly based on experimental conditions in the literature, without a large number of on-site in situ test data, which may limit the generalization ability of the model under extreme or special working conditions. The prediction model is based on specific standard abrasion test methods (such as ASTM C944, C779, C1138, and BIS 1237-1980), and further verification is needed for other uncovered test specifications or complex on-site flow patterns.