Abstract

The growing demand for sustainable construction practices has driven research into self-sensing materials incorporating recycled waste for smart SHM (Structural Health Monitoring) systems. However, previous works did not investigate the influence of rheological behavior and piezoresistive properties of sustainable cementitious sensors containing red mud (RM) on the strain monitoring of concrete beams. To address this gap, this study presents an experimental analysis of the rheological, mechanical, and self-sensing performance of mortars incorporating carbon black nanoparticles (CBN) and varying levels of RM (25–100% sand replacement by volume), followed by their application in monitoring strain in a reinforced concrete beam under dynamic loading. The results showed that increasing RM content led to higher viscosity and yield stress, with a 60% reduction in consistency index. Compressive strength increased by up to 80%, while mortars with RM content higher than 50% showed high electrical conductivity and reversible resistivity changes under load cycles. Mortars containing 50–100% RM demonstrated improved piezoresistive response, with a 23% increase in gauge factor, and the best-performing sensor embedded in a concrete beam exhibited stable and reversible fractional changes in resistivity, closely matching strain gauge data during dynamic loading conditions. These findings highlight the potential of RM-based smart mortars to enhance sustainability and performance in SHM applications.

1. Introduction

The manipulation of matter at the nanometric scale, achieved through Nanoscience and Nanotechnology, has enabled significant improvements in the performance of a wide range of materials, including mechanical, chemical, electrical, and magnetic properties. This progress has led to the development of multifunctional devices tailored for various engineering applications [1,2]. A notable example is the emergence of smart nanomodified structural components, arising from the creation of multifunctional materials integrated into Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) systems. Within this framework, the development of intelligent cementitious composites stands out, as they possess the intrinsic ability for self-monitoring of stresses and strains, in addition to self-detection of damage [3,4,5,6]. When integrated into structural elements, cement-based sensors can provide a continuous assessment of structural functionality, enabling the evaluation of stress and strain states as well as the identification of compromised regions [7,8].

For the production of these self-sensing composites, it is necessary to incorporate conductive nanomaterials, such as carbon fibers (CF), carbon nanotubes (CNT), and carbon black nanoparticles (CBN), into cementitious matrices until the concentration of these admixtures reaches the so-called percolation threshold, reducing the electrical resistivity of the material [9,10]. At this stage, elastic strains and stresses induce reversible changes in the conductive pathways formed within the cementitious matrix through the piezoresistive phenomenon, resulting in a sensitivity to mechanical variations that enables the evaluation of structural performance and integrity [11,12,13].

The accuracy of electrical measurements in self-sensing composites can be affected by environmental factors such as temperature and humidity, as well as by the presence of metallic reinforcement, especially when using the bulk approach for installing sensors rather than embedded sensors [14,15]. In this context, previous research highlighted the importance of protecting the sensing regions embedded in concrete with an impermeable epoxy interface, showing that long-term exposure to wet conditions can change the electrical properties of self-sensing composites if this protection is not ensured [16,17,18]. Moreover, the presence of reinforcement in concrete can alter the electrical resistivity of concrete, as reinforcement bars can create conductive paths that affect the overall resistivity readings [14,19].

Recent studies have focused on developing self-sensing cementitious composites (SSCC) with the aim of creating elements for structural integrity assessment that are simpler and more cost-effective than conventional SHM technologies available on the market, such as electrical strain gauges, accelerometers, displacement transducers, etc. [20,21,22,23]. Furthermore, some of these studies propose the partial replacement of the binders and/or conventional aggregates in the cementitious matrix with different types of wastes, promoting the recycling and incorporation of these materials into cementitious composites, while also generating smart components with efficient multifunctional performance [24,25,26,27].

In this context, red mud (RM), a solid waste generated on a large scale from the Bayer process—used in alumina production from bauxite ore -, emerges as a promising alternative for incorporation into self-sensing cementitious composites, as it contains metallic compounds that can enhance the electrical conductivity of the cementitious matrix [28]. It is estimated that the annual generation of RM reaches approximately 120–150 million tons, with the accumulated global stock already exceeding 4 billion tons [29,30]. This makes its management a major environmental challenge, particularly due to its highly alkaline nature (pH 10–13) and high content of heavy metals [31,32]. In this regard, its application in the construction sector stands out as a promising strategy to mitigate these impacts, enabling large-scale recycling.

In the literature, studies addressing the use of RM in cementitious composites with a focus on their electrical and piezoresistive properties remain scarce. The electrical resistivity of RM-based concrete with various moisture contents was investigated by Raghu and Kondraivendhan [33]. Specimens containing RM exhibited lower values of electrical resistivity than control specimens without RM. According to the experimental results obtained by Ribeiro et al. [34,35], cement-based materials with RM presented higher values of electrical resistivity in a humid environment than reference samples without waste. After drying procedures, specimens containing RM exhibited values of electrical lower than the control specimens. Previous studies attribute the reduction in electrical resistivity of cementitious composites to the presence of highly conductive ions in RM, such as Na+, OH−, Ca2+, and K+, as well as its high content of metallic oxides, such as Fe2O3, which enhance electrical conductivity in cementitious matrices.

Konkanov et al. [36] investigated the effect of RM contents ranging from 5% to 25% (by binder mass) on the electrical and mechanical properties of mortars. They observed that incorporating 25% RM resulted in an approximately threefold reduction in the electrical resistivity of the composite compared to the reference sample (without RM addition), although this was accompanied by a decrease in compressive strength. However, under cyclic loading, the fractional change in resistivity (FCR) values of the mortar were unstable, rendering the material unsuitable for application as a self-sensing concrete. Correlations between stress, strain and electrical resistivity of mixtures of soil and RM were reported by Salih et al. [37], after exposure to dry-wet cycles. Optimal mixtures containing 77% of RM exhibited changes in electrical resistivity higher than 60%. Zhao and Qiang [32] analyzed the synergistic effect of replacing RM by binder mass (up to 40%) combined with the addition of carbon fibers in cement pastes, evaluating both the mechanical properties and the piezoresistive performance of the material. Their results showed that increasing RM content led to up to a 63% reduction in the electrical resistivity of the pastes, while the highest gauge factor (GF) values were obtained for RM replacement levels of 10% and 20%. Comparisons reported in the literature review article of Nalon et al. [38] indicated that the highest values of FCR were verified in composites containing 25% of RM subjected to compressive stresses around 18 MPa. In addition, the stress sensitivity of RM-based composites ranged between 0.001 MPa−1 and 0.01 MPa−1.

Although recent studies have initiated the investigation of SSCC incorporating varying contents of RM, the state of the art still lacks comprehensive assessments regarding the GF of self-sensing composites containing RM, influence of rheological behavior on their electromechanical performance, the synergistic interactions between RM and CBN, and the applicability and reliability of these composites when embedded in structural elements under dynamic loading. Many existing publications have primarily focused on electrical resistivity, with limited studies reporting gauge factor values, which are critical for quantifying strain-sensing capabilities. To address these research gaps, the present study offers the following contributions: (i) a detailed experimental evaluation of the rheological and electromechanical behavior of cementitious composites incorporating different RM contents; (ii) an analysis of the synergistic effects between RM and CBN on the sensing performance of the composites; (iii) effects of different contents of RM on values of GF of self-sensing cementitious composites; and (iv) a structural-scale test was presented as a case study to explore the strain-monitoring capacity of SSCC embedded in a reinforced concrete (RC) beam subjected to dynamic loading.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

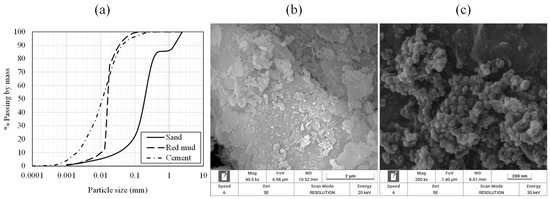

The present study encompasses two research fronts: the evaluation of the effects of different contents of RM on the rheological, mechanical, and piezoresistive properties of SSCC, and the use of RM-based SSCC for strain monitoring in an RC beam subjected to dynamic loading. The materials used in these different research stages included Portland cement CP V-ARI, equivalent to ASTM C150 [39] Type III Portland cement, with a specific mass of 3.05 g/cm3; natural quartz sand with a specific mass of 2.64 g/cm3; RM with a specific mass of 2.76 g/cm3; N234-type CBN supplied by Birla Carbon (Cubatão, Brazil), with a specific surface area of 120 m2/g and an average diameter of 20 nm; a polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer (MC-PowerFlow 4001, Vargem Grande Paulista, Brasil) with a density of 1.12 g/cm3; and a calcium oxide (CaO)-based shrinkage-compensating admixture from Chemica Edile Group Brazil. The chemical composition of the raw materials, obtained by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometry using a Panalytical Epsilon 3x, is presented in Table 1. The particle size distribution curves of these materials, obtained by laser granulometry using a Bettersize2000 analyzer, are shown in Figure 1a.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of the materials used in the research (%). Adapted from Oliveira et al. [40], Copyright 2025, with permission from Springer.

Figure 1.

Characterization of raw materials: (a) particle size distribution curves (adapted from Oliveira et al. [40], Copyright 2025, with permission from Springer); (b) micrograph of red mud (RM) sample and (c) carbon black nanoparticles (CBN) sample obtained by field emission gun scanning electron microscopy (FEG-SEM).

Secondary electron images of RM and CBN samples were obtained via field emission gun scanning electron microscopy (FEG-SEM) using a TESCAN MIRA microscope equipped with a Schottky FEG source (1.2 nm resolution at 30 keV). These samples were mounted on FEG-SEM stubs using double-sided carbon tape and sputter-coated with gold using a Quorum Q150RS equipment. Figure 1b shows that RM consisted of dispersed fine particles with angular and irregular shapes, approximately 1 micron in size, which is consistent with the observations reported by Rai et al. [41] and Ma et al. [42]. Figure 1c indicates that CBN consisted of nano-sized spherical particles forming micrometric aggregates, as previously reported by Lima et al. [12] and Ridaoui et al. [43]. This combination suggests a complementary particle size distribution, which may contribute to a hierarchical conductivity structure within the matrix, potentially enhancing particle connectivity.

To produce the RC beam intended for the subsequent embedding of the SSCC for strain monitoring, the same cement and sand used in the cementitious sensors were employed, along with gneiss-based coarse aggregate with a maximum diameter of 9.5 mm. A multifunctional plasticizer with a density of 1.10 g/cm3 was also used. The reinforcement of the RC beams consisted of CA-50 and CA-60 steel bars. To ensure proper adhesion between the SSCC and the fresh concrete, an epoxy-based bonding agent was applied, as recommended in previous research [13,16].

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Preparation of Self-Sensing Cementitious Composites (SSCC)

To investigate the rheological, mechanical, and piezoresistive performance of the SSCC, different proportions of RM were investigated in this research. Four different series were developed. The control series (REF) was produced with a low RM content (sand/RM ratio of 3, by volume). The remaining series were produced by replacing different amounts of non-conductive aggregates with RM and were designated as 50%RM (sand/RM ratio of 1, corresponding to a 50% replacement of sand with RM, by volume), 75%RM (sand/RM ratio of 0.33, corresponding to a 75% replacement of sand with RM, by volume), and 100%RM (sand/RM ratio of 0, corresponding to a 100% replacement of sand with RM, by volume). Given its fine particle size (Figure 1a), some influence on the workability of the mixtures was expected, particularly at higher replacement levels, due to the increased surface area and potential for higher water demand. Despite these challenges, RM was selected as a sand replacement rather than a cement substitute due to its lack of relevant binding properties, its complementary particle size distribution with natural sand, and the environmental relevance of exploring alternative fine aggregates in sustainable construction.

In each series, five prismatic specimens measuring 2.5 cm × 2.5 cm × 7.5 cm were prepared, each containing a pair of embedded electrodes for electrical resistivity measurement and piezoresistive behavior analysis. Moreover, six cubic specimens with 2.5 cm edges were prepared for compressive strength testing. A water-to-cement ratio of 0.70 (by mass) was used to produce all series of composites, while the nanomaterial-to-cement and superplasticizer-to-cement ratios were set at 0.125 and 0.0625, respectively. These concentrations were selected based on prior experimental investigations conducted by the research group, which aimed to identify an optimal balance between mechanical performance enhancement and electrical conductivity in cementitious matrices with improved dispersion of nanomaterials [12]. The mixture proportions are presented in Table 2. A mixture without RM was not investigated in this research due to excessive fluidity and segregation under identical proportions, and because it would not support the study’s sustainability goals.

Table 2.

Proportions of raw materials used in the production of the self-sensing cementitious composites (SSCC). Adapted from Oliveira et al. [40], Copyright 2025, with permission from Springer.

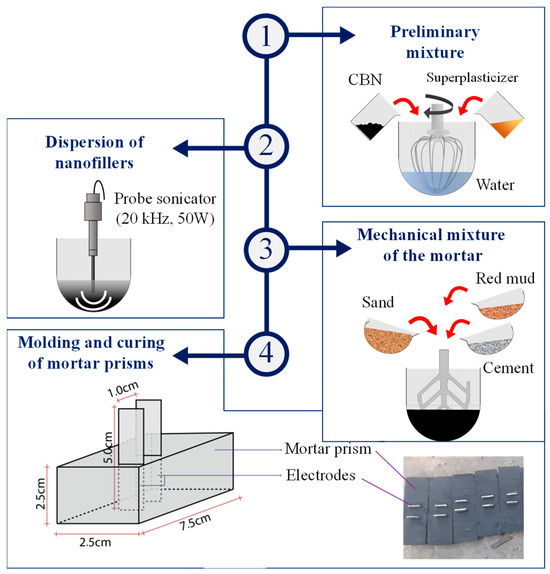

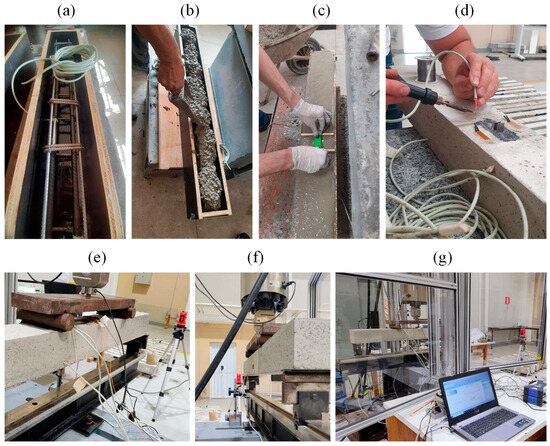

As shown in Figure 2, water, superplasticizer, and CBN were first mixed. Subsequently, the dispersion of the nanomaterials was performed using a probe sonicator operating at 20 kHz and 50 W, with a sonication time proportional to the solution volume (0.08 min/cm3), as adopted by Lima et al. [44]. During this process, the superplasticizer acted as a dispersing agent. Next, the dry mixture composed of cement, RM, and/or sand was gradually incorporated into the solution over a period of 5 min. After 10 min of continuous mixing, the resulting fresh mortar was cast into prismatic and cubic molds previously covered with a thin layer of mineral oil and subsequently compacted on a vibrating table for 10 s. During the casting stage, five prismatic specimens were instrumented with two Kanthal KA1 electrodes positioned with a spacing of approximately 1 cm and measuring 1.5 cm × 5 cm × 0.15 cm. After casting, the specimens were subjected to wet curing for 28 days at 23 ± 2 °C, followed by heating in an oven at 50–70 °C for 5 days and cooling to room temperature to minimize potential interferences from ionic conduction during the electromechanical tests [45,46].

Figure 2.

Procedures for manufacturing the self-sensing cementitious composites (SSCC).

2.2.2. Rheological Behavior Assessment

Rotational Rheometry Test

The rotational rheometry tests were conducted using a Couette-type rotational rheometer (Schleibinger, Viskomat NT model), whose measurement system consists of a fixed probe positioned concentrically with respect to a cylindrical container. Immediately after mixing, the fresh mortar was poured into the cylindrical container, with a nominal volume of 375 mL. A probe specific for mortars (model V0011) was used in these experiments. During the test, the torque resulting from the shear force was continuously monitored as the material flowed around the probe [47].

The same experimental procedure used by Carvalho et al. [48] was used, with minor adaptations to meet the specific requirements of the present study: initially, the rotational speed was increased from 0 to 240 rpm over 30 s; then, the 240 rpm plateau was maintained for 600 s to stabilize the system; finally, the speed was decreased back to 0 rpm over 30 s, at which point torque and rotational speed measurements were performed.

Among the rheological models widely used to describe the flow behavior of cementitious composites, the Bingham, Herschel–Bulkley, and Modified Bingham models stand out due to their ability to satisfactorily represent the mechanical response of these materials under different shear conditions [47]. In this study, the Bingham model was chosen, as it provided the best fit to the rheological behavior of the sensing mortars, as indicated by the correlation coefficients obtained. According to this model, the material behaves as an ideally plastic fluid: flow only begins after exceeding a minimum stress, referred to as the yield stress (τ0), from which a linear relationship between shear stress and shear rate is established, similar to that observed in Newtonian fluids [49].

The torque and rotational speed values were qualitatively correlated with shear stress and shear rate, respectively, following the approach described by Vasiliou [50] and Carvalho et al. [48]. This strategy enabled the qualitative analysis of variations in viscosity and yield stress through the slope (angular coefficient) and the vertical-axis intercept of the flow curve (Torque × Rotational Speed), respectively. Equation (1) represents the Bingham model and the described behavior, where τ corresponds to the shear stress [Pa],

to the plastic viscosity [Pa·s], and to the shear rate [1/s].

Mini-Flow Test

The consistency index was determined through the mini-slump test using a Kantro-type truncated cone mold (top internal diameter of 19 mm, base internal diameter of 38 mm, and height of 57 mm). The mold was positioned at the center of the flow table and filled with fresh mortar in three equal portions. Each portion received 15, 10, and 5 tamping strokes, respectively. After filling, the mold was removed vertically, allowing the material to spread. Subsequently, the flow table was used to perform 30 drops from a height of 12.5 mm over a 30 s interval. The consistency index was calculated based on the average of the diameters measured in three different directions across the flow table surface.

2.2.3. Compressive Strength Test

The dimensions of each cubic specimen were measured, enabling the calculation of the cross-sectional area responsible for bearing the compressive load in the uniaxial compression test. Each specimen was then centrally positioned on the steel plates of the mechanical press and subjected to a monotonic compressive loading. Loading continued until a sudden drop in the force reading occurred, indicating the failure of the specimen. The maximum force recorded immediately before failure was recorded. Using the load application area, the compressive strength of each specimen was calculated.

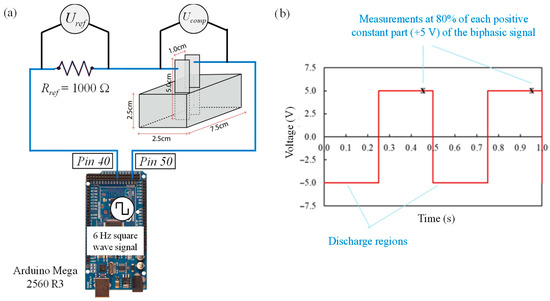

2.2.4. Electrical Resistivity Test

The initial electrical resistivity of the specimens, corresponding to the unloaded state, was determined using the biphasic direct current (DC) method proposed by Downey et al. [51], as a replacement for the conventional DC procedure, in order to minimize potential polarization effects. For signal generation, an Arduino Mega 2560 R3 board was programmed to produce a periodic square wave with a frequency of 6 Hz, voltage of ±5 V, and a duty cycle of 50%, as reported in previous studies [13,52]. The experimental setup is illustrated in Figure 3a.

Figure 3.

Experimental setup of electrical resistivity tests (a), using a periodic square wave voltage signal (b). Adapted from Oliveira et al. [40], Copyright 2025, with permission from Springer.

Following the methodology reported in previous studies [13], pins 40 and 50 of the Arduino board were used to apply the periodic signal to the specimen and to a reference resistor, connected in series (Figure 3a). Voltage drop measurements across the composite (Um) and the reference resistor (Uref) were performed at instants corresponding to 80% of the total duration of each positive half-wave (Figure 3b), using a National Instruments cDAQ-9178 chassis equipped with two NI-9219 modules and the LabVIEW software. The electric current i (A) was determined as the ratio between Uref (V) and the resistance of the reference resistor (Rref = 1000 Ω), while the electrical resistance of the composite Rm (Ω) was obtained by dividing the voltage Um by the current i (A). The electrical resistivity of the material ρ (Ω·cm) was calculated by multiplying Rm (Ω) by the effective area between the electrodes A (cm2) and dividing the product by their spacing (cm).

2.2.5. Evaluation of the Piezoresistive Behavior

The evaluation of the piezoresistive behavior of the cementitious composites was carried out by monitoring the electrical resistivity during loading and unloading cycles, using the biphasic DC method. To define the load levels, one prismatic specimen from each experimental series was selected for the estimation of the uniaxial compressive strength (fu), which served as the reference for the execution of the cycles. Subsequently, the electrical resistivity of the remaining four specimens was again determined during the piezoresistive tests, which consisted of two stages: (i) cyclic uniaxial loading, comprising three loading–unloading cycles up to 30% of fu, with each load step maintained for 15 s; and (ii) application of uniaxial loads within the elastic–linear regime, corresponding to 10%, 20%, and 30% of fu, followed by unloading, with each load step applied for 15 s. Longitudinal strains were recorded using clip-gauge (model EE08, EMIC) during the piezoresistive tests. The FCR, along with the strain and compressive stress readings, was employed to calculate the GF for each specimen, obtained from the slope of the FCR versus strain curve.

2.2.6. Case Study: Concrete Beam Containing SSCC Under Dynamic Loading

SSCC Embedded in the Concrete Beam

With the aim of monitoring strains in a RC beam, additional SSCC were produced using the replacement level with RM that exhibited the best self-sensing performance, as discussed in Section 3.1.4. The mortar mix corresponding to this replacement level was replicated, maintaining a water-to-cement ratio of 0.70 and a nanofiller-to-cement ratio of 0.125. In addition, to control composite shrinkage during the curing process after embedding in the beam, a shrinkage-compensating admixture was incorporated into the mix at 6% of the cement mass.

For the fabrication of the SSCC, the same procedures described in Section 2.2.1 were followed, except that casting was not performed in prismatic molds, but directly in the space previously reserved within the beam, with dimensions of 2.5 cm × 2.5 cm × 7.5 cm. To ensure appropriate adhesion and mitigate environmental effects on the electrical response, an epoxy layer was applied between the SSCC and the concrete substrate [16,17]. In addition, the embedded sensor approach was adopted instead of the bulk installation method [14,18], which minimizes the influence of steel reinforcement on electrical measurements, ensuring more reliable and accurate sensing results. During casting, while the mortar was still in the fresh state, two Kanthal KA1 electrodes of 1.5 cm × 5 cm × 0.15 cm, were embedded with an approximate spacing of 1 cm between them. After casting, the assembly (beam + SSCC) was placed in a moist curing chamber, maintained at a relative humidity above 85% and a controlled temperature of 20 ± 5 °C, where it remained for 28 days. After this period, the assembly was removed from the curing chamber and stored under ambient conditions until the experimental tests were performed.

Concrete Mix Proportions

For the production of the RC beam containing the SSCC for strain monitoring, a concrete with a characteristic compressive strength of 30 MPa was used, with the mix proportions presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Concrete mix proportions and slump value (kg/m3).

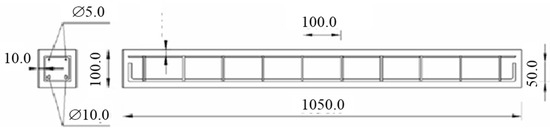

Steel Reinforcement

The beam was designed to exhibit a failure mode characterized by excessive deformation of the steel reinforcement. The experimental model was produced with nominal dimensions of 10 × 10 × 105 cm, with an effective span of 100.0 cm in the four-point bending test. The longitudinal tensile reinforcement consisted of two CA-50 steel bars with a diameter of Ø10.0 mm. The longitudinal compressive reinforcement consisted of two CA-60 steel bars with a diameter of Ø5.0 mm. For the transverse reinforcement, CA-60 bars with a diameter of Ø5.0 mm were used, spaced at 10.0 cm intervals. The concrete cover to the steel reinforcement was 1.0 cm. Figure 4 shows the steel reinforcement of the experimental model. The yield and ultimate strengths of the steel bars are presented in Table 4.

Figure 4.

Steel reinforcement positions of the beam experimental model (dimensions in millimeters).

Table 4.

Properties of the steel bars used in the experimental model.

RC Beam Production

To monitor strains in the steel reinforcement during the bending tests, a strain gauge (SG-T) with a GF of 2.16 was installed at the central region of each of the Ø10.0 mm tensile bars. Prior to the production and casting of the beams, the transverse and longitudinal reinforcements, as well as the stirrups, were carefully positioned and tied within the formwork, using spacers to ensure an adequate concrete cover of 1 cm between the concrete surface and the reinforcement.

Before casting, the formwork was cleaned, and a release agent was applied to the internal surfaces. A C30-class concrete was prepared, with the mix proportions presented in Table 3. With the reinforcements properly positioned within the formwork, the concrete was poured and then consolidated on a vibrating table for 10 s. To create a space for the subsequent embedding of the SSCC for strain monitoring, a prismatic spacer with dimensions of 2.5 cm × 2.5 cm × 7.5 cm was used. This spacer was inserted into the fresh concrete until its surface was flush with the concrete surface, thus creating the required opening. Figure 5 illustrates the sequence of steps for the beam production.

Figure 5.

Procedures for beam production and testing: (a) preparation of the formwork and steel reinforcement; (b) concrete casting; (c) placement of spacer; (d) installation of the self-sensing region and conventional strain gauges; (e) alignment of the beam in the testing machine; (f) positioning of the LVDTs; (g) assembly of data acquisition systems.

Next, the experimental model was kept moist for 48 h, covered with a plastic sheet. Then, the specimen was demolded and stored in a curing chamber at a relative humidity above 85% and a temperature of 20 ± 5 °C until reaching 28 days. After this period, the beam was removed from the curing chamber and stored under ambient conditions until the production and casting of the SSCC were carried out.

Finally, to mitigate potential ionic conduction effects during the strain monitoring tests, the assembly consisting of the beam and the SSCC was subjected, prior to the bending test, to oven drying at approximately 65 °C for 72 h, followed by cooling until reaching ambient temperature.

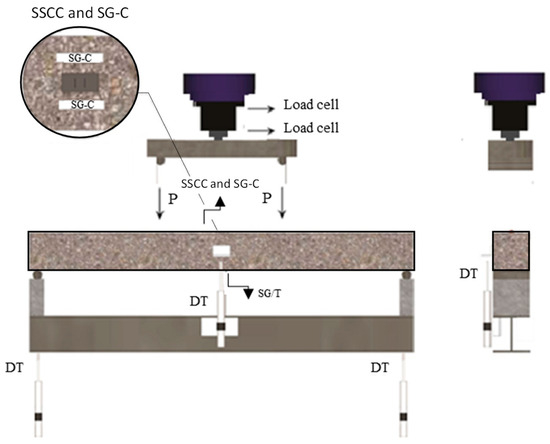

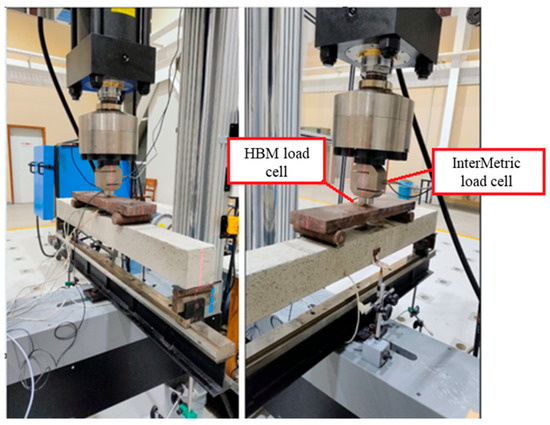

Experimental Setup of Dynamic Bending Tests

For the application of dynamic loading, the assembly (beam + SSCC) was positioned along the axis of an InterMetric universal testing machine, model IM-750, on a pre-installed steel reaction beam. The cementitious sensor was located at the midspan on the upper face of the beam to monitor the compression zone during loading. Using a four-point bending test configuration, the beam was subjected to cyclic loading at 20 cycles/min. The load application points were located 30.0 cm from the axis line of the supports. A displacement transducer (DT) HBM, model WA20, was positioned at the midspan of the beam to record deflection throughout the test. At the ends of the reaction beam, two additional DTs of the same model were also installed to monitor any undesired movement, allowing compensation if necessary. Furthermore, two commercial concrete strain gauges (SG-C) with a GF of 2.15 were attached to the top surface at the midspan of the beam, enabling the monitoring of strains and comparison with SSCC measurements. Between the actuator of the universal testing machine and the beam, an HBM load cell, model C9C, with a capacity of 50 kN was installed. This configuration allowed monitoring and recording of the applied load throughout the test. Data acquisition from the load cell, strain gauges (for steel and concrete), and DTs was performed using an HBM Quantum X system with MX840A and MX1615 modules, linked to the Catman data acquisition software. The InterMetric universal testing machine was controlled via Tesc software implemented on the integrated computer, enabling automated control of the load cycles throughout the test. Figure 6 and Figure 7 illustrate the experimental setup used in the bending tests of the RC beams.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the bending tests of the self-sensing beam.

Figure 7.

Experimental setup used in the bending tests of the self-sensing beam.

Loading History

The dynamic test conducted in the present study aimed to explore the mechanical behavior of the structural element by correlating the strains recorded by conventional electrical strain gauges with the FCR measurements obtained from the SSCC. The objective was to understand the behavior and performance of the SSCC when the structural element is subjected to dynamic loading.

Thus, the loading history of the beam consisted of a dynamic analysis test configured in the Tesc software, applied as 100 cycles at a rate of 20 cycles/min. The loading amplitude was chosen based on the load capacity of a similar beam tested in preliminary laboratory studies, characterized by a lower limit of 3.80 kN, corresponding to 10% of the material’s ultimate load, and an upper limit of 9.50 kN, equivalent to 25% of this load. This loading range was defined to ensure that the material remained within the elastic regime during the tests.

To evaluate the piezoresistive response during the dynamic tests, the electrical resistivity of the SSCC embedded into the RC beam was measured using the biphasic DC method proposed by Downey et al. [51]. An Arduino Mega 2560 R3 generated a 6 Hz square wave signal (±5 V, 50% duty cycle) applied to the SSCC and a reference resistor connected in series, as indicated in Figure 3. Measurements of Um and Uref were taken at 80% of each positive half-cycle using a National Instruments cDAQ-9178 system with NI-9219 modules and LabVIEW. These values were used to calculate values of i, Rm, ρ, and FCR of the SSCC during the dynamic loading test, as indicated in Section 2.2.4.

The HBM Quantum X system was configured for a data acquisition rate of 5 Hz, while the LabVIEW software acquired the electrical response of the SSCC at approximately 2 Hz, being linked to the National Instruments cDAQ-9178 chassis. Due to the difference in data acquisition frequencies between these systems, time synchronization of the data acquisition was necessary to obtain and compare the strain results from the strain gauges installed on the steel and concrete, as well as from the transducers, with the FCR measurements in the piezoresistive test.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. SSCC Investigations

3.1.1. Rheological Behavior

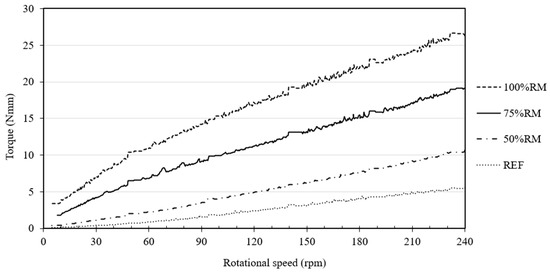

Rotational Rheometry Results

Figure 8 presents the results of the rotational rheometry measurements (Torque × Rotational Speed) of composites with different contents of RM. The replacement of sand with RM had a clear effect on the slope of the Torque × Rotational Speed curves, suggesting an increase in the viscosity of the sensor mortars as the RM replacement level increased. This behavior is possibly associated with the introduction of particles significantly finer than sand into the matrix, which leads to a substantial increase in the specific surface area of the system. Such an increase promotes greater water absorption by the RM particles, reducing the amount of free water available in the system and impairing the lubricating effect between particles, thereby increasing internal friction and, consequently, the plastic viscosity of the material. This behavior was also observed when RM replaced coarser materials with lower specific surface area in the cementitious matrix [53].

Figure 8.

Rheological behavior of cementitious composites with different levels of RM. Adapted from Oliveira et al. [40], Copyright 2025, with permission from Springer.

Indeed, when observing the slope of the Torque × Rotational Speed curve of the reference series, no pronounced steepness is noted compared to the other series, indicating that the present RM content at this level was still insufficient to increase the specific surface area of the system to a point that, under the same water/cement ratio and superplasticizer dosage as the experimental series, would impair particle lubrication due to the limited free water available in the matrix and alter the effectiveness of the superplasticizer. On the other hand, for higher replacement levels, such as 50%, 75%, and 100% RM, a considerable increase in the slope of the curves is observed, suggesting an increase in the material’s viscosity. This behavior indicates that, at these replacement levels, the increase in specific surface area becomes significant enough to primarily reduce the availability of free water in the system, compromising the material’s plasticity.

Analyzing the trend of the intersection point of the curves with the ordinate axis, it can be observed that all experimental series exhibit values close to zero. Only the 75% and 100% RM replacement levels show slightly higher values, on the order of 2.4 N·mm and 4.8 N·mm, respectively. According to Carvalho et al. [48], this behavior may be associated with the action of superplasticizer particles in the system. In this context, the increase in specific surface area resulting from the higher incorporation of fine RM particles tends to increase the demand for superplasticizer, as there is more surface to be coated by the additive. This condition reduces the effective concentration of molecules available to act on the cement and RM grains, hindering particle repulsion and compromising additive efficiency, which can directly affect the initial flow resistance of the composites. Considering the observed relationships, this behavior may explain the increases in the ordinate intercept, as well as influence the material’s viscosity. This indicates that, for experimental series with high RM replacement levels, a potential increase in superplasticizer dosage could contribute to a reduction in initial flow resistance and, consequently, increase the consistency index, thereby improving the workability of the SSCC.

In an analysis of the possible influences of rheological behavior on the sensing properties of the SSCC, it can be observed that the increase in viscosity of the sensor mortars at higher levels of sand replacement by RM, as well as the increase in initial yield stress, is accompanied by a significant reduction in the consistency index of these mortars, as discussed in Section “Consistency Index”. This overall reduction in rheological performance leads to difficulties in molding and consolidation processes, as identified during the production of the SSCC specimens, which has the potential to compromise the full establishment of the conductive network within the cementitious matrix. Consequently, a greater variability in the GF within the same experimental series can be observed, possibly caused by this effect, generating a sense of uncertainty in quantifying the sensor response of the mortars, although, in individual analyses, good sensing performance is identified at certain RM replacement levels, as reported in Section 3.1.4.

Furthermore, the viscosity of the cementitious composite can affect the precise positioning of the electrodes during the embedding process, compromising the quality of the interface between the electrodes and the matrix. This problem may negatively influence the measurement of piezoresistive behavior, impacting the cementitious sensor’s performance when embedded in a structural element, as discussed in Section 3.2.

Consistency Index

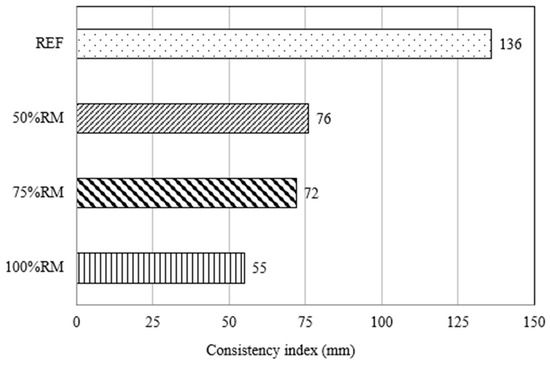

Figure 9 presents the effects of replacing natural aggregates with RM on the consistency index of the mortars. It was observed that, as the replacement level in the reference series increased to 100% RM, the consistency index decreased by approximately 60%.

Figure 9.

Consistency index of cementitious composites with different contents of RM. Adapted from Oliveira et al. [40], Copyright 2025, with permission from Springer.

The pronounced decrease in the consistency index of the mortars, caused by the replacement of natural aggregates with RM, can be attributed to the high water absorption of the RM particles, which have a considerably larger specific surface area and finer granulometry than sand. This effect compromises particle lubrication in the fresh mixture, resulting in reduced flowability. Similarly, Shi et al. [47] also reported that the fine granulometry of RM led to a decrease in the consistency index of self-sensing cementitious matrices.

The effects of this reduction in consistency were directly observed during the molding and consolidation procedures of the SSCC specimens. In the case of the 100% RM replacement level, the sensor mortar exhibited low flowability, making specimen molding and sensor embedding difficult, which may have caused incomplete filling of the molds and compromised the quality of the interface between the electrode and the cementitious matrix. In contrast, the reference series exhibited a consistency similar to that of a self-compacting material, facilitating molding, with problems observed only during the electrode positioning and fixation stage.

3.1.2. Compressive Strength

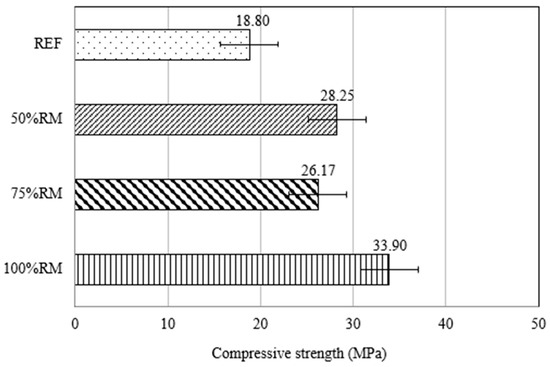

Figure 10 illustrates the effect of replacing aggregates with RM on the compressive strength of the mortars. It was observed that, as the replacement level in the reference series increased to 100% RM, the average compressive strength increased by approximately 80%.

Figure 10.

Results of compressive strength of cementitious composites with different contents of RM. Adapted from Oliveira et al. [40], Copyright 2025, with permission from Springer.

The increase in compressive strength observed with the incorporation of RM may be related to the choice of maintaining a constant water/cement ratio (0.70) in all cementitious composites. This water content was sufficient to ensure effective hydration of the cement grains in the 100% RM composite, even after significant water adsorption by the RM particles due to their high specific surface area. In composites with lower RM contents, the presence of a greater amount of free water in the matrix may have increased the void index, reducing compressive strength. Increases in strength were also reported by [54], who attributed the strength gain in RM mortars to the reduction in apparent porosity caused by the particle packing effect provided by the material.

The analysis of the variation in compressive strength results, considering samples from the same experimental series, indicated that the REF mix exhibited the smallest error bar, whereas the 100% replacement mix showed the greatest variability in measured values. This difference in dispersion can be attributed to the rheological characteristics of the sensor mortars and the material’s consistency index, as discussed in Sections “Rotational Rheometry Results” and “Consistency Index”, respectively. Mortars with lower RM replacement levels exhibited reduced viscosities and yield stresses, as well as a lower consistency index, which promoted behavior close to self-compacting. This characteristic is important to ensure adequate material flow during molding, allowing the composite to uniformly fill the mold, reduce internal voids, and promote homogeneous distribution of the constituents. Such homogenization directly contributes to microstructural uniformity and, consequently, to the repeatability of compressive strength results among specimens from the same experimental series. In contrast, the 100% RM replacement mix showed a significant increase in viscosity and yield stress, along with a decrease in the consistency index, reflecting a stiffer rheological behavior that is difficult to handle during molding. This higher viscosity hinders uniform mold filling and proper consolidation of the sensor mortar, increasing the likelihood of internal voids and heterogeneities. These imperfections may compromise the microstructural integrity of the composite, resulting in greater dispersion in compressive strength values within the same experimental series.

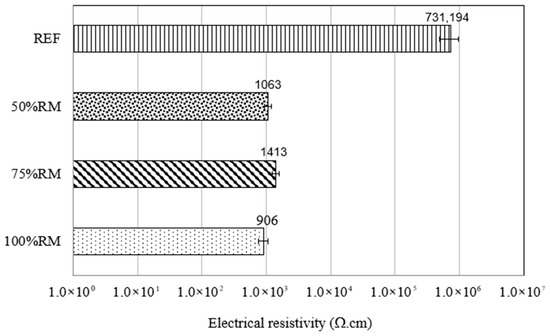

3.1.3. Electrical Resistivity

Figure 11 presents the electrical resistivity results of the mortars with different levels of natural aggregate replacement by RM. It was observed that the specimens of the REF series exhibited high electrical resistivity values, ranging from 3.2 × 105 Ω·cm to 9.7 × 105 Ω·cm. Such high levels of electrical resistivity are frequently observed in relatively dry cementitious materials, in which the amount of conductive additions is insufficient to establish an efficient electronic conduction network within the matrix [55,56].

Figure 11.

Results of electrical resistivity of cementitious composites with different contents of RM. Adapted from Oliveira et al. [40], Copyright 2025, with permission from Springer.

In contrast, when the RM replacement percentage was increased (in the 50%RM, 75%RM, and 100%RM series), the produced mortars exhibited highly conductive behavior, with electrical resistivity values ranging from 7.4 × 102 Ω·cm to 1.6 × 103 Ω·cm, up to three orders of magnitude lower than those observed in mixtures with lower levels of the residue.

The results indicate that the synergy between the CBN and higher proportions of RM enabled the composites to reach the material’s electrical percolation threshold. The low resistivity observed in the mortars of the 50%RM, 75%RM, and 100%RM series can be explained by the simultaneous action of two processes: electronic conduction and contact conduction established between the CBN and the conductive particles present in the residue. According to Han et al. [18], electronic conduction is related to the quantum tunneling effect, in which electrons traverse small insulating gaps in the matrix between neighboring conductive particles. In turn, contact conduction results from the direct passage of electrons between adjacent particles in physical contact.

The improvement in electrical conductivity resulting from the use of high RM contents may be related to the composition of the residue, which contains conductive particles and ionic species. Ribeiro et al. [57], for example, identified the presence of ions with high conductive character, such as Na+, OH−, Ca2+, and K+, while Konkanov et al. [36] and Shi et al. [47] attributed the conductive nature and potential of RM to its relatively high content of metallic oxides, among which Fe2O3 stands out.

3.1.4. Piezoresistive Behavior

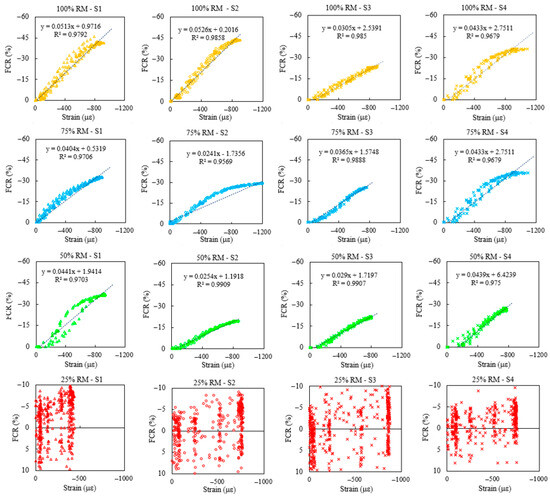

The piezoresistive characterization of the cementitious composites was conducted through the analysis of electrical resistivity variation during loading and unloading cycles, using the biphasic DC procedure as proposed by Downey et al. [51]. Figure 12 shows the FCR curves as a function of compressive strain, along with the linear regressions that provided the best fit to the experimental results, accompanied by the determination coefficient (R2) values corresponding to each specimen.

Figure 12.

Piezoresistive response of cementitious composites with different contents of RM. Adapted from Oliveira et al. [40], Copyright 2025, with permission from Springer.

The results indicated that only the mortars of the REF series did not exhibit piezoresistive behavior. As discussed in Section 3.1.3, no electronic conduction mechanisms were identified in the specimens of this experimental series, as they exhibited high electrical resistivity. Consequently, the specimens of this series did not demonstrate satisfactory electrical performance for SHM applications.

The specimens of the 50%RM, 75%RM, and 100%RM series exhibited regular and reversible electrical resistivity variations under loading/unloading cycles. According to Section 3.1.3, these composites contained a quantity of conductive additions above the material’s percolation threshold, which enabled the formation of deformation-sensitive conductive pathways. Accordingly, compressive stresses modified the distances between the conductive particles of RM and CBN, producing measurable changes in electrical resistivity. These results highlight the potential of these composites to act as sensing materials for the self-monitoring of the mechanical behavior of concrete elements.

Figure 13 presents the average GF values, calculated from the slope of the linear segment of the FCR versus strain curves, according to the recommendation of Chung [4]. GF values were not determined for the REF series, as no coherent piezoresistive response was observed in the specimens of this series.

Figure 13.

Results of gauge factor of cementitious composites with different contents of RM. Adapted from Oliveira et al. [40], Copyright 2025, with permission from Springer.

The analysis revealed that the incorporation of RM enhanced the self-sensing capability of the cementitious composites. This effect can be attributed to the alterations induced by RM in the conductive network within the cementitious matrix. In the initial stages of the percolation zone, the piezoresistive behavior is primarily associated with tunneling mechanisms between adjacent conductive particles [14,58]. Increasing the RM replacement from 50% to 75% did not result in significant improvements in self-sensing properties, as the average GF value remained practically unchanged. On the other hand, increasing the replacement from 75% to 100% raised the number of RM conductive particles intercalated between the CBN, expanding the number of tunneling gaps in the cementitious matrix and resulting in an approximately 23% increase in the average GF. Moreover, when conductive admixtures replace part of inert aggregates, they are incorporated within the cementitious matrix where the hydration products grow and develop around their high specific surface areas. The cement hydration crystals nucleate and form interlocking structures on the surfaces of conductive particles, facilitating the formation of conductive networks within the cementitious composite [13]. This microstructural integration enables more effective electron transport and thus better sensing response. Consequently, the 100%RM series demonstrated the best self-sensing response.

Within the same experimental series, a significant variation in GF values of the sensing mortars is observed. This fluctuation may be related to factors compromising the homogeneity of the composite and the quality of the interface between the electrode and the cementitious matrix, possibly resulting from difficulties in the molding and compaction processes, which in turn reflect the material’s rheological behavior. As reported in Section 3.1.1, challenges were observed during the embedding of the electrodes in the mortars during the molding process. Considering that the measurements of FCR, adopted in the methodology of this research, depend directly on the distance and effective contact area between the electrodes, any disturbance in the positioning of these elements within the same experimental series—such as parallelism, spacing, inclination, and contact area with the cementitious matrix—may affect the standardization of the results obtained. This effect becomes even more sensitive as it involves phenomena occurring at the nanometric scale, which likely amplifies the impact of small geometric variations on the measured electrical response among specimens of the same series.

For the mixes that reached the percolation threshold and exhibited good piezoresistive performance, the sensing response, when analyzed individually, is not compromised. However, among the replicated specimens of the same series, variability is observed, which may generate uncertainty regarding the reproducibility of the sensing response for that mix. This behavior suggests that, in mixes with sand replacement levels by RM above 50%—which demonstrated satisfactory sensing performance—those with lower slopes in the Torque × Rotation Speed curve (indicative of lower viscosity, as shown in Figure 8) tend to favor the molding, compaction, and electrode embedding processes. Thus, provided that the positioning and fixation of these electrodes are standardized, this condition may result in GF values with lower variability among specimens of the same mix, yielding more reliable SSCC replications.

Alternatively, it is considered that increasing the superplasticizer content in these mixes may contribute to reducing the viscosity and yield stress of the material, thereby similarly favoring the molding and proper accommodation of the electrodes, without compromising the quality of the matrix–electrode interface. Thus, it is possible that an optimized dosage exists, combining the RM replacement levels and superplasticizer content, which simultaneously provides good rheological behavior and a consistent sensing response.

3.2. Investigations on RC Beam Containing SSCC

For deformation monitoring in an RC beam using SSCC, the mix with 100% RM replacement was used in this research, as it offered the best overall balance of properties relevant to SSCC, as summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Comparative analysis of key properties of the mixtures evaluated in this research.

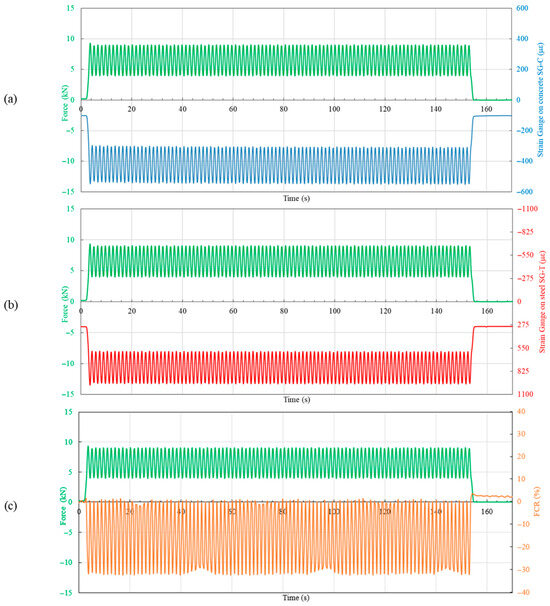

In addition, the strain values in the steel and concrete (in με) of the RC beam were obtained during the dynamic tests, as well as the displacements at the three points of the beam where the DTs were installed (in mm). The piezoresistive response of the SSCC was also recorded, including the FCR over time. Accordingly, the corresponding graph for the dynamic analysis was generated, and the data obtained were analyzed. The applied load in the loading/unloading cycles, the average strain of the steel and concrete, and the FCR values of the composite were plotted as a function of time for each scenario. The graph corresponding to the results obtained from the dynamic analysis is presented in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Results of the dynamic analysis: (a) Average concrete strain vs. applied load in the loading/unloading cycles over time, (b) Average steel strain vs. applied load in the loading/unloading cycles over time, (c) FCR vs. applied load in the loading/unloading cycles over time.

The results demonstrated that the dynamic loading applied during the test induced a clear cyclic behavior, reflected in both the average strain of the concrete and the average strain of the steel. For the average concrete strain, a slight trend of increasing maximum strain amplitude was observed as the number of applied cycles increased, ranging from 529 με to 551 με. This effect is primarily associated with the structural element’s accommodation during the initial applied load cycles.

By examining the FCR values throughout the test, it can be observed that the behavior of the cementitious sensor follows the variations in force and strain measured by the commercial electrical extensometers, demonstrating a satisfactory sensing performance of the material under dynamic analysis. It is also noted that during each unloading stage, the material’s electrical resistivity recovers, indicating an appropriate piezoresistive performance of the cementitious sensor.

However, at the end of the dynamic analysis, when the beam was completely unloaded, a positive FCR value (3.08%) was observed, indicating that the final electrical resistivity of the SSCC did not return to its initial value. This behavior may be associated with variations in the quality of adhesion between the electrodes and the cementitious sensor during the application and removal of the pre-load (at the beginning and end of the test, respectively), resulting in an electrical accommodation of the sensor. It is thus assumed that, at initial loading levels, the contact between the electrode and the matrix is not fully established, possibly due to a flaw in the molding process of the assembly (Section 3.1) which would compromise the proper transfer of the electrical signal. With increasing load, the material undergoes accommodation, favoring the effective establishment of the interface and, consequently, the initiation of the composite’s electrical response. During unloading, this interface is affected, losing full contact between components again, resulting in FCR values that are not consistently correlated with the average strains in the concrete and steel. Moreover, this effect may also be influenced by potential mechanical accommodation between the SSCC and the RC beam, due to deficiencies in the bonding layer between the materials.

Furthermore, throughout the loading/unloading cycle, even after the load was reduced to the pre-load level, it was observed that the FCR variations returned to the initial electrical resistivity of the composite, thus not exhibiting a consistent correlation with the average strains in the concrete and steel—which, at this loading level, remain different from zero and, under ideal conditions, should result in FCR values distinct from those at the initial stage.

In another analysis, it can be observed that the maximum FCR values measured throughout the test gradually increased, ranging from 29% to 32.4%. This electrical response follows the increase in the maximum average concrete strains during the tests, since the compressive stress acting in the region where the strain gauges were attached to the concrete is close to that where the cementitious sensor was embedded. This indicates that the deformations induced in the structural element caused a rearrangement in the conductive network of the sensor material in the dry state, opening and closing conductive paths between CBN and RM particles and, consequently, altering the electronic conduction mechanisms, which resulted in changes in the electrical resistivity of the cementitious composite during the dynamic tests.

However, throughout the dynamic test, peaks of reduction in FCR amplitude were observed, followed by increases in these values, repeating at intervals of approximately 50 s during the test (around 17 cycles). This caused the FCR values to also exceed zero in the graphs, as if a plastic residual deformation occurred in the material, even within the elastic regime, which was not sustained. The nature of this atypical behavior suggests the presence of factors in the experimental conditions that temporarily influenced the response of the cementitious sensor. This may be related to electromagnetic interference phenomena in the experimental setup for the piezoresistive test, involving all the equipment used to measure strains and displacements, as well as possible abnormal operation of the Arduino Mega 2560 R3 board, responsible for generating the periodic square-wave signals. These hypotheses, however, were not investigated in the present work and constitute potential lines of research for future studies.

4. Conclusions

The rheological, mechanical, and self-sensing properties of the mortars investigated in this study highlight the significant potential of RM for promoting eco-efficiency in cementitious matrices and in the production of self-sensing composites. Furthermore, the application of the self-sensing cementitious composite incorporating RM in the analysis of the mechanical behavior of an RC beam demonstrates the promising potential of the developed SSCC for structural monitoring, evidencing its capability to detect strain variations through the piezoresistive response under dynamic testing. The following conclusions were drawn from the present study:

- The incorporation of RM into the cementitious matrix resulted in an increase in the plastic viscosity and yield stress of the sensing mortars, while reducing the consistency index, as the substitution level of natural aggregates in the REF series (25% RM) was raised to 100% RM. This behavior can be attributed to the high water absorption and fine particle size of RM compared to sand particles.

- The replacement of natural aggregates with RM also altered the electrical resistivity of the cementitious composites. While mortars produced with a 25% replacement level exhibited the typical behavior of insulating materials, composites with replacement levels of 50%, 75%, and 100% displayed high electrical conductivity. This behavior may be associated with the presence of conductive particles in RM, which promoted a greater refinement of the electronic conduction network within the cementitious matrix.

- Piezoresistive tests indicated that only mortars with 50%, 75%, and 100% replacement levels exhibited consistent and reversible variations in electrical resistivity under mechanical loading cycles. Increasing the aggregate replacement level with RM from 50% to 100% enhanced the self-sensing capability of the composites, as evidenced by an approximate 23% increase in the GF.

- For dynamic tests involving up to 100 loading cycles on an RC beam, conducted within the elastic regime, the SSCC exhibited satisfactory sensing behavior. The FCR values of the sensing composite showed reversible behavior throughout the loading/unloading cycles, with a cyclic pattern consistent with the deformations recorded by conventional electrical strain gauges attached to the structural element. However, a moderate hysteresis was observed in the electrical signal at the end of the dynamic analysis test.

For a more comprehensive understanding of the results obtained in this study, future investigations are recommended to explore the effects of partial sand replacement with RM in SSCC, considering different water/cement ratios, CBN contents, and optimized proportions between RM and superplasticizer, which simultaneously enhance the rheological, mechanical, and piezoresistive performance of the composite, aligning these properties with the principles of eco-efficiency applied to cementitious materials. Although the results are promising, they are based on an RC beam case study and therefore represent an initial assessment that cannot be generalized without further experimental validation. For example, it is suggested to expand the experimental analysis by testing a larger number of specimens under dynamic loading with increased cycle counts and varied frequency ranges, as well as under static loading conditions. Moreover, future research is recommended to develop and validate in situ measurement techniques for concrete beams incorporating self-sensing cement, with a particular focus on compensating for variations in electrical outputs caused by changing environmental conditions such as temperature and humidity. Finally, the need to investigate the attenuation peaks of FCR amplitude observed during dynamic tests is highlighted, proposing the analysis of potential electromagnetic interferences and the operation of the Arduino board, aiming to understand their effects on the accuracy and reliability of piezoresistive measurements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.R.O., G.H.N., G.E.S.d.L. and L.G.P.; methodology, H.R.O., G.H.N., G.E.S.d.L., L.G.P., J.C.L.R., J.M.F.d.C. and A.M.d.S.; validation, L.G.P., J.C.L.R., J.M.F.d.C., R.A.F.P. and D.S.d.O.; formal analysis, H.R.O., G.H.N., G.E.S.d.L. and L.G.P.; investigation, H.R.O., G.H.N., G.E.S.d.L., and A.M.d.S.; resources, L.G.P., J.C.L.R., J.M.F.d.C., F.A.F. and R.A.F.P.; data curation, H.R.O., G.H.N., G.E.S.d.L. and L.G.P.; writing—original draft preparation, H.R.O., G.H.N. and G.E.S.d.L.; writing—review and editing, H.R.O., G.H.N., G.E.S.d.L., L.G.P., J.C.L.R., and J.M.F.d.C.; visualization, H.R.O., G.H.N. and G.E.S.d.L.; supervision, L.G.P., J.C.L.R., J.M.F.d.C., F.A.F., R.A.F.P. and D.S.d.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the support provided by the Department of Civil Engineering of the Federal University of Viçosa.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Feng, Y.; Su, Y.; Lu, N.; Shah, S. Meta Concrete: Exploring Novel Functionality of Concrete Using Nanotechnology. Eng. Sci. 2020, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, D.D.L. Self-Sensing Concrete: From Resistance-Based Sensing to Capacitance-Based Sensing. Int. J. Smart Nano Mater. 2021, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubertini, F.; D’Alessandro, A. Concrete with Self-Sensing Properties. In Eco-Efficient Repair and Rehabilitation of Concrete Infrastructures; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 501–530. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, D.D.L. A Critical Review of Piezoresistivity and Its Application in Electrical-Resistance-Based Strain Sensing. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55, 15367–15396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinesh, A.; Indhumathi, S.; Pichumani, M. Self-Sensing Cement Composites for Structural Health Monitoring: From Know-How to Do-How. Autom. Constr. 2024, 160, 105304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.; Aslani, F.; Han, B. Prediction of Mechanical and Electrical Properties of Carbon Fibre-Reinforced Self-Sensing Cementitious Composites. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Lu, D.; Yin, B.; Leng, Z. Advancing Carbon Nanomaterials-Engineered Self-Sensing Cement Composites for Structural Health Monitoring: A State-of-the-Art Review. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 87, 109129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elseady, A.A.E.; Zhuge, Y.; Ma, X.; Chow, C.W.K.; Lee, I.; Zeng, J.; Gorjian, N. Development of Self-Sensing Cementitious Composites by Incorporating a Two-Dimensional Carbon-Fibre Textile Network for Structural Health Monitoring. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 415, 135049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekzhanova, Z.; Memon, S.A.; Kim, J.R. Self-Sensing Cementitious Composites: Review and Perspective. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Li, W.; Guo, Y.; He, X.; Sheng, D. Effects of Silica Fume on Physicochemical Properties and Piezoresistivity of Intelligent Carbon Black-Cementitious Composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 259, 120399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Li, Y.; Zheng, J.; Wang, S. A State-of-the-Art on Self-Sensing Concrete: Materials, Fabrication and Properties. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 177, 107437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, G.; Nalon, G.; Santos, R.F.; Ribeiro, J.C.L.; Franco de Carvalho, J.M.; Pedroti, L.G.; de Araújo, E.N.D. Microstructural Investigation of the Effects of Carbon Black Nanoparticles on Hydration Mechanisms, Mechanical and Piezoresistive Properties of Cement Mortars. Mater. Res. 2020, 24, e20200539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalon, G.H.; Ribeiro, J.C.L.; Pedroti, L.G.; da Silva, R.M.; de Araújo, E.N.D. Behavior of Self-Sensing Masonry Structures Exposed to High Temperatures and Rehydration. Structures 2024, 68, 107083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Yu, X.; Ou, J. Self-Sensing Concrete in Smart Structures; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; ISBN 9780128005170. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, T.U.; Kim, M.K.; Park, J.W.; Kim, D.J. Effects of Temperature and Humidity on Self-Stress Sensing Capacity of Smart Concrete Blocks. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 69, 106227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xiao, H.; Ou, J. Electrical Property of Cement-Based Composites Filled with Carbon Black under Long-Term Wet and Loading Condition. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2008, 68, 2114–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Li, H.; Ou, J. Strain Sensing Properties of Cement-Based Sensors Embedded at Various Stress Zones in a Bending Concrete Beam. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2011, 167, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Ding, S.; Yu, X. Intrinsic Self-Sensing Concrete and Structures: A Review. Measurement 2015, 59, 110–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horňáková, M.; Lehner, P. Relationship of Surface and Bulk Resistivity in the Case of Mechanically Damaged Fibre Reinforced Red Ceramic Waste Aggregate Concrete. Materials 2020, 13, 5501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogra, A.; Hazim, S.; Goyal, A.; Bhatia, A.; Sharma, S. Developing Embeddable Self-Sensing Cementitious Composite Sensor Incorporating Carbon Based Materials for Smart Structural Health Monitoring. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 111, 113278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Pan, J.; Xu, L.; Cai, J.; Li, X.; Meng, L.; Li, N. Development of Self-Sensing Engineered Cementitious Composite Sensors for Monitoring Flexural Performance of Reinforced Concrete Beam. Dev. Built Environ. 2024, 18, 100407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Ahmed, A.H.; Liebscher, M.; Li, H.; Guo, Y.; Pang, B.; Adresi, M.; Li, W.; Mechtcherine, V. Electrical Resistivity and Self-Sensing Properties of Low-Cement Limestone Calcined Clay Cement (LC3) Mortar. Mater. Des. 2025, 252, 113790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Qu, F.; Dong, W.; Wang, Y.; Yoo, D.-Y.; Maruyama, I.; Li, W. Self-Sensing Performance of Nanoengineered One-Part Alkali-Activated Materials-Based Sensors after Exposure to Elevated Temperature. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 164, 106257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, N.; Yang, Y.; Lv, T.; Lu, J. Development of Self-Sensing Cement Composites by Incorporating Hybrid Biochar and Nano Carbon Black. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 153, 105708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.I.; Khan, R.I.; Ashraf, W.; Pendse, H. Production of Sustainable, Low-Permeable and Self-Sensing Cementitious Composites Using Biochar. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2021, 28, e00279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xiang, J.; Qiang, S.; Lu, H. Study on the Optimization of Electromechanical Properties and Fiber Dispersion Mechanisms in Red Mud-Carbon Fiber-Cement Ternary Composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 490, 142527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Guo, Y.; Sun, Z.; Tao, Z.; Li, W. Development of Piezoresistive Cement-Based Sensor Using Recycled Waste Glass Cullets Coated with Carbon Nanotubes. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 127968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Liu, M.; Rao, M.; Jiang, T.; Zhuang, J.; Zhang, Y. Stepwise Extraction of Valuable Components from Red Mud Based on Reductive Roasting with Sodium Salts. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 280, 774–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Han, Y.; He, F.; Gao, P.; Yuan, S. Characteristic, Hazard and Iron Recovery Technology of Red Mud—A Critical Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 420, 126542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Wu, H.; Lv, Z.; Yu, H.; Tu, G. Recovery of Valuable Metals from Red Mud: A Comprehensive Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 166686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Pan, J.; Zhu, D.; Guo, Z.; Shi, Y.; Dong, T.; Lu, S.; Tian, H. A New Route for Separation and Recovery of Fe, Al and Ti from Red Mud. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Qiang, S. Exploring the Potential of Bayer Red Mud: Toward Self-Sensing Cementitious Composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 460, 139850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu Babu, U.; Kondraivendhan, B. Influence of Bauxite Residue (Red Mud) on Corrosion of Rebar in Concrete. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2020, 5, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D.V.; Labrincha, J.A.; Morelli, M.R. Chloride Diffusivity in Red Mud-Ordinary Portland Cement Concrete Determined by Migration Tests. Mater. Res. 2011, 14, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D.V.; Labrincha, J.A.; Morelli, M.R. Effect of the Addition of Red Mud on the Corrosion Parameters of Reinforced Concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2012, 42, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konkanov, M.; Salem, T.; Jiao, P.; Niyazbekova, R.; Lajnef, N. Environment-Friendly, Self-Sensing Concrete Blended with Byproduct Wastes. Sensors 2020, 20, 1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, W.T.; Yu, W.; Dong, X.; Hao, W. Study on Stress-Strain-Resistivity and Microscopic Mechanism of Red Mud Waste Modified by Desulphurization Gypsum-Fly Ash under Drying-Wetting Cycles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 249, 118772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalon, G.H.; Santos, R.F.; Lima, G.E.S.d.; Andrade, I.K.R.; Pedroti, L.G.; Ribeiro, J.C.L.; Franco de Carvalho, J.M. Recycling Waste Materials to Produce Self-Sensing Concretes for Smart and Sustainable Structures: A Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 325, 126658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C150; Standard Specification for Portland Cement. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- Oliveira, H.R.; Nalon, G.H.; de Lima, G.E.S.; Pedroti, L.G.; Ribeiro, J.C.L.; de Carvalho, J.M.F.; Ferreira, F.A. Effects of Red Mud on the Mechanical and Piezoresistive Properties of Mortars. In Proceedings of the Characterization of Minerals, Metals, and Materials (TMS 2025), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 23–27 March 2025; pp. 345–356. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, S.; Lataye, D.H.; Chaddha, M.J.; Mishra, R.S.; Mahendiran, P.; Mukhopadhyay, J.; Yoo, C.; Wasewar, K.L. An Alternative to Clay in Building Materials: Red Mud Sintering Using Fly Ash via Taguchi’s Methodology. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2013, 2013, 757923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Wang, G.; Yang, Z.; Huang, S.; Guo, W.; Shen, Y. Preparation, Characterization, and Photocatalytic Properties of Modified Red Mud. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 2015, 907539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridaoui, H.; Jada, A.; Vidal, L.; Donnet, J.-B. Effect of Cationic Surfactant and Block Copolymer on Carbon Black Particle Surface Charge and Size. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2006, 278, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares de Lima, G.E.; Nalon, G.H.; Santos, R.F.; Pedroti, L.G.; Lopes Ribeiro, J.C.; Franco de Carvalho, J.M.; Duarte de Araújo, E.N.; Garcez de Azevedo, A.R. Evaluation of the Effects of Sonication Energy on the Dispersion of Carbon Black Nanoparticles (CBN) and Properties of Self-Sensing Cementitious Composites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shi, F.; Shen, J.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, L.; Huang, H.; Liu, J.; Jin, K.; Feng, L.; Tang, Z. Research on the Self-Sensing and Mechanical Properties of Aligned Stainless Steel Fiber-Reinforced Reactive Powder Concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 119, 104001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Cai, J.; Pan, J.; Sun, Y. Study on the Conductivity of Carbon Fiber Self-Sensing High Ductility Cementitious Composite. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 43, 103125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Han, L.; Wu, P.; Dai, K.; Liu, Z.; Wu, C. Design of 3D Printing Green Ultra-High Performance Concrete Based on Binder System Optimization. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco de Carvalho, J.M.; Schmidt, W.; Kühne, H.-C.; Peixoto, R.A.F. Influence of High-Charge and Low-Charge PCE-Based Superplasticizers on Portland Cement Pastes Containing Particle-Size Designed Recycled Mineral Admixtures. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, W. Design Concepts for the Robustness Improvement of Self Compacting Concrete: Effects of Admixtures and Mixture Components on the Rheology and Early Hydration at Varying Temperatures. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universiteit Eindhoven, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vasiliou, E.; Schmidt, W.; Stefanidou, M.; Kühne, H.-C.; Rogge, A. Effectiveness of Starch Ethers as Rheology Modifying Admixture for Cement Based Systems. Acad. J. Civ. Eng. 2017, 35, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, A.; D’Alessandro, A.; Ubertini, F.; Laflamme, S.; Geiger, R. Biphasic DC Measurement Approach for Enhanced Measurement Stability and Multi-Channel Sampling of Self-Sensing Multi-Functional Structural Materials Doped with Carbon-Based Additives. Smart Mater. Struct. 2017, 26, 065008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, A.; Garcia-Macias, E.; D’Alessandro, A.; Laflamme, S.; Castro-Triguero, R.; Ubertini, F. Continuous and Embedded Solutions for SHM of Concrete Structures Using Changing Electrical Potential in Self-Sensing Cement-Based Composites. Proc. SPIE 2017, 10169, 101691G. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senff, L.; Hotza, D.; Labrincha, J.A. Effect of Red Mud Addition on the Rheological Behaviour and on Hardened State Characteristics of Cement Mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D.V.; Morelli, M.R. Use of Red Mud as Addition for Portland Cement Mortars; Associacao Brasileira de Ceramica (ABC): Sao Paulo, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Xu, J.; Yin, T.; Wang, Y.; Chu, H. Improving Electrical and Piezoresistive Properties of Cement-Based Composites by Combined Addition of Nano Carbon Black and Nickel Nanofiber. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 51, 104312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.-Y.; You, I.; Lee, S.-J. Electrical Properties of Cement-Based Composites with Carbon Nanotubes, Graphene, and Graphite Nanofibers. Sensors 2017, 17, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D.V.; Labrincha, J.A.; Morelli, M.R. Effect of Red Mud Addition on the Corrosion Parameters of Reinforced Concrete Evaluated by Electrochemical Methods. Rev. IBRACON Estrut. E Mater. 2012, 5, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dong, W.; Li, W.; Tao, Z.; Wang, K. Piezoresistive Properties of Cement-Based Sensors: Review and Perspective. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 203, 146–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).