Abstract

The construction industry remains among the most hazardous sectors globally, facing persistent safety challenges despite advancements in occupational health and safety OHS) measures. The objective of this study is to systematically analyze the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in construction safety management and to identify the most effective techniques, data modalities, and validation practices. The method involved a systematic review of 122 peer-reviewed studies published between 2016 and 2025 and retrieved from major academic databases. The selected studies were classified by AI technologies including Machine Learning (ML), Deep Learning (DL), Computer Vision (CV), Natural Language Processing (NLP), and the Internet of Things (IoT), and by their applications in real-time hazard detection, predictive analytics, and automated compliance monitoring. The results show that DL and CV models, particularly Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and You Only Look Once (YOLO)-based frameworks, are the most frequently implemented for personal protective equipment recognition and proximity monitoring, while ML approaches such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) and ensemble algorithms perform effectively on structured and sensor-based data. Major challenges identified include data quality, generalizability, interpretability, privacy, and integration with existing workflows. The paper concludes that explainable, scalable, and user-centric AI integrated with Building Information Modeling (BIM), Augmented Reality (AR) or Virtual Reality (VR), and wearable technologies is essential to enhance safety performance and achieve sustainable digital transformation in construction environments.

1. Introduction

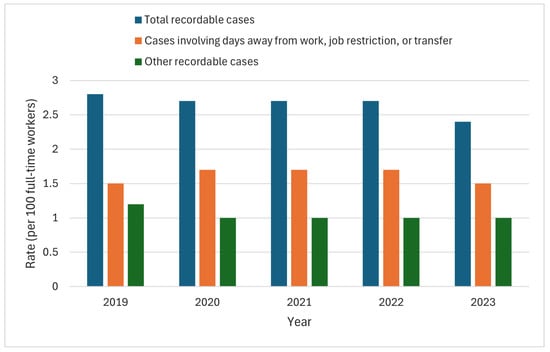

Construction remains one of the most hazardous industries worldwide due to dynamic work environments, complex logistics, and high-risk tasks. The sector accounts for a disproportionate share of work-related injuries and fatalities relative to other industries. In the United States, falls alone constitute nearly 39.9% of construction fatalities, with more than 21,000 deaths reported from 1992 to [1]. China has led industrial fatality statistics since 2012, with 634 construction accidents recorded in 2016 [2]. Across Europe, construction was responsible for 782 fatal incidents in 2014, most commonly associated with falls (26%), material collapse (20%), and equipment failure (19%) [3]. Despite regulatory advances and safety initiatives, traditional Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) measures often struggle to address the multifaceted risks arising from transient, multi-employer sites, fragmented supply chains, and heavy equipment operating under variable environmental conditions [4]. Demographic trends also pose challenges: aging workforces in developed economies experience higher rates of chronic conditions, increasing injury risk and limiting work capacity [5]. The rate of work-related cases with a lost workday or restricted workdays or work transfers fell from 2.8 in 2019 to 2.5 per 100 full-time workers within 2023, as per the Bureau of Labor Statistics. While recordable cases decreased, incidents involving days away from work, job restrictions, or transfer stayed relatively constant, which indicates that severity and effect of injury remains a major concern [6]. Figure 1 demonstrates the trend for total nonfatal work injury and illness cases within the U.S. private industry during the years 2019 through 2023, with a steady trend of decreasing cases of total recordable cases while simultaneously experiencing relatively stable rates for cases of job restriction cases and other recordable cases.

Figure 1.

Nonfatal work injury and illness rates, private industry, 2019–2023 [6].

To overcome these recurring threats, the industry is increasingly adopting integrated safety management systems that take advantage of new technologies. Among them, AI has the potential to transform construction safety approaches from a reactive to a proactive practice. AI is a family of technologies such as Machine Learning (ML), Deep Learning (DL), Computer Vision (CV), Natural Language Processing (NLP), and Internet of Things (IoT) that allow data-driven identification of hazards, predictive risk simulation, and real-time monitoring [7,8]. New research illustrates the increased use of AI to facilitate safety compliance and risk management at operations. For example, it includes creating ML algorithms that produce indicators of safety from project data, allowing early intervention [9]. CV-based systems utilize cameras and drones to recognize dangerous actions, equipment near misses, and Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) violations [10]. NLP methods are applied at scale to unformatted textual content from safety reports and incident records, providing better situation awareness for safety managers [11]. Concurrently, IoT-based wearables and networks of sensors constantly monitor worker wellness factors and environmental factors [12]. A recent systematic literature review by Gao and Sultan (2023) analyzed and classified research on AI applied to improve safety in construction practice. The review identified five main sub-fields of application, including worker risks, construction accidents, personal protective equipment monitoring, machinery safety, and site safety. It found that while supervised learning models such as Logistic Regression, Random Forest (RF), and SVM are widely used for accident prediction and risk assessment, DL models such as CNN and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) perform effectively in visual recognition tasks. However, most studies remain limited by small datasets and fragmented focus areas, highlighting the need for a unified, data-driven framework that integrates all safety dimensions and enhances the generalizability of AI-based safety systems across the construction lifecycle [13].

Despite advancing technology, widespread implementation remains constrained by technical and organizational barriers, including data quality and availability, interoperability between systems, model interpretability and trust, privacy and ethical considerations, and misalignment with established site workflows. Addressing these issues demands a multi-faceted solution with a blend of technical innovation, organizational evolution, and regulation adjustment. This study provides a systematic review of AI applications in construction safety. It synthesizes 122 peer-reviewed sources across ML, DL, CV, NLP, and IoT to (1) catalog tools and techniques used to enhance safety; (2) assess which models are most effective across data modalities and tasks; (3) identify key challenges to integration and scale; and (4) outline future research directions and opportunities. By critically examining recent work, this research contributes toward a broader insight into how AI may ensure safer construction sites through several research questions, explained in later sections.

This review is timely given the rapid evolution of AI technologies, including Generative AI (Gen-AI), foundation models, and Multimodal (MM) learning. While most existing studies in construction safety still rely on conventional supervised learning techniques and single-modality inputs, such as images or sensor data, emerging approaches are beginning to leverage large language models (LLMs) and cross-modal reasoning. By incorporating these developments into this paper’s discussion, this review goes beyond summarizing past trends and aims to position the field within a broader technological shift. Compared to prior reviews that focus narrowly on one AI domain, this study provides an integrated view across ML, CV, NLP, and IoT, and an “AI Framework for Construction Safety”, offering researchers and practitioners a clearer understanding of current capabilities and future directions.

2. Materials and Methods

This section outlines the methodology used in this study across four subsections: (1) data sources, (2) search strategy, (3) selection criteria, and (4) research questions.

2.1. Data Sources

A comprehensive review of AI applications in construction safety is conducted using literature obtained from multiple reputable databases, including IEEE Xplore, Scopus, PubMed, and Google Scholar. A total of 122 research papers are selected to ensure broad coverage of various perspectives and methodologies within the field. The selection process prioritizes high-quality, peer-reviewed studies that contribute to understanding AI-driven safety measures in construction.

To present an overview of the sources analyzed, Table 1 summarizes the number of research articles published in different journals and conferences. The distribution of articles across various sources reflects the importance of AI applications in construction safety within academic research.

Table 1.

Number of papers published in the selected journals.

A considerable portion of the literature is concentrated in journals dedicated to AI and automation, such as Automation in Construction and Advanced Engineering Informatics, which emphasize AI-driven monitoring, risk management, and safety enhancement. Other sources include journals in intelligent systems and sensor technologies, which explore AI-driven hazard detection and environmental monitoring.

Additionally, several studies are published in journals that address structural and environmental safety, emphasizing AI’s potential in predictive analytics and incident prevention. The role of AI in promoting sustainable and resilient infrastructure is also evident, with research appearing in journals such as Sustainability and Buildings. Furthermore, journals related to engineering management and process optimization highlight AI’s application in improving workflow efficiency and safety compliance. Lastly, sources focusing on applied sciences demonstrate the growing interest in practical, interdisciplinary approaches to integrating AI into real-world construction settings. The diversity of publication venues emphasizes the multidisciplinary nature of AI research in construction safety and its relevance across engineering, technology, and management domains.

2.2. Search Strategy

A systematic search strategy is employed using predefined keywords and search terms to maximize the retrieval of relevant studies. The search includes terms such as “AI in construction safety”, “ML and construction hazards”, “AI-powered hazard detection”, “DL applications in construction safety”, “NLP for safety compliance”, and “AI in workplace safety monitoring in construction”. Additionally, keywords like “Automated safety audits using AI in construction”, “Predictive analytics for safety incident forecasting in construction”, “CV for construction site surveillance”, and “AI-driven safety training and simulation in construction” are utilized. These terms are applied in various combinations across selected databases to ensure comprehensive coverage and enable a thorough exploration of AI applications in enhancing construction site safety.

2.3. Selection Criteria

The review employed rigorously defined inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure the relevance and methodological quality of the selected studies.

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

To ensure the review covers current and relevant AI improvement in construction safety, studies published within the last ten years are considered. The search period is fixed between 2016 and 2025, allowing for the inclusion of the most recent developments and trends in the field. This time-frame ensures that the research considers the latest technological progress while maintaining a comprehensive perspective on AI applications in construction safety.

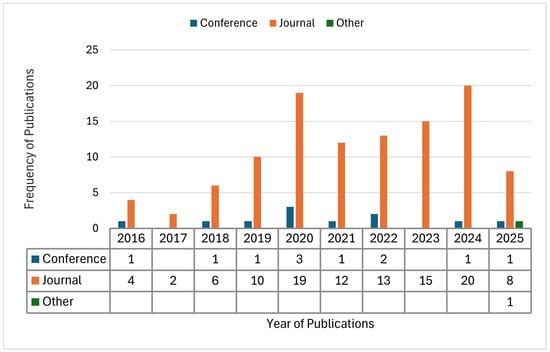

The selection process classifies the sources into two main categories of: (a) academic publications, which include peer-reviewed journal and conference papers, and (b) other publications, such as reports and theses. Figure 2 presents a distribution of the selected articles based on their type and publication year. Following two rounds of screening, a total of 122 articles are included in the analysis. The figure also indicates a significant rise (from 5 publications in 2016 to 23 in 2024) in research on AI applications in construction safety in recent years, evaluating the increasing focus and improvement in this area.

Figure 2.

Frequency of reviewed references and their publication years.

The relevance to construction safety is determined through a detailed review of abstracts, ensuring the inclusion of studies specifically focused on the safety and health of construction workers. This study includes studies that specifically examine the use of AI to enhance construction safety, with a focus on applications such as hazard detection, risk assessment, accident prediction, and compliance monitoring. This approach ensures that the selected studies directly contribute to AI-driven improvement in construction safety.

Additionally, the review only considers studies published in English to maintain accessibility and consistency in the review process. This language criterion enables effective analysis and comparison of findings, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of AI applications in construction safety.

2.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

Several exclusion criteria are applied to ensure the quality and relevance of the studies included in this review. Studies published before 2016 were excluded unless identified as seminal works, as earlier research often relied on outdated technologies or methodologies. Publications that mention AI and construction but do not specifically address safety applications, such as those focused on project management or cost estimation, are also excluded. Non-empirical studies, including editorials, literature reviews, opinion pieces, and non-peer-reviewed studies are excluded due to the lack of empirical data or detailed methodologies. Studies with incomplete data unclear methodology and results sections are removed, as they cannot provide a reliable basis for comparative analysis. Additionally, non-English publications are excluded unless they contain essential findings not available in English, in which case professional translation is considered.

2.4. Research Questions (RQs)

The aim of this systematic review is to establish a set of RQs that serve as the foundation for this study. These questions guide the process of collecting relevant scholarly work and analyzing it. The RQs are designed to structure the research in a coherent manner, ensuring that the review addresses key aspects of AI applications in construction safety. The following RQs are formulated to structure and direct the research process.

- What AI-driven tools and techniques are utilized to enhance construction safety?

- Which AI models are most effective in improving safety performance on construction sites?

- What are the key challenges of integrating AI technologies into construction safety?

- What are the future directions and opportunities for AI in construction safety?

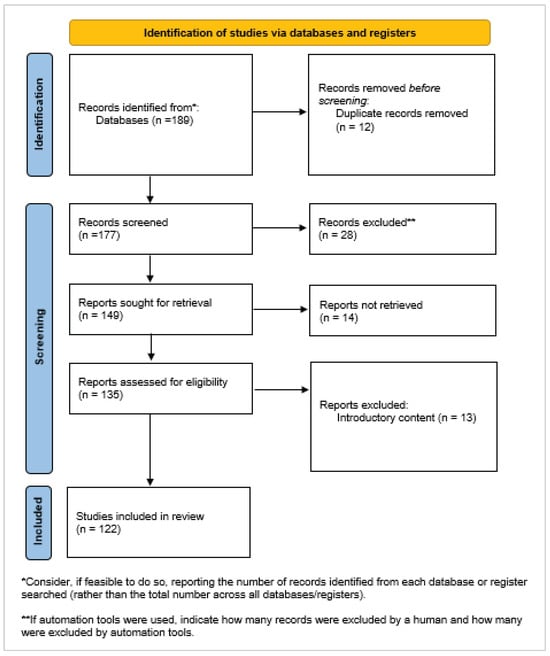

A systematic literature search and screening process is conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines (see Supplementary Materials). Relevant records are initially identified through comprehensive searches of electronic databases, followed by the removal of duplicate entries to ensure the uniqueness of the dataset. The remaining studies proceed through a screening phase based on titles and abstracts, during which records that are not aligned with the research objectives are excluded. Full texts are then sought for the studies that pass the initial screening, although some documents are not retrievable. The accessible reports are then examined to determine their eligibility, and those that do not meet the inclusion criteria, such as those containing only introductory content, are excluded. The final set of studies included in the review consists of those that fully satisfy the predefined eligibility criteria. Figure 3 presents an overview of PRISMA study selection process from identification to final inclusion based on eligibility criteria.

Figure 3.

PRISMA flow diagram of the literature selection process.

3. Results

Each RQ is answered in the following subsections, starting with RQ1 on AI-driven tools and techniques for construction safety.

3.1. RQ1: What AI-Driven Tools and Techniques Are Utilized to Enhance Construction Safety?

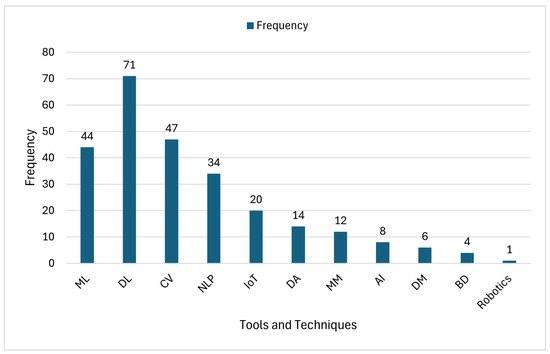

The first RQ explores different AI techniques including ML, DL, CV, NLP, IoT, Multimodal (MM), Big Data (BD), Data Mining (DM), and Robotics. To systematically evaluate AI applications in construction safety, the selected studies are categorized based on the AI techniques applied. Each category is examined to determine its role in enhancing safety measures within the construction sector. A summary of the frequency of AI techniques utilized in construction safety research is presented in Table 2. This table outlines the most applied AI technologies, emphasizing their significance in accident prevention, real-time monitoring, and compliance enforcement.

Table 2.

AI Tools and Techniques Used in Construction Safety.

As illustrated in Figure 4, ML and DL are the most frequently applied AI techniques in construction safety research, while CV, NLP, IoT, and robotics are expanding as important areas of innovation.

Figure 4.

Frequency of AI Tools and Techniques in Construction Research.

Table 3 presents the most frequently used ML models, emphasizing their roles in hazard prediction, safety compliance automation, and worker health monitoring.

Table 3.

ML models Used in Construction Safety.

ML serves a foundational role in construction safety by analyzing historical data to predict incidents and enable proactive risk management. ML techniques are widely applied to detect hazards, predict equipment failures, and monitor worker health in real-time. This enables predictive maintenance and automates safety compliance processes. Common ML models include SVM, KNN, DT, RF, and NB, which are particularly effective for classification and prediction tasks. More advanced techniques such as Logistic Regression, Bayesian Networks, XGBoost, Bagging Tree, and Stochastic Gradient Tree Boosting are employed to improve predictive accuracy and manage complex datasets. Moreover, unsupervised and semi-supervised learning methods are used to address the challenges of limited labeled data, while RL is explored for building adaptive and dynamic safety management systems.

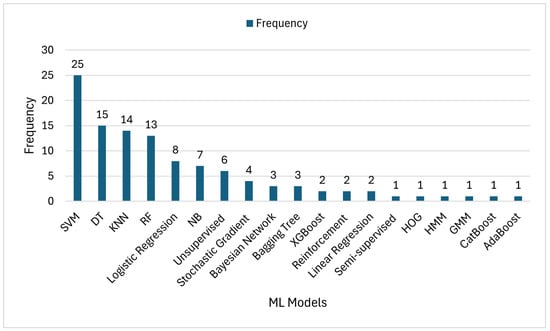

Figure 5 shows that SVM, DT, KNN, and RF are the most used ML models, reflecting their effectiveness in classification and prediction tasks. Advanced models such as XGBoost and unsupervised learning approaches are less dominant but are gaining interest.

Figure 5.

Frequency of ML Models in Construction Research.

Table 4 demonstrates the DL models most commonly applied in safety-related tasks, emphasizing their ability to detect unsafe conditions and support automated safety monitoring.

Table 4.

DL models Used in Construction Safety.

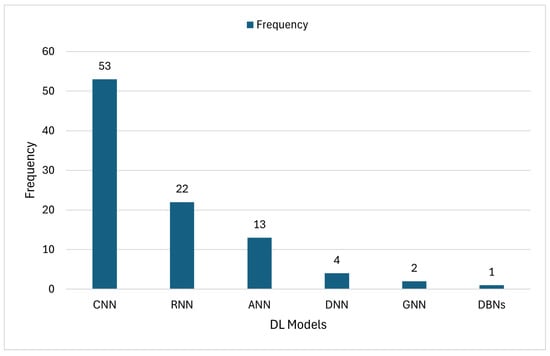

DL techniques have advanced construction safety by enabling real-time detection of hazards and unsafe conditions through complex data analysis. DL models such as CNN are commonly used for processing visual data captured by site cameras and drones. These models recognize unsafe conditions, PPE violations, and structural anomalies. Additionally, RNN and ANN are utilized for analyzing sequential and time-series data related to worker activity and environmental changes. DNN enhance the modeling of non-linear patterns, while GNN and DBNs offer innovative approaches for understanding spatial and relational safety data. Collectively, these DL methods support the automation of safety monitoring systems and the implementation of early warning mechanisms.

Figure 6 highlights the dominance of CNNs among DL models, with RNNs and ANNs also frequently employed for hazard detection and site monitoring.

Figure 6.

Frequency of DL Models in Construction Research.

Table 5 indicates the CV models employed for visual safety assessment, emphasizing their effectiveness in real-time site surveillance, PPE detection, and behavioral analysis.

Table 5.

CV models Used in Construction Safety.

CV technologies are extensively used for visual safety inspection and monitoring on construction sites. CV-enabled systems use camera footage and drone imaging to detect PPE violations, unsafe worker behaviors, and structural risks. These systems automate the safety inspection process, reduce reliance on manual observation, and enable continuous surveillance. By analyzing visual input in real-time, CV enhances situational awareness and supports timely intervention to prevent accidents.

Table 6 explains the NLP models applied to unstructured text data, emphasizing their role in hazard identification, safety communication, and voice-based alert systems.

Table 6.

NLP models Used in Construction Safety.

NLP contributes to construction safety by extracting meaningful information from unstructured text sources such as safety reports, inspection logs, and regulatory documents. NLP models help identify patterns and indicators of potential hazards. Additionally, NLP supports the development of voice-enabled assistants that provide real-time safety alerts and guidance to on-site workers, thereby improving awareness and adherence to safety protocols. LLMs such as Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT) 3.5 process free text accident narratives with strong contextual understanding, enabling clustering and summarization, cause extraction, and direct classification with minimal feature engineering [50,109,113]. In contrast, conventional NLP relies on Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (TF IDF), topic models, and embeddings combined with SVM, RF, or logistic regression, which depend on hand crafted features and often miss long range semantics [50]. Fine-tuned GPT classifiers provide saliency explanations, and highway safety pipelines that combine embedding-based clustering with LLM summarization reveal patterns that traditional methods overlook [26].

IoT technologies facilitate the integration of wearable devices and environmental sensors for continuous safety monitoring. IoT wearables track worker health indicators such as heart rate, fatigue, and location, while embedded sensors detect hazardous site conditions like gas leaks, temperature anomalies, or equipment malfunctions. This network of connected devices enables real-time data transmission and immediate risk detection, contributing to safer and more responsive work environments.

Data Analytics plays a crucial role in processing large datasets generated by IoT devices, sensors, and site operations. It enables the identification of safety risks, trend analysis, and the evaluation of safety measures. By analyzing real-time data, data analytics helps refine construction protocols, optimize resource allocation, and support informed decision-making to enhance safety performance.

A Multimodal (MM) model in a construction site is an intelligent system that integrates information from multiple sources such as images, videos, text, and sensor data to interpret and understand the dynamic conditions of the site. It combines visual perception with language understanding to analyze workers, machinery, materials, and safety conditions in real time. By linking visual cues with contextual descriptions, the model can identify tasks, detect potential hazards, and assess compliance with safety regulations. This integration enables comprehensive situational awareness, allowing automated monitoring of operations, recognition of unsafe behaviors, and generation of descriptive safety or progress reports. Through its ability to reason across different modalities, the MM serves as a foundation for adaptive, data-driven management of construction sites, enhancing safety, efficiency, and decision-making [117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128].

AI serves as an umbrella framework that integrates various intelligent systems, including vision, learning, and sensing technologies. AI improves safety by detecting hazards, predicting risks, and facilitating compliance using data collected from cameras, wearables, and sensors. AI-driven drones and robots also minimize human exposure by performing safety-critical operations in hazardous environments.

Furthermore, DM is employed to uncover hidden patterns in historical safety records, sensor outputs, and worker behavior logs. It supports the identification of risk factors that may lead to incidents and helps organizations design more effective safety interventions. DM improves safety by enabling data-driven decision-making and enhancing the predictive capabilities of AI systems. DM comprises analytic techniques such as association rule mining, clustering, text or topic mining, sequential pattern mining, and feature engineering that convert unstructured or heterogeneous safety data (including incident narratives, sensor logs, and video annotations) into model ready signals; AI methods then learn task-specific models (including PPE detection, proximity alerts, and risk prediction) from these signals.

In addition, BD techniques are used to manage and analyze vast quantities of safety-related information gathered from IoT networks, surveillance systems, and digital platforms. These techniques facilitate real-time risk analysis and provide construction managers with insights to prevent accidents and ensure compliance. BD contributes to the development of scalable, cloud-based safety monitoring systems that can process information from multiple sources simultaneously. In this review, BD platforms built on Hadoop and Spark are used for offline and online processing of historical and live streams to support rapid safety prediction, and AI models are trained within the same pipeline to improve accuracy and reduce latency. Accordingly, BD is reported under data infrastructure and modality (ingestion, storage, processing), and AI under techniques (model development and validation).

Lastly, Robotics is increasingly being adopted in construction safety for automating hazardous tasks such as inspection, material handling, and demolition. Robots equipped with cameras and sensors perform real-time environmental assessments, detect potential hazards, and execute safety-critical operations with high precision. This minimizes the need for human intervention in dangerous scenarios, thereby reducing injury risks and improving operational efficiency. Robots equipped with cameras and sensors conduct real-time environmental assessments, detect potential hazards, and execute safety critical operations with high precision, reducing the need for human presence in dangerous areas and improving operational efficiency. Robotics and aerial drones further enhance safety by removing personnel from hard-to-reach locations, accelerating inspection and progress monitoring, and supplying continuous visual and sensor data for AI-based analysis of behaviors and conditions such as PPE use, worker posture, and proximity to energized lines or unprotected edges. These systems can reduce manual inspection errors and provide broader, faster site coverage for timely safety decisions. At the same time, wider deployment introduces new risks and constraints, including technical instability in dynamic site environments, limited labelled datasets, and privacy concerns from pervasive imaging. Effective controls include operator training and certification, clear operating procedures and change management, and secure data pipelines with access controls and audit trails.

3.2. RQ2: Which AI Models Are Most Effective in Improving Safety Performance on Construction Sites?

A wide range of AI and ML models can be explored to enhance safety performance on construction sites, utilizing various data sources such as textual reports, imagery, sensor readings, physiological signals, and audio data. Table 7 summarizes the datasets used, performance metrics, and the most effective AI architectures as reported across recent scholarly contributions, reviewed in this study.

Table 7.

Selected AI datasets and architecture used in construction site safety research with the best performance.

One prominent trend is the application of CNNs beyond conventional image recognition tasks. For example, time series sensor data, including accelerometer, gyroscope, and barometer readings collected from construction workers, was processed using CNNs to classify physical activity with high precision, achieving an accuracy of 94.9% and an F1 score of 94.75% [77]. This demonstrates the suitability of CNNs for behavior classification using wearable data.

While image-based datasets dominate AI research in construction safety, several studies have successfully applied ML techniques to structured datasets such as the KALIS and OSHA SIR databases. These datasets support regression tasks like injury severity prediction, where models such as DNNs and logistic regression have demonstrated strong performance. For instance, DNNs applied to the KALIS dataset achieved a low mean absolute error (MAE = 0.043) and a high correlation coefficient of 0.9936, indicating their suitability for risk modeling in tabular safety data [97]. Similarly, logistic regression models applied to the OSHA SIR database attained an accuracy of 93.7%, further highlighting the effectiveness of traditional ML approaches in structured-data contexts.

CV applications continue to dominate in visual compliance monitoring. YOLO-based object detection models, particularly YOLOv5, trained on a hybrid dataset comprising Pictor v3, publicly available datasets, and localized construction imagery, achieved mAP@50 values of 83.1% for PPE detection and 92% for heavy equipment detection [63]. These findings highlight YOLO’s robustness in dynamic and complex environments. Similarly, Roboflow and MakeML datasets, among others, were used to train models such as Faster R-CNN, YOLOv5x, and YOLOv3; these models consistently achieved accuracy, precision, and recall above 90%, confirming their effectiveness in real-time site surveillance and PPE compliance [57,60,66,70].

NLP models have also gained traction. OpenAI’s GPT 3.5, for instance, was applied to textual data from OSHA’s Severe Injury Reports, attaining an accuracy of 93.7% and an F1 score of 96.7% [50]. This reflects the growing use of LLMs in extracting actionable insights from narrative safety records and injury logs, tasks that previously required manual review.

Beyond vision and text, other modalities have shown promise. AutoML frameworks were employed to classify accident types in imbalanced datasets, such as Chinese construction accident records, with performance improving from 83.6% to 84.4% after applying synthetic minority oversampling techniques (SMOTE) [15]. SVMs were applied to physiological signals gathered from Empatica E4 wristbands; these effectively identified stress and fatigue patterns with an accuracy of 81.2% [16]. In the oil and gas sector, SVMs outperformed ensemble models for injury type and severity prediction, while a stacked XGBoost and RF combination performed better for incident type and body part classification.

Emerging audio-based safety monitoring also illustrates the adaptability of CNNs. When applied to classify hazardous events from construction activity audio clips extracted from YouTube, CNNs achieved up to 98.52% accuracy, even in challenging acoustic backgrounds [62]. Meanwhile, SSD MobileNet, a lightweight yet effective CV model, was trained on site-captured and web-crawled videos; it reached 95% precision and 77% recall, highlighting its potential for mobile and drone-based applications despite its lower mAP [68].

Additional studies leveraged simulated or synthetic data for hazard prediction. For instance, finite element model (FEM) simulations provided strain data used to train an SVM, which achieved a 96% classification accuracy, supporting its use in structural risk analysis [19]. YOLOv3 with a Darknet-53 backbone performed well on a mixed COCO and custom dataset, further affirming YOLO’s versatility [72]. Traditional ML models such as RF and stochastic gradient tree boosting were also effectively applied to legacy datasets from industries including mining and infrastructure [9,44]. CV-based models are best suited for unstructured visual data tasks such as detecting PPE violations and unsafe behaviors, while tabular ML models such as SVM and RF are more effective in processing structured datasets like safety inspection logs or physiological data to predict injury type and risk severity.

Overall, the findings in Table 7 indicate that CNN-based models dominate in image, audio, and sensor-driven applications, capitalizing on their superior spatial and temporal recognition capabilities. CNNs consistently outperform traditional ML models in image-based safety applications due to their superior spatial feature extraction capabilities. For instance, while traditional models such as SVM or RF typically achieve accuracy levels in the 70–80% range on tabular or sensor-based datasets [9,14], CNN-based models like YOLOv5 and Faster R-CNN have demonstrated mAP@50 values exceeding 90% on complex construction images [63,70]. In contrast, structured numerical data is best managed using traditional ML models such as SVM, RF, and ensemble methods like gradient boosting. The successful application of GPT 3.5 illustrates the emerging value of LLMs in interpreting unstructured text for safety insights. Ultimately, model selection should be guided by the nature of the data and the safety task at hand, underscoring the importance of aligning AI architecture with specific construction site challenges to maximize predictive accuracy and operational utility.

Recent MM safety frameworks further extend this progress by enhancing generalization and interpretability across visual and textual domains. A zero-shot system integrating Florence-2, SAM-2, and GPT-4o achieved an F1 score of 82.2%, task accuracy of 79.0%, and idle-state recognition of 93.2% on the Alberta Construction Image Dataset and YouTube clips [128]. The Clip2Safety framework, combining BLIP2-OPT-2.7B, YOLO-World, CLIP, and GPT-4o, reported an overall accuracy of 77.2% and an AUC of 0.76 across multiple datasets [122]. Similarly, a zero-shot CLIP model applied to OSHA prevention images and hazard descriptions attained 70% accuracy in human-verified labeling [119]. Collectively, these studies indicate a transition toward explainable, cross-modal, and context-aware AI capable of integrating visual and linguistic cues for proactive safety monitoring in dynamic construction environments.

The dominance of models such as CNNs and YOLO reflects the field’s heavy emphasis on visual data sources, including camera and drone imagery. This trend is driven by the relative ease of collecting labeled images compared to structured logs or unstructured text. It also indicates that many research efforts prioritize observable hazards (e.g., PPE violations, proximity detection) over less tangible factors like human intent or systemic risks. Meanwhile, textual data (e.g., reports, near-misses) and audio-based sensing remain underutilized, suggesting methodological gaps. These patterns reveal both a reliance on mature, well-supported CV models and a need to explore underrepresented modalities using NLP, LLMs, or MM architectures.

To support practical adoption, this paper proposes a straight forward decision-making framework that aligns AI model selection with data type and task complexity. For tasks involving visual data such as PPE detection or proximity monitoring, DL models, especially CNNs and object detection frameworks like YOLO, are most appropriate due to their superior spatial recognition. When working with structured tabular data (e.g., injury logs, sensor outputs), traditional ML models such as RF, SVM, or logistic regression are more effective and easier to interpret. For unstructured textual data (e.g., incident reports), NLP techniques like BERT or GPT-based models are suitable. Practitioners with limited computational resources may benefit from using ensemble models like XGBoost, which offer strong performance with relatively lower overhead. Ultimately, the choice of method should balance the nature of the input data, real-time processing needs, interpretability, and available expertise.

Despite promising performance across tasks, the majority of AI applications in construction safety remain in the experimental or pilot phase. Moving toward real-world implementation requires addressing several infrastructural, data-related, and human-factor challenges. On the technical side, site-specific variability and lack of standardized data pipelines hinder model generalization and scalability. Data-related issues include inconsistent labeling practices, privacy constraints, and limited access to large, diverse, and high-quality multimodal datasets. From a human-centered perspective, frontline personnel may lack the training or trust to interact with AI systems effectively. Resistance can stem from concerns about job displacement, opaque decision logic, or additional cognitive burden. Overcoming these challenges will require not only technical refinement, but also organizational readiness, stakeholder engagement, and regulatory guidance tailored to the unique dynamics of construction environments.

3.3. RQ3: What Are the Key Challenges of Integrating AI Technologies into Construction Safety?

Adoption of AI technologies in the construction sector remains limited due to a variety of practical, technical, and organizational challenges. This section identifies and categorizes the key barriers impeding successful AI implementation in construction safety. Table 8 outlines the primary challenges associated with the integration of AI technologies into construction safety, highlighting common issues reported across current literature.

Table 8.

The key challenges of integrating AI technologies into construction safety.

A primary technical limitation concerns the quality and availability of data. Construction environments often produce incomplete, noisy, imbalanced, or unstructured datasets, which diminish the accuracy and generalizability of AI models [9,14,15,22,47,61]. In parallel, real-time monitoring, particularly in applications involving CV, poses computational challenges. These systems require high processing power to analyze live video feeds and are susceptible to performance degradation under adverse environmental conditions such as low light or occlusion [18,40,58,60,65,70,71,72,75].

Integration with existing workflows remains a barrier, since AI tools often misalign with established safety protocols and site practices, limiting adoption. This misalignment can result in low adoption rates or active resistance from field personnel unfamiliar with or skeptical of digital technologies [9,17,57,67,75,98,102]. This is further compounded by the lack of model interpretability, especially with DL techniques, which often function as “black boxes.” Without transparent decision-making processes, safety managers may be reluctant to trust AI-generated insights [14,20,50,66,71,74].

Domain adaptability is also limited; AI models trained in specific regional or environmental contexts (e.g., UAE or Hong Kong) often struggle to perform reliably in different geographic or regulatory settings [57,60]. Performance can decline with shifts in appearance and environment (PPE styles, illumination, humidity or dust that cause blur), differences in sensors and cameras, and jurisdiction specific task definitions. For instance, a UAE protocol trains a YOLO-based model for working at height compliance and validates across RGB, grayscale, high brightness, dust, and blur, revealing condition-sensitive performance and the need for local augmentation and fine tuning. By contrast, a Hong Kong study uses fixed cameras for detection, tracking, and hazard status; because it depends on site layout and camera geometry, thresholds and calibration need region specific adjustment. Ethical concerns, particularly regarding privacy, arise when AI systems involve continuous worker surveillance via wearables or site cameras. These practices introduce concerns about data governance, informed consent, and workplace monitoring ethics [16,58,60,73,101,108].

Another frequently cited limitation is the shortage of skilled personnel. The effective implementation and maintenance of AI solutions in construction require data scientists, software engineers, and technicians roles that are in short supply, particularly in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) [9,50]. Compounding this, the accuracy of AI detection systems remains an issue, with false positives and negatives leading to misplaced trust or neglect of real hazards [60,63,65,69,71].

Furthermore, reliance on hardware systems such as wearables and sensors introduces maintenance, durability, and user compliance challenges [16,57,68,77,98,101]. From a behavioral modeling perspective, current AI tools are limited in their ability to assess human psychological factors, such as stress, fatigue, or risk perception elements critical to proactive safety management [16,40,72,77].

The scalability and generalizability of AI systems also remain unresolved. Models developed for one site often require substantial retraining to perform effectively elsewhere, limiting the economic feasibility of AI deployment across multiple projects [49,64,66,69,73,75,76]. In addition, the burden of manual annotation and dataset preparation poses a resource bottleneck. Labeling data necessary for supervised learning algorithms is time-consuming and expensive in dynamic construction settings [19,20,22,61,64,74].

Finally, there is a widely acknowledged gap in AI-capable workforce availability. Many firms lack the in-house expertise needed to deploy, fine-tune, and manage AI tools, especially those operating in resource-constrained environments [61,64,67,74,75,109]. These workforce limitations hinder both initial AI adoption and long-term sustainability. In addition, prompt sensitivity and contextual bias remain critical barriers in multimodal AI, as model outputs often fluctuate with changes in question phrasing, visual cropping, or environmental context. Moreover, domain-specific knowledge gaps persist because general-purpose VLMs such as CLIP and Florence-2 lack construction-oriented semantics, limiting their ability to reason about complex, context-dependent hazards [119,122,128].

Together, these findings illustrate the multifaceted nature of the challenges facing AI integration in construction safety and highlight the need for interdisciplinary solutions that address technical, social, and organizational dimensions simultaneously.

3.4. RQ4: What Are the Future Directions and Opportunities for AI in Construction Safety?

The construction industry is increasingly adopting AI to transform safety management through enhanced risk prediction, real-time monitoring, and data-driven decision-making. Advanced techniques such CV, DL, and NLP are being applied to address critical challenges, including hazard identification, PPE compliance, and accident prediction. Ongoing research continues to expand the scope of AI applications, contributing to safer and more efficient construction environments. Table 9 outlines the applications of AI in predictive analytics for construction safety, including accident forecasting, injury prediction, fall risk analysis, and safety consequence forecasting. It highlights future directions such as BIM integration, real-time dashboards, AutoML, and explainable AI, along with relevant research publications.

Table 9.

The future directions and opportunities for AI in construction safety (Predictive Analytics and Risk Forecasting).

Table 10 presents the applications of CV in construction safety management, such as PPE compliance detection, site hazard recognition, UAV-based monitoring, and Visual Question Answering (VQA). Future enhancements include 3D detection, integration with BIM and drones, attention mechanisms, and real-time monitoring systems.

Table 10.

The future directions and opportunities for AI in construction safety (CV).

Table 11 summarizes NLP-based approaches for improving construction safety, focusing on hazard classification, incident report analysis, OSHA regulation automation, and knowledge graph creation. Future opportunities include multilingual NLP, mobile deployment, LLM-based tools (e.g., ChatGPT), and integration with BIM and XR platforms.

Table 11.

The future directions and opportunities for AI in construction safety (NLP).

Table 12 details integrated and multimodal AI approaches in construction safety, including AI-augmented training, VR-based eye tracking, audio-based hazard detection, physiological monitoring with wearables, and sensor-based monitoring systems. It also covers hybrid techniques like vision-rule semantic matching and lightweight ML models for mobile PPE detection.

Table 12.

The future directions and opportunities for AI in construction safety (Integrated modalities and approaches).

AI is being applied to forecast accidents using ML models trained on inspection and incident data. Techniques such as NLP, fuzzy logic, and AutoML are being integrated with BIM systems to create real-time dashboards and risk alerts. For instance, AutoML and RF models are used to predict the severity of safety outcomes, while fuzzy logic and unsupervised ML enhance excavation and fall hazard analysis [9,14,15,17,38,44,47,49,61,98,112]. CV has become pivotal in monitoring on-site activities. Applications range from detecting worker-equipment interactions using convolutional and RNN (CNN, LSTM) to real-time monitoring of PPE compliance via YOLO and other object detection algorithms. Future directions involve integrating these models with drone surveillance, 3D mapping, and mobile alert systems [57,60,63,66,68,69,70,71,73,75,83,84,86,92].

NLP is utilized for semantic classification of safety reports, near-miss incident analysis, and automated OSHA regulation compliance. Models such as BERT and TF-IDF are enhancing multilingual classification, root cause detection, and dashboard integration. Knowledge graphs generated from NLP outputs offer risk detection and are being linked to BIM/XR environments [22,23,25,52,61,64,67,74,79,87,98,111,112]. LLMs such as ChatGPT, are being explored for narrative safety data analysis and multilingual reasoning. VQA models combining transformers with AR/XR interfaces are being developed for enhanced inspection and safety training capabilities [16,18,50,62,65,71,101,103,108,113]

Recent MM AI frameworks in construction safety employ zero-shot and interpretable Vision-Language Models (VLMs) for hazard and PPE detection. They enable real-time, explainable, and cross-modal monitoring by integrating visual, textual, and contextual cues for proactive hazard prevention [119,122,128]. AI models analyze audio signals to detect high-risk events such as collisions in noisy construction environments. Wearable sensor data and physiological monitoring systems assess fatigue and stress levels in real-time, providing adaptive safety responses. Integrated systems are merging IoT, ML, and photogrammetry to support BIM-linked hazard prediction [16,18,62,65,72,102]. Hybrid approaches combine rule-based reasoning with vision models to match observed site behaviors with formal safety rules. Lightweight models such as HOG and CHT are optimized for mobile applications, ensuring real-time helmet and PPE compliance monitoring on resource-constrained devices [21,68,75,78,82,88].

AI is increasingly supporting adaptive safety training modules tailored to individual risk levels. Virtual AI environments simulate rare or complex hazard scenarios for DL model training. Eye-tracking integrated with VR facilitates immersive training by analyzing user attention and perception of hazards [58,100,104,109,113]. During the CHPtD phase, LLMs assist in identifying potential risks and safety clashes before construction begins. These tools support early intervention and safer design practices [108].

Table 13 shows this study’s proposed conceptual framework that integrates artificial intelligence domains with construction safety workflows. It illustrates how different AI techniques support each stage of the safety process, from data acquisition and hazard detection to risk prediction, information extraction, MM reasoning, and continuous feedback. The table highlights representative models, datasets, and applications that demonstrate how AI contributes to real-time monitoring, contextual awareness, and adaptive learning within construction safety management.

Table 13.

Conceptual Framework Integrating AI Domains with Construction Safety Workflows.

To enhance trust and adoption among safety personnel, future research should prioritize the development of explainable and human-centered AI systems. This includes incorporating interpretable outputs, visual explanations, and customizable dashboards that align with how decisions are made on-site. In parallel, the creation of user-friendly GUI-based tools that embed ensemble and DL models can empower practitioners without technical backgrounds to interact with AI systems more intuitively. Together, these efforts can bridge the gap between complex model outputs and practical, actionable insights for improving construction safety.

4. Discussion

The findings of this review show substantial progress in the use of AI for improving construction safety management, but they also reveal several inconsistencies and research gaps that distinguish this study from earlier reviews. Previous research, especially before 2020, mainly focused on the potential of AI to automate safety monitoring. The current analysis demonstrates that implementation has shifted toward domain-specific applications that are mainly supported by DL and CV methods. CNN and YOLO models are now the most frequently applied because of their effectiveness in real-time object detection, particularly for recognizing PPE and unsafe worker behaviors. Although these approaches achieve high accuracy in laboratory conditions, their ability to perform reliably in complex, dynamic environments remains limited. Differences among studies confirm this issue, as models trained on specific datasets often perform poorly when applied to new projects, weather conditions, or lighting settings. This pattern indicates a continuing gap between research prototypes and practical on-site systems.

While Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 summarize the models and datasets used across the reviewed studies, an important limitation identified during screening is the inconsistent methodological rigor among these works. Most CV–based studies rely on custom or small-scale datasets, often below a few thousand labeled images, limiting their generalizability beyond controlled settings. Only a small subset of papers, particularly those using hybrid datasets such as Pictor v3 or Roboflow, employed cross-project or multi-environment validation. Similarly, many ML and NLP applications used single region or organization specific data such as OSHA or KALIS databases without independent testing, which constrains transferability to diverse site conditions. Validation strategies also varied widely. Although several studies reported accuracy and F1 scores, few adopted cross validation, external benchmark testing, or uncertainty analysis. Only recent MM and LLM frameworks demonstrated a stronger focus on reproducibility through open-source implementation and multi-dataset testing. This uneven methodological quality highlights the need for standardized datasets, transparent reporting of training and testing splits, and comparative benchmarks to enable reproducible and scalable AI-based safety systems.

Another major difference identified in this review concerns the rise of MM and integrative approaches. Earlier studies tended to examine ML, NLP, and the IoT as separate research areas. The present analysis shows a recent shift toward integrated frameworks where visual, textual, and sensor data are analyzed together to improve contextual awareness and decision making. This represents a movement from task-specific models toward connected safety ecosystems that can perceive and interpret multiple types of information simultaneously. However, such integration remains at an early stage, and very few studies have tested these systems in real environments. The lack of evaluation on data synchronization and real-time interoperability suggests a clear mismatch between the conceptual ambition of MM AI and its practical readiness.

The results of this review also extend beyond describing technological trends. The synthesis links AI techniques, data sources, and safety functions to the level of evidence supporting their validation. Unlike earlier reviews, this work organizes and compares how each AI category contributes to specific safety goals such as hazard detection, predictive analytics, and compliance monitoring. This structure highlights that current challenges are not only technical but also organizational, ethical, and infrastructural. Limited data sharing, insufficient standardization, and weak integration with management systems continue to restrict progress. The analysis also reveals that most reported models remain at experimental or pilot stages, which limits scalability and reproducibility.

This review contributes to the field by providing a comprehensive and critical framework for understanding how AI supports construction safety. It explains that future progress depends on creating explainable, scalable, and human-centered AI systems that are consistent with site practices and ethical standards. Achieving this goal requires collaborative efforts among engineers, safety managers, and policymakers to ensure that AI tools are transparent, interoperable, and aligned with data governance principles. The insights presented here provide a foundation for the next generation of intelligent, trustworthy, and sustainable safety management systems in the construction industry.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review synthesized evidence from 122 peer-reviewed studies to evaluate how Artificial Intelligence contributes to construction safety management, guided by four RQs addressing techniques (RQ1), data modalities (RQ2), challenges (RQ3), and effectiveness and future directions (RQ4).

For RQ1, the review shows that AI applications in construction safety are mainly based on ML and DL approaches. CNN, YOLO frameworks, and recurrent models are widely used for tasks such as hazard recognition, PPE monitoring, and worker activity analysis. Traditional algorithms, including SVM, RF, and DT models, continue to perform effectively for structured data such as inspection records, injury reports, and sensor readings. Recent advancements include LLM and MM systems capable of processing visual, textual, and audio data, reflecting a growing shift toward integrated and intelligent safety management frameworks.

In response to RQ2, DL and object detection models consistently demonstrate high accuracy and precision in image-based hazard detection and compliance monitoring. Models such as logistic regression and deep neural networks show strong predictive capacity for accident severity and injury classification, while natural language models display promising performance in interpreting unstructured safety narratives. Despite these advances, many studies rely on limited or single-source datasets, which restricts generalization and scalability. This gap emphasizes the need for standardized evaluation methods and large-scale, cross-project validation to ensure consistency and reliability in model performance.

Regarding RQ3, several challenges continue to limit the integration of artificial intelligence into real-world construction safety management. Data scarcity and imbalance, along with privacy concerns in video and wearable monitoring, remain significant obstacles. Limited interoperability between AI tools and existing safety management systems, as well as the shortage of skilled professionals to maintain and interpret AI outputs, further constrain implementation. Many models still function as black boxes, which reduces transparency and user trust. Addressing these challenges requires coordinated efforts to promote open data practices, transparent model design, and cross-disciplinary collaboration between researchers, technology developers, and safety practitioners.

Finally, RQ4 highlights future directions and opportunities for advancing the role of AI in construction safety. The next phase of research should emphasize human-centered, explainable, and MM AI systems that integrate data from cameras, sensors, and textual reports to provide comprehensive and real-time risk assessment. The combination of AI with BIM, extended reality, and wearable technologies can strengthen proactive hazard identification and on-site decision-making. Future work should prioritize system scalability, continuous learning, and trust-building through interpretable interfaces that enable safety managers to make informed and timely decisions.

This review makes a unique contribution by integrating fragmented research into a structured framework that links AI methods, data modalities, and safety functions with their maturity levels. It identifies critical research gaps, including limited exploration of textual and audio data, insufficient MM fusion, and a lack of real-world validation across diverse construction environments. Future research should focus on creating standardized, multimodal datasets, promoting cross-site validation, and embedding explainable, human-centered AI frameworks aligned with ethical and regulatory standards. Advancing these priorities will help transition AI in construction safety from experimental innovation toward practical, transparent, and industry-ready implementation.

Moving forward, the integration of multi-source data, combining imagery, textual records, sensor logs, and physiological signals, will be essential to develop more comprehensive and resilient AI models. Future research should prioritize real-world validation studies, particularly in partnership with industry and public agencies, to test model robustness under dynamic site conditions. There is also a need for the development of policy and ethical frameworks to guide responsible AI deployment, including standards for data privacy, transparency, and worker engagement. Moreover, XAI techniques, human-in-the-loop systems, and user-centered dashboards can enhance trust and usability. By focusing on these areas, future efforts can shift AI in construction safety from experimental innovation to operational impact.

While this review focuses on worker-centric safety solutions, advances in structural safety research offer transferable insights. For example, ML models for seismic risk prediction of reinforced concrete and buckling-restrained braced frames accurately estimate fragility, interstory drift, and failure probabilities, illustrating how AI captures complex risk dynamics under uncertainty [134,135]. Drawing on such methodologies may inspire interdisciplinary frameworks that jointly address structural and worker safety, enabling more integrated and resilient AI-based safety systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/buildings15224084/s1, Table S1: PRISMA checklist. Reference [136] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.J.B. and R.S.; methodology, S.J.B. and R.S.; validation, S.J.B. and R.S.; formal analysis, S.J.B.; data curation, S.J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.J.B.; writing—review and editing, S.J.B. and R.S.; visualization, S.J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kang, Y.; Siddiqui, S.; Suk, S.J.; Chi, S.; Kim, C. Trends of Fall Accidents in the U.S. Construction Industry. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2017, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Xu, P.; Chen, N. Applicability of accident analysis methods to Chinese construction accidents. J. Saf. Res. 2019, 68, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winge, S.; Albrechtsen, E. Accident types and barrier failures in the construction industry. Saf. Sci. 2018, 105, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingard, H. Occupational health and safety in the construction industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2013, 31, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.S.; Wang, X.; Daw, C.; Ringen, K. Chronic Diseases and Functional Limitations Among Older Construction Workers in the United States. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2011, 53, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities. 2025. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/iif/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Rabbi, A.B.K.; Jeelani, I. AI integration in construction safety: Current state, challenges, and future opportunities in text, vision, and audio based applications. Autom. Constr. 2024, 164, 105443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.T.T.L.; Rafieizonooz, M.; Han, S.; Lee, D.E. Current Status and Future Directions of Deep Learning Applications for Safety Management in Construction. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poh, C.Q.; Ubeynarayana, C.U.; Goh, Y.M. Safety leading indicators for construction sites: A machine learning approach. Autom. Constr. 2018, 93, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Han, S.; Lee, S.; Kim, H. Computer vision techniques for construction safety and health monitoring. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2015, 29, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrutika; Patel, K.; Patel, D.B. Enhancing Construction Site Safety: Natural Language Processing for Hazards Identification and Prevention. J. Eng. Proj. Prod. Manag. 2024, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awolusi, I.; Nnaji, C.; Marks, E.; Hallowell, M. Enhancing Construction Safety Monitoring through the Application of Internet of Things and Wearable Sensing Devices: A Review. In Proceedings of the Computing in Civil Engineering 2019, Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–19 June 2019; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2019; pp. 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Sultan, A. AI for Improving Construction Safety: A Systematic. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Associated Schools of Construction International Conference, Liverpool, UK, 3–5 April 2023; Volume 4, pp. 354–362. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, H.; Hallowell, M.R.; Tixier, A.J.P. AI-based prediction of independent construction safety outcomes from universal attributes. Autom. Constr. 2020, 118, 103146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Hu, X.; Hou, J.; Li, X. Application of machine learning techniques for predicting the consequences of construction accidents in China. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 145, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.G.; Choi, B.; Jebelli, H.; Lee, S. Assessment of construction workers’ perceived risk using physiological data from wearable sensors: A machine learning approach. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 42, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.S.; Shen, S.L.; Zhou, A.; Xu, Y.S. Risk assessment and management of excavation system based on fuzzy set theory and machine learning methods. Autom. Constr. 2021, 122, 103490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.C.; Shariatfar, M.; Rashidi, A.; Lee, H.W. Evidence-driven sound detection for prenotification and identification of construction safety hazards and accidents. Autom. Constr. 2020, 113, 103127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhakarmi, S.; Park, J.; Cho, C. Enhanced Machine Learning Classification Accuracy for Scaffolding Safety Using Increased Features. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2019, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B.; Pan, X.; Love, P.E.; Ding, L.; Fang, W. Deep learning and network analysis: Classifying and visualizing accident narratives in construction. Autom. Constr. 2020, 113, 103089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubaiyat, A.H.M.; Toma, T.T.; Kalantari-Khandani, M.; Rahman, S.A.; Chen, L.; Ye, Y.; Pan, C.S. Automatic Detection of Helmet Uses for Construction Safety. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on Web Intelligence Workshops (WIW), Omaha, NE, USA, 13–16 October 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.Y.; Kusoemo, D.; Gosno, R.A. Text mining-based construction site accident classification using hybrid supervised machine learning. Autom. Constr. 2020, 118, 103265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Zhong, B.; Wang, Y.; Shen, L. Identification of accident-injury type and bodypart factors from construction accident reports: A graph-based deep learning framework. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 54, 101752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Jiao, P. Building Construction Safety Monitoring and Early Warning System Based on AI Technology. In Smart Infrastructures in the IoT Era; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, C. Deep Learning and Text Mining: Classifying and Extracting Key Information from Construction Accident Narratives. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.; Kim, J.; Park, S.; Ahn, C.R.; Oh, T. Harnessing Generative Pre-Trained Transformers for Construction Accident Prediction with Saliency Visualization. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, Y.M.; Ubeynarayana, C. Construction accident narrative classification: An evaluation of text mining techniques. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2017, 108, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, Z.; Chen, H.; Luo, X. Transfer learning and deep convolutional neural networks for safety guardrail detection in 2D images. Autom. Constr. 2018, 89, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Xiong, X.; Li, Y.; He, W.; Li, P.; Zheng, X. Detecting safety helmet wearing on construction sites with bounding-box regression and deep transfer learning. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2021, 36, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Xu, S.; Wang, Y.; Shi, L. An Advanced Deep Learning Approach for Safety Helmet Wearing Detection. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Internet of Things (iThings) and IEEE Green Computing and Communications (GreenCom) and IEEE Cyber, Physical and Social Computing (CPSCom) and IEEE Smart Data (SmartData), Atlanta, GA, USA, 14–17 July 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Fleyeh, H.; Wang, X.; Lu, M. Construction site accident analysis using text mining and natural language processing techniques. Autom. Constr. 2019, 99, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Dou, H.; Jian, W.; Guo, C.; Sun, Y. Spatial prediction of the geological hazard vulnerability of mountain road network using machine learning algorithms. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchala, A.K.; Kishore, V.V. Advancements in Machine Learning and Data Mining Techniques for Collision Prediction and Hazard Detection in Internet of Vehicles. Passer J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zhuang, X.; Zuo, H.; Wang, H.; Yan, H. Deep Learning-Based Approach for Civil Aircraft Hazard Identification and Prediction. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 103665–103683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanos, A.M.; Pradhan, B.; Alamri, A.; Lee, C.W. Machine Learning-Based and 3D Kinematic Models for Rockfall Hazard Assessment Using LiDAR Data and GIS. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Ma, T. Mapping of highway slope hazard susceptibility based on InSAR and machine learning: A pilot study toward road infrastructure resilience. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2024, 26, 1974–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawad, H.; Kaewunruen, S.; An, M. Learning From Accidents: Machine Learning for Safety at Railway Stations. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 633–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamkademe, H.A.; Naddami, A.; Choukri, K. Predictive Analysis of Causal Factors Influencing Occupational Accidents in Construction Workplaces Using a Machine Learning Unified Data Model. Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayyeri, H.; Xu, L.; Dehrashid, A.A.; Khanghah, P.M. A development in the approach of assessing the sensitivity of road networks to environmental hazards using functional machine learning algorithm and fractal methods. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 28033–28061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, N.D.; Behzadan, A.H.; Paal, S.G. Deep learning for site safety: Real-time detection of personal protective equipment. Autom. Constr. 2020, 112, 103085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, A.; Oyedele, L.; Delgado, J.M.D.; Akanbi, L.; Bilal, M.; Akinade, O.; Olawale, O. Big data platform for health and safety accident prediction. World J. Sci. Technol. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 16, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, A.; Oyedele, L.; Akinade, O.; Bilal, M.; Owolabi, H.; Akanbi, L.; Delgado, J.M.D. Optimised Big Data analytics for health and safety hazards prediction in power infrastructure operations. Saf. Sci. 2020, 125, 104656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, M.Z. Can past failures help identify vulnerable bridges to extreme events? A biomimetical machine learning approach. Eng. Comput. 2021, 37, 1099–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tixier, A.J.P.; Hallowell, M.R.; Rajagopalan, B.; Bowman, D. Application of machine learning to construction injury prediction. Autom. Constr. 2016, 69, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.; Ryu, H. Predicting types of occupational accidents at construction sites in Korea using random forest model. Saf. Sci. 2019, 120, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, F.; Hajializadeh, D. Bridge seismic hazard resilience assessment with ensemble machine learning. Structures 2022, 38, 719–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, A.; Oyedele, L.; Owolabi, H.; Akinade, O.; Bilal, M.; Delgado, J.M.D.; Akanbi, L. Deep Learning Models for Health and Safety Risk Prediction in Power Infrastructure Projects. Risk Anal. 2020, 40, 2019–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Mikhaylov, A.; Kim, K. Machine Learning Approach in Heterogeneous Group of Algorithms for Transport Safety-Critical System. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Li, X. Novel Unsupervised Machine Learning Method for Identifying Falling from Height Hazards in Building Information Models through Path Simulation Sampling. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2024, 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smetana, M.; de Salles, L.S.; Sukharev, I.; Khazanovich, L. Highway Construction Safety Analysis Using Large Language Models. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tixier, A.J.P.; Hallowell, M.R.; Rajagopalan, B.; Bowman, D. Construction Safety Clash Detection: Identifying Safety Incompatibilities among Fundamental Attributes using Data Mining. Autom. Constr. 2017, 74, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokor, A.; Naganathan, H.; Chong, W.K.; Asmar, M.E. Analyzing Arizona OSHA Injury Reports Using Unsupervised Machine Learning. Procedia Eng. 2016, 145, 1588–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Lv, Z. Real-Time Intelligent Automatic Transportation Safety Based on Big Data Management. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 9702–9711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Zhang, S.; Xiu, W. Solving the Security Problem of Intelligent Transportation System with Deep Learning. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 22, 4281–4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shohet, I.M.; Luzi, M.; Tarshish, M. Optimal allocation of resources in construction safety: Analytical-empirical model. Saf. Sci. 2018, 104, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajizadeh, S.; Núñez, A.; Tax, D.M. Semi-supervised Rail Defect Detection from Imbalanced Image Data. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2016, 49, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanti, M.Z.; Cho, C.S.; Byon, Y.J.; Yeun, C.Y.; Kim, T.Y.; Kim, S.K.; Altunaiji, A. A Novel Implementation of an AI-Based Smart Construction Safety Inspection Protocol in the UAE. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 166603–166616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, S. Construction Site Safety Management: A Computer Vision and Deep Learning Approach. Sensors 2023, 23, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Yu, Q.; Law, K.H.; McKenna, F.; Yu, S.X.; Taciroglu, E.; Zsarnóczay, A.; Elhaddad, W.; Cetiner, B. Machine learning-based regional scale intelligent modeling of building information for natural hazard risk management. Autom. Constr. 2021, 122, 103474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M, W.; P, W.; H, L.; S, K.; V, D.; J, C. Predicting safety hazards among construction workers and equipment using computer vision and deep learning techniques. In Proceedings of the ISARC—International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction, Banff, AB, Canada, 21–24 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, B.; Pan, X.; Love, P.E.; Sun, J.; Tao, C. Hazard analysis: A deep learning and text mining framework for accident prevention. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2020, 46, 101152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, K.; Le, T. A Novel Audio-Based Machine Learning Model for Automated Detection of Collision Hazards at Construction Sites. In Proceedings of the ISARC—International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction, Online, 27–28 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Alateeq, M.M.; Rajeena, F.P.P.; Ali, M.A.S. Construction Site Hazards Identification Using Deep Learning and Computer Vision. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, D.; Li, M.; Han, S.; Shen, Y. A Novel and Intelligent Safety-Hazard Classification Method with Syntactic and Semantic Features for Large-Scale Construction Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elelu, K.; Le, T.; Le, C. Collision Hazard Detection for Construction Worker Safety Using Audio Surveillance. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, A.; Morgado-Dias, F. Deep Learning-Based Automatic Safety Helmet Detection System for Construction Safety. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; El-Gohary, N. Deep learning-based relation extraction and knowledge graph-based representation of construction safety requirements. Autom. Constr. 2023, 147, 104696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wei, H.; Han, Z.; Huang, J.; Wang, W. Deep Learning-Based Safety Helmet Detection in Engineering Management Based on Convolutional Neural Networks. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 9703560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Zeng, X. Deep Learning-Based Workers Safety Helmet Wearing Detection on Construction Sites Using Multi-Scale Features. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 718–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinsemoyin, A.; Awolusi, I.; Chakraborty, D.; Al-Bayati, A.J.; Akanmu, A. Unmanned Aerial Systems and Deep Learning for Safety and Health Activity Monitoring on Construction Sites. Sensors 2023, 23, 6690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Park, M.; Tran, D.Q.; Lee, S.; Park, S. Automated construction safety reporting system integrating deep learning-based real-time advanced detection and visual question answering. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2024, 198, 103779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, Q.; Cao, W.; Yang, J.; Xiong, J.; Gui, G. Deep Learning for Risk Detection and Trajectory Tracking at Construction Sites. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 30905–30912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhi, V.S.K.; Sankarlal, R.; Thomas, A. Detection of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Compliance on Construction Site Using Computer Vision Based Deep Learning Techniques. Front. Built Environ. 2020, 6, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; El-Gohary, N. Deep Learning–Based Named Entity Recognition and Resolution of Referential Ambiguities for Enhanced Information Extraction from Construction Safety Regulations. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2023, 37, 04023023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Cai, N.; Chen, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, G. Automatic detection of hardhats worn by construction personnel: A deep learning approach and benchmark dataset. Autom. Constr. 2019, 106, 102894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Li, H.; Luo, X.; Ding, L.; Rose, T.M.; An, W.; Yu, Y. A deep learning-based method for detecting non-certified work on construction sites. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2018, 35, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatas, I. Deep learning-based system for prediction of work at height in construction site. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, N.D.T.; Wong, W.K.; Juwono, F.H.; Sim, Z.A. Safety Helmet Detection Using Deep Learning: Implementation and Comparative Study Using YOLOv5, YOLOv6, and YOLOv7. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Green Energy, Computing and Sustainable Technology (GECOST), Miri Sarawak, Malaysia, 26–28 October 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; El-Gohary, N. Deep Learning-Based Named Entity Recognition from Construction Safety Regulations for Automated Field Compliance Checking. In Proceedings of the Computing in Civil Engineering 2021, Orlando, FL, USA, 12–14 September 2021; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2022; pp. 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulinan, A.S.; Park, M.; Aung, P.P.W.; Cha, G.; Park, S. Advancing construction site workforce safety monitoring through BIM and computer vision integration. Autom. Constr. 2024, 158, 105227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Dong, M.; Fang, T. Automatic detection of falling hazard from surveillance videos based on computer vision and building information modeling. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2022, 18, 1049–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhong, B.; Li, H.; Love, P.; Pan, X.; Zhao, N. Combining computer vision with semantic reasoning for on-site safety management in construction. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 42, 103036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]