Predicting the Tensile Performance of 3D-Printed PE Fibre-Reinforced ECC Based on Micromechanics Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

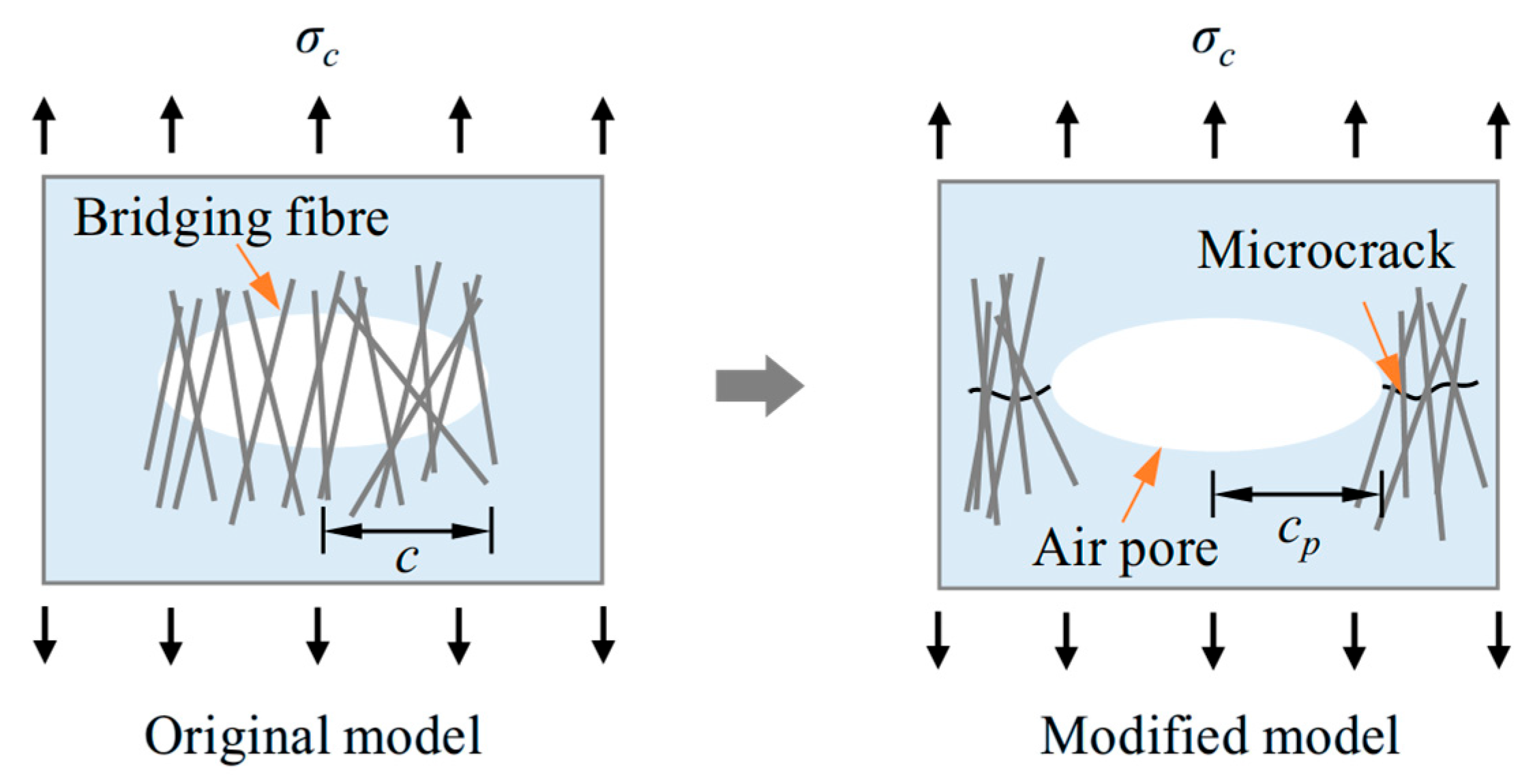

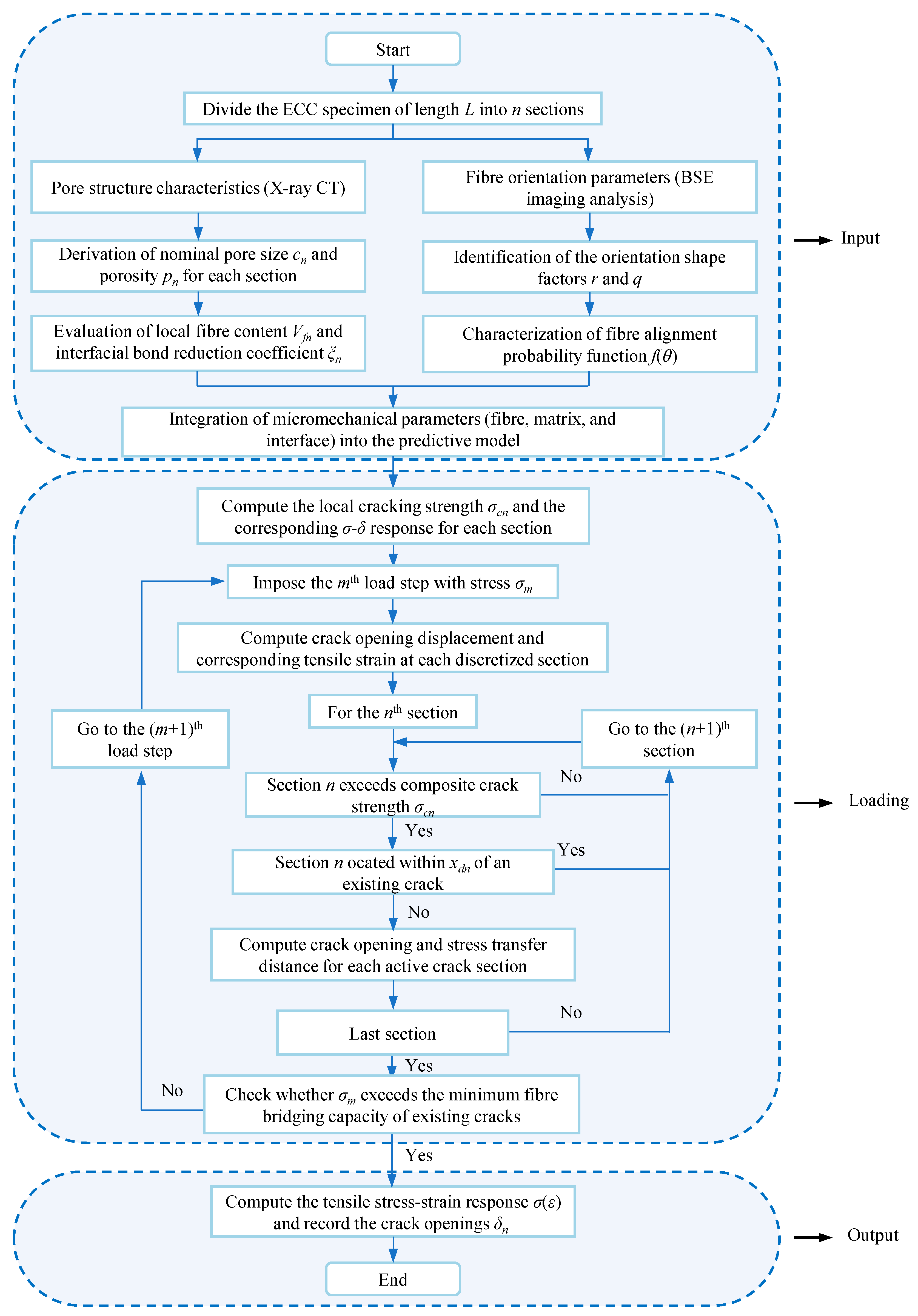

2. Theoretical Basis of the Multiple-Cracking Model

2.1. Cracking Strength

2.2. Bridging Stress–Crack Opening Relationship

2.3. Multiple Cracking Sequence Based on Stress Transfer Mechanism

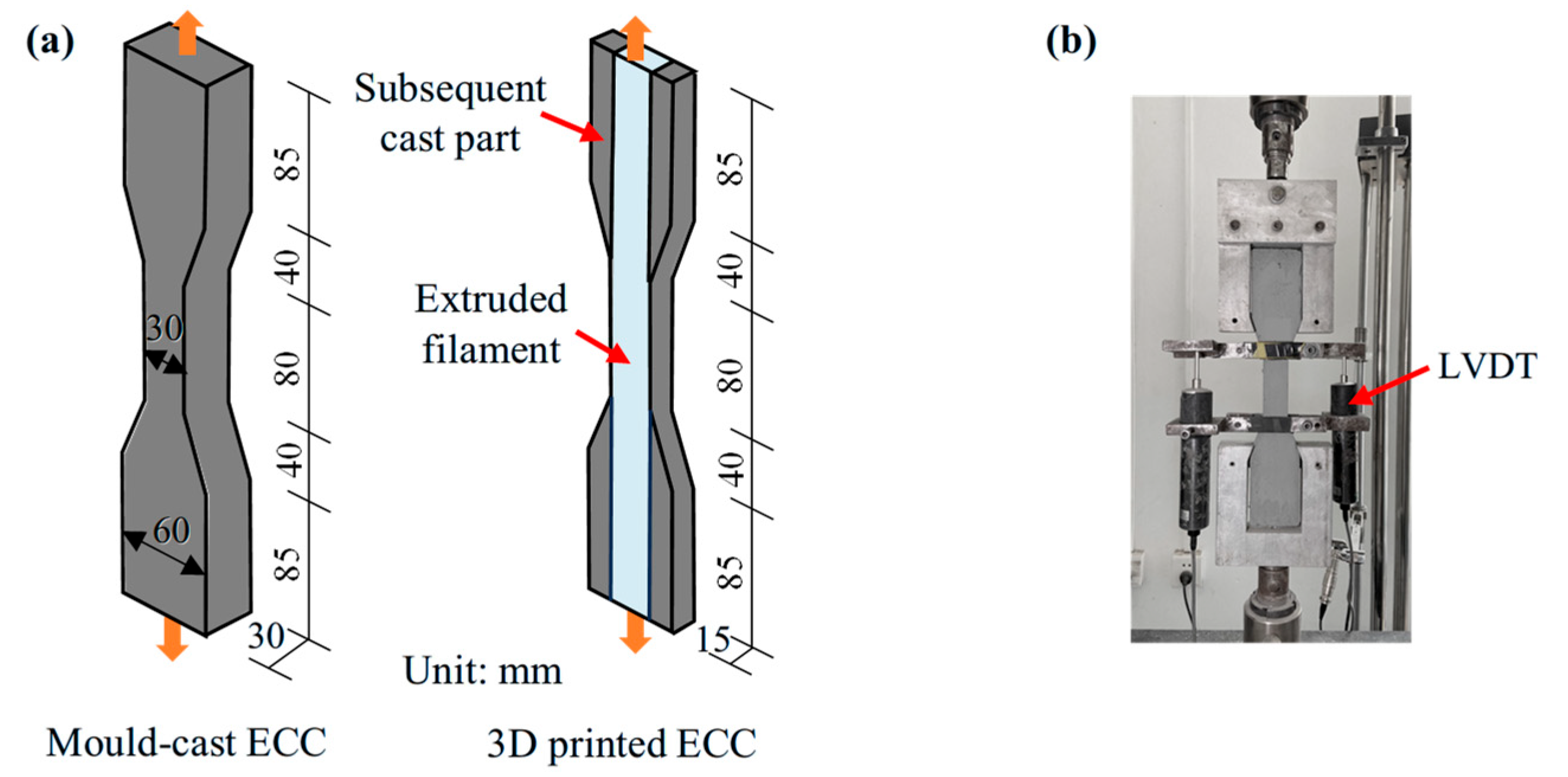

3. Uniaxial Tensile Test of 3D-Printed PE-ECC

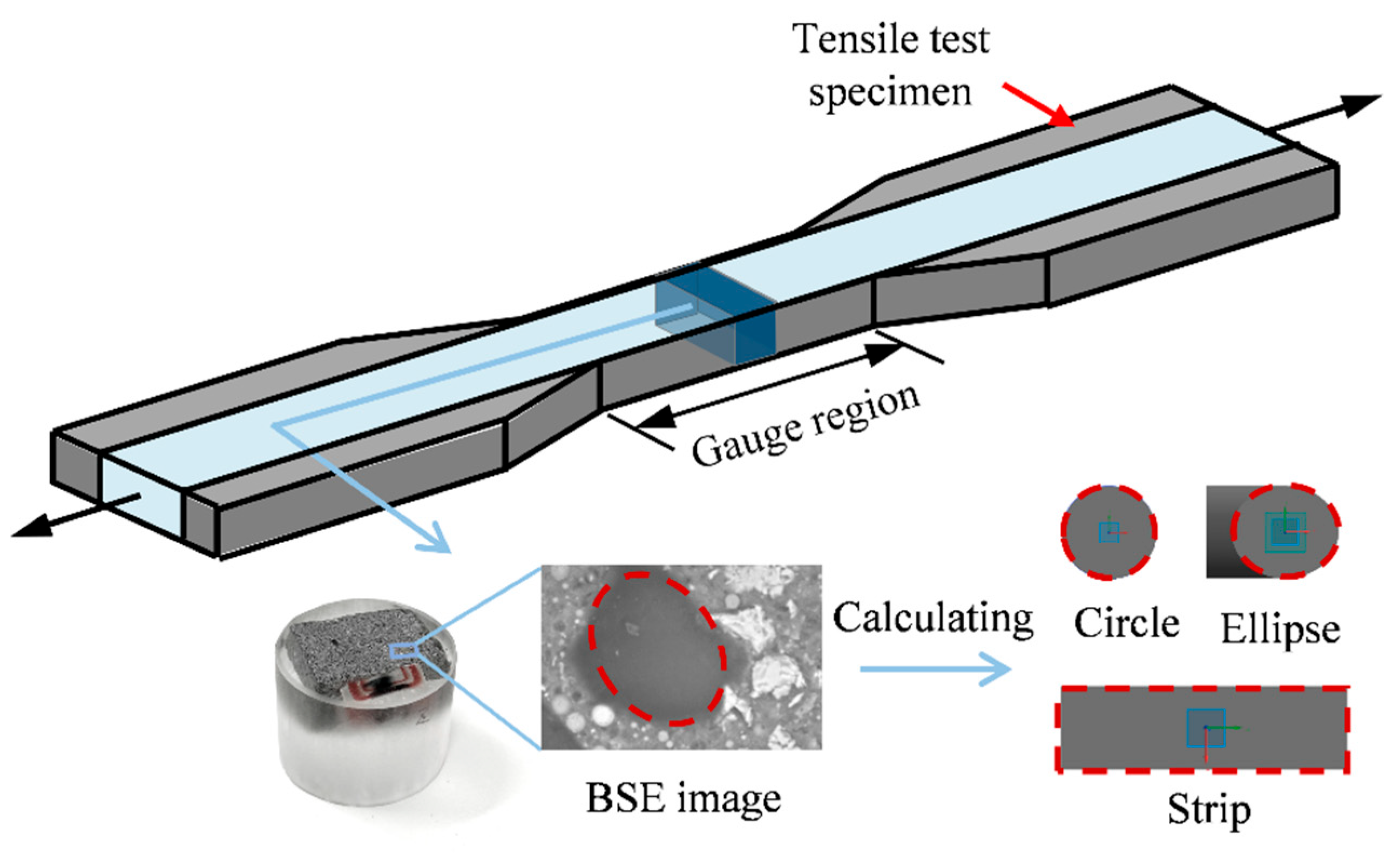

4. Quantification of Micromechanical Parameters for Model Implementation

5. Tensile Performance Prediction of 3DP-ECC

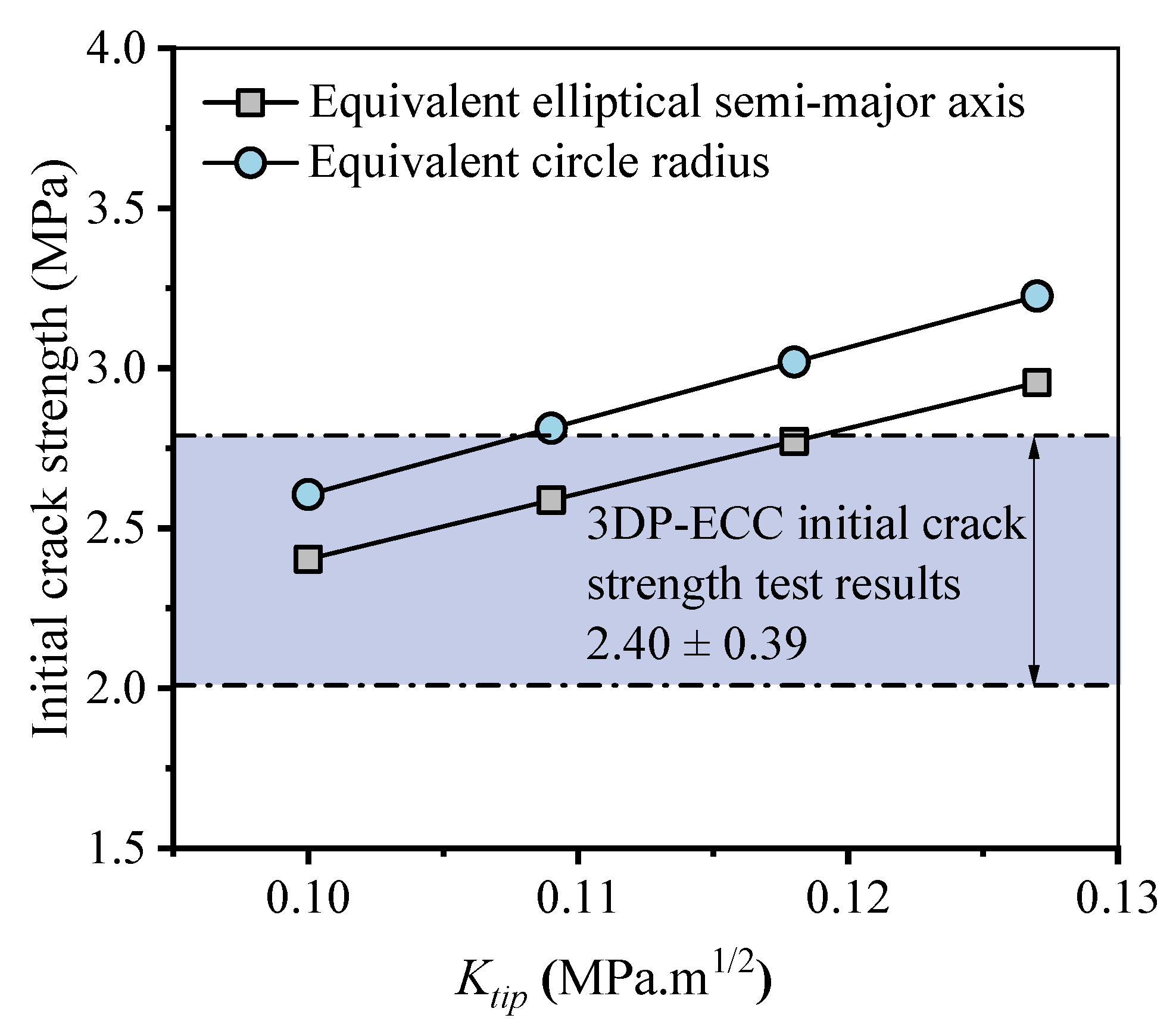

5.1. Cracking Strength Calculation

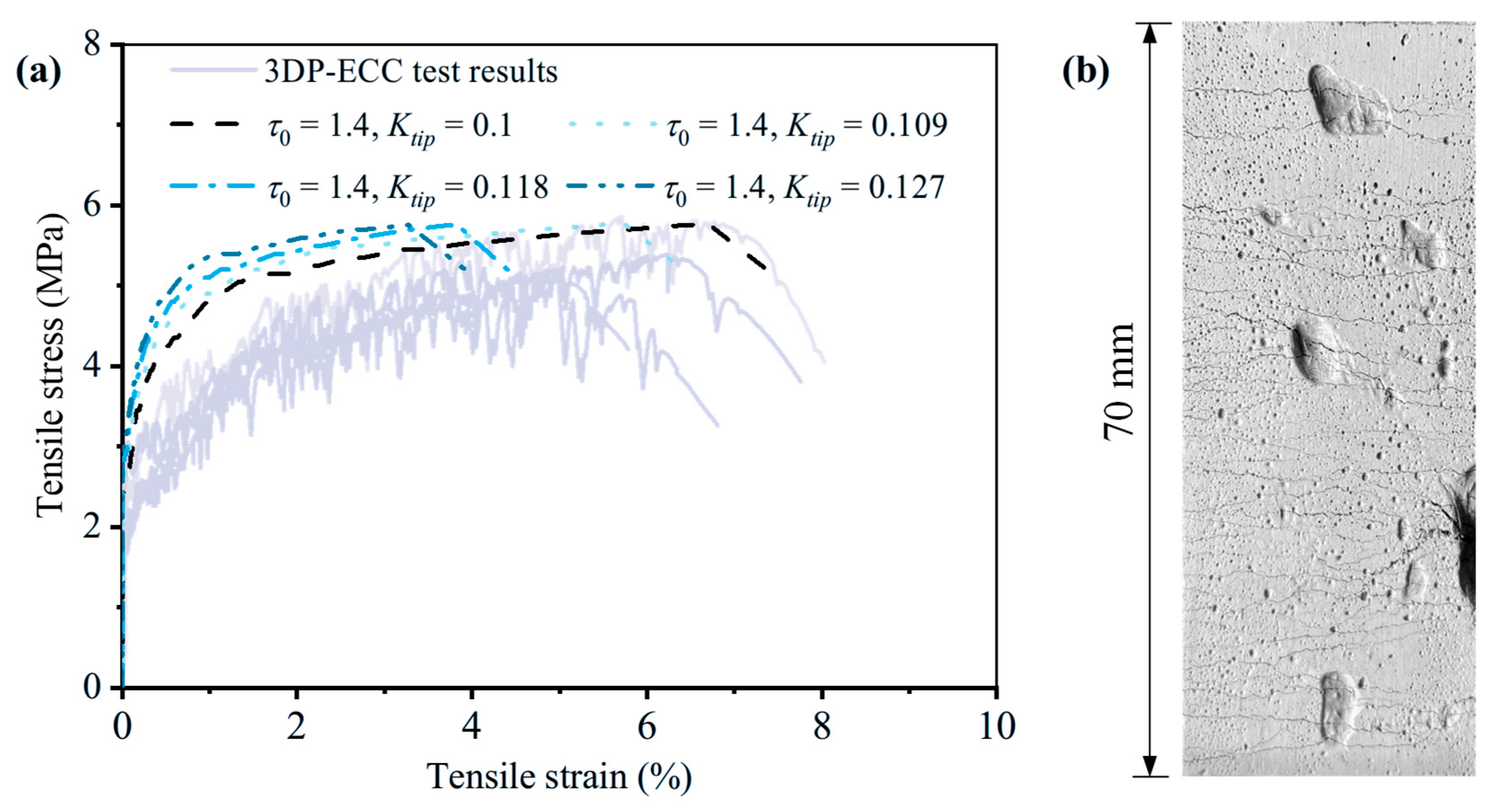

5.2. Stress–Strain Curve Prediction

6. Conclusions

- (1)

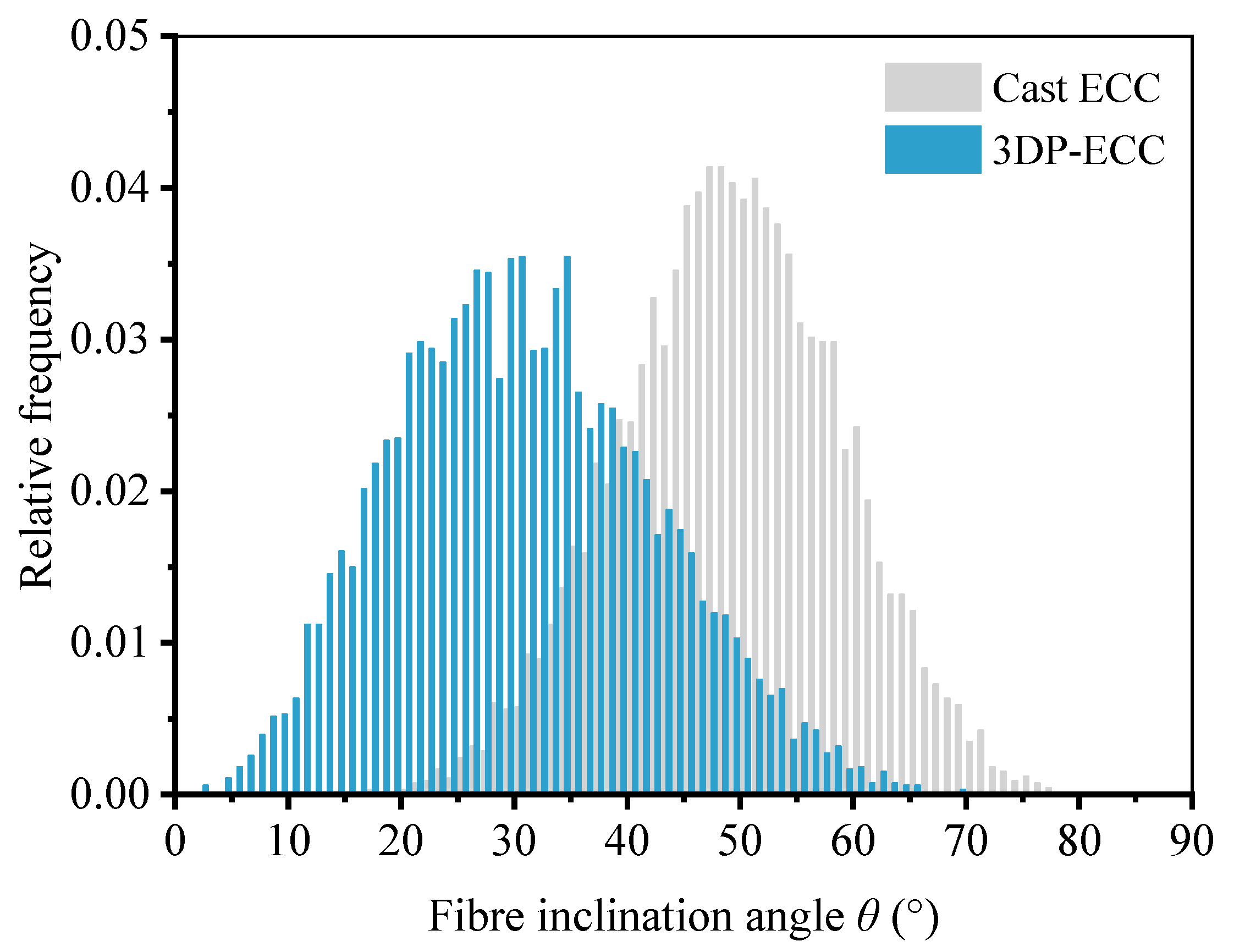

- BSE image analysis showed that the average fibre inclination angle of cast ECC was 47.7°, about 58% higher than that of 3D-printed ECC, indicating that the printing process promotes fibre alignment along the loading direction, thereby improving fibre utilization efficiency.

- (2)

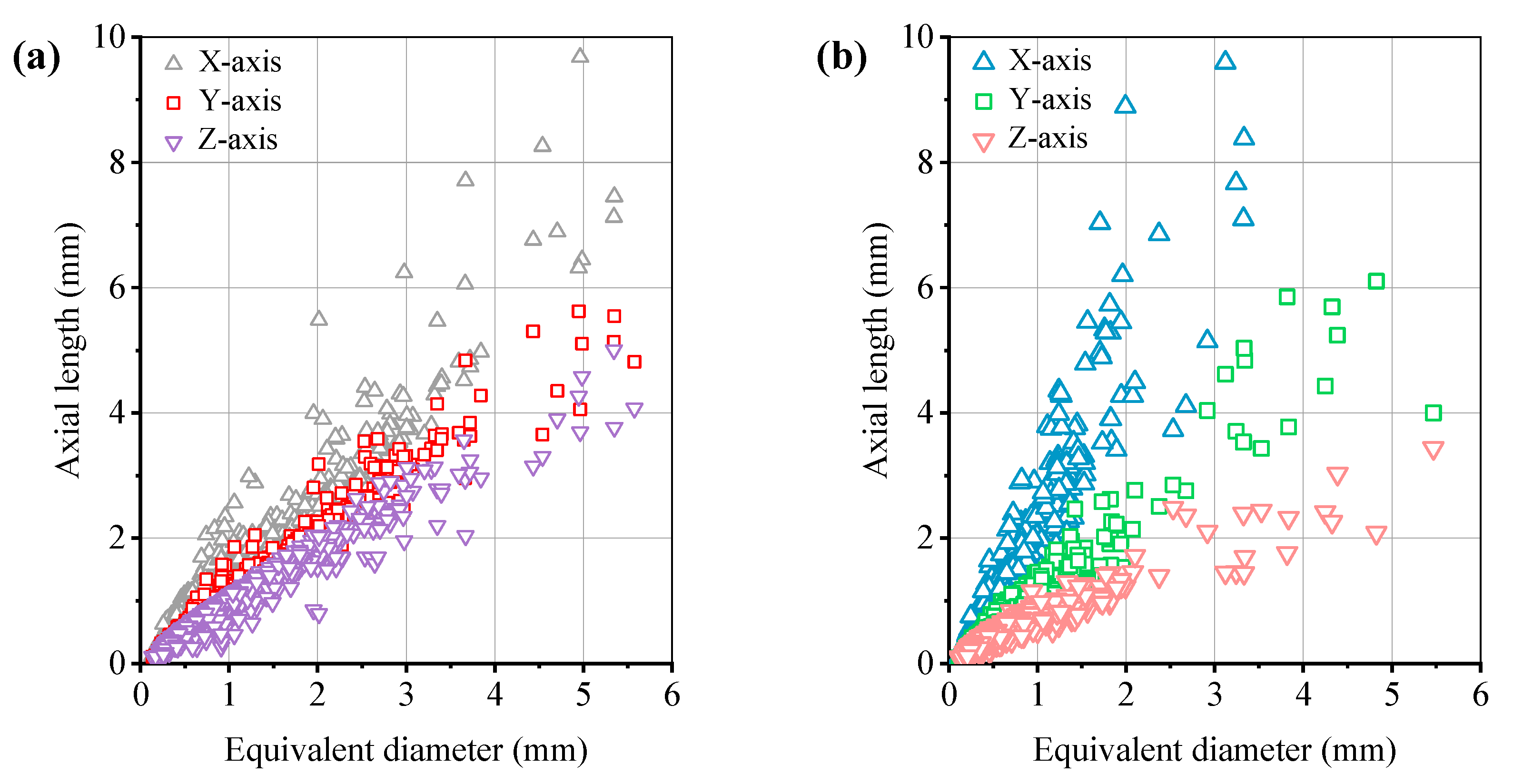

- X-CT scanning revealed that the pore axial lengths in both types of ECC followed the trend x-axis > y-axis > z-axis. Compared with cast ECC, 3D-printed ECC exhibited more pronounced pore anisotropy, with pores shaped more like elongated flattened ellipsoids. Therefore, using the equivalent elliptical semi-major axis as the characteristic pore size is more appropriate for predicting tensile behaviour.

- (3)

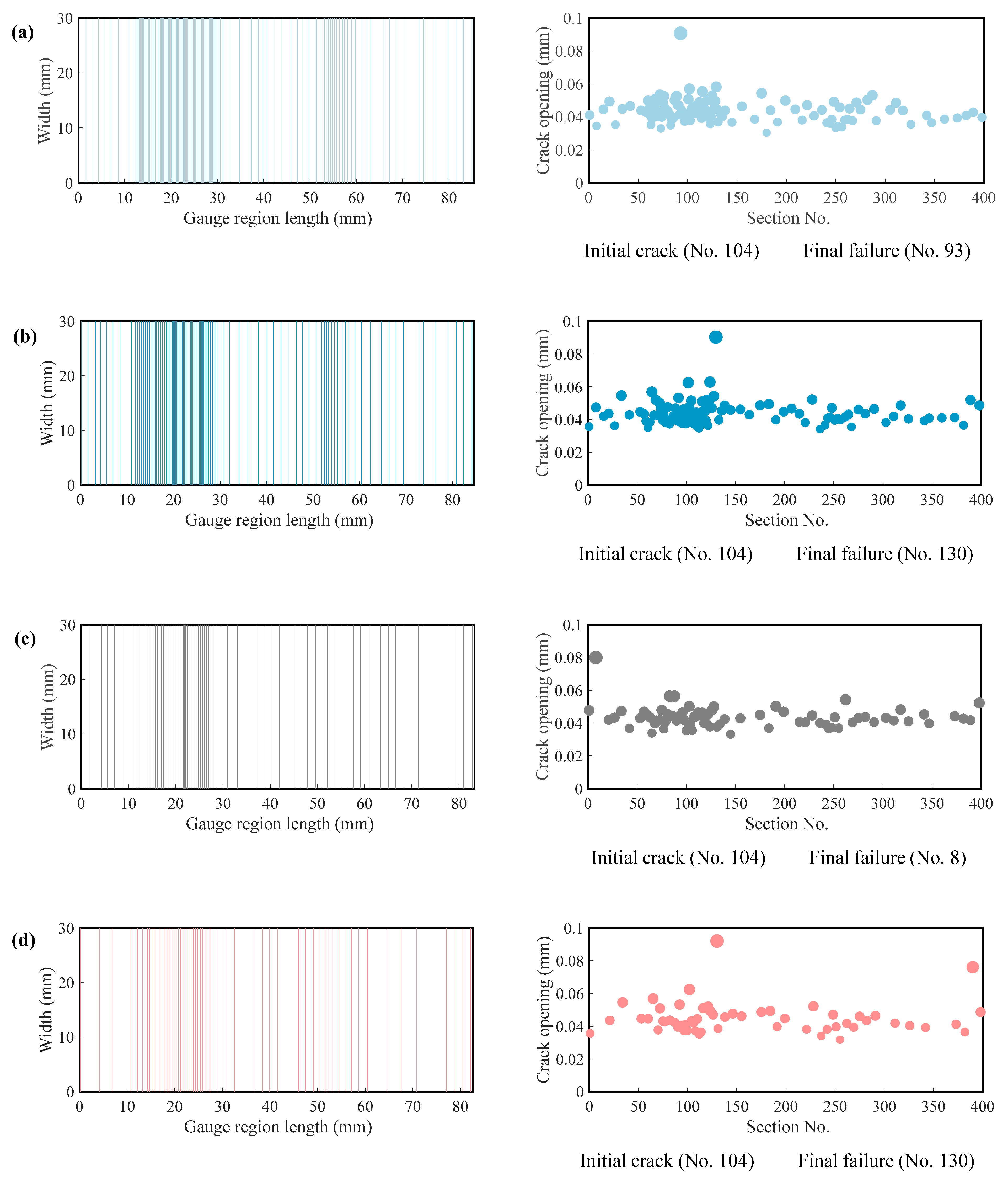

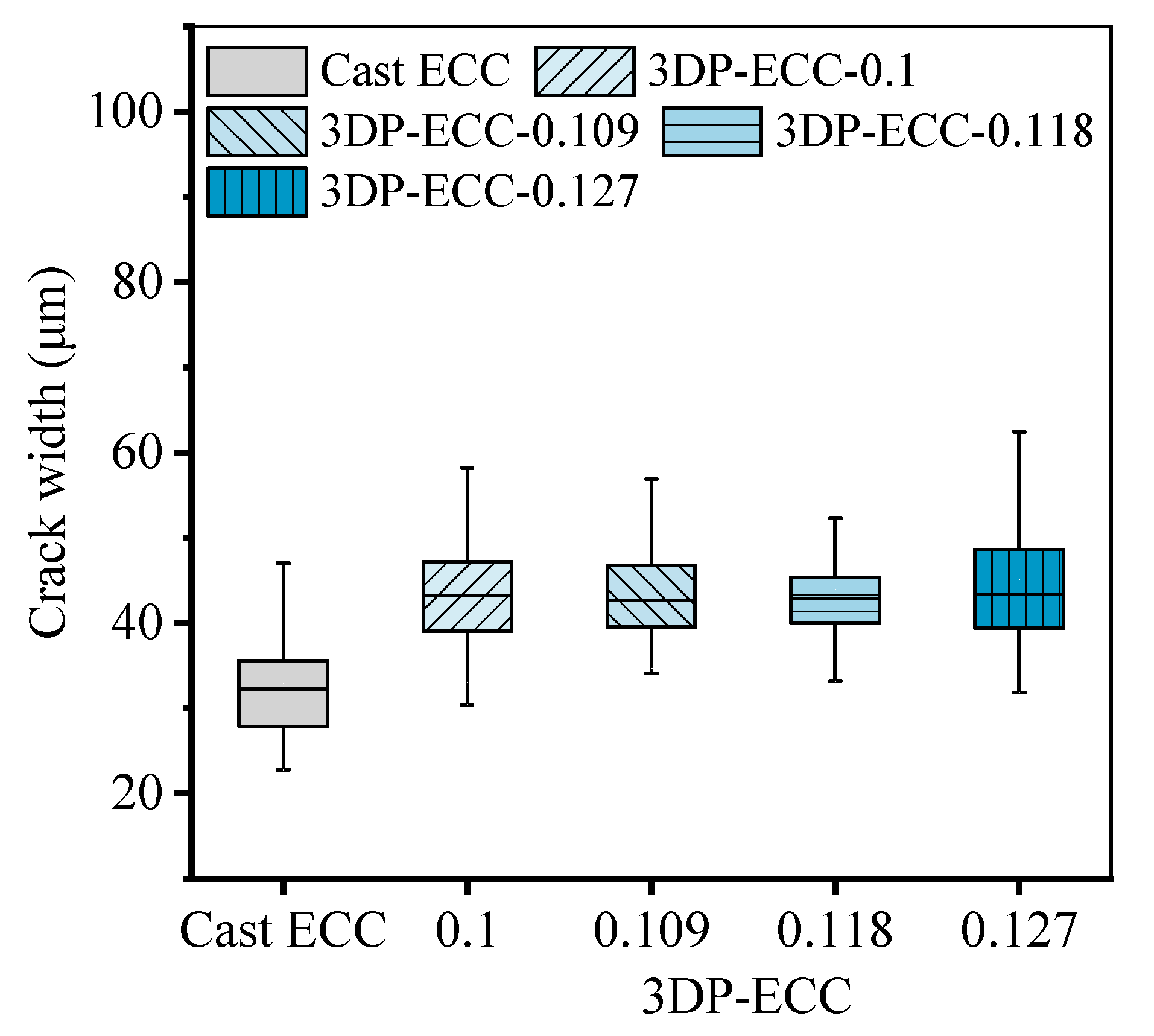

- The stochastic predictive model established based on the measured microstructural parameters successfully captured the cracking sequence, stress–strain curves, and crack width distribution of 3D-printed ECC. By incorporating pore morphology into an equivalent elliptical model, the predicted cracking strength showed excellent agreement with the experimental results, validating the effectiveness of the microstructural parameters in tensile performance prediction.

- (4)

- The 3D printing process enhanced the interfacial bonding to some extent, which helped maintain the multiple-cracking behaviour and improve strain-hardening capacity. The superior ductility of 3D-printed ECC compared with cast ECC can be attributed to smaller fibre inclination angles and improved fibre alignment along the loading direction, increased interfacial frictional bond strength induced by the extrusion process, and reduced matrix fracture toughness caused by early moisture loss during printing.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhuang, Z.; Xu, F.; Ye, J.; Hu, N.; Jiang, L.; Weng, Y. A comprehensive review of sustainable materials and toolpath optimization in 3D concrete printing. npj Mater. Sustain. 2024, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, A.; Rajeev, P.; Sanjayan, J.; Mechtcherine, V. In-process textile reinforcement method for 3D concrete printing and its structural performance. Eng. Struct. 2024, 314, 118337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ler, K.H.; Ma, C.K.; Chin, C.L.; Ibrahim, I.S.; Padil, K.H.; Ab Ghafar, M.A.I.; Lenya, A.A. Porosity and durability tests on 3D printing concrete: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 446, 137973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.Y.; Lao, J.C.; Shi, D.D.; Cai, J.; Xie, T.Y.; Huang, B.T. Recent Advances in High-Strength Engineered Geopolymer Composites (HS-EGC): Bridging Sustainable Construction and Resilient Infrastructure. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 165, 106307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, P.; Ling, Z.; Bai, Y.; Lu, W.; Zhang, Y. Ductility Variation and Improvement of Strain-Hardening Cementitious Composites in Structural Utilization. Materials 2024, 17, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Liu, H.; Leung, C.K. Application of high-strength strain-hardening cementitious composites (SHCC) in the design of novel inter-module joint. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 359, 129491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Meng, W.; Khayat, K.H.; Bao, Y.; Guo, P.; Lyu, Z.; Abu-Obeidah, A.; Nassif, H.; Wang, H. New development of ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC). Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 224, 109220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, W. Optimizing ecological ultra-high performance concrete prepared with incineration bottom ash: Utilization of Al2O3 micro powder for improved mechanical properties and durability. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 426, 136152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.Y.; Banthia, N.; Yoon, Y.S. Recent development of innovative steel fibers for ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC): A critical review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 145, 105359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; Chen, R.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y. Study on preparation and mechanical properties of a new type of high-temperature resistant ultra-high performance concrete. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2024, 24, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V.C.; Bos, F.P.; Yu, K.; McGee, W.; Ng, T.Y.; Figueiredo, S.C.; Nefs, K.; Mechtcherine, V.; Nerella, V.N.; Pan, J.; et al. On the emergence of 3D printable engineered, strain hardening cementitious composites (ECC/SHCC). Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 132, 106038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.Y.; Banthia, N. High-performance strain-hardening cementitious composites with tensile strain capacity exceeding 4%: A review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 125, 104325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Overmeir, A.L.; Šavija, B.; Bos, F.P.; Schlangen, E. 3D printable strain hardening cementitious composites (3DP-SHCC), tailoring fresh and hardened state properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 403, 132924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, F.; Xu, F.; Yang, M.; Yu, J.; Zhang, D.; Weng, Y. Development of sustainable strain-hardening cementitious composites containing diatomite for 3D printing. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 103, 112170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.; Qian, Y. Effects of printing patterns and loading directions on fracture behavior of 3D printed Strain-Hardening Cementitious Composites. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2024, 304, 110155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Zhang, J.; Yu, J.; Yu, J.; Yu, K. Flexural behaviors of 3D printed lightweight engineered cementitious composites (ECC) slab with hollow sections. Eng. Struct. 2024, 299, 117113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivaniuk, E.; Eichenauer, M.F.; Tošić, Z.; Müller, S.; Lordick, D.; Mechtcherine, V. 3D printing and assembling of frame modules using printable strain-hardening cement-based composites (SHCC). Mater. Des. 2022, 219, 110757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Qiu, J.; Weng, J.; Yang, E.H. Micromechanics of engineered cementitious composites (ECC): A critical review and new insights. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 362, 129765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.H.; Wang, S.; Yang, Y.; Li, V.C. Fiber-bridging constitutive law of engineered cementitious composites. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2008, 6, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V.C.; Wang, S. Microstructure variability and macroscopic composite properties of high performance fiber reinforced cementitious composites. Probabilistic Eng. Mech. 2006, 21, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikbin, I.M.; Beygi, M.H.A.; Kazemi, M.T.; Amiri, J.V.; Rahmani, E.; Rabbanifar, S.; Eslami, M. Effect of coarse aggregate volume on fracture behavior of self compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 52, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, G.A. Long-term drying shrinkage of mortar—Influence of silica fume and size of fine aggregate. Cem. Concr. Res. 2001, 31, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V.C.; Leung, C.K. Steady-state and multiple cracking of short random fiber composites. J. Eng. Mech. 1992, 118, 2246–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Leung, C.K.; Li, V.C. Numerical model on the stress field and multiple cracking behavior of engineered cementitious composites (ECC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 133, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, J.; Groves, G.W. The effect of metal wires on the fracture of a brittle-matrix composite. J. Mater. Sci. 1976, 11, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T.; Li, V.C. Interface property and apparent strength of high-strength hydrophilic fiber in cement matrix. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 1998, 10, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V.C.; Wang, Y.; Backer, S. A micromechanical model of tension-softening and bridging toughening of short random fiber reinforced brittle matrix composites. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1991, 39, 607–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Hamada, H.; Maekawa, Z. Flexural stiffness of injection molded glass fiber reinforced thermoplastics. Int. Polym. Process. 1995, 10, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun-Felekoğlu, K.; Felekoğlu, B.; Ranade, R.; Lee, B.Y.; Li, V.C. The role of flaw size and fiber distribution on tensile ductility of PVA-ECC. Compos. Part B Eng. 2014, 56, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Weng, J.; Chen, Z.; Yang, E.H. A generic model to determine crack spacing of short and randomly oriented polymeric fiber-reinforced strain-hardening cementitious composites (SHCC). Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 118, 103919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JC/T 2461-2018; Standard Test Method for the Mechanical Properties of Ductile Fiber Reinforced Cementitious Composites. Chinese Standard: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Zhu, B.; Pan, J.; Li, J.; Wang, P.; Zhang, M. Relationship between microstructure and strain-hardening behaviour of 3D printed engineered cementitious composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 133, 104677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Pan, J.; Zhang, M.; Leung, C.K. Predicting the strain-hardening behaviour of polyethylene fibre reinforced engineered cementitious composites accounting for fibre-matrix interaction. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 134, 104770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, E.H.; Guan, X. Investigation of matrix cracking properties of engineered cementitious composites (ECCs) incorporating river sands. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 123, 104204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, E.H. Probabilistic-based assessment for tensile strain-hardening potential of fiber-reinforced cementitious composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 91, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yao, J.; Lin, X.; Li, H.; Lam, J.Y.; Leung, C.K.; Sham, I.M.; Shih, K. Tensile performance of sustainable Strain-Hardening Cementitious Composites with hybrid PVA and recycled PET fibers. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 107, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Thickness (mm) | Binder Materials | Sand | Water | Superplasticizer | HPMC | PE Fibre |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cast-ECC | 30 | 1 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.001 | 0.0004 | 6 mm (1.5%) and 12 mm (0.5%) |

| 3DP-ECC | 15 | 1 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.001 | 0.0004 | 6 mm (1.5%) and 12 mm (0.5%) |

| Preparation Method | Micromechanical Parameters | Observations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fibre | Casting and 3D Printing | lf (mm) | 6 and 12 a |

| Casting and 3D Printing | df (μm) | 23.86 ± 4.44 b | |

| Casting and 3D Printing | Elastic modulus, Ef (GPa) | 110 a | |

| Casting and 3D Printing | Tensile strength, σfu (MPa) | 3000 a | |

| Casting and 3D Printing | Gd (J/m2) | 0 c | |

| Cast-ECC | (r, q) | r = 5, q = 3.8 d | |

| 3DP-ECC | (r, q) | r = 1.7, q = 4.3 d | |

| Matrix | Casting and 3D Printing | Em (GPa) | 18 b |

| Casting and 3D Printing | Ktip (MPa∙m1/2) | 0.118 b | |

| Casting and 3D Printing | Poisson’s ratio, v | 0.2 b | |

| Interface | Cast-ECC | τ0 (MPa) | 1.16 ± 0.3 b |

| 3DP-ECC | τ0 (MPa) | 1.4 e | |

| Casting and 3D Printing | β | 0.004 b | |

| Casting and 3D Printing | f | 0.65 f | |

| Casting and 3D Printing | f’ | 0.50 g | |

| Casting and 3D Printing | γ | 21 h |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, B.; Liu, X.; Wei, Y.; Pan, J. Predicting the Tensile Performance of 3D-Printed PE Fibre-Reinforced ECC Based on Micromechanics Model. Buildings 2025, 15, 4058. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224058

Zhu B, Liu X, Wei Y, Pan J. Predicting the Tensile Performance of 3D-Printed PE Fibre-Reinforced ECC Based on Micromechanics Model. Buildings. 2025; 15(22):4058. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224058

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Binrong, Xuhua Liu, Yang Wei, and Jinlong Pan. 2025. "Predicting the Tensile Performance of 3D-Printed PE Fibre-Reinforced ECC Based on Micromechanics Model" Buildings 15, no. 22: 4058. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224058

APA StyleZhu, B., Liu, X., Wei, Y., & Pan, J. (2025). Predicting the Tensile Performance of 3D-Printed PE Fibre-Reinforced ECC Based on Micromechanics Model. Buildings, 15(22), 4058. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15224058