Abstract

Geopolymers, achieved through geopolymerization of aluminosilicate-containing precursors, are environmentally friendly inorganic binders with excellent mechanical strength, chemical resistance, and low carbon footprint. Beyond construction applications, geopolymers show great potential in environmental protection due to their ability to immobilize hazardous pollutants, adsorb ions and gases, and utilize industrial solid wastes. This review provides a state-of-the-art summary of recent advances in geopolymer applications in environmental fields, including (1) immobilization of hazardous wastes, (2) adsorption of hazardous ions and CO2, and (3) resource utilization of solid wastes through geopolymerization. The mechanisms underlying immobilization and adsorption are discussed, and research gaps and future directions will be highlighted to guide further development of geopolymer-based environmental materials or application of geopolymerization in solid waste utilization.

1. Introduction

Concrete, prepared from cement, sand, and stone, is one of the most widely used construction materials in the world. According to the latest IEA Global Energy Review 2025, global energy-related CO2 emissions reached 37.8 Gt in 2024, remaining at historically high levels despite a slight decline in industrial process emissions [1]. Among these, cement and clinker production—including both the calcination of CaCO3 and fuel combustion—accounts for approximately 5–8% of global anthropogenic CO2 emissions [2]. The direct emissions intensity of cement production has shown only a slow decline in recent years, and under the net-zero scenario, it must fall by over 3% annually to meet climate targets. Therefore, developing alternative low-carbon cementitious binders to mitigate the environmental impact of the construction industry attracts lots of attention [3,4,5].

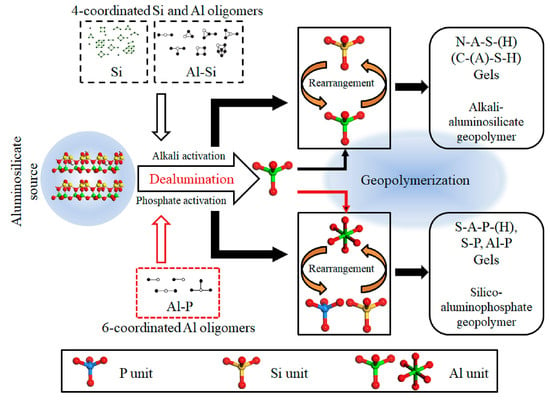

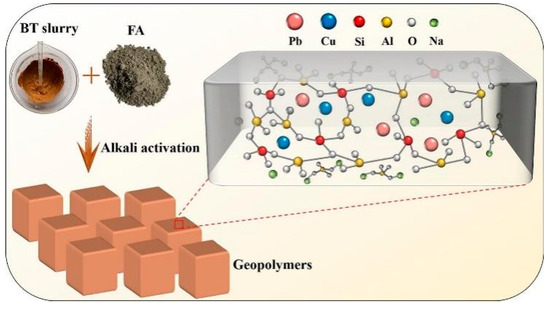

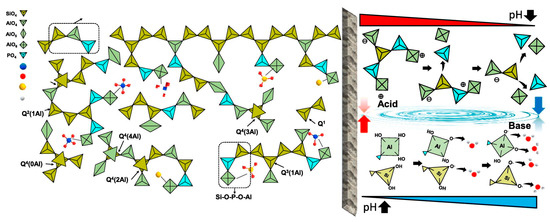

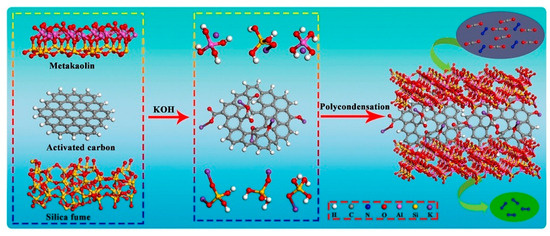

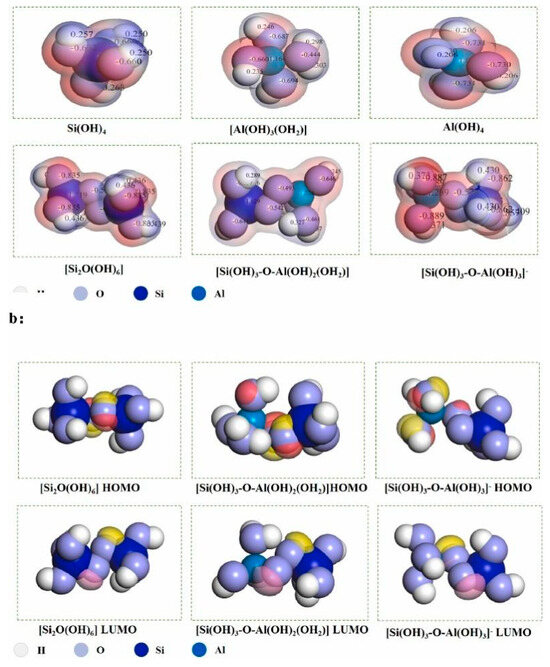

Among these materials, geopolymers—emerging as a kind of green construction material—are prepared from two raw materials: solid precursors rich in silica and alumina (e.g., clay minerals, fly ash (FA), ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS), etc.) [6,7,8], and an activator solution, i.e., an alkali activator (e.g., NaOH and Na2SiO3 solution) [9] or an acid activator (e.g., H3PO4 solutions) [10,11]. The preparation process is just mixing these two raw materials, where raw materials undergo geopolymerization [12]. Depending on the type of activator, geopolymers can be categorized as alkali-activation and acid-activation geopolymer, with different microstructures and chemical compositions (Figure 1) [13,14]. The two activation routes yield geopolymers with distinct three-dimensional network structures and bonding configurations, which directly affect their mechanisms of immobilizing hazardous ions, adsorbing pollutants, and resisting chemical attack. From a sustainability perspective, activators such as NaOH and Na2SiO3 do contribute to some CO2 emissions during production, but several life-cycle analyses have shown that the total carbon footprint of geopolymers remains significantly lower than that of ordinary Portland cement (OPC) [14,15].

Figure 1.

Conceptual scheme for acid- and alkali-activation of an aluminosilicate source to form a geopolymer [16].

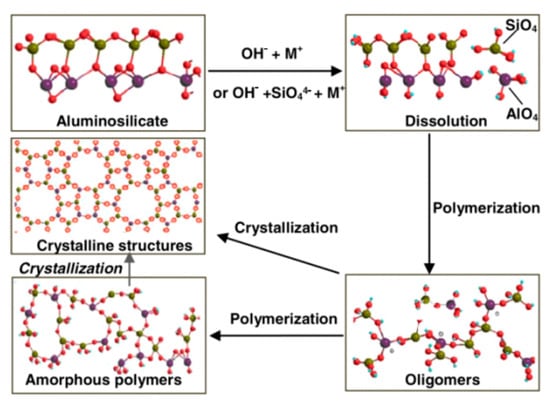

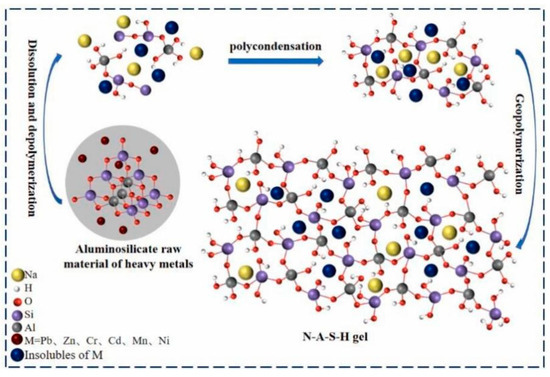

Alkali-activation geopolymers have been widely studied as construction and building materials. In fact, the invention of geopolymer is from the alkali activation of kaolinite by Prof. Davidovits [17]. Alkali-activation geopolymer is composed of randomly distributed [SiO4] and [AlO4] tetrahedra, interconnected by bridging oxygen to create a three-dimensional (3D) network structure, with alkali or alkaline earth metal ions occupying the interstitial spaces to balance the negative charges [18,19]. Van et al. [20] provided a brief summary of the geopolymerization process: under alkaline conditions, the aluminosilicate precursors dissolve, releasing aluminate and silicate monomers. These monomers then diffuse and polymerize to create a gel phase, during which water produced from condensation is expelled throughout the hardening process. Finally, the amorphous geopolymer with Si-O-Al structure is formed, which may be transformed into zeolites under certain conditions (Figure 2).

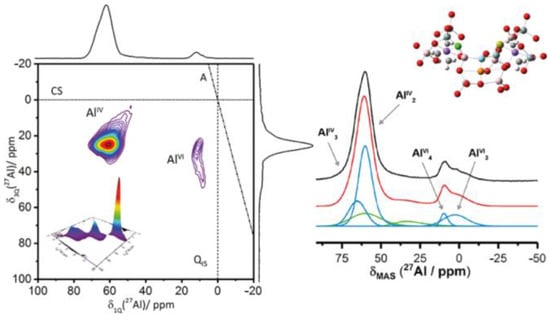

By using advanced technology, the microstructure of alkali-activation geopolymer becomes clearer. Zhang et al. [21] employed environmental scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to quantitatively trace the entire process of generation, development, and evolution of geopolymerization products in KOH-activated metakaolinite (MK)-based geopolymers. They found that in the early stages of hydration, MK particles are loosely packed, resulting in numerous large voids; as the curing time increases, a substantial amount of sponge-like species precipitate on the particle surfaces and expand outward; in later stages, the particles are densely enveloped by the gels, filling the voids and becoming dense. Walkley et al. [22] proposed a new structural model of hydrous alkali aluminosilicate (N-A-S-H) gel frameworks, where the charge-balancing, extra-framework Al species are observed in N-A-S-H gels by the application of 17O, 23Na, and 27Al triple-quantum magic-angle spinning solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (Figure 3). In addition, the utilization of molecular dynamics simulations can provide an in-depth analysis of the molecular structure of geopolymers [23], and X-ray micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) can offer a 3D insight into the microstructure of geopolymers [24].

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the reaction mechanism of alkali-activated geopolymers [25].

Figure 3.

New structure of alkali-activation geopolymers [22].

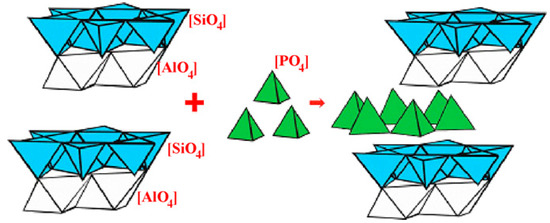

Compared with alkali-activation geopolymer, the studies on acid-activation geopolymer are much later and fewer. In 2002, researchers found that aluminosilicate precursors can also be activated by acid solution, forming an amorphous phase with a network structure of Al-O-P, Si-O-P and Si-O-Al [26]. Normally, MK is the most used precursor, and phosphoric acid solution is the most used acid activator [11,27,28,29]. In recent years, many solid wastes, like FA, mine tailing, etc., have been attempted to be used as precursors [30,31] and phosphate solution (e.g., AlH2PO4) as acid activators [32]. However, the geopolymerization mechanism of acid-activation geopolymers remains unclear due to the insufficient study on acid-based geopolymer. There are three main viewpoints of geopolymerization: (1) Deguang et al. [33] suggested that during the acid activation, the oligomeric P-O tetrahedra in phosphoric acid directly bonds with the reactive Al-O in MK, resulting in a Si-O-Al-O-P network structure (Figure 4); (2) Louati et al. [34,35] divided the acid-based geopolymerization into three steps: firstly, phosphoric acid disrupts the structure of MK, releasing free Al3+; secondly, the phosphate reacts with Al3+ to form AlPO4 and reacts with the de-aluminated kaolinite to generate Si-O-P structures; finally, Si-O-P condenses to form a 3D network structure; (3) Mathivet et al. [36] proposed that phosphoric acid reacts with MK to form Al-O-P and Al-O-Si network structures, along with the presence of amorphous silica gel. Recently, Cui et al. [37] found that the Al dissolved from MK reacts with phosphoric acid, while Si can be incorporated into Al-O-P in the form of amorphous silica to form Si-O-P-O-Al network.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the reaction mechanism of acid-activated geopolymers [37].

As mentioned above, benefiting from their 3D network structure, both alkali- and acid-activation geopolymers exhibit superior properties such as high mechanical strength [38,39], excellent corrosion resistance [40,41], and good fire resistance [42,43], indicating significant application prospects in construction materials, sealing materials, and high-temperature resistant materials. In addition, the energy consumption and CO2 emissions in manufacturing geopolymer are lower than ordinary Portland cement (OPC), which has made them promising alternative materials to OPC [44,45].

Not only the building materials, but also the application of geopolymer as environmental materials or the utilization of geopolymerization for environmental remediation has attracted lots of attention. For example, it is not only highly effective in immobilizing ions, but also in binding sludge particles during geopolymerization, allowing them to replace cement as new encapsulation materials for radioactive nuclear waste [46,47,48]. Moreover, geopolymers feature a zeolite-like structure that demonstrates adsorption properties for heavy metal ions, facilitating the purification of industrial wastewater [49]. More importantly, the utilization of some large amounts of solid wastes can yield high-performance geopolymers, which can further be used for adsorption or other environmental materials, contributing to the high value-added resource utilization of solid wastes [50].

Considering the huge potential of geopolymer in the environmental field, this paper reviews the state-of-the-art applications of geopolymerization technology or geopolymer in environmental remediation (e.g., solid waste utilization) or the obtained geopolymers as environmental materials, which is of practical significance for energy saving, CO2 emission reduction, resource utilization, and environmental protection. This review will provide references for further research and application of geopolymer-based materials in environment, energy, or chemical industry field.

This review focuses on three representative environmental applications of geopolymers: (i) immobilization/stabilization of heavy metals and radioactive wastes, (ii) adsorption of hazardous ions, organic dyes, and CO2, and (iii) resource utilization of solid wastes through geopolymerization. The objective is to summarize recent advances, elucidate underlying mechanisms, and highlight research gaps, rather than to provide an exhaustive survey of every environmental application. Publications were retrieved from major databases (Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar) mainly between 2000 and 2025 using combinations of keywords such as “geopolymer,” “alkali-activated,” “acid-activated,” “immobilization,” “adsorption,” “solid waste,” and “environmental remediation.” Priority was given to peer-reviewed articles that report mechanistic insights, long-term performance data, or novel approaches relevant to environmental protection.

2. Immobilization of Hazardous Pollutant Through Geopolymerization

The productive and social activities of humans have generated lots of waste. For instance, a variety of sludges are generated after wastewater treatment. These sludges are characterized by fine granules, low density, high moisture content, difficulty in dewatering, and a propensity for putrefaction and odor [51]. More importantly, these sludges contain large quantities of heavy metal ions, including Cu2+, Zn2+, Cr2+, and Pb2+, which will pose great risks to human health [52]. For example, numerous countries have established nuclear facilities as nuclear technology advances. However, safety issues such as nuclear leaks caused by natural disasters and the secure storage of nuclear materials remain [53]. Therefore, it will cause severe damage to geological and ecological environments if such hazardous wastes are not properly disposed of.

Traditional binders, like OPC and limestone, have been utilized for solidification/stabilization of solid wastes with hazardous composition (e.g., heavy metal ions, radionuclides, etc.) in a long time. The hydration of cement can bind the particles and retain the hazardous compositions [54,55]. However, many problems have emerged over time: (1) Portland cement, silicate cement, and lime-based cement are incompatible with some waste materials, causing issues such as reduced strength. (2) Solidification products have poor durability [56]. For instance, high concentrations of organic matter in sludges can cause the degradation and decomposition of the solidification products, thereby accelerating the permeation of hazardous compositions [57].

Comparatively, the solidification/stabilization of hazardous pollutant using geopolymerization shows significant advantages in resource utilization, energy saving, emission reduction, and acid resistance. In 1993, the German company named B.P.S Engineering, which focused on nuclear waste treatment, was the first to use geopolymer materials for solidification/stabilization of nuclear waste. In 1999, Hermann et al. [58] demonstrated the successful small-scale treatment of radioactive solid waste using geopolymers. After that, increasingly related research has come out, from micro-mechanism to macro-properties. In this section, the application of alkali- and acid-activation geopolymers as immobilization materials and related mechanisms were reviewed.

2.1. Solidification/Stabilization of Heavy Metals

Heavy metals refer to metallic elements characterized by high density (≥4 g/cm3 or 5 times greater than water), which is toxic to humans even at low concentrations. Heavy metals can be found in the biosphere (rocks, soils, and water), originating from a variety of sources (mining, industrial effluents, sewage discharge, soil erosion, etc.) and many others. Due to the fact that heavy metals do not degrade, they will persist in the environment and accumulate in living organisms, and finally harm to human health [59].

Thus, there are many studies concerning the immobilization of different kinds of heavy metal ions using geopolymerization technology. Phair and Deventer [60] discovered that in an aqueous solution under alkaline conditions, Pb2+ and Cu2+ primarily occur as Pb(OH)2, Pb(OH)3−, Cu(OH)2, and Cu(OH)3−. However, the electrostatic repulsion prevents Pb(OH)3− and Cu(OH)3− from chemically bonding with the negatively charged geopolymer, resulting in Pb2+ and Cu2+ being primarily fixed in the geopolymer matrix through physical encapsulation. Wang et al. [61] used FA-based geopolymers to solidify different concentrations and types of heavy metal ions (1–3% Pb2+, Cd2+, Mn2+, and Cr3+). The results indicated that the solidification rate of heavy metal ions approaches 99.9%, with the solidification effectiveness following the order of Pb2+ > Cr3+ > Cd2+ > Mn2+. They pointed out that most ions are encapsulated in the geopolymer matrix, which has a dense structure that prevents leachate penetration, thereby inhibiting the leaching of heavy metals. Donatello et al. [62] used FA-based geopolymers to solidify HgCl2 (at a concentration of 5 g/kg), achieving a solidification ratio for Hg2+ of 98.8–99.6%. The precipitates of HgS, Hg2S, HgO, and HgSiO4 are physically encapsulated and solidified in the geopolymer matrix, while Cl− promotes the leaching of Hg2+. Jiang et al. [63] combined FA and red mud as precursors to prepare geopolymer for Pb2+ and Cu2+ immobilization. Through the chemical bonding of T (Si, Al)-O-M (Pb, Cu) and physical sealing (Figure 5), Pb2+ and Cu2+ can be solidified efficiently. Fernández-Pereira et al. [64] utilized aluminate geopolymers for Cd2+, Ni2+, or Pb2+ immobilization, showing that aluminate geopolymers are promising binders.

Figure 5.

Solidification mechanism of heavy metals using alkali-activated geopolymers [63].

In addition to ions, heavy metal-containing matters can also be immobilized by geopolymerization, mainly through physical encapsulation. Guo et al. [65] used FA-based geopolymers as solidifying agents to study the mechanisms of solidification for three lead-containing compounds (1–8% PbO, PbSO4, and PbS). The results indicated that for lead compounds that do not react with alkalis, solidification occurs primarily through physical encapsulation within the geopolymer. In contrast, for lead compounds that react with alkalis, they are incorporated into the geopolymer network during geopolymerization. In another study [66], they used FA-based geopolymers to solidify four chromium-containing compounds (Cr(NO3)3, Cr3O3, Cr, and CrO3). The results showed that both chemical bonding and physical encapsulation mechanisms are present in geopolymer solidification. In the case of Cr(NO3)3, chemical bonding is the primary mechanism for chromium solidification, whereas for Cr2O3, Cr, and CrO3, physical encapsulation serves as the predominant mechanism.

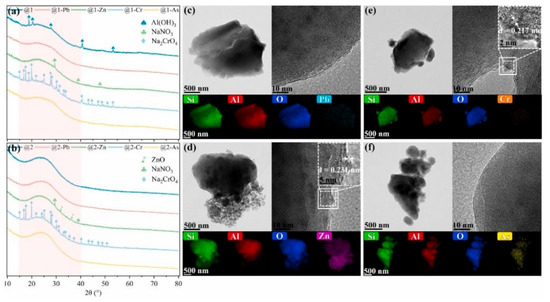

Notably, compared to cation, the solidification of anion using geopolymer appears to less efficient. Al-Mashqbeh et al. [67] attempted to solidify three anions (Cr2O72−, MnO4−, Fe(CN)63−) using MK-based geopolymers. As the concentration of anions increases from 0.2% to 1.5%, the leaching rate rises from 10% to 20%. The Si/Al ratio significantly influences the solidification effectiveness. This suggests that although geopolymers can encapsulate highly soluble anions, their fixation ability is somewhat constrained. Ji et al. [68] immobilized heavy metal cations (Cd2+, Pb2+, and Zn2+) and anions (AsO43− and Cr2O72−) using GGBFS-based geopolymer and found that the immobilization effect of cations are much higher than that of anions because the former has charge neutralization effect. Meanwhile, crystalline phase was formed after adding anions. Wang et al. [69] also compared the immobilization effect of heavy metal cations (Pb2+ and Zn2+) and anions (AsO43− and Cr2O72−) by geopolymer. The results show that heavy metal ions are distributed in geopolymer matrix evenly (Figure 6), and the incorporation of Pb2+, Zn2+, and AsO2− induced significant changes in the Si chemical environment. They also found that Pb2+ and AsO2− can be solidified in the form of Si−O−Pb/Al−O−Pb and Si−O−As covalent bonds, where Zn2+ mainly facilitates ion exchange with Na+, and Cr2O72− is partially immobilized through physical encapsulation, without being incorporated into the geopolymer structure.

Figure 6.

Solidification of heavy metal ions using alkali-activation geopolymers. (a,b) XRD patterns of geopolymer with different conditions; (c–f) TEM and EDX mapping of geopolymers with different conditions and selected area [69].

Although laboratory studies consistently report near-complete immobilization of heavy metals, successful field application requires consideration of additional practical factors. Cost is a key issue, as the alkali activators used for geopolymerization are generally more expensive than OPC, which may limit adoption in large-scale waste treatment unless optimized mix designs are developed. Social acceptance is another challenge, since substituting Portland cement in waste management could disrupt existing industry practices. Most importantly, the long-term stability of immobilized contaminants must be ensured. Future research should therefore include pilot-scale demonstrations and long-term leaching tests to validate the excellent laboratory performance under real environmental conditions.

2.2. Solidification/Stabilization of Radioactive Nuclear Waste

Apart from heavy metal ions, geopolymers were originally employed for the solidification of radioactive nuclear waste, which show better effect than cement [70,71]. However, in lab-scale research, isotopes are used instead of radioisotopes for safety considerations. It should be noted that laboratory studies typically use non-radioactive isotopes to replace radioactive isotopes for safety reasons, since their ionic radii, charge, and chemical behavior are essentially identical, except for radioactivity. Generally, 133Cs and 87Sr are the two most used isotopes for simulating 137Cs and 90Sr, respectively, in geopolymer immobilization. He et al. [72] prepared MK-based geopolymer by adding 133Cs(OH)2, followed by high-temperature calcination. The resulting ceramic exhibited a low leaching rate for 133Cs+ (2.51 × 10−4 g·m−2·d−1), indicating the significant potential of geopolymer ceramics for Cs solidification. Deng et al. [73] prepared FA-based geopolymer adding 2% 133CsNO3, and the γ-rays test results indicate that γ-ray irradiation has a minimal impact on the microstructure of the geopolymer but increases the porosity of the geopolymer and consequently the leaching rate of 133Cs+. Tavor et al. [74] assessed the immobilization performance of FA-based geopolymers for 133Cs+ solidification and found that 133Cs+ will increase the porosity of geopolymer. However, 133Cs+ will not destroy the geopolymers’ chemical structure and can be immobilized efficiently (Figure 7). Blackford et al. [75] employed transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and NMR testing to investigate the solidification of 5% 133Cs+ and 87Sr2+ in MK-based geopolymers. The study results indicated that 133Cs+ was incorporated into the amorphous phase of the geopolymer at the nanoscale, while 87Sr2+ preferentially formed SrCO3 rather than being incorporated into the geopolymer gel.

Figure 7.

Solidification and related mechanism of Cs+ using geopolymers [76].

With the increase in radioactive nuclear wastes, many other radionuclide ions have also been researched for solidification. Niu et al. [77] prepared phosphoric acid-activated MK-based geopolymers for radionuclide anion (K2SeO3, K2SeO4, KI, and KIO3) immobilization. Compared to alkali-activation geopolymer, acid-activation geopolymers can solidify anions through electrostatic attraction because they possess a positively charged surface (Figure 8), and the matrix structure of geopolymers remains unchanged, which shows much better effect in radionuclide anion immobilization [47]. Iqbal et al. [78] explored MK-based geopolymer for immobilizing co-hosting cationic and anionic radionuclides. They concluded that Cs+ was retained by charge balance with [AlO4]-, Eu3+ was likely solidified by complexation and sorption mechanisms, while MoO42- reacted during geopolymerization to form Na2MoO4·2H2O and then was likely retained through encapsulation. 60Co is also a kind of radioactive waste in the nuclear industry. Yu et al. [79] used geopolymer to immobilize Co2+. The results indicate that Mn-slag-based geopolymer shows better solidification effect on Co2+ than MK-based geopolymer. This is because the oxidation reaction of Co2+ during geopolymerization of Mn-slag effectively enhanced its immobilization.

Figure 8.

Solidification mechanism of anions using acid-activation geopolymers [77].

In addition to solutions, geopolymers can also applied to solidify/stabilize radioactive liquid organic waste, achieving a promising effect [80,81].

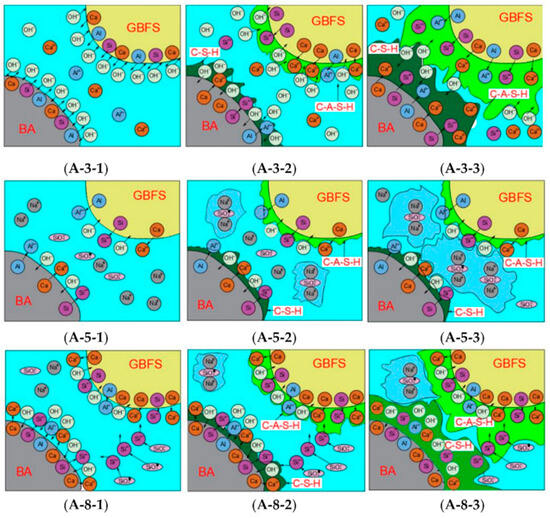

2.3. Solidification/Stabilization Mechanism

The mechanisms of solidification/stabilization during solidification can mainly be divided into two categories: (1) physical encapsulation and (2) chemical bonding [82]. These two actions occur simultaneously during geopolymerization. Generally, alkali-activation geopolymers can effectively reduce the migration rate of cations but are less effective for oxyanions. This is in contrary to acid-activation geopolymers.

Physical encapsulation generally occurs at the micrometer scale. In the alkali-based geopolymerization, precursors firstly dissolve Si and Al under the influence of an alkaline solution, forming oligomers such as [SiO(OH)3]−, [SiO2(OH)2]2−, [SiO3(OH)]3−, and [Al(OH)4], which then condense to form a binder and ultimately generate an amorphous 3D network structure (Figure 9). During this reaction, the coating effect of the oligomer gel can encapsulate ions (or related precipitates) within the matrix structure of the geopolymer [83]. Additionally, the ions can be effectively immobilized if the dimensions of the zeolite-like cage structure are compatible. At the same time, geopolymers can act as physical barriers, which prevent leaching hazardous components by inhibiting its contact with leaching media [84].

Figure 9.

Physical encapsulation of ions by geopolymer [85].

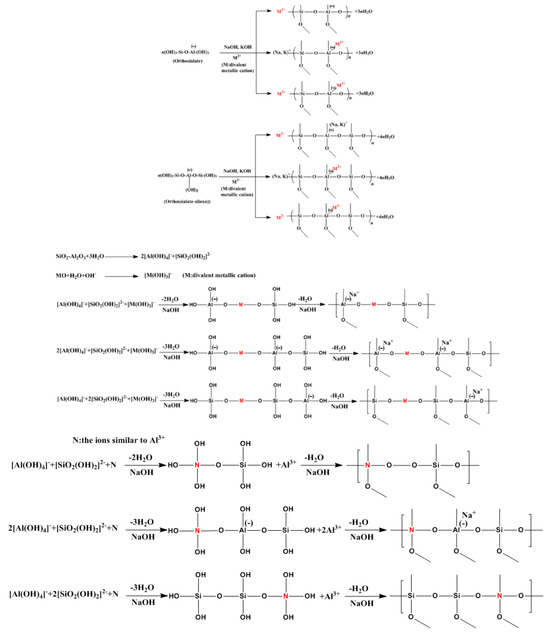

Compared to physical encapsulation, chemical bonding takes place at the nanometer scale, making a more contribution to immobilize. As shown in Figure 10, the cations can be solidified by charge balancing for [AlO4]− or formation of covalent bonding with Si-O− and Al-O− [56,86]. Recent studies indicate that the immobilization of ions occurs via isomorphous substitution [83]. Huang et al. [87] proposed that the positions of Al3+ in geopolymers can be substituted by similar ions, such as (Cr6+ (44 p.m.), Mn7+ (46 p.m.), and Fe3+ (55 p.m.). In addition, the solidification mechanism of geopolymers for ions also includes complexation and micro-precipitation [56].

Figure 10.

Chemical mechanisms of ions solidification in geopolymers [56,65,87]. The red M and N represents metals ion.

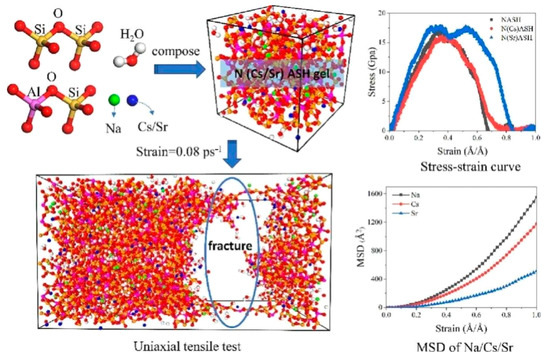

Recently, molecular dynamics study has been applied for insight into the immobilization mechanism. Wang et al. [88] reported that thanks to the large radius of Cs+ and high charge density of Sr2+, NASH gel can solidify these ions (Figure 11). The incorporation of Cs+ decreased the geopolymers’ strength and increased the fracture strain. In contrast, the inclusion of Sr ions increased the number of AlV, which thus increased the geopolymers’ strength and ductility. Wang et al. [89] investigated the effect of Si/Al ratios on the adsorption and diffusion of CsCl2 using molecular dynamics simulation. Density distribution demonstrated that Cs+ and Cl− will aggregate on the channel surface. Meanwhile, the adsorption capacity of geopolymer channel for these two ions enhanced, and diffusion capacity decreased as the decrease in Si/Al ratio based on the result of mean square displacement.

Figure 11.

Molecular dynamics study on structural characteristics of ions solidification in geopolymers [88].

Besides the solidification mechanisms based on the fundamental structure of geopolymers, there are also mechanisms based on the unreacted materials. El-Eswed et al. [90] demonstrated through Fourier transform infrared (FTIR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and SEM tests that, in addition to the aforementioned chemical bonding, the formation of hydroxides, carbonates, silicates, and aluminates is also a potential mechanism for immobilization. Under alkaline conditions, the precipitation of ions inhibits the reaction between ions and Si/Al ions. These results indicate that ions are not completely immobilized by silicates or aluminates alone; other components also influence the curing process.

The immobilization of hazardous ions is a hot topic in the application research of geopolymers, warranting in-depth understanding and attention, and should be extended to the solidification/stabilization studies of other hazardous matters, which has profound significance for environmental protection and management.

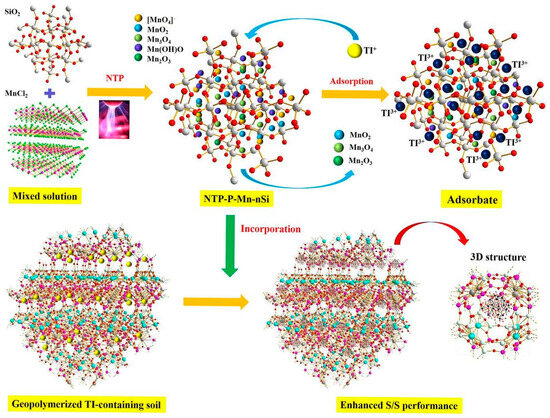

3. Adsorption of Ions Using Geopolymer

As stated in the Introduction section, a geopolymer possesses a 3D structure, which consists of tetrahedral silicate and aluminate units connected by covalent bonds. In this structure, negatively charged Al-O tetrahedra must be charge-balanced by alkali metal cations (Na+, or K+) [22]. Due to its weak bond, these cations can be exchanged by other cations, which show similar ion exchange mechanism of zeolites [91].

Generally, the smooth and flat surface of geopolymers contributes to increased mechanical properties. However, in certain cases, geopolymers can be prepared to have rough and irregular surfaces for a higher specific surface area and thus better adsorption capacity. In this way, cations can be adsorbed onto the porous structure and surfaces of the geopolymer, thereby reducing the transport of hazardous cations. Additionally, the high alkalinity of alkali-activation geopolymers can lead to an increase in the pH of the solution, allowing for the removal of some cations through precipitation [92]. In addition to adsorbing ions in the solution, recent studies have also explored the use of geopolymers for organic dye adsorption and CO2 capture. In this section, geopolymers as absorbent for hazardous ions, organic dye, CO2 gas, etc., absorption will be reviewed.

3.1. Adsorption of Heavy Metal Ions by Geopolymer

As mentioned in Section 2.1, heavy metals such as Cd, Pb, Cu, Zn, Cr, Ni, As, etc., are harmful to humans (Table 1) [93,94,95]. These metals originate from various industrial processes (e.g., electroplating wastewater) and other human activities, as well as from the dissolution of natural geological deposits. Exposure to environments contaminated with these heavy metals can lead to severe health issues in humans [96,97]. How to immobilize these metals, especially in solutions, raises an important issue. Existing studies have shown that geopolymers exhibit high removal efficiency and regenerative ability for the harmful ions.

Table 1.

Representative regulatory limits for heavy metal concentrations in leachates according to international environmental standards [93,94,95].

Normally, the geopolymers will be crushed to powder before they are used as absorbent. The results of Al-Harahsheh et al. [98] demonstrate that geopolymers can effectively adsorb Cu2+, with a maximum adsorption capacity of 152 mg/g. Cheng et al. [99] conducted adsorption experiments using MK-based geopolymers for Pb2+, Cu2+, Cr3+, and Cd2+. The results indicated that the adsorption reaction was endothermic, with heavy metal cations undergoing ion exchange with Na+ in the geopolymer. Meanwhile, the adsorption kinetics followed a pseudo-second-order model, and the adsorption isotherms adhered to the Langmuir model, with the order of adsorption capacities being Pb2+ > Cd2+ > Cu2+ > Cr3+. The geopolymer demonstrated the best adsorption performance for Pb, which may be related to the ionic radii of the ions. Arokiasamy et al. [100] prepared MK/silica fume-based geopolymer powder adsorbents for removal of Cu2+. They found that the replacement of 75% MK by silica fume can generate more reactive Si and Al binding sites for Cu2+ adsorption. Kumar et al. [101] synthesized ternary-blended geopolymer for Mn2+ removal, for which the uptake capacity from the model was found to be 17 mg/g at 35 °C, with working solutions at pH = 4 within 40 min of contact time. Ghafri et al. [102] developed a highly effective geopolymer sorbent for the removal of heavy metal ions from wastewater through Taguchi-TOPSIS hybrid method. They found that FA is beneficial to Pb2+ and Cd2+ removal while GGBFS is Ni2+ and Co2+. Kara et al. [103] utilized MK-based geopolymers to adsorb Zn2+ and Ni2+. The amounts of Zn2+ and Ni2+ adsorbed onto the geopolymer increased with contact time, reaching adsorption equilibrium at 40 and 50 min, respectively. As the dosage of the adsorbent increased, the adsorption capacity decreased, with maximum monolayer adsorption capacities for Zn2+ and Ni2+ of 1.14 × 10−3 and 7.26 × 10−4 mol/g, respectively.

However, in some application scenarios, powder shape absorbent is limited. Therefore, bulk-type geopolymers are also used for absorption. In order to increase absorption efficiency of these absorbents, creating foam in geopolymer bulk is a frequent method. Carvalheiras et al. [104] prepared geopolymer foam for Pb removal, where the maximum Pb removal reached 30.7 mg/g (Figure 12). Meanwhile, this monolith could be regenerated post-sorption without significantly affecting their performance. Novais et al. [105] also prepared porous geopolymer blocks for the adsorption of Pb2+. When the porosity increased from 52.0% to 78.4%, the adsorption efficiency improved by 68% with a faster adsorption rate. Prior to the adsorption reaction, the removal of OH− ions from the geopolymer significantly increased the single-pore porosity, thereby enhancing their adsorption capacity. Jiang et al. [106] adjusted the foaming agent (H2O2) and stabilizer to prepare geopolymer foam for Pb2+ and Cu2+ removal, where adsorption capacity of Pb2+ increased from 7.49 mg/g to 24.95 mg/g after foaming. Alshaaer et al. [107] utilized MK and wollastonite as precursors, Na2SiO4 as alkali activator, Al powder as foaming agent, and olive oil as foaming stabilizer to prepare geopolymer foam for the removal of heavy metal ions from water. The addition of wollastonite increased the mechanical properties and the adsorption rate of Cr, Co, Cu, Zn, Pd, and As in the as-prepared geopolymer.

Figure 12.

Geopolymer foams and their removal efficiency for heavy metals [104].

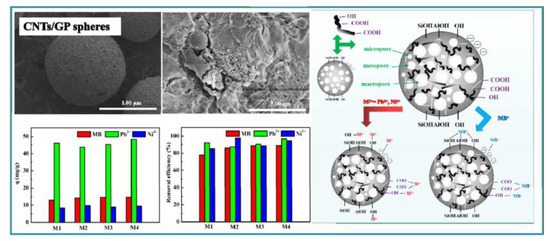

The design of absorbent with a spherical shape can further increase absorption efficiency. Tang et al. [108] utilized MK and an organic foaming agent to prepare spherical porous geopolymers for the adsorption of Cu2+, Ca2+, and Pb2+. This geopolymer demonstrated good adsorption performance for all three kinds of ions, with the adsorption order being Pb2+ > Cu2+ > Ca2+, and the adsorption process consisting of both chemical and physical adsorption components. Yan et al. [109] explored a spherical porous carbon nanotube-reinforced geopolymer with amorphous phases and BET surface area of 73.06 m2/g (Figure 13). The maximum absorption of Pb2+ and Ni2+ was 52.74 mg/g and 8.92 mg/g, respectively.

Figure 13.

Geopolymer foam sphere and its absorption mechanism of heavy metal ions [109].

As known to us, zeolite molecular sieves are a promising absorbent for its special structure. Meanwhile, geopolymer is an amorphous zeolite which show similar properties [110]. Recently, to increase the adsorption capacity of geopolymer, the addition of zeolites into geopolymer or the transformation of geopolymer to zeolite are studies. Andrejkovicová et al. [111] investigated the effects of clinoptilolite as a filler on the mechanical properties and heavy metal ions adsorption capacity of MK-based geopolymers. The addition of clinoptilolite contributes to an increase in strength, and the geopolymer with 25% zeolite shows the best adsorption performance for Pb2+, Cd2+, and Zn2+. The order of heavy metal adsorption by the geopolymer is Pb2+ > Cd2+ > Zn2+, while the highest adsorption for Cu2+ and Cr3+ occurs without the addition of zeolite. This order may be attributed to several factors, including the reactivity of ions, the free energy of hydration, the size of hydrated ions, changes in available coordination sites, and the pore size distribution on the geopolymer surface. However, El-Eswed et al. [112] used kaolin/zeolite-based geopolymers to adsorb heavy metal ions, obtaining different adsorption capacity results: Cu2+ > Cd2+ > Ni2+ > Zn2+ > Pb2+. Liu et al. [113] alkali activated nature clinoptilolite, where the partial clinoptilolite and impurity (montmorillonite, illite and albite) were transformed to geopolymer. This clinoptilolite-based zeolite-geopolymer foam can absorb heavy metal ions with the capacity order: Cr3+ > Pb2+ > Ni2+ > Cu2+ > Cd2+, which is related with Hard-Soft-Acid-Base principle and the speciation and radii of the hydrated metal ions.

In the case of transformation of geopolymer as zeolite, Li et al. [114] in situ synthetized zeolite microsphere based on MK-based geopolymer (Figure 14). The maximum adsorption capacities for Cu2+ were 698.14 and 523.84 mg/g, depending on the type of zeolite. They also used this kind of geopolymer-based zeolite for Pb2+ absorption with static removal of 584 mg/g and dynamic removal of 880 mg/g [115]. He et al. [116] obtained bulk analcime and zeolite P by a facile hydrothermal treatment and geopolymer precursor technique. In addition, these geopolymer-based zeolite shows outstanding adsorption performance for Cs+ with an adsorption efficiency of 93.3%.

Figure 14.

In situ transformation of geopolymer to zeolite for absorption of Cu2+ [114].

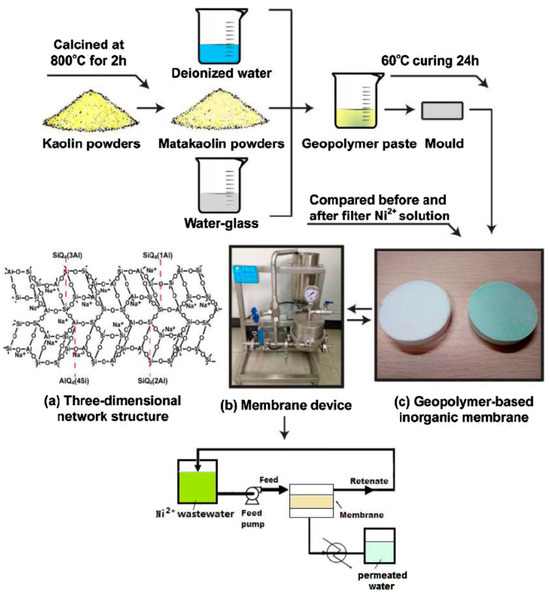

As a promising adsorbent, geopolymers are designed for real application in recent studies, like highly porous, inorganic self-supporting membranes, filters, and columns [117,118,119], which can reduce production costs compared to traditional ceramic materials and organic polymers. For instance, Ge et al. [120] developed a novel self-supporting inorganic membrane for wastewater treatment, which exhibited good adsorption performance for Ni2+ (Figure 15). Xu et al. [121] used MK-based geopolymers as filter membranes to treat green liquor, with the filtered effluent meeting China’s wastewater discharge standards. Amari et al. [122] prepared an innovative porous geopolymer membrane made from waste natural zeolite powder for Pb(II) removal. To obtain controlled porous architecture, polyvinyl acetate (PVA) (10, 20, and 30 wt.%) was added and then thermally treated at 300 °C. Adding 20 wt% PVA can achieve a permeation rate of 78.5 L/(m2·h) and an 87% absorption rate at an initial Pb2+ concentration of 50 ppm. De et al. [123] developed a porous, phosphate mine tailings-based geopolymer membrane, which can adsorb Cu2+ and humic acid from aqueous solutions.

Figure 15.

Process of preparing a geopolymer filter membrane [120].

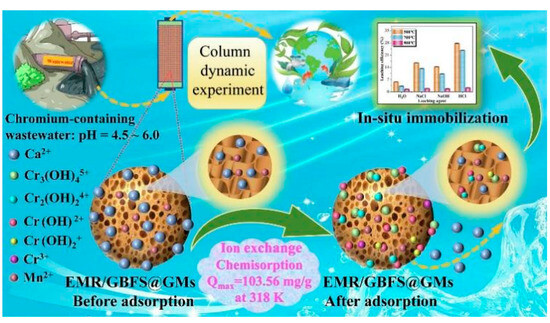

In addition, Wang et al. [124] applied a dispersion-suspension-solidification method to prepare solid wastes (electrolytic manganese residue/GGBFS) based geopolymer microspheres, aiming at resource utilization of electrolytic manganese residue and Cr-containing wastewater disposal. In the column experiments, the competitive absorption effects were in the following order: Mg2+ > Ca2+ > Na+ > K+ > Mn2+. Through the synergistic effects of ion exchange and chemisorption.

3.2. Adsorption of Radioactive Elements

Geopolymers have been studied for the adsorption of several radioactive isotopes, including Cs, Sr, Ra, Co, etc. Since the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan in 2011, the removal of radioactive isotopes from wastewater has become increasingly attractive [125]. Cesium exists in aqueous environments as Cs+, is highly soluble and stable, and has garnered attention due to the long half-life (30.2 years) of radioactive 137Cs [126]. Strontium, which primarily exists as Sr2+ in aquatic environments, has several radioactive isotopes, with 90Sr (half-life of 28.9 years) being the most significant [127]. All isotopes of radium (which typically exist as Ra2+ under low salinity conditions) are radioactive, with half-lives ranging from a few days to 1600 years [128]. Therefore, the removal of such radioactive ions is essential.

Compared to heavy metal ions, like Pb2+, Cu2+, Cd2+, Ni2+, and Zn2+, MK-based geopolymers demonstrate better selectivity for the adsorption of Cs+, and their adsorption efficiency is not affected by NaCl concentrations in comparison with the aforementioned heavy metals. López et al. [129] prepared a porous geopolymer using kaolinite and rice husk ash to adsorb Cs+, finding that the removal rate of Cs+ increased with the increasing silicon content in the geopolymer. Lee et al. [130] used mesoporous geopolymers to remove Cs+ from solutions. The removal rate of Cs+ significantly increases from 85% to 96% with the presence of nano-crystalline zeolites and can be enhanced by longer contact times and increased solution pH, while it decreases with lower initial Cs+ concentrations. The adsorption kinetics fit both the pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models, indicating that the adsorption process of Cs+ involves both physical and chemical adsorption. Zheng et al. [131] concluded that the NaNO3 concentration in solution will affect the adsorption performance of geopolymer.

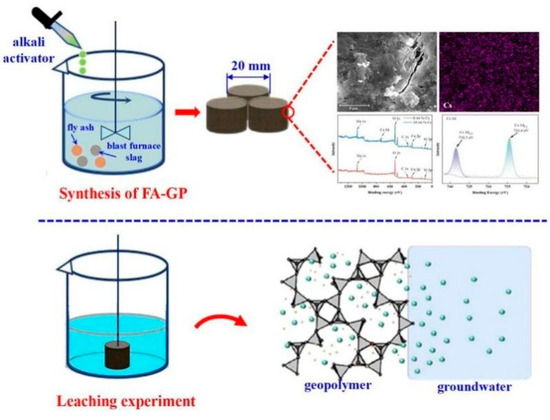

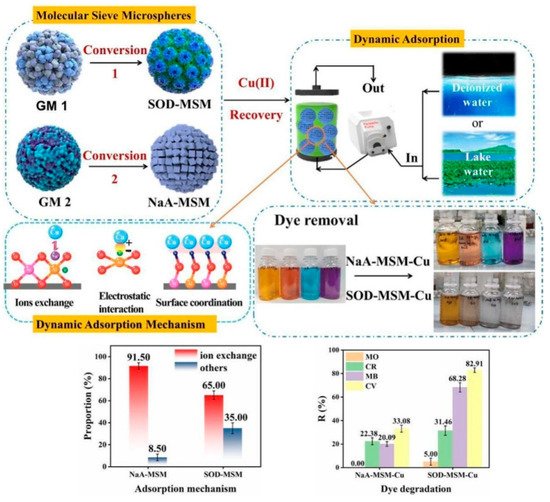

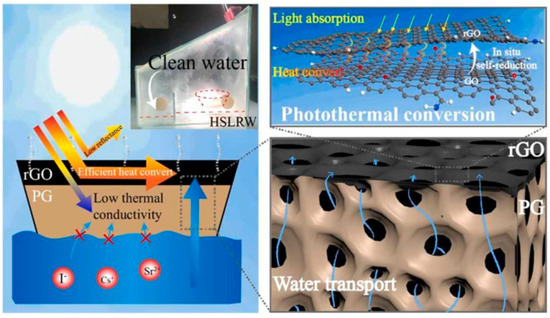

Wang et al. [132] prepared NaA zeolite microspheres using MK-based geopolymers (Figure 16). The NaA zeolite microspheres exhibited excellent removal efficiency for Sr2+. These microspheres have high Sr removal efficiency, excellent regeneration, and recyclability performance. Deng et al. [133] applied an in situ self-reduction in graphene oxide method by adding geopolymer for treatment of the simulated high salt liquid radioactive waste (Figure 17). The removal ratios of radioactive I−, Cs+, and Sr2+ in the simulated wastewater reached 99.62%, 99.71%, and 99.99%, respectively.

Figure 16.

Process of geopolymer sphere for filler in column filter [124].

Figure 17.

Absorption mechanism of graphene oxide-modified porous geopolymer [133].

For other radioactive ions, Panda et al. [134] prepared a pyrophyllite mine waste-based geopolymer using waste to adsorb Co2+. This geopolymer exhibited a strong adsorption capacity for Co2+ in water, primarily through chemical adsorption. Kara et al. [135] demonstrated that MK-based geopolymers possess good adsorption property for Mn2+ and Co2+, with adsorption occurring on the homogeneous surface of the MK-based geopolymers. Li et al. [136] used MK-based geopolymer microspheres prepared by vacuum infusion and dispersion-pelletizing-solidification methods for the efficient adsorption of ReO4−, in which ReO4− is removed by electrostatic and coordination synergism with quaternary ammonium salts after ion exchange.

3.3. Adsorption of Organic Dyes

Dye pollution mainly comes from industries such as textile printing and dyeing, leather manufacturing, papermaking, food processing, and cosmetics production. The dyes are carcinogenic and poisonous, which requires decontamination [137]. Absorption is an effective way to remove dye, and as stated before, geopolymers can also be used to remove different kinds of ionic dyes, such as methylene blue and crystal violet, through ion exchange reactions.

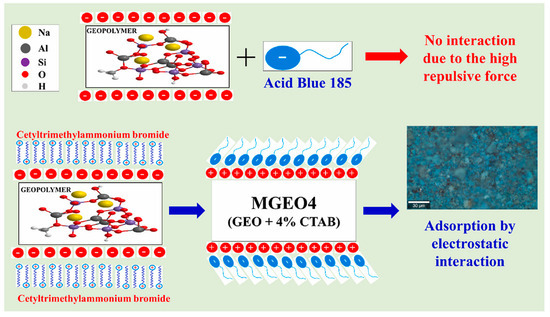

Methylene blue (MB) is widely used as a model cationic dye in adsorption research and is chosen here for several practical reasons: it is strongly cationic and water-soluble, has a well-defined chemical structure, and can be accurately quantified by UV–Vis spectroscopy. MB is commonly employed as a surrogate for cationic contaminants present in textile effluents, so MB adsorption tests provide a convenient benchmark to assess ion-exchange capacity, surface adsorption, and pore accessibility of geopolymer adsorbents. It should be noted, however, that MB mainly represents cationic dye behavior; adsorption of anionic dyes or complex real wastewaters may follow different mechanisms and require additional testing [138,139,140]. Novais et al. [141] fabricated a FA-based geopolymer block for the adsorption of MB, observing a maximum adsorption of 20.5 mg/g, with the removal efficiency controllable by adjusting pore volume and connectivity (Figure 18). The adsorbent can be used in packed beds, regenerated, and reused (at least 5 times). Ozkan et al. [142] prepared a porous geopolymer by adding Zn and Al, achieving an adsorption efficiency for MB as high as 97.4% in 50 ppm solution. En-naji et al. [143] explored acid-activation geopolymers for MB removal. The geopolymer prepared by 75% MK/25% calcined clay had the highest efficiency in removing MB with a rate of 98%. Eshghabadi et al. [144] fabricated MK-based geopolymer for MB absorption. Pseudo-second-order kinetic with an equilibrium time of 120 min and Freundlich isotherm models fits the adsorption behavior, with the highest MB adsorption >90%.

Figure 18.

Photos of different proportions of polymers for removing methyl blue. (a–d) Different samples [141].

Crystal violet dye (CVD) is another normally used dye in removal study. Barbosa et al. [143,144,145] prepared geopolymers from kaolinite, rice husk ash, and soybean oil for the adsorption of CVD, achieving a relatively high maximum capacity of 276.9 mg/g. Marubini et al. [146] prepared vermiculite-based geopolymer for CVD removal, where the absorption kinetic and isotherm models were suitable in the pseudo-second order and Temkin models. This adsorption process was endothermic and spontaneous through the calculation of ΔH and ΔS.

Other cationic dyes are also attracting attentions gradually. Tochetto et al. [147] pretreated geopolymer by sulfuric acid and calcination for improved adsorption of the direct red dye 28. The Elovich model describes the kinetics, while the Sips model represents the isotherms. El-Apasery et al. [148] used two kinds of geopolymer to remove reactive yellow 145. Taquieteu et al. [149] synthesized geopolymer–lignin composites for methyl orange absorption and found that these composites are eco-adsorbents for the removal of azo dyes in a continuous adsorption system.

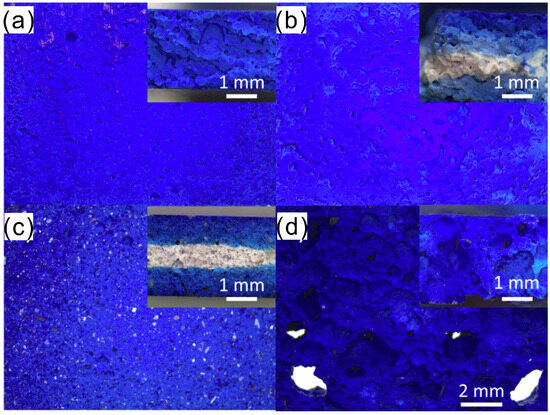

Similarly to the case of heavy metal ions, the adsorption of anionic dye for geopolymer appears to less effective than cationic dye [150]. Açışlı et al. [151] modified geopolymer using CTAB for anionic acid blue 185 adsorption (Figure 19). This modification increased removal efficiency from 0.29% up to 79.36% in 40 min. Purbasari et al. [152] compared the adsorption of cationic (methyl violet) and anionic (eriochrome black T) dyes on porous FA-based geopolymer. Both adsorption of methyl violet and eriochrome black T followed pseudo-second-order kinetics model and Langmuir isotherm model, with maximum adsorption capacity of 49.26 and 45.45 mg/g, respectively.

Figure 19.

Absorption mechanism of anionic dye for geopolymers [151].

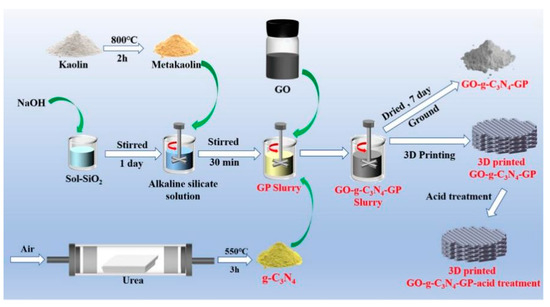

Recently, 3D printing technology was used to strengthen the absorption efficiency of dyes [153]. Liu et al. [154] combined geopolymer, g-C3N4, and different contents of GO for preparing geopolymer composites. Through 3D printing, a geopolymer-based scaffold was manufactured for MB removal (Figure 20). They also found that the introduction of Fe3+ into this composite could further improve the MB removal efficiency.

Figure 20.

Preparation of 3D printing GO-g-C3N4-geopolymer composites [154].

Although geopolymers have certain advantages in removing organic dyes (such as strong regeneration ability), their reported adsorption capacities are currently lower than those of commercially available activated carbon or other experimental adsorbents, meaning that it requires further optimization research.

3.4. Adsorption of CO2

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is an indispensable gas on earth. However, too much CO2 emission in the air leads to the greenhouse effect, which will increase the temperature around the world and finally cause a global disaster. The capture and storage of CO2 has become a hot topic recently. In fact, zeolites, with porous structure, have been used to absorb CO2 because zeolites exhibit acidity due to the presence of Lewis and Brønsted acid sites [155]. As an amorphous zeolite, geopolymers have also been attempted to be used as adsorbents for CO2 capture. Freire et al. [156] invented a kind of MK/phosphate sludge-based geopolymer, where the existence of Fe2O3 in geopolymer enhanced the chemical interaction with CO2, forming iron bicarbonate, monodentate carbonate, and bidentate carbonate. Hossain et al. [157] fabricated a lightweight scaffold via extrusion-based 3D printing for CO2 capture. By hydrothermally treated, 3D printed geopolymer showed a CO2 adsorption effect of 1.22 mmol/g, which higher than conventionally casted geopolymer. Minelli et al. [158] prepared porous kaolinite-based geopolymer blocks and investigated the effects of the H2O/K2O ratio and gas pressure on CO2 adsorption. The results showed that the geopolymer with an H2O/K2O ratio of 13 exhibited the best CO2 adsorption (0.6 mmol/g), as it had finer pores and a larger specific surface area, providing greater contact points for gas adsorption. Additionally, the adsorption capacity of the geopolymer for CO2 was significantly greater than that for other lighter gases, with the order of adsorption capacity being CO2 > CH4 > N2.

Although geopolymer shows comparable CO2 adsorption to other solid adsorbents but lower than most well-performing zeolites or MOFs. To improve the CO2 adsorption performance of the geopolymer, Minelli et al. [159] also added zeolite during the preparation of geopolymer to create zeolite/geopolymer blocks. The geopolymer composite prepared with 27% Na13X zeolite showed the best CO2 adsorption performance at 0.1 bar, reaching 1.1 mmol/g. The study found that the composite of geopolymer and zeolite exhibited a synergistic effect on CO2 adsorption, effectively combining the functional micropores of zeolite with the mesopores of the geopolymer matrix, thereby reinforcing the zeolite phase. Han et al. [160] synthesized zeolite X in foam geopolymer as a CO2 adsorbent and the results showed that the maximum CO2 absorbance reached 7.91 mmol/g. Wang et al. [161] prepared a geopolymer/zeolite composite from municipal solid waste incineration fly ash (MSWIFA) for CO2 adsorption. The results indicated that the as-obtained composite possessed a CO2 uptake for 2.06 mmol/g, due to the new formed analcime and the high specific surface area and porosity. In the study of Wu et al. [162], they pointed out that geopolymer/zeolite composites exhibit a CO2 adsorption capacity of 4.18 mmol/g by the zwitterion reaction mechanism by forming carbamate.

In addition, Papa et al. [163] developed a new geopolymer/ hydrotalcite composite with suitable mechanical and thermal properties for CO2 adsorption. However, due to the limited capacity of the geopolymer matrix, especially under moderate temperature conditions, the CO2 absorption capacity of the composite primarily depends on the hydrotalcite content. Chen et al. [164] added activated carbon in geopolymer (Figure 21), which can improve the CO2 adsorption by 2.25 times. The intercalation of –C=O, –OK, and –COOK functional groups on the activated carbon surface during geopolymerization favored the CO2 adsorption. In addition, the incorporation of carbonic anhydrases, a kind of metalloenzyme that can catalyze the hydration of CO2, into geopolymer microspheres can enhance their capacity for CO2 capture with excellent reproducibility [165,166].

Figure 21.

Activated carbon-geopolymer composites for CO2 absorption [164].

3.5. Adsorption of Other Matters

Rare earth elements (REEs) are critical resources for many high-tech applications, and their demand is increasing [167]. Rare earth elements typically exist in relatively low concentrations in minerals, necessitating effective extraction technologies. However, some REEs are also harmful to human health when they enter body in high concentrations. Fiket et al. [168] reported a preliminary study where they used a fly ash-based geopolymer to adsorb Ce, La, Nd, Pm, Dy, Er, Eu, Gd, Ho, Lu, Sc, Sm, Tb, Tm, Y, and Yb from multi-element solutions. Their experimental results showed that all the studied rare earth elements were very effectively adsorbed at 120 min. Reis et al. [169] explored the rice husk/MK-based geopolymer for absorbing Ce3+, La3+, Pr3+, Sm3+, and Nd3+ from phosphogypsum leachate, which recovery were 86.33%, 79.64%, 53.33%, 71.25%, and 95.03%, respectively.

Ammonium (NH4+) is a common nitrogen-containing species in wastewater, which will destroy aquatic ecosystems by eutrophication, which required removal before emitting wastewater [170]. Luukkonen et al. [171] used MK-based geopolymers to adsorb NH4+ from solution, achieving an adsorption capacity of 21.07 mg/g, which is higher than that of typical natural zeolites. They also demonstrated that the adsorption mechanism is ion exchange, and the material can be regenerated using 0.2 M NaCl and 0.1 M NaOH solutions. Furthermore, the adsorbent can effectively treat landfill leachate on-site at low temperatures. In another study [172], they optimized the NH4+ adsorption capacity by using a high content of alkali activator, a small amount of MK, with the maximum adsorption capacity increasing from 21.07 to 31.70 mg/g. Clausi et al. [173] replaced MK by two types of sludge to prepare geopolymer composites. This composite can absorb NH4+ efficiently (66.6% of NH4+ removal and 18 mg/g adsorption capacity) after optimization. Savoir et al. [174] treated MK-based geopolymer using HCl solution to enhance its ability to adsorb NH4+. In acidic environments and at low ionic strength, NH4+ will be absorbed more easily, while the presence of co-existing species (bicarbonate, humic acid, and sulfate) hinders its adsorption.

In the research of Naghsh and Shams [175], the MK-based geopolymer was used for the removal of Mg2+ and Ca2+ from water. Their materials were comparable to commercial water softening agents (such as 4A zeolite) in both synthesis and actual groundwater adsorption experiments.

Besides the cation, many oxyanions were also studied. Sulfate (SO42−) is a commonly and naturally occurring anion that, although non-toxic, can lead to the salinization of water bodies. Therefore, the removal of sulfates is necessary in some large-scale industrial processes, such as mining (acid mine drainage) and seawater desalination plants. Runtti et al. [176] synthesized modified slag-based geopolymer by ion exchange, replacing Na+ with Ba2+. The resulting material was used to remove sulfate (SO42−~1000 mg/L) from synthetic wastewater and mine wastewater (SO42−~900 mg/L). The adsorption capacity was approximately 119 mg/g, and it could achieve very low sulfate concentrations (<2 mg/L). Their study suggested that the removal mechanism was surface complexation or the formation of BaSO4 precipitation. Zhang et al. [177] demonstrated through molecular dynamics simulations that cations such as Na+ or Mg2+ adsorbed onto the hydroxyl groups on the surface of N-A-S-H gel can attract SO42− ions. In addition, Zhang et al. [178] explored the sulfamethoxazole removal using copper slag-based geopolymer.

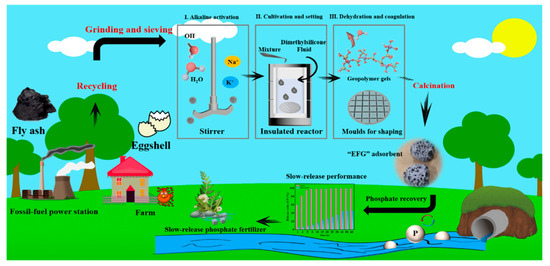

Phosphate (PO43−) is also a pollutant that will cause eutrophication in water. Sun et al. used eggshells and FA to prepare geopolymer (Figure 22) [179]. Eggshells after high-temperature pyrolysis can provide active sites (CaO) and porous structure (CO2) for phosphate adsorption. When eggshell: FA ratio was 40%, the phosphate adsorption performance reached maximum of 49.92 mg P/g. The adsorption process was well described by the pseudo-second-order model and the Langmuir model. Savoi et al. [180] found that loading La in geopolymer can significantly increase the PO43− removal through inner-sphere complexation and adsorption. Karmil et al. [181] produced a low-cost porous geopolymer using reverse osmosis (RO) reject brine as mixing water for PO43− removal.

Figure 22.

Eggshell–fly ash-based geopolymer for phosphate absorption [179].

4. Resource Utilization of Solid Wastes by Geopolymerization

In the process of human activity, a significant amount of solid waste is generated. Such waste includes wastewater treatment sludge, various tailings, fly ash, slag, etc. Some solid wastes may not be toxic, but their accumulation occupies large areas of land and cause water and air pollution. Some solid wastes contain substantial amounts of hazardous composites like heavy metals or radioactive species. If not properly treated, these species can cause significant damage to geological and ecological environments. As an environmentally friendly technology, geopolymerization thus has also been used to treat solid wastes, for not only resource utilization but also stabilization of hazardous composites. This section reviews the current research status on the non-hazardous and hazardous solid wastes treated with geopolymerization technology.

4.1. Utilization of Common Solid Wastes

4.1.1. Mine Tailings

Mining and mineral processing tailings are among the most scrutinized industrial by-products due to their large volume. Tailings are one of the largest waste materials globally, and they are typically stored in dammed ponds along with process water or stacked nearby as thickened slurries [182]. It is estimated that approximately 2.025 billion tons of solid waste are produced globally each year, of which 500 to 700 million tons are tailings. Furthermore, with the increasing utilization of low-grade ores, this figure is bound to rise in the future [183]. Therefore, finding efficient ways to utilize tailings has become an urgent issue for achieving a circular economy and minimizing waste. Research has shown that many tailings contain reactive aluminosilicates, making them suitable raw materials for geopolymer production. Therefore, directly utilizing such tailings to produce geopolymers can effectively utilize solid waste and provide significant guidance for practical production applications.

(1) Red mud. Red mud is the red solid waste left after extracting Al2O3 from bauxite ore, characterized by large production, high alkalinity, fine particle size, large specific surface area, and strong adsorption capacity. The combination of very fine particle size, plate-like mineral phases, and high soluble-alkali content (Na+/OH−) stabilizes colloidal suspensions and increases water demand. This leads to difficulties in dewatering, pumping, and mixing, and can negatively affect geopolymerization by increasing porosity and decreasing strength; it also raises environmental concerns related to alkaline leachate.

Typically, 1.5–2.5 tonnes of red mud are generated per tonne of alumina produced, depending on ore quality and process efficiency [184]. In 2023, global alumina production was approximately 141.8 Mt, generating an estimated 177 Mt of red mud, with cumulative global stockpiles exceeding 4 billion tonnes [185]. However, the high dispersion characteristics of red mud particles pose challenges for recovery and potential secondary pollution. How to consume such amounts of solid waste attracts attention.

Disposal methods [186,187,188] include (i) wet storage in tailings ponds with engineered liners and drainage systems, (ii) dry stacking after mechanical dewatering to minimize land footprint, (iii) neutralization with acidic agents followed by soil cover and revegetation for ecological rehabilitation, and (iv) resource utilization such as incorporation into geopolymer binders, cement, ceramics, or recovery of Fe, Ti, and REEs.

Direct utilization is one of the best options for treating red mud, and there have been numerous reports on using red mud as a precursor for geopolymers. Yang et al. [189] optimized activation, activator, and water-to-binder ratio condition to prepare RM-based geopolymer with a maximum 28 d compressive strength of 181.6 kPa. Ascensao et al. [190] prepared porous geopolymers using red mud, which exhibited high buffering capacity and long-lasting performance, making them suitable as pH buffering materials. Hertel et al. [191] prepared porous geopolymers from red mud for the adsorption of MB, and the synthesized porous blocks demonstrated high adsorption capacity (17 mg/g at an initial concentration of 75 mg/L). The higher the porosity of the geopolymer blocks, the higher the pH value and porosity.

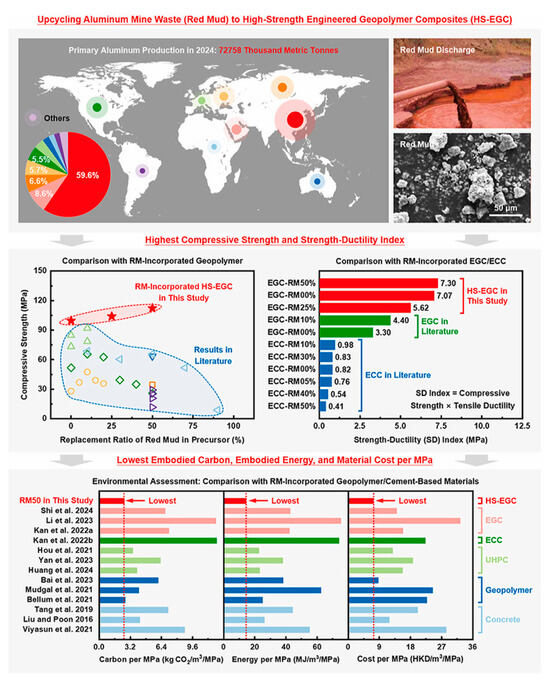

Due to the low strength for geopolymer based on solely RM, the addition of higher-reactivity precursors has also been studied. Liu et al. [192] compared five kinds of calcined RM as geopolymer precursors. The silica dissolved from RM favored the strength development of RM/FA-based geopolymer. In contrast, Hao et al. [193] increased the RM’s reactivity through mechanical activation instead thermal activation. They found that crystal structure of mineral phase in RM is destroyed by mechanical grinding, resulting in a large increase in strength and resistivity. Xu et al. [194] used RM to produce high-strength high-ductility engineered geopolymer composites. After optimization, the geopolymers’ compressive strength is over 100 MPa, and a tensile strain capacity is over 5%, even though the utilization rate of RM is as high as 50%, which is better than in many other studies (Figure 23).

Figure 23.

Red mud-based engineered geopolymer composites [194].

(2) Coal gangue. Coal gangue is a solid waste generated during coal mining and beneficiation, accounting for approximately 10–15% of the total solid waste in China. It is estimated that the accumulation of coal gangue in China has exceeded 5 billion tons, with an annual increase of 152 million tons, which also required utilization.

The main components of coal gangue are kaolinite, illite, and quartz; calcining CG can produce a large number of amorphous aluminosilicates, making it a very promising precursor for geopolymer preparation. Cheng et al. [195] utilized coal gangue as a raw material for geopolymers and investigated the effects of Na2SiO3 modulus and L/S ratio on their mechanical properties and microstructure, achieving a maximum strength of 70 MPa at 28 days, providing experimental and theoretical support for the development of CG-based binders. Geng et al. [196] compared the effects of thermally activated and mechanically activated CG-RM as precursors on the properties of geopolymers. The study indicates that mechanically activated CG exhibits better geopolymer reactivity than thermally activated one. Wang et al. [197,198] investigated the effect of alkali activators and GGBFS on the mechanical properties of CG-based geopolymer. The compressive strength can reach 24.75 MPa after adjusting alkali activators and 54.59 MPa after adding GGBFS. Zhao et al. [199] concluded that the amorphous SiO2 and Al2O3 phases are critical factors for the geopolymerization of CG, and that the geopolymer, mainly N-A-S-H gels, can fill the existing cavities and increase strength.

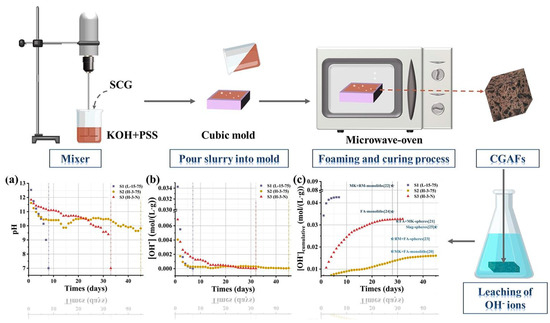

To increase the utilization efficiency and high-value utilization of CG, many efforts have been posed. Zhao et al. [200] used CG as both a binder and an aggregate for preparing ultra-high-performance geopolymer concrete (UHPGC) with a 28 d compressive strength of 143.1 MPa. Bakil et al. [201] improved the specific surface area of CG by grinding, which can provide more reactive sites for geopolymerization and thus improved strength and microstructure of CG-based geopolymer. Zeng et al. [202] applied machine learning method to predict the mechanical properties of CG-based geopolymers and offers guidance for mix design tailored to CG from different sources. Li et al. [203] fabricated porous CG-based geopolymer for pH regulator (Figure 24). All these efforts provide more ways to use CG-based geopolymer.

Figure 24.

Coal gangue-based geopolymer for pH regulator [203].

(3) Other tailings. In addition to red mud and coal gangue, a wide variety of tailings from metallic and non-metallic mineral processing can serve as potential geopolymer precursors. The most significant include iron ore tailings (~500 Mt/year in China), copper tailings (~200–300 Mt/year globally), lead–zinc tailings (~100 Mt/year in China), and smaller volumes of nickel, molybdenum, and tungsten tailings [204,205,206]. Non-metallic tailings such as quartz, fluorite, and phosphate also contribute to the global solid waste stream. However, these tailings are geographically scattered and vary greatly in chemical composition and reactivity. In many cases, the resulting geopolymers exhibit lower compressive strength than those derived from fly ash or slag. For this reason, this section provides only a general overview of these materials, emphasizing their resource utilization potential and environmental significance.

Many other mineral processing tailings, like metallic tailing have also been studied as precursors for geopolymers. Duan et al. [207] synthesized a porous alkali activation geopolymer using iron tailings, fly ash, and H2O2 (total porosity: 74.6%) for the removal of Cu2+. Due to the clear pore size distribution and high total porosity, this geopolymer achieved a Cu2+ removal rate of 90.7%. Carvalho et al. [208] prepared acid-activated iron tailing-based geopolymer with maximum compressive strength of only ~22.5 MPa. Jiao et al. [209] used tungsten tailings and MK to synthesize geopolymers and found that curing in a steam autoclave can effectively enhance the compressive strength (7-day compressive strengths reaching 86 MPa) of geopolymers and inhibit efflorescence behavior in a shorter time. Karrech et al. [210] used lithium ore residue as a raw material (containing spodumene, lepidolite, quartz, kaolinite, and other minerals) to produce geopolymers with relatively low strength; after calcination, by adding varying proportions of kaolinite, MK, steel slag, and fly ash, geopolymer composites were created, achieving a maximum 28-day strength close to 100 MPa. Zhang et al. [86] firstly used ion-adsorption rare earth mine tailings to prepare geopolymer for Pb2+ and Cd2+ immobilization. Clay minerals, like kaolinite, play an important role in geopolymerization and provide strength and absorption capacity for geopolymer.

Other non-metallic tailings are also promising geopolymer precursors. Wang et al. [211] used garnet tailings as raw materials, adding a certain amount of MK to produce high-strength geopolymers. Kızıltepe et al. [212] developed one-part geopolymer by co-alkali fusion with boron mine tailing, where new crystalline phases (merwinite, monticellite, sodium peroxide, and magnesium oxide) appeared. The highest compressive strength reached 24.2 MPa, and the highest flexural strength reached 4.3 MPa. Qiu et al. [213] utilized fluorite tailings for one-part geopolymer preparation. However, due to the low reactivity, the compressive strength was only 7.2 MPa, even when the calcination temperature reached 1000 °C. Haddaji et al. [214] reinforced phosphate mine tailing/MK-based geopolymer with fibers. The addition of 1% of polypropylene and glass fibers increased the flexural strength by 278% and 26%, respectively. Wang et al. [215] prepared sulfur tailings/GGBFS-based geopolymer with a compressive strength of 32.2 MPa by using CaO-Na2SiO3 composite as activator.

4.1.2. Construction and Demolition Wastes

Approximately 800, 700, and 1800 million tons of CDW are produced annually in European Union countries, the United States, and China, respectively [216]. Although CDW does not emit hazardous elements, the burial or are dumped in the open air caused serious environmental pollution and the consumption of land resources [217,218]. In recent years, recycling these wastes after crushing and sorting as aggregates or active powder for preparing recycled geopolymer (concrete) is a hotspot. Recycled powder (RP) has small particle size; this means it can easily become suspended in air, thereby functioning as a pollutant that poses a health hazard. Considering that RP is mainly composed of silica (SiO2) and alumina (Al2O3), it can be used as geopolymer precursor.

The geopolymer obtained from alkali-activation of sole RP showed low mechanical properties [219,220,221]. Therefore, pretreatment techniques such as grinding [221,222], calcination [223,224], acidification [225,226], and carbonation [227,228] have been applied for enhancing the properties of RP.

Carbonation can reduce the porosity and water absorptivity of RP owing to the reaction between hydration products and CO2 [227,229]. Lu et al. [227] demonstrated that RP subjected to carbonation increased compressive strength of geopolymer by 21.9% and 12.1% and decreased >25% porosity. Calcination can not only condense the RP microstructure but also decompose its hydration products to increase reactivity [216,228]. Sui et al. [230] pre-treated RP by calcinating at different temperatures. They reported that 700 °C was the suitable calcination temperature compared to other temperatures. Zhang et al. [231] investigated the effects of the replacement ratio, pretreatment methods (carbonization and calcination), and alkali modulus on the properties and microstructure of recycled FA/GGBFS-based geopolymer. The results show that calcination at 600 °C exhibited better effects (mechanical properties and lower critical pore size) than carbonization pretreatment, due to the active clay minerals.

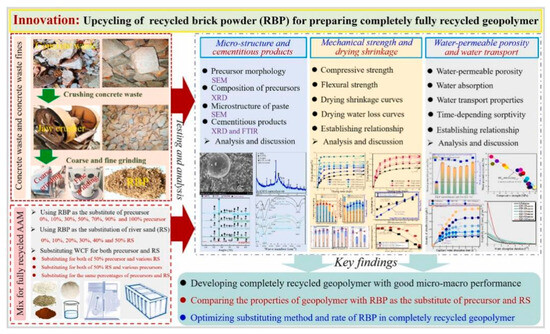

Mechanical activation can decrease the particle size and SSA of RP, which can also increase RP’s reactivity. Xu et al. [232] synergistically activated RP by using mechanical-thermal methods. When grinding time was 10 min and calcination temperature was 750 °C, the 3-day, 7-day, and 28-day compressive strength increased 77.91%, 109.88%, and 108.18%, respectively. Ma et al. used recycled brick powder and fine aggregates to prepare geopolymer mortar. In an appropriate replacement ratio, RBP as fine aggregate can refine the microstructure and enhance the mechanical strength and permeability resistance of geopolymer, where the compressive strength can reach 78.1 MPa (Figure 25) [233].

Figure 25.

Upcycling of recycled brick powder for geopolymer preparation [233].

In addition, the incorporation of GGBFS, FA, or any other high-reactivity raw materials can also increase the mechanical properties and durability of geopolymer derived from RP [234,235,236].

4.1.3. Engineering Muck

Engineering muck (EM) is also a kind of construction solid wastes, which is generated by excavating rock and soil underground construction activities [237]. In different places and depths, the mineral composition of EM will be different. The improper dispose of these solid wastes may cause severe geological disaster [238]. Considering the abundant aluminosilicate minerals in EM, geopolymerization is no doubt a suitable technology to treat these solid wastes.

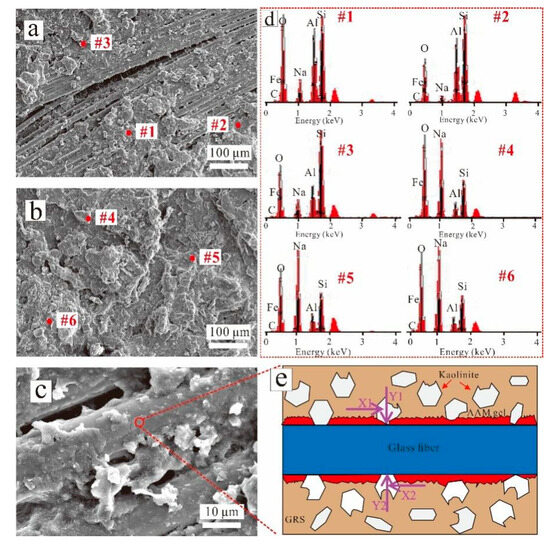

Compared to other places, the EM in subtropical/tropical areas contains more clay minerals (clay minerals like kaolinite, halloysite, and illite) due to the fact that rocks will go through strongly weathering in these places [239]. This endows EM with a high geopolymerization reactivity. Yuan et al. [240,241] used alkali solution to reinforce EM (mainly granite residual soil) to improve its soil strength. Studies show that under the action of alkali, kaolinite in EM underwent geopolymerization. Through processes of dissolution–rearrangement–polycondensation, a small amount of geopolymer gel is formed, which bonds mineral particles and fills the pores between them, thereby reducing the porosity of the soil and enhancing its static mechanical properties (Figure 26). The addition of fibers further strengthens the connections among mineral particles. Through the synergistic interaction between unreacted kaolinite and glass fibers, the dynamic performance of the improved EM is significantly enhanced. When a small amount (2%) of cement is added, the mechanical properties of the treated EM are further improved. This is because highly reactive minerals provide an important source of Al for cement hydration, leading to the formation of calcium aluminosilicate hydrate gels with higher strength. These gels couple with geopolymer, forming a denser structure. In the other studies [242,243,244], they took EM as precursors for preparing geopolymer and optimized their compressive strength by adjust the alkali activator, calcination temperatures, and particle sizes of raw materials. Under appropriate thermal treatment (850 °C), kaolinite in EM converts into MK with high reactivity, which can be dissolves in alkaline solution extensively, generating a large number of aluminosilicate monomers that further polymerize into geopolymer. Quartz and feldspar act as filler particles. The resulting geopolymer can reach a compressive strength of up to 58 MPa. The content of soluble silica and the concentration of alkali affect both the dissolution rate and amount of clay minerals, thereby controlling the microstructure and performance development of the geopolymer.

Figure 26.

(a–c) SEM images of geopolymer-reinforced engineering muck, (d) EDX result of selected area and (e) Schematic diagram of fiber-reinforced engineering muck [241].

Besides granite residual soil, other types of EMs also need to be recycled. Dassekpo et al. [245] calcined weathered granite-type EM at 650 °C, and the 7-day strength of the resulting geopolymer increased by nearly twofold compared to uncalcined EM. They [246] also explored loess-type EM for geopolymer preparation. However, FA has to be added to improve the strength. Zhou et al. [247] calcined residual soil-type EM at 800 °C and, by adjusting alkali concentration, alkali modulus, and liquid-to-solid ratio, obtained geopolymers with relatively high 28-day strength (~55 MPa). Bao et al. [248] verified the feasibility of using EM, FA, and slag for preparing greener geopolymer. Wang et al. [249] proposed a synergistic multi-activation strategy, integrating mechanical, thermal, and chemical activation to enhance the reactivity of shield tunneling EM as a geopolymer precursors. An L16(4^5) orthogonal experimental design was employed to quantitatively assess the effects of particle fineness, calcination temperature, holding time, Na2SiO3 modulus, and alkali content on the compressive strength of EM-based geopolymer. They reported that this activation method can significantly enhance the reactivity of EM, with the compressive strength of the geopolymer reaching up to 31.2 MPa. The thermal activation efficiency of EM is highly sensitive to temperature. Meanwhile, appropriate mechanical activation markedly increases the hydration reaction surface area and the amorphous phase content of the EM, but excessive activation may lead to the formation of a protective film covering the particle surfaces, which could delay or even hinder subsequent reactions. More importantly, with increasing alkali content, N-A-S-H gels rapidly precipitate around unreacted particles and fill adjacent pores, accompanied by the increase in silica-rich N-A-S-H phases.

4.2. Solidification/Stabilization of Hazardous Solid Waste

4.2.1. Hazardous Mine Tailings

In addition to the mine tailing mentioned in Section 4.1.1, there are many mine tailings that contain hazardous composites, especially for some non-ferrous metal ores. The release of heavy metals from tailings causes pollution in groundwater and air and finally enters the human body. Therefore, the stabilization of toxic composites for these mine tailings should be considered when reuse them [250].

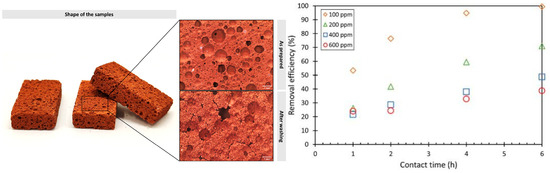

Sun et al. [251] investigated the effect of adding Na2S during the preparation of geopolymers using MK mixed with selected Cr tailings. The addition of S2− can reduce Cr(VI) to Cr(III), enhancing the solidification of Cr in the tailings, but it leads to a decrease in strength. XRD and XPS analyses indicate that during the geopolymerization, Cr3+ is fixed within the Al-O tetrahedral units ([−OAl(OH)3]−). Wei et al. [252] used mechanically activated vanadium tailings as raw materials to study the impact of milling time on geopolymer properties, obtaining a geopolymer with a compressive strength of 25 MPa. Wan et al. [253] used zinc tailings as raw materials and enhanced the mechanical properties of the resulting geopolymers by adding calcined kaolinite; the resulting geopolymers exhibited good solidification capacity for Pb2+, with Pb2+ content within a certain range (2%) increasing their compressive strength. Zhou et al. [254] alkali-activated hazardous solid wastes (tin mine tailings and fuming) to synthesize geopolymer. During geopolymerization, the heavy metals in tailings and slag can be stabilized through oxidization, precipitation, with immobilization efficiency for As and Cr of 95% and Cu2+, Zn2+, and Mn2+ for nearly 100%. Hassani et al. [255] produced a green bricks using copper ming tailing, where Cu2+ can be immobilized. These geopolymer bricks showed just 7.5% weight loss after 14 wet-dry cycles, mainly due to minor leaching of unreacted Na+ ions, which slightly increased porosity but caused no structural damage, and just 1.3% weight loss after 50 freeze–thaw cycles with small surface cracks but still high compressive strength.

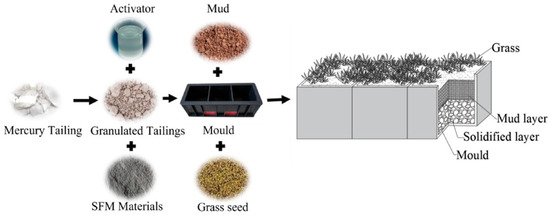

Lu et al. [256] combined steel slag, FA, and MK to obtain geopolymer for immobilization of mercury tailings (Figure 27). The tri-angle mixture design and potting experiments were conducted. The results indicated that the inclusion of 50% geopolymer reduced Hg2+ transport to the surface soil by ~90% and mercury concentration of herbaceous plant samples by 78%. Opiso et al. [257] combined palm oil fuel ash (POFA), as a high Al-bearing waste, and gold mine tailing for geopolymer synthesis. The heavy metals it contains can also be stabilized. In contrast, Pan et al. [258] used 5% FA/GGBFS/MK-based geopolymer for immobilization of 95% gold mine tailing. All harmful elements were well immobilized by precipitation, physical encapsulation, adsorption, and ion substitution. They also found that geopolymers show higher mechanical strength than OPC in stabilizing tailings.

Figure 27.

Preparation of geopolymer for mercury tailings immobilization [256].

Recently, geopolymerization based on acid-activation is also applied to dispose of hazardous mine tailings. Chen et al. [259] used phosphoric acid to activate copper tailing. However, the as-obtained acid-based geopolymers show low compressive strength of ≤8 MPa although they have good durability in both neutral and acidic environments and Cu2+ solidification effect. Zhao et al. [260] optimized the immobilization effect of uranium tailings by acid-based geopolymer using machine learning. The maximum compressive strength was ~18.9 MPa, with uranium leaching rate of 0.70 × 10−6 cm/d.

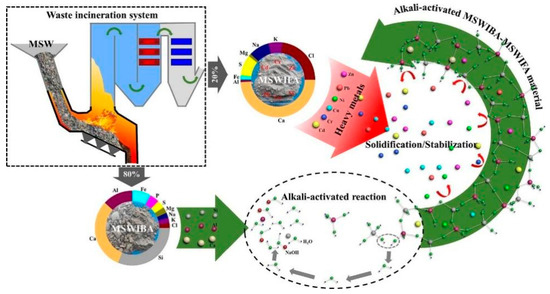

4.2.2. Municipal Solid Waste Ash

Municipal solid waste (MSW) is generated in large quantities during daily human activities. Since solid waste occupies vast amounts of land resources, contaminates soil and water bodies, and poses significant risks to human health, it is imperative to adopt harmless and volume-reduction treatments. Among available treatment technologies, incineration is recognized as one of the most effective methods for MSW management [261,262]. It not only substantially reduces the volume of waste but also enables energy recovery through power generation. Nevertheless, during the incineration process, fine particulate matter suspended in the flue gas can be captured by dust removal devices, resulting in the generation of incineration fly ash, which accounts for approximately 5% of the original waste mass. These fly ashes typically contain large amounts of heavy metal ions (e.g., Pb, Cu, Cr, Zn), and long-term exposure to such metals can cause severe health disorders in humans. In addition, toxic organic pollutants such as dioxins are also present in fly ash. Comparatively, the incineration bottom ash is the primary residue generated during MSW incineration, which is coarser in particle size and generally contains a heterogeneous mixture of slag, glass, ceramics, unburned carbon, and metallic fragments [263,264]. Although the leaching potential of toxic components in bottom ash is relatively lower than that of fly ash, bottom ash still contains significant amounts of heavy metals, soluble salts, and persistent organic pollutants. Therefore, incineration fly ash must be properly treated prior to landfilling. Based on these, geopolymerization can be considered as a good tool to dispose of MSW ash.