1. Introduction

The global construction sector continues to be a significant contributor to climate change, responsible for substantial greenhouse gas emissions and energy consumption. According to the UNEP Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction (2024/25), buildings and construction, including emissions from building materials and operations, accounted for approximately 34% of global energy demand and 34% of CO2 emissions in 2023. This highlights the pressing need to integrate sustainability into construction practices, particularly in rapidly urbanizing regions.

In developing countries, urban expansion has intensified the environmental and socio-economic challenges associated with unregulated growth [

1]. As cities continue to grow, embedding sustainable practices in building design, construction, and operation becomes increasingly vital to address issues such as resource depletion, pollution, and climate vulnerability [

2].

Ethiopia, in particular, is undergoing rapid urbanization and infrastructure development, especially in the commercial building sector. This growth is driven by economic development, demographic shifts, and internal migration [

3]. Despite the momentum, the adoption of sustainable construction practices remains limited. Most commercial buildings continue to be designed and constructed using conventional approaches that give little consideration to environmental efficiency, occupant well-being, or long-term cost-effectiveness [

1]. Furthermore, the absence of a nationally adopted sustainable building rating system and the weak enforcement of sustainability-related regulations have exacerbated the problem [

4].

In addition to these institutional and regulatory gaps, there is also a notable absence of empirical data on the actual implementation of sustainability practices within Ethiopia’s commercial building sector. While global frameworks and theoretical models exist, few studies have systematically evaluated real-world sustainability performance in Ethiopian construction [

5]. This lack of field-based evidence limits the ability of policymakers, professionals, and developers to assess progress, identify critical challenges, or make informed decisions to support sustainable transformation [

6].

Globally, a range of sustainability assessment frameworks such as LEED (USA), BREEAM (UK), and EDGE (IFC/World Bank) have been developed to guide the construction of environmentally responsible buildings [

7]. However, these systems are often costly, data-intensive, and complex to apply in low-resource contexts such as Ethiopia [

8]. Their lack of alignment with local construction practices, socio-economic conditions, and institutional capacities has limited their practical use [

9].

In response, indicator-based sustainability assessment methods have emerged as context-sensitive alternatives. These approaches allow for the selection and customization of indicators that reflect local priorities, construction realities, and policy frameworks [

10]. Such frameworks offer a more feasible means of evaluating building performance in developing countries, where formal certification processes may be impractical [

11].

This research aims to evaluate the implementation of sustainability practices in newly constructed commercial buildings in Ethiopia using a locally adapted, expert-informed indicator-based assessment framework. To guide this investigation, the study addresses the following research questions:

Which sustainability indicators are most relevant for assessing recently constructed commercial buildings in Ethiopia?

To what extent are sustainability practices implemented in recently constructed commercial buildings in Ethiopia?

By focusing specifically on commercial buildings, a category that represents a significant and rapidly expanding component of Ethiopia’s urban infrastructure, this study addresses a critical and underexplored area in the national discourse on sustainable development. Despite their high visibility, resource intensity, and potential to set sector-wide precedents, commercial buildings in Ethiopia have received limited scholarly attention in terms of their sustainability performance. This research bridges that gap by offering a context-specific and empirically grounded assessment framework tailored to the Ethiopian construction environment.

The study contributes to academic and professional knowledge by developing and applying a context-specific set of sustainability indicators tailored to low-resource, rapidly urbanizing environments. It establishes a foundation for consistent performance monitoring, informed policy formulation, and professional development across the construction sector [

12]. Additionally, the indicator-based framework offers replicable and scalable tools that can support the integration of sustainability principles into future building projects and regulatory strategies [

13].

Importantly, the findings are intended to inform and engage a wide range of stakeholders, including government agencies, urban planners, architects, developers, and environmental regulators who play a pivotal role in shaping Ethiopia’s urban future. By providing actionable insights into current gaps and opportunities, the research supports the transition toward more inclusive, resource-efficient, and climate-resilient cities. In doing so, it aligns directly with Ethiopia’s national development goals and global commitments, particularly the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, most notably SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and SDG 13 (Climate Action) [

14].

Globally, several policies and tools have contributed to measurable improvements in building sustainability. Singapore’s Green Mark system focuses on performance-based energy and water targets, utility benchmarking, and post-occupancy evaluations [

15]. The UAE’s Estidama Pearl system enforces minimum water budgets, material disclosures, and waste management during construction [

16]. South Africa’s SANS 10400-XA specifies envelope performance standards and efficient hot-water systems [

17]. Rwanda’s Green Building Minimum Compliance encourages passive cooling, daylight access, and low-flow fixtures in new permits [

18]. India’s Energy Conservation Building Code mandates efficiency standards for building envelopes and systems in large commercial structures [

19]. Well-defined baselines, straightforward compliance procedures, and routine inspections characterize these initiatives.

In Ethiopia, similar outcomes are constrained by data gaps, limited enforcement, and the absence of a national rating or code that sets measurable thresholds for energy, water, and waste [

20]. Capital budgets favor first cost over life-cycle performance. Project teams have limited access to commissioning and post-occupancy tools. These gaps explain the very low implementation scores observed in this study.

3. Methodology

This study used an exploratory sequential mixed-methods design to evaluate sustainability practices in newly constructed commercial buildings in Ethiopia. An indicator-based assessment approach was adopted due to the lack of a national rating system, ensuring flexibility and local relevance. The research was carried out in both methods: first, qualitative methods such as expert consultation and literature review were used to develop and validate indicators using the Relative Importance Index; second, quantitative methods were applied to assess sustainability implementation in 23 selected buildings.

3.1. Analytical Framework

The analytical framework for this study was developed to provide a structured and context-sensitive approach to evaluating the implementation of sustainability practices in commercial buildings. It comprises three interrelated stages that reflect the logical progression of the research.

Stage 1: Sustainability indicators were identified through a comprehensive review of international sustainable building standards and adapted to the Ethiopian context. These indicators were then validated and prioritized using expert input and the Relative Importance Index (RII), ensuring both local relevance and conceptual rigor. The reliability of the indicator set was confirmed through Cronbach’s Alpha to ensure internal consistency [

36].

Stage 2: The validated indicators were operationalized into a structured Likert-scale survey, which was administered to stakeholders of 23 purposively selected commercial buildings. The survey data were quantified to generate implementation scores for each building, reflecting the degree of sustainability integration.

Stage 3: The implementation scores were normalized and categorized into five levels, ranging from very low to very high, allowing for comparative analysis across cases. Overall, the analytical framework provided a coherent method for translating complex sustainability concepts into measurable, actionable insights tailored to the realities of Ethiopia’s built environment.

Overall, the analytical framework provided a coherent method for translating complex sustainability concepts into measurable, actionable insights responsive to the realities of Ethiopia’s built environment.

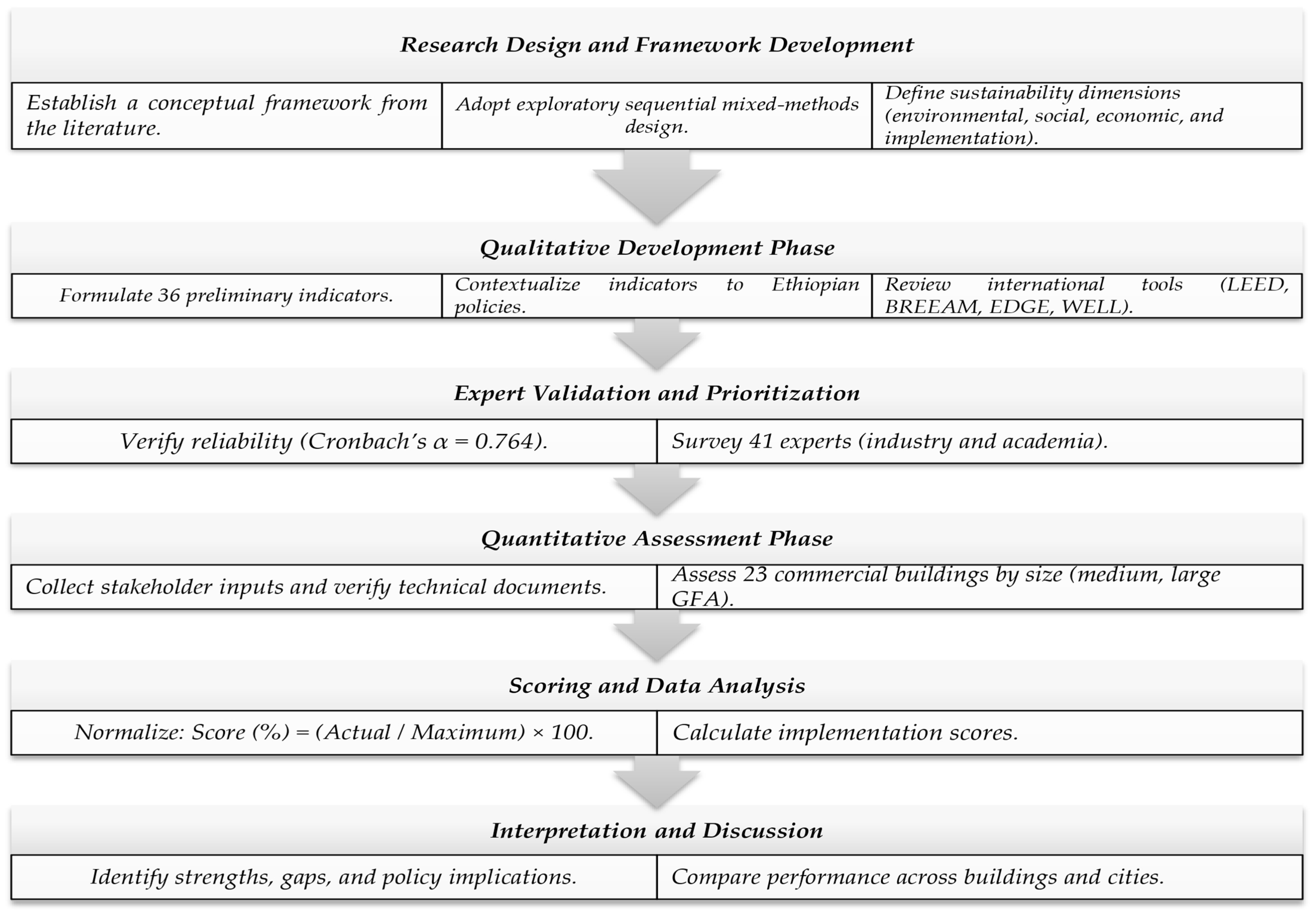

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the research methodology followed a multi-stage sequence encompassing conceptual development, expert validation, and quantitative assessment, designed to ensure methodological rigor and contextual relevance to sustainability practices in Ethiopian commercial buildings.

3.2. Target Population and Sampling Approach

The study targeted professionals from both industry and academia with demonstrated expertise in sustainability, balancing practical insights from construction practitioners with theoretical perspectives from scholars. Using purposive sampling, 41 experts were selected: 28 from construction and real estate (e.g., contractors, engineers, project managers, consultants) and 13 from academic institutions (professors, lecturers, researchers, and doctoral candidates in architecture and sustainable development). This expert-based, non-random sampling was appropriate for exploratory research requiring specialized knowledge [

31].

3.3. Sampling Technique and Size for Commercial Buildings

A purposive sampling method was applied to select 23 commercial buildings located in major urban centers, including Addis Ababa, Bahir Dar, Gondar, Gorgora, Hayk, and Dessie. The selection criteria considered building type, construction status, sustainability features, and gross floor area. The sample comprised 10 office buildings, 7 mixed-use developments (combining office and retail functions), 4 retail buildings, and 2 hotel or resort buildings, reflecting the diversity of Ethiopia’s urban commercial construction sector. Among these, 16 buildings were completed and operational, while 7 were recently completed or in the final finishing stages. Based on national classification, 14 buildings were categorized as medium-scale (5000–20,000 m2 gross floor area) and 9 as large-scale (>20,000 m2).

This classification ensured representation across varied functional types, project sizes, and construction stages, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of sustainability implementation patterns. The sample size was mathematically justified using Yamane’s formula [

37] for finite populations:

where N = 80 (estimated population of newly constructed commercial buildings in the target cities) and e = 0.1 (10% margin of error). The resulting n = 23 confirms the adequacy of the selected sample for exploratory research in the context of Ethiopia’s commercial building sector. Purposive sampling is widely recognized as an appropriate non-probability technique for expert-driven sustainability studies that require specialized knowledge and representativeness across typologies, rather than random distribution [

37,

38,

39]. This approach ensured statistical sufficiency while maintaining feasibility for field-based sustainability assessment across multiple locations.

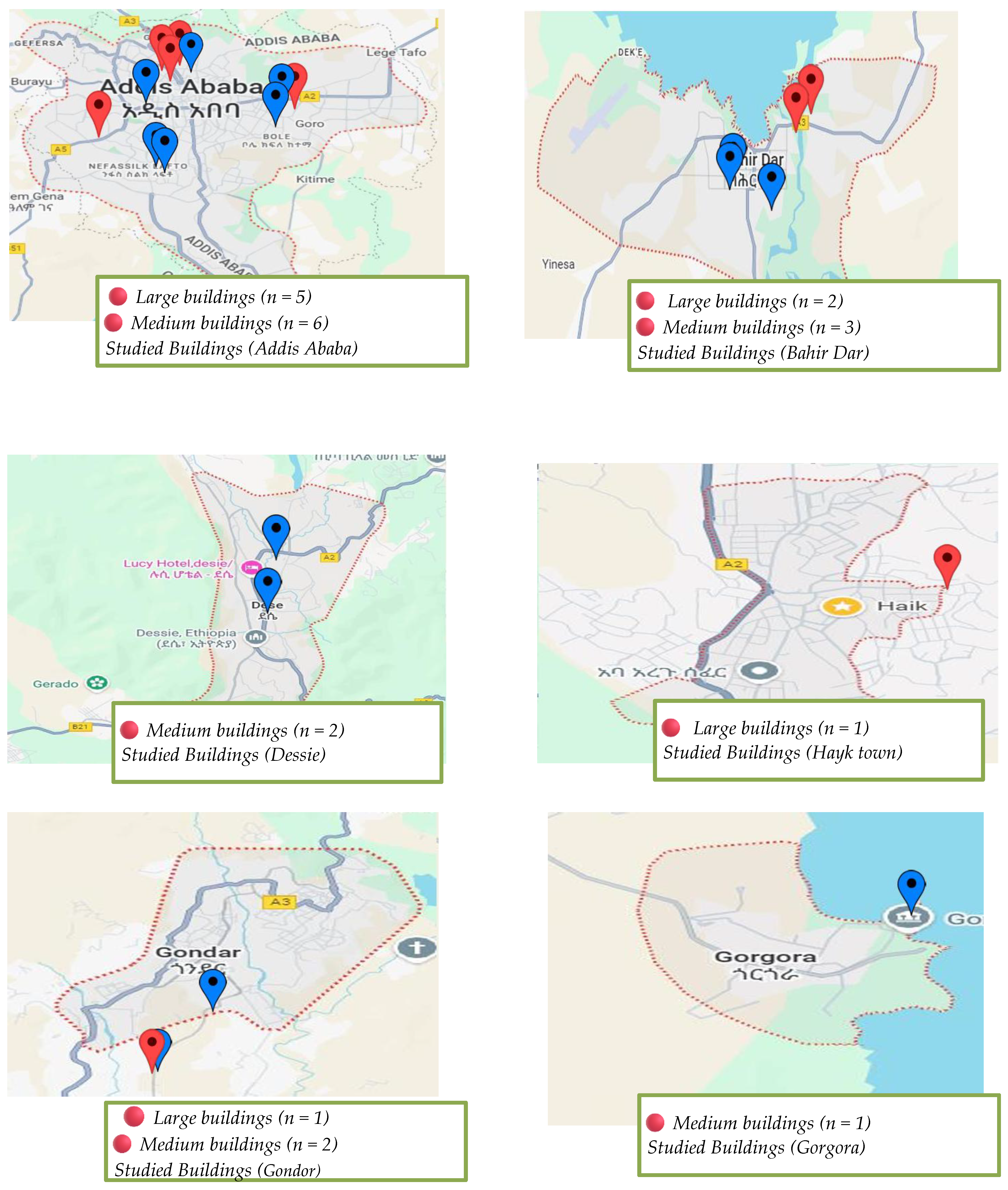

As shown in

Figure 2, the assessed commercial buildings are geographically distributed across six major Ethiopian cities, representing both medium- and large-scale developments selected to capture regional diversity in construction practices.

3.4. Data Collection

Data collection proceeded in two phases. First, a structured questionnaire was distributed to the 41 experts, who evaluated 36 proposed sustainability indicators using a five-point Likert scale, informing the validation and refinement of the framework. In the second phase, the 24 validated indicators were used to assess sustainability implementation across the 23 selected buildings through surveys with engineers, facility managers, and project representatives. Responses were cross-validated with project documentation, including architectural drawings, technical specifications, reports, and permit files to ensure accuracy and reliability.

3.5. Data Analysis and Indicator Selection

The responses were analyzed using the Relative Importance Index (RII) to prioritize the indicators based on the consensus of expert opinion [

31]. The RII was calculated using the following formula:

where

W = the weight assigned to each indicator by respondents

A = The highest possible weight (5)

N = The total number of respondents (41)

Indicators were ranked based on their RII values. A cut-off point of approximately 0.72 was established to select the most significant indicators, reflecting a high level of agreement among experts regarding their relevance.

3.5.1. Instrument Reliability

Cronbach’s Alpha is a widely used statistical tool for assessing the internal consistency of research instruments. A value above 0.70 generally indicates acceptable reliability, meaning the items in a scale are closely related and measure the same underlying construct [

40]. This test helps ensure that data collected through questionnaires or indicator sets is consistent and trustworthy for further analysis [

41].

3.5.2. Scoring Framework for Sustainability Implementation in Commercial Buildings

To assess the extent to which commercial buildings in Ethiopia are incorporating sustainability principles into their design, construction, and operational practices, this study applied a structured scoring framework based on the 24 validated sustainability indicators. Each indicator was rated on a five-point Likert scale, where a score of 1 represented “Not Implemented” and 5 represented “Fully Implemented.”

The scoring system assumes a minimum possible score of 24, representing the baseline scenario in which none of the indicators is implemented (i.e., each rated at 1). The maximum possible score is 120, which corresponds to full implementation of all 24 indicators at the highest rating (5 per indicator).

- ❖

Scoring Framework

Minimum possible score = 24 (Baseline, if none of the indicators are implemented)

Maximum possible score = 120 (Full implementation of all 24 indicators at highest weight)

Implementation Score (%):

This percentage-based scoring method makes it easy to measure how well sustainability is being applied. It allows for comparing different buildings and helps group them by performance level, making it useful for analysis and setting future standards in Ethiopia’s commercial building sector.

3.5.3. Development of Sustainability Indicators

The sustainability indicators selected for this study were derived from internationally recognized sustainable building assessment frameworks that are widely acknowledged for their comprehensiveness and global applicability.

Table 2 presents each indicator alongside its corresponding source(s), demonstrating alignment with globally established sustainability principles while remaining adaptable to the Ethiopian construction context.

4. Results

This section presents the findings of the study, organized according to the two main research questions. The first part addresses Research Question 1, which focuses on identifying the most relevant sustainability indicators for assessing commercial buildings in Ethiopia. It includes the results of expert evaluations and the ranking process used to develop a context-specific assessment framework. The second part addresses Research Question 2, which examines the extent to which sustainability indicators have been implemented in recently constructed commercial buildings. It presents the results of a field assessment conducted across 23 commercial buildings using the validated indicators. Together, the findings provide a comprehensive understanding of current sustainability practices, reveal key performance gaps, and offer insights for improving the integration of sustainability in Ethiopia’s commercial building sector.

To address Research Question 1, which focuses on identifying the most relevant sustainability indicators for assessing commercial buildings in Ethiopia, the study began by evaluating the reliability of the initial set of indicators. A reliability test using Cronbach’s Alpha was conducted on the initial 36 sustainability indicators using MS Excel 2024 and IBM SPSS Statistics 29 software. The result, a value of 0.764, indicates good internal consistency, confirming that the indicators were statistically reliable for expert evaluation and further analysis.

The internal consistency of the 36 sustainability indicators was evaluated using Cronbach’s Alpha, yielding a reliability coefficient of 0.764, as presented in

Table 3.

Thus, the instrument used in this study demonstrates sufficient reliability, supporting the credibility of the subsequent findings and analyses.

4.1. Ranking of Sustainability Indicators

To develop a context-specific framework for evaluating sustainability in commercial buildings, an initial set of 36 indicators was evaluated based on expert input.

Table 4 presents these indicators along with their corresponding statistical metrics and ranks. Of the 36 indicators, 24 met the predefined threshold criteria and were selected for inclusion in the final sustainability assessment framework. The table includes the sum of weights (∑W), the maximum possible weight (A × N = 5 × 41 = 205), mean score, standard deviation, calculated Relative Importance Index (RII), and the resulting rank of each indicator. Indicators with higher RII values were considered more significant, reflecting stronger consensus among experts.

4.2. Final Set of Sustainability Indicators for Commercial Building Assessment in Ethiopia

Table 5 presents the final set of 24 sustainability indicators selected for assessing commercial buildings in Ethiopia. These indicators were identified based on their Relative Importance Index (RII), derived from expert ratings on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Not important to 5 = extremely important). A threshold RII value of 0.717, corresponding approximately to a mean rating of 3.6, was applied to determine inclusion. This cutoff aligns with established practices in the literature [

31], ensuring that the selected indicators reflect strong expert consensus and are both statistically valid and contextually relevant.

The final set of sustainability indicators was grouped according to project phase. Construction-phase indicators capture site-based and material-related sustainability actions, while operation-phase indicators focus on energy, water, and occupant comfort performance. Cross-cutting indicators reflect managerial, policy, and training elements applicable throughout the project lifecycle. This classification supports a more holistic understanding of sustainability integration across design, construction, and operational stages.

4.3. Sustainability Implementation Assessment Results for Commercial Buildings

To address Research Question 2, which investigates the extent to which sustainability indicators have been implemented in recently constructed commercial buildings in Ethiopia, the study conducted an implementation assessment across 23 buildings using the validated set of indicators.

To evaluate the practical application of sustainability principles in commercial buildings, implementation scores were calculated for the 23 buildings using the standardized scoring framework. Each building was assessed against 24 validated indicators, with total scores normalized to a percentage scale ranging from 0% (no implementation) to 100% (full implementation).

Before analyzing the results, the internal consistency of the 24 selected indicators was tested using Cronbach’s Alpha. The reliability test was conducted using SPSS software, and the resulting alpha value was 0.743, indicating a good level of internal consistency among the indicators. This confirms that the instrument used to measure sustainability implementation across the buildings was statistically reliable and suitable for quantitative analysis.

Table 6 presents the total raw score for each building, along with the corresponding implementation percentage. This enables a comparative understanding of how effectively each building incorporates sustainability measures into its design, construction, and operation within the Ethiopian context.

4.4. Summary of the Results

The implementation scores across the 23 commercial buildings ranged from 4.17% to 27.08%, reflecting an overall low level of sustainability adoption. The highest score was achieved by Building CB03, with 27.08%, followed by CB21 and CB18, which scored 16.67% and 15.63%, respectively. On the lower end, Building CB02 recorded the lowest score at 4.17%, with CB13 and CB22 following closely at 5.21% each. Notably, more than 70% of the buildings scored below 15%, highlighting the limited integration of sustainability measures within current commercial building practices in Ethiopia.

Figure 3 shows the categorization of implementation levels based on percentage scores, classifying buildings into Very Low, Low, Moderate, High, and Very High categories.

This score indicates the extent to which the sustainability measures have been implemented across the commercial buildings. However, it does not capture the absolute quality or specific scope of implementation activities. Instead, it indicates the relative degree of compliance with the selected indicators.

5. Discussion

The first research question aimed to identify sustainability indicators most relevant to Ethiopia’s commercial construction sector. Through an extensive review of international sustainable building assessment systems, 36 indicators were initially chosen. Each indicator was backed by at least two independent sources and considered suitable for adaptation in developing countries. These indicators were then prioritized through expert assessment using the Relative Importance Index (RII) method. Based on a threshold RII value of 0.717, which corresponds to a mean rating of about 3.6, As a result, 24 indicators were retained for the final assessment framework, following established sustainability research methods.

5.1. Sustainability Assessment Indicators for Ethiopia’s Commercial Construction Sector

The results of this study reveal that environmental indicators dominate sustainability priorities in Ethiopia’s commercial building sector. The highest-ranked parameters use of renewable energy sources (RII = 0.878), waste management during construction (0.868), sustainable landscaping (0.859), low-emission construction equipment (0.859), and efficient HVAC systems (0.844) demonstrate a strong emphasis on environmental performance. This finding is consistent with international literature, which identifies energy efficiency, waste reduction, and sustainable material use as core dimensions of green construction [

1,

26,

59]. These priorities are also reflected in global rating frameworks such as LEED and BREEAM, where environmental categories typically account for the largest share of total assessment scores [

60].

The prominence of environmental factors aligns with the observations of Zarghami and Fatourehchi [

8], who noted that developing countries often emphasize quantifiable, technology-driven sustainability measures that are easier to monitor and justify to stakeholders. This tendency may be attributed to the relative ease of implementing environmental technologies compared to the more complex institutional reforms required for social and economic sustainability.

Social indicators also ranked highly in this study, particularly community engagement in planning and worker health and safety compliance. These results support earlier findings that social well-being and participatory decision-making are gaining traction in construction sustainability discourse [

9,

13]. However, lower-ranked indicators such as stakeholder education programs and public transportation access suggest that social sustainability remains underdeveloped in Ethiopia’s commercial projects. This mirrors global trends where social dimensions are often overshadowed by environmental metrics due to limited regulatory enforcement and public awareness [

61].

Economic indicators, including incentives or subsidies secured (RII = 0.771) and life-cycle cost considerations, were among the lowest-ranked. This pattern is consistent with studies by Kinemo [

31] and Rwanda GBC [

18], which highlight financial constraints and weak policy enforcement as major barriers to sustainable investment in sub-Saharan Africa. The low prioritization of economic factors may also reflect the absence of reliable cost data and fiscal mechanisms that incentivize long-term sustainability planning.

Implementation indicators, such as defining sustainability goals in project plans, post-occupancy evaluation, and staff training, received moderate to low attention. This is in line with findings from Häkkinen and Belloni [

62] and Darko and Chan [

61], who emphasized that fragmented project management systems and limited technical capacity often hinder the systematic integration of sustainability metrics. The relatively low ranking of post-occupancy evaluation (RII = 0.722) underscores a persistent gap between design intent and operational performance. Similar challenges have been documented in South Africa and India, where post-construction monitoring remains underutilized [

19].

The distribution of indicator rankings confirms that Ethiopia’s commercial building sector is in the early stages of sustainability integration. While environmental actions are acknowledged, their application is inconsistent. Social and economic pillars require stronger institutional frameworks, targeted incentives, and capacity-building efforts. These findings reinforce earlier research suggesting that sustainability adoption in developing countries is constrained less by awareness and more by enforcement, training, and financial support mechanisms [

13,

61]. The proposed indicator framework offers a context-sensitive, empirically grounded tool for establishing national benchmarks and guiding policy toward balanced, lifecycle-oriented sustainability practices in Ethiopia.

Given that Ethiopia currently lacks a formal national sustainability assessment framework, future research could integrate the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) with the Relative Importance Index (RII) to strengthen methodological rigor and support the gradual establishment of such a framework. While RII offers practicality and contextual relevance for current low-resource conditions, AHP can provide hierarchical weighting and consistency testing that enhance analytical reliability. Combining these methods would allow deeper examination of indicator prioritization and lay the groundwork for a standardized and evidence-based sustainability assessment model suitable for Ethiopia’s construction sector.

5.2. Sustainability Implementation Assessment in Recently Constructed Commercial Buildings in Ethiopia

The empirical assessment of 23 recently constructed commercial buildings revealed that the level of sustainability implementation across Ethiopia’s urban construction sector remains extremely low. Building implementation scores ranged from 4.17% to 27.08%, with an average score of 10.64%, indicating that sustainability principles are only marginally integrated into current practice. More than 70% of the assessed buildings scored below 15%, underscoring the limited adoption of sustainability measures during both the design and operational phases.

This outcome confirms that sustainability remains at an early stage of implementation within Ethiopia’s construction industry. Similar findings have been reported in other developing countries, where weak policy frameworks and resource limitations constrain progress. For instance, Assefa et al. [

3] observed an average sustainability compliance level of about 40% in pilot-rated Ethiopian projects, while Zarghami and Fatourehchi [

8] reported 35–55% compliance rates in developing countries implementing adapted EDGE systems. Compared to these studies, the 10.64% average score in this research highlights a more pronounced implementation gap in Ethiopia’s commercial building sector.

The low scores can be attributed to several interrelated barriers. Institutional challenges such as limited enforcement of existing sustainability regulations, lack of standardized building performance metrics, and absence of incentive mechanisms continue to hinder progress. Financial constraints also play a major role, as developers tend to prioritize short-term cost savings over long-term environmental and social benefits. Darko and Chan [

61] and Boz and El-Adaway [

13] similarly noted that the absence of fiscal policies and technical capacity in developing countries prevents the mainstreaming of sustainability principles.

Moreover, the minimal difference between the highest (27.08%) and lowest (4.17%) performing buildings suggests that sustainability adoption is not limited to project-specific conditions but reflects a system-wide underperformance. The findings therefore align with previous research emphasizing the need for national frameworks, training programs, and performance-based incentives to bridge the gap between sustainability awareness and implementation.

5.3. General Observations and Patterns

The results indicate that sustainability implementation in the assessed buildings is minimal and highly inconsistent. Only three buildings, CB03, CB01, and CB04, exceeded the 20% threshold, with CB03 scoring the highest at 27.08%. These higher-performing cases likely reflect isolated efforts rather than systemic industry trends. In contrast, buildings such as CB02, CB08, CB12, CB13, CB17, and CB22 scored below 7%, with CB02 performing the lowest at 4.17%. A larger group, including CB05-CB09, CB11-CB14, CB17, CB19, CB22, and CB23, clustered in the 5–10% range. This pattern suggests that only superficial or fragmented sustainability measures are being adopted, lacking strategic integration into the design or construction processes.

As illustrated in

Figure 4, the implementation scores of the assessed commercial buildings show considerable variation, with most projects achieving values below 15%, indicating limited integration of sustainability measures during construction and operation. A few buildings, particularly CB01, CB03, and CB18, exhibit relatively higher performance, reflecting partial application of sustainable design strategies and compliance with selected sustainability criteria. These results highlight the uneven adoption of sustainability practices among commercial developments in Ethiopia and underscore the need for stronger regulatory frameworks, institutional capacity, and awareness to promote consistent implementation across the sector.

5.4. Central Tendencies and Dispersion

The average sustainability implementation score across all 23 buildings was 10.64%. Notably, over 69.56% of buildings scored below this average. The narrow score range and minimal variance suggest that underperformance is not limited to specific projects but reflects broader, systemic deficiencies within the commercial construction sector. The consistently low scores across different building types and locations also highlight the absence of supportive policy frameworks, technical expertise, and sustainability awareness among industry professionals [

61].

5.5. Implications of Uniformly Low Implementation Score

The assessment reveals a consistently low level of sustainable construction implementation. This widespread underperformance indicates systemic challenges rather than isolated project issues and has serious implications for environmental, economic, and social sustainability.

Although earlier reports [

23] noted limited progress in enforcing sustainability-related regulations in Ethiopia, more recent developments indicate modest but notable improvements. The Ethiopian Building Proclamation No. 624/2009 and the Construction Industry Policy [

63] remain the principal legal instruments governing building practices, while the National Building Energy Code [

64] and the Green Building Minimum Compliance Framework [

65] are emerging initiatives aimed at improving energy efficiency, water conservation, and environmental performance in urban construction. Despite these advances, enforcement and adoption remain inconsistent, largely due to resource constraints, low institutional capacity, and limited awareness among project stakeholders [

63,

64,

65]. Widespread integration across the commercial building sector remains limited, underscoring the need for stronger regulatory mechanisms and local capacity-building to sustain the benefits of such international cooperation.

The findings also point to significant capacity and knowledge gaps within the construction industry. Most professionals lack training in sustainable design and materials, and there is limited access to sustainable technologies and building systems. Without targeted education and certification programs, sustainable practices will remain underutilized [

32].

Financially, the failure to implement sustainable strategies results in higher long-term operational costs for building owners and tenants [

66]. In urban centers like Addis Ababa, this trend places additional pressure on the electricity grid and public infrastructure, increasing environmental degradation and energy insecurity [

67].

Socially, the implications are also profound. Many commercial buildings fail to provide adequate indoor air quality, natural lighting, and thermal comfort issues which disproportionately affect workers in retail, office, and service industries. This not only undermines health and productivity but also contradicts Ethiopia’s national Ten-Year development goals tied to equitable urban growth [

68].

To address these problems, a coordinated response is necessary: reinforcing enforcement of building codes, incorporating sustainability into technical training, and offering financial and regulatory incentives for developers [

30]. Without these measures, Ethiopia risks committing to inefficient, unsustainable infrastructure that will be expensive to retrofit and harmful to long-term development goals [

5].

5.6. Benchmarking and International Comparison

When benchmarked against global sustainability frameworks, the results indicate that Ethiopia’s commercial buildings perform substantially below international certification thresholds. Global rating systems, such as LEED, BREEAM, and EDGE, generally require projects to meet at least 50% of the total assessment criteria to achieve entry-level certification [

60]. In contrast, the highest-performing building in this study attained only 27.08%, confirming that sustainability implementation within Ethiopia’s commercial building sector is still at an early developmental stage.

Similar performance gaps have been reported in other developing nations. Zarghami and Fatourehchi [

8] found that buildings in countries such as Iran and Malaysia achieved between 35% and 55% of assessment criteria, while Boz and El-Adaway [

13] observed that African and Middle Eastern projects frequently fall below 40% due to weak institutional enforcement and insufficient awareness of sustainability guidelines. Studies in Rwanda and Kenya have also shown that limited government incentives and the absence of national benchmarking frameworks hinder full integration of sustainable construction practices [

9,

18].

In contrast, countries that have established their own localized rating frameworks, such as India with the Energy Conservation Building Code (ECBC) [

6] and Singapore with the Green Mark system, have achieved measurable improvements in sustainable design and operational performance [

60]. These comparative insights reinforce that national-level policy alignment, capacity development, and funding mechanisms are critical drivers of progress.

The persistent performance gap observed in Ethiopia reflects the same structural barriers reported by Abebe et al. [

1] and Gashaw et al. [

26], including limited technical expertise, lack of professional training, and weak policy implementation. Addressing these challenges will require the establishment of a national sustainability rating framework, stronger institutional mechanisms, and targeted investment programs. Without such coordinated efforts, Ethiopia is unlikely to achieve the sustainability milestones defined under SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and SDG 13 (Climate Action) [

57].

6. Conclusions

This study provides one of the first empirical assessments of sustainability implementation in Ethiopia’s commercial building sector, addressing a significant gap in both academic research and national policy. A total of 36 sustainability indicators were initially identified from international frameworks such as LEED, BREEAM, EDGE, and WELL. Through expert evaluation and application of the Relative Importance Index (RII), the list was refined to 24 validated indicators, supported by a Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient of 0.764, indicating strong internal consistency. Among these, the highest-ranked indicators were the use of renewable energy sources (RII = 0.878), waste management during construction (RII = 0.868), sustainable landscaping (RII = 0.859), and low-emission construction equipment (RII = 0.859). These results highlight a clear prioritization of environmental factors, reflecting the global shift toward energy efficiency and resource-conscious design.

In terms of practical implementation, the assessment of 23 commercial buildings demonstrated very limited integration of sustainability practices. Implementation scores ranged from 4.17% to 27.08%, with an average of 10.64%, and more than 70% of the evaluated buildings scored below 15%. This outcome indicates that sustainable construction remains at an early stage of adoption. The findings point to several systemic barriers, including weak institutional enforcement, low technical capacity, limited awareness among professionals, and insufficient financial or regulatory incentives.

Despite these challenges, the indicator-based framework developed in this study provides a quantitative and replicable foundation for sustainability benchmarking in low-resource settings. By integrating expert-validated indicators and a structured scoring methodology, the framework enables continuous performance tracking and evidence-based policy formulation.

To advance sustainability in Ethiopia’s commercial construction sector, a coordinated national strategy is essential. This should include mandatory sustainability benchmarks, capacity-building programs, and financial incentives to motivate developers. Increasing the current average sustainability score of 10.64% toward the 50% threshold required for entry-level global certification (e.g., LEED or BREEAM) would represent a major milestone in aligning Ethiopia’s construction practices with international standards.

We recommend that future studies extend this work by, first, applying the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to the validated indicator set to obtain hierarchical weights and evaluate judgment consistency. Second, conducting triangulation between the Relative Importance Index (RII) and AHP, along with formal sensitivity analysis, to test the reliability of indicator rankings across methods. Third, integrating AHP-derived weights into pilot scoring of additional buildings, ideally alongside post-occupancy data, to examine effects on building-level scores and policy targets.

Ultimately, embedding sustainability within Ethiopia’s rapidly urbanizing construction landscape is vital to reducing environmental impacts, improving building performance, and fulfilling national commitments to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and SDG 13 (Climate Action). The study therefore contributes both a methodological innovation and a quantitative evidence base for guiding the Ethiopian construction industry toward a more sustainable and resilient future.