1. Introduction

The stress evolution process of concrete structures during the construction stage is jointly influenced by changes in material properties and various external actions. The strength and elastic modulus of early-age concrete continue to increase, and the material remains in a significantly non-steady state [

1,

2,

3]. Recent multiphysics simulations have further revealed the complex coupling of hydration kinetics and mechanical response at the mesoscopic scale [

4], while in situ and numerical investigations of ultra-high-performance concrete composite decks have demonstrated pronounced early-age shrinkage effects and their impact on stress development [

5]. Meanwhile, factors such as shrinkage and expansion compensation, temperature gradient changes, prestress application, dead load, and construction live load disturbances act in combination over time and space, leading to monitoring strain signals that exhibit strong non-stationarity and multi-frequency characteristics [

6,

7,

8]. Recent studies further refine temperature-induced component separation in bridge strain monitoring, improving decoupling under mixed actions [

9,

10]. This complexity is particularly prominent in locations with strong structural constraints, such as cast-in-place segments in negative moment regions and wet joints [

11,

12], where the stress evolution directly relates to construction quality control and long-term service performance prediction [

13,

14]. Similar concerns have also been highlighted in studies on early-age cracking in concrete cap beams under high-strength material properties and strong formwork constraints [

15].

Many existing strain identification and load inversion methods are based on steady-state assumptions, relying on the material and structural properties remaining constant during monitoring [

16]. However, in the early-age construction stage, the rapid changes in material properties invalidate the steady-state assumption, and traditional parameter identification methods based on statistical features or frequency-domain analysis cannot accurately separate strain components caused by different factors [

17,

18]. In addition, construction disturbances and temperature variations often highly overlap in the time domain, and their differences in frequency and amplitude characteristics can be further blurred by the non-steady behavior of materials, making signal decoupling and mechanism discrimination a significant challenge. Field studies on long-span steel arch bridges have shown that periodic thermal fluctuations alone can induce considerable deformation responses [

19], highlighting the necessity of refined methods for separating overlapping effects.

In civil engineering signal processing, wavelet analysis has been widely used since the late 20th century for tasks such as structural dynamic response analysis, damage detection, load identification, and noise suppression, owing to its multi-scale time–frequency localization characteristics [

20,

21]. Early studies mainly focused on vibration and acceleration signals with high-frequency sampling, using wavelet transforms to extract local transient features for structural modal identification and condition monitoring [

22]. In contrast, the empirical mode decomposition (EMD) method can adaptively decompose non-stationary signals into intrinsic mode functions at different time scales, making it suitable for multi-source signal separation and nonlinear trend extraction [

23,

24]. Existing studies have applied EMD to the separation of temperature effects in long-span bridges and wind load response analysis [

25,

26], but systematic research on the combined application of wavelet analysis and EMD to monitoring data of concrete structures during construction remains limited [

27].

The main motivation for introducing wavelet analysis in this study is that concrete strain signals during the construction stage contain both changes with known patterns (such as disturbances caused by construction procedures and daily periodic temperature fluctuations) and changes that are difficult to quantify directly (such as early-age material property evolution and random load effects). Wavelet analysis can effectively filter out signals from non-target frequency bands while maintaining time resolution, thus providing a cleaner input for subsequent EMD [

28]; EMD can then further separate modal components corresponding to different physical processes [

29]. Unlike traditional methods that rely solely on statistical features of signals, this study introduces construction logs and known event information as external constraints in the signal separation process [

30], enabling both qualitative and quantitative analysis of trends and amplitudes. This method is particularly suitable for monitoring data under non-steady early-age conditions of concrete, as it can effectively identify the main influencing factors and provide a basis for stress evolution mechanism analysis.

Scientifically, this study aims to address the unresolved problem of identifying and quantifying multi-source strain components under transient, non-steady construction conditions, thereby bridging the gap between empirical field monitoring and mechanism-based understanding of stress evolution in concrete structures. Based on this approach, this study uses actual bridge construction monitoring to select two key locations—cast-in-place segments in negative moment regions—and systematically analyzes their stress evolution characteristics during early age, construction disturbance, and variable load stages. A total strain decomposition model is established to quantify the contribution ratios of different components. Unlike existing approaches that are primarily developed for steady-state monitoring or post-construction analysis, the present study introduces a new analytical framework aimed at identifying multi-source strain components and interpreting stress evolution mechanisms under transient, non-steady construction conditions. The results can provide a reference for interpreting monitoring data, identifying disturbance causes, and predicting long-term performance of concrete structures during the construction stage.

2. Methodology

2.1. Project and Monitoring Overview

The monitoring objects of this study come from one typical cast-in-place concrete structural form of a bridge—full-width cast-in-place prestressed concrete bridge decks in negative moment. The measured area is located at the pier-top position of a composite girder structure, where the concrete is simultaneously affected by multiple processes during early construction, such as casting, prestressing, and adjacent segment construction.

For the monitoring of the cast-in-place bridge deck in the negative moment region, string-type strain gauges were tied inside the reinforcement and on the surface of the steel girder flange before concrete casting, along with environmental temperature sensors. In this study, the negative moment region refers to the hogging area over the supports, where the bending moment changes from positive to negative and the top fiber of the deck is in tension. The sign convention adopted in this paper defines positive moments as sagging (bottom tension) and negative moments as hogging (top tension). The measurement points covered key stress positions at the upper and lower edges of the bridge deck and the adjacent steel girder, with a total of 27 effective strain channels, as shown in

Figure 1. The monitoring period lasted for six weeks, covering multiple construction stages, including concrete casting, prestressing, and structural connection, in order to obtain strain evolution data under different ages and working conditions.

Overall, the methodological framework of this study consists of four main stages: (1) field monitoring layout, where representative structural components (cast-in-place segments in the negative moment region) were selected and equipped with strain and temperature sensors; (2) data acquisition and preprocessing, involving automatic field data collection, temperature correction, outlier removal, and wavelet-based noise filtering to ensure the accuracy and stability of the measured data; (3) multi-modal signal decomposition and identification, in which wavelet filtering and empirical mode decomposition (EMD) were used to separate strain components associated with shrinkage, temperature variation, construction disturbances, and live loads; and (4) stress evolution analysis and verification, where the identified strain components were interpreted to reveal stage-specific stress evolution characteristics and verify the applicability of the proposed approach to construction-stage monitoring of concrete structures. This structured process provides a coherent methodological basis for linking field monitoring data with quantitative interpretation of stress evolution mechanisms.

2.2. Signal Acquisition and Preprocessing

The strain data of both monitoring objects were collected using string-type strain gauges, with data acquisition completed through an on-site automatic collection system. After the measurement points were installed, all strain gauges were connected to a multi-channel data logger and a solar-powered supply unit. The data were recorded at regular intervals and uploaded to a remote server, forming stable time-series datasets. To better illustrate the experimental background and monitoring setup,

Figure 2 presents the actual field configuration of the bridge deck in the negative moment region, which represents the most critical location for observing early-age stress evolution under strong structural restraint. As shown in

Figure 2a, the string-type strain gauges and temperature sensors were installed near the wet-joint area, where the cast-in-place concrete is directly connected to the prefabricated deck slab. This configuration captures the typical boundary conditions and restraint effects that dominate the transient stress development process.

Figure 2b shows the automatic data-acquisition box and its solar-powered supply system, which ensured stable and continuous monitoring throughout the entire construction period. The sampling interval for the monitoring of the bridge deck in the negative moment region was 30 min. The raw strain data obtained from acquisition were subjected to multi-stage preprocessing before further analysis, including temperature correction, outlier removal, and noise filtering. First, to eliminate systematic errors caused by the difference in thermal expansion coefficients between materials, temperature correction was applied to the raw strain sequences. The correction method is based on the difference between the linear expansion coefficients of the steel string in the gauge and the concrete, and the correction formula is as follows:

where

is the measured raw strain;

is the measured temperature;

is the initial temperature;

is the structural linear expansion coefficient, taken as 10.0 με/°C (typical for reinforced concrete); and

is the linear expansion coefficient of the steel string, taken as 12.2 με/°C.

After temperature correction, outlier detection and removal were carried out on the data sequences. For sudden abnormal values caused by nighttime sensor power loss or accidental contact during construction, statistical methods were applied for identification, following the Z-score standard or Chauvenet’s criterion, to ensure continuity and stability of the data series. Some extreme values could also be manually checked and corrected using construction logs and on-site feedback.

To further improve signal quality and reduce the influence of high-frequency interference on modal decomposition, wavelet transform was introduced for filtering and noise reduction. Through trial calculations, the appropriate wavelet basis function and decomposition levels for different channels were determined. The original signal was decomposed into multiple scales, retaining the low-frequency approximation part as the effective signal while removing high-frequency disturbance components caused by temporary loads, construction noise, or power fluctuations. The filtered signal was then used for subsequent modal identification and classification analysis.

2.3. Multi-Modal Response Identification Method

To separate response components from different sources in the strain time-series data obtained from real bridge monitoring during the construction stage, a signal processing method combining wavelet filtering and empirical mode decomposition (EMD) was adopted. This method can perform modal decomposition of non-stationary, multi-scale strain signals without relying on a priori models, thereby extracting typical features such as transient disturbances, periodic variations, and slowly varying trends.

The processing procedure first applies wavelet filtering to the strain data after temperature correction and outlier removal in order to suppress high-frequency noise interference from the construction process. The wavelet filtering is carried out using a mother wavelet with compact support and good orthogonality (such as Daubechies wavelets of order 4 to 6) for multi-scale decomposition. After the decomposition is completed, only the approximation part at the final level is retained for signal reconstruction, thereby obtaining a filtered and stationary signal sequence. For an original signal

decomposed into

j levels, the expression is:

where

is the approximation component at the

j-th level, and

is the detail component at the

i-th level. In the reconstruction process, usually only

is retained as the denoised result to obtain the stationary signal sequence after filtering.

Subsequently, the filtered signal is processed using the empirical mode decomposition algorithm. The EMD method decomposes the signal

based on its local characteristics, representing it as the sum of several intrinsic mode functions (IMFs) and a residual term

:

Each IMF component must satisfy the following two mathematical conditions: (1) over the entire time domain, the difference between the number of extrema and the number of zero-crossings does not exceed one; (2) at any point in time, the mean value of the upper and lower envelopes is zero. The extraction of IMFs is carried out by interpolating the local extrema to construct the upper and lower envelopes, calculating their mean, and iteratively sifting until the extracted component no longer meets the above conditions.

2.4. Index Extraction and Quantitative Evaluation

After completing the modal decomposition, key time-domain characteristic parameters are extracted from each IMF component and the residual term to enable subsequent classification, identification, and quantitative analysis of disturbance types. These parameters reflect the differences in time span, intensity level, and frequency characteristics of each modal response and mainly include peak-to-peak amplitude, dominant period, effective duration, and rate of change.

The peak-to-peak amplitude

represents the amplitude between the maximum and minimum values in each modal signal, calculated as:

where

is the

k-th IMF component. This parameter reflects the instantaneous intensity of a disturbance and is the primary basis for identifying construction events such as prestressing and concrete casting.

The dominant period

is estimated from the average interval between consecutive zero-crossing points in the signal and is defined as:

where

is the time of the

i-th zero-crossing, and

is the total number of zero-crossings in the k-th IMF. The dominant period reflects the frequency characteristics of the signal and is used to identify periodic disturbances caused by solar temperature variation.

The effective duration

measures the time interval in which a modal signal exhibits a significant response in the time domain. This parameter is determined by setting a relative amplitude threshold to identify the start and end times:

where

δ∈(0, 1) is the relative threshold coefficient, set to

δ = 0.1∼0.2 to filter out background disturbances and noise components.

In addition, for certain slowly varying modes (such as the residual term or low-order IMF components), the rate of change

is evaluated to quantify strain accumulation behavior:

The rate of change can be approximated using the first-order difference and is used to identify stress development trends during material evolution processes such as shrinkage and creep.

All indicators are extracted using custom MATLAB (2025) scripts. The extracted results are used to construct a modal classification matrix and serve as input for subsequent disturbance source identification, amplitude statistics, and impact analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Stage-Specific Strain Characteristics at an Early Age

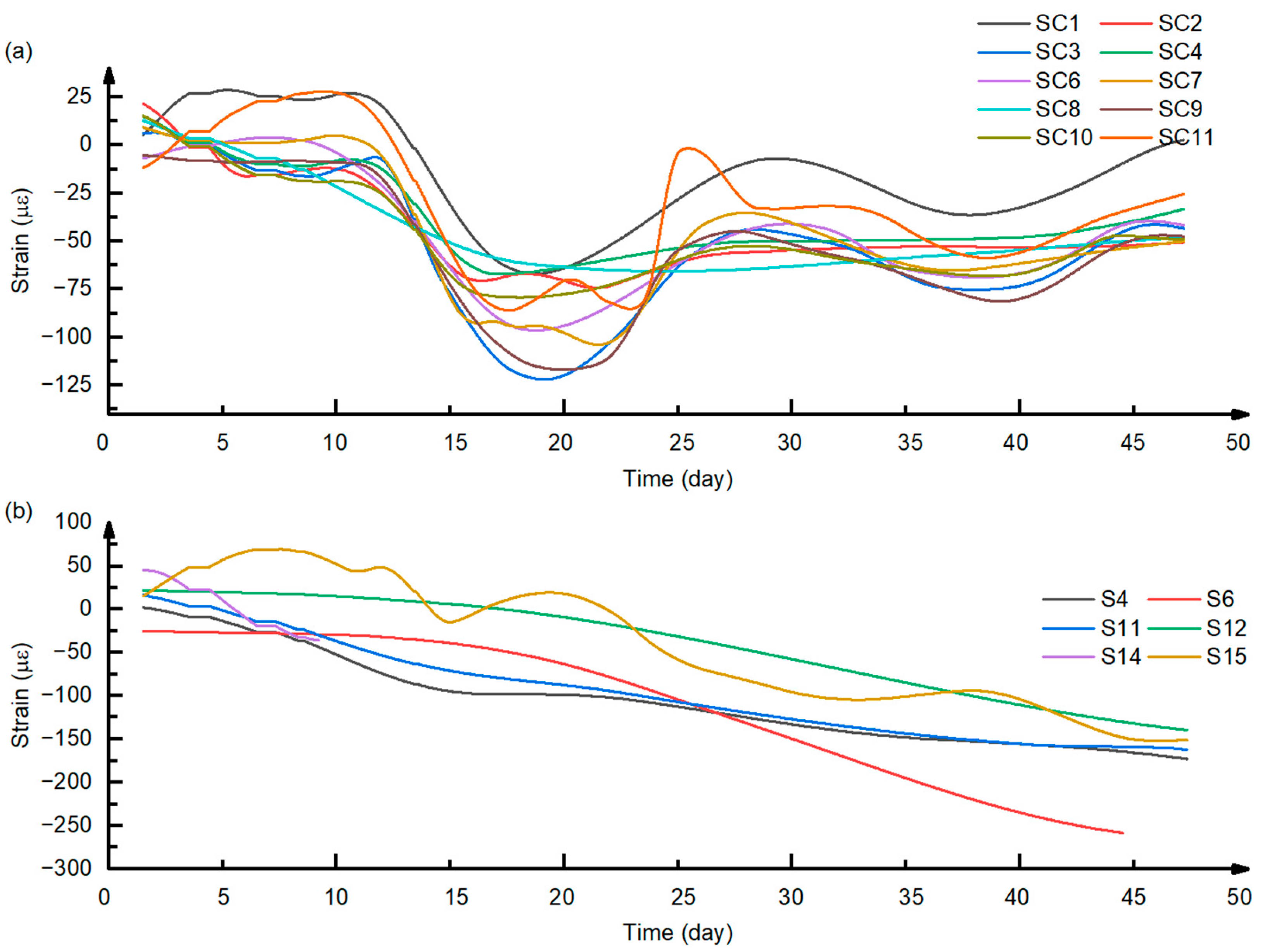

Figure 3 presents the time-history results of concrete and steel girder strains after temperature correction, covering the monitoring period from the start of casting of the cast-in-place segment in the negative moment region to the end of the construction stage.

Figure 4a shows the measured temperature curve of the concrete, indicating distinct diurnal temperature fluctuations during the monitoring period, with a large difference between the maximum and minimum values and an overall gradual decrease in temperature over time.

Figure 3b,c show the strain curves of the concrete and the steel box girder, respectively. After correcting for the difference in linear expansion coefficients, the systematic error caused by the mismatch in thermal expansion between the steel string and the concrete was eliminated, allowing the curves to reflect the true deformation process of the materials and the structure.

From the strain time histories, it can be observed that within a few hours after casting, the concrete strain increased rapidly by about 10–25 με, corresponding to the volumetric expansion stage caused by the combined effects of hydration heat and expansive agents. In the following 24–48 h, the strain decreased rapidly, with a shrinkage magnitude of about 5–25 με, corresponding to early-stage plastic shrinkage and hardening shrinkage. After the second day of age, the strain gradually increased again, with an amplitude of 20–50 με, indicating that the micro-expansion effect partially offset the previous shrinkage. Significant differences in strain amplitude were observed among different measurement points: positions with stronger steel girder restraint exhibited relatively smaller fluctuations, while those with weaker restraint showed larger fluctuations.

3.2. Effect of Construction Processes on Strain

Figure 4 shows the detailed strain time histories of the cast-in-place segment in the negative moment region during the construction process, and

Table 1 lists the key construction events and corresponding dates. During the monitoring period, the strain curves exhibited abrupt changes at several construction nodes, mainly corresponding to operations such as concrete casting, prestressing, and the construction of adjacent cast-in-place segments.

The first prestressing (10 December 2021) caused a significant decrease in concrete strain, with an average change magnitude of about 80–100 με, and this effect was most pronounced within 24 h after tensioning. The second prestressing (27 December 2021) resulted in a much smaller strain decrease of 20–40 με, with a shorter duration.

In addition to the construction of the monitored segment, the casting and prestressing of adjacent segments also affected the monitored section. As shown in

Figure 5, the strain exhibited a recovery phenomenon at these events, with an amplitude increase of about 30–80 με. The closer the construction segment was to the monitored section, the greater the magnitude and the longer the duration of the influence. This indicates that construction disturbances are not limited to the segment under construction but can be transmitted through the structure to affect the stress state of adjacent segments.

Figure 5 illustrates the shrinkage and expansion process during the early stage after casting. On the first day after casting, the heat of hydration caused the strain to increase by 20–30 με. After the final setting, the temperature drop led to a strain decrease to about −25 to −5 με. Subsequently, under the combined effects of the expansive agent and the temperature rise, the strain gradually increased by 20–50 με before eventually stabilizing. This process indicates that the volumetric changes of the material itself, intertwined with the loading and unloading processes of construction operations, constitute the main characteristics of strain variation in the early stage.

3.3. Strain Response Under Variable Load Conditions

Figure 6 shows the strain response characteristics of the concrete and steel girder under daily cyclic temperature variations after the concrete strength reached the design requirement. It can be observed that the strain curves exhibit regular upward and downward fluctuations, which are closely related to the restraint conditions at each measurement point.

For concrete measurement points in direct contact with and restrained by the steel girder top flange (e.g., SC2, SC4, SC6, SC8, SC10), the fluctuation amplitude was relatively small, about 10 με. For measurement points not in direct contact with the top flange (e.g., SC1, SC3, SC7, SC11), the fluctuation amplitude was larger, reaching up to 40 με.

The steel girder measurement points also showed significant differences: those located at the web of the top flange (e.g., S4, S6, S10) had fluctuation amplitudes of about 20 με, whereas those located at the bottom flange (e.g., S14, S15, S16) had amplitudes up to 150 με. This difference indicates that, within a composite section, the degree of mutual restraint between the steel girder and the concrete directly affects the strain amplitude under temperature loading.

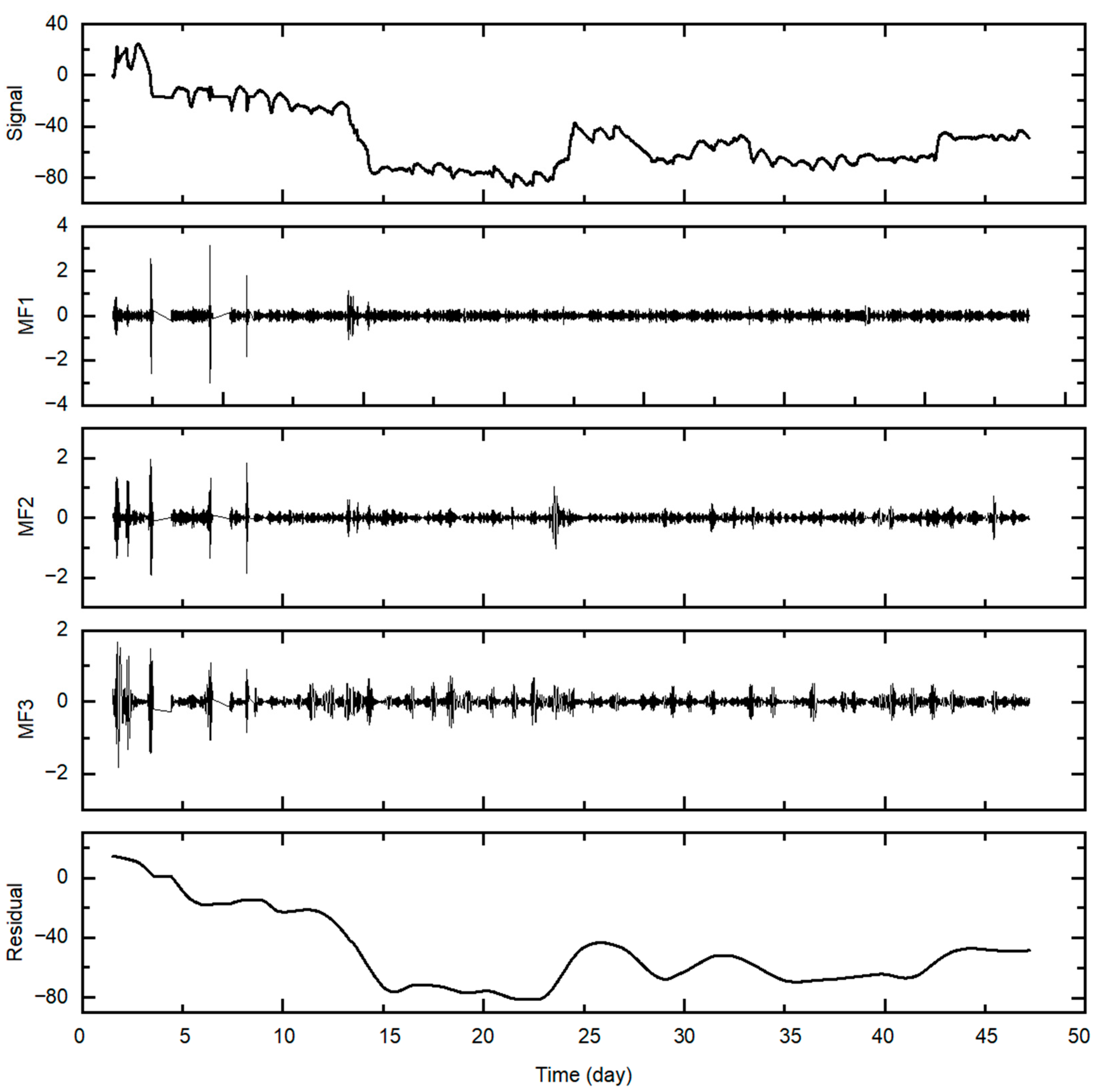

Figure 7 shows the modal components obtained by applying EMD to the strain signals after outlier removal and wavelet filtering. The high-frequency components mainly reflect short-term random disturbances and local construction effects, while the medium- and low-frequency components are associated with daily cyclic temperature variations. After removing the temperature influence, the residual signal can clearly reveal the long-term trend changes caused by concrete autogenous shrinkage and construction operations.

Figure 8 shows the processed results obtained after outlier removal, wavelet filtering, and EMD, used for analyzing the non-temperature components after removing the daily cyclic temperature effects. From the processed concrete channel data, the strain generally exhibits a staged pattern of “increase–decrease–increase–decrease–increase”: the first and second “decrease” stages correspond to the two prestressing operations, with shrinkage values of approximately 80–100 με and 20–40 με within 24 h, respectively; the two “increase” stages correspond to tensile stress effects caused by the construction of adjacent cast-in-place segments, with amplitudes of about 60–80 με and 30–40 με, respectively.

The processed results of the steel girder channels generally show compression, with a compression magnitude of about 180–200 με. Only a few locations changed from compression to tension after the first prestressing, indicating that slip may have occurred at the steel–concrete interface during prestressing, thereby altering the interface stress relationship.

4. Discussion

This study aims to address the multi-source disturbances in the strain evolution process of concrete structures during the construction stage by proposing a multi-modal strain identification method based on full-scale bridge monitoring. The method is intended to reveal the stress variation characteristics and dominant influencing factors of structure components at various stages. Unlike conventional parameter identification under steady-state conditions, early-age concrete during construction is in a non-steady process of rapid growth in mechanical properties, with strength and elastic modulus changing significantly over time. This makes the extraction of signal features and the quantification of parameters considerably challenging. In addition, temperature variations and construction disturbances often overlap in the time domain, and their rates of change and amplitudes differ significantly. Therefore, wavelet filtering and EMD techniques are combined to separate strain components from different sources, while construction logs are used to perform qualitative–quantitative analyses of the trends and amplitudes of known disturbances. This approach ensures that the main influencing factors can still be extracted under non-steady conditions and allows for mechanism comparisons across structural components and construction stages.

At the early-age stage, the cast-in-place segment in the negative moment region exhibited a distinct shrinkage–recovery process (see

Figure 5), with the variation trends jointly influenced by hydration shrinkage, volumetric compensation from the expansive agent, and temperature changes. For the cast-in-place segment in the negative moment region, the early shrinkage amplitude was relatively large, and the recovery process was slower, generally stabilizing within several days to a week. The strain difference between the upper and lower edges was relatively small, indicating that the restraint conditions in this region were more uniform and the concrete was subjected to relatively consistent overall stresses at the early stage.

Figure 9 illustrates the strain distribution characteristics of the concrete deck under two typical stress states: during the early shrinkage stage, both the upper and lower edges were in tension, reflecting the isotropic effect of the overall volume reduction of the concrete; when a temperature gradient or overall structural bending occurred, the strain directions at the upper and lower edges were opposite—either with the upper edge in tension and the lower edge in compression, or vice versa. This change in state explains why the shrinkage amplitude at the upper edge was slightly greater than that at the lower edge. Overall, the strain evolution of the cast-in-place segment in the negative moment region during the early-age stage was more influenced by the overall structural stiffness and restraint conditions.

During the construction procedure stage, the strain evolution of structures was significantly affected by external loading disturbances (see

Figure 4). For the cast-in-place segment in the negative moment region, the main influences came from prestressing and the construction of adjacent cast-in-place segments. The first prestressing operation caused a pronounced shrinkage at the monitoring points, with strain amplitudes reaching several times the magnitude of early-age self-deformation. The amplitude of the second prestressing was smaller than the first, reflecting that as the concrete strength and stiffness increased, the strain response of the structure to externally applied prestressing became weaker. In addition, local tensile strain recovery effects caused by the construction of adjacent cast-in-place segments were significant at measurement points near the construction area and decayed rapidly with increasing distance. This indicates that prestressing disturbances and local concrete casting acted together to produce short-term strain recovery. The cast-in-place segment in the negative moment region exhibited a “pulse-type” strain variation during the construction procedure stage, producing significant peaks during prestressing and local construction.

During the variable load stage, the strain variations of structures were influenced by the combined effects of daily cyclic temperature fluctuations and occasional live loads (see

Figure 6). In terms of temperature fluctuation characteristics, the strain amplitude difference between the upper and lower edges of the cast-in-place segment in the negative moment region was relatively small, generally showing a mode of overall synchronous contraction or expansion with temperature. This response suggests that its stress state was largely governed by overall structural stiffness, with insignificant temperature gradient effects.

To further clarify the signal sources, the modal decomposition results (

Figure 7) show that the high-frequency components (IMF1–IMF3) correspond to short-term construction and live-load disturbances, whereas the low-frequency residual reflects the long-term temperature- and shrinkage-induced strain evolution. This indicates that periodic temperature variations dominate the overall trend, while live-load responses remain weak and transient.

Regarding live load effects, short-term strain fluctuations caused by vehicle loads were detected in the long-term monitoring of the structure, but the amplitude was generally small. The cast-in-place segment in the negative moment region, being farther from direct load paths and having a more complex load transfer mechanism, showed a greatly attenuated direct response to live loads. In terms of long-term trends, after removing the temperature component, the residual signal of the cast-in-place segment in the negative moment region reflected a combined effect of shrinkage and construction disturbances, with its long-term strain gradually declining.

In summary, the response of the cast-in-place segment in the negative moment region during the variable load stage was closer to an overall thermal expansion–contraction mode. Based on the monitoring results and signal processing analysis (see

Figure 8), the total strain during the construction and operation stages can be uniformly decomposed into the following components:

Here, and represent material shrinkage and the volumetric compensation produced by the expansive agent, respectively; represents the effect of daily cyclic temperature variation; refers to live load effects during the construction or operation stage; denotes secondary dead load effects (such as paving); and represents random disturbances.

Comparative analysis shows that, in the cast-in-place segment of the negative moment region, the proportions of and are relatively high, indicating greater sensitivity to live loads and overall thermal expansion–contraction.

In summary, the multi-modal strain identification method based on full-scale bridge monitoring can effectively address the challenges of signal separation and cause identification for concrete structures under non-steady conditions during the construction stage. The key to the method lies in using wavelet filtering to remove high-frequency noise, combining EMD to extract characteristic components such as temperature effects, construction disturbances, and live loads, and constraining the analysis of time-series correspondence through construction logs, thereby enabling both component-based and mechanism-based interpretation of strain evolution in different locations. This method not only provides a reliable basis for stress monitoring and quality control during construction but also lays the foundation in terms of data and modeling for long-term performance prediction and the optimization of operation and maintenance strategies.

5. Conclusions

Based on full-scale bridge monitoring data, this study proposes and validates a multi-modal strain identification method applicable to concrete structures during the construction stage. By separating the response characteristics of early-age effects, construction disturbances, and variable loads, the method quantitatively reveals the stress-evolution patterns of key structural components. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

At the early-age stage, the concrete strain first increased by approximately 10–25 µε due to hydration expansion, then decreased by 5–25 µε during plastic and autogenous shrinkage, and finally recovered by 20–50 µε under the compensating effect of the expansive agent. The overall fluctuation amplitude reached about 50–80 µε, and measurement points with stronger girder restraint exhibited smaller variations than those with weaker restraint.

- (2)

During the construction procedure stage, strain variations were dominated by prestressing and the sequential casting of adjacent segments. The first prestressing caused a strain drop of 80–100 µε, while the second induced a smaller decrease of 20–40 µε. Construction of nearby segments produced strain recoveries of 30–80 µε, whose magnitude and duration decreased with distance from the active segment.

- (3)

Under variable load and thermal effects, the deck exhibited regular cyclic strain responses. Concrete points directly restrained by the steel girder fluctuated by only ≈10 µε, whereas less-restrained points reached ≈40 µε. For the steel girder, the amplitude ranged from 20 µε at the web to 150 µε at the bottom flange, indicating strong stiffness-related differences across the composite section.

- (4)

After removing the temperature component, the two major shrinkage stages (≈80–100 µε and 20–40 µε) and the two recovery stages (≈60–80 µε and 30–40 µε) were clearly identified. The steel girder mainly experienced compression of about 180–200 µε. Strain-component analysis showed that temperature and dead-load effects contributed roughly 60–70% of the total long-term strain, while live-load-related effects accounted for 25–30%, and short-term construction disturbances less than 10%.

- (5)

The proposed method and quantitative findings provide a solid engineering-oriented framework for strain monitoring, disturbance identification, and stress-evolution assessment of concrete bridge structures during construction. The approach can be extended to large-span composite decks and segmental bridges to support early-age performance evaluation and construction-stage safety control.

Beyond the present findings, this study offers meaningful prospects for both scientific advancement and engineering practice. From a scientific viewpoint, the proposed multi-modal strain identification framework can be integrated with advanced signal analysis and numerical simulation methods to establish a more comprehensive understanding of multi-scale stress evolution in early-age concrete. From an engineering standpoint, applying this approach to digital construction and real-time monitoring of large-span bridges can greatly enhance the accuracy of stress evaluation and safety control during the construction stage, thereby supporting long-term durability management and maintenance planning.