1. Introduction

This study represents the first pilot research on the relationship between the use of wood in tourist infrastructure and interiors designed primarily for visitors and the clients’ perception, recognition, and the overall quality of the tourist experience. It serves to provide an overview of the issue of responsible tourism and to identify the main terms and main connections between human perception, materials, specifically wood, and the tourist experience. It is part of the Tourism Design project, which loosely follows on from the Identity SK project and the project Interaction of Man and Wood of the Faculty of Architecture and Design, Slovak University of Technology in Bratislava. The contemporary tourism project aims to support regional development through research and development, the creation of implementation methodologies, the strengthening of local communities in the creation of community tourism, and the construction of ecological tourism infrastructure.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Tourist Experience

What is the main purpose of a trip or holiday? The effect–recovery theory and the conservation of resources theory suggest that taking a leisure trip provides opportunities for relaxation, detachment from work, mastery experience, and personal control. This research examined the role of tourism experiences as a stress reliever, particularly focusing on the underlying psychological experiences associated with recovery [

1].

Experiencing a place during leisure or tourism differs fundamentally from everyday functional usages. Vacations and short-term stays are among the most valued forms of self-care and emotional well-being [

2]. As visitors select destinations for rest and restoration, a complex interplay of practical and symbolic factors shapes their decision—among them, the material environment.

Recent findings from cognitive psychology, cognitive science, and neuroscience provide the basis for a better understanding of the origin of a memorable experience and psychological aspects of tourism experiences such as attention, emotion, memory, and mindfulness.

The basic stages of the tourist experience include the following:

- -

Pre-stage experience: customer inputs such as knowledge, myths, values, and memories from previous travel;

- -

On-site experience: co-creation processes;

- -

Post-stage experience: immediate and long-term outcomes, including happiness and well-being [

3].

In all the stages, the quality of a built environment and its presentation and processing form a substantial part of the tourist experience.

More insight into the understanding of the tourist experience is given by cognitive appraisal theory, which has contributed to defining the memorable tourism experience (MTE), which in a simplified form could be described as a travel memory that a tourist recalls positively and values after their trip has ended, influencing their future decisions and behaviors [

4].

Cognitive appraisal theory posits that emotions arise from how individuals subjectively evaluate their surroundings [

5].

In tourism, this means that visitors’ feelings—whether comfort, inspiration, stress, or disappointment—depend not only on physical stimuli like lighting or textures, but also on how authentic, safe, or meaningful a space feels. An authentic wooden interior, for example, may evoke warmth and belonging for some, yet feel outdated or unclean to others. These differences are caused not only by personal context, but also by the cultural background of the users.

Tourist experience (TX) is understood to be the tourists’ interactions with and responses to the products, systems, and services provided by the organizations they engage with before, during, and after their trip, which significantly impact their experience and thus their satisfaction and loyalty. A consideration of cultural factors allows us to understand how the values and beliefs of tourists in selecting their destinations relate to and affect TX. Tourists’ experiences are influenced by their own characteristics, their travel companions, the service providers, and the environment. Therefore, in this case, personal and contextual elements influence 50% of the TX, and it is the tourist destination’s job to enhance and apply improvement strategies so that tourists positively perceive cultural interactions according to their culture of origin [

6,

7].

2.2. Role of Biophilic Design in Touristic Experience

Material ambiance has emerged as a key dimension of the destination image and attractiveness. Visitors are not only influenced by location or cost, but by sensory elements that convey comfort, identity, and care. These material qualities are especially valued in eco-tourism, wellness, and heritage settings, where the perceived naturalness of an environment supports longer stays and repeat visits [

8,

9].

Moreover, memorable tourism experiences often emerge from such appraisals when environments engender novelty, relevance, and emotional resonance [

10], while transformative experiences hinge on deeper shifts in perception [

11], generating tourists’ willingness to stay longer whereas the length of stay (LOS) as a critical variable in tourism planning and management is a vital element and one of the most essential decision-making variables for tourists, as it significantly impacts the host society and the economy of tourist destinations [

12,

13].

When tourists cognitively appraise these environments positively, the experience can become both memorable and transformative.

In the memorable tourism experience study of Hosany et al., tourism experiences have been defined as enjoyable, memorable, and engaging encounters and as transitory phenomena. Tourists seek authentic, rewarding, meaningful, multisensory, and transformative experiences when visiting places [

10].

Stress and coping strategies during a tourist’s experience in leisure travel were explored and defined. The study defines the four major types of stress (i.e., service-provider-related stress, traveler-related stress, travel-partner-related stress, and environment-related stress) encountered during their vacations and the many strategies (i.e., problem-focused and emotion-focused coping) employed to cope with stress [

7].

Biophilic design and restorative environment design thus have their strong positions, based on environmental, evolutionary, and cognitive psychology theories, which support such an improvement strategy for minimizing and relieving the stress of visitors/travelers.

Integrating biophilic design, especially through the use of natural materials such as wood, stone, and clay, contributes to a biophilic experience in tourism and hospitality architecture that can be (multi) stimulating or calming.

Wood specifically enhances these qualities: wood surfaces convey authenticity and ecological alignment, supporting stress reduction [

14], emotional restoration, increased environmental satisfaction, and emotional well-being [

15,

16,

17].

Biophilic design theory posits that humans possess an inherent affinity to nature and natural elements in a built environment [

16]. Wood, as a living and multisensory material with visible grain, scent, and tactile irregularities, plays a central role in evoking this connection.

2.3. Wood and Touristic Experience

The relevance of wood as a sensory and emotionally resonant material in tourism architecture builds on earlier research by the first author listed above. Initial investigations into the physiological and psychological impact of wooden environments were developed during a research fellowship at BOKU Vienna in 2011 in collaboration with Prof. Alfred Teischinger. These ideas were later expanded through the national research project Interaction of Man and Wood (APVV 2013–2017), which systematically explored how human contact with wooden surfaces influences comfort, stress perception, and affective evaluations.

A substantial part of this research was first presented at the international SWST conference in Zvolen and further elaborated in studies on contact comfort [

18,

19]. These works emphasized that tactile engagement with natural materials such as wood can reduce physiological arousal, promote emotional comfort, and support perceived environmental quality—findings that are mirrored in the growing literature on biophilia and sensory architecture.

The main findings of these research studies were that wood, with its natural and emotional impact through visual, tactile, and olfactory interaction, objectively contains the positive properties of a healthy microclimate, such as greater contact comfort, improvement of room acoustics, regulation of air humidity in a space, reduction in VOC (volatile organic compound) emissions (“sink effect”), and antimicrobial properties due to the absence of surface treatment with all kinds of surface finishing, e.g., oil, wax, or varnish. Unfortunately, without them, wood is in a more extensive way prone to surface defects and irregular patina due to wear and obsolesces, and wet maintenance with chemical detergents is crucial [

20].

Contact comfort consists of a combination of balanced surface temperature, heat transmission, surface roughness, surface elasticity/hardness, surface sorption activity in terms of vapor/fluid absorbance (which has an impact on overall indoor air humidity), sorption activity of the surface in terms of absorbing external moisture (e.g., sweat or humidity of air/its condensates), control over body position, possibilities of maintenance, and visual comfort connected with the cultural background of the users, individual mental and physical settings that create overall feelings of comfort. All these parameters are measurable, and it is possible to optimize them with the aim of obtaining good solutions that provide higher contact comfort [

18,

19].

What kinds of experiences are offered by wood in different forms when used in structures, solid wood elements, or wood-based materials?

2.4. Sensory Perception—Multisensory Potential of Wood

Responses to wood are typically multisensory: the warmth and texture of untreated timber, its smell, and its sound-absorbing properties contribute to a holistic sensory experience. These qualities are particularly valued in recreational and tourism architecture, where users seek calm, immersion, and sensory richness as part of their experience.

Experimental studies have demonstrated that visual or even tactile exposure to real wood surfaces reduces stress and increase physiological beneficial markers. For instance, touching coated wood increased parasympathetic nervous activity [

15], while viewing full-scale wooden interiors lowered autonomic stress indicators like blood pressure and heart rate variability [

21].

As part of biophilic design, wood enhances visual warmth, aids stress recovery, and evokes symbolic meaning [

13,

22,

23].

The results of tests indicated a higher heart rate variability in a wooden room compared to the reference room. Participants breathed about one breath per minute less in the wooden room, with a negative correlation between heart rate variability and respiratory rate. A positive affect was elevated, and negative affect was reduced in the wooden room, which was also perceived more favorably in sensory evaluations. The findings suggest that wooden interiors are preferred over artificial materials, enhancing both physiological and psychological well-being [

24].

Moreover, Terrapin Bright Green (2024) argue that wood “provides a tactile and visual connection to nature”, reinforcing the restorative effects associated with natural environments. The authors suggest that wooden interiors foster not only relaxation but also an improved cognitive performance and affective balance. Public and recreational spaces also benefit from biophilic strategies that include wood as a key material [

25]. According to HDR (2024), “biophilic design in public architecture nurtures our innate connection with nature, promoting mental restoration and social engagement” [

26].

2.5. Materiality and Authenticity

(Sensorial) materiality—the interplay of the tactile, visual, and symbolic qualities of materials—plays a pivotal role in shaping user perception in tourism and recreational architecture. Theories by Böhme (1993), Zumthor (2006), and Pallasmaa (2005) emphasize the affective role of materials in creating immersive atmospheres. Timber operates as both medium and message—guiding behavior, enabling reflection, and reinforcing the narrative of place [

27,

28,

29].

Authenticity remains one of the most debated and desired qualities in tourism architecture. In hospitality and cultural tourism, material authenticity—defined by the visible presence of “real”, locally relevant, or historically resonant materials—is often linked to a sense of place, emotional engagement, and visitor satisfaction [

30,

31].

There is an arguing that authenticity functions both as a theoretical concept and an empirical user response. In practice, visitors describe authentic spaces as those that feel real, often referring to materials like aged wood, hand-made surfaces, or vernacular textures. Wood, particularly when allowed to age or retain visible imperfections, reinforces this perception through patina, wear, and symbolic durability [

32].

2.6. Hygiene, Surface Maintenance, Operational Life, and Material Trust

Despite its aesthetic and symbolic appeal, wood remains controversial in public design due to concerns about its lower operational life, maintenance, and hygiene. Untreated or visibly worn wooden surfaces may trigger perceptions of contamination, roughness, or lack of care—especially in environments where cleanliness is prioritized, such as restaurants, wellness facilities, or hotels.

Research on the antibacterial properties of wood [

20,

33,

34], suggests that certain species have inherent hygienic advantages, particularly when properly maintained. Our measurements of the microbial quality of air and surfaces in a laboratory and on the wooden surfaces of a waiting room at the National Oncological Institute in Bratislava show that oak, pine, and larch show a high antimicrobial activity when untreated [

20].

However, public perception rarely aligns with microbial data. Users often rely on visual cleanliness—smoothness, gloss, and absence of discoloration—as proxies for hygiene, favoring coated or synthetic materials.

In tourism environments with high visitor turnovers, the perceived maintainability of wood becomes a central factor in design decisions. Surface treatments such as hardwax oil or UV-cured coatings can balance natural expressiveness with cleanability. However, when aging is not communicated as intentional design, it may erode trust or suggest neglect.

This tension reveals a deeper cultural dilemma: wood is emotionally valued for its authenticity and naturalness, but in tourism these very features may conflict with norms of order, hygiene, and operational efficiency. As a result, wood is often replaced by imitative laminates or plastics—materials that appear “cleaner” despite lower sensory or ecological values.

Further evidence comes from the WOOD LCC project [

35], which investigated the life cycle cost and long-term user perception of wooden materials in high-traffic environments. The project highlighted the ways in which durability, surface aging, and visible maintenance significantly affect how wood is accepted or rejected by users. These insights are especially relevant in tourism and recreational settings, where the aesthetic value of wood must align with expectations of cleanliness, safety, and upkeep.

In the past decades, user preferences were explored in relation to wood surfaces. What is a superb wood surface? In order to define user preferences and service life expectations [

36] and the perceived quality of wooden building materials, a systematic literature review and future research agenda are necessary [

37].

Within the WOOD LCC project, several studies were executed considering a range of factors, including design, material properties, location, maintenance, and use intensity, to deliver holistic LCC estimates. Consumer perceptions of uncoated wooden cladding were explored across three European countries: Germany, Sweden, and Norway. Using an online survey with 3112 participants, the study found that the preference for uncoated wooden cladding was similar (around 20%) across the three countries, despite differences in the prevalence of wooden cladding. These findings highlight that consumers’ perceptions of the aesthetic qualities of wood, including its natural discoloration over time, are influenced not only by functional aspects but also by psychological and cultural dimensions. By connecting consumer preferences to practical applications for uncoated wooden materials, this study contributes to advancing wood utilization in construction, offering valuable insights to manufacturers, builders, and policymakers regarding potential market acceptance [

38].

Our previous research [

20] demonstrated that the presence of natural wood elements without finishing in interior environments—specifically in healthcare settings—has measurable positive effects on users’ physiological and emotional responses, including measurable amazement—the “WAW experience”—on entering the space. The study found that wooden surfaces contribute to an improved perception of environmental quality, reduced stress levels, and enhanced emotional comfort. These outcomes provide strong empirical support for biophilic design theory and validate the role of wood in high-stakes public environments.

Also tested were different methods of cleaning (disinfecting) the surfaces of larch and pine wood without finishing, wherein the use of ethanol (technical alcohol) was more effective than a detergent on a chlorine basis.

Although the original context was medical, the findings translate directly into tourism and wellness architecture. Just as patients and medical staff benefit from psychologically supportive and non-institutional spatial qualities, visitors to recreational or hospitality interiors may respond positively to warm, natural materials that communicate safety, care, and authenticity.

However, when such materials are deployed in tourism settings, their visual and hygienic acceptability becomes critical. In shared or high-turnover environments, natural surfaces must not only evoke positive affective responses but also meet practical requirements for cleanliness, durability, and trust.

This intersection—between perceived well-being and surface “legibility”—highlights a broader challenge in sustainable tourism: how to balance “ecological symbolism” and multisensory comfort with hygienic and operational expectations. It also frames the motivation for our second pilot study, which focuses on physiological measurements of contact with natural and synthetic wood surfaces in tourism-related contexts.

2.7. Materiality in Built Environments for Visitors and Tourists

Timber used in façades and cladding carries symbolic, sensorial, and ecological weight. As the first visible layer of a recreational or hospitality building, wooden façades contribute to initial impressions of place identity and environmental values.

Studies highlight that well-detailed timber claddings—e.g., ventilated rain screens or modular panels—can achieve dignified weathering while maintaining visual and tactile appeal [

39]. Selected case studies on buildings from diverse locations are also subsequently presented in the publication Bio-based Building Skin [

39] to demonstrate the successful implementation of various biomaterial solutions, creating unique architectural styles and building functions, and at the same time providing welcome biophilic experiences in built environments for visitors and tourists, at every level of the touristic experience.

In visitor centers—particularly those linked to nature, culture, or heritage—the use of timber enhances orientation, inclusivity, and symbolic engagement [

40]. Wood surfaces thus could improve attention, warmth perception, and the desire to linger. Cohen’s notion of “staged authenticity” reinforces the idea that natural wood surfaces can act as cultural mediators. Their texture, grain, and tone evoke historical continuity and local identity, which in turn shape emotional memory and interpretive depth [

41].

Hospitality environments such as cafés, restaurants, and boutique hotels provide longer interactions with interior materials. Here, timber contributes to emotional resonance, spatial memory, and atmospheric comfort. Research shows that wooden interiors are perceived as more welcoming, trustworthy, and calming [

42,

43,

44].

However, the beneficial effects of wood are context-dependent. Factors such as the surface treatment, degree of exposure, and perceived lack of cleanliness can modulate or even undermine the intended biophilic impact [

44].

2.8. Sustainability and Regional Development in Context of Tourism

Tourism is a strategic sector that supports regional development and the welfare of the local community. However, tourism development practices still need to improve, primarily in relation to implementing comprehensive strategic planning [

45]. This includes work opportunities in regions with low employment, empowering communities (in cases of community-based tourism), and the implementation of local renewable materials and technologies with low environmental footprints.

To have lower negative impacts on the environmental footprint, it is suitable to use local renewable materials and techniques for building infrastructures for tourists and visitors, as is common with tourist infrastructure, for example in the Vorarlberg region of Austria (

Figure 1).

Today’s climate crises provoke necessary transitions toward a sustainable green economy [

46], especially in the building industry. Wood, as a local renewable material used in traditional techniques and smart progressive technologies, offers a wide palette of solutions.

As a low-carbon, renewable material, wood aligns well with sustainability goals. Throughout its life cycle, it has a negative carbon balance: it absorbs CO

2, stores carbon, and requires less energy for extraction and processing than most conventional materials [

47]. Wood waste is minimal and can be fully reused or converted into energy. It is durable, biodegradable, recyclable, and suitable for cascading use.

However, wood faces increasing competition from synthetic substitutes that often imitate its appearance. These artificial substitutes originate in the chemical industry and, during their life cycle, create an incomparably higher environmental burden than natural structural timber and large-area materials based on solid wood.

The synthetic painting/coating/finishing of wooden surfaces also causes environmental problems during the whole life cycle. There are estimations that paints are 37% plastic on average and that paint microplastics contain greater additive contents [

48]. This raises the question of the necessity of using these paints. On the one hand, paints do prolong the life span of an infrastructure, but on the other hand they cause environmental problems.

Wood is also ideal for low-energy buildings, where it supports a healthy indoor environment, contributing positively to both mental and physical well-being.

So, in addition to its sustainability credentials, it continues to symbolize quality and contribute to human well-being. Its application in creating infrastructures for visitors/tourists can increase the attractiveness (WAW effect) and contribute to the memorability of the experience and thus the willingness to pay more, prolong the stay, or repeat the visit.

The WOOD LCC project has shown that the life cycle aspects of wood—including wear, aging, and visible maintenance—also play a central role in shaping user trust [

35]. While natural materials can support emotional and environmental quality, their long-term acceptance depends on the visibility of care/maintenance and the clarity of custodianship. This is particularly true in semi-public or hospitality settings, where users are sensitive to hygiene, wear, and symbolic cues of maintenance.

The question is what symbolic value these facts have, how they are communicated to the public, and their importance for choices of destinations for trips or holidays, or for choices of accommodation, gastronomy services, and attractions.

3. Materials and Methods

This study follows a mixed-methods approach to explore how timber is perceived in recreational and semi-public interior environments. Specifically, we examine both subjective evaluations (via a questionnaire) and objective physiological reactions (via sensor-based monitoring). The methodology comprises three parts:

3.1. Research Aim and Hypotheses

The central aim of this research is to analyze the theoretical background (framework) of the topic of perception of natural material, especially wood, in recreational areas, and to assess how users perceive and experience natural wood surfaces in public or tourism-oriented environments. The study focuses on five interrelated themes:

Tourist experience;

Emotional and sensory comfort;

Perception of hygiene and cleanliness;

Symbolic and cultural associations;

Material sustainability and maintenance trade-offs.

Main Hypothesis (H1)

H1. Users exposed to natural wood surfaces in tourism-related spaces perceive these environments as more emotionally supportive, aesthetically pleasant, and environmentally responsible than those without visible natural materials.

Sub-hypothesis 1

H1-1. An environment predestined for recreation and regeneration is even more sensitive to the authenticity and naturalness of surfaces and the overall appearance.

Sub-question 1

How do context, user background, and surface treatment influence this perception?

Sub-question 2

What makes the tourist experience different from the perspective of users in working environments, institutional buildings, or housing?

3.2. Study 1: Visitor Questionnaire

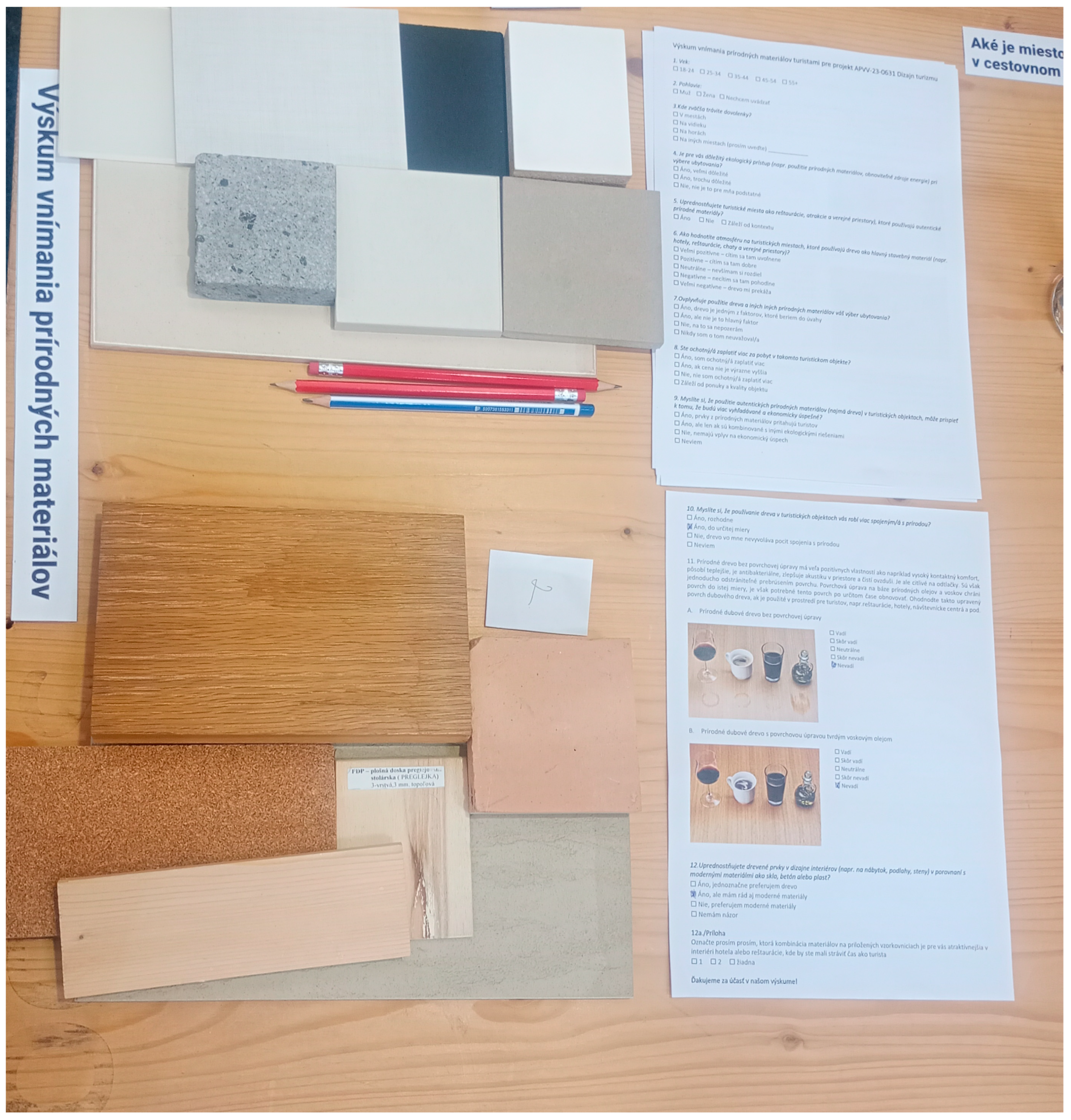

A structured questionnaire with 12 questions was distributed to 37 participants at the CONECO building industry fair in Bratislava in April 2025. The survey included demographic profiling, questions about user preferences for natural materials in tourism in indoor and outdoor spaces, hotels, and restaurants, the perception of hygiene and comfort, the willingness to pay more for authentic experience, and the visual surface treatments preferences. The responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

3.3. Study 2: Physiological Response Experiment

In cooperation with the Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Information Technology at STU, an exploratory physiological experiment was conducted. Eleven participants were exposed to three material surfaces—solid oak, chipboard, and white laminate—under three sensory conditions (visual, tactile, and combined exposure).

EEG, ECG, and respiration monitoring were used to record data on neural activity, heart rate variability, and respiratory depth. The aim was to identify correlations between material exposure and physiological states associated with stress, attention, or calmness.

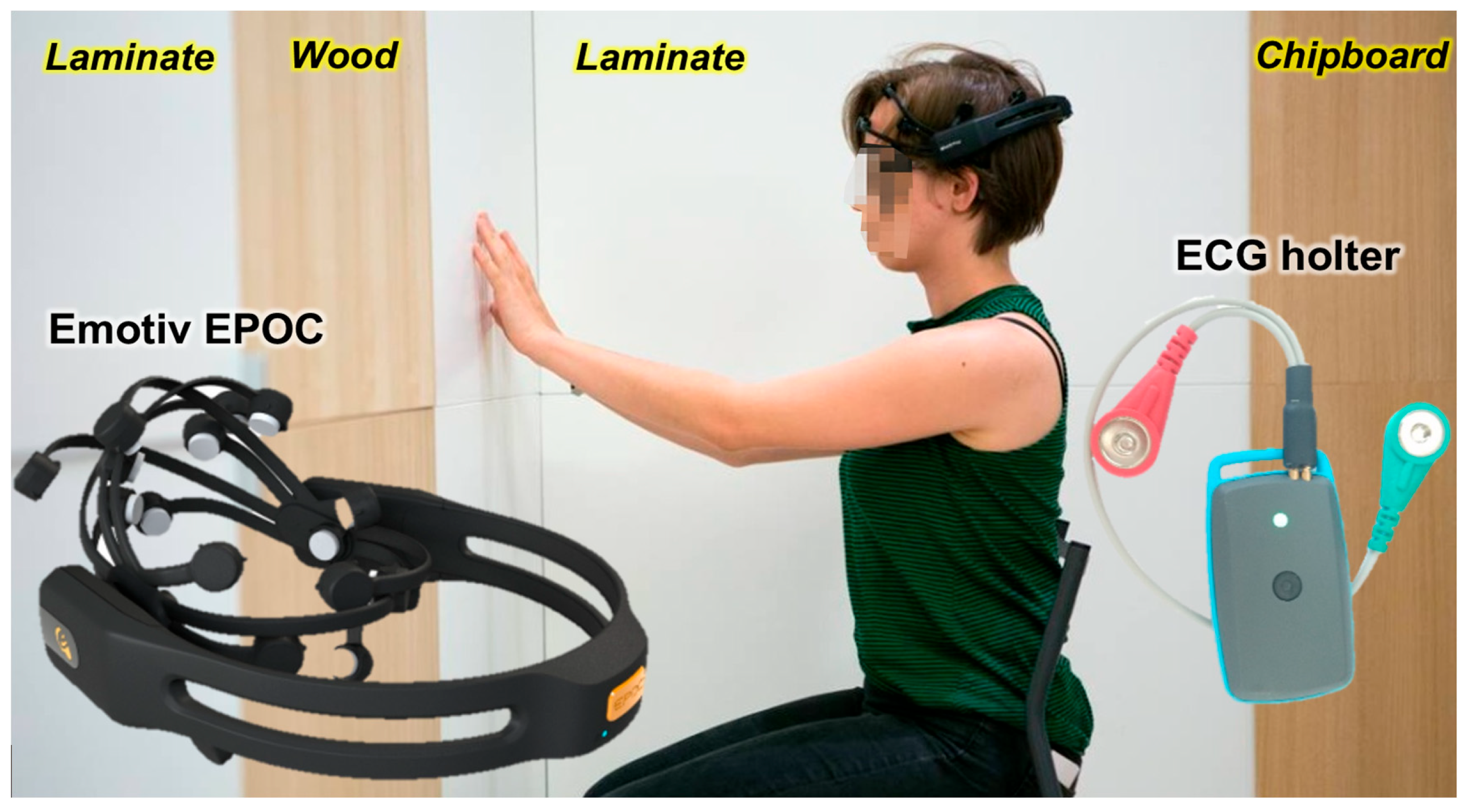

EEG brain waves were monitored using Emotiv EPOC, which is a 14-channel, 14-bit, wireless EEG with saline-based wet sensors, designed for contextualized research and advanced brain–computer interface applications. The used frequency was 128 Hz. For monitoring ECG and respiration, we used our holter. This holter (

Figure 2) is based on analog font-end TI ADS1292R and microcontroller ATxmega 128A3. The ADS1292R is a two-channel, 24-bit, delta-sigma analog-to-digital converter with a built-in programmable gain amplifier, internal reference, and an on-board oscillator. The version used also includes a fully integrated impedance measurement function for respiration monitoring. The sample frequency was set at 500 Hz. All the measured data were evaluated afterwards by using the Labchart program from the ADInstruments company, while statistical analysis was conducted in Microsoft Excel.

Both pilot studies were designed to test methodological tools and refine hypotheses for future large-scale investigations. The data gathered provide preliminary insights into how timber is perceived across sensory, cognitive, and cultural dimensions in tourism-related spaces.

4. Results of Pilot Study 1—Visitor Questionnaire

The objective of this pilot study was to explore how visitors/potential users at the CONECO building industry fair, Bratislava, 2025, perceive wood materials in public and hospitality-oriented interiors, with a focus on emotional comfort, cleanliness, and design preferences. A structured questionnaire was administered to 37 participants as a pilot respondents’ group consisting primarily of adult visitors to the fair, which provides a relevant setting to target respondents with some interest or familiarity in architecture and interiors, in many cases stakeholders in the decision process, who can be considered to be a specific group.

The survey included both closed- and open-ended questions. The following key themes were covered:

Emotional and aesthetic impressions of interiors with visible wood;

Perceived hygiene and material trust;

Preferences regarding wood surface treatments (e.g., untreated, oiled, varnished);

Willingness to accept signs of natural wear or patina.

Visual prompts were also used: participants were shown photographs of different hospitality interiors with various degrees of wood use and surface aging. Responses were recorded anonymously and analyzed by using descriptive statistics and qualitative coding for open-ended answers.

The sample consisted predominantly of respondents aged 35–44 (30%, n = 11) and 45–54 (24%, n = 9). Younger participants (18–24 and 25–34) together made up approximately 35% of the sample (n = 6 + 7), while only 8% (n = 3) were aged 55 and older; one respondent did not sign his/her age. This indicates a relatively balanced representation of active adult age groups, with a majority in the middle-age range, which could correlate with decision-making roles in design, construction, or tourism-related industries.

The gender split among respondents was nearly equal, with 51% (n = 19) identifying as women and 49% (n = 18) as men. This balance helps ensure that the results are not biased toward a single gender perspective, especially when evaluating subjective qualities in material perception such as comfort, aesthetics, or hygiene.

The respondents’ holiday preferences (Q 3) are relatively evenly distributed among three primary types of destinations: cities (29%, n = 11), the countryside (27%, n = 10), and mountains (27%, n = 10). This suggests a balanced range of interests among participants, encompassing urban cultural experiences, rural tranquility, and natural landscapes. A smaller portion of participants mentioned water-based destinations (8%, n = 3) such as lakes or coastal areas, while others indicated unspecified alternatives (8%, n = 3). This reflects a moderate diversification in recreational preferences beyond the main categories.

The data suggests that the design and material strategies for tourism infrastructure should consider a variety of contexts—urban, rural, and alpine—when evaluating the role of natural materials such as wood in shaping visitor experiences and comfort.

When asked whether ecological aspects (Q 4) (such as the use of natural materials or renewable energy sources) play a role in choosing accommodation, over half the respondents (51%, n = 19) indicated that it is very important to them. An additional 35% (n = 13) considered it somewhat important, while only 14% (n = 5) stated that it is not important in their decision-making process.

These results suggest that, for a significant majority of the participants, ecological values and sustainability are key considerations in selecting a place to stay. This finding supports the relevance of integrating natural materials—such as wood—into recreational and tourism-related architecture, not only for aesthetic or psychological benefits, but also as a response to users’ sustainability expectations.

In Question 5, the majority of respondents (57%, n = 21) stated that they prefer tourist destinations—such as restaurants, attractions, or public spaces—that use authentic natural materials. A significant portion (40%, n = 15) answered that their preference depends on the context, suggesting that material choices are not evaluated in isolation but in relation to broader design, function, and setting. Only one participant (3%) said that they do not prefer such environments.

This indicates a generally favorable perception of natural materials in tourism-related spaces, although contextual and design considerations remain important in shaping user preferences. The findings also support the relevance of material authenticity as a potential factor influencing visitor satisfaction and destination image.

When asked about their aesthetic preferences (Q6: How would you rate the atmosphere in tourist locations that use wood as their main building material (e.g., hotels, restaurants, cottages, and public spaces?)), nearly two-thirds of respondents (65%, n = 24) stated that they “clearly prefer wood” in interiors and environments. An additional 32% (n = 12) expressed a preference for a mix of natural and modern materials, while only one respondent (3%, n = 1) stated a preference for modern materials alone. No respondents declared themselves neutral.

These results confirm that wood has a strong symbolic and aesthetic appeal among the respondents, suggesting that material selection—especially when it comes to visible wood surfaces—may significantly influence emotional engagement and perceived authenticity in public or tourism-related spaces.

When asked whether the presence of wood influences their selection of accommodation (Q7), the majority of respondents (68%, n = 25) indicated that wood is a factor, but not a primary one. An additional 22% (n = 8) reported that wood is one of the factors they actively consider. Only one respondent does not consider it at all (3%, n = 1), while only a small fraction had never thought about it (8%, n = 3).

This suggests that, while wood may not be the decisive factor for most, it does play a role in shaping user preferences, particularly at a subconscious or secondary level. These results support the notion that natural materials like wood contribute to the perceived quality or appeal of an accommodation, even if not always explicitly prioritized.

Economic factors were also important, including a willingness to pay more for accommodations furnished with natural materials (Q8) and the perceived economic impact of natural materials in tourism architecture (Q9).

The majority of respondents expressed a moderate willingness to pay more for accommodations in tourist facilities that use natural materials such as wood. Specifically, 58% (n = 22) stated they would be willing to pay more if the price difference was not significant, and 23% (n = 9) indicated that their willingness depends on the overall offer and quality of the accommodation. Only 8% (n = 3) of respondents declared they are clearly willing to pay more regardless of the price. Conversely, 11% (n = 4) of participants are not willing to pay more for such features.

These results suggest that, while the use of wood and natural materials can enhance the perceived value of a space, it is not a decisive factor unless supported by an overall high-quality experience or reasonable pricing. The price sensitivity observed here aligns with broader trends in sustainable tourism, where ecological preferences exist but are often moderated by budget constraints and perceived value. When asked whether the use of authentic natural materials, particularly wood, in tourist facilities contributes to an increased visitor interest and economic success, respondents showed a strong inclination toward positive perceptions.

A clear majority, 57% (n = 21) of participants, indicated that natural materials attract tourists and thereby enhance the economic potential of a location. An additional 27% (n = 10) supported this idea, but with a caveat: they believe that natural materials contribute to economic success primarily when combined with broader ecological strategies, such as sustainable energy use or responsible land management.

In contrast, only 3% (n = 1) believed that natural materials have no significant influence on economic outcomes in tourism. Meanwhile, 14% (n = 5) reported that they were unsure or did not have enough knowledge to assess the impact.

Overall, the responses reflect a widespread belief that materials—especially wood, play a meaningful role in shaping visitor interest and can be a contributing factor in the economic viability of tourism facilities. Yet, the nuance offered by more than a quarter of respondents also highlights the importance of viewing material choices as part of a broader sustainability strategy rather than in isolation.

Through the questionnaire, we wanted also to explore the perceived connection to nature through the usage of wood (Q10).

The majority of respondents (57%, n = 21) indicated that the use of wood in tourism-related buildings definitely makes them feel more connected to nature. An additional 43% (n = 6) agreed to a certain extent. Notably, none of the respondents selected the options “No” or “I don’t know”.

This unanimous affirmation underscores the strong symbolic and affective role wood plays in reinforcing a sense of natural connection in built environments. The findings are consistent with the literature on environmental psychology and biophilic design, which highlights the importance of natural materials—especially wood—in supporting psychological restoration and a feeling of coherence with nature.

Such a high degree of agreement suggests that wood is not merely an aesthetic choice but a perceptual tool that fosters deeper emotional and symbolic ties with the natural world in recreational and hospitality settings.

One very important part of the study was the exploration of the perception of oak wood surfaces in tourist settings (Q11).

The first photograph used in the questionnaire was a raw oak wood surface without chemical surface treatment in interaction with different glasses filled with colored drinks and their marks, representing daily praxis on surfaces for dining (

Figure 3).

When asked about the acceptability of using untreated oak wood in public tourist environments (e.g., restaurants, hotels, visitor centers), respondents expressed a mixed but critical view:

In total, 38% (n = 14) indicated that untreated wood “rather bothers them”.

A total of 5% (n = 2) found it clearly “bothersome”.

Meanwhile, 24% (n = 9) remained neutral, and another 24% (n = 9) said it “does not bother them”.

Only 3% (n = 1) indicated it “rather does not bother them”.

These findings suggest that more than 40% of the respondents expressed some level of concern about the presence of untreated wood in public or hospitality environments, likely reflecting worries about hygiene, staining, or perceived maintenance issues—even when informed about the wood’s tactile and antibacterial benefits. The substantial neutral segment reflects the uncertainty or ambivalence of the general public regarding such material properties.

Attitudes improved significantly when participants were asked about oak wood treated with a hard wax oil finish:

A majority of 54% (n = 20) stated that the treated wood “does not bother them”.

A total of 16% (n = 6) chose “rather does not bother me”.

A total of 22% (n = 8) remained neutral.

Only 8% (n = 3) indicated a mild dislike, and none selected the strongest negative option.

This shift toward acceptance and comfort suggests that surface treatment—particularly one that preserves the natural look while providing protective benefits—is an important factor in the acceptance of materials in tourism-related environments. It also implies that visual cleanliness, maintenance expectations, and tactile comfort are significant contributors to perceived suitability.

Q12—Material Preferences in Interior Design

When asked whether they prefer wooden elements in interior design (e.g., furniture, flooring, walls) over modern materials like glass, concrete, or plastic, a strong majority of the respondents expressed a clear preference for wood:

In total, 65% (24 respondents) said they definitely prefer wood.

A total of 32% (12 respondents) reported that they like wood but also appreciate modern materials.

Only 3% (one respondent) indicated a preference for modern materials, and no respondents selected “no opinion”.

This overwhelming preference for wood—whether exclusive or alongside modern materials—suggests a widespread emotional and aesthetic appreciation for wood in tourism and hospitality interiors. It may reflect associations of wood with warmth, comfort, tradition, and authenticity. The near absence of preferences for fully modern materials also signals a possible fatigue or an emotional detachment from colder, more industrial aesthetics in leisure spaces.

In the final phase, a visual test about material sample (

Figure 4) preference was executed.

Participants were shown material collages and asked to choose as a tourist which sample would be more attractive for a hotel or restaurant interior.

A decisive 88% (approximately 33 respondents) preferred Sample 2.

Only 9% (around 3–4 respondents) chose Sample 1.

No one indicated that they found neither option attractive.

One response was left blank or unclassified.

Sample mix 1 consisted of modern ceramics, high end white laminate, white stone, and silver finish metal, with everything in achromatic colors.

Sample mix 2 consisted of oak wood (with stains on the surface), cork, and clay brick.

The strong skew toward Sample 2 suggests a consistent alignment between visual material preference and the earlier verbal affirmation of wood as the desired interior material. This coherence strengthens the argument that wood is not only theoretically valued but also immediately attractive in real-world design situations.

4.1. Discussion

The findings from this pilot study reinforce the theoretical claims presented in

Section 3. First, the strong preference for wood in tourism interiors reflects its capacity to evoke biophilic and emotional responses. Descriptive terms such as “cozy”, “relaxing”, and “authentic” confirm wood’s role in shaping sensorial and affective experiences in line with biophilic design theory [

16,

17].

Second, the preference for untreated or oiled wood, coupled with nuanced responses about wear and hygiene, echoes the theoretical discussion on authenticity and sensorial materiality. Respondents valued patina and traces of use when they appeared intentional—supporting the idea that aging can enhance authenticity, but only when framed as part of a maintained aesthetic rather than neglect [

23].

Moreover, concerns about cleanliness—especially in high-contact or food-related areas—highlight the tension between visual cleanliness and material trust. Although many respondents found untreated wood visually pleasing, they expressed reservations about its hygienic acceptability. These perceptions mirror the broader cultural ambivalence discussed in

Section 3.3, where surface gloss and smoothness serve as proxies for hygiene, despite contradictory scientific evidence [

33].

The responses also indicate that wood’s acceptance in tourism interiors is not universal, but conditional. Factors such as the location within the facility (spa vs. restaurant), surface treatment, and contextual cues influence acceptance. This supports the idea that visual framing, cultural expectations, and material care strategies must be considered in design.

Finally, the finding that most respondents would pay more for natural materials—if quality or experience matched—suggests that wood’s perceived value extends beyond its physical properties. It embodies symbolic capital that aligns with sustainability, authenticity, and emotional experience, reinforcing its relevance for hospitality design with an ecological and human-centered focus.

These reflections offer a nuanced understanding of user attitudes and pave the way for further investigation using physiological methods, as will be introduced in the upcoming research studies.

The findings confirm that natural wood materials are positively associated with emotional comfort and perceived authenticity in tourism-related interiors. At the same time, concerns about hygiene and surface maintenance persist, especially when wood appears worn or untreated. These tensions align with the theoretical framework presented in

Section 3, where wood’s symbolic and sensorial value often competes with practical expectations of cleanliness.

Interestingly, the acceptability of aging surfaces seemed to depend less on the material itself and more on how its presence was framed, whether as intentional, cared-for, or allowed. This indicates that communication, cultural familiarity, and surface treatment strategies can mediate how aging is interpreted. These insights provide a foundation for the second pilot study, which shifts from self-reported data to physiological measurements of user experience.

Despite these insights, several methodological limitations must be acknowledged. The sample was self-selecting and limited to visitors of a building and design fair, potentially biasing the results toward more design-aware individuals. Visual stimuli in the survey may have influenced perception disproportionately, especially due to framing, lighting, or composition. Cultural background also likely shaped responses—what is perceived as “authentic” or “clean” in one context may carry different connotations elsewhere. These constraints limit the generalizability of the findings, though they still provide valuable directions for further inquiry.

4.2. Methodological Limitations and Critical Reflection

While the questionnaire offered useful initial insights into public attitudes toward natural wood materials in tourism and recreational contexts, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sampling context—visitors at a building and design fair (CONECO 2025)—likely attracted individuals already interested in sustainability, architecture, or materials. As such, the responses may over-represent environmentally conscious or design-sensitive perspectives, limiting generalizability to the broader tourist population.

The sample size (n = 37), while sufficient for a pilot study, is too small for drawing statistically robust conclusions. Therefore, this dataset should be interpreted as a preliminary exploration, useful for identifying patterns and framing hypotheses rather than testing them.

Finally, although the responses were overall very positive toward wood as a material, this homogeneity may also indicate a lack of critical or dissenting perspectives, which has to be verified with a higher volume of respondents from different branches and diverse social and cultural contexts.

5. Results of Pilot Study 2: Physiological Experiment

Following the questionnaire-based investigation, which revealed a clear emotional and aesthetic preference for wood but highlighted tensions around hygiene and surface condition, the need arose for a more objective method of understanding users’ physiological/somatic responses to materials. While verbal responses are shaped by prior experiences, social desirability, or visual association, physiological data can reveal subconscious affective reactions. This second pilot study builds on the insights of Study 1 by introducing biometric measurements that capture how the human body in real-time reacts to contact with wood and wood-based surfaces. The study focused especially on the paradoxical perception of hygiene and cleanliness, as this emerged as a recurring concern in both qualitative and quantitative responses.

While the first pilot study provided insights into the self-reported perceptions of wood in tourism interiors, these findings are inherently shaped by subjective bias, expectations, and cultural framing. To complement these results, a second pilot study was conducted in collaboration with the Faculty of Electrical Engineering and the Faculty of Architecture at STU. The aim was to assess the direct influence of contact with different surface materials on users’ physiological responses, with a special attention to perceived hygiene, emotional comfort, and cognitive activation.

The design and choice of materials have an impact on the behavior of individuals and their health, and these influence physiological parameters.

The experiment involved 11 healthy adult volunteers (3 women, 8 men), all right-handed. Participants were alternately exposed to three material environments (1 × 2 m panels): natural oak wood, chipboard, and white laminate. Each environment exposure lasted 150 s and included the following:

Sitting with closed eyes (1 min);

Touching with closed eyes (30 s);

Sitting with open eyes (1 min).

Physiological measurements included the following:

EEG (Emotiv EPOC)—focusing on alpha (8–12 Hz), beta (12–30 Hz), and SMR (12–15 Hz) waves;

ECG holter—tracking heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (LF/HF ratio);

Respiration sensors—monitoring respiratory frequency (RF) and respiratory volume (RV).

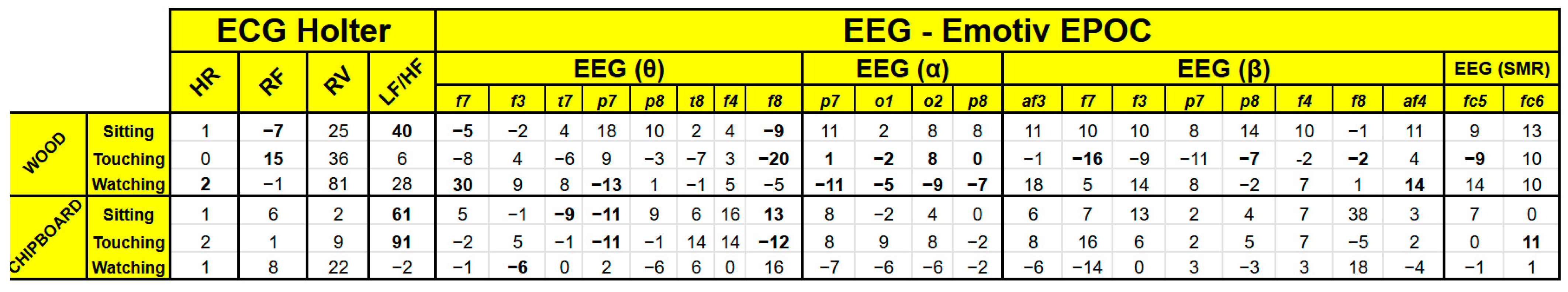

The results were compared against a white laminate baseline, and data were statistically processed using Labchart and Excel (

Figure 5).

General Trends

- •

Relaxation effect (eyes closed)

- ○

In front of wood, the RF decreased by −7 ± 4% and the RV increased by +25%.

- ○

In front of chipboard, the RF increased by +6 ± 16%, and the RV only by +2%.

- •

EEG alpha activity

- ○

Sitting in front of wood slightly decreased the alpha (−8.2 ± 29%), accompanied by an increased beta (+8 ± 28%) → suggesting active attention.

- •

EEG SMR (relaxed focus)

- ○

Wood increased SMR by +11.9 ± 31%, compared to −0.1 ± 11% for chipboard.

Touch Phase

Touching wood raised the RF by +15 ± 10% and RV by +36 ± 48%.

Touching chipboard showed a minimal respiratory response (RF +1 ± 24%, RV +9 ± 74%).

The EEG alpha increased by +4.2%, and SMR by +9.8% in the right hemisphere during wood contact.

The EEG beta (left frontal) dropped significantly with wood: −16 ± 16% (suggesting a relaxation of logical/analytical areas).

Stress Index (LF/HF ratio)

LF/HF increased only moderately during wood exposure: +6%.

The chipboard triggered a dramatic increase, +91%, suggesting stress or cognitive load.

Heart Rate

These results confirm that natural wood surfaces elicit calming and cognitively supportive effects, particularly when touched or viewed with minimal distractions. Increases in EEG SMR waves and decreases in frontal beta activity indicate a shift toward relaxed but attentive states—ideal for hospitality and wellness environments.

The physiological data also demonstrate that contact with chipboard induces a greater arousal and sympathetic nervous activity, reinforcing subjective perceptions of artificial materials as less comfortable or trustworthy.

This supports the hypothesis that the authenticity of wooden surfaces makes a difference and that the authentic surfaces have a stronger impact on well-being and strengthen the biophilic experience, important for restorative environment designing.

6. Discussion/SWOT Analyses and Conceptual Framework

This paper builds on insights from interdisciplinary desk research in the fields of tourism management, anthropology, cognitive psychology, human centered design, and material engineering/wood science, focusing on tourist experience, biophilic design, authenticity, and material perception in tourism environments. Then, it explores the possibility of further research methods through two pilot studies: one focused on perceived atmosphere and material symbolism (via a visitor questionnaire focused on aesthetic and symbolic perceptions of wood in hospitality interiors), the other on physiological response to contact with different wood-based materials, focusing on the importance of the authenticity of the material surface—the physiological experiment testing how different materials affect users’ stress levels, breathing, and brain activity.

The concluding SWOT analysis synthesizes the strategic design potential of wood in contemporary tourism interiors through a combined theoretical and empirical lens.

It maps the strengths, weaknesses, threads, and opportunities of using timber in the design of contemporary tourism architecture and infrastructures in general.

Discussion—Multisensory experience of wood and its contribution to memorable tourist experience vs. stress

Although the original empirical contexts of stress in built environments and material contexts focused on workplaces [

49,

50] and healthcare [

18,

20], the insights from research studies about stress and indoor built environments

are highly transferable to recreational and tourism environments. Both domains share a need for emotionally supportive, non-institutional atmospheres that foster well-being, restoration, and trust. The current study extends this body of work by applying these findings to hospitality contexts, where similar mechanisms of affective material perception and hygienic interpretation are at play.

A description of the multisensory nature of the human mind has emerged from the field of cognitive neuroscience research.

Traditionally, architectural practice has been dominated visually (by the eye/sight). In recent decades, though, architects and designers have increasingly started to consider the other senses, namely sound, touch (including proprioception, kinesthesis, and the vestibular sense), smell, and, on rare occasions, even taste, in their work [

51].

Positive characteristics have already been explored, tested, and summarized in many referenced research studies. These positive outcomes, however, are highly context-dependent—shaped by spatial purpose, cultural expectations, surface treatment, and perceptions of hygiene. Nevertheless, these findings originate mainly from controlled settings, and less is known about how they translate into dynamic public or semi-public recreational spaces, where multisensory perception is fleeting and influenced by social norms and anticipated hygiene levels.

The main result of the study of the psychological dimensions of wood–human interactions, demonstrated that a wooden environment is perceived as more comfortable than a plaster one and is able to induce a higher degree of positive feelings in participants. Furthermore, the multimodal perspective in the evaluation of an indoor setting has led to the revelation that a wooden room was judged as being more muffled, odorous, and perfumed compared to the other one. Notably, it was also observed that the biophilia degree of the participants modulated the magnitude of such effects. These latter aspects (biophilia degree and multiple sensory evaluation modalities) appear then to be crucial when investigating how people perceive the indoor environments in which they live or work [

52].

Tourism, hospitality, and event managers seek to provide WAW experiences to their visitors through better design and management [

3].

What contributes to the WAW effect? Aarchitecturally, authentic multisensory design considers how materials like wood interact with more than just the visuals, enriching environments through texture, acoustics, and scent [

51].

In public interiors, sensory engagement across modalities creates more embodied, meaningful experiences [

53].

Wood engages our senses beyond vision—it resonates through touch, smell, sound, and spatial feel. Wood, with its warm color, fascinating texture, high contact comfort, pleasant sound interaction, contribution to acoustic well-being, pleasant scent, and optimal sorption activity, offers many forms of sensory stimulation that most users find to be pleasant and appealing.

Importantly, recent studies have also emphasized the agentic role of wood itself. In a post-humanistic framework, it is explored how wood can be experienced not merely as a passive material, but as an active co-creator of meaning, particularly through its grain, scent, temperature, and resistance during physical interaction. In multisensory design, materials such as wood offer a richer experience that activates embodied memory and emotional resonance [

54].

The quality of the wood surface and the presence or absence of finishing are very important in terms of the sensory experience.

Studies show for instance that natural, smooth wood surfaces are rated significantly higher in emotional touch experiences than coated ones [

18,

19,

55].

This is especially relevant in tourism: for instance, wooden stadium designs improve spectator satisfaction through multisensory, biophilic cues [

56]. The incorporation of wood into tourism architecture, therefore, taps into a holistic sensory appeal that enhances emotional connection and place attachment. This makes it a suitable material for a multisensory environment, with the potential to provide a memorable touristic experience.

Memorable tourism experiences significantly influence place attachment, and hedonic and eudaimonic well-being fully mediates this relationship. The frequency of visits does not negatively influence these relationships. Tourists develop an attachment to a destination when their experience is memorable, satisfying, and enhances their purpose and meaning in life [

57].

The virtual restoration method also has potential for researching preferences. In addition to visual and acoustic experiences, haptic technologies represent the potential for expanding sensory perception, which is not yet sufficiently used in the architectural sector [

58].

Discussion: Maintenance and Material Performance in Tourism Infrastructure

The long-term success of wood in tourism-related architecture and interior environments is not determined solely by its aesthetic or sensory benefits, but also by how well it performs over time under operational conditions. In the context of recreational buildings and public hospitality spaces, maintenance becomes a critical factor influencing both material longevity and the perceived environmental quality.

Wood, while being a renewable and environmentally advantageous material, requires specific attention to surface treatment, cleaning protocols, and environmental exposure in order to ensure an optimal performance in high-traffic settings such as lodges, visitor centers, or eco-resorts.

Studies have shown that proactive maintenance planning and sustainable maintenance management strategies extend the service life of materials. Maintenance strategies that prioritized indoor environmental quality (IEQ) showed positive impacts on both sustainability and longevity [

59].

The focus on material conservation in sustainable maintenance not only reduces the environmental impact but also contributes to longevity. Pomponi et al. (2021) found that strategies emphasizing material durability and repair over replacement could extend the lifespan of building components by 30–40% [

60].

Building components in public use areas are subject to wear-and-tear cycles that must be anticipated through smart design and maintenance strategies [

61]. This is particularly relevant for wood surfaces, where the balance between natural patina and degradation can shape users’ perceptions of cleanliness, professionalism, and comfort.

Is a worn wooden surface perceived as low professionalism on the part of the providers or as something unique with a “personal touch”? In our first pilot study, we included questions dealing with this issue in the questionnaire.

Furthermore, a well-maintained wooden environment not only retains its visual and functional integrity but also sustains the positive emotional and biophilic effects identified in the earlier parts of this study. In tourism architecture, where first impressions and user experience directly affect satisfaction and return visits, maintenance should be considered a performative element of the design itself.

Essentially, natural wood’s durability and the longevity secured by appropriate maintenance measures prevent an earlier degradation. In addition, its acceptable wear creates a visual and tactile appeal. The acceptable patina, in combination with its influence on well-being and a relaxing state of body and mind, creates an ideal environmental setting for recreation.

Discussion sustainability and sustainable tourism

To be considered truly ecological, wood should originate from sustainable forestry—ideally certified under PEFC or FSC standards. In Slovakia, the most environmentally friendly approach is regarded as “close-to-nature forest management”, which mimics the natural forest dynamic that is a prerequisite for the ecological stability of forests. There are pioneering forest management companies that offer this kind of forest management [

62].

In this form, forests have very appealing aesthetics thanks to their naturalness and form variability, in combination with appropriate and respectfully placed visitor infrastructures, helping our nervous system to recover and to have memorable tourist experiences, along with location attachment. This interaction of natural settings—built infrastructure and human—will be further explored, tested, and evaluated within our planned investigations in selected localities in the upcoming years.

Biophilic experience, transformed into a memorable tourist experience, has the potential to foster the environmental awareness of visitors, especially children and youth.

In addition to its physiological and psychological benefits, wood materials hold a distinctive position in the discourse on sustainable tourism. As tourism infrastructure increasingly intersects with urban and recreational development, the use of natural materials, especially locally sourced timber—can contribute to both environmental responsibility and visitor well-being.

Sustainable tourism is based on a long-term perspective. It adheres to ethical principles and is geared towards social justice, respect for cultural differences, environmental responsibility, and, last but not least, economic benefits [

45].

Finally, given the carbon storage capacity of wood and its ecological advantages, optimizing its maintenance contributes to overall sustainability goals—especially when integrated with local forestry cycles and long-term material tracking frameworks and certification systems.

These findings predestine wood for restorative environment design, for recreation, and for leisure. To explore this in more depth and to conclude with the pros and cons, we have made a SWOT analysis of the application of wood in tourism spaces.

SWOT Analysis: Wood in Tourism Spaces

Strengths

Strong emotional and biophilic appeal (questionnaire and physiological data);

Provision of multisensory experiences that can impress positively and contribute to memorable tourist experiences and place or brand attachment;

Proven calming physiological effects (reduced arousal, increased SMR);

Support of authentic and place-based atmospheres;

When sourced responsibly, a renewable and sustainable material;

A part of tourist experience that can empower environmental awareness and environmental sensitivity.

Weaknesses

Perceived as less hygienic, especially in an untreated or worn condition;

Susceptibility to wear and damage in high-traffic settings;

Maintenance requirements higher than for synthetic surfaces;

Cultural prejudices;

Purchase price higher than that of synthetic substitutes and imitations.

Opportunities

Proactive maintenance operational plan considered in designing process;

Educational strategies to improve perception of wood hygiene;

Design framing and surface treatments that preserve authenticity while enhancing durability (e.g., options of biofilm-based finishing);

Integration into wellness and nature-based tourism experiences.

Threats

Preference for synthetic imitations driven by visual cleanliness expectations;

Misuse or poor detailing that leads to deterioration or negative associations;

Regulations or standards that may disadvantage natural materials in public spaces.

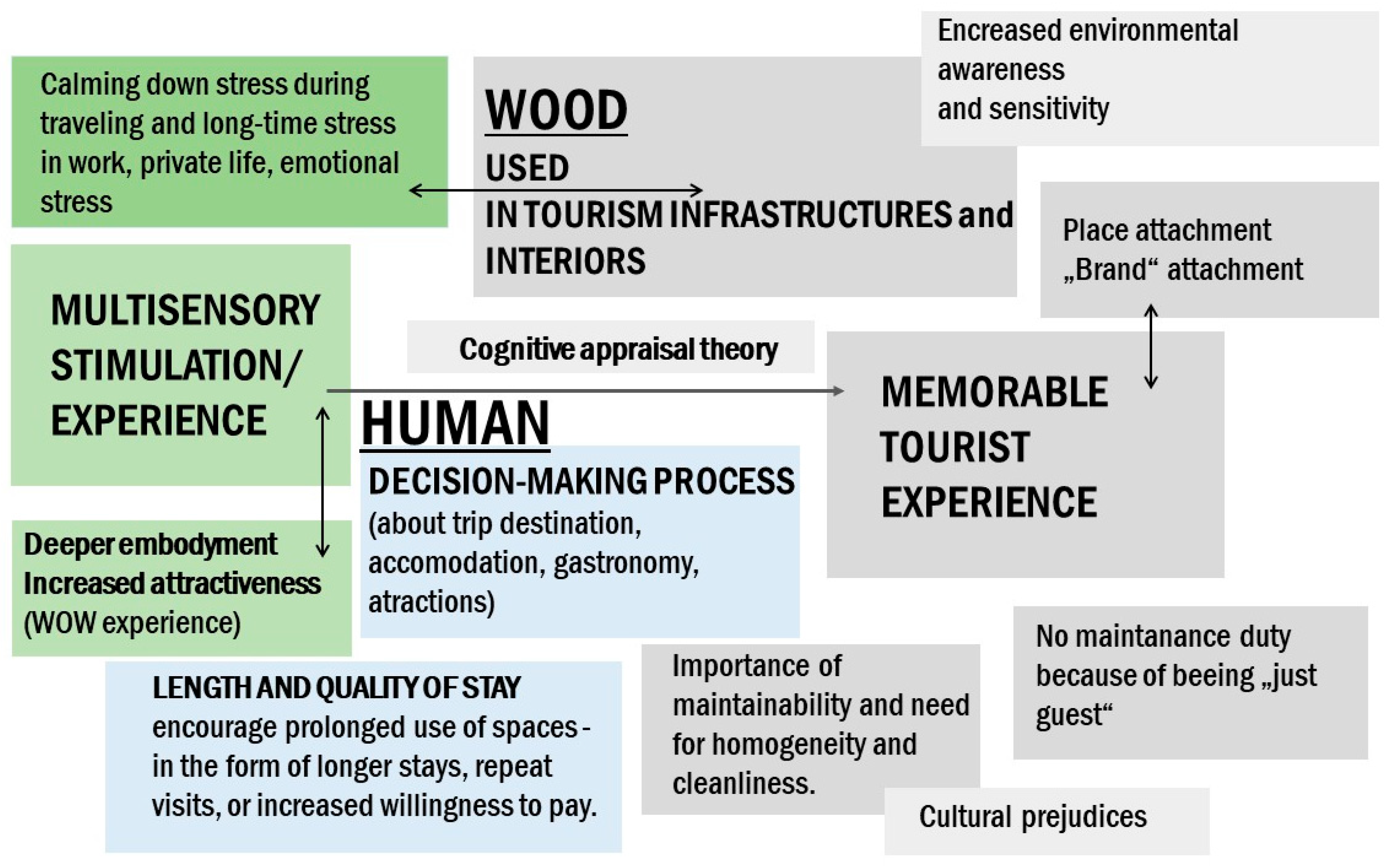

Since the project is in its initial phase, in order to better understand the investigated issue as well as a conceptional framework for this study, the outline shown in

Figure 6 was formulated. It points out a significant agenda—the ideas, quantities, parameters, and phenomena that enter into the process of the interactions between the wood used in tourism infrastructure, including indoor spaces, the decision-making process, and the multisensory stimulations/experiences that form a memorable tourist experience.

7. Conclusions

Natural materials with authentic surfaces have their place in creating a regenerative environment, eliminating not only the long-term stress from which we need to relax in our free time, especially during vacations, but also the acute stress that arises during travel.

From a sustainable tourism perspective, wood offers eco-efficient construction benefits, along with emotional and cultural significance—provided that long-term maintenance, hygienic clarity, and aesthetic authenticity are intentionally addressed.

As such, wood elements should not be considered mere decorative nods to tradition but rather active, communicative components that contribute to multisensory engagement, “environmental storytelling”, and authentic atmospheres in tourism architecture.

When tourists cognitively appraise these environments positively, the experience can become both memorable and transformative.

From a hygiene perception perspective, there is an important paradox: while wood evokes relaxation and sensory comfort, it also raises concerns about cleanliness—often unrelated to any measurable stress markers. Despite wood’s physiological benefits, some participants verbally questioned its hygienic appropriateness.

These findings suggest that visual and cultural framing significantly shape hygiene perception and that wood’s positive physiological effects must be supported by appropriate surface treatments, maintenance visibility, and environmental communication in order to overcome biases. This study explored the role of wood as a sensory and emotional material in tourism-related interiors through two complementary pilot studies: a perception-based questionnaire and a physiological experiment. The findings suggest that wood supports feelings of comfort, authenticity, and naturalness on both the subjective and the physiological level.

However, these benefits are not automatic. Perceptions of cleanliness, maintenance, and intentionality play critical roles in user acceptance. Wood is emotionally and sensorially powerful—but it must be framed, treated, and maintained in ways that align with hygiene expectations, especially in public settings.

The integration of wood into recreational and tourism design is strongly backed by empirical evidence highlighting its psychological, ecological, and experiential value.

Designers and architects working with timber in hospitality contexts must consider not only the aesthetics and sustainability of wood, but also the cultural and perceptual cues that shape user trust and comfort. With the right strategies, wood can serve as both an ecological asset and an experiential strength in tourism architecture.

Uniqueness of the research study

This study contributes to a better understanding of the tourist experience and the mechanisms that turn it into a memorable tourist experience, and the role of the materials used in tourist infrastructure.

It clearly specifies how wood as a biophilic material uniquely functions in the contexts of design and tourism compared to and coming out of other studies dealing with the application of wood in administrative buildings, educational environments, or healthcare settings.

The study shows the multisensory character of wood as part of the biophilic experience, plus the importance of a sustainable approach.

It is focused also on topics of maintenance and perceived hygiene, which in this sort of environment have a different context. While visitors usually do not feel responsible for it, since they are users—“guests”—or visitors with specific backgrounds, this factor may nonetheless influence their visitor satisfaction.

What is different in a tourist experience? It is marked by the temporariness of the experience and thus the possibility to spend time in an environment where maintenance is normally the responsibility of the owners/providers.

Moreover, the affective warmth and sensory richness of wood surfaces, structures, and elements may encourage a prolonged use of spaces—whether in the form of longer stays, repeat visits, or an increased willingness to pay. These hypotheses merit a more targeted investigation, but the current pilot findings already indicate that the material component is not neutral: it acts as a behavioral and symbolic signal with potential economic and psychological consequences for tourism infrastructure designs.

Overall, this study contributes to a better understanding of the relationship between the perception and symbolism of wooden elements and surfaces and the quality of the touristic experience in all stages.

Limitations and future research

The limitations of this research are related to the small number of respondents (37 and 11), which makes for a low statistical relevance and generalizability of the research outputs.

Despite this, it has contributed to a better understanding of the dichotomy between culturally ingrained perceptions and physiological responses.

This pilot study forms part of an introduction for further research into human interactions with the environment during recreation and examines the role of materials, in this case wood, in this interaction. The Tourism Design project will include three interventions in selected locations in Slovakia, where it will be possible to apply, test, and evaluate both the subjective and objective parameters of human perception, including wood–human interactions, under specific conditions. The intervention will also allow for the investigation of the attachment to objects and environmental settings by local communities and visitors—temporary users. In the upcoming studies, it will be possible to map the environment and the cultural background of all the selected localities.

It will help to define the design strategies and guidelines for the application of wood and wood-based materials in objects of tourist infrastructure. These strategies will be further developed using mixed-methods research and tested by design and learning by acting within the planned interventions.