1. Introduction

Traditional villages refer to those that were formed earlier, have rich traditional resources, have certain historical, cultural, scientific, artistic, social and economic values, and should be protected [

1]. In terms of historical and cultural value, traditional villages have a long historical background and rich cultural significance. China and Italy have a large number of traditional villages with long history, unique natural scenery and profound cultural heritage, and bear witness to the rich history and culture of both countries. The disorderly urbanization in China has led to the destruction of traditional villages, the decline of industries, the emigration of the population, and the deterioration of cultural values. According to the Blue Book of Chinese Traditional Villages: Survey Report on the Protection of Chinese Traditional Villages (2017), the total number of natural villages in China was 3.63 million in 2000, but had declined to 2.71 million in 2010, a reduction of 900,000 in just ten years, with an average of 80 to 100 villages vanishing every day [

2]. In the No. 1 Central Document: Comprehensively Promoting Rural Revitalization issued by The State Council of China in 2021, it is clearly stated that traditional villages, traditional houses and historic and cultural villages and towns should be protected [

3].

Recent research has mainly concentrated on the background and policy responses to traditional villages [

2], as well as morphological differences and institutional comparisons between Chinese and Italian villages [

4,

5]. Building on these insights, this research argues that a systematic comparison of preservation and revitalization policy approaches in the two countries is necessary, along with a scientific assessment of the adaptability of the Italian model to the Chinese context, in order to meet the policy requirement that traditional villages, traditional dwellings, and historic and cultural towns and villages should be protected [

3].

A three-phase methodology was adopted to compare the preservation and revitalization strategies of traditional villages in China and Italy (see

Figure 1).

In the first phase, the legal and policy frameworks of the two countries were analyzed. This involved reviewing the content of relevant regulations to highlight institutional differences between Italy and China. In more detail, the analysis focused on the following factors to establish a quantitative basis for subsequent research: targets of legal protection, governance structures, and policy approaches.

In the second phase of the research, involving data analysis, governance tracing, and interviews, case studies were selected in each country for comparative analysis. Both are located in coastal mountainous regions with high scenic value and a concentration of traditional villages with rich heritage, contributing to tourism growth and regional prosperity. Fieldwork was conducted in the selected case studies, including interviews and questionnaires, as well as a GIS-based spatial measurement analysis using indicators such as landscape continuity and ecological corridor connectivity.

In the third phase of the research, a structured matrix was used to compare the corresponding modules for the protection and revitalization of traditional villages in China and Italy, thereby facilitating the extraction of experience and the assessment of transferability.

1.1. Traditional Chinese Villages

Chinese traditional villages refer to those that exhibit strong historical and cultural features formed and preserved in the long course of Chinese history [

6]. These villages are usually renowned for their unique architectural feature, cultural values and social structure, embodying rich historical, cultural and vernacular traditions, and reflecting the lifestyle and social order of ancient Chinese rural society. According to data released by the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development showed that there were 6819 villages in the list of traditional Chinese villages. There are significantly more traditional villages in the southern region than in the northern region, with the south accounting for 78 percent of the total and the north accounting for 22 percent [

7]. The number and distribution of traditional villages can be seen in

Figure 2.

The features of traditional villages are not only reflected in the architectural and cultural characteristics, but also deeply rooted in ancestral belief, including concepts of ethics and ideas of geomancy or feng shui. The combination structure of traditional villages emphasizes the moral and ethical relationship, pays special attention to the hierarchical system and the division of old and young, and advocates a spatial concept structured on a central focus. Ancestral temples are the authoritative carriers of clans, and most of them are located in the center of villages. As the ancients said, when a gentleman builds his palace, his ancestral temple is the first place, and he is sincere to the place where his ancestors originated, and all his tribes are from here [

8]. Therefore, building complexes often emphasize the structural order of ethical relationships. The spatial layout of traditional villages is deeply influenced by traditional geomancy theory (feng shui), which is clearly reflected in their spatial organization, architectural features, and relationship with the environment.

1.2. Traditional Italian Villages

Traditional villages in Italy are widely distributed, covering all regions of the country. The number and distribution of traditional villages can be seen in

Figure 3. The distribution of traditional villages in Italy is characterized by diversity and richness. From the Alps in the north to the Mediterranean coastline in the south, and including beautiful islands, many striking traditional villages are dotted throughout. The geographical diversity of Italy gives these villages a unique appearance and charm [

4].

The northern region is heavily influenced by the Alps, where traditional wooden and stone farmhouses are either isolated or loosely scattered across the countryside. Further south, the areas along the Alps display a wealth of dark gray or brown stone buildings, often featuring stone slab roofs or deep red tiles. These central villages are uniquely elegant in their historical and architectural character.

However, halfway up the mountain between Rome and Naples, subtle changes gradually emerge, and another world begins, the second of the two Italys: southern Italy. While the remoteness of the southern region has long been overlooked by tourists, the land has preserved a unique landscape. The landscape of southern Italy is rich and varied, encompassing the rolling green plateaus of Puglia, the plains of Sardinia and Sicily, the volcanic regions of Campania and the remote mountains of Basilicata and Calabria.

The traditional villages of southern Italy show great diversity in landscape, climate, architecture, people and customs. These villages are not only unique but also reflect the history and culture of the region. However, like villages in other regions, southern villages have gone through the same historical process. Defensive structures such as walls and trenches remain, and churches have become iconic buildings within the villages, often standing in the center or at the highest point, reminding people of their faith and spiritual home [

9].

To sum up, the diversity and richness of traditional Italian villages form their attraction. From the north to the south, from the mountains to the coast, and from architecture to customs, each village tells a unique story and displays unique beauty.

1.3. Comparison of Traditional Chinese and Italian Villages

China and Italy are both ancient civilizations and the cradles of Eastern and Western cultures, respectively. The two countries have a similarly long history and rich cultural heritage, with numerous cultural and historical sites, including many traditional villages. Although the two countries have different cultural backgrounds and geographical environments, there are still many common features in the physical characteristics of their villages [

10]. Traditional villages in China and Italy share a common feature: relatively remote access and inconspicuous locations. However, this feature has become an advantage, as villages in better locations have often been replaced or overtaken by modern development [

11].

By comparing the traditional villages of China and Italy, one can find that the two countries have similarities in spatial scale, historical heritage, natural landscape and geographical locations. First of all, the spatial scale of the villages in both countries is relatively small, the height of the traditional houses is not high, and the streets are winding, making them suitable for walking. Secondly, the villages have a long history. Many buildings and water management facilities have a history of hundreds or even thousands of years, and many folk stories are passed down. In terms of physical geography, most of the traditional villages of the two countries are located in valleys, rivers or beaches. They are situated near mountains and rivers and take advantage of their abundant resources to carry out agricultural activities, shipping and trade activities. In terms of geographical location, traditional villages in both countries are located at some distance from developed cities. Limited transportation and underdeveloped infrastructure have helped protect the villages, allowing them to relatively independently preserve their history, culture and features.

Although there are commonalities in traditional villages of the two countries, there are obvious differences in cultural values, architectural features, and development stages. Italian traditional villages retain a large number of medieval churches, and Catholicism provides the spiritual support and cultural foundation of people in these villages. In contrast, Chinese traditional villages have preserved a large number of ancestral halls, and clan culture has played a crucial role in the development of villages. Secondly, the character of traditional Chinese villages is completely different from that of Italian villages. Chinese villages advocate light elegance, freshness, and refinement, while Italian villages are characterized by bright colors and rich decorations, giving people a fairy-tale feeling. From the perspective of development stage, the protection of Italian traditional villages is relatively mature, the construction of villages is strict and orderly, and the development and protection are relatively balanced, while the protection and development of Chinese traditional villages started late, and the construction and style of villages in many places are not harmonious, the layout of industries is chaotic, and environmental health and modern services need to be improved. Although traditional villages in the two countries have different historical backgrounds and features, they face similar challenges in the context of globalization. More in detail, population loss, industrial decline, cultural decline, environmental damage and serious homogenization. The Italian and Chinese governments have issued policies and planning designs for rural revitalization to prevent the decline and disappearance of traditional villages, thereby protecting their architectural and cultural heritage and promoting their sustainable development.

China and Italy share four intertwined crises. First, massive rural–urban migration and aging populations hollow out villages. Secondly, the exodus severs inter-generational transmission so traditional crafts, festivals and folklore vanish. Moreover, once-vibrant public squares, temples and markets fall silent as younger residents leave and digital life replaces face-to-face interaction. Finally, the economic backbone (agriculture, handicrafts and local manufacturing) collapses under global competition, deserted farmland and the aging of artisans [

12].

2. Comparison of Protection and Utilization Modes of Traditional Villages

There are some similarities between China and Italy in the preservation and revitalization of traditional villages. Both countries attach great importance to the historical and cultural value and social significance of traditional villages, recognize their importance as cultural heritage, and are committed to protecting traditional buildings, features and cultural inheritance. Both countries have promoted the protection of traditional villages through policies, regulations and projects, including the restoration of ancient buildings and the preservation of traditional crafts. In addition, both countries utilize traditional villages as cultural tourism resources to attract tourists and promote local economic development, but in the process of revitalization, they also face the challenge of how to balance commercialization and preservation of traditions. Therefore, there are many similarities between China and Italy in the preservation and revitalization of traditional villages. However, some differences are also evident in the aspects discussed below.

2.1. Differences in the Objects of Protection Under Laws and Policies

China has a series of laws and regulations concerning the protection of cultural heritage and historic buildings, such as the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Cultural Relics, the Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Famous Historical and Cultural Cities, Towns and Villages, and the Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Famous Historical and Cultural Cities, Towns and Villages, among others. Various provinces and cities have enacted corresponding local laws and regulations to protect traditional villages and historic buildings. China has adopted policies at the national and local levels to promote the preservation and revitalization of traditional villages, such as the establishment of cultural heritage protection units, provision of financial support, and implementation of renovation plans.

In Italy, Legge sugli Spettacoli Naturali (Protection of Natural Beauty) and Legge per la Protezione dei Beni Culturali di Interesse Storico e Artistico (Protection of Cultural Objects of Historical and Artistic Value), enacted as early as 1939, clearly identify and protect certain built heritage and landscape types with special esthetic qualities (qualita estetica), and protects individual buildings of artistic, historical, archeological or ethnographic value. Since the 1960s, the Italian academic community has gradually shifted its understanding of architectural heritage from individual buildings to the whole historical built environment.

As illustrated in

Table 1, Italy long ago moved beyond single-building preservation, embedding entire village landscapes and community life within a unified system. China has only recently embraced contiguous protection, by which time rapid modernization had already fractured many villages with hybrid architecture, homogenized commerce, and ecological stress.

2.2. Different Management Mechanism

The preservation and revitalization of traditional villages in China are mainly promoted by the government through a top-down management mechanism, with departments at multiple levels from the central government to provinces, cities and localities in charge of coordinating planning, protection, development and supervision. The central government departments (the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, the National Development and Reform Commission, and the State Administration of Cultural Heritage) are responsible for formulating and implementing the overall plan, policies, laws and regulations for the preservation of traditional villages, coordinating the responsibilities of governments at all levels in the preservation activity, and promoting the overall coordinated development of the preservation work.; Provincial cultural and tourism authorities are responsible for formulating specific plans, policies and measures for the protection of traditional villages in their regions, organizing and promoting the preservation of traditional villages. At the same time, the Provincial Development and Reform Commission participates in the formulation and coordination of policies and plans to promote the protection and sustainable development of traditional villages. Prefecture-level cultural and tourism authorities are responsible for formulating and implementing specific plans for the protection of traditional villages within their respective regions, coordinating relevant departments and agencies to promote the protection and inheritance of traditional villages; In addition, prefecture-level planning and urban and rural construction authorities participate in the planning of the protection and development of traditional villages to ensure the rational use of the built environment; Village committees help organize the protection and management of villages at the local level to promote the inheritance of traditional culture; Village culture stations or cultural groups are responsible for cultural activities and inheritance of traditional villages, organizing publicity and education, and promoting residents’ participation.

In Italy, the preservation and revitalization of traditional villages mainly adopt a bottom-up approach and a top-down management mechanism. The European Union has formulated the framework of rural protection and development, and the Italian government has issued policies and regulations for the preservation and revitalization of rural heritage. The Gruppi di Azione Locale (Local Action Group), in cooperation with other social actors, leads the compilation of guidelines for the built rural heritage and provides operational guidelines for the protection and restoration of traditional villages [

13]. It also provides scientific guidance for the preservation and renewal of traditional buildings. These policies are approved and accepted by local governments in Italy with the support and cooperation of the central government.

The preservation and revitalization policies of traditional villages in China takes cultural heritage preservation and sustainable development as core objectives, comprehensively consider scope delineation, style control and construction guidelines. In addition, they define the protection scope, covering the core preservation area, and provide control guidance to visual corridors, buildings and street spaces in order to maintain the original flavor of the village. At the same time, China has compiled guidelines and plans for the construction of traditional villages to regulate new construction and restoration projects and provide a basis for the construction and renovation of traditional village buildings.

In Italy, GAL-led and top-down guidelines, highly refined heritage protection and rural building renewal management regulations have contributed to the fundamentals of rural built heritage protection. The Law of Bugarosi promulgated in 1977 distinguished property rights from construction rights and introduced the concept of construction permit, which stipulated that when assessing rural construction needs, the owner must pay a concession fee to the government and must complete the construction under specified conditions. In addition, owners are required an urbanization tax arising from the conversion of building functions, such as those transforming land use from agriculture to residential, industrial or tertiary industries, and other related activities that result in the consumption of nearby infrastructure and village management costs [

14].

2.3. Different Emphasis on Preservation and Revitalization

There are significant differences between China and Italy in how they approach the preservation of materials and construction techniques. Traditional Chinese villages often use materials such as wood, brick, and stone that are deeply rooted in regional traditions. However, in recent years, many new buildings have emerged in some villages under the pressure of modernization. These buildings conflict with traditional architectural features, posing challenges to the integrity of heritage preservation. The renewal of traditional villages in China generally focuses on the restoration of historic buildings and the preservation of their characteristics, with the government playing an important role in projects promotion and implementation. However, commercial and tourism development often conflicts with the preservation of cultural heritage.

On the contrary, traditional village buildings in Italy are dominated by materials such as stone, brick and lime, which have a deep historical background and artistic value. Italy began protecting traditional buildings earlier, tends to maintain integrity and emphasizes restoration and protection of historical buildings [

15].

Italy pays more attention to the active utilization of cultural heritage. Village protection is often accompanied by community participation and the efforts of non-governmental organizations to encourage the transformation of ancient buildings into cultural centers, art workshops, homestays, etc., thus realizing the harmonious integration of tradition and modernity. The differences between these two approaches reflect the cultural, social and economic backgrounds of the two countries, and provide useful references for other countries in the protection and activation of traditional villages.

There are obvious differences between China and Italy in the development direction of cultural tourism in traditional villages. Chinese traditional village cultural tourism often emphasizes the display and preservation of history and culture, allowing tourists to appreciate ancient buildings, traditional crafts, and rural customs. The government usually attracts tourists through scenic area planning and marketing promotion, aiming to boost local economic development. However, this approach may lead to over-commercialization of some villages, harming the original lifestyle and community environment [

16].

In contrast, traditional Italian village cultural tourism puts more emphasis on a comprehensive experience, combining elements such as culture, art and cuisine, and emphasizing the interaction between tourists and the local community. Traditional villages in Italy usually set up cultural activities, handicraft markets and art exhibitions, so that tourists can participate deeply in the local life. This model focuses more on community participation and the preservation of local identity, which contributes to the sustainable development of cultural tourism.

There are some differences between China and Italy in the protection of ecological background in traditional villages. In China, due to rapid urbanization and economic development, some traditional villages face environmental pressure, including land development, pollution and other problems. Although the Chinese government has stepped up its efforts in environmental protection in recent years and promoted the creation of ecological consciousness in some places, ecological damage can still occur in some traditional villages, especially when tourism development and commercialization have excessive environmental impacts [

17].

In contrast, Italy usually pays more attention to ecological and environmental protection. Traditional villages in Italy are often located in areas with beautiful natural scenery, and the government and communities usually take measures to protect the natural environment from overdevelopment and pollution [

18]. In addition, some Italian traditional villages use ecological environment protection as one of the selling points to attract tourists, advocating sustainable tourism and cultural activities to protect the environment and preserve local identity.

As shown in

Table 2, Italy has a relatively mature protection system for traditional villages, with regulations like the Bugarosi Law that emphasize the organic integration of cultural heritage and the environment. These efforts have led to the inclusion of traditional villages in the national park system, enhancing cultural tourism and sustainable development [

19]. Meanwhile, China, in the context of rapid urbanization, is gradually establishing a similar system and shifting from government-led initiatives toward multi-stakeholder participation. This includes activating traditional villages through cultural and creative industries and moving toward comprehensive and sustainable development that involves community participation and empowers villagers as key agents of preservation [

5,

20].

3. Comparison of Case Studies on the Preservation and Revitalization of Traditional Villages in China and Italy

The geographical locations of both Jiande County, Hangzhou in China and the Cinque Terre in Italy are in the coastal areas of their respective countries (

Figure 4). Both are mountainous regions featuring villages with rich heritage, thriving tourism, and a prosperous economy. In both areas, traditional villages are concentrated and contiguous. Therefore, this study selects two representative places for comparative analysis. In Hangzhou, the government has delineated the core protected area with a red line and implemented single-village protection from the top down. In the Cinque Terre, the protection and revitalization of the villages are led by the government, residents, universities, research institutions, and cooperatives, combining top-down and bottom-up approaches, thereby highlighting the conceptual differences in the protection and revitalization of traditional villages between the East and the West. In the context of global connectivity, conducting a comparative study of these two representative cases is helpful in identifying the differences and providing meaningful references for the protection of traditional villages worldwide.

To systematically compare the preservation and revitalization strategies of China’s Jiande cluster and Italy’s Cinque Terre, Phase II of the study adopted a mixed-methods approach. This included fieldwork involving questionnaires and interviews, as well as a GIS-based (Arc GIS 10.1) spatial analysis using indicators such as landscape continuity and ecological corridor connectivity.

A seven-dimensional 5-point Likert scale was devised to assess the following key aspects: heritage integrity, ecological health, native experience, economic benefits, tourism coherence, environmental comfort, participatory governance; this metric was developed and weighted using the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) to generate cross-case preservation scores. The questionnaire featured 22 targeted perception items aligned with these key aspects (

Table 3). After undergoing back translation and review, the instrument was finalized and field-tested.

According to the 5-point Likert scale, respondents rate each statement from 1 (strongly disagree/very poor) to 5 (strongly agree/excellent), resulting in ordinal data treated as an interval-level scale for analysis. A total of 600 surveys were administered (300 for each case study), yielding 578 valid responses (96.3%). Simultaneously, 68 interviews were conducted and transcribed verbatim to contextualize the quantitative findings. These included interviews averaging 52 min with 12 government officials, 24 local residents, 18 businesspeople, and 14 tourists.

This study employed the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP), developed by Thomas L. Saaty [

21], to generate a pairwise comparison matrix for the seven selected factors, using a scoring scale from 1 to 9 (see

Table 4). The relative importance of each factor was determined by calculating a priority vector (Eigenvector), which was then applied in the overall scoring process. Based on the results presented in

Table 4, the assigned weights for each factor are as follows: heritage integrity (0.235), ecological health (0.178), native experience (0.153), economic benefits (0.143), tourism coherence (0.101), environmental comfort (0.095), and participatory governance (0.095).

The Consistency Ratio (CR) evaluates the logical coherence of pairwise comparisons. It is calculated by dividing the Consistency Index (CI), obtained through the eigenvalue method, by the Random Index (RI). In this matrix, the CR value is 0.03, which is below the 0.10 threshold, indicating that the judgments are consistent.

According to

Table 5, Cinque Terre significantly outperforms Jiande in terms of ecological protection, heritage preservation, tourism continuity, and the richness of the tourist experience. These differences are closely linked to the distinct preservation and development strategies implemented by each country.

As illustrated in

Figure 5, GIS-based analysis of spatial fabric continuity indicates that Jiande’s villages follow a three-zone protection model, spaced approximately 8 km apart. These settlements are loosely connected, with minimal industrial linkage along County Road X08 in the central basin. Mountain villages located above the 380 m elevation show a high fragmentation index of 0.73 and lack coordination across settlements. In contrast, Cinque Terre’s five villages are situated along a compact 1.2 km coastal strip within a unified national park boundary. This area seamlessly integrates a 350 m elevation range using footpaths, cableways, and ferries. With a continuity index of 0.91, the region supports smooth ecological, economic, and tourism flows along the 8 km coastal corridor, highlighting the spatial and functional benefits of contiguous protection within a national park framework.

3.1. Jiande Traditional Villages in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China

The planning process for preserving and revitalizing traditional Chinese villages begins with regional-level decisions to protect vernacular landscapes, which then guide specific actions at the village level. Based on the closed-loop framework of the Traditional Chinese Village Protection and Utilization Model illustrated in

Figure 6, the planning process begins with a comprehensive five-dimensional survey, encompassing field investigations, natural resources, historical culture, socio-economic conditions, and land use. Each asset is evaluated for its significance, leading to the creation of parallel dataset: Conservation Inventory and a Utilization Inventory. These inventories are then formalized into statutory plans during the Planning and Approval stage.

China’s preservation plans still focus on single-village conservation efforts, spotlighting material heritage such as historic layouts, public spaces, and vernacular buildings, yet they lack contiguous, regional mechanisms, spawning isolated, redundant projects and rampant homogenization. Without broad social participation, state-led development breeds top-down commercialization, displacing residents and diluting authenticity.

Top-down systems are often criticized: they rely on centralized government decisions, which can quickly complete infrastructure renovations in the short term, but also lead to fragmentation and homogeneity issues. Lin Tian and Yao Cheng (2025) warn that it yields a fragmented, monotonous landscape [

22], while TUM (2023) finds villages spatially and administratively disconnected, forming a homogeneous peri-urban mosaic [

23]. Meiqi Wang (2023) claims that state-mandated, village-by-village redevelopment and forced commercialization displace indigenous residents [

24].

In Xinye, located in southeastern Jiande County, Hangzhou authorities have established strict zoning, including a vivid scarlet-red core zone representing the highest level of protection, surrounded by a pale orange buffer area and a light gray construction control zone. The internal layout and pathways are shown in

Figure 7. Each village functions as an isolated unit, regulated by its own township rules and enclosed within fixed boundaries marked in red, orange, and gray, effectively isolating it from neighboring settlements and the wider landscape. This results in a fragmented and repetitive settlement network lacking regional cohesion.

The planning map reveals that Jiande employs a ‘one plan per village’ unit protection strategy: while top-down administrative directives enable rapid restoration of cultural relics and infrastructure improvements, the overlap between conservation zones and village administrative boundaries fractures traditional layouts into isolated attractions. This fragmentation impedes cross-village integration, resource sharing, and brand collaboration. As the project enters its operational phase, government funding diminishes, and social investments decline due to long return periods and complex, divided property rights. Villagers face a lack of formalized benefit-sharing mechanisms and decision-making opportunities, leading to low community involvement. Consequently, significant maintenance funding shortfalls and uniform business models emerge, obstructing effective preservation and revitalization.

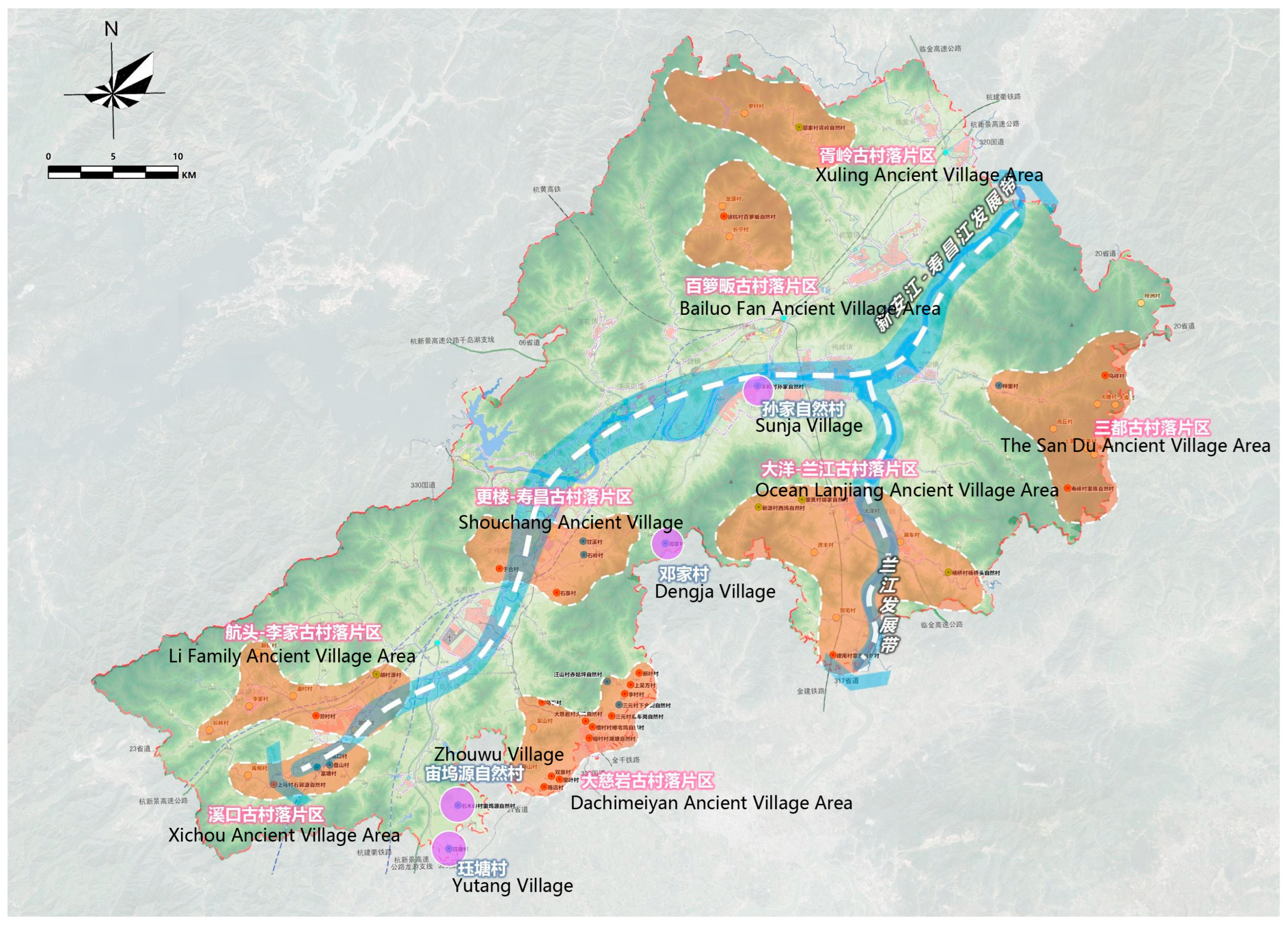

In May 2023, for the first time, City of Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, lead the release of the Demonstration Work Plan for the Concentrated and Continuous Protection and Utilization of Traditional Villages in Jiande County, which covers the overall protection and development planning of 36 traditional villages. Jiande County is located in western Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, at the upper reaches of the Qiantang River, with a history of nearly 1800 years. It was the former capital of ancient Muzhou and Yanzhou prefectures and is renowned for its beautiful natural scenery and rich historical and cultural relics as shown in

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10. The plan emphasizes promoting the cultural heritage preservation and sustainable development of traditional villages through innovative methods of revitalizing traditional buildings and improving preservation mechanisms. [

25].

The plan aims to systematically protect, revitalize, and sustainably develop traditional villages in Jiande County, creating a rural revitalization model. The plan proposes a one belt, eight areas, multiple points layout (

Figure 11), focusing on eight traditional village areas guided by differentiated development. It integrates resources, undertakes collective construction, and promotes coordinated development. The one belt highlights ancient Jiazhou culture along the New Anhui River, Shouchang River, and Lan River. The eight areas promote rural revitalization through coordinated development. The plan centers on people, coordinates infrastructure and public services, and efficiently protects and utilizes cultural resources.

However, this work plan is merely an experimental stage and has not yet been transformed into a formally issued legal document. Most traditional villages remain independent and difficult to interconnect. The integrated preservation and revitalization of traditional villages is still in the trial stage.

3.2. The Cinque Terre National Park in Italy

The protection and utilization of traditional villages in Italy is undergoing a series of changes, from protecting individual villages to utilizing the whole, and from individual management to the operation and management of scenic spots. Meanwhile, significant progress has been achieved in developing integrated national parks that promote harmony between nature and human activity.

First of all, the focus of protection and utilization extends from a single village to the whole contiguous area. Many traditional villages in Italy have unique geographical, historical and cultural connections with each other, gradually forming a continuous cultural heritage network. In order to better protect and inherit these cultural treasures, Italy began to include multiple villages as a whole in the scope of preservation and revitalization and promote the sustainable development of the whole contiguous village area through joint development and resource sharing [

26].

Secondly, there is a change from individual business to scenic operation and management. In order to better attract tourists and provide a richer experience, Italian traditional villages gradually turn to the operation and management of scenic spots. This involves the construction of standardized tourism facilities, guided tour services, cultural activities, etc., to meet the needs of different tourists, while also injecting new economic vitality into the villages.

At the same time, Italy is also promoting the construction of national parks where traditional villages that coexist with nature. Many traditional villages are located in beautiful natural environments, and in order to realize the common protection of natural resources and cultural heritage, traditional villages are included in the national park management system. This model not only emphasizes the protection of natural ecology but also pays attention to the inheritance of human history, and promotes the sustainable development of villages and the natural environment through ecotourism and other means [

27]. These trends contribute to better preserving and passing on Italy’s rich cultural heritage, while also injecting new vitality into tourism and sustainable development.

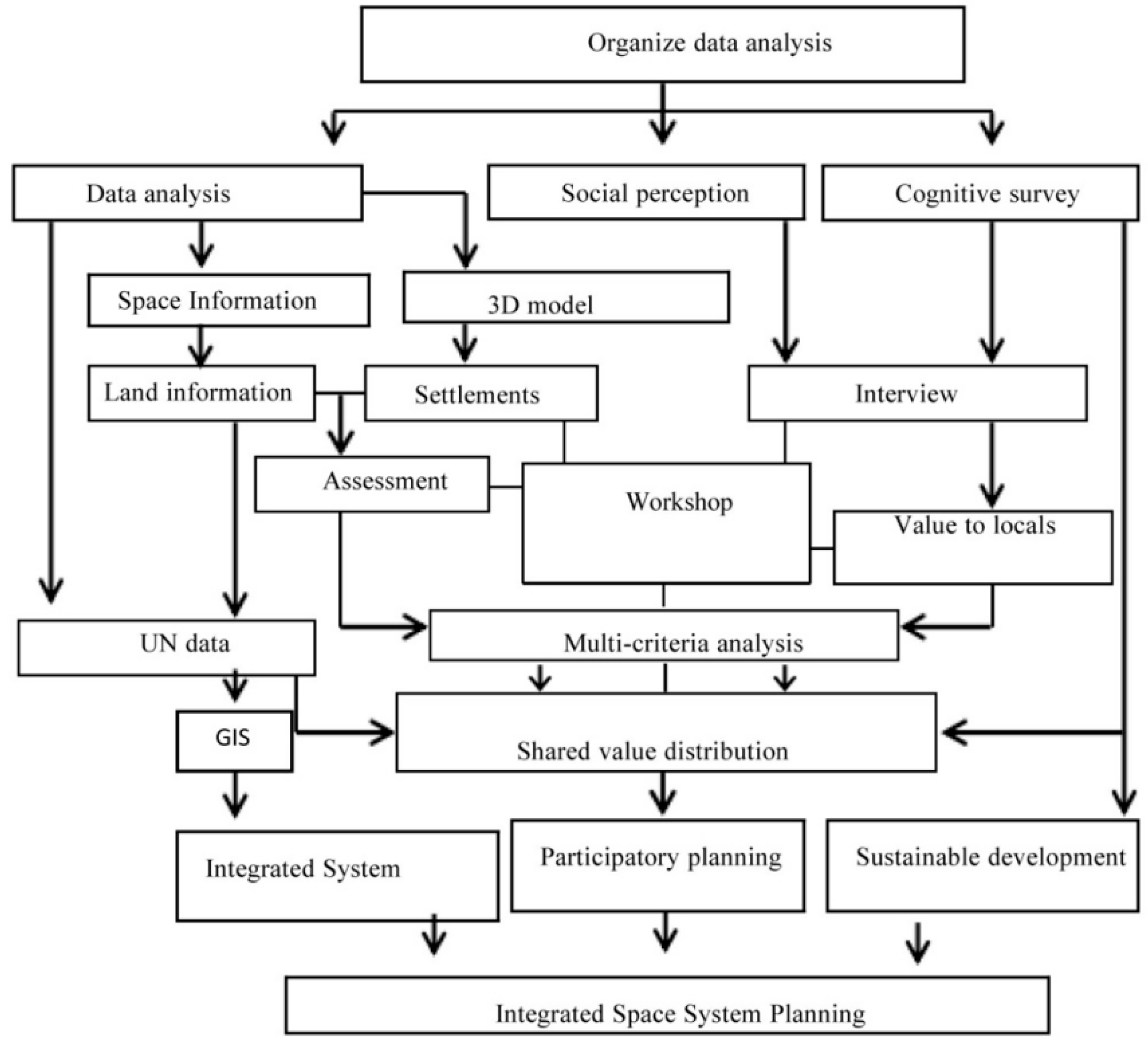

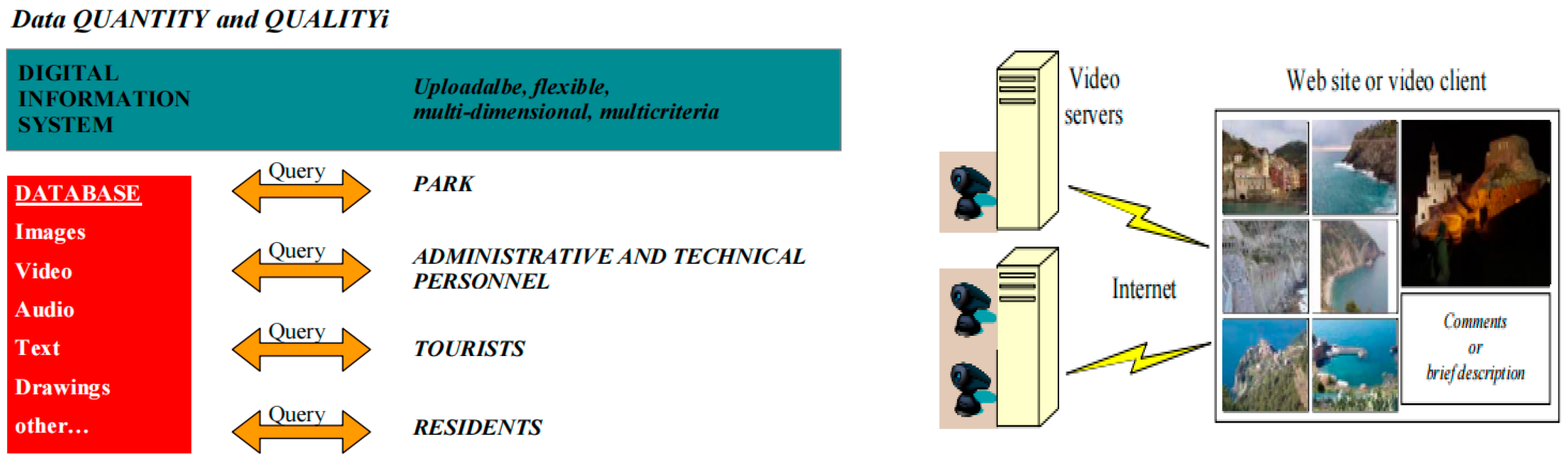

The Cinque Terre National Park in Italy, which is included in the UNESCO World Heritage list, is a representative example of the integration of traditional villages into national parks. While protecting traditional architecture and culture, Cinque Terre emphasizes tourism development, achieving a harmonious integration of preservation and sustainable development. Over the years, Italy has protected the five traditional villages and the rich heritage around them, and has tried to combine protection with sustainable development, making full use of their rich natural resources, developing eco-tourism, and attracting tourists to hike, swim and watch birds here, which has achieved sustainable development of tourism. In addition, the protection and development work of Cinque Terre villages has had wide participation by the community, and the villagers actively participate in the restoration of traditional buildings and the inheritance of culture, which has improved the effectiveness and efficiency of the protection work. To this end, the European Community initiated a planning study on Conservation and Utilization of Cinque Terre National Park, which was included in the EU’s financial assistance Culture 2000 program, to provide ideas for analysis, intervention and management of Cinque Terre National Park through cooperation between transnational creatives, cultural operators and cultural organizations. The professional team adopted methods such as data analysis, social perception and visitor survey, used spatial information systems and site models to conduct dynamic assessment and analysis of the site, and organized extensive participation of people from all walks of life to allocate shared values, and put forward scientific and reasonable spatial system plans for the preservation and revitalization of Cinque Terre [

28]. Italy integrates land information, settlement data and shared values through digital models, GIS and multi-criteria analysis. It conducts workshops, interviews and evaluations to promote community participation, and formulates sustainable spatial planning systems for traditional villages (

Figure 12).

The comprehensive preservation and revitalization plan of Cinque Terre National Park puts forward the overall goal of cultural identity protection in functional evolution, and proposes three major indicators: land protection, land quality and use, and sustainable tourism [

28]. In terms of protection, the plan proposes forward the overall protection of traditional villages, ecological corridors, terraces and coastlines, and provides detailed guidance methods. The plan proposes to build a park observation platform and tourism experience landscape, construct cultural activity facilities to organize meetings and research activities, carry out local markets and festivals, develop online and offline platform for land, traditional culture, agriculture and marine research museums, set up laboratories for various kinds of cuisine, wine, seafood and fish products, and inherit local artisans and architectural skills [

24]. It also aims to carry out various large-scale international ecological protection seminars and conferences, add more attractive and functional scenic spots, and successfully build itself into a well-known tourist destination through targeted brand building and marketing promotion.

3.2.1. Spatial Integration and Planning

Overall planning framework: Cinque Terre adopts a spatial structure of one belt (coastal railway), eight patches (five villages + three sacred sites), and multiple points (terraces, ancient roads) to integrate the villages, terraces, and marine ecosystems within a unified control boundary, forming an ecological-cultural continuum. This planning approach ensures the organic integration of cultural heritage and natural landscapes and addresses the fragmentation problem [

27].

Heritage Corridor Construction: Cinque Terre National Park is connected through the coastal railway and trails, forming a heritage corridor. This not only facilitates tourist visits but also promotes transportation and communication within the region, as shown in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14.

Cinque Terre has incorporated the villages, terraces, and the coastline into the unified national park planning boundary, forming an ecological–cultural continuum. Relying on the coastal railway, the blue trail, and the 120 km ridge highline trail (Sentiero del Crinale), a “sea–village–mountain” three-dimensional heritage corridor has been constructed. In addition, package tickets and themed tour routes have been launched to facilitate integrated transportation and overall operation of the scenic area, effectively avoiding the problems of fragmented development and isolated attractions.

3.2.2. Operating Mechanism

Dual Governance Structure: The National Park Company (Parco Nazionale) is responsible for the brand, infrastructure, and visitor capacity control (with a maximum of 30,000 visitors per day), while the village collective cooperatives (such as the Cinque Terre Card system in Manarola) operate specific business models like guesthouses and vineyard tours. The profits are distributed according to the 51% for villagers and 49% for the company’s reinvestment ratio, ensuring that tourism benefits support the maintenance of the heritage.

Community Leadership and Participation: The village collective cooperatives play a leading role in the operational process, ensuring that villagers can directly participate and benefit from tourism development, thereby enhancing the cohesion and conservation awareness of the community.

3.2.3. Dynamic Management and Monitoring

GIS Monitoring System: Based on the GIS tourist heat map and terraced field monitoring procedure, the system provides real-time warnings of landslide risks to ensure the safety of cultural heritage and environment (

Figure 15 and

Figure 16).

Technical Alliance Support: The EU Culture 2000 technical alliance provides annual restoration plans to ensure the sustainable protection of cultural heritage.

3.2.4. Cultural IP and Event Planning

Four Seasons Events: The Via dei Santuari connects the five villages. Spring events such as Grapevine Pruning Festival and autumn events like Sciacchetra Wine Festival are all integrated with the National Park Passport Stamp Collection System, enhancing tourists’ cultural experience and sense of identity.

4. Conclusions

Considering the differing historical backgrounds and sociocultural contexts of China and Italy, the exchange of experiences in preserving and revitalizing traditional villages must be carefully adapted to each specific setting. It is important to note that since being designated a World Heritage Site in 1997, Cinque Terre has followed a cohesive approach combining protection, gradual development, and benefit-sharing through the national park system, community cooperatives, and varied funding sources. By contrast, Chinese villages continue to operate within a governance model centered on isolated projects, marked by fragmented initiatives and disconnected communities.

In order to identify strategies and experiences suitable for adaptation in the Chinese context, seven key factors were selected and a comparative matrix was created, incorporating the institutional gaps and performance differences identified in Phases 1 and 2 (see

Table 6).

As outlined in

Table 6, the comparison matrix reveals institutional gaps and performance variations across seven key dimensions. Funds and ecotourism received four stars because China already has some national park pilot projects and urban investment platforms capable of quickly adopting EU-style visitor flow controls and reservation systems. The primary challenge lies in establishing transparent trust frameworks and tax-incentive measures to attract private investment instead of relying solely on government grants. Planning tools and regulatory policies received three stars because university-community micro-guidelines can be incorporated into existing village master plans, but this depends on consolidating multi-level laws into a standardized minimum intervention code. Participation and cultural revitalization also received three stars; the workshop consensus suggests that resident cooperatives could be initiated by current village committees, though sustained capacity building is necessary to empower villagers to move from passive recipients of information to active joint decision-makers.

Based on these findings, we propose the following integrated policy package aimed at translating the Cinque Terre experience into practical strategies for China, facilitating a transition from isolated projects to continuous, landscape-scale preservation and revitalization.

-Regulatory and Institutional Chain. Cinque Terre’s single Unified Law on Cultural and Landscape Protection secures horizontal and vertical integration, whereas China’s multi-tier regulations are fragmented. We recommend county-level Traditional Villages Conservation and Development Ordinances that empower village councils through negative-list authorization, embedding Italy’s community co-governance into grassroots administration.

-Capital and Risk Chain. Cinque Terre leverages EU funds, social-impact bonds, and cooperative shares to share risks and returns. China can adopt a junior-senior tranche design: government seed capital as junior, with Internet philanthropy, industrial funds, and REITs as senior, distributing pro-rata dividends to village collectives to leverage finance while easing fiscal stress.

-Technology and Knowledge Chain. Cinque Terre’s GAL and universities run mobile laboratories and digital-twin platforms for real-time monitoring and craftsman training. China could establish a cross-provincial Traditional Villages Technology Alliance that delivers standardized modules for surveying, restoration and operation, overcoming local shortages of know-how and standards.

-Culture and Social Chain. Italy converts everyday life into tourism experiences, whereas China often falls into staged authenticity. Future programs can revolve around the 24 Solar Terms, intangible skills and oral histories, creating year-round immersive festivals activated by crowdfunding and digital interaction to achieve culture as life rather than culture as performance.

-Spatial and Ecological Chain. Cinque Terre knits scattered settlements, terraces, and ancient paths into a continuous national-park landscape. China could pilot a Traditional Villages National Park Cluster, using ancient roads, waterways, and tea mountains as corridors under unified branding and capacity control, shifting from site-based to regional living-landscape conservation.

In summary, this paper presents a three-phase, mixed-method framework that adapts Italy’s heritage-village experience to China’s governance context, providing a novel and meaningful contribution to the field of cross-border policy transfer. The transferable core, codified in the chain integration package, nevertheless rests on only two cases. Further research involving multiple case studies across the Yangtze Delta and the Mediterranean is needed to validate its replicability and long-term sustainability.