Eye-Tracking Advancements in Architecture: A Review of Recent Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

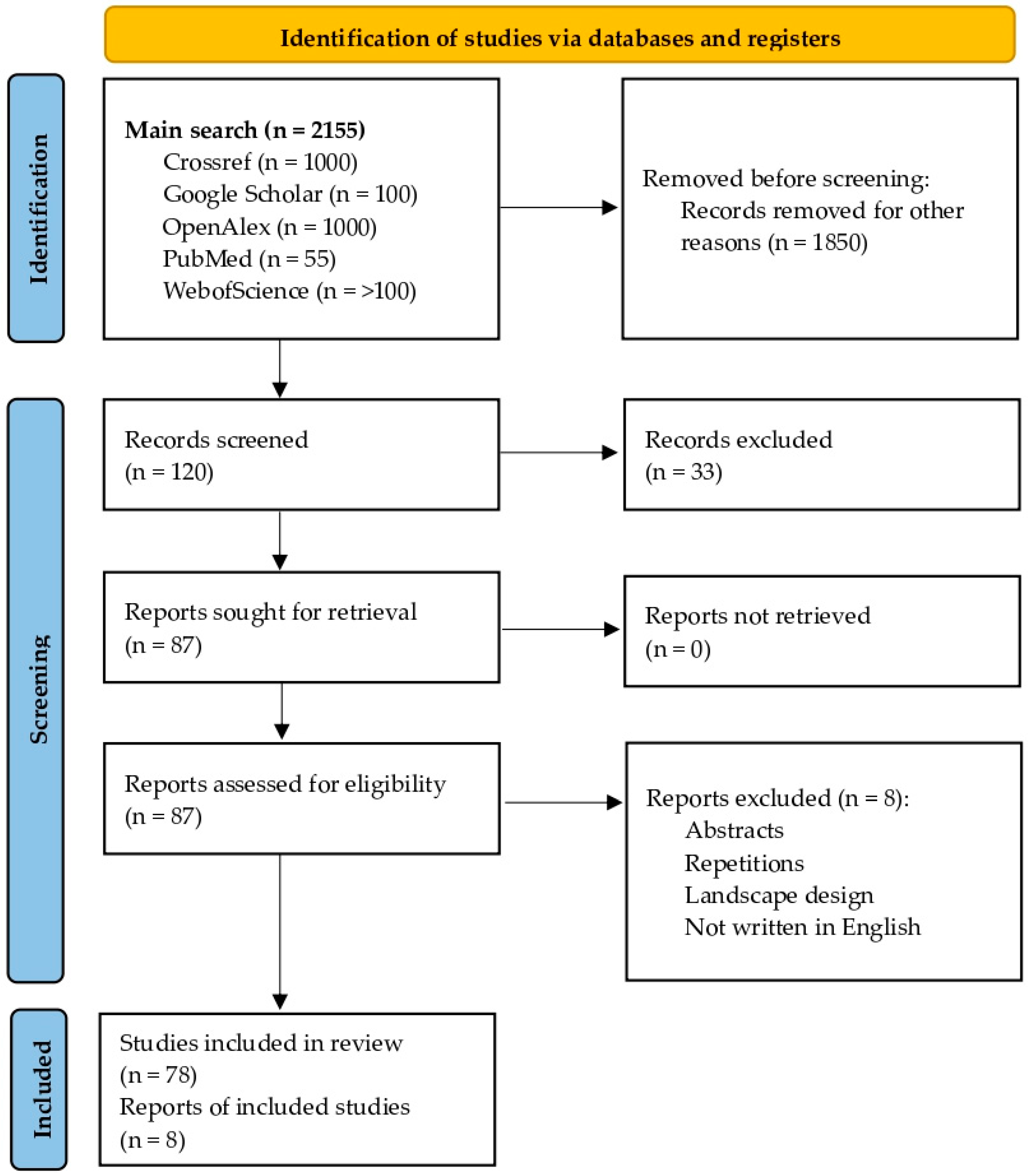

1.1. Literature Search Strategy

- Publication in English.

- Full articles.

- Published in relevant scientific journals or conference proceedings.

- Published after 2010 and before 2024.

- Mentioning both “architecture” and “eye tracking”.

- Not being written in English.

- Being just abstracts.

- Not referring to architecture.

- Repetitions.

- Title.

- Abstract, highlights, and article aim.

- Concept(s) highlighted in the article (when existent).

- Research question(s) (when existent).

- Conclusion.

- Main article.

- Images, graphic(s), and table(s).

(“architect*” OR “architecture student*” OR “design professional*” OR “built environment researcher*”)AND(“eye-tracking” OR “eye tracking” OR “eye movement” OR “visual attention” OR “gaze tracking”)AND(“visual perception” OR “spatial navigation” OR “wayfinding” OR “design evaluation” OR “user experience” OR “architectural education” OR “design analysis”).

1.2. Evolution of Eye-Tracking

1.3. The Human Visual System

1.4. Types of Eye-Trackers

1.5. The Importance of Studying Visual Perception in Architecture

1.6. Eye-Tracking Architectural Applications, History, and Future Perspectives

- Use of VR to systematically verify designs in development to ensure that the gaze patterns of the users match what we want to be read in an architectonic context.

- Develop ET methodology, methods, and triangulation to deal with the complexity or in situ experiments.

- Further develop best practices for laboratory-based experiments.

- Use of replication and verification studies on analysis of gaze differences between architects and non-architects, on the relationship between gaze patterns and preferences, and on the role of individual building elements in attracting the gaze.

- Developing further new and rapid approaches such as visual attention software (VAS).

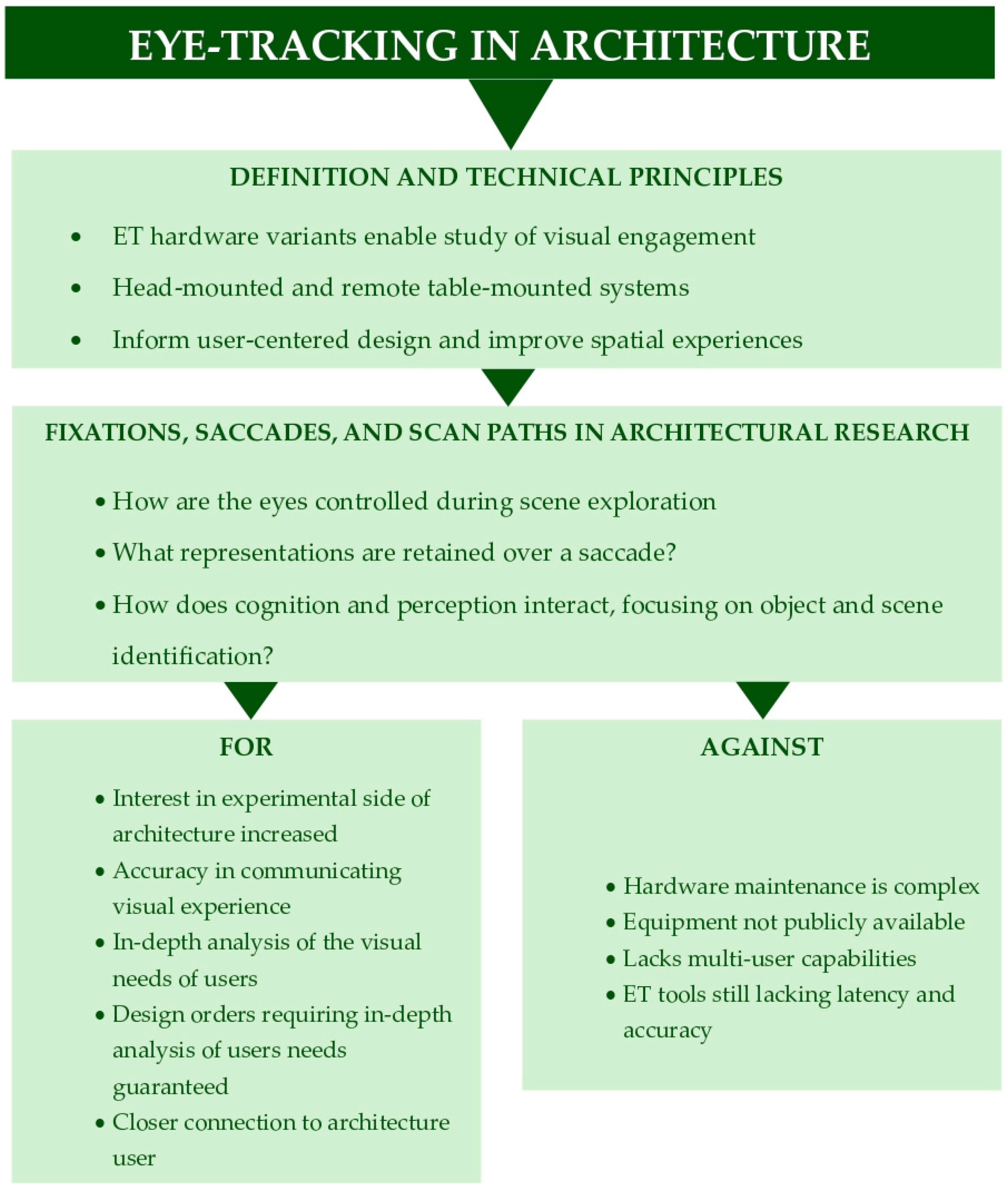

2. Understanding Eye-Tracking in Architecture

2.1. Use and Technical Principles

2.2. Fixations, Saccades, and Scan Paths in Architecture

2.3. Advantages and Limitations of the Use of Eye-Tracking in Architecture

- The interest in the experimental side of architectural research is increased.

- ET provides a graphically and numerically accurate communication of viewer experience.

- The acceptance of design orders which require in-depth analysis of the visual needs of the users is further guaranteed.

- The architectural importance of visual perception and of proximity to users are highlighted.

- Maintenance and conservation of ET hardware is complex.

- ET equipment is not available for public use.

- ET devices are for only one user at a time.

- ET tools often still lack latency and accuracy.

- Interpretations of gaze behaviors, fixations, and scan paths might not provide direct information on the brain activities (e.g., emotion, cognition, and attention) of the subject; found in the article by [46].

- Some studies used pupil size as an indicator of emotional state. “However, the pupil size and emotional arousal relationship was complex, and the pupil size was also influenced by other factors such as cognitive processing load” [45]; found in the articles by [51,52,53,54]. Factors like “light quantity and contrast” also influence pupil size [45]; found in the articles by [55,56].

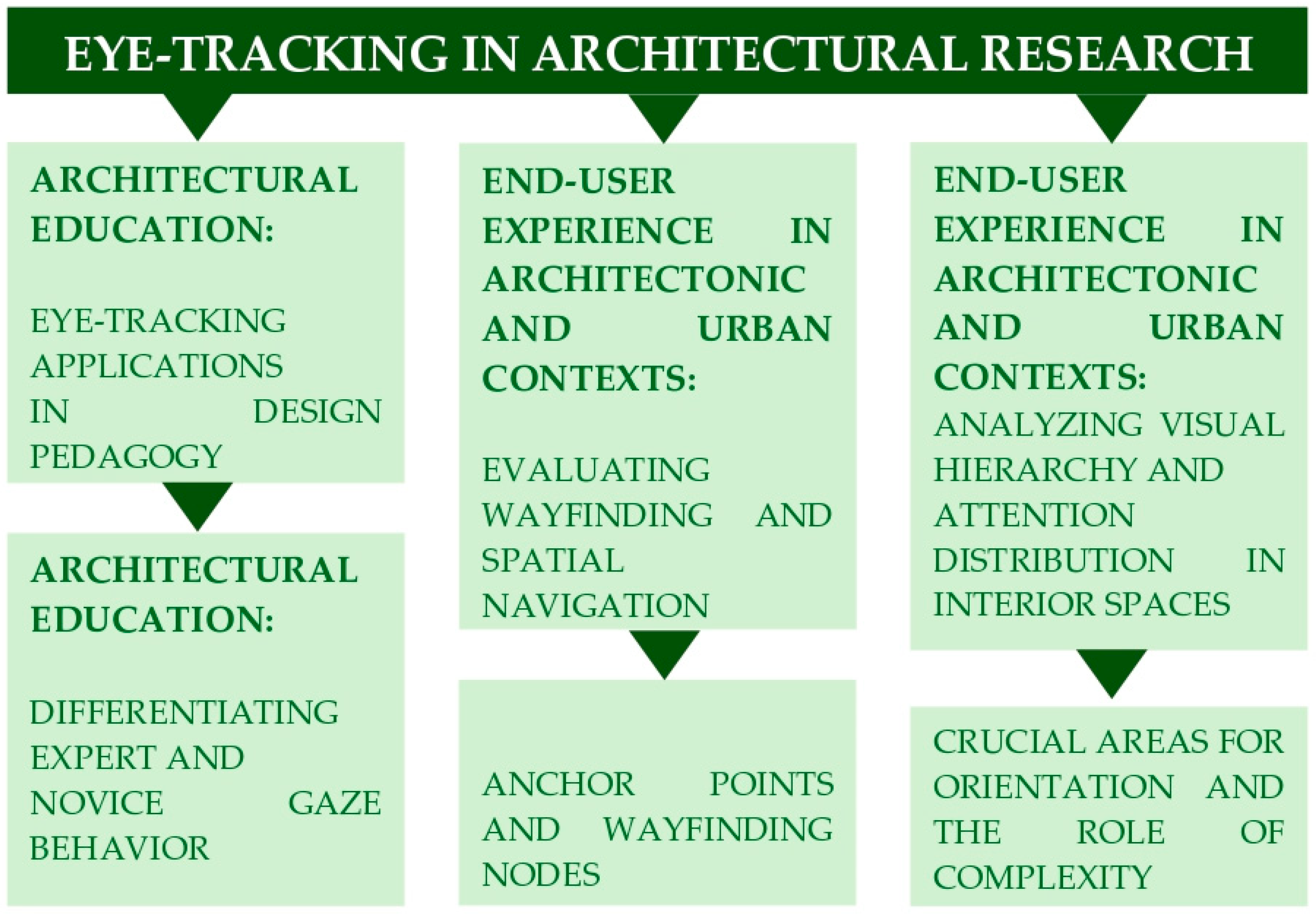

3. Role of Eye-Tracking in Architectural Education and Research

3.1. Eye-Tracking Applications in Architecture Design Pedagogy

- It is an inventive technique to guide the attention of future architects to the topic of order in architecture and urban planning, broadening their knowledge on the perception of architecture, i.e., how to attract the gaze of the users of architecture through design, while at the same time appropriately inscribing the project of someone in the natural or historical context.

- Increases the interest of students in the experimental side of research in architecture, which may lead to solving architectural projects with more creativity.

- Broadens the social and technological skills of students, which may facilitate their future acceptance of non-standard and complex architectural project orders that require in-depth analysis of the visual requirements of the users, as well as interdisciplinary cooperation.

- Self-monitoring of both teachers and students.

- Positively influences student–teacher working relationships, which may facilitate progress to advanced studies, e.g., master’s and doctorates.

- Promotes the academic institution, distinguishing it from other research centers, both due to these advanced technological solutions and by adjusting learning requirements to real needs of the users.

- Educates the architectural public by interesting them in the buildings they see day-to-day and promoting the profession of architects.

- High cost of ET purchases, maintenance, conservation, and insurance.

- Necessity of a room for use for up to 12 persons and, depending on the experience desired, possibly a laboratory.

- Teachers may contest the legitimate use of ET for self-analysis, as it requires adding work hours and extra effort as well as an open-minded and self-critical approach.

- Classes need to be held in-person to manipulate ET, which would be impossible under exceptional conditions like COVID.

3.2. Differentiating Expert and Novice Gaze Behavior in Architectural Education

3.3. Evaluating Wayfinding and Spatial Navigation in Architectural Research

3.4. Analyzing Visual Hierarchy and Attention Distribution in Interior Spaces in End-User Experience Research

4. Discussion

Challenges and Gaps

5. Guidelines for Education and Field Use of Eye-Tracking in Architecture

5.1. Best Practices for Using Eye-Tracking in Architecture Education

5.2. Checklist for Conducting In Situ Eye-Tracking Studies in Architecture

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ET | Eye-tracking |

| ScR | Scoping Review |

| ScS | Scoping Study |

| SR | Systematic Review |

| LR | Literature Review |

| GenAI | Generative artificial intelligence |

| UX | User experience |

| HVS | Human Visual System |

| ms | Milliseconds |

| VAS | Visual Attention Software |

| fMRI | Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| AR | Augmented reality |

References

- Duchowski, A.T. Eye Tracking Methodology: Theory and Practice; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Holmqvist, K.; Andersson, R. Eye Tracking, a Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Paradigms and Measures, 2nd ed.; Lund Eye-Tracking Research Institute: Lund, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2007, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalto, P.; Steinert, M. Emergence of eye-tracking in architectural research: A review of studies 1976–2021. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2004, 68, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartanian, O.; Navarrete, G.; Chatterjee, A.; Fich, L.B.; Gonzalez-Mora, J.L.; Leder, H.; Skov, M. Architectural design and the brain: Effects of ceiling height and perceived enclosure on beauty judgements and approach-avoidance decisions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 41, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojko, A. Eye Tracking the User Experience: A Practical Guide to Research; Rosenfeld Media: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Duchowski, A.T. A breadth-first survey of eye-tracking applications. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2002, 34, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, K. Eye movements in reading and information processing: 20 years of research. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 124, 372–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, A.; Ball, L.J. Eye Tracking in HCI and Usability Research. In Encyclopedia of Human Computer Interaction; Ghaoui, C., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, D.A. The oculomotor control system: A review. Proc. IEEE 1968, 56, 1032–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Conde, S.; Macnick, S.L.; Hubel, D.H. The role of fixational eye movements in visual perception. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, J.M.; Franz, G. Isovists as a Means to Predict Spatial Experience and Behavior. In Spatial Cognition IV. Reasoning, Action, Interaction. Spatial Cognition 2004; Freksa, C., Knauff, M., Krieg-Brückner, B., Nebel, B., Barkowsky, T., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Volume 3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, M. Effects of familiarity and plan complexity in wayfinding in simulated buildings. J. Environ. Psychol. 1992, 12, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, J. The Experience of Landscape; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Buswell, G.T. How People Look at Pictures: A Study of the Psychology and Perception in Art; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Yarbus, A.L. Eye Movements and Vision; Riggs, L.A., Ed.; Haigh, B., Translator; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Janssens, J. Hur man betraktar och identifierar byggnadsexteriörer: Metodstudie. In How People See and Indentify Building Exteriors—A Method Study; Tekniska Högskolan i Lund, Sektionen för Arkitektur; Tekniska Högskolan i Lund: Lund, Sweden, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Janssens, J. Skillnader mellan arkitekter och lekmän vid betraktande av byggnadsexteriörer. In The Effect of Professional Education and Experience on the Perception of Building Exteriors; Tekniska Högskolan i Lund, Sektionen för Arkitektur; Tekniska Högskolan i Lund: Lund, Sweden, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, R.; Choi, Y.; Stark, L. The impact of formal properties on eye movement during the perception of architecture. ACSA Eur. Conf. Lisbon Hist. Theory Crit. 1995, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulsham, T.; Walker, E.; Kingstone, A. The where, what and when of gaze allocation in the lab and the natural environment. Vis. Res. 2011, 51, 1920–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayegh, A.; Andreani, S.; Li, L.; Rudin, J.; Yan, X. A new method for spatial analysis: Measuring gaze, attention, and memory in the built environment. In Proceedings of the 1st International ACM SIGSPATIAL Workshop on Smart Cities and Urban Analytics—UrbanGIS’15, Bellevue, WA, USA, 3–6 November 2015; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noland, R.B.; Weiner, M.D.; Gao, D.; Cook, M.P.; Nelessen, A. Eye-tracking technology, visual preference surveys, and urban design: Preliminary evidence of an effective methodology. J. Urban. 2017, 10, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisińska-Kuśnierz, M.; Krupa, M. Eye -tracking in research on perception of objects and spaces. Archit. Urban Plan. 2018, 12, 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lisińska-Kuśnierz, M.; Krupa, M. Suitability of eye-tracking in assessing visual perception in architecture—A case study concerning selected projects located in Cologne. Buildings 2020, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, J.; Cho, J.Y. A triangular relationship of visual attention, spatial ability and creative performance in spatial design: An exploratory case study. J. Inter. Des. 2021, 46, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabaja, B.; Kupa, M. Possibilities of using the eye tracking method for research on the historic architectonic space in the context of its perception users. Wiadomości Konserw.-J. Herit. Conserv. 2017, 52, 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Rusnak, M.A.; Rabiega, M. The potential of using an eye tracker in architectural education: Three perspectives for ordinary users, students and lecturers. Buildings 2021, 11, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M. Visual perception: Eye-tracking and real-time walk-throughs in architectural design. Int. J. Archit. Eng. Des. 2021, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Vainio, T.; Karppi, I.; Jokinen, A.; Leino, H. Towards novel urban planning methods—Using eye-tracking systems to understand human attention in urban environments. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Li, S.; Lin, Y.; Hu, W. From Visual Behavior to Signage Design: A Wayfinding Experiment with Eye-Tracking in Satellite Terminal of PVG Airport. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Computational Design and Robotic Fabrication (CDRF 2021), Shanghai, China, 26 June 2021; Yuan, P.F., Chai, H., Yan, C., Leach, N., Eds.; Springer Nature: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 252–262. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Z.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, B. Study on the influence of spatial attributes on passengers’ path selection at Fengtai high-speed railway station based on eye tracking. Buildings 2024, 14, 3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suurenbroek, F.; Spanjar, G. Neuro-Architecture: Designing High-Rise Cities at Eye Level; Nai010 Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, J.M.; Hollingworth, A. High-level scene perception. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1999, 50, 243–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marr, D. Vision: A Computational Investigation into the Human Representation and Processing of Visual Information; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman, S. High-Level Vision: Object Recognition and Visual Cognition; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Biederman, I.; Mezzanotte, R.J.; Rabinowitz, J.C. Scene perception: Detecting and judging objects undergoing relational violations. Cogn. Psychol. 1982, 14, 143–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyce, S.J.; Pollatsek, A.; Rayner, K. Effect of background information on object identification. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 1989, 15, 719–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingworth, A.; Henderson, J.M. Does a consistent scene facilitate object perception? J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1998, 127, 398–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, N.S.; Mohamed, E.H.; Abdoul, O.F. Using eye-tracking tools in the visual assessment of architecture. Eng. Res. J. 2022, 51, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotios, S.; Uttley, J.; Yang, B. Using eye-tracking to identify pedestrians’ critical visual tasks. Light. Res. Technol. 2015, 47, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Cinn, E. Using an eye tracker to study three-dimensional environmental aesthetics: The impact of architectural elements and educational training of viewers’ visual attention. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2015, 32, 145–167. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Jin, Y.; Ahn, S.; Lee, S. The impact of design representation on visual perception: Comparing eye-tracking data of architectural scenes between photography and line drawing. Arch. Des. Res. 2019, 32, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z. Where do we look? An eye-tracking study of architectural features in building design. In Proceedings of the 35th CIB W78 2018 Conference, Chicago, IL, USA, 1–3 October 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhipeng, L.; Pesarakli, H. Seeing is believing: Using eye-tracking devices in environmental research. Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2023, 16, 15–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuszynska-Bogucka, W.; Kwiatkowski, B.; Chmielewska, M.; Dzienkowski, M.; Kocki, W.; Pełka, J.; Przesmyckat, N.; Bogucki, J.; Galkowski, D. The effects of interior design on wellness—Eye tracking analysis in determining emotional experience of architectural space. A survey on a group of volunteers from the Lublin Region, Eastern Poland. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2020, 27, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrom-Feiertag, H.; Settgast, V.; Seer, S. Evaluation of indoor guidance systems using eye tracking in an immersive virtual environment. Spat. Cogn. Comput. 2017, 17, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, K.M.; Jacobs, R.A.; Tarduno, J.A.; Pelz, J.B. Collecting and analyzing eye tracking data in outdoor environments. J. Eye Mov. Res. 2012, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasi, M.; Pundlik, S.; Bowers, A.R.; Peli, E.; Luo, G. Mobile gaze tracking system for outdoor walking behavioral studies. J. Vis. 2016, 16, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Du, J.; Ragan, E. Review visual attention and spatial memory in building inspection: Toward a cognition-driven information system. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2020, 44, 101061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewski, W.X.; Muckschel, M.; Ziemssen, T.; Beste, C. The norepinephrine system affects specific neurophysiological subprocesses in the modulation of inhibitory control by working memory demands. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2017, 38, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gidlof, K.; Wallin, A.; Dewhurst, R.; Holmqvist, K. Using eye tracking to trace a cognitive process: Gaze behaviour during decision making in a natural environment. J. Eye Mov. Res. 2013, 6, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piquado, T.; Isaacowitz, D.; Wingfield, A. Pupillometry as a measure of cognitive effort in younger and older adults. Psychophysiology 2010, 47, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Wel, P.; van Steenbergen, H. Pupil dilation as an index of effort in cognitive control tasks: A review. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2018, 25, 2005–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carle, C.F.; James, A.C.; Maddess, T. The pupillary response to color and luminance variant multifocal stimuli. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejtz, K.; Duchowski, A.T.; Niedzielska, A.; Biele, C.; Krejtz, I. Eye tracking cognitive load using pupil diameter and microsaccades with fixed gaze. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, A.; Hoffman, D.; Ratwani, R.M. Making sense of mobile eye-tracking data in the realworld: A human-in-the-loop analysis approach. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 19–23 September 2016; Volume 60, pp. 1569–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, P.; Giannopoulos, I.; Raubal, M.; Duchowski, A. Eye tracking for spatial research: Cognition, computation, challenges. Spat. Cogn. Comput. 2017, 17, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jam, F.; Azemati, H.R.; Ghanbaran, A.; Esmaily, J.; Ebrahimpour, R. The role of expertise in visual exploration and aesthetic judgment of residential building façades: An eye-tracking study. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2021, 16, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montañana, A.; Llinares, C.; Navarro, E. Architects and nonarchitects: Differences in perception of property design. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2013, 28, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Hine, D.W.; Muller-Clemm, W.; Shaw, K.T. Why architects and laypersons judge buildings differently: Cognitive properties and physical bases. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2002, 19, 131–148. [Google Scholar]

- Nasar, J.L. Symbolic meanings of house styles. Environ. Behav. 1989, 21, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, W.B.; Craik, K.H.; Price, R.H. (Eds.) Personenvironment Psychology: New Directions and Perspectives; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Chen, X.; Zhao, M.; Xue, C. Cognitive characteristics in wayfinding tasks in commercial and residential districts during daytime and nighttime: A comprehensive neuroergonomic study. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 61, 102534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamachi, M.; Lokman, A.M. Innovations of Kansei Engineering; CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Archdaily. Available online: https://www.archdaily.com/877602/jan-gehl-in-the-last-50-years-architects-have-forgotten-what-a-good-human-scale is#:~:text=What%20should%20we%20understand%20by,human%20scale%20cities (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- The City at Eye Level. Available online: https://thecityateyelevel.com/stories/close-encounters-with-buildings/#:~:text=While%20our%20perception%20of%20public,floor%20fa%C3%A7ades (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Project for Public Spaces. Available online: https://www.pps.org/article/jgehl#:~:text=Necessary%2C%20Optional%2C%20and%20Social%20Activity,Social%20activities%20include%20children%27s (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Recommended Practice | Purpose or Benefit |

|---|---|

| Embed ET exercises (e.g., building walk-throughs or peer design reviews) in coursework | Promotes reflective learning and evidence-based design by revealing where students focus attention |

| Highlight expert vs. novice gaze patterns in critiques | Deepens understanding of user-centered design by students by illustrating perceptual differences |

| Integrate ET projects and assignments into the curriculum | Broadens awareness of how designs are perceived by users by students |

| Plan for equipment constraints (cost, lab space) | Addresses practical implementation barriers and sets realistic project scope |

| Step/Item | Purpose or Rationale | Considerations or Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Define research objectives/questions | Focus the study and align methods with goals | Formulate clear research questions on visual perception or navigation in built environments |

| Select study design and equipment | Choose ET hardware and setting to match objectives | Balance ecological validity vs. experimental control (e.g., VR vs. real-world; screen-based vs. mobile trackers) |

| Establish participant criteria | Ensure a representative, consistent sample | Screen for vision or cognitive issues; obtain informed consent; consider participant fatigue and comfort |

| Calibrate and test equipment | Maximize data accuracy and reduce error | Perform individual calibration for each participant; monitor and correct calibration drift; check for data loss (especially outdoors) |

| Conduct the eye-tracking session | Collect gaze data under real-world conditions | Monitor data quality in real time; minimize head/body movements; control lighting and distractions as much as possible |

| Analyze gaze data | Identify attention patterns quantitatively | Compute fixation counts/durations and scan paths; exclude blinks or noise; use areas-of-interest or heatmaps as appropriate |

| Triangulate and interpret results | Contextualize gaze with other measures | Supplement ET data with surveys or interviews to explain visual behavior; interpret findings in the architectural context |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cruz, M.B.; Rebelo, F.; Cruz Pinto, J. Eye-Tracking Advancements in Architecture: A Review of Recent Studies. Buildings 2025, 15, 3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193496

Cruz MB, Rebelo F, Cruz Pinto J. Eye-Tracking Advancements in Architecture: A Review of Recent Studies. Buildings. 2025; 15(19):3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193496

Chicago/Turabian StyleCruz, Mário Bruno, Francisco Rebelo, and Jorge Cruz Pinto. 2025. "Eye-Tracking Advancements in Architecture: A Review of Recent Studies" Buildings 15, no. 19: 3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193496

APA StyleCruz, M. B., Rebelo, F., & Cruz Pinto, J. (2025). Eye-Tracking Advancements in Architecture: A Review of Recent Studies. Buildings, 15(19), 3496. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15193496