Abstract

At present, industrial heritage preservation in China often focuses on individual industrial buildings, lacking a holistic consideration of industrial settlements (e.g., industrial cities, towns, and villages). This study draws upon the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach to construct a research framework that applies to industrial settlements, considering both integrity and layering. Taking the case of Tongguan Ancient Town—a typical industrial settlement—this study uses the integrated approach of historical materials acquisition, oral interview, and field investigation to review the interactive evolution of industry and space across three historical periods. It identifies a comprehensive set of heritage elements within the Tongguan industrial settlement and proposes a preservation framework for its industrial heritage. The key findings are threefold: industrial settlement heritage possesses characteristics of integrity and layering; the HUL approach can be effectively applied to industrial settlement studies; and the protection of industrial settlements is a crucial step toward establishing a complete system for the inheritance and preservation of China’s urban and rural historical and cultural heritage.

1. Introduction

In 1978, the International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage (TICCIH) was established. In 2003, the TICCIH released the world’s first international document for the conservation of industrial heritage, the Nizhny Tagil Charter for the Industrial Heritage. It comprehensively elaborates the objects, values, and conservation methods of industrial heritage [1]. The Charter garnered global attention regarding industrial heritage, particularly for countries and cities transitioning into the post-industrial era, where the preservation and utilization of industrial heritage were gaining attention [2]. The Nizhny Tagil Charter defined industrial heritage as “buildings and machinery, workshops, mills and factories, mines and sites for processing and refining, warehouses and stores, places where energy is generated, transmitted and used, transport and all its infrastructure, as well as places used for social activities related to industry such as housing, religious worship or education” [1]. This definition mainly focuses on industrial buildings or sites at a micro scale. However, subsequently, the concept of industrial heritage was expanded. The Dublin Principles, published in 2011, adjusted the concept of industrial heritage to include “sites, structures, complexes, areas and landscapes as well as the related machinery, objects or documents” [3]. Industrial heritage encompasses not only tangible heritage (including both movable and immovable heritage) but also intangible heritage. Even for immovable heritage, the scope broadened from industrial buildings or sites to larger-scale industrial areas and industrial landscapes. However, the focus of industrial heritage remains on industrial buildings or sites at a micro scale, even though it still encompasses contiguous industrial areas formed during a concentrated period of industrialization.

China has kept pace with international developments, as evidenced by the State Administration of Cultural Heritage hosting the “Wuxi Forum” in 2006, which resulted in the landmark “Wuxi Recommendations” in the history of industrial heritage conservation in China [4]. Due to the adoption of European methodologies and the architectural academic background of many scholars involved in early industrial heritage conservation, there is a tendency in China to focus on industrial architectural heritage, often limiting efforts to individual buildings rather than developing “historic districts” characterized by industrial heritage, let alone “historic cultural cities” with industrial heritage features [5]. However, China’s industrial heritage, in terms of its evolution and characteristics, differs significantly from that in Europe. In Europe, medieval towns—both in terms of site selection and morphology—were not significantly influenced by industrial factors [6]. The industries that emerged after the Industrial Revolution were mainly concentrated in cities, while rural areas largely retained their natural features and agricultural character until manufacturing gradually shifted from cities to rural areas, starting in the 1960s [7].

In contrast, many Chinese traditional pre-industrial industries were dispersed in surrounding rural areas. During a long period of commodity economy spanning several centuries, a large number of historical towns and villages influenced by industrial factors emerged [8]. After the Westernization Movement in the late Qing Dynasty, industries similarly concentrated in cities, driving the expansion of urban spaces. At the same time, historical towns and villages with industrial characteristics were largely preserved. Therefore, compared to the centralized model in Europe, China’s industrial heritage exhibits characteristics of a longer history, more prominent cultural features, and a clearer sense of locality and ethnicity [9]. It is not only essential to focus on concentrated industrial areas and buildings, but also on the integral industrial settlements and areas formed by these industrial facilities, which is something the existing concept of industrial heritage fails to address fully.

This study attempts to apply the concepts and methods of the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach, using Tongguan Ancient Town in Changsha, Hunan Province—a typical traditional industrial settlement—as a case study. A comprehensive heritage system was constructed across the dimensions of time, space, and industry, aiming to achieve a profound understanding of the characteristics and value of Tongguan’s industrial heritage. Chapter 1 reviews the existing research on industrial heritage to identify the research gaps. Chapter 2 establishes the theoretical framework of this study based on the HUL approach. Chapter 3 focuses on the industrial–spatial evolution of Tongguan Ancient Town, detailing the dynamic evolutionary process of the ceramic industrial chain and the town across three stages, thereby revealing the characteristics and value of Tongguan’s industrial heritage. Chapter 4 details the development of industrial heritage identification methods based on the industrial–spatial context of Tongguan, as well as the construction of a complete preservation framework for Tongguan Ancient Town’s industrial heritage. Chapter 5 extends the methods and framework used for Tongguan to similar industrial settlements and points out the innovations of this study.

2. Literature Review

Since TICCIH introduced the concept of industrial heritage, both Western and Chinese scholars have implicitly expanded its scope, leading to increasingly diverse research on industrial heritage. One aspect is the expansion of the temporal dimension, which focuses not only on heritage objects from the Industrial Revolution in the latter half of the 18th century but also on their earlier pre-industrial and proto-industrial roots [1]. For example, Pouso et al. studied abandoned watermill industrial sites and proposed restoration and conservation plans [10]. In China, numerous studies from the perspective of cultural relics archaeology have examined this type of pre-industrial era industrial heritage, including mining sites [11] and winery sites [12]. Another aspect is the expansion of the spatial scope, especially emphasizing industrial areas and industrial landscapes. For example, Ćopić et al. introduced the methods and effects of transitioning the Ruhr region in Germany from traditional industry to industrial heritage tourism [13]. Dorado and Da Silva proposed methods for analyzing and identifying industrial landscape heritage, including determining the scale of analysis and defining, identifying, and characterizing heritage elements based on spatial, temporal, historical, cultural, and perceptual aspects [14]. Chinese scholars have also conducted research and analysis on large-scale industrial areas, such as the old industrial bases in Northeast China [15] and the urban waterfront industrial areas [16]. A third aspect is the expansion of heritage values, which not only focuses on the conservation of the heritage itself but also emphasizes the significance of the heritage to national history, industrial development, and community life. For example, Cossons comprehensively elaborated on the value of industrial heritage, especially emphasizing the importance of industrial heritage to the community, such as increasing cultural identity, creating employment opportunities, and strengthening urban memory [17]. Liu and Meng systematically reviewed the industrialization process in China over the past 70 years since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, exploring the core values of Chinese industrial heritage [18]. Wan proposed connecting spatial conservation elements through the “industrial chain” to fundamentally understand the logic between material elements of industrial heritage [19].

However, despite the expanded scope of industrial heritage, most studies have focused on concentrated industrial areas formed during a specific period of industrialization. This phenomenon aligns with the logic of industrialization in Europe, but does not hold for Asia and other regions.

In response, the 2011 “Seoul Declaration 2011 on Industrial Heritage in Asia” called for “an effort to expand our understanding of Asian industrial heritage to include traditional industries that remain living and vital to our culture, and not restrict it solely to heritage associated with development paradigms rooted in the Industrial Revolution in the West. Developing the tacit knowledge of practices, crafts skills, and cultural systems necessary for the continuance of many production processes is important for this understanding” [20]. The following year, the “Taipei Declaration for Asian Industrial Heritage”, issued by TICCIH, also noted that “The definition of industrial heritage in Asia should be broadened to include technologies, machinery and producing facilities, built structures and built environment of pre-Industrial Revolution and post-Industrial Revolution periods. Industrial heritage in Asia is always part of a comprehensive cultural landscape, either in urban or rural settings. In addition to the built environment, it strongly reflects the interaction of humans and the land, featuring the characteristics of hetero-topography” [21]. In recent years, some Asian scholars have begun exploring unique protection paths suitable for Asian industrial heritage. Leung and Soyez emphasized Hong Kong’s place, local identities, temporal and spatial specificities and dynamics, and aspects that are nonindustrial but whose social or cultural nature is intimately linked to the creation of the industrial world [22]. Xian suggested actively leveraging bottom-up community efforts to protect Singapore’s industrial heritage [23]. Tipnis and Singh redefined a framework for identifying, protecting, and sustainably developing industrial heritage sites according to India’s industrialization process [24]. Aparna et al. established a regional industrial heritage system comprising tangible and intangible cultural heritage by examining the precolonial history of the Indian city of Kuttichira [25]. Nevertheless, current research on the regional characteristics of Asian industrial heritage remains limited, and there is still a need to strengthen studies in areas such as heritage definitions, heritage systems, and conservation methods.

From the practical perspective of industrial heritage conservation in China, Professor Que Weimin of Peking University early on proposed the concept of “Chinese Traditional Industrial Heritage,” calling for the academic community to consider China’s specific circumstances and to develop a theoretical system of industrial heritage with Chinese characteristics [26]. Subsequently, such empirical studies began to increase. For instance, Que Weimin and Zhou Xiaofang analyzed and discussed the historical origins, current conditions, and cultural values of Shaoxing rice wine industrial heritage, and based on their findings, proposed recommendations for its conservation and utilization [27]. Liu Fuying and colleagues mapped the development and evolution of the silk industry in the Hangjiahu region, defining the scope of modern and contemporary silk industrial heritage through three aspects: time, space, and type. They proposed the “Hangjiahu Modern and Contemporary Silk Industrial Heritage List,” collected data on research cases within this list, and explored the application of databases in heritage protection research [28]. Hou Shi and others took the Daoshi soy sauce fermentation workshop cluster as an example, analyzing its living heritage features, such as the integration of material and intangible heritage, long-term interaction between humans and nature, and continuous evolution. They distilled the core values of such heritage and offered suggestions for holistic protection and active inheritance [29]. Yang Lan and Zhao Xiaoxin analyzed the Jin kiln industrial heritage of Shenhou, clarifying the material and non-material elements within Jin kiln industrial heritage, and proposed a framework for its protection [30]. Chen Xiaobin studied the spatial layout of the red brick industry in Chitian Village, Minnan, focusing on its overall distribution, workshop spatial development, and kiln architecture, summarizing its heritage values and proposing contemporary conservation strategies [31]. Some scholars have also attempted theoretical summaries; for example, Xiong Xiangrui and Wang Yanhui studied the spatial relationships formed by industry in southern Jiangsu villages, proposing a new concept of rural industrial heritage that differs from the current industrial heritage concept, and established a valuation system for it [32]. He Jun and Liu Lihua focused on the particularity of industrial heritage in non-Western countries, selecting relevant industrial heritage from China’s intangible cultural heritage list, and constructing a protection system consisting of two primary factors and thirteen secondary factors [33]. Huang Zhifan and Zou Xu addressed the limitations of current approaches to revitalizing China’s traditional industrial heritage, emphasizing its value features, and proposed new strategies such as “cultural decoding—spatial reconstruction—value regeneration,” “government-led + multi-party participation,” and “cultural empowerment + full involvement of the value chain” for heritage revitalization [9]. However, as Professor Que pointed out, “the content of traditional urban industrial heritage still has not entered the mainstream perspective of China’s industrial heritage research” [34].

Although discussions on this type of traditional industrial heritage have only emerged in recent years, Chinese scholars have long been attentive to these highly characteristic industrial settlements. However, these studies mainly focused on the influence of industry on spatial characteristics. They did not explore the issue of industrial spatial heritage conservation, let alone incorporate it into their industrial heritage research. We can broadly categorize them into two approaches: one examines the patterns of settlement distribution caused by industry from a historical perspective. This type of research originated from the analysis of the urban system in the Chengdu area of Sichuan, China, by American scholar G. William Skinner in the 1940s [35]. For example, Liu examined the towns and villages in Jiangnan where the three major industries—cotton and cotton weaving, sericulture and silk weaving, and rice grain industry—were located, revealing the characteristic patterns of the town distribution caused by industrial differences [36]. Fan summarized that the distance between towns in the Jiangnan area during the Ming and Qing Dynasties was approximately in the range of 12 to 36 li, and each town had a relatively fixed range of rural areas as its economic hinterland [37]. The other approach explores the characteristics of industrial settlements from the perspectives of urban and rural planning and architecture. For example, Zhao studied the traditional settlement forms and traditional residential forms along the ancient Sichuan salt road [38]. Taking the settlements along the Huai salt transport route as an example, Zhao and Zhang summarized the spatial form of salt-producing settlements as “water on all sides” and the characteristics of salt-transporting settlements as having a wharf as the center [39]. Wei et al. studied the location selection, layout, and settlement morphology of three types of industry-related traditional settlements in Zhejiang—agricultural breeding, handicraft manufacturing, and commercial trade—revealing the influence of industry on the spatial characteristics of settlements [40]. Yue and Van studied the interaction and evolution of industry and spatial morphology in silk towns in Jiangnan [41].

In summary, the existing research on industrial heritage reveals that, although the study of industrial heritage is quite extensive, the understanding of industrial settlement is still relatively superficial. The research has not clarified what levels, elements, and values industrial settlement heritage includes, nor how to protect it fully. This is precisely the problem that this research attempts to address.

3. Methods

3.1. The Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) Approach

The “Historic Urban Landscape” (HUL) approach represents a set of conservation principles and methods that were introduced into the field of urban heritage preservation over the past decade. It aims to guide local governments and planning departments to integrate the maintenance and management of historical urban areas into the overall urban planning system and long-term development strategy framework, enhancing the sustainability of urban heritage preservation [42]. It is a tool to reinterpret the values of urban heritage, and its indication of the need to identify new approaches and new tools for urban conservation [43]. In 2011, UNESCO published the Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL Recommendation), marking the official promotion of the HUL conservation concept to the world.

As can be understood from the literal expression of the term Historic Urban Landscape, the core concept lies in two aspects: (1) the first encompasses a broader spatial context from a landscape perspective, i.e., integrity. As defined in the HUL Recommendation, “The historic urban landscape is the urban area understood as the result of a historic layering of cultural and natural values and attributes, extending beyond the notion of a ‘historic center’ or ‘ensemble’ to include the broader urban context and its geographical setting” [44]. The city as a cultural landscape challenges the orthodoxy of modern urban conservation that privileges famous buildings and monuments [45,46]. (2) The second aspect is discerning urban spaces from the perspective of temporal continuity, i.e., layering. The Historic Urban Landscape skillfully uses the term “historic,” which no longer forcibly distinguishes between “ancient” and “contemporary,” but rather unifies them into a broad “historic” concept [47]. Beyond preserving buildings, structures, or landscapes, we need to widen our focus even further to formulate guidelines for future interventions [48]. Instead, we need to understand historic cities through a post-modern lens of feelings and emotions, where experiencing the city is an experience in itself, linking the study of economics with cultural heritage [49].

The HUL approach has now become a popular research method in the field of urban heritage conservation, widely applied in topics such as risk assessment, post-damage recovery, disaster prevention, and adaptive reuse strategy [50,51]. In the field of industrial heritage research, the HUL approach is also widely used. Scholars have summarized three paradigms combining the two through literature review: industrial heritage importance in the HUL context, revitalizing industrial heritage, and strategies for regenerating industrial heritage [52]. It highlights that many authors recognize that the significance of industrial heritage does not lie in its singularity but rather in its implementation and impact on a specific place [53]. Tangible and intangible heritage are intertwined, as abandoned industrial facilities serve as reminders of the past, capturing the everyday lives of people over generations through their psychical records [54]. However, the application of the HUL approach in industrial heritage is often limited to linking the past, present, and future of industrial heritage to promote its adaptive reuse [55], reflecting the layering concept of HUL, without fully leveraging the integrative characteristics of HUL. Therefore, expanding the research scope from industrial heritage to larger industrial settlement levels not only allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the value of industrial heritage but also maximizes the potential of the HUL approach.

3.2. Research Framework

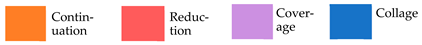

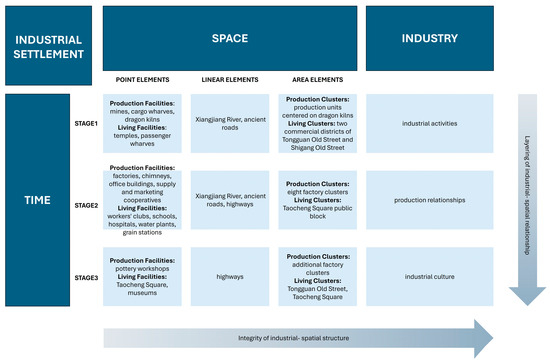

This study draws on HUL principles and methods to construct an analysis framework considering industry, space, and time.

- The systematic association of industry and space: industry includes various industrial activities, such as production, sales, trade, transportation, etc., and it is the “industrial chain” (the so-called “industrial chain” refers to the chain-like association objectively formed between various industrial sectors based on specific technical and economic connections, as well as spatial and temporal relationships) that organizes the inherent logical relationships of these activities [19]. Industrial relationships take space as the carrier. Since the integrity of a single industrial space must be recognized through a macro understanding of the town in which it is located, and the integrity of a town requires a greater regional understanding [56], industrial space not only includes individual buildings but also encompasses entire settlements and even the larger environment.

- The dynamic evolution of industry and space: industry is always in a dynamic state of change due to variations in both supply and demand. The changes in industry inevitably bring about dynamic changes in industrial spaces, including increases or decreases in the spatial scale, the adjustment of the spatial form, and even changes in the spaces. It is this evolution that reflects the industrial history and development logic, which is the unique value of industrial spaces. This study combed through industry–space evolution to form an industrial settlement heritage identification method and constructed a complete industrial heritage preservation framework (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Research framework (source: self-drawn).

Figure 1. Research framework (source: self-drawn).

3.3. Case Study Selection and Empirical Methods

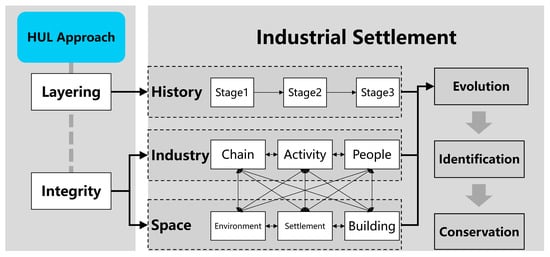

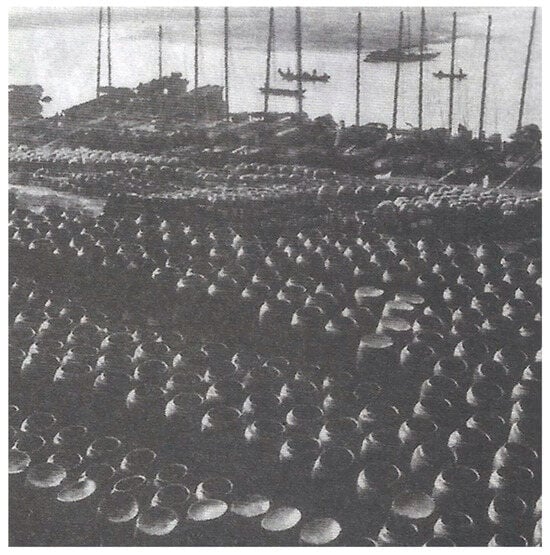

This study selected Tongguan Ancient Town, a typical industrial settlement, as the subject of its case study. Tongguan is in Wangcheng District, Changsha City, Hunan Province, on the west bank of the lower reaches of the Xiangjiang River. The Xiangjiang River borders it to the east, hilly mountains to the west, the Dongting Lake Plain to the north, and the Changsha urban area to the south. There are two main reasons to choose Tongguan. First, for thousands of years, the kiln fires in Tongguan have continued uninterrupted, not only providing sustained vitality to the local economy but also creating a unique and brilliant industrial culture (Figure 2), which facilitates research on its historical evolution. Second, Tongguan still preserves a substantial amount of ceramic heritage, notably including a complete industrial settlement. The Tongguan Kiln Site is a National Key Cultural Relics Protection Unit, and Tongguan Ancient Town is a provincial-level Historical and Cultural Town, which makes it a typical case study on industrial settlements that have developed and prospered due to their industrial origins.

Figure 2.

Changsha kiln porcelain salvaged from the Belitung Shipwreck (the Belitung shipwreck is the wreck of an Arabian dhow that sank around 830 AD. The wreck contained 60,000 items of Changsha ware (produced in kilns in Tongguan). This shows the long history of Tongguan ceramics) (source: https://www.wenweipo.com/epaper/view/newsDetail/1501631498619588608.html) (accessed on 19 June 2025).

The case study employed various data collection techniques, including historical materials acquisition, oral interviews, and field investigations. Historical materials include the Wangcheng Chronicles, historical satellite images from 1975, 2002, and 2024, as well as existing related research, such as 100 Questions on Changsha Kiln and Tongguan Ancient Charm. Oral interviews were conducted with the president of the Tongguan Ceramic Industry Association, Su Jianwei; intangible cultural heritage inheritors Liu Kunting, Liu Zhiguang, and Liu Jiahao; head of the Haixu Ceramics Company Chen Haijun, director of the Urban Construction Office of Tongguan Street Zhou Hu; and local elderly figures who were familiar with the industrial development history in Tongguan. Field investigations involved visits to historical workshops, factories, sites, and production spaces that are still in daily use. Examining the industrial situation and spatial elements in different periods helps to understand the corresponding relationship between industry and space and the interactive changes between the two over time. The industrial–spatial distribution maps for each stage drawn in this paper were all based on investigations using these combined methods.

4. Industrial–Spatial Evolution of Tongguan Ancient Town

Although we can trace back the ceramic history of Tongguan to the Tang Dynasty, the sites from that period were mainly located in the Shizhu Lake area south of present-day Tongguan Ancient Town. Since the Daoguang period of the Qing Dynasty (1821–1850AD), due to increasingly severe problems of low-lying terrain and raw material depletion, the center of the kiln sites began to migrate to the higher terrain and resource-rich Tongguan Town area [57]. We can broadly divide the industrial–spatial evolution of Tongguan Ancient Town since the late Qing Dynasty into three stages: the first stage is from the late Qing Dynasty to the end of the Republic of China in 1949, which is the traditional handicraft period of the ceramic industry; the second stage is from the 1950s to the 1990s, which is the period of large-scale industrial production of Tongguan ceramics; and the third stage is from the 1990s to the present, which is the period of diversified development dominated by intangible cultural heritage protection.

4.1. Stage 1

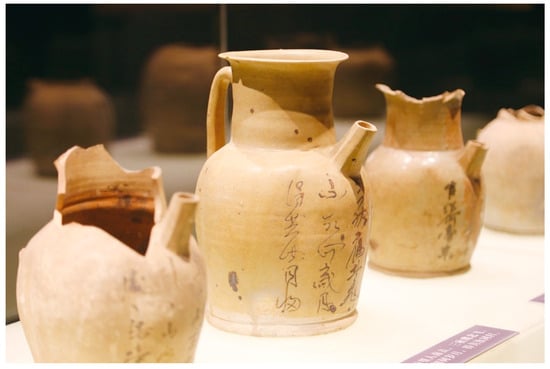

The complete production chain of Tongguan’s ceramic industry should include four major links: raw material preparation, forming, firing, and transportation [57]. For thousands of years, Tongguan’s ceramic industry has been a private individual production and operation model based on household workshops, with each workshop contributing to one link or step in the production chain. The raw material preparation link encompasses several processes, including clay extraction, mud mixing, and clay refining, all of which exhibit firm regional dependence characteristics. “Kiln workers” distinguish various types of mud based on experience, forming a raw material system closely integrated with local natural resources. The forming link includes processes such as shaping, decorating, and glazing, incorporating many design, emotional, and cultural elements. Among them, the “underglaze color” process, which Tongguan Kilns created, is also a point of great interest for the world. The firing link is a key part of ceramic production, which is divided into several processes: kiln loading, firing, and kiln unloading. The ancient Tongguan Kilns used dragon kilns. There were reportedly 72 dragon kilns in Tongguan in ancient times. Experienced full-time “fire masters” were generally responsible for the placement of objects and for controlling the firing temperatures. After unloading from the kiln, the products were transported by various dragon kilns to the nearest wharf for loading onto ships and then transported to various places via the Xiangjiang River. Upstream shipping could pass through the Ling Canal to the Lijiang River, entering the Pearl River system to Guangzhou. In contrast, downstream shipping could pass through Yueyang Chenglingji to Dongting Lake, entering the Yangtze River and sailing east to Yangzhou (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Diagram of ceramic production process (source: [57] pp. 172–176).

Ancient ceramic handicraft production was a very arduous task. Despite this, Tongguan’s kiln workers still found pleasure in hardship, creating a rich and colorful cultural life and folk activities related to the ceramic industry. Daily cultural life included commerce, catering, leisure and entertainment, and religion; there were also four important traditional folk festivals throughout the year, which were the dragon boat race from the tenth to fifteenth day of the first lunar month, the burning of the first kiln on the eighth day of the fourth lunar month, the celebration of Emperor Shun’s birthday on the sixth day of the sixth lunar month, and the burning of pagodas on the fifteenth day of the eighth lunar month [58].

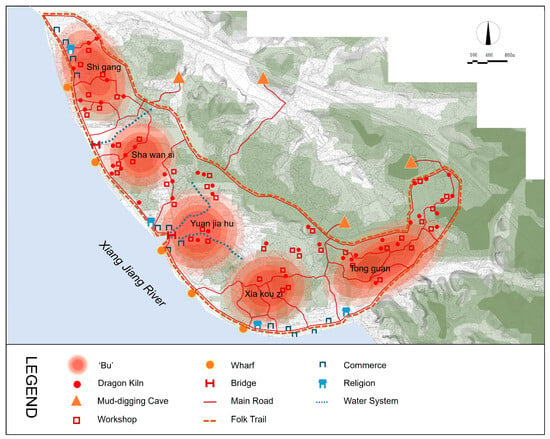

The ancient ceramic industrial space was mainly divided into two parts: production and living. The production part entirely relied on the division of natural terrain to form six areas (called ‘Bu’), with each Bu forming a spatial sequence from the mud-digging cave to the dragon kiln workshop, and then to the wharf, which was perpendicular to the Xiangjiang River coastline, including industrial spatial elements such as mud-digging caves, dragon kilns, workshops, and wharfs (Figure 4). Among them, the combination of a dragon kiln and workshop constituted the most basic ceramic production unit. Due to the high cost of kilns, which required joint investment from multiple families, they developed various workshops around dragon kilns, including clay-refining workshops, blank-making workshops, blank-drying yards, and glazing workshops. In addition, due to the special firing method of dragon kilns, they made full use of the terrain slope during construction, thus forming a spatial form of “the kiln as the backbone, and the workshops following the kiln” (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of industry during stage 1 (source: self-drawn, drawn according to the historical materials, oral interviews, and field investigations).

Figure 5.

Production space characterized by “Kiln as the Backbone, Workshops Following the Kiln” (source: [58] p. 2).

The living space consisted of a public space network with three nodes: Shigang Old Street, Yuanjiahu Commercial Street, and Tongguan Old Street, which runs parallel to the Xiangjiang River coastline and includes industrial spatial elements such as temples and commercial streets. At the same time, Tongguan’s folk activity spaces overlap significantly with this public space network. For example, the burning of the First Kiln activity on the eighth day of the fourth lunar month starts from Dongshan Temple, passes through Shetan Street, Yiziwan, Gaolingshang, Shigang Street, Shawan Temple, Yuanjiahu, Xiakouzi, Tongguan Lower Street, and Middle Street, and returns to Dongshan Temple on Upper Street. Sizhou Temple, Shawan Temple, Xiakouzi, and Dongshan Temple are all important venues for folk activities (Figure 4).

4.2. Stage 2

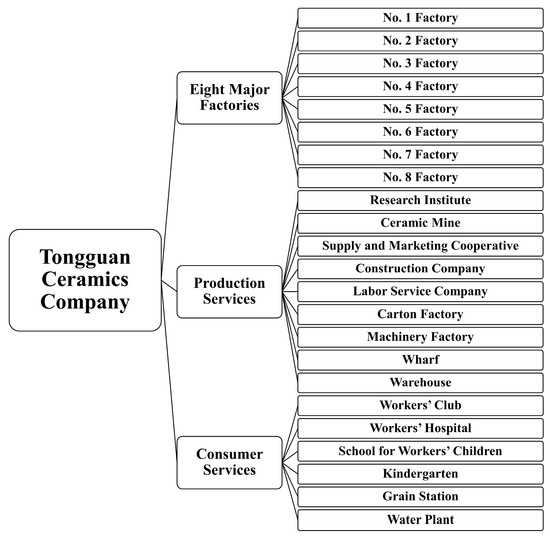

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, production cooperatives were established, which were later unified and merged into collectively owned enterprises. In 1978, the enterprise was renamed Hunan Tongguan Ceramics Company and was under the leadership of the Provincial Light Industry Bureau [59]. During this period, two significant changes occurred in the production chain: first, the production process shifted from being decentralized to integrated. For example, the government established eight major ceramic factories, each with a clear division of labor: No. 1 Factory and No. 2 Factory produced stoneware; No. 3 Factory produced vegetable jars; No. 4 Factory produced water tanks; No. 5 Factory produced tiles; No. 6 Factory produced glazed tiles; No. 7 Factory produced saggars; and No. 8 Factory produced arts and crafts pottery. Each factory had a complete production process from blank forming, decoration, and glazing to firing, packaging, and transportation. In addition to the eight factories, several productive service units were established, such as ceramic mines, which were responsible for the mud supply for all the factories; supply and marketing cooperatives, which were responsible for the unified purchase and sale of materials and products; research institutes, which were responsible for the research and development of new products and technologies; and construction and installation companies, labor service companies, carton factories, and machinery factories, which were responsible for various supporting services. Second, the production process was modernized. For example, more controllable and higher-yielding tunnel kilns, roller kilns, and shuttle kilns gradually replaced the traditional dragon kilns. Furthermore, with the opening of highways and railways, the mode of transportation changed from complete reliance on waterways to a combination of rivers, highways, and railways.

Due to the establishment of large collective enterprises and the improvement of production efficiency, the ceramics company attracted many young laborers to work there. For this reason, Tongguan built a large number of supporting living facilities, including a workers’ club, a workers’ hospital, schools for workers’ children, kindergartens, a grain station, and a water plant. Together with the production facilities mentioned above, these supporting living facilities constituted a complete production, service, and guarantee system, consolidating the foundation for the development of Tongguan’s ceramic industry, making Tongguan Ceramics General Company one of the largest collective enterprises in Hunan. The workers in the ceramic factories not only had a high social status but also had no worries about food and clothing, received generous benefits, and enjoyed a very fulfilling cultural life, fully reflecting the characteristics of the socialist production organization form at that time (Figure 6). It is said that the attractiveness of jobs in Tongguan at the time far exceeded that of the major government departments in Changsha, the provincial capital.

Figure 6.

Organizational structure of Tongguan Ceramics Company (source: self-drawn).

The spatial structure of Tongguan Ancient Town also changed with the transformation of the production organizational structure, transforming the original decentralized spatial structure into a clustered spatial structure with physical boundaries. There were a total of eight productive clusters, distributed throughout the town. Four were located along the river, and four were close to Mei Tong Road to the north. Factories producing large objects were situated along the Xiangjiang River to facilitate water transportation, and factories producing small objects were located along the road to enable land transportation. The interior of each factory cluster formed a spatial unit with complete production capacity through the transformation of the natural terrain, the addition of boundary walls, and the addition of production workshops. No. 4, 6, and 8 Factories even had independent wharves. Apart from these leading factories, there were also a series of facilities that could be shared by various production units, such as administrative office buildings, a research institute, supply and marketing cooperatives, construction companies, labor service companies, carton factories, and machinery factories (Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9).

Figure 7.

Tongguan Wharf in the 1960s (source: [58] p. 19).

Figure 8.

Gate of Tongguan Ceramics Company in the 1980s (source: [58] p. 141).

Figure 9.

Spatial distribution of the ceramics industry during stage 2 (source: self-drawn, drawn according to the historical materials, oral interviews, and field investigations).

There were a total of three living clusters, which were expanded based on the original Shigang Old Street, Yuanjiahu Commercial Street, and Tongguan Old Street, forming the Shigang cluster, the Taocheng Square cluster, and the Tongguan Street cluster. In particular, the scale and facilities of the Taocheng Square cluster have been updated to a greater extent. A series of new public service facilities for living have been built, including a workers’ club, Taocheng Park, a workers’ hospital, schools for workers’ children, kindergartens, a grain station, and a water plant, thus forming a new center of life in Tongguan Town. Among them, the workers’ club has an area of 4381 square meters, and the main building is a cinema, which was the largest in the Changsha area at that time (Figure 9).

4.3. Stage 3

Since 1994, under the impact of the market economy, enterprise production declined, and in 2011, the enterprise was devolved to the Tongguan Subdistrict [59]. The original workforce of more than 20,000 ceramic workers was diverted due to reforms in the system and mechanisms, mainly flowing in three directions: (1) Some workers chose to work in ceramic industry cities such as Foshan, Liling, and Jingdezhen, with older workers retiring directly. (2) Workers were employed by the original collective factories that had been privately or jointly contracted, implementing lease management, with the factories’ responsibility for their profits and losses. For example, No. 1 Factory was divided into three parts, namely the Haixu Ceramics Company, Tonghong Ceramics Company, and Youchuang Ceramics Company, and No. 2 Factory was privately contracted to establish the Xingguang Stoneware Factory. (3) Some craftsmen with good skills started their businesses by establishing personal pottery workshops, such as Ni Ren Liu Studio, Liu Zhiguang Studio, and Yong Qiling Studio, with the production model shifting from mass production to a handcrafted, branded, and high-quality model. The production model of pottery workshops is different from both the traditional handicraft model and the modern large-scale industrial model. While retaining traditional handcraft skills, modern production technology elements are gradually introduced, such as using computer-aided design to enhance the artistry and cultural content of products, using automated and mechanized equipment to improve product qualification rates and accuracy, and promoting sales through online platforms.

Although the ceramic industry declined significantly during this period, the emphasis on ceramic culture soared to unprecedented heights. The Changsha Tongguan Kiln Site was announced as part of the third batch of National Key Cultural Relics Protection Units by the State Council in 1988. In 2011, the Changsha Tongguan Kiln Ceramic Firing Technique was included in the third batch of the National Intangible Cultural Heritage List. In December 2013, the Tongguan Kiln Site Park was awarded the title of National Archaeological Site Park, and in January 2021, it was categorized as a National 4A-level tourist attraction. To protect Tongguan’s ceramic culture, the Wangcheng District Tongguan Ceramics Industry Association was established in 2012 to be responsible for the protection, management, utilization, and inheritance of the Changsha Tongguan Kiln Ceramic Firing Technique. Tongguan currently has a total of seven representative inheritors at the national, provincial, and municipal levels. Intangible cultural heritage inheritors and their pottery workshops play a significant role in the development of Tongguan’s ceramic industry at this stage. To protect traditional industrial culture and enhance the tourism experience, several folk activities within the ceramic industry have been revived, including the Pottery Kiln God Worship activity and the Dry Season Art Festival.

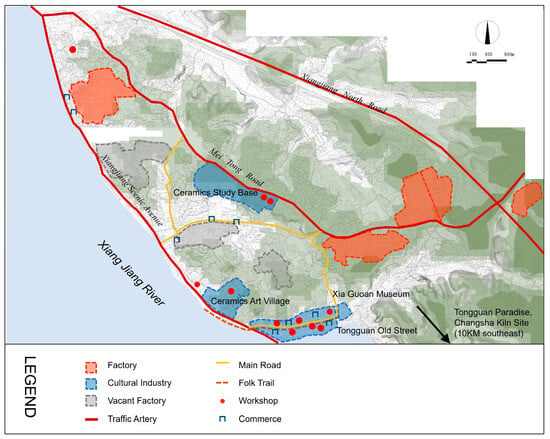

As mentioned earlier, the ceramic industrial space in this period mainly has two models: factories and studios. Factories primarily receive orders from other locations, selling at fixed sites, and mainly utilize the original ceramic factory buildings for production; these buildings are primarily concentrated along the highway to facilitate transportation. Due to the limited production scale, studios also concentrate all production processes in one place, and even the kiln-firing link can be solved by small electric kilns and gas kilns. Their layout is relatively dispersed, often connected to the ceramic artists’ homes (Figure 10). Therefore, the production space in this period no longer forms a well-defined and mutually cooperative spatial system within the town as it did in the previous period; all the production units are independent, and the town’s spatial structure has separated from the ceramic industry to a certain extent. To cooperate with tourism development, around 2010, the Tongguan town government transformed Tongguan Old Street into a ceramic-themed street, intentionally attracting many ceramic artists and ceramic shops to gather here, thus forming a relatively concentrated ceramic production and sales cluster (Figure 11 and Figure 12).

Figure 10.

Production scene in a pottery studio (source: https://m.voc.com.cn/xhn/news/202407/20318982.html) (accessed on 14 July 2025).

Figure 11.

Ceramic-themed Street in Tongguan Old Street (source: self-photographed).

Figure 12.

Spatial distribution of industry during stage 3 (source: self-drawn, drawn according to the historical materials, oral interviews, and field investigations).

With the collapse of the “enterprise-run society” system, the original series of public service facilities operated by the Ceramics General Company were either transferred to the subdistrict and communities, such as the schools, hospitals, and water plant, or directly closed, such as workers’ clubs. On the other hand, the government hopes to use the original industrial resources to develop cultural industries related to ceramics. Therefore, in the past 10 years or so, tourism and cultural facilities have been formed through government investment and the introduction of private capital, such as the construction of the Tongguan Kiln Site Park, museums, and Guofeng Paradise near the Tongguan Kiln Site, the concentration of multiple museums and tourist attractions in Tongguan Old Street, the formation of a pottery research base using the space of No. 3 Factory, and the formation of an international pottery village utilizing the space of No. 8 Factory. The construction of these cultural facilities has effectively enhanced the popularity of Tongguan’s ceramic industry and formed a cultural brand with an influence in Changsha (Figure 12). Although tourism and cultural creativity have brought vitality to the neighborhood, their impact on the protection of the neighborhood’s cultural heritage, their effects on traditional ceramic culture, and their impact on conventional social structure still need to be carefully evaluated.

5. Industrial Heritage Preservation Framework for Tongguan Ancient Town

5.1. Identification of Industrial Heritage Elements

As can be seen from the current list of cultural relic sites in Tongguan, there are only 11 listed heritage sites related to the ceramic industry (the 11 listed heritage sites are: Changsha Tongguan Kiln Site, Waixing Kiln, Yixing Kiln, Dongshan Temple Stage, Renxing Kiln, Gongxing Kiln, Shigang Kiln Site, Wayaotang Kiln Site, Wanpotang Kiln Site, and Yaotouchong Kiln Site). From this list, it is not difficult to see that the heritage types are mainly individual ancient kiln sites, and the heritage period is all ancient. It cannot fully capture the ancient industrial spatial structure and culture of Tongguan Ancient Town, nor can it accurately reflect the history of Tongguan’s ceramic industry across different periods, particularly its post-1949 brilliance. Based on the HUL approach, the Industrial Settlement Heritage System was constructed. First, the industrial space of each period is established as the foundation of its industrial chain. This approach focuses not only on individual industrial elements but also on the differences and connections between them, emphasizing the combination of “points,” “lines,” and “areas.” Second, the industrial spaces of different periods are overlaid to form an industrial spatial system that reflects temporal changes. Finally, this spatial system is integrated with industrial activities, industrial organization, and industrial culture to bridge the gap between the physical space and intangible culture, thereby forming a complete industrial settlement heritage system.

The Industrial Settlement Heritage System is composed of three spatial levels—points, lines, and surfaces—two forms—tangible and intangible—and multiple periods. Using Tongguan as an example, the point elements can be divided into two major categories: production facilities and living facilities. The production facilities include eight minor categories: mines, cargo wharves, dragon kilns, factories, chimneys, office buildings, supply and marketing cooperatives, and pottery workshops. The living facilities include nine minor categories: temples, passenger wharves, workers’ clubs, schools, hospitals, water plants, grain stations, Taocheng Square, and museums. Point elements are the venues where various industrial activities are conducted, directly reflecting the productivity levels and industrial development status of different periods. The linear elements mainly consist of Tongguan’s transportation connections, including the Xiangjiang River, ancient roads, and highways. Linear elements not only provide essential communication within the production processes of Tongguan Ancient Town but also connect this ceramic production base with the outside world, embodying the production organization methods of different periods. The shift in transportation modes from waterways to land routes, and from ancient paths to modern highways, also reflects the historical transformation of production relationships methods. The area elements primarily consist of concentrated industrial areas or clusters formed in Tongguan during different historical periods, encompassing two major categories: production clusters and living clusters. The production clusters comprise production units centered on dragon kilns, established during stage 1, the eight factory clusters formed during stage 2, and the additional factory clusters established during stage 3. The living clusters include the two commercial districts of Tongguan Old Street and Shigang Old Street, which were formed during stage 1, as well as the Taocheng Square public block, formed during stage 2. Area elements represent the integrated communities associated with industry, encompassing not only various industrial activities and production relationships but also the living industrial population, fully reflecting the industrial culture of different periods (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Industrial Settlement Heritage System of Tongguan (source: self-drawn).

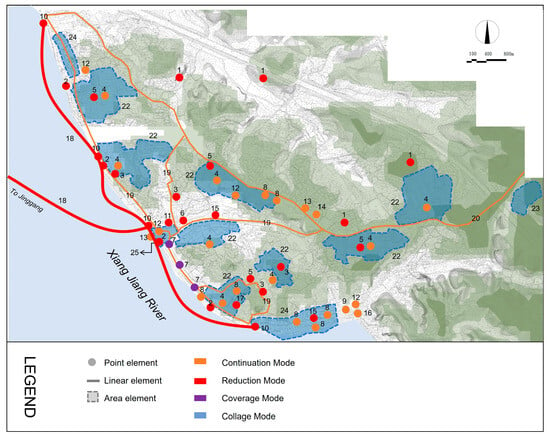

5.2. Conservation Method of Industrial Settlement

Unlike traditional heritage conservation approaches, the core principle of the HUL (Historic Urban Landscape) methodology lies in acknowledging the contemporary changes in heritage and emphasizing its adaptive reuse. Therefore, HUL Recommendation provides a toolkit comprising a six-step framework (mapping, consensus, vulnerability, integration, prioritization, partnerships) and four categories of tools (knowledge and planning tools, community engagement tools, regulatory systems, financial tools) [44]. At the practical implementation level, it is essential to select appropriate tools based on different heritage objects and application contexts, thereby accurately diagnosing the core issues, avoiding potential risks, and promoting effective heritage conservation. In this process, the key step is to distinguish between different types of heritage objects and formulate tailored conservation measures. Scholars have already explored this aspect. For example, He used the concept of a “four-dimensional city” to summarize it. He concluded that there are three forms of spatial morphology: a superimposed form, collage form, and extended form [60]. The superimposed form refers to replacing elements while retaining the historical structure; the collage form refers to the coexistence of old and new elements through decomposing the historical structure and intervening with new elements; and the extended form refers to the growth of new elements based on the original pattern, so that the new and old elements are isomorphic [60]. Similarly, Liu proposed that the layered space of a specific limited block can be summarized into four basic patterns: a maintenance mode, coverage mode, juxtaposition mode, and decline mode [61]. These two interpretations help us to understand the complex composition of urban heritage. Building on this, combined with the actual situation of Tongguan, the industrial spatial systems of different periods are overlaid to analyze changes and succession within the industrial space. Four retention modes—continuation, reduction, coverage, and collage—are distinguished and serve as the foundation for formulating conservation policies. Continuation means that most of the material space has no significant changes and is in daily use; reduction means that the speed of abandonment far exceeds that of new construction, and the use function has basically been lost; coverage implies that most of the material space has become a new scale and style, and the function has also been replaced; and collage means that the old and new material spaces coexist, as do the latest and old usage states.

Among the point elements, (some) factories, pottery workshops, temples, schools, hospitals, museums, and cultural and creative parks are still in daily use, that is, the continuation mode. Therefore, not only must the physical spatial entity be protected, but so must the industrial function that is still in use. For example, through productive protection, the Tongguan ceramic production technology, ceramic culture, and other related aspects are included in the protection of ceramic factories and pottery workshops. The government should implement policies such as tax reductions and financial subsidies to support these buildings in maintaining their original functions. The function of the supply and marketing cooperative has disappeared, and the original building is being used as a department store, which belongs to the coverage mode. The degree of conformity between the new function and the old place is good, demonstrating an example of the concept that “new wine does not break the old bottle” [62]. Therefore, the existing function is retained, and only maintaining the original building will be appropriate. When faced with a transformation of function, it is essential to promptly assess the compatibility between the new function and the existing structure. Methods such as government leasing and community leasing should be employed to ensure that the new functions align as closely as possible with the form of the old buildings. Mines, cargo wharves, dragon kilns, (some) factories, chimneys, office buildings, ferry wharves, the workers’ club, and the grain station have lost their functions and are in a state of abandonment, which belongs to the reduction mode. For this type of heritage, the damaged parts should be reinforced and rescued, and new cultural display functions can be placed to restore their vitality. For example, the worker’s club with epoch-making significance can be transformed into the Tongguan Ceramic Culture Performing Arts Center, and the grain station can be protected and repaired to serve as an art exhibition venue or for other purposes (Figure 14, Table 1).

Figure 14.

Distribution map of industrial heritage elements in Tongguan Ancient Town (source: self-drawn).

Table 1.

Industrial heritage preservation framework for Tongguan Ancient Town (source: self-drawn).

Among the linear elements, ancient roads and highways are still in daily use, thus belonging to the continuation mode. For this type of heritage, in addition to daily maintenance, it should also be used to strengthen Tongguan’s cultural tourism. For example, these roads can serve as a foundation for enhancing the tourism experience and linking the various point-like elements. Research indicates that sustainable tourism plays a crucial role in fostering cultural appreciation, generating revenue, promoting cross-cultural understanding, developing community commitment, empowering locals, and driving economic growth while preserving cultural heritage [63]. The Tongguan ceramic industry no longer relies on the Xiangjiang River for water transportation; thus, the Xiangjiang River belongs to the reduction mode. Therefore, in Tongguan’s future cultural tourism development, it is inevitable that the protection and utilization of the Xiangjiang River resources will need to be strengthened. On the one hand, the water tourism experience route can be extended, such as enhancing connections with Jinggang Ancient Town on the opposite bank and increasing water transportation links between several of Tongguan’s wharves. On the other hand, efforts should be made to optimize the riverside space by adding scenic walkways, rest platforms, and other facilities to provide a high-quality waterside environment for the public. These waterfront spaces could even be used to host a series of cultural activities, allowing the unique characteristics of the riverside town to be rediscovered and showcased (Figure 14, Table 1). For example, Bilbao’s transformation, driven by the Guggenheim Museum, created the “Guggenheim Effect,” [64] and Shanghai has fully utilized its riverside space to hold the Urban Space Art Season SUSAS, which has contributed significantly to industrial upgrading and spatial renewal of the city [65].

Among the area elements, industrial areas or clusters have undergone decades or hundreds of years of changes, and the spatial form and functions have been continuously iterated and updated, retaining the spatial imprints of different periods, thus belonging to the collage mode. This type of heritage should be considered as “living heritage”, balancing the protection of industrial heritage and the daily use functions. In addition to maintaining the continuity of use, it is also essential to ensure the continuity of community connections, continuity of cultural expressions, and continuity of care to ensure ongoing safeguarding and management [66]. The core community does not simply participate in the process but is actively empowered: it can set the agenda, make decisions, and retain control over the entire process [67]. For Tongguan’s industrial clusters, those still actively involved in production should continue to maintain their industrial functions, with efforts to improve the factory environment to enhance workers’ working conditions. Conversely, industrial areas no longer in use should establish stronger connections with surrounding communities by delineating scenic protection zones, integrating new cultural and leisure functions, and involving residents. This approach allows workers and nearby residents to share the benefits of industrial heritage, such as improved living conveniences and cultural prosperity, similar to the practices of the “Maisons Folie” in Lille, France [68]. Regarding Tongguan’s residential clusters, we should make efforts to preserve the spatial and environmental characteristics of the neighborhoods while introducing tourism and leisure industries to generate more employment opportunities. This not only helps to retain original residents but also provides funding for heritage conservation, creating a positive cycle of sustainable development and balance (Figure 14, Table 1). Additionally, advanced technologies can be employed to forecast and simulate tourism demand [69], enabling the provision of high-quality tourism products with greater precision.

6. Conclusions

Using Tongguan Ancient Town as a case study, this research explored the unique values and key preservation points of this type of industrial heritage with Chinese characteristics. The main conclusions are as follows.

- Industrial settlement heritage possesses characteristics of integrity and layering, which distinguish it from the concept of industrial heritage. It is composed of three spatial levels—points, lines, and surfaces—two forms—tangible and intangible—and multiple periods. Industrial settlement heritage is not merely a simple collection of elements but an organic combination of points, lines, and surfaces. It reflects both the overall coupling relationships formed by industrial chain elements and the stratified relationships resulting from temporal evolution. This markedly differs from the relatively concentrated and independent nature typical of traditional industrial heritage. This study broke through the conventional paradigm of industrial heritage research, expanding the spatial scope of industrial heritage from individual buildings to settlements, and expanding the time scope from a relatively concentrated period of industrialization to the entire historical period. This can facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of the generation logic, change rules, and the characteristics and values of industrial heritage, providing a valuable supplement to the Western concept of industrial heritage.

- The HUL approach can be effectively applied to the industrial–spatial evolution, heritage element identification, and the protection of industrial settlements. Due to the integrity and layering of industrial settlement heritage, the identification of heritage elements and the protection of these settlements cannot remain confined to individual buildings or static aspects. The HUL method offers excellent research tools: on the one hand, it takes into account the relationship between industry and space and considers it as part of the long-term evolution process of the industrial settlement; on the other hand, it stresses the continuity of heritage and community use to promote sustainable preservation of such living heritage. This framework provides methodological insights for the study of similar industrial heritage and industrial settlements in China and other Asian countries. It also offers a unique research perspective for broader issues such as traditional village protection and rural revitalization. Of course, since this discussion is limited to a framework level, issues such as stakeholder coordination challenges, contested heritage narratives, or tensions in adaptive reuse practices require further in-depth research.

- The protection of industrial settlements is a crucial step toward establishing a complete system for the inheritance and preservation of China’s urban and rural historical and cultural heritage. Although China’s cultural heritage conservation has achieved significant progress over more than four decades of development [70], it has long suffered from a tendency towards “fragmentation,” that is, a continued emphasis on protecting individual elements, especially the “important” heritage sites. Meanwhile, insufficient attention is given to the overall environment of towns and settlements, leading to the detachment of physical entities from their broader context and cultural foundations, thereby diminishing their inherent vitality [71]. In response to this, central government documents in recent years have strongly emphasized holistic and systematic preservation concepts. In September 2021, the General Office of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the General Office of the State Council issued the Opinions on Strengthening the Protection and Inheritance of Historical and Cultural Heritage in Urban and Rural Development, proposing to focus closely on building a multi-level, multi-element, systematic, and complete system for the protection and inheritance of urban and rural historical and cultural heritage (General Office of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and General Office of the State Council. (3 September 2021). Opinions on Strengthening the Protection and Inheritance of Historical and Cultural Heritage in Urban and Rural Development. [EB/OL]. https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-09/03/content_5635308.htm, accessed on 20 June 2025). The overall protection framework proposed for industrial settlements is an effective response to establishing such a comprehensive system for urban and rural historical and cultural preservation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C.; methodology, Y.C.; software, J.Z.; validation, J.Z. and Y.C.; formal analysis, J.Z.; investigation, J.Z.; resources, J.Z.; data curation, J.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.C. and Y.G.; visualization, J.Z. and Y.C.; supervision, Y.C.; project administration, Y.C. and Y.G.; funding acquisition, Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the MUST Faculty Research Grants (FRG-25-039-FA).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the Data Availability Statement. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- TICCIH. The Nizhny Tagil Charter for the Industrial Heritage. (2003-07) [EB/OL]. Available online: https://ticcih.org/about/charter/ (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Loures, L. Industrial heritage: The past in the future of the city. Wseas Trans. Environ. Dev. 2008, 4, 687–696. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS; TICCIH. Dublin Principles. (2011-11) [EB/OL]. Available online: https://ticcih.org/about/about-ticcih/dublin-principles/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Shan, J. On Protection of Industrial Heritage, a New Form of Cultural Heritage. China Cult. Herit. 2006, 4, 10–47. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.Y. Roundup of the Development of Industrial Building Heritage Conservation. Archit. J. 2012, 1, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A.E.J. Translation of History of Urban Form: Before the Industrial Revolution; Cheng, Y., Translator; The Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Keeble, D.; Owens, P.L.; Thompson, C. The urban-rural manufacturing shift in the European Community. Urban Stud. 1983, 20, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S. A Study on Towns in Jiangnan during the Ming and Qing Dynasties; Fudan University Press: Shanghai, China, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Zou, X. Research on the Path to Revitalization of China’s Traditional Industrial Heritage. Jiangxi Soc. Sci. 2025, 5, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouso-Iglesias, P.X.; Arcones-Pascual, G.; Bellido-Blanco, S.; Villanueva Valentín-Gamazo, D. Abandoned rural pre-industrial heritage: Study of the Riamonte mil complex (Galicia, Spain). Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 2023, 14, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Yu, L.; Zeng, Q.; Yang, X.; Huang, L. Survey and Value Research of Gejiu Dachong Mining Sites from the Perspective of Cultural Landscape. Study Nat. Cult. Herit. 2024, 4, 50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Ding, X. The Perspective of Integrated Protection of Industrial Heritage: A Case Study of Shuanggou Historical Town Protection Planning. Int. Plan. Hist. Soc. Proc. 2024, 20, 377–378. [Google Scholar]

- Ćopić, S.; Đorđević, J.; Lukić, T.; Stojanović, V.; Đukičin, S.; Besermenji, S.; Stamenković, I.; Tumarić, A. Transformation of industrial heritage: An example of tourism industry development in the Ruhr area (Germany). Geogr. Pannonica 2014, 18, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorado, M.I.A.; da Silva, M.M. The Heritage Dimension of Industrial Landscape. Methodological Keys for Its Analysis and Identification. Rigas Teh. Univ. Zinat. Raksti 2024, 20, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Han, F.; Xu, D. The Hierarchical Structure and Integrity Protection of Industrial Landscape Heritages: A Case Study of the Old Industrial Area in Northeast China. Econ. Geogr. 2012, 2, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Weng, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z. Spatial analysis and landscape reconstruction of urban waterfront industrial heritage architectural complex: A case study on Hangzhou section’s of the Grand Canal. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Sci. Ed.) 2015, 3, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossons, N. Why preserve the industrial heritage? In Industrial Heritage Re-Tooled; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 6–16. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.Y.; Meng, F.L. A Preliminary Exploration on the Core Value of Industrial Heritage of the People’s Republic of China. New Archit. 2022, 4, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Q. Exploring the Value on the Industrial Chain of Wuhan Industrial Heritage. New Archit. 2012, 2, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- modern Asian Architecture Network (mAAN). mAAN Seoul Declaration 2011 on Industrial Heritage in Asia. (2011-08) [EB/OL]. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/1580547/mAAN_Seoul_Declaration_2011_on_Industrial_Heritage_in_Asia/ (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- TICCIH. Taipei Declaration for Asian Industrial Heritage. (2012-11) [EB/OL]. Available online: https://ticcih.org/about/charter/taipei-declaration-for-asian-industrial-heritage/ (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Leung, M.W.; Soyez, D. Industrial heritage: Valorizing the spatial–temporal dynamics of another Hong Kong story. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2009, 15, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, L.Y. Utilitarian Heritage: The Panopticon of Narratives behind Industrial Heritage Conservation in Singapore. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tipnis, A.; Singh, M. Defining Industrial Heritage in the Indian Context. J. Herit. Manag. 2021, 6, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparna, M.P.; Mohammed, B.; Shwetha, P.E.; Hajela, P. Potentials of Revitalizing the Industrial Heritage of Kuttichira to Infuse a Sense of History in Calicut, India. Int. Soc. Study Vernac. Settlements 2024, 11, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Que, W. Chinese Traditional Industrial Heritage in the Scope of World Heritage. Econ. Geogr. 2008, 6, 1040–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Que, W.; Zhou, X. The Shaoxing Yellow Wine Heritage Protection from the Perspective of Industrial Heritage. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2013, 7, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Song, Z.; Qiang, W.; Hu, S. Research on Construction and Application of Comprehensive Information Database of Modern Silk Industrial Heritage in Hangzhou-Jiaxing-Huzhou Area. Ind. Constr. 2023, 6, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Shen, P.; He, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, K.; Ma, C. The Overall Protection and Dynamic Inheritance of Traditional Handicraft Living Heritage—The Example of the “Xianshi Soy Sauce Brewing Workshop Group”. Study Nat. Cult. Herit. 2024, 5, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhao, X. Research on the Composition and Conservation of Jun Porcelain Industrial Heritage in Shenhou Town of Yuzhou City in Henan Province. Urban. Archit. 2023, 3, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Study of Spacial Heritage of the Red Brick Industry in Chidian Village, Minnan. Master’s Thesis, Hua Qiao University, Quanzhou, China, 2021. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD202301&filename=1022421341.nh (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Xiong, X.; Wang, Y. The Concept, Type Characteristics and Values of Rural Industrial Heritage: Based on the Investigation in the Southern Area of Jiangsu. Ind. Constr. 2023, 10, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Liu, L. The Construction of Industrial Heritage’ Conservation System—From the Traditional Industrial Heritage on Chinese’ Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists. Urban Stud. 2010, 8, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Que, W. Urban Industrial Heritage from Chinese Traditional Perspective—Introduction to the Topic Papers on “Traditional Urban Industrial Heritage” in Chinese Landscape Architecture. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2013, 7, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, G.W. Marketing and Social Structure in Rural China; Shi, J.; Xu, X., Translators; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. Specialised Markets in Jiangnan during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Shih-Huo Mon. 1978, 8, 365–380. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, S. Municipal Networks in the Yangtze River Delta during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Fudan J. 1987, 2, 93–100+103. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, K. A Study on the Traditional Settlements and Buildings of Sichuan Ancient Salt Road. Doctoral Dissertations, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, 2007. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CDFD0911&filename=2009034021.nh (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Zhao, K.; Zhang, X. Study on Huai Salt transportation line and town settlement along the line. J. Cent. China Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2019, 3, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Wang, J.; Chang, C. Analysis on Industry Type and Settlement Form of Zhejiang Traditional Industry Settlement. Urban. Archit. 2023, 3, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.; Van DIJK, T. How industry and urban form co-evolve: The case of the silk industry town of Shengze, China. METU J. Fac. Archit. 2023, 40, 99–122. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Jing, F.; Shao, Y. Global practices of the UNESCO historic urban landscape: Ten-year review and insights for Chinese urban heritage protection. City Plan. Rev. 2022, 46, 90–98. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, K. Historic Urban Landscape Paradigm-A Tool for Balancing Values and Changes in the Urban Conservation Process. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2023, 11, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Recommendation on Historic Urban Landscape (2011-11). Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/hul/ (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Taylor, K. The Historic Urban Landscape paradigm and cities as cultural landscapes. Challenging orthodoxy in urban conservation. Landsc. Res. 2016, 41, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. Civic Engagement Tools for Urban Conservation. In Reconnecting the City: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach and the Future of Urban Heritage; Bandarin, F., van Oers, R., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bandarin, F.; van Oers, R. The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century; Pei, J., Translator; Tongji University Press: Shanghai, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hein, C. Creative Practices: Bridging Temporal, Spatial, and Disciplinary Gaps. Eur. J. Creat. Pract. Cities Landsc. 2018, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Greffe, X. Urban Cultural Landscapes; Griffith University: Nathan, QLD, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, W. Research hotspots and trends in the Historic Urban Landscape: A bibliometric perspective. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A.P. Historic urban landscape approach and living heritage. Conserv. Living Urban Herit. Theor. Consid. Contin. Change 2017, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Farashah, M.D.P. A conceptual planning framework to integration of industrial heritage regeneration with historic urban landscape approach. Geogr. Pol. 2024, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M.J.; Jiménez-Morales, E.; Rodríguez-Ramos, R.; Martínez-Ramírez, P. Reuse of port industrial heritage in tourist cities: Shipyards as case studies. Front. Archit. Res. 2024, 13, 164–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinović, A.; Ifko, S. Industrial heritage as a catalyst for urban regeneration in post-conflict cities Case study: Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Cities 2018, 74, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintossi, N.; Ikiz Kaya, D.; Pereira Roders, A. Assessing cultural heritage adaptive reuse practices: Multi-scale challenges and solutions in Rijeka. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H. An Analysis of the Integrity of the Modern Industrial Heritage: Discussions on Nizhny Tagil Charter and The Dublin Principles. New Archit. 2019, 1, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.P. 100 Questions on Changsha Kiln; Guangdong Economic Publishing House: Guangzhou, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.Z. Tongguan Ancient Charm; Hunan People’s Publishing House: Changsha, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wangcheng Chronicles Compilation Committee. Wangcheng Chronicles; SDX Joint Publishing: Beijing, China, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y. Probe into the Theory and Practice of Four-Dimensional City. Doctoral Dissertation, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.F. The Anchoring-Layering Theory: For a Better Understanding and Conservation of Historic Urban Landscape. Doctoral Dissertation, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, D. Introduction to Architectural Heritage Conservation, Restoration, and Rehabilitative Regeneration; Wuhan University Press: Wuhan, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pai, C.H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.L.; Li, K.; Shang, Y. Current challenges and opportunities in cultural heritage preservation through sustainable tourism practices. Curr. Issues Tour. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, B.; Haarich, S. Museums for urban regeneration? Exploring conditions for their effectiveness. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2009, 2, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartog, H.D. Shanghai’s regenerated industrial waterfronts: Urban lab for sustainability transitions? Urban Plan. 2021, 6, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesuriya, G. Living heritage. In Sharing Conservation Decisions: Current Issues and Future Strategies; ICCROM: Rome, Italy, 2018; pp. 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Poulios, I. Discussing strategy in heritage conservation: Living heritage approach as an example of strategic innovation. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 4, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamour, C.; Durand, F.; Tursi, C.; Popa, N.; Bosredon, P.; Perrin, T.; Leloup, F. European Capitals of Culture and Cross-Border Urban Cohesion: Best Practices Guide and Toolkit for Evaluation; European Capitals of Culture and Cross-border Urban Cohesion: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sucahyanto Hardi, O.S.; Hijrawadi, S.N.; Liu, C.N.; Nabilla, L. Identification of Ciwadon Cave as geotourism site using Modified-Geosite Assessment Model (M-GAM) in Jonggol, West Java, Indonesia. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2024, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L. Evolution of the Protection Planning System of Chinese Historic and Cultural Cities and its Introspection. China Anc. City 2016, 8, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Hu, L.J.; Zhao, J. Integrated Conservation and Utilization of Historic and Cultural Resources from the Regional Perspective- The Case of Southern Anhui. Urban Plan. Forum 2016, 3, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).