Financial Modelling of Transition to Escrow Schemes in Urban Residential Construction: A Case Study of Tashkent City

Abstract

1. Introduction

Transition to Escrow Arrangements in Uzbekistan

2. Literature Review

2.1. International Analysis of Ex-Post Escrow Transition Effects and Survey Opinion

2.2. International Analysis of Ex-Ante Escrow Transitional Aspects: The Role of Financial Modelling

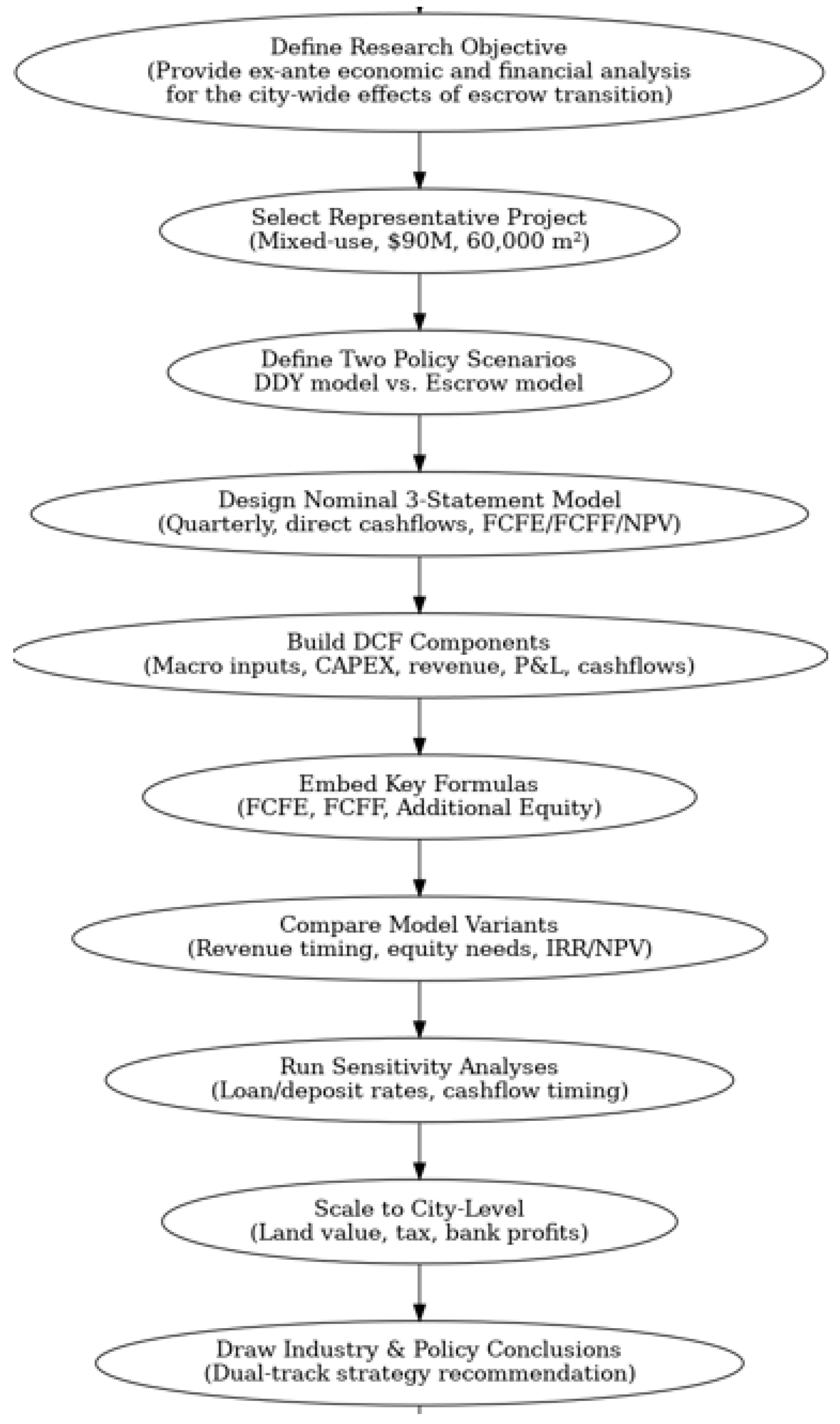

3. Methodology

3.1. Key Data Assumptions and General Features of the Financial Model

- “DCF” tab is the central tab of the model which spreads out key development project costs across time and construction sequences, as well as aggregates key model cash flows (FCFFs (Line 135) and FCFEs (Line 129)) and outputs (the balance sheet in Lines 110–122, the P&L statement in Lines 76–90, and the direct-format cashflow statement (in Lines 93–108) for the project)

- “VAT estimates”—the model dedicates a separate tab to VAT accounting-related cashflows and offsets due to the uniformity of construction practices in Tashkent on that point, as the projects can only be formally registered by developers/construction companies that are themselves registered as VAT taxpayers. As a rough rule of thumb, we adopt a uniform assumption that 50% of construction costs, except for land and administrative costs, are subject to the VAT tax inputs.

- “Unit costs” is the tab to record unit construction cost specifications for each stand-alone construction block or property in the project. These can be sourced from the actual construction estimates or construction estimators, such as Co-Invest Residential [27], which was relied upon (unit comparable plan IDs used are indicated on line 9 of the “unit costs” tab). Making allowances for structural and market vacancies, Table 2 on this Tab (Lines 26–37) also records projected selling prices for the developed units in the blocks (the average of USD 1700 per m2 of general living space is the assumed best estimate for representative construction quality class selected (gross of any discounts, net of VAT) [11]. An overview of statistically significant property pricing attributes for Tashkent city is also given in [28], including commercial and parking spaces, along with the associated sales VAT.

- “Land valuation” tab focuses on providing the valuation of the land element based on the assumption of a certain land share in the (positive) FCFF cashflows generated by the project [29]. This valuation, therefore, can be regarded as the demand-side valuation (rendered to an investment value, or worth, standard). However, employing the share of the land element as a calibrating parameter (Cell D138 of the “DCF” tab), along with the discount rate for the land element-related cashflows (Cell D139), can align the resulting estimate of land value with the actual market price or market valuation.

- Macroeconomic schedule (Lines 5–8 of the DCF tab), which is needed in the nominal model to record expectations of inflation for construction costs and the primary market prices

- Investment cost schedule (Lines 10–28): It is used to translate unit construction costs from the respective separate tab of the model into inflation-adjusted construction cost amounts at the overall development level and arrange their temporal placement across the forecast period span of the model. The investment cost schedule is coupled with the Investment cost write-down account, which is then used to write down investment costs to the P&L statement (Lines 67–74) proportionate to the recognition of revenue.

- Financing cost schedule (Lines 30–38) to project debt balances for balance sheet purposes and estimate interest expenses on the debt-financed portion of the investment costs (In contrast to construction costs proper, note that in both versions of the model, all the operating costs of the project (in Lines 40–46 of the DCF tab, principally, administrative and marketing expenses, plus the entirety of the land costs, i.e., land acquisition at auction and the development land taxes) are assumed to be covered by the developer’s equity.

- Operating cost schedule (Lines 40–46) comprising, principally, feasibility and design, administrative and marketing expenses, plus the development land taxes for the period of construction. Due to their operational nature, and in contrast to the investment costs, these costs are assumed to be covered by the developer’s equity only.

- Schedule of cash receipts from the project (Lines 49–60) recording the timing and amounts of cash flows related to property unit sales and calibrating the progressive extent of percentage discounts along the temporal profile of off-plan advance payments, as is customary in Tashkent. The DDY version of the model also features an auxiliary schedule on Lines 62–65 to record the movement of buyers’ advances in and out of the deferred income account that features in the balance sheet (on Line 121).

3.2. Distinguishing Features in the DDY (Baseline) and Escrow (New Policy) Variants of the Model

4. Results and Findings

4.1. Effect on Developers

4.2. Effect on the Apartment Buyers and the Mortgage Market

4.3. Effect on the Banking Sector

4.4. Land Valuation Implications

4.5. Fiscal Implications of Escrow Plans for Government Revenue

5. Discussion

Efficiency Considerations for Escrow Policy and Policy Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al Maktoum, M.R. Law No. (8) of 2007 Concerning Escrow Accounts for Real Estate Development in the Emirate of Dubai. Available online: https://dlp.dubai.gov.ae/Legislation%20Reference/2007/Law%20No.%20%288%29%20of%202007.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- PWC. Saudi Arabia’s Off-Plan Market: A Driving Force Fueling a Vibrant and Sustainable Society. 2024. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/m1/en/publications/documents/2024/saudi-arabia-off-plan-market.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- McDaid, M. The Impact of Dubai Escrow Regulation on Project Investment and Delivery. Master’s Thesis, School of the Built Environment College of Science and Technology, University of Salford, Salford, UK, 2016. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/31537148/The_impact_of_Dubai_Escrow_regulation_on_project_investment_and_delivery (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Oman. Oman Sultani Decree No. 30/2018 Promulgating the Regulation Concerning the Calculation of Guarantee for Real Estate Development Projects. 2018. Available online: https://www.lexismiddleeast.com/law/Oman/SultaniDecree_30_2018 (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- S&P Global. As The Escrow Flies: China Developers Navigate Convoluted Rules on Presales, NEWS COMMENTS 20 January 2022|7 October 2022. Available online: https://www.spglobal.com/ratings/en/research/articles/220120-as-the-escrow-flies-china-developers-navigate-convoluted-rules-on-presales-12249185 (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- RERA. All About RERA Escrow Account. 2023. Available online: https://razorpay.com/learn/business-banking/rera-escrow-account/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Matveeva, M.V. Impact of escrow accounts on construction rates. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 880, p. 012119. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1757-899X/880/1/012119/pdf (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- HBA. Housing Developers (Housing Development Account) Regulations, 1991 pu(a) 231/1991. 1991. Available online: https://www.hba.org.my/laws/accounts_reg/PU%28A%29%20231-1991.htm (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- NGO & Partners. Key Changes in the Law on Real Estate Business 2023, 16 April 2025, Legal News. 2025. Available online: https://ngo-partners.com/en/tin-tuc/key-changes-in-the-law-on-real-estate-business-2023/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Warwick. Poland: End of the Transitional Period for Developers: New Obligations and Application of the Old Act, 22 August 2024 Warwick Legal Framework. 2024. Available online: https://www.warwicklegal.com/news/797/poland-end-of-the-transitional-period-for-developers-new-obligations-and-application-of-the-old-act?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- CMWP. TASHKENT RESIDENTIAL IQ Knowledge Base 1Q 2024, Commonwealth Partners Report. 2024. Available online: https://cmwp.uz/iq (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Bhagwat, S.; Thakur, M.S. Effect of RERA on Liquidity of Real Estate Developers. JETIR 2019, 6, 1180–1188. Available online: https://www.jetir.org/papers/JETIR1904U47.pdf#:~:text=capital,the%20access%20to%20free%20working (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Mohamadi, F. Basics of Financial Modeling. In Introduction to Project Finance in Renewable Energy Infrastructure; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spot.UZ. Tashkent Property Prices Are Set to Go for a Decline—CEIR Analysis 29 April 2025, 16:59 Economics. 2025. Available online: https://www.spot.uz/ru/2025/04/29/real-estate-mar25/ (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Abduljabbar, R. Economic Assessment of Off-Plan Real-Estate Policy in Saudi Arabia–2009–2019. Ph.D. Thesis, International School of Management, Muscat, Oman, 2021. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/367520365_Economic_Assessment_of_Off-plan_Real-estate_policy_in_Saudi_-_2009-2019 (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Suhaib, S.K.; Mushtaq, A.; Layth, S.K.; Temple, C.O. Problems and Factors Affecting Property Developers Performance in the Dubai Construction Industry. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2018, 8, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pylypenko, P.; Synchuk, S. Foreign practice of using an escrow account contract. Experience of the USA and the UK. Actual Probl. Law 2023, 4, 79–83. Available online: https://appj.wunu.edu.ua/index.php/apl/article/view/1724/1782 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Tarhonii, Y. Escrow Agent as a Party to an Agreement of Escrow Account (escrow). Actual Probl. Law 2013, 2, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimaru, K.K. The Effectiveness of Financing Real Estate Development Through Off-plan Sales: Case Study of Selected Residential Developments Within Nairobi County. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. Available online: https://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/handle/11295/104819 (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Shepina, S.V. Transformation of the individual housing construction market: Introduction of escrow accounts and changes family mortgage terms. Ekon. Uprav. Prob. Resh. 2025, 1, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chayetskiy, A.; Evdokimenko, A.; Kogan, A. Modelling the Escrow Financing Influence on the Efficiency of Development Project. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 953, p. 012045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantyukov, I.A.; Opekunov, V.A. Research of the problems of project financing of construction of residential real estate using the escrow account mechanism. Vestnik Univer. 2021, 176–182. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketova, K.; Vavilova, D. Optimization of Financial Flows in a Building Company Using an Escrow Account in the Russian Federation. In Recent Research in Control Engineering and Decision Making; Studies in Systems; Decision and Control; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havard, T.M. Argus Developer in Practice: Real Estate Development Modeling in the Real World, 1st ed.; Apress: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 340. [Google Scholar]

- Efinancialmodels. Property Development & Rental Financial Projection 3 Statement Model. 2024. Available online: https://www.efinancialmodels.com/downloads/property-development-amp-rental-financial-projection-3-statement-model-345642/ (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Marshall, A. Principles of Economics, 8th ed.; Macmillan: London, UK, 1920; Volume IV, XIII, 1, p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Co-Invest. Residential Developments: Aggregated Unit Construction Costs for EEU; Co-Invest Option, Co-invest: Astana, Kazakhstan, 2022; p. 226. Available online: https://www.shop.coinvest.ru/index.php?_route_=EACbooks&product_id=72 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Ozsoy, O.; Ahunov, M. Hedonic housing values in a transition economy: The case of Tashkent. Int. J. Hous. Mark. Anal. 2023, 16, 853–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artemenkov, A. Applied Corporate Finance: A Modern Practical Guide, Uzbekistan Ed.; Reach Publishers: Durban, South Africa, 2023; pp. 137–156. [Google Scholar]

- Tham, J.; Velez-Pareja, I. Principles of Cash Flow Valuation: An Integrate d Market-Based Approach; Elsevier Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 223–242. [Google Scholar]

- Codosero Rodas, J.M.; Naranjo Gómez, J.M.; Castanho, R.A.; Cabezas, J. Land Valuation Sustainable Model of Urban Planning Development: A Case Study in Badajoz, Spain. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CMWP Webinar. How to Prepare for the Introduction of Escrow Plans in Uzbekistan, Recorded Webinar, 19 March 2025. Available online: https://cmwp.uz/article/vebinar-kak-podgotovitsia-k-vvedeniiu-eskrou-scetov-v-uzbekistane (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Ranking.kz. Enlargement, Concentration and Investment Growth: What Goes on in the Uzbekistan Construction Industry? 25 April 2025. Available online: https://ranking.kz/reviews/industries/ukrupnenie-kontsentratsiya-i-rost-investitsiy-chto-proishodit-v-stroitelnoy-otrasli-uzbekistana.html (accessed on 29 March 2025). (In Russian).

- Bank of England. Money Creation in the Modern Economy. Q. Bull. 2014. Available online: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/quarterly-bulletin/2014/q1/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Araya, F. Agent based modelling: A tool for construction engineering and management? Rev. Ing. Construcción 2020, 35, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Starting Transition Date | Source |

|---|---|---|

| United Arab Emirates | 2008 | [1] |

| Saudi Arabia | 2017 | [2,3] |

| Oman | 2018 | [4] |

| China | Since the 2010s (implementation of schemes at a local level) | [5] |

| India | 2017 | [6] |

| Russia | 2020 | [7] |

| Malaysia | 1991 | [8] |

| Vietnam | 2024 | [9] |

| Poland | 2024 | [10] |

| Item | Extant DDY Scheme (Pre-2026) | New Escrow Scheme (Effective 2026) |

|---|---|---|

| Legal Basis | Based on off-plan investment contracts under the “DDY” (Ulushdorlik asosida shartnoma) legal arrangement. | Mandated by Presidential Decree YP-11 (27 January 2025), effective 1 January 2026 |

| Buyer Protection | 100% buyer’s risk on off-plans: Limited safeguards in case of developer default or project delay. However, unlike characteristic delays by a year or two, the actual cases of full default and project abandonment are rare in Tashkent. | Buyer’s risk largely eliminated: Enhanced protection—apartment buyer’s advances held in escrow bank custody are secure and can’t be re-allocated by banks towards any risky investments. |

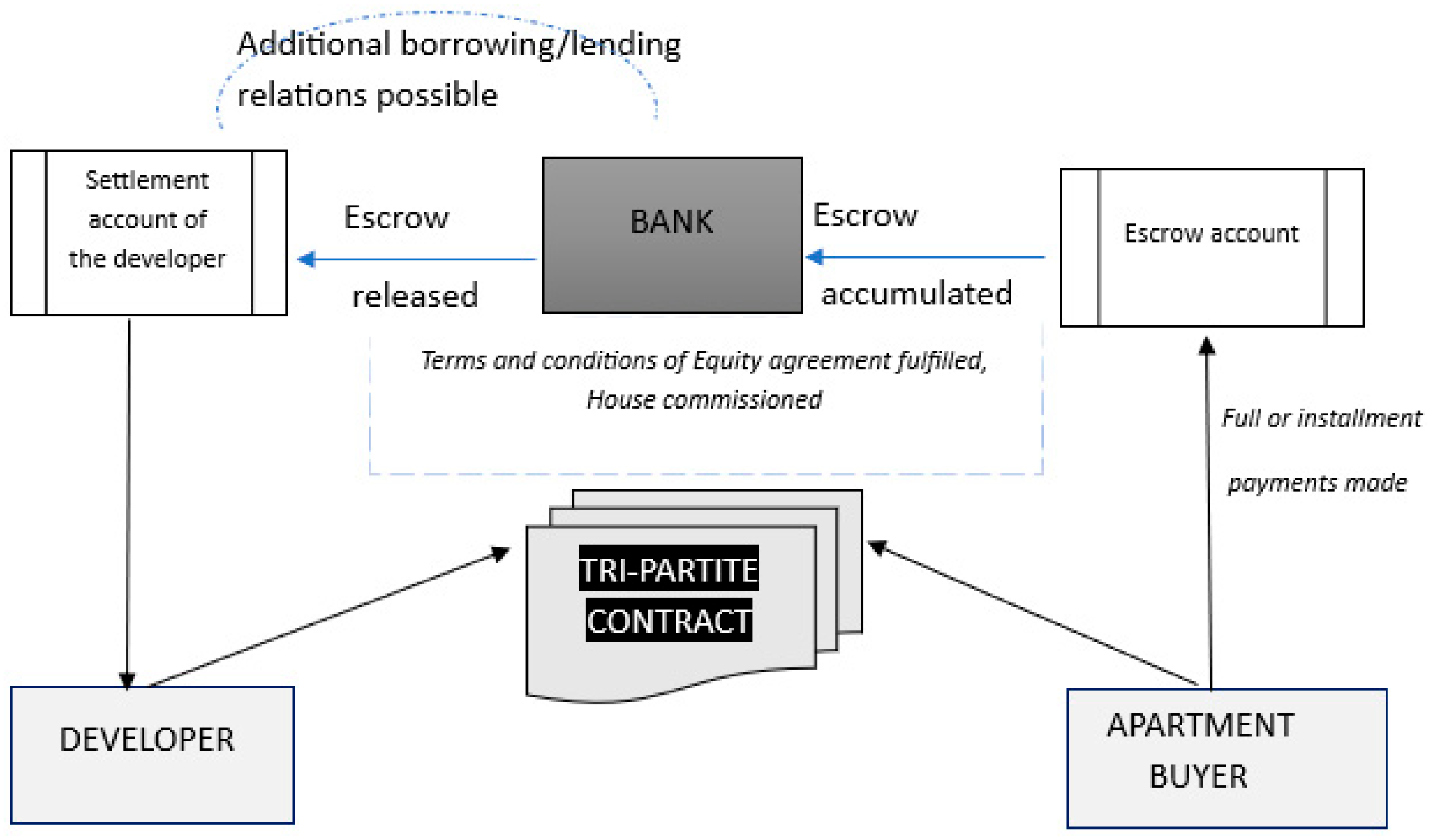

| Fund Flow Mechanism | Front-loaded: Buyers’ advance payments were made directly to the developer’s account and treated as prepayments/advances in the accounting system of the developer. | Back-loaded: buyers will deposit funds (only in sum, the national currency) into an escrow account managed by a licensed bank. The funds will be frozen in the account for the duration of the construction process, yielding interest to the developer that is not expected to exceed the central bank refinancing rate. |

| Developer Financing Model | Advance-based: Buyer advances served as primary construction financing. Needing the funds, developers were eager to offer steep discounts to early-bird off-plan buyers (up to 30% off the market price at the earliest development stage). These discounts are by no means unprecedented for the developing property markets. Kimaru (2018) reports even higher off-plan discounts for Nairobi in Kenya. | Leverage/Debt-based: developers will have to secure working capital loans from the escrow bank to finance construction and tide them over financially until the unfreezing of escrow funds. Since apartment buyers are out of the picture in the fundraising matter, off-plan discounts will disappear as a feature. |

| External project supervision | Government-supervised: Under the old DDY mechanism, projects had to be registered, but the actual government supervision of projects was minimal. | Government and bank supervised: Escrow bank employees will exercise due diligence on the flow of developers’ funds. Sub-standard construction materials won’t be deliverable for cash anymore. |

| Parameter | Description | Additional Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Model type and description | Nominal three-statement, sum-denominated model (The Uzbekistan national currency is called the Uzbek sum), with the unit of measurement being 13,000 sum (equivalent to approx. $1 as at the analysis date—10 April 2025). The model is projected with data at a quarterly frequency (with a total of 12 project quarters till the end) and derives cashflows using the direct technique to cashflow derivation [29] | Key inflation assumptions: Inflation for construction costs: 15% p.a. Inflation on the primary apartment and commercial property market is 15% p.a. (the assumption of zero real growth of the price level over the next 2 years). (The nominal rate of 15% p.a. is also used as a policy assumption for the depositary rate on escrowed funds in the escrow variant of the model). |

| Model duration (forecast period) | The forecast period is made up of 12 quarterly intervals. Each construction phase takes 2 years (8 quarters) | Note that the representative project is undertaken in two construction phases, set apart at a 6-month interval. |

| Additional features of the model | The model accounts for the project management costs and payroll, initial land acquisition, Tashkent central zone land tax, VAT timing and offsets, as well as for the profit taxation and Tax-loss Carryforwards (at 50% offset rate as per the Tax Code). | It is assumed that any municipal commitments to infrastructure and service developments do not encumber the developer. Project management costs and payroll are assumed to be funded by the developer’s equity |

| Model outputs | Model outputs include: Free cash flows to Equity (FCFEs), Free cash flows to the project’s overall invested capital (FCFFs), FCFFs split between the building and the land component, DCF-based development land valuation, as well as the associated project efficiency metrics, including Net present value (NPV) and the cashflow-based Internal rate of return (IRR), namely NPV(FCFE), IRR (FCFE). | The model also provides proformas of the three accounting statements and related ratios. Development land valuation is based on capitalizing a certain proportion of positive-valued FCFFs and FCFEs from the project. |

| DDY Model (as per Extant Regulations) | Escrow Model for YP-11 Transition (with 100% Reservation of Funds and the Single Terminal Milestone at the Cadastral Registration of the Development) | ||

| Model repository: https://disk.yandex.ru/d/HXcNukK1qgYbEQ, accessed on 10 April 2025 (for both variants of the model) | |||

| Feature | Commentary | Feature | Commentary |

| Treatment of advances from apartment buyers | Represents actual cash flows received by the developer (Line 94 of DCF tab) as incoming advances and balance sheet liabilities (Line 121). A deferred income account schedule is used in the model for that (Lines 62–65). The amount and timing of the advances are calibrated in the “Project receipts/revenues schedule” (Lines 50–51 and 55–56), specifying the periodic breakdown of prepayments matched to the extended off-plan discount percentages. | Model treatment of funds held in escrow | As all the buyers’ advances are paid into the escrow bank to be released to the developer at the cadastral registration of the development, both the cash flow from unit sales and the associated revenue are recorded simultaneously at the terminal point (the last quarter) of the model. Unless the project is 100% equity-funded and the developer needs no recourse to escrow bank loans, any originating cash shortfall during the construction process is covered by the loan obtainable from the escrow bank (Line 31) The interest rate on escrow bank loans is assumed at 24% p.a. (Cell D 37), while the depository rate of interest on the frozen escrow balances (implied in Lines 56 and 86) is assumed to be accrued to provide compensation not in excess of the projected inflation (i.e., at 15% p.a). |

| Recognition of revenue and construction costs in the project’s P&L statement | Project revenue is recognized at cadastral registration of the property (in the final year): at this moment, all the advances received are transferred to the project’s revenue in the P&L statement (Line 76). In line with the received accounting treatment, the project’s investment costs are also written off against the revenue at that time (Lines 74, 77). | Recognition of revenue and construction costs in the project’s P&L statement | The treatment is similar to one in the DDY model: project revenue is recognized the moment the escrowed funds are unfrozen at the cadastral registration milestone. Investment costs are also written off against the revenue at that moment. It is to be noted, however, that due to the disappearance of off-plan discounts characteristic of the old (DDY) scheme, the profile of revenue (and CF streams) is not just back-loaded; it is also expected to be greater in total value. |

| Sales VAT treatment | Is a part of the developer’s cash flow to be received simultaneously with the developer’s advances (Line 97) | Sales VAT treatment | Sales VAT on escrows is received by the developer as actual cashflow simultaneously with the main proceeds at the completion of the single milestone. |

| Item | Baseline (DDY) | Alternative (Escrow) | Difference Between the Two Variants |

| 100% Equity funding for investment (construction) costs of the project: | |||

| FCFE-based Internal rate of return (IRR), %p.a. (nominal) | 32% | 27% | −5% p.a. |

| Initial equity contributions, including land | $9.3 mln | $9.3 mln. | Unchanged |

| Additional equity contributions, $ mln. | $23.5 mln. | $57.7 mln. | An increase of 2.4 times |

| Total equity contribution, $ mln. | $32.8 * mln. | $67.0 * mln. | An increase of 2 times |

| 50% debt funding for investment (construction) costs of the project: | |||

| FCFE-based Internal rate of return (IRR), % p.a. (nominal) | 23% | 29% ** | +6% p.a. |

| Initial equity contributions, including land | $14.3 mln. | $9.2 mln | A reduction of 35% |

| Additional equity contributions | $6.0 mln. | $ 36.4 mln. | An increase of 6 times |

| Total equity contribution | $20.3 mln. | $45.6 mln. | An increase of 2.2 times |

| Proforma P&L Items (Totals over the Construction Period) | DDY Variant | Escrow Variant | Difference (Escrow over DDY) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $ equivalent | Vertical ratios, % to revenue | $ equivalent | Vertical ratios, % to revenue | ||

| Revenue | 138,722,086 | 100% | 149,655,282 | 100% | 7.88% |

| Investment costs (including demolition and infrastructure) | 90,193,492 | 65% | 90,193,492 | 60% | 0.00% |

| Selling and administrative expenses | 6,074,074 | 4% | 6,074,074 | 4% | 0.00% |

| EBITDA | 57,236,568 | 41% | 57,087,719 | 38% | −0.26% |

| Interest on loan (@ 24% p.a.) | 4,584,839 | 3% | 8,588,264 | 6% | 87.32% |

| Pre-tax profit | 40,424,852 | 29% | 48,499,455 | 32% | 19.97% |

| Tax loss offsets (TLCs) | 8,135,709 | 9,404,028 | 15.59% | ||

| Profit tax | 6,063,728 | 4% | 7,274,918 | 5% | 19.97% |

| Net earnings | 34,361,125 | 25% | 41,224,537 | 28% | 19.97% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Artemenkov, A.; Saccal, A. Financial Modelling of Transition to Escrow Schemes in Urban Residential Construction: A Case Study of Tashkent City. Buildings 2025, 15, 2843. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15162843

Artemenkov A, Saccal A. Financial Modelling of Transition to Escrow Schemes in Urban Residential Construction: A Case Study of Tashkent City. Buildings. 2025; 15(16):2843. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15162843

Chicago/Turabian StyleArtemenkov, Andrey, and Alessandro Saccal. 2025. "Financial Modelling of Transition to Escrow Schemes in Urban Residential Construction: A Case Study of Tashkent City" Buildings 15, no. 16: 2843. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15162843

APA StyleArtemenkov, A., & Saccal, A. (2025). Financial Modelling of Transition to Escrow Schemes in Urban Residential Construction: A Case Study of Tashkent City. Buildings, 15(16), 2843. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15162843