Development and Initial Validation of Healing and Therapeutic Design Indices and Scale for Measuring Health of Sub-Healthy Tourist Populations in Hot Spring Tourism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Tourism and Wellness

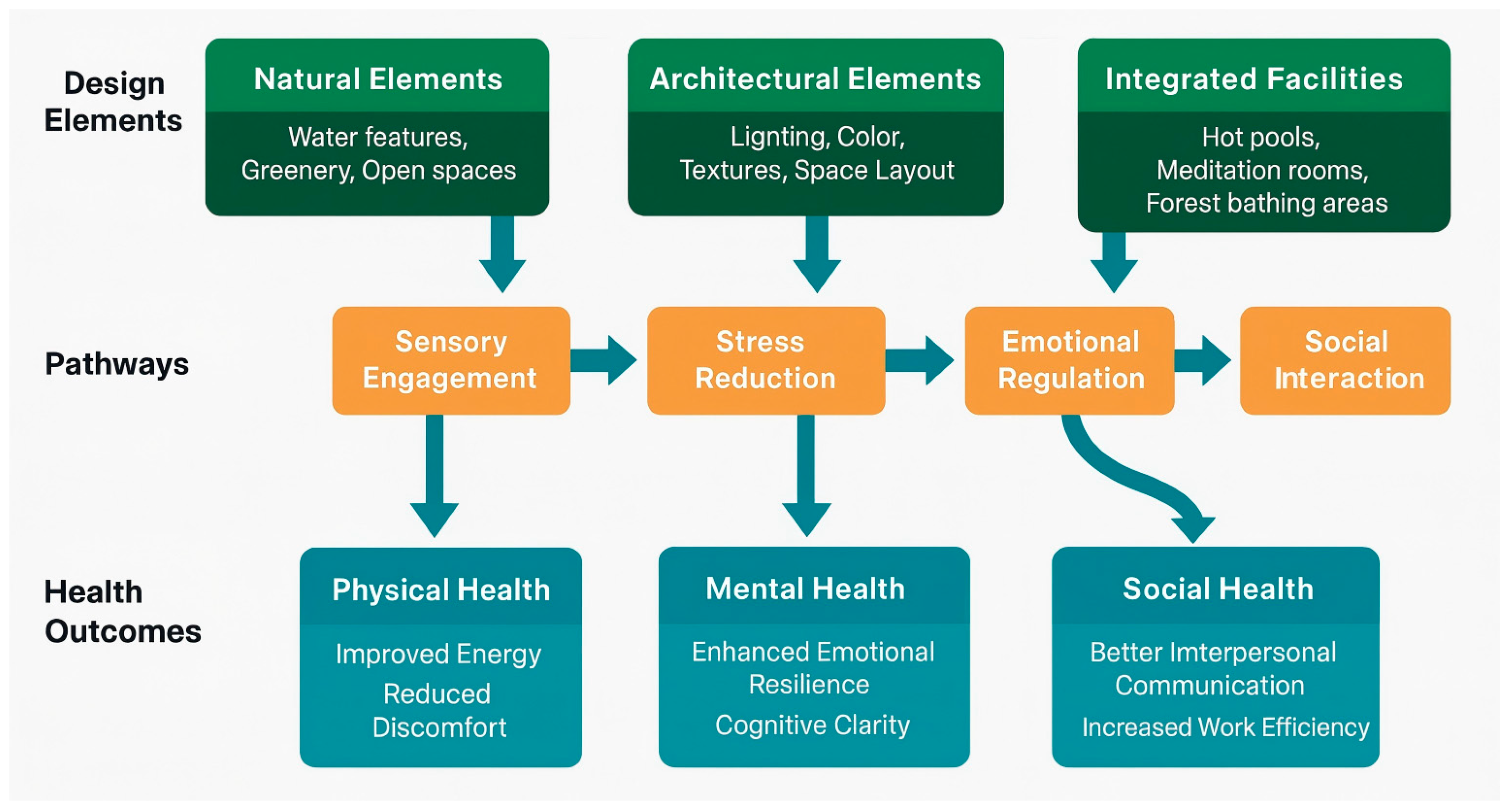

2.2. Hot Spring Tourism Environmental Design

3. Research Methods

4. Findings

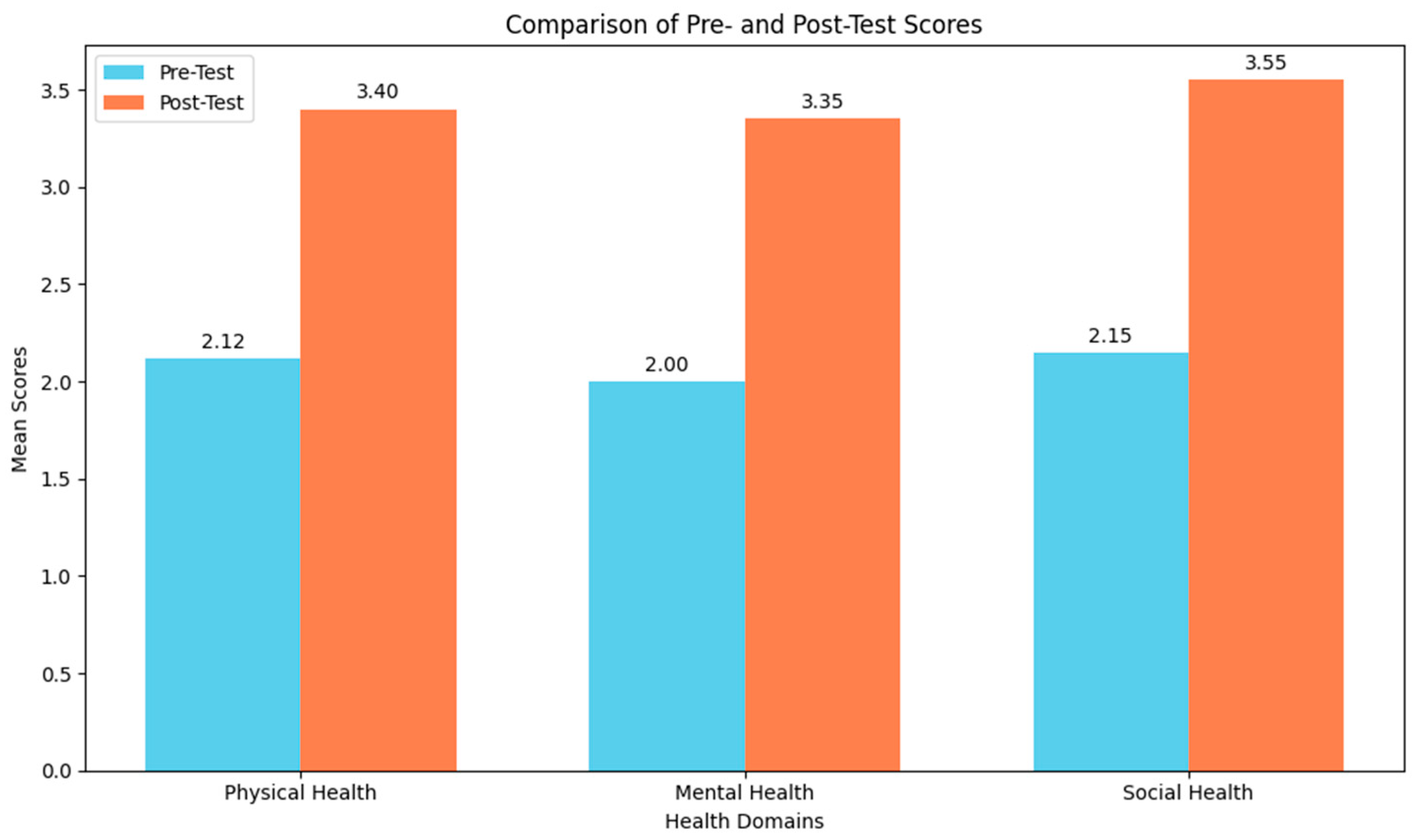

4.1. Empirical Test

4.2. Data Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limits and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, M.K.; Diekmann, A. Tourism and wellbeing. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 66, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hapsara, H.R. World Health Organization (WHO): Global Health Situation; World Health Organization (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, S.N.; Sechrist, K.R.; Pender, N.J. The health-promoting lifestyle profile: Development and psychometric characteristics. Nurs. Res. 1987, 36, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.W.; Li, C. The process of constructing a health tourism destination index. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazaly, M.; Badokhon, D.; Alyamani, N.; Alnumani, S. Healing architecture. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2022, 10, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaeil, E.M.H.; Sobaih, A.E.E. Enhancing healing environment and sustainable finishing materials in healthcare buildings. Buildings 2022, 12, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sha, S.; Shen, W.; Yang, Z.; Dong, L.; Li, T. Can Rehabilitative Travel Mobility improve the Quality of Life of Seasonal Affective Disorder Tourists? Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 976590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark-Kennedy, J.; Cohen, M. Indulgence or therapy? Exploring the characteristics, motivations and experiences of hot springs bathers in Victoria, Australia. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golshiri, Z.; Roknodineftekhari, A.; Pourtaheri, M. Modeling of health tourism development in rural areas of Iran (Hot springs). J. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2015, 3, 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hasler, B.P.; Allen, J.; Sbarra, D.A.; Bootzin, R.R.; Bernert, R.A. Morningness–eveningness and depression: Preliminary evidence for the role of the behavioral activation system and positive affect. Psychiatry Res. 2010, 176, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christoua, P.; Simillidou, A. Tourist experience: The catalyst role of tourism in comforting melancholy, or not. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, Z.; Osmani, M. The relationship between sustainable built environment, art therapy and therapeutic design in promoting health and well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, Z.; Liang, M.; Liu, Y.; Osmani, M.; Demian, P. A conceptual framework for blockchain enhanced information modeling for healing and therapeutic design. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Browne, A.L.; Iossifova, D. A socio-material approach to resource consumption and environmental sustainability of tourist accommodations in a Chinese hot spring town. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 30, 424–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salingaros, N.A. Façade Psychology Is Hardwired: AI Selects Windows Supporting Health. Buildings 2025, 15, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Linking Architecture and Emotions: Sensory Dynamics and Methodological Innovations; Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya: Barcelona, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Lin, X.; Li, S.; Huang, M.; Ren, Z.; Song, Q. Restorative Environment Design Drives Well-Being in Sustainable Elderly Day Care Centres. Buildings 2025, 15, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Grellier, J.; Wheeler, B.W.; Hartig, T.; Warber, S.L.; Bone, A.; Depledge, M.H.; Fleming, L.E. Spending at least 120 minutes a week in nature is associated with good health and wellbeing. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus, C.C.; Sachs, N.A. Therapeutic Landscapes: An Evidence-Based Approach to Designing Healing Gardens and Restorative Outdoor Spaces; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Siah, C.J.R.; Goh, Y.S.; Lee, J.; Poon, S.N.; Ow Yong, J.Q.Y.; Tam, W.S.W. The effects of forest bathing on psychological well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 32, 1038–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, N.; Saito, H.; Fujiwara, A.; Horiuchi, M. The effect of forest bathing on mental health: A systematic review of clinical trials. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2020, 25, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.; Puczkó, L. Health, Tourism and Hospitality: Spas, Wellness and Medical Travel; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Zhai, Y.; Chang, H. Research on the Combined Treatment of Hot Spring Hydrotherapy and Psychological Care for Essential Hypertension in Wulongbei Area. Chin. J. Health Care Med. 2016, 18, 148–149. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Yang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Yang, Z.; Ye, B. The curative effect of spa and improve sleep quality of elderly recuperate. J. South China Natl. Def. Med. J. 2019, 33, 488–489+517. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, S. Research on Tourists’ Perceived Value and Product Optimization of Regional Hot Spring Tourism Products: A Case Study of Heyuan City, Guangdong Province. Wuxi Bus. Vocat. Coll. J. 2023, 23, 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, W.; Chen, G.; Hu, X. Research on the Impact of Local Attachment on Psychological Recovery of Tourists in Tourist Resorts: The Mediating Role of Environmental Restorative Perception. Tour. Sci. 2021, 35, 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; You, D.; Pan, M.; Chi, M.; Huang, Q.; Lan, S. Research on the Relationship between Recreational Place Perception and Restorative Perception: A Case Study of Fuzhou Hot Spring Park. Tour. Trib. 2017, 32, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Pyke, S.; Hartwell, H.; Blake, A.; Hemingway, A. Exploring well-being as a tourism product resource. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochiai, H.; Ikei, H.; Song, C.; Kobayashi, M.; Takamatsu, A.; Miura, T.; Kagawa, T.; Li, Q.; Kumeda, S.; Imai, M.; et al. Physiological and psychological effects of forest therapy on middle-age males with high-normal blood pressure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 2532–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, B.W.; White, M.; Stahl-Timmins, W.; Depledge, M.H. Does living by the coast improve health and wellbeing? Health Place 2012, 18, 1198–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L. The relationship between nature-based tourism and autonomic nervous system function among older adults. J. Travel Med. 2014, 21, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.M.; Elliott, F.; Oates, L.; Schembri, A.; Mantri, N. Do Wellness Tourists Get Well? An Observational Study of Multiple Dimensions of Health and Well-Being After a Week-Long Retreat. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2017, 23, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Petrick, J.F. Family and Relationship Benefits of Travel Experiences A Literature Review. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Tang, X.; Song, J. The relationship among life stress perception, leisure adjustment strategy and health of rural tourists. Tour. Trib. 2010, 25, 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Philippa, H.J. Managing cancer: The role of holiday taking. J. Travel Med. 2003, 10, 170–176. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, R.; Yan, J.; Cui, Y.; Song, D.; Yin, X.; Sun, N. Studies on the Specificity of Outdoor Thermal Comfort during the Warm Season in High-Density Urban Areas. Buildings 2023, 13, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Lai, W.; Wu, Z. Study on Xiamen’s Spring and Winter Thermal Comfort of Outdoor Sports Space in the Residential Community. Buildings 2023, 13, 2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymańska, E. Construction the Model of Health Tourism Innovativeness. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 213, 1008–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayili, M.; Akca, H.; Duman, T.; Esengun, K. Psoriasis treatment via doctor fishes as part of health tourism: A case study of Kangal Fish Spring, Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 625–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Ikei, H.; Kobayashi, M.; Miura, T.; Taue, M.; Kagawa, T.; Li, Q.; Kumeda, S.; Imai, M.; Miyazaki, Y.; et al. Effect of forest walking on autonomic nervous system activity in middle-aged hypertensive individuals: A pilot study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 2687–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, B.-J.; Ohira, T.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Acute Effects of Exposure to a Traditional Rural Environment on Urban Dwellers: A Crossover Field Study in Terraced Farmland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 1874–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, A.; Schofield, P.; Low, T. Women’s mountaineering: Accessing participation benefits through constraint negotiation strategies. Leis. Stud. 2020, 39, 721–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J.; Woo, E.; Kim, H. Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, N.; Pritchard, A.; Sedgley, D. Social tourism and well-being in later life. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 52, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, A. Tourism and health: Using positive psychology principles to maximise participants’ wellbeing outcomes-a design concept for charity challenge tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 382–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohe, Y.; Ikei, H.; Song, C.; Miyazaki, Y. Evaluating the relaxation effects of emerging forest-therapy tourism: A multidisciplinary approach. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 322–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R.; Westaway, D. Mental health rescue effects of women’s outdoor tourism: A role in COVID-19 recovery. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 103041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Lan, S. Key route planning models of natural hot spring tourism in coastal cities. J. Coast. Res. 2020, 103, 1084–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.H.; Chang, F.H.; Wu, C. Investigating the wellness tourism factors in hot spring hotel customer service. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 1092–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L. Tourist choice of sustainable hot springs tourism under post-COVID-19 pandemic period: A case in Colorado. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H. Effects of cuisine experience, psychological well-being, and self-health perception on the revisit intention of hot springs tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2014, 38, 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockx, L.; Francken, N. Extending the concept of the resource curse: Natural resources and public spending on health. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 108, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, S.; Staats, H.; Corraliza, J.A. Restorative environments and health. In Handbook of Environmental Psychology and Quality of Life Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 127–148. [Google Scholar]

- Souter-Brown, G. Landscape and Urban Design for Health and Well-Being: Using Healing, Sensory and Therapeutic Gardens; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Feng, L.; Luo, R.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, X.; Lu, Y.; Wei, Q. Reliability and validity of sub-health Rating Scale. Acta South. Med. Univ. 2011, 31, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld, R.; Williams, J.; Spitzer, R.L.; Calabrese, J.R.; Flynn, L.; Keck, P.E.; Lewis, L.; McElroy, S.L.; Post, R.M.; Rapport, D.J.; et al. Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: The Mood Disorder Questionnaire. Am. J. Psychiatry 2000, 157, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melzer, J.; Rostock, M.; Brignoli, R.; Keck, M.E.; Saller, R. Preliminary data of a HAMD-17 validated symptom scale derived from the ICD-10 to diagnose depression in outpatients. Forsch. Komplementuärmedizin/Res. Complement. Med. 2012, 19, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roecklein, K.A.; Carney, C.E.; Wong, P.M.; Steiner, J.L.; Hasler, B.P.; Franzen, P.L. The role of beliefs and attitudes about sleep in seasonal and nonseasonal mood disorder, and nondepressed controls. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 150, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinese Medical Association of Psychiatry. CCMD-3 Chinese Classification and Diagnostic Criteria for Mental Disorders; Shandong Science and Technology Press: Jinan, China, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Yuan, C.; Angst, J.; Liu, T.; Liao, C.; Rong, H. Application of Chinese version of 32-item hypomania symptom checklist in patients with bipolar I disorder. Chin. Behav. Med. Sci. 2008, 17, 950–952. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G. How to evaluate the therapeutic effect of depression—Introduction of REMIT Scale. Chin. Med. J. 2012, 92, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Rohan, K.J.; Roecklein, K.A.; Lindsey, K.T.; Johnson, L.G.; Lippy, R.D.; Lacy, T.J.; Barton, F.B. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy, light therapy, and their combination for seasonal affective disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 75, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Theoretical and Experimental Study on “The Liver Responds to Spring, Regulates Catharsis and Regulates Emotion”; The Beijing University of Chinese Medicine: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis, S.L.; Smale, B. An Examination of Relationship Between Psychological Well-Being and Depression and Leisure Activity Participation Among Older Adults. Loisir Soc. 1995, 18, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, M.G.; Kross, E.; Krpan, K.M.; Askren, M.K.; Burson, A.; Deldin, P.J.; Kaplan, S.; Sherdell, L.; Gotlib, I.H.; Jonides, J. Interacting with nature improves cognition and affect for individuals with depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 140, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Evans, G.W.; Jamner, L.D.; Davis, D.S.; Gärling, T. Tracking restoration in natural and urban field settings. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melrose, S. Seasonal Affective Disorder: An Overview of Assessment and Treatment Approaches. Depress. Res Treat 2015, 2015, 178564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Q.; Feng, L.; Zhang, G.; Liu, M.; Wang, J. Research progress of seasonal affective disorder and light therapy. Chin. Gen. Pract. 2020, 23, 3363–3368. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M. Questionnaire Statistical Analysis Practice: SPSS Operation and Application; Chongqing University Press: Chongqing, China, 2010; pp. 217–232. [Google Scholar]

- White, M.; Smith, A.; Humphryes, K.; Pahl, S.; Snelling, D.; Depledge, M. Blue space: The importance of water for preference, affect, and restorativeness ratings of natural and built scenes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Liu, J. Effect of healthy lifestyle on psychological well-being of hot spring tourists. J. Tour. Res. 2007, 13, 213–233. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Cui, X. An empirical analysis of tourist activities and tourists’ mental health. Acta Beijing Int. Stud. Univ. 2013, 35, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

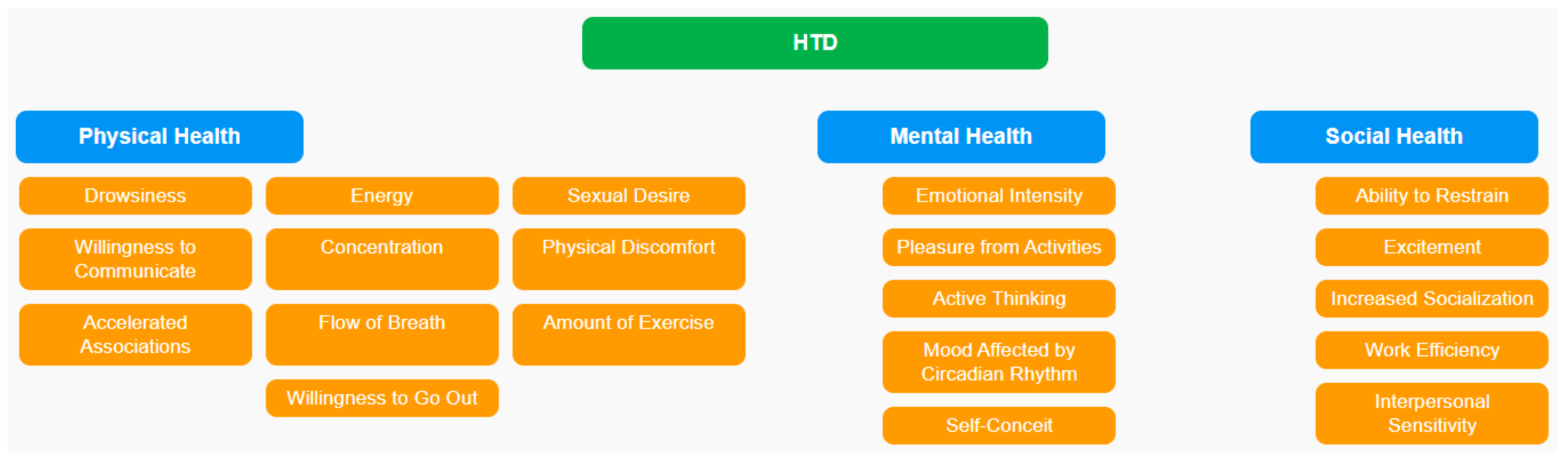

| Construct | Factor | Design Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Physical health | Sleep length Energy Sexual desire Talkativeness Concentration Body pain Accelerated associations Fluttering of ideas Amount of exercise Frequency of going out | Chinese Medical Association of Psychiatry [60], Yang et al. [61], Wang [62], Rohan et al. [63] |

| Mental health | Emotional intensity Pleasure from activities Creativity Mood affected by circadian rhythm Exaggerated self-evaluation | Zhang [64], Dupuis and Smale [65], Berman et al. [66], Hartig [67] |

| Social health | Recklessness Irritability Socialization frequency Work efficiency Social competence | Sherri [68] and Zhai et al. [69] |

| Expert | Gender | Education | Years of Experience | Background |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | Doctoral degree | 15 | Human geography |

| 2 | M | Doctoral degree | 16 | Sustainable tourism |

| 3 | F | Doctoral degree | 18 | Health and wellness tourism |

| 4 | F | Master’s degree | 12 | Urban and rural planning |

| 5 | M | Doctoral degree | 30 | Public health |

| 6 | M | Doctoral degree | 21 | Nutrition science |

| 7 | M | Doctoral degree | 25 | Psychiatry |

| 8 | F | Master’s degree | 20 | Traditional Chinese medicine and health preservation |

| 9 | F | Master’s degree | 10 | Sustainable tourism |

| 10 | M | Doctoral degree | 15 | Architectural design |

| 11 | M | Doctoral degree | 26 | Human geography |

| 12 | M | Master’s degree | 12 | Landscape architecture |

| 13 | F | Master’s degree | 11 | Sports science and physical education |

| 14 | F | Doctoral degree | 10 | Traditional Chinese medicine rehabilitation |

| 15 | M | Doctoral degree | 18 | Psychology |

| 16 | F | Doctoral degree | 16 | Health and physical education |

| 17 | F | Master’s degree | 15 | Environmental design |

| 18 | M | Doctoral degree | 24 | Leisure management |

| System Layer | Indicator Layer | First Round | System Layer | Indicator Layer | Second Round | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | IQR | Stability | Mean | IQR | Stability | ||||

| Physical health | Sleep length | 4.16 | 1.00 | 87.8% | Physical health | Drowsiness | 4.45 | 1.00 | 88.6% |

| Energy | 4.35 | 1.00 | 87.8% | Energy | 4.48 | 1.00 | 88.6% | ||

| Sexual desire | 4.10 | 1.00 | 85.5% | Sexual desire | 4.29 | 1.00 | 86.5% | ||

| Talkativeness | 4.25 | 1.00 | 82.6% | Willingness to communicate | 4.31 | 1.00 | 88.6% | ||

| Concentration | 4.20 | 1.00 | 85.5% | Concentration | 4.52 | 1.00 | 86.5% | ||

| Body pain | 4.10 | 1.00 | 82.9% | Physical discomfort | 4.26 | 1.00 | 82.6% | ||

| Accelerated associations | 4.04 | 1.00 | 85.5% | Accelerated associations | 3.98 | 1.00 | 86.5% | ||

| Fluttering of ideas | 3.88 | 1.00 | 72.5% | Flow of breath | 4.06 | 1.00 | 82.6% | ||

| Amount of exercise | 4.26 | 1.00 | 85.5% | Amount of exercise | 4.30 | 1.00 | 85.5% | ||

| Frequency of going out | 4.07 | 1.00 | 81.0% | Willingness to go out | 4.32 | 1.00 | 81.0% | ||

| Mental health | Emotional intensity | 4.24 | 1.00 | 85.5% | Mental health | Emotional intensity | 4.39 | 1.00 | 85.5% |

| Pleasure from activities | 4.19 | 1.00 | 85.5% | Pleasure from activities | 4.54 | 1.00 | 86.5% | ||

| Creativity | 4.49 | 1.00 | 76.2% | Active thinking | 4.58 | 1.00 | 86.6% | ||

| Mood affected by circadian rhythm | 4.51 | 1.00 | 89.6% | Mood affected by circadian rhythm | 4.71 | 1.00 | 90.7% | ||

| Exaggerated self-evaluation | 4.29 | 1.00 | 76.4% | Self-conceit | 4.31 | 1.00 | 86.5% | ||

| Social health | Recklessness | 4.22 | 1.00 | 72.4% | Social health | Ability to restrain | 4.63 | 1.00 | 82.4% |

| Irritability | 4.16 | 1.00 | 70.6% | Excitement | 4.30 | 1.00 | 82.4% | ||

| Socialization frequency | 4.22 | 1.00 | 82.6% | Increased socialization | 3.83 | 1.00 | 82.6% | ||

| Work efficiency | 4.36 | 1.00 | 85.5% | Work efficiency | 4.61 | 1.00 | 86.5% | ||

| Social competence | 3.95 | 1.00 | 82.6% | Interpersonal sensitivity | 4.50 | 1.00 | 86.5% | ||

| Construct | Index | Significance | Accessibility | Familiarity | Theoretical Analysis | Practical Experience | Peer Knowledge | Personal Intuition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical health | Drowsiness | 4.17 | 3.94 | 3.72 | 3.44 | 3.44 | 3.33 | 3.83 |

| Energy | 3.94 | 3.61 | 3.94 | 5.50 | 3.22 | 3.33 | 3.50 | |

| Sexual desire | 3.89 | 3.61 | 3.94 | 3.28 | 3.50 | 3.72 | 3.56 | |

| Willingness to communicate | 3.89 | 3.83 | 3.83 | 3.72 | 3.39 | 3.78 | 4.00 | |

| Concentration | 3.94 | 3.94 | 3.61 | 3.61 | 3.67 | 3.28 | 4.06 | |

| Physical discomfort | 3.72 | 3.61 | 3.83 | 3.56 | 3.78 | 3.17 | 3.83 | |

| Accelerated associations | 4.00 | 3.72 | 3.56 | 3.39 | 3.67 | 3.33 | 3.44 | |

| Flow of breath | 3.50 | 3.17 | 3.61 | 3.28 | 3.44 | 3.33 | 3.83 | |

| Amount of exercise | 3.94 | 3.83 | 3.89 | 3.56 | 3.61 | 3.61 | 4.06 | |

| Willingness to go out | 3.61 | 3.50 | 3.67 | 3.28 | 3.83 | 3.78 | 3.67 | |

| Mental health | Emotional intensity | 3.94 | 3.61 | 4.00 | 3.72 | 3.83 | 3.67 | 3.61 |

| Pleasure from activities | 4.11 | 3.61 | 4.17 | 3.61 | 3.44 | 3.50 | 3.61 | |

| Active thinking | 4.39 | 3.94 | 4.17 | 3.94 | 4.06 | 3.78 | 3.67 | |

| Mood affected by circadian rhythm | 4.17 | 3.94 | 4.06 | 4.06 | 4.06 | 3.94 | 3.83 | |

| Self-conceit | 4.28 | 4.17 | 4.06 | 3.17 | 3.50 | 3.50 | 4.00 | |

| Social health | Ability to restrain | 4.00 | 3.83 | 3.89 | 3.28 | 3.61 | 3.72 | 3.94 |

| Excitement | 3.89 | 3.67 | 3.67 | 3.67 | 3.44 | 3.67 | 3.89 | |

| Increased socialization | 3.78 | 3.94 | 3.78 | 3.39 | 3.67 | 3.72 | 4.00 | |

| Work efficiency | 4.06 | 3.83 | 3.94 | 3.33 | 4.00 | 3.83 | 4.11 | |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 3.89 | 3.67 | 3.50 | 3.44 | 3.44 | 2.89 | 3.72 |

| Construct | Index | Overall Score (100 Points) |

|---|---|---|

| Physical health | Drowsiness | 50 points |

| Energy | ||

| Sexual desire | ||

| Willingness to communicate | ||

| Concentration | ||

| Physical discomfort | ||

| Accelerated associations | ||

| Flow of breath | ||

| Amount of exercise | ||

| Willingness to go out | ||

| Mental health | Emotional intensity | 25 points |

| Pleasure from activities | ||

| Active thinking | ||

| Mood affected by circadian rhythm | ||

| Self-conceit | ||

| Social health | Ability to restrain | 25 points |

| Excitement | ||

| Increased socialization | ||

| Work efficiency | ||

| Interpersonal sensitivity |

| Frequency | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 102 | 47.4% |

| Female | 113 | 52.6% | |

| Age | Under 18 | 5 | 2.3% |

| 18 to 25 | 44 | 20.5% | |

| 26 to 30 | 65 | 30.2% | |

| 31 to 40 | 42 | 19.5% | |

| 41 to 50 | 30 | 14.0% | |

| 51 to 60 | 22 | 10.2% | |

| Over 60 | 7 | 3.3% | |

| Education | Junior high school and below | 12 | 5.6% |

| High school/technical secondary school | 18 | 8.4% | |

| Junior college | 40 | 18.6% | |

| Undergraduate degree | 84 | 39.1% | |

| Postgraduate degree or above | 61 | 28.4% |

| Coefficient a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Unstandardized coefficient | Standardized coefficient | t | Significance | Collinearity statistics | ||

| B | Standard error | Beta | Tolerance | VIF | |||

| (Constant value) | 64.373 | 4.068 | 15.825 | 0.000 | |||

| Age | 0.062 | 0.471 | 0.009 | 0.132 | 0.895 | 0.929 | 1.077 |

| Gender | 3.610 | 1.334 | 0.187 | 2.706 | 0.007 | 0.955 | 1.047 |

| Education | −0.382 | 0.596 | −0.044 | −0.641 | 0.522 | 0.954 | 1.048 |

| Construct | α Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Physical health | Pre-test | 0.766 |

| Post-test | 0.752 | |

| Mental health | Pre-test | 0.814 |

| Post-test | 0.815 | |

| Social health | Pre-test | 0.841 |

| Post-test | 0.852 | |

| Overall scale | Pre-test | 0.835 |

| Post-test | 0.786 |

| KMO Value | Pre-Test | Post-Test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.881 | 0.871 | ||

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | Chi-squared approximation | 2514.474 | 2232.539 |

| df | 190 | 190 | |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Construct | Index | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | t-Value | p-Value | ||

| Physical health | Drowsiness | 1.48 ± 0.587 | 3.09 ± 0.912 | −24.794 | <0.001 |

| Energy | 2.03 ± 0.794 | 3.24 ± 0.0745 | −14.944 | <0.001 | |

| Sexual desire | 2.54 ± 0.795 | 3.72 ± 0.753 | −16.292 | <0.001 | |

| Willingness to communicate | 2.16 ± 0.978 | 3.27 ± 0.882 | −10.524 | <0.001 | |

| Concentration | 2.20 ± 1.055 | 3.27 ± 0.918 | −9.512 | <0.001 | |

| Physical discomfort | 2.10 ± 0.739 | 3.62 ± 0.726 | −21.162 | <0.001 | |

| Accelerated associations | 1.91 ± 0.843 | 3.52 ± 0.825 | −18.526 | <0.001 | |

| Flow of breath | 2.20 ± 1.033 | 3.31 ± 0.865 | −10.011 | <0.001 | |

| Amount of exercise | 2.40 ± 1.018 | 3.47 ± 0.911 | −9.750 | <0.001 | |

| Willingness to go out | 2.39 ± 1.026 | 3.44 ± 0.904 | −9.922 | <0.001 | |

| Mental health | Emotional intensity | 2.11 ± 1.151 | 3.27 ± 0.938 | −9.564 | <0.001 |

| Pleasure from activities | 2.10 ± 1.199 | 3.28 ± 0.985 | −9.392 | <0.001 | |

| Active thinking | 2.03 ± 1.016 | 3.34 ± 0.903 | −11.721 | <0.001 | |

| Mood affected by circadian rhythm | 1.74 ± 0.782 | 3.52 ± 0.808 | −22.104 | <0.001 | |

| Self-conceit | 1.81 ± 0.787 | 3.57 ± 0.834 | −25.715 | <0.001 | |

| Social health | Ability to restrain | 1.76 ± 0.782 | 3.53 ± 0.825 | −25.893 | <0.001 |

| Excitement | 1.87 ± 0.731 | 3.49 ± 0.808 | −21.913 | <0.001 | |

| Increased socialization | 2.29 ± 0.981 | 3.38 ± 1.015 | −10.869 | <0.001 | |

| Work efficiency | 2.56 ± 1.113 | 3.65 ± 1.133 | −9.162 | <0.001 | |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 2.28 ± 1.003 | 3.69 ± 1.055 | −12.707 | <0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shen, W.; Chen, S.; Law, R.; Wang, X.; Zuo, Y.; Zhang, M. Development and Initial Validation of Healing and Therapeutic Design Indices and Scale for Measuring Health of Sub-Healthy Tourist Populations in Hot Spring Tourism. Buildings 2025, 15, 2837. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15162837

Shen W, Chen S, Law R, Wang X, Zuo Y, Zhang M. Development and Initial Validation of Healing and Therapeutic Design Indices and Scale for Measuring Health of Sub-Healthy Tourist Populations in Hot Spring Tourism. Buildings. 2025; 15(16):2837. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15162837

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Wencan, Sirong Chen, Rob Law, Xiaoyu Wang, Yifan Zuo, and Mu Zhang. 2025. "Development and Initial Validation of Healing and Therapeutic Design Indices and Scale for Measuring Health of Sub-Healthy Tourist Populations in Hot Spring Tourism" Buildings 15, no. 16: 2837. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15162837

APA StyleShen, W., Chen, S., Law, R., Wang, X., Zuo, Y., & Zhang, M. (2025). Development and Initial Validation of Healing and Therapeutic Design Indices and Scale for Measuring Health of Sub-Healthy Tourist Populations in Hot Spring Tourism. Buildings, 15(16), 2837. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15162837