A Space for the Elderly: Inclusion Through Design

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Jordan in Context: The Reality of Aging

2.2. What Makes an Elderly-Friendly Space

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Delphi Technique

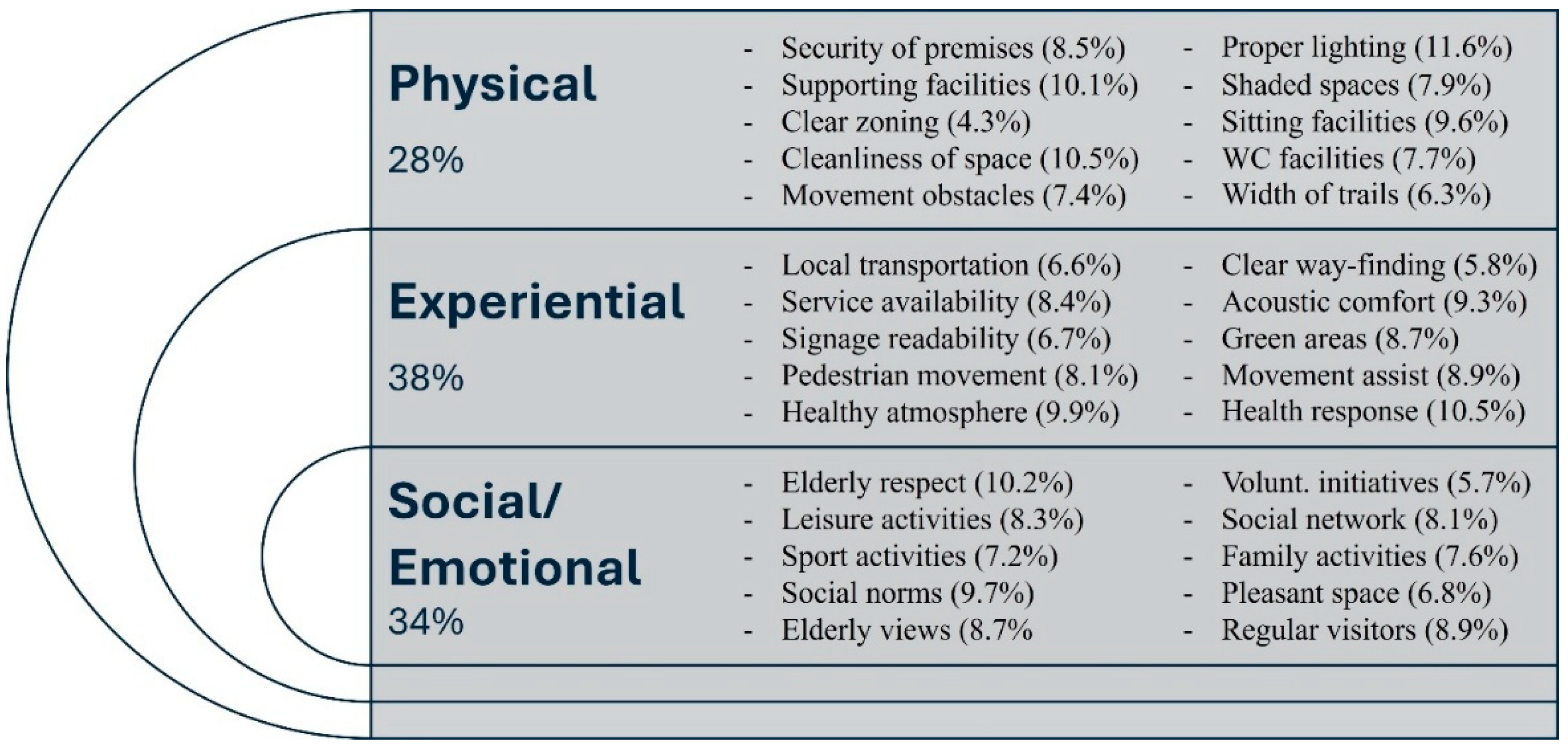

- Physical aspects: Indicators relevant to the physical appearance of the park and the main features it offered to facilitate use by the elderly in the public space. This included indicators that focused on space structure, safety and security, and physical features that offered assistance to elderly users.

- Experiential aspects: Induced feelings delivered to the elderly users in the space, driven by their experience of it. These included aspects of ease and reachability, the induction and facilitation of healthy behaviors and habits, and alignment with the key values and cultural tendencies of the elderly segment.

- Social/emotional aspects: Specificity of the communal surroundings of the elderly community. This includes contextual/social aspects that relate to their wellbeing and emotional care and indicators most relevant to strengthening the position of the elderly within the community, the facilitation of social connectedness and care, and supporting continuous engagement and a sense of belonging to their local community.

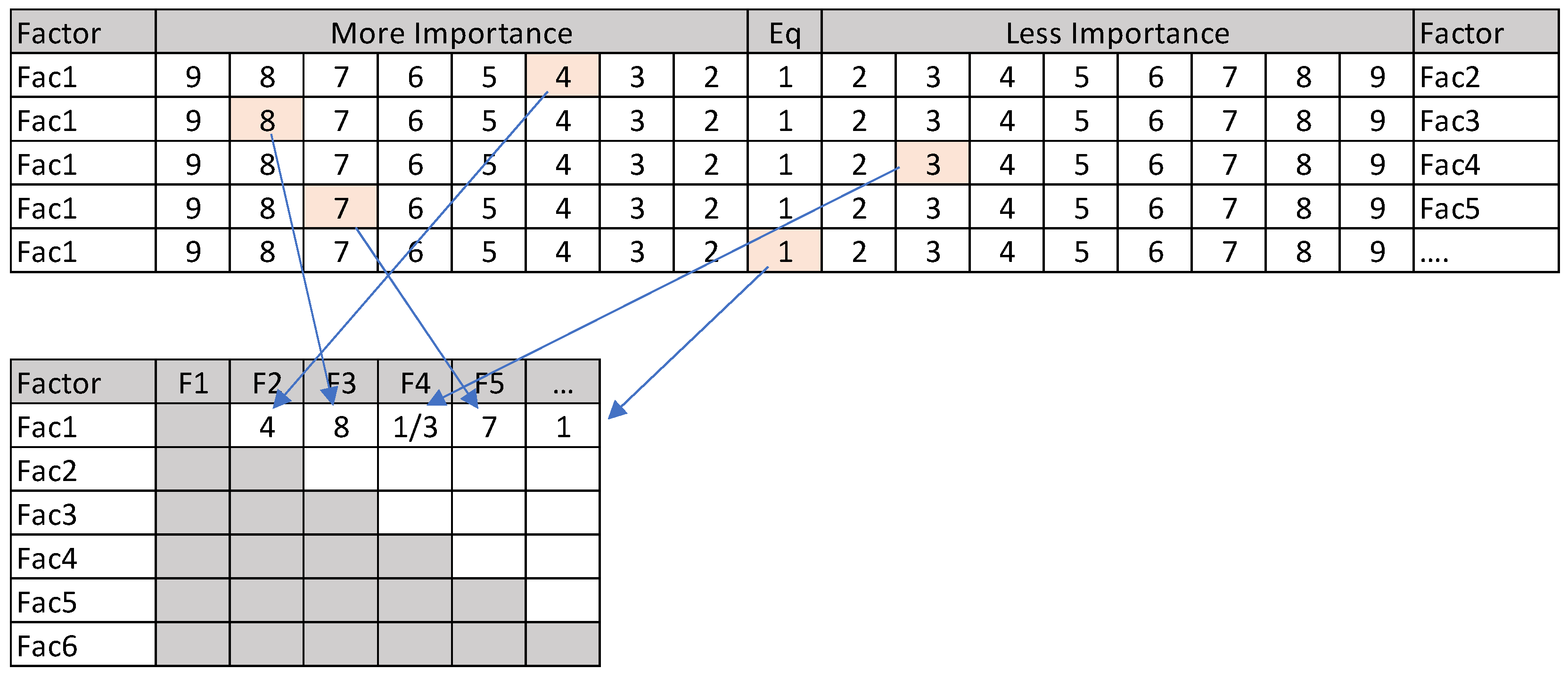

3.2. Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)

- CI: the level of consistency

- λmax: the maximum eigenvalue of the matrix

- RCI: a random consistency index taken according to the number of factors

4. Results

4.1. Categorical Findings

4.2. AHP Findings—Indicators

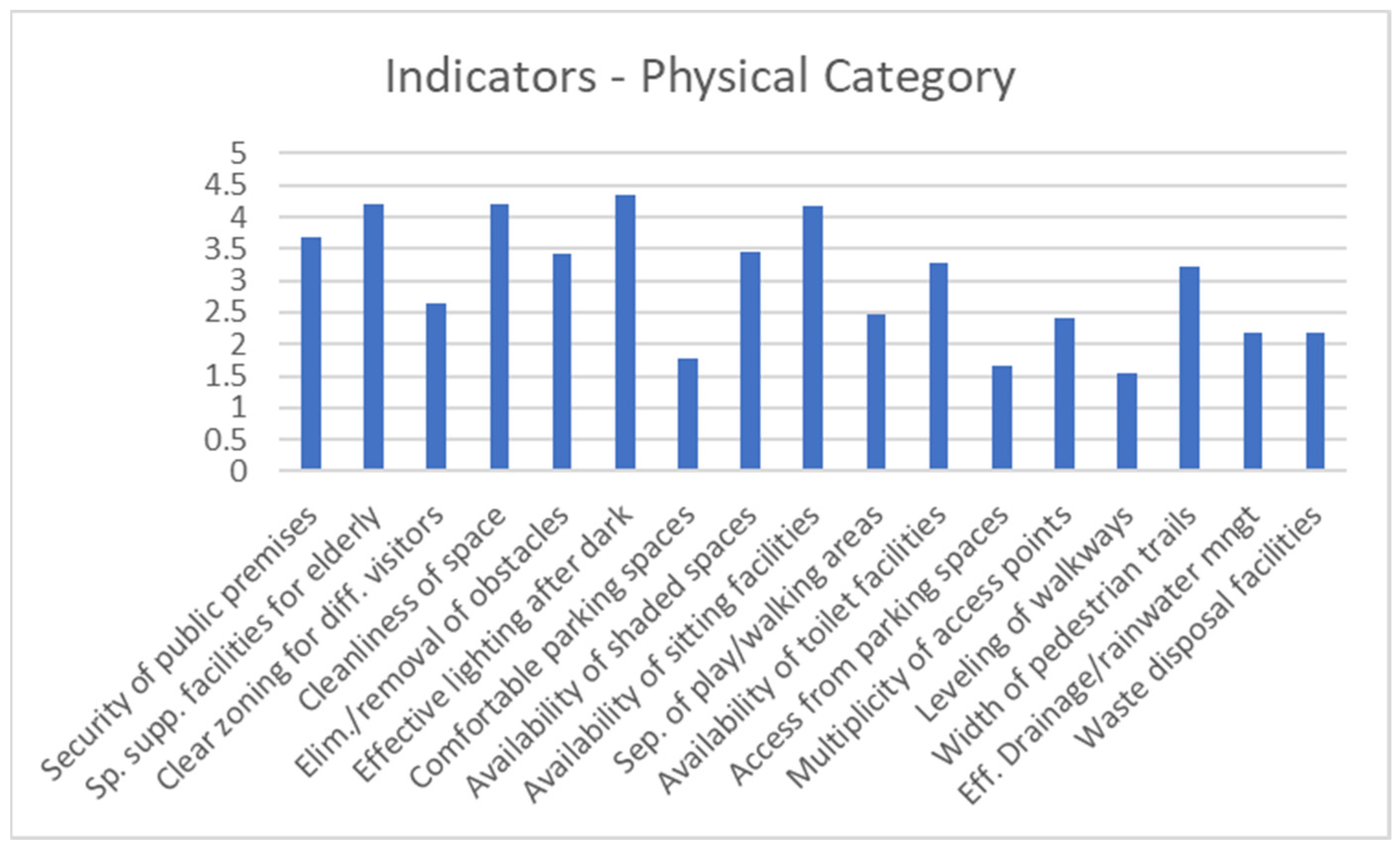

4.3. Physical Category Indicators

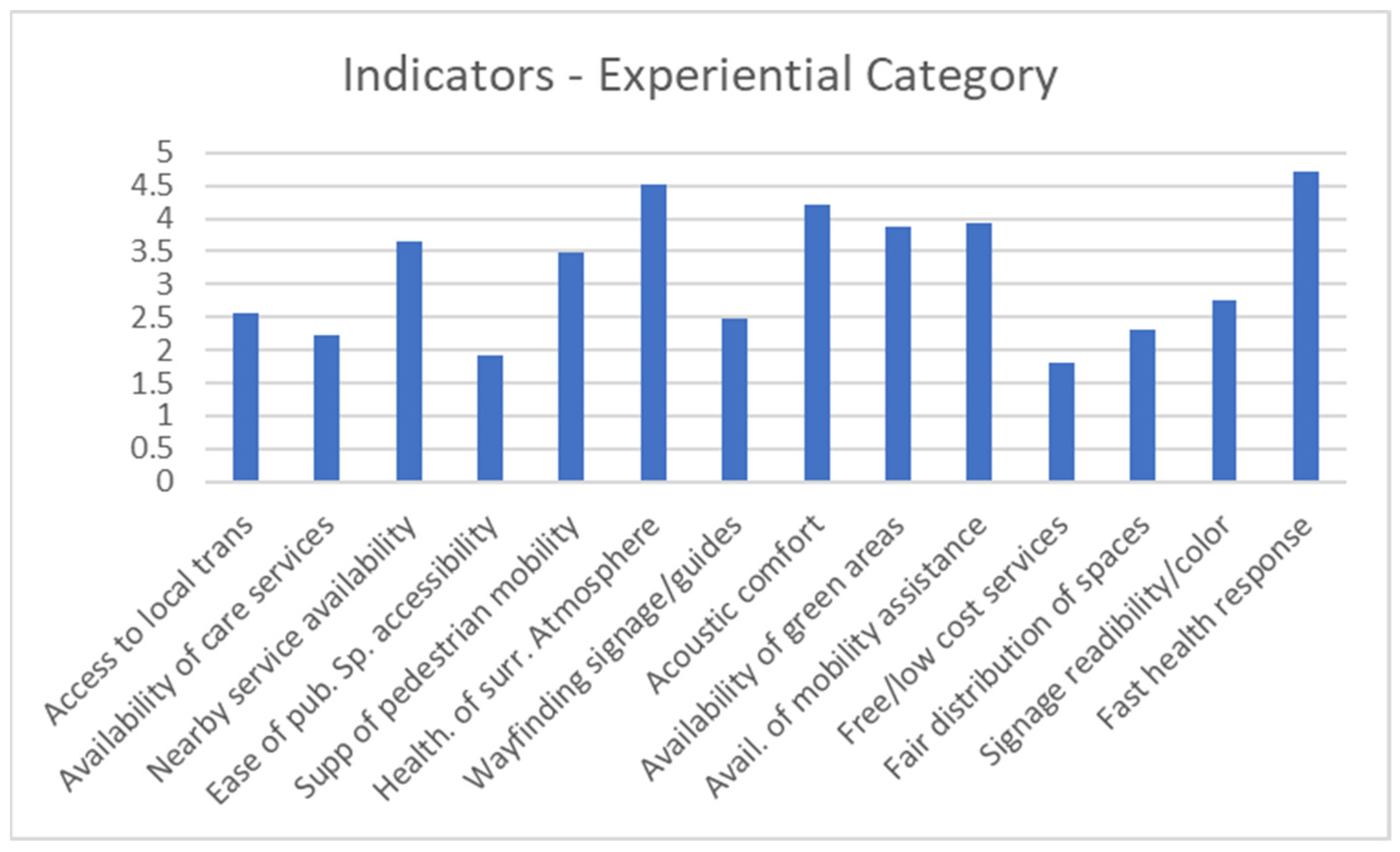

4.4. Experiential Category Indicators

4.5. Social/Emotional Category Indicators

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kalinkara, V. Basic Gerontology: The Science of Aging; Nobel: Ankara, Turkey, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, R.B. The history and place of age-based public policy. Generations 1995, 14, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dury, S.; Willems, J.; De Witt, N.; De Donder, L.; Buffel, T.; Verte, D. Municipality and neighborhood influences on volunteering in later life. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2016, 35, 601–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pynoos, J. Strategies for home modification and repair. In Aging in Place; Callahan, J., Ed.; Baywood: Amityville, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide. 2007. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241547307 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- World Health Organization. National Programmes for Age-Friendly Cities and Communities: A Guide. 2023. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/366634/9789240068698-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Yang, J.J.; Kim, G.T.; Lee, T.J. Parks as leisure spaces for older adults’ daily wellness: A Korean case study. Ann. Leis. Res. 2012, 15, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffel, T.; Phillipson, C.; Scharf, T. Ageing in urban environments: Developing ‘age-friendly’ cities. Crit. Soc. Policy 2012, 32, 597–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansmann, R.; Hug, S.; Seeland, K. Restoration and stress relief through physical activities in forests and parks. Urban For. Urban Green. 2007, 6, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, R. Local environments and older people’s health: Dimensions from a comparative qualitative study in Scotland. Health Place 2008, 14, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takano, T.; Nakamura, K.; Watanabe, M. Urban residential environments and senior citizens’ longevity in megacity areas: The importance of walkable green spaces. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2002, 56, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A.; Levy-Storms, L.; Brozen, M. Placemaking for an Aging Population: Guidelines for Senior-Friendly Parks. In UCLA Complete Streets Initiative; Luskin School of Public Affairs; Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Abyad, A. Ageing in the Middle East and North Africa: Demographic and health trends. Int. J. Ageing Dev. Ctries. 2021, 6, 112–128. [Google Scholar]

- Sibai, A.M.; Semaan, A.; Tabbara, J.; Rizk, A. Ageing and health in the Arab region: Challenges, opportunities and the way forward. Popul. Horiz. 2017, 14, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFPA. Country Profile: The Rights and Wellbeing of Older Persons in Jordan. 2009. Available online: https://arabstates.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/country_profile_-_jordan_10-1-2024.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- DOS. Statistical Yearbook of Jordan, 2024; Department of Statistics: Amman, Jordan, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Awad, A. The Social Protection System. 2017. Phoenix Center for Economic and Informatics Studies: Jordan. Available online: https://www.annd.org/data/item/cd/aw2014/pdf/english/three1.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- NCFA. The Analysis Report of the Evaluation of the Jordanian National Strategy for Senior Citizens (2009–2013); National Council for Family Affairs (NCFA): Amman, Jordan, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- National Council for Family Affairs and ESCWA. Jordan’s National Strategy for the Elderly; NCFA; ESCWA: Amman, Jordan, 2024; Available online: http://www.unescwa.org/sites/default/files/pubs/pdf/jordanian-national-strategy-older-persons-2025-2030-arabic.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C.; Neis, H.; Anninou, A.; King, I. A New Theory of Urban Design; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Speck, J. Walkable City: How Downtown Can Save America, One Step at a Time; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mathew Greenwald and Associates. These Four Walls: Americans 45 + Talk About Home and Community; AARP: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; Available online: https://www.aarp.org/pri/topics/livable-communities/housing/four_walls/ (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Sheikhazami, A.; Aliakbari, S. Evaluating sustainable neighborhood development for the elderly with emphasis on physical and social sustainability: Case study: Neighborhoods in district 8 of Tehran. Space Ontol. Int. J. 2020, 9, 63–78. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Soltip, M.; Ramadhani, A.; Luru, M. Alternative locations of older people-friendly city park in Bandung City, Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium on Sustainable Urban Development, Jakarta, Indonesia, 2–3 August 2023; IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. IOP: Bristol, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, X.; Sedini, C.; Zurlo, F. Building an age-friendly city for elderly citizens through co-designing an urban walkable scenario. In Proceedings of the Academy of Design Innovation Management Conference Proceedings, London, UK, 19–21 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, P.H.; Oberlink, M.R. The Advantage Initiative: Developing community indicators to promote the health and well-being of older people. Fam. Community Health 2003, 26, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lak, A.; Aghamolaei, R.; Baradaran, H.; Myint, P. A Framework for Elder-Friendly Public Open Spaces from the Iranian Older Adults’ perspectives: A Mixed-Method Study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 56, 126857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, Z.; Bowling, A. Quality of life from the perspectives of older people. Ageing Soc. 2004, 24, 675–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.; Shea, E.O.; Cooney, A. Quality of life for older people living in long-stay settings in Ireland. J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 16, 2167–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robleda, S.; Pachana, N. Quality of life in Australian adults aged 50 years and over: Data using the schedule for the evaluation of individual quality of life. Clin. Gerontol. 2019, 42, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarkson, P.J.; Coleman, R.; Keates, S.; Lebbon, C. Inclusive Design: Design for the Whole Population; Springer Science and Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Verganti, R. Design Driven Innovation: Changing the Rules of Competition by Radically Innovating What Things Mean; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Orsega-Smith, E.; Mowen, A.J.; Payne, L.; Godbey, G. The interaction of stress and park use on psycho-physiological health in older adults. J. Leis. Res. 2004, 36, 232–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libovich, A. Assessing Green Buildings for Sustainable Cities. In Proceedings of the 2005 World Sustainable Building Conference, Tokyo, Japan, 27–29 September 2005; pp. 1968–1971. [Google Scholar]

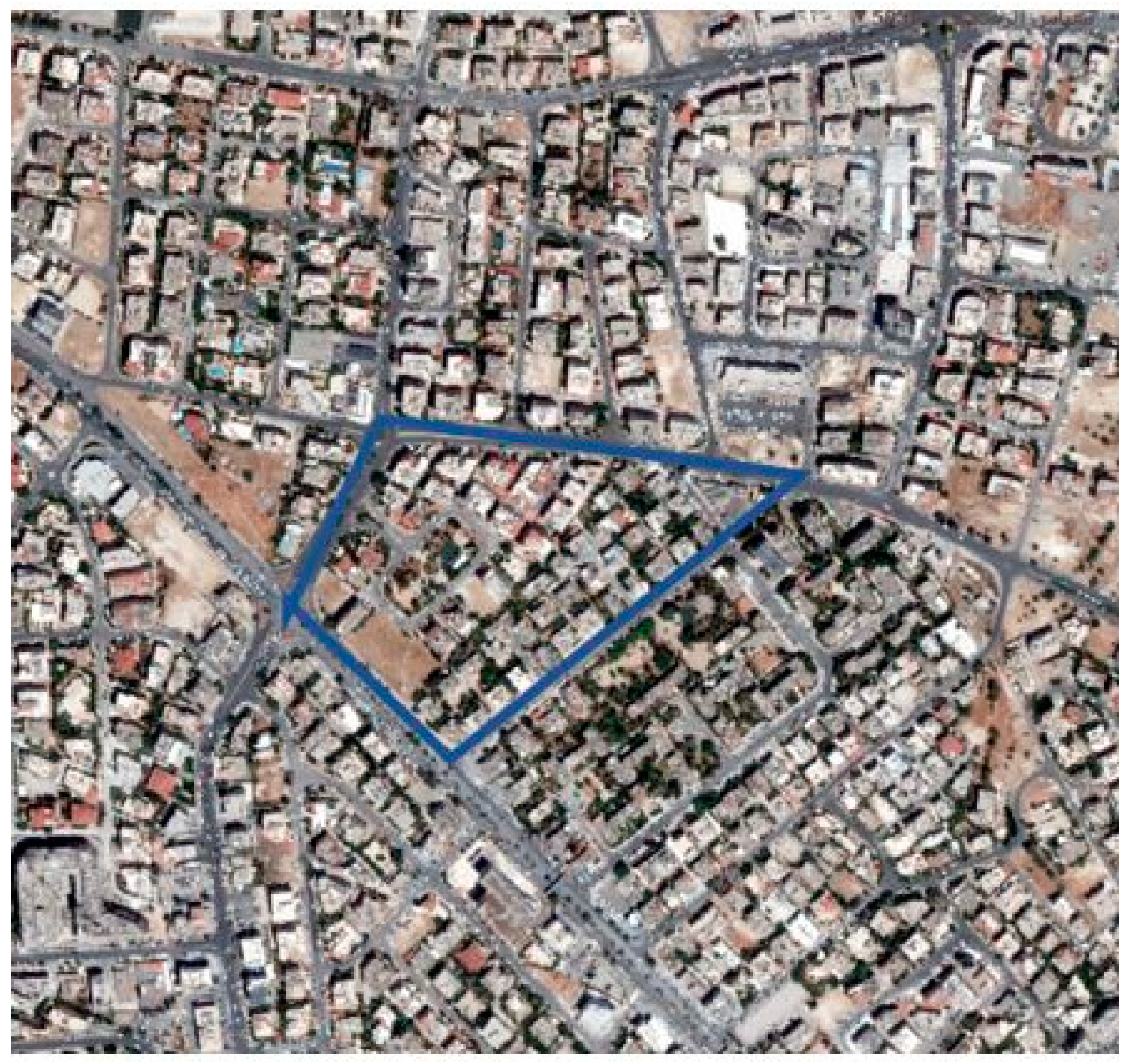

- Alshamaelh, A. Al Hussein Suburb: First Housing Complex in the Kingdom. 2014. Available online: https://alizakishamaelh.wordpress.com/2014/12/24/ضاحية-الحسين-أول-إسكان-في-المملكة (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- CSBE. Green Pocket in Dahiyat Al-Hussein. 2019. Available online: http://www.csbe.org/green-pocket-in-dahiyat-al-hussein (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Sharif, A.A. User activities and the heterogeneity of urban space: The case of Dahiyat Al Hussein park. Front. Archit. Res. 2020, 9, 837–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, R. A Framework for the Sustainability Assessment of Urban Design and Development in Iraqi Cities. Ph.D. Thesis, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bragança, L.; Koukkari, H.; Mateus, R. Building sustainability assessment. Sustainability 2010, 2, 2010–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdova, E.; Vilcekovaa, S. Sustainable building assessment tool in Slovakia. Energy Procedia 2015, 78, 1829–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.; Lee, G. Critical factors for improving social sustainability of urban renewal projects. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 85, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoli, C.; Pawlowski, S. The Delphi method as a research tool: An example, design considerations and applications. Inf. Manag. 2004, 42, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T. How to make a decision: The Analytic Hierarchy Process. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1990, 48, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Al Nsairat, S. Developing a green building assessment tool for developing countries: Case of Jordan. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 1053–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # | Indicator | Sheikhazami & Aliakbari [24] | MG&A [23] | Soltip et al. [25] | Speck [22] | Loukaitou-Sideris et al. [12] | WHO [5] | Pei et al. [26] | Feldman & Oberlink [27] | Lak et al. [28] | Gabriel and Bowling [29] | Murphy et al. [30] | Robleda & Pachana [31] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Access to local transportation | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| 2 | Availability of surrounding care services | x | x | x | |||||||||

| 3 | Nearby service availability | x | x | x | |||||||||

| 4 | Security of public premises | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| 5 | Respect towards the elderly | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| 6 | Eased accessibility to public spaces | x | x | x | |||||||||

| 7 | Elderly-focused urban policies | x | x | x | |||||||||

| 8 | Special support facilities for the elderly | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| 9 | Support for pedestrian mobility | x | x | ||||||||||

| 10 | Elderly-friendly leisure activities | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| 11 | Healthiness of surrounding atmosphere | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| 12 | Clear way-finding signage and guides | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| 13 | Clear zoning for visitor segments | x | x | x | |||||||||

| 14 | Sporting activities for the elderly | x | x | x | |||||||||

| 15 | Acoustic comfort/verbal interaction | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| 16 | Connectedness to traditions/social norms | x | x | x | |||||||||

| 17 | Access to groceries and food retail stores | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| 18 | Availability of green areas | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| 19 | Periodic public events and activities | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| 20 | Consideration of elderly’s views on space | x | x | ||||||||||

| 21 | Social and voluntary initiatives at site | x | x | x | |||||||||

| 22 | Cleanliness of space | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| 23 | Reduction of obstacles to mobility | x | x | x | |||||||||

| 24 | Mobility assistance (rails, ramps, etc.) | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| 25 | Effective lighting after dark | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

| 26 | Comfortable parking spaces | x | x | ||||||||||

| 27 | Enablement of social networks | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| 28 | Options for family activities | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| 29 | Availability of shaded spaces | x | x | x | |||||||||

| 30 | Low-cost services/facilities | x | x | x | |||||||||

| 31 | Sitting facilities (benches, seats, etc.) | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| 32 | Separation of play/walking areas | x | x | ||||||||||

| 33 | Availability of toilet facilities | x | x | ||||||||||

| 34 | Spaces/different segment requirements | x | |||||||||||

| 35 | Readability/color-friendliness of signage | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| 36 | Fast-health-response/facilities | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| 37 | Ease of access from parking spaces | x | x | ||||||||||

| 38 | Pleasant appearance of space | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| 39 | Multiplicity of access points | x | |||||||||||

| 40 | Levelling of pedestrian walkways | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| 41 | Avoidance of excessive stairs/slopes | x | x | ||||||||||

| 42 | Walking assistance (canes, wheelchairs) | x | x | ||||||||||

| 43 | Width of pedestrian trails | x | x | x | x | ||||||||

| 44 | Familiarity of regular visitors | x | x | ||||||||||

| 45 | Limitation of vandalism | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||

| 46 | Limitation of crowdedness | x | x | ||||||||||

| 47 | Draining and rainwater management | x | |||||||||||

| 48 | Waste disposal facilities | x | x | x | |||||||||

| 49 | Enclosure within surrounding buildings | x | x | x |

| Experts: Sample Distribution | |||

| Gender | Male | Female | |

| 51.8% | 49.2% | ||

| Background | Academia | Professional | Government |

| 40.0% | 27.9% | 32.1% | |

| Education level | Graduate | Postgraduate | |

| 47.7% | 52.3% | ||

| Users: Sample Distribution | |||

| Gender | Male | Female | |

| 46.8% | 53.2% | ||

| Years (Y) in the neighborhood | Below 5 Years | 5–10 Years | Above 10 Years |

| 26.3% | 39.1% | 34.6% | |

| Education level | Secondary | Graduate | Postgraduate |

| 22.9% | 61.5% | 15.6% | |

| # | Indicator | Rating ± SD | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Security of public premises | 3.67 ± 0.61 | 8.5% |

| 2 | Special supporting facilities for the elderly | 4.19 ± 0.82 | 10.1% |

| 3 | Clear zoning for different visitor segments | 2.63 ± 0.46 | 4.3% |

| 4 | Cleanliness of space | 4.21 ± 0.56 | 10.5% |

| 5 | Elimination/reduction of obstacles to mobility | 3.41 ± 0.71 | 7.4% |

| 6 | Effective lighting after dark | 4.35 ± 0.62 | 11.6% |

| 7 | Availability of comfortable parking spaces | 1.78 ± 0.49 | 1.4% |

| 8 | Availability of shaded spaces | 3.44 ± 0.60 | 7.9% |

| 9 | Availability of sitting facilities (benches, seats, etc.) | 4.16 ± 0.78 | 9.6% |

| 10 | Separation of play areas from walking/sitting areas | 2.47 ± 0.53 | 3.2% |

| 11 | Availability of toilet facilities | 3.29 ± 0.66 | 7.7% |

| 12 | Ease of access from parking spaces | 1.65 ± 0.72 | 2.3% |

| 13 | Multiplicity of access points | 2.41 ± 0.81 | 2.7% |

| 14 | Leveling of pedestrian walkways | 1.55 ± 0.64 | 1.7% |

| 15 | Width of pedestrian trails | 3.22 ± 0.63 | 6.3% |

| 16 | Effective drainage and rainwater management | 2.17 ± 0.84 | 2.6% |

| 17 | Availability of waste disposal facilities | 2.19 ± 0.92 | 2.2% |

| # | Indicator | Rating ± SD | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Access to local transportation | 2.57 ± 0.51 | 6.6% |

| 2 | Availability of surrounding care services | 2.23 ± 0.66 | 2.1% |

| 3 | Availability of nearby services | 3.65 ± 0.45 | 8.4% |

| 4 | Ease of accessibility to public spaces | 1.92 ± 0.63 | 5.2% |

| 5 | Support for pedestrian mobility | 3.49 ± 0.58 | 8.1% |

| 6 | Healthiness of surrounding atmosphere | 4.52 ± 0.53 | 9.9% |

| 7 | Clear wayfinding signage and guides | 2.47 ± 0.78 | 5.8% |

| 8 | Acoustic comfort to allow verbal interaction | 4.21 ± 0.61 | 9.3% |

| 9 | Availability of green areas | 3.89 ± 0.49 | 8.7% |

| 10 | Availability of mobility assistance (rails, ramps, etc) | 3.93 ± 0.94 | 8.9% |

| 11 | Availability of free/low-cost services/facilities | 1.81 ± 0.65 | 4.4% |

| 12 | Fair distribution of spaces for segment requirements | 2.32 ± 0.77 | 5.4% |

| 13 | Readability/color-friendliness of signage | 2.77 ± 0.59 | 6.7% |

| 14 | Availability of fast-health-response/facilities | 4.73 ± 0.46 | 10.5% |

| # | Indicator | Rating ± SD | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Respect towards the elderly | 4.45 ± 0.74 | 10.2% |

| 2 | Elderly-focused urban policies and initiatives | 2.38 ± 0.91 | 5.2% |

| 3 | Availability of elderly-friendly leisure activities | 3.78 ± 0.96 | 8.3% |

| 4 | Provision of sporting activities for the elderly | 3.16 ± 0.53 | 7.2% |

| 5 | Connectedness to traditions and social norms | 4.23 ± 0.87 | 9.7% |

| 6 | Periodic public events and activities | 2.21 ± 0.67 | 4.1% |

| 7 | Consideration of the elderly’s views in space development | 4.06 ± 0.53 | 8.7% |

| 8 | Social and voluntary initiatives at site | 2.71 ± 0.69 | 5.7% |

| 9 | Enablement of social network development | 3.56 ± 1.21 | 8.1% |

| 10 | Enablement of multiple options for family activities | 3.32 ± 0.62 | 7.6% |

| 11 | Limitation of vandalism/abuse of facilities | 2.56 ± 0.75 | 5.5% |

| 12 | Limitation of crowdedness | 1.45 ± 0.62 | 2.1% |

| 13 | Enclosure within surrounding buildings | 1.22 ± 0.46 | 1.9% |

| 14 | Intimacy and pleasant appearance of space | 3.09 ± 0.59 | 6.8% |

| 15 | Consistency and familiarity of regular visitors | 4.19 ± 0.72 | 8.9% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharif, A.A. A Space for the Elderly: Inclusion Through Design. Buildings 2025, 15, 2596. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15152596

Sharif AA. A Space for the Elderly: Inclusion Through Design. Buildings. 2025; 15(15):2596. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15152596

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharif, Ahlam Ammar. 2025. "A Space for the Elderly: Inclusion Through Design" Buildings 15, no. 15: 2596. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15152596

APA StyleSharif, A. A. (2025). A Space for the Elderly: Inclusion Through Design. Buildings, 15(15), 2596. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15152596