1. Introduction

Wildfire events, also known as bushfires in Australia, have demonstrated increasing prevalence globally during the past century. This trend correlates with rising global temperatures attributed to anthropogenic climate change [

1]. The international impact of these events spans North America, Europe, and the Mediterranean regions [

2], but are especially common in Australia due to the endemic vegetation types and climatic conditions [

3]. The global economic damage from wildfire events in the last century has reached over USD 120 billion [

2,

4]. The impact of wildfire disaster events extends to communities, building infrastructure, wildlife habitats, and ecological systems. In Australia, the catastrophic 2019–2020 Black Summer bushfires alone destroyed 3100 homes, claimed 33 lives, generated AUD 1.9 billion in insurance claims, and damaged over 24 million hectares of bushland [

5].

Despite the ongoing risk of bushfires, a significant portion of the Australian demographic remains living in bushfire-prone regions, motivated by desires for natural surroundings, coastal proximity, and housing affordability considerations [

6]. Further demographic analysis of Australia reveals an ageing population trend, with the indication that there are a higher proportion of older people, classified in this study as 65+ years, living in regional and semi-urban regions that are more bushfire-prone [

7].

Older people are a particularly vulnerable demographic, more likely to be challenged with additional financial, physical, and social vulnerabilities that may limit their level of preparedness and resilience during bushfires [

8]. Due to these vulnerabilities, older people are one of the most impacted demographics during climate-related disasters [

9,

10], with a higher fatality rate during bushfires [

11]. These vulnerabilities are further compounded by housing conditions that were not designed for climate resilience nor with the specific capabilities of older people in mind [

12]. Despite these factors, the bushfire retrofit guidance currently available in Australia is not specifically developed with older people in mind. Therefore, the aims and objectives of this study were to bridge the critical gap between current bushfire retrofit knowledge with a more nuanced understanding of older people’s perceptions and capabilities.

The adapted bushfire retrofit toolkit in this study was developed through a qualitative multi-method approach with a systematic literature review (SLR) of existing bushfire-related literature and a participatory design within two bushfire-prone case study regions (Bega Valley Shire, NSW, and Noosa Shire, QLD). The development of an Adapted Toolkit Design was followed by testing and validation with end-users and experts. The research specifically examined how retrofit guidance can be effectively designed and communicated to maximise implementation by older people with diverse capabilities. The resulting adapted toolkit aims to provide an innovative design framework that inclusively addresses the intersection of ageing and climate adaptation, building resilience for bushfire communities.

2. Background

Australia employs the Bushfire Attack Level (BAL) metric as the national standard for assessing a building’s vulnerability to bushfires. This system, defined in Australian Standard (AS) 3959-2018, establishes six risk categories from BAL-LOW to BAL-FZ (Flame Zone), each requiring specific construction standards responding to the level of bushfire risk and bushfire-prone conditions [

13]. A ‘bushfire-prone’ area in Australia is defined under AS 3959-2018 based on the following four key factors: the regional Fire Danger Index (FDI), classified vegetation types, distance from hazardous vegetation, and topographical slope [

13]. These factors determine the potential for bushfire ignition, spread, and intensity, with hazardous vegetation acting as a fuel that can sustain and accelerate fire propagation once ignition occurs.

A report conducted in 2020 by the Australian Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements, prompted by the 2019–2020 bushfire season, revealed that approximately 90% of structures in bushfire-prone regions fail to meet current bushfire construction regulations [

14]. This widespread non-compliance stems primarily from the fact that these dwellings were built before the implementation and enforcement of Bushfire Attack Level (BAL) construction standards, which were first introduced in 2009.

The devastating impact of the 2019–2020 Black Summer bushfires in Australia highlighted the severe risk of housing non-compliance against the BAL metric, with 74% of destroyed homes not meeting current standards [

12]. In response to this catastrophic event, State governments, local authorities, and industry organisations, respectively, initiated comprehensive programmes promoting new design guidelines and retrofit resources for bushfire resilience. These Australia-wide initiatives specifically target the building compliance gap, aiming to enhance the bushfire resilience of Australia’s existing housing stock.

The majority of bushfire risk communication in Australia is distributed regionally rather than nationally or globally. This is due to the fact that the information needs to address specific climatic conditions, landscapes, and urban environments unique to each region in order to resonate with specific bushfire-affected communities [

15].

Disaster preparation information is traditionally communicated via websites, printed brochures and posters, public service announcements via radio and television, and community outreach [

16]. These communication tools typically focus on distributing standardised content intended to increase public knowledge and offer broad recommendations for disaster readiness. Despite having broad reach, these approaches rely on passive information consumption and do not necessarily increase disaster preparedness due to the lack of active community participation [

16,

17].

In response to the limitations of traditional communication tools, the past decade has seen an emergence of advanced communication technologies as promising alternatives for disaster preparedness education. Virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and gamification approaches have gained significant traction for their capacity to transform passive information consumption into dynamic, experiential learning opportunities that more effectively engage diverse community members [

18,

19,

20].

These immersive communication tools have been specifically applied across various natural disasters, including earthquake simulations [

21], flood scenarios [

22], and bushfire preparedness [

23]. These tools can enhance community education on disaster risk preparation and reduction, extending to specialised evacuation training protocols that prepare communities for coordinated responses during actual disaster events [

24]. The ability of these tools to simulate real-world bushfire scenarios allows users to interact with and prepare for risks in safe environments.

Despite the wide range of available traditional and advanced communication tools, these approaches need to be evaluated against their appropriateness and usability when engaging with older demographics in disaster-prone regions. According to the ‘Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030’, published by the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), specific demographic groups—including older people, persons with disabilities, and women—experience disproportionate vulnerability and adverse impacts during disaster events [

25]. The Council of Australia further stipulates that “Vulnerable individuals [should] have equitable access to appropriate information, training and opportunities,” in the context of disaster risk communication [

26] (p. 8).

Although older people present certain vulnerabilities, it is also important to recognise their active participation and social contribution within their communities, especially through their knowledge-sharing capabilities [

27]. Therefore, communication tools should be developed in consultation with the lived experience and knowledge of older people to empower them to have a voice and visibility in their communities as well as in disaster planning policies [

28]. This approach requires addressing the complex intersection of age-specific considerations, including chronic health conditions, cognitive processing changes, mobility limitations, socioeconomic constraints, resource access, and digital literacy barriers [

29]. Each factor significantly impacts how older people access, understand, and implement critical bushfire preparedness information.

From reviewing the current available guidance on bushfire resilience, this study presents an evidently significant gap in not addressing the liveability needs and capabilities of Australians ageing in bushfire-prone regions. While there is guidance on designing liveable homes for older people, “there is little integration between such guidelines and strategies required for climate change mitigation or adaptation.” [

30] (p. 74). The absence of this integration represents an oversight in current bushfire resilience approaches as they fail to account for the specific challenges faced by older people when implementing and maintaining bushfire retrofit measures.

To address these gaps, this study presents a novel integrated approach that positions older Australians not merely as recipients of disaster information but as active participants in the development of tailored retrofit solutions for bushfire resilience. By synthesising technical bushfire building requirements with ageing-in-place design principles and appropriate communication methods, the adapted toolkit from this study aims to fill a critical gap in disaster resilience knowledge.

3. Materials and Methods

The research design objectives aimed to encompass the intersection of bushfire resilience guidance, bushfire construction standards, and communication tools, with the perceptions of older people in bushfire-prone regions. Engaging multiple stakeholders and communities through participatory research methods provides an understanding of subjective experiences and implementation barriers that affect climate-resilient decision-making processes [

31]. This collaborative approach can reveal critical insights into the personal, social, and practical considerations that might otherwise remain undetected through top-down research methods. This study therefore employed a qualitative multi-method approach.

The following two distinct bushfire-prone regions in Australia were selected as the case study contexts for this study: 1. Bega Valley Local Government Area (LGA) in New South Wales; 2. Noosa Shire LGA in Queensland. These regions were primarily chosen based on existing research partnerships with local authorities that could facilitate access to community networks. The two case study contexts have documented histories of severe bushfire exposure, having experienced significant impact from major bushfire events during the past decade, including the 2019–2020 Black Summer bushfires. The demographic profiles of the case study contexts are also consistent with Australia’s ageing population projections [

32,

33] relevant to this study’s requirements.

The qualitative approach to developing the Adapted Toolkit Design incorporated key phases of 1. Systematic Literature Review (SLR); 2. Participatory Design. The SLR findings informed the development of data collection methods and analytical frameworks adopted in the Participatory Design. The participatory design methods adopted in this study primarily involved focus groups in Bega Valley and Noosa Shire, respectively, followed by the establishment of case study participants from each region. The qualitative data collected from these methods aimed to capture the lived experiences and practical needs of older people in two case study regions to form the content and communication aspects of the Adapted Toolkit Design.

Following the initial Adapted Toolkit Design, a testing and validation phase was implemented, establishing engagement with industry experts and end-users to ensure accessibility, relevance, and community implementation. This comprehensive research design allowed the thorough development, testing, and validation of adapted bushfire retrofit guidance to meet the study objectives (see

Figure 1).

3.1. Systematic Literature Review

The SLR established the evidence base for developing an age-appropriate bushfire retrofit toolkit through the interdisciplinary integration of building design, gerontological, and disaster resilience research. The review systematically examined existing bushfire resilience resources and academic knowledge to identify both available guidance and critical gaps in addressing older people’s specific vulnerability and capacity factors.

3.1.1. Search Strategy and Criteria

A structured search protocol was developed targeting peer-reviewed academic literature and authoritative grey literature published between 2010 and 2024. This timeframe encompasses the period of significant developments in Australian policy following major bushfire fire events as well as recent international wildfire events.

Boolean operators (AND/OR) were employed to combine predetermined search terms into systematic search strings. Core terms included “bushfires”, “bushfire resilience”, “housing design”, “vulnerable communities”, “ageing resilience”. The following two-term search strings were constructed to capture literature at the intersection of bushfire resilience and older people’s resilience: “vulnerable communities” AND “bushfires” OR “bushfire resilience”; “bushfires” OR “ageing resilience” AND “housing design”.

Inclusion and exclusion strategies were further implemented to ensure comprehensive coverage of the intersecting themes relevant to the study objectives while maintaining focus on evidence-based research directly applicable to bushfire resilience for older people.

Inclusion Criteria: Sources were included based on their relevance to the following three key domains that form the conceptual framework of this study:

Bushfire housing design and compliance.

Resilience for older people.

Communication strategies for community education and engagement.

Exclusion Criteria: Sources were excluded if they

Did not specifically address bushfire, wildfire, or climate resilience.

Did not address the built environment.

Consisted primarily of opinion pieces, editorials, or commentaries without rigorous methodological approaches or data.

The filtering process involved the initial screening of titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria, followed by a full-text review of potentially relevant sources. Borderline cases were discussed among the research team to ensure consistency in the application of criteria. The systematic approach ensured that the final literature corpus remained directly focused on evidence-based approaches that could inform the development of age-appropriate bushfire resilience guidance, while excluding tangential or methodologically weak sources that might dilute the quality of insights generated.

3.1.2. Data Sources and Screening

Systematic searches were conducted across three databases, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, selected for their interdisciplinary coverage of architecture, gerontology, and disaster management research. Grey literature was identified through targeted searches of government websites, policy databases, and government-funded organisation publications.

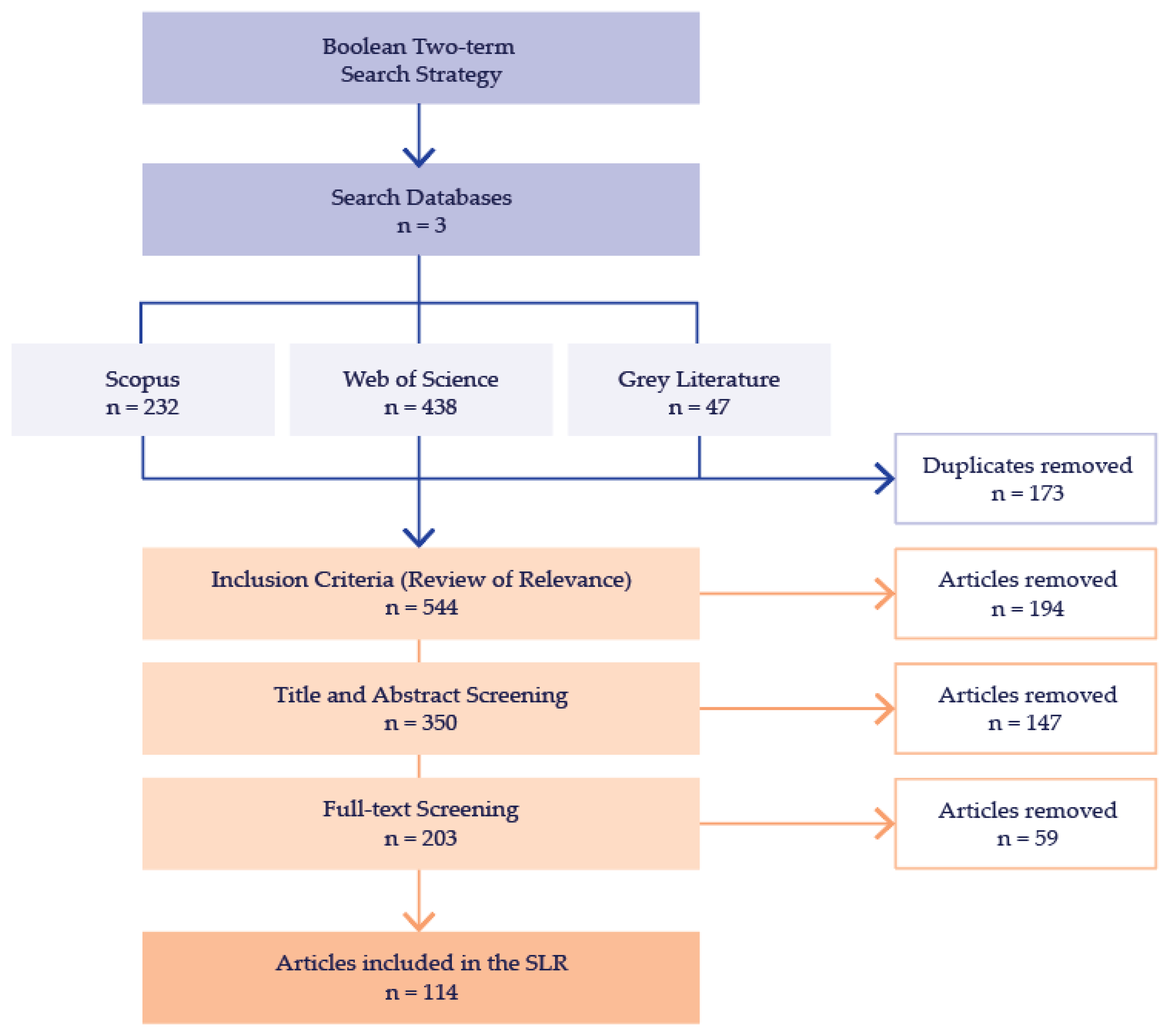

The SLR produced the following search results:

Whilst Google Scholar was initially included in the search strategy, the platform returned over 10,000 results with significant quality variation and extensive duplication across sources. To maintain methodological rigour and ensure consistent quality standards, the search strategy focused on established academic databases with peer-review criteria and grey literature searches through authoritative government sources.

All retrieved records underwent systematic screening against the predetermined inclusion criteria. Initial title and abstract screening identified potentially relevant sources, followed by full-text assessment to determine final eligibility. Duplicate records were removed using EndNote 20 software, during the screening process. Two reviewers independently conducted screening, with disagreements resolved through discussion.

After applying the inclusion criteria screening, 114 sources were retained in the final analysis (97 peer-reviewed articles and 17 grey literature documents). The literature search and screening process is adapted from the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram [

34] (see

Figure 2). This systematic approach captured both peer-reviewed evidence and current policy developments across the study’s interdisciplinary scope.

3.2. Participatory Design

Participatory Design was adopted as a method to directly address the literature gaps identified through the SLR, ensuring older persons lived experiences and knowledge were represented in the development of tailored bushfire retrofit guidance. In participatory design methods, the participant is assigned “the position of ‘expert of his/her experience’, and plays a large role in knowledge development, idea generation and concept development” [

35] (p. 12). The participatory approach positions older people as experts in their own experience rather than as passive research subjects. The following two phases were developed for the Participatory Design objectives: 1. Focus groups; 2. Case studies (see

Table 1).

Focus groups generate rich, descriptive data about participants’ experiences, perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs through structured group discussions [

36]. Case studies provide complementary data by enabling researchers to directly observe and document real housing conditions through architectural research methods of analysis [

37].

Focus group sessions were planned in each case study region (Bega Valley LGA and Noosa Shire LGA), with participants recruited through established local council networks. Eligibility criteria for the focus groups specified adults aged 55 years and over, a deliberate methodological decision that captured both current older local demographics (65+ years) and those in pre-retirement planning phases who anticipated ageing-in-place within bushfire-prone communities. This age range selection ensured the study addressed both immediate and anticipated future considerations related to bushfire resilience. Case study participants were then recruited from focus group attendees and voluntarily opted for further engagement with the study.

Researchers were sensitive to the potentially traumatic topics around bushfires and followed ethical protocols [

38]. Furthermore, ethics clearance was also obtained for this study. Participants provided informed written consent with guaranteed voluntary participation, withdrawal rights, and a choice between anonymity or acknowledgment in publications. All collected data were de-identified and securely stored in accordance with institutional research protocols.

3.2.1. Focus Group Protocols

The focus group methodology was employed to capture qualitative data through semi-structured group discussions to generate specific perceptions and ideas relating to the study objectives. The focus group sessions systematically collected the following three types of data:

Semi-structured discussions: Recording personal experiences, perceptions of risk, financial considerations, social networks, and barriers to implementing retrofits. These peer-to-peer discussions provided rich narrative data about decision-making processes and implementation challenges, as well as design preferences for an adapted toolkit.

Written artefacts: Participants were given the option to record their responses to discussion questions on paper and were also given a physical Property Assessment Form to complete.

Documents: Participants were asked to bring in photocopies of available floorplans of their property and insurance documents.

The focus group discussions were facilitated by the study researchers, first introducing the study to the focus group then presenting them with the current knowledge regarding bushfire risk and retrofit resources. A semi-structured discussion protocol was designed to address predetermined thematic domains aligned with the study objectives, facilitating focused yet open-ended discussions with participants [

39]. The sessions were recorded, transcribed, and later analysed for thematic content.

In addition to the discussions, participants completed a Property Description Form documenting demographic information (age range) and property characteristics including location, size (square metres), construction year, insurance status, and Bushfire Attack Level (BAL) rating where known. This form also captured previous bushfire retrofitting efforts undertaken by homeowners.

The collected data and documents informed a preliminary assessment of the bushfire resiliency of the focus group participants with insights on the vulnerability factors specific to them. The combination of focus group responses and property documentation also enabled the preliminary assessment of the participants’ suitability and interest in being a case study participant in the next phase of the Participatory Design.

3.2.2. Case Study Participant Protocols

Case study participants were recruited from focus group attendees and voluntarily opted for further engagement with the study. This phase of data collection required substantial fieldwork, with researchers conducting comprehensive 2 h on-site assessments at each case study participant’s house and property. The participants guided researchers through their property, highlighting areas of concern and any previous bushfire retrofit efforts. The case study assessments systematically collected the following two types of data:

Physical artefact data: Direct observations of existing housing conditions, potential vulnerabilities, and retrofit opportunities. These assessments included photographic documentation, measurements, and structural evaluations.

Semi-structured interviews: Individual interviews with the case study participants to record personal experiences, perceptions of risk, financial considerations, and barriers to implementing retrofits.

The direct observation of the housing conditions followed architectural research methods for case study analysis [

37]. Advanced documentation tools, a DJI Mavic Mini 3 Pro drone (2022 release) and an Insta 360 X3 camera (2022 release), were operated by researchers to capture consistent data across properties and the site-specific conditions. The drone was used to document roofing construction, condition, and surrounding landscape features, generating an aerial assessment. This aerial perspective captured critical vulnerability data including roof material integrity, presence of skylights, vegetation proximity, water storage infrastructure, and potential evacuation routes. In addition to the aerial footage, the 360 camera captured comprehensive 360° ground-level imagery of each property. These images were processed using H5P software (2023 release) to create interactive site walk-throughs that facilitated detailed post-visit analysis of exterior building elements and vegetation density, particularly in areas where drone coverage was limited by obstacles or regulations.

The semi-structured interviews conducted during the on-site assessment followed a standardised set of semi-structured open-ended questions to ensure comparability across participants as well as allowing for conversational flow [

39]. This interview approach allowed for consistent data collection across participants whilst recognising individual circumstances and concerns. The combined advanced documentation and contextual interviewing provided rich, triangulated data sets for each case study property, enabling detailed comparison across different housing typologies and regional contexts.

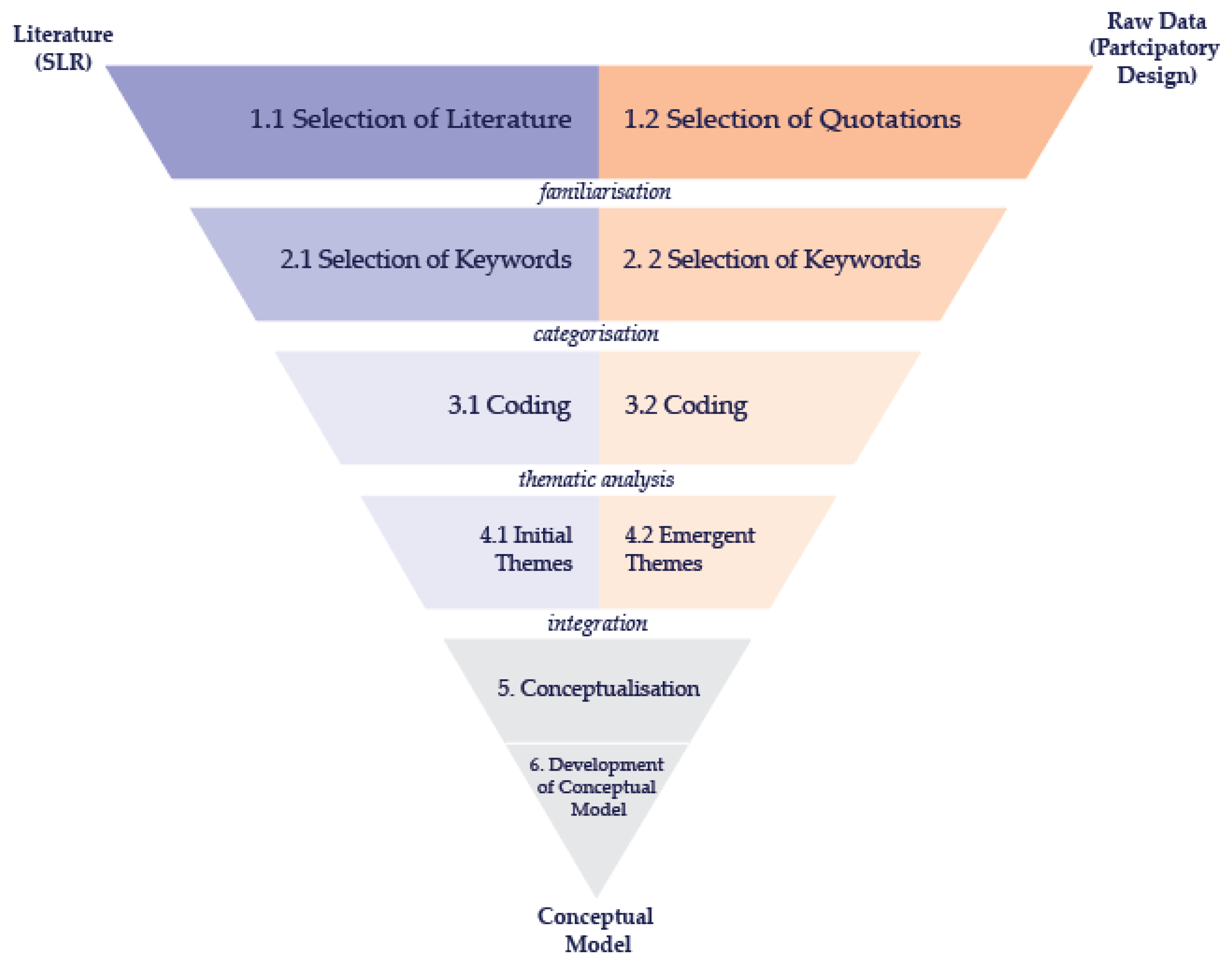

3.3. Data Analysis

Thematic analysis was employed to interpret the qualitative data from the following two distinct sources: literature from the SLR and primary data from the Participatory Design methods. This analytical approach was selected for its theoretical flexibility and systematic pattern identification capabilities, enabling both the deductive analysis of initial thematic frameworks and the inductive discovery of emergent themes [

40,

41]. This approach is particularly suited to the synthesis of diverse and interdisciplinary evidence sources.

The literature and raw data were coded in separate processes using NVivo 14 qualitative data analysis software, then thematically integrated into a cohesive conceptual model to capture both the existing knowledge and the participants’ lived experiences regarding bushfire resilience. The use of NVivo facilitated a transparent, traceable, and systematic approach to thematic analysis by enabling detailed organisation of coding frameworks across multiple data sources. The analysis involved multiple phases, beginning with familiarisation with the literature and data, followed by the development of a structured coding frame with main categories that focused the analysis on the study objectives [

42,

43], establishing each phase as a foundation for subsequent levels of analysis and interpretation (see

Figure 3).

The initial coding structure was informed by predetermined categories derived from bushfire resilience and ageing-in-place literature, although this framework remained flexible to accommodate emerging insights following the Participatory Design. The sequential phases of data coding, categorisation, and conceptual abstraction allowed the systematic refinement of the literature and raw data (transcripts and field notes) into a conceptual understanding of participants’ bushfire resilience experiences. This integrated approach enabled the identification of gaps between current guidance and older people’s actual perceptions and capabilities.

3.3.1. Analysis of Literature

Literature from the SLR was systematically coded according to conceptual similarities and thematic relationships, with codes subsequently collated into themes through iterative refinement processes. This analysis facilitated the identification of recurring information, methodological approaches, and implementation strategies within the existing context of retrofit guidance sources. The SLR employed a deductive approach using predetermined categories derived from bushfire resilience literature, with further evaluation against the literature on older people’s resilience.

3.3.2. Analysis of Primary Data

Audio recordings from the Participatory Design focus groups and semi-structured interviews were professionally transcribed verbatim and verified for accuracy against original recordings before analysis. NVivo 14 software was used to manage, code, and analyse the transcribed data from focus groups and case study interviews. All transcripts were imported and coded using a structured two-phase coding process. First, a deductive coding framework based on the study’s conceptual domains (e.g., disaster preparedness, ageing in place) was applied. This was followed by inductive coding that allowed emergent themes to be identified from participant discourse.

Several steps were also undertaken to enhance the rigour and assess the relative strength of identified themes to reduce interpretation bias. Thematic strength was determined by the following three main criteria: (1) recurrence across participants; (2) diversity of participants contributing to the theme (ensuring themes were not driven by single cases); (3) triangulation with literature, fieldwork observations, and review of documents. The analysis methods did not solely rely on frequency counts but instead balanced interpretive depth with evidence of thematic saturation.

Coding was conducted independently by two researchers, followed by a comparison and reconciliation of discrepancies to enhance analytical rigour [

44,

45]. The percentage agreement method was employed and calculated by dividing the number of coding decisions where both researchers assigned identical codes by the total number of coding decisions, then multiplying by 100. The independent coding process achieved 91% percentage agreement between coders, exceeding the minimum 80% threshold recommended for acceptable intercoder reliability in qualitative research and approaches the 95% standard often cited for high-quality qualitative analysis [

45,

46].

The high percentage agreement provides confidence that identified themes reflect genuine patterns in participant data rather than individual researcher interpretation or coding inconsistencies. This team-based approach to coding also reduced the potential for individual interpretive bias while enriching the analytical perspective.

4. Results

The results of this study revealed significant findings and insights regarding the development and adaptation of bushfire retrofit guidance appropriate for older people. The analysed data identified critical elements necessary for the content, communication, and implementation of retrofit measures.

The focus group recruitment resulted in 17 participants across the two study contexts, 5 from Bega Valley LGA and 12 from Noosa Shire LGA, summarised in

Table 2. The participant demographic profile aligned well with the study’s target demographic, with the majority of participants aged between 65 and 70 years. Out of the 17 participants, 11 remained engaged as case studies and stayed involved with the Participatory Design of the toolkit.

4.1. Thematic Synthesis

Integrated thematic analysis across literature and primary data sources yielded the following five thematic domains that collectively address the study’s research objectives and inform the toolkit development:

Disaster management and preparation.

Community resilience.

Bushfire building compliance and communication.

Lifestyle and personal heritage.

Personal perceptions toward retrofitting.

These domains reflect the integration of themes from the multi-method approach. The SLR established domains 1–3, providing the evidential foundation for current bushfire resilience approaches and a theoretical framework for understanding resilience in older people. The Participatory Design methods then identified domains 4–5, contributing contextual depth and nuanced knowledge to all themes. The synthesis revealed critical gaps between existing guidance and older people’s actual experiences, highlighting previously overlooked implementation barriers and opportunities for age-appropriate design solutions.

4.1.1. Disaster Resilience and Preparation

Analysis of grey literature sources demonstrated that there are significant reports published by National and State governments with recommendations and strategic objectives for disaster management and resilience (see

Table 3). The NSW, QLD, and VIC reports are especially prominent and specifically target bushfire management in response to the severe impact of the 2019–2020 Black Summer bushfires in Australia [

47]. These reports unanimously place emphasis on a shared responsibility approach between individuals, community, and emergency services [

48]. In shared responsibility approaches, ‘collective decision-making are prioritised more strongly, communities and non-government parties are more likely to have active roles in implementation and goal-setting’ [

49] (p. 12).

Australian policy does not currently enforce evacuation as mandatory in the event of bushfires, with this decision ultimately influenced by the threat-perceptions of individual households [

53,

54,

55]. However, the NSW Government recommends ‘mandatory evacuation orders’ with a ‘leave early’ approach to be implemented in high-risk communities [

50] (p. 13). Participants emphasised the need for personalised decision-making frameworks that accommodate individual values and priorities during disaster evacuation that go beyond current guidance, such as a more nuanced understanding of what to protect and what to retrieve [

56].

The data from participants who had previously experienced bushfires also indicated that there was a change in the prioritisation of their personal items during evacuation, becoming less attached to their material possessions to prioritise a fast and safe evacuation. Their trauma from past bushfires also removed the ‘stay and defend’ option, with the unanimous recommendation to evacuate and ‘leave early’ under all circumstances, consistent with the NSW recommendation.

Individual property maintenance was identified through the literature as a key consideration of bushfire preparedness [

57], NSW recognises ‘the individual responsibility for managing risk and making properties as safe as possible starting from the most local of levels’ [

50] (p. 5). There was similar emphasis amongst participants on the critical need for property owners to take proactive steps in bushfire preparedness, including creating defensible spaces, using fire-resistant materials, and maintaining vegetation to reduce fire risk. However, some participants reported the need to implement accessibility modifications, such as ramps, to increase mobility around their property for better maintenance capability. These adaptive home modifications can increase everyday resilience and mobility for older people, increasing capability for disaster management and self-care [

12,

58,

59,

60,

61]. Additionally, some participants experienced coordination difficulties with aged care services, which limited access to assistance with time-critical bushfire preparation measures.

In addition to bushfires, participants recognised increasing heatwaves as a concern, particularly when coupled with the risk of bushfires. Elevated temperatures and intense winds during heat waves can pose a significant health risk to older people [

62,

63,

64]. A management strategy for heatwaves was therefore seen as being needed to be integrated into the toolkit.

4.1.2. Community Resilience

The literature presented strategies for establishing communication frameworks at the community level to increase collective resilience and participation in bushfire risk mitigation initiatives [

65,

66,

67,

68]. Community resources—both formal and informal—were identified by participants as commonly accessed during bushfire events. Key community support during a bushfire included organised recovery centres, broadcasters offering live updates (NSW Rural Fire Service, Red Cross, and Australian Broadcasting Corporation), and informal communication networks such as phone trees.

There was consensus amongst participants that their local community were able to offer more support than family during bushfire events as participants mostly lived away from their children or immediate family. Disaster shelters play an especially important role in establishing community connection during and following a bushfire-event [

69]. There is also opportunity for inter-generational collaboration in building community resilience, with the more-abled community supporting the vulnerable [

70].

Following a bushfire event, participants also recognised the vital role of community-based knowledge transfer in building resilience capacity, emphasising that the collective sharing of recovery experiences and preparedness knowledge should be systematically integrated into toolkit frameworks [

71]. The experiences of older people should therefore be seen as an asset in building community resilience [

27].

4.1.3. Bushfire Building Compliance and Communication

Although the Australian Standard AS 3959-2018 provides the technical framework for building in bushfire-prone areas, it is generalised and does not target specific house typologies. The grey literature identified six published consumer-oriented resources, with industry credibility and government support, which provide building guidance that aims to interpret and simplify the complex technical requirements outlined in Australian Standard AS 3959-2018 (see

Table 4). Some of the resources even go beyond the guidance to target specific house typologies.

The evaluated toolkits exhibit considerable variation in their approach and level of detail, ranging from broad recommendations applicable to generic housing, to typology-specific guidance for existing building types, and to comprehensive construction specifications for new buildings. This diversity in approach indicates that there are different communication methods for translating technical standards into actionable recommendations for homeowners in bushfire-prone communities [

72,

73].

Table 4.

Comparison matrix of retrofit toolkits and bushfire building guidance reviewed.

Table 4.

Comparison matrix of retrofit toolkits and bushfire building guidance reviewed.

| Resource: | Author/s,

Year Published | Distribution

Method | Intended

Users | House

Types | Targeted

Regions: |

|---|

Minderoo

Climate-resilient Housing Toolkit | (Canberra Region Joint Organisation, 2020) [74] | Online, hardcopy, and community outreach | Local government regions and consumers | Weatherboard, old brick

veneer, metal clad, newer brick veneer, and timber clad | NSW/ACT |

| Green Rebuilt Bushfire Retrofit toolkit | (Renew, 2020) [75] | Online and

community outreach | Consumers | New build fire-resilient house | National |

| “Fortis House” model | (Australia, 2020) [76] | Online and hardcopy | Consumers needing to rebuild because of bushfire property loss | New build fire-resilient house | NSW |

| Best Practice Design for Building in Bushfire Prone Areas in Victoria | (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, 2020) [77] | Online only | Consumers and

building industry | Nonspecific | VIC |

| Bushfire Resilient Building Guidance for Queensland Homes | (Victorian Building Authority, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Leonard et al., 2020) [78] | Online and hardcopy | Consumers and

building industry | Two-storey slab on ground house, raised house on

a sloped site, Queenslander house, partly raised timber, and slab-on-ground

brick veneer house | QLD |

A guide to retrofit your home for better

protection from a

bushfire | (Victorian Building Authority, 2014) [79] | Online and hardcopy | Consumers and

building industry | Nonspecific | VIC |

Although these resources are publicly available, access to information presented a major concern, with participants feeling inadequately informed about current building regulations and available retrofit options. In terms of how this information is communicated, participants advocated for multi-modal information delivery (physical documentation, digital resources, and video demonstrations) reflecting diverse learning preferences and technological access variations. Communication effectiveness of the message design, content, and delivery mechanisms directly determines information uptake and behaviour change for bushfire-related risks [

80,

81,

82].

Advanced communication tools were also found to present limitations for older people. Immersive communication tools such as VR and AR are technically complex and demand considerable expertise in the development, setup, and use when applied to bushfire risk communication [

83]. Spatial constraints and limited hardware availability further restrict audience reach during immersive demonstrations, reducing the scalability and accessibility of these tools for older people [

23].

Participants were also interested in building guidance that incorporated renewable energies and sustainable infrastructures including water collection systems, solar power, and electrical infrastructure protection [

84,

85].

4.1.4. Lifestyle and Personal Heritage

The resilience and independence of older people’s lifestyles are fundamentally determined by their mobility and housing liveability, specifically measured through accessible building standards and maintenance requirements [

58]. Factors such as housing affordability, deep-rooted community attachments, and established social support networks further influence the decision of older people to age-in-place in bushfire-prone regions [

86]. However, the majority of housing in Australia is not designed with the accessibility and liveability of older people in mind [

12]. Therefore, bushfire retrofit guidance targeted at older people should consider guidance on liveable home modifications as integral to the bushfire resilience and lifestyle improvements of older people [

87,

88].

Participants exhibited varied patterns in the time duration spent at their main residence across the year, with the more mobile having families in other regions or states to visit. The amount of time spent away from their properties can affect their decision to ‘stay or defend’ during a bushfire event. Participants were also varied in their responses towards the value of their landscape assets (gardens and significant trees), as some participants viewed gardening as part of their lifestyle while others preferred a low-maintenance approach to their landscaping.

Discussions around evacuation procedures revealed distinct prioritisation patterns among participants’ personal heritage items. Personal identification documents were identified as primary items to retrieve and protect, while emotionally significant items ranked as a secondary consideration that could potentially be safeguarded through protective infrastructure such as storage sheds or purpose-built shelters.

There was consistently strong personal value assigned to non-monetary possessions with emotional significance, such as pets and heirloom artefacts. Companion animals were integrated into evacuation strategies, while livestock management strategies relied on cooperative neighbour-based arrangements.

4.1.5. Personal Perceptions Towards Retrofitting

The implementation of bushfire preparedness faces significant barriers across governmental regulations, professional practice limitations, and insurance requirements [

89,

90,

91]. Governmental and insurance obstacles centred on administrative complexity, particularly regarding funding applications, where participants expressed frustration with unclear eligibility criteria, prolonged approval processes, and perceived insensitivity towards past trauma (from bushfire events) throughout application procedures. Financial literacy is a major factor in how individuals access funding for bushfire recovery [

92] or understanding the limitations of their insurance cover [

93].

Participation and engagement with local trades in the implementation stage were also key considerations for the retrofit toolkit outcome. However, professional service limitations emerged as significant impediments, with participants reporting difficulty accessing qualified tradespeople educated in bushfire-specific retrofit work. This shortage of specialised contractors creates delays and uncertainty when seeking professional assistance with property modifications. At the personal level, participants encountered multiple challenges, including physical constraints that prevented independent implementation of complex retrofit measures and/or property maintenance. Therefore, DIY-scale home modifications are more viable for short-term investment and implementation, with more decision-making tools required to make the right modification choices [

94,

95].

Concerns about non-compliance, including the risk of fines or needing to redo retrofitting work, were common. A key compliance requirement is securing an assessment from the local council and the Rural Fire Service (RFS) before starting a retrofit [

96]. This step evaluates bushfire risk and is a prerequisite for council building approvals. Participants described this process as bureaucratically burdensome, involving delays, paperwork, and uncertainty, which discourages many from pursuing essential upgrades.

Furthermore, participants reported difficulty in making informed decisions about bushfire safety improvements. Many found it challenging to select appropriate materials while also ensuring compliance with complex fire safety regulations and building standards, especially when retrofitting older homes that do not meet current codes.

5. Design, Testing and Validation

The results from the study directly informed the development of the Adapted Toolkit Design, contributing to the content and communication frameworks within the toolkit. The result was a multi-modal toolkit titled ‘Retrofit Toolkit for Bushfire Resilience: Making it work for older people’, which was comprehensively designed to address the diverse needs and capabilities of older people in bushfire-prone areas.

The toolkit developed a scalable approach, defined in this study as retrofit interventions that can be adapted in scope, complexity, and cost, to suit a wide range of implementation capabilities. Scalability in the context of this toolkit therefore implies a flexible staged approach to retrofitting and supports various tiers of effort and cost upgrades over time. This approach aims to allow users of the toolkit to effectively tailor retrofit actions according to their unique circumstances.

5.1. Adapted Toolkit Design Method

The development of the adapted retrofit toolkit integrated the SLR findings with empirical data to establish design objectives within a preliminary framework for the content and communication of the Adapted Toolkit, which is outlined as follows:

Content—Identifying key information and guidance relevant to include in the toolkit, through the synthesis of the following three primary knowledge domains: technical bushfire resilience requirements, ageing-in-place design principles, and age-related perceptions of bushfire risk.

Communication—Identifying communication tools and methods that appropriately communicate the toolkit content.

The method for developing the content framework utilised a matrix mapping approach where findings were systematically organised into a conceptual framework, identifying critical domains for toolkit content as identified through the data analysis. This methodological approach enabled the rigorous categorisation and prioritisation of critical information domains identified through the case study analysis. The resultant content framework established clear thematic boundaries and hierarchical relationships between key content elements, ensuring comprehensive coverage of essential retrofit considerations for older people.

The content framework was then translated into a communication framework prototype. These frameworks developed the visual design of organised categories of information, hierarchical text structures, and supportive visual components (images and diagrams) for the preliminary testing of comprehension across varying cognitive and visual capabilities. This systematically developed prototype enabled subsequent validation through participatory design methodologies, enabling evidence-based refinement based on user testing and expert consultation.

5.2. Content Framework Design

The content development of the toolkit was guided by perceptions analysed from the study participants and reflects the thematic domains established in the results. The goal was to provide educational and practical content to support informed retrofitting implementation for bushfires.

Results following the Participatory Design further identified the following key priorities for the content:

Inclusion of varied lifestyle preferences of older people.

Easy-to-understand information on building compliance.

Scalable retrofit measures for the building and landscape.

Decision-making support for retrofit planning and preparedness.

Community preparedness measures.

The structure of the toolkit aims to present retrofitting decisions in a clear and logical sequence. It includes sections on lifestyle considerations, bushfire risk classifications, key definitions (such as Bushfire Attack Level), and practical disaster preparation steps.

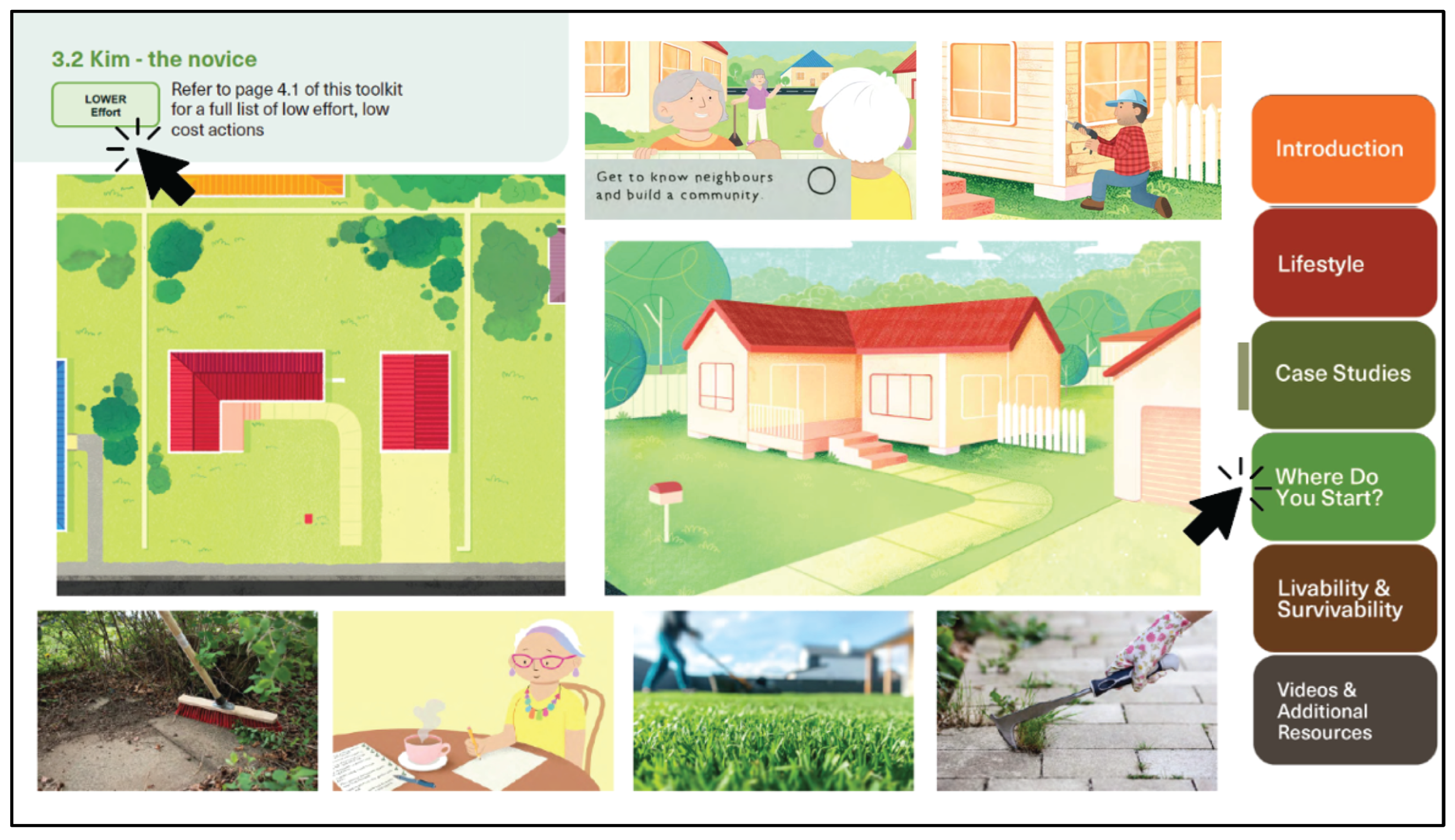

5.2.1. Toolkit Structure

The order and layout of the content in the toolkit aims to help users find targeted information quickly and apply it to their specific lifestyle. The content follows a clear and logical sequence that builds understanding and supports informed decision-making, whilst also allowing the user to quickly find the relevant sections (see

Figure 4).

The sequence of content reflects a user-centred design, guiding older people step-by-step through the process of preparing their homes and surroundings for bushfire threats. The content also reflects the key thematic domains resulting from the study (see

Table 5).

To build foundational understanding the toolkit then defines retrofitting and explains its relevance to bushfire resilience. The toolkit presents current retrofit guidance, synthesising up-to-date recommendations based on lessons from the Black Summer bushfires. This ensures that users receive evidence-based strategies tailored to present conditions. The toolkit further incorporates relevant information beyond retrofitting to cover disaster preparation strategies and community preparedness.

5.2.2. Scalable Implementation Strategies

To address the key priority of ‘scalability’ identified from this study, the toolkit presents retrofit measures organised by three tiers of effort and cost—lower, moderate, and higher. This allows the identification of both short-term actions and long-term investments, enabling older people to plan and implement measures according to their current needs, capabilities, and available resources.

Each tier of effort and cost is based on the physical and financial effort as considered by the toolkit user but indicates that any measure will have a positive impact on their bushfire resilience. The tiers are as follows:

- ○

Higher effort and higher cost measures—large-scale, more complex, and costly upgrades, such as replacing non-compliant roofing, requiring professional assistance from trades.

- ○

Moderate effort and moderate cost measures—medium-scale upgrades with manageable costs, such as replacing doors and installing shutters, potentially requiring professional assistance.

- ○

Lower effort and lower cost measures—small-scale upgrades or maintenance with little cost, such as maintenance of sealed walls and upkeep of landscaping. Although low effort measures can generally be performed without professional assistance, it does not rule out that some older people might still require external assistance.

The development of these categories was informed by field research, expert consultation, and analysis of property-level risk factors, including site conditions, building materials, climate exposure, and user capability. Actions were assessed for feasibility, affordability, and effectiveness in reducing bushfire risk, further considering the range of mobility, cognitive, and/or financial limitations of older people.

These effort and cost considerations were further supplemented with a prioritisation framework to indicate the impact of the retrofit measures to assist homeowners with navigating trade-offs between resource availability and risk reduction outcomes. The prioritisation metric will aim to assist with further cost-analysis and informed decision-making around the retrofit measures within the toolkit.

5.3. Communication Framework Design

The study participants expressed a preference for multi-modal information delivery (a physical document, digital accessibility, and short videos), while demonstrating some technical literacy and capability. Due to the current limitations for consumer adoption of advanced technologies, such as VR [

23], such methods were not considered suitable for older people.

As a result, the communication framework was developed into an interactive PDF that could be digitally accessed online or offline and printed as a physical document. The interactive PDF was supplemented by a series of short video animations to incorporate animated visual and audio content. The multi-modal communication framework of the toolkit provides clear headings, visual aids, and animations to simplify complex information while supporting diverse learning styles. These elements were combined to make the information engaging, easy to understand, and relevant to bushfire retrofit decisions.

Case study character representation was also graphically developed along with detailed user profiles that aligned with each tier of the toolkit’s implementation framework as follows: 1. The novice (low ability); 2. The upgrader (moderate ability); 3. The expert (high ability). These profiles, derived from the composite analysis of participant characteristics, housing conditions, and retrofit approaches observed during fieldwork, served as design personas to establish some level of relatability and relevance for users of the toolkit (see

Figure 5). The case study characters and graphic style representing the housing scenarios are consistent in both the interactive PDF and short animations.

5.3.1. Interactive PDF

The interactive PDF design includes clickable icons, live links, and embedded videos, allowing users to explore specific topics and access tailored guidance. The toolkit also integrates dynamic tables, charts, and flowcharts that users can interact with to assess retrofitting options based on cost, effort, and priority. These interactive tools guide users through planning decisions linked to their property, lifestyle, and risk level.

Icons prompt personal reflection on living circumstances and preferences, helping users link these to practical retrofitting actions. Clear navigation and a simple layout support older users and others with limited digital experience. The interactive format enables users to engage with the material at their own pace, making bushfire preparedness more accessible and actionable.

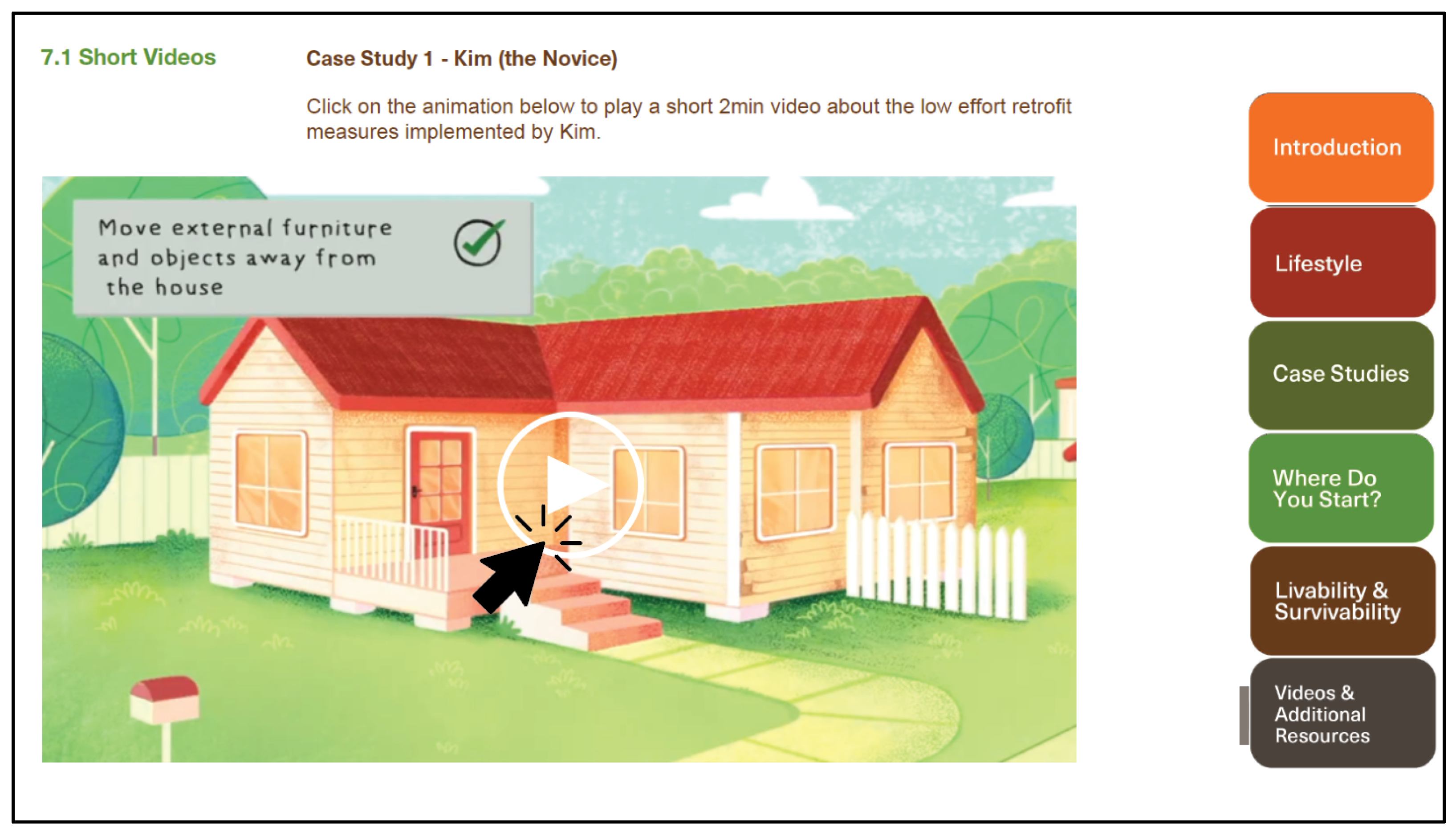

5.3.2. Short Animations

The inclusion of short video animations within the toolkit supports user understanding of bushfire resilience by breaking down complex retrofitting processes into clear, step-by-step visual and audio sequences. The animations show real-life scenarios adapted from the case studies. Visual storytelling and multi-media learning can make the content and instructions easier to absorb, particularly for users with limited technical knowledge, by invoking memory and emotion [

97]. This approach helps users connect abstract concepts to tangible actions.

The animations illustrate key actions, such as vegetation management, use of fire-resistant materials, and emergency planning, so users can see how recommended measures work in practice for different house typologies. By guiding users through each step, the animations reinforce key messages and support better memory recall and application. Animations are embedded within the PDF and can be viewed offline, ensuring accessibility alongside other interactive features (

Figure 6).

5.4. Participatory Design and Validation

The industry and community participation in the design and validation process aimed to ensure continued interest and engagement with the study, with scope for future adaptations. The final phase of the study tested and validated the usability, technical accuracy, and implementation of the toolkit from the following two domains of knowledge:

End-users—Participants from the case study regions continued to provide experiential knowledge and feedback based on lived experience in bushfire-prone areas. This group included representation across age brackets (65–85 years), various housing typologies, physical capabilities, and previous bushfire exposure.

Industry experts—Specialists in bushfire resilience, building practice, and ageing resilience provided expert knowledge based on professional expertise. This group was strategically selected to ensure a comprehensive evaluation across all technical domains addressed in the toolkit.

Researchers facilitated testing and validation workshops online (in 60–90 min sessions) to guide the evaluation of the content and communication frameworks of the Adapted Toolkit Design. These sessions followed a standardised protocol that directed end-users and industry experts through specific toolkit sections while documenting responses using a combination of open-ended prompts and semi-structured interview questions.

Evaluation criteria included clarity of information, visual accessibility, ease of navigation, perceived usefulness, and alignment with individual bushfire resilience concerns. The evaluation process captured specific design recommendations, usability concerns, and implementation considerations. Feedback and insights from the workshops were synthesised using a structured analytical framework that weighted recommendations according to frequency, relevance, and feasibility. Revisions to the toolkit were then implemented in response to the feedback and insights, with notable changes including simplified language, enhanced visual contrast, restructuring of information flow, and further inclusion of illustrative examples.

This systematic analysis informed three sequential design refinement iterations, with each version subjected to focused validation with the research team, and a subset of participants to confirm improvements. These refinements ensured that the toolkit better aligned with the study objectives.

6. Discussion

The integration of systematic literature review with a participatory design methodology generated critical insights into the disconnect between existing bushfire retrofit guidance and older people’s lived experiences and capabilities. These findings informed the development of the Adapted Toolkit Design ‘Retrofit Toolkit for Bushfire Resilience: Making it work for older people’, which introduces a fundamentally different approach to retrofit guidance.

6.1. Novel Contributions of the Adapted Toolkit and Comparisons with the Existing Literature

The majority of the current guidance produced by state-level emergency fire services, building authorities, and local governments tends to be technical and targeted at homeowners with the capacity to undertake or commission major property upgrades independently. In comparison to the existing guidance that primarily features technical building regulations, this toolkit’s approach recognises that older people’s housing needs, daily routines, and personal preferences fundamentally shape their capacity and willingness to implement retrofit measures, as identified in the thematic outcomes of this research. This study’s primary contribution lies in developing the first age-specific bushfire retrofit toolkit that prioritises lifestyle assessment as the foundational step in retrofit decision-making.

This lifestyle-first framework represents a paradigm shift from the traditional ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to disaster resilience guidance. Participants consistently identified various retrofit barriers related to financial and physical constraints, which existing guidance fails to acknowledge. By establishing personal circumstances as the entry point, the toolkit ensures that retrofit recommendations align with users’ actual capabilities, constraints, and values rather than imposing generic technical solutions that may be inappropriate or unachievable for older people. The toolkit’s scalable tiered approach to implementation therefore directly addresses these previously unrecognised implementation barriers.

To bridge the gap between current bushfire retrofit guidance and accessible universal housing design principles, the toolkit content framework comprehensively integrates guidance from the AS 3959-2018 with the

Livable Housing Design Handbook, both published by the Australian Building Codes Board [

13,

98]. The toolkit content section ‘Livability and Survivability’ outlines retrofit measures that target the increase in mobility around the house and improve property maintenance ability as well as ease of evacuation. This targeted guidance for older people ageing-in-place is in line with the current evidence-based literature around ageing-in-place housing design considerations [

12,

59,

99], which is not represented in current bushfire retrofit guidance.

The current guidance further lacks evidence of participatory design and visual representation of older people. The participatory design and validation process of the Adapted Toolkit Design therefore presents a novel approach, demonstrating the importance of end-user testing and incorporating visual representations that older people can identify with, ensuring the relevance and relatability of the toolkit.

6.2. Nuances in Ageing Perspectives

While the study focused on older Australians aged 65 and over, the research intentionally included participants aged 55–64 to capture a broader spectrum of ageing-related housing decisions to identify important developmental differences in retrofit perspectives. The perspectives captured from this broader age range confirmed current gerontological understanding that ageing-in-place planning should begin well before the 65-year retirement threshold, when individuals first begin anticipating future housing and health needs, consistent with the literature on retirement transition planning behaviours [

99,

100].

Pre-retirement participants (55–64) therefore demonstrated future-oriented planning approaches, focusing on anticipatory modifications and long-term property investment decisions. In contrast, participants aged 65+ emphasised present-capability considerations and identified more specific ageing-related challenges such as the level of accessibility and maintenance of their homes. Within the 65+ cohort, perspectives also varied significantly, reflecting the heterogeneity of ageing experiences [

101].

These age-related differences directly informed the toolkit’s novel approach of prompting older people to self-evaluate their lifestyle needs and retrofit capabilities, rather than approaching them as a homogenous group.

6.3. Limitations

Several limitations constrain this study’s scope and generalisability. The toolkit remains a prototype that has been tested in a limited capacity due to the initial scope of the study and has not yet undergone large-scale implementation or longitudinal evaluation to assess its impact.

6.3.1. Geographic Scope and Transferability

Limiting the research to two case study regions potentially restricts transferability to other Australian geographic contexts and reduces relevance for international applications. However, the selected regions can provide valuable comparative insights through their climatic diversity—Bega Valley (NSW, temperate climate) and Noosa Shire (QLD, subtropical climate)—alongside different state regulatory environments and varying housing typologies. Additionally, both regions have demographic trends consistent with Australia’s ageing population and are on the east coast of Australia which has a significantly dense population [

102], factors which allow the study to maintain demographic comparability and relevance.

6.3.2. Participant Selection and Representation

Focus group participants demonstrated independent mobility (although the level of mobility was varied across the participants with some requiring walking aids) and sufficient technical ability to engage with research activities, potentially creating a selection bias towards more capable older people. This limitation means that individuals with significant physical disabilities, cognitive impairments, severe mobility restrictions, or limited digital literacy (who may face the greatest challenges in implementing bushfire retrofits) are likely underrepresented in the study findings.

This participant profile constraint has several implications for the research outcomes. The toolkit design and implementation recommendations may not fully address the needs of older people requiring extensive care support, those with limited financial agency, or individuals who face substantial barriers to home modification decision-making. Additionally, the communication strategies developed through user testing may be less effective for older people with more pronounced age-related conditions or those who are digitally excluded.

It is also important to note that the small participant pool prevents statistical analysis and therefore limits the representation of the broader population of older Australians in bushfire-prone areas.

6.3.3. Housing Typology Representation

The housing typology coverage in this study focused on dominant regional building types which were single detached dwellings. As a result, this study may not comprehensively represent Australia’s diverse housing stock in bushfire-prone areas to include other housing typologies such as apartments and townhouses. The focus on owner-occupied detached dwellings also potentially excludes rental properties, where retrofit decision-making involves landlord–tenant dynamics and different financial incentive structures which are not within the current scope of the research. These constraints suggest that while the toolkit provides valuable guidance for the most common housing scenarios, additional research and toolkit adaptations would be necessary to address the full spectrum of housing contexts where vulnerable older Australians reside in bushfire-prone areas.

6.4. Future Research Agenda

The future research agenda will seek to address the limitations identified in this study while deepening the knowledge base surrounding the implementation of age-appropriate bushfire retrofit guidance. Rigorous implementation research should be undertaken to assess the toolkit’s real-world effectiveness across different geographic, socio-economic, and broader housing contexts. Longitudinal research is also needed to evaluate how the toolkit performs over time, beyond the scope of validation workshop sessions. This will allow for a better understanding of its sustained use, user adaptation, and long-term impact on preparedness and retrofitting behaviour in ageing populations. Such studies could provide the evidence base required to scale the toolkit’s deployment nationally and to support policy alignment.

Given that the study’s participatory activities required a certain level of cognitive and physical capability, future research should explore inclusive alternatives, such as caregiver-assisted participation, simplified risk assessment tools, or proxy interviews, to ensure representation of the most vulnerable older people. Further user experience (UX) research is warranted to investigate barriers to digital accessibility, particularly among older people with physical, sensory, or cognitive impairments. This includes further evaluation of the toolkit’s interface design, information structure, and the suitability of different delivery formats.

The dynamic nature of bushfire resilience knowledge also necessitates regular content updates to maintain accuracy and relevance as standards, technologies, and policies evolve. To support the continued adaptation of the toolkit, future research efforts will benefit from interdisciplinary collaboration across fields such as gerontology, architecture, property economics, risk communication, and disaster resilience. Bringing together diverse disciplinary perspectives will enable a more holistic approach, bridging technical retrofit knowledge with the complex intersection of ageing, climate-adaptation design, and resilience in bushfire-prone communities. Further expertise from property economists and insurers will also provide clearer cost-analysis considerations. Building on the toolkit’s existing prioritisation framework, such collaboration will enable the development of robust cost–benefit models to guide decision-makers in evaluating retrofit options based on effort, affordability, and resilience impact.

The participatory design methodology employed in this study also proved effective in fostering collaborative, community relevant, user-centred outcomes. Future studies may adapt this approach for use in other bushfire-prone communities to generate region-specific toolkits. Moreover, the principles and processes developed in this study may serve as an interdisciplinary model for international efforts to co-design inclusive, context-specific resilience tools.

6.5. Practical Recommendations

The findings of this study highlight opportunities for embedding the ‘Retrofit Toolkit for Bushfire Resilience: Making it work for older people’ into broader disaster preparedness policies and implementation pathways via relevant service providers. A key gap identified in this study is the need for structured engagement with professional trades, aged care service providers, state fire services, and local community support. These stakeholders play critical roles in both the dissemination and practical implementation of retrofit guidance. The study recommends that each of these stakeholder groups assess their current capacity, incentive structures, and training requirements to support effective toolkit integration within existing service delivery and construction ecosystems.

There is also significant potential for local councils and emergency services to play a more active role in outreach to at-risk individuals. To support this, a coordinated network between local governments, community-based organisations, aged care providers, and disaster resilience agencies should be established to develop effective information distribution channels and place-based engagement strategies. Such a network would facilitate awareness of the toolkit, enable peer-to-peer learning, and foster community resilience. Such strategic partnerships could enhance both uptake and integration of the toolkit into local resilience-building programmes.

7. Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive synthesis of how bushfire retrofit guidance can be effectively adapted for older people, addressing critical gaps in current disaster resilience approaches. Through the systematic literature review and Participatory Design within the Bega Valley and Noosa Shire regions, the study revealed the following five key themes that integrate technical information with personal perceptions: disaster management and preparation; community resilience; bushfire building compliance and communication; lifestyle and personal heritage; and personal perceptions toward retrofitting.

The findings address the key study objectives by demonstrating that adapted bushfire retrofit guidance tailored for older people can do the following:

Address the fundamental gaps in current toolkits that inadequately serve older people’s diverse physical, financial, and cognitive capabilities.

Acknowledge the critical role of community participation and engagement in building collective disaster resilience.

Enable inclusive implementation through multi-modal communication approaches and scalable priority systems that accommodate varying user capacities.

Integrate ageing-in-place principles with technical building standards to create comprehensive resilience solutions.

The study has further highlighted the current disconnect between standardised technical building requirements and individual user capabilities, emphasising that effective disaster preparedness must be supported by accessible communication, flexible implementation pathways, and recognition of diversity to deliver relevant, impactful guidance. By adopting user-centred design over a one-size-fits-all approach, the study results contribute to more inclusive and effective disaster resilience frameworks. Without tailored adaptation, bushfire guidance risks excluding vulnerable populations who face the greatest disaster impacts.

Future studies should expand on the toolkit’s foundations by evaluating long-term toolkit effectiveness through continued engagement with vulnerable communities in bushfire-prone areas and it should be flexible to future adaptations.