A Habitat-Template Approach to Green Wall Design in Mediterranean Cities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

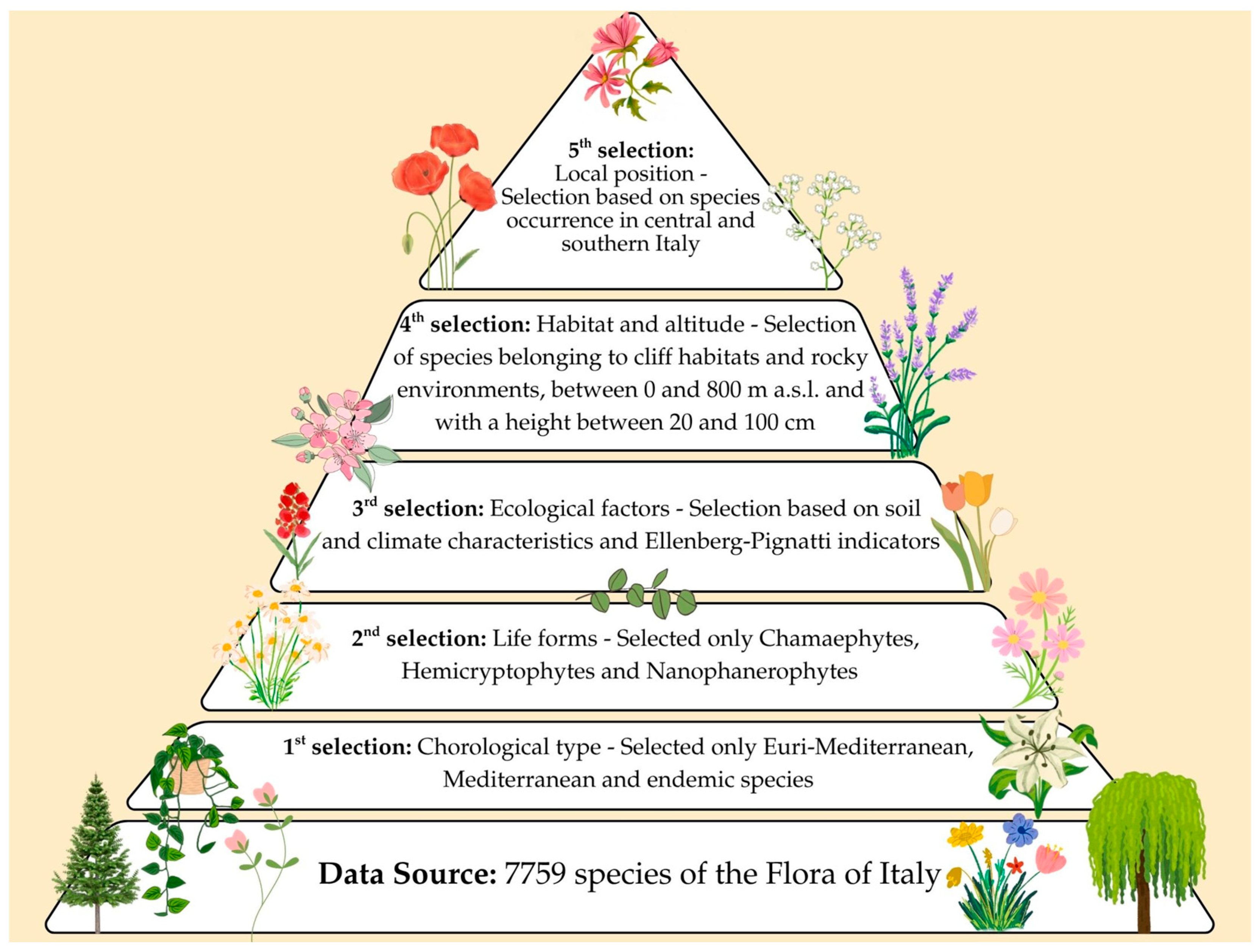

- First selection step: A chorological filter was applied, selecting only Mediterranean and Euro-Mediterranean species, including endemics, as these are best suited to the environmental conditions of Mediterranean cities [40].

- Second selection step: Species were further filtered based on plant growth forms, considering the structural characteristics of GW systems. The life forms considered were those defined by Raunkiaer [41], as reported in the digital database of Flora d’Italia [36,37,38,39]. Specifically, Chamaephytes, Hemicryptophytes, and Nanophanerophytes (sensu Raunkiaer) were selected, since it is believed that due to their structure, they are suitable for use in GWs. Chamaephytes are semi-shrubs, small shrubs, and cushion plants with low buds; hemicryptophytes are herbaceous perennials with buds at the ground level; and nanophanerophytes are small woody plants usually densely branched from the base. Conversely, Therophytes, Hydrophytes, Geophytes, and Phanerophytes were excluded for the following reasons: Therophytes are annual species and do not ensure continuous coverage; Hydrophytes require aquatic environments; Geophytes spend part of the year in dormancy below ground; and Phanerophytes include trees and large shrubs that are generally too bulky for vertical systems. These three life forms—Chamaephytes, Hemicryptophytes, and Nanophanerophytes—have proven to be structurally compatible with limited substrates, frequent exposure, and seasonal stress, as also confirmed by other studies on vertical greenery in Mediterranean areas [22,42]. Furthermore, the life form classification by Raunkiaer [41] provides a structural basis for evaluating plant adaptability in artificial systems such as green walls.

- Third selection step: The remaining species were screened based on pedoclimatic and ecological characteristics. This was achieved by applying the Ellenberg Indicator Values [43], as revised and adapted for Italian flora by Pignatti et al. [39], in conjunction with minimum altitude data reported in the same database. The Ellenberg–Pignatti indicators provide an ecological scale expressing the environmental preferences of plant species along several gradients. Each index is represented by a numerical value indicating a species’ tolerance or adaptation to a specific environmental factor. The indicators considered were

- Light (L)—the preference for shaded or sunlit environments (0 ≤ x ≤ 12).

- Temperature (T)—the distribution of species along a thermal gradient, from colder to warmer areas (0 ≤ x ≤ 12).

- Continentality (K)—sensitivity to seasonal thermal variation along the oceanic–continental climate continuum (0 ≤ x ≤ 9).

- Moisture (U)—species’ water requirements, from arid to highly humid or submerged environments (0 ≤ x ≤ 12).

- Nutrients (N)—soil fertility requirements for plant growth, from poor to nutrient-rich soils (0 ≤ x ≤ 9).

- 5.

- Fourth selection of species according to habitat type, growing altitude, and plant height: Only species from purely Mediterranean habitats of community interest [26], such as cliffs, grasslands, garrigue, and scrub—listed in Table 2—were selected. Only species with a natural distribution between 0 and 800 m a.s.l. were considered, excluding those whose minimum altitudinal range starts at 700 m or higher, as they are typically associated with montane habitats. Furthermore, only species with an average adult height between 20 cm and 1 m were retained, as this height range is structurally and functionally suitable for integration into green wall systems.

- 6.

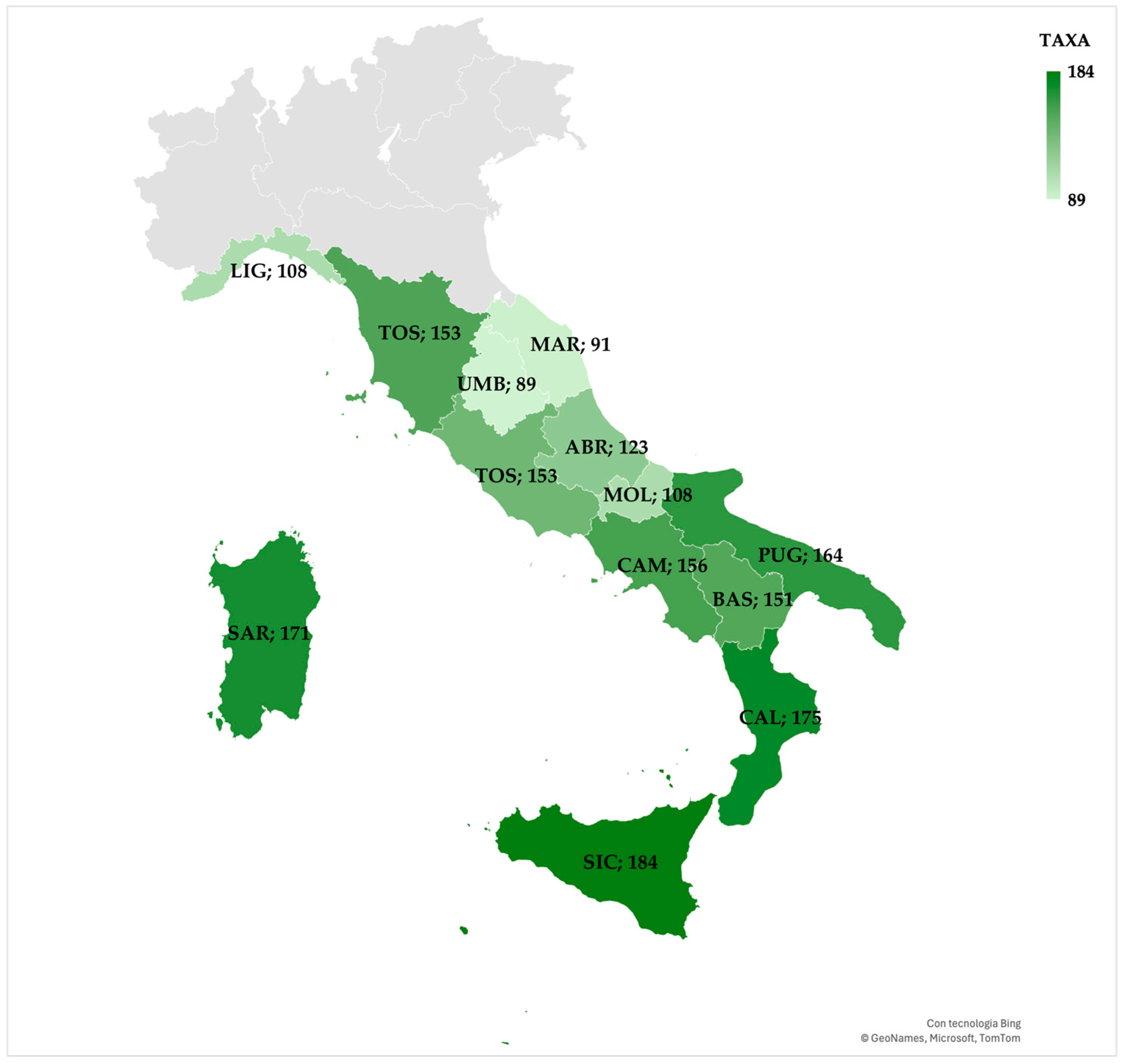

- Fifth and final selection of species based on their distribution in Central and Southern Italy, excluding those absent from these areas: At this stage, regional-scale distribution was also considered to define species pools for use in each Italian region with a Mediterranean climate. This step is particularly important for endemic species—sometimes restricted to a single region—as it prevents the use of such species outside their natural range, thus safeguarding local biodiversity.

3. Results

- First selection—based on chorological type: From a total of 7759 species, 4296 species were selected.

- Second selection—based on growth characteristics, i.e., the life form of plants: From 4296 species, 2226 species were selected.

- Third selection—based on pedoclimatic and ecological characteristics: From 2226 species, the selection was narrowed down to 1308 species.

- Fourth selection—based on habitat type, growth altitude and plants height: From 1308 species, 666 species were selected.

- Fifth selection—based on species distribution, limited to Central and Southern Italy: The result was the selection of 368 species, identified as potential candidates for implementation in smart GI within the Mediterranean area.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GI | Green Infrastructure |

| GW | Green Wall |

| LAI | Leaf Area Index |

| NBS | Nature-Based Solutions |

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Zhao, X.; Zuo, J.; Wu, G.; Huang, C. A bibliometric review of green building research 2000–2016. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2019, 62, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghansah, F.A.; Owusu-Manu, D.; Ayarkwa, J.; Darko, A.; Edwards, D. Underlying indicators for measuring smartness of buildings in the construction industry. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2020, 11, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addo-Bankas, O.; Zhao, Y.; Vymazal, J.; Yuan, Y.; Fu, J.; Wei, T. Green walls: A form of constructed wetland in green buildings. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 169, 106321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, C.; Pasta, S.; Guarino, R. A plant sociological procedure for the ecological design and enhancement of urban green infrastructure. In Urban Services to Ecosystems: Green Infrastructure Benefits from the Landscape to the Urban Scale; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 31–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzan, M.V.; Geneletti, D.; Grace, M.; De Santis, L.; Tomaskinova, J.; Reddington, H.; Sapundzhieva, A.; Dicks, L.V.; Collier, M. Assessing nature-based solutions uptake in a Mediterranean climate: Insights from the case-study of Malta. Nat.-Based Solut. 2022, 2, 100029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisuwan, T. Applications of biomimetic adaptive facades for enhancing building energy efficiency. Int. J. Build. Urban Inter. Landsc. Technol. 2022, 20, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, F.; Cardinali, G.D.; Bruno, R.; Arcuri, N. Sustainability Assessments of Living Walls in the Mediterranean Area. Buildings 2024, 14, 3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, J.; Gedge, D.; Early, P.; Wilson, S. Building Greener—Guidance on the Use of Green Roofs, Green Walls and Complementary Features on Buildings; CIRIA Press: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Canet-Marti, A.; Pineda-Martos, R.; Junge, R.; Bohn, K.; Paço, T.A.; Delgado, C.; Baganz, G.F.M. Nature-based solutions for agriculture in circular cities: Challenges, gaps, and opportunities. Water 2021, 13, 2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenta, M.; Quadri, A.; Sambuco, B.; Perez Garcia, C.A.; Barbaresi, A.; Tassinari, P.; Torreggiani, D. Green roof management in Mediterranean climates: Evaluating the performance of native herbaceous plant species and green manure to increase sustainability. Buildings 2025, 15, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, I.; Convertino, F.; Schettini, E.; Vox, G. Wintertime thermal performance of green façades in a Mediterranean climate. In Urban Agriculture City Sustainability II; WIT Press: Southampton, UK, 2020; Volume 243, p. 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartvelishvili, A. Exploring Adaptive Façade as Mitigation Strategy Though Gis-Based Urban Microclimate Analysis. Master’s Thesis, Politecnico di Torino, Torino, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Carlucci, S.; Charalambous, M.; Tzortzi, J.N. Monitoring and performance evaluation of a green wall in a semi-arid Mediterranean climate. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 77, 107421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkar, H.; Sui-Reng, L.; Theingi, A.; Amiya, B. Green facades and renewable energy: Synergies for a sustainable future. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2023, 8, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Founda, D.; Santamouris, M. Synergies between Urban Heat Island and Heat Waves in Athens (Greece), during an extremely hot summer (2012). Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musarella, C.M.; Laface, V.L.A.; Angiolini, C.; Bacchetta, G.; Bajona, E.; Banfi, E.; Barone, G.; Biscotti, N.; Bonsanto, D.; Calvia, G.; et al. New Alien Plant Taxa for Italy and Europe: An Update. Plants 2024, 13, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimondo, F.; Trifilò, P.; Lo Gullo, M.A.; Andri, S.; Savi, T.; Nardini, A. Plant performance on Mediterranean green roofs: Interaction of species-specific hydraulic strategies and substrate water relations. AoB Plants 2015, 7, plv007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, R.W.; Taylor, J.E.; Emmett, M.R. What’s ‘cool’ in the world of green façades? How plant choice influences the cooling properties of green walls. Build. Environ. 2014, 73, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowdar, H.S.; Hatt, B.E.; Breen, P.; Cook, P.L.M.; Deletic, A. Designing living walls for greywater treatment. Water Res. 2017, 110, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano Carmona, E.; Piñar Fuentes, J.C.; Cano-Ortiz, A.; Quinto Canas, R.; Rodríguez Meireles, C.; Raposo, M.; Pinto Gomes, C.J.; Spampinato, G.; Musarella, C.M. Research and management of thermophilic cork forests in the central-south of the Iberian Peninsula. Plant Biosyst. 2024, 158, 942–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leotta, L.; Toscano, S.; Romano, D. Which Plant Species for Green Roofs in the Mediterranean Environment? Plants 2023, 12, 3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellini, A.; Bartoli, F.; Kumbaric, A.; Casalini, R.; Caneva, G. Evaluation of Mediterranean perennials for extensive green roofs in water-limited regions: A two-year experiment. Ecol. Eng. 2024, 209, 107399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musarella, C.M. Solanum torvum Sw. (Solanaceae): A new alien species for Europe. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2020, 67, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musarella, C.M.; Sciandrello, S.; Domina, G. Competition between alien and native species in xerothermic Steno-Mediterranean grasslands: Cenchrus setaceus and Hyparrhenia hirta in Sicily and southern Italy. Vegetos 2024, 38, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive, H. Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora. Off. J. Eur. Communities 1992, 206, 7–50. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano, C.; Guarino, R.; Brenneisen, S. A plant sociological approach for extensive green roofs in Mediterranean areas. In Proceedings of the 11th Annual Green Roof & Wall Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 23–26 October 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, F.; De Masi, R.F.; Mastellone, M.; Ruggiero, S.; Vanoli, G.P. Green walls, a critical review: Knowledge gaps, design parameters, thermal performances and multi-criteria design approaches. Energies 2020, 13, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoenkit, S.; Yiemwattana, S. Role of specific plant characteristics on thermal and carbon sequestration properties of living walls in tropical climate. Build. Environ. 2017, 115, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottelé, M.; van Bohemen, H.D.; Fraaij, A.L. Quantifying the deposition of particulate matter on climber vegetation on living walls. Ecol. Eng. 2010, 36, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, G.; Rincón, L.; Vila, A.; González, J.M.; Cabeza, L.F. Behaviour of green facades in Mediterranean Continental climate. Energy Convers. Manag. 2011, 52, 1861–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoenkit, S.; Yiemwattana, S. The performance of outdoor plants in living walls under hot and humid conditions. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 17, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunnett, N.; Kingsbury, N. Planting Green Roofs and Living Walls; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnan, M.; Kenzhegulova, I.; Eloffy, M.; Ibrahim, W.; Zevenbergen, C.; Pathirana, A. Development of context specific sustainability criteria for selection of plant species for green urban infrastructure: The case of Singapore. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 20, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthon, K.; Thomas, F.; Bekessy, S. The role of ‘nativeness’ in urban greening to support animal biodiversity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 205, 103959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignatti, S.; Guarino, R.; La Rosa, M. Flora d’Italia, 2nd ed.; Edagricole–Edizioni Agricole di New Business Media srl: Milano, Italy, 2017; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Pignatti, S.; Guarino, R.; La Rosa, M. Flora d’Italia, 2nd ed.; Edagricole–Edizioni Agricole di New Business Media srl: Milano, Italy, 2017; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Pignatti, S.; Guarino, R.; La Rosa, M. Flora d’Italia, 2nd ed.; Edagricole–Edizioni Agricole di New Business Media srl: Milano, Italy, 2018; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Pignatti, S.; Guarino, R.; La Rosa, M. Flora d’Italia, 2nd ed.; Edagricole–Edizioni Agricole di New Business Media srl: Milano, Italy, 2019; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaresi, S.; Biondi, E.; Casavecchia, S. Bioclimates of Italy. J. Maps 2017, 13, 955–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raunkiaer, C. The Life Forms of Plants and Statistical Plant Geography; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Escudero, A. Community patterns on exposed cliffs in a Mediterranean calcareous mountain. Vegetatio 1996, 125, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellenberg, H. Indicator values of vascular plants in Central Europe. In Scripta Geobot; Verlag Erich Goltze KG: Gottingen, Germany, 1974; Volume 9, pp. 1–97. [Google Scholar]

- Lionello, P.; Malanotte-Rizzoli, P.; Boscolo, R.; Alpert, P.; Artale, V.; Li, L.; Xoplaki, E. The Mediterranean climate: An overview of the main characteristics and issues. Dev. Environ. Earth Sci. 2006, 4, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, E.; Blasi, C.; Burrascano, S.; Casavecchia, S.; Copiz, R.; Del Vico, E.; Galdenzi, D.; Gigante, D.; Lasen, C.; Spampinato, G.; et al. Manuale Italiano di Interpretazione Degli Habitat Della Direttiva 92/43/CEE (Italian Interpretation Manual of the 92/43/EEC Directive Habitats). 2009. Available online: http://vnr.unipg.it/habitat/index.jsp (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Biondi, E.; Blasi, C.; Burrascano, S.; Casavecchia, S.; Copiz, R.; Del Vico, E.; Galdenzi, D.; Gigante, D.; Lasen, C.; Spampinato, G.; et al. Diagnosis and syntaxonomic interpretation of Annex I Habitats (Dir. 92/43/EEC) in Italy at the alliance level. Plant Sociol. 2012, 49, 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portal to the Flora of Italy. Available online: http://dryades.units.it/floritaly (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Kabisch, N.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Pauleit, S.; Naumann, S.; Davis, M.; Artmann, M.; Haase, D.; Knapp, S.; Korn, H.; Stadler, J.; et al. Nature-based solutions to climate change mitigation and adaptation in urban areas: Perspectives on indicators, knowledge gaps, barriers, and opportunities for action. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 39. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26270403 (accessed on 15 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Wei, S.; Lai, P.Y.; Chu, L.M. Effect of plant traits and substrate moisture on the thermal performance of different plant species in vertical greenery systems. Build. Environ. 2020, 175, 106815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musarella, C.M.; Mendoza-Fernández, A.J.; Mota, J.F.; Alessandrini, A.; Bacchetta, G.; Brullo, S.; Caldarella, O.; Ciaschetti, G.; Conti, F.; Di Martino, L.; et al. Checklist of gypsophilous vascular flora in Italy. PhytoKeys 2018, 103, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Threlfall, C.G.; Walker, K.; Williams, N.S.; Hahs, A.K.; Mata, L.; Stork, N.; Livesley, S.J. The conservation value of urban green space habitats for Australian native bee communities. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 187, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghardt, K.T.; Tallamy, D.W.; Gregory Shriver, W. Impact of native plants on bird and butterfly biodiversity in suburban landscapes. Conserv. Biol. 2009, 23, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikin, K.; Knight, E.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Fischer, J.; Manning, A.D. The influence of native versus exotic streetscape vegetation on the spatial distribution of birds in suburbs and reserves. Divers. Distrib. 2013, 19, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, L.; Di Musciano, M.; Sabatini, F.M.; Chiarucci, A.; Zannini, P.; Gatti, R.C.; Hoffmann, S. A multitaxonomic assessment of Natura 2000 effectiveness across European biogeographic regions. Conserv. Biol. 2024, 38, e14212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochner, S.C.; Beck, I.; Behrendt, H.; Traidl-Hoffmann, C.; Menzel, A. Effects of extreme spring temperatures on urban phenology and pollen production: A case study in Munich and Ingolstadt. Clim. Res. 2011, 49, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetschni, J.; Fritsch, M.; Jochner-Oette, S. How does pollen production of allergenic species differ between urban and rural environments? Int. J. Biometeorol. 2023, 67, 1839–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahs, A.K.; Mc Donnell, M.J. Selecting independent measures to quantify Melbourne’s urban–rural gradient. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 78, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahanayake, K.C.; Chow, C.L. Moisture Content, Ignitability, and Fire Risk of Vegetation in Vertical Greenery Systems. Fire Ecol. 2018, 14, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, S.; Bajocco, S.; Salvati, L.; Camarretta, N.; Dupuy, J.-L.; Xanthopoulos, G.; Guijarro, M.; Madrigal, J.; Hernando, C.; Corona, P. Characterizing potential wildland fire fuel in live vegetation in the Mediterranean region. Ann. For. Sci. 2017, 74, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, D. The NBS Guide to Facade Greening: Part Three. The NBS. 2015. Available online: https://www.thenbs.com/knowledge/the-nbs-guide-to-facade-greening-part-three (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Mostafavi, M.; Doherty, G. (Eds.) Ecological Urbanism; Lars Müller Publishers: Baden, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zanin, G.M.; Muwafu, S.P.; Costa, M.M. Nature-based solutions for coastal risk management in the Mediterranean basin: A literature review. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 356, 356120667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patti, M. Conservation and Valorization of Two Endemic Calabrian Species Used as Food Within the Graecanic Area (Southern-Italy) Through Domestication Trials. In Networks, Markets & People; Calabrò, F., Madureira, L., Morabito, F.C., Piñeira Mantiñán, M.J., Eds.; NMP 2024; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castroviejo, S. (Ed.) Flora Ibérica: Plantas Vasculares de la Península Ibérica e Islas Baleares; Editorial CSIC-CSIC Press: Madrid, Spain, 1986; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

| Ellemberg–Pignatti Indicator | Original Range | Considered Range |

|---|---|---|

| L | 0 ≤ x ≤ 12 | 7 ≤ x ≤ 12 |

| T | 0 ≤ x ≤ 12 | 7 ≤ x ≤ 12 |

| K | 0 ≤ x ≤ 9 | 2 ≤ x ≤ 7 |

| U | 0 ≤ x ≤ 12 | 0 ≤ x ≤ 5 |

| N | 0 ≤ x ≤ 9 | 0 ≤ x ≤ 5 |

| Selected Habitats | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Habitat Macro-Category | Habitat Type | ||

| Code | Name | Code | Name |

| 12 | Vegetated sea cliffs and gravel beaches | 1240 | Vegetated sea cliffs of the Mediterranean coasts with endemic Limonium spp. |

| 53 | Thermo-Mediterranean and pre-steppe scrublands | 5320 | Low formations of Euphorbia close to cliffs |

| 5330 | Thermo-Mediterranean and pre-desert scrub | ||

| 54 | Phryganas | 5410 | West Mediterranean clifftop phryganas (Astragalo-Plantaginetum subulatae) |

| 5420 | Sarcopoterium spinosum phryganas | ||

| 5430 | Endemic phryganas of the Euphorbio-Verbascion | ||

| 62 | Semi-natural dry grassland formations and shrub-covered facies | 6210 (*) | Semi-natural dry grasslands and scrubland facies on calcareous substrates (Festuco-Brometalia) (* important orchid sites) |

| 6220 * | Pseudo-steppe with grasses and annuals of the Thero-Brachypodietea | ||

| 62A0 | Eastern sub-mediterranean dry grasslands (Scorzoneretalia villosae) | ||

| 82 | Rocky slopes with chasmophytic vegetation | 8210 | Calcareous rocky slopes with chasmophytic vegetation |

| 8220 | Siliceous rocky slopes with chasmophytic vegetation | ||

| 8230 | Siliceous rock with pioneer vegetation of the Sedo-Scleranthion or of the Sedo albi-Veronicion dillenii | ||

| 8240 * | Limestone pavements | ||

| 93 | Mediterranean sclerophyllous forests | 9320 | Olea and Ceratonia forests |

| 9340 | Quercus ilex and Quercus rotundifolia forests | ||

| 9330 | Quercus suber forests | ||

| N° | Family | Number of Taxa |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acanthaceae | 1 |

| 2 | Amaranthaceae | 2 |

| 3 | Apiaceae | 14 |

| 4 | Asparagaceae | 3 |

| 5 | Aspleniaceae | 1 |

| 6 | Asteraceae | 59 |

| 7 | Boraginaceae | 7 |

| 8 | Brassicaceae | 29 |

| 9 | Campanulaceae | 7 |

| 10 | Capparaceae | 2 |

| 11 | Caprifoliaceae | 2 |

| 12 | Caryophyllaceae | 27 |

| 13 | Cistaceae | 15 |

| 14 | Convolvulaceae | 3 |

| 15 | Crassulaceae | 6 |

| 16 | Cystopteridaceae | 1 |

| 17 | Dipsacaceae | 4 |

| 18 | Ephedraceae | 2 |

| 19 | Ericaceae | 2 |

| 20 | Euphorbiaceae | 8 |

| 21 | Fabaceae | 36 |

| 22 | Geraniaceae | 1 |

| 23 | Hypericaceae | 3 |

| 24 | Lamiaceae | 29 |

| 25 | Linaceae | 3 |

| 26 | Malvaceae | 1 |

| 27 | Plantaginaceae | 12 |

| 28 | Plumbaginaceae | 20 |

| 29 | Poaceae | 19 |

| 30 | Polygalaceae | 5 |

| 31 | Polygonaceae | 3 |

| 32 | Primulaceae | 3 |

| 33 | Pteridaceae | 1 |

| 34 | Ranunculaceae | 1 |

| 35 | Rosaceae | 2 |

| 36 | Rubiaceae | 12 |

| 37 | Rutaceae | 3 |

| 38 | Scrophulariaceae | 8 |

| 39 | Solanaceae | 1 |

| 40 | Tamaricaceae | 1 |

| 41 | Thymelaeaceae | 2 |

| 42 | Urticaceae | 1 |

| 43 | Valerianaceae | 4 |

| 44 | Violaceae | 2 |

| TOT | 44 | 368 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Patti, M.; Musarella, C.M.; Spampinato, G. A Habitat-Template Approach to Green Wall Design in Mediterranean Cities. Buildings 2025, 15, 2557. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15142557

Patti M, Musarella CM, Spampinato G. A Habitat-Template Approach to Green Wall Design in Mediterranean Cities. Buildings. 2025; 15(14):2557. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15142557

Chicago/Turabian StylePatti, Miriam, Carmelo Maria Musarella, and Giovanni Spampinato. 2025. "A Habitat-Template Approach to Green Wall Design in Mediterranean Cities" Buildings 15, no. 14: 2557. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15142557

APA StylePatti, M., Musarella, C. M., & Spampinato, G. (2025). A Habitat-Template Approach to Green Wall Design in Mediterranean Cities. Buildings, 15(14), 2557. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15142557