2. Materials and Methods

In the evolving landscape of the architectural field, the formulation of contemporary research methodologies has become increasingly vital—not only to respond to complex design realities but also to engage critically with theory, discourse, and interdisciplinarity. As architectural issues become more entangled with ecological, technological, and socio-political dynamics, research frameworks must adapt to capture this complexity. Against this backdrop, the present study seeks to develop a methodologically robust and conceptually responsive approach that reflects the shifting contours of architectural inquiry. To this end, the research has been structured around a clearly defined aim, guiding research questions, and a multi-layered strategy, each of which is detailed in the following sections.

2.1. Aim and Research Questions

The primary aim of this study is to systematically investigate the application of relational thinking within the field of architecture by analyzing the existing literature, identifying both commonalities and divergences across studies, organizing these findings into thematic categories, and mapping the emerging trends of the 21st century. The selected articles were systematically collected, coded, associated, and evaluated using a set of developed datasets.

The research is guided by two central questions:

The question seeks to capture the diverse ways in which relational thinking is framed and discussed within contemporary architectural discourse.

The question focuses on uncovering the key themes, sub-concepts, similarities, and differences that emerge from the selected body of literature through detailed thematic analysis.

These questions provide a comprehensive understanding of how relational thinking is currently theorized and operationalized within architectural scholarship, and for mapping the intellectual trajectories and thematic contours that structure contemporary discourse. Building on these guiding questions, the subsequent section details the research strategy and data selection procedures that structure the analytical framework of this study.

2.2. Research Strategy and Process

This study investigates the presence and content of relational thinking within architectural discourse in the 21st century by adopting an epistemologically grounded, post-positivist, and systematically structured research framework. While acknowledging the impossibility of fully objective or value-free knowledge, the post-positivist approach adopted here emphasizes methodological rigor, systematic inquiry, and critical interpretation to generate well-supported and context-sensitive insights [

33]. The motivation for this research stems particularly from the lack of comprehensive studies that examine contemporary interpretations of relational thinking—one of the dominant intellectual paradigms of the information age—within the field of architecture.

The qualitative research paradigm underpinning this study employs interpretive strategies to systematically interrogate the ways in which relational thinking is theorized, articulated, and operationalized within contemporary architectural discourse. Rather than seeking to generate generalizable causal claims or statistical correlations, the research focuses on producing a rich, nuanced understanding of the evolving discourse by analyzing texts and contents and curating thematic patterns across a defined body of literature.

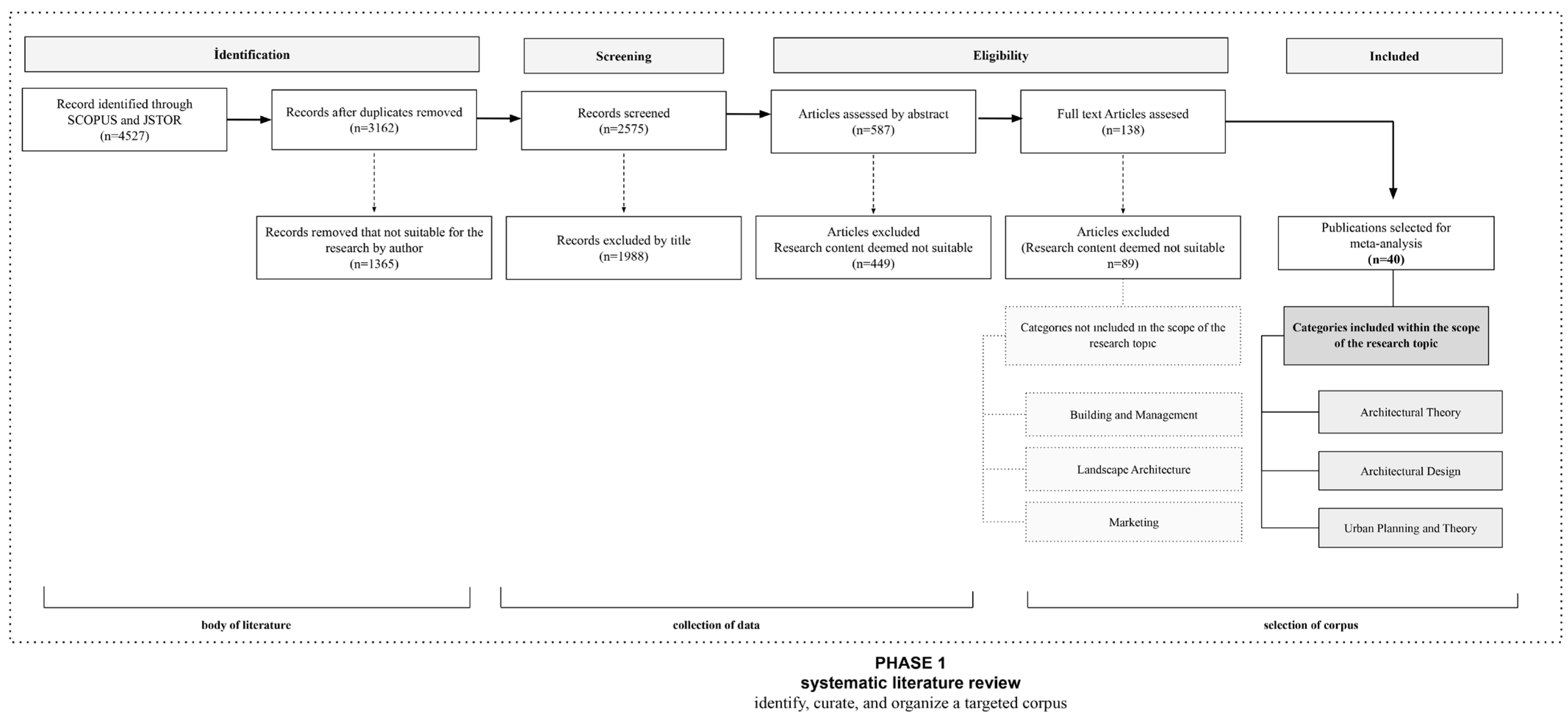

The research methodology consists of three interrelated phases (

Figure 1). In the first phase, a systematic literature review was conducted to identify, curate, and organize a targeted corpus of scholarly publications that explicitly engage with relational thinking within the field of architecture. While systematic in its structure, this phase did not involve quantitative meta-analysis but rather functioned as a rigorous qualitative sampling and inclusion process, governed by clear criteria for source selection and relevance. In the second phase, a thematic analysis was performed on the selected texts. This analytical approach involved in-depth reading, iterative coding, the categorization of recurring concepts, and the identification of emerging themes within the literature. Thematic analysis, as a flexible and widely used qualitative method, allows for the systematic extraction of underlying patterns of meaning while remaining sensitive to the complexity, diversity, and context-specificity of scholarly discourse [

34]. In the final phase, an interpretive synthesis was conducted to integrate and refine the findings emerging from the thematic analysis. This stage aimed to establish conceptual linkages between identified themes, allowing for a comprehensive interpretation of how relational thinking operates across diverse strands of contemporary architectural discourse. Through this iterative process, thematic clusters were systematically connected, patterns of convergence and divergence were identified, and overarching conceptual structures were constructed.

By integrating systematic review procedures with content analysis and interpretive thematic analysis grounded in post-positivist epistemology, this research strategy provides both comprehensive coverage of the existing literature and critical depth in capturing the nuanced articulations of relational thinking within architectural discourse.

Phase 1: Data collection and selection criteria

The systematic literature review conducted for dataset construction systematically examined and extracted data from the existing body of scholarly literature related to the clearly defined research questions. The objective of this process was to update and synthesize accumulated knowledge, critically evaluate existing studies, and identify emerging research trajectories within the field. To ensure methodological rigor and transparency, the review followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) protocol, which proceeds through a four-stage process. Data collection was carried out using two major academic databases: Journal Storage (JSTOR) and SCOPUS. While SCOPUS offers a comprehensive bibliographic dataset with standardized abstracts and keyword indexing, JSTOR presents certain limitations, particularly the absence of abstracts and keywords in many of its entries. One of the unique contributions of this study lies in systematically generating and organizing a dataset on relational approaches within the JSTOR database, where no previously structured data pool existed.

- (a)

Systematic search and initial screening

Searches within these databases were performed across multiple fields, including “title”, “abstract”, “keyword”, and “full text”. In line with the study’s focus on contemporary developments in relational thinking, the temporal scope was restricted to publications from 2000 onward. Since the research was initiated in 2024, the search included all eligible publications up to the end of 2024. Keyword searches employed terms such as ‘relational’, ‘relationality’, ‘relational approach’, ‘relational thinking’, and ‘architecture’, which were combined in various configurations across both databases. To be included in the final dataset, publications were required to meet the eligibility criteria presented in

Table 2.

The flow of this systematic review, conducted following the PRISMA protocol, is illustrated in

Figure 2. The initial keyword searches yielded a total of 4527 records. After the removal of duplicate entries, 3162 publications that were determined to be unrelated to the core focus on relational thinking—including studies in architectural history, archeology, art history, engineering, and other adjacent fields—were excluded through database filtering. The remaining 2575 records were screened based on their titles, resulting in 587 articles selected for abstract review.

- (b)

Abstract review and selection

Following abstract screening, the 587 articles were organized into five categories: Building and Management, Landscape Architecture, Marketing, Architectural Theory, Urban Planning and Theory, and Architectural Design. Articles falling under Building and Management, Landscape Architecture, and Marketing were excluded due to their misalignment with the study’s research focus. Subsequently, 138 articles categorized under Architectural Theory, Architectural Design, and Urban Planning and Theory were subjected to full-text review.

- (c)

Justification of research material’s size and scope

Following a full-text review of 138 identified articles, 40 were selected for inclusion in the content analysis dataset, based on their alignment with at least one of the selection qualities outlined below:

Explicitly or implicitly engaging with relational thinking.

Demonstrating interdisciplinary or cross-theoretical potential.

Providing a theoretical framework that aligns with or critiques relational paradigms.

Employing relational concepts in the analysis of spatial, social, or environmental phenomena.

Referencing key thinkers or texts associated with relational theory (e.g., Latour, Deleuze & Guattari, Lefebvre).

Demonstrating methodological innovation in engaging with networked, emergent, or non-linear systems.

Critically interrogating conventional architectural binaries (e.g., object/field, form/process, material/immaterial).

Addressing architecture’s entanglement with broader socio-technical or ecological systems.

Contributing to emerging debates in posthumanism, systems thinking, or assemblage theory within architecture.

Highlighting multi-scalar or trans-scalar relational dynamics.

The final selection of 40 articles balances breadth and depth, enabling comprehensive content analysis while maintaining analytical manageability, as presented in

Table 3. A smaller dataset would have limited the diversity of perspectives, while a significantly larger corpus could have compromised methodological coherence and focus. The data source for each article is indicated using a symbolic notation: ‘J’ for JSTOR and ‘S’ for SCOPUS. For each article, the chart records key bibliographic information, including database and source, journal name, author(s), and year of publication.

The selected articles represent 16 distinct academic journals, with Log (8 articles), Design Issues (6 articles), and Journal of Architectural Education (1984–) (5 articles) being the most frequently represented. These journals span architecture’s theoretical, technical, and interdisciplinary intersections, including urban studies, design philosophy, sustainability, and computational design. Many of the studies exhibit strong interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary tendencies, integrating insights from philosophy, sociology, systems theory, environmental studies, and digital design. This scope ensures that the dataset captures not only diverse articulations of relational thinking but also its entanglement with contemporary architectural challenges and epistemologies.

Phase 2: Content analyses, iterative coding process, and thematic development

Following the systematic selection of 40 articles, a detailed qualitative content analysis was conducted in two main stages to ensure reproducibility, rigor, and transparency:

- (a)

Initial coding and sub-cluster development

Iterative close reading: Two independent coders (the corresponding author and the advisor author) conducted an iterative close reading of all 40 articles. A pilot coding phase was implemented on a randomly selected subset of 8 articles to develop an initial codebook. During this phase, the team identified recurrent keywords, conceptual expressions, and relational constructs.

Inductive–conceptual hybrid coding: Initial themes were generated inductively, allowing novel categories to emerge naturally from the data. At the same time, a theory-informed deductive check was performed to ensure alignment with the study’s theoretical framework and research questions. Codes were refined into 29 sub-clusters (e.g., “design actors”, “human–machine interactions”).

Inter-coder reliability (ICR): To ensure analytical rigor and consistency, the coding process followed a cyclical and iterative structure. Codes and emerging patterns were repeatedly reviewed, refined, and re-contextualized, considering ongoing readings and interpretive feedback. Rather than relying on frequency counts, the emphasis was placed on the depth, coherence, and relevance of conceptual associations. This approach allowed for a nuanced understanding of the material while maintaining transparency and methodological clarity in theme construction.

- (b)

Thematic clustering

Full coding of the remaining articles: Using the refined codebook, both coders independently coded the remaining 32 articles and discussed any emerging codes or ambiguities.

Clustering into themes: All codes were then categorized into five thematic clusters based on conceptual similarity, content, and theoretical relevance.

Validation and synthesis: Themes were cross-validated by both coders. Instances of disagreement were resolved using a CBP (consensus-building protocol). This ensured that thematic boundaries were both empirically grounded and conceptually robust. The validated themes formed the basis for the interpretive synthesis carried out in Phase 3.

Phase 3: Interpretive synthesis

In the final phase of the research, a critical interpretive synthesis was conducted to examine the conceptual relationships between the thematic clusters established in the previous stage. Rather than treating the themes as fixed or self-contained categories, this phase focused on exploring their intersections, overlaps, and degrees of conceptual alignment within the broader discourse of relational thinking in architecture. To guide this interpretive process, the thematic connections were assessed through qualitative correlation levels—categorized as weak, medium, or strong—based on the extent to which individual themes were conceptually intertwined or recurrently co-articulated across the selected literature. These classifications were not derived from quantitative metrics, but from critical reflection, close reading, and iterative interpretation of the coded material. The interpretive synthesis phase enabled a more layered understanding of the discourse, highlighting both areas of strong convergence and domains where conceptual tensions or gaps persist. In doing so, the analysis goes beyond thematic organization to reveal the dynamic interplay among ideas and to map the evolving contours of relational thinking within architectural theory and research.

3. Results

3.1. Thematic Clusters

In architectural research, organizing scholarly articles into thematic clusters is essential for synthesizing knowledge and providing deeper insights into the field’s multifaceted nature. The clusters established in this study reflect critical domains of contemporary architectural discourse: Theoretical Framework and Foundations, Design Methodologies and Practices, Sustainability and Ecology, Social and Cultural Contexts, and Technological Integration (

Table 4). Each cluster title was meticulously selected to capture the core focus of the articles within, ensuring that the full range of interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary approaches in architectural research are represented. This structured synthesis allows for a more comprehensive understanding of how the dynamics of relationality shape both architectural theory and practice.

TC1: Theoretical Framework and Foundations

The cluster “Theoretical Framework and Foundations” gathers studies that explore the philosophical premises and epistemological foundations of architectural thinking through a relational lens. At the heart of these contributions lies a reexamination of the longstanding theory–practice divide. Rather than treating these realms as oppositional, the selected literature positions architecture as a field where conceptual frameworks actively shape and are shaped by design processes [

23,

40,

41,

43,

50,

52,

68,

70,

71,

72,

73].

A recurring focus within this cluster is the notion of architectural discourse as a site of negotiation, where meaning is not imposed from above but produced through dynamic exchanges between philosophical traditions, disciplinary norms, and spatial practices. Studies dealing with the dialog and division between theory and practice interrogate how architectural thought evolves through this mutual feedback loop, rejecting static models of form and instead proposing a process-oriented ontology grounded in conceptual relations [

54,

58,

59,

61]. The philosophical foundations of architecture feature prominently, drawing from thinkers such as Heidegger, Deleuze, and Spinoza, as well as architectural theorists like Eisenman, Koolhaas, Fuller, Rossi, and Allen [

23,

53,

54,

59,

73]. These contributions frame architectural knowledge as contingent and situated, shaped by historical, intellectual, and material assemblages rather than universal truths. This orientation gives rise to a relational understanding of space—not as a passive container but as an active outcome of intersecting epistemic and material forces [

63,

64,

67]. Relationality is also explored through the lens of field theory, where architecture is seen not as a fixed entity but as embedded within broader intellectual, cultural, and social networks. This framework allows for a rethinking of architectural agency, challenging the notion of the architect as a solitary author and instead emphasizing distributed authorship across conceptual, institutional, and societal domains [

58,

70,

72].

TC2: Design Methodologies and Practices

The cluster “Design Methodologies and Practices” brings together studies that explore how relational thinking redefines architectural design—not as a linear, author-driven act but as a distributed, context-responsive process shaped by interactions across scales and systems. Central to this body of literature is the notion that design operates within a network of actors, environments, and epistemic formations, where outcomes emerge through iterative negotiation rather than isolated authorship [

23,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

65]. Contributions in this cluster emphasize a wide range of sub-clusters that reflect this shift: design processes, design thinking, interaction-based approaches, and urban-building dialogs are reframed through relational logics that foreground connectivity, fluidity, and contextual contingency [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

55,

69,

71]. Several studies deconstruct the “black box” perception of design by interrogating its internal relational mechanics—particularly how spatial, social, and material forces co-constitute architectural form. These investigations illustrate how design actors (including users, clients, and environments) participate in continuous feedback loops that shape not only outcomes but also the very criteria of architectural success [

38,

47,

57,

72]. The educational dimension of design forms another prominent sub-cluster. Here, relational thinking informs alternative pedagogies—studio-based models that incorporate design experience, participatory learning, and contextually embedded critique. These pedagogies aim to cultivate a reflexive awareness of how knowledge is generated through situated practice rather than abstract universality [

48,

51,

68]. Similarly, attention to the designer’s perspective and embodied cognition challenges the separation of intellectual and affective dimensions in the design process, recognizing instead how perception, movement, and intuition interact with socio-material environments in design decision-making [

46,

48,

55]. This cluster also highlights the design culture’s entanglement with transdisciplinary influences, including insights from philosophy, sociology, and anthropology [

23,

37,

49,

56,

66]. Such studies trace how architectural production increasingly reflects hybrid logics and methodological pluralism, inviting collaboration across domains and decentering the notion of architecture as an enclosed field. The inter/cross/transdisciplinary design discourse strengthens this position, reinforcing design as a process that traverses disciplinary, spatial, and material thresholds. Importantly, relational thinking within this cluster reframes the urban design dialog—moving away from static typologies toward more fluid negotiations between built form and social life. Urban space is read not as a container for activity but as a co-produced field where interactions between people, infrastructures, and temporal rhythms shape architectural meaning.

TC3: Sustainability and Ecological Design

This cluster brings together studies that explore the evolving relationship between architecture, sustainability, and ecology through the lens of relational thinking. Moving beyond instrumental definitions of sustainability—as merely energy efficiency or resource conservation—these contributions reframe ecological design as an ontological and epistemological shift in how the built environment is conceived, produced, and inhabited [

36,

43,

49,

51,

61,

62,

64,

66,

72].

Central to this cluster is the challenge posed to entrenched modernist binaries such as the building–nature division, which have historically separated the natural and constructed worlds. Through environmental discourse grounded in relational ontology, several studies advance the view that architecture is not an external intervention into nature but rather a co-emergent participant within dynamic ecological assemblages. Here, built forms, ecosystems, and social practices are conceptualized as mutually constitutive, operating within interdependent webs of materiality, energy exchange, and temporal rhythms [

61,

64]. Many of the works in this cluster employ networks and systems theory to articulate these interrelations, reconfiguring the environment as a complex system of reciprocal flows. In this view, architectural sustainability is less about minimizing impact and more about attuning to the relational conditions that shape environmental transformation [

36,

43,

49,

51,

62]. This systems-based perspective reframes sustainability as a situated practice of ecological responsiveness. A significant sub-cluster engages with vernacular architecture and context-based approaches, highlighting the epistemic value of local ecological knowledge, material traditions, and spatial practices that emerge from specific climatic and cultural contexts [

36,

51,

62,

66]. These studies argue that sustainability cannot be universally applied; it must be relationally grounded in the lived, historic, and biophysical conditions of place. Relational thinking thus underscores the inseparability of ecological design from context, foregrounding adaptation over standardization. Recent contributions also push the boundaries of ecological design through the integration of multispecies agencies, biologically active materials, and living systems. For instance, the use of mycelium-based materials for soil remediation exemplifies how architectural design can participate in ecological repair, not only symbolically but materially. These approaches envision the built environment as a biocultural infrastructure where human and non-human agencies collaborate in shaping more inclusive and resilient futures [

72].

TC4: Social and Cultural Aspects

This cluster explores the intricate relationship between architecture and the socio-cultural dynamics that shape, and are shaped by, the built environment. Through the lens of relational thinking, the built environment is not perceived as a static backdrop but as an evolving, interactive field where collective experience, cultural practices, and spatial configurations continuously co-emerge [

23,

38,

41,

42,

44,

45,

47,

57,

58,

63,

65,

70,

71,

72,

73]. Central to this cluster is the recognition that architecture mediates both human–human and human–non-human associations, positioning buildings as relational interfaces rather than fixed formal entities. These studies challenge binary subject–object distinctions by foregrounding architecture as a dynamic network of interactions involving multiple agents—including architects, users, communities, institutions, and even non-human actors such as technologies and ecosystems [

38,

41,

47,

57,

65,

71]. In this regard, buildings are conceptualized not as isolated objects but as relational nodes embedded within broader social and material ecologies.

A prominent theme emerging from this cluster is the actor–network relationality that underpins architectural production and occupation. Drawing on frameworks such as actor–network theory and relational sociology, these studies illustrate how architectural meaning and performance are co-produced through distributed agency and interdependent systems. Architecture, in this view, becomes a site of negotiation where social roles, power structures, and symbolic meanings are enacted and contested. The social dimensions of architecture are further examined through the lens of everyday activities, showing how space is shaped by habitual practices, informal interactions, and sensory experiences that often elude quantification. This attention to both measurable and immeasurable factors enriches our understanding of how spatial environment mediates identity formation, cultural continuity, and social inclusion or exclusion. Moreover, cultural systems—such as national identity, religious norms, or collective memory—are shown to inscribe themselves into spatial practices, contributing to the architectural shaping of public life and socio-political discourse [

50,

63,

73]. Cities, in particular, are conceptualized as relational fields, where architecture plays an active role in structuring communication, enabling participation, or reinforcing hierarchies [

41,

42,

50,

70]. The influence of social context becomes especially evident in discussions on gentrification, place attachment, and the politics of visibility.

TC5: Technological Integration

This cluster investigates the deepening entanglement between technological systems and architectural thought, focusing on how emerging tools and infrastructures actively shape architectural design, production, and interpretation [

39,

42,

72]. Rather than viewing technology as an external or purely instrumental layer, the studies grouped here approach technological integration as a constitutive element of architectural relational networks—a force that both mediates and transforms spatial experience.

A key sub-cluster within Technological Integration is human–machine interaction, where the evolving role of artificial intelligence, machine learning, and computational platforms prompts a reevaluation of design agency. These studies examine how collaborative processes between human and non-human agents destabilize anthropocentric and author-centered design models, giving rise to alternative ontologies in which architecture becomes a product of co-generative processes [

39].

Equally important are studies on design and building tools, which highlight how new digital platforms, fabrication techniques, and interface systems influence not only how architecture is made but also how it is conceived. From agent-based planning to AI-assisted housing platforms and multispecies design algorithms, architectural tools are no longer passive extensions of human intention but are integrated co-authors in shaping spatial form. Notable experimental projects—such as Diffusive Habitats, Modulated Subtopia, and More Than Human—demonstrate how tools grounded in data-driven logic and parametric responsiveness mediate new forms of adaptive design practice. Another recurring thread involves computer-based systems and their impact on architectural workflows. These contributions critically assess how digital environments restructure the continuum from design conception to production and occupation, emphasizing the recursive influence of computational feedback on decision-making and spatial articulation [

42,

72]. Importantly, these systems are not merely enablers of technical efficiency but reframe the temporal and material logic of architecture itself.

The final sub-cluster—complex networks—situates technology within broader relational ecologies that encompass social, environmental, and informational flows. Drawing on systems theory and complexity science, these studies present architecture as a multi-agent, distributed system in which technological, ecological, and human variables continuously interact [

39].

The thematic clusters and sub-clusters—visualized in

Figure 3 through a chord diagram—represent the methodological and discursive articulations of relational thinking within architectural theory. While each cluster delineates a distinct domain of inquiry, they are not epistemologically isolated. Instead, they intersect and overlap, forming a network of interrelated ideas that collectively shape the evolving contours of the discipline. These thematic groupings reflect the multiplicity of lenses through which relationality is examined—from philosophical foundations to socio-technical systems—emphasizing their dialogical and co-constitutive nature. The following section offers an interpretive synthesis of these clusters, with a focus on the underlying tensions, convergences, and conceptual interdependencies that emerge at their intersections.

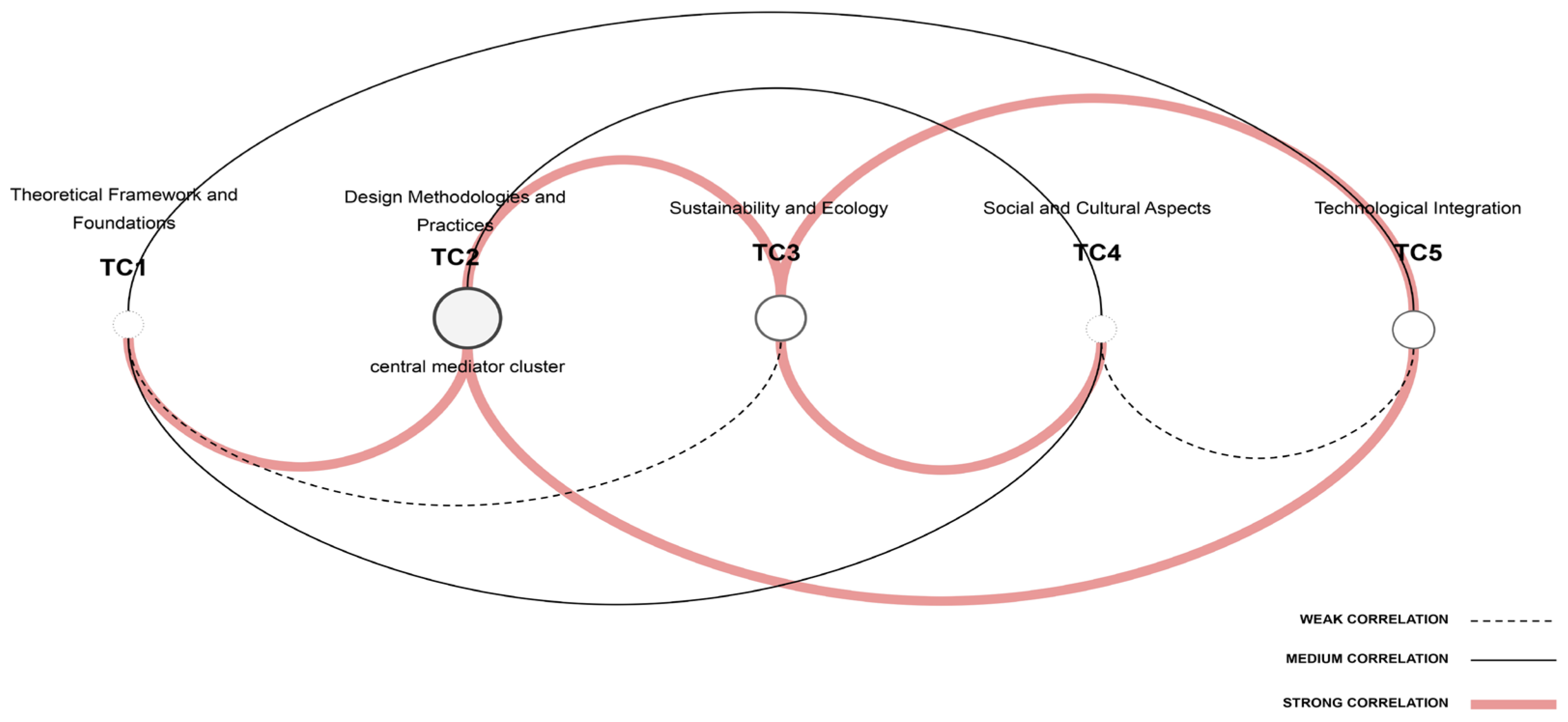

3.2. Interpretive Synthesis of the Clusters

The five thematic clusters outlined in this study—Theoretical Framework and Foundations (TC1), Design Methodologies and Practices (TC2), Sustainability and Ecology (TC3), Social and Cultural Contexts (TC4), and Technological Integration (TC5)—collectively portray relational thinking in architecture not as a thematic preference but as a transformative epistemic paradigm (

Figure 4). These clusters, while individually significant, operate synergistically across ontological, methodological, technological, ecological, and socio-political terrains. Their interplay reveals a multi-dimensional framework where architecture is no longer the product of linear reasoning or singular agency but an evolving negotiation across systems, contexts, and actors.

At the core of this synthesis lies the active and recursive interplay between theoretical foundations (TC1) and design methodologies (TC2). This connection facilitates the transition from abstract ontological principles—drawn from process philosophy, new materialism, and poststructuralism—into concrete design practices that prioritize co-creation, agency distribution, and contextual responsiveness. Here, design becomes both a reflection and a testbed for philosophical propositions, demonstrating how abstract ideas shape and are reshaped through design’s iterative realities. Building on this foundational bridge, the convergence of TC2 with TC4 and TC5 marks a triadic axis where design functions as a nexus for integrating social engagement and technological innovation. Computational design tools, AI-driven systems, and digital fabrication techniques are not merely instrumental; they become co-agents in processes of spatial negotiation, responsive environments, and participatory planning. Simultaneously, design’s social dimension infuses these processes with cultural specificity and ethical accountability. This hybrid zone challenges the traditional separation of form and function, reframing design as a multi-layered interface for negotiation among human and non-human actors alike. Moreover, the intersection of TC3 and TC5 introduces a fertile ground for what can be called ecotechnological relationality. Within this framework, smart materials, embedded sensors, and responsive systems are viewed not only as technical advancements but as ecological agents that collaborate with biological systems, local climates, and environmental dynamics. Projects arising at this intersection challenge anthropocentric design assumptions and instead prioritize adaptive, symbiotic systems where built environments respond to and evolve with their ecological contexts. The relationship between TC3 and TC4 deepens this view, illustrating how ecological and cultural systems are interwoven. Community-led sustainability projects, environmental justice architecture, and culturally embedded ecological initiatives exemplify the ethical entanglement of environmental and social design. In these cases, architecture emerges as a site of co-constructed knowledge, where environmental resilience is inseparable from cultural memory and political empowerment. Additionally, TC2, when analyzed in connection with TC1, TC3, TC4, and TC5, functions as a relational integrator—translating theoretical, technological, ecological, and social knowledge into situated, project-based practices. Design methodologies are where abstract thought meets tangible intervention, making architecture a site of continuous knowledge production. This centrality of TC2 is reflected in the design act’s growing role as a multi-agent lab: a place where speculative theory, technological innovation, environmental sensitivity, and socio-cultural narratives converge. The theoretical–technological link (TC1–TC5), while less frequently emphasized in the literature, holds latent potential. Conceptualizing technology as an ontological actor in design opens new territories for theoretical speculation: algorithmic decision-making, non-human agency, and cybernetic ecologies demand philosophical attention. Similarly, the underexplored connection between TC1 and TC4 signals the need for more robust theoretical foundations in socially and culturally driven architectural research—especially in themes such as spatial justice, identity politics, and collective memory. Furthermore, a quadrilateral relational pattern emerges among TC2, TC3, TC4, and TC5. This configuration represents a multi-scalar co-constitution of architecture, where design, technology, ecology, and culture operate not in sequence but simultaneously. A single project may deploy parametric tools (TC5), respond to climate data (TC3), engage marginalized communities (TC4), and be grounded in adaptive, non-linear design methodologies (TC2). Such an architectural approach enacts relational thinking in its fullest sense—not as an abstract framework or isolated methodology but as a dynamic, lived engagement with the material, social, and environmental contingencies that shape design in real time.

Based on all these intersections, three meta-patterns can be identified, as illustrated in

Figure 5:

Polymorphic assemblages: Architecture today is shaped by configurations involving designers, machines, ecological forces, cultural actors, and more—illustrating that knowledge and agency are no longer monopolized by human cognition or disciplinary boundaries.

Iterative synergy: Each cluster influences and is influenced by the others. Theoretical insights drive experimental design, which in turn challenges and expands conceptual frameworks. Technological systems shape ecological strategies, which in turn influence social practices. Architecture becomes an ever-evolving field of reciprocal feedback.

Ethical–ecological–cultural weaving: Architecture is increasingly called upon to mediate between environmental ethics, technological accountability, and social justice. This triadic entanglement forces a rethinking of architectural responsibility—not just as technical performance but as ethical praxis.

Considering the full scope of inter-cluster dynamics, the five clusters establish a dynamic epistemological terrain wherein relational thinking functions not only as an analytical lens but as a generative principle. Architecture is not merely redefined—it is reterritorialized. Form, agency, authorship, and responsibility are no longer fixed constructs but fluid negotiations within multi-agent, interdependent systems. This synthesis provides a conceptual architecture for imagining a future-oriented design ethos—reflexive, interdisciplinary, and deeply responsive to the entangled realities of the 21st century. The thematic clusters identified in this study reveal how relationality permeates contemporary architectural discourse across multiple scales. As illustrated in

Figure 4, each cluster foregrounds a distinct dimension—theoretical, procedural, technological, ecological, social, or practical—yet their interrelations illuminate evolving patterns of convergence, divergence, and hybridization. These linkages suggest that relational thinking is not simply a topical shift but a paradigmatic realignment of architectural epistemology. From this standpoint, a broader inquiry emerges concerning the conceptual and practical implications of the findings—particularly for architectural knowledge production, design methodologies, and the socio-environmental commitments of the discipline.

4. Discussion

Architecture today is situated within an increasingly complex web of relational processes that unfold simultaneously across spatial, social, ecological, technological, and epistemological domains. As Meredith [

55] (p. 173) observes, “All of us are more or less consciously operating within the context(s) of irresolvable relationships unfolding at multiple scales”. The findings of this study demonstrate that relational thinking in architecture reflects a significant epistemological shift away from reductionist, isolationist, and object-centered paradigms. Traditional design models often approach complexity by disaggregating systems into isolated parts, analyzing these parts in opposition or linear causality. Relational thinking, by contrast, prioritizes the constitutive interactions between components, understanding built environments as dynamic systems of nested, interconnected networks. Across the five thematic clusters identified in this research, several core transformations have been observed:

Architecture, traditionally conceived as the manipulation of static forms, is increasingly understood as a field embedded in continuous flux. Relational frameworks emphasize buildings and cities as responsive systems—subject to social, ecological, and technological forces. This dynamic orientation aligns architecture with systems theory but differs in that it does not treat systems as closed or self-referential; instead, systems are open, adaptive, and in constant negotiation with their surroundings. Such a view necessitates an expanded notion of performance—one that includes social adaptability, temporal responsiveness, and ecological resilience. Yet, challenges remain in quantifying such performances or integrating them into prevailing codes and planning systems.

In rejecting the black-box model of design, relational approaches embrace the multiplicity of agents that co-construct architectural outcomes. Design becomes less about authorial intent and more about mediated negotiations—between designers, stakeholders, technologies, materials, and environments. This reframing has substantial implications for pedagogy and professional practice. It encourages participatory studio models and inclusive stakeholder engagement but also demands rethinking intellectual property, authorship, and responsibility. Moreover, it necessitates that designers develop communication and facilitation skills—not traditionally emphasized in architectural education.

Relationality calls for a deeper integration of architecture into its socio-cultural and ecological contexts. It replaces the abstraction of universal design principles with specificity: the histories, cultures, climates, and politics that contour every project. Space is not just occupied but produced and reproduced through relational encounters. This view fosters site-specific, culturally embedded design practices—but it can also complicate replication, scalability, and standardization. Practically, it requires reorienting workflows and tools toward deep site immersion and collaborative inquiry, which may challenge market pressures for speed and efficiency.

One of the most pronounced findings is the collapse of the nature–culture divide. Ecological justice is inseparable from spatial justice. Projects engaging in environmental repair, such as community-driven green infrastructure or regenerative architecture, inherently intersect with socio-political domains. This convergence suggests that sustainability can no longer be approached through technical optimization alone; it must be negotiated through community engagement, cultural recognition, and long-term stewardship. However, integrating these ambitions into mainstream practice may encounter resistance from stakeholders focused on cost-efficiency or short-term deliverables.

While digital tools are often positioned as neutral extensions of design capacity, relational thinking reframes them as active participants in shaping space, behavior, and meaning. Algorithms, sensors, and simulation tools create new feedback loops that challenge traditional hierarchies of decision-making. Yet, this technocentric empowerment must be critically examined. Overreliance on digital environments can obscure material realities, reinforce surveillance dynamics, or prioritize optimization over spatial dignity. A balanced approach must merge computational intelligence with humanistic and ethical scrutiny.

Relational thinking thrives on epistemological fluidity. It draws on philosophy, science, politics, and art—rejecting disciplinary silos. Such breadth opens new territories for inquiry but risks conceptual dilution or methodological vagueness. For relational thinking to meaningfully influence architectural research and education, clearer frameworks are needed to bridge theory and methods, especially in practice-based contexts. This includes new typologies of collaboration, hybrid curricula, and the co-development of shared vocabularies.

The powerful confirmation of relational thinking aligns with events and acts—those spatial practices and design interventions where theory materializes within concrete, lived conditions. These include experimental studios, temporary installations, participatory prototyping, digital-twin simulations, and community co-design processes. In these settings, architecture becomes a medium of dialog rather than a static outcome; its meanings are co-produced in real time through feedback between designers, users, materials, and environments. Such experiments foreground design not as a finished product but as an iterative, adaptive process embedded in evolving contexts.

Emerging from this comprehensive inquiry is the understanding that relational thinking is not merely a theoretical inclination but a transformative epistemic paradigm—one that redefines architecture’s intellectual and operational horizons. In an era marked by entangled crises, distributed agencies, and global interdependencies, relational thinking enables the discipline to confront complexity through connectivity, negotiation, and iterative adaptability. This shift—from isolated forms and deterministic methods toward interdependent systems and emergent processes—represents a paradigmatic departure from object-based reasoning to a networked understanding of space, agency, and authorship. Relationality thus becomes more than a conceptual lens; it offers a generative framework for cultivating sustainable, inclusive, and adaptive architectural practices that engage not only individual users but entire communities, ecosystems, and the broader web of human and non-human entanglements. However, realizing the full potential of this paradigm within built environments demands critical engagement with its practical and conceptual challenges. While relational thinking offers a promising theoretical realignment, several limitations must be acknowledged. Translating relational frameworks into real-world projects requires extensive coordination among diverse stakeholders, longer timelines, and flexible procurement mechanisms—conditions often constrained by rigid contractual norms and standardized regulatory infrastructures. Without parallel institutional reform, implementation may falter. Moreover, the strong emphasis on systemic interconnectivity risks marginalizing the phenomenological and tactile dimensions of architecture. A relational approach must reintegrate attention to materiality and sculptural form, ensuring buildings are sensed and embodied—not only mapped as networked systems. Design education and project workflows also present critical gaps. Although participatory and networked methodologies are highlighted in discourse, their integration into architectural curricula and professional routines remains underdeveloped. Embedding relational thinking through hybrid studio models—such as ecological living labs, iterative prototyping environments, and multi-agent simulations—could operationalize these principles more effectively. Professionally, the development of interdisciplinary teams, including ecologists, social scientists, data experts, and builders, is essential to embed relational logics into the full lifecycle of architectural delivery.

From a methodological standpoint, this research—grounded in thematic coding and interpretive clustering—embraces a qualitative framework that allows for rich, nuanced insights into relational trends across architectural discourse. While interpretive approaches inherently involve subjective judgment, deliberate efforts were made to ensure coherence, analytical transparency, and conceptual robustness. Future studies may further enhance methodological depth by documenting the evolution of the coding framework, elaborating on coder collaboration processes, and incorporating validation strategies such as triangulation or audit trails, thereby fostering greater replicability and critical reflexivity.

Ultimately, the enduring influence of relational thinking will depend not only on its conceptual sophistication but on its capacity to shape architectural cultures, tools, and norms. For this paradigm to transition from discourse to durable transformation, the way of thinking must be integrated into the institutional, pedagogical, and material infrastructures of architectural practice—thereby guiding the discipline toward insights that are materially grounded, ethically attuned, and structurally scalable within an increasingly complex world. Once embedded both theoretically and practically in the field of architecture, it can be assumed that relational thinking will offer a generative framework for cultivating more sustainable, adaptable, and meaningful architectural practices that address not only the needs of individual users but also those of communities, ecosystems, and the broader web of human and non-human entanglements.