Towards Inclusive and Resilient Living Environments for Older Adults: A Methodological Framework for Assessment of Social Sustainability in Nursing Homes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Historical Context of the Living Environment for Older Adults

2.1. Architectural Competitions

2.2. Transfer of Knowledge from Sweden to Slovenia

2.3. Continuity and Contemporary Approach

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Description of Assessment Tools

3.2. Description of the Case Studies

3.3. Evaluation Procedure

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| REL | Residential Environment Liveability |

| LTC | Long-Term Care |

| SC | Safe and Connected |

| WI | Well-being and Integration |

Appendix A

| Fields | Criteria | Parameter | S * | LE_4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bubble concept | Small household units | Twelve residents = 100% matching the criteria | 1 | 1 |

| Single bedrooms with private bathroom | Share of single bedrooms with private bathroom (%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Common rooms | Each smaller unit has its own common social space (%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Outdoor space | Open space and green areas | Guideline—at least 10 m2/resident nearby (nursing) home (%) | 1 | 1 |

| Rooms with balconies | Share of rooms with balconies (%) | 1 | 0.25 | |

| Common rooms with balconies/terraces or/and visual contact with the outdoor environment | - Each common room (of each unit) has its own balcony or terrace (1 s). - Visual contact with outdoor spaces (0.5 s)? | 1 | 1 | |

| Distancing space | “Grey zone” | - Flexible room (1 s). - Outdoor unit (0.75 s). Common rooms (0.5 s). - Rooms of residents (0.25 s). | 1 | 1 |

| “Safe room” for visitors | - External access for visitors and prevention of airborne transmission of viruses by transparent (soft) curtain barrier (1 s). - External access for visitors and prevention of airborne transmission of viruses by transparent wall/window barrier (0.75 s). - Internal access for visitors and prevention of airborne transmission of viruses by transparent wall/window barrier (0.5 s). - Internal access for visitors without prevention of airborne transmission of viruses (0.25 s). | 1 | 0.75 | |

| “Red zone” | - Flexible room (1 s). - Outdoor unit (0.75 s). - Common rooms (0.5 s). - Rooms of residents (0.25 s). | 1 | 1 | |

| Ventilation | Bedrooms | (See the explanation in [12]) | 1 | 0.75 |

| Common rooms | 1 | 0.75 | ||

| Corridors and staircases | 1 | 0.75 | ||

| Architectural protective measures | Quarantine of delivered goods | No (0 s) Partially (0.165 s) Yes (0.33 s) | 1 | 0.33 |

| Staff working in bubble | No (0 s) Partially (0.165 s) Yes (0.33 s) | 0.33 | ||

| Limited movement of visitors | No (0 s) Partially (0.165 s) Yes (0.33 s) | 0.33 | ||

| Contactless door | For each main entrance, bathrooms, rooms No (0 s) Partially (0.165 s) Yes (0.33 s) | 1 | 0.165 | |

| Use of outdoor areas by healthy residents | No (0 s) Partially (0.165 s) Yes (0.33 s) | 0.33 | ||

| Individual entrance | For each employee, resident, and delivery No (0 s) Partially (0.165 s) Yes (0.33 s) | 0.33 | ||

| Common rooms | Reduction in capacity if used or protocol of use or partition of space No (0 s) Partially (0.25 s) Yes (0.5 s) | 1 | 0.5 | |

| “Flexible room” | Is there a flexible room in the NH? No (0 s) Partially (0.25 s) Yes (0.5 s) | 0.5 | ||

| Scores total | 15 | 13.065 | ||

| Estimated degree (%) | 100 | 87 |

| Fields | Criteria | Parameter | S * | LE_4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sense of belonging | Distinction between private and public space; hierarchy of open spaces in a residential environment | Appropriate selection of building types and planning of different types of open spaces (public, semi-public, semi-private, and private = 100% matching the criteria) | 3 | 1 |

| Different urban design elements mark the demarcation between different types of spaces (level difference or a change in paving or vegetation/water) No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 1 | |||

| Accesses/entrances to the residential environment and urban design elements that clearly define the entrance to the residential environment (architectural element or change in paving or solitaire tree or urban furniture design) No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 1 | |||

| Design of residential environment, enabling leisure and strengthening social interactions | Variety of experiences and activities; spatial distribution regarding inclusive content (seating area, picnic area, children’s playground, space for social urban games, and walking area = 100% matching the criteria) | 1 | 0.75 | |

| Maintained residential environment | Proportion of maintained areas No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 1 | 1 | |

| Involvement of residents in the residential environment | Number of different local services (local shops, cafés, health care, beauty care, day-care, and public transport = 100% matching the criteria) | 2 | 1 | |

| Number of different activities for residents included in the maintenance of public spaces (planting flowers, landscaping green areas, renovation of urban equipment = 100% matching the criteria) | 1 | |||

| Awareness, participation, and education of residents—active role of residents in the co-design of the residential environment | Information points; volume of lectures and workshops for residents; volume of formal/informal meetings with residents and working groups as forms of resident involvement and the cooperation–participation rate = 100% matching the criteria | 1 | 0.5 | |

| Diversity of living unit typologies | Integration of different social groups into the residential environment: secured apartment, household unit, experimental apartment, and low-density houses = 100% matching the criteria | 1 | 0.25 | |

| Sense of safety | Lively and controlled public space | Presence of people in the space (number of people using the space in certain time segments); mixed use of the space (r = 300 m) (commercial, education, kindergarten, and recreation = 100% matching the criteria) | 3 | 0.5 |

| Dominant share of buildings with glazed surfaces of street facades or facades oriented towards public space No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 1 | |||

| Smaller number of apartments arranged in departments and larger number of entrances to the residential building = 100% matching the criteria | 1 | |||

| Protection of private space and interaction with public space | Orientation of entrances towards the street, distance of residential entrances to buildings from the street (front yard), design of the entrance element with a canopy and benches = 100% matching the criteria | 1 | 1 | |

| Design of the residential environment, enabling orientation in space | Various elements of open space design in a residential environment (single tree or avenue or platform levels or sculptures or urban furniture) No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 1 | 1 | |

| Lighting of open space in the residential environment | Share of adequately illuminated open spaces: building entrances, paths, staircases, and social areas = 100% matching the criteria | 1 | 1 | |

| Priority for pedestrian and traffic safety | Motorised roads vs. pedestrianised: streets for pedestrians and motorised traffic roads (0 s)/traffic-calmed areas (0.5 s)/streets for pedestrians and cyclists (1 s) | 1 | 1 | |

| Sense of enjoyment and comfort | Human scale of the residential environment | Share of streets that are attractive for walking: urban furniture, pedestrian pavement, shadow, no blank facades, active ground floor No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 5 | 1 |

| Spacing between buildings (max = 100 m, min = 2H) and building height (up to four floors) No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 1 | |||

| Arrangement and articulation of open space: diverse character and connectivity of open spaces No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 1 | |||

| A dense network of paths with numerous shortcuts No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 1 | |||

| Insolation of open space No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 1 | |||

| Creating quiet areas/ reducing noise level and quality of the air | Placing greenery between motor roads and residential areas Noise level (max = 45 dB) No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) and pollution of open space; greenhouse gas emissions (daily limit concentration of PM10: 50 µg/m3, permitted exceedance—35 times in a calendar year), annual limit concentration of PM10: 40 µg/m3 No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 1 | 1 | |

| Design of the residential environment, enabling contact with natural landscapes and reducing the heat island effect | Share of green and water/built-up open areas (more than 65% of the area = 1 s, 65–30% = 0.5 s, less than 30% = 0 s) | 2 | 1 | |

| Green and water elements: tall vegetation and trees and water elements (natural and urban design elements) The Green Space Factor No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 1 | |||

| Scores total | 24 | 22 | ||

| Estimated degree (%) | 100 | 92 |

References

- McHugh, K. Three faces of ageism: Society, image and place. Ageing Soc. 2003, 23, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, J. Interiors: Architecture in the lives of people with dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1989, 4, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calkins, M.P. The physical and social environment of the person with Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Ment. Health 2001, 5, 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- De Mello, K.K. Healing Through Design: The Psychological Effects of Design on the Elderly. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Passini, R.; Rainville, C.; Marchand, N.; Joanette, Y. Wayfinding and dementia: Some research findings and a new look at design. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 1998, 15, 133–151. [Google Scholar]

- Brawley, E.C. Environment for Alzheimer’s disease: A quality of life issue. Aging Ment. Health 2001, 5, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, S. The design of caring environments and the quality of life of older people. Ageing Soc. 2002, 22, 775–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Kane, R.L.; Shamliyan, T.A. Effect of nursing home characteristics on residents’ quality of life: A systematic review. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2013, 57, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Žegarac Leskovar, V.; Skalicky Klemenčič, V. Inclusive design: Comparing models of living environments for older adults. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics and the Affiliated Conferences, San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–24 July 2023; Di Bucchianico, P., Ed.; AHFE Open Access: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Volume 75, pp. 189–197, ISBN 978-1-958651-51-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Review of Capacities of Institutional Care for the Elderly and Special Groups of Adults. 1 January 2025. Available online: https://www.ssz-slo.si/splosno-o-posebnih-domovih/pregled-kapacitet-in-pokritost-institucionalnega-varstva-starejsih-in-posebnih-skupin-odraslih/pregled-kapacitet-institucionalnega-varstva-starejsih-in-posebnih-skupin-odraslih-1-1-2025-2/ (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Castle, N.; Ferguson, J. What Is Nursing Home Quality and How Is It Measured? Gerontologist 2010, 50, 426–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Žegarac Leskovar, V.; Skalicky Klemenčič, V. Designing a safe and inclusive housing environment for older adults: Assessment of nursing home preparedness for post-COVID era. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2024, 39, 663–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.; Torrington, J.; Barnes, S.; Darton, R.; Holder, J.; McKee, K.; Netten, A.; Orrell, A. EVOLVE: A tool for evaluating the design of older people’s housing. Hous. Care Support 2010, 13, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eijkelenboom, A.; Verbeek, H.; Felix, E.; van Hoof, J. Architectural factors influencing the sense of home in nursing homes: An operationalization for practice. Front. Archit. Res. 2017, 6, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, N.W.; Lowe, J.I.; Ryan, S.F. Promoting an alternative to traditional nursing home care: Evaluating the Green House Small Home Model. Health Serv. Res. 2016, 51, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skalicky Klemenčič, V.; Čerpes, I. Comprehensive assessment methodology for liveable residential environment. Cities 2019, 94, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brantenberg, T. (Ed.) Nordic Housing—Habitación Nórdica 1945–1980: Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden; Catalogue of the Exhibition at the UIA Congress in Mexico 1978; Norske Arkitekters Landsforbund: Mexico City, Mexico, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanšek, F. The Manual: Buildings and Equipment for the Older Adults [Zgradbe in Oprema za Stare Ljudi]; Ambient: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Skalicky Klemenčič, V. Contemporary Scandinavian Urban Planning Principles and Criteria for High-Quality Living in Residential Environments. Ph.D. Thesis, [V. Skalicky], Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Global AgeWatch Index 2013, Executive Summary. Available online: http://www.globalagewatch.org (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Symbiocare. About Symbiocare—Health by Sweden. Available online: http://www.symbiocare.org/about-symbiocare/ (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Peterson, E. Eldercare in Sweden: An overview. Rev. Derecho Soc. Empresa 2017, 8, 90–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edebalk, P.G. From Poor Relief to Universal Rights—On the Development of Swedish Old-Age Care 1900–1950; Socialhögskolan, Lund Universitet: Lund, Sweden, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, J.E. Architecture and the Swedish welfare state: Three architectural competitions that innovated space for dependent and frail older people. Ageing Soc. 2015, 35, 837–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanšek, F. Osnovne poteze skandinavske stanovanjske politike. Arhitekt 1955, 16, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Humek, L. Po Švici, Švedski, Finski. Arhitekt 1952, 8, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Malešič, M. Risbe iz stockholmskih arhivov: Poskus rekonstrukcije švedske izkušnje arhitektov Franceta in Marte Ivanšek. Acta Hist. Artis Slov. 2021, 26, 167. [Google Scholar]

- Trebar, H. DOMA: Arhitekta France in Marta Ivanšek; Slovensko Umetnostnozgodovinsko Društvo: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2010; Available online: http://www.suzd.si/bilten/arhiv/bilten-suzd-5-7-2009-2010/307-predstavitve/188-doma-arhitekta-france-in-marta-ivanek (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Malešič, M. Arhitekta France in Marta Ivanšek. Bachelor’s Thesis, Filozofska Fakulteta Univerze v Ljubljani, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Penhoet, M.; Widerberg Andersen, K. Enhancing Dynamic Capabilities through Organizational Leadership amid COVID-19 Disruption: A Case Study of a Social Innovation Housing Project in Sweden. Master’s Thesis, Malmö University, Malmö, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- International Study Mission on Elderly Care: Insights from Sweden and The Netherlands. 2025. Available online: https://www.silvereco.org/en/international-study-mission-on-elderly-care-insights-from-sweden-and-the-netherlands/ (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Creating Sustainable and Healthy Living Environments for an Ageing Population. 2025. Available online: https://whitearkitekter.com/news/creating-sustainable-and-healthy-living-environments-for-an-ageing-population/ (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Artmann, M.; Chen, X.; Ioja, C.; Hof, A.; Onose, D.; Poniży, L.; Lamovšek, A.Z.; Breuste, J. The role of urban green spaces in care facilities for elderly people across European cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 27, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marge Arkitekter. The Gardens Care Home. 2018. Available online: https://www.marge.se/projects/the-gardens (accessed on 7 August 2022).

- Kerbler, B.K.; Sendi, R.; Filipovič Hrast, M. Trajnostne oblike stanovanjske oskrbe starejših v Sloveniji. Urbani izziv, Posebna izdaja 2019, 9. Urbanistični inštitut Republike Slovenije: Ljubljana, Slovenia. Available online: https://www.dlib.si/details/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-IW09ZAA2 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Steiner, N. Starostniki čakajo v dolgi vrsti na dom, čeprav so postelje prazne, ker ni kadra. 2023. Available online: https://www.24ur.com/novice/dejstva/starostniki-cakajo-v-dolgi-vrsti-na-dom-ceprav-so-postelje-prazne-a-kadra-ni.html (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Zupančič, B. Stanovanjska Arhitektura v Tržnih Pogojih: Denar, Tržni Pogoji in Menedžment v Arhitekturi. Ph.D. Thesis, Univerza v Ljubljani, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pečenko, B. Anketa o problematiki stanovanjske gradnje. Arhit. Bilt. 1984, 68–69, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Lestan, K.; Goličnik Marušić, B.; Eržen, I.; Golobič, M. Odprti prostor stanovanjskih naselij povečuje kakovost grajenega. IB Rev. 2013, 1, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gazvoda, D. Vloga in pomen zelenega prostora v novejših slovenskih stanovanjskih soseskah. Urbani Izziv 2001, 12, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihelič, B. Urbanistični Razvoj Ljubljane; Partizanska Knjiga: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Pirkovič Kocbek, J. Izgradnja Sodobnega Maribora; Partizanska Knjiga: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Cities for People; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. Site Planning; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, O. Creating Defensible Space; U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, E.; Waterman, T. Urban Design; AVA Publishing: Singapore, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jernejec, M. Stanovanjsko Okolje—1. Del: Človek, Njegovo Okolje in Potrebe; Urbanistični Inštitut SRS: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Van Kempen, R. Regeneracija Velikih Stanovanjskih Sosesk v Evropi: Priročnik za Boljšo Prakso; UIRP: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, T.; White, C.; Hilton, J.; Kucharski, A.; Pellis, L.; Stage, H.; Davies, N.; Keeling, M.J.; Flasche, S. The effectiveness of social bubbles as part of a COVID-19 lockdown exit strategy, a modelling study. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MASS Design Group. The Role of Architecture in Fighting COVID-19 in Designing Senior Housing for Safe Interaction. Available online: https://massdesigngroup.org/covidresponse (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- White, M.P.; Elliott, L.R.; Grellier, J.; Economou, T.; Bell, S.; Bratman, G.N.; Cirach, M.; Gascon, M.; Lima, M.L.; Lõhmus, M.; et al. Associations between green/blue spaces and mental health across 18 countries. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laan, C.M.; Piersma, N. Accessibility of green areas for local residents. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2021, 10, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, C.F. Dividing the Emergency Department into Red, Yellow, and Green Zones to Control COVID-19 Infection; a Letter to Editor. Arch. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2020, 8, e60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sommerstein, R.; Fux, C.A.; Vuichard-Gysin, D.; Abbas, M.; Marschall, J.; Balmelli, C.; Troillet, N.; Harbarth, S.; Schlegel, M.; Swissnoso; et al. Risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission by aerosols, the rational use of masks, and protection of healthcare workers from COVID-19. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2020, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyerowitz, E.A.; Richterman, A.; Gandhi, R.T.; Sax, P.E. Transmission of SARS-COV-2: A review of viral, host, and environmental factors. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 8 December 2021).

- Vartholomaios, A.; Kalogirou, N. The Green Space Factor as a Tool for Regulating the Urban Microclimate in Vegetation-Deprived Greek Cities Changing Cities; Graphima: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rom, Y.; Morag, I.; Palgi, Y.; Isaacson, M. The Architectural Layout of Long-Term Care Units: Relationships between Support for Residents’ Well-Being and for Caregivers’ Burnout and Resilience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Assessment Fields | Explanation |

|---|---|

| F1: Sense of belonging | The residents’ sense of belonging is one of the essential elements of a humane environment and contributes to the sustainable use of space. It is generally acknowledged that humans instinctively want to define the boundaries of their personal and communal territory. Boundaries within the residential environment need to be defined so that residents can develop their individuality in arranging “their” territory and so that residents, the social community, and the public have a clear idea of what belongs to whom and who takes care of what. Among other things, this contributes to reducing vandalism in the residential environment [48]. |

| F2: Sense of safety | Safety is one of the essential necessities of life. People will accept an environment as their own when it provides them with a sense of safety in their living environment, traffic safety, and security from crime. Physical strategies in spatial design can effectively increase the sense of safety, although they do not in themselves guarantee safety, as explained by [49]. |

| F3: Sense of enjoyment and comfort | It is necessary to create quality spaces between buildings. The spaces between buildings play an important role, as they are not limited only to the amount of open space and usability, but also to the attractiveness and comfort for the user. |

| Assessment Fields | Explanation |

|---|---|

| F1: Bubble concept | The concept of social bubbles, defined as small groups of individuals with limited outside contact, has been demonstrated to be an effective strategy for reducing the spread of infectious diseases, such as COVID-19 [50]. Within the context of nursing homes, this approach aligns with the fourth- and fifth-generation European models, which advocate for small household-like units of up to 12 residents with private rooms and bathrooms. |

| F2: Outdoor space | Access to outdoor space, including balconies, terraces, and green areas, has been demonstrated to enhance the physical and mental well-being of residents, whilst also facilitating safer social interaction during health crises [51]. Visual and physical connections to nature have been demonstrated to support psychological health [52]. The recommended minimum area of green space per resident within 800 m of living environments is 10 m2 [53]. |

| F3: Distancing space | During the COVID-19 pandemic, nursing homes with flexible spatial layouts adapted rooms into red and grey zones to isolate infected residents and control infection spread. The zoning strategy (red/yellow/green) proved effective in reducing the spread of infection [54]. Additionally, visitor rooms divided by transparent barriers allowed safe social contact and helped mitigate the effects of isolation during lockdown periods. |

| F4: Ventilation | Numerous studies in medicine and epidemiology have confirmed that SARS-CoV-2 spreads via droplets, aerosols, direct contact, and contaminated surfaces. The potential for airborne transmission highlights the essential role of ventilation in reducing indoor viral load [55,56]. The WHO issued specific guidelines to support effective ventilation during the COVID-19 pandemic [57]. |

| F5: Architectural protective measures | Architectural–organisational measures have been shown to play a key role in preventing the introduction and transmission of infections in nursing homes. These include restrictions, such as the implementation of controlled access and visitor tracking systems, a reduction in physical contact using contactless doors and separate entrances, and spatial adaptations for safe socialisation, including the use of flexible or outdoor spaces [51]. |

| Case Study | Year | Ownership | Capacity (Inhabitants) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LE_1 | 1960s | public | 321 |

| LE_2 | late 1970s | public | 192 |

| LE_3 | 2021 | private | 150 |

| Fields | Criteria | Parameter | S * | LE_1 | LE_2 | LE_3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bubble concept | Small household units | Twelve residents = 100% matching the criteria | 1 | 0.71 | 1 | 0.75 |

| Single bedrooms with private bathroom | Share of single bedrooms with private bathroom (%) | 1 | 0.4 | 0.77 | 0.97 | |

| Common rooms | Each smaller unit has its own common social space (%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Outdoor space | Open space and green areas | Guideline—at least 10 m2/resident nearby (nursing) home (%) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Rooms with balconies | Share of rooms with balconies (%) | 1 | 0.9 | 0.53 | 0 | |

| Common rooms with balconies/terraces or/and visual contact with the outdoor environment | - Each common room (of each unit) has its own balcony or terrace (1 s) - Visual contact with outdoor spaces (0.5 s)? | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | |

| Distancing space | “Grey zone” | - Flexible room (1 s). - Outdoor unit (0.75 s). - Common rooms (0.5 s). - Rooms of residents (0.25 s). | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 |

| “Safe room” for visitors | - External access for visitors and prevention of airborne transmission of viruses by transparent (soft) curtain barrier (1 s). - External access for visitors and prevention of airborne transmission of viruses by transparent wall/window barrier (0.75 s). - Internal access for visitors and prevention of airborne transmission of viruses by transparent wall/window barrier (0.5 s). - Internal access for visitors without prevention of airborne transmission of viruses (0.25 s). | 1 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.75 | |

| “Red zone” | - Flexible room (1 s). - Outdoor unit (0.75 s). - Common rooms (0.5 s). - Rooms of residents (0.25 s). | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.25 | |

| Ventilation | Bedrooms | (See the explanation in [12]) | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.75 |

| Common rooms | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.75 | ||

| Corridors and staircases | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.75 | ||

| Architectural protective measures | Quarantine of delivered goods | No (0 s) Partially (0.165 s) Yes (0.33 s) | 1 | 0.33 | 0.165 | 0.33 |

| Staff working in bubble | No (0 s) Partially (0.165 s) Yes (0.33 s) | 0.33 | 0 | 0.33 | ||

| Limited movement of visitors | No (0 s) Partially (0.165 s) Yes (0.33 s) | 0.33 | 0.165 | 0.165 | ||

| Contactless door | For each main entrance, bathroom, and room No (0 s) Partially (0.165 s) Yes (0.33 s) | 1 | 0.165 | 0.165 | 0.165 | |

| Use of outdoor areas by healthy residents | No (0 s) Partially (0.165 s) Yes (0.33 s) | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.33 | ||

| Individual entrance | For each employee, resident, and delivery No (0 s) Partially (0.165 s) Yes (0.33 s) | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.33 | ||

| Common rooms | Reduction in capacity if used or protocol of use or partition of space No (0 s) Partially (0.25 s) Yes (0.5 s) | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| “Flexible room” | Is there a flexible room in the NH? No (0 s) Partially (0.25 s) Yes (0.5 s) | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | ||

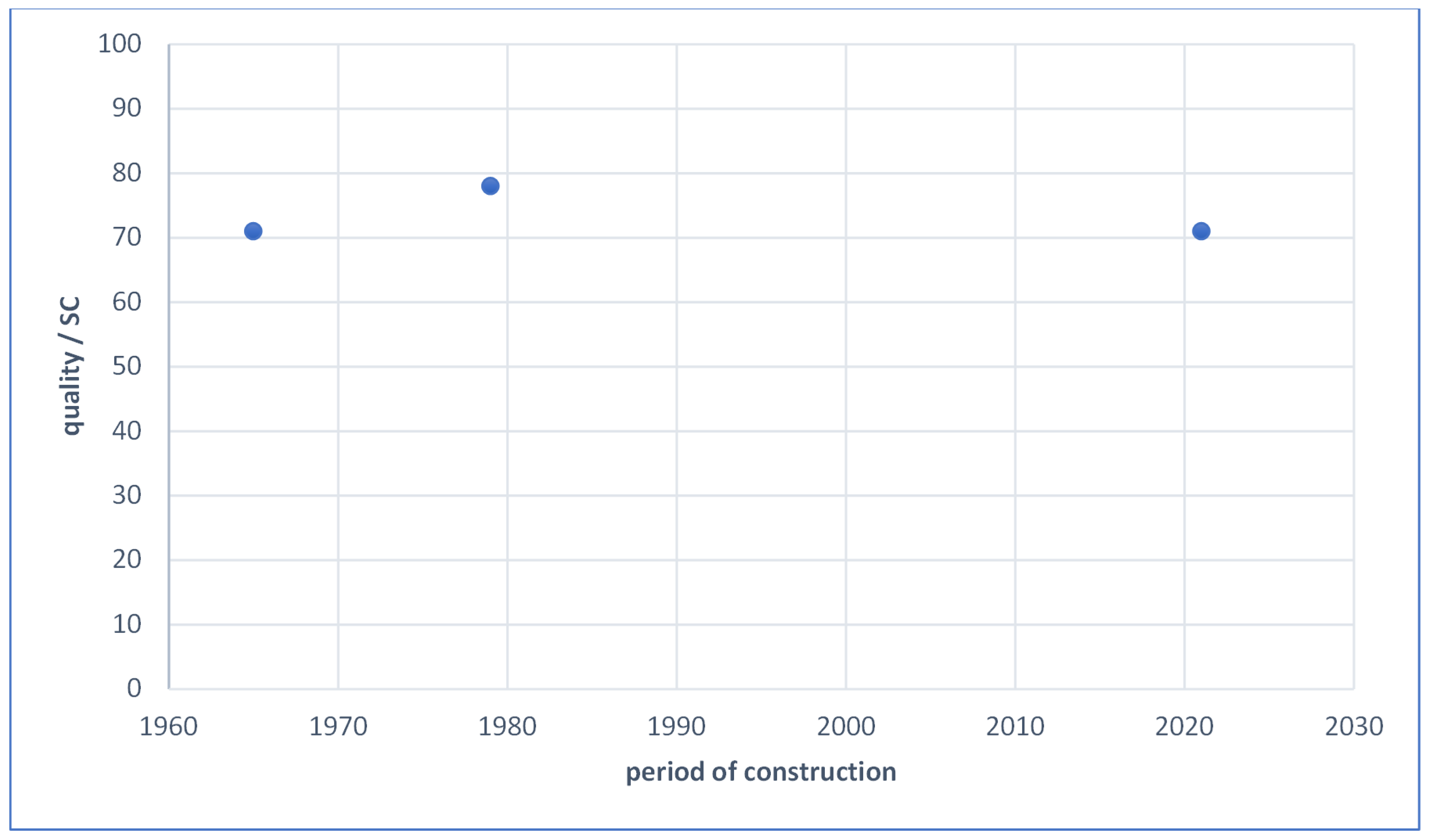

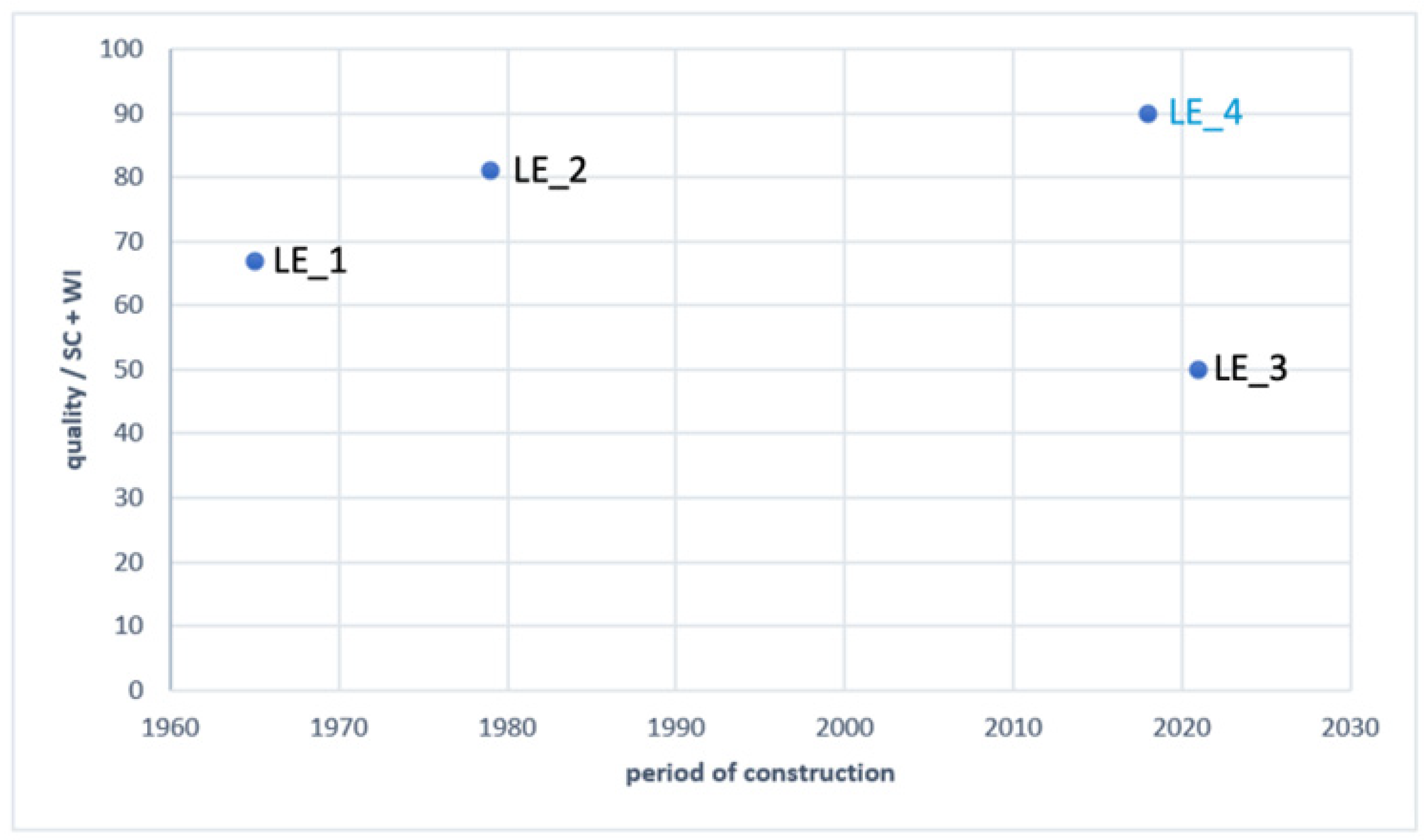

| Scores total | 15 | 10.575 | 11.705 | 10.620 | ||

| Estimated degree (%) | 100 | 71 | 78 | 71 |

| Fields | Criteria | Parameter | S * | LE_1 | LE_2 | LE_3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sense of belonging | Distinction between private and public space; hierarchy of open spaces in a residential environment | Appropriate selection of building types and planning of different types of open space (public, semi-public, semi-private, and private = 100% matching the criteria) | 3 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 |

| Different urban design elements mark the demarcation between different types of spaces (level difference or a change in paving or vegetation/water) No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Accesses/entrances to the residential environment and urban design elements that clearly define the entrance to the residential environment (architectural element or change in paving or solitaire tree or urban furniture design) No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Design of the residential environment, enabling leisure and strengthening social interactions | Variety of experiences and activities, spatial distribution regarding inclusive content (seating area, picnic area, children’s playground, space for social urban games, and walking areas = 100% matching the criteria) | 1 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 | |

| Maintained residential environment | Proportion of maintained areas No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Involvement of residents in the residential environment | Number of different local services (local shops, cafés, health care, beauty care, day-care, and public transport = 100% matching the criteria) | 2 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0 | |

| Number of different activities for residents included in the maintenance of public spaces (planting flowers, landscaping green areas, renovation of urban equipment = 100% matching the criteria) | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.33 | |||

| Awareness, participation, and education of residents—active role of residents in the co-design of the residential environment | Information points, volume of lectures and workshops for residents, volume of formal/informal meetings with residents and working groups as forms of resident involvement and the cooperation–participation rate = 100% matching the criteria | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |

| Diversity of living unit typologies | Integration of different social groups into the residential environment: secured apartment, household unit, experimental apartment, and low-density houses = 100% matching the criteria | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.25 | |

| Sense of safety | Lively and controlled public space | Presence of people in the space (number of people using the space in certain time segments); mixed use of the space (r = 300 m): commercial, education, kindergarten, and recreation = 100% matching the criteria | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 |

| Dominant share of buildings with glazed surfaces of street facades or facades oriented towards public space No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Smaller number of apartments arranged in departments and larger number of entrances to the residential building = 100% matching the criteria | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | |||

| Protection of private space and interaction with public space | Orientation of entrances towards the street, distance of residential entrances to buildings from the street (front yard), design of the entrance element with a canopy and benches = 100% matching the criteria | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 | |

| Design of residential environment, enabling orientation in space | Various elements of open space design in a residential environment (single tree or avenue or platforms levels or sculptures or urban furniture) No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 1 | 0.50 | 1 | 0 | |

| Lighting of open space in the residential environment | Share of adequately illuminated open spaces: building entrances, paths, staircases, and social areas = 100% matching the criteria | 1 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.25 | |

| Priority for pedestrian and traffic safety | Motorised roads vs. pedestrianised: streets for pedestrians and motorised traffic roads (0 s)/traffic-calmed areas (0.5 s)/streets for pedestrians and cyclists (1 s) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Sense of enjoyment and comfort | Human scale of the residential environment | Share of streets that are attractive for walking: urban furniture, pedestrian pavement, shadow, no blank facades, active ground floor No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 |

| Spacing between buildings (max = 100 m, min = 2H) and building height (to four floors) No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | |||

| Arrangement and articulation of open space: diverse character and connectivity of open spaces No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | |||

| A dense network of paths with numerous shortcuts No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Insolation of open space No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Creating quiet areas/ reducing noise level and quality of the air | Placing greenery between motor roads and residential areas Noise level (max = 45 dB) No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) and pollution of open space; greenhouse gas emissions (daily limit concentration of PM10: 50 µg/m3, permitted exceedance—35 times in a calendar year, annual limit concentration of PM10: 40 µg/m3) No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 1 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | |

| Design of the residential environment, enabling contact with natural landscapes and reducing the heat island effect | Share of green and water/built-up open areas more than 65% of the area = 1 s, 65–30% = 0.5 s, less than 30% = 1 s, 65–30% = 0.5 s, less than 30% = 0 s | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | |

| Green and water elements: tall vegetation and trees and water elements (natural and urban design elements) The Green Space Factor [58] No (0 s)/Partially (0.5 s)/Yes (1 s) | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||

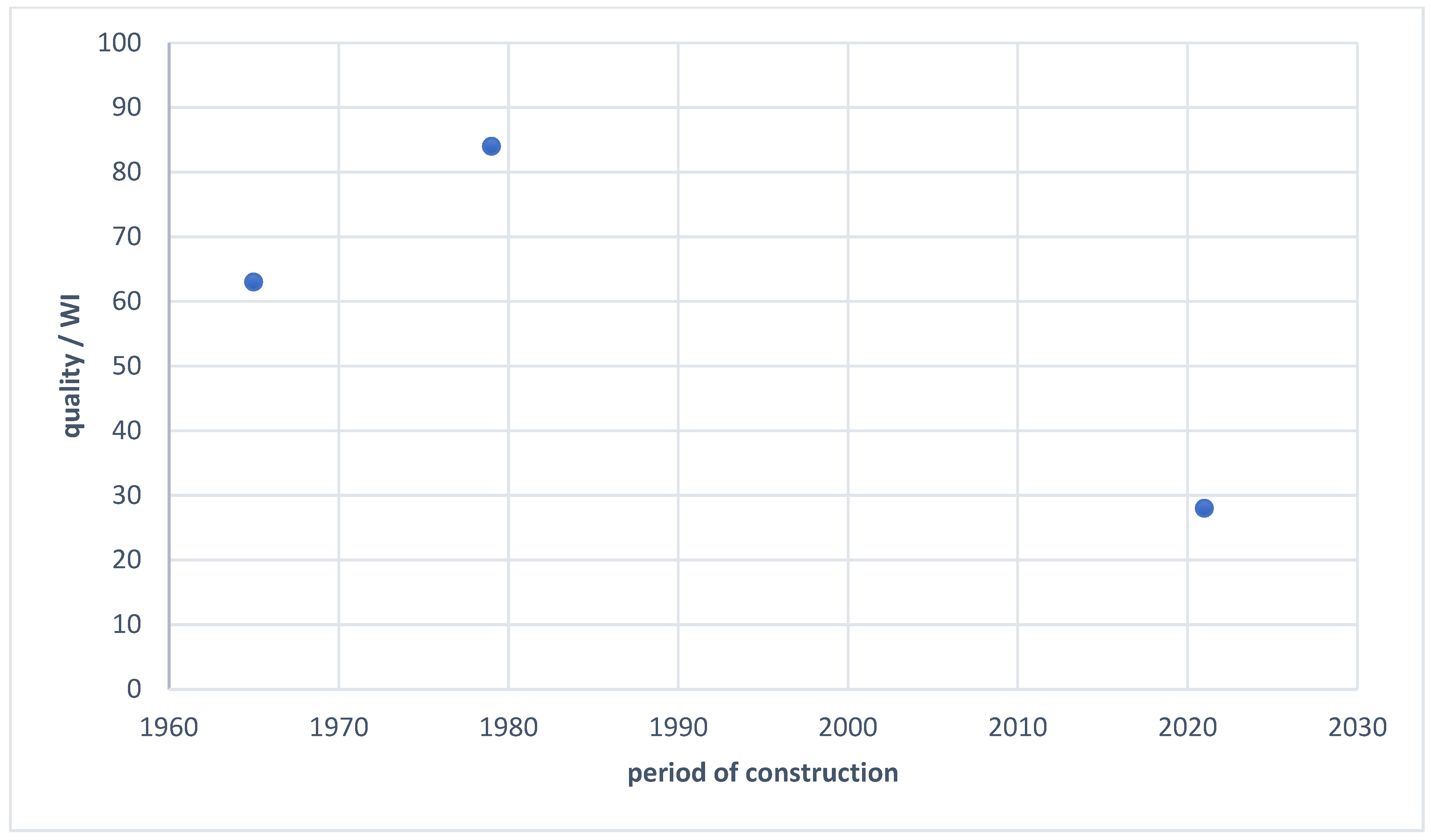

| Scores total | 24 | 15.23 | 20.08 | 6.68 | ||

| Estimated degree (%) | 63 | 84 | 28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Skalicky Klemenčič, V.; Žegarac Leskovar, V. Towards Inclusive and Resilient Living Environments for Older Adults: A Methodological Framework for Assessment of Social Sustainability in Nursing Homes. Buildings 2025, 15, 2501. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15142501

Skalicky Klemenčič V, Žegarac Leskovar V. Towards Inclusive and Resilient Living Environments for Older Adults: A Methodological Framework for Assessment of Social Sustainability in Nursing Homes. Buildings. 2025; 15(14):2501. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15142501

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkalicky Klemenčič, Vanja, and Vesna Žegarac Leskovar. 2025. "Towards Inclusive and Resilient Living Environments for Older Adults: A Methodological Framework for Assessment of Social Sustainability in Nursing Homes" Buildings 15, no. 14: 2501. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15142501

APA StyleSkalicky Klemenčič, V., & Žegarac Leskovar, V. (2025). Towards Inclusive and Resilient Living Environments for Older Adults: A Methodological Framework for Assessment of Social Sustainability in Nursing Homes. Buildings, 15(14), 2501. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15142501