1. Introduction

The internationally recognized Venice Charter states that every effort should be made to preserve and pass on cultural heritage to future generations. Both physical and esthetic features/values and the historical and cultural values the building represents for society need to be taken into consideration when it comes to preservation through reusing architectural heritage that has become abandoned over time for whatever reason. The question of the building’s meaning to its environment throughout time brings up concepts around “memory” and lived experiences.

According to Halbwachs [

1,

2], one of the pioneers of memory studies, memory derives its source from the “group” and has a collective nature. Also referring to Halbwachs [

1], Nora [

3] discusses the concept of “memory sites” through the example of France, analyzing the conditions under which history is reproduced today, unlike the past. Nora looks at the role memory plays in the idea of nation-building, meaning the continuity of a nation from the past to the present and its conflicts [

4]. In this study, Nora [

3] defines memory sites as not only the things we remember, but also all kinds of material and spiritual places/environments, rituals and materials where memory emerges, is formed, kept alive, or prevents forgetting. Referencing Halbwachs [

1] and Nora [

3], Assmann [

5] states that memory needs space and every community wanting to consolidate itself as a group tends to create memory spaces as symbols of their identity and the basis of their memories.

Connerton [

6], on the other hand, draws attention to the fact that modernity has a problem with “forgetfulness” caused by the expansion of settlements and the deliberate destruction of built environments, leading to cultural amnesia. Therefore, changing production and consumption conditions, population growth and irregularity of population density cause the unplanned, uncontrolled, rapid growth of cities, confronting them with concepts of forgetting, erasing, and destroying, as opposed to reminding and remembering. Studies examine this relationship between collective memory, history, and social context [

7,

8]. Connerton [

9] states that, especially in totalitarian regimes, controlling social memory by making certain events forgotten is an important tool in ensuring the continuation of social order.

However, for societies to confront and reconcile with their past and prevent such memory losses, it is even more important to preserve cultural heritage that has witnessed history and past conflicts, especially in societies that do not have a rich or well-documented written history. Enriching cultural heritage can help build inclusive, innovative and resilient societies and lay ground for lasting peace based on mutual respect and open dialogue between cultures. Since its foundation, UNESCO has also emphasized that cultural heritage, along with education, has strong potential to provide a fundamental basis for lasting peace in the world.

In fact, reusing abandoned historical buildings is a method that ensures the preservation and transfer of cultural heritage to the future [

10,

11]. This means adapting the building to realize a change in use requested by its new or existing owners [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Researchers state that the reuse of historical buildings can help managers, entrepreneurs, and societies in reducing environmental, social and economic costs caused by urban development and growth [

16,

17,

18,

19]. Energy self-sufficiency studies in adaptive reuse applications are the product of this effort [

20,

21]. As a matter of fact, existing examples of re-purposing projects in various fields, such as commerce [

19], tourism [

22,

23], and work offices [

17], support this viewpoint.

A reuse project can transform historic buildings into accessible and usable spaces and provide additional benefits such as the sustainable renewal of the area where it is located [

24]. Thus, reuse not only preserves a historical building, but also the craftsmen’s effort, skill, and dedication [

25], as well as architectural, social, cultural and historical values [

14]. Researchers state that the reuse of historical buildings contributes to the efficient use of materials and resources, cost reduction, and the buildings’ survival [

11,

26].

Buildings and places of historical importance are carriers of collective memories, which, in combination with local characters, create the special spirit of place. These relationships become an integral part of the local community over time, creating a story specific to that place. Therefore, historical buildings offer a glimpse into the past not only by their physical esthetic forms but also by the intangible memories or genius loci of their interiors. Therefore, the benefits of reusing historical buildings are not limited to creating economic or ecological opportunities, but are also associated with contributing to the social, cultural and psychological stability of the community or region, preserving the references of their past for the future and playing a positive role in creating a diverse and sustainable environment [

27]. Plevoets and van Cleempoel [

28] suggested that preserving these intangible memories was a challenging task. Nevertheless, they hold important potential to create a concrete or abstract bond between the new generations and their culture.

Here, adaptive reuse is considered as one of the preservation techniques which can help preserve the intangible values [

29], within the scope of cultural heritage with new buildings, but at the same time preserve the identity of the place by creating a balance between the use and meaning of the concrete and abstract aspects of the building [

30].

Therefore, the conceptual values of conservation and the practical results of reused historical buildings can be defined as a “sustainable strategy” in terms of ecological, economic, and socio-cultural aspects [

31]. Considering rapid urbanization and continuous disappearance of traditional architecture, the Venice Charter of 1964 states that the protection of architectural heritage should not only be limited to prestigious, monumental or historically important buildings, but also more modest ones. There are many examples of re-functioned building stocks around the world [

19,

29,

32,

33].

This study was carried out as part of a social responsibility project by a team of ten students and professors of the Department of Architecture of Istanbul Beykent University in 2023. Approaching the documentation, evaluation, reuse, and preservation of cultural heritage from an operational perspective, this case study goes beyond theoretical boundaries. As is the case with many historical buildings, in situ documentation enabled the obtention of plans and the determination of construction phases and preservation problems for the first time, while also providing the basis for an effective reuse scheme [

34]. Based on the information and documents obtained in the process, the historical buildings’ technical evaluations and analyses include its re-design as an urban memory museum. The voluntary non-governmental “Green Zara” association, which was established to protect the natural and cultural values of the region, supported the process by establishing connections with local administrations such as the district governor’s office and the municipality.

2. Armenian Primary School, Nuh’s Mansion, 2nd-Degree Historical Building

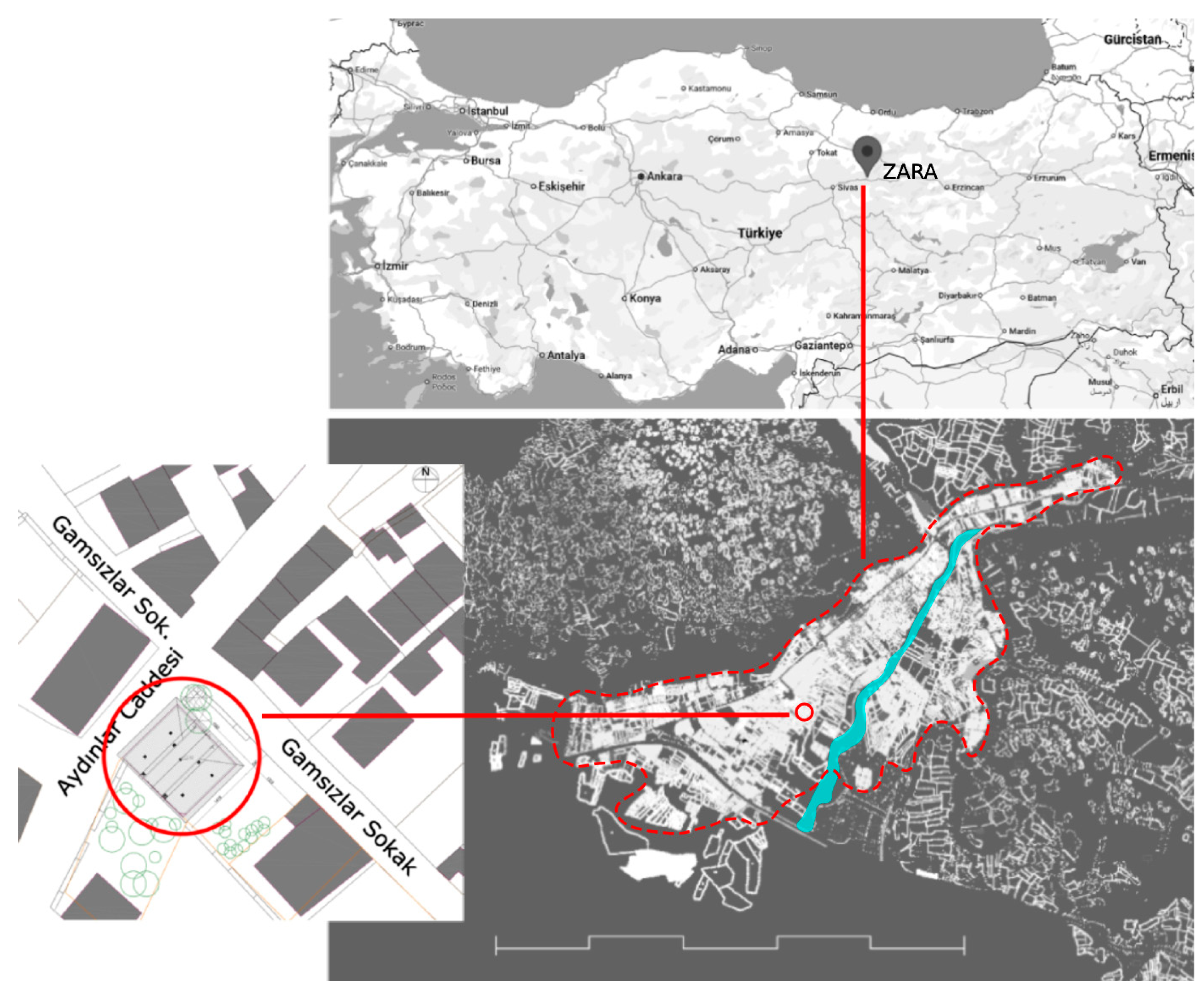

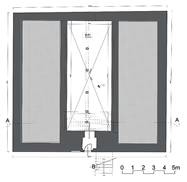

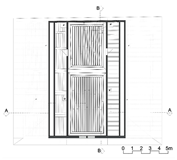

The subject of this study is located on Reşit Paşa Mah. Gamsızlar Sok. No. 12, Block 265, Plot 5 of the Central Anatolian town of Zara, Sivas (

Figure 1).

The building, with a central hall scheme, has three storeys, excluding the basement. Some sources state that the building was constructed as a primary school by Armenian craftsmen with the donations of an Armenian businessman from Zara who had returned from America after 1890 [

35]. However, other sources state that the building only consisted of a ground floor when it was used as an Armenian primary school between 1865 and 1870 [

36]. Kaynar [

37] claims that the construction of the school remained unfinished for many years and was completed as a mansion after its purchase.

According to written sources, the building was also used as a government building for two years. In 1928, it was purchased by the Zühtü-Sıtkı Cantürk brothers, sons of Nuh Efendi, one of the deep-rooted families of Zara [

36,

37]. It was used as a multi-family mansion for approximately two or three generations. Although Nuh Efendi never lived in this building, the mansion is still known among the public as Nuh’s Mansion (Nuh’ların Konağı). Having undergone various modifications during its use as a mansion, the building was registered as a 2nd-degree historical building on 13 November 1982. Currently, it is not in use. Of the 23 mansions in Zara mentioned in written sources [

37], only 6 are registered today. All these mansions are abandoned to their fate and partially in ruins [

38].

Almost all the mansions that are proudly pointed out in Zara today are the work of Armenian craftsmen or their apprentices [

37,

39]. Is it possible that a community with such a developed building culture did not build a church for themselves? There are only very few people today who know about the previous existence and location of a church at Er Sokak No:13 in the Hatip neighbourhood. After detailed examination, the curious can identify some marble blocks of the former church in the plinth wall of one of the mansions that were built in its place (

Figure 2). This shows how the traces of a period and a culture have been erased from memory. This experience, bearing the tragic traces of the erasure of memory, does not support the mutual tolerance and acceptance desired in terms of differences in society, and unfortunately burdens a segment of society with negative and fragile emotions.

3. Materials and Methods

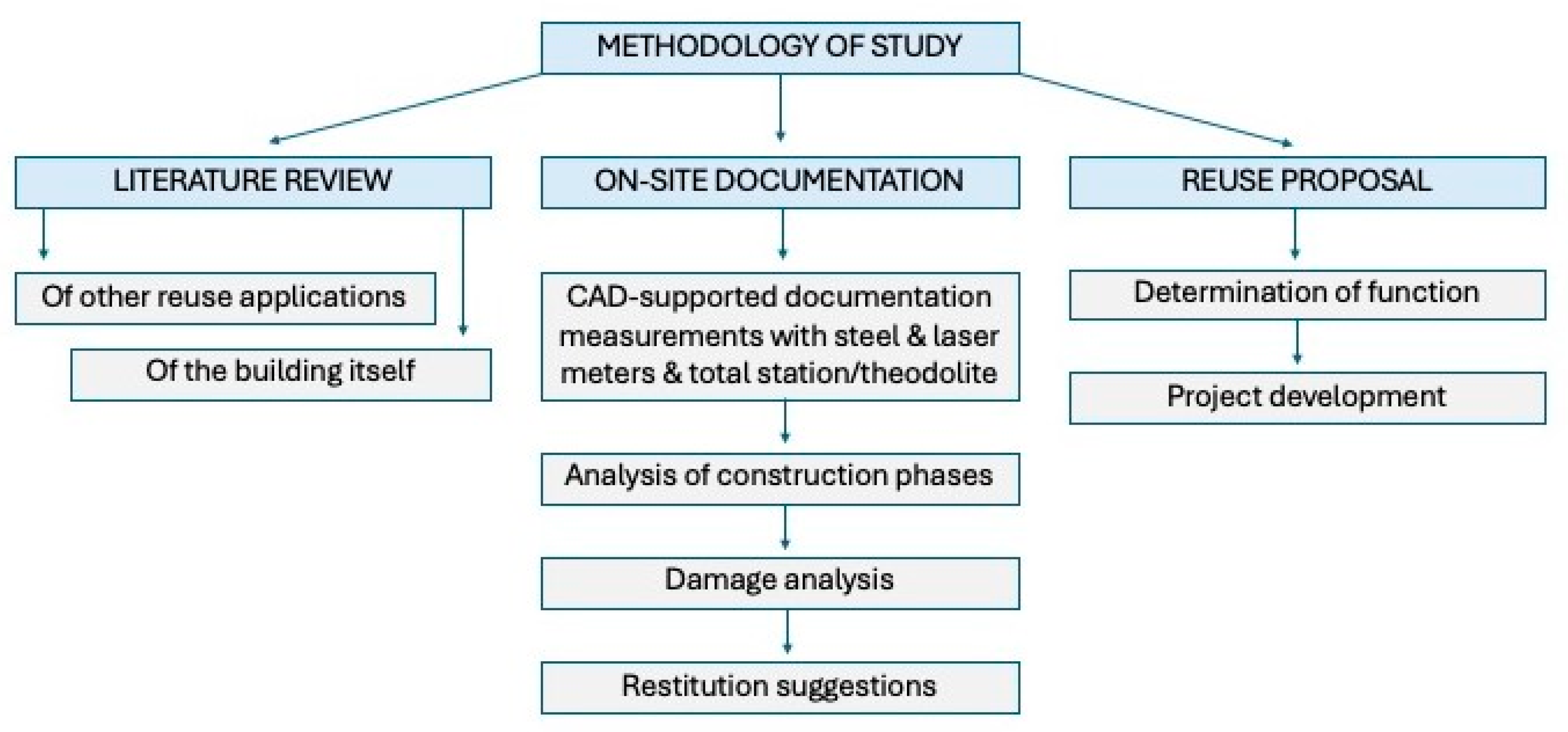

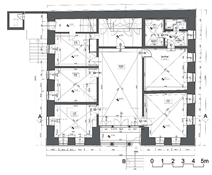

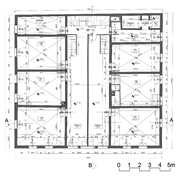

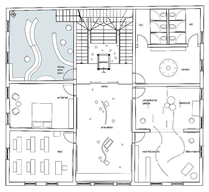

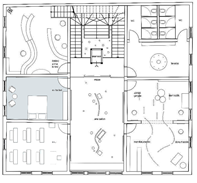

Adopting a low-cost documentation workflow, this study was conducted in three stages with its sub-sections: a literature review, on-site documentation, and a reuse proposal. The literature review can be grouped under two headings: the literature on reuse applications and on the building itself. The on-site documentation is sub-divided into documentation, analysis of construction phases, damage analysis, and restitution suggestions (

Figure 3).

The documentation consists of transferring on-site observations and measurements to CAD-supported, scaled drawings, taking all kinds of deformation into account, photographs, and damage detection studies. The measurements of the plans and sections of the four-storey building were made using steel meters and laser meters. With this method, both detailed and general cross-sectional measurements were transferred to scaled drawings in a CAD-supported working environment directly on-site in the building. Thus, the opportunity to immediately check and complete deficiencies was utilized. The height measurements of the roof and facades were carried out by geomatic engineers using total station and theodolite measurements. Damages and deteriorations were considered in the drawings, and the detected cracks and spalling were shown in the facades and sections.

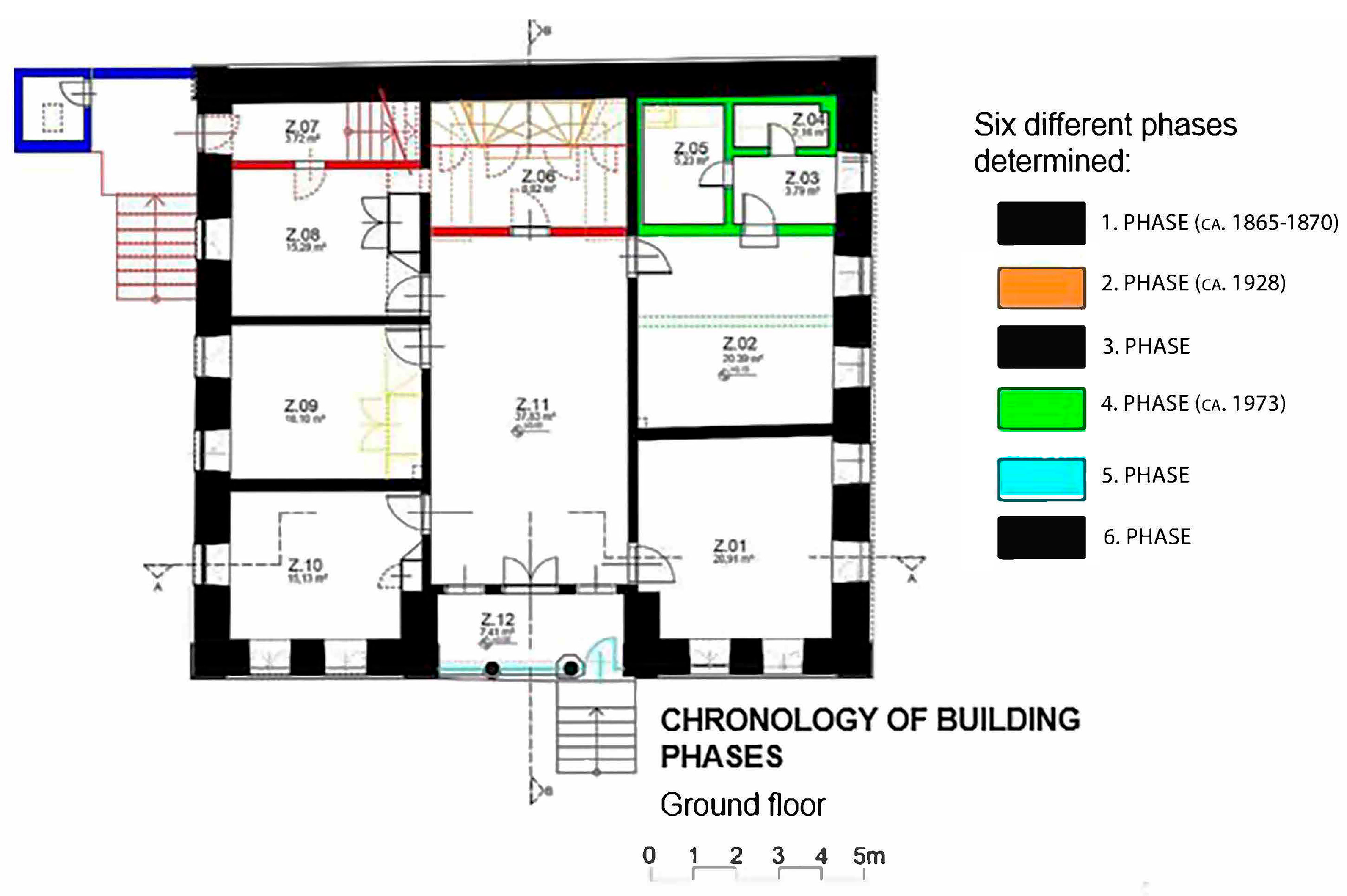

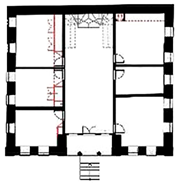

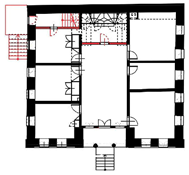

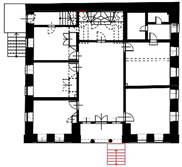

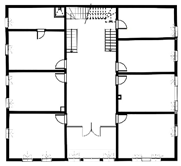

The identification of successive additions and changes to the building was a product of on-site structural survey and precise documentation. In the building, the grouts in the additions, material differences, traces on the walls, floor, and ceiling coverings were followed; in other words, the building itself was consulted, the information obtained was processed into the plans, and different phases were represented with different colours (

Figure 4). This work, i.e., the step subsequent to the surveys, also formed the basis of the restitution proposals. An academic study conducted in 1984 [

40] and written sources which provided general information about the building [

36] were put into use.

It is possible to learn from the books of Armenian and Turkish authors who reported that this building was once used as an Armenian School and that the building, like other lost assets, was among the sad memories of the Armenian community in Zara, who are extinct for long now [

35,

36,

37]. For the present-day people of Zara, although the building is mostly remembered as a mansion, the original function of the building is referred to in the narratives and this preserves its place, providing information about the past through the narratives. Nevertheless, even though there is no longer an Armenian community in Zara, the building continues to exist as a concrete witness to a reality that took place in the history of Zara, which is associated with the historical value added of the building that needs to be preserved, apart from its esthetic values.

With an esthetic value that is envied and admired from afar, the building has affected the surrounding neighbourhood with its esthetic elements and magnificent appearance. Therefore, the current, abandoned, and ramshackle appearance of a building that was once admired is considered “a source of sadness, reminding the locals of the transience of life”. This was evident from the local people’s insistence on seeing the building from the inside during our work on the building, their frequent queries about the future of the building, their description of people who once lived in the mansion as “lucky people”, and their hopeful and joyful feedback about the possibility of giving the building a future. Today, the building is still considered important to the people of Zara, as the local press frequently reports about the mansions’ alarming state of preservation and abandonment [

38]. The reason why the non-governmental organization “Green Zara”, which aimed to protect the nature, environment and culture of Zara, sought to involve academic experts from the university was associated with a feeling of regret in society, i.e., “we were not able to protect our values”, citing towns where preservation was better performed.

4. Results

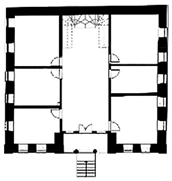

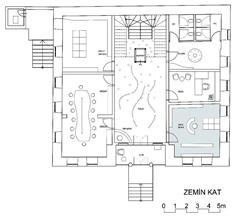

4.1. Documenting on Site: Plan Features

The ground floor, where the main entrance is located, has outside dimensions of 14.50 × 15.80 m and a central hall (or ‘sofa’ in the local tongue) plan scheme with 4.06 m high walls and rooms on both sides. While the entrance door is on one of the narrow sides of the longitudinal hall (4.62 × 8.18 m), on the opposite side remaining steps indicate an unused staircase which has not been demolished, formerly leading to the upper floor. There is only a basement floor (circa 1.98 cm high) underneath the central hall section of the building. Both sides of the basement bordered by the facades’ foundation walls are filled with soil.

The rear wall of the entrance hall with the cancelled wooden staircase which used to lead to the upper floor was later closed off by another wall with a door in the middle without blocking access to the neighbouring rooms. This space was used as a pantry. A large wooden cupboard with doors was installed on the first few steps of the wooden staircase, covering the triangular platform and Y-shaped arms of the staircase. Thus, the stairs were integrated into the cupboard instead of being demolished. Despite the limited interior of the cupboards, some smooth shelf surfaces were obtained. The wooden coating of both side arms of the staircases lower surface acts as a sloped ceiling in this space.

The entrance in the middle of the buildings’ facade leading to the hall is pulled in approximately two metres into the building, allowing for a 4.38 m long platform or portico entrance. There are two solid columns and a three-bay section with side walls aligned with the entrance hall. From this pulled-in portico entrance, a two-winged 120 cm wide door with windows on each side leads to the entrance hall.

The window openings in the thick stonemasonry walls of the ground floor have deep niches, going inward to receive more light. The niches have a 1.5 cm wide bevelling on the lower part on both sides, which rejoins after a certain height. While adding to the esthetic appearance, this detail also avoids easily damaged right-angled corners with a smooth finish and is repeated for all ground floor windows.

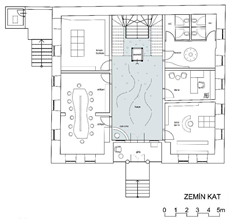

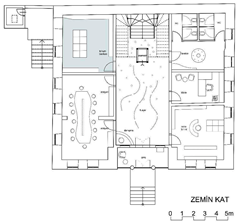

The 3.92 m high central hall on the first floor originally had the same plan scheme as the lower floor, but was later divided lengthwise into two sections so that the upper floor could be used as two separate apartments. In later arrangements, rooms are only located on one side of the entrance hall which was turned into a wide corridor. While the upper floor was first directly accessed from inside the building, an independent entrance was later provided with the conversion of the window in the southwestern corner of the ground floor into a door and by adding a staircase and platform outside. After passing a commonly used flight of stairs, the middle platform of the Y-shaped staircase is reached, with each wing of stairs providing access to two separate living units on the upper floor. In the kitchen spaces of the lower and upper floors traditional stoves were later removed, as seen from traces, different ceiling coverings and uneven wall surfaces in those parts. On both floors there are bathrooms, toilets and kitchens which seem to have been added later due to the flooring and ceiling layout.

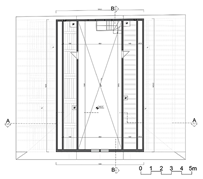

The second floor is reached by a single-armed staircase. On the second floor there is solely a central mansion room, with the roofs of the side sections located immediately above the first floor. From the way the ceiling coverings are divided and the traces on the wooden flooring, it can be understood that there used to be two rooms on the second floor. Today, the door on each of the side walls in this single space leads to an attic space beneath the adjacent roof wings.

The chimneys and stove pipe holes close to the ceiling of the ground floor and continuing across the entire upper-floor rooms indicate that the building used to be heated with a stove. In one of the upper-floor rooms, a washing basin was detected. This basin, called ‘cağ’ in the local tongue, was used by lifting wooden boards from the divan in front of the window. All these findings are recorded in the plans, sections, and facades (

Table 1).

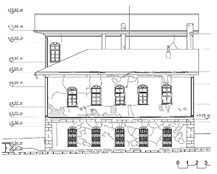

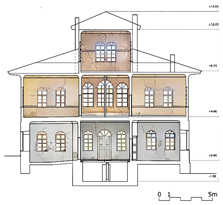

Facades

The approximately two-metre-high basement floor has an evenly cut ashlar stone wall. The ground and first floor walls are plastered and coated. Up to the first floor, the corners of the building are emphasized with evenly cut plaster-style stones standing out a few cm from the main surface. In addition, a row of cut stones and a row of wooden beams separating the upper floor from the lower floor give the facade a special framed appearance. The corners of the first- and second-floor facades are bordered by wooden posts with an ornamented surface placed on a profiled footing in the form of a column base, called ‘havadanlık’ in the local tongue.

All lower- and upper-floor windows have wooden frames with arched upper parts. The lower surface of the frame arches is covered with a row of semi-circular wooden elements (approximately 2 cm h/5 cm w), called ‘rat teeth’ in the local tongue, giving an ornamented, esthetic appearance. With its symmetrical layout the entrance facade (northeast) is the most distinctive facade of the building. The main entrance is located on the ground floor in the middle of the northeastern facade of the mansion (

Figure 5). The additional basement floor acts as a socle. The entrance has an arcaded layout consisting of two columns and three arches aligned with the facade. In accordance with the wider middle section, the arch above the entrance door is higher.

This pattern of a larger arched window in the middle and two smaller ones on each side repeats on the first floor. In accordance with the symmetrical plan scheme, there are two lower arched windows on both sides of the entrance. This is also repeated on the first floor. While the windows on the upper floors do not have iron grilles, the windows on the ground floor have richly ornamented iron grilles aligned with the facade surface.

The window arrangement of the mansion room on the second floor consists of two identical conjoined windows with arches. A windscreen structure made of metal and glass was later added between the column gaps of the porticoed entrance to protect from weather conditions. This intervention partially changed the exterior appearance of the building.

Due to the rise in the road level over time, some of the socles on the northwestern facade remained below the ground and the parapet heights of the ground floor windows decreased. Each room has one or two corresponding windows. While the number of windows on the northwestern facade differs according to the size of the room, they are all the same type in terms of height and width (

Figure 6). Some of the two-winged window frames on the ground floor were interchanged to one fixed and one openable winged frame. Wooden panels were nailed over the arched upper parts of these windows. While the windows of the ground and first floors are aligned and same in number, the number of rooms on both floors is different. The mansion room on the second floor has one arched window on the northwestern facade, the parapet of which coincides with the roof below.

The southwestern facade is at the rear of the building. Differing from the others in character, this facade has a blank surface, other than two windows of the mansion room on the second floor. Apart from that, it consists of the same wall structure as the other facades (

Figure 7).

The southeastern facade is the facade with the greatest differences from its original state, as the window located at the end of the entrance on the ground floor was later converted into a door to provide a separate entrance to the upper floor. In contrast to the general appearance of the building, the conversion of the window into a door and the addition of a concrete staircase presents a rather haphazard appearance. The windows lined up on the long side of the hall are all the same size on the ground and upper floors. Here too, they do not show any difference in relation to the rooms behind them. However, the windows on the southeastern facade of the ground floor have plain, undecorated iron grilles directly mounted to the window frame, slightly inward from the facade surface. There are no iron grilles on the windows of the upper floors on this facade either.

A profiled element with a convex section forms the transition from the facades’ smooth surface to the wide eave roof. This surface is also plastered in the same style as a continuation of the facade. At the end of this, the wooden cladding of the roof cornice begins. Forming the highest part of the facade, the pediment hipped roof has rich wooden profiles with ornamentation in places. Although there are damages in this section such as shedding and deterioration today, it is possible to follow the establishment system (see

Table 1).

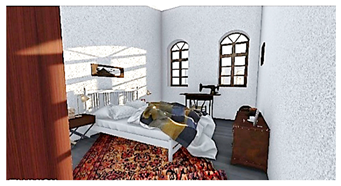

The building offers a perspective to the past not only by its physical, esthetic form but also by the intangible memories or genius loci of interiors and exteriors. For instance, the double-columned, arcaded, and arched entrance and high spaces, which are not available in other contemporaneous residences in Zara, are suggestive of the characteristics of a magnificent school building (

Figure 5), where the “lamp stands”—the stationary architectural elements and interior fittings at the chest level on one of the walls of each of the interior spaces in the form of small semicircular and elliptical projections made of plaster, where means of lighting, including gas lamps and candles, were placed—provide some evidence of how lighting needs were resolved when grid power was not used (

Figure 8). The historical fireplaces, now visible by their traces on the wooden siding on the walls and ceiling, narrate the story of the evolution of heating and cooking, and are indicative of the focal point of the family’s life. The fixed closets with lids in the rooms suggest that beds were taken out during nighttime and laid on the floor and picked up during the day and stored in these closets. The “cağs” or drainage holes located at one end of the wooden couches that are still visible in some rooms indicate how washing and bathing were performed (

Figure 9). The fine wrought iron lattices of the ground floor windows serve as evidence of the technical and esthetic level accomplished by the blacksmithing art once famous in Zara (

Table 1). Therefore, each of these details must be taken into consideration in reuse and passed on to future generations.

4.2. Building Technique and Materials

The basement floor made of even ashlar stone walls also serves as a podium for the ground floor. In contrast to the masonry of the basement walls, the ground floor wall consists of rubble stone masonry and mortar, varying in thickness between 80 and 87 cm. The first-floor wall rises on top with a traditional timber frame structure. The corners of the ground floor are strengthened with evenly cut stones in a plaster style. The previously described row of ashlar stones additionally emphasizes the border between the ground floor and the first floor on the facade. While the ashlar stone walls are presented in their bare form, the rubble stone walls are covered with plaster and coated.

The inner walls of the ground floor and the inner and outer walls of the upper floor have an approximately 20 cm thick masonry wall structure with crushed stone and lime mortar used in between. Having been frequently used in the region, the timber frame technique consists of wooden posts spaced 40–50 cm apart, filled with a mixture of subsequently plastered crushed stone and lime mortar. The stone masonry technique of the ground floor, as well as the timber frame technique of the first and second floor, is clearly visible due to the peeling on the southwestern rear facade.

In the three-bay section of the arcaded main entrance on the ground floor, the two solid columns have a wider distance of 145/220 + 70 cm than both side openings with 110/200 + 75 cm dimensions. As mentioned above, the middle section has higher arches than the ones on the sides. The single-centred semi-circular arches are made of cut stone finishing in line with the plastered wall structure. The springing line of the arches are connected to each other with thin steel rods. In subsequent stages, the profiles of the metal–glass structure used for the later added windscreen were aligned with the springing line of the arches.

Wooden posts of approximately 16/20/175 cm are placed in a longitudinal row on a stone base measuring 25/20/20 cm throughout the middle of the basement. The latitudinal posts carry approximately 15 cm high wooden beams, supporting the ground floor of the entrance hall. The wooden beams of the ground floor rest on a 20 cm wide step along the longitudinal walls of the interior side of the basement wall. The few cm thick floor planks are placed on these beams. Apart from this construction, there is no soil filling or mortar in the flooring.

The roof construction of the building consists of wooden posts and rafters covered with mission tiles. In the rooms, the white plastered walls’ transition to the wooden ceiling is provided with a coated concave profile. Profiled wooden slats are used at the joints of the equally wide wooden boards covering the ceiling. The transition from the facade surface to the roof is provided with a plastered concave profile. The surface of the wooden roof eaves is partly covered with ornaments.

The iron grilles of the windows on the ground floor reflect the local Armenian blacksmiths’ skills and their high esthetic taste. The solid wooden doors, all equal in size, are a harbinger of standardization.

4.3. Condition of the Building

The building has not been in use for quarter of a century. The 60 cm thick stone walls make the ground floor quite cool and humid, even in summer. Regular ventilation is not provided due to its disuse. Furthermore, the arms of an old stream bed (Pirek—“pur ag” in Armenian) passing under the building has caused water accumulation in the basement in recent years, causing great damage to the building. Additionally, the wooden flooring of the ground floor is covered with PVC, preventing the wood from getting air. This led to the load-bearing wooden structure between the ground floor and the basement to completely rot, making it risky to inhabit. Before the building can be used again, the problems caused by the running water source must be solved urgently and definitively. A similar problem is also experienced in the building opposite on Aydınlar Street, where the residents occasionally discharge the water in the basement of their building directly onto the street with electric motor power. The water sprayed onto the street flows directly towards the historical mansion and is directed to a water channel very close to it, which exposes it to an intense water spray every time. Hence, the source of the water should be identified and connected to the city sewer. Comprehensive static precautions like this must be taken for the flooring of the ground floor. Due to the moisture rising from the ground floor, the plasters of the thick ground floor walls, especially on the north-western Aydınlar Street side, have large-scale swellings, flaking, freckling and mould.

In almost all rooms facing southeast approximately 50 cm long cracks have occurred in the same location close to the ceiling slab a while ago. The fact that they are in the same location and repeated suggests the effects of a seismic movement, such as an earthquake. The toilets and water installations on the ground floor are faulty and cannot be used. Due to the bursting and overflowing of a toilet pipe, the floor in the kitchen and bathroom is filled with mud. The damaged plumbing system has been left unrepaired.

The original state of the facades has been largely preserved, except for some damages such as cracks or plaster peeling. The minor renovations on the facades were made with materials that do not suit the ashlar stone appearance of the building, such as cement and concrete, and have thus damaged the esthetic appearance. The most damaged facade is the southwestern or rear facade of the building, which is rather difficult to reach today. There has been plaster peeling in large areas here, giving the opportunity to identify the construction technique of the building. Being the highest part of the facade, the roof of the triangular pediment is formed of partly ornamented rich wooden profiles. Although today these ornamentations partially show peeling and deterioration, its principle of creation can still be traced.

As mentioned above, some of the ground floor windows have been replaced with “modern” window sashes that have different divisions than the original. The semicircular upper parts of the arched windows have been replaced with simple boards. Many windows are broken or missing and their joineries have aged. The parts of the chimneys that extend above the roof show flaking. The damages identified inside the building have been systematically displayed in a separate form created for each room. Along with photographs of the space, these findings have been noted for evaluation.

4.4. Building Phases

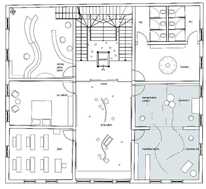

In the next stage following the analytical survey and the chronology of the building phases (

Figure 6) the restitution of the building phases was proposed. Six construction and modification phases of various sizes were identified for the historical building (

Table 2).

Ground Floor

The ground floor has six rooms, three on each side of the central hall. The middle room on the northwestern side, however, is rather small. With two windows on the front and one on each side facade, the rooms next to the front door are the largest (4.58 × 4.78 m) and brightest ones. The doors of all rooms open from the corner, allowing furniture to be placed on the remaining part of the wall. The approximately 2 m high doors are adjacent to a wooden band starting at approximately 210 cm, running across the entire room. As in other mansions, the basement floor of this building was generally used as a wood and coal storage.

In the second phase, the parapet of one of the ground floor’s corner windows on the southeastern facade was demolished and converted into a door opening leading onto the platform of a staircase added from the outside, starting on the ground floor level. This new entrance was added to make the upper floor independent from the ground floor residence. The rear part of this modified room was separated by a “new” wall, creating an approximately 130 cm wide corridor. Another door in the middle of this wall connects the now independent residences with each other and makes it possible to also reach the upper floor from inside the building.

In the fourth phase, the wall between two of the ground floor rooms on the northwestern side was demolished in 1973 [

40]. Combining the two spaces, a kitchen with a counter was built here. The wood-burning kitchen stoves and their chimneys were cancelled. Instead, a bathroom, toilet and sink were added. The new wall separating the bathroom-toilet section from the kitchen coincided with one of the windows and somewhat narrowed the window space. In the section arranged as the kitchen, the floor was raised one step compared to the entrance hall. The floor in the bathroom-toilet section was also raised one step compared to the kitchen. Additionally, a suspended ceiling was built in the bathroom to make it easier to heat. This section appears just as a “house within a house”.

In the unit on the southeastern side of the upper floor, the traces of the removed stove are clearly visible from the rough and uneven surfaces of the wall and the interrupted ceiling covering. The previous existence of a wall removed to connect the two spaces in the current kitchen is also clearly detectable from the interrupted ceiling covering in this part. The door opening to the hall from the room that was cancelled for the kitchen was covered by brickwork. Quite neatly covered with plaster, this change can only be detected by carefully looking for the need for a door here, as well as from the joints in the wooden moulding continued at the same height as the lintel of the door and the cracks in the wall plaster along both sides of the door.

In the fifth phase around 1983 [

40] the centrally located stairs of the vestibule-style entrance of the ground floor were moved to the side. The entrance of the ground floor was covered with a metal–glass structure in this phase to create a windscreen. This intervention was certainly made as a precaution against weather conditions, but at the same time the changing perception in society to not enter the house with shoes also played a role. Lastly, a toilet for one of the upper-floor residences was added next to the platform of the external staircase on the ground floor in the late phases (see

Table 2).

On the first floor the winding steps from the middle platform of the Y-shaped staircase were cancelled in the second phase. Instead, the same number of straight steps was added to reach the first floor. In the first phase there was a glass-paned section on the first floor at the end of the hall facing the front facade. Later, this glass-paned section was removed by dividing the hall in two lengthwise from the middle, and a divan was built in front of the glass. Following this, the stove on the northwestern side of the house was cancelled and a bathroom-toilet was added. On the southwestern side, on the other hand, the door between the kitchen and the room was closed, creating an independent space. In addition, the stove in the kitchen was cancelled. Traces of the stove can be followed on the wall and the ceiling plan of this floor.

In the first phase, the mansion room of the second floor was probably divided in two. The existence of a partition wall in this section is apparent from the change in the wooden coverings of the floor and the interrupted wooden ceiling covering. Later, this partition was removed and turned into a single space (see

Table 2).

4.5. ReUse and Restoration Proposal

Analysis based on field studies and stakeholder consultation suggested that the repair and reuse of the preserved building was financially beyond the ability of the property owners alone. In addition, the number of heirs of the property owners, already a large family, has increased to such an extent that the existing building capacity could not provide housing for everyone.

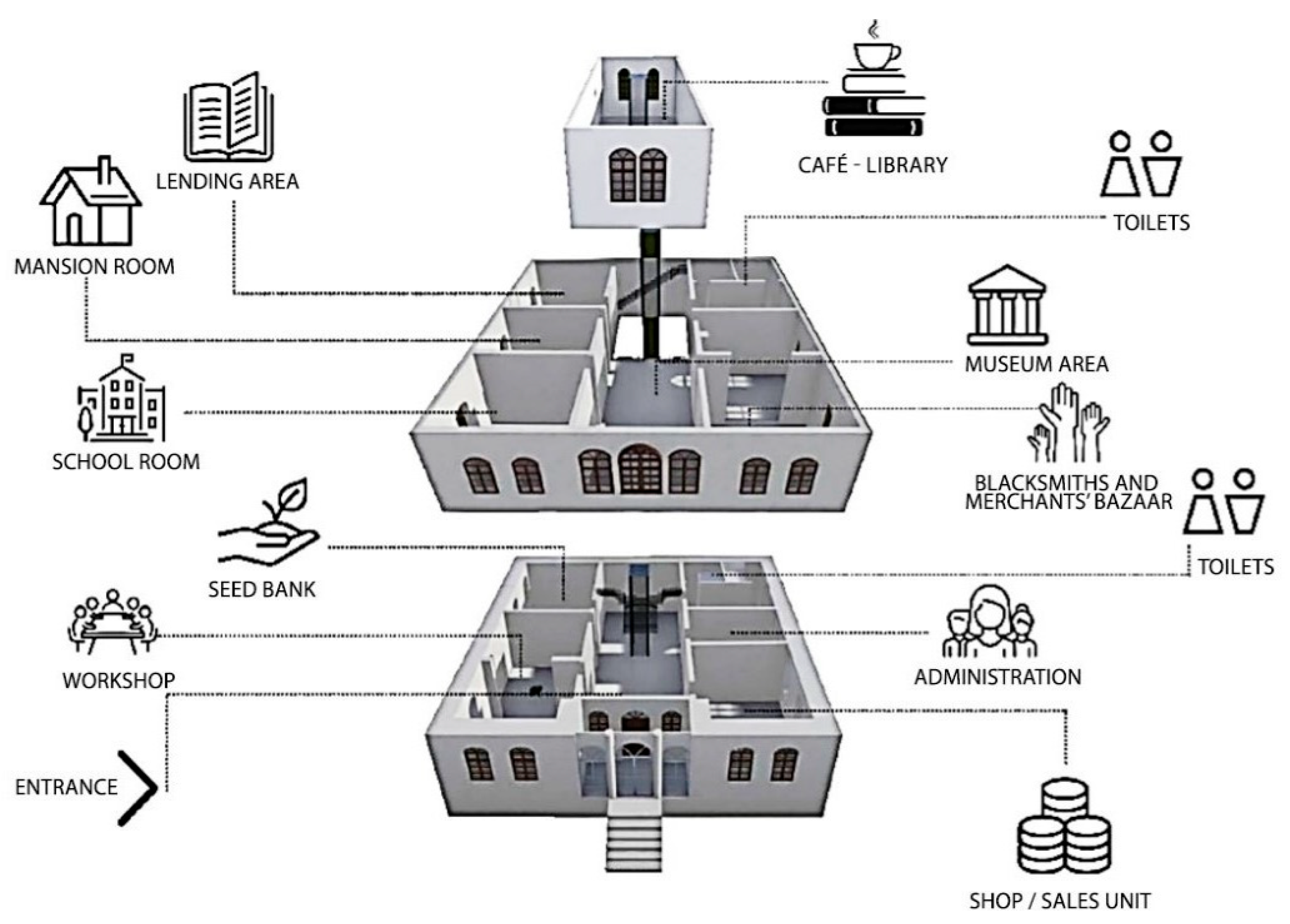

Given that government support for preservation practices was typically very limited and therefore not encouraging, public support and broad participation were required for financing purposes, which do not have to be limited to the funds raised by property owners. Therefore, based on the idea that the first use of the building should be public use, an investment which can accommodate public use that would benefit all has been evaluated as an alternative. On the other hand, since there was no museum in Zara, which had a population of approximately 20,000 and a very old establishment history, which was considered a need by the local population, a usage proposal was introduced, namely a non-consumption-oriented place where especially young people and school-age children could visit and gain cultural knowledge (workshops, open exhibition, café-book section). The central location of the building was also one of the evaluation criteria in selecting its future function. Today, museums have their concepts expanded in line with the expectations of societies and focused on making free time enjoyable and educational. Accordingly, a programme was adopted which would transform the building into an “urban memory museum” combining the functions of an exhibition, workshop, seed bank, library and café. Therefore, the adaptive reuse of the building was positioned as a tool to preserve the tangible and intangible cultural heritage while providing socio-economic value to the local community.

The decision also considered how this adaptive reuse strategy would not only preserve the building but also preserve and enhance local skills and the cultural identity of the local community and create an economic opportunity for the local community. It was contemplated that this application, which was the first of its kind in Zara, could serve as an example for other projects in the future and suggest how such an application could become a catalyst for the integrated cultural heritage and sustainable development of the region.

Even the onset of research and project preparations for the building in question led to new and hopeful dreams. For example, it was dreamed to turn the Hacı Usta Mansion, which once had a large, famous and productive garden on the banks of the Kızılırmak River, into an applied agriculture-vocational high school, and the Sıtkı Şenol Mansion, featuring a twin-mansion form, into a mansion-boarding house.

Since it is registered as second degree historical building, changes suitable for its new function can be made inside the building without making any changes to the exterior, according to the current national preservation laws. The buildings registered as 2nd degree pursuant to the resolution No. 660 of the Supreme Board for the Protection of Cultural and Natural Assets of the Ministry of Culture in 1999 are considered examples of civil architecture that contribute to the identity of the city and the environment and reflect the architectural features and local lifestyle of a certain period. For these buildings, modifications required for the interior arrangement of daily life can be made without altering the load-bearing system and decorations [

41].

Especially regarding the practice across the disadvantaged regions of Europe, such historical buildings are evaluated as museums or as part of an open-air museum and serve as catalysts as a means of keeping the culture in rural areas up to date. Examples include Belarusian State Museum of Vernacular Architecture, Vysočina Open Air Museum or Museum of Vernacular Architecture of Western Serbia and Eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina [

42].

These approaches were also supported by the “Convention on Intangible Heritage” signed by UNESCO in 2003 [

43] on practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills, related tools, materials and cultural places. Another example is the Museum in the Village, Portugal project, a cultural programme for people aged over 65 years living in rural areas with limited access to cultural activities and events and received the Europa Nostra Citizens Engagement and Awareness-raising award in 2022 [

44]. The museum in Zara could accommodate a similar use: For example, the seed bank in the programme can help enable farmers from surrounding villages to come to the museum and interact with the cultural life in the city, as well as other creative meetings.

While on one hand, the new function aims to remind of the building’s original identity as a school and its long-term use as a mansion, on the other hand, it seeks to emphasize the building’s construction technique details of the period by documenting and presenting production methods (agriculture, blacksmiths, drapers, carpet and kilim weaving) that have been lost due to rapid urbanization.

A sales stand where natural local products typical for the area are marketed

A seed bank where local seeds are stored and preserved

A temporary, open exhibition area for local handicrafts

Workshop area enabling creative, cultural and innovative activities

An administration unit

Permanent exhibition/museum area

- 6.1.

Exhibition of objects related to the town’s memory

- 6.2.

Textile merchants, blacksmiths’ bazaar, weaving looms; on the towns’ socio-economic history

- 6.3.

Memory of the building regarding its usage history

- 6.3.1.

School markets

- 6.3.2.

Mansion markets

Library, book lending service

Cafe, library

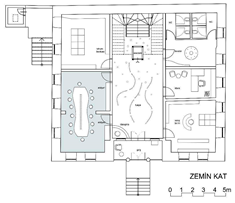

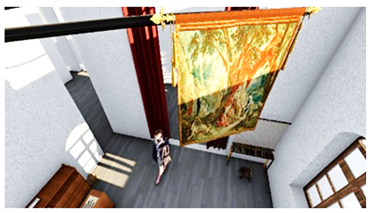

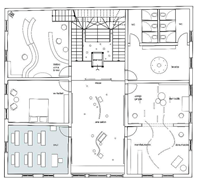

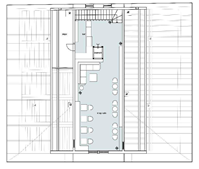

For the ground floor of the re-functioned building a souvenir sales unit, an exhibition area, educational workshops, a seed bank and administration were proposed, ensuring an open access to the entrance area for everyone (

Table 3).

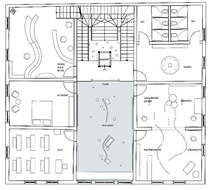

On the first floor the ticketed museum area offers a special focus on the past uses of the building, as well as the town’s historical memory. This includes the proposal of school, mansion and exhibition rooms with attributes of important historical characters for the town’s memory, the exhibition of regional productions (weaving, rag doll making) hanging from the ceiling, a blacksmiths’ and drapers’ market and exhibition-workshops on weaving (

Table 4).

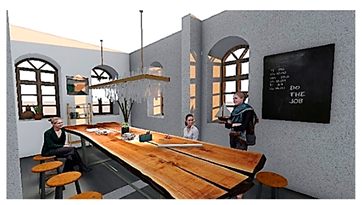

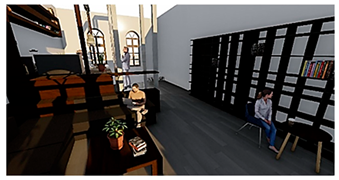

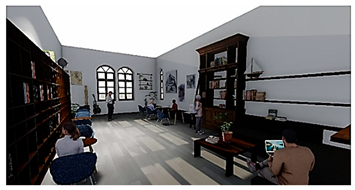

Today’s museum concepts often include small-scale gift shops, consumption-based meeting spaces to spend time before and after the museum visit. Since these social elements tend to encourage museum visits, a book lending area on the first floor and the “mansion room” on the second floor, which was the most valuable space in the building’s past, are suggested to be used as a café and library where the young people of the area can socialize and read books, in addition to the shopping opportunity on the ground floor. In this space meetings can be held or books can be read while drinking coffee. Books can either be obtained from the lending area on the first floor or the shelves on the second floor. Furthermore, the higher parts of one of the attics on each side of the space are suggested to be used as service and storage areas (

Table 5).

A reconstruction of the still existent, previously cancelled staircase from the first building phase in accordance with the original but with today’s technology and materials is proposed in order to increase accessibility. Additionally, an elevator could be added to the central space of the staircase, preserving its original configuration.

It is further proposed to recover or repair the damaged parts of the building’s hipped roof on the main facade with original coatings that characterize the construction style of the period.

5. Discussion

The focus of this study was to understand, identify, and document the changes a historical building went through based on the data that survived to the present day and the traces that could be recognized on the building, as well as to seek ways to ensure that the building would maintain an honourable existence in societal life in the future. Accordingly, the reuse approach and the theories and relevant international practices were investigated. The complexity of the issue is accompanied by multidimensional contradictions: One of the primary aspects is that property owners, who have inherited historic buildings, are faced with multiple complex problems which they cannot handle alone. On the one hand, the number of property owners for a given property has increased, each of them holding a different perspective, expectation, and approach to inheritance. While some take it emotionally, others may adopt more materialistic approaches. The inadequate level of incentives made available by the government for the preservation and repair of historical buildings and lack of guidance for property owners creates a problematic situation, also complicated by the fact that property owners cannot take their desired initiative. Most heirs perceive owning such buildings as a misfortune rather than a chance, especially if they are historical buildings that have been registered and protected by the authorized institutions of the government. This is associated with an alienation between the building and the property owner. As in the example in question, the owners approach, i.e., “this is a registered building, I should not touch it” even in the case of acute maintenance problems of the building, has accelerated the destructive process of the building.

Convincing property owners that the shared inheritance notion is associated with shared responsibility and “liberating them from a feeling of being in need of others’ help” requires a separate persuasion process. Accordingly, for the cultural heritage buildings, which are considered as the common heritage of humanity, envisioning public use and including public and ensuring its contribution to every stage of reuse can be a solution. Nevertheless, the acceptance of foregoing is a psychological barrier which the property owners must overcome. As such, historical building research, documentation, and the quest for solutions for reuse practices by universities or relevant educational institutions within the scope of a research project is a contribution and provides a guide for property owners. Putting a good example in place can accelerate the process for other projects waiting in line. Nevertheless, an appropriate new function (reuse) must be selected for each building based on its location, state of preservation, and structural characteristics, and to meet a perceived need in society. A reuse approach which can preserve not only the physical features of the building but also its intangible values can prove to be a solution for the reintegration of these historical buildings, which are considered in danger of extinction and are a source of sadness for all segments of society. Considerable progress has been made regarding the aforementioned issues in this example, and the property owner, local people, civil society organizations, local media, and government officials gathered in various meetings and picnics prior to and during work to exchange ideas.

The decision-making processes for property owners and stakeholders may vary when evaluating issues related to the reuse and preservation of cultural heritage. Thus, a working model interpreting the approaches of stakeholders involved in the decision-making process was adopted. Before commencing the study and during the process, the property owner, locals, civil society organizations, local media and government officials came together in various meetings and picnics to exchange ideas.

In light of all information and knowledge available, the proposed urban memory museum is designed in accordance with contemporary life and user needs, differing from classical museum typologies which only include exhibition activities. At the same time, the lack of spaces combining education and entertainment for the public and young people added to a preference for this function.

The studies’ future effects are presumed to be as follows:

It can act as a model for more reuse strategies of historical buildings.

As in this study, the involvement of a non-governmental organization in the process, aiming to protect cultural heritage rather than targeting economic interests and mediating the property owners’, planners’ and local peoples’ demands, can bring the encouraging and guiding role of such organizations in reuse applications to the agenda. For example, The Aga Khan Foundation for Culture (AKTC), which encourages discussions on the importance of the built environment, cultural heritage and historical memory, offered examples and solutions for contemporary design problems, and achieved success worldwide, demonstrating the power and importance of civil society organizations [

45]. It is obvious that there is a requirement for more civil society organizations to keep cultural assets alive across the globe.

The relationships, support, and exchange fostered between the guest students and the locals during the projects’ research and development process can be an example for the development of appropriate protection strategies for similar examples.

The documentation was carried out as an interdisciplinary study by experts in protection and documentation, students, and surveying engineers. Following the documentation studies, the students had the chance to learn by performing and experiencing all stages of the development of a reuse project.

6. Conclusions

Today, the original identity of buildings can barely be preserved, while new qualified and meaningful identities are barely created, which fills cities with low-quality and relatively short-lived buildings especially in areas of gentrification. The re-purposing of a historical building can be a strong strategy to cope with such fast change and transformation. In fact, it is increasingly accepted that the preservation of cultural heritage through adaptive reuse provides economic, cultural, and social benefits to society.

The decision of whether a building can be reused depends on a complex set of issues such as location, heritage, architectural assets, and market trends. During the study, it was observed that even property owners with historically registered works were hesitant to touch protected buildings. On one hand, the state’s conservation boards were observed to have a rather frightening and off-putting attitude, rather than an encouraging one. On the other hand, it was observed that seeing historical mansions in ruins is a matter that upsets the towns’ residents. This shows that these mansions have a place in peoples’ memory and an emotional bond has been established. Since this cultural and social responsibility cannot be left to the property owners alone in terms of its economic dimension, financial resources are needed. If historical buildings are a common heritage of humanity, protecting them is also a common responsibility. This approach led to the choice of a public function for the re-purposing of the historical building. Public use can make this task easier to undertake.

As a result, this study aims to show that preserving a historical building through adaptive reuse and keeping the memory of that building and the city alive can contribute to a more sustainable urban environment. This reuse project aims to ensure the protection of cultural heritage, increasing the quality of local life by preserving its identity, diversity, and liveliness, while keeping the buildings’ identity alive. Lastly, this project helps develop collective responsibility by strengthening social action and participation, enabling locals to take ownership of the building with its new function.