1. Introduction

Heritage and resilience are increasingly recognized as interdependent pillars in post-conflict recovery. Heritage extends beyond physical monuments to include collective identities and intangible traditions, while resilience describes a system’s ability to absorb shocks and recover sustainably [

1,

2,

3], especially in post-conflict settings [

4]. In global scholarship, the convergence of these themes highlights how cultural assets can catalyze psychological healing, economic renewal, and community cohesion in post-crisis settings. Heritage encompasses not only material structures and monuments but also the cultural practices, traditions, and collective identities that bind communities together [

4,

5]. Resilience illustrates the potential of social, cultural, and urban systems to endure challenges, modify, and rearrange themselves while upholding their key roles [

6,

7]. Contemporary global research underscores that the preservation of cultural heritage encompasses not merely the protection of tangible assets but also the promotion of social cohesion, psychological recovery, and sustainable economic stability [

8]. This nexus between heritage and resilience has become a critical focus in post-disaster and post-conflict research [

9,

10], where cultural assets serve as both symbols of continuity and drivers of recovery [

11,

12].

Syria’s prolonged civil conflict has devastated numerous UNESCO-listed sites, displaced communities and disrupting socio-economic networks. While international frameworks outline models for heritage protection, there remains a critical gap: few studies assess the integrated role of cultural heritage and resilience from the perspective of local actors in Syrian cities [

13]. Much of the literature remains compartmentalized, focusing separately on tourism, physical restoration, or humanitarian aid, thus failing to capture the complex intersections among cultural identity, inclusive governance, and sustainable development [

14,

15,

16].

This study fills this gap by exploring how heritage preservation can be leveraged as a driver for long-term resilience in historic Syrian cities. Drawing on fieldwork, stakeholder interviews, and surveys, the research offers practical strategies that link cultural heritage to inclusive recovery, sustainable tourism, and socio-economic revitalization. Utilizing a combination of theoretical frameworks and original empirical evidence (incorporating surveys and interviews), the study aspires to generate pragmatic insights that integrate the cultural, social, and economic facets of reconstruction. This research is particularly focused on exploring the primary challenges and impediments affecting the sustainable renewal of historic cities in Syria, with a concentration on cultural, social, political, and economic elements. It further seeks to evaluate how heritage preservation can be integrated into resilience-building strategies that promote long-term community stability and well-being. Moreover, the study investigates the roles and interactions of governmental, social, and economic actors in shaping heritage-led recovery efforts, aiming to propose evidence-based, context-sensitive strategies that balance cultural preservation with sustainable tourism and economic revitalization. To guide this inquiry, the following core research questions are addressed:

What are the main challenges facing cultural heritage preservation in post-war Syrian cities?

How can tourism investment support economic and social resilience while safeguarding cultural identity?

What roles do governmental, social, and economic actors play in ensuring balanced and sustainable reconstruction?

What field-based strategies can effectively balance heritage conservation with economic development in the Syrian context?

This research stands out by integrating local stakeholder perspectives with theoretical frameworks to develop a holistic understanding of heritage and resilience in post-war Syria. The study’s contribution lies in linking theory with empirical findings to develop a context-sensitive framework for heritage-led urban resilience. This integration positions cultural heritage not merely as a site of memory, but as a strategic asset for rebuilding inclusive, adaptive, and economically viable post-conflict cities. It introduces original field data, including quantitative survey findings and qualitative interview insights, to map the interconnections between cultural preservation, governance, community involvement, and economic revitalization. By doing so, it not only addresses a notable gap in the existing literature but also provides practical recommendations aligned with international sustainability goals, including the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 11) and UNESCO’s heritage conservation mandates. To conclude, this research outlines a widely applicable framework for engaging with cultural heritage as a primary force for driving sustainable and resilient urban transformation in settings affected by post-conflict challenges.

This literature review is structured thematically to illuminate how post-conflict recovery strategies have addressed the intersection of cultural heritage and urban resilience. Four core themes frame this discussion: (1) global case studies of post-conflict heritage recovery, (2) the impacts of conflict on cultural heritage, (3) strategic approaches to post-war urban redevelopment, and (4) scholarship specifically addressing Syrian historical cities. The critical comparison across these categories enables a deeper understanding of transferable models, gaps in knowledge, and how global practices can inform Syria’s path forward.

2. Literature Review

The 1954 Hague Convention for the Safeguarding of Cultural Property in the Context of Armed Hostilities represents a pivotal international accord that concerns the preservation of cultural heritage amidst wartime circumstances. The Convention delineates regulations and foundational principles for the safeguarding of cultural heritage, encompassing structures, monuments, artworks, and archeological sites, amidst the context of armed conflict. The text convention states “any damage to cultural property, irrespective of the people it belongs to, is a damage to the cultural heritage of all humanity, because every people contributes to the world’s culture” [

17]. The Convention mandates that state parties implement strategies aimed at averting the obliteration of cultural heritage and safeguarding it against acts of looting and theft. It also obligates state parties to mark cultural property with distinctive emblems and to respect such emblems when displayed during armed conflict.

In conjunction with the 1954 Hague Convention, there exist two supplementary protocols, which were ratified in 1954 and 1999, respectively, that enhance and fortify the protective measures delineated in the Convention. The 1999 Protocol, in particular, broadens the ambit of the Convention to encompass non-international armed conflicts and to afford augmented safeguarding for cultural heritage [

18]. The 1954 Hague Convention and its associated protocols establish a significant framework for the safeguarding of cultural heritage amidst armed conflict, and it is imperative for nations to ratify and execute these instruments to guarantee the conservation of our collective cultural heritage.

Throughout human history, the destruction of heritage and cultural sites has been a problem [

19]. In the past, wars and conflicts have caused significant destruction or vandalism of these sites [

20]. In contemporary discourse, there has been an augmented focus on the conservation of heritage and cultural landmarks in order to facilitate tourism and stimulate economic development. Numerous scholarly investigations [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25] have scrutinized the impact of warfare on cultural and historical landmarks, emphasizing the critical necessity of safeguarding these sites amid conflicts to avert irreversible harm and the erosion of cultural heritage. Additionally, efforts to restore and preserve damaged sites can also contribute to post-war economic recovery through tourism. During the Second World War, numerous European urban centers experienced extensive destruction as a consequence of aerial bombardments and military presence, as indicated by a study conducted by Kostof [

26]. The aftermath led to the obliteration of countless cherished architectural treasures and landmarks, alongside the displacement of many families from the sanctity of their dwellings. Similarly, Hirsch [

27] unearthed the grim reality that throughout the tumultuous Bosnian War of the 1990s, a multitude of cultural treasures were either ravaged or severely harmed by bombardments and various acts of warfare.

The evolution of conflict-ridden areas is an intricate and layered endeavor that demands a deep comprehension of the socio-political, economic, and cultural landscapes [

28]. In this particular context, resilience holds significant relevance as it underscores the capacity of a system, community, or individual to rebound from disturbances and pressures, adjust to evolving circumstances, and undergo transformations that enhance their overall welfare [

29].

In the context of historical Syrian urban centers, the aftermath of conflict presents a unique opportunity to fortify resilience by confronting the fundamental drivers of discord, including social inequity, political turbulence, and economic disenfranchisement. This objective can be realized through the execution of inclusive development initiatives that foster social unity, empower disadvantaged populations, and cultivate avenues for collective prosperity [

30].

Another relevant theoretical concept is “peacebuilding,” which focuses on the processes and structures required to prevent violence and promote long-term peace. Tackling the fundamental origins of discord, promoting the process of reconciliation, and enabling the reintegration of displaced communities constitute essential components of this initiative [

31]. For historic Syrian cities, this may entail restoring cultural heritage to foster a sense of shared identity and belonging and supporting social and economic initiatives that promote stability and growth.

The investigation of the ramifications of armed conflict on heritage and cultural sites has constituted a principal emphasis of this research, aimed at comprehending the methodologies through which these sites can be conserved following the conclusion of hostilities. A plethora of scholarly inquiries regarding this subject has been undertaken globally, with a notable concentration on the situation in Syria. This review can provide valuable lessons for other war-torn cities, assisting them in finding effective solutions for preserving historic sites and protecting their cultural heritage and how to employ tourism investment in historic cities.

2.1. Global Case Studies of Post-Conflict Heritage Recovery

Post-war heritage development pertains to the systematic endeavor of reconstructing and rehabilitating cultural heritage sites and edifices that have sustained damage or destruction as a consequence of armed conflict. The process incorporates diverse actions, like assessing and cataloging damage and the reconstruction and rehabilitation of impacted sites and facilities, in addition to designing policies and plans aimed at sustainable heritage conservation. The significance of post-war heritage development extends beyond the mere preservation of cultural heritage; it is also instrumental in facilitating social and economic revitalization within regions afflicted by conflict. It can be beneficial in enticing travelers, establishing work prospects, and encouraging local engagement and empowerment.

A notable transformation has occurred in the perception of urban environments, particularly regarding their cultural identities and their viability as destinations for tourism investment [

32]. This literature review aims to investigate the methodologies employed by historic cities in response to these shifts, as well as their efforts to maintain cultural integrity while capitalizing on the prospects presented by tourism investment. The initial article under consideration is “Using Cultural Heritage as a Tool in Post-war Recovery: Assessing the Impact of Heritage on Recovery in Post-war Dubrovnik, Croatia” authored by K. Bishop [

33]. This study scrutinizes the situation of Dubrovnik, a city that has undergone profound alterations since the conclusion of the conflict. Bishop posits that Dubrovnik has succeeded in preserving its cultural identity in spite of these transformations, primarily attributable to its dedication to safeguarding its historical architecture and monuments. Moreover, he emphasizes the value of initiatives led by the community, including festivals and various gatherings, that enhance a sense of unity and pride in the historical context of Dubrovnik.

The second article is “Urban tourism development in Prague: from tourist mecca to tourist ghetto” by V. Dumbrovska [

34]. This article examines the manner in which Prague has effectively leveraged its extensive historical and cultural heritage through substantial investments in tourism infrastructure. Dumbrovska posits that such investment has yielded advantageous outcomes for both visitors and residents, as it has facilitated job creation, enhanced local economies, and drawn an increasing number of tourists to the city. He also notes that this investment has been carefully managed so as not to detract from Prague’s unique cultural identity. The third article is “Branding post-war Sarajevo: Journalism, memories, and dark tourism” by Z. Volcic [

35]. This scholarly article investigates the measures undertaken by Sarajevo to safeguard its cultural heritage in the aftermath of the war, notwithstanding the considerable destruction inflicted by hostilities and subsequent neglect. Volcic posits that Sarajevo has achieved notable success in this pursuit, attributable to its dedication to the restoration of historic edifices and monuments, alongside the establishment of novel public spaces for the enjoyment of its citizens. Furthermore, he underscores the significance of these preservation initiatives in rendering Sarajevo a compelling destination for international tourists.

Halaf, in his study “Recovering Beirut: Urban design and post-war reconstruction” [

36], looks at how Beirut has sought to rebuild itself following years of conflict and destruction. Khalaf argues that Beirut’s success can be attributed largely to its commitment to preserving its unique cultural heritage while also investing heavily in tourism infrastructure such as hotels, restaurants, museums, galleries, and other attractions. He also notes that this approach has allowed Beirut to remain true to its identity while still taking advantage of the economic benefits offered by tourism investment.

The balancing of cultural preservation and tourism investment in historical cities involves several theories and concepts that are important to understand. One of the principal theoretical frameworks is the notion of sustainable tourism, which aspires to foster economic advancement whilst mitigating adverse effects on the environment and indigenous cultures [

37]. Another salient notion is cultural heritage, which denotes the tangible and intangible elements of a society’s historical narrative that are esteemed and safeguarded by that society [

38]. This may encompass edifices, artifacts, customs, and linguistic expressions, among various other components.

In order to balance cultural preservation and tourism investment, several strategies can be used. One methodology involves the advocacy of sustainable tourism practices that honor indigenous cultures while mitigating detrimental effects on the ecosystem. This may encompass strategies such as regulating the influx of visitors to a heritage site, fostering ethical conduct among travelers, and endorsing local enterprises that resonate with the principles of cultural conservation [

37,

39]. Another strategy involves engaging local communities in the formulation and administration of tourism endeavors. This approach can aid in guaranteeing that the cultural heritage of the region is honored and safeguarded, whilst concurrently offering economic advantages to the local populace [

40].

The field of conflict studies offers significant understanding regarding the intricacies of warfare and conflict dynamics, in addition to the myriad challenges and prospects linked to the process of post-conflict reconstruction. Conflict studies’ key concepts that can inform the study of historic Syrian cities include the following:

Conflict transformation: The process of addressing the underlying causes of conflict and changing the relationships, interests, and discourses that underpin violence and insecurity [

41].

Peacebuilding: A comprehensive array of activities and interventions designed to avert conflict and foster enduring peace, encompassing reconciliation, justice, and institutional reform [

42].

Post-conflict spatial strategies: The significance of urban planning and design in promoting post-conflict recovery, fostering reconciliation, and enhancing social cohesion, along with the capacity of urban interventions to confront the remnants of warfare and cultivate a shared sense of memory and identity [

43].

Post-war heritage development serves numerous crucial purposes, which include restoring pride and cultural identity, protecting and preserving cultural heritage for future generations, and offering chances for economic growth and tourism. Cities can focus on restoring historic architecture or creating public spaces, while others invest in tourism infrastructure like hotels or museums. All approaches aim to maintain post-war cities’ identity while boosting economic activity through tourism investment. In summary, the advancement of post-war heritage significantly aids in the comprehensive rehabilitation and progress of societies emerging from conflict.

These case studies reveal patterns aligned with the study’s theoretical foundation. Dubrovnik’s emphasis on cultural events and authenticity reflects core tenets of cultural heritage management (CHM), while Sarajevo’s branding and spatial reuse intersect with urban resilience and memory-work. Prague’s regulated tourism investment parallels the sustainability principles discussed in

Section 2.3. These connections lay the groundwork for framing Syrian recovery strategies within a tested but locally adaptable framework.

2.2. Impacts of Armed Conflict on Cultural Heritage

This literature review scrutinizes the obstacles linked to the conservation of Syria’s ancient urban centers in the post-conflict era, as well as the potential role of tourism investment in facilitating their reconstruction. The first article reviewed is “Heritage in post-war period challenges and solutions” by A. Belal (2019) [

44]. In this article, Belal discusses the challenges associated with preserving Syria’s old cities in the post-war period. He contends that as a result of the devastation inflicted by the conflict, numerous urban areas are presently requiring significant restoration efforts. He further observes that there exists an insufficiency of resources allocated for these initiatives and that there is an imperative for enhanced international assistance for their conservation. Belal suggests that investment in tourism could be one way to help fund such projects and ensure that these cities remain part of Syria’s cultural heritage.

The second article reviewed is “Dealing with Heritage in Syria: The Analysis of the Conflict Period (2011–2021)” by M. Zugaibi (2022) [

45]. In this article, Zugaibi discusses how investment in tourism can help to rebuild Syria’s old cities after the war. He posits that such capital allocation has the potential to generate essential employment opportunities and financial resources for local communities, concurrently contributing to the preservation of their cultural heritage. Zugaibi further observes that these investments could serve as a mechanism to foster peace and stability within the region by facilitating interactions among individuals from diverse backgrounds.

Finally, the third article reviewed is “The role of cultural routes in sustainable tourism development: A case study of Syria’s spiritual route” by B. Dayoub (2020) [

46]. In this article, Dayoub examines how investment in tourism can help preserve Syria’s old cities while also promoting its cultural identity. She contends that such financial allocations may be utilized to generate employment opportunities for local residents while concurrently affording Syrians the chance to re-establish connections with their historical heritage through excursions to these locations. Dayoub also suggests that such investments could be used as a tool for reconciliation between different groups within Syria who have been divided by conflict.

In general, this literature synthesis has elucidated several challenges pertinent to the preservation of Syria’s historical urban centers in the post-conflict era, alongside an examination of how investments in the tourism sector may facilitate their reconstruction while concurrently safeguarding their cultural identity. It has demonstrated that such financial commitments could generate essential employment opportunities and revenue streams for local populations, concurrently fostering peace and stability in the region through the promotion of reconciliation among the diverse groups within Syria that have been fragmented by warfare.

2.3. Strategic Approaches to Post-War Urban Recovery

The study of historic Syrian cities post-war is crucial as it addresses the complex challenges and opportunities they face. A solid theoretical framework is needed to understand the factors shaping urban fabric and socio-cultural dynamics. Key theoretical perspectives will be discussed, drawing from urban planning, cultural heritage management, and conflict studies to provide a comprehensive background for this study.

The concept of urban resilience broadly refers to the capacity of urban systems—including infrastructure, institutions, and communities—to absorb shocks, adapt to disruption, and reorganize while maintaining essential functions and identity. This definition, applied increasingly in post-conflict urban studies, draws from the work of [

47,

48,

49], which emphasizes the relational, adaptive, and cross-scalar dimensions of resilience in cultural and urban contexts. For example, [

47] underscores resilience as a cultural process embedded in heritage continuity, while [

48] interprets it as a planning tool that incorporates community networks and socio-spatial ethics. The work of [

49] further asserts that resilience metrics must account for not just technical durability but institutional learning and recovery pathways.

The theoretical framework of urban resilience offers a valuable perspective for comprehending the capacity of urban areas to endure, recuperate from, and adjust to the ramifications of warfare and conflict. The capacity of a city to maintain or quickly recover its essential functions and structures in the face of acute shocks and chronic stresses, according to the literature [

50]. Investigating the determinants that enhance urban resilience within the framework of historic Syrian cities can yield significant understanding regarding the processes of recovery and reconstruction subsequent to conflict.

The following are key aspects of urban resilience that are relevant to the study of historic Syrian cities:

Urban resilience contributes core concepts such as adaptive capacity, risk management, and system recovery. It offers a lens through which the study evaluates how cities can withstand and reorganize after disruption, especially in terms of social, economic, and physical dimensions [

47].

Cultural heritage management (CHM) informs the study’s focus on authenticity, integrity, and integrated conservation. It provides normative standards (e.g., the Venice Charter, Nara Document) for assessing post-conflict restoration strategies and the risks of commodification or neglect [

48].

Sustainability theory underscores the importance of intergenerational equity, resource efficiency, and long-term planning. It ensures the study evaluates recovery not only as a technical fix but as a transformation aligned with environmental and social systems [

51].

Conflict studies frame the political, institutional, and identity-based ruptures that shape post-war urban recovery. They emphasize reconciliation, inclusivity, and the prevention of recurrence, making them particularly relevant in Syria’s deeply divided context [

28,

38,

39].

Furthermore, cultural heritage management (CHM) is an intricate tapestry that weaves together various disciplines, dedicated to safeguarding, nurturing, and ensuring the enduring utilization of both tangible and intangible treasures of cultural legacy [

52]. CHM provides valuable insights into the challenges and opportunities associated with post-war recovery and reconstruction in the context of historic Syrian cities. Key concepts from CHM that can inform the study of historic Syrian cities include the following:

Building on these foundations, sustainability theory introduces a vital dimension by underscoring the need to balance present recovery needs with long-term ecological, cultural, and social well-being [

55,

56]. Sustainability emphasizes that post-war reconstruction should not only repair damage but also promote systems and practices that are adaptable, resource-efficient, and equitable across generations. This perspective reinforces the importance of integrating environmental stewardship, cultural continuity, and inclusive development into recovery frameworks.

By combining insights from urban resilience, cultural heritage management, sustainability theory, and conflict studies, this theoretical framework offers a robust foundation for analyzing the recovery trajectories of historic Syrian cities (

Table 1). It enables the research to explore the multifaceted challenges these cities face while identifying strategies to safeguard their unique cultural heritage, strengthen social cohesion, and promote sustainable and resilient urban development in the wake of conflict.

While the international literature provides diverse approaches—from community-led restoration in Dubrovnik to hybrid governance in Sarajevo—these cases underscore commonalities in resilience-building through cultural identity reconstruction. However, the Syrian case presents unique challenges in scale, institutional weakness, and protracted crisis. Unlike cities with centralized recovery phases, Syria’s fragmentation demands localized, multi-actor frameworks. Thus, synthesizing these global cases informs but cannot replace a Syria-specific framework grounded in community engagement, integrated conservation, and adaptive governance, as explored in the next section.

2.4. Syrian-Specific Literature and Gaps

While global post-conflict cases provide critical insights, the Syrian context remains underexplored in the academic literature. Belal (2019) identifies major logistical and institutional challenges in restoring Syrian cities, emphasizing the lack of funding and international coordination [

44]. He suggests that tourism investment may serve as both a financial and symbolic tool for urban regeneration.

Zugaibi (2022) presents a decade-long analysis of the conflict’s impact on heritage, advocating for tourism as a mechanism for peacebuilding and cultural re-engagement [

45]. His work is among the few to explicitly tie tourism development to post-conflict reconciliation in Syria. Dayoub (2020) [

46] examines the role of spiritual and cultural routes in promoting sustainable tourism. Her case study highlights the potential of non-physical heritage—rituals, routes, and practices—as a platform for community identity and reconciliation.

Despite their contributions, these studies often remain isolated from theoretical discussions in urban resilience and CHM. Moreover, they rarely incorporate empirical data from local communities, which this study addresses through field-based interviews and surveys. The integration of Syrian-specific findings with broader theoretical and comparative frameworks marks a key advancement of this research.

This thematic synthesis demonstrates that while global precedents offer valuable lessons, the Syrian context requires a hybrid model—one that balances international best practices with localized strategies rooted in community resilience, cultural specificity, and adaptive governance.

While these studies offer important entry points into the discourse on Syrian heritage recovery, several notable limitations persist [

57,

58]. First, most existing Syrian scholarship tends to emphasize macro-level funding and restoration logistics but lacks grounding in field-based stakeholder perspectives [

59,

60]. These works often do not include empirical interviews or quantitative surveys that capture how local communities perceive, resist, or co-construct recovery strategies.

Second, studies underscore the potential of tourism and spiritual routes, yet they frequently treat tourism investment as an inherently stabilizing force, without interrogating the risks of commodification, social exclusion, or the loss of authenticity [

46]. This reflects a broader gap in applying CHM and resilience theory to critically assess tourism dynamics in post-conflict contexts. Third, few studies attempt to synthesize multidisciplinary frameworks or adopt integrated models linking cultural preservation with governance, conflict resolution, and sustainability. Most treat heritage, tourism, and recovery in silos, which limits their capacity to inform system-wide planning.

By addressing these gaps, this study contributes a theory-driven, methodologically grounded, and field-validated understanding of heritage recovery in Syria—anchored in mixed methods, actor analysis, and triangulated results that align with global frameworks while remaining context-specific.

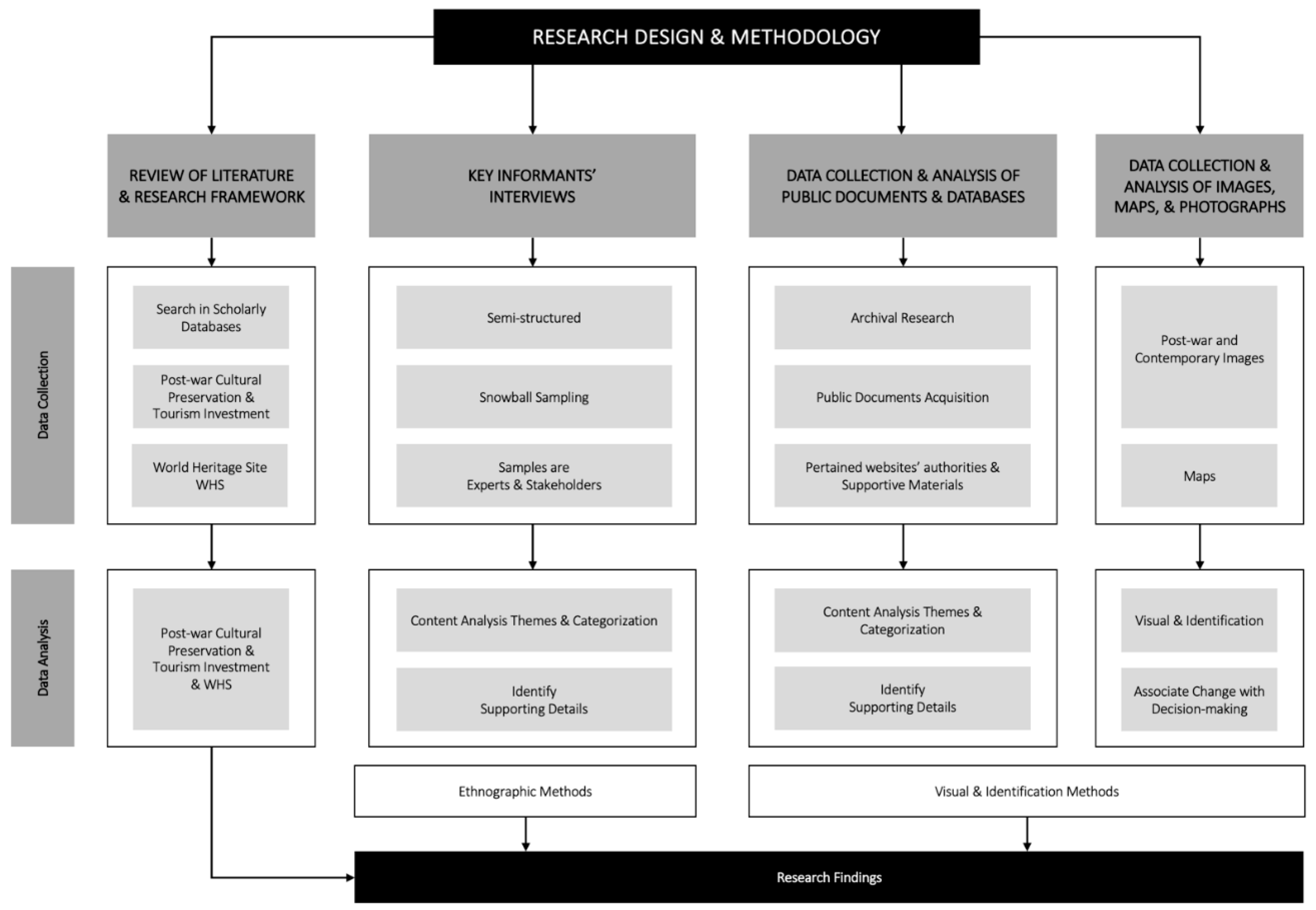

3. Research Design and Methodology

This study integrates various research techniques to comprehensively study the recovery of Syria’s historic cities post-conflict, focusing on sustainable urban evolution, cultural heritage conservation, and nurturing community resilience. To ensure methodological transparency and academic rigor, the study was structured in four interdependent phases: (1) conceptual framing through literature review and theory construction, (2) qualitative fieldwork using stakeholder interviews, (3) quantitative analysis via structured surveys, and (4) integrative analysis using a theoretical matrix model. Each phase was designed to cross-validate findings and ensure coherence between empirical data and theoretical constructs. The triangulation of methods enhanced the internal validity of the research and offered nuanced insights into the governance, socio-economic, and cultural dimensions of Syria’s post-conflict urban heritage recovery. Thus, the methodology integrates qualitative and quantitative strategies, ensuring a robust and multi-layered understanding of the challenges and opportunities involved.

First, a comprehensive analysis of the existing literature took place using academic platforms like Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar to pinpoint significant themes, theoretical constructs, and contextual knowledge. This phase helped establish the study’s conceptual foundation, particularly aligning it with urban resilience, cultural heritage management, sustainability theory, and conflict studies. Snowballing techniques were also employed to trace additional relevant sources and refine the conceptual framework.

Second, for the qualitative phase, a purposive sampling strategy was employed to select participants with relevant expertise and diverse stakeholder representation. Inclusion criteria for interviewees included the following: (1) direct involvement in cultural heritage or urban recovery projects; (2) formal affiliation with government, private sector, or heritage organizations; and (3) residency or active fieldwork in affected Syrian cities. This yielded 20 semi-structured interviews: 5 with government officials, 9 with private-sector actors, and 6 with heritage specialists. The sample size was determined based on thematic saturation, defined as the point at which no new codes or themes emerged during iterative coding (

Table 2).

The interview protocol was developed using a theory-informed strategy to ensure alignment with the study’s four core analytical frameworks: urban resilience, cultural heritage management (CHM), sustainability theory, and conflict studies. Each thematic cluster of questions was designed to reflect these domains. Questions addressing institutional adaptability, governance coordination, and recovery capacity were grounded in urban resilience theory, particularly focusing on the capacity of urban systems to absorb, adapt, and reorganize following disruption. Questions related to the treatment of heritage sites, conservation approaches, and risks of commodification were informed by the principles of CHM, emphasizing authenticity, integrity, and stakeholder participation. Sustainability theory guided the formulation of questions examining the long-term balance between economic revitalization and heritage preservation, as well as intergenerational cultural continuity. Finally, conflict studies provided the conceptual basis for questions probing post-war reconciliation, governance legitimacy, and the reintegration of displaced communities. This structured and theory-driven approach ensured that interviews elicited responses that were not only reflective of individual experiences but also analytically consistent with the study’s overarching conceptual model. As seen,

Table 2 operationalized this logic by linking question domains with corresponding theoretical dimensions.

Interview transcripts were analyzed using inductive thematic analysis with a six-phase framework [

61]. This included familiarization with the data, generation of initial codes, theme development, review and refinement, theme definition, and final synthesis. Coding was conducted manually, with cross-validation by two researchers to ensure consistency and reliability. Saturation was evaluated after the eighteenth interview, with two additional interviews confirming that no new themes emerged. The emergent themes were then mapped to the theoretical constructs outlined in the study’s conceptual framework (

Figure 1), ensuring alignment between data patterns and analytical categories.

Thus, a structured online survey employed stratified convenience sampling to capture a broad demographic spread. The final sample included 265 participants, stratified by gender, age, and nationality. Inclusion criteria required participants to be over 18 years old and residents or professionals familiar with historic Syrian urban contexts. The survey was administered from 25 December 2024 to 5 January 2025, correcting the previously stated overlap. In terms of nationality, 185 respondents were Syrian, while 80 were non-Syrian. This diverse demographic distribution ensured a broad representation of perspectives and allowed for subgroup comparisons within the analysis.

The inclusion of 80 non-Syrian respondents (30.2% of the survey population) was intentional, reflecting the diverse demographic presence in post-conflict Syrian urban areas and the influence of international actors (e.g., NGO personnel, humanitarian workers, academics, expatriates). Their perspectives offered valuable comparative insight, especially regarding perceptions of cultural heritage, governance quality, and tourism development. However, to preserve contextual specificity, subgroup analyses were conducted to distinguish between Syrian and non-Syrian responses. These analyses confirmed general alignment in key trends (e.g., prioritization of damage and financial barriers) but also revealed subtle differences—such as higher sensitivity among Syrians to issues of authenticity and community participation. Non-Syrian responses were not excluded but were interpreted cautiously, especially where national context, local knowledge, or emotional resonance may shape interpretation. Their inclusion, while broadening representativeness, was analytically bounded to ensure the central narrative remained grounded in Syrian stakeholder realities.

Interview transcripts were analyzed using inductive thematic analysis based on the Braun and Clarke (2014) [

62] six-phase framework. This included familiarization with the data, generation of initial codes, theme development, review and refinement, theme definition, and final synthesis. Coding was conducted manually, with cross-validation by two researchers to ensure consistency and reliability. Saturation was evaluated after the 18th interview, with two additional interviews confirming that no new themes emerged. The emergent themes were then mapped to the theoretical constructs outlined in the study’s conceptual framework, ensuring alignment between data patterns and analytical categories. In the area of quantitative evaluation, the survey results experienced a meticulous descriptive statistical scrutiny, which comprised the assessment of frequencies, averages, standard deviations, and percentage distributions across demographic groups including age, gender, and nationality. Comparative statistical techniques were applied to explore variations in responses between key subgroups, identifying significant trends, shared priorities, and differences in stakeholder perceptions. Additionally, snowball analysis techniques were employed to trace relational connections and information flows between actors, enhancing the understanding of how ideas, practices, and influence circulate within the network of political, social, and economic stakeholders, particularly in hard-to-access, post-conflict environments. This multi-layered analysis ensured a comprehensive, evidence-based interpretation that integrates qualitative depth with quantitative breadth.

Finally, the integration of qualitative and quantitative findings was guided by the theoretical matrix developed in this study, ensuring that results directly inform recommendations for political, social, and economic actors. These recommendations aim to balance heritage conservation with urban resilience and sustainability, offering practical pathways for the recovery and revitalization of historic Syrian cities in the post-war era. See

Figure 2.

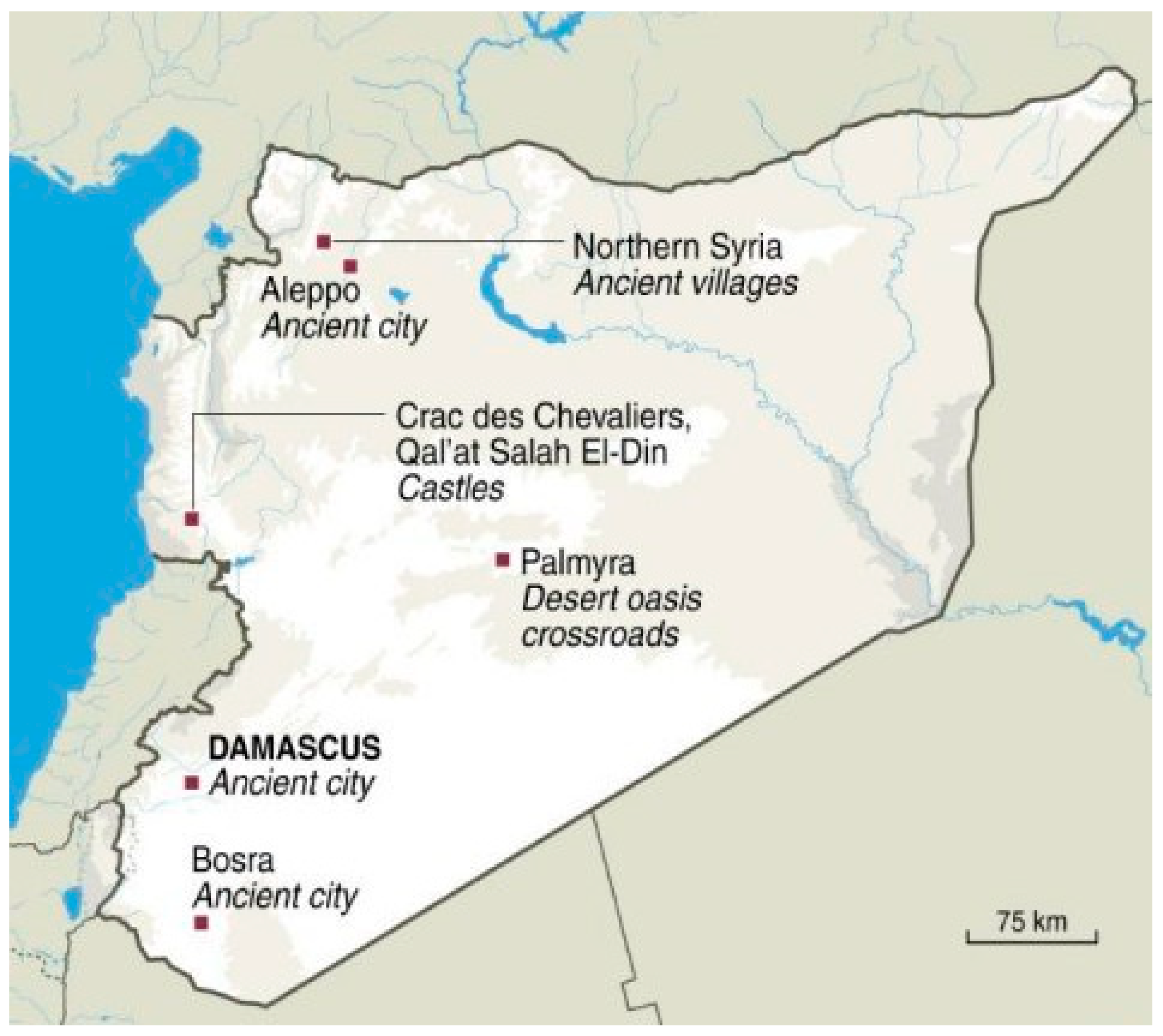

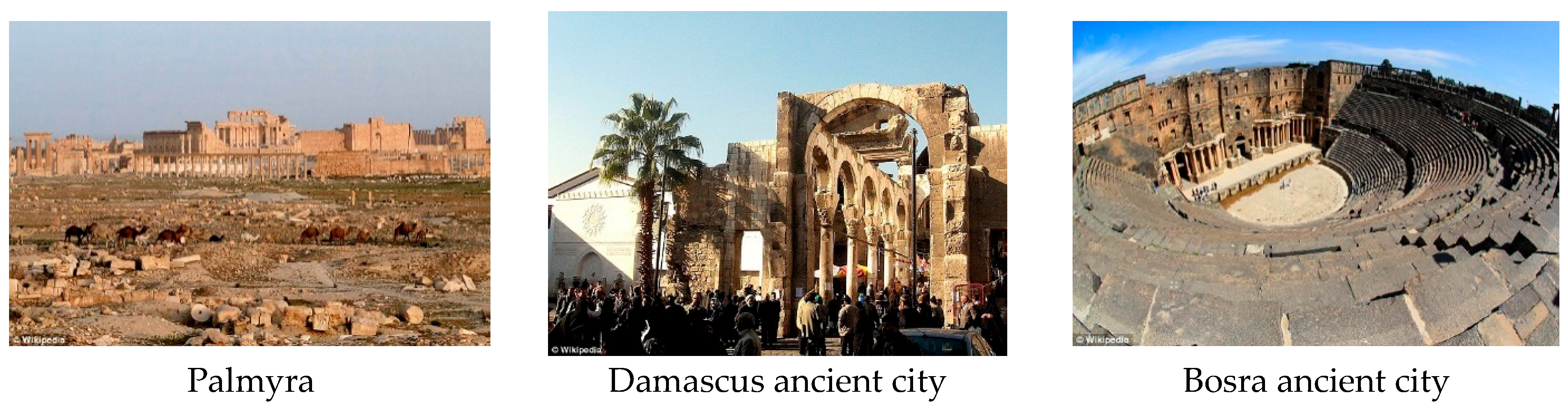

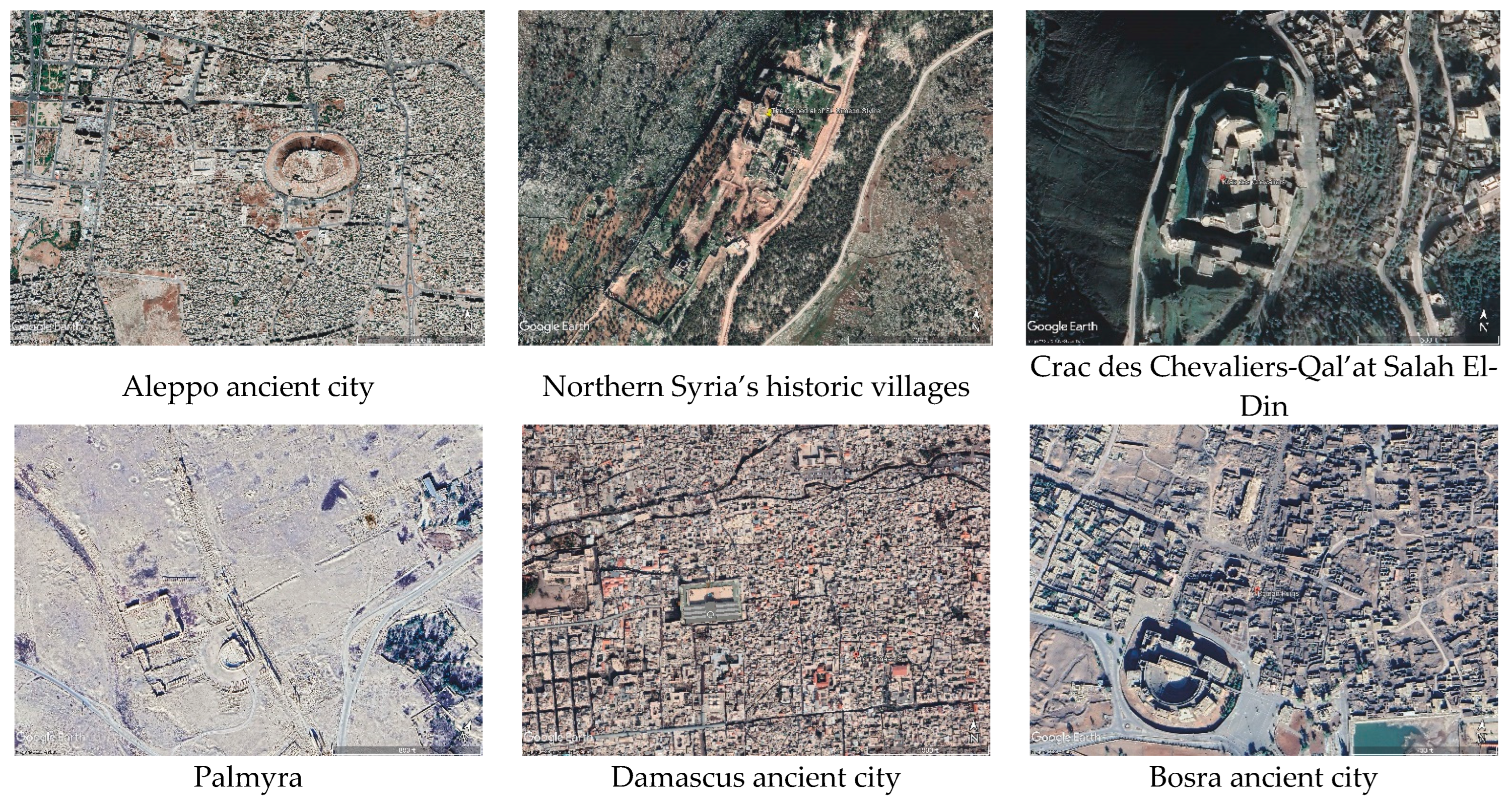

4. Case Study: The Six Syrian World Heritage Sites and the Destructive Impact of War

Syria is rich in history and culture. Archeological sites, in addition to historical structures, are the best witnesses to this history [

63], being registered on the list of world heritage protected by UNESCO [

64]. The cultural identity of these six archeological sites in Syria is profoundly entrenched in the historical and cultural narratives of the region. Damascus, for instance, stands as one of the most ancient capitals that has been persistently inhabited throughout history and has served as a significant hub of culture and civilization since ancient epochs [

65]. It is home to many important religious sites, including the Umayyad Mosque, which was built in 705 AD [

66]. Bosra or Bosra al-Sham is an ancient city in southern Syria that was a Roman province [

67]. It contains some of the period’s most impressive ruins, including a large amphitheater and several temples [

67]. This urban center exemplifies the myriad cultural influences that have molded its development throughout the centuries, rendering it an intriguing locus for historians and architecture aficionados alike. This city is a testament to the diverse cultural influences that have shaped it over the centuries, making it a fascinating destination for history buffs and architecture enthusiasts alike. Visitors can also enjoy the vibrant local markets and sample traditional cuisine in the city’s many restaurants.

Aleppo is a northern Syrian city that has been inhabited since at least 3000 BCE [

67,

68]. It contains numerous significant monuments from various eras, including a citadel from the 12th century and several mosques from various eras [

13,

68,

69,

70]. St. Simeon’s Monastery and St. George’s Church are among the important Christian sites in Aleppo [

67]. Palmyra is an ancient city in central Syria that formerly belonged to the Roman Empire [

71]. It contains a large temple complex dedicated to Baal and numerous other temples dedicated to various gods and goddesses [

72]. Crac des Chevaliers and Qal’at Salah El-Din are two of the Middle East’s most impressive medieval castles. The Crac des Chevaliers is a Crusader castle constructed by the Knights Hospitaller in the 12th century [

73]. It is renowned for its intact architecture and strategic location. The majestic Qal’at Salah El-Din was erected by the illustrious Ayyubid dynasty during the 12th century and is celebrated as one of the most pivotal strongholds in the region [

74]. Saladin utilized it as a base during his campaigns against the Crusaders [

75].

The ancient villages in northern Syria are another important part of Syrian cultural identity [

76]. These settlements encompass numerous historical edifices constructed from earthen bricks or stone, which originate from several centuries past and remain occupied in the present by indigenous inhabitants who persist in the observance of customary practices, including the art of carpet weaving and pottery fabrication [

77]. These six archeological sites represent an incredibly rich cultural identity that has been shaped by centuries of history and culture in Syria. They furnish us with a profound understanding of the lifestyles of individuals across various historical epochs, in addition to elucidating their contemporary existence as influenced by traditional customs and belief systems. See

Figure 3 and

Figure 4.

Despite the emergence of new WHS cases and issues, UNESCO and ICOMOS have made significant efforts to discuss the suitability of conservation strategies [

80,

81]. However, as a response to ongoing concerns about WHS protection, UNESCO and ICOMOS have proposed the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach. As a result, the new proposed approach has broadened the debate to include urban landscape and change management [

82,

83]. The HUL methodology emphasizes multiple historical periods’ cultural, natural, and intangible characteristics. By integrating conservation strategies into urban development strategies, this strategy aims to prioritize protection, conservation, heritage, and change management in historic settings undergoing rapid urbanization development [

82].

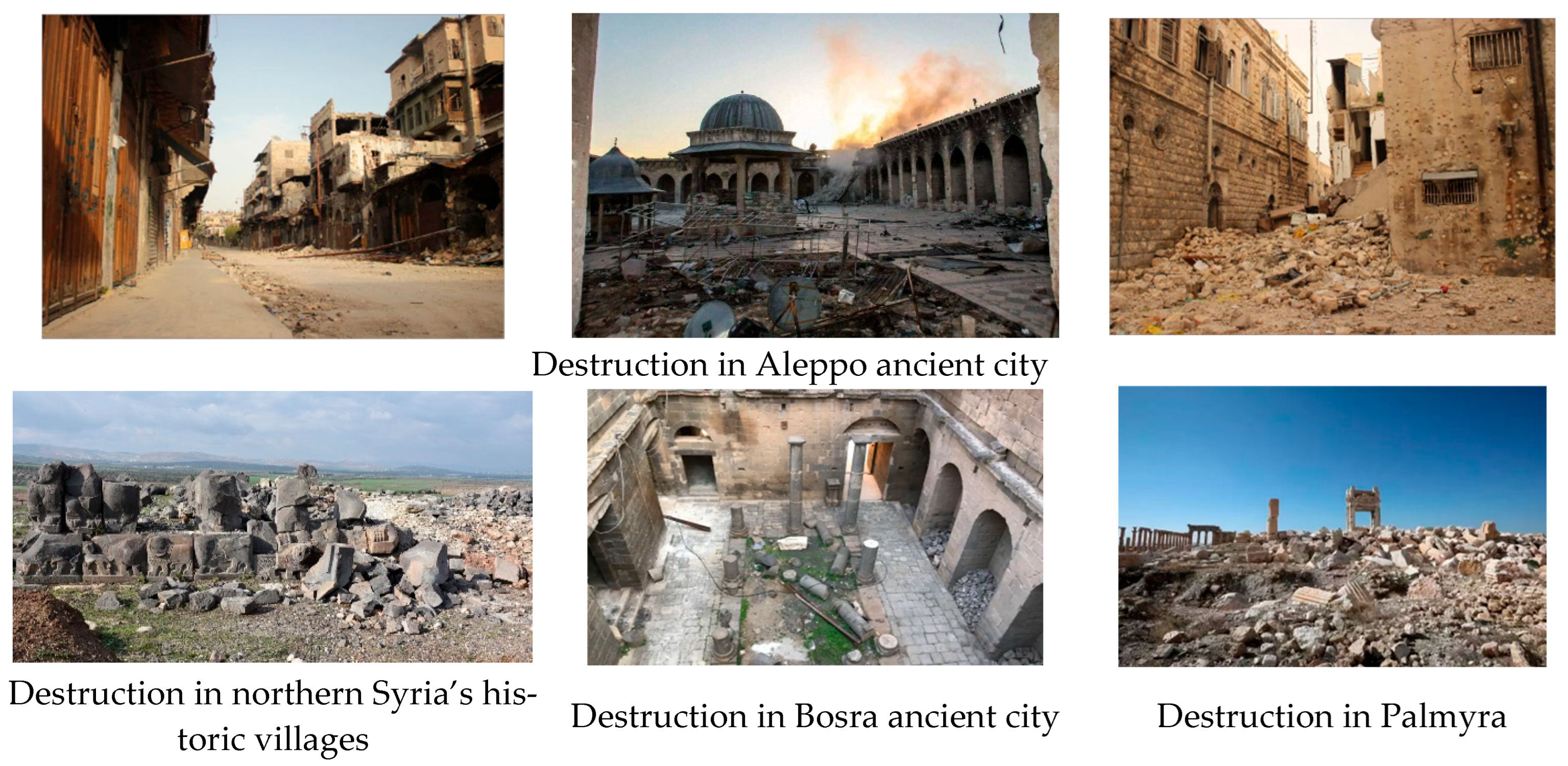

The devastating effects of the war in Syria can be seen in the destruction it has caused to some of its oldest cities [

64,

84,

85]. Aleppo, Damascus, and Palmyra are among those which have suffered greatly as a result, with their ancient monuments and artifacts destroyed or left to crumble [

86,

87,

88,

89]. Regrettably, the detrimental effects are not merely confined to corporeal devastation; the conflict has exerted a profound psychological influence on the populace that once resided in these urban areas, a significant portion of whom have been compelled to evacuate as a result of hostilities or scarcity of essential resources. This brings with it a sense of loss and despair which cannot be quantified. The irreparable damage done to these cities is a tragedy for both Syria and for the planet as a whole [

90], representing an incalculable loss for cultural heritage and history that will never be restored [

90].

The city of Aleppo has been the site of immense destruction, damage, and cultural loss due to conflict-related violence in the past five years [

91]. Estimates show that 70% of all buildings have been severely damaged or destroyed, completely altering its landscape [

92]. Additionally, over 90% of its once-iconic mosques and churches, as well as libraries, museums, and archeological sites, have suffered destruction as well [

84,

92]. This destruction has also had an economic toll on its inhabitants, with 1 million people having been displaced from their homes and a total economic loss amounting to USD 4 billion for those still in the city [

93,

94,

95]. It is clear that these events have affected every aspect of life within Aleppo in an extremely negative manner.

In 2015, Palmyra was captured by the Islamic State, which had a deeply harmful effect, leading to over 60% destruction of this historic city and its landmarks [

88,

96,

97,

98]. The looted artifacts number up to 1500 taken between 2015 and 2017, adding insult to injury for Syria’s cultural heritage as well as damaging their tourism industry—from 150k visitors pre-capture down almost entirely to 890 reported tourists by 2017 statistics. It is an undeniable tragedy that this once popular tourist destination has been stripped of not only life but also much of its historically significant art and architecture.

The ancient city of Bosra or Bosra al-Sham reveals that it has been substantially affected by the Syrian Civil War [

99]. According to satellite imagery, there were over 300 damaged structures in this city in 2018—a twofold increase from 2012 [

100]. Furthermore, archeological sites have been badly affected; the World Monuments Fund notes that many monuments and architectural features such as columns and porticoes have been destroyed in both Bosra al-Sham and its nearby villages.

The Syrian Civil War has also taken an enormous toll on the delicate beauty of Damascus and its surrounding areas [

101]. The capital has been shelled and battered by airstrikes since 2011. The archeological sites like Crac des Chevaliers have served as strongholds for belligerent forces between 2012 and 2013 [

99], with further damage resulting from their recapture in 2014. Moreover, villages with centuries of history have been obliterated due to confrontations between state military forces and insurgent factions, resulting in the forced relocation of substantial segments of the indigenous populace in order to evade the ensuing violence. Even Qal’at Salah El-Din—an important monument considered to be one of the most impressive examples of Crusader architecture—was affected by the war, having suffered major destruction after being captured by regime forces. Such profound destruction delineates a grave representation of what has evolved into a persistent calamity for individuals impacted both presently and in the foreseeable future [

102].

5. Results

Tourism investment in historic Syrian cities can contribute to the restoration and preservation of cultural heritage sites while promoting economic development. Tourism constitutes a critical revenue stream for numerous nations and has the potential to generate employment opportunities for indigenous populations. Tourism acts as a major financial boost for countless countries and can enable local inhabitants to secure employment. Nevertheless, it is imperative that tourism investments are harmonized with efforts toward cultural preservation to safeguard the integrity of the nation’s cultural legacy. As result, after undertaking research on this current topic and acquiring knowledge from several sources, the study findings have been segregated into two main classes: the complexities associated with reconstructing historic Syrian cities and the essential contributors to the dialog on heritage cities.

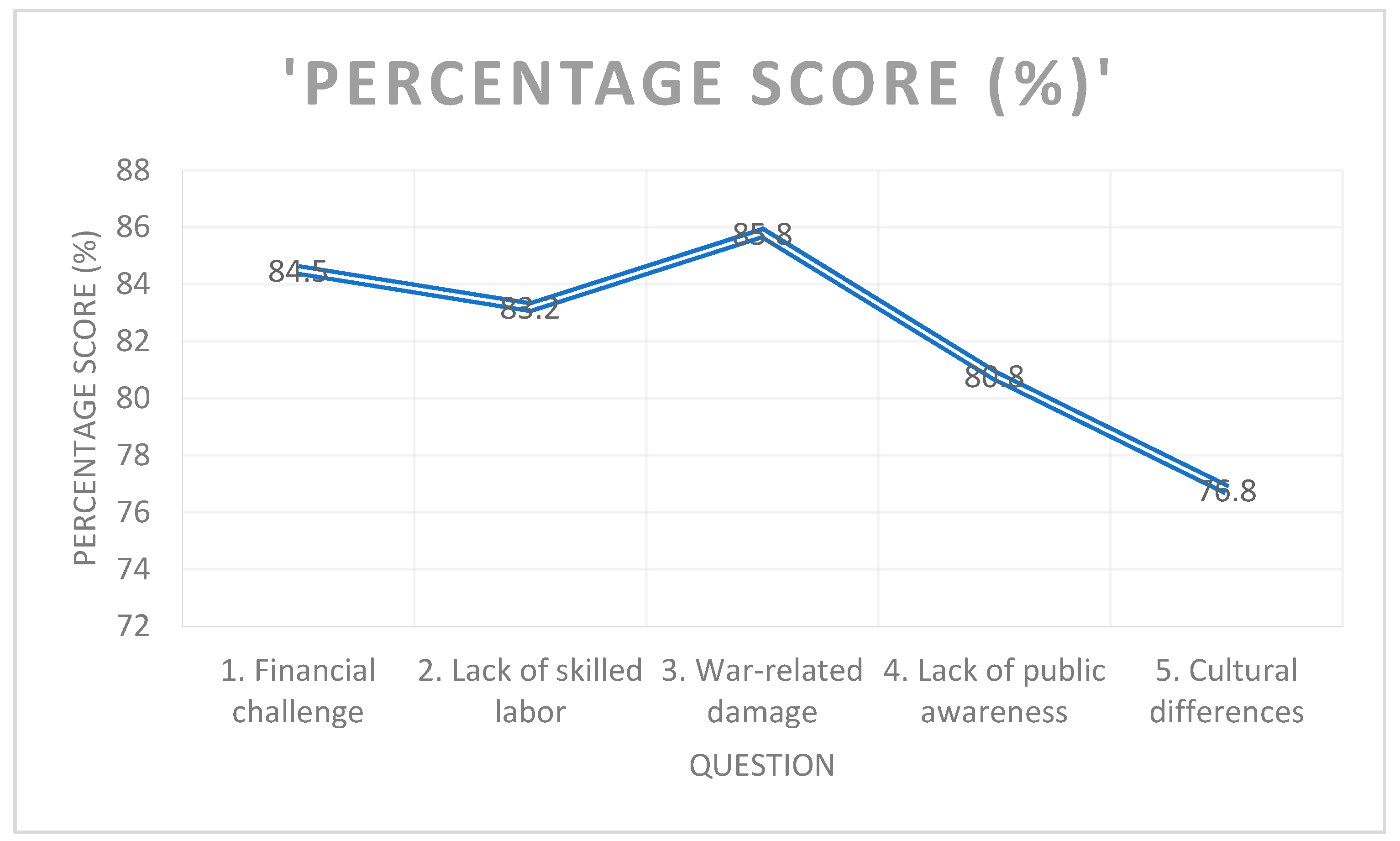

The survey results highlight several pressing challenges confronting the reconstruction of historic Syrian cities, with respondents assigning particularly high concern to financial and war-related factors. Financial challenges were rated at 84.5%, reflecting the widespread recognition that limited funding and resource constraints are among the most critical barriers to effective recovery. Closely following is the challenge of war-related damage, scoring the highest at 85.8%, underscoring the devastating physical impacts of conflict on heritage structures and urban fabric. A slightly lower but still significant concern is the lack of skilled labor (83.2%), pointing to the shortage of qualified craftsmen, conservation experts, and technical personnel necessary for culturally sensitive rebuilding efforts. Meanwhile, the lack of public awareness (80.8%) and cultural differences (76.8%) were perceived as somewhat less urgent but remain important, highlighting gaps in local engagement, education, and the socio-cultural complexities of post-conflict reconstruction. Overall, the survey results suggest that addressing both material and human factors is essential to overcoming the multifaceted barriers facing heritage-led urban recovery in Syria.

Thus, the structured survey gathered quantitative data on community perceptions of heritage challenges and recovery priorities in post-conflict Syrian cities. Respondents ranked key challenges and rated institutional actors using Likert-scale items and multiple-choice rankings.

Figure 5 presents aggregated responses on the five most pressing challenges, constructed from survey data and presented in descending order of perceived severity. Key findings from the survey include the following:

War-related damage was perceived as the most severe barrier to heritage recovery, cited by 85.8% of respondents.

Lack of financial resources followed closely (84.5%), reinforcing the urgency of coordinated funding.

Shortage of skilled labor (83.2%) emerged as a critical human capital gap in post-conflict settings.

Low public awareness (80.8%) and cultural divergence in restoration preferences (76.8%) were also flagged, particularly by younger and non-local respondents.

5.1. Challenges of Rebuilding Historic Syrian Cities

Rehabilitation and reconstruction of the ancient Syrian cities’ architectural heritage is a daunting task. Throughout the civil conflict, a significant portion of the nation’s historical sites and monuments were either destroyed or extensively impaired, culminating in a substantial diminution of cultural heritage. This situation has engendered a profound absence within the nation’s cultural identity, and it now rests upon those engaged in the restoration efforts to reinstate these sites to their original magnificence. Through theoretical and field research, as well as information gathered from those concerned with the issue of restoring Syria’s cultural heritage after the conflict. Balancing cultural preservation and tourism investment in historic Syrian cities faces several challenges. These obstacles encompass the insufficiency of financial resources allocated for restoration and preservation initiatives, prevailing political instability, concerns regarding security, and the imperative for community engagement. Furthermore, the drawn-out strife in Syria has caused considerable damage and ruin to various historical locations, consequently worsening the obstacles tied to the conservation and encouragement of cultural heritage. Despite these difficulties, both regional and international entities are taking collaborative actions to preserve and rejuvenate this priceless cultural heritage.

The qualitative phase, conducted from 9 to 22 December 2025, yielded thematic insights on five domains aligned with the study’s theoretical matrix: governance, economic sustainability, heritage authenticity, community inclusion, and risk resilience. Interview quotes reinforced many of the survey findings, including the following:

On financial constraints, a local heritage consultant noted that “The state’s priority is survival, not conservation. Restoration is postponed unless tied to income generation.”

On labor shortages, a municipality officer said that “We lack architects trained in heritage techniques. Our young professionals are unfamiliar with lime plaster or load-bearing earthen masonry.”

On cultural divergence, one international expert shared their view that “Modern consultants push concrete reconstructions, but locals often prefer mudbrick—even if it’s less durable—because it feels authentic.”

Thus, the mixed-methods design allowed for triangulation of our findings in the following ways:

Both methods highlighted financial constraints and war-related damage as the most urgent recovery barriers.

Interview data deepened the survey findings by explaining why these challenges persist—e.g., lack of governance mechanisms for coordinated funding, or the absence of a vocational training pipeline.

Divergences were also noted: while interviews emphasized political narratives and legitimacy-building, surveys placed more weight on technical gaps and everyday usability of heritage sites.

5.1.1. Limited Financial Resources

The protracted civil conflict in Syria has culminated in a significant deficit of financial resources allocated for the restoration and conservation of cultural heritage sites. The Syrian government’s resources are primarily focused on ending the conflict and providing humanitarian aid to affected communities. The restoration and preservation of cultural heritage sites do not constitute a priority, and the government is deficient in financial resources to implement such initiatives. This has led to the destruction of several cultural heritage sites, and their restoration and preservation require significant investments.

The cost of restoring and reconstructing the architectural heritage of old Syrian cities is prohibitively expensive due to limited financial resources. Many historical edifices necessitate significant restoration efforts, often incurring substantial costs. Numerous entities face financial challenges in securing the required repairs due to elevated prices of materials and labor. The condition of many structures is further exacerbated by their locations in regions afflicted by conflict or natural calamities. In response to these challenges, organizations have started to explore alternative funding avenues, including grants from global entities, private benefactors, and crowdfunding initiatives. Such strategies enable these organizations to engage a broader demographic, thereby increasing potential funding beyond traditional methods.

Organizations may collaborate with local entities for financial project support. This collaboration may involve discounted materials or volunteer labor for donations. Such efforts can lower restoration costs while facilitating project progression. Some organizations are exploring technology to mitigate restoration expenses. For instance, 3D printing has been utilized to produce replicas of rare or costly components.

5.1.2. Lack of Skilled Labor

The scarcity of skilled labor is a significant challenge globally, particularly in Syria. The prolonged civil war has led to extensive displacement and infrastructure damage. This has severely impacted the economy, leaving many Syrians unemployed. The deficiency of skilled labor has adversely affected Syria’s cultural heritage. Numerous historic structures have suffered damage or destruction, with remaining sites urgently needing restoration. Yet, such restoration demands specialized skills that are presently scarce in Syria. Many craftsmen proficient in these skills have either died or fled the country due to the conflict, complicating restoration efforts.

The shortage of skilled labor impacts various facets of Syrian society. A serious lack of engineers and technicians is impacting the repair of infrastructure affected by conflict. This scarcity of skilled labor constitutes a significant challenge for Syria’s post-conflict reconstruction efforts. The acquisition of necessary skills and knowledge for reconstruction will require time, necessitating an immediate commencement of this educational process for effective recovery. Furthermore, international organizations ought to facilitate training programs to expedite Syrians’ access to these vital skills. Such support is crucial for enabling Syrians to undertake the reconstruction of their nation with renewed confidence and optimism for future prospects.

5.1.3. Damage Caused by Conflict

The conflict in Syria has resulted in profound impairment of the country’s architectural landmarks and infrastructure. This destruction has occurred through both direct assaults and collateral impacts, including aerial bombardments, artillery fire, and theft. The loss of these structures has severely undermined the country’s cultural heritage and historical narrative. The most prominent devastation affects ancient monuments and archeological sites, which have either been obliterated or compromised by the hostilities. Many of these sites are unique, and their loss represents a critical blow to Syria’s cultural legacy. Also, a wide range of venerable edifices, comprising churches, mosques, and royal palaces, have endured injury or devastation stemming from combat activities.

The conflict has inflicted severe damage on the infrastructure of the old city. Roads have been rendered unusable due to factional hostilities. Bridges have suffered damage or destruction from aerial attacks or artillery. Power lines have been compromised as a result of sabotage or destruction by combatants. These infrastructure failures have notably restricted Syrians from obtaining essential services, including electricity, water, and healthcare. See

Figure 6.

The Syrian conflict has inflicted significant physical and psychological harm, requiring prolonged recovery. The restoration of buildings and monuments is challenging yet crucial for the preservation of Syrian cultural heritage.

5.1.4. Lack of Awareness

The civil war in Syria has led to a disregard for the significance of heritage conservation. Consequently, securing financial and political backing becomes challenging. This ignorance stems from the conflict’s interference and the scarcity of educational resources. This misunderstanding arises from the war’s upheaval and scarce educational resources. Without proper education and outreach efforts, many Syrians may not be aware of the economic benefits of preserving and restoring these structures, such as generating income from tourists and creating employment opportunities in hospitality and related industries. The preservation of Syria’s cultural heritage necessitates a multifaceted strategy that addresses both educational obstacles and political obstacles. This includes education initiatives aimed at both local communities and international audiences, guided tours and workshops, and marketing campaigns highlighting Syria’s rich cultural heritage. Additionally, greater political support for conservation efforts, such as lobbying government officials or collaborating with international organizations, is required. Highlighting the importance and economic value of these structures promotes their preservation for future generations.

5.1.5. Cultural Differences

Cultural differences significantly impact architecture, making it challenging for architects from different backgrounds to agree on the best methods for building restoration. In the United States, architects prioritize modernization of buildings utilizing contemporary technologies and materials for enhanced efficiency and cost-effectiveness. However, in Syria, traditional methods, such as using stone or brick, hand-carved details, and intricate mosaics, are preferred for restoring buildings, as they are seen as more authentic and respectful of the original structure. This can lead to disagreements between architects from different backgrounds in achieving the best restoration of a building.

Restoring a Syrian building requires architects from diverse backgrounds to bridge cultural differences and create a respectful, modern design that meets safety and efficiency standards. Designers should understand local customs to ensure cultural appropriateness. Cultural differences can be both challenging and rewarding, but by understanding each other’s perspectives and working towards a common goal, architects can create a beautiful design, honoring Syrian architecture, both past and present.

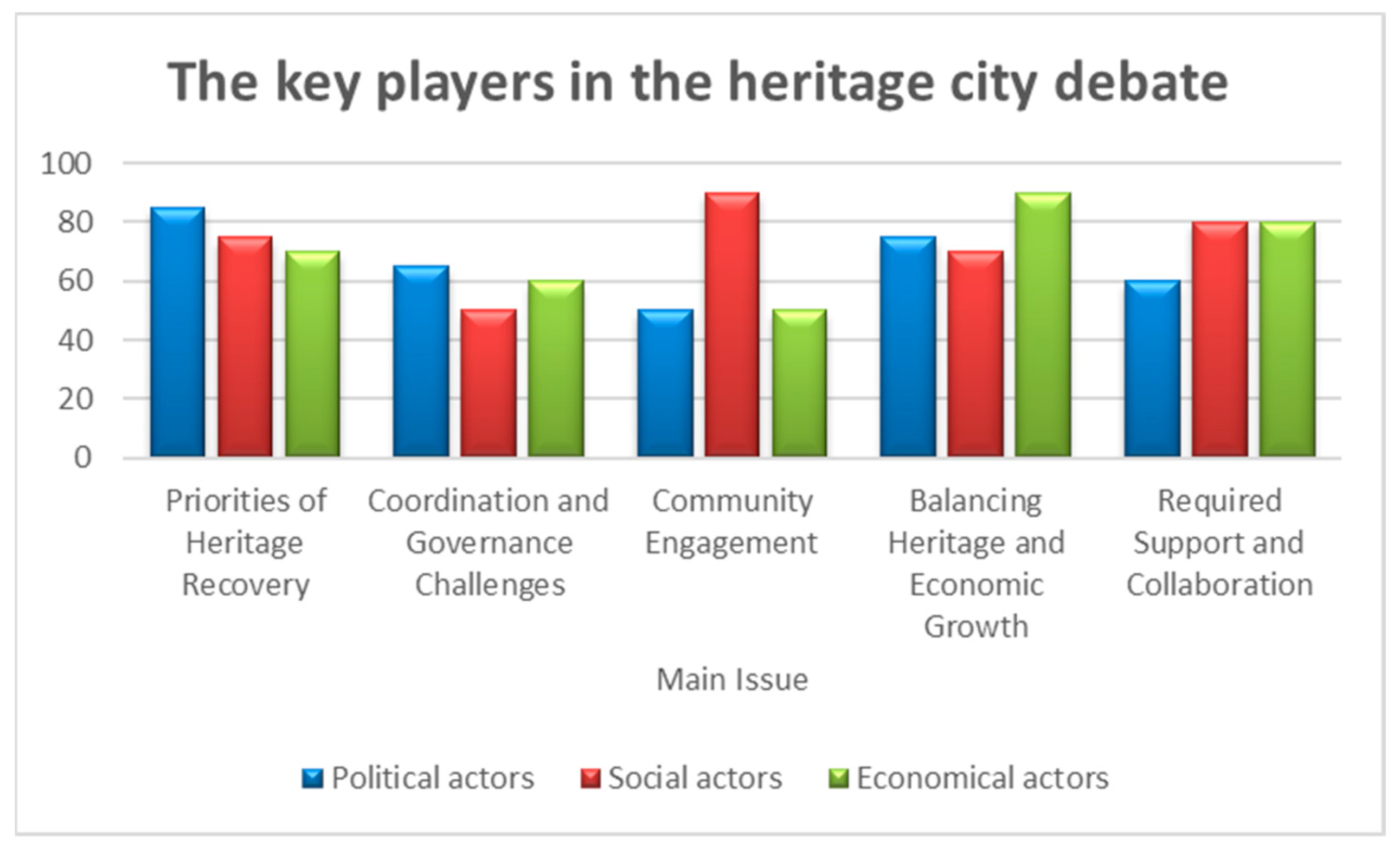

5.2. The Key Players in the Heritage City Debate

The key players in the heritage city debate in Syria are diverse and include political, social, and economic actors. Political actors play a crucial role in the reconstruction of historic sites in old Syrian cities. Social actors contribute to the preservation of cultural identity and heritage in old Syrian cities by raising awareness about their importance and advocating for their protection. Economic actors are also important as they play a significant role in tourism’s role in reviving Syria’s historic cities. These key players must work together to ensure that Syria’s cultural heritage is preserved for future generations. According to our field research and the aggregate of the interviews we conducted, we were able to identify guiding principles that must be deemed crucial when defining the roles of each player.

As historic Syrian cities face significant challenges in the post-war period, requiring international cooperation and assistance. The collaboration includes financial aid, technical expertise, capacity-building, and sharing best practices. Groups such as UNESCO, UNDP, and the World Bank hold the means to supply resources and circulate knowledge that can benefit local stakeholders in their journey toward sustainable development.

Fostering regional cooperation can address shared challenges like cross-border infrastructure, natural resource management, and humanitarian and development coordination. Initiatives like the European Union’s “Support to the Syrian Transition Process” and the “Friends of Syria” group promote dialog and cooperation among stakeholders, both inside and outside Syria.

5.2.1. Political Actors in the Reconstruction of Historic Sites in Old Syrian Cities

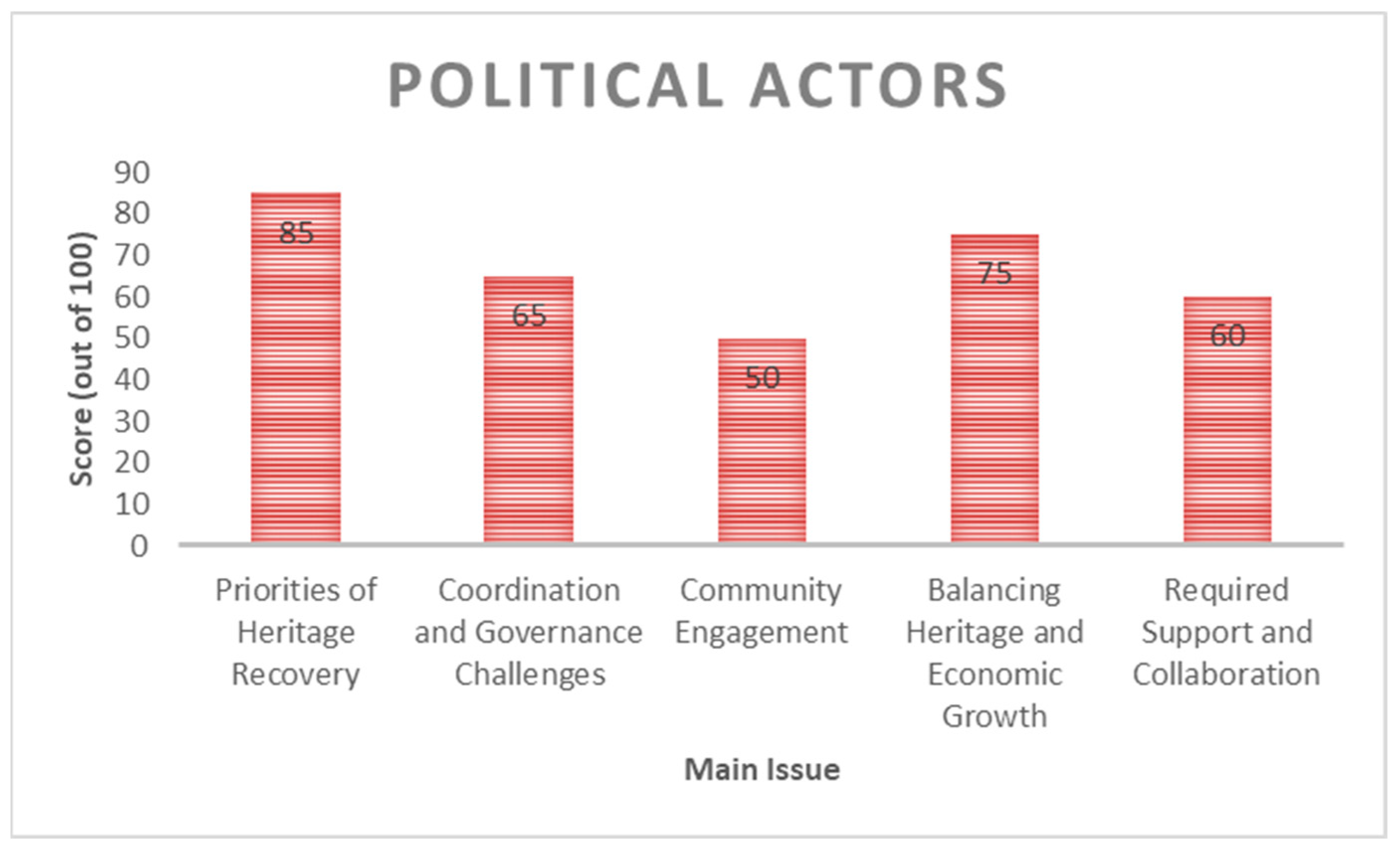

Political actors—including national ministries, municipal authorities, and heritage agencies—play a central role in the reconstruction of historic sites in old Syrian cities. They place high priority (85/100) on heritage recovery, viewing it as key to restoring national legitimacy and reinforcing cultural identity. While they acknowledge coordination and governance challenges (65/100), these are often downplayed publicly to maintain an image of state control. Community engagement ranks lower in their priorities (50/100), as decision-making processes are typically centralized and top-down. Importantly, political actors place significant emphasis (75/100) on balancing heritage conservation with economic growth, especially leveraging tourism for economic visibility and international funding. However, they also recognize the need for cross-sectoral collaboration (60/100), though institutional barriers often limit the effectiveness of such partnerships. Overall, political actors approach heritage recovery as a state-led process aimed at reinforcing national narratives and economic revival, often privileging high-profile projects over grassroots inclusion. See

Figure 7.

5.2.2. Social Actors’ Contributions to the Preservation of Cultural Identity and Heritage in Old Syrian Cities

Social agents—encompassing local communities, civil society organizations, cultural practitioners, and inhabitants—assume a crucial function in the safeguarding of the cultural identity and heritage associated with Syria’s historic urban centers. They place strong value (75/100) on heritage recovery as a foundation of collective memory and local identity, even though they often face marginalization in formal governance processes (50/100). Community engagement ranks highest (90/100), reflecting social actors’ prioritization of participation, local ownership, and cultural stewardship in heritage recovery efforts. While they welcome economic benefits (70/100), they remain cautious about commercialization that could compromise authenticity or displace residents. Social actors also recognize the need for cross-sectoral support (80/100), yet often struggle to secure sufficient resources or institutional backing. Overall, they champion bottom-up, participatory approaches that safeguard heritage while reinforcing social cohesion and cultural continuity. See

Figure 8.

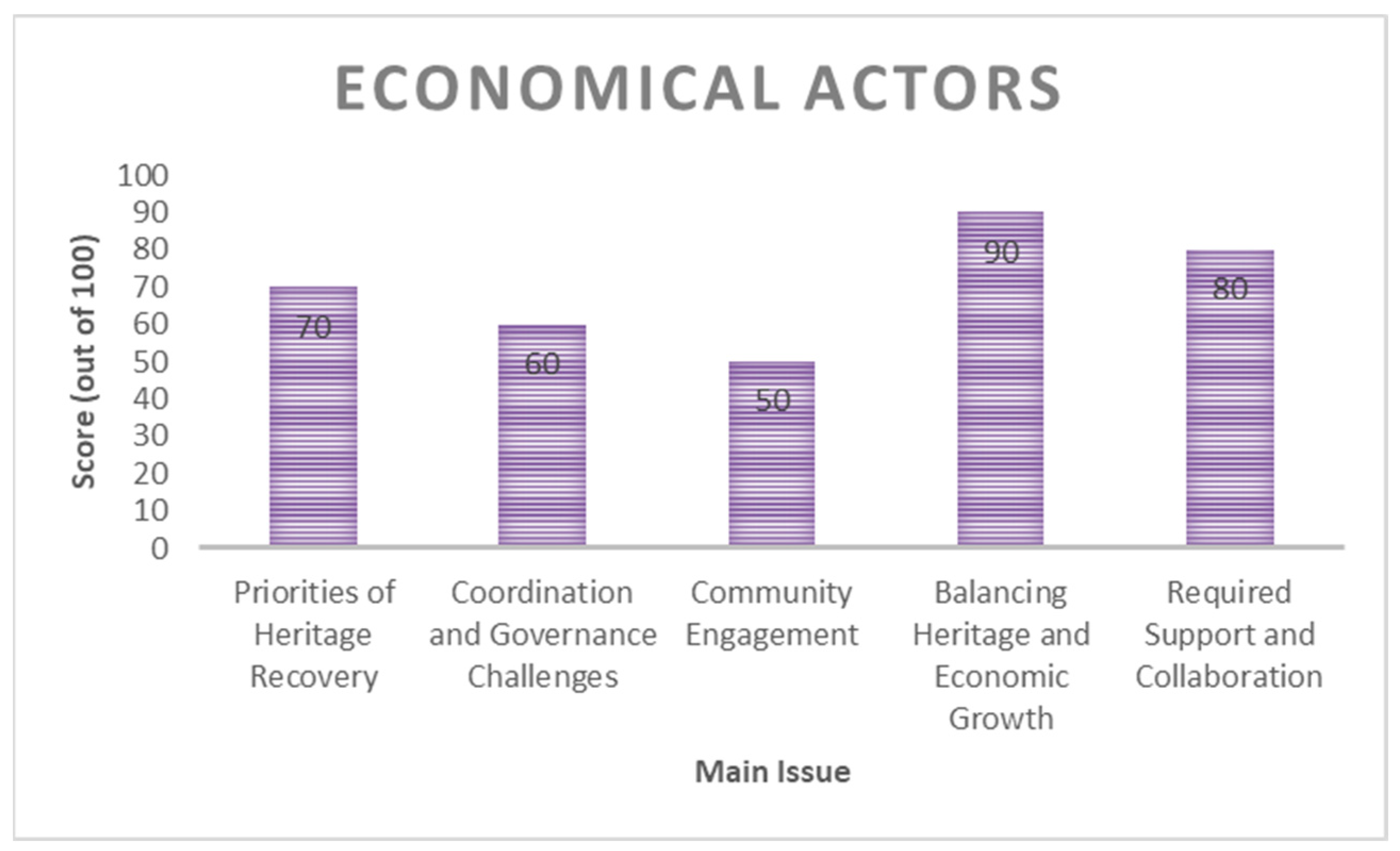

5.2.3. The Economic Actors Behind Tourism’s Role in Reviving Syria’s Historic Cities

Economic actors—including private investors, tourism developers, business owners, and market stakeholders—view heritage recovery primarily through its economic potential. They assign moderate importance (70/100) to heritage restoration, seeing it as a valuable asset for tourism, investment, and market revitalization. While they acknowledge governance and regulatory challenges (60/100), their focus lies on streamlining processes to enable efficient business operations. Community engagement ranks lower in their priorities (50/100), typically emphasized only when it aligns with market goals. The highest priority (90/100) is placed on balancing heritage preservation with economic growth, as economic actors seek profitability, expanded tourism markets, and investment returns. Additionally, they recognize the importance of collaboration and government facilitation (80/100) to ensure stable and successful projects. Overall, economic actors view heritage recovery as a strategic driver of economic revival, with tourism positioned at the center of Syria’s historic urban regeneration. See

Figure 9.

6. Discussion

There remains optimism for the future of these cities as they undergo gradual reconstruction. This optimism is grounded in the study’s theoretical synthesis, which reveals that the interplay between cultural heritage management, urban resilience, and sustainability theory provides a coherent framework for navigating post-conflict reconstruction. For instance, the data confirm the predictive relevance of resilience theory [

50] in explaining how communities adapt through decentralized governance and heritage-based identity reconstruction. Furthermore, the emphasis on authenticity and integrity—central to cultural heritage management theory [

52]—was repeatedly echoed in stakeholders’ calls for context-sensitive interventions. This indicates that theoretical insights were not only applied but were reflected in field data, validating the study’s conceptual architecture.

The primary challenge is balancing the preservation of cultural identity with the attraction of tourism investment. The devastation of these cities has profoundly affected many Syrians, whose residences and cultural legacies have been lost. To ensure the cultural integrity of these locales, restoration endeavors must be undertaken with a strong awareness of their historical and cultural narratives. This necessitates that any new developments harmonize with the existing architectural landscape and preserve the traditional urban structure.

The empirical findings offer significant insights into the post-conflict recovery landscape of historic Syrian cities. Notably, the analysis of actor motivations—across political, economic, and social groups—reveals both alignments and tensions that reflect deeper structural conditions. Thus, this section reflects on those divergences through the lens of the study’s theoretical framework and examines their broader relevance to post-conflict heritage governance and urban resilience.

6.1. Actor Divergence and Theoretical Interpretation

The data indicate broad agreement among political (85/100), economic (70/100), and social actors (75/100) on the importance of heritage recovery. However, their rationales diverge sharply: political actors emphasize national legitimacy, economic actors focus on investment potential, while social actors prioritize cultural continuity and participation.

These divergences can be interpreted through cultural heritage management (CHM) theory. CHM’s core concepts of authenticity and community ownership help explain social actors’ resistance to commodification, as seen in their lower acceptance of market-led restoration. Simultaneously, the economic actors’ approach aligns with sustainable tourism frameworks that stress revenue generation but risks undermining CHM’s emphasis on intangible heritage and intergenerational stewardship.

From a conflict studies perspective, the centralized behavior of political actors and their lower regard for community participation (scoring 50/100) may reflect a legacy of post-war institutional control and fragmented legitimacy. The prioritization of “high-visibility” projects over inclusive governance echoes findings from post-war Sarajevo and Beirut, where national narratives were often imposed over local identities to rebuild political capital.

In contrast, the urban resilience framework supports social actors’ demands for participatory models. Resilience, understood as a system’s capacity to adapt and reorganize, is weakened by top-down governance structures that marginalize community voices. These findings suggest that participatory models are not merely idealistic—they are structurally necessary to ensure long-term sustainability and prevent re-escalation of grievances.

However, significant divergences emerge when examining governance dynamics and community engagement. Political (65) and economic actors (60) acknowledge governance challenges, primarily focusing on institutional coordination and regulatory barriers, but social actors score this lower (50), reflecting their experience of exclusion and marginalization in formal governance structures. The starkest disagreement arises in the area of community engagement: social actors prioritize it highly, scoring 90/100, emphasizing participation, ownership, and empowerment, while political and economic actors assign it only 50/100, indicating a preference for centralized, efficiency-driven decision-making processes. These quantified gaps highlight structural tensions that risk undermining inclusive recovery strategies, underscoring the urgent need for mechanisms that amplify community voices, bridge institutional divides, and embed participatory governance models to ensure recovery efforts are not only effective but also socially equitable and culturally sustainable (

Figure 10).

6.2. Triangulation Across Methods

Triangulation across the qualitative and quantitative components confirms the hierarchy of challenges: war-related damage, funding shortages, and loss of skilled labor dominate both datasets. However, interviews further reveal how these challenges are institutionalized—e.g., lack of vocational training pipelines, fragmented donor coordination—and symbolic of material restoration.

This layered understanding refines previous assumptions in the literature. For example, Belal’s (2019) [

44] emphasis on external funding is validated, but the field data show that even when funding exists, governance bottlenecks limit implementation. Similarly, Zugaibi’s (2022) [

45] advocacy for tourism as peacebuilding is reinforced, but our findings warn of over-tourism and commodification risks unless CHM principles guide implementation.

It is crucial to prevent the displacement of current residents or businesses through new developments. Concurrently, enhancing the appeal of these cities to tourists is vital for generating necessary funds for reconstruction. This involves fostering a welcoming and secure atmosphere for visitors, complemented by amenities like restaurants and hotels. Consequently, it is imperative that new developments respect local customs and traditions to avoid deterring potential tourists.

6.3. Contribution to Theory and Practice

Local community involvement in city rebuilding fosters pride and heritage preservation. This study contributes to theory by proposing an integrated evaluative framework combining CHM, urban resilience, sustainability, and conflict studies—an approach rarely synthesized in the existing literature on post-conflict recovery. The study illustrates that divergences in actor priorities are not merely political but are structurally embedded in theoretical trade-offs between legitimacy and participation, between conservation and profitability.

Practically, the findings offer a context-sensitive model for heritage recovery in post-conflict settings. The proposed three-phase recovery strategy (short-, medium-, and long-term) balances immediate stabilization with community-led sustainability and aligns with UNESCO’s Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach. Moreover, the findings support calls for establishing local heritage councils and vocational pipelines that empower communities while meeting technical conservation standards.

Empowering locals through resources enables their participation in restoration initiatives. Despite civil war damage, there is potential for Syria’s historic cities if heritage protection and tourism attraction are balanced. Collaboration with international entities can facilitate financial and technical restoration support. Promoting sustainable tourism generates income while preserving cultural and historical value.

In old Syrian cities, it is clear that the people who live there are very important to keeping the culture and history alive. Recognizing the importance of historical sites and investing in their preservation can help ensure Syria’s heritage is honored by future generations. Tourism investment is essential for the revitalization of Syria’s ancient cities post-conflict. It facilitates infrastructure reconstruction, historical site restoration, business development, and cultural events, attracting both local and foreign interest in Syria’s rich culture and history. It is possible for old Syrian cities to become vibrant tourist destinations that contribute positively to both the local economy and international relations between Syria and other nations with proper planning and implementation of tourism investments (

Figure 11).

The findings, such as the anticipated challenges and the diversity of players in this massive urban endeavor, are discussed with S. Noaman. He demonstrates a number of strategic, economic, social, and environmental conclusions that can be drawn to cover gaps in Iraq’s long-term waste management. The research findings aim to support Iraq’s sustainable growth objectives post-disaster [

104].

We also encounter S. Barakat, who recognizes the significance of the situation and the importance of integrating cultural heritage into broader responses, incorporating other factors such as ongoing political and financial support, local capacity, participation of indigenous actors, recognition of complementarity between replacement and conservation approaches, prioritization of quality over speed of recovery, conservation codes and laws, and respect for belief and religion [

105]. We also meet M. S. Affaki, who talks about what to rebuild and how, goals and methods, and the importance of public involvement. He also suggests a context-specific reconstruction strategy aimed at contributing to social recovery by tackling the city’s socio-cultural and economic issues [

106].

Despite the fact that we have discussed the difficulties and roles of the various individuals involved in the restoration of ancient Syrian cities, this process, like all urban projects, is complex and involves overlaps for various individuals. This is evident when you consider the scope of our operations. Examining the scale in this instance requires participation from players of varying skill levels. The challenge at the historic site level is to preserve the physical integrity of historic sites while meeting the needs of tourists. Effective site management is essential for visitor enjoyment and protection. Certain municipalities have established strict regulations regarding visitor conduct, including restrictions on photography and visitor numbers.

7. Recommendations and Limitations

To achieve sustainable and inclusive recovery of historic Syrian cities, a phased action plan is recommended, structured across short-term (1–2 years), medium-term (3–5 years), and long-term (5+ years) timeframes. Thus, the study offers evidence-based, multi-scalar recommendations aligned with the study’s empirical findings and theoretical framework. Recommendations are organized into short-, medium-, and long-term actions, with explicit alignment to stakeholder roles (e.g., policymakers, NGOs, heritage planners). A reflective limitations discussion follows, clarifying methodological boundaries and guiding future research.

7.1. Short Term (1–2 Years): Immediate Stabilization and Data Collection

Target stakeholders: Municipal governments, emergency NGOs, ICOMOS technical partners.

Linked findings: Survey results indicate 85.8% of respondents view war-related damage as the most urgent issue.

- ○

Prioritize emergency stabilization of severely damaged heritage sites, especially those rated high in symbolic or community value (e.g., Aleppo, Bosra).

- ○

Initiate rapid heritage assessments using drones, GIS mapping, and photogrammetry in coordination with displaced residents (supports CHM integrity).

- ○

Launch public awareness campaigns to rebuild cultural engagement and prevent looting, addressing the 80.8% concern over low public understanding.

7.2. Medium Term (3–5 Years): Capacity-Building and Participatory Planning

Target stakeholders: Local universities, vocational centers, Ministry of Culture, UNESCO.

Linked findings: A total of 83.2% identified the lack of skilled labor; interviewees stressed gaps in conservation training.

- ○

Establish vocational programs focused on traditional building techniques (mudbrick, stone carving) to revive regional craft practices and CHM authenticity.

- ○

Form community heritage councils as participatory governance mechanisms to mediate between local knowledge and national recovery planning.

- ○

Implement pilot cultural tourism routes, drawing from Dayoub’s (2020) [