From Diversity to Engagement: The Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction in the Link Between Diversity Climate and Organizational Withdrawal

Abstract

1. Introduction

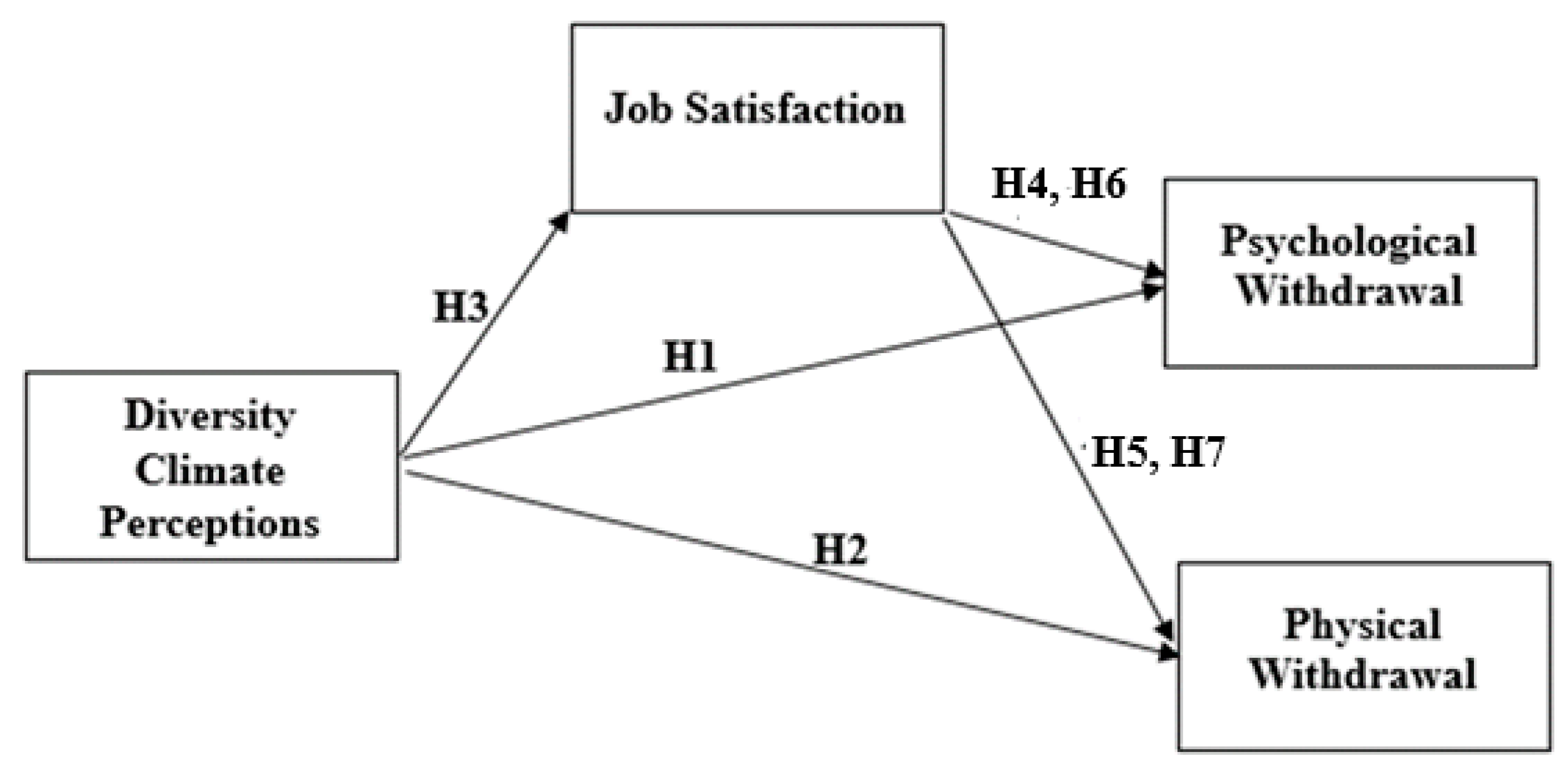

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Diversity Climate Perceptions and Organizational Withdrawal

2.2. Diversity Climate Perceptions and Job Satisfaction

2.3. Job Satisfaction and Organizational Withdrawal

2.4. Job Satisfaction as a Mediator

2.5. Theoretical Support: Social Exchange Theory

3. Methodology

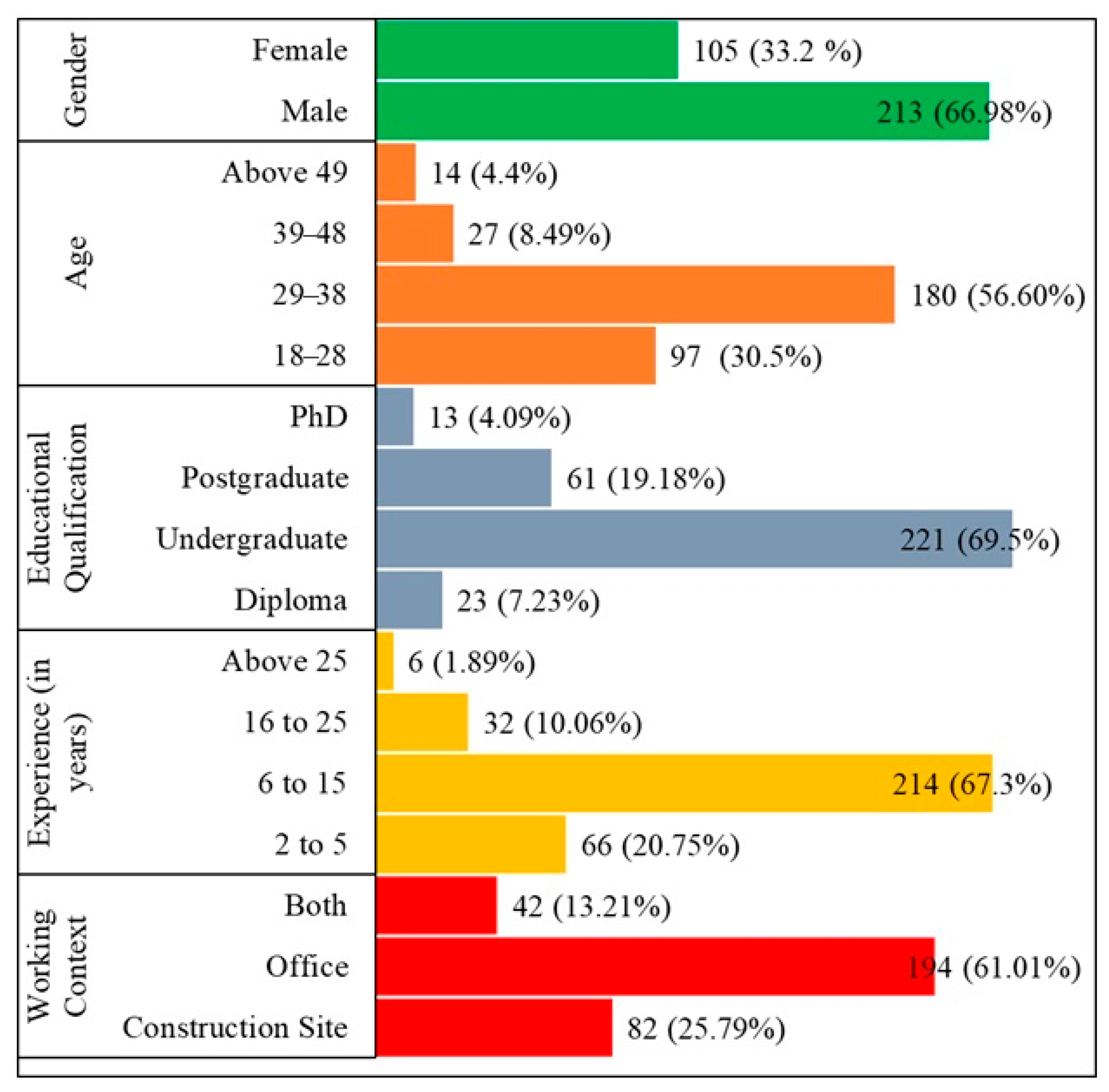

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measures

4. Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Matrix

4.2. Measurement Model

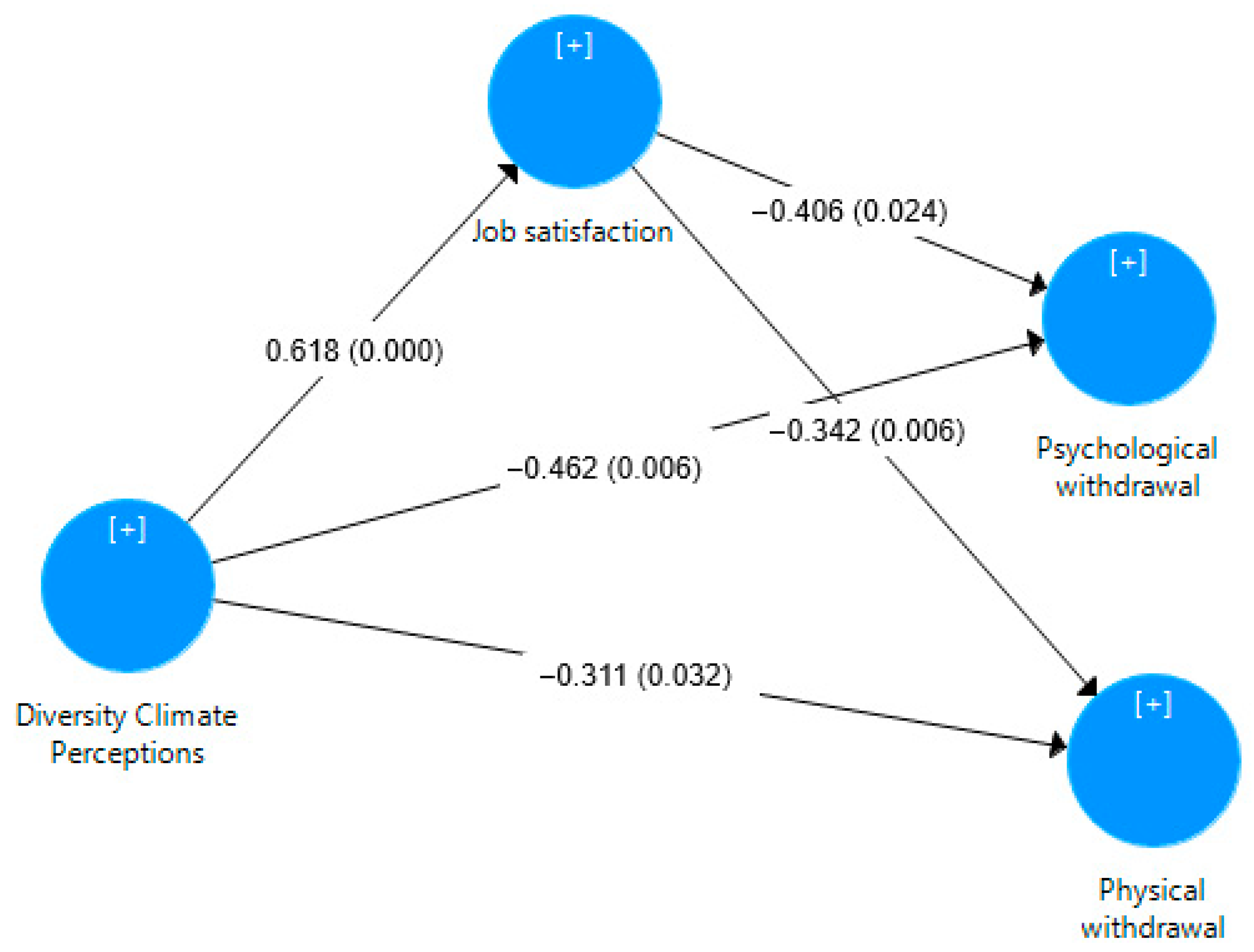

4.3. Structural Model

5. Discussion

6. Implications

7. Limitations and Future Directions

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AVE | Average variance extracted |

| CA | Cronbach’s alpha |

| CR | Composite reliability |

| CMB | Common method bias |

| DC | Diversity climate |

| f2 | Effect size |

| JS | Job satisfaction |

| NFI | Normed fit index |

| OW | Organizational withdrawal |

| PSW | Psychological withdrawal |

| PW | Physical withdrawal |

| PLS-SEM | Partial least squares structural equation modeling |

| Q2 | Predictive relevance |

| R2 | Coefficient of determination |

| SET | Social exchange theory |

| SEM | Structural equation modeling |

| SPSS | Statistical package for social sciences |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| VIF | Variance inflation factor |

References

- Soundarya Priya, M.G.; Anandh, K.S. Unequal Ground: Gender Disparities at Work Life in the Construction Industry. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creating Opportunities for Women in Construction in India: A Call for Action. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/resource/news/creating-opportunities-women-construction-india-call-action (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- India Construction Industry Databook Series—Market Size & Forecast by Value and Volume, Q1 2025 Update. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/5918199/india-construction-industry-databook-series (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Ganesh, R.; Tyagi, R. Managing the Shortage of Skilled Construction Workers in India by Effective Talent Management in New Normal-Technology Perspective. Int. J. Manag. 2021, 12, 224–247. [Google Scholar]

- Ayodele, O.A.; Chang-Richards, A.; González, V. Factors Affecting Workforce Turnover in the Construction Sector: A Systematic Review. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 03119010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanasekar, Y.; Anandh, K.S. Deciphering the Role of Age and Gender in Perceiving Organizational Politics in Construction. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2025, 15, 354–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion in Construction. Available online: https://www.ciob.org/industry/EDI (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Cox, T.H.; Blake, S. Managing Cultural Diversity: Implications for Organizational Competitiveness. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1991, 5, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.A.; Klein, K.J. What’s the Difference? Diversity Constructs as Separation, Variety, or Disparity in Organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 1199–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanasekar, Y.; Anandh, K.S.; Szóstak, M. Development of the Diversity Concept for the Construction Sector: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunindijo, R.Y.; Kamardeen, I. Work Stress Is a Threat to Gender Diversity in the Construction Industry. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2017, 143, 04017073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S. Building a More Inclusive Future: Promoting Women’s Inclusion in the Construction Industry. Available online: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/voices/building-a-more-inclusive-future-promoting-womens-inclusion-in-the-construction-industry/ (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- 4 Things Standing in the Way of Diversity in Construction. Available online: https://safesitehq.com/diversity-in-construction/ (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Norberg, C.; Johansson, M. “Women and ‘Ideal’ Women”: The Representation of Women in the Construction Industry. Gend. Issues 2021, 38, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confederation of Indian Industry (CII); International Labour Organization (ILO). Beyond Barriers and Biases: Engendering the Indian Construction Industry; Confederation of Indian Industry (CII): New Delhi, India, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Johari, S.; Jha, K.N. Exploring the Relationship between Construction Workers’ Communication Skills and Their Productivity. J. Manag. Eng. 2021, 37, 04021009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Farooquie, A.J. A Critical Review on Workforce Diversity Management. Int. J. Enhanc. Res. Manag. Comput. Appl. 2021, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Haizelden, J.; Marasini, R.; Daniel, E. An Analysis of Diversity Management in the Construction Industry: A Case Study of a Main Contractor. In Proceedings of the 35th Annual ARCOM Conference, Leeds, UK, 2–4 September 2019; pp. 465–474. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, J.A.; DeNisi, A.S. Cross-level Effects of Demography and Diversity Climate on Organizational Attachment and Firm Effectiveness. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauring, J.; Selmer, J. Multicultural Organizations: Does a Positive Diversity Climate Promote Performance? Eur. Manag. Rev. 2011, 8, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, S.A.; Kunze, F.; Bruch, H. Spotlight on Age-Diversity Climate: The Impact of Age-Inclusive HR Practices on Firm-Level Outcomes. Pers. Psychol. 2014, 67, 667–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallaghan, S. Work-Place Diversity Climate: Its Association with Racial Microaggressions and Employee Work-Place Well-Being. J. Psychol. Afr. 2022, 32, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, N.; Son Hing, L.S.; González-Morales, M.G. Development and Validation of the Marginalized-Group-Focused Diversity Climate Scale: Group Differences and Outcomes. J. Bus. Psychol. 2023, 38, 689–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badgett, M.V.L.; Waaldijk, K.; Rodgers, Y.v.d.M. The Relationship between LGBT Inclusion and Economic Development: Macro-Level Evidence. World Dev. 2019, 120, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laczo, R.M.; Hanisch, K.A. An Examination of Behavioral Families of Organizational Withdrawal in Volunteer Workers and Paid Employees. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1999, 9, 453–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. The Nature and Causes of Job Satisfaction. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Rand McNally: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976; pp. 1297–1349. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T.A.; Thoresen, C.J.; Bono, J.E.; Patton, G.K. The Job Satisfaction–Job Performance Relationship: A Qualitative and Quantitative Review. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 376–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, D.M.; Wiley, J.W.; Maertz, C.P. The Role of Calculative Attachment in the Relationship between Diversity Climate and Retention. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 50, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, P.F.; Avery, D.R.; Morris, M.A. Mean Racial-Ethnic Differences in Employee Sales Performance: The Moderating Role of Diversity Climate. Pers. Psychol. 2008, 61, 349–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, L.M.; Gelfand, M.J. The Who and When of Internal Gender Discrimination Claims: An Interactional Model. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2008, 107, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupali; Mishra, P.; Shukla, B. Diversity Climate and Turnover Intention: A Moderated-Mediation Model of Affective Commitment and Ethical Climate. J. Stat. Manag. Syst. 2023, 26, 659–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settles, I.H.; Brassel, S.T.; Soranno, P.A.; Cheruvelil, K.S.; Montgomery, G.M.; Elliott, K.C. Team Climate Mediates the Effect of Diversity on Environmental Science Team Satisfaction and Data Sharing. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spendolini, M.J. Employee Withdrawal Behavior: Expanding the Concept (Turnover, Absenteeism); University of California: Irvine, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Rosse, J.G.; Hulin, C.L. Adaptation to Work: An Analysis of Employee Health, Withdrawal and Change. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1985, 36, 324–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanisch, K.A.; Hulin, C.L. Job Attitudes and Organizational Withdrawal: An Examination of Retirement and Other Voluntary Withdrawal Behaviors. J. Vocat. Behav. 1990, 37, 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetto, Y.; Teo, S.T.T.; Shacklock, K.; Farr-Wharton, R. Emotional Intelligence, Job Satisfaction, Well-Being and Engagement: Explaining Organisational Commitment and Turnover Intentions in Policing. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2012, 22, 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffeth, R.W.; Hom, P.W.; Gaertner, S. A Meta-Analysis of Antecedents and Correlates of Employee Turnover: Update, Moderator Tests, and Research Implications for the Next Millennium. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 463–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, S.; Hashmi, H.B.A.; Abbass, K.; Ahmad, B.; Khan Niazi, A.A.; Achim, M.V. Unlocking the Effect of Supervisor Incivility on Work Withdrawal Behavior: Conservation of Resource Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 887352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Li, X. The Hidden Costs of Emotional Labor on Withdrawal Behavior: The Mediating Role of Emotional Exhaustion, and the Moderating Effect of Mindfulness. BMC Psychol. 2023, 11, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, I.; Mishra, G.; Farooqi, R. Diversity Climate Perceptions and Turnover Intentions: Evidence From the Indian IT Industry. Int. J. Hum. Cap. Inf. Technol. Prof. 2022, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, Y. Diversity Climate on Turnover Intentions: A Sequential Mediating Effect of Personal Diversity Value and Affective Commitment. Pers. Rev. 2021, 50, 1397–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, P.M.; Self, T.T. Psychological Diversity Climate, Organizational Embeddedness, and Turnover Intentions: A Conservation of Resources Perspective. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2020, 61, 416–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seriwatana, P. Diversity Climate as a Key to Employee Retention: The Moderating Role of Perceived Cultural Difference. SSRN Electron. J. 2022, 4, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ely, R.J.; Thomas, D.A. Cultural Diversity at Work: The Effects of Diversity Perspectives on Work Group Processes and Outcomes. Adm. Sci. Q. 2001, 46, 229–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purani, K.; Sahadev, S. The Moderating Role of Industrial Experience in the Job Satisfaction, Intention to Leave Relationship: An Empirical Study among Salesmen in India. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2008, 23, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, L.M.; Randel, A.E.; Chung, B.G.; Dean, M.A.; Holcombe Ehrhart, K.; Singh, G. Inclusion and Diversity in Work Groups: A Review and Model for Future Research. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1262–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishii, L.H. The Benefits of Climate for Inclusion for Gender-Diverse Groups. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1754–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maj, J. Influence of Inclusive Work Environment and Perceived Diversity on Job Satisfaction: Evidence from Poland. Cent. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2023, 12, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabharwal, M. Is Diversity Management Sufficient? Organizational Inclusion to Further Performance. Public Pers. Manag. 2014, 43, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farashah, A.; Blomquist, T.; Bešić, A. The Impact of Workplace Diversity Climate on the Career Satisfaction of Skilled Migrant Employees. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2024, 22, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrobot-Mason, D.; Aramovich, N.P. The Psychological Benefits of Creating an Affirming Climate for Workplace Diversity. Group Organ. Manag. 2013, 38, 659–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Ke, Y.; Li, N.; Su, Z. Exploring the Impact of Job Satisfaction on Turnover Intention among Professionals in the Construction Industry. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands-Resources Theory: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; LePine, J.A.; LePine, M.A. Differential Challenge Stressor-Hindrance Stressor Relationships with Job Attitudes, Turnover Intentions, Turnover, and Withdrawal Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 438–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, C.D. Mood and Emotions While Working: Missing Pieces of Job Satisfaction? J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Gerhart, B.; Weller, I.; Trevor, C.O. Understanding Voluntary Turnover: Path-Specific Job Satisfaction Effects and The Importance of Unsolicited Job Offers. Acad. Manag. J. 2008, 51, 651–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, A.L.; Eberly, M.B.; Lee, T.W.; Mitchell, T.R. Surveying the Forest: A Meta-analysis, Moderator Investigation, and Future-oriented Discussion of the Antecedents of Voluntary Employee Turnover. Pers. Psychol. 2018, 71, 23–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S. Diversity in the US Federal Government: Diversity Management and Employee Turnover in Federal Agencies. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2009, 19, 603–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, A.; Ma, E.; Lloyd, K.; Reid, S. Organizational Ethnic Diversity’s Influence on Hotel Employees’ Satisfaction, Commitment, and Turnover Intention: Gender’s Moderating Role. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 76–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, R.M. Social Exchange Theory. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1976, 2, 335–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farndale, E.; Van Ruiten, J.; Kelliher, C.; Hope-Hailey, V. The Influence of Perceived Employee Voice on Organizational Commitment: An Exchange Perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 50, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Doghan, M.A.; Bhatti, M.A.; Juhari, A.S. Do Psychological Diversity Climate, HRM Practices, and Personality Traits (Big Five) Influence Multicultural Workforce Job Satisfaction and Performance? Current Scenario, Literature Gap, and Future Research Directions. Sage Open 2019, 9, 2158244019851578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, S.J.; Shore, L.M.; Liden, R.C. Perceived Organizational Support and Leader-Member Exchange: A Social Exchange Perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 82–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, R.; Timsina, T.P. An Educational Study Focused on the Application of Mixed Method Approach as a Research Method. OCEM J. Manag. Technol. Soc. Sci. 2024, 3, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzi, A.R.; K.S., A.; Alias, A.R.; Algahtany, M.; Rahman, R.A. Modeling the Factors Affecting Workplace Well-Being at Construction Sites: A Cross-Regional Multigroup Analysis. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2024, 23, 1087–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, A.; Singla, H.K. Exploration of Exhaustion in Early-Career Construction Professionals in India. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024, 31, 3853–3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtom, B.; Baruch, Y.; Aguinis, H.; A Ballinger, G. Survey Response Rates: Trends and a Validity Assessment Framework. Hum. Relations 2022, 75, 1560–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-1-5443-9640-8. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-Reports in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor Barak, M.E.; Cherin, D.A.; Berkman, S. Organizational and Personal Dimensions in Diversity Climate. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1998, 34, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdemli, Ö. Teachers’ Withdrawal Behaviors and Their Relationship with Work Ethic. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2015, 15, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brayfield, A.H.; Rothe, H.F. An Index of Job Satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 1951, 35, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Straub, D.W.; Ketchen, D.J.; Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Calantone, R.J. Common Beliefs and Reality About PLS. Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 17, 182–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988; ISBN 0-8058-0283-5. [Google Scholar]

- Suhan; Samartha, V.; Kodikal, R. Measuring the Effect Size of Coefficient of Determination and Predictive Relevance of Exogenous Latent Variables on Endogenous Latent Variables through PLS-SEM. Int. J. Pure Appl. Math. 2018, 119, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Shmueli, G.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Cheah, J.H.; Ting, H.; Vaithilingam, S.; Ringle, C.M. Predictive Model Assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for Using PLSpredict. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2322–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, A.-K.; Beal, D.J.; Zyphur, M.J.; Zhang, H.; Bobko, P. Diversity Climate, Trust, and Turnover Intentions: A Multilevel Dynamic System. J. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 107, 628–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, L.M.; Cleveland, J.N.; Sanchez, D. Inclusive Workplaces: A Review and Model. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2018, 28, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuoribo, E.; Amoah, P.; Kissi, E.; Edwards, D.J.; Gyampo, J.A.; Thwala, W.D. Analysing the Effect of Multicultural Workforce/Teams on Construction Productivity. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2024, 22, 969–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, V.; Michielsens, E. Exclusion and Inclusion in the Australian AEC Industry and Its Significance for Women and Their Organizations. J. Manag. Eng. 2021, 37, 04021051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingard, H.; Francis, V. The Work-life Experiences of Office and Site-based Employees in the Australian Construction Industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2004, 22, 991–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein, A.L.; Eberly, M.B.; Lee, T.; Mitchell, T.R. Looking Beyond the Trees: A Meta-Analysis and Integration of Voluntary Turnover Research. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2015, 2015, 12779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehn, K.A.; Northcraft, G.B.; Neale, M.A. Why Differences Make a Difference: A Field Study of Diversity, Conflict and Performance in Workgroups. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 741–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdman, A.O.; McMillan-Capehart, A. Establishing a Diversity Program Is Not Enough: Exploring the Determinants of Diversity Climate. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A.; Dyaram, L. Perceived Diversity and Employee Well-Being: Mediating Role of Inclusion. Pers. Rev. 2020, 49, 1121–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Item Code | Item Description |

|---|---|---|

| DC—Fairness | A1 | Promotion decisions are based solely on job performance and qualifications, without regard for factors like race, gender, or age. |

| A2 | Pay and benefits are distributed equitably across all employee groups, regardless of background. | |

| A3 | My organization ensures that all employees have equal access to professional development opportunities. | |

| A4 | I often feel that my contributions are overlooked compared to those of my colleagues from different backgrounds. (Reverse-coded) | |

| A5 | Layoff decisions are made without bias, considering only job performance and organizational needs. | |

| DC—Inclusion | B1 | My organization actively seeks to create a sense of belonging for all employees, regardless of their background. |

| B2 | Employees from diverse backgrounds are involved in key decision-making processes. | |

| B3 | My organization promotes the inclusion of employees from all backgrounds in social and work-related activities. | |

| B4 | There are clear initiatives in place to support the inclusion of employees from underrepresented groups (e.g., women, minorities). | |

| B5 | I believe that my organization values the unique contributions of all employees, regardless of their background. | |

| DC—Interpersonal Valuing | C1 | My colleagues and I openly share ideas and perspectives, regardless of our differences. |

| C2 | Employees in my organization respect and appreciate the cultural differences of their colleagues. | |

| C3 | I feel comfortable interacting with colleagues from different cultural or social backgrounds. | |

| C4 | I occasionally feel that my ideas are dismissed because of my background. (Reverse-coded) | |

| C5 | Managers actively seek input from employees of different demographic groups in problem-solving and decision-making. | |

| DC—Anti-discrimination | D1 | The organization has clear procedures in place for reporting and addressing incidents of discrimination. |

| D2 | Managers are committed to eliminating any forms of bias and discrimination within the workplace. | |

| D3 | The organization responds quickly and effectively to any incidents of discrimination. | |

| D4 | I sometimes worry that reporting discrimination may lead to negative consequences for me. (Reverse-coded) | |

| D5 | I feel safe from discrimination in my workplace. | |

| D6 | There is a culture of intolerance towards discrimination, which is reinforced by the organization’s leadership. | |

| PSW | PSW1 | I often find myself occupied with irrelevant things at work. |

| PSW2 | I frequently surf the web or use the internet for non-work purposes. | |

| PSW3 | I put effort into looking busy, even when I’m not actually working. | |

| PSW4 | I often chat with colleagues about non-work-related topics. | |

| PSW5 | I constantly check the time, waiting for the workday to end. | |

| PSW6 | I put in less effort than what is normally expected of me at work. | |

| PSW7 | I spend time making long personal calls during work hours. | |

| PSW8 | I often talk about wanting to leave the company. | |

| PSW9 | I frequently ask others to do tasks that are my responsibility. | |

| PW | PW1 | I take leave or sick days even when I am not actually sick. |

| PW2 | I arrive late for work without a valid reason. | |

| PW3 | I leave work early without obtaining permission. | |

| PW4 | I avoid participating in important meetings or company events (e.g., performance reviews, group meetings). | |

| PW5 | I do not return to the office or site after completing off-site work early. | |

| PW6 | I take longer breaks than I am allowed. | |

| PW7 | I often disappear from the worksite or office without informing anyone. | |

| JS | JS1 | I am satisfied with the work I do. |

| JS2 | I am satisfied with my supervisor. | |

| JS3 | I am satisfied with the relations I have with my co-workers. | |

| JS4 | I am satisfied with the pay I receive for my job. | |

| JS5 | I am satisfied with the opportunities that exist in this organization for advancement (promotion). | |

| JS6 | All things considered; I am satisfied with my current job situation. |

| Variable | Mean | SD | DC | PSW | PW | JS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC | 3.634 | 1.135 | 1 | |||

| PSW | 2.886 | 0.985 | −0.783 ** | 1 | ||

| PW | 2.798 | 1.04 | −0.665 ** | 0.811 ** | 1 | |

| JS | 3.746 | 1.252 | 0.736 ** | −0.807 ** | −0.762 ** | 1 |

| Construct | Item | Outer Loadings | VIF | CA | rho_a | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC | A1 | 0.861 | 2.750 | 0.896 | 0.927 | 0.981 | 0.714 |

| A2 | 0.921 | 3.228 | |||||

| A3 | 0.790 | 1.942 | |||||

| A4 | 0.844 | 2.680 | |||||

| A5 | 0.815 | 2.515 | |||||

| B1 | 0.911 | 3.126 | |||||

| B2 | 0.805 | 2.504 | |||||

| B3 | 0.837 | 2.243 | |||||

| B4 | 0.776 | 1.640 | |||||

| B5 | 0.830 | 2.311 | |||||

| C1 | 0.812 | 1.951 | |||||

| C2 | 0.845 | 2.132 | |||||

| C3 | 0.806 | 2.051 | |||||

| C4 | 0.811 | 1.982 | |||||

| C5 | 0.865 | 2.253 | |||||

| D1 | 0.877 | 2.864 | |||||

| D2 | 0.922 | 3.352 | |||||

| D3 | 0.788 | 1.892 | |||||

| D4 | 0.884 | 2.731 | |||||

| D5 | 0.867 | 2.615 | |||||

| D6 | 0.854 | 2.401 | |||||

| PSW | PSW1 | 0.816 | 2.020 | 0.903 | 0.928 | 0.957 | 0.717 |

| PSW2 | 0.915 | 2.971 | |||||

| PSW3 | 0.873 | 2.350 | |||||

| PSW4 | 0.841 | 2.226 | |||||

| PSW5 | 0.827 | 2.332 | |||||

| PSW6 | 0.811 | 2.172 | |||||

| PSW7 | 0.913 | 3.237 | |||||

| PSW8 | 0.892 | 2.560 | |||||

| PSW9 | 0.911 | 3.138 | |||||

| PW | PW1 | 0.873 | 2.577 | 0.896 | 0.915 | 0.944 | 0.707 |

| PW2 | 0.825 | 1.922 | |||||

| PW3 | 0.818 | 2.148 | |||||

| PW4 | 0.922 | 3.156 | |||||

| PW5 | 0.748 | 1.867 | |||||

| PW6 | 0.865 | 2.366 | |||||

| PW7 | 0.823 | 2.030 | |||||

| JS | JS1 | 0.801 | 2.122 | 0.878 | 0.890 | 0.936 | 0.708 |

| JS2 | 0.787 | 2.133 | |||||

| JS3 | 0.834 | 2.443 | |||||

| JS4 | 0.851 | 2.677 | |||||

| JS5 | 0.891 | 2.984 | |||||

| JS6 | 0.879 | 2.352 |

| Construct | DC | PSW | PW | JS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC | 0.845 | |||

| PSW | −0.783 | 0.846 | ||

| PW | −0.665 | 0.811 | 0.840 | |

| JS | 0.736 | −0.807 | −0.762 | 0.841 |

| Hypothesis | Paths | β | SD | T-Statistics | R2 | f2 | Q2 | Decision | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | DC → PSW | −0.462 | 0.17 | 2.718 ** | 0.323 | 0.465 | 0.271 | Supported | −0.795, −0.129 |

| H2 | DC → PW | −0.311 | 0.14 | 2.172 * | 0.287 | 0.194 | 0.145 | Supported | −0.592, −0.030 |

| H3 | DC → JS | 0.618 | 0.112 | 5.518 *** | 0.542 | 0.734 | 0.412 | Supported | 0.398, 0.838 |

| H4 | JS → PSW | −0.406 | 0.174 | 2.330 * | - | - | - | Supported | −0.748, −0.064 |

| H5 | JS → PW | −0.342 | 0.126 | 2.707 ** | - | - | - | Supported | −0.590, −0.094 |

| H6 | DC → JS → PSW | −0.094 | 0.035 | 2.653 ** | - | - | - | Supported | −0.163, −0.024 |

| H7 | DC → JS → PW | −0.068 | 0.026 | 2.617 ** | - | - | - | Supported | −0.119, −0.017 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dhanasekar, Y.; Anandh, K.S. From Diversity to Engagement: The Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction in the Link Between Diversity Climate and Organizational Withdrawal. Buildings 2025, 15, 2368. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132368

Dhanasekar Y, Anandh KS. From Diversity to Engagement: The Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction in the Link Between Diversity Climate and Organizational Withdrawal. Buildings. 2025; 15(13):2368. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132368

Chicago/Turabian StyleDhanasekar, Yuvaraj, and Kaliyaperumal Sugirthamani Anandh. 2025. "From Diversity to Engagement: The Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction in the Link Between Diversity Climate and Organizational Withdrawal" Buildings 15, no. 13: 2368. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132368

APA StyleDhanasekar, Y., & Anandh, K. S. (2025). From Diversity to Engagement: The Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction in the Link Between Diversity Climate and Organizational Withdrawal. Buildings, 15(13), 2368. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15132368